Abstract

Previous N-ethylmaleimide-labeling studies show that ligand binding increases the reactivity of single-Cys mutants located predominantly on the periplasmic side of LacY and decreases reactivity of mutants located for the most part on the cytoplasmic side. Thus, sugar binding appears to induce opening of a periplasmic pathway with closing of the cytoplasmic cavity resulting in alternative access of the sugar-binding site to either side of the membrane. Here we describe the use of a fluorescent alkylating reagent that reproduces the previous observations with respect to sugar binding. We then show that generation of an H+ electrochemical gradient (Δμ̄H +, interior negative) increases the reactivity of single-Cys mutants on the periplasmic side of the sugar-binding site and in the putative hydrophilic pathway. The results suggest that Δμ̄H +, like sugar, acts to increase the probability of opening on the periplasmic side of LacY.

Keywords: bioenergetics, transport, membranes, membrane proteins, permease

LacY, a member of the Major Facilitator Superfamily of membrane transport proteins, catalyzes the stoichiometric translocation of one galactopyrananoside with an H+ (reviewed in 1; 2). As such, LacY utilizes the free energy stored in an H+ electrochemical gradient (Δμ̄H +; interior negative and/or alkaline) to drive accumulation of galactosidic sugars against a concentration gradient (i.e., the free energy released from the downhill movement of H+ with Δμ̄H + is utilized to drive sugar accumulation uphill against a concentration gradient). Conversely, LacY can use the free energy released from downhill translocation of galactosides to drive uphill translocation of H+ with generation of Δμ̄H +, the polarity of which depends on the direction of the sugar gradient.

LacY has been solubilized, purified and reconstituted into proteoliopsomes in a fully functional state3. An X-ray structure of the LacY mutant C154G has been solved in an inward-facing conformation 4; 5, and wild-type LacY has the same global fold 2; 6; 7. LacY is organized into two pseudo-symmetrical α-helical bundles. Perpendicular to the plane of the membrane, the molecule is heart-shaped with a large interior hydrophilic cavity open to the cytoplasm, representing the inward-facing conformation. Within the cavity, a single sugar is observed at the apex of the cavity near the approximate middle of the molecule. The periplasmic side of LacY is completely blocked with respect to sugar access to the binding site, which makes it highly likely that a pathway must form on this side during turnover.

Functional LacY devoid of eight native Cys residues (C-less LacY) has been engineered by constructing a cassette lacY gene with unique restriction sites about every 100 bp 8. Utilizing this cassette lacY for Cys-scanning mutagenesis, a highly useful library of molecules with a single-Cys residue at almost every position of LacY has been constructed 9. Cys is average in bulk, relatively hydrophobic and amenable to highly specific modification. Therefore, Cys-scanning mutagenesis has been used in combination with biochemical and biophysical techniques to reveal membrane topology10, accessibility of intramembrane positions to the aqueous or lipid phase of the membrane 9; 11-15, and spatial proximity between transmembrane domains 16-19.

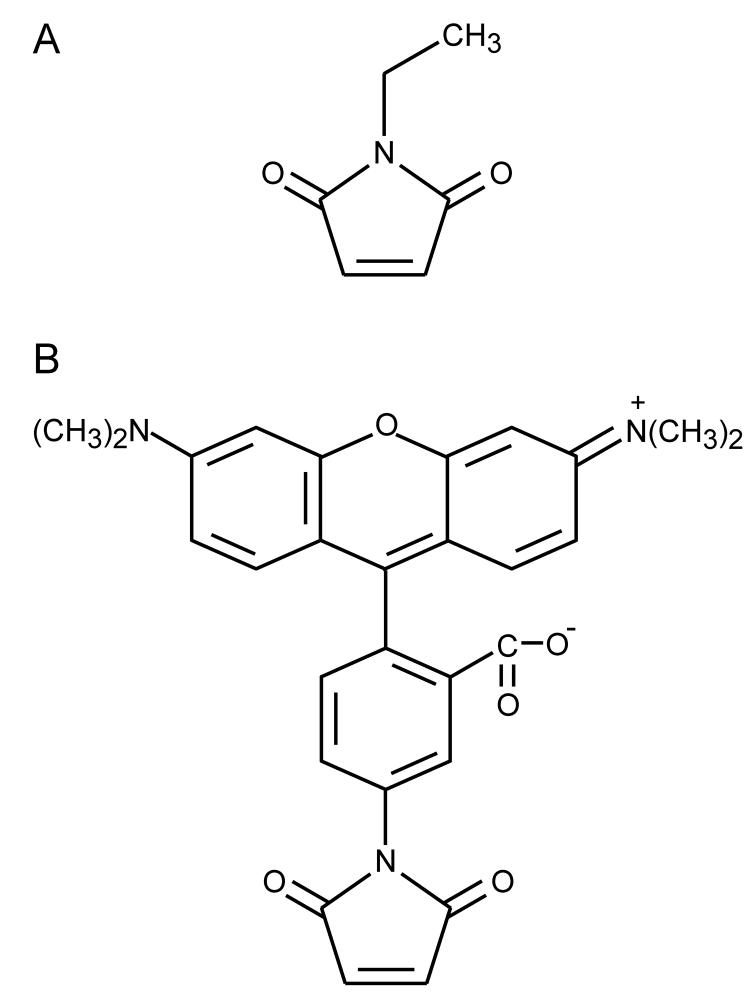

Site-directed sulfhydryl modification by N-[1-14C]ethylmaleimide (NEM), a small, membrane-permeant alkylating agent (Fig. 1A), has been used to study reactivity of single-Cys LacY mutants in C-less background in right-side-out (RSO) membrane vesicles, providing valuable information with regard to structure, function and dynamics of LacY 15; 20-28. The reactivity/accessibility of Cys residues depends on the surrounding environment and is limited by close contacts between transmembrane helices and/or the low dielectric of the environment. Ligand binding increases NEM reactivity of single-Cys replacements located predominantly on the periplasmic side of LacY and decreases reactivity of those located predominantly on the cytoplasmic side 28. This pattern suggests that during sugar transport, a periplasmic pathway opens with closing of the inward-facing cavity so that the sugar-binding site is alternatively accessible to either face of the membrane. The alternative access model for lactose/H+ symport is supported further by functional studies 2, single molecule fluorescence 29 and X-ray crystallography 4; 5.

Figure 1.

Structures of NEM (A) and TMRM (B).

In this study, we first demonstrate that TDG binding increases or decreases labeling of seventy-one single-Cys mutants with a fluorescent alkylating agent, tetramethylrhodamine-5-maleimide (TMRM; Fig. 1B), in a pattern that is qualitatively identical to that observed previously with NEM (see ref 28). We then go on to the major focus of the paper, which is to investigate the effect of Δμ̄H + on the reactivity of selected single-Cys replacements in LacY. Out of the seventy-one mutants tested, Δμ̄H + increases the reactivity of fourteen, ten of which are located within the putative periplasmic pathway, indicating that Δμ̄H + increases the probability of opening on the periplasmic side of the membrane.

Results

TMRM labeling of single-Cys LacY mutants

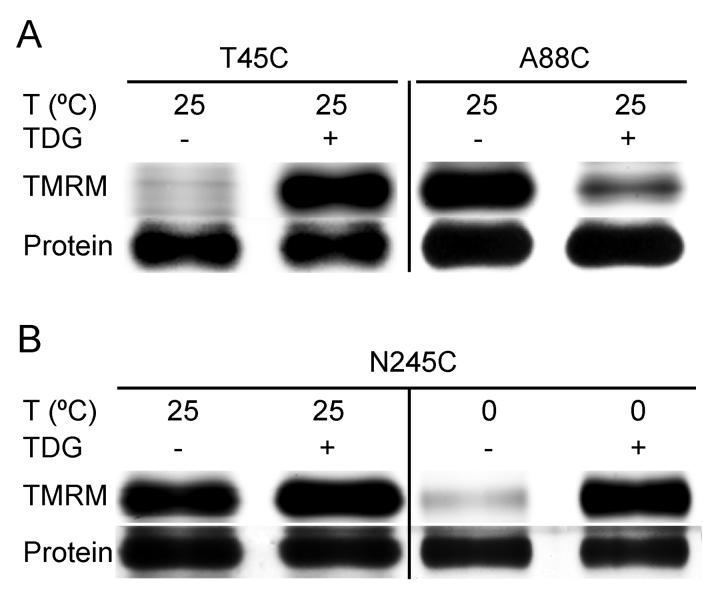

A new alkylation method was developed using the hydrophobic fluorescent reagent, TMRM. Due to the high sensitivity of fluorescence detection, less than one-tenth of materials are used relative to the previous NEM labeling method 22; 30, and results are obtained much more rapidly. TMRM is a large molecule compared with NEM (Fig. 1), but labeling of single-Cys mutants and the effects of ligand binding with this reagent are very comparable to observations with NEM labeling. For example, almost no labeling with TMRM is observed for mutant T45C in absence of TDG, while markedly increased reactivity is observed in the presence of the sugar (Fig. 2A) 25. As with NEM 15, TMRM labels mutant A88C strongly in absence of sugar, and TDG binding decreases labeling (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, as shown previously 24, lowering the temperature of the reaction may dramatically enhance the effect of ligand on reactivity, as shown with mutant N245C (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of TDG and/or temperature on TMRM reactivity of single-Cys mutants. RSO membrane vesicles (0.1 mg of protein in 50 μl) prepared from E. coli with given single-Cys replacements [(A) mutants T45C and A88C; (B) mutant N245C] were incubated for 15 min at 25 °C or 0 °C in the absence or presence of TDG with 40 μM TMRM. DTT was added to terminate the reactions, and DDM was used to solubilize the membrane. Biotinylated proteins were purified, subjected to SDS-PAGE. TMRM-labeled (upper panels) and silver-stained (lower panels) bands corresponding to LacY were imaged and measured qualitatively as described in Materials and Methods.

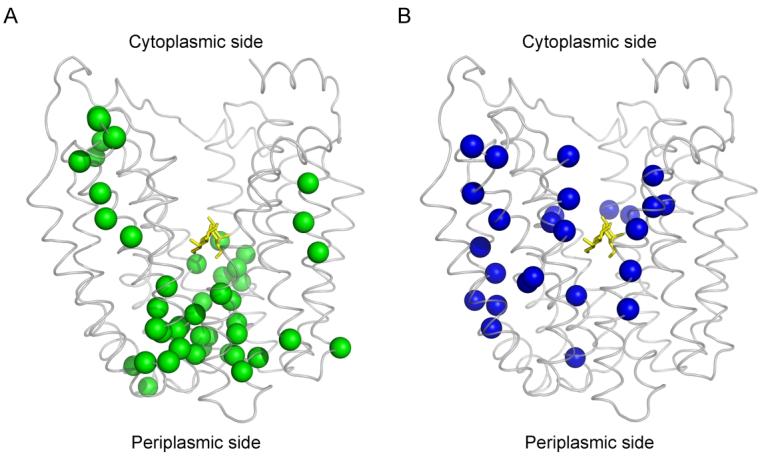

To further test the methodology, seventy-one single-Cys mutants that showed obvious changes of NEM labeling induced by TDG binding were examined for the effect of ligand on TMRM reactivity (Fig. 3). The lactose homologue increases reactivity of Cys mutants mainly on the periplasmic side of the sugar-binding site (Fig. 3, green spheres), and decreases in reactivity are observed for the most part with mutants on the cytoplasmic side (Fig. 3; blue spheres). The pattern observed is virtually identical qualitatively to that observed with NEM 28.

Figure 3.

Distribution of single-Cys replacements exhibiting TDG-induced changes in TMRM reactivity. Seventy-one single-Cys LacY mutants were labeled with TMRM in the absence and presence of TDG as described in Fig. 2. Positions of Cys replacements that exhibit changes in TMRM reactivity are superimposed on the backbone of LacY (Protein Data Bank ID code 1PV7; www.pdb.org). LacY is viewed perpendicular to the membrane with the N-terminal helix bundle on the left and the C-terminal bundle on the right. (A) green spheres, increased TMRM reactivity at positions 2, 3, 8, 12, 14, 17, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 42, 44, 45, 49, 53, 70, 71, 96, 100, 136, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 241, 242, 244, 245, 246, 248, 265, 291, 295, 298, 308, 315, 359, 361, 362, 363 and 364; (B) blue spheres, decreased TMRM reactivity at positions 4, 5, 11, 15, 21, 22, 27, 34, 60, 81, 84, 86, 87, 88, 122, 141, 145, 148, 264, 268, 272, 327, 329, 331, 356 and 357. TDG is shown as a stick model at the apex of the inward-facing cavity (yellow sticks).

Effect of Δμ̄H + on TMRM reactivity

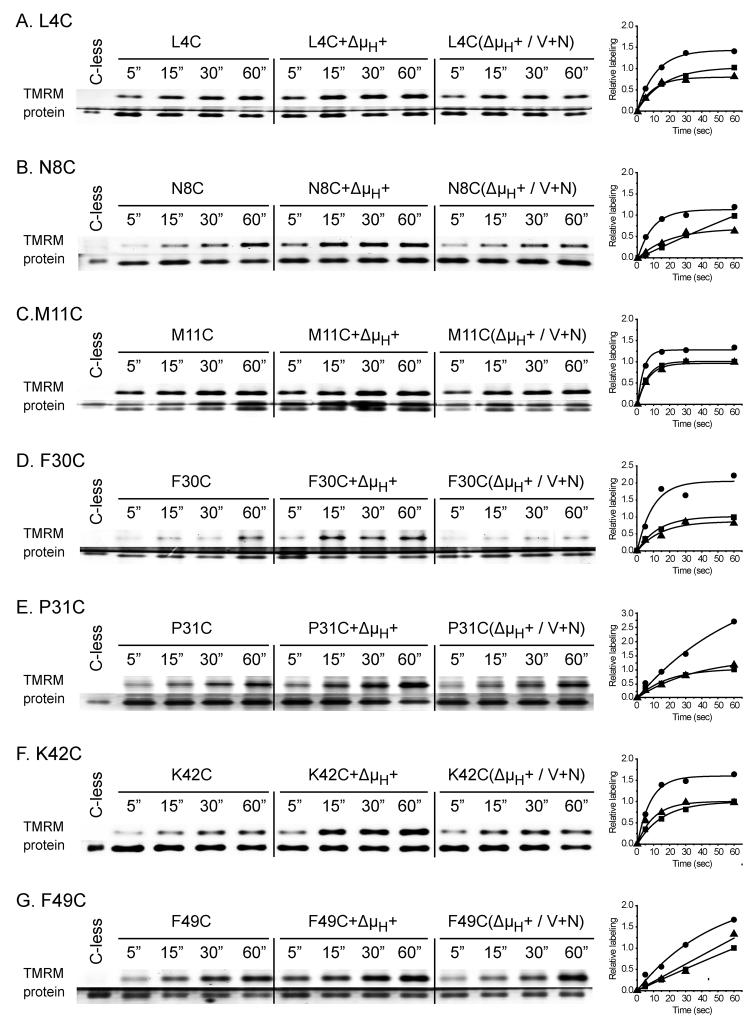

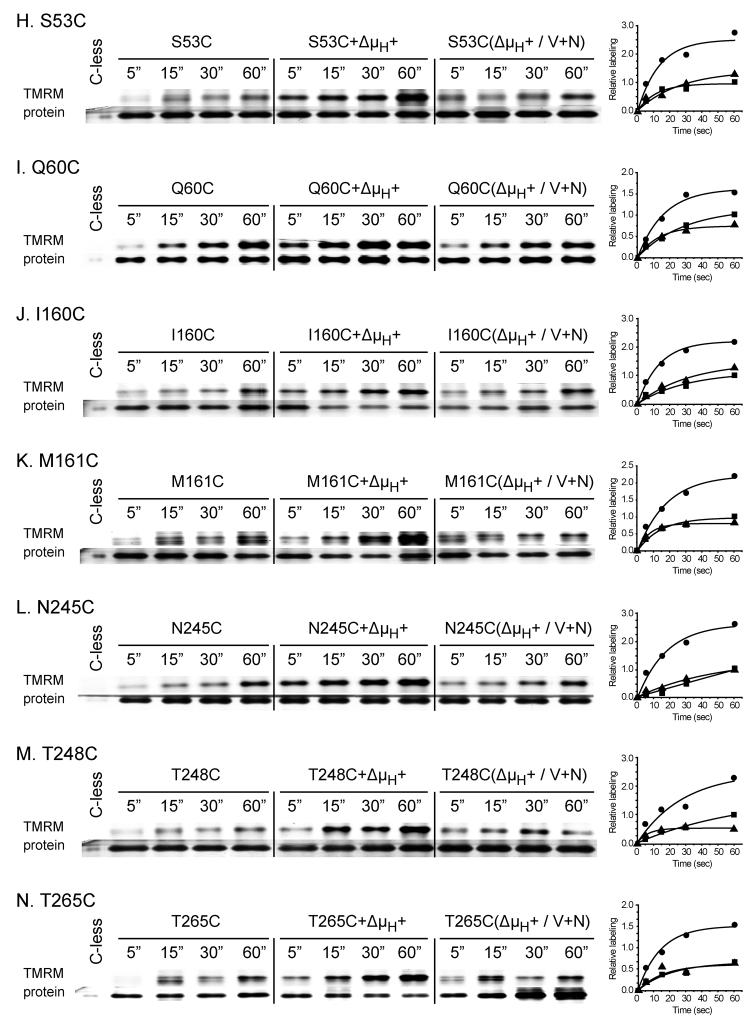

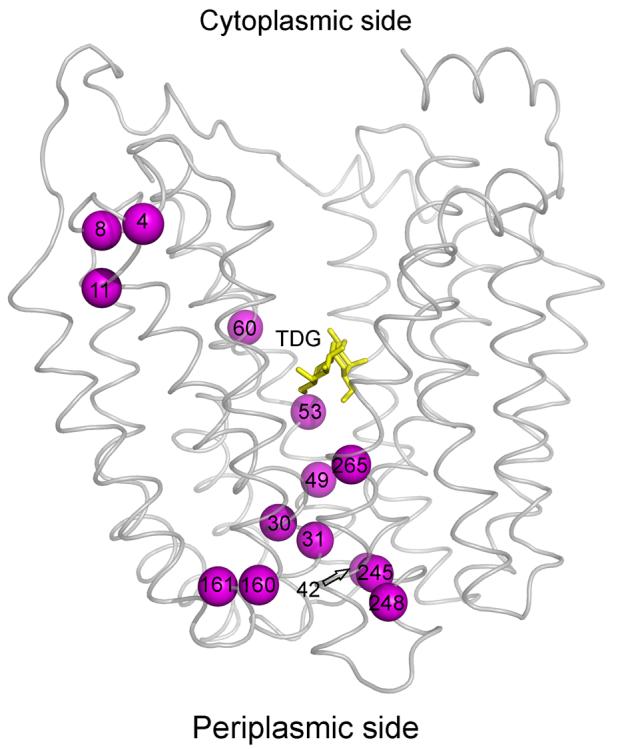

In order to study the effect of Δμ̄H + (interior negative and/or alkaline), RSO vesicles were incubated with ascorbate and phenazine methosulfate (PMS) under oxygen prior to addition of TMRM 31-33. As a negative control, valinomycin and nigericin were added to abolish Δμ̄H +. For each experiment (Fig. 4A-N), samples were labeled for given periods of time, and the reactions were terminated by addition of excess dithiothreitol (DTT). As shown, Δμ̄H + significantly increases TMRM labeling of each mutant (Fig. 4; Table 1), and valinomycin and nigericin abolishes the effect. However, it is apparent that the rates of labeling are very likely underestimated because the TMRM concentration rapidly decreases due to reaction with the plethora of proteins other than LacY in RSO membrane vesicles. In any case, Δμ̄H + increases labeling of fourteen out of the seventy-one single-Cys mutants by at least 1.3- to 7.9-fold (Fig. 4; Table 1): L4C, N8C, M11C, F30C and P31C (helix I); K42C, F49C, S53C and Q60C (helix II); I160C and M161C (helix V), N245C and T248C (helix VII); and T265C (helix VIII), and no significant effect is observed with the other fifty-seven mutants studied (data not shown). Since ten of the mutants that exhibit increased reactivity with Δμ̄H + are located on the periplasmic side of the sugar-binding site (Fig. 5), the findings suggest that Δμ̄H + increases the open probability of LacY on the periplasmic side. Notably, relative to sugar-induced changes in reactivity, Δμ̄H + induced changes are fewer and more restricted to the periplasmic side of LacY (compare Figs. 3 & 5). Furthermore, none of the mutants tested exhibits decreased reactivity in the presence of Δμ̄H +.

Figure 4.

Effect of Δμ̄H + on time-course of TMRM labeling. RSO membrane vesicles (0.1 mg of protein in 50 μl) prepared from E. coli with given single-Cys replacements, L4C (A), N8C (B), M11C (C), F30C (D), P31C (E), K42C (F), F49C (G) S53C (H), Q60C (I), I160C (J), M161C (K), N245C (L), T248C (M) and T265C (N), were incubated for 5, 15, 30, and 60 sec at 25 °C with 40 μM TMRM alone (control), in the presence of 20 mM sodium ascorbate and 0.2 mM PMS under oxygen (+Δμ̄H +) or in the presence of 250 μM valinomycin and 0.5 μM nigericin to abolish Δμ̄H + (Δμ̄H + / V+N). After terminating the reactions with DTT at the indicated time, the samples were treated as described in Fig. 2 and in Materials and Methods. The data calculated according to eq. 1 are presented as labeling relative to the amount measured at 60 sec in the absence of Δμ̄H + for each mutant. Each data set was fit into eq 2. RSO membrane vesicles with C-less LacY containing the biotin acceptor domain were incubated with 40 μM TMRM for 15 min at 25 °C and biotinylated C-less LacY was purified and loaded into the first lane of each gel, as a negative control. ■, no additions; ●, plus ascorbate/PMS; ▲, plus ascorbate/PMS, valinomycin and nigericin.

Table 1.

Δμ̄H + increases the rate of TMRM labeling of single-Cys mutants.

| Residue | Helix | Fold of Increase in TMRM labeling (+Δμ̄H +/control)* |

|---|---|---|

| L4C | I | 1.9 |

| N8C | I | 5.5 |

| M11C | I | 1.8 |

| F30C | I | 2.6 |

| P31C | I | 1.3 |

| K42C | II | 2.7 |

| F49C | II | 2.7 |

| S53C | II | 2.3 |

| Q60C | II | 2.4 |

| I160C | V | 4.1 |

| M161C | V | 1.9 |

| N245C | VII | 7.9 |

| T248C | VII | 3.4 |

| T265C | VIII | 3.2 |

Relative TMRM labeling of mutants treated for various times was calculated according to eq 1. Each data set was fit using eq 2. The initial linear portion (within 5 sec) of the fitted data was used to estimate the initial rate of TMRM labeling. For each mutant, ratio of the estimated initial rate of TMRM labeling in presence of Δμ̄H + relxative to that observed in the absence of ascorbate/PMS or after addition of valinomycin and nigericin for each mutant was then calculated (see Materials and Methods).

Figure 5.

Effect of Δμ̄H + on TMRM reactivity of single-Cys mutants. Positions of single- Cys mutants that exhibit increased TMRM reactivity are superimposed on the backbone of LacY viewed perpendicular to the membrane. TDG is shown as a stick model at the apex of the inward-facing cavity (yellow sticks). The Cys replacements that exhibit Δμ̄H + -induced increases in TMRM reactivity are L4C, N8C, M11C, F30C, P31C, K42C, F49C, S53C, Q60C, I160C, M161C, N245C, T248C and T265C (magenta spheres).

Discussion

TMRM labeling

Site-directed alkylation studies of single-Cys LacY mutants with NEM in RSO membrane vesicles have extended over a decade (see 28). Although qualitative, the studies reveal both static and dynamic aspects of LacY particularly with respect to changes induced by sugar binding. When considered in light of the X-ray structures of LacY 4; 5; 7, the observations support a model in which the sugar-binding site is alternatively accessible to either side of the membrane due to opening of a pathway on the periplasmic side of LacY and closing of the large cytoplasmic cavity. In this communication, we describe a more sensitive, simpler and less time consuming method utilizing TMRM fluorescence and use the method to examine the effect of Δμ̄H + on reactivity of single-Cys LacY mutants.

Fluorescent alkylation reagents, such as fluorescein 5-maleimide and Oregon Green maleimide, have been utilized to modify single-Cys mutants in many membrane proteins in order to study the membrane topology and the accessibility 34-38. TMRM is a highly sensitive probe, and a protocol was developed based on NEM labeling 22. TMRM labeling has several advantages relative to NEM labeling: (i) The fluorophore is very sensitive due to the high quantum yield of rhodamine. Furthermore, sensitivity can be enhanced even further by fine-tuning the voltage setting of the photomultiplier tube on the imager (see Materials and Methods) to visualize low levels of fluorescence. The new method is at least 10-times more sensitive than NEM labeling. (ii) It takes less than 8 hours to obtain data, as opposed to 24 hours or more with NEM labeling. The major time-saving step is capture of fluorescence directly from wet acrylamide gels without waiting, compared to the 2 h required to dry SDS-PAGE gels, followed by exposure to a PhosphorImager screen for up to several days before scanning with NEM labeling. (iii) Less time and effort are expended to quantify protein. With NEM labeling, two gels are needed; one for detecting radioactive bands and the other for quantifying protein by Western blot. With TMRM labeling, the same gel is used to obtain both sets of data. (iv) Use of radioactive materials is precluded. Utilizing this method, the effect of TDG on the TMRM reactivity of seventy-one single-Cys replacements were first examined, and a pattern almost identical to that observed with NEM 28 is observed (Fig. 3).

Effect of Δμ̄H +

Generation of Δμ̄H + clearly increases the reactivity of fourteen of the seventy-one single-Cys mutants tested by a factor of at least 1.3 to 7.9 (Table 1; Figs. 4 and 5). Furthermore, ten of the fourteen mutants [F30C, P31C, K42C, F49C, S53C, I160C, M161C, N245C, T248C and T265C (Fig. 5)] are on the periplasmic side of LacY and these mutants also exhibit increased reactivity upon TDG binding (compare Figs. 3 & 5). Therefore, like sugar binding, Δμ̄H + appears to increase the open probability of LacY on the periplasmic surface of the membrane, a conclusion supported by studies with the affinity inactivator methanethiosulfonyl galactose 39. However, the changes observed upon generation of Δμ̄H + are fewer and less widely distributed compared to the sugar-induced changes (Figs. 3 and 5). Moreover, none of the mutants exhibits decreased reactivity upon generation of Δμ̄H + , and no further change in reactivity is observed when Δμ̄H + is generated in the presence of a saturating concentration of TDG (data not shown).

Previous studies demonstrate that Δμ̄H + has no effect on equilibrium exchange, counterflow 40; 41 or sugar-binding affinity from either side of the membrane 42. Also, mutations in Glu325 43; 44 or Arg302 45 abolish all H+-coupled translocation reactions (active transport, downhill influx or efflux) with no effect on equilibrium exchange, counterflow or sugar binding. Taking the findings presented here in conjunction with other evidence that sugar binding induces widespread conformational changes 2; 28; 29, it seems likely that the primary driving force for the global conformational change is sugar binding and dissociation on either side of the membrane.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Tetramethylrhodamine-5-maleimide (TMRM, T-6027) was obtained from Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). Valinomycin (V0627) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and nigericin (Cat# 481990) was obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). ImmunoPure immobilized monomeric avidin (Cat # 20228) was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL). All other materials were reagent grade and obtained from commercial sources.

Plasmid construction

Given mutants were from the library of single-Cys LacY mutants encoded by plasmids pT7-5 or pKR35 15; 20-28; 46. For single-Cys replacements at positions 14, 45, 49, 60, 100, 141, 308, 361, 362, 363 or 364, DNA fragments encoding a given mutant were isolated and inserted by restriction fragment replacement into pT7-5 encoding C-less LacY with a biotin acceptor domain (BAD) from a Klebsiella pneumoniae oxaloacetate decarboxylase at the C terminus.

Growth of bacteria

E. coli T184 (lacY−Z−) transformed with plasmid pT7-5 or pKR35 encoding a given mutant was grown aerobically at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Fully grown cultures were diluted 10-fold and grown for 2 hours. After induction with 1 mM isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 2 h, cells were harvested and used for the preparation of RSO membrane vesicles.

Preparation of RSO membrane vesicles

RSO membrane vesicles containing single-Cys replacements of C-less LacY at position 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12, 15, 21, 22, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34, 42, 44, 70, 71, 81, 84, 86, 87, 88 or 96, were prepared earlier 15. RSO membrane vesicles from other mutants were prepared form 1 L cultures of E. coli T184 expressing a given mutant by lysozyme-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid treatment and osmotic lysis 47; 48. The vesicles were resuspended to a protein concentration of 10-20 mg/ml in 100 mM potassium phosphate (KPi; pH 7.5) containing 10 mM MgSO4, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

TMRM labeling

TMRM was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and the concentration determined by measuring absorbance in methanol at 541 nm (extinction coefficient, 95,000 cm−1 M−1). RSO membrane vesicles [0.1 mg of total protein in 50 μl of 100 mM KPi (pH 7.5)/10 mM MgSO4] containing a given single-Cys mutant were incubated with 40 μM TMRM in the absence or presence of 10 mM TDG at 25°C. Where indicated, Δμ̄H + was generated by adding 20 mM potassium ascorbate and 0.2 mM PMS under oxygen 31. In order to abolish Δμ̄H +, 250 μM valinomycin and 0.5 μM nigericin were added prior to ascorbate and PMS 32; 33; 49. Reactions were terminated at the indicated time by adding 10 mM DTT. The membranes were then solubilized in 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.5)/2% n-dodecyl β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM). Immobilized monomeric avidin sepharose was equilibrated in column buffer [50 mM NaPi (pH 7.5)/100 mM NaCl/0.02% DDM] and resuspended in the same buffer to 5% (vol/vol). To each reaction, 50 μl of 5% (vol/vol) avidin sepharose was added, and the mixture was incubated at 25°C for 10 min on a rotating platform, centrifuged briefly and loaded onto Wizard columns (Promega, Madison, WI) on a vacuum manifold. The avidin sepharose on the column was washed with 3 ml of column buffer, and biotinylated LacY was eluted with 25 μl of column buffer containing 5 mM D-biotin.

The samples were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). To each sample, 25 μl of 2 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added and 10 μl of each sample was loaded onto 16% SDS-PAGE. The loading volume varied from 5-40 μl depending on the level of labeling with each single-Cys mutant. Purified C-less LacY protein was loaded into the first lane of each gel, as a negative control. The gels were run for 1 hr at 60 V followed by 1 hr at 120 V. The wet gels sandwiched between the glass plates were then imaged directly on an Amersham Typhoon™ 9410 Workstation (Amersham/GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The Cy3 laser setting (excitation at 532 nm) with a 580 nm filter (emission wavelength) were used to capture the rhodamine image and the photomultiplier tube setting was adjusted manually to obtain the best signals. The SDS-PAGE gels were then silver-stained and scanned.

The TMRM signal and amount of protein were estimated by measuring the density of each band by using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, GE Healthcare BioSciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ). TMRM labeling at 60 sec in the absence of Δμ̄H + (control) for each mutant was estimated by dividing the density of the protein band with TMRM signal, which was then normalized to 1 (Equation 1).

| (1) |

Relative TMRM labeling of mutants treated for given times was calculated according to Equation 1. Each data set was fit using equation 2,

| (2) |

The initial linear portion (within 5 sec) of the fitted data was used to qualitatively estimate the initial rate of TMRM labeling. For each mutant, the ratio of the estimated initial rate of TMRM labeling in presence of Δμ̄H + relative to that observed in the absence of ascorbate/PMS or after addition of valinomycin and nigericin for each mutant was then approximated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lan Guan, Vladimir Kasho, Shushi Nagamori and Irina Smirnova for advice and discussion. In addition, we thank Junichi Sugihara for help with growth of bacteria and all the members of the laboratory for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported in part by NIH Grants DK51131, DK06946 and 1 U54 GM074929, 1 P50 GM073210 and NSF grant 0450970 to HRK.

∥Abbreviations

- LacY

lactose permease

- RSO

right-side-out

- TDG

β-d-galactopyranosyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- TMRM

tetramethylrhodamine-5-maleimide

- IPTG

isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- DDM

n-dodecyl β-d-maltopyranoside

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Kaback HR. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease. C R Biol. 2005;328:557–67. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan L, Kaback HR. Lessons from Lactose Permease. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:67–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viitanen P, Newman MJ, Foster DL, Wilson TH, Kaback HR. Purification, reconstitution, and characterization of the lac permease of Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1986;125:429–452. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)25034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramson J, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Verner G, Kaback HR, Iwata S. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science. 2003;301:610–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1088196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirza O, Guan L, Verner G, Iwata S, Kaback HR. Structural evidence for induced fit and a mechanism for sugar/H(+) symport in LacY. Embo J. 2006;25:1177–1183. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan L, Smirnova IN, Verner G, Nagamoni S, Kaback HR. Manipulating phospholipids for crystallization of a membrane transport protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1723–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510922103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan L, Mirza O, Verner G, Iwata S, Kaback HR. Structural determination of wild-type lactose permease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707688104. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Iwaarden PR, Driessen AJ, Menick DR, Kaback HR, Konings WN. Characterization of purified, reconstituted site-directed cysteine mutants of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15688–15692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frillingos S, Kaback HR. Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis of helix VI and the flanking hydrophilic domains in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5333–5338. doi: 10.1021/bi953068d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunten RL, Sahin-Toth M, Kaback HR. Cysteine scanning mutagenesis of putative helix XI in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12644–50. doi: 10.1021/bi00210a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frillingos S, Ujwal ML, Sun J, Kaback HR. The role of helix VIII in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. I. Cys-scanning mutagenesis. Protein Sci. 1997;6:431–437. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voss J, Hubbell WL, Hernandez J, Kaback HR. Site-directed spin-labeling of transmembrane domain VII and the 4B1 antibody epitope in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15055–15061. doi: 10.1021/bi971726j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voss J, Sun J, Kaback HR. Sulfhydryl oxidation of mutants with cysteine in place of acidic residues in the lactose permease. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8191–8196. doi: 10.1021/bi9802667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao M, Zen K-C, Hernandez-Borrell J, Altenbach C, Hubbell WL, Kaback HR. Nitroxide scanning electron paramagnetic resonance of helices IV, V and the intervening loop in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15970–15977. doi: 10.1021/bi991754x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ermolova N, Madhvani RV, Kaback HR. Site-directed alkylation of cysteine replacements in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli: helices I, III, VI, and XI. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4182–9. doi: 10.1021/bi052631h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorgen PL, Hu Y, Guan L, Kaback HR, Girvin ME. An approach to membrane protein structure without crystals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14037–14040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182552199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun J, Kaback HR. Proximity of periplasmic loops in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli determined by site-directed cross-linking. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11959–65. doi: 10.1021/bi971172k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J, Kaback HR. Helix proximity and ligand-induced conformational changes in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli determined by site-directed chemical crosslinking. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:285–293. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu J, Voss J, Hubbell WL, Kaback HR. Site-directed spin labeling and chemical crosslinking demonstrate that helix V is close to helices VII and VIII in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10123–10127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J, Frillingos S, Voss J, Kaback HR. Ligand-induced conformational changes in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli: evidence for two binding sites. Protein Sci. 1994;3:2294–301. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frillingos S, Kaback HR. The role of helix VIII in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. II. Site-directed sulfhydryl modification. Protein Sci. 1997;6:438–443. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frillingos S, Kaback HR. Probing the conformation of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli by in situ site-directed sulfhydryl modification. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3950–3956. doi: 10.1021/bi952601m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkatesan P, Hu Y, Kaback HR. Site-directed sulfhydryl labeling of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli: helix X. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10656–10661. doi: 10.1021/bi0004403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatesan P, Kwaw I, Hu Y, Kaback HR. Site-directed sulfhydryl labeling of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli: helix VII. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10641–10648. doi: 10.1021/bi000438b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venkatesan P, Liu Z, Hu Y, Kaback HR. Site-directed sulfhydryl labeling of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli: helix II. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10649–10655. doi: 10.1021/bi0004394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwaw I, Zen KC, Hu Y, Kaback HR. Site-directed sulfhydryl labeling of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli: helices IV and V that contain the major determinants for substrate binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10491–9. doi: 10.1021/bi010866x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Hu Y, Kaback HR. Site-directed sulfhydryl labeling of helix IX in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4904–8. doi: 10.1021/bi034078e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaback HR, Dunten R, Frillingos S, Venkatesan P, Kwaw I, Zhang W, Ermolova N. Site-directed alkylation and the alternating access model for LacY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:491–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609968104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majumdar DS, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Nir E, Kong X, Weiss S, Kaback HR. Single-molecule FRET reveals sugar-induced conformational dynamics in LacY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12640–12645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700969104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan L, Kaback HR. Site-directed alkylation of cysteines to test solvent accessibility. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:2012–2017. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konings WN, Barnes EM, Jr., Kaback HR. Mechanisms of active transport in isolated membrane vesicles. 2. The coupling of reduced phenazine methosulfate to the concentrative uptake of β-galactosides and amino acids. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:5857–5861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramos S, Schuldiner S, Kaback HR. The electrochemical gradient of protons and its relationship to active transport in Escherichia coli membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:1892–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.6.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos S, Kaback HR. The electrochemical proton gradient in Escherichia coli membrane vesicles. Biochemistry. 1977;16:848–54. doi: 10.1021/bi00624a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falke JJ, Sternberg DE, Koshland DE. Site-directed sulfhydryl chemistry and spectroscopy: Applications in the aspartate receptor system. Biophys. J. 1986;49:20a. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Culham DE, Hillar A, Henderson J, Ly A, Vernikovska YI, Racher KI, Boggs JM, Wood JM. Creation of a fully functional cysteine-less variant of osmosensor and proton-osmoprotectant symporter ProP from Escherichia coli and its application to assess the transporter's membrane orientation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11815–23. doi: 10.1021/bi034939j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu D, Maloney PC. Structure-function relationships in OxlT, the oxalate/formate transporter of Oxalobacter formigenes. Topological features of transmembrane helix 11 as visualized by site-directed fluorescent labeling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17962–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poelarends GJ, Konings WN. The transmembrane domains of the ABC multidrug transporter LmrA form a cytoplasmic exposed, aqueous chamber within the membrane. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42891–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou J, Fazzio RT, Blair DF. Membrane topology of the MotA protein of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:237–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan L, Sahin-Toth M, Kalai T, Hideg K, Kaback HR. Probing the mechanism of a membrane transport protein with affinity inactivators. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10641–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaczorowski GJ, Robertson DE, Kaback HR. Mechanism of lactose translocation in membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli. 2. Effect of imposed delta psi, delta pH, and delta mu H+ Biochemistry. 1979;18:3697–3704. doi: 10.1021/bi00584a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia ML, Viitanen P, Foster DL, Kaback HR. Mechanism of lactose translocation in proteoliposomes reconstituted with lac carrier protein purified from Escherichia coli. 1. Effect of pH and imposed membrane potential on efflux, exchange, and counterflow. Biochemistry. 1983;22:2524–2531. doi: 10.1021/bi00279a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guan L, Kaback HR. Binding affinity of lactose permease is not altered by the H+ electrochemical gradient. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12148–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404936101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carrasco N, Antes LM, Poonian MS, Kaback HR. Lac permease of Escherichia coli: histidine-322 and glutamic acid-325 may be components of a charge-relay system. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4486–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00364a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carrasco N, Puttner IB, Antes LM, Lee JA, Larigan JD, Lolkema JS, Roepe PD, Kaback HR. Characterization of site-directed mutants in the lac permease of Escherichia coli. 2. Glutamate-325 replacements. Biochemistry. 1989;28:2533–9. doi: 10.1021/bi00432a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sahin-Tóth M, Kaback HR. Arg-302 facilitates deprotonation of Glu-325 in the transport mechanism of the lactose permease from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111139698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Consler TG, Persson BL, Jung H, Zen KH, Jung K, Prive GG, Verner GE, Kaback HR. Properties and purification of an active biotinylated lactose permease from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6934–6938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Short SA, Kaback HR, Kohn LD. Localization of D-lactate dehydrogenase in native and reconstituted Escherichia coli membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4291–4296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaback HR. Bacterial Membranes. In: Kaplan NP, Jakoby WB, Colowick NP, editors. Methods in Enzymol. XXII. Elsevier; New York: 1971. pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramos S, Kaback HR. The electrochemical proton gradient in Escherichia coli membrane vesicles and its relationship to active transport. Biochem Soc Trans. 1977;5:23–5. doi: 10.1042/bst0050023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]