Abstract

Gammaherpesvirus infection is associated with an increased incidence of lymphoproliferative disease in immunocompromised hosts. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (γHV68) infection of BALB β2-microglobulin-deficient (BALB β2m−/−) mice provides an animal model for analysis of the mechanisms responsible for the induction of a lymphoproliferative disease, atypical lymphoid hyperplasia (ALH), that is pathologically similar to posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Here we report that the γHV68 v-cyclin and v-bcl-2 genes are required for the efficient induction of γHV68-associated ALH in BALB β2m−/− mice, while the v-GPCR gene is dispensable for ALH induction. In contrast to these findings, deletion of the viral M1 gene enhanced ALH. Thus, γHV68 genes can either inhibit or enhance the induction of lymphoproliferative disease in immunocompromised mice.

Gammaherpesviruses are a family of ubiquitous pathogens that, after acute infection, establish latency in lymphoid and myeloid cells of the host. Gammaherpesvirus infection contributes to human illness largely via association of infection with various malignancies and lymphoproliferative disease (13, 29). This occurs particularly in immunocompromised hosts, indicating the importance of studies of gammaherpesvirus pathogenesis in the absence of a normal immune system.

In humans, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) is a lymphoid proliferation or lymphoma that develops as a consequence of immunosuppression in a transplant recipient. The majority of PTLD cases are Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-driven B-cell proliferations ranging from early lesions characterized by reactive plasmacytic hyperplasia to polymorphic lesions and finally to monomorphic PTLD (30, 34). Polymorphic PTLD is defined by destructive lesions composed of immunoblasts, plasma cells, and a range of small to intermediate-sized lymphoid cells that efface normal nodal architecture or form destructive extranodal masses (26, 34). The host and viral factors that play a role in PTLD development are not well understood. However, interferons may play an important role, since polymorphisms associated with reduced levels of interferon gamma production are more prevalent in patients with PTLD (37). Reduction of immunosuppression is an effective treatment for polymorphic PTLD (34), indicating that this lesion is the consequence of the lack of an appropriate immune response. EBV is detected in abnormal B cells of early-onset PTLD, and the growth program of viral gene expression is proposed to drive B-cell proliferation (34).

Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (γHV68) is related to human Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) and EBV and to simian herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) in genome organization (11, 40). γHV68 infection of BALB β2-microglobulin-deficient (β2m−/−) mice is associated with development of lymphoproliferative disease, occurring from 6 to 12 months after intraperitoneal inoculation (33). In these infected mice, atypical lymphoid hyperplasia (ALH) is characterized by abnormal expansion of plasmacytic CD138+ cells and precedes B-cell lymphomas (33). Importantly, ca. 35% of polymorphic PTLD cases in humans are also associated with uncontrolled expansion of CD138+ cells (6). Histologically, ALH lesions closely resemble polymorphic PTLD in humans, as evidenced by a destructive expansion of mature plasma cells and immunoblasts in a lymphoid-associated site. Although this infiltrate is most prominent in the spleen, extranodal sites, including the lungs and liver, are also commonly involved. ALH is also seen in mock-infected BALB β2m−/− mice, although with lower incidence and after a prolonged incubation period compared to virus-infected mice. The background level of ALH is higher in uninfected female mice than in uninfected male mice, making the use of male mice the most practical approach for studies of virus-induced ALH (33).

γHV68-infected cells are frequently detected in ALH lesions using in situ hybridization for highly expressed viral tRNAs (5, 31-33). However, not every lesion examined is positive for γHV68-vtRNA-expressing cells, and not every cell in ALH lesions is determined to be virus positive by this assay. Thus, the ALH lesion induced by wild-type γHV68 does not depend on the infection of every cell in the lesion. Similarly, polymorphic EBV-positive PTLD lesions represent heterogeneous collections of cells, including EBV-negative infiltrates of T cells and macrophages (30). In the present study we used the murine model of γHV68 infection of BALB β2m−/− male mice to identify viral genes, including v-bcl2 and v-cyclin as required for γHV68-induced ALH induction, and the γHV68 M1 gene as a suppressor of lymphoproliferative disease.

Definitions of splenic pathology.

To address the contribution of individual γHV68 genes to the development of lymphoproliferative disease, BALB β2m−/− mice were infected with wild-type γHV68 or γHV68 mutants as previously described, and the incidence of plasmacytosis and ALH was analyzed at 10 months postinfection (33). In order to reduce background levels of ALH, only male animals were used in the present study (33). We utilized the peritoneal route of inoculation as previously described (33). Small groups of BALB β2m−/− mice were inoculated over several weeks in independent experiments and sacrificed 10 months after infection, and then data from all independent experiments were pooled for analysis. We selected 10 months as a time point at which significant ALH is observed (33). Follicular hyperplasia, frequently observed in the spleens of γHV68-infected BALB-β2m−/− mice (33), was mostly coincident with plasmacytosis and was not scored as a separate entity in the present study. All mice were housed in a specific-pathogen-free barrier facility at Washington University in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines.

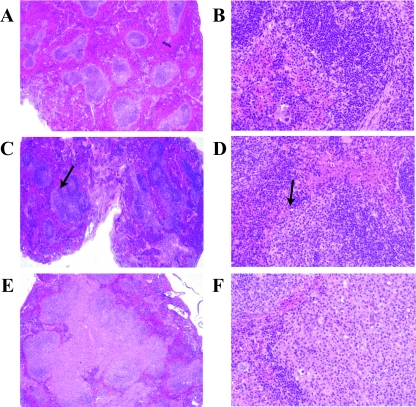

Spleens were evaluated in a blinded manner by a trained hematopathologist (F.K.). Normal spleens showed well-defined areas of white pulp composed of periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths and less distinct lymphoid follicles and marginal zones (Fig. 1A and B). Plasmacytosis was histologically defined as mildly expanded periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths containing clusters of cytologically unremarkable plasma cells with eccentrically located mature nuclei (Fig. 1C and D, arrows). Splenic plasmacytosis was histologically indistinguishable between γHV68-infected mice and the 2 mock-infected mice with plasmacytosis (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Splenic histology of BALB β2m−/− mice. (A and B) Normal; (C and D) mild follicular hyperplasia with plasmacytosis. Arrows indicate abnormal expansions of plasmacytoid cells. (E and F) ALH in a spleen from a γHV68-infected mouse. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of formaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Magnifications: A, C, and E, ×40; B, D, and F, ×400.

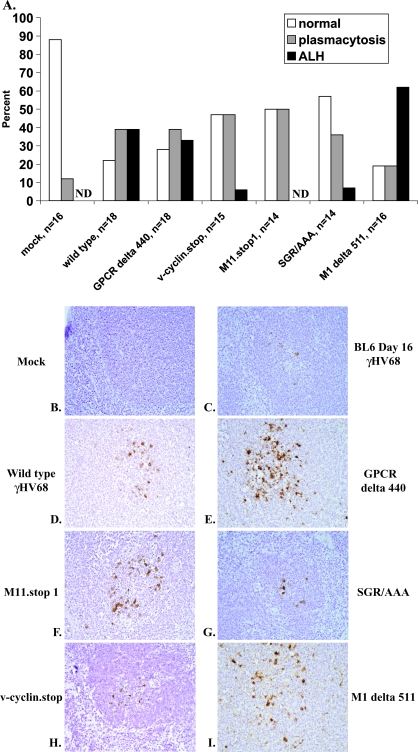

FIG. 2.

Viral cyclin, viral bcl-2, and M1 modulate γHV68-induced lymphoproliferative disease in BALB β2m−/− mice. (A) BALB β2m−/− mice were mock infected or infected with 107 PFU of wild-type γHV68 or the indicated viral mutants. At 10 months postinfection, mice were assigned to one of three splenic histopathology groups (normal, plasmacytosis, and ALH) based on splenic presentation. ND, none detected. (B to I) Spleens harvested at 10 months postinfection from BALB β2m−/− mice infected with the indicated viruses or from control animals (mock-infected or BL6 mouse at 16 days after γHV68 infection) were subjected to in situ hybridization using a probe against viral tRNAs. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, and images obtained at ×400 magnification. The spleens in panels D, E, and I displayed ALH.

Lesions defined as ALH were characterized by a significant expansion of the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath and marginal zone by a mixture of small lymphocytes and larger lymphoid cells with vesicular chromatin and frequent plasmacytoid appearance (Fig. 1E and F) (33). These areas were frequently confluent, causing partial disruption of the normal splenic architecture (Fig. 1E and F). No sheets of large cells or areas of necrosis or brisk mitotic rate were associated with these lesions.

Consistent with our previously published work, at 10 months postinfection, 87.5% of mock-infected BALB β2m−/− male mice had normal white pulp appearance (Fig. 2A), with only a small fraction developing splenic plasmacytosis (two mice, 12.5%). In contrast, only four animals (22%) of the γHV68-infected group had normal white pulp morphology. The splenic pathology of the remainder of the γHV68-infected group was equally distributed between plasmacytosis and ALH (39% each, Fig. 2A). The incidence of plasmacytosis (P = 0.04) and ALH (P = 0.0058) was significantly different between the mock-infected and γHV68-infected groups (Tables 1 and 2). These data confirmed our earlier study in showing γHV68 induction of lymphoproliferative disease and provided a comparison group for use to determine the effects of several γHV68 genes on the incidence and the severity of plasmacytosis and ALH induced by γHV68 infection.

TABLE 1.

Statistical analysis of differences in the incidence of ALHa

| Infection type |

P

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | v-cyclin.stop | M11.stop1 | SGR/AAA | GPCR delta 440 | M1 delta 511 | |

| Mock | 0.0058 | 0.3017 | 1 | 0.285 | 0.0122 | 0.0002 |

| Wild type | 0.0342 | 0.0094 | 0.0429 | 0.7322 | 0.17 | |

| v-cyclin.stop | 0.334 | 0.9604 | 0.0662 | 0.0014 | ||

| M11.stop1 | 0.3173 | 0.0183 | 0.0004 | |||

| SGR/AAA | 0.0801 | 0.002 | ||||

| Delta GPCR | 0.0938 | |||||

P values were determined by student t test analysis using PRISM (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA). Significant P values are indicated in boldface.

TABLE 2.

Statistical analysis of differences in the incidence of plasmacytosisa

| Infection type |

P

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | v-cyclin.stop | M11.stop1 | M11.SGR/AAA | GPCR delta 440 | M1 delta 511 | |

| Mock | 0.04 | 0.0394 | 0.0279 | 0.1403 | 0.0432 | 0.6318 |

| Wild type | 0.6576 | 0.5362 | 0.8563 | 1 | 0.205 | |

| v-cyclin.stop | 0.86 | 0.5565 | 0.6576 | 0.102 | ||

| M11.stop1 | 0.45 | 0.5362 | 0.0749 | |||

| Delta GPCR | 0.205 | |||||

P values were determined by Student t test analysis using PRISM (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA). Significant P values are indicated in boldface.

Importance of the v-bcl-2 gene in induction of lymphoproliferative disease.

The γHV68 M11 (v-bcl-2) protein is a structural homolog of cellular Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL (15, 21). The v-bcl-2 BH1 domain is required to bind BH3 peptides derived from Bax and Bak and inhibit Bax-mediated cell death in yeast (21). Recent studies also show that γHV68 v-bcl-2 can bind to beclin 1, an important regulator of autophagy, a cellular pathway that has tumor suppressor functions (20, 27, 28, 45). v-bcl-2 is dispensable for γHV68 replication in fibroblasts in vitro; however, v-bcl-2 deficiency attenuates ex vivo γHV68 reactivation and persistent replication in immunodeficient mice. In addition, cellular bcl-2 family members function in diverse areas such as cell cycle, intermediary metabolism, regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ flux, and DNA mismatch repair (17, 18, 20, 27, 43, 44). The precise mechanisms responsible for the role of v-bcl-2 in viral infection have not been defined, although the BH1 domain amino acids SGR are required for most in vivo functions of v-bcl-2 during infection (21).

To determine the role of γHV68 v-bcl-2 in ALH development, mutants deficient in the expression of v-bcl-2 (M11.Stop1) (15) or bearing point mutations in the SGR amino acids in the v-bcl-2 BH1 domain (SGR/AAA) (21) were analyzed for the ability to induce ALH in BALB β2m−/− male mice. Splenic histopathology in M11.stop1-infected BALB β2m−/− mice was equally distributed between normal and plasmacytosis (Fig. 2A) but lacked ALH. The incidence of plasmacytosis and ALH in the SGR/AAA-infected group was similar to that observed in M11.stop1-infected BALB β2m−/− mice (Fig. 2A and Tables 1 and 2), providing an independent confirmation that v-bcl-2 is important for the induction of ALH and indicating the importance of the BH1 domain in induction of lymphoproliferative disease.

v-bcl-2 deficiency decreases γHV68 reactivation ex vivo and attenuates persistent replication (10, 15). Reactivation is thought to be important to sustain the reservoir of γHV68 latently infected cells in immunocompromised mice (14). We therefore performed in situ hybridization using a vtRNA probe to determine whether the v-bcl-2 γHV68 mutant viruses persisted over the 10 months of infection. Indeed, we were able to detect vtRNA-positive cells in M11.stop1- and SGR/AAA-infected spleens at 10 months postinfection, suggesting that the decrease in ALH incidence was not due to the clearance of the M11 mutant viruses (Fig. 2F and G).

Importance of the v-cyclin gene in the induction of lymphoproliferative disease.

The γHV68 v-cyclin gene encodes a cyclin homolog with an expanded repertoire of substrates, phosphorylation of which depends on the intact cyclin box responsible for interaction with cellular cyclin-dependent kinases (cdk's) (36). γHV68 v-cyclin expression in T cells of transgenic mice leads to defective T-cell maturation and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphomas (38). Interestingly, the HVS v-cyclin is not required for the induction of T-cell lymphomas in New World primates infected with one million infectious units of HVS (12). Like its HVS homolog, the γHV68 v-cyclin is dispensable for replication of γHV68 in vitro (12, 39). However, the γHV68 v-cyclin is important for efficient in vivo replication after intranasal inoculation and for ex vivo reactivation of γHV68 (35, 39). The role of v-cyclin in γHV68 ex vivo reactivation is not entirely dependent on intact cyclin box, suggesting alternative cdk-independent v-cyclin functions (35), such as transcriptional regulation similar to that attributed to both cellular and KSHV K-cyclin (19, 22).

To determine whether the γHV68 v-cyclin gene is important for ALH induction, BALB β2m−/− males were infected with a v-cyclin.stop γHV68 mutant (39), and the incidence of ALH was analyzed at 10 months postinfection. Upon infection with v-cyclin.stop γHV68 mutant virus, BALB β2m−/− mice displayed either normal splenic white pulp or plasmacytosis (47% of animals in this group for each condition, Fig. 2A). Only one spleen harvested from the γHV68 v-cyclin.stop-infected BALB β2m−/− mouse had features of ALH (P = 0.0342 versus wild-type infection, Table 1), and thus the v-cyclin of γHV68 is essential for the efficient induction of lymphoproliferative disease.

To determine whether the lack of induction of ALH by v-cyclin mutant γHV68 was due to the clearance of the mutant virus, spleens from v-cyclin.stop-infected BALB β2m−/− mice were analyzed for viral presence by in situ hybridization using a vtRNA probe. vtRNA-positive cells were readily detected at 10 months postinfection in the spleens of BALB β2m−/− mice infected with the v-cyclin.stop mutant (Fig. 2H), suggesting that the lack of efficient ALH induction by v-cyclin mutant γHV68 was not due to its clearance.

No role for the viral G protein-coupled receptor (v-GPCR) in the induction of lymphoproliferative disease.

v-GPCRs encoded by gammaherpesviruses, including KSHV and HVS, share sequence homology and functionally resemble cellular cytokine receptors (1-3, 7, 25). v-GPCR proteins have been implicated in oncogenesis. Transgenic expression of KSHV v-GPCR induces angioproliferative lesions within multiple organs and contributes to immortalization of primary cells in vitro (4, 16, 23, 42). γHV68 v-GPCR is a latency-associated protein that is important for ex vivo virus reactivation (24).

To determine the role of the γHV68 v-GPCR gene in ALH induction, the incidence of ALH was analyzed in BALB β2m−/− mice infected with the GPCR delta 440 γHV68 mutant (24). The incidence of ALH and plasmacytosis in GPCR delta 440-infected mice was indistinguishable from that observed in mice infected with wild-type γHV68 (Fig. 2A and Tables 1 and 2). Thus, the γHV68 v-GPCR gene was not required for induction of ALH in BALB β2m−/− mice.

Importance of the M1 gene in limiting the severity of lymphoproliferative disease.

While the v-bcl-2 and v-cyclin genes were important for ALH induction, another viral gene, M1, had a role in decreasing the severity of ALH. M1 is a latency-associated γHV68 gene with no significant homology to known viral or cellular proteins. M1 is dispensable for γHV68 replication in vitro or during acute infection; however, in the absence of M1 γHV68 exhibits increased efficiency of ex vivo reactivation from latency (8).

When the incidence of ALH was analyzed in BALB β2m−/− mice infected with an M1 delta 511 γHV68 mutant, ALH was found in a majority of mice at 10 months postinfection (66%; Fig. 2A). However, the incidence of ALH was not increased in M1 delta 511-infected mice compared to mice infected with wild-type γHV68 (P = 0.17). In contrast, splenic pathology in M1 mutant-infected mice was strikingly more severe than that observed in wild-type γHV68-infected mice. To quantify this observation, pathology slides were graded in a blinded fashion, and the data were analyzed by a log-rank test. ALH induced by M1 delta 511 mutant was significantly more severe than that induced by wild-type γHV68 (P = 0.006). Similar to ALH induced by wild-type γHV68, vtRNA-positive cells were associated with ALH lesions found in M1 delta 511-infected mice as determined by in situ hybridization (Fig. 2I). Thus, the M1 gene played a role in suppression of the severity of γHV68-induced lymphoproliferative disease but did not play a role in controlling the incidence of lymphoproliferative disease under these experimental conditions.

γHV68 biology and lymphoproliferative disease.

This is the first study identifying γHV68 genes that influence, positively or negatively, the incidence and severity of gammaherpesvirus-induced lymphoproliferative disease. The mechanism of the lymphoproliferative disease induction by γHV68 is not clear (33), making it difficult to propose a unifying mechanism by which v-bcl-2, v-cyclin, and M1 genes, but not the v-GPCR gene, of γHV68 modulate ALH development. In fact, the most striking finding here is that there is no clear correlation between the reported reactivation phenotypes of the mutants tested here and their capacity to induce ALH (8, 10, 15, 24, 35, 39). For example, v-bcl-2, v-cyclin, and v-GPCR genes all have been reported to modulate the efficiency of reactivation from latency in explant cultures but differ, at least under the experimental conditions reported here, in their capacity to induce ALH.

It is interesting to compare the role of γHV68 genes in ALH induction to their roles in the induction of arteritis in chronically infected mice lacking the gamma interferon receptor (8, 9, 15, 41). Arteritis is the other major pathology, in addition to ALH, reported in immunocompromised mice chronically infected with γHV68. As for ALH, the v-cyclin and v-bcl-2 genes are required for efficient induction of arteritis (15). The role of the v-GPCR in arteritis has not been reported. Interestingly, as for ALH, the role of the M1 gene in vasculitis contrasts with the role of the v-cyclin and v-bcl-2 genes. The absence of the M1 gene has no effect on the incidence or severity of γHV68-induced arteritis (8). Thus, while the effects of the viral genes analyzed here on ex vivo reactivation do not necessarily predict the effects on ALH induction, it is clear that there are viral genes that play critical opposing roles in chronic pathologies induced by γHV68 infection.

Acknowledgments

H.W.V. is supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA 74730. V.L.T. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma society fellow. D.W.W. is supported by an Abbott Scholar Award.

We thank Darren Kreamalmayer for his truly outstanding expertise in the breeding of animals.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahuja, S. K., and P. M. Murphy. 1993. Molecular piracy of mammalian interleukin-8 receptor type B by herpesvirus saimiri. J. Biol. Chem. 26820691-20694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvanitakis, L., E. Geras-Raaka, A. Varma, M. C. Gershengorn, and E. Cesarman. 1997. Human herpesvirus KSHV encodes a constitutively active G-protein-coupled receptor linked to cell proliferation. Nature 385347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bais, C., B. Santomasso, O. Coso, L. Arvanitakis, E. G. Raaka, J. S. Gutkind, A. S. Asch, E. Cesarman, M. C. Gershengorn, and E. A. Mesri. 1998. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature 39186-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bais, C., A. Van Geelen, P. Eroles, A. Mutlu, C. Chiozzini, S. Dias, R. L. Silverstein, S. Rafii, and E. A. Mesri. 2003. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor immortalizes human endothelial cells by activation of the VEGF receptor-2/KDR. Cancer Cell 3131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowden, R. J., J. P. Simas, A. J. Davis, and S. Efstathiou. 1997. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 encodes tRNA-like sequences which are expressed during latency. J. Gen. Virol. 781675-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capello, D., D. Rossi, and G. Gaidano. 2005. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders: molecular basis of disease histogenesis and pathogenesis. Hematol. Oncol. 2361-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cesarman, E., R. G. Nador, F. Bai, R. A. Bohenzky, J. J. Russo, P. S. Moore, Y. Chang, and D. M. Knowles. 1996. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus contains G protein-coupled receptor and cyclin D homologs which are expressed in Kaposi's sarcoma and malignant lymphoma. J. Virol. 708218-8223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clambey, E. T., H. W. Virgin, and S. H. Speck. 2000. Disruption of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 M1 open reading frame leads to enhanced reactivation from latency. J. Virol. 741973-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dal Canto, A. J., H. W. Virgin, and S. H. Speck. 2000. Ongoing viral replication is required for gammaherpesvirus 68-induced vascular damage. J. Virol. 7411304-11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lima, B. D., J. S. May, S. Marques, J. P. Simas, and P. G. Stevenson. 2004. Murine gammaherpesviruis 68 bcl-2 homologue contributes to latency establishment in vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 8631-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efstathiou, S., Y. M. Ho, S. Hall, C. J. Styles, S. D. Scott, and U. A. Gompels. 1990. Murine herpesvirus 68 is genetically related to the gammaherpesviruses Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus saimiri. J. Gen. Virol. 711365-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensser, A., D. Glykofrydes, H. Niphuis, E. M. Kuhn, B. Rosenwirth, J. L. Heeney, G. Niedobitek, I. Muller-Fleckenstein, and B. Fleckenstein. 2001. Independence of herpesvirus-induced T-cell lymphoma from viral cyclin D homologue. J. Exp. Med. 193637-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganem, D. 2007. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, p. 2847-2888. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA.

- 14.Gangappa, S., S. B. Kapadia, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin. 2002. Antibody to a lytic cycle viral protein decreases gammaherpesvirus latency in B-cell-deficient mice. J. Virol. 7611460-11468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gangappa, S., L. F. Van Dyk, T. J. Jewett, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin. 2002. Identification of the in vivo role of a viral bcl-2. J. Exp. Med. 195931-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo, H. G., M. Sadowska, W. Reid, E. Tschachler, G. Hayward, and M. Reitz. 2003. Kaposi's sarcoma-like tumors in a human herpesvirus 8 ORF74 transgenic mouse. J. Virol. 772631-2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou, Y. Z., F. Q. Gao, Q. H. Wang, J. F. Zhao, T. Flagg, Y. D. Zhang, and X. M. Deng. 2007. Bcl2 impedes DNA mismatch repair by directly regulating the hMSH2-hMSH6 heterodimeric complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2829279-9287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyer-Hansen, M., L. Bastholm, P. Szyniarowski, M. Campanella, G. Szabadkai, T. Farkas, K. Bianchi, N. Fehrenbacher, F. Elling, R. Rizzuto, I. S. Mathiasen, and M. Jaattela. 2007. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol. Cell 25193-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laman, H., D. Coverley, T. Krude, R. Laskey, and N. Jones. 2001. Viral cyclin-cyclin-dependent kinase 6 complexes initiate nuclear DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21624-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang, C., P. Feng, B. Ku, I. Dotan, D. Canaani, B. H. Oh, and J. U. Jung. 2006. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat. Cell Biol. 8688-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loh, J., Q. Huang, A. M. Petros, D. Nettesheim, L. F. Van Dyk, L. Labrada, S. H. Speck, B. Levine, E. T. Olejniczak, and H. W. Virgin. 2005. A surface groove essential for viral bcl-2 function during chronic infection in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 1e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundquist, A., B. Barre, F. Bienvenu, J. Hermann, S. Avril, and O. Coqueret. 2003. Kaposi sarcoma-associated viral cyclin K overrides cell growth inhibition mediated by oncostatin M through STAT3 inhibition. Blood 1014070-4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montaner, S., A. Sodhi, A. Molinolo, T. H. Bugge, E. T. Sawai, Y. He, Y. Li, P. E. Ray, and J. S. Gutkind. 2003. Endothelial infection with KSHV genes in vivo reveals that vGPCR initiates Kaposi's sarcomagenesis and can promote the tumorigenic potential of viral latent genes. Cancer Cell 323-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moorman, N. J., H. W. Virgin, and S. H. Speck. 2003. Disruption of the gene encoding the gamma HV68 v-GPCR leads to decreased efficiency of reactivation from latency. Virology 307179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy, P. M. 2001. Viral exploitation and subversion of the immune system through chemokine mimicry. Nat. Immunol. 2116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muti, G., V. Mancini, E. Ravelli, and E. Morra. 2005. Significance of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) load and interleukin-10 in post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Leukemia Lymphoma 461397-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pattingre, S., A. Tassa, X. P. Qu, R. Garuti, X. H. Liang, N. Mizushima, M. Packer, M. D. Schneider, and B. Levine. 2005. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122927-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qu, X., J. Yu, G. Bhagat, N. Furuya, H. Hibshoosh, A. Troxel, J. Rosen, E. L. Eskelinen, N. Mizushima, Y. Ohsumi, G. Cattoretti, and B. Levine. 2003. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J. Clin. Investig. 1121809-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickinson, A., and E. Kieff. 2007. Epstein-Barr virus, p. 2655-2700. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA.

- 30.Shroff, R., and L. Rees. 2004. The post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder: a literature review. Pediatr. Nephrol. 19369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simas, J. P., D. Swann, R. Bowden, and S. Efstathiou. 1999. Analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus-68 transcription during lytic and latent infection. J. Gen. Virol. 8075-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart, J. P., E. J. Usherwood, A. Ross, H. Dyson, and T. Nash. 1998. Lung epithelial cells are a major site of murine gammaherpesvirus persistence. J. Exp. Med. 1871941-1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarakanova, V. L., F. S. Suarez, S. A. Tibbetts, M. Jacoby, K. E. Weck, J. H. Hess, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin. 2005. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection induces lymphoproliferative disease and lymphoma in BALB β2 microglobulin-deficient mice. J. Virol. 7914668-14679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor, A., R. Marcus, and J. A. Bradley. 2005. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) after solid organ transplantation. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 56155-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Upton, J. W., and S. H. Speck. 2006. Evidence for CDK-dependent and CDK-independent functions of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 v-cyclin. J. Virol. 8011946-11959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Upton, J. W., L. F. Van Dyk, and S. H. Speck. 2005. Characterization of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 v-cyclin interactions with cellular cdks. Virology 341271-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.VanBuskirk, A. M., V. Malik, D. Xia, and R. P. Pelletier. 2001. A gene polymorphism associated with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Transpl. Proc. 331834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Dyk, L. F., J. L. Hess, J. D. Katz, M. Jacoby, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin. 1999. The murine gammaherpesvirus 68 v-cyclin is an oncogene that promotes cell cycle progression in primary lymphocytes. J. Virol. 735110-5122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Dyk, L. F., H. W. Virgin, and S. H. Speck. 2000. The murine gammaherpesvirus 68 v-cyclin is a critical regulator of reactivation from latency. J. Virol. 747451-7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Virgin, H. W., P. Latreille, P. Wamsley, K. Hallsworth, K. E. Weck, A. J. Dal Canto, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 715894-5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weck, K. E., A. J. Dal Canto, J. D. Gould, A. K. O'Guin, K. A. Roth, J. E. Saffitz, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin. 1997. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 causes severe large vessel arteritis in mice lacking interferon-gamma responsiveness: a new model for virus induced vascular disease. Nat. Med. 31346-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang, T. Y., S. C. Chen, M. W. Leach, D. Manfra, B. Homey, M. Wiekowski, L. Sullivan, C. H. Jenh, S. K. Narula, S. W. Chensue, and S. A. Lira. 2000. Transgenic expression of the chemokine receptor encoded by human herpesvirus 8 induces an angioproliferative disease resembling Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Exp. Med. 191445-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yorimitsu, T., U. Nair, Z. Yang, and D. J. Klionsky. 2006. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 28130299-30304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Youn, C. K., H. J. Cho, S. H. Kim, H. B. Kim, M. H. Kim, I. Y. Chang, J. S. Lee, M. H. Chung, K. S. Hahm, and H. J. You. 2005. Bcl-2 expression suppresses mismatch repair activity through inhibition of E2F transcriptional activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 7137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yue, Z., S. Jin, C. Yang, A. J. Levine, and N. Heintz. 2003. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10015077-15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]