Abstract

Background

The reported association between low maximum diastolic blood pressure (DBP) during pregnancy and perinatal death (stillbirth and death in the first week combined) may result from failure to account for gestational length, a strong predictor of perinatal death.

Methods

We studied 41,089 singleton pregnancies from the U.S. Collaborative Perinatal Project (1955–1966).

Results

The association between low maximum DBP and elevated risk of perinatal death disappeared after accounting for reverse causation related to gestational length. At any given gestational week, women whose offspring ultimately experienced perinatal death did not have significantly lower maximum DBP than women whose offspring survived the perinatal period. When accounting for DBP trend during pregnancy through gestational-age-specific DBP standardized score, we saw no association between a mean low score and perinatal death.

Conclusions

Low maximum maternal DBP during pregnancy was a post hoc correlate of perinatal death in these data, but not a risk factor.

A recent UK study suggested that babies whose mothers had low diastolic blood pressure (DBP) during pregnancy had an increased risk of perinatal death.1 A similar finding had been reported in an earlier study among a segment of women enrolled in the US Collaborative Perinatal Project (CPP).2 Both studies used as a marker the highest recorded value of DBP during pregnancy. However, since blood pressure normally decreases in the early second trimester and then increases in late pregnancy,3 the maximum recorded DBP will depend in part on gestational length, a strong predictor of perinatal death. Furthermore, the maximum value over a set of measurements becomes higher as the number of measurements increases, resulting in the tendency for shorter pregnancies to have a lower maximum.

To assess the association between low DBP and perinatal death, we reanalyzed the full data from the CPP, with particular attention to the problems involved in using maximum DBP over the whole pregnancy as a predictor.

METHODS

The CPP was a prospective pregnancy cohort of 58,760 pregnancies from 48,197 women recruited in 12 academic medical centers in the U.S. between 1959 and 1966.4 Women were enrolled during pregnancy (median gestation at enrollment: 21 weeks, inter-quartile range: 15–28 weeks).

We excluded 623 multifetal pregnancies and 3,432 pregnancies not ending in a birth. For 9,759 woman contributing more than one singleton birth, we retained only the earliest. We further excluded 302 with gestational length (based on the date of last menstrual period) that was missing or recorded as being below 20 or above 51 weeks (allowing for some degree of error in dating). We additionally excluded 1,623 pregnancies with no valid maternal DBP measurement and 22 women with no DBP measurement higher than 40 mmHg or lower than 110 mmHg. Among women with measurements within the above range, we excluded any value <40 or >110 mmHg. While we included women with hypertension during pregnancy in most analyses, we excluded those with reported history of hypertension before pregnancy and those who developed proteinuria during pregnancy (n=1,910). We thus analyzed 41,089 singleton births.

Blood pressure was measured by sphygmomanometer at registration, at each subsequent prenatal visit, and at the time of labor. For diastolic blood pressure, either Korotkoff phase 4 (muffling of the sound) or phase 5 (disappearance of the sound) was used.5 If a woman had more than one blood pressure measurement during a specific gestational week, we only used the earliest valid one within that gestational week. Perinatal death was defined as the combination of fetal death after 20 weeks of gestation and death within the first 7 days after birth.

We started by using the highest DBP value during pregnancy as a predictor of perinatal death, as in previous studies.1,2 We then checked whether maximum DBP depended on the length of gestation and the number of measurements. By comparing the maximum DBP up to a given week between women who ultimately experienced perinatal death and women who did not, we assessed if a low maximum DBP predicted perinatal death. Finally, to account for the trend of increasing DBP in the third trimester of pregnancy, we calculated a gestational-age-specific DBP z-score and used percentiles of mean z-score to predict perinatal death. In the logistic regression models, we adjusted for race, maternal age, parity, socio-economic status, smoking during pregnancy, and maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) (covariates categorized as in table 1). We additionally adjusted for study center (Boston, Buffalo, New Orleans, New York Columbia, Baltimore, Richmond, Minneapolis, New York Metropolitan, Portland, Philadelphia, Providence, and Memphis). We used R 2.3.16 for graphs and splines, and SAS 9.17 for statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Perinatal mortality by socio-demographic characteristics in 41,089 pregnant women, Collaborative Perinatal Project, 1959–1966

| Characteristics | n* | Perinatal mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal race | ||

| White | 18950 | 2.75 |

| Black | 18653 | 3.23 |

| Others | 3486 | 3.13 |

| Maternal age at registration | ||

| <20 years | 10644 | 2.60 |

| 20–24 years | 14801 | 2.60 |

| 25–29 years | 8346 | 3.02 |

| 30–34 years | 4433 | 4.44 |

| ≥35 years | 2865 | 4.29 |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 15367 | 2.71 |

| 1 | 8804 | 2.54 |

| 2 | 6046 | 3.06 |

| ≥3 | 10794 | 3.69 |

| Maternal socioeconomic index† | ||

| 0.0–3.9 | 15575 | 3.00 |

| 4.0–5.9 | 12304 | 3.02 |

| 6.0–9.5 | 12008 | 2.68 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | ||

| No smoking | 21958 | 2.86 |

| 0–9 cigarettes/day | 8036 | 2.65 |

| 10–19 cigarettes/day | 5090 | 3.22 |

| ≥20 cigarettes/day | 5681 | 3.68 |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI | ||

| <20 kg/m² | 10411 | 2.77 |

| 20–24.9 kg/m² | 19890 | 2.76 |

| 25–29.9 kg/m² | 5412 | 3.25 |

| ≥30 kg/m² | 2141 | 3.78 |

| Gestational week at delivery | ||

| <28 weeks | 599 | 62.27 |

| 28–31 weeks | 916 | 21.18 |

| 32–36 weeks | 5019 | 5.30 |

| 37–38 weeks | 7805 | 1.56 |

| 39–40 weeks | 15620 | 0.83 |

| ≥41 weeks | 11130 | 1.34 |

The sum of n for each characteristic may not be 41089 due to missing value.

Socioeconomic index is a composite index for education, occupation, and family income. A low score corresponds to a low socioeconomic status.

RESULTS

Among the 41,089 babies in the analysis sample, 671 were stillborn (1.6%) and 563 died within the first 7 days of life (1.4%), yielding a total of 1234 perinatal deaths (3.0%). Black race, older age, higher parity, lower socioeconomic status, smoking, and obesity were all associated with higher perinatal mortality, as was a shorter gestation (table 1).

The mean gestational age at delivery was 39 weeks (standard deviation [SD] =3). The mean number of blood pressure measurements per woman was 7 (SD=4, range 1–29). Women whose baby died perinatally had shorter gestation (mean=32 weeks, SD=7, range 20–47), and fewer blood pressure measurements (mean=5, SD=4, range 1–26).

As expected, DBP decreased in the second trimester and increased during the third trimester (not shown). The mean maximum DBP increased with gestational length and with increasing number of blood pressure measurements(from 75 mmHg with 2 measurements to 83.5 mmHg with 13 or more measurements). The effect of gestational length and number of measurements on mean DBP was, on the other hand, limited.

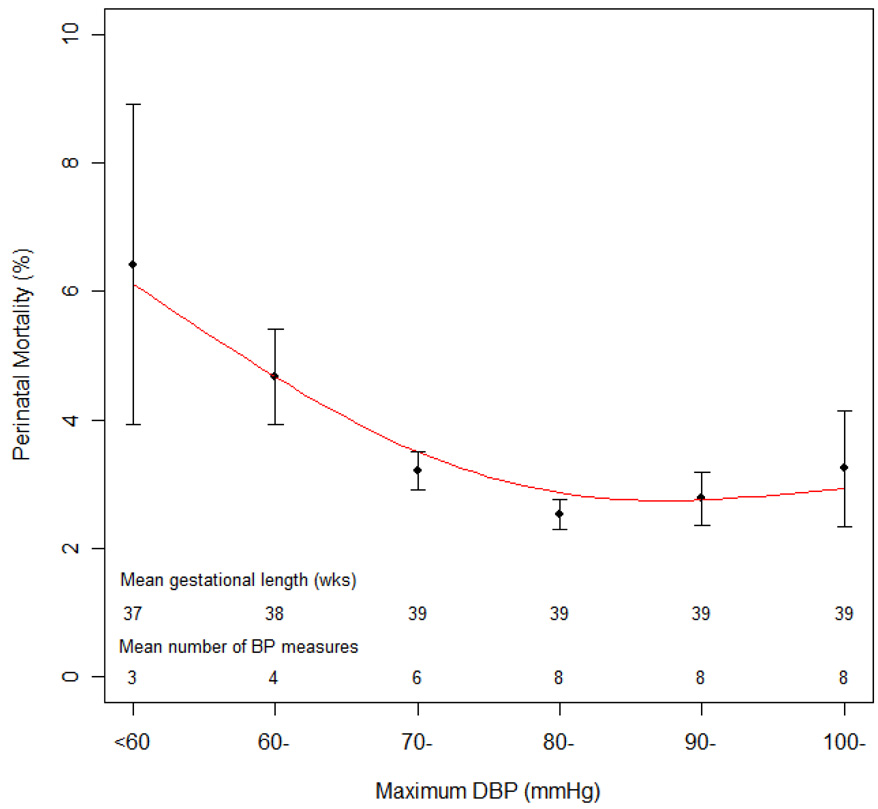

Similar to what shown by Steer et al.,1 the relation between maximum DBP and perinatal mortality was U-shaped, with highest mortality at the lowest maximum DBP (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perinatal mortality and 95% confidence interval by maximum DBP during pregnancy in 41,089 pregnant women, Collaborative Perinatal Project, 1959–1966 Legend: The line is the smoothed spline of estimated perinatal mortality.

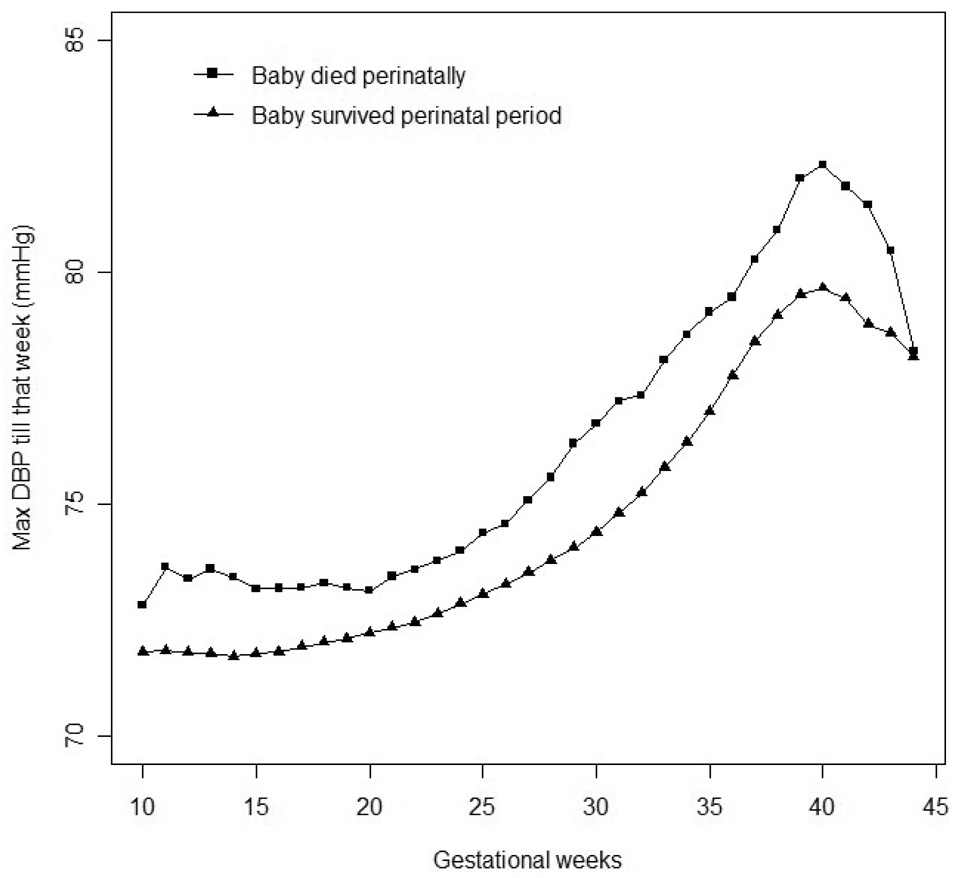

Women with lower maximum DBP had, on average, a shorter gestation and fewer BP measurements. Both of these factors could contribute to biasing any inference based on figure 1, as suggested by the fact that, at any gestational age, a low maximum DBP up to that point was not predictive of perinatal death (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maximum DBP till a specific gestational week in ongoing pregnancies, stratified by whether the baby ultimately experienced perinatal death or not, in 41,089 pregnant women, Collaborative Perinatal Project, 1959–1966

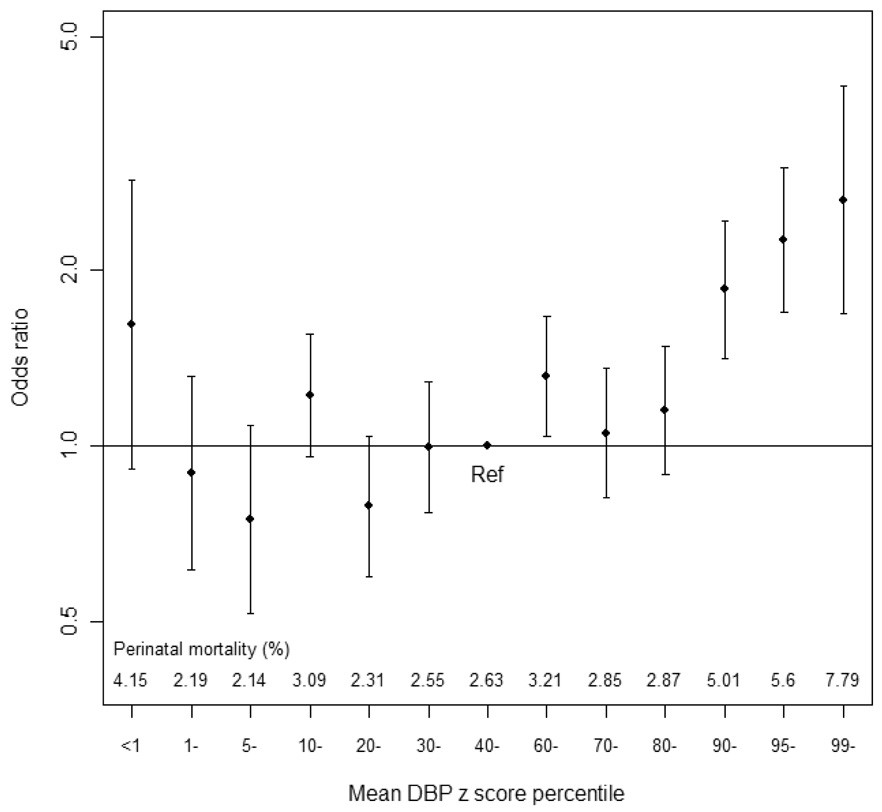

When using gestational-age-specific mean DBP z-score percentiles, we saw no significantly elevated risk of perinatal death among women with low z scores (figure 3). To obtain more precise estimates, we defined as low and high DBP the lowest and highest 10% of z-score, respectively. The perinatal death rate was 2.4% for the lowest and 5.5% for the highest decile. The corresponding adjusted ORs were 0.88 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.67, 1.16) and 2.08 (95% CI: 1.68, 2.59), respectively, compared with a DBP z-score between the 40th and 59th percentiles.

Figure 3.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence interval for perinatal death by percentiles of mean DBP z score in 41,089 pregnant women, Collaborative Perinatal Project, 1959–1966

The results persisted when including DBP measurements with values <40 or >110 mmHg, using mean DBP, restricting to women registered early in pregnancy or with DBP≤90 mmHg, or using different categorizations of mean DBP z-score (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis, low maximum maternal DBP during pregnancy appeared to be a post hoc correlate of perinatal death. At no point in pregnancy was a low maximum DBP predictive of perinatal death, suggesting that such a marker would not be a useful clinical predictor of risk. The association between low maximum DBP across the whole pregnancy and perinatal death likely reflects bias due to differential-by-outcome mean lengths of gestation and the corresponding differential mean number of BP measurements. Thus, our analysis suggests that the previous findings1,2 likely resulted from an artifact due to the failure to account for reverse causation related to gestational length.

Using mean gestational-age-specific DBP z-score should produce a marker of DBP that eliminates the artifactual correlation between maximum DBP and gestational length. Our analysis based on the z-score indicated that there was no significant association between lower DBP during pregnancy and perinatal mortality, although the lowest 1% of z-score came close to statistical significance. Whether this may have clinical relevance in a subgroup of women remains to be determined.

Previous studies suggested that maternal hypotension during pregnancy (often defined as BP ≤ 110/65 mmHg) may be associated with reduced utero-placental perfusion, prematurity, and low birth weight.8–12 However, these studies often included few women or lacked adjustment for potential confounders.13 Zhang and Klebanoff argued that the adverse outcomes in women with low DBP were due to their characteristics, such as low pre-pregnancy BMI and low social status, rather than to low DBP per se.14

This was a large prospective cohort with multiple blood pressure measurements. However, our study has limitations. Recruitment occurred between 1959 and 1966, and perinatal death has substantially decreased since. Nonetheless, replicating the analysis of Steer et al,1 we found an association when using maximum DBP throughout pregnancy, which disappeared after taking into consideration the fact that shorter gestations tended to have a low maximum DBP.

Overall, our analysis suggests that a low maternal blood pressure during pregnancy is not predictive of increased risk of perinatal death at the population level, and that maximum DBP throughout pregnancy is subject to bias as a predictor of poor perinatal outcome.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Clarice R Weinberg for invaluable advice on data analysis and writing, and to Dale P Sandler and Matthew P Longnecker for comments on an earlier draft.

Financial support This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences.

Contributor Information

Aimin Chen, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE, USA.

Olga Basso, Epidemiology Branch, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steer PJ, Little MP, Kold-Jensen T, Chapple J, Elliott P. Maternal blood pressure in pregnancy, birth weight, and perinatal mortality in first births: prospective study. BMJ. 2004;329(7478):1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38258.566262.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman EA, Neff RK. Hypertension-hypotension in pregnancy. Correlation with fetal outcome. JAMA. 1978;239(21):2249–2251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Iglesias M. Predictable blood pressure variability in healthy and complicated pregnancies. Hypertension. 2001;38(3 Pt 2):736–741. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niswander KR, Gordon M. The women and their pregnancies: the Collaborative Perinatal Study of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. Washington, DC: US Goverment Print Office; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman EA, Neff RK. Pregnancy hypertension: a systematic evaluation of clinical diagnostic criteria. Littleton, MA: PSG Publishing Co.; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 6.R Development Core Team. R: A Programming Environment for Data Analysis and Graphics. 2006 www.r-project.org.

- 7.SAS Institute I. SAS/STAT 9.1 User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunzel W. Hypotensive disorders during pregnancy as a cause of fetal hazard (author's transl) Z Geburtshilfe Perinatol. 1981;185(5):249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grunberger W, Parschalk O, Fischl F. Treatment of hypotension complicating pregnancy improves fetal outcome. Med Klin. 1981;76(9):257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunberger W, Leodolter S, Parschalk O. Pregnancy hypotension and fetal outcome. Fortschr Med. 1979;97(4):141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunberger W, Leodolter S, Parschalk O. Maternal hypotension: fetal outcome in treated and untreated cases. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1979;10(1):32–38. doi: 10.1159/000299915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunberger W, Leodolter S, Parschalk O. Pregnancy-connected hypotension - the influence of mineralo-corticoids on fetal nutrition (author's transl) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1978;38(12):1070–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng PH, Walters WA. The effects of chronic maternal hypotension during pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;32(1):14–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1992.tb01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Klebanoff MA. Low blood pressure during pregnancy and poor perinatal outcomes: an obstetric paradox. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(7):642–646. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.7.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]