Abstract

A series of [(aryl)arylsufanylmethyl]pyridines (AASMP) have been synthesized. These compounds inhibited hemozoin formation, formed complexes (KD = 12 to 20 μM) with free heme (ferriprotoporphyrin IX) at a pH close to the pH of the parasite food vacuole, and exhibited antimalarial activity in vitro. The inhibition of hemozoin formation may develop oxidative stress in Plasmodium falciparum due to the accumulation of free heme. Interestingly, AASMP developed oxidative stress in the parasite, as evident from the decreased level of glutathione and increased formation of lipid peroxide, H2O2, and hydroxyl radical (·OH) in P. falciparum. AASMP also caused mitochondrial dysfunction by decreasing mitochondrial potential (ΔΨm) in malaria parasite, as measured by both flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. Furthermore, the generation of ·OH may be mainly responsible for the antimalarial effect of AASMP since ·OH scavengers such as mannitol, as well as spin trap α-phenyl-n-tertbutylnitrone, significantly protected P. falciparum from AASMP-mediated growth inhibition. Cytotoxicity testing of the active compounds showed selective activity against malaria parasite with selectivity indices greater than 100. AASMP also exhibited profound antimalarial activity in vivo against chloroquine resistant P. yoelii. Thus, AASMP represents a novel class of antimalarial.

Malaria affects 40% of global population and accounts annually for 300 to 500 million clinical cases with 1.5 to 2.7 million deaths (50, 72). The burden of malaria is increasing because of drug resistance, and there is an urgent need for new antimalarial drugs (25, 71). Intra-erythrocytic stages of malaria parasites consume and degrade huge quantities of hemoglobin in the food vacuole and release large quantities of redox active free heme as a by-product (49). Free heme (ferriprotoporphyrin IX) is very toxic (29, 30), and parasites detoxify free heme by forming hemozoin, mainly through the biocrystallization or biomineralization process (18, 19, 41). Molecules that inhibit parasite growth through binding to heme are potential antimalarials, and the inhibition of hemozoin formation is considered a valid target for developing new antimalarials (16, 17). Again, the inhibition of hemozoin formation may develop oxidative stress due to the accumulation of free heme, which can generate highly reactive hydroxyl radical (·OH), and the malaria parasite is susceptible to oxidative stress (29, 30). Therefore, the enhancement of oxidative stress to the parasite by any means is a promising strategy in developing new antimalarial agents.

Triarylmethanes represent an important class of medicinally important molecules (38) and are known to possess a wide variety of biological activities such as antitubercular (42-45, 54), anti-implantation (58), and antiproliferative (1) activities and activity against breast cancer (55). The potent antimycotic drug clotrimazole, a member of the triarylmethanes, inhibits the in vitro parasite growth of different strains of chloroquine-sensitive and -resistant Plasmodium falciparum (51, 61, 65). Very recently, antimalarial agents based on the clotrimazole scaffold have been synthesized (23). Again, trisubstituted methanes (TRSMs) containing sulfide, sulfoxide, or sulfone spacers have also been reported to show various biological activities. A small set of 9-(lupinylthio)xanthenes, 9-(lupinylthio)thioxanthenes, and a-(lupinylthio)diphenylmethanes was found to exhibit diverse biological activities (39). Arylsulfanyl and arylsulfonyl moities are integral parts of many antimalarial agents. For example, the antimalarial activity of several arylacridinyl sulfones has been reported recently (52). Furoxan derivatives bearing a sulfone moiety were reported to have antimalarial activity (22). A series of imidazole-dioxolane compounds bind to the heme and showed promising anti-Plasmodium activity (68). These results prompted us to synthesize and evaluate a new series of TRSMs for antimalarial efficacy. Here we report the antimalarial activity of a series of [(aryl)arylsufanylmethyl]pyridines (AASMPs) that represents a new class of TRSMs. Our work focused on the evaluation of the antimalarial activity of these compounds, including the mechanistic details on the effect of heme interaction, hemozoin formation, and in vitro and in vivo antimalarial effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Hemin, RPMI 1640, saponin, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), chloroquine, glutathione (GSH), thiobarbituric acid, trichloroacetic acid, α-phenyl-n-tert-butyl-nitrone (PBN), dichlorofluorescein diacetate, fetal calf serum, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), penicillin, streptomycin, and tetraethoxypropane were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). AlbuMax II was procured from Life Technologies, and Giemsa stain was purchased from Qualigens Fine Chemicals, India. [3H]hypoxanthine was purchased from Amersham Biosciences. All other chemicals were of analytical-grade purity.

Chemical synthesis.

Chemical synthesis, as well as the characterization of all AASMP was provided separately (see additional information in the supplemental material).

Parasite culture (in vitro and in vivo).

P. falciparum (clone NF54) was grown as described by Trager and Jensen (63) at a hematocrit level of 5% in complete RPMI medium (CRPMI; RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 50 μg of gentamicin ml−1, 370 μM hypoxanthine, and 0.5% [wt/vol] AlbuMaxII) in tissue-culture flasks (25 and 75 cm2) with loose screw caps. Used medium was changed with fresh medium once in 24 h, and the culture was routinely monitored through Giemsa-staining of thin smears. The growth of multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. yoelii in vivo was maintained in the Swiss mouse model as described previously (56).

Isolation of parasite from infected erythrocytes and preparation of parasite lysate.

The parasite (P. falciparum and P. yoelii) was isolated as described previously (10). Briefly, erythrocytes with ∼10% parasitemia (P. falciparum) or 50% parasitemia (P. yoelii) were centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min, washed, and resuspended in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 5.3 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4). An equal volume of 0.5% saponin in PBS (final concentration, 0.25%) was added to the erythrocyte suspension and kept on ice for 15 min. It was centrifuged at 1,300 × g for 5 min to get a parasite pellet; finally, the pellet was washed with PBS and either used immediately or kept at −80°C. The isolated parasite was lysed in PBS by mild sonication (30-s pulse, bath-type sonicator) at 4°C, and the whole lysate was then stored at −20°C for future use. The protein content of the parasite lysate was estimated as described previously (33).

Hemozoin (β-hematin) formation.

Hemozoin formation was assayed as described earlier (46, 59, 64). In brief, the assay mixture contained in a final volume of 1 ml: 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.2), 100 μM hemin, parasite lysate (20 μl), and different concentrations of AASMPs. The reaction was initiated by the addition of hemin, followed by incubation for 12 h at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The pellet was washed twice with 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.8) containing 2.5% SDS and finally with 100 mM bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.2). The insoluble pellet (hemozoin) was solubilized in 50 μl of 2 N NaOH and diluted further to 1 ml with 2.5% SDS. The absorbance of the solution was recorded at 400 nm, and an extinction coefficient of 91 mM−1 cm−1 (46) was used to quantitate the heme converted to hemozoin. To see the effect of AASMP on hemozoin formation in P. falciparum, the amount of hemozoin formed in the presence or absence of AASMP was measured as described earlier (12). In brief, P. falciparum culture (5% parasitemia) was synchronized with d-sorbitol (5%) to achieve ring stage (31). The ring-synchronized culture was treated with different concentrations of AASMP and incubated further for 48 h. The culture was harvested, and parasite was isolated from infected red blood cells (RBC) by saponin treatment (0.5%, 10 min). The parasites were washed three times with PBS, and parasite lysate was prepared after mild sonication. Parasite lysate was washed three times with 2% SDS, and the resulting pellet was suspended in a solution of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5% SDS, and 1 mM CaCl2 containing 2 μg of proteinase K per ml and then incubated at 37°C overnight. The pellet was then washed three times in 2% SDS and incubated in 6 M urea for 3 h at room temperature on a shaker. After incubation, it was centrifuged (4,000 × g for 10 min) at room temperature and again washed three times with 2% SDS. Finally, the hemozoin pellet was dissolved in 20 mM NaOH containing 2% SDS, and the optical density of solution was measured at 400 nm to quantitate the hemozoin.

Calculation of logP and pKa of the AASMPs.

The logP and pKa values of the AASMPs were calculated by using the property prediction software CSPredict (ChemSilico LLC, Tewksbury, MA) (66, 69, 70).

Binding of AASMP with heme (ferriprotoporphyrin IX).

Optical spectra were recorded in a total volume of 1 ml containing heme in 100 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.2) in a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 15 UV/VIS spectrophotometer at 25 ± 1°C with quartz cells with a 1-cm light path. Binding of AASMPs to heme was monitored at different concentrations (5 to 40 μM). Different concentrations of AASMPs were added successively. The Soret spectrum was recorded immediately after each addition of AASMP. Interaction of AASMPs with heme was also measured by optical difference spectroscopy as described earlier (65). To measure the difference spectra of heme-AASMP versus the heme, both the reference and sample cuvettes were filled with 1 ml of heme solution (1 μM) to provide the baseline trace. This was followed by the addition of a small volume (usually 5 to 20 μl) of AASMPs to the sample cuvette with the concomitant addition of the same volume of DMSO to the reference cuvette (AASMP was dissolved in DMSO). The contents were mixed well before the spectrum was recorded. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for complex formation was calculated from the following expression as described by Schejter et al. (53): 1/ΔA = (KD/ΔAα) 1/S + 1/ΔAα, where KD is the dissociation constant of the heme-AASMP complex, S is the concentration of AASMP, ΔA is the observed absorption change at a particular wavelength, and ΔAα is the absorption change at a saturating concentration of the ligand (AASMP).

Assay of antimalarial activity by monitoring [3H]hypoxanthine uptake.

Inhibition of P. falciparum growth was studied by monitoring [3H]hypoxanthine uptake as described earlier (15). P. falciparum (NF-54 strain) was cultured in vitro as described earlier (63). Synchronization of the parasites to uniform ring stages was achieved by using 5% aqueous d-sorbitol as described earlier (31). In brief, P. falciparum culture was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min to pellet the cells. The supernatant media was discarded, and packed cells were suspended in a five times volume of 5% d-sorbitol and allowed to stand for 15 to 20 min at 37°C. The cells were washed twice with RPMI medium (without AlbuMax II) to remove sorbitol and cell debris. The pellet was suspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium to a final hematocrit of 2 to 3%. Synchronization of the culture was confirmed by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thin-smear slides. To see the effect of AASMP, the ring-synchronized P. falciparum (parasitemia, 0.5 to 1%) was cultured in multiwell plates (200 μl/well) in the presence or absence of different concentrations of AASMPs. Chloroquine was used as a positive control. After 48 h [3H]hypoxanthine (0.7 μCi/well) was added in each well and further cultured for 48 h to monitor parasite viability by measuring the incorporation of [3H]hypoxanthine in parasite nucleic acids. P. falciparum culture was harvested and washed twice in PBS. These parasite pellets were dissolved in 100 μl of 3 N NaOH by keeping the mixture at 37°C for 6 h. After incubation, it was placed in scintillation fluid and after 12 h, the [3H]hypoxanthine uptake was measured in a β-counter.

Measurement of heme content.

The heme content in control and AASMP-treated P. falciprum was measured as described earlier (36). In brief, P. falciparum was cultured in the presence or absence of various concentrations of AASMP for 48 h. The culture was then centrifuged to pellet the cells, and the cell pellet was washed in PBS. Concentrated formic acid (1 ml) was then added to solubilize each pellet, and the heme concentration of the formic acid solution was determined in a Shimadzu UV/VIS1700 spectrophotometer at 398 nm (extinction coefficient = 1.56 × 105 M−1 cm−1). The heme content was expressed as nmol/mg of cell protein.

Measurement of reduced GSH.

P. falciparum (4% parasitemia) was cultured in the presence or absence of different concentrations of AASMPs. After 48 h of treatment, the culture was washed twice with PBS, and the parasite was isolated. The GSH contents from control and AASMP-treated parasites were determined as described previously (5, 9, 26). Isolated parasite was sonicated in 200 μl of 20 mM ice-cold EDTA in a VCX 600 sonicator (by using a 9 s on/10 s off cycle for a period of 60 s) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min to get clear lysate. The lysate (200 μl) was mixed with an equal volume of 10% trichloroacetic acid, and protein precipitate was removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was added to an equal volume of 0.8 M Tris-HCl (pH 9) containing 20 mM 5-5′-dithionitrobenzoic acid to yield the yellow chromophore of thionitrobenzoic acid, which was measured at 412 nm. GSH was used as a standard.

Measurement of lipid peroxide as an index of oxidative damage.

P. falciparum culture (4% parasitemia, ring synchronized) was incubated with different concentrations of AASMPs for 48 h. After incubation, the parasite was isolated and mixed with PBS (500 μl) to prepare parasite lysate as described above, and the lipid peroxidation product from these lysates was measured as described earlier (5, 8, 26). In brief, parasite lysate (500 μl) was treated with 1 ml of trichloroacetic acid-thiobarbituric acid mixture in 1 N HCl, followed by incubation for 15 min at 100°C. After incubation, the sample was cooled and centrifuged (4,000 rpm for 10 min). Supernatant was then collected, and the optical density was measured at 535 nm. The formation of lipid peroxide in parasite membrane was expressed as nmol/mg of lysate protein. Tetraethoxypropane was used as a standard.

Fluorometric measurement of intra-parasitic H2O2.

P. falciparum (4% parasitemia) was cultured in the presence or absence of different concentrations of AASMPs for a period of 48 h. The culture was then further incubated for 30 min in complete RPMI medium containing 10 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate. The culture was then washed twice with PBS, and the parasite was isolated from control and treated groups. Isolated parasites were lysed by mild sonication (5-s pulse, bath-type sonicator) at 4°C. H2O2 was measured in control or AASMP-treated parasites by measuring the fluorescent dichlorofluorescein formed due to the oxidation of nonfluorescent probe dichlorofluorescein diacetate by H2O2 (37). Fluorescence intensities were recorded from the lysate in a Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences Lambda L.S 50B spectrofluorometer with a 5-mm path-length quartz cell in a total volume of 1 ml at wavelengths of 502 and 523 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. The H2O2 content was measured and is expressed as the fluorescence intensity/mg of parasite lysate protein.

Measurement of hydroxyl radical (·OH) generation.

·OH generated in the P. falciparum after AASMP treatment at different concentrations was measured by using DMSO as an ·OH scavenger (3, 5). In brief, P. falciparum culture (200 μl) (2% parasitemia, ring plus early trophozoite stage) was grown in a multiwell plate in the presence or absence of different concentrations of AASMPs containing 20 μl of 25% DMSO for 48 h. DMSO (20 μl) was added in each time, along with the stipulated concentrations of AASMP when the medium was changed (once in 24 h). A negative control (parasite only) was made without DMSO and AASMP. After 48 h, the culture was centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min, washed, and resuspended in cold PBS. The parasite was isolated as described above, and the isolated parasite was lysed in triple-distilled water and processed for the extraction of methanesulfinic acid formed by the reaction of ·OH with DMSO. Methanesulfinic acid formed was allowed to react with Fast Blue BB salt, and the intensity of the resulting yellow chromophore was measured at 425 nm by using benzenesulfinic acid as a standard. ·OH formed was expressed as nmol/mg of lysate protein.

Measurement of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Δψm).

For the measurement of Δψm, trophozoite-rich infected red cell were isolated (35) and used to monitor JC1 uptake. In brief, blood from P. yoelii-infected mice was collected in acid citrate dextrose (0.0347 M citric acid, 0.0748 M sodium citrate, 0.1359 M dextrose) at ca. 50% parasitemia. Infected blood was passed through CF-11 cellulose (Whatman) to remove the white blood cells (24). The collected RBC were washed and trophozoite-rich-infected RBC was isolated as described previously (35). Isolated trophozoite-rich infected red cells at a concentration of 5 × 106/ml in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum were incubated in the presence or absence of AASMP (4e, 40 μM) for 1 h at room temperature (30°C). For a positive control, the same numbers of trophozoites were incubated with antimycin A. The infected red cells were then washed (three times) in PBS by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min to remove the excess AASMP or antimycin A, and the cell pellets were suspended in 1 ml of CRPMI. JC1 (153 nM) was then added to each cell suspension, followed by incubation for 10 min in dark at 25°C. At the end of the incubation, the fluorescence of each sample was recorded in a Flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson FL-2; excitation, 480 nm; emission, 590 nm) (13). The JC1 uptake (J-aggregate formation) was also measured by fluorescence microscopy using a JC1-treated cell suspension. In brief, a JC1-treated cell suspension was washed (three times) in CRPMI by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min, and the resulting infected red cell pellet was suspended in 100 μl of CRPMI. A total of 20 μl from this cell suspension was used to analyze the formation of J-aggregate (emission, 590 nm; TX2 green filter) as a measure of the mitochondrial uptake and monomer (emission, 530 nm; I3 blue filter) quickly under a ×100 oil immersion lens in a Leica DM LB 2 fluorescence microscope.

In vitro cytotoxicity.

The hemolytic activity of AASMPs was evaluated according to the method described earlier (2) with slight modifications. Human B+ RBC were incubated in 96-well plate either in the presence of DMSO (control) or in the presence of various concentrations of AASMP for 24 h in 200 μl of CRPMI at a 5% hematocrit level. RBC were washed three times in CRPMI to remove excess AASMPs and inoculated with 20 μl of P. falciparum parasitized RBC (human B+) growing at a 5% hematocrit level and 4 to 5% parasitemia (mostly trophozoites). Parasites were allowed to complete one intra-erythrocytic cycle, followed by the addition of 0.7 μCi of [3H]hypoxanthine per well, and the culture was further incubated for 24 h under optimum conditions. Upon completion of the incubation, cells were harvested on Whatman GF/C glass filters by using a cell harvester, and samples were processed as described above. The cytotoxic effect of different concentrations of AASMPs on MCF-7 cells was also evaluated against growing nucleated mammalian cells (MCF-7) as described earlier (62). In brief, 10,000 MCF-7 cells/well in minimal essential medium, along with a negative control (DMSO) and a positive control (1 mM sodium azide), were incubated for 24 h in 96-well, flat-bottom tissue culture microplates. After incubation, the medium was removed from all wells of the microplate, and then 200 μl of fresh minimal essential medium was added to each well, along with different concentrations of AASMPs in triplicate, followed by further incubation for 44 h. At the end of incubation, MTT (10 μl) at a concentration of 5 mg/ml in PBS was added to each well, and the microplates were wrapped with aluminum foil and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After incubation, all contents of the wells were again removed by using a pipette (cells had adhered to the walls of the wells), and 100 μl of DMSO was put into each well, followed by mixing, and the microplate was kept in the dark overnight. The next day, the absorbance for every well was measured at 570 nm by using a microplate reader.

In vivo antimalarial activity.

The in vivo antimalarial activity of AASMP (4a, 4b, and 4e) was evaluated in a rodent model against MDR (chloroquine, mefloquine, and halofantrine) P. yoelii in BALB/c mice at three dose levels. In brief, five mice (22 ± 2 g) were inoculated intraperitoneally with 105 parasitized RBC on day 0, and the compounds were administered after 6 h of parasite inoculation via the intraperitoneal route. The treatment was continued once daily at each dose level from days 0 to 3 via the intraperitoneal route. The compounds were diluted in groundnut oil so as to obtain the required drug dose per animal in 0.2 ml volume. The parasitemia levels from individual mice were recorded in Giemsa-stained thin blood smears on day 4. The mean value determined for a group of five mice was used to calculate the percent suppression in parasitemia with respect to the vehicle control group. α-β-Arteether-treated mice were used as a positive control.

Statistical analysis.

Data are shown as means ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed by using the Student t test or analysis of variance. Wherever applicable, a P value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Chemistry.

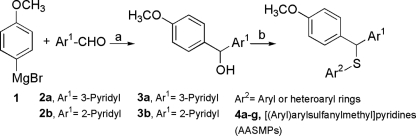

Our method (14) for the synthesis of AASMPs involved S alkylation of different aryl or heteroaryl thiols using carbinols 3a and 3b as the alkylating agents (Fig. 1). The formation of a sulfur link between a diarylmethane and an aryl or a heteroaryl ring can be achieved either by the nucleophilic attack of an aryl or heteroarylthiolate anion on diarylmethyl halides and diarylmethyl-p-tolylsulfonates or by protic or Lewis acid-catalyzed condensation of diarylcarbinols with different aryl or heteroarylthiols (6). Carbinols 3a and 3b were obtained by the Grignard reaction of 4-methoxyphenylmagnesium bromide 1 with pyridine-3-carbaldehyde and pyridine-2-aldehyde, respectively. The S alkylation reactions on carbinols 3a and 3b were achieved in the presence of anhydrous AlCl3 (1.1 eq) in dry benzene at room temperature. However, in the case of S alkylation of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole on carbinol 3a the reaction was performed at reflux condition since 2-mercaptobenzothiazole is insoluble in benzene at room temperature. Although in every case the reaction condition was like that of a typical Friedel-Crafts alkylation reaction due to the higher nucleophilicity of sulfur than that of aromatic ring carbon atoms, nucleophilic attack occurred through sulfur. All of the synthesized AASMPs (4a to 4g) are presented in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Synthesis of AASMPs 4a to 4g. Reagents and conditions: dry tetrahydrofuran, room temperature, 1 h (a) and anhydrous AlCl3, dry benzene, room temperature or reflux, 0.5 h (b).

TABLE 1.

Synthesized AASMPs 4a to 4g

CS LogP, ChemSilico LogP.

CS pKa, ChemSilico pKa.

Inhibition of hemozoin (β-hematin) formation.

The synthesized compounds were tested regarding whether they can inhibit hemozoin formation in vitro. All AASMPs (4a to 4g) inhibited hemozoin formation mediated by both MDR P. yoelii whole-cell lysate and chloroquine-sensitive P. falciparum (NF-54) whole-cell lysate (Table 1). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for the inhibition of hemozoin formation were in the range of 11 to 40 μM. The LogP and pKa values of AASMPs were calculated for further characterization (Table 1).

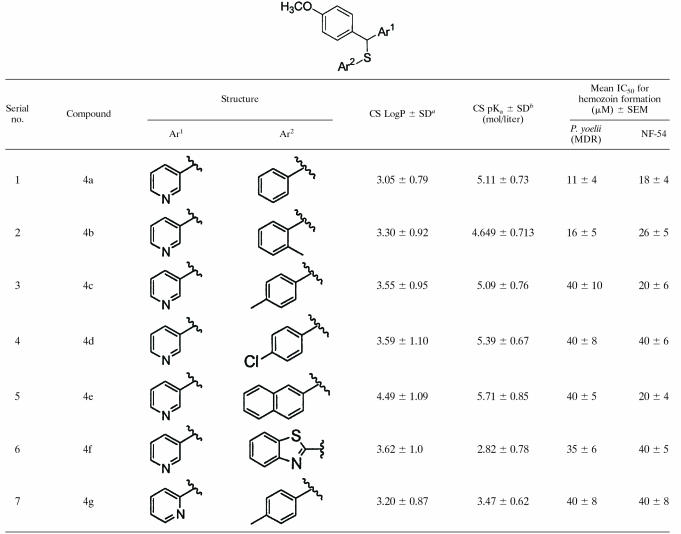

Interaction of AASMP with heme.

Drugs that inhibit hemozoin formation generally interact with free heme. Since AASMP inhibits hemozoin formation, we tested whether it could interact with free heme. Although it is more difficult to study the interaction of drugs with heme under the pH conditions of the food vacuole due to the poor solubility of heme at low pH, to get an accurate picture, the interaction of AASMPs (4a, 4b, 4e, and 4f) with heme was determined at pH 5.2, thus approximating the pH of the parasite food vacuole. A solution of heme at pH 5.2 showed a broad peak at 362 nm, indicating that dimers of the μ-oxo type or the μ-hematin type predominate under our in vitro conditions (7, 32). The addition of AASMPs clearly perturbed the heme spectrum (Fig. 2A, C, E, and G), a finding indicative of an interaction between the AASMP and the heme units. Titration with increasing amounts of AASMPs into the heme solution produced spectra with a well-defined isosbestic point in the Soret range, with reduction in the heme Soret molar absorptivity, and a shift of the Soret band to longer wavelengths. The binding of AASMPs to heme was studied by optical difference spectroscopy (Fig. 2B, D, F, and H). The apparent KD values for the binding of AASMPs to heme, as calculated from the plot of 1/ΔA362 against 1/[AASMPs] were shown in the insets (Fig. 2B, D, F, and H). The mean binding affinities (± the SEM) of AASMPs with heme were determined to be as follows: 4a, 20 ± 4; 4b, 26 ± 6; 4c, 12 ± 3; and 4f, 14 ± 3. Of the KD values compared to the AASMPs, 4e showed the highest affinity.

FIG. 2.

Interaction of AASMPs with heme. (A, C, E, and G) Optical Soret spectroscopy for AASMP-hemin interaction at different concentrations of AASMP (5 to 40 μM) (i, 5 μM; f, 40 μM). (B, D, F, and H) Optical difference spectroscopy for AASMP-hemin complex formation (i, 5 μM; f, 40 μM). The inset shows the plot of 1/Δ360 nm versus 1/[AASMP] to calculate the KD.

Inhibition of P. falciparum growth and development by AASMP.

In view of the observations that AASMP associates with heme and inhibits hemozoin formation, it is expected that AASMPs may show some antiplasmodial activity. Interestingly, all AASMPs (4a to 4g) inhibited the growth of the malaria parasite concentration dependently, but 4a, 4b, and 4e were found to be very potent (IC50 = 4 to 8 μM, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of AASMPs on P. falciparum growth as measured by [3H]hypoxanthine uptake

| Compound | [3H]hypoxanthine uptake (mean IC50 [μM] ± SEM)a |

|---|---|

| 4a | 5 ± 1* |

| 4b | 8 ± 2* |

| 4c | 20 ± 6† |

| 4d | 12 ± 4† |

| 4e | 4 ± 0.5* |

| 4f | 12 ± 2* |

| 4g | 20 ± 7† |

*, P < 0.001; †, P < 0.002.

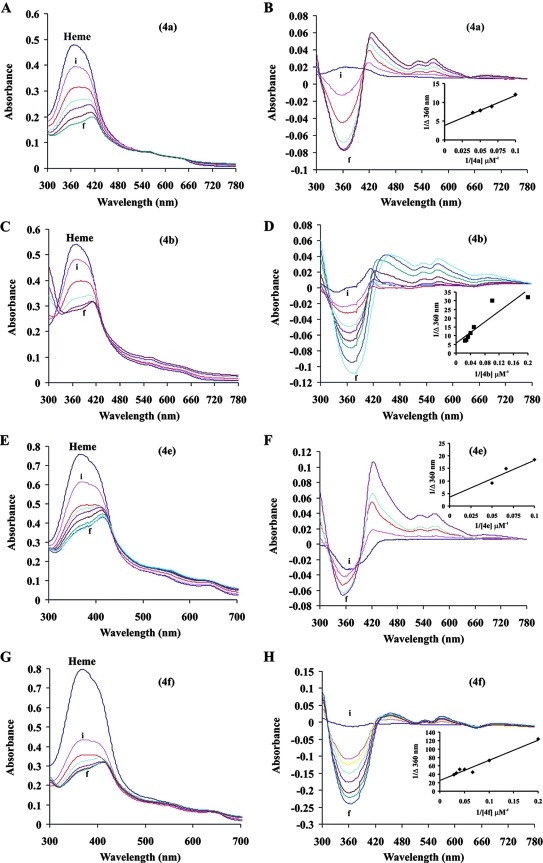

AASMP inhibits hemozoin formation in P. falciparum.

The AASMP concentration dependently also inhibited hemozoin formation in the parasite (Fig. 3A) and increased the heme content in the parasite (Fig. 3B), indicating that the inhibition of hemozoin formation by AASMP may lead to the accumulation of heme in the parasite.

FIG. 3.

AASMP inhibits hemozoin formation and favors the accumulation of heme in the parasite. Hemozoin formation (A) and heme content (B) in P. falciparum were measured in the presence or absence of AASMP as described in Materials and Methods. Values presented are mean ± the SEM. *, P < 0.002; **, P < 0.001 (versus the control).

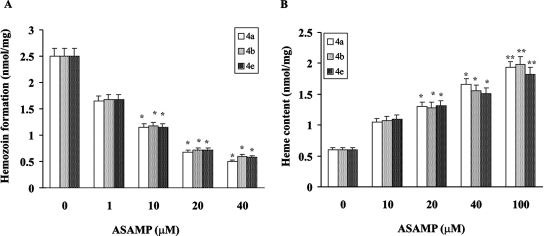

Enhancement of oxidative stress in P. falciparum by AASMP.

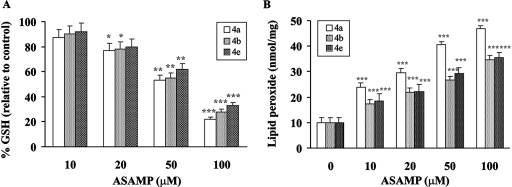

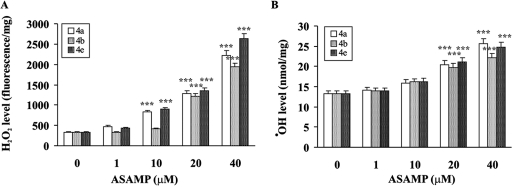

The inhibition of hemozoin formation as a result of heme interaction causes death of the parasite due to the accumulation of toxic free heme and the subsequent development of the oxidative stress (28, 48). The AASMPs 4a, 4b, and 4e, which showed better antiplasmodial activity, were tested to determine whether they can develop oxidative stress in P. falciparum. The GSH level and the formation of lipid peroxide were measured at different concentrations, as indicated (Fig. 4). These selected AASMPs significantly decreased the GSH level (Fig. 4A) and induced the formation of lipid peroxide (Fig. 4B) in the parasite in a concentration-dependent manner. H2O2 and ·OH are very important members of reactive oxygen species, which cause oxidative stress under different situations. To determine whether AASMPs via stimulating the accumulation of intraparasitic H2O2 reduced the GSH level and stimulated the lipid peroxidation, intraparasitic H2O2 level was measured. Interestingly, these AASMPs also significantly (P < 0.001) increased the generation of intraparasitic H2O2 (Fig. 5A) and stimulated the generation of highly reactive ·OH in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 4.

Enhancement of oxidative stress in P. falciparum by AASMP. (A and B) The percent alteration of GSH (relative to the control) (A) and lipid peroxide (B) in P. falciparum was measured at different concentrations of AASMP as indicated. Values are means ± the SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.002; ***, P < 0.001 (versus the control).

FIG. 5.

AASMP stimulates the generation of intraparasitic H2O2 and ·OH. The levels of H2O2 (A) and ·OH (B) in P. falciparum were measured at different concentrations of AASMP as indicated. Values are means ± the SEM. ***, P < 0.001 (versus the control).

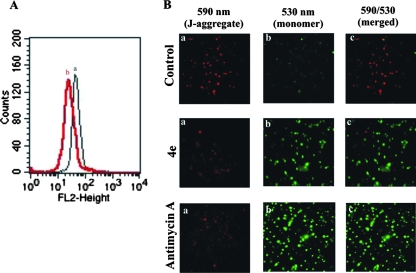

AASMP reduces parasite-mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Δψm).

Generation of reactive oxygen species and associated oxidative stress causes mitochondrial dysfunction (4). In order to investigate whether oxidative stress induced by AASMP can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction in malaria parasite, alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), a marker for dysfunction, was measured. The Δψm was investigated by using membrane potential sensitive dye, JC1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide). In intact healthy mitochondria with higher Δψm, JC1 would be accumulated in mitochondrial matrix to form J-aggregate, showing intense fluorescence at 590 nm. Mitochondria with open transition pores would be at low Δψm, and the accumulation of JC1 would be less in the matrix, leading to less availability of JC1 to form aggregates, showing weak fluorescence at 590 nm. Both fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Fig. 6A) and fluorescence microscopic (Fig. 6B) studies were done to measure the Δψm in the presence or absence of the most effective AASMP (4e). Compound 4e effectively decreased the Δψm (Fig. 6Ab) compared to the control (Fig. 6Aa). Fluorescence microscopic analysis clearly indicated that the formation of J-aggregate (red fluorescence, 590 nm) (Fig. 6Ba) or the ratio of 590 nm to 530 nm (Fig. 6Bc) in the trophozoite-infected red cell (control) was higher than that for 4e or antimycin A (positive control)-treated trophozoite-infected red cells. In contrast, the green fluorescence (JC1 monomer, 530 nm) was much less in the control compared to 4e or antimycin A-treated cells (Fig. 6Bb). Thus, AASMP alters the mitochondrial potential of the malaria parasite.

FIG. 6.

AASMP reduces the mitochondrial transmembrane potential of the malaria parasite. (A) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential in control (a) and AASMP (4e)-treated (b) trophozoite-infected red cells as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Fluorescence microscopic analysis of transmembrane potential in control and 4e- and antimycin A (10 μM)-treated trophozoite-infected red cells. (a) Panel for J-aggregate formation (emission, 590 nm); (b) panel for JC1 monomer (emission, 530 nm); (c) panel for 590 nm/530 nm ratio (merged).

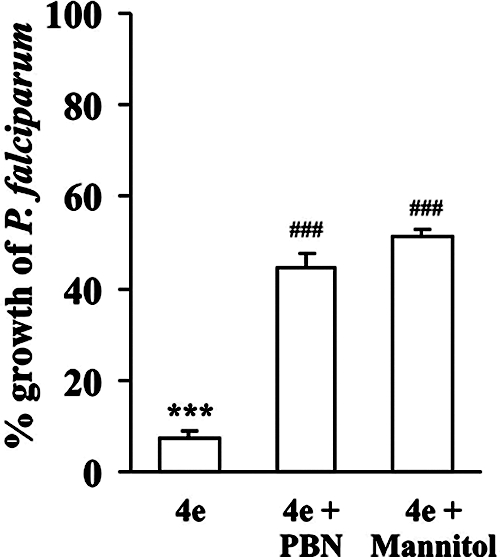

Critical role of reactive oxygen species for AASMP-induced parasite growth inhibition.

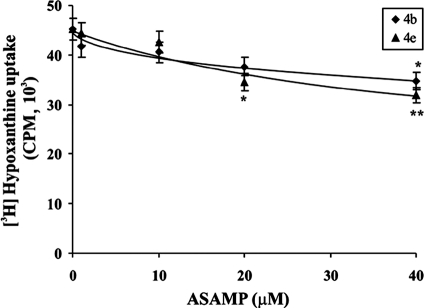

In order to assess whether the oxidative stress induced by AASMP is actually responsible for the inhibition of parasite growth, the effect of different antioxidant or ·OH scavengers, such as mannitol and spin traps like PBN, was studied on AASMP-induced P. falciparum death. The results indicated that ·OH scavengers significantly (P < 0.05) protected P. falciparum from AASMP-induced growth inhibition (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Effect of ·OH scavengers on AASMP-induced growth inhibition of P. falciparum. P. falciparum growth was measured as the [3H]hypoxanthine uptake in the presence or absence of ·OH scavengers during AASMP (4e, 40 μM) treatment as described in Materials and Methods. P. falciparum culture (4% parasitemia) was treated with AASMP (4e), along with PBN (40 mM) or mannitol (10 mM) for 48 h. The data presented are means ± the SEM (n = 6). ***, P < 0.001 (versus control); ###, P < 0.05 (versus treated).

In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of selected active compounds.

Thus far, we have demonstrated that AASMP offers an antimalarial effect by enhancing oxidative stress in P. falciparum. However, AASMP has a pyridine moiety and is highly hydrophobic, which may lead to damaging the RBC membrane. Thus, we investigated whether AASMP has any specificity toward the malaria parasite or whether it lyses any type of biological membrane, including the RBC membrane. The normal uninfected RBC were incubated with AASMP at different concentrations. After incubation, RBC were infected with P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes, and the uptake of [H3]hypoxanthine was monitored. The incorporation of [H3]hypoxanthine in P. falciparum cultured in RBC treated with different concentrations of AASMP (4b and 4e) was comparable to that of the control (Fig. 8). These results suggested that AASMPs at up to 40 μM did not affect the ability of RBC to support parasite invasion and growth. Therefore, it can be concluded that AASMP does not affect the viability of the RBC and that its antimalarial action is specific to the parasite only. We also evaluated the toxicity of AASMPs on nucleated proliferating mammalian MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were incubated with 10 to 1,000 μM AASMPs, and MTT oxidation was monitored to determine the viability. Again, AASMP did not show any significant toxicity in mammalian nucleated cells also, and the selectivity index was greater than 100 (Table 3).

FIG. 8.

Toxicity of selected active compounds (4b and 4e) toward RBC. Fresh and uninfected human B+ RBC were incubated with the indicated concentrations of AASMP for 24 h. After the completion of incubation, the cells were washed three times with CRPMI medium and infected with P. falciparum culture. [3H]hypoxanthine uptake was studied as described in Materials and Methods. The incorporation of [3H]hypoxanthine is presented in counts per minute. The data presented are mean ± the SEM (n = 6). *, P < 0.02; **, P < 0.05 (versus the control).

TABLE 3.

In vitro cytotoxicity against nucleated proliferating mammalian cells (MCF-7) of selected active compounds 4a, 4b, and 4e and against P. falciparum (NF-54)

| AASMP | MCF-7 (mean IC50 [μM] ± SEM) | MCF-7/NF-54 SIa |

|---|---|---|

| 4a | 1,000 ± 60 | 200 |

| 4b | 1,000 ± 50 | 125 |

| 4e | 650 ± 20 | 163 |

SI, selectivity index, calculated as cytotoxicity IC50/antiplasmodial IC50.

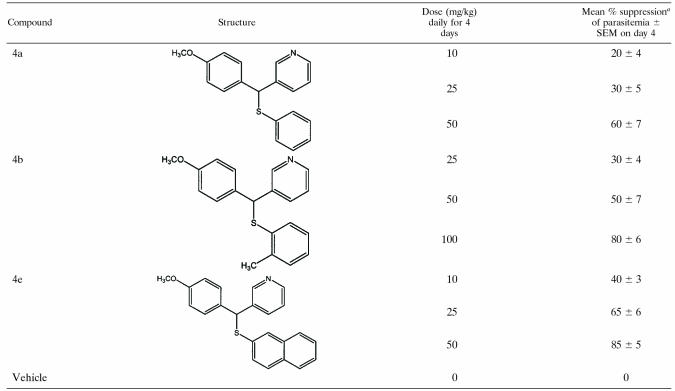

In vivo antimalarial activity against the malaria parasite MDR P. yoelii.

In vitro antimalarial activity of AASMP encouraged us to evaluate the effect of AASMP against multidrug resistant rodent malarial parasite MDR P. yoelii in vivo. Interestingly, AASMP showed antimalarial activity in vivo. Compound 4a suppressed the day 4 mean parasitemia by 20, 30, and 60% at doses of 10, 25, and 50 mg/kg, respectively (Table 4). Compound 4b suppressed the day 4 mean parasitemia by 30, 50, and 80% at doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg, respectively (Table 4). Compound 4e suppressed the day 4 mean parasitemia by 40, 65, and 85% at dose levels of 10, 25, and 50 mg/kg, respectively (Table 4). Thus, 4a or 4b was effective, but 4e was found to be comparatively much more effective at low concentrations in demonstrating an antimalarial effect in vivo in the rodent model.

TABLE 4.

Antiplasmodial activity of AASMPs (4a, 4b, and 4e) against MDR strain P. yoelii in BALB/c mice

Percent suppression was calculated as [(C − T)/C] × 100, where C is the parasitemia in the control group, and T is the parasitemia in the treated group.

DISCUSSION

Evidence has been presented to show that AASMP has antiplasmodial activity. The mechanistic studies reveal that it effectively inhibits hemozoin formation and induces oxidative stress in the malaria parasite to inhibit P. falciparum growth. The data indicate that this novel class of antimalarial shows selective activity against the malaria parasite with a selectivity index of greater than 100 and offers antimalarial activity in vivo in the rodent model.

Compounds that inhibit hemozoin formation usually interact with heme. The addition of AASMP clearly perturbed the heme spectrum, a finding indicative of an interaction between the AASMP and the heme units. The spectral changes of heme-AASMP mixtures were similar to those observed for molecular complex formation between metalloporphyrines and other aromatic molecules involving a cofacial π-π interaction (67).

Although all synthesized compounds showed antiplasmodial activity, compounds 4c, 4f, or 4g showed higher IC50 values than compounds 4a, 4b, 4c, 4d, and 4e. The reason for the higher IC50 values for 4f or 4g is probably due to less accumulation in the parasite food vacuole by pH trapping for higher pKa values. LogP and pKa values of AASMPs (4a, 4b, 4c, 4d, and 4e) are suitable for the accumulation in the food vacuole of the parasite through pH trapping since the pKa values are close to or little greater than the pH (pH 4.5 to 5.2) of the parasite food vacuole. However, the pKa values of compounds 4f and 4g (Table 1) are not suitable for the accumulation in the food vacuole of the parasite through pH trapping, but we cannot exclude some other mechanism by which these two compounds may enter in the food vacuole.

The possible mechanism by which AASMP develops oxidative stress and parasite death is mediated through its inhibitory effect on hemozoin formation. The inhibition of hemozoin formation causes death of the parasite due to the accumulation of toxic free heme (28). Free heme can damage cellular metabolism of the malaria parasite by inhibiting enzymes, promoting the peroxidation of membranes and the production of reactive oxygen species in the acidic environment of the food vacuole (29, 30, 48). It also well known that the malaria parasite is very much susceptible to oxidative stress (11, 21, 73). Inhibition of heme detoxification function is known to kill the parasite through membrane lysis and the interference of other vital functions (20, 40, 60).

Our studies indicate that AASMP-induced oxidative stress is associated with the reduction of Δψm. The loss of Δψm is considered one of the most significant events in the oxidative stress-mediated mitochondrial pathway of cell death (27, 47, 74). It is already known that the alteration of Δψm in the malaria parasite causes mitochondrial dysfunction, which may lead to parasite death. Atovaquone, a well-known antimalarial, inhibits parasite growth that reduces mitochondrial membrane potential (34, 57).

If AASMP inhibits P. falciparum growth through the induction of oxidative stress, antioxidant treatment should protect the parasite from AASMP-induced parasite death. ·OH scavengers and spin traps remarkably protected P. falciparum from growth inhibition. Since PBN or mannitol significantly protected (50 to 57%) P. falciparum from AASMP-induced growth inhibition, it can be suggested that ·OH is the major reactive oxygen species generated by AASMP to offer antimalarial effect. Since PBN or mannitol can scavenge ·OH and did not offer 100% protection, we cannot rule out the role of H2O2 or other reactive oxygen species for AASMP-induced parasite growth inhibition.

Interestingly, this class of compound exhibits acceptable selectivity against the malaria parasite and shows antimalarial activity in vivo against the MDR rodent malaria parasite P. yoelii. In conclusion, this study has identified AASMP as a new class of TRSMs with antiplasmodial activity both in vitro and in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.K., S.K.D., M.G., and V.C. gratefully acknowledge the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, India, for providing Senior Research fellowships to carry out this work and providing funds through SIP0007 project.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 November 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

Central Drug Research Institute communication 7191.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Qawasmeh, R. A., Y. Lee, M. Y. Cao, X. Gu, A. Vassilakos, J. A. Wright, and A. Young. 2004. Triaryl methane derivatives as antiproliferative agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14:347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancelin, M. L., H. J. Vial, and J. R. Philippot. 1985. Inhibitors of choline transport into Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes are effective antiplasmodial compounds in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 34:4068-4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babbs, C. F., and M. G. Steiner. 1990. Detection and quantitation of hydroxyl radical using dimethyl sulfoxide as molecular probe. Methods Enzymol. 186:137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begriche, K., A. Igoudjil, D. Pessayre, and B. Fromenty. 2006. Mitochondrial dysfunction in NASH: causes, consequences and possible means to prevent it. Mitochondrion 6:1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas, K., U. Bandyopadhyay, I. Chattopadhyay, A. Varadaraj, E. Ali, and R. K. Banerjee. 2003. A novel antioxidant and antiapoptotic role of omeprazole to block gastric ulcer through scavenging of hydroxyl radical. J. Biol. Chem. 278:10993-11001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolshan, Y., C. Y. Chen, J. R. Chilenski, F. Gosselin, D. J. Mathre, P. D. O'Shea, A. Roy, and R. D. Tillyer. 2004. Nucleophilic displacement at benzhydryl centers: asymmetric synthesis of 1,1-diarylalkyl derivatives. Org. Lett. 6:111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, S. B., M. Shillcock, and P. Jones. 1976. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of the aggregation of porphyrins in aqueous solution. Biochem. J. 153:279-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buege, J. A., and S. D. Aust. 1978. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 52:302-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chattopadhyay, I., U. Bandyopadhyay, K. Biswas, P. Maity, and R. K. Banerjee. 2006. Indomethacin inactivates gastric peroxidase to induce reactive-oxygen-mediated gastric mucosal injury and curcumin protects it by preventing peroxidase inactivation and scavenging reactive oxygen. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 40:1397-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choubey, V., P. Maity, M. Guha, S. Kumar, K. Srivastava, S. K. Puri, and U. Bandyopadhyay. 2007. Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum choline kinase by hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide: a possible antimalarial mechanism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:696-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark, I. A., and N. H. Hunt. 1983. Evidence for reactive oxygen intermediates causing hemolysis and parasite death in malaria. Infect. Immun. 39:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coban, C., K. J. Ishii, D. J. Sullivan, and N. Kumar. 2002. Purified malaria pigment (hemozoin) enhances dendritic cell maturation and modulates the isotype of antibodies induced by a DNA vaccine. Infect. Immun. 70:3939-3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cossarizza, A., M. Baccarani-Contri, G. Kalashnikova, and C. Franceschi. 1993. A new method for the cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using the J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 197:40-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das, S. K., Shagufta, and G. Panda. 2005. An easy access to unsymmetric trisubstituted methane derivatives (TRSMs). Tetrahedron Lett. 46:3097-3102. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desjardins, R. E., C. J. Canfield, J. D. Haynes, and J. D. Chulay. 1979. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16:710-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egan, T. J. 2003. Haemozoin (malaria pigment): a unique crystalline drug target. Targets 2:115-124. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan, T. J. 2004. Haemozoin formation as a target for the rational design of new antimalarials. Drug Design Rev. 1:93-110. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egan, T. J. 2002. Physico-chemical aspects of hemozoin (malaria pigment) structure and formation. J. Inorg. Biochem. 91:19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egan, T. J. 2001. Structure-function relationships in chloroquine and related 4-aminoquinoline antimalarials. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 1:113-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis, S. E., D. J. Sullivan, Jr., and D. E. Goldberg. 1997. Hemoglobin metabolism in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:97-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman, M. J. 1979. Oxidant damage mediates variant red cell resistance to malaria. Nature 280:245-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli, U., L. Lazzarato, M. Bertinaria, G. Sorba, A. Gasco, S. Parapini, and D. Taramelli. 2005. Synthesis and antimalarial activities of some furoxan sulfones and related furazans. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 40:1335-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gemma, S., G. Campiani, S. Butini, G. Kukreja, B. P. Joshi, M. Persico, B. Catalanotti, E. Novellino, E. Fattorusso, V. Nacci, L. Savini, D. Taramelli, N. Basilico, G. Morace, V. Yardley, and C. Fattorusso. 2007. Design and synthesis of potent antimalarial agents based on clotrimazole scaffold: exploring an innovative pharmacophore. J. Med. Chem. 50:595-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman, I. F., S. H. Qari, J. Skinner, S. Oliveira, J. M. Nascimento, M. M. Povoa, W. E. Collins, and A. A. Lal. 1992. Use of glass beads and CF 11 cellulose for removal of leukocytes from malaria-infected human blood in field settings. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 87:583-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwood, B., and T. Mutabingwa. 2002. Malaria in 2002. Nature 415:670-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guha, M., S. Kumar, V. Choubey, P. Maity, and U. Bandyopadhyay. 2006. Apoptosis in liver during malaria: role of oxidative stress and implication of mitochondrial pathway. FASEB J. 20:1224-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jing, X. B., X. B. Cai, H. Hu, S. Z. Chen, B. M. Chen, and J. Y. Cai. 2007. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial membrane potential are modulated during CDDP-induced apoptosis in EC-109 cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 85:265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kannan, R., K. Kumar, D. Sahal, S. Kukreti, and V. S. Chauhan. 2005. Reaction of artemisinin with haemoglobin: implications for antimalarial activity. Biochem. J. 385:409-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar, S., and U. Bandyopadhyay. 2005. Free heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol. Lett. 157:175-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar, S., M. Guha, V. Choubey, P. Maity, and U. Bandyopadhyay. 2007. Antimalarial drugs inhibiting hemozoin (beta-hematin) formation: a mechanistic update. Life Sci. 80:813-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambros, C., and J. P. Vanderberg. 1979. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J. Parasitol. 65:418-420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemberg, R., and J. Legge. 1949. Hematin compounds and bile pigments: their constitution, metabolism, and function. Interscience Publishers, New York, NY.

- 33.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mather, M. W., E. Darrouzet, M. Valkova-Valchanova, J. W. Cooley, M. T. McIntosh, F. Daldal, and A. B. Vaidya. 2005. Uncovering the molecular mode of action of the antimalarial drug atovaquone using a bacterial system. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27458-27465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNally, J., S. M. O'Donovan, and J. P. Dalton. 1992. Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi: development of simple in vitro erythrocyte invasion assays. Parasitology 105(Pt. 3):355-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motterlini, R., R. Foresti, K. Vandegriff, M. Intaglietta, and R. M. Winslow. 1995. Oxidative-stress response in vascular endothelial cells exposed to acellular hemoglobin solutions. Am. J. Physiol. 269:H648-H655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munzel, T., I. B. Afanas'ev, A. L. Kleschyov, and D. G. Harrison. 2002. Detection of superoxide in vascular tissue. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22:1761-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nair, V., S. Thomas, S. C. Mathew, and K. G. Abhilash. 2006. Recent advances in the chemistry of triaryl- and triheteroarylmethanes. Tetrahedron 62:6731-6747. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novelli, F., B. Tasso, and F. Sparatore. 1999. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of some thiolupinine derivatives. Farmaco 54:354-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orjih, A. U., H. S. Banyal, R. Chevli, and C. D. Fitch. 1981. Hemin lyses malaria parasites. Science 214:667-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pagola, S., P. W. Stephens, D. S. Bohle, A. D. Kosar, and S. K. Madsen. 2000. The structure of malaria pigment beta-haematin. Nature 404:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panda, G., J. K. Mishra, S. Sinha, A. K. Gaikwad, A. K. Srivastava, R. Srivastava, and B. S. Srivastava. 2005. 4-[10-(Methoxybenzyl)-9-anthryl]phenol derivatives as new antitubercular agents. Arkivoc ii:29-45. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panda, G., M. K. Parai, S. K. Das, Shagufta, M. Sinha, V. Chaturvedi, A. K. Srivastava, Y. S. Manju, A. N. Gaikwad, and S. Sinha. 2007. Effect of substituents on diarylmethanes for antitubercular activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 42:410-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panda, G., Shagufta, J. K. Mishra, V. Chaturvedi, A. K. Srivastava, R. Srivastava, and B. S. Srivastava. 2004. Diaryloxy methano phenanthrenes: a new class of antituberculosis agents. Bioorg Med. Chem. 12:5269-5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panda, G., Shagufta, A. K. Srivastava, and S. Sinha. 2005. Synthesis and antitubercular activity of 2-hydroxy-aminoalkyl derivatives of diaryloxy methano phenanthrenes. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 15:5222-5225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pandey, A. V., N. Singh, B. L. Tekwani, S. K. Puri, and V. S. Chauhan. 1999. Assay of beta-hematin formation by malaria parasite. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal. 20:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piccoli, C., R. Scrima, G. Quarato, A. D'Aprile, M. Ripoli, L. Lecce, D. Boffoli, D. Moradpour, and N. Capitanio. 2007. Hepatitis C virus protein expression causes calcium-mediated mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction and nitro-oxidative stress. Hepatology 46:58-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Portela, C., C. M. Afonso, M. M. Pinto, and M. J. Ramos. 2004. Definition of an electronic profile of compounds with inhibitory activity against hematin aggregation in malaria parasite. Bioorg Med. Chem. 12:3313-3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenthal, P. J., and S. R. Meshnick. 1998. Hemoglobin processing and the metabolism of amino acids, heme and iron, p. 145-158. In I. W. Sherman (ed.), Malaria: parasite biology, pathogenesis and protection. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 50.Sachs, J., and P. Malaney. 2002. The economic and social burden of malaria. Nature 415:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saliba, K. J., and K. Kirk. 1998. Clotrimazole inhibits the growth of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92:666-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santelli-Rouvier, C., B. Pradines, M. Berthelot, D. Parzy, and J. Barbe. 2004. Arylsulfonyl acridinyl derivatives acting on Plasmodium falciparum. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 39:735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schejter, A., A. Lanir, and N. Epstein. 1976. Binding of hydrogen donors to horseradish peroxidase: a spectroscopic study. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 174:36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shagufta, A. Kumar, G. Panda, and M. I. Siddiqi. 2007. CoMFA and CoMSIA 3D-QSAR analysis of diaryloxy-methano-phenanthrene derivatives as anti-tubercular agents. J. Mol. Model. 13:99-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shagufta, A. K. Srivastava, R. Sharma, R. Mishra, A. K. Balapure, P. S. Murthy, and G. Panda. 2006. Substituted phenanthrenes with basic amino side chains: a new series of anti-breast cancer agents. Bioorg Med. Chem. 14:1497-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Solomon, V. R., S. K. Puri, K. Srivastava, and S. B. Katti. 2005. Design and synthesis of new antimalarial agents from 4-aminoquinoline. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13:2157-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Srivastava, I. K., and A. B. Vaidya. 1999. A mechanism for the synergistic antimalarial action of atovaquone and proguanil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1334-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Srivastava, N., Sangita, S. Ray, M. M. Singh, A. Dwivedi, and A. Kumar. 2004. Diaryl naphthyl methanes, a novel class of anti-implantation agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 12:1011-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sullivan, D. J., Jr., I. Y. Gluzman, and D. E. Goldberg. 1996. Plasmodium hemozoin formation mediated by histidine-rich proteins. Science 271:219-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tekwani, B. L., and L. A. Walker. 2005. Targeting the hemozoin synthesis pathway for new antimalarial drug discovery: technologies for in vitro beta-hematin formation assay. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 8:63-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tiffert, T., H. Ginsburg, M. Krugliak, B. C. Elford, and V. L. Lew. 2000. Potent antimalarial activity of clotrimazole in in vitro cultures of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:331-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Timur, M., S. H. Akbas, and T. Ozben. 2005. The effect of Topotecan on oxidative stress in MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Acta Biochim. Pol. 52:897-902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trager, W., and J. B. Jensen. 1976. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science 193:673-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trivedi, V., P. Chand, P. R. Maulik, and U. Bandyopadhyay. 2005. Mechanism of horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed heme oxidation and polymerization (beta-hematin formation). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1723:221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trivedi, V., P. Chand, K. Srivastava, S. K. Puri, P. R. Maulik, and U. Bandyopadhyay. 2005. Clotrimazole inhibits hemoperoxidase of Plasmodium falciparum and induces oxidative stress: proposed antimalarial mechanism of clotrimazole. J. Biol. Chem. 280:41129-41136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Veldkamp, W. B., and J. R. Votano. 1976. Effects of intermolecular interaction on protein diffusion in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 80:2794-2801. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vippagunta, S. R., A. Dorn, H. Matile, A. K. Bhattacharjee, J. M. Karle, W. Y. Ellis, R. G. Ridley, and J. L. Vennerstrom. 1999. Structural specificity of chloroquine-hematin binding related to inhibition of hematin polymerization and parasite growth. J. Med. Chem. 42:4630-4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vlahakis, J. Z., R. T. Kinobe, K. Nakatsu, W. A. Szarek, and I. E. Crandall. 2006. Anti-Plasmodium activity of imidazole-dioxolane compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16:2396-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Votano, J. R., M. Parham, L. H. Hall, and L. B. Kier. 2004. New predictors for several ADME/Tox properties: aqueous solubility, human oral absorption, and Ames genotoxicity using topological descriptors. Mol. Diversity 8:379-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Votano, Joseph, R., M. Parham, Lowell H. Hall, Lemont B. Kier, and L. M. Hall. 2004. Prediction of aqueous solubility based on large datasets using several QSPR models utilizing topological structure representation. Chem. Biodiversity 1:1829-1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.White, N. J. 2004. Antimalarial drug resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 113:1084-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization 2000. WHO report: WHO Expert Committee on Malaria. W. H. O. Tech. Rep. Ser. 892:1-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wozencraft, A. O., H. M. Dockrell, J. Taverne, G. A. Targett, and J. H. Playfair. 1984. Killing of human malaria parasites by macrophage secretory products. Infect. Immun. 43:664-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zorov, D. B., C. R. Filburn, L. O. Klotz, J. L. Zweier, and S. J. Sollott. 2000. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J. Exp. Med. 192:1001-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.