Abstract

Our laboratory has characterized spatial patterns of evoked neural activity across the entire glomerular layer of the rat olfactory bulb using primarily aliphatic odorants that differ systematically in functional groups and hydrocarbon structures. To represent more fully the true range of odorant chemistry, we have investigated aromatic compounds, which have a more rigid molecular structure than most aliphatic compounds and are particularly salient olfactory stimuli for humans. We first investigated glomerular patterns of 2-deoxyglucose uptake in response to aromatic compounds that differ in the nature and position of their functional groups (e.g., xylenes, trimethylbenzenes, tolualdehydes, benzaldehydes, methyl toluates, and anisaldehydes). We also studied the effects of systematic increases in the number and length of alkyl substituents. We found that most aromatic compounds activated glomeruli in the dorsal part of the bulb. Within this general area, aromatic odorants with oxygen-containing substituents favored activation of more rostral regions, and aromatic hydrocarbons activated more posterior regions. The nature of substituents greatly affected the pattern of glomerular activation, whereas isomers differing in substitution position evoked very similar overall patterns. These relationships between the structure of aromatic compounds and their spatial representation in the bulb are contrasted with our previous findings with aliphatic odorants.

Indexing terms: 2-deoxyglucose, odors, imaging techniques

There are approximately 1,000 types of olfactory receptors that initially bind to odorants (Buck and Axel, 1991). Each receptor gene is expressed in several thousand homologous receptor neurons that sort their axons and converge onto as few as one or two glomeruli in the olfactory bulb (Ressler et al., 1994; Vassar et al., 1994; Mombaerts et al., 1996). This massive convergence of homologous sensory neuron axons onto single glomeruli, which likely sorts odorant information encoded by the receptors, makes the olfactory bulb an ideal focus for the study of olfactory processing.

Our research has involved mapping glomerular activity over the entire olfactory bulb in response to odorants differing incrementally in chemical structure, with the goal of characterizing chemotopic representations (i.e., systematic relationships between spatial activity patterns and odorant chemical structure) (Leon and Johnson, 2003). Specific clusters of glomeruli respond to a range of odorant molecules sharing a chemical feature such as functional group (Johnson et al., 1998, 2002, 2004; Johnson and Leon, 2000a), and the overall pattern of activity across the olfactory bulb overlaps for odorants within a series that have a similar carbon number (Johnson et al., 1998, 2004, 2005a; Johnson and Leon, 2000b). In addition to a global chemotopic organization, there appears to be a local organization of glomerular activity for representation of subtle differences in odorant structures (Johnson et al., 1999, 2004; Johnson and Leon, 2000b; Uchida et al., 2000). The relative activity of nearby glomeruli is systematically affected by minor changes in odorant chemistry, resulting in shifts in the centroids of activity within various local regions in relation to carbon number or molecular length (Johnson et al., 1999, 2004; Johnson and Leon, 2000b). This shift in activity within a group of nearby glomeruli, which we refer to as local chemotopic organization, appears to be an important aspect of coding for straight-chained odorants with different carbon numbers (Johnson et al., 2004).

Aromatic compounds are particularly salient stimuli in human olfaction, as evidenced by their presence in spices, their use in perfume, food, and wine flavoring, and also as non-desirable components of livestock waste, industrials waste, gasoline, paint, and industrial pollutants (Hitchman et al., 1995; Daniel et al., 1999; Miller, 2001). Aromatic compounds have a more rigid molecular structure than most aliphatic compounds, and they would be expected to present their molecular features in a fixed spatial relationship to odorant receptors. Aromatic rings also provide the opportunity for pi stacking between odorant ligands and aromatic side chains in receptor proteins (Meyer et al., 2003). These distinct chemical features of aromatic odorants might be associated with the use of unique coding strategies by the olfactory system. For the present study, we selected sets of aromatic odorants that contained a benzene ring and that differed systematically in their attached functional groups, as well as in their stereochemistry. We were particularly interested in comparing the structural factors most affecting the glomerular activation patterns to the factors that had proven important in our past studies on aliphatic odorants. In these experiments, we determined glomerular activation patterns using our 2-DG uptake technique (Johnson et al., 1999) because it provides a global view of activation patterns in the entire olfactory bulb of a behaving rat and because it allows the use of statistical tools for quantitative analysis of activation patterns across multiple animals in a manner that is not feasible through the use of other mapping techniques (Katoh et al., 1993, Uchida et al., 2000, Wachowiak and Cohen 2001, Takahashi et al., 2004).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Odorants

Odorants are listed in Table 1, which includes unique Chemical Abstract Services (CAS) registry numbers, conditions for exposure, numbers of animals used per odorant condition, and identification numbers to facilitate reference to the exposures throughout this study. A total of 71 odorant exposure groups are described in this report, 54 of which were derived from 7 new independent studies and 17 of which were chosen for further analysis from our previously published work. Exposures #21–24, 51, and 60 were from Johnson et al. (2002), and exposures #16, 55–57, 62, 64–68 and 70 were from Johnson et al. (2005b). Odorants were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Tustin, CA), Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and TCI (Portland, OR). All odorants had a listed purity of greater than 97%. Liquid odorants were used neat, and for exposures to these odorants, air served as the vehicle blank. Solid odorants were dissolved in a solvent (mineral oil or ethanol), and for exposures to these odorants, the solvent served as the vehicle blank. For neat odorants or odorants dissolved in ethanol, 100 ml of odorants were used in a 125-ml gas-washing bottle, while for odorants dissolved in mineral oil, 200 ml were used in a 500-ml gas-washing bottle. All gas-washing bottles were fitted with a stopper assembly possessing an extra-coarse porosity diffuser.

Odorant exposures

Neat odorants were volatilized by passing high-purity nitrogen gas through a column of liquid odorant in a gas-washing bottle at a flow rate of 250 ml/minute. Flow rates of odorant vapors were regulated with a Gilmont flowmeter. To achieve a desired dilution, volatilized odorants were mixed with ultra-zero grade air, which entered the exposure chamber at a final flow rate of 2 liters/minute. For odorants diluted in mineral oil, we used a nitrogen flow rate of 100 ml/minute, and the resulting vapor was diluted 1/10 in ultra-zero air before reaching the exposure chamber at a final flow rate of 1 liter/minute. The final vapor-phase concentration for each odorant (Table 1) was determined from the mode of vapor-pressure data obtained from the following sources: PhysProp Database at Syracuse Research Corporation (http://www.syrres.com/esc/physdemo.htm), the Chemical and Physical Properties Database from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (http://www.dep.state.pa.us/physicalproperties/CPP_Search.htm), Molecular Modeling Pro version 3.14 (ChemSW, Fairfield, CA), and ChemDraw Ultra version 6.0 (CambridgeSoft, Cambridge, MA).

Rats (postnatal days 17–19) were placed in clean cages together with their dams a minimum of one hour prior to experimental testing in order to diminish the effects of carryover of odors from soiled bedding into the odorant exposure chamber. The number of male and female rats tested was balanced across different odorant conditions. Immediately prior to exposure, each rat received a subcutaneous injection of [14C]2-DG (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO; 0.16 mCi/kg) and placed in a 2-liter glass Mason jar. The awake, behaving rat was then exposed for 45 minutes to an odorant or control vapor, which entered the jar trough a lid fitted with a vent. Clean tubing and exposure chambers were used for each tested odorant to eliminate carryover effects. After exposure, the rat was decapitated and its brain removed and frozen at −45 °C in isopentane. All procedures involving animals were approved by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Activity mapping

Olfactory bulbs were sectioned, and their 2-DG uptake was mapped as previously described by Johnson et al. (1999, 2004). Briefly, regularly spaced 20-μm sections in the coronal plane were taken for autoradiography using a cryostat. Anatomical landmarks were located using images of alternate, cresyl violet-stained sections. These sections were also used to direct measurements from the glomerular layer of the autoradiograph section. Measurements were obtained at the intersection of the glomerular layer and each gridline of a polar grid selected for each section on the basis of its relative rostral-caudal location in the bulb.

To normalize for differences in bulb size, individual sections were merged into standardized matrices with respect to anatomical landmarks, and matrices for left and right bulbs were averaged for each rat. After subtraction of a vehicle blank, each data matrix was converted to z-score units based on the mean and standard deviation of the data matrix. These z-score matrices were then averaged for a given odorant condition for plotting standardized activity patterns. Spatial distributions of activity patterns represented by the averaged z-score matrices were plotted as color-coded contour charts using Microsoft Excel. Ventral-centered two-dimensional charts are provided as supplementary figures through the online version of the Journal, as well as through our website (http://leonserver.bio.uci.edu), which also displays three-dimensional rotatable reconstructions of the patterns.

We used individual z-score patterns instead of averages, to test for significant differences among odorant-induced responses within each independently conducted study. We performed two types of tests to establish whether patterns differed significantly in the study. In the first type of test, we used Pearson correlation and principal components analysis (StatView®, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We calculated the overall similarity of the patterns for every pair of odorant-exposed animals in the study by calculating a correlation coefficient based on over 2300 pairs of matched points across the two patterns (Johnson et al., 2002; 2004, 2005 a, b). A half-diagonal matrix of these correlation coefficients was then used as input data for principal components analysis. In this analysis, we were interested in whether animals exposed to the same odorant would be more tightly clustered than animals exposed to different odorants in the same study. To determine the statistical significance of this clustering, we performed ANOVA with respect to the odorant condition on each of the first two un-rotated factors extracted by the principal components analysis. Given significant results in the overall ANOVA, we considered the results of post-hoc Fisher PLSD tests to further describe the differences in evoked patterns between different individual odorants.

In our second statistical analysis, we calculated the average 2-DG uptake across 30 previously defined regions (i.e., response modules) of the glomerular layer followed by ANOVA and FDR correction for the multiple comparisons (Johnson et al., 2004, 2005a,b). This analysis not only can reveal significant differences across the odorants, but it also can reveal candidate spatial locations responsible for these differences. It is important to note that the 30 modules used in this analysis were selected from prior experiments as an analytical tool and do not necessarily correspond to glomerular clusters observed in the present study. The use of these modules simplifies the data for statistical analysis and provides a standard of comparison to the prior studies in which we used the same approach. Significant differences in this type of analysis also do not represent a validation of the modules as they were discussed in our previous experiments.

For studies where we suspected that changes in odorant chemistry might be associated with local shifts in activity, we analyzed centroids of activity within outlined glomerular regions in a manner similar to that used in our previous studies (Johnson et al., 1998, 1999, 2004, 2005b; Johnson and Leon, 2000b). To specify the regions for analysis, we calculated grand averages of dorsal-centered z-score matrices involving all of the odorants in the particular study. We then selected contiguous cells that exceeded a value of 0.5 in the areas of interest. The resulting regions then were adjusted slightly to smooth out any invaginations. To determine if a significant change in the location of glomerular activation had occurred, the coordinates of the centroids were subjected to an ANOVA test.

RESULTS

To study the spatial organization of the olfactory bulb response to aromatic compounds, we exposed 71 groups of rats to 48 distinct odorants that differed in the nature and position of their functional groups (Table 1). The present study was composed of several independently conducted experiments, each having a set of independent experimental parameters (e.g., vehicle blank and vapor-phase concentration), and each using a split-litter design. The results from each experiment will be described initially, followed by a general analysis of the tendencies observed across experiments. Because nearly all aromatic compounds used in the present study activated glomeruli in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial parts of the posterior bulb, all patterns of glomerular activity will be presented here as dorsal-centered charts instead of the ventral-centered format we have used in our prior publications. For reference, ventral-centered charts, as well as rotatable three-dimensional models of these activity patterns, are available on our website at http://leonlab.bio.uci.edu/.

Activity patterns evoked by aromatic hydrocarbons and aromatic aldehydes differ from corresponding aliphatic odorants

In our first experiment, we investigated the effects of systematically changing the position of the functional group, as well as changing the number of methyl group substituents on two different classes of aromatic compounds, hydrocarbons and aldehydes. Results from this experiment are shown in Figure 1. Panel A of this figure shows patterns of activity for aromatic hydrocarbons as a function of the number and position of carbons. Panel B shows results for aromatic aldehydes and methyl benzoate. The ventral activity that is typical of aliphatic compounds greater than five carbons in length (Johnson and Leon, 2000a; Johnson et al., 2002, 2004; Ho et al., 2005) was largely absent from these patterns evoked by aromatic compounds, which instead all activated more dorsal regions. Furthermore, by virtue of containing acid contaminants by way of oxidation, aliphatic aldehydes typically activate anterior and dorsal acid-responsive glomerular modules (Johnson and Leon, 2000a; Johnson et al., 2002, 2004), but these modules were never activated by the aromatic aldehydes.

Fig. 1.

Contour charts displaying the distribution of 2-deoxyglucose uptake across the entire glomerular layer. All patterns of glomerular activity are presented as dorsal-centered charts instead of the ventral-centered format we have used in our prior publications. Each chart shows activity averaged across both bulbs of all rats exposed to a given odorant. Relative uptake is color coded in units of z-score as shown in the key. The orientation of these contour charts with respect to olfactory bulb anatomy is shown at the right end of the second row. Odorants are identified by chemical structure and by a unique number identifying the exposure as shown in Table 1. The right panel of the first row displays the results of ANOVA tests expressing differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks. These areas help to indicate the possible spatial locations of areas activated differently by the different odorants.

While most of the activity evoked by the odorants used in this experiment was confined to the dorsolateral and dorsomedial regions of the bulb, there were certain apparent differences across these average patterns. To determine if these differences were statistically significant, we first conducted a principal components analysis on all of the individual animals’ patterns of 2DG uptake. The first two un-rotated factors extracted by this analysis are illustrated in Figure 2. Loadings on factor two were found to differ significantly across the different odorants (F14,68 = 11.26, P < 0.0001). In general, the patterns involving exposures to aromatic hydrocarbons seemed to be clustered separately from the patterns involving exposures to aromatic aldehydes and methyl benzoate. To better understand the spatial correlates of this significant change in patterns, we averaged responses across 30 previously defined glomerular modules and compared the results across different odorants by using ANOVA followed by FDR corrections. Indeed, we found that statistically significant differences between the patterns evoked by the aromatic odorants were distributed across many areas of the bulb, which is illustrated by colors and asterisks in the chart labeled “ANOVA” on the right end of the first row of charts in Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Scatter chart showing a plot of factor 1 versus factor 2 from a principal components analysis, which was conducted on a correlation matrix involving all pair-wise comparisons of activity patterns from individual animals exposed to the odorants shown in Figure 1. We performed this type of analysis as a first test for statistically significant differences between activity patterns in each of the nine independent studies contributing to this paper. We considered only the first two un-rotated factors extracted by the principal components analysis. Loadings on each of these two factors were subjected to ANOVA across the different odorant conditions to derive the significance of any differences.

Changing the number of methyl groups, but not their position, changed glomerular patterns evoked by aromatic hydrocarbons

When the subset of patterns involving exposures to aromatic hydrocarbons was analyzed by principal components analysis separately from the aromatic aldehydes, differences between odorants continued to be significant (F7,36 = 5.21, P = 0.0004). These odorants involved differences both in the number of methyl groups and in their relative position.

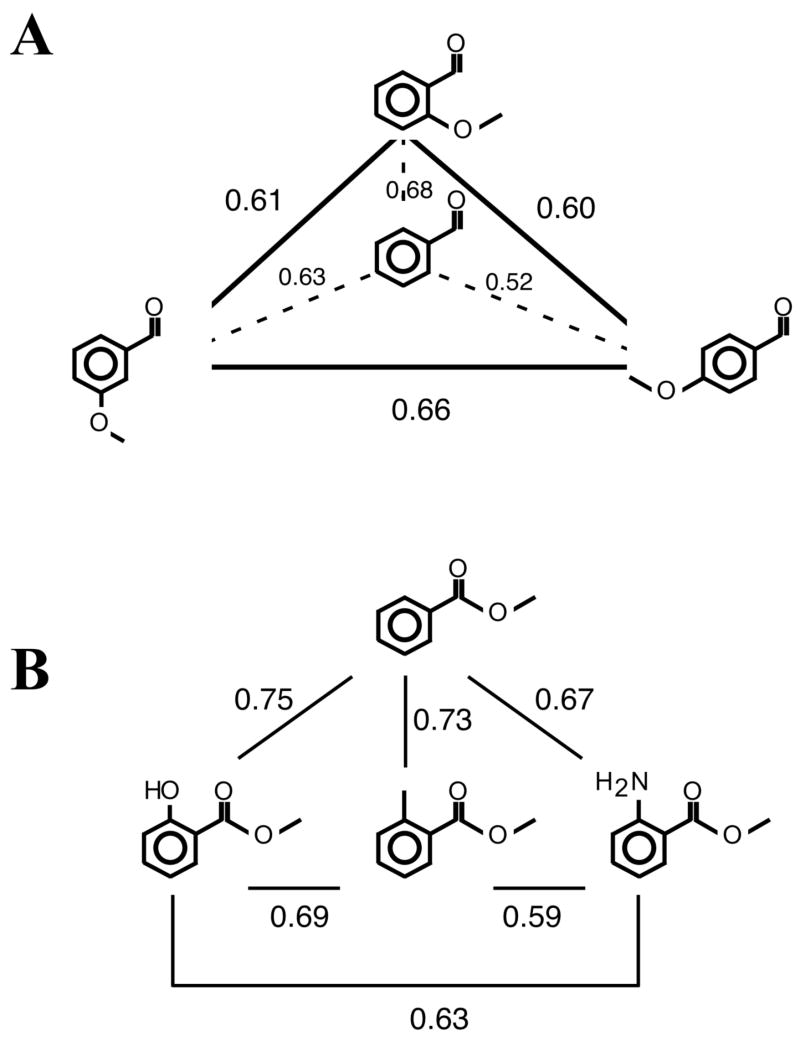

To address the specific effects of substitution position on the patterns of activity, we first considered three isomers of xylene (patterns 2, 3, and 4 in Fig. 1) and three isomers of trimethylbenzene (patterns 6, 7, and 8). Pair-wise pattern correlation coefficients calculated for the average patterns evoked by these odorants are shown in Figure 3A and 3B. The patterns of activity evoked by xylene isomers were highly correlated (average r = 0.59), as were those evoked by isomers of trimethylbenzene (average r = 0.61). These results are similar to those we obtained previously in which isomers of aliphatic ketones differing in the substitution position of the carbonyl group were found to evoke very similar patterns, and they contrast with our findings on the substitution position of a hydroxyl group in aliphatic alcohols, where isomers produced dramatically different activity patterns (Johnson et al., 2005a).

Fig. 3.

Diagram displaying the overall pattern similarity between pairs of systematically related aromatic hydrocarbons. Overall pattern similarity was determined by Pearson correlation analysis of the average activity patterns illustrated in Figure 1. A: High correlations resulted when positional isomers of xylenes (patterns 2–4 in Fig. 1) were compared. B: High correlations also were observed for positional isomers of trimethylbenzene (patterns 6–8 in Fig. 2). C: Correlations between those odorant pairs differing by one methyl group atom included lower values than did comparisons involving isomers. D: Correlations between odorants with 2 carbon-atom differences (dashed lines) and 3-carbon atom differences (straight line) had the lowest values. E: Correlation coefficients are plotted against difference in carbon number to elucidate the global chemotopic relationship between the patterns (i.e., as the difference in carbon number increases, the correlation coefficient between odorant-evoked patterns decreases).

To address the effects of increasing the number of methyl groups on aromatic compounds, we considered pattern similarities for aromatic hydrocarbons that differed by one, two, or three carbons in their chemical structures (Fig. 3C and 3D). The pair-wise correlation coefficients for compounds differing by one carbon (Fig. 3C) were high, but appeared to be somewhat more variable compared to those involving isomers (Fig. 3A and 3B). Aromatic hydrocarbons that differed by two and three carbons in their molecular structure yielded patterns that were more different than those for odorants differing by zero or one carbon (Fig. 3D). Therefore, as shown graphically in Figure 3E, as the difference in carbon number increased, the correlation coefficient between odorants decreased, suggesting a globally chemotopic organization wherein the most similar odorant chemicals evoke the most similar overall patterns. This finding is quite similar to the global chemotopy we observed in our experiments on aliphatic odorants differing in the number of carbons in a hydrocarbon backbone (Johnson et al., 1999; 2004; Ho et al., 2005).

The dissimilarity of the aromatic hydrocarbons differing by two and three carbons may have been due largely to the patterns of activity associated with toluene (pattern 1) and tetramethylbenzene (pattern 9), which appeared to differ from those for other aromatic hydrocarbons by having a more patchy distribution of lower levels of uptake (Fig. 1). In fact, post-hoc tests of differences in the principal components analysis of the aromatic hydrocarbon series suggested that 1,2,3,4-tetramethylbenzene evoked a pattern that was significantly different from every other pattern in the series, whereas toluene differed significantly from mesitylene (pattern 8) and m-xylene (pattern 3). In addition to these differences, ethylbenzene (pattern 5), another isomer of the xylenes (patterns 2, 3 and 4) that involves an ethyl group instead of two methyl groups, appeared to evoke a different pattern in that ethylbenzene activated more posterior glomeruli than did the xylenes.

The series of aromatic aldehydes also involved differences in the number and position of methyl group substituents (Fig. 1B). Principal components analysis of the aromatic aldehyde series performed separately from the aromatic hydrocarbons failed to show any significant differences across odorants in loadings on either factor 1 or 2. To explore these similarities further, we considered isomers of tolualdehydes (patterns 11, 12, and 13). Correlation coefficients between patterns evoked by these isomers were quite high (r > 0.6) with very low variability in coefficients as shown in Figure 4A. To explore the similarities in patterns evoked by aromatic aldehydes with differing carbon number, we considered patterns evoked by benzaldehyde (pattern 10), o-tolualdehyde (pattern 11), p-tolualdehyde (pattern 13), and 2,4-dimethylbenzaldehyde (pattern 14). Unlike the glomerular response patterns observed for aromatic hydrocarbons, there appeared to be little difference in the magnitude of correlation between the isomers (Fig. 4A), the aromatic aldehydes with a one-carbon difference (Fig. 4B, solid lines) and the aromatic aldehydes with a two-carbon difference (Fig. 4C, dashed line).

Fig. 4.

Diagram displaying the overall pattern similarity between pairs of systematically related aromatic aldehydes. Overall pattern similarity was determined by Pearson correlation analysis of the average activity patterns illustrated in Figure 1. A: Correlations between activity patterns evoked by positional isomers of tolualdehdyes. B: Correlations between aromatic aldehydes differing by one (solid lines) or two (dashed line) methyl groups.

Aromatic aldehydes differ from aromatic hydrocarbons in the position of responses in the dorsal region of the bulb

Although all odorants in this experiment activated the dorsolateral and dorsomedial parts of the bulb, the areas activated by oxygen-containing odorants (Fig. 1B, patterns 10–15) appeared to be positioned more rostrally than regions activated by aromatic hydrocarbons (Fig. 1A, patterns 1–9). To quantify this apparent difference, we conducted centroid analyses on the dorsolateral and dorsomedial outlined areas shown in Figure 5. There was a clear difference in the location of centroids associated with oxygen-containing substituents, which favored activation of the more dorsal and rostral regions, and aromatic hydrocarbons, which activated more posterior areas (Fig. 5). This difference was statistically significant for both the lateral (F12,60 = 2.50, p < 0.01) and the medial (F12,60 = 2.50, p < 0.01) regions.

Fig. 5.

A diagram illustrating centroid analyses in order to determine if aromatic hydrocarbons and aromatic aldehydes differed significantly in the location of activity in the dorsal regions of the bulb. Centroid analyses were conducted separately for the dorsolateral and dorsomedial regions outlined in the chart shown in the middle of the figure. The center of each ellipse indicates the mean position of the centroid in different animals exposed to a given odorant. The height of each ellipse indicates the standard error of the mean in the dorsal-ventral dimension, and the width indicates the standard error in the rostral-caudal dimension. The coordinates of the centroids differed significantly across the 15 odorants shown here in both the lateral and the medial aspect as determined by ANOVA tests. The aldehydes and methyl benzoate (open ellipses) favored activation of the more dorsal region, and the aromatic hydrocarbons (shaded ellipses) activated more posterior areas.

The effect of adding the aldehyde functional group to the benzene ring can be judged by comparing the patterns evoked by any of the tolualdehyde isomers (patterns 11–13) to the pattern evoked by toluene (pattern 1), or by comparing the pattern evoked by 2,4-dimethylbenzaldehyde (pattern 14) to that evoked by m-xylene (pattern 3). In these four comparisons, the aldehydes evoked activity that was largely separate from the region activated by the aromatic hydrocarbons (Fig. 1). This finding contrasts with the effect of adding an aldehyde functional group to an alkane odorant. Aliphatic aldehydes continue to evoke activity in the bulbar regions activated by the corresponding pure hydrocarbon (an alkane), but they additionally evoke activity in spatially segregated modules responding to other aldehydes (Johnson et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2005).

Isomers of other aromatic compounds also evoked similar activity patterns

In the next experiments, we further investigated the effects of systematic changes in stereochemistry of aromatic compounds across different ring structures and functional groups (pyrazines, aldehydes and esters). Results of these experiments are shown in Figure 6 as three independent analyses.

Fig. 6.

Contour charts indicate average activity patterns from three independent studies involving positional isomers of aromatic odorants. All patterns of glomerular activity are presented as dorsal-centered charts instead of the ventral-centered format we have used in our prior publications. A: Aromatic odorants involving methyl-substituted pyrazine rings. B: Benzaldehyde and positional isomers of anisaldehyde. C: Aromatic odorants involving a methyl ester substituent with and without other substituents. The orientation of the contour charts is the same as shown in Figure 1.

In a previous publication, we reported that 2,3-dimethylpyrazine, an aromatic odorant with two nitrogen atoms in the ring, evoked an activity pattern similar to aromatic compounds possessing a benzene ring (Johnson et al., 2005b). Here, we determined whether substitution position isomers of these nitrogen-containing aromatic odorants would evoke similar activity patterns as did the other aromatic compounds. These odorants have odors related to roasted nuts, coffee, or cocoa, and they included three dimethylpyrazine isomers (patterns 16, 17, and 18), trimethylpyrazine (19) and tetramethylpyrazine (20). Consistent with our prior observations involving 2,3-dimethylpyrazine, the major activity associated with these odorants was concentrated in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial parts of the bulb, as was the case with activity patterns for aromatic hydrocarbons and aromatic aldehydes (Fig. 1). Principal components analysis of the activity patterns evoked by these odorants in individual animals just missed significance in the second extracted factor (F4,15 = 3.03, P = 0.051). The correlation coefficients for the averaged patterns evoked by the three stereoisomers of dimethylpyrazine (Fig. 7A) were identical at r = 0.78. The addition of one carbon to the dimethylpyrazines resulted in similarly high correlation coefficients (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the odorant tetramethylpyrazine produced a pattern of activity that was poorly correlated with patterns evoked by the other pyrazine odorants (Fig. 7B and 7C). Inspection of the original activity patterns suggested that tetramethylpyrazine activated a smaller area of the glomerular layer in the dorsal part of the bulb than did the other odorants in the series (Fig. 6A). An indication of a greater difference between the 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine pattern and the other patterns also was present in post-hoc tests associated with the principal components analysis. Thus, having an aromatic structure strongly determines where in the bulb activity will be evoked, independently of the exact nature of the aromatic ring, and high correlations are observed for substitution position isomers for pyrazines and benzyl compounds alike. Also, 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine evoked patterns that were most different from the other pyrazines, thereby resembling our findings with 1,2,3,4-tetramethylbenzene.

Fig. 7.

Diagram displaying the overall pattern similarity between pairs of methyl-substituted pyrazines. Overall pattern similarity was determined by Pearson correlation analysis of the average activity patterns evoked by methyl-substituted pyrazines (Fig. 6A). A: High correlations were obtained for isomers of dimethylpyrazine. B: Correlations remain high for odorants differing by one methyl group, except for the comparison involving tetramethylpyrazine. C: Correlations are lower for odorants differing by two methyl groups, all of which involve comparisons to tetramethylpyrazine.

Isomers of anisaldehydes, which are aromatic odorants with benzene rings that are substituted with one aldehyde group and one methoxy group, also yielded patterns very similar to other odorants in this group. Figure 6B shows responses to benzaldehyde (pattern 21) as well as to o-, m-, and p-anisaldehyde (22–24) tested in the same experiment. Once again, glomerular activity was observed in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial parts of the bulb. This activity appeared to be located more rostrally than the responses to the pyrazines. An analysis of pattern correlations for isomers of anisaldehyde involving averaged activity patterns is shown in Figure 8A. These correlations among these odorants are also high and average slightly above 0.6. However, principal components analysis performed on individual activity patterns evoked by anisaldehyde odorants revealed significant differences in the first extracted factor (F2,15 = 6.05, P = 0.012). Inspection of the activity patterns in Figure 6B suggested that the main difference in activity patterns involved a more focal stimulation of glomeruli by p-anisaldehyde (pattern 24). Post-hoc tests associated with the principal components analysis indicated a significant difference between the patterns evoked by p-anisaldehyde and m-anisaldehyde (pattern 23).

Fig. 8.

Diagram displaying the overall pattern similarity of anisaldehydes and aromatic compounds with different functional groups. A: Correlations involving averaged activity patterns evoked by anisaldehyde isomers and benzaldehyde. B: Correlations involving activity patterns evoked by methyl benzoate and other aromatic methyl esters possessing another substituent in an adjacent position. Methyl anthranilate, which possesses an amine group adjacent to the methyl ester, evoked a pattern less correlated with the other patterns.

In a prior report, we found strong activation of the dorsal region of the bulb by the aromatic compounds methyl anthranilate and methyl salicylate, each of which is substituted by a combination of a methyl ester and another polar functional group in an adjacent (ortho) position (Johnson et al., 2005b). To complete our survey of substitution position effects in aromatic odorants, we tested responses to methyl 3-aminobenzoate (pattern 28), which is a stereoisomer of methyl anthranilate (pattern 27) that has substituents present in a meta-position, and methyl 3-hydroxybenzoate (pattern 30), which is a similar stereoisomer of methyl salicylate (pattern 29). The main effect of the change in substitution position was that the meta-substituted compounds evoked little, if any, activity pattern when diluted in mineral oil at the same ratio as the ortho-substituted odorants methyl anthranilate and methyl salicylate (Fig. 6C). Mineral oil was used as a solvent in this experiment because both of the meta-substituted compounds were solids at room temperature. It was our impression that both methyl 3-aminobenzoate and methyl 3-hydroxybenzoate had very faint odors, which might have been indicative of a low vapor-phase concentration, which would led to a weak activity pattern. Indeed, we initially intended to use as odorants the para-substituted compounds methyl 4-aminobenzoate and methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate as well, but we found them to be completely odorless, and we eliminated them from the experiment. Hence, one important effect of substitution position might be to change the vapor pressure and the ability of an aromatic odorant to serve as an effective olfactory stimulus.

Additional functional groups minimally affect activity patterns evoked by aromatic methyl esters

In the same experiment in which we tested isomers of methyl anthranilate and methyl salicylate, we also included methyl benzoate (pattern 25) and o-tolualdehyde (pattern 26) to test the effect of the presence and nature of the substituent that was present in addition to the methyl ester group on these aromatic odorants (Fig. 6C). Unlike our findings with aliphatic compounds (Johnson and Leon, 2000a; Johnson et al., 2002, 2004), changing the functional group did not activate unique response modules in the bulb. Instead, activity remained primarily in the same general dorsolateral and dorsomedial regions activated by the previously studied aromatic odorants (Fig. 6C). However, principal components analysis of the activity patterns from individual animals revealed a significant difference between odorants involving the first extracted factor (F3,17 = 7.13, P = 0.0026). Figure 8B shows correlation coefficients reflecting similarity in average patterns across these aromatic odorants with different functional groups. Changing functional groups within this series involving aromatic methyl esters did not greatly affect pattern similarity, although comparisons involving methyl anthranilate suggested that the amino group might have had a greater effect than the other substituents. Inspection of the overall response pattern suggests that methyl anthranilate generated a lower level of activation than did the other odorants in the series (Fig. 6C). Post-hoc tests associated with the principal components analysis confirmed a difference between methyl anthranilate and all other odorants in this sub-series.

Spatial response patterns in the olfactory bulb are related to response patterns in the olfactory epithelium

Scott and coworkers have presented evidence that different aromatic odorants activate different regions of the olfactory epithelium. Specifically, despite the fact that methyl benzoate (see Fig. 9A, structure 31) and phenyl acetate (see Fig. 9A, structure 33) differ only in the orientation of their ester bond, methyl benzoate stimulated relatively more parts of the dorsal epithelium than did phenyl acetate (Scott et al., 2000). In fact, it was a general finding that aromatic esters like methyl benzoate that had the benzene ring on the “acid” side of the ester bond stimulated more dorsally than did the esters with the benzene ring on the “alcohol” side of the ester bond (Scott et al., 2000). Given the general topographic projection from the epithelium to the bulb (Schoenfeld et al., 2002), one would predict that these odorants also would stimulate different parts of the olfactory bulb in accord with their response in the epithelium.

Fig. 9.

Contour charts and a diagram of centroid analysis of the series of aromatic esters that were used to test relationships between epithelial and bulbar activity patterns. A: Contour charts of 2-deoxyglucose uptake across the entire glomerular layer. All patterns of glomerular activity are presented as dorsal-centered charts instead of the ventral-centered format we have used in our prior publications. Each chart shows averaged activity across both bulbs of all rats exposed to a given odorant (see Figure 1 for color key and orientation of contour charts). The right panel displays the results of ANOVA tests illustrating differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using false discovery rate (FDR) analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were conducted. A single module that was significantly different after FDR correction is indicated with an asterisk. Outlined in the dorsolateral and dorsomedial regions of each contour chart are the areas used for centroid analysis in B. B: The center of each ellipse indicates the mean position of the centroid in different animals exposed to the same odorant. The height of each ellipse indicates the standard error of the mean in the dorsal-ventral dimension, and the width indicates the standard error in the rostral-caudal dimension. The coordinates of the centroids in the medial aspect differed across the five odorants as determined by using ANOVA. As predicted, the centroids of aromatic esters with the benzene ring on the alcohol side of the ester bond were segregated from those esters with the benzene ring on the acid side of the bond. There was no significant change in the centroid of activity in the lateral region.

To test the prediction that aromatic esters would stimulate different parts of the bulb depending on the orientation of the ester bond, we chose the five odorants depicted in Figure 9A. As is clearly apparent, all five odorants stimulated the dorsolateral and dorsomedial regions that responded to other aromatic compounds (Fig. 9A). However, there appeared to be regions of differential response across the five aromatic esters. A statistically significant difference across the patterns was confirmed using the ANOVA/FDR analysis of our previously defined glomerular modules, wherein one medial module was found to differ across the five patterns (Fig. 9A, right panel). To better characterize this difference, we separately outlined the dorsomedial and dorsolateral regions of response and subjected the underlying data to a centroid analysis. As shown in Figure 9B, left, this centroid analysis in the dorsomedial region neatly segregated the responses to methyl benzoate (31) and methyl phenylacetate (32), which have the benzene ring on the acid side of the bond, from the responses to phenyl acetate (33), phenyl propionate (34), and benzyl acetate (35), which have the benzene ring on the alcohol side of the bond. The differences in dorsomedial centroids across the five odorants were statistically significant (F4,20 = 2.87, p < 0.05). However, the ester odorants that stimulated more dorsally in the epithelium stimulated primarily more caudal regions in the bulb. Similar centroid analyses in the dorsolateral region of the bulb (Fig. 9B, right) did not yield statistically significant results, although there was a slight tendency for responses to methyl benzoate and methyl phenylacetate to be located more caudally.

Alkyl substituent carbon number, but not branching, affects activity patterns evoked by aromatic hydrocarbons

As we noted in a previous report, not all aromatic compounds activate the dorsolateral and dorsomedial parts of the bulb (Johnson et al., 2005b). In order to investigate which specific chemical features contribute to this difference in activity patterns, we investigated the glomerular activity patterns evoked by several aromatic hydrocarbon compounds that systematically differed in either carbon number within a straight-chained alkyl substituent or branching of the alkyl substituent (see the structures in Figure 10, patterns 36–40).

Fig. 10.

Contour charts illustrating patterns evoked by odorants differing in the length and branching of a single alkyl substituent. Patterns are presented as dorsal-centered charts instead of the ventral-centered format we have used in our prior publications. Each chart indicates locations of 2-deoxyglucose uptake across the entire glomerular layer averaged across both bulbs of all rats exposed to a given odorant (see Figure 1 for z-score key and orientation of contour charts). The right panels show the results of study-wise ANOVA tests that analyzed differences in z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks. These areas help to indicate the possible spatial locations of areas activated differently by the different odorants in each study.

All of these aromatic hydrocarbons evoked activity in dorsolateral and dorsomedial regions of the bulb, although the pattern evoked by n-butylbenzene (pattern 39) appeared less intense than those evoked by the other odorants (Fig. 10). Principal components analysis on activity patterns from individual animals indicated significant differences across odorants in both the first (F4,15 = 3.18, P = 0.044) and the second extracted factor (F4,15 = 6.51, P = 0.003). Post-hoc tests associated with both factors indicated that patterns evoked by n-butylbenzene differed significantly from all other patterns, and no other differences between patterns was indicated by these post-hoc tests. The right panel of Figure 10 shows results of an ANOVA/FDR performed on the five activity patterns. Three previously described modules yielded significantly different uptake in this analysis, and these three regions appeared to correspond primarily to differences in patterns between n-butylbenzene and the other four odorants. To quantify the similarity of activity patterns across these odorants, we determined correlation coefficients between pairs of averaged activity patterns. These correlation values are shown in Figure 11. Across the aromatic hydrocarbons, correlation coefficients were generally similar and averaged slightly above 0.7, with the exception of correlations associated with n-butylbenzene. This latter compound produced correlation values of 0.60 to 0.65 with the other odorants in this group. A possible explanation for this difference may be the length of its straight-carbon chain (four carbons). Tert-butylbenzene, which also has a four-carbon substituent, but in a branched isomer, was more highly correlated with other patterns than was n-butylbenzene.

Fig. 11.

Diagram displaying the overall pattern similarity between different aromatic hydrocarbons. Overall pattern similarity determined by pair-wise Pearson correlation analysis of the average activity patterns shown in Figure 10 A. Horizontal lines indicate comparisons of pairs of isomers. Dotted lines show comparisons of odorants differing by one carbon. Bold lines indicate comparisons of odorants differing by two carbons.

It is interesting to note that the local, unidirectional progressions of activity that are typically observed within modules responding to straight-chained aliphatic odorants of increasing carbon number (Johnson et al., 1999, 2004; Ho et al., 2005) were not seen for this series of aromatic hydrocarbons.

Aromatic hydrocarbons evoke spatial activity patterns that differ from other aromatic odorants

The individual experiments that we have discussed have revealed a number of systematic relationships between details of the chemical structures of aromatic odorants and their evoked activity patterns. In order to address the overall relationships between the activity patterns obtained across numerous experiments, we conducted a principal components analysis involving all of the average patterns already discussed in this report, as well as additional average patterns evoked by aromatic odorants, some of which have been published previously (Table 1).

The first factor of the principal components analysis, accounting for 27% of the variance, segregated activity patterns involving several phenols (yellow symbols in Figure 12A), an alcohol, and a few other patterns (cluster 1) from the other patterns. For many, although not all, of these exposures, the patterns resembled blanks in that they were patchy and characterized by a narrow range of z scores. The associated odorants have relatively low predicted vapor pressures, suggesting that they probably were present at a low vapor phase concentration in the exposures. Of greater interest to us was the second factor of the principal components analysis, which accounted for 6% of the variance. This factor very neatly segregated all of the activity patterns evoked by aromatic hydrocarbons (cluster 2, light blue symbols in Figure 13A) from all of the other aromatic odorants associated with different functional groups.

Fig. 12.

Scatter chart showing a plot of factor 1 versus factor 2 from a principal components analysis. Principal components analysis was conducted on a correlation matrix calculated using average activity patterns for all odorants in the present study as well as from additional published and unpublished aromatic odorants in our archive. A: Plots of loadings on the first and second factors extracted by the principal components analysis segregated all of the aromatic odorant-evoked activity patterns into three broad categories that we have enclosed by dotted outlines and labeled as clusters 1–3. Individual odorant exposures appear as circles labeled with numbers identifying the exposure in Table 1. The chemical classifications of the odorants are given by colors as indicated in the inset. Odorants possessing more than one substituent are shaded using more than one color. Cluster 2 is comprised entirely by aromatic hydrocarbons, which do not contribute to any other cluster. B: The activity patterns contributing to each cluster were averaged to help elucidate possible features of the patterns that would explain the relationships extracted by the principal components analysis.

Aromatic odorants substituted with aldehyde functional groups (red symbols in Fig. 12A) and ester functional groups (green symbols) were somewhat intermingled within the other group of patterns separated from the aromatic hydrocarbons by the second factor of the principal components analysis (cluster 3). However, there was a tendency for the aromatic esters to be clustered at higher values of factor 1 and lower values of factor 2 than the aldehydes. Pyrazines with methyl group substituents (white symbols) also were interspersed with the benzene compounds that contained oxygen-containing functional groups within cluster 3.

To gain a better understanding of the results of the principal components analysis, we calculated an average z-score pattern across all of the odorants in cluster 2 (aromatic hydrocarbons, light blue symbols in Figure 12A), which we display in Figure 12B. We averaged separately the patterns in cluster 1 and those in cluster 3 (Fig. 12B). The most obvious difference between the aromatic hydrocarbons in cluster 2 and the other odorants was the presence of activity in more ventral positions for the aromatic hydrocarbons (open arrows in Fig. 12B). This more ventral activity recalls the finding in our first experiment, where various aromatic hydrocarbons were found to stimulate more ventral regions than various aromatic aldehydes. Consistent with the overall abundance of light activity patterns in cluster 1, the average pattern for this cluster was characterized by low values overall. The activity within the average pattern for odorants within cluster 1 also was present somewhat more rostrally than for the other clusters (solid arrows in Fig. 12B), a characteristic that was apparent in several activity patterns evoked by individual phenols.

DISCUSSION

The dorsal region of the olfactory bulb contains chemotopic representations of aromatic odorants

This study has resulted in a number of new findings concerning the representation of aromatic odorants in the rat olfactory bulb. We found that aromatic odorants are chemotopically represented in the dorsal olfactory bulb, and that spatial activity patterns in the dorsal bulb are systematically affected by different aspects of aromatic odorant chemistry. First, responses to aromatic hydrocarbons are more ventral compared to responses evoked by aromatic odorants substituted with oxygen-containing functional groups. Second, we found that among aromatic hydrocarbons, odorants with similar numbers of methyl group substituents evoked similar overall patterns. Third, we found that odorants with long alkyl substituents failed to stimulate the dorsal regions that are characteristic of the representation of the other aromatic odorants. Fourth, among esters, odorants in which the benzene ring is on the alcohol side of the bond were represented more rostrally in the dorsomedial bulb than were odorants in which the benzene ring is on the acid side of the bond.

In comparing aliphatic to aromatic odorants, a number of similarities and differences have emerged. On a very general level, we observed global chemotopy for both classes of odorant, wherein the most similar stimuli had a tendency to evoke the most similar overall activation patterns. Positional isomers of aromatic compounds invariably evoked very similar activity patterns, a phenomenon that we had previously reported for enantiomers (Linster et al., 2001), differently branched isomers of aliphatic hydrocarbons (Ho et al., submitted), and isomers of most aliphatic compounds that differed in the position of a functional group along a hydrocarbon chain (Johnson et al., 2005a; Ho et al., submitted).

The most striking differences found between aliphatic and aromatic odorants were the effects of the presence of different functional groups. For aliphatic odorants, adding a single oxygen-containing functional group to a hydrocarbon straight chain results in a very specific pattern of activity in which the activity associated with the hydrocarbon chain is retained, but additional activity is evoked that is different for each functional group (Johnson and Leon, 2000a; Johnson et al., 2002, 2004, 2005a; Ho et al., 2005). In contrast, when we examined activity evoked by aromatic compounds, we found that adding an aldehyde functional group evoked a separate cluster of active dorsal glomeruli and that the activity associated with the corresponding aromatic hydrocarbon was no longer detectable. Also, when aromatic compounds with distinct oxygen-containing functional groups were compared, we saw only slight changes in the identity of the glomeruli activated in the same general dorsal region of the bulb, rather than the activation of unique functional group-related modules that are characteristic of the responses to aliphatic odorants (Johnson and Leon, 2000a; Johnson et al., 2002, 2004, 2005a). It seems possible that the unique pi-stacking capacity offered by these aromatic odorants (Meyer et al., 2003) largely determines which receptors respond best to these odorants. Additional specific interactions involving particular functional groups may contribute only to minor differences in the activity of neighboring glomeruli that are not easily detectable in our analyses.

Other researchers have investigated activity patterns in response to aromatic odorants using other methods of monitoring bulbar activity. For example, Takahashi et al. (2004) have shown using optical imaging of endogenous signals that individual glomeruli in the dorsolateral region of the olfactory bulb of individual anesthetized rats display unique specificities to aromatic odorants differing in the nature and position of substituents. Most of the odorants used by that group were phenols and phenyl ethers. Their study did not include many of the aromatic hydrocarbons, aromatic esters, or aromatic aldehydes that represented the bulk of our analyses. Many of our compounds stimulated more posterior regions of the bulb that may not have been easily accessible for optical recordings. Also, none of the medial activity reported here was represented in the optical recordings of Takahashi et al. (2004).

Katoh et al. (1993) found electrophysiological evidence for selective tuning of individual mitral or tufted cells in the olfactory bulb of the anesthetized rabbit to aromatic hydrocarbons such as were included in the present study. It is possible that these responses overlap with ours, although the schematics included in their report seems to indicate a more ventral and rostral location of the medial responses (Katoh et al., 1993). Odorant concentration effects, as well as species differences, might account for any differences in the locations of these responses.

The patterns of activity evoked by aromatic odorants in the olfactory bulb are related to patterns of activation in the olfactory epithelium

Scott et al. (2000) have shown that isomeric aromatic esters with inverted bonds activate different regions of the epithelium. Consistent with their findings, we successfully predicted differences the location of the response in the olfactory bulb in the present study. However, there were some differences in that the dorsal-ventral differences in the epithelium were paralleled by apparent caudal-rostral differences in the medial bulb. This difference does not match the canonical dorsal-ventral topography recognized for the epithelium-to-bulb projection (Schoenfeld and Knott 2003, 2004), despite the fact that the other chemotopic shifts in activity patterns we have observed previously do match this topography (Johnson et al., 1999, 2004; Johnson and Leon, 2000b; Ho et al., 2005). Furthermore, we did not observe the same type of organization in the lateral bulb, whereas our activity patterns are typically symmetrical with respect to lateral and medial aspects. It therefore would not be surprising if the epithelial response areas were found to project with a unique topography to the areas that we have identified with our functional analysis.

Scott and his colleagues (Scott et al., 2000) also examined activity patterns in the epithelium evoked by a number of other aromatic odorants that were also used in the current study (toluene, benzaldehyde, and methyl benzoate). For these odorants, dorsal-ventral shifts in activation in the epithelium were matched by dorsal-ventral shifts in activation of the bulb in the present study. These shifts were equally evident in the lateral and medial aspects of the bulb.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found a distinct spatial organization of activity patterns in the dorsal region of the olfactory bulb in response to aromatic odorants differing in functional group, position, or numbers of methyl groups. Furthermore, a clear difference in activation patterns was observed between aromatic hydrocarbons and aromatic odorants with oxygen-containing functional groups. Our findings suggest a chemotopic representation of aromatic odorants, consistent with our previous findings for aliphatic odorants, in spite of substantial differences between the chemical structures of aliphatic and aromatic odorants.

Supplementary Material

Ventral-centered charts of patterns evoked by aromatic odorants which were shown in Figure 1 as dorsal-centered charts. These charts represent data matrices averaged across multiple rats and are presented as rolled-out maps of the glomerular layer as if cut dorsally along the anterior to posterior direction. The right panel on the first row displays results of ANOVA tests expressing differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks.

Ventral-centered charts of patterns evoked by aromatic odorants that were shown in Figure 6 as dorsal-centered charts. A: Aromatic odorants involving methyl-substituted pyrazine rings. B; Benzaldehyde and positional isomers of anisaldehyde. C: Aromatic odorants involving a methyl ester substituent with and without other substituents. The charts are oriented as in supplementary Figure 1.

Ventral-centered charts of the patterns evoked by aromatic ester odorants that were shown in Figure 9 as dorsalcentered charts. These charts are oriented as in supplementary Figure 1. The right panel displays the results of ANOVA tests expressing differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks.

Ventral-centered charts of the patterns evoked by aromatic odorants differing in the length and branching of a single alkyl substituent that were shown in Figure 10 as dorsal-centered charts. The charts are oriented as in supplementary Figure 1. The right panel displays the results of ANOVA tests expressing differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paige Pancoast, Jennifer Kwok, Sepideh Saber, Zhe Xu and Joan Ong for technical assistance with sectioning and mapping. We further thank Spart Arguello for developing a database for our matrices, for writing software to analyze the matrices, and for creating and maintaining our Web site.

Supported by United States Public Health Service grant DC03545

LITERATURE CITED

- Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odor recognition: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65:175. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel O, Meier MS, Schlatter J, Frischknecht P. Selected phenolic compounds in cultivated plants: Ecological functions, health implications, and Modulation by pesticides. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(S1):109–114. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchman ML, Spackman RA, Ross NC, Agra C. Disposal methods for chlorinated aromatic waste. Chem Soc Rev. 1995:423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Ho SL, Johnson BA, Leon M. Long hydrocarbon chains serve as unique molecular features recognized by ventral glomeruli of the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/cne.20973. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Woo CC, Leon M. Spatial coding of odorant features in the glomerular layer of the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:457–471. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980420)393:4<457::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Woo CC, Hingco EE, Pham KL, Leon M. Multidimensional chemotopic responses to n-aliphatic acid odorants in the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409:529–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Leon M. Modular representations of odorants in the glomerular layer of the rat olfactory bulb and the effects of stimulus concentration. J Comp Neurol. 2000a;422:496–509. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000710)422:4<496::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Leon M. Odorant molecular length: one aspect of the olfactory code. J Comp Neurol. 2000b;426:330–338. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001016)426:2<330::aid-cne12>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Ho SL, Xu Z, Yihan JS, Yip S, Hingco EE, Leon M. Functional mapping of the rat olfactory bulb using diverse odorants reveals modular responses to functional groups and hydrocarbon structural features. J Comp Neurol. 2002;449:180–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Farahbod H, Xu Z, Saber S, Leon M. Local and global chemotopic organization: general features of the glomerular representations of aliphatic odorants differing in carbon number. J Comp Neurol. 2004;480:234–249. doi: 10.1002/cne.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Farahbod H, Leon M. Interactions between odorant functional group and hydrocarbon structure influence activity in glomerular response modules in the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:205–216. doi: 10.1002/cne.20409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Farahbod H, Saber S, Leon M. Effects of functional group position on spatial representations of aliphatic odorants in the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:192–204. doi: 10.1002/cne.20415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Koshimoto H, Tani A, Mori K. Coding of odor molecules by mitral/tufted cells in rabbit olfactory bulb. II. Aromatic compounds. Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2161–2175. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.5.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon M, Johnson BA. Olfactory coding in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster C, Johnson BA, Morse A, Yue E, Xu Z, Hingco EE, Choi Y, Choi M, Messiha A, Leon M. Perceptual correlates of neural representations evoked by odorant enantiomers. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9837–9843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09837.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EA, Castellano RK, Diederich F. Interactions with aromatic ring in chemical and biological recognition. Angew Chem int Ed. 2003;42(11):1210–1250. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DN. Accumulation and consumption of odorous compounds in feedlot soils under aerobic, fermentative and anaerobic respiratory conditions. J Anim Sci. 2001;79:2503–2512. doi: 10.2527/2001.79102503x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P, Wang F, Dulac C, Chao SK, Nemes A, Mendelsohn M, Edmondson J, Axel R. Visualizing an olfactory sensory map. Cell. 1996;87:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Sullivan SL, Buck LB. Information coding in the olfactory system: evidence for a stereotyped and highly organized epitope map in the olfactory bulb. Cell. 1994;79:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld TA, Knott TK. NADPH diaphorase activity in olfactory receptor neurons and their axons conforms to a rhinotopically-distinct dorsal zone of the hamster nasal cavity and main olfactory bulb. J Chem Neuroanat. 2002;24:269–285. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(02)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld TA, Knott TK. Evidence for the disproportionate mapping of olfactory airspace onto the main olfactory bulb of the hamster. J Comp Neurol. 2004;476:186–201. doi: 10.1002/cne.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JW, Brierley T, Schmidt FH. Chemical determinants of the rat electro-olfactogram. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4721–4731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04721.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi YK, Kurosaki M, Hirono S, Mori K. Topographic representation of odorant molecular features in the rat olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2413–2427. doi: 10.1152/jn.00236.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Takahashi YK, Tanifuji M, Mori K. Odor maps in the mammalian olfactory bulb: domain organization and odorant structural features. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1035–1043. doi: 10.1038/79857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Chao SK, Sitcheran R, Nuñez JM, Vosshall LB, Axel R. Topographic organization of sensory projections to the olfactory bulb. Cell. 1994;79:981–991. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachowiak M, Cohen LB. Representation of odorants by receptor neuron input to the mouse olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2001;32:723–735. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ventral-centered charts of patterns evoked by aromatic odorants which were shown in Figure 1 as dorsal-centered charts. These charts represent data matrices averaged across multiple rats and are presented as rolled-out maps of the glomerular layer as if cut dorsally along the anterior to posterior direction. The right panel on the first row displays results of ANOVA tests expressing differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks.

Ventral-centered charts of patterns evoked by aromatic odorants that were shown in Figure 6 as dorsal-centered charts. A: Aromatic odorants involving methyl-substituted pyrazine rings. B; Benzaldehyde and positional isomers of anisaldehyde. C: Aromatic odorants involving a methyl ester substituent with and without other substituents. The charts are oriented as in supplementary Figure 1.

Ventral-centered charts of the patterns evoked by aromatic ester odorants that were shown in Figure 9 as dorsalcentered charts. These charts are oriented as in supplementary Figure 1. The right panel displays the results of ANOVA tests expressing differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks.

Ventral-centered charts of the patterns evoked by aromatic odorants differing in the length and branching of a single alkyl substituent that were shown in Figure 10 as dorsal-centered charts. The charts are oriented as in supplementary Figure 1. The right panel displays the results of ANOVA tests expressing differences in average z-score values across 30 previously defined glomerular modules. Glomerular modules are outlined and color-coded by p value: yellow, 0.05 > p > 0.01; orange, 0.01 > p > 0.001; red, p < 0.001. The ANOVA results were analyzed further by using FDR analysis to correct for the fact that 30 different tests were performed. Modules that were significantly different after FDR correction are indicated with asterisks.