Abstract

The events that contribute to the progression to AIDS during the acute phase of a primate lentiviral infection are still poorly understood. In this study, we used pathogenic and nonpathogenic simian models of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of rhesus macaques (RMs) and African green monkeys (AGMs), respectively, to investigate the relationship between apoptosis in lymph nodes and the extent of viral replication, immune activation, and disease outcome. Here, we show that, in SIVmac251-infected RMs, a marked increased in lymphocyte apoptosis is evident during primary infection at the level of lymph nodes. Interestingly, the levels of apoptosis correlated with the extent of viral replication and the rate of disease progression to AIDS, with higher apoptosis in RMs of Indian genetic background than in those of Chinese origin. In stark contrast, no changes in the levels of lymphocyte apoptosis were observed during primary infection in the nonpathogenic model of SIVagm-sab infection of AGMs, despite similarly high rates of viral replication. A further and early divergence between SIV-infected RMs and AGMs was observed in terms of the dynamics of T- and B-cell proliferation in lymph nodes, with RMs showing significantly higher levels of cycling cells (Ki67+) in the T-cell zones in association with relatively low levels of Ki67+ in the B-cell zones, whereas AGMs displayed a low frequency of Ki67+ in the T-cell area but a high proportion of Ki67+ cells in the B-cell area. As such, this study suggests that species-specific host factors determine an early immune response to SIV that predominantly involves either cellular or humoral immunity in RMs and AGMs, respectively. Taken together, these data are consistent with the hypotheses that (i) high levels of T-cell activation and lymphocyte apoptosis are key pathogenic factors during pathogenic SIV infection of RMs and (ii) low T-cell activation and apoptosis are determinants of the AIDS resistance of SIVagm-infected AGMs, despite high levels of SIVagm replication.

While rhesus macaques (RMs) infected with a macaque strain of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) usually progress to AIDS in 1 to 2 years, African nonhuman primates (NHPs) infected with their species-specific SIV rarely develop disease. Previous studies of natural, nonpathogenic primate models of SIV infection, such as SIVagm infection of African green monkeys (AGMs), SIVsmm or SIVmac infection of sooty mangabeys (SMs), and SIVmnd type 1 (SIVmnd-1) and SIVmnd-2 infection of mandrills have consistently shown that, in these animals, the plasma viral loads are similar to those observed in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected humans and SIVmac-infected RMs (2, 6, 10, 16, 18, 19, 29, 32, 35, 39). However, only HIV infections in humans and SIVmac infections in RMs lead to progressive CD4-positive (CD4+) T-cell depletion and AIDS. Understanding the basis of pathogenic and nonpathogenic host-virus relationships is likely to provide important clues regarding AIDS pathogenesis.

The primary acute phase of HIV and SIV infections is characterized by an early burst of viral replication, an exponential increase in the viral load, the dissemination and seeding of the virus in all peripheral lymphoid organs, a severe depletion of memory CD4+ T cells from the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), and the induction of the host immune response against the virus (21, 24, 27, 41, 45). Several observations indicate that the early induction of an effective immune response against the virus plays a role in determining the levels of viral load at the end of the primary phase (i.e., the set point). The level of viral load in the peripheral blood is a strong predictor of disease progression in pathogenic lentivirus infection (21, 31, 36, 37, 45). Moreover, an increased level of immune activation in pathogenic lentivirus infection is correlated with disease progression toward AIDS (4, 27, 39). Importantly, the early stages of nonpathogenic SIV infection of AGMs and SMs are also characterized by a peak of virus replication in peripheral blood accompanied by rapid dissemination of the virus and depletion of CD4+ T cells from the MALT. However, in these nonprogressing hosts, it has been shown that the level of immune activation remains relatively low compared to that in RMs (2, 8, 19, 32, 40).

An increased lymphocyte susceptibility to apoptosis, which is in turn thought to be related to heightened levels of immune activation, has been proposed as one of the main mechanisms responsible for the CD4+ T-cell depletion in vivo during pathogenic HIV and SIV infections (1, 12, 17). Studies performed in pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate models of SIV infection during the asymptomatic phase have further suggested the presence of a direct correlation between progression to AIDS and the level of CD4+ T-cell apoptosis ex vivo (8, 40, 44). We recently reported that primary SIVmac251 infection of RMs of Chinese origin, which are known to progress to AIDS more slowly than Indian monkeys (22, 34), is also associated with increased numbers of apoptotic cells in the lymph nodes (LNs) (25, 43). The reasons why the course of SIVmac infection is milder in Chinese RMs than in Indian RMs are still poorly understood. Since SIVmac strains were propagated either in vivo or in vitro in cells derived from Indian monkeys, this may have resulted in the selection of viral variants that are adapted for more efficient replication and/or increased pathogenicity for these animals (34).

Here, we report the results of a comparative study of the initial interactions between SIV and the host immune system in two different species of NHPs that exhibit divergent outcomes of the infection, i.e., nonnatural RM hosts, in which the infection leads to CD4+ T-cell depletion and AIDS, and natural AGM hosts, in which the infection is typically nonpathogenic. To investigate the potential immunopathogenic role of lymphocyte apoptosis in LNs occurring during the primary phase of infection, we performed a longitudinal study of 20 experimentally SIV-infected NHPs (6 Indian RMs and 8 Chinese RMs infected with SIVmac251 and 6 AGMs infected with SIVagm-sab). We examined the frequency of (i) SIV RNA+ cells, (ii) apoptotic cells (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling positive [TUNEL+]), (iii) TiA-1+ cells, and (iv) cycling Ki67+ cells in this diverse array of pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate models that are associated with peculiar rates of progression to AIDS (or lack thereof). Our data demonstrate that the early levels of apoptosis and immune activation are key events associated with progression to AIDS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and virus infection.

The following animals were included in this study: (i) 14 RMs of either Indian (n = 6) or Chinese (n = 8) origin were intravenously inoculated with 10 50% animal infectious doses of the pathogenic SIVmac251 and (ii) 6 AGMs of the sabaeus species were experimentally infected with 300 50% tissue culture infective doses of the SIVagm.sab92018 strain. As previously described, this virus derives from a naturally infected AGM and has never been cultured in vitro (6). The pathogenic SIVmac251 isolate was initially provided by R. Desrosiers and titrated in Chinese RMs (Macaca mulatta) by intravenous inoculation. A 1-ml volume of stock virus contained 4 × 104 50% animal infectious doses, as previously described (25). Animals were demonstrated to be seronegative for simian T-leukemia virus type 1, simian retrovirus type 1, herpes B viruses, and SIVs. The animals were housed and cared for in compliance with existing French regulations (http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/animalerie/fichiers/Decret2001-486.pdf).

Determination of viral load and quantitative assessment of productively infected cells.

RNA was extracted from the plasma of SIV-infected monkeys, using the Tri Reagent BD Kit (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH). Real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR was used to determine viral loads as previously described (25). The inguinal and axillary LNs were sequentially collected from each animal during the course of primary infection. The LNs were frozen in isopentane cooled in liquid nitrogen and then cryostat sectioned at 4-μm intervals. Viral replication in LNs was assessed by in situ hybridization using a 35S-labeled RNA probe as previously described (25). Infected cells, detected as spots, were counted in the paracortical zone on a minimum of three sections using a Nikon FXA microscope. The number of positive cells (counted as spots) was then divided by the surface area of the entire LN section, and the results were expressed as the number of positive cells per 2-mm2 section. The mean count obtained for three slides of the same LNs, in a blinded fashion, by two investigators was calculated.

Quantitative assessment of apoptotic cells.

Apoptotic cells were identified using the TUNEL assay, which detects DNA fragmentation usually associated with apoptosis, as previously described (25). Briefly, cryostat tissue sections were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and overlaid with TUNEL reaction mixture containing terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase (Boerhinger Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and digoxigenin-dUTP. The sections were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The sections of LN were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with a sheep anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase antibody for 40 min at 37°C and revealed with naphthol AS-MX, fast red, and levamisol. LN sections were counterstained using Harris hematoxylin and mounted with gelatin. The number of positive cells in the T-cell areas was then divided by the surface area of the entire LN section, and the results were expressed as the number of positive cells per 2-mm2 section. The mean count obtained for three slides of the same LNs, in a blinded fashion, by two investigators was calculated.

Quantitative assessment of cycling cells.

Cycling cells were assessed using a monoclonal antibody to the Ki67 nuclear proliferation-associated antigen (MIB-1; Immunotech, Inc., Marseille, France) that is expressed at all phases of the cell cycle except the G0 phase. Alkaline phosphatase was used as the chromogen, and the slides were slightly counterstained with hematoxylin as previously described (25). The numbers of LN-positive cells counted in the T-cell areas were then divided by the surface area of the entire LN section, and the results were expressed as the number of positive cell per 2-mm2 section. The proportion of cycling cells in the B-cell areas (germinal centers [GCs]) was quantified and divided by the surface area of the entire LN section. The results were expressed as a percentage per 2-mm2 section (%GCKi67+). The proportion obtained for three slides of the same LNs, in a blinded fashion, by two investigators was calculated.

Quantitative assessment of TiA-1 cells.

TiA-1 cells were assessed using a monoclonal antibody (clone GMP-17; Beckman Coulter). Alkaline phosphatase was used as the chromogen, and the slides were slightly counterstained with hematoxylin. The proportion of TiA-1+ cells counted in the T-cell areas was then divided by the surface area of the entire LN section, and the results were expressed as a percentage per 2-mm2 section (TiA-1 cells/mm2). These analyses were performed on four different sections, in a blind fashion, by two investigators.

Lymphocyte immunophenotyping by flow cytometry.

T cells were stained with the following fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies: anti-rhesus monkey CD3 conjugated with fluorescein-isothiocyanate (clone FN18; Biosource International), anti-human CD4 conjugated with phycoerythrin (clone M-T477; BD Biosciences), anti-human CD8 conjugated with peridinin-chlorophyll protein (BD Biosciences), and anti-HLA-DR conjugated with allophycocyanin (L243; BD Biosciences). Antibodies were added to 100 μl of 2 × 105 LN cells. The cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then washed once in PBA buffer (phosphate-buffered saline-1% bovine serum albumin-10 mM NaN3) and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% paraformaldehyde as previously described (26).

Statistical analyses.

Student's t tests and the Mann-Whitney U test (Prism software) were used to determine whether differences were significant (P < 0.05). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare results between monkey species. Spearman's rank correlation, implemented in Statistica software, was use to evaluate correlations. Best-fit lines are shown.

RESULTS

Viral replication and disease outcomes.

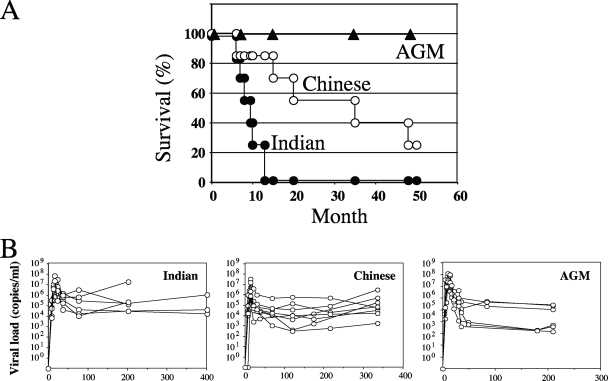

RMs of Indian genetic background progressed more rapidly toward AIDS than Chinese RMs despite receiving a similar viral stock of the SIVmac251 strain that was produced in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of Chinese monkeys. In this study, all Indian RMs were sacrificed due to the onset of AIDS-related symptoms before 1 year of infection, while half of the SIV-infected Chinese RMs were alive after 36 months of infection. As expected, all the SIV-infected AGMs were alive >48 months postinfection (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Survival by month. The percentages of survival in three different groups of SIV-infected monkeys (Indian RMs and Chinese RMs infected with SIVmac251 and AGMs infected with SIVagm.sab92018) during the follow-up period of this study are shown. Clinical progression toward disease was continuously evaluated. The animals were killed due to a wasting syndrome with cachexia and opportunistic infections. (B) Viremia. Shown are kinetic analyses of viremia in SIV-infected Indian and Chinese RMs and in AGMs.

During acute SIV infection, the initial burst of viral replication causes an exponential increase in the plasma viral load that leads to the dissemination of the virus throughout the body and the infection of the CD4+ T cells in the MALT (42), as well as in peripheral lymphoid organs, which are the main sites of both virus replication and immune response to the virus. As shown in Fig. 1B, we first assessed the dynamics of the viral loads in these different groups of SIV-infected NHPs. In RMs, viremia peaked between days 11 and 14, with values ranging between 7.5 × 106 and 7 × 107 copies/ml in RMs of Indian origin and between 6.7 × 105 and 3.2 × 107 copies/ml in Chinese RMs. In AGMs, viremia peaked between days 8 and 14, and the values ranged between 7.9 × 106 and 1.2 × 108 copies/ml. The set point levels in AGMs ranged between 1.3 × 103 and 2.5 × 105 copies/ml, whereas in Indian RMs and Chinese RMs, it ranged between 3 × 104 and 1.8 × 107 copies/ml and 3 × 102 and 5.7 × 105 copies/ml, respectively. Thus, these data are consistent with numerous previous observations (13, 19, 21, 25, 27, 32, 41, 45) in indicating that both peak and set point viremias are similar in pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate models.

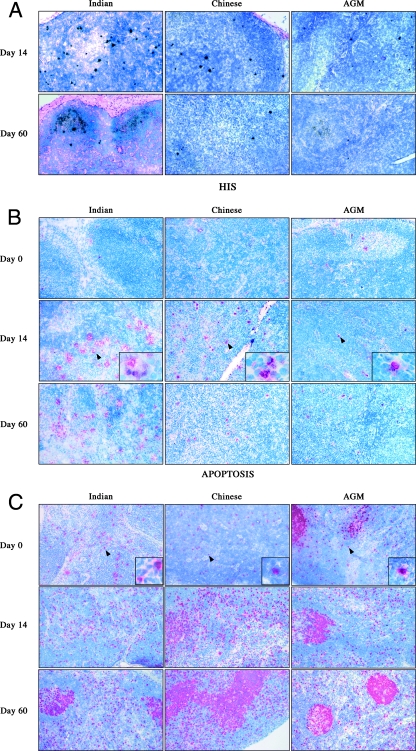

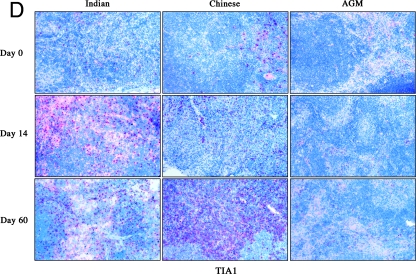

To longitudinally assess the relationship between the level of the early viral dissemination/seeding and the immune system dynamics (i.e., proliferation and cell death), we sequentially collected the inguinal and axillary LNs from each animal during the course of primary infection. In all examined tissues, SIV RNA+ cells were promptly detected in the pathogenic, as well as in the nonpathogenic, models (Fig. 2A). During the acute phase of SIVmac251 infection of RMs, the peak numbers of productively infected cells per surface unit in the LN T-cell area was reached at days 11 to 14 postinfection, i.e., coincident with the peak of the viral loads, and was followed by a significant decrease by day 60 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the level of viral replication in LNs was significantly higher in RMs of Indian origin than in Chinese RMs, with peak numbers of productively infected cells of 204.8 ± 125 SIV RNA+ cells/2 mm2 and 30.8 ± 19.7 SIV RNA+ cells/2 mm2, respectively (P = 0.007, using the Mann-Whitney U test) (Fig. 3). Similarly, the frequency of CD4+ T cells harboring proviral DNA at the peak values was higher in Indian than in Chinese RMs (0.043 ± 0.038 and 0.017 ± 0.009, respectively) (data not shown). This difference persisted at day 60, with the numbers of SIV RNA+ cells per 2 mm2 higher in Indian than in Chinese RMs (14.2 ± 11.2 and 7.9 ± 8.8, respectively). Most importantly, we found that the numbers of SIV RNA+ cells per 2 mm2 in AGMs at the peak of virus replication (21 ± 12.5) were relatively similar to those observed at the peak in SIVmac251-infected Chinese RMs (Fig. 3). However, it should be noted that at day 60, the number of SIV RNA+ cells per 2 mm2 in LNs was extremely low in AGMs (0.53 ± 0.22), despite similar levels of viral load in the two species.

FIG. 2.

SIV RNA+ cells (A) and immunohistochemical analysis of apoptotic cells (B), of cycling cells (C), and of TiA-1 (D) in LNs from Indian and Chinese SIVmac251-infected RMs and SIVagm-infected AGMs at different time points after infection. Magnification, ×100.

FIG. 3.

Productive SIV infection in LNs from Indian and Chinese SIVmac251-infected RMs and SIVagm-infected AGMs at different time points postinfection. Quantitative assessment of SIV RNA+ cells is shown. Statistical significance was assessed using paired Student t tests. The error bars represent standard deviations.

These findings suggest that the level of peak viral replication in the LNs is not discriminative of pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate models of SIV infection (with Indian RMs nevertheless showing higher frequencies of infected cells and faster disease progression than Chinese RMs). Interestingly, the level of viral replication in peripheral LNs during the set point phase of SIV infection was higher in SIVmac251-infected RMs than in SIVagm-sab-infected AGMs, suggesting that other anatomic sites (i.e., MALT, spleen, etc.) are responsible for the high plasma viremia of AGMs.

LN apoptosis is a typical feature of pathogenic SIV infections.

We then sought to determine, in the same groups of SIV-infected NHPs, the extent of apoptotic cells in LNs. The numbers of apoptotic cells were quantified in the T-cell areas of tissue sections from the same LNs in which the numbers of SIV-infected cells were previously assessed (Fig. 2B). We found that the numbers of apoptotic cells increased after infection and reached their highest levels at the time of peak viral replication in both Indian and Chinese RMs (day 14, 138 ± 66 cells/2 mm2 and 77 ± 16 cells/2 mm2, respectively; P = 0.04, using the Mann-Whitney U test). The numbers of apoptotic cells remained higher at day 60 (Indian, 58 ± 59 cells/2 mm2 versus Chinese, 16 ± 7 cells/mm2; P = 0.04) than before infection (8 ± 6 cells/mm2) (Fig. 4A). Importantly, a significant direct correlation was found in SIVmac251-infected RMs between the level of viral replication within LNs (as measured at the time of peak viremia) and the numbers of apoptotic cells (Fig. 4B). In SIVagm-infected AGMs, the level of T-cell apoptosis in the LNs remained similar to the baseline throughout the acute phase of infection (day 13, 25 ± 28 cells/ 2 mm2, and day 60, 27 ± 9 cells/2 mm2). The observation that T-cell apoptosis did not increase in AGMs during early SIV infection despite levels of viral replication that were similar to those observed in SIVmac251-infected Chinese RMs suggests that indirect (i.e., non-virus-related) mechanisms rather than the direct effect of viral replication are responsible for the increased rate of apoptotic cells in RMs.

FIG. 4.

(A) Quantitative assessment of apoptotic cells measured by the Tunel method in LNs from Indian and Chinese SIVmac251-infected RMs and SIVagm-infected AGMs at different time points postinfection. Statistical significance was assessed using paired Student t tests. The error bars represent standard deviations. (B) Correlation between the extent of viral replication (log SIV RNA+) and the extent of apoptosis at the peak. Each symbol represents one individual RM, either Indian (○) or Chinese (•).

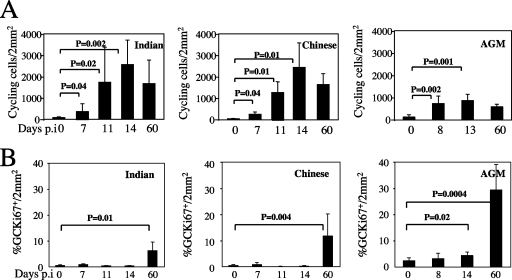

Dynamics of cycling cells in the T-cell area.

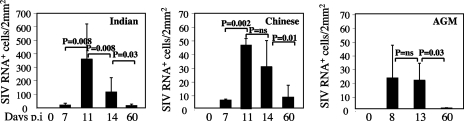

To investigate the relationship between the extent of LN apoptosis and the level of immune activation (which results in frequent events of activation-induced cell death [17]), we first assessed the level of activated (Ki67+) lymphocytes in our group of animals. We found that, in both Indian and Chinese SIVmac251-infected RMs, the paracortical areas (T-cell zone) contained more activated cells than those of uninfected RMs (Fig. 2C). The number of cycling cells peaked at days 11 to 14 postinfection (day 14, 2,537 ± 1,154 cells/2 mm2 and 2,430 ± 1,130 cells/2 mm2 in Indian and Chinese RMs, respectively) and remained much higher than baseline at day 60 (1,655 ± 1,099 cells/2 mm2 and 1,626 ± 502 cells/2 mm2 in Indian and Chinese RMs, respectively, versus day 0, with 5 ± 25 cells/2 mm2) (Fig. 5A). Of note, the differences in Ki67+ cells between Indian and Chinese RMs were not statistically significant, suggesting that the higher level of apoptotic cells observed during primary SIVmac251 infection of Indian RMs is not simply a consequence of greater numbers of cycling T cells.

FIG. 5.

Quantitative assessment of Ki67 in the T-cell area (A) and B-cell area (%GCKi67+) (B) in LNs from Indian and Chinese SIVmac251-infected RMs and SIVagm-infected AGMs at different time points postinfection. Statistical significance was assessed using paired Student t tests. The error bars represent standard deviations.

We next measured the numbers of cycling lymphocytes in SIVagm-infected AGMs and found that cycling cells peaked at day 8 (739 ± 173 cells/2 mm2 versus day 0, with 133 ± 103 cells/2 mm2; P = 0.002) with a slight decrease thereafter (day 60, 596 ± 110 cells/2 mm2), which was coincident with the decline of viral replication in LNs (Fig. 5A). While SIV-infected AGMs showed a clear increase in the numbers of cycling T cells compared to baseline (i.e., prior to infection), the absolute levels of T-cell activation in the LNs of these animals were approximately one-third lower than those observed in SIVmac251-infected RMs (Fig. 5A). Therefore, this result is consistent with previous reports indicating that nonpathogenic SIV infection of natural hosts is associated with lower levels of immune activation (8, 40).

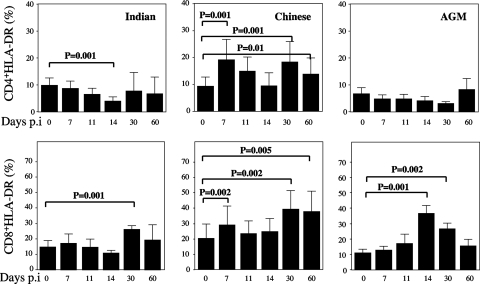

To further characterize the dynamics of T-cell activation in our group of NHPs, we next assessed by flow cytometry the changes in the levels of CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ T cells expressing HLA-DR in peripheral blood. Interestingly, SIVmac251-infected Indian RMs revealed a profound decrease in the percentage of CD4+ DR+ T cells while only a transient decline of CD4+ DR+ T cells was observed at the peak of virus replication in Chinese monkeys (Fig. 6). Moreover, we found an early increase in the fraction of CD8+ DR+ T cells in Chinese RMs that still persisted at the time of set point viremia (Fig. 6). In SIV-infected AGMs, we found a transitory increase in the activation status of CD8+ T cells (but not CD4+ T cells), with levels of CD8+ DR+ T cells peaking at day 14 but soon returning to levels similar to those observed prior to infection. This pattern of T-cell activation in SIVagm-infected AGMs is very similar to that previously reported by our laboratory and others (19, 32).

FIG. 6.

Dynamics of HLA-DR on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in LNs. Flow cytometry was used to quantify the percentages of T cells expressing HLA-DR gating on CD3+ cells of Indian and Chinese SIVmac251-infected RMs and SIV-infected AGMs at different time points postinfection. The data shown were calculated as follows: DR+ CD4/CD8+/(DR+ CD4/CD8+ + DR− CD4/CD8+) × 100. Statistical significance was assessed using paired Student t tests. Error bars represent standard deviations.

While our data failed to identify any significant correlation between the extent of T-cell activation and the rate of apoptosis in pathogenic SIVmac251 infection of RMs, it was clearly apparent that, in the nonpathogenic SIVagm infection of AGMs, an attenuated level of T-cell activation was associated with lower levels of apoptosis.

Dynamics of cycling cells in the B-cell area.

We next assessed the level of activated cells in the B-cell zone by staining the GCs. In contrast to the large increase of cycling cells in the T-cell area observed in SIVmac251-infected RMs, no changes in the level of cycling cells in the B-cell area (%GCKi67+/2 mm2) was found in the same animals at the peak of viral replication. Interestingly, the level of B-cell activation within the GC was three- to fivefold higher in SIV-infected AGMs than in RMs at day 60, with 29.3% ± 9.7% %GCKi67+/2 mm2 in AGMs, 11.2% ± 8.1% in Chinese RMs, 6.2% ± 3.1% in Indian RMs (P = 0.008), and 0.155% ± 0.25% in uninfected animals (Fig. 5B). We also found that the percentage of CD20+ CD3− cells (B cells), as analyzed by flow cytometry at day 60 postinfection, was increased in LNs of SIV-infected AGMs (28.3% ± 3.5%) compared to preinfection values (15.2% ± 1.7%). These dynamics are consistent with the time of detection of SIV-specific antibodies in the plasma that appeared between days 30 and 60 (data not shown) and suggest that immune responses to SIV involve predominantly humoral immunity in AGMs.

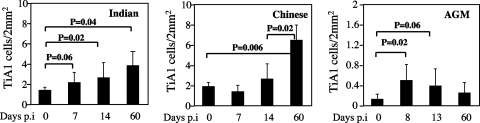

Dynamics of TiA-1+ cells.

To further characterize the early activation of CD8+ T cells observed during SIV infection of RMs and AGMs, we examined the expression of cytolytic granules by staining TiA-1 protein localized to the granules of cytolytic T cells that is functionally related to perforin. In these experiments, we assessed TiA-1 expression in situ to exclude the possibility that isolated lymphocytes might release their granule contents during the isolation procedure (Fig. 2D). We found that, in the LNs of SIVagm-infected AGMs, the fraction of TiA-1-expressing cells showed an early moderate increase (day 8, 0.5% ± 0.3% versus day 0, 0.13% ± 0.1%; P = 0.018) followed by a slight decline by the time of set point viremia (day 60, 0.25% ± 0.2%) (Fig. 7). Thus, the dynamics of TiA-1 expression in AGMs followed the dynamics observed for the proportion of activated CD8+ T cells.

FIG. 7.

Quantitative assessment of TiA-1 cells in LNs from Indian and Chinese SIVmac251-infected RMs and SIVagm-infected AGMs at different time points postinfection. Statistical significance was assessed using paired Student t tests. The error bars represent standard deviations.

In SIVmac251-infected RMs, the frequency of TiA-1-expressing T-cells increased earlier in Indian animals than in Chinese animals. However, at day 60 postinfection, the level of TiA-1 reactivity in SIVmac251-infected Chinese RMs was greater than before infection (6.5% ± 1.5% versus 1.9% ± 0.39%; P = 0.006) and greater than in Indian RMs (3.9% ± 1.6%; P = 0.02) (Fig. 7). These dynamics of TiA-1 expression in LNs during SIVmac251 infection of RMs were consistent with the observed pattern of CD8+ DR+ T-cell dynamics.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the results of a detailed longitudinal study of a large number (n = 20) of NHPs experimentally infected with SIV, including six Indian and eight Chinese RMs infected with SIVmac251 and six AGMs infected with SIVagm-sab. The key goal of this study was to assess, in the different NHP models of infection, the relationship between virus replication, immune activation, lymphocyte apoptosis, and disease progression. A key premise of this study was the observation that, in striking contrast to HIV-infected humans and SIVmac-infected RMs, natural SIV hosts, such as AGMs, SMs, and mandrills, typically remain asymptomatic despite similarly high levels of virus replication (2, 6, 8, 14, 15, 19, 29, 32, 40). It is now widely accepted that understanding the mechanisms underlying the different infection outcomes in natural versus nonnatural SIV hosts provides important clues as to the mechanisms of AIDS pathogenesis.

SIVmac infection of Chinese RMs is less pathogenic than that of Indian RMs and thus more closely mimics the course of HIV infection in humans (4, 26, 27). As some of these earlier experiments were conducted using virus preparations obtained through repeated serial passage in cells from Indian RMs (or in Indian RMs in vivo), it was proposed that increased viral fitness from Indian RM cells may explain the higher replicative capacity and faster disease progression in these animals. However, in our experiments, we used a SIVmac251 strain that had been in vitro passaged in peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from Chinese RMs. We still observed an accelerated course of disease in Indian RMs, suggesting that host factors, rather than intrinsic properties of SIV, are key determinants of the divergent infection outcomes in RMs.

Our study also confirmed and extended previous evaluations of viral dynamics in peripheral blood, demonstrating that levels of viral replication in RMs and AGMs are quite similar. Importantly, by the end of the acute phase of infection, a clear difference emerged between AGMs and RMs in terms of viral replication in LNs, with numbers of SIV RNA+ cells that were significantly lower in SIV-infected AGMs than those observed in RMs (the numbers in Indian RMs were higher than those in Chinese RMs). These data indicate that the level of virus replication in the LNs at the end of the acute phase may be a good predictor of disease progression in RMs (25-27) and that in AGMs, the level of viral particles in the blood likely reflects virus replication occurring in sites other than peripheral LNs, such as the MALT or spleen.

The data included in the current study strongly suggest that the extent of apoptotic cell death occurring in the T-cell areas of the peripheral LNs represents an early pathogenic event that seems to determine the subsequent course of disease progression. The fact that SIVagm-infected AGMs do not display any major increase in T-cell apoptosis in the context of significant levels of viral replication suggests that the direct effects of SIV replication alone are unlikely to account for the high levels of T-cell apoptosis observed in RMs at the time of peak viremia. Instead, our observation is consistent with a model in which large numbers of T cells undergo apoptosis as a consequence of a massive event of immune activation. Interestingly, in RMs, we found a positive correlation between the level of viral replication in the LNs and the extent of T-cell apoptosis, suggesting either a role, at least partial, for viral-replication-mediated cell death in these animals or, alternatively, a role for SIV antigens in determining, through the generation of virus-specific immune responses, the prevailing levels of immune activation and apoptosis. In other studies, we showed that the extent of apoptosis in peripheral LNs was greater in Chinese RMs infected with pathogenic SIVmac than in those infected with a SIVmac strain with nef deleted and predicted, in these animals, the risk of progression to AIDS (25, 43). Together, these results suggest that in SIV-infected RMs, increased levels of apoptosis represent a key determinant of progressive immunodeficiency, consistent with previous studies performed during the chronic phase of HIV and SIV infections (8, 9, 12, 17, 26, 27). In this context, it is tempting to speculate that an additional deleterious effect of the increased T-cell death observed in SIVmac251-infected RMs is the inability of the immune system to mount a sustained immune response to the virus (43).

Together, these findings suggest that the level of lymphocyte apoptosis in the early stages of SIV infection is a species-specific surrogate marker of AIDS pathogenesis. In this study, it was clearly apparent that, in the nonpathogenic SIVagm infection of AGMs, an attenuated T-cell activation was associated with lower levels of apoptosis during the acute phase. This new finding is consistent with earlier reports indicating, during the chronic phase of SIV infection, a relationship between the extent of immune activation, T-cell apoptosis, and pathogenesis (8, 40). This absence of immune activation in SIV-infected AGMs might be related to an early anti-inflammatory profile characterized by the induction of T-regulator cells (19). Interestingly, SIV-infected AGMs showed smaller LNs than RMs (data not shown), further suggesting that the “total-body” level of immune activation is significantly lower during nonpathogenic infections of natural SIV hosts.

The increase of TiA-1-expressing T cells in LNs concomitant with the observation of a transient increase of activated CD8+ T cells (DR+) during the acute viral-replication period in AGMs is consistent with recent reports (13, 32). This observation supports the hypothesis that the postpeak decline in virus replication observed in the LNs of SIVagm-infected AGMs might be, at least in part, related to the emergence of cellular immune responses to the virus. On the other hand, however, it should be noted that to date there is no experimental evidence indicating that in SIV-infected AGMs (or any other natural SIV hosts) the cellular immune responses to the virus are broader or more potent/effective that those described in pathogenic HIV-1 and SIV infections (7). Alternatively, the observed low levels of activated CD4+ T cells (DR+) in SIV-infected AGMs may suggest that the postpeak decrease of the viral load in the LNs of SIVagm-infected AGMs is related to the rapid exhaustion of target cells due to the attenuated levels of local T-cell activation.

Interestingly, we found a clear difference in the dynamics of T and B cells between AGMs and RMs. SIVmac251-infected RMs showed more extensive and persistent proliferation of T cells than SIVagm-infected AGMs. Conversely, SIVagm-infected AGMs showed a more prominent B-cell activation than SIVmac251-infected RMs, as manifested by the level of Ki67+ cells in the GCs at the set point compared to that in RMs. This observation is also consistent with two recent reports indicating that SIV infection of AGMs is associated with high levels of Ki67+ cells in the GCs and rapid expansion of B cells (13, 32). While these results seem at odds with the observation that the titers of SIV-specific antibodies are lower in AGMs than in RMs (28), it should be noted that large fractions of Ki67+ GC cells do not necessarily translate into high titers of SIV-specific antibody. In any event, our intriguing observation of an early and selective B-cell response during nonpathogenic SIVagm infection of AGMs suggest that the role of SIV-specific humoral responses in primate lentiviral infections should be further explored in future studies, particularly with respect to the impact of SIV-specific antibodies in the control and/or compartmentalization of viral replication at the end of the acute phase.

A question that remains to be answered is how host genetic factors may influence the strikingly different levels of lymphocyte apoptosis in LNs that we observed during early SIV infection in the various NHP models studied. A first possibility is that individual differences in the signaling pathways that participate in immune activation and apoptosis regulation may lead to different sensitivities to death signal transduction induced either by viral proteins or by death ligands and receptors (such as CD95 ligand and CD95) (9, 11). A role has recently been proposed for CD95/CD95 ligand in the depletion of uninfected CD4+ T cells occurring during primary infection in the lamina propria of SIV-infected RMs (20). As the extent of T-cell activation is typically lower in AGMs than in RMs, species-specific differences in the immunomodulatory activity of T-regulator cells might be beneficial in controlling T-cell activation and activation-induced cell death (19). A second possibility is that differences in the induction of apoptosis are related to quantitative differences in the initial levels of coreceptor expression. Several studies have suggested that coreceptor expression affects disease progression in HIV-infected individuals (3, 23, 38) as the proportion of CD4+ expressing CCR5+ and/or the density of cell surface CCR5 correlates with disease progression (5, 30). Moreover, a difference has recently been reported in the level of CCR5 between pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate models of AIDS (33). Finally, we recently demonstrated that in addition to CCR5, ligation of GPR15 (BOB), an additional coreceptor utilized by the SIVmac251 strain, mediates CD4+ T-cell death (43). However, the dynamics of CD4+ T cells expressing this coreceptor are still unknown.

In conclusion, the current set of data is clearly consistent with the hypothesis that the prevailing levels of immune activation and T-cell apoptosis are key markers of disease progression during pathogenic primate lentiviral infections. Similarly, this work supports the concept that limited immune activation and low levels of T-cell apoptosis are instrumental in avoiding progression to AIDS in AGMs and other natural SIV hosts, as well.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida et les Hépatites Virales (ANRS), Sidaction, Fondation de France, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale to J.E. L.V. was supported by a fellowship from ANRS, and S.L. was supported by Sidaction.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 November 2007.

This work is dedicated to Bruno Hurtrel.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnoult, D., F. Petit, J. D. Lelievre, D. Lecossier, A. Hance, V. Monceaux, B. Hurtrel, R. Ho Tsong Fang, J. C. Ameisen, and J. Estaquier. 2003. Caspase-dependent and -independent T-cell death pathways in pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection: relationship to disease progression. Cell Death Differ. 101240-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broussard, S. R., S. I. Staprans, R. White, E. M. Whitehead, M. B. Feinberg, and J. S. Allan. 2001. Simian immunodeficiency virus replicates to high levels in naturally infected African green monkeys without inducing immunologic or neurologic disease. J. Virol. 752262-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean, M., M. Carrington, C. Winkler, G. A. Huttley, M. W. Smith, R. Allikmets, J. J. Goedert, S. P. Buchbinder, E. Vittinghoff, E. Gomperts, S. Donfield, D. Vlahov, R. Kaslow, A. Saah, C. Rinaldo, R. Detels, S. J. O'Brien, et al. 1996. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science 2731856-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deeks, S. G., C. M. Kitchen, L. Liu, H. Guo, R. Gascon, A. B. Narvaez, P. Hunt, J. N. Martin, J. O. Kahn, J. Levy, M. S. McGrath, and F. M. Hecht. 2004. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood 104942-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Roda Husman, A. M., H. Blaak, M. Brouwer, and H. Schuitemaker. 1999. CC chemokine receptor 5 cell-surface expression in relation to CC chemokine receptor 5 genotype and the clinical course of HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 1634597-4603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diop, O. M., A. Gueye, M. Dias-Tavares, C. Kornfeld, A. Faye, P. Ave, M. Huerre, S. Corbet, F. Barre-Sinoussi, and M. C. Muller-Trutwin. 2000. High levels of viral replication during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm infection are rapidly and strongly controlled in African green monkeys. J. Virol. 747538-7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunham, R., P. Pagliardini, S. Gordon, B. Sumpter, J. Engram, A. Moanna, M. Paiardini, J. N. Mandl, B. Lawson, S. Garg, H. M. McClure, Y. X. Xu, C. Ibegbu, K. Easley, N. Katz, I. Pandrea, C. Apetrei, D. L. Sodora, S. I. Staprans, M. B. Feinberg, and G. Silvestri. 2006. The AIDS resistance of naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys is independent of cellular immunity to the virus. Blood 108209-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estaquier, J., T. Idziorek, F. de Bels, F. Barre-Sinoussi, B. Hurtrel, A. M. Aubertin, A. Venet, M. Mehtali, E. Muchmore, P. Michel, et al. 1994. Programmed cell death and AIDS: significance of T-cell apoptosis in pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate lentiviral infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 919431-9435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estaquier, J., T. Idziorek, W. Zou, D. Emilie, C. M. Farber, J. M. Bourez, and J. C. Ameisen. 1995. T helper type 1/T helper type 2 cytokines and T cell death: preventive effect of interleukin 12 on activation-induced and CD95 (FAS/APO-1)-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. J. Exp. Med. 1821759-1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estaquier, J., V. Monceaux, M. C. Cumont, A. M. Aubertin, B. Hurtrel, and J. C. Ameisen. 2000. Early changes in peripheral blood T cells during primary infection of rhesus macaques with a pathogenic SIV. J. Med. Primatol. 29127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estaquier, J., M. Tanaka, T. Suda, S. Nagata, P. Golstein, and J. C. Ameisen. 1996. Fas-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons: differential in vitro preventive effect of cytokines and protease antagonists. Blood 874959-4966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkel, T. H., G. Tudor-Williams, N. K. Banda, M. F. Cotton, T. Curiel, C. Monks, T. W. Baba, R. M. Ruprecht, and A. Kupfer. 1995. Apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander cells and not in productively infected cells of HIV- and SIV-infected lymph nodes. Nat. Med. 1129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein, S., C. R. Brown, I. Ourmanov, I. Pandrea, A. Buckler-White, C. Erb, J. S. Nandi, G. J. Foster, P. Autissier, J. E. Schmitz, and V. M. Hirsch. 2006. Comparison of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagmVer replication and CD4+ T-cell dynamics in vervet and sabaeus African green monkeys. J. Virol. 804868-4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein, S., I. Ourmanov, C. R. Brown, B. E. Beer, W. R. Elkins, R. Plishka, A. Buckler-White, and V. M. Hirsch. 2000. Wide range of viral load in healthy African green monkeys naturally infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 7411744-11753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gueye, A., O. M. Diop, M. J. Ploquin, C. Kornfeld, A. Faye, M. C. Cumont, B. Hurtrel, F. Barre-Sinoussi, and M. C. Muller-Trutwin. 2004. Viral load in tissues during the early and chronic phase of non-pathogenic SIVagm infection. J. Med. Primatol. 3383-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holzammer, S., E. Holznagel, A. Kaul, R. Kurth, and S. Norley. 2001. High virus loads in naturally and experimentally SIVagm-infected African green monkeys. Virology 283324-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurtrel, B., F. Petit, D. Arnoult, M. Muller-Trutwin, G. Silvestri, and J. Estaquier. 2005. Apoptosis in SIV infection. Cell Death Differ. 12(Suppl. 1)979-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur, A., R. M. Grant, R. E. Means, H. McClure, M. Feinberg, and R. P. Johnson. 1998. Diverse host responses and outcomes following simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 infection in sooty mangabeys and rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 729597-9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornfeld, C., M. J. Ploquin, I. Pandrea, A. Faye, R. Onanga, C. Apetrei, V. Poaty-Mavoungou, P. Rouquet, J. Estaquier, L. Mortara, J. F. Desoutter, C. Butor, R. Le Grand, P. Roques, F. Simon, F. Barre-Sinoussi, O. M. Diop, and M. C. Muller-Trutwin. 2005. Antiinflammatory profiles during primary SIV infection in African green monkeys are associated with protection against AIDS. J. Clin. Investig. 1151082-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, Q., L. Duan, J. D. Estes, Z. M. Ma, T. Rourke, Y. Wang, C. Reilly, J. Carlis, C. J. Miller, and A. T. Haase. 2005. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 4341148-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lifson, J. D., M. A. Nowak, S. Goldstein, J. L. Rossio, A. Kinter, G. Vasquez, T. A. Wiltrout, C. Brown, D. Schneider, L. Wahl, A. L. Lloyd, J. Williams, W. R. Elkins, A. S. Fauci, and V. M. Hirsch. 1997. The extent of early viral replication is a critical determinant of the natural history of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 719508-9514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling, B., R. S. Veazey, A. Luckay, C. Penedo, K. Xu, J. D. Lifson, and P. A. Marx. 2002. SIVmac pathogenesis in rhesus macaques of Chinese and Indian origin compared with primary HIV infections in humans. AIDS 161489-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, R., W. A. Paxton, S. Choe, D. Ceradini, S. R. Martin, R. Horuk, M. E. MacDonald, H. Stuhlmann, R. A. Koup, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell 86367-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellors, J. W., C. R. Rinaldo, Jr., P. Gupta, R. M. White, J. A. Todd, and L. A. Kingsley. 1996. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science 2721167-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monceaux, V., J. Estaquier, M. Fevrier, M. C. Cumont, Y. Riviere, A. M. Aubertin, J. C. Ameisen, and B. Hurtrel. 2003. Extensive apoptosis in lymphoid organs during primary SIV infection predicts rapid progression towards AIDS. AIDS 171585-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monceaux, V., R. Ho Tsong Fang, M. C. Cumont, B. Hurtrel, and J. Estaquier. 2003. Distinct cycling CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell profiles during the asymptomatic phase of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac251 infection in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 7710047-10059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monceaux, V., L. Viollet, F. Petit, R. Ho Tsong Fang, M. C. Cumont, J. Zaunders, B. Hurtrel, and J. Estaquier. 2005. CD8+ T cell dynamics during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in macaques: relationship of effector cell differentiation with the extent of viral replication. J. Immunol. 1746898-6908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norley, S. G., G. Kraus, J. Ennen, J. Bonilla, H. Konig, and R. Kurth. 1990. Immunological studies of the basis for the apathogenicity of simian immunodeficiency virus from African green monkeys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 879067-9071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onanga, R., C. Kornfeld, I. Pandrea, J. Estaquier, S. Souquiere, P. Rouquet, V. P. Mavoungou, O. Bourry, S. M'Boup, F. Barre-Sinoussi, F. Simon, C. Apetrei, P. Roques, and M. C. Muller-Trutwin. 2002. High levels of viral replication contrast with only transient changes in CD4+ and CD8+ cell numbers during the early phase of experimental infection with simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmnd-1 in Mandrillus sphinx. J. Virol. 7610256-10263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostrowski, M. A., S. J. Justement, A. Catanzaro, C. A. Hallahan, L. A. Ehler, S. B. Mizell, P. N. Kumar, J. A. Mican, T. W. Chun, and A. S. Fauci. 1998. Expression of chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in HIV-1-infected and uninfected individuals. J. Immunol. 1613195-3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oxenius, A., D. A. Price, P. J. Easterbrook, C. A. O'Callaghan, A. D. Kelleher, J. A. Whelan, G. Sontag, A. K. Sewell, and R. E. Phillips. 2000. Early highly active antiretroviral therapy for acute HIV-1 infection preserves immune function of CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 973382-3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandrea, I., C. Apetrei, J. Dufour, N. Dillon, J. Barbercheck, M. Metzger, B. Jacquelin, R. Bohm, P. A. Marx, F. Barre-Sinoussi, V. M. Hirsch, M. C. Muller-Trutwin, A. A. Lackner, and R. S. Veazey. 2006. Simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm.sab infection of Caribbean African green monkeys: a new model for the study of SIV pathogenesis in natural hosts. J. Virol. 804858-4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandrea, I., C. Apetrei, S. N. Gordon, J. Barbercheck, J. Dufour, R. Bohm, B. S. Sumpter, P. Roques, P. A. Marx, V. M. Hirsch, A. Kaur, A. A. Lackner, R. S. Veazey, and G. Silvestri. 2006. Paucity of CD4+CCR5+ T-cells is a typical feature of natural SIV hosts. Blood 1091069-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reimann, K. A., R. A. Parker, M. S. Seaman, K. Beaudry, M. Beddall, L. Peterson, K. C. Williams, R. S. Veazey, D. C. Montefiori, J. R. Mascola, G. J. Nabel, and N. L. Letvin. 2005. Pathogenicity of simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV-89.6P and SIVmac is attenuated in cynomolgus macaques and associated with early T-lymphocyte responses. J. Virol. 798878-8885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rey-Cuille, M. A., J. L. Berthier, M. C. Bomsel-Demontoy, Y. Chaduc, L. Montagnier, A. G. Hovanessian, and L. A. Chakrabarti. 1998. Simian immunodeficiency virus replicates to high levels in sooty mangabeys without inducing disease. J. Virol. 723872-3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberg, E. S., M. Altfeld, S. H. Poon, M. N. Phillips, B. M. Wilkes, R. L. Eldridge, G. K. Robbins, R. T. D'Aquila, P. J. Goulder, and B. D. Walker. 2000. Immune control of HIV-1 after early treatment of acute infection. Nature 407523-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg, E. S., J. M. Billingsley, A. M. Caliendo, S. L. Boswell, P. E. Sax, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 1997. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science 2781447-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samson, M., F. Libert, B. J. Doranz, J. Rucker, C. Liesnard, C. M. Farber, S. Saragosti, C. Lapoumeroulie, J. Cognaux, C. Forceille, G. Muyldermans, C. Verhofstede, G. Burtonboy, M. Georges, T. Imai, S. Rana, Y. Yi, R. J. Smyth, R. G. Collman, R. W. Doms, G. Vassart, and M. Parmentier. 1996. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature 382722-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silvestri, G., A. Fedanov, S. Germon, N. Kozyr, W. J. Kaiser, D. A. Garber, H. McClure, M. B. Feinberg, and S. I. Staprans. 2005. Divergent host responses during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm infection of natural sooty mangabey and nonnatural rhesus macaque hosts. J. Virol. 794043-4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silvestri, G., D. L. Sodora, R. A. Koup, M. Paiardini, S. P. O'Neil, H. M. McClure, S. I. Staprans, and M. B. Feinberg. 2003. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity 18441-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staprans, S. I., P. J. Dailey, A. Rosenthal, C. Horton, R. M. Grant, N. Lerche, and M. B. Feinberg. 1999. Simian immunodeficiency virus disease course is predicted by the extent of virus replication during primary infection. J. Virol. 734829-4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veazey, R. S., M. DeMaria, L. V. Chalifoux, D. E. Shvetz, D. R. Pauley, H. L. Knight, M. Rosenzweig, R. P. Johnson, R. C. Desrosiers, and A. A. Lackner. 1998. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science 280427-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viollet, L., V. Monceaux, F. Petit, R. H. Fang, M. C. Cumont, B. Hurtrel, and J. Estaquier. 2006. Death of CD4+ T cells from lymph nodes during primary SIVmac251 infection predicts the rate of AIDS progression. J. Immunol. 1776685-6694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace, M., P. M. Waterman, J. L. Mitchen, M. Djavani, C. Brown, P. Trivedi, D. Horejsh, M. Dykhuizen, M. Kitabwalla, and C. D. Pauza. 1999. Lymphocyte activation during acute simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(89.6PD) infection in macaques. J. Virol. 7310236-10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson, A., J. Ranchalis, B. Travis, J. McClure, W. Sutton, P. R. Johnson, S. L. Hu, and N. L. Haigwood. 1997. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J. Virol. 71284-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]