Abstract

The endocannabinoid anandamide exerts neurobehavioral, cardiovascular, and immune-regulatory effects through cannabinoid receptors (CB). Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) is an enzyme responsible for the in vivo degradation of anandamide. Recent experimental studies have suggested that targeting the endocannabinergic system by FAAH inhibitors is a promising novel approach for the treatment of anxiety, inflammation, and hypertension. In this study, we compared the cardiac performance of FAAH knockout (FAAH−/−) mice and their wild-type (FAAH+/+) littermates and analyzed the hemodynamic effects of anandamide using the Millar pressure-volume conductance catheter system. Baseline cardiovascular parameters, systolic and diastolic function at different preloads, and baroreflex sensitivity were similar in FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice. FAAH−/− mice displayed increased sensitivity to anandamide-induced, CB1-mediated hypotension and decreased cardiac contractility compared with FAAH+/+ littermates. In contrast, the hypotensive potency of synthetic CB1 agonist HU-210 and the level of expression of myocardial CB1 were similar in the two strains. The myocardial levels of anandamide and oleoylethanolamide, but not 2-arachidonylglycerol, were increased in FAAH−/− mice compared with FAAH+/+ mice. These results indicate that mice lacking FAAH have a normal hemodynamic profile, and their increased responsiveness to anandamide-induced hypotension and cardiodepression is due to the decreased degradation of anandamide rather than an increase in target organ sensitivity to CB1 agonists.

Keywords: contractility, hypertension, cannabinoids, endocannabinoids

Two types of cannabinoid (cb) receptors, identified by molecular cloning, are responsible for the biological effects of marijuana and its main psychoactive ingredient Δ9-tetrahydro-cannabinol (THC). The CB receptor type 1 (CB1) is most abundant in the central nervous system (31) but can also be found in cardiovascular tissues (1, 4, 19, 28). The CB2 receptor is expressed predominantly by hematopoietic and immune cells (34). The primary endogenous ligands of these receptors, the endocannabinoids, comprise arachidonoyl ethanolamide or anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) (reviewed in Ref. 32). Besides well-known neurobehavioral and immunmodulatory effects, cannabinoids also affect the cardiovascular system (for recent overviews, see Refs. 36 and 37).

The hypotensive effect of AEA and other synthetic cannabinoids is mediated by CB1 present in the myocardium, where they cause negative inotropy (4, 38), and also in the vasculature (19, 28), where they lead to vasodilation (19, 46). The endocannabinoid AEA and CB receptors have been implicated in cardiovascular regulation under various pathophysiological conditions associated with hypotension, including hemorrhagic (47), endotoxic (1, 27, 44), and cardiogenic shock (45). Furthermore, there is emerging evidence suggesting that the endocannabinergic system plays an important role in the regulation of blood pressure (2, 24, 26, 40, 41) and various pathological conditions associated with inflammation (overviewed in Ref. 15).

Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the enzyme responsible for the degradation of AEA in vivo, has emerged as a promising target for modulating endocannabinoid signaling, with a therapeutic potential in anxiety, hypertension, and inflammatory disorders (reviewed in Refs. 9, 17, 36, and 37).

In this study we aimed to characterize the cardiovascular profile of FAAH knockout mice (FAAH−/−) compared with their wild-type littermates (FAAH+/+) and to analyze the hemodynamic effects of the endocannabinoid AEA. The results indicate that mice lacking FAAH have a normal hemodynamic profile and increased sensitivity to the hypotensive and cardiodepressant effects of AEA.

METHODS

All protocols were approved by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Hemodynamic measurements

Male FAAH−/− (n = 39) and FAAH+/+ (n = 40) mice weighing 25–30 g and 2–3 mo of age were used for the study. The animals were littermate offsprings of heterozygote breeding pairs, as previously described (7). The animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (80 mg/kg ip) and tracheotomized to facilitate breathing (38). Animals were placed on controlled heating pads, and core temperature measured via a rectal probe was maintained at 37°C. A microtip pressure-volume catheter (SPR-839; Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted into the right carotid artery and advanced into the left ventricle (LV) under pressure control as described (2, 38, 39). Polyethylene cannulas (PE-10) were inserted into the right femoral artery and vein for the measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and administration of drugs, respectively. After stabilization for 20 min, the signals were continuously recorded at a sampling rate of 1,000/s by using an ARIA pressure-volume (P-V) conductance system (Millar Instruments) coupled to a Powerlab/4SP analog-to-digital converter (AD Instruments, Mountain View, CA) and then stored and displayed on a computer. All P-V loop data were analyzed by using a cardiac P-V analysis program (PVAN3.2; Millar Instruments), and the heart rate (HR), maximal LV end-systolic pressure (LVESP), LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), MAP, maximal slope of systolic pressure increment (+dP/dt) and diastolic decrement (−dP/dt), ejection fraction (EF), stroke volume (SV), arterial elastance (Ea; end-systolic pressure/SV), cardiac output (CO), and stroke work (SW) were computed. The relaxation time constant (τ), an index of diastolic function, was also calculated by two different methods [Weiss method: regression of log(pressure) versus time; Glantz method: regression of dP/dt vs. pressure] using PVAN3.2. Total peripheral resistance (TPR) was calculated by the following equation: TPR = MAP/CO. In six additional FAAH+/+ and five FAAH−/− mice, hemodynamic parameters were determined under conditions of changing preload, elicited by transiently compressing the inferior vena cava (IVC) using a cotton swab, inserted through a small, transverse, upper abdominal incision. This technique yields reproducible occlusions in mice without opening the chest cavity. Because +dP/dt may be preload dependent, in these animals P-V loops recorded at different preloads were used to derive other useful systolic function indexes that may be less influenced by loading conditions and cardiac mass. These measures include the dP/dt-end-diastolic volume (EDV) relation (dP/dt-EDV), the preload-recruitable stroke work (PRSW), which represents the slope of the relation between SW and EDV and is independent of chamber size and mass, and the end-systolic PV relation [maximum chamber elasticity (ESPVR), Emax]. The slope of the end-diastolic PV relation (EDPVR), an index of LV stiffness, was also calculated from P-V relations using PVAN 3.2. (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). At the end of the experiments, animals were killed by an overdose of anesthetic (pentobarbital sodium).

Table 1.

Baseline hemodynamic parameters in FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice measured by Millar pressure-volume conductance catheter system

| FAAH+/+ | FAAH−/− | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR, beats/min | 473.5 ± 37.0 | 478.5 ± 30.5 | 0.92 |

| MAP, mmHg | 83.6 ± 4.3 | 84.6 ± 2.5 | 0.83 |

| LVESP, mmHg | 98.4 ± 5.0 | 101.8 ± 3.6 | 0.58 |

| LVEDP, mmHg | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 0.12 |

| CO, μl/min | 9,521 ± 1,307 | 8,822 ± 661 | 0.61 |

| EF, % | 62.7 ± 4.4 | 55.5 ± 1.9 | 0.11 |

| SW, mmHg·μl | 1,665 ± 168 | 1,624 ± 125 | 0.84 |

| +dP/dt, mmHg/s | 9,472 ± 1,218 | 9,211 ± 917 | 0.86 |

| −dP/dt, mmHg/s | 8,444 ± 1,397 | 7,831 ± 724 | 0.67 |

| τ (Weiss), ms | 7.7 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 0.7 | 0.68 |

| τ (Glantz), ms | 11.5 ± 1.2 | 10.4 ± 1.0 | 0.49 |

| TPR, mmHg·ml−1·min | 9.9 ± 0.6 | 10.2 ± 1.2 | 0.85 |

| Ea, mmHg/μl | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 0.71 |

| Emax, mmHg/μl | 9.7 ± 2.1 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 0.43 |

| PRSW, mmHg | 62.1 ± 9.3 | 57.8 ± 6.0 | 0.69 |

| (+dP/dt)/EDV, mmHg·s−1μl−1 | 224.2 ± 32.7 | 207.4 ± 39 | 0.76 |

| EDPVR slope, mmHg/μl | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.66 |

Values are means ± SE of 8 –12 experiments. HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; LVESP, left ventricular end-systolic pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; CO, cardiac output; EF, ejection fraction; SW, stroke work; +dP/dt, pressure increment; −dP/dt, pressure decrement; τ, relaxation time constant; TPR, total peripheral resistance; Ea, arterial elastance; Emax, maximum chamber elasticity; PRSW, preload-recruitable stroke work; EDV, end-diastolic volume; EDPVR, end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship. Student’s t-test was used for pairwise comparisons.

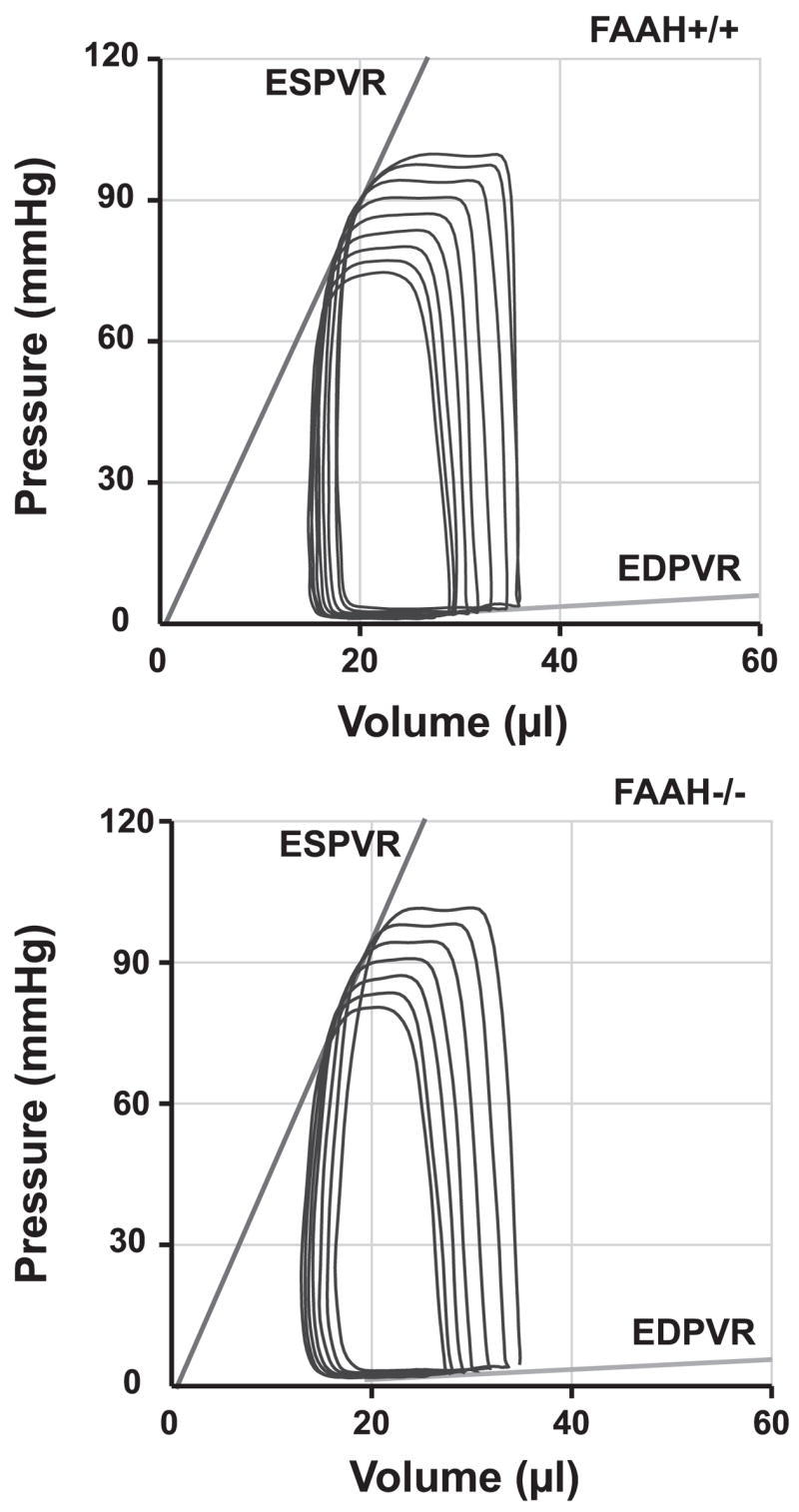

Fig. 1.

Representative pressure-volume relations following inferior vena cava occlusions in FAAH+/+ and FAAH−/− mice. Note that the slopes of end-systolic and end-diastolic pressure-volume (P-V) relations (ESPVR and ED-PVR), indicators of left ventricular (LV) contractility and stiffness, respectively, are similar in the two strains.

Calibrations

The volume calibration of this conductance system was performed as previously described (38, 39). Briefly, seven cylindrical holes in a block 1 cm deep and with known diameter ranging from 1.4 to 5 mm were filled with fresh heparinized whole murine blood. An interelectrode distance of 4.5 mm was used to calculate the absolute volume in each cylinder. In this calibration, the linear regression between the absolute volume in each cylinder versus the raw signal acquired by the conductance catheter was used as the volume calibration formula. At the end of each experiment, 10 μl of 15% saline were injected intravenously, and, from the shift of P-V relation, parallel conductance volume was calculated by PVAN 3.2 and used for correction for the cardiac mass volume as previously described (38, 39).

Blood pressure measurements in conscious animals

Arterial blood pressure in unanesthetized mice was measured by the tail-cuff method using a XBP1000 Computerized Mouse Tail Blood Pressure System (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Mice were restrained, and temperature was controlled at 37°C. After blood pressure readings stabilized, 10 –12 additional consecutive readings were averaged.

Determination of baroreflex sensitivity

Baroreflex sensitivity was determined by using the phenylephrine (PE) method of Coleman (6). Bolus doses (3–100 μg/kg) of PE were injected intravenously at random sequence. The peak increase in mean blood pressure were then plotted against the corresponding peak increase in pulse period (1/HR), and the slope (in ms/mmHg) obtained by regression analysis of the linear component of the curve was taken as an indicator of baroreflex sensitivity.

Western blot analysis

Frozen myocardial tissue from FAAH+/+ and FAAH−/− mice were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mmol/l Tris, pH 7.5; 1% Nonidet P-40; 0.25% sodium deoxycholate; 150 mmol/l NaCl; 1 mmol/l each of EDTA; phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; and sodium orthovanadate; and 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin). One hundred micrograms of lysate protein were size fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transblotted to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blot analysis, with rabbit anti-human CB1 polyclonal antibody at 5 μg/ml, was done as described previously (2). Immunoreactive bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (Amersham Pharmacia) and quantified by densitometry.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from hearts using TRIzol, and the RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Amplification of CB1 mRNA using RT-PCR was done as previously described (35).

Measurement of endocannabinoid levels

Myocardial levels of AEA, 2-AG, 1-AG, and N-oleoylethanolamine (OEA) were quantified by liquid chromatography/in-line mass spectrometry, as previously described (2). Values are expressed as femtomoles or picomoles per milligram of wet tissue.

Drugs

AEA and AM-251 were from Tocris (Baldwin, MO); PE was from Sigma. HU-210 was from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Research Triangle Park, NC). AEA, AM-251, and HU-210 were emulsified in corn oil-water (1:4) as described (2).

Statistical analyses

Strain- and time-dependent variables were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Student’s t-test was used after ANOVA for pair-wise comparisons using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA). Significance was assumed if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Hemodynamic profile of FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice

Baseline cardiovascular parameters (MAP, LV systolic pressure, LVEDP, Ea, +dP/dt, −dP/dt, HR, EF, τ, SV, SW, CO, and TPR) were not significantly different in anesthetized FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice (Table 1). Figure 1 illustrates typical P-V loops obtained after IVC occlusions in both strains. Note that the slopes of systolic and diastolic P-V relations (ESPVR and EDPVR) are similar in FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice (Fig. 1). The load-independent indexes of contractility and LV stiffness (Emax, dP/dt-EDV, PRSW, and EDPVR) were also similar in the two strains and are summarized in Table 1. Consistently with the above-described results in anesthetized mice, systolic blood pressure measured in unanesthetized animals was also similar in conscious FAAH+/+ (90.9 ± 2.2 mmHg, n = 5) and FAAH−/− mice (89.5 ± 1.8 mmHg, n = 7).

Increased sensitivity to the hypotensive and cardiodepressant effects of AEA in FAAH−/− versus FAAH+/+ mice

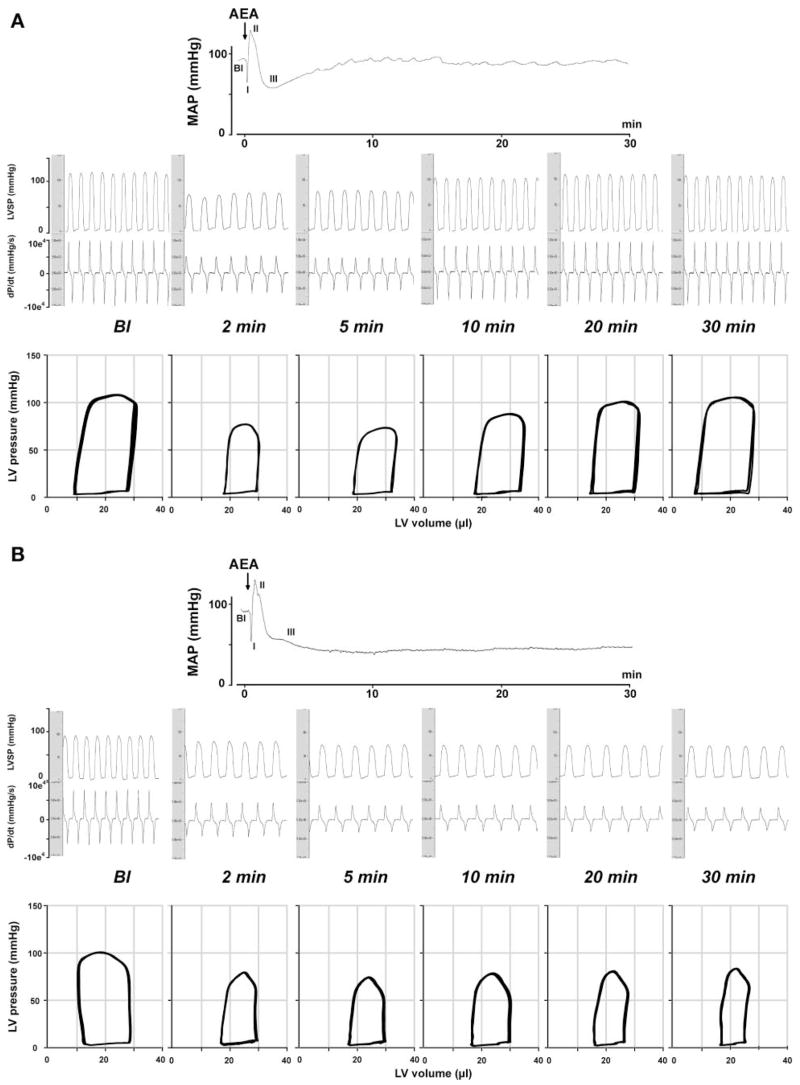

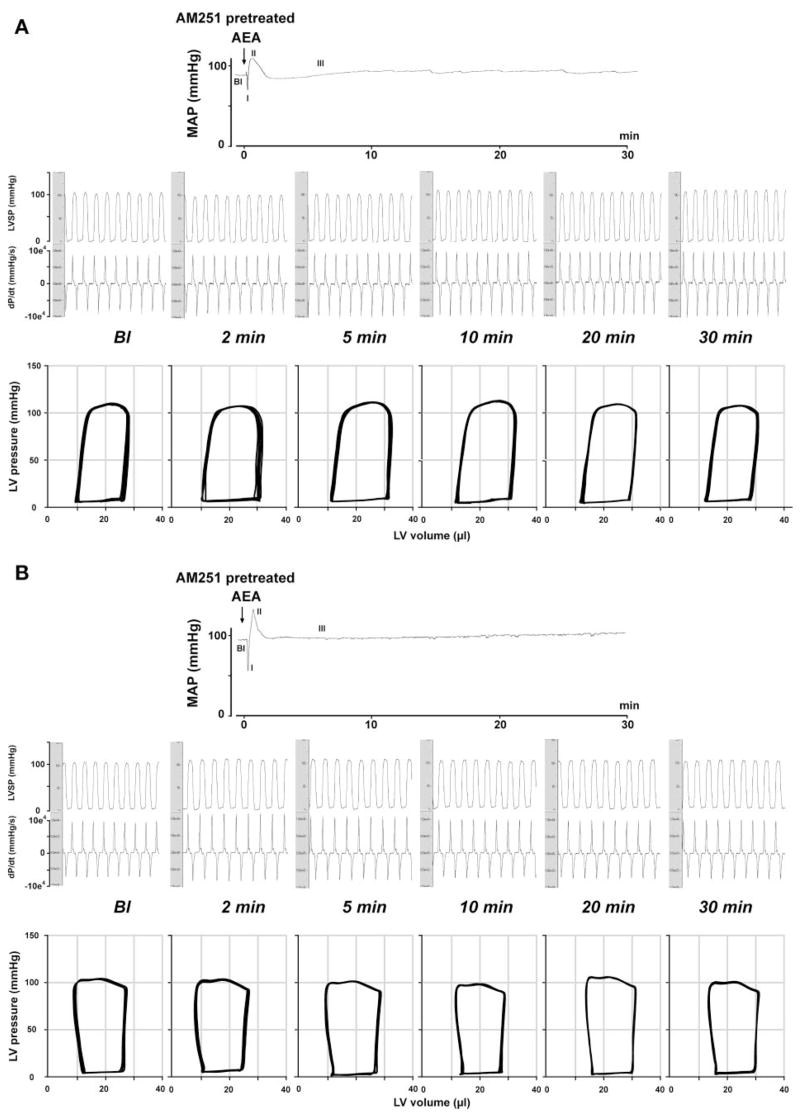

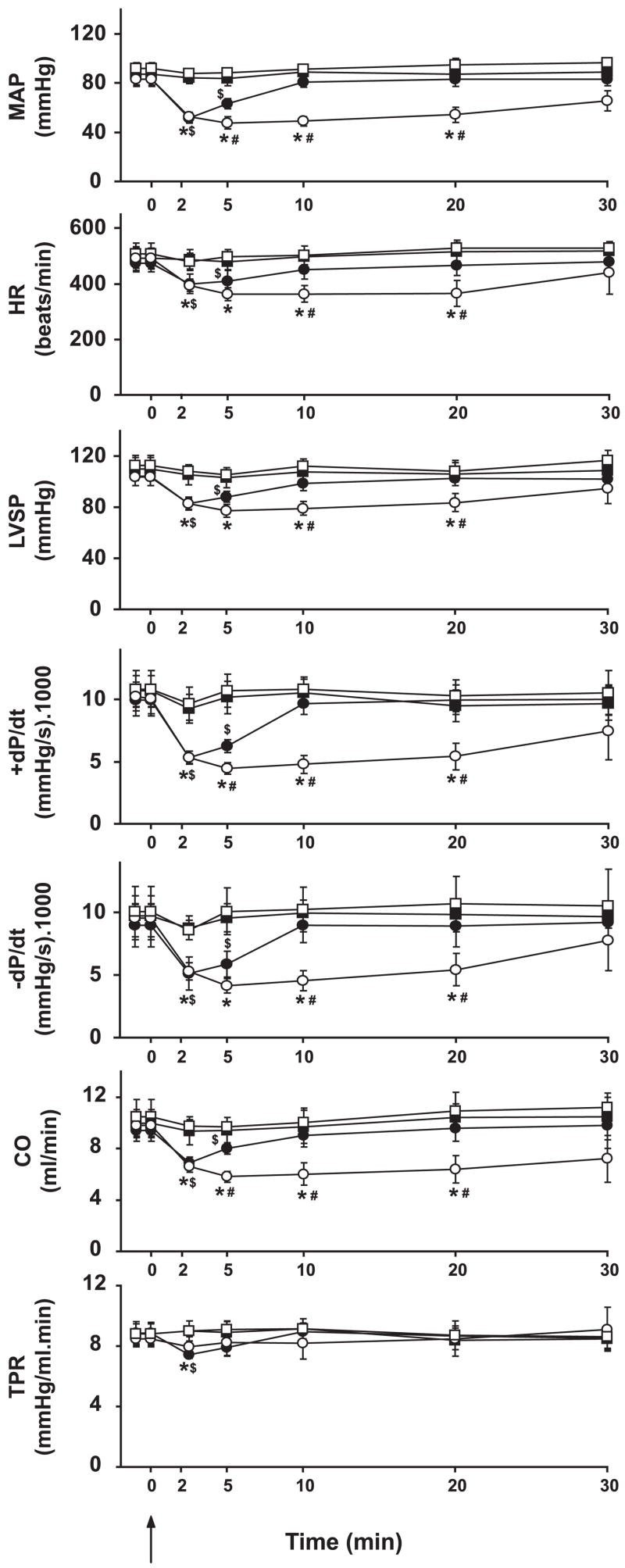

Bolus injections of AEA (20 mg/kg iv) caused a triphasic effect in FAAH+/+ mice (Figs. 2 and 3, see the MAP trace). The transient first phase that lasted a few seconds was characterized by profound decreases in cardiac contractility and HR, followed by a brief pressor response (second phase) associated with increased cardiac contractility. The third hypotensive phase was characterized by decreased cardiac contractility and a slight decrease in TPR, which lasted up to 5–10 min (Figs. 2, 3, and 5). Pretreatment of the mice with the CB1 antagonist AM-251 (3 mg/kg iv) did not affect baseline cardiovascular parameters. AM-251 had no effect on the first and second phases of the response to AEA but completely prevented the subsequent hypotension and the associated decreases in cardiac contractility (Figs. 2, 3, and 5). The AEA-induced hypotension and bradycardia were dose dependent (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 2.

Hemodynamic effects of anandamide (AEA) in FAAH+/+ (A) and FAAH−/− (B) mice. Representative recordings of the effect of intravenous injection of AEA (20 mg/kg) on mean arterial pressure (MAP, top), cardiac contractility [LV systolic pressure (LVSP) and pressure change over time (dP/dt); middle], and P-V relations (bottom) in an anesthetized FAAH+/+ (A) and FAAH−/− (B) mouse are shown. The six parts in the middle and bottom represent baseline conditions (Bl) and responses 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min after injection of AEA. Arrows indicate the injection of the drug. Note that the hypotensive and cardiodepressant effects of AEA (phase III) last much longer in FAAH−/−(> 30 min) than in FAAH+/+ mice (<10 min).

Fig. 3.

Phase III hemodynamic effects of AEA are mediated by cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors in both FAAH+/+ (A) and FAAH−/− (B) mice. Representative recordings of the effects of AEA (20 mg/kg iv) after pretreatment with the CB1 antagonist AM-251 (3 mg/kg iv) on MAP (top), cardiac contractility (LVSP and dP/dt; middle), and P-V relations (bottom) in a FAAH+/+ (A) and a FAAH−/− mouse (B) are shown. The six parts in the middle and bottom panels represent baseline conditions and responses 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min after injection of AEA. Arrows indicate the injection of the drugs.

Fig. 5.

Hemodynamic effects of AEA in FAAH+/+ (solid symbols) and FAAH−/− mice (open symbols) after vehicle (circles) or AM-251 treatment (squares). Values are means ± SE; n = 5–7 mice for each condition. AEA was injected at 0 min, as indicated by arrow. Note that AM-251 blocks the major hemodynamic effects of AEA in both strains. Strain- and time-dependent differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Student’s t-test was used after ANOVA for pairwise comparisons. Significance was assumed if P < 0.05 for FAAH+/+ pre- vs. posttreatment (*), for FAAH+/+ pre- vs. posttreatment ($), and for FAAH−/− vs. FAAH+/+ (#). LVSP, LV systolic pressure; +dP/dt and −dP/dt, pressure increment and decrement, respectively; CO, cardiac output; TPR, total peripheral resistance.

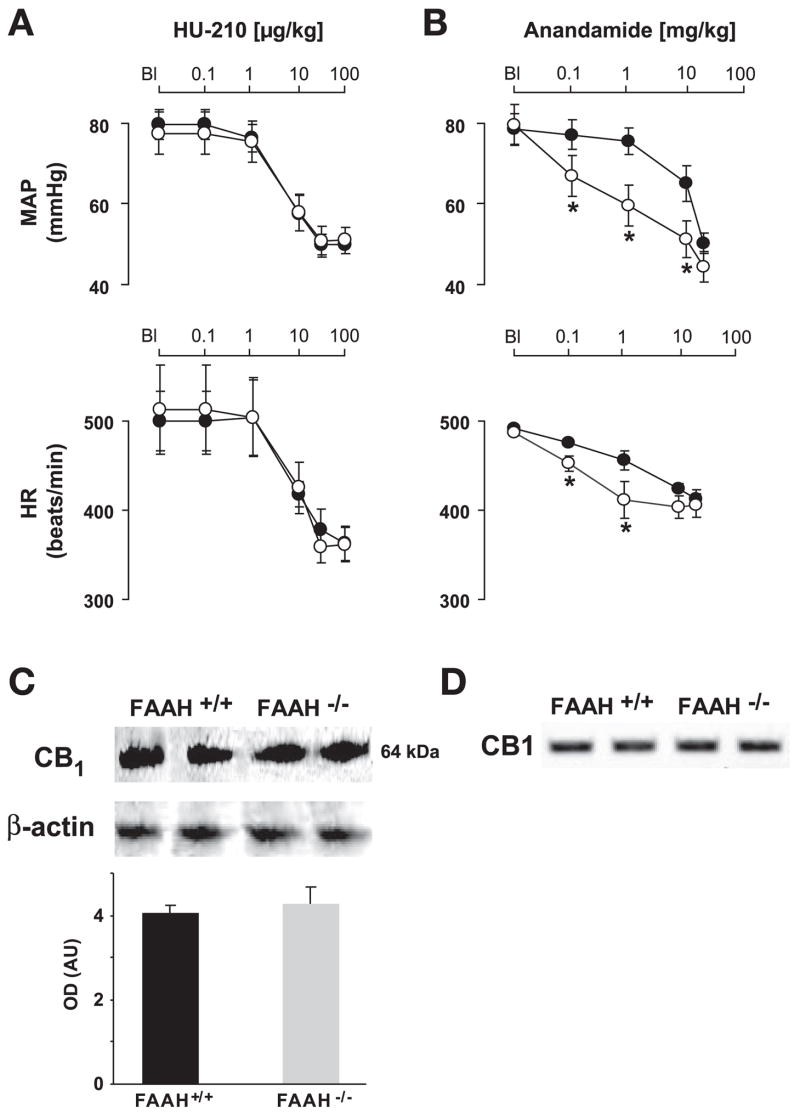

Fig. 4.

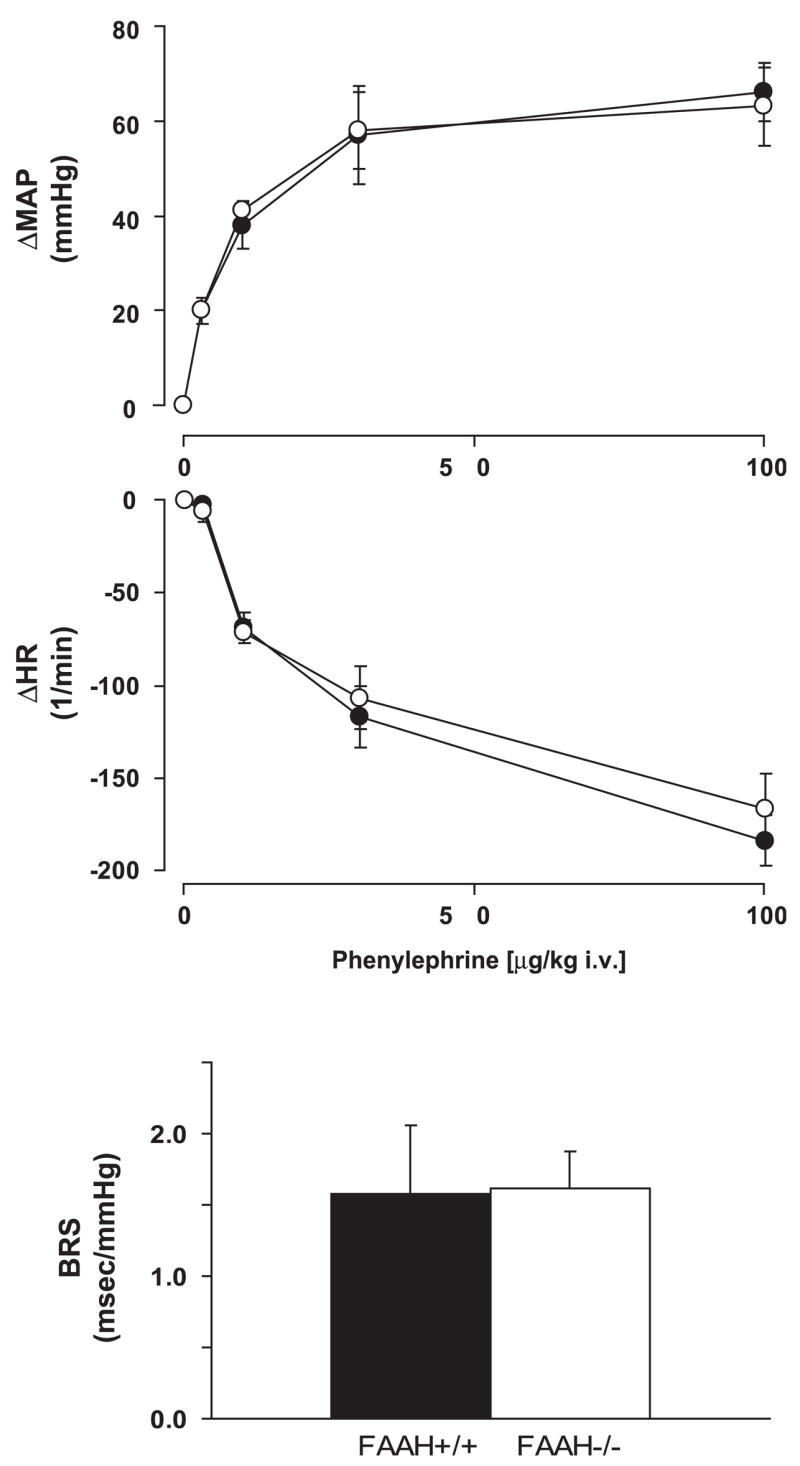

A: dose-dependent effects of HU-210 on MAP and heart rate (HR) in FAAH+/+ (●) and FAAH−/− mice (○). Note that the effects of HU-210 are similar in the two strains. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 mice for each condition. B: dose-dependent effects of AEA on MAP and HR in FAAH+/+ (●) and FAAH−/− mice (○). Note the increased sensitivity of FAAH−/− mice to the effects of AEA. Values are means ± SE; n = 4 –7 mice for each condition. Student’s t-test was used for pairwise comparisons. *P < 0.05, FAAH−/− vs. FAAH+/+. C and D: detection of cardiac CB1 receptors by Western blot analysis(C) or RT-PCR (D) in FAAH+/+ and FAAH−/− mice. Optical density (OD) values for Western blot analyses are means ± SE from 5 separate experiments and have been corrected for loading. AU, arbitrary units.

In FAAH−/− mice, phases I and II of the AEA response were similar to corresponding responses in FAAH+/+ littermates (see mean blood pressure traces in Figs. 2 and 3). The subsequent hypotensive response accompanied by decreased cardiac contractility and TPR (phase III) was more prolonged in FAAH−/− than in FAAH+/+ mice, and these effects were completely antagonized by pretreatment with AM-251 (Figs. 2, 3, and 5), which, similar to FAAH+/+ mice, did not affect baseline cardiovascular parameters. The increased sensitivity of FAAH−/− to AEA also manifested in a leftward shift of the dose-response relationship for the hypotensive and bradycardic effects of AEA compared with FAAH+/+ littermates (Fig. 4B).

Effect of HU-210 on MAP and HR

HU-210 is a potent synthetic synthetic CB1 agonist, which is not a substrate of FAAH. In FAAH+/+ mice, HU-210 (0.01–100 μg/kg iv) evoked dose-dependent decreases in blood pressure and HR, similar to phase III responses to AEA (Fig. 4A). In contrast to the AEA-induced response, the hemodynamic effects of HU-210 were not different in FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice (Fig. 4A).

Myocardial endocannabinoid levels

The AEA and OEA content of the myocardium was significantly higher in FAAH−/− compared with FAAH+/+ mice (Table 2) with no difference in 1-AG and 2-AG contents.

Table 2.

Myocardial endocannabinoid content in FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice

| n | AEA, fmol/mg | 2-AG, pmol/mg | 1-AG, pmol/mg | OEA, pmol/ mg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAAH+/+ | 6 | 7.68 ± 1.29 | 3.61 ± 0.44 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| FAAH−/− | 8 | 18.83 ± 1.96 | 4.45 ± 0.83 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| P value | 0.0009 | 0.43 | 0.15 | < 0.0001 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of experiments. AEA, N-arachidonyleth-anolamine; 2-AG, 2-arachidonylglycerol; 1-AG, 1-arachidonylglyerol; DEA, N-oleoylethanolamine. Student’s t-test was used for pairwise comparisons.

Myocardial CB1 receptors

The expression of CB1 in the heart, analyzed by Western blot analysis and RT-PCR, showed no significant difference between FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice (Fig. 4, C and D).

Baroreflex sensitivity

Activation of CB1 by AEA in the nucleus tractus solitarius has been shown to facilitate the baroreflex (41). We therefore looked for tonic activity of this system by comparing baroreflex sensitivity in FAAH+/+ and FAAH−/− mice. The dose-dependent pressor effects of PE, as well as the reflex-mediated bradycardia, were similar in FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice, and, as a result, there was no difference in basal baroreflex sensitivity between the two strains (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Pressor (top) and reflex bradycardic responses to phenylephrine (middle) and baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) (bottom) in anesthetized FAAH+/+ (●) and FAAH−/− mice (○). Baroreflex sensitivity was determined as described in METHODS. Values are means ± SE; n = 4 – 6 mice for each condition.

DISCUSSION

We characterized, for the first time, the cardiovascular profile of mice lacking FAAH and documented their increased sensitivity to the cardiovascular depressant effects of AEA using the Millar P-V conductance catheter system. We also show that FAAH−/− mice have normal cardiac function, blood pressure, and baroreflex sensitivity despite the increased levels of AEA and OEA in the myocardium of these animals.

Shortly after the discovery of AEA (14), the existence of an AEA-hydrolyzing enzyme was described by several groups (13, 16, 20, 42). This enzyme was purified and cloned (8, 11), and FAAH knockout mice were developed (7). Mice lacking FAAH possess high endogenous concentrations of AEA and related fatty acid amides in the brain that correlate with increased CB1-dependent hypoalgesia in these animals as well as a marked increase in the cannabinoid-like behavioral responses to exogenous AEA (7). In a subsequent study, treatment of mice with a potent FAAH inhibitor in vivo elicited similar, CB1-mediated hypoalgesia as well as a reduction of anxiety, which could be reversed by CB1 blockade (22). Neither blockade nor genetic ablation of FAAH altered locomotion or core body temperature functions also regulated by CB1 (7, 22). This selectivity in the appearance of an endocannabinergic tone for some but not other cannabinoid-regulated behaviors suggests that FAAH may represent an attractive therapeutic target for treating pain and related neurological disorders, as well as anxiety, without the abuse potential of direct acting CB1 agonists (10, 15, 17, 37). Recently, a number of potent FAAH inhibitors have entered into various phases of preclinical development for therapeutic indications (3, 33). There is also evidence that modifying central versus peripheral FAAH activity affects different physiological processes and may be targeted with appropriate selective inhibitors for distinct therapeutic effects (12).

In this study we provide evidence that mice lacking FAAH have normal blood pressure and cardiac contractility (Table 1), and these cardiovascular parameters remain unaffected by CB1 blockade in both strains. This suggests that, under normal physiological conditions, the absence of FAAH does not lead to the appearance of an endocannabinergic tone on the cardiovascular system. These results are also in agreement with our recent findings that the FAAH inhibitor URB-597 had no detectable hemodynamic effects in normotensive rats (2). Baroreflex sensitivity was also normal in FAAH−/− mice, which is in agreement with the reported lack of effect on baroreflex sensitivity of intranucleus tractus solitarius micro-injection of the CB1 antagonist SR-141716 (40). These findings are very important from the point of the development of future FAAH inhibitors, because such compounds are unlikely to cause untoward cardiovascular side effects, such as orthostatic hypotension, in normotensive individuals. Importantly, in the same study, we demonstrated that URB-597 decreased blood pressure, cardiac contractility, and TPR to normotensive levels in rats with three different forms of hypertension, whereas CB1 blockade caused opposite changes (2). The hemodynamic effects of URB-597 in hypertensive rats were CB1 mediated and were remarkably similar to those of exogenous AEA (2), which causes only a short-lasting modest decrease in blood pressure and cardiac contractility in normotensive rats and much longer lasting and pronounced effects in hypertensive animals (2, 24). These findings were interpreted to indicate that hypertension activates a compensatory hypotensive and cardiodepressor tone mediated by endocannabinoids acting at CB1, which may be exploited for the treatment of hypertension.

In addition to enzymatic hydrolysis, endocannabinoids are also susceptible to oxidative metabolism by a number of fatty acid oxygenases (e.g., cyclooxygenase, lipooxygenase, and cytochrome P-450) (reviewed in Refs. 5 and 30), and some of these metabolites are potent cardiovascular modulators (18). The effects of knocking out or inhibiting FAAH may thus be confounded by the activation of such alternative pathways of AEA metabolism, particularly in the cardiovascular system, a possibility that needs to be explored. To the extent that the activity of such FAAH-independent pathways of AEA metabolism are tissue dependent, they may also contribute to the variability in the degree of increase in AEA content in different tissues of FAAH−/− mice (see below).

In anesthetized rats and mice, intravenous administration of AEA causes a triphasic blood pressure response, in which a prolonged hypotensive effect (phase III) is preceded by a transient, vagally mediated fall in HR and blood pressure (phase I) followed by a brief, nonsympathetically mediated pressor response (phase II) (23, 38, 43). Inhibition of the phase I bradycardic response by vanilloid TRPV1 receptor antagonist (29) and the absence of both phase I and II responses in TRPV1−/−mice (38) indicates that these components of the AEA response are mediated by TRPV1 receptors. On the other hand, the phase III hypotension and decreased cardiac contractility can be abolished by CB1 antagonists (2, 29, 38, 43) and are absent in CB1−/− mice (21, 25), indicating their exclusive mediation by CB1 and not TRPV1 receptors.

In the present study, the triphasic hemodynamic response to AEA (20 mg/kg iv) in wild-type mice was similar to that reported in earlier studies. In FAAH−/− mice, the CB1-mediated hypotension and decreased cardiac contractility were more prolonged than in controls, and the AEA dose-response curve was shifted to the left (Figs. 2, 3, and 5), which likely reflect the absence of rapid inactivation of exogenous AEA by various tissues (7, 12), including the myocardium. This is also indicated by the elevated levels of endogenous AEA in the myocardium of FAAH−/− compared with FAAH+/+ mice (Table 2). Brain levels of AEA were reported to be about 15-fold higher in FAAH−/− than in FAAH+/+ mice (7), and we found similar differences using tissue from the same colony that was used for the present study (unpublished observations). The smaller difference detected in the heart could reflect the much lower level of expression of FAAH in the heart than in the brain (12) and/or differential activation of FAAH-independent pathways of AEA metabolism (see above).

Altered sensitivity of myocardial CB1 is unlikely to contribute to the increased cardiodepressant and hypotensive effects of AEA. First, myocardial CB1 expression as verified by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis was similar in the two strains (Fig. 4, C and D). Second, sensitivity to the hypotensive and bradycardic effects of the synthetic cannabinoid agonist HU-210, which is not a substrate of FAAH, was also similar in FAAH−/− and FAAH+/+ mice (Fig. 4A). For this reason, it is also unlikely that global changes in vascular CB1 could account for the increased sensitivity to the hemodynamic effects of AEA in FAAH−/− mice (see Fig. 5 and DISCUSSION above), although localized changes in vascular CB1 receptors cannot be ruled out.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that FAAH−/− mice exhibit increased sensitivity to the CB1-mediated hypotensive and cardiodepressant effects of AEA, and the decreased degradation of AEA rather than altered target organ sensitivity appears to be the underlying mechanism. Furthermore, FAAH−/− mice have normal blood pressure, cardiac function, and baroreflex sensitivity and show no evidence for an endocannabinergic tone affecting blood pressure and cardiac contractility. In view of our earlier findings of such a tone in hypertensive rats, it remains to be determined whether FAAH−/− display resistance to different forms of experimental hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Authors are indebted to Millar Instruments for the excellent technical support.

References

- 1.Bátkai S, Pacher P, Járai Z, Wagner JA, Kunos G. Cannabinoid antagonist SR-141716 inhibits endotoxic hypotension by a cardiac mechanism not involving CB1 or CB2 receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H595–H600. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00184.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bátkai S, Pacher P, Osei-Hyiaman D, Radaeva S, Liu J, Harvey-White J, Offertáler L, Mackie K, Rudd A, Bukoski RD, Kunos G. Endocannabinoids acting at CB1 receptors regulate cardiovascular function in hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110:1996 –2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143230.23252.D2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boger DL, Sato H, Lerner AE, Hedrick MP, Fecik RA, Miyauchi H, Wilkie GD, Austin BJ, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Exceptionally potent inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase: the enzyme responsible for degradation of endogenous oleamide and anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5044 –5049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonz A, Laser M, Kullmer S, Kniesch S, Babin-Ebell J, Popp V, Ertl G, Wagner JA. Cannabinoids acting on CB1 receptors decrease contractile performance in human atrial muscle. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:657– 664. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200304000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein SH, Rossetti RG, Yagen B, Zurier RB. Oxidative metabolism of anandamide. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2000;61:29 – 41. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(00)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman TG. Arterial baroreflex control of heart rate in the conscious rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1980;238:H515–H520. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.4.H515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9371–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83– 87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. Fatty acid amide hydrolase: an emerging therapeutic target in the endocannabinoid system. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:469 – 475. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. The endogenous cannabinoid system and its role in nociceptive behavior. J Neurobiol. 2004;61:149 –160. doi: 10.1002/neu.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cravatt BF, Prospero-Garcia O, Siuzdak G, Gilula NB, Henriksen SJ, Boger DL, Lerner RA. Chemical characterization of a family of brain lipids that induce sleep. Science. 1995;268:1506 –1509. doi: 10.1126/science.7770779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cravatt BF, Saghatelian A, Hawkins EG, Clement AB, Bracey MH, Lichtman AH. Functional disassociation of the central and peripheral fatty acid amide signaling systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10821–10826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401292101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsch DG, Chin SA. Enzymatic synthesis and degradation of anandamide, a cannabinoid receptor agonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:791–796. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90486-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946 –1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Marzo V, Bifulco M, De Petrocellis L. The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:771–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Marzo V, Fontana A, Cadas H, Schinelli S, Cimino G, Schwartz JC, Piomelli D. Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature. 1994;372:686 – 691. doi: 10.1038/372686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaetani S, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Anandamide hydrolysis: a new target for anti-anxiety drugs? Trends Mol Med. 2003;9:474 – 478. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauthier KM, Baewer DV, Hittner S, Hillard CJ, Nithipatikom K, Reddy DS, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Endothelium-derived 2-arachidonoylglycerol; an intermediate in vasodilatory eicosanoid release in bovine coronary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1344 –H1351. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00537.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebremedhin D, Lange AR, Campbell WB, Hillard CJ, Harder DR. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor of cat cerebral arterial muscle functions to inhibit L-type Ca2+ channel current. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H2085–H2093. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hillard CJ, Wilkison DM, Edgemond WS, Campbell WB. Characterization of the kinetics and distribution of N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) hydrolysis by rat brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1257:249 –256. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00087-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Járai Z, Wagner JA, Varga K, Lake KD, Compton DR, Martin BR, Zimmer AM, Bonner TI, Buckley NE, Mezey E, Razdan RK, Zimmer A, Kunos G. Cannabinoid-induced mesenteric vasodilation through an endothelial site distinct from CB1 or CB2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14136 –14141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valino F, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, La Rana G, Calignano A, Giustino A, Tattoli M, Palmery M, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9:76 – 81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lake KD, Martin BR, Kunos G, Varga K. Cardiovascular effects of anandamide in anesthetized and conscious normotensive and hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;29:1204 –1210. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.5.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lake KD, Compton DR, Varga K, Martin BR, Kunos G. Cannabinoid-induced hypotension and bradycardia in rats is mediated by CB1-like cannabinoiod receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:1030 –1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ledent C, Valverde O, Cossu G, Petitet F, Aubert JF, Beslot F, Bohme GA, Imperato A, Pedrazzini T, Roques BP, Vassart G, Fratta W, Parmentier M. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401– 404. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Kaminski NE, Wang DH. Anandamide-induced depressor effect in spontaneously hypertensive rats: role of the vanilloid receptor. Hypertension. 2003;41:757–762. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000051641.58674.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Bátkai S, Pacher P, Harvey-White J, Wagner JA, Cravatt BF, Gao B, Kunos G. LPS induces anandamide synthesis in macrophages via CD14/MAPK/PI3K/NF-κB independently of platelet activating factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45034 – 45039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Gao B, Mirshahi F, Sanyal AJ, Khanolkar AD, Makriyannis A, Kunos G. Functional CB1 cannabinoid receptors in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem J. 2000;346:835– 840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malinowska B, Kwolek G, Gothert M. Anandamide and methanandamide induce both vanilloid VR1- and cannabinoids CB1 receptor-mediated changes in heart rate and blood pressure in anaesthetized rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:562–569. doi: 10.1007/s00210-001-0498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matias I, Chen J, De Petrocellis L, Bisogno T, Ligresti A, Fezza F, Krauss AH, Shi L, Protzman CE, Li C, Liang Y, Nieves AL, Kedzie KM, Burk RM, Di Marzo V, Woodward DF. Prostaglandin ethanolamides (prostamides): in vitro pharmacology and metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:745–757. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young CA, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mechoulam R, Fride E, Di Marzo V. Endocannabionoids. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;359:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mor M, Rivara S, Lodola A, Plazzi PV, Tarzia G, Duranti A, Tontini A, Piersanti G, Kathuria S, Piomelli D. Cyclohexylcarbamic acid 3′- or 4′-substituted biphenyl-3-yl esters as fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitors: synthesis, quantitative structure-activity relationships, and molecular modeling studies. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4998 –5008. doi: 10.1021/jm031140x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61– 65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osei-Hyiaman D, Depetrillo M, Pacher P, Liu J, Radaeva S, Bátkai S, Harvey-White J, Mackie K, Offertaler L, Wang L, Kunos G. Endocannabinoid action at hepatic CB1 receptors regulates fatty acid synthesis: role in diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1298–1305. doi: 10.1172/JCI23057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G. Cannabinoids and cardiovascular pharmacology. In: Pertwee RG, editor. Cannabinoids Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 168. Dordrecht, Germany: Springer; 2005. pp. 584–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G. Blood pressure regulation by endocannabinoids and their receptors. Neuropharmacology. 48:1130–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G. Haemodynamic profile and responsiveness to anandamide of TRPV1 receptor knock-out mice. J Physiol. 2004;558:647– 657. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pacher P, Liaudet L, Bai P, Mabley JG, Kaminski PM, Virág L, Deb A, Szabo E, Ungvári Z, Wolin MS, Groves JT, Szabo C. Potent metalloporphyrin peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst protects against the development of doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;107:896 –904. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048192.52098.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rademacher DJ, Patel S, Hopp FA, Dean C, Hillard CJ, Seagard JL. Microinjection of a cannabinoid receptor antagonist into the NTS increases baroreflex duration in dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1570 –H1576. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00772.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seagard JL, Dean C, Patel S, Rademacher DJ, Hopp FA, Schmeling WT, Hillard CJ. Anandamide content and interaction of endocannabinoid/GABA modulatory effects in the NTS on baroreflex-evoked sympathoinhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H992–H1000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00870.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ueda N, Kurahashi Y, Yamamoto S, Tokunaga T. Partial purification and characterization of the porcine brain enzyme hydrolyzing and synthesizing anandamide. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23823–23827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varga K, Lake K, Martin BR, Kunos G. Novel antagonist implicates the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in the hypotensive action of anandamide. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;278:279 –283. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00181-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varga K, Wagner JA, Bridgen DT, Kunos G. Platelet- and macrophage-derived endogenous cannabinoids are involved in endotoxin-induced hypotension. FASEB J. 1998;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.11.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner JA, Hu K, Bauersachs J, Karcher J, Wiesler M, Goparaju SK, Kunos G, Ertl G. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate hypotension after experimental myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2048 –2054. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner JA, Járai Z, Bátkai S, Kunos G. Hemodynamic effects of cannabinoids: coronary and cerebral vasodilation mediated by cannabinoid CB(1) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;423:203–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner JA, Varga K, Ellis EF, Rzigalinski BA, Martin BR, Kunos G. Activation of peripheral CB1 cannabinoid receptors in haemorrhagic shock. Nature. 1997;390:518 –521. doi: 10.1038/37371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]