Abstract

Background. Choledochal cysts are dilations of the biliary tree. Although commonly reported in Asian populations, the incidence outside of Asia is as low as 1:150 000. The largest series of patients with choledochal cyst disease outside of Asia is this one, studying 70 patients treated in Vancouver between 1971 and 2003. Patients and methods. This was a retrospective chart review. Results. In all, 19 paediatric and 51 adult patients were evaluated; 21% of paediatric and 25% of adult patients were Asian. All paediatric patients had type I or IV cysts, whereas adult patients represented the different subtypes. Abdominal pain was the presenting symptom in 79% of children and 88% of adults, vomiting was present in 42% of children and 63% of adults and jaundice was seen in 31.5% of children and 39% of adults. Ultrasound was used in 94.7% of children, and ERCP in 80% of adults. In all, 84% of paediatric patients, 100% of adult patients with type I cysts and 85.7% of adult patients with type IV cysts received complete cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Complications in both groups were low. Conclusions. Although Vancouver does have a large Asian population, this does not explain how common choledochal cysts are in this city. Alhough some authors argue that paediatric and adult disease are caused by different aetiologies, presentation patterns in our study between the two groups were very similar. We recommend complete cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy as the surgery of choice, and advocate early surgery after diagnosis to promote ease of surgery and prevention of future complications.

Keywords: Choledochal cysts, biliary disease, surgery, Caroli's disease, cholangiocarcinoma

Introduction

Choledochal cyst disease (CC) is a rare entity that encompasses cystic dilations at various parts of the biliary tree. Its incidence, although as high as 1:1000 in Asian populations, is only 1:100 000 to 1:150 000 in western populations 1,2,3. Vancouver, British Columbia, as outlined by this analysis, in fact has the largest series of choledochal cysts outside of Asia. The reason for this geographic distribution is yet unknown. Other mysteries of this disease entity include its aetiology, adequate classification system, ideal diagnostic modality and natural course. Disease patterns across various ages may help in elucidating the pathophysiology and natural course of biliary cystic disease. We analysed the patients seen at the University of British Columbia, and compared the characteristics among pediatric and adult patients in an attempt to unravel some of these mysteries.

Patients and methods

This is a retrospective analysis of CC in paediatric patients seen at British Columbia Children's Hospital between 1971 and 2003, as well as a comparison of these patients with adult patients seen at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre between 1985 and 2002. All the paediatric patients were <16 years of age. Charts were reviewed and data collected concerning patient demographics, presenting symptoms, co-existing disease, diagnostic modalities used, biochemical aberrations, surgical strategy, complications and pathological findings.

Results

Nineteen pediatric patients were diagnosed with CC at the British Columbia Children's Hospital between 1971 and 2003, and 51 adult patients were identified at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre. The resultant total of 70 patients is the largest studied within a non-Asian population. The age range among the paediatric patients ran from 1 day to 16 years, with the mean age being 5 years. Four of these (21%) were less than 1 year old. Of the children, 89% were female and 11% were male, whereas in the adult group 80% were female and 20% were male. Only 21% of paediatric patients were of Asian descent, with 89% being Caucasian; 25% of adults were Asian, and 75% were Caucasian.

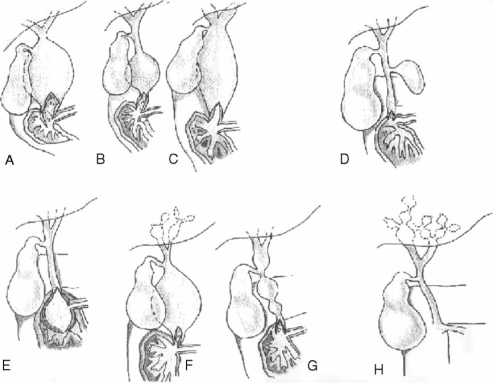

The different types of choledochal cysts as per Todani's classification (Figure 1) were quite limited in the paediatric group. In all, 13 patients (68%) had type I cysts and 6 (31.5%) had type IVa. In the adult group, 17 (33%) had type I, 3 (6%) type II, 1 (1.9%) type III, 28 (54.8%) type IVa and 2 (3.9%) type V.

Figure 1. .

Choledochal cyst classification. (A) Type Ia – dilatation of extrahepatic duct. (B) Type Ib – discrete segmental dilation of extrahepatic duct. (C) Type Ic – fusiform dilation of entire choledochus. (D) Type II – diverticula of choledochus. (E) Type III cyst/choledochocele – distal dilation of choledochus within duodenal wall. (F) Type IVa – combined intrahepatic and extrahepatic duct cysts. (G) Type IVb – multiple extrahepatic bile duct cysts. (H) Type V/Caroli's disease – multiple intrahepatic bile duct cysts.

Fifteen (79%) of the children presented with abdominal pain, eight (42%) with nausea and vomiting, six (31.5%) with jaundice, three (15.8%) with a palpable mass and anorexia, and two (10.5%) with pruritus and weight loss. Only two patients presented with the classic triad of pain, jaundice and a palpable mass, and both were over the age of 1. A total of 45 (88%) adults presented with abdominal pain, 31 (63%) with nausea and vomiting, 20 (39%) with jaundice and 20 (39%) with fever. None of the adult patients presented with the classic triad. Related comorbid illness in children included five (26%) with cholecystitis, four (21%) with pancreatitis, three (15.8%) with cholesterolosis, two (10.5%) with kidney malformation and one each (5%) of ventriculoseptal defect and malrotation. Among the adults, 19 (37%) had recurrent cholangitis and 6 (11%) had pancreatitis.

Ultrasound was used in the diagnosis of 18 (94.7%) paediatric patients, 3 of which were prenatal. Three (15.7%) had computerized tomography (CT) scans, three hydroxyiminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scans, two (10.5%) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatograms (ERCP), two magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and one (5%) intravenous cholangiogram. Thirteen (68%) had intraoperative cholangiograms. ERCP was the modality of choice in adults, being used in 40 (80%) patients. Also, 36 (75%) had ultrasounds, 21 (43%) CT scans and 10 (21%) had percutaneous transhepatic cholangiograms (PTC).

Cyst excision, cholecystectomy and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy were performed in the majority of paediatric patients (84%). Three patients underwent cyst excision and choledochojejunostomy, two of which were before 1980. Duration of surgery ranged between 140 and 340 min, with mean surgical time being 220±50 min. Length of hospital stay widely varied between 4 and 50 days, with a mean stay of 11.5 days. Within 2 weeks of surgery, three (15.8%) patients had early complications of fever, two (10.5%) had pain and vomiting, and one (5%) had a bile leak. Late complications included wound infection and persistent bile leak (one each). The surgery performed in the adult patients appropriately depended on the type of cyst involved: 100% of type I and 85.7% (24/28) of type IVa cysts received cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Three of these patients required subsequent segmental hepatic resection secondary to cholangiocarcinoma. The other four type IVA patients did not undergo a complete cyst excision due to extension of the cyst into the pancreatic head (two of four) or severe fibrosis and adhesions. Two of three type II cysts had simple excision, whereas one had complete bile duct excision, pancreatic head excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy due to an associated cholangiocarcinoma. The type III cyst was treated initially with a sphincterotomy, but required subsequent resection of the ampulla of Vater and reconstruction of the pancreatic and common bile ducts due to recurrent pancreatitis. Both type V patients received segmental hepatic resection, but one subsequently also received an orthotopic liver transplant due to recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, secondary biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Eleven of all adult patients had previous cystenterostomies, three of whom required invasive treatment for complications. Six surgeries (12%) were complicated by anastamotic strictures, two of which had type I cysts and four had type IVA. Of these patients who developed anastomotic strictures, two had undergone previous cystenterostomies. Four patients were diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma. Three patients had recurrent cholangitis that was successfully treated with PTC.

Discussion

As described previously, there is a great Asian preponderance of choledochal cyst disease 1,2,3. Given that the biggest series outside of Asia is the present one, we wondered whether our prevalence was secondary to the large Asian population in Vancouver, British Columbia. Contradicting this hypothesis, however, is the fact that only 21% of paediatric and 25% of adult patients in our study were Asian. According to the 2001 census, approximately 26% of Vancouver's population is Asian, suggesting that our study simply reflects the demographics of the region 4. If there was something specific to the Asian population that predisposes them to this disease, we would expect a greater percentage of our total patients to be of Asian descent than the general population. The reason for both Asian and Vancouver preponderance thus remains unclear, and other similarities such as diet or lifestyle may be factors. The literature does support a female preponderance to biliary cystic disease, commonly reported as 4:1 1,2,3. This gender pattern is echoed in this study but at a slightly higher ratio. Again, the reason for this preponderance remains unclear.

Todani et al. described a classification system of these cysts into six discrete types (Figure 1), which is still in use today 5,6. Although Todani initially felt that the different types represented a spectrum of the same disease, subsequent authors have challenged this notion. Some believe that each type represents a unique disease with separate aetiologies, natural course and ideal treatment 7,8. The most common are types I and IVA, and this preponderance was also seen in our study. Interestingly, the paediatric population only presented with types I and IVA, whereas the adults presented with almost full representation. The aetiology of types I and IVA cysts is thought to be due to an abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction, which results in a long common channel and mixing of pancreatic and biliary juice, leading to mucosal breakdown and dilatation 9. This can present early (in children) with high grade reflux or later (adulthood) with low grade reflux 10,11,12,13,14. Other authors contend that the cysts are congenital in nature, either due to distal aganglionosis and proximal dilatation or aberrancies in embryologic recannulation 15,16. Unfortunately, the length of the common channel or the presence of an abnormal junction was not recorded in many of these cases. Such data, as well as pathological examination for aganglionosis or distal obstruction, can be examined in future studies to further elucidate the aetiological differences between children and adults. Ironically, types II and V are believed to be completely congenital in nature, but these were found exclusively in the adult population of this study 17,18,19,20,21. This could just reflect the fact that types II and V are in general rare, representing 2% and 20% of cysts in literature, respectively, and they are often insidious 20,22.

Both the paediatric and adult populations presented most commonly with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and jaundice, in that order. This represents the fact that bile and pancreatic juice reflux and bile stasis lead to chronic inflammation, and stone and stricture formation. This in turn leads to recurrent cholangitis, hepatic abscesses and pancreatitis, causing significant pain and jaundice 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. The classic triad of abdominal pain, jaundice and palpable mass was found in only 10.5% of the children and none of the adults. Reported literature found the classic triad in <20% of patients, and was mostly found in neonatal patients (<1 year of age) 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. In our study, none of the patients with the classic triad were neonatal.

Ultrasound was the imaging modality of choice for children, whereas ERCP was most commonly used in adults. In fact ERCP was only used in 10.5% of children compared with 80% of adults. This may represent the need for general anaesthesia to perform ERCP in children, whereas none is required in adults 40. CT scans were also under-utilized in children when compared with adults.

Most children underwent complete cyst excision, cholecystectomy and hepaticojejunostomy. This is now the surgery of choice, but did not become so until around 1980. The paucity of major complications in this series of children likely reflects the fact that this strategy was adopted early in the practice of our surgeons. Four adult patients with type IVa cysts did not receive complete cyst excision due to extension of disease and marked fibrosis and adhesions. Any such retained cyst tissue is associated with ongoing risk of malignant transformation 45,46. Furthermore, there were some adult patients with long-term complications of anastamotic stricture, malignancy and recurrent cholangitis. Adult disease likely reflects chronic insidious disease, and the longer bile stasis and resultant inflammation is allowed to continue, the greater the risk of fibrosis and adhesions, thus hindering complete excision. Surgery on tissue that is chronically inflamed also increases the risk of subsequent complications such as anastamotic strictures 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. Therefore the earlier in life after diagnosis the surgery is performed, the more beneficial it is to prevent fibrosis and avoid such ongoing inflammation and damage. In fact, four of our pediatric patients were operated on even before any symptomatology. We do recommend this strategy, as the onset of symptoms indicates inflammation in and damage to the biliary tree, which pre-emptive surgery will negate. Finally, it is well recognized that just cystenterostomy leads to recurrent complications of cholangitis, pancreatitis, stricture and stone formation and malignancy 45,46; therefore, none of the patients in our series received this surgery. The adults who had previously received cystenterostomy did suffer from such complications.

In all, 48.5% of our patients (6 paediatric and 28 adults) had type IVA cysts, with some element of intrahepatic involvement. While the surgeries performed – cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy – removed extrahepatic pathological tissue, intrahepatic disease remained. Such intrahepatic dilatations are prone to bile stasis, stone and sludge formation, recurrent cholangitis and subsequent hepatic abscess formation, and cholangiocarcinoma 17,21,50. This risk is somewhat alleviated by a wide hilar anastamosis, but nonetheless remains as long as the intrahepat ic cysts remain. Localized intrahepatic disease may be treated with a segmental lobectomy to eliminate the intrahepatic component 50,51,52. Unfortunately, all of our patients did have diffuse involvement. Therefore the livers were left in situ, and the premalignant, intrahepatic choledochal cysts did transform into cholangiocarcinoma in four (14%) of adult patients with type IVa cysts, subsequently requiring segmental hepatic lobectomy. Therefore we do recommend that intrahepatic cysts be excised as much as possible.

Conclusion

This study retrospectively analysed the largest series of patients with choledochal cysts outside of Asia, and compared adult and paediatric patients. Both groups had similar presentations of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and jaundice. Ultrasound was the imaging modality of choice in children, whereas ERCP was more commonly used in adults. This likely reflects the technical difficulties of performing ERCP in children rather than any differences in sensitivity for diagnosis. All paediatric patients underwent complete cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, and suffered from very few long-term complications. We do recommend this as the surgery of choice, and we also recommend that it should be performed early after diagnosis irrespective of symptom severity to avoid future complications.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

There are no disclosures.

References

- 1.Vater A. Dissertation in auguralis medica. poes diss. qua. Scirrhis viscerum dissert. c. s. ezlerus. Edinburgh: University Library, 1723:70:19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard ER. Howard ER. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford: 1991. Choledochal cysts, Surgery of liver disease in children; pp. 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gigot J, Nagorney D, Farnell M, Moir C, Ilstrup D. Bile duct cysts: a changing spectrum of disease. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1996;3:405–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ethnic Origin. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 2001Census of Canada. January 21, 2003. July 27, 2007.www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/Products/Standard/Index.cfm [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alonso-Lej F, Rever WB, Pessango DJ. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of 2, and analysis of 94 cases. Int Abstracts Surg. 1959;108:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cyst: classification, operative procedure, and review of 37 cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visser BC, Suh I, Wy LW, Kang SM. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 2004;139:855–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.8.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiseman K, Buczkowski AK, Chung SW, Francoeur J, Schaeffer , Scudamore CH. Epidemiology, presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of choledochal cysts in adults in an urban environment. Am J Surg. 2005;189:527–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babbitt DP. Congenital choledochal cyst: new etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of the common bile duct and pancreatic bulb. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1969;12:231–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong IH, Jung YS, Kim H, Kim BW, Kim JW, Hong J, et al. Amylase level in extrahepatic bile duct in adult patients with choledochal cyst plus anomalous pancreatico-biliary ductal union. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1965–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i13.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan JH, Hu XL, Dai GJ, Niu J, Gu JQ. Expression of p53 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in congenital choledochal cysts. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3:120–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwai N, Yanagihara J, Tokiwa K, Shimotake T, Nakamura K. Congenital choledochal dilatation with emphasis on pathophysiology of the biliary tract. Ann Surg. 1992;215:27–30. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xioa X, Li H, Wang O, Tong S. Abnormal pancreatic isoamylases in the serum of children with choledochal cysts. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:26–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todani T, Narusue M, Watanabe Y, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Management of congenital choledochal cyst with intrahepatic involvement. Ann Surg. 1978;187:272–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197803000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yotsuyanagi S. Contribution to aetiology and pathology of idiopathic cystic dilatation of the common bile duct with report of three cases. Gann: Japanese Journal of Cancer Research. 1936;30:601–752. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davenport M, Basu R. Under pressure: choledochal malformation manometry. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:331–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Sanyal AJ. Case 38: Caroli disease and renal tubular ectasia. Radiology. 2001;220:720–2. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2203000825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mousson C, Rabec M, Cercueil JP, Virot JS, Hillon P, Rifle G. Caroli's disease and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a rare association? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1481–3. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.7.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ninan VT, Nampoory MRN, Johny KV, Gupta RK, Schmidt I, Nair PM, et al. Caroli's disease of the liver in a renal transplant patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1113–15. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.6.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sgro M, Rosetti S, Barozzino , Toi A, Langer J, Harris PC, et al. Caroli's disease: prenatal diagnosis, postnatal outcome and genetic analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:73–6. doi: 10.1002/uog.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguilera V, Rayón M, Pérez-Aguilar F, Berenguer J. Caroli's syndrome and imaging: report of a case. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96:74–6. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082004000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy AD, Rohrman CA. Biliary cystic disease. Curr Prob Diagn Radiol 2003;233–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aguilera V, Rayón M, Pérez-Aguilar F, Berenguer J. Caroli's syndrome and imaging: report of a case. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96:74–6. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082004000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landing BH. Considerations of the pathogenesis of neonatal hepatitis, biliary atresia and choledochal cyst: the concept of infantile obstructive cholangiopathy. Prog Pediatr Surg. 1974;5:113–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira LH, Bustorff-Silva JM, Sbraggia-Neto L, Bittencourt DG, Hessel G. Choledochal cyst: a 10-year experience. J Pediatr. 2000;76:143–8. doi: 10.2223/jped.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi LB, Peng SB, Meng XK, Peng CH, Liu YB, Chen XP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of congenital choledochal cyst: 20 years’ experience in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:732–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, Boitnott JK, Cameron JL. Choledochal cyst disease: a changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg. 1994;220:644–52. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stain SC, Guthrie CR, Yellin AE, Donovan AJ. Choledochal cyst in the adult. Ann Surg. 1995;222:128–33. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee HL, Yeung CY, Fang SB, Jiang CB, Sheu JC, Wang NL. Biliary cysts in children – long-term follow-up in Taiwan. J Formosan Med Assoc. 2006;105:118–24. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rattan KN, Magu S, Ratan S, Chaudhary A, Seth A. Choledochal cyst in children: 15 year experience. Ind J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neill JA, Templeton JM, Jr, Schnauffer L, Bishop HC, Ziegler MM, Ross AJ 3rd. Recent experience with choledochal cyst. Ann Surg. 1987;205:153–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198705000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sela-Herman S, Scharschmidt BF. Choledochal cyst, a disease for all ages. Lancet. 1996;347:779. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Büyükyavuz Y, Ekinci S, Ciftçi AO, Karnak I, Senocak ME, Tanyel FC. A retrospective study of choledochal cyst: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Turk J Pediatr. 2003;45:321–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soreide K, Korner H, Havnen J, Soreide JA. Bile duct cysts in adults. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1538–48. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rha SY, Stovroff MC, Glick PL. Choledochal cyst: a ten year experience. Am Surg. 1996;62:30–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hewitt PM, Krige JEJ, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Choledochal cysts in adults. Br J Surg. 1995;82:382–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Vries JS, de Vries S, Aronson DC, Bosman DK, Rauws EA, Bosma A, et al. Choledochal cysts: age of presentation, symptoms, and late complications related to Todani's classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1568–73. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.36186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Postema RR, Hazebroek FWJ. Choledochal cysts in children: a review of 28 years of treatment in a Dutch children's hospital. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:1159–61. doi: 10.1080/110241599750007694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabra V, Agarwal M, Adukia TK, Dixit VK, Agrawal AK, Shukla VK. Choledochal cyst: a changing pattern of presentation. Aust N Z J Surg. 2001;71:159–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma AK, Wakhlu A, Sharma SS. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of choledochal cysts in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;130:65–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90612-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koshinaga T, Hoshino M, Inoue M, Gotoh H, Sugito K, Ikeda T, et al. Pancreatitis complicated with dilated choledochal remnant after congenital choledochal cyst excision. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:936–8. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bismuth H, Krissat J. Choledochal cystic malignancies. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl 4):S94–S98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fieber SS, Nance FC. Choledochal cyst and neoplasm: a comprehensive review of 106 cases and presentation of two original cases. Am Surg. 1997;63:982–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gardikis S, Antypas S, Kambouri K, Lainakis N, Panagidis A, Defteros S, et al. The roux-en-Y procedure in congenital hepato-biliary disorders. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuchiya R, Harada N, Ito T, Furukawa M, Yoshihiro I. Malignant tumors in choledochal cysts. Ann Surg. 1977;186:22–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197707000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe Y, Toki A, Todani T. Bile duct cancer developed after cyst excision for choledochal cyst. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:207–12. doi: 10.1007/s005340050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee SC, Kim HY, Jung SE, Park KW, Kim WK. Is excision of a choledochal cyst in the neonatal period necessary? J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1984–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamataka A, Ohshiro K, Okada Y, Hosoda Y, Fujiwara T, Kohno S, et al. Complications after cyst excision with hepaticoenterostomy for choledochal cysts and their surgical management in children versus adults. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyano T, Yamataka A, Kato Y, Segawa O, Lane G, Takamizawa S, et al. Hepaticoenterostomy after excision of choledochal cyst in children: a 30-year experience with 180 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1417–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90843-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levy A, Rohrman CA, Murukata LA, Lonergan GJ. Caroli's disease: radiologic spectrum with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1053–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.4.1791053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tao KS, Lu YG, Wang T, Dou KF. Procedure for congenital choledochal cysts and curative effect analysis in adults. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:442–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hussain SZ, Bloom DA, Tolia V. Caroli's disease diagnosed in a child by MRCP. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:289–91. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(00)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]