Abstract

Conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs) are routinely used for hormone replacement therapy (HRT), making it important to understand the activities of individual estrogenic components. Although 17β-estradiol (17β-E2), the most potent estrogen in CEE, has been extensively characterized, the actions of nine additional less potent estrogens are not well understood. Structural differences between CEEs and 17β-E2 result in altered interactions with the two estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and different biological activities. To better understand these interactions, we have determined the crystal structure of the CEE analog, 17β-methyl-17α-dihydroequilenin (NCI 122), in complex with the ERα ligand-binding domain and a peptide from the glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) coactivator. NCI 122 has chemical properties, including an unsaturated B-ring and 17α-hydroxyl group, which are shared with some of the estrogens found in CEEs. Structural analysis of the NCI 122-ERα LBD-GRIP1 complex, combined with biochemical and cell-based comparisons of CEE components, suggests that factors such as decreased ligand flexibility, decreased ligand hydrophobicity and loss of a hydrogen bond between the 17-hydroxyl group and His524, contribute significantly to the reduced potency of CEEs on ERα.

Keywords: hormone replacement therapy, estrogens, estrogen receptor structure, conjugated equine estrogens, Premarin

Introduction

Conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) drugs found in Premarin (CEE alone; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA) and Prempro (CEE + medroxyprogesterone acetate; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals) are commonly used for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in post-menopausal women [1]. Currently, these drugs are prescribed to reduce menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness as well as for the prevention of osteoporosis [2]. However, the use of HRT, especially Prempro, for preventing heart disease is controversial and currently not recommended [2]. Recent results [3,4] of the Women’s Health Initiative trials [5] has argued against the use of HRT for preventing heart disease, although other data have supported a positive role for HRT [6–9], citing beneficial effects on reducing the risk of coronary heart disease. Clearly, more information is needed about the mechanisms by which CEEs and progestins may promote the increased risks of stroke, blood clots and breast cancer, presumably via their cognate receptor proteins in affected tissues.

As CEE consists of complex mixtures of at least ten estrogens [10], each estrogenic component may not only differentially activate the two estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes but can also act differently in a tissue-dependent manner. Thus, understanding the ER mediated actions of the individual components of these drugs is imperative to interpreting results obtained from the use of these multifaceted drug formulations. To the best of our knowledge, the only estrogenic component of these formulations whose structure has been reported in complex with ER is 17β-estradiol (17β-E2) [11]. Relatively little is known about how the other 9 estrogenic components interact with ER at the structural level. These other estrogens differ from 17β-E2, especially in regard to their B-ring saturation and the stereochemistry and identity of the chemical moieties at the 17-position (Figure 1).

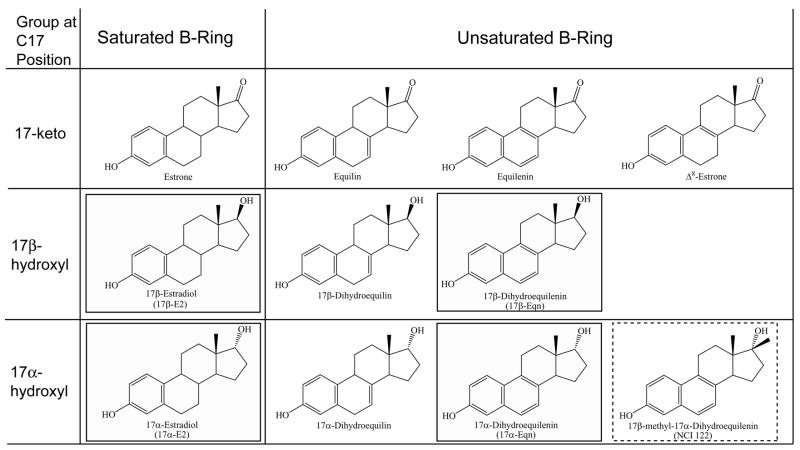

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of estrogens. Structures of the estrogens used in this study (solid black boxes) as well as the structures of other estrogens present in conjugated equine estrogen drug formulations. Also shown is the chemical structure of NCI 122 (17β-methyl-17α-dihydroequilenin) (dotted black box).

We have identified NCI 122 (17β-methyl-17α-dihydroequilenin), from a screen of approximately 10,000 compounds [12] that shares many similarities with some of the estrogens in CEE. For example, the unsaturated B-ring and 17α-hydroxyl (17α-OH) group of NCI 122 are also present in half the estrogens found in CEE (Figure 1). These structural similarities suggest that the elucidation of NCI 122’s interactions with ER would shed light on the mechanisms of action of these other estrogens. To this end, we have determined the crystal structure of NCI 122 in complex with the ERα ligand binding domain (ERα LBD) and a glucocorticoid receptor interaction protein 1 (GRIP1) peptide. Structural data are complemented by biochemical and cell-based studies to understand the actions of NCI 122 with ER (PDB ID: 2B1Z). Our findings with NCI 122 were used to interpret the activities of four estrogenic components of CEE: 17α-dihydroequilenin (17α-Eqn), the closest analog of NCI 122; 17β-dihydroequilenin (17β-Eqn), the epimer of 17α-Eqn; 17β-estradiol (17β-E2), the primary endogenous estrogen; and 17α-estradiol (17α-E2), the epimer of 17β-E2 (Figure 1). By understanding which properties of these estrogens are responsible for their transcriptional activity on ER, it may be possible to identify weak estrogens that have some of the beneficial effects attributed to estrogens while avoiding ER-mediated side effects.

Experimental

Reagents

17β-Eqn (17β-dihydroequilenin), 17α-Eqn (17α-dihydroequilenin), 17α-E2 (17α-estradiol) and 17β-E2 (17β-estradiol) were obtained from Steraloids Inc. [3H]17β-E2 was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). NCI 122 (17β-methyl-17α-dihydroequilenin) was obtained from the Development Therapeutics Program of the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health.

Plasmids

Many of the plasmids used in these studies were generous gifts from colleagues: p3×ERE-Luc from Dr. Donald McDonnell (Duke University, Durham, NC), pAR and p3×ARE-Luc from Dr. Shutsung Liao (The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL). pCMV-βgal was obtained from Invitrogen. Other plasmids used for protein expression have been described previously [12].

Homogenous Time Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF) Assays

Plasmids used in this assay, and methods for the expression of FLAG-SRC1 and GST-ERα LBD were previously described [12]. For the HTRF assay, FLAG-SRC1 and GST-ERα LBD were dialyzed in HTRF buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin) and separately pre-incubated with anti-FLAG-XL665 and anti-GST-Eu(K) (Cisbio Internation (Gif/Yvette Cedex, France)), respectively, for 1 h at 4°C. The two mixtures were then combined before adding test ligands (0.5%, v/v) and 2 M KF solution. This mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 1–2 h with agitation. The plates were read on a Wallac 1420 MicroPlate Reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The fluorescence resonance energy transfer signal was determined from the ratio of the emission intensities at 665 and 615 nm scaled by a factor of 104. EC50 values in this and other assays were determined from the data using SigmaPlot (Systat Software).

Competitive Ligand Binding Assays

Plasmids used in this assay and methods for expressing His-tagged ERα LBD and ERβ LBD have been previously described [12]. His-tagged ERα LBD/ERβ LBD was diluted with binding buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% beta-octyl glucoside, and 0.1% (v/v) glycerol) to 2–8 nM and added to the wells of nickel-coated FlashPlates (PerkinElmer). The proteins were incubated for ~ 2 h at 25 °C to allow the ER to bind. Plates were then washed 5 times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), before the addition of 2.5 nM [3H]17β-E2 and test ligand diluted in binding buffer. The ligands were incubated overnight at 4 °C and the plates were analyzed with a MicroBeta Scintillation Counter (PerkinElmer). All samples were performed in triplicate. IC50 values were determined from the data using SigmaPlot (Systat Software).

Transient Transfection and Transactivation Assays

Stably transfected U2OS-ERα and U2OS-ERβ cells (generous gifts from Drs. Thomas Spelsberg and David Monroe (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN)) were grown and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped FBS, blasticidin S and zeocin as described previously [13]. In the transient transfection of U2OS-ERα and U2OS-ERβ cells, 250 ng of p3×ERE-Luc, 25 ng of pCMV-βgal and 125 ng of carrier DNA were delivered to the cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 5.5 h, before replacing the transfection media with media containing doxycyline (100 ng/mL) to induce ER expression. In the COS-7 AR assays, 150 ng p3×ARE-Luc, 30 ng pAR, and 30 ng pCMV-βgal were delivered to the cells using PolyFect (Qiagen) reagent. In both assays, ligands that had been diluted 1:200 in phenol red-free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS) were added to the cells 18–24 h before cell harvest and lysis. Luciferase activities from lysed cells were analyzed on a MicroBeta (PerkinElmer) luminescence counter and values were normalized with those from β-galactosidase activity (Promega).

Expression, Purification and Crystallization of ERα LBD

Steps for the expression and purification of ERα LBD, as well as the initial screening for crystallization conditions were performed as previously described [12]. For NCI 122, optimization of initial screen conditions yielded diffraction-quality crystals of ER in ~ 1 week at 16 °C in 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, 25 % (w/v) PEG 3350, pH 8.5. Crystals were soaked in the mother liquor and 10 % (v/v) glycerol prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Data Collection, Structure Determination and Refinement

A single-wavelength (0.979 Å) native dataset was collected on a Quantum 135 detector at the 14-BM beamline of the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, IL). Data were collected with an oscillation of 1.0° and an exposure of 5 s per image, to a resolution of 1.78 Å with an average redundancy of 3.7. Data were integrated and merged using HKL2000 [14] and then used in molecular replacement using MOLREP [15] with the ER structure from PDB entry 1ZKY serving as the search model. For model-building and refinement the XtalView [16], CNS (v1.1) [17] and REFMAC [18] programs were used. Missing residues and alternate conformations for some side chains along with waters were manually modeled. The missing residues in the final model are at the termini and surface loops. Details of diffraction data collection and processing of the ERα crystal complex are available in Table 2. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession code 2B1Z. Figures showing electron density maps were prepared with BOBSCRIPT [19] and rendered in Raster3D [20]. All other diagrams were prepared with Swiss-PdbViewer [21] and rendered in POV-RAY (Persistence of Vision Ray Tracer; www.povray.org). Structural alignments were performed with Swiss-PdbViewer.

Table 2.

Summary of the crystallographic data. Diffraction data collection parameters, processing, and refinement statistics for the NCI 122-ERα LBD-GRIP1 crystal complex

| Ligand | 17-methyl-17α-dihydroequilenin |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Spacegroup | P21 |

| Unit cell | |

| a,b,c (Å) | 55.92 83.80 58.52 |

| β (deg) | 108.94 |

| Protein molecules/asymmetric units | 2 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 Å |

|

| |

| Data processing | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30.0–1.78 (1.84–1.78)a |

| Reflections | 48202 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.6 (99.1)a |

| Rmerge (%)b | 5.1 (40.2)a |

|

| |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20.0–1.78 |

| Reflections | 45694 |

| Rwork (%) | 20.4 (25.6)a |

| Rfree (%) | 23.8 (32.9)a |

| rmsd of: | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (deg) | 0.951 |

| Mean B factor | 28.84 |

|

| |

| Protein Data Bank code | 2B1Z |

Highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = Σ|I(k) − [I]|/ΣI(k), where I(k) is the value of the kth measurement of the intensity of a reflection, [I] is the mean value of the intensity of that reflection, and Σ is of all of the measurements. Rfactor = Σ|Fobs − Fcalc|/Σ|Fobs|.

Clog P Values

Clog P values were determined using Chemdraw Ultra 9.0 (CambridgeSoft) using algorithms developed by Daylight Chemical Information Systems (Claremont, CA). The Clog P is a calculated log P value where P is the partition coefficient of a compound defined by the ratio of its concentration in 1-octanol to its concentration in water when the solvents are in equilibrium. The log P of a small molecule can be used as a measure of its hydrophobicity.

Results

FRET Coactivator Recruitment Assay and Competitive Binding Assay

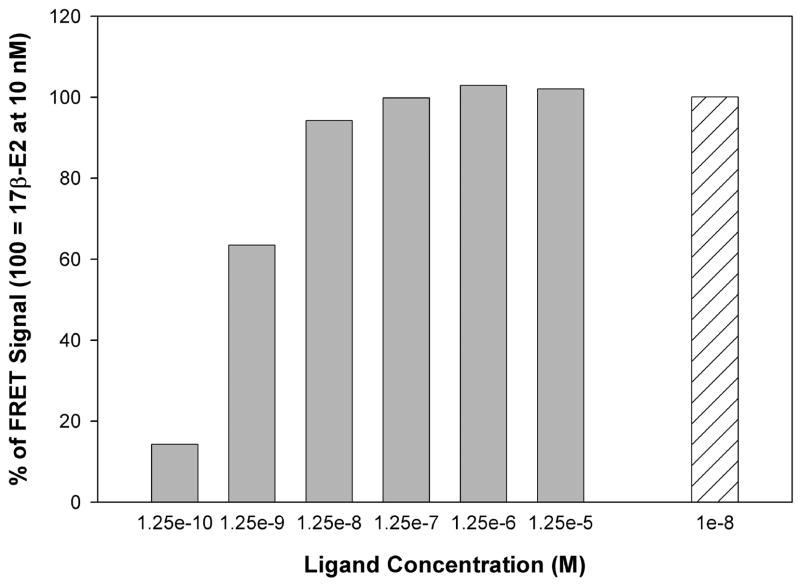

The ability of NCI 122 to promote an agonist conformation of ERα LBD that can recruit a coactivator was assessed using homogenous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF), a fluorescence energy transfer (FRET)-based assay [12]. As shown by the results of the HTRF assay in Figure 2, NCI 122 promotes a dose dependent recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator 1 nuclear receptor interacting domain (SRC1 NRD) to ERα LBD. Based on the curve, it is clear that NCI 122 has an efficacy similar to that of 17β-E2 because the maximum FRET signal achieved at saturating concentrations is the same as that achieved by 17β-E2. Thus, NCI 122 acts as a full agonist in this assay.

Figure 2.

The dose dependent response of NCI 122 measured using the fluorescence energy transfer-based assay. Results from a representative experiment are shown here. The maximum response induced by 17β-E2 at saturating concentrations (10 nM) is shown for comparison.

In order to characterize the binding of NCI 122 and four other estrogens to the two ER subtypes, we performed competitive binding assays with [3H]17β-E2. The results are summarized in Table 1A. NCI 122 can be seen to compete with [3H]17β-E2 for binding to the ligand binding pocket of ER with an affinity comparable to the two dihydroequilenins in ERα and 17α-E2 in ERβ. These competitive binding experiments also showed that NCI 122, as well as the two dihydroequilenins, bind slightly preferentially to ERβ.

Table 1.

(A) ER binding and ERβ subtype selectivity of NCI 122 and four estrogens found in CEE drugs. (B) Transcriptional potency and selectivity of NCI 122 and four other estrogens found in CEE drugs on full-length (FL) ER in stably transfected U2OS cells. (C) Calculated log P values (where P is the partition coefficient between n-octanol and water) of compounds.

| A | B | C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBAa (IC50)b |

β-selectivityc | REPd (EC50)

|

β-selectivitye | Calculated Log P | |||

| ERα | ERβ | FL ERα | FL ERβ | ||||

| 17β-E2 | 100 (6.3 nM) | 100 (10 nM) | 1.0 | 100 (7.5 pM) | 100 (4.2 pM) | 1.0 | 3.784 |

| 17α-E2 | 18 (35 nM) | 18 (57 nM) | 1.0 | 1.5 (4.9 nM) | 0.57 (7.4 nM) | 0.4 | 3.784 |

| NCI122 | 8.1 (79 nM) | 16 (64 nM) | 2.0 | 1.4 (5.3 nM) | 0.81 (5.2 nM) | 0.6 | 4.045 |

| 17β-Eqn | 9.0 (70 nM) | 55 (19 nM) | 6.2 | 1.6 (4.7 nM) | 11 (0.38 nM) | 6.9 | 3.526 |

| 17α-Eqn | 9.7 (66 nM) | 52 (20 nM) | 5.4 | 0.23 (32 nM) | 1.5 (2.9 nM) | 6.2 | 3.526 |

Relative Binding Affinity (RBA) is determined from the formula IC50 (17β-E2)/IC50 (Ligand) scaled by 100

IC50 values were determined in competitive binding assays between test ligands and [3H]17β-E2 on ERα or ERβ.

β-selectivity is determined from the ratio RBA (ERβ)/RBA (ERα).

Relative estrogenic potency (REP) = (EC50(17β-E2)/EC50(ligand)) × 100. EC50 values were from the data shown in Figure 2A and Figure 2B.

β-selectivity is determined from the ratio REP (ERβ)/REP (ERα).

Transcriptional Characterization and Specificity Assay

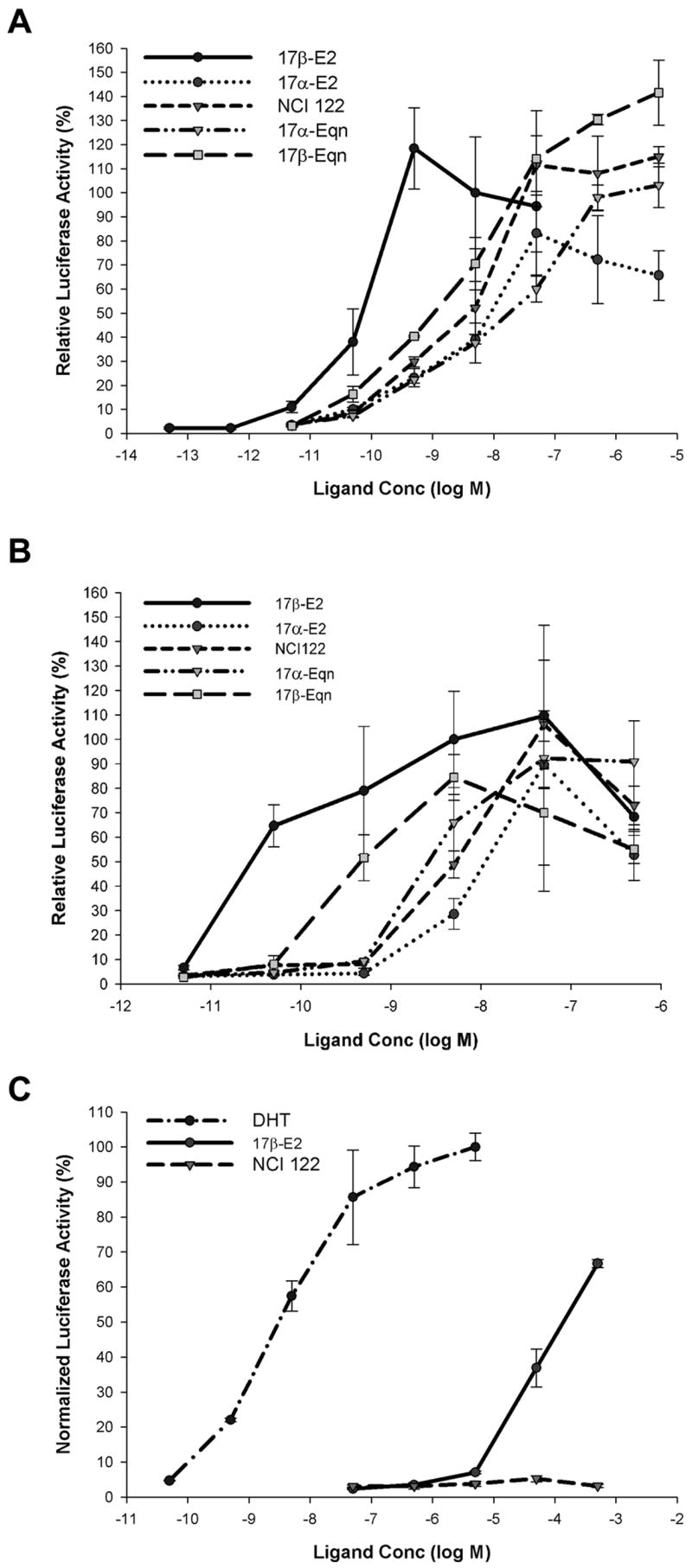

Stably transfected U2OS-ERα and U2OS-ERβ cells [13] were used to assess the transcriptional activity of NCI 122 and the four CEE compounds on the two subtypes of ER. These cells were transiently transfected with a 3×ERE-luciferase reporter and treated with ligands at various doses. The potencies of each of these compounds were measured by determining their EC50 values from the curves in Figures 3A and 3B. As summarized in Table 1B, NCI 122 had potencies comparable to 17α-E2 and 17β-Eqn on ERα and potencies comparable to 17α-E2 and 17α-Eqn on ERβ. Both 17α-Eqn and 17β-Eqn showed a slight preference for ERβ activation, consistent with their ligand-binding preferences. Interestingly, there was also the general trend of the 17β-hydroxyl (17β-OH) epimers of both the estradiols and the dihydroequilenins being more potent than the 17α-hydroxyl (17α-OH) epimers.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional activity of ERα, ERβ and AR. U2OS (human osteosarcoma) cells stably transfected with ER (U2OS-ERα and U2OS-ERβ) were transiently transfected with vectors for 3×ERE-Luc reporter and control β-galactosidase expression plasmid. A) ERα and B) ERβ transcriptional activity with NCI 122, 17α-E2, 17β-E2, 17α-Eqn and 17β-Eqn. Luciferase activities were normalized against β-galactosidase activity to correct for transfection efficiency. Each sample was performed in triplicate and relative luciferase activity values shown are the mean ± SEM expressed as a percentage of the ERα or ERβ response with 5 nM 17β-E2. For AR studies, COS-7 (monkey kidney) cells were transiently transfected with vectors for AR, 3×ARE-Luc reporter and control β-galactosidase expression plasmid. AR transcriptional activity was tested with NCI 122, 17β-E2 and DHT (Figure 3C). Luciferase activities were normalized against β-galactosidase activity to correct for transfection efficiency. Each sample was performed in triplicate and relative luciferase activity values shown are the mean ± SEM expressed as a percentage of the AR response with 5 μM DHT.

To assess the specificity of NCI 122 in activating ER, NCI 122 was also tested on the androgen receptor (AR). For this assay, the activity of NCI 122 was compared to the activities of the natural androgen, dihydrotestosterone, and 17β-E2. As shown in Figure 3C, NCI 122 does not noticeably activate transcription through AR. This is in contrast to 17β-E2, which activates transcription through AR at concentrations above 5 μM.

Crystal Structure of NCI 122

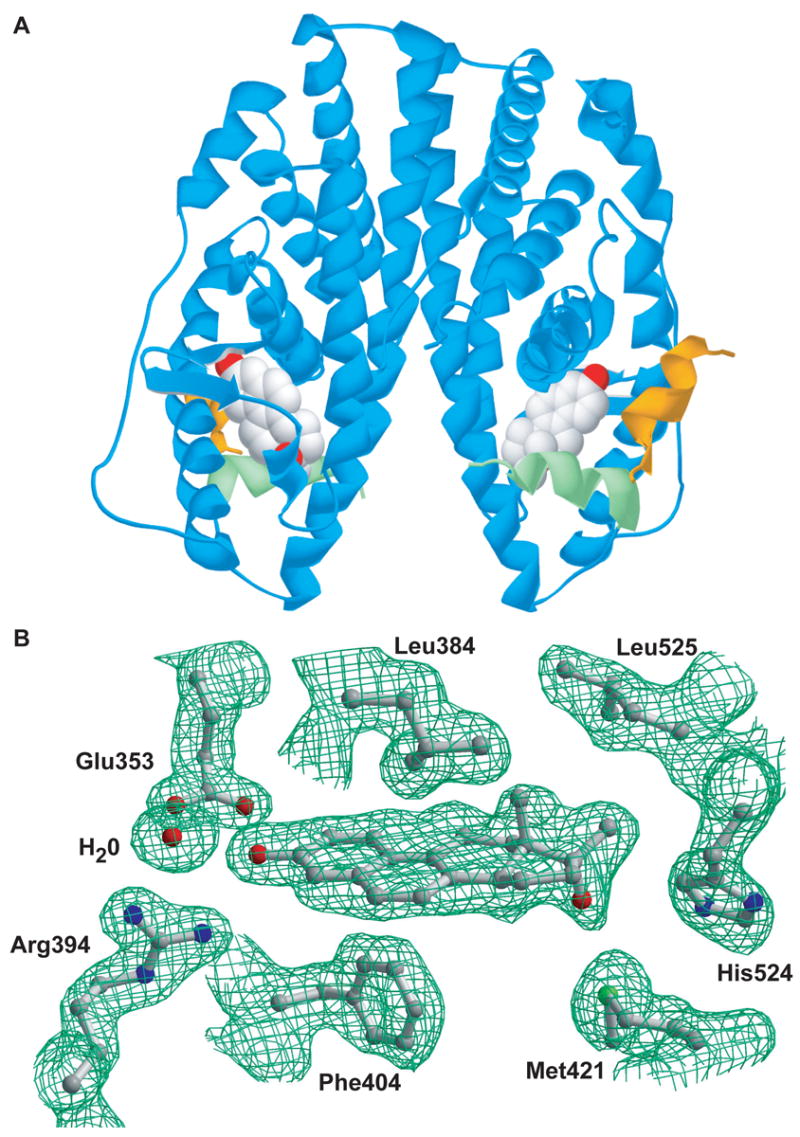

To understand the molecular mechanisms of NCI 122 action, we determined the crystal structure of the NCI 122-ERα LBD-GRIP1 complex to a resolution of 1.78 Å. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an ER structure in complex with an unsaturated B-ring steroid. A summary of the crystallographic data is shown in Table 2. Overall, the ERα LBD adopts a conformation similar to those of other ER agonists including 17β-E2 [22], diethylstilbestrol (DES) [23] and our previously reported oxabicyclic compounds [12]. Thus, helix 12 (H12) packs against H3, H5, H6 and H11 such that a hydrophobic groove is formed to accommodate the binding of the LXXLL motif of the GRIP1 coactivator peptide (Figure 4A). The quality of the model and fit of the ligand in the electron density can be seen from the Fo-Fc electron density omit maps (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

ERα LBD dimer in complex with NCI 122 and GRIP1 peptide, plus details of its ligand binding site. A) The ribbon diagram of the ERα LBD dimer (blue) is shown in complex with a peptide fragment of the GRIP1 coactivator protein (yellow) and with NCI 122 (space-filled model). The position of Helix 12 (green) of the LBD and the co-crystallization with GRIP1 peptide reflect the agonist conformation. B) Shown are ball-and-stick renderings of NCI 122 along with its interacting residues and corresponding Fo-Fc electron density omit maps contoured at 1.95 sigma in the ligand-binding site of ERα.

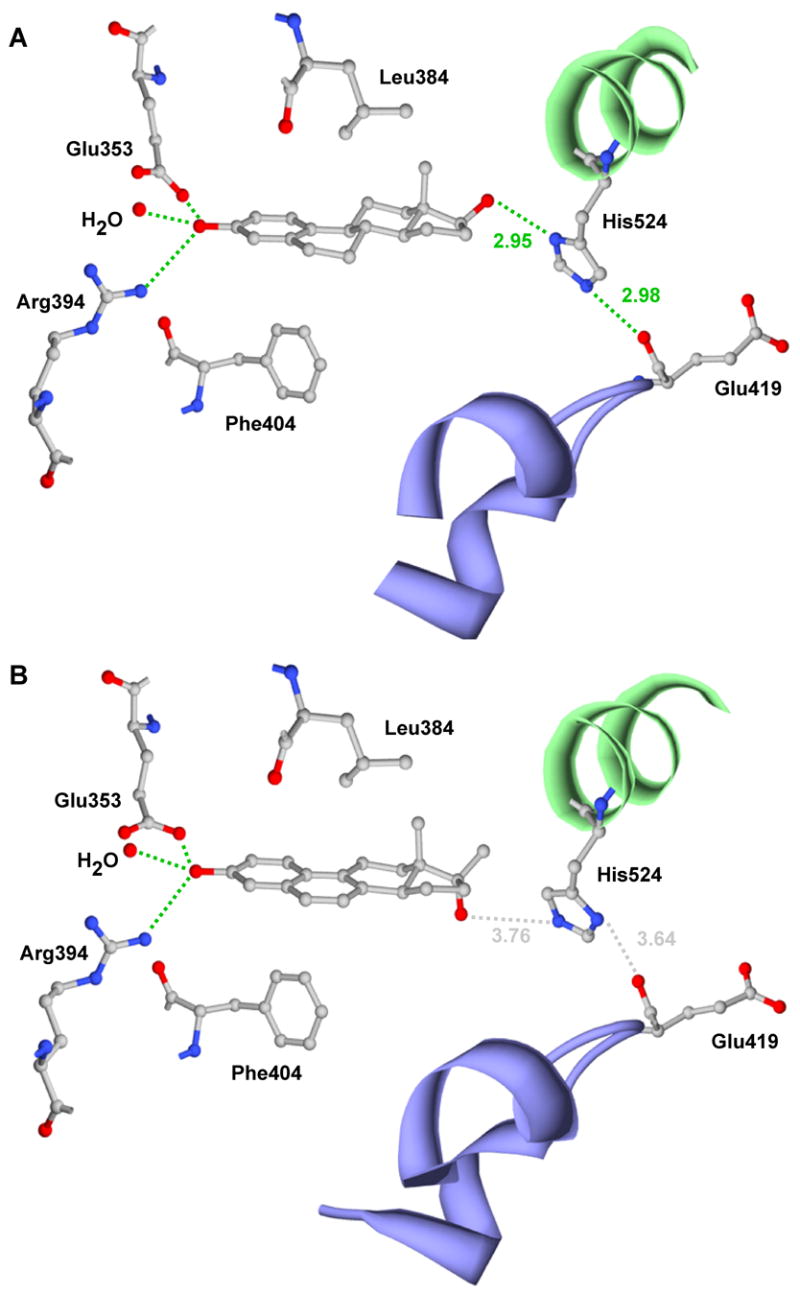

The A-ring of NCI 122, like that of 17β-E2 (Figure 5A), is involved in a hydrogen bond network with Glu353, Arg394 and an ordered water molecule (Figure 5B). However, unlike 17β-E2, which forms a hydrogen bond between His524 and the 17β-OH (Figure 5A), no hydrogen bonding occurs between NCI 122 and the ER ligand-binding pocket in the D-ring region (Figure 5B). The remaining interactions of NCI 122 with the receptor are hydrophobic (Figure 6B). These contacts occur primarily through the steroidal scaffold of NCI 122, although interactions with three residues, Met343, His524 and Leu525, occur via the 17β-methyl group.

Figure 5.

Hydrogen bond interactions in the ligand binding pocket of ERα. Shown are the hydrogen bonds of A) 17β-E2 (PDB ID: 1GWR) or B) NCI 122 (PDB ID: 2B1Z) with the residues that line the ligand binding pocket of ER. Also shown are the positions and interactions of His524 and Glu419. Hydrogen bond lengths (Å) are shown in green, while distances between non-interacting residues are shown in grey dotted lines. A portion of H11 is shown as a green ribbon and portions of H6 and H7 surrounding Glu419 are shown as blue ribbons.

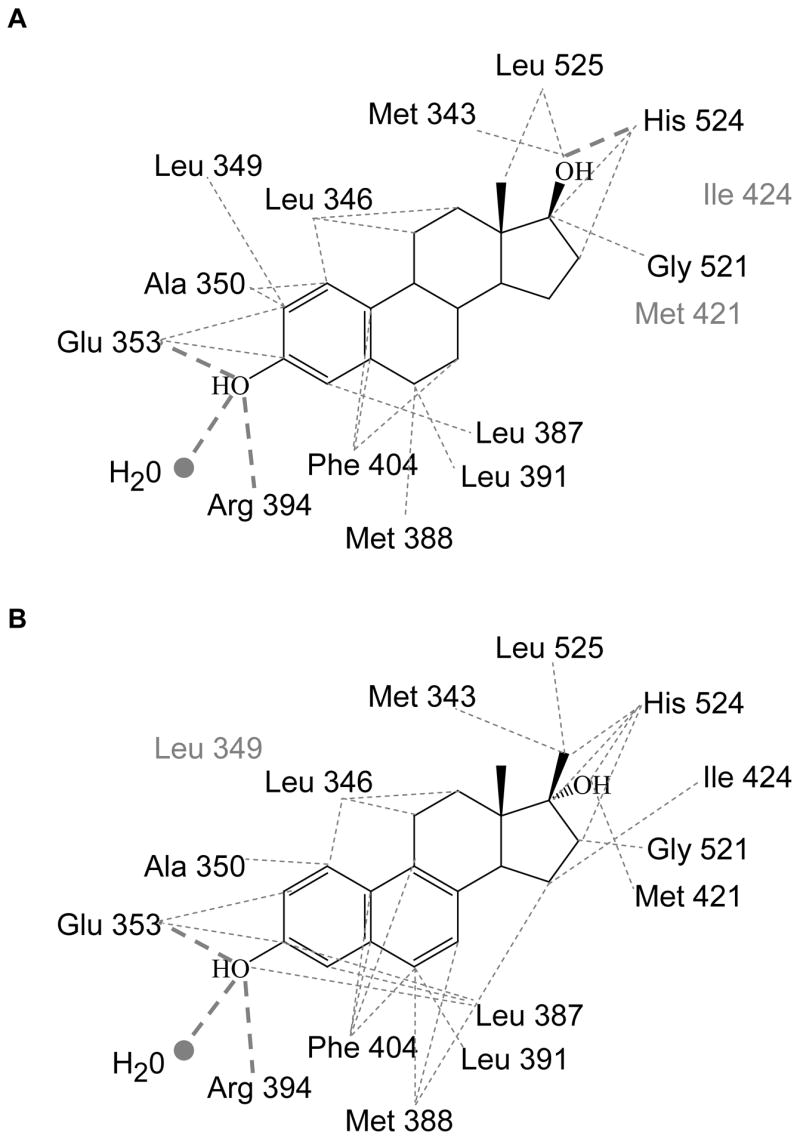

Figure 6.

Ligand interactions with ERα LBD. The residues interacting with A) 17β-E2 and B) NCI 122 are shown. Thin grey dotted lines depict van der Waal interactions and thick grey dotted lines show hydrogen bonds. Residues in grey do not interact with the ligand shown but interact with the other ligand in the figure.

Discussion

Based on FRET-based chemical screens, we have identified a novel steroidal ER agonist, NCI 122 that is also a chemical analog of components found in CEE used for HRT. It is similar to 17α-Eqn and 17β-Eqn because it possesses an unsaturated B-ring and similar to both 17α-E2 and 17α-Eqn because it has a 17α-OH group.

We used several approaches to elucidate the biological characteristics of NCI 122. Thus, NCI 122 competes with [3H]17β-E2 for binding to ER, but with a binding affinity weakest among the estrogens tested (Table 1A). The HTRF assay shows that like 17β-E2, NCI 122 acts as a full agonist in recruiting coactivator (Figure 2). In cell-based studies, our results were consistent with those obtained from the biochemical experiments. Thus, transactivation assays performed in U2OS cells with full-length receptors showed that while NCI 122 was much less potent than 17β-E2 (Table 1B) it acted as a full agonist on ERα and ERβ (Figures 3A and 3B). Finally, the inability of NCI 122 to stimulate transcription of a reporter gene through AR (Figure 3C) shows that NCI 122 is specific for ER.

Observations from the crystal structure of the NCI 122-ERα LBD-GRIP1 complex confirmed our findings from the biochemical and cell-based studies. The structure clearly shows that NCI 122 is bound in the ligand-binding pocket of the ERα LBD and that the LBD assumes an agonist conformation that allows the binding and co-crystallization of the GRIP1 coactivator peptides (Figure 4A). However, it is not immediately obvious from the corresponding ERα LBD structures why NCI 122 is a less potent agonist than 17β-E2. The two structures can be aligned via their main chain atoms with a root mean square deviation of only 0.51 Å over 904 atoms. Thus, we sought to determine whether the relative potencies of the different estrogens could be explained by ligand-estrogen interactions at the molecular level.

A comparative analysis of the NCI 122-ERα LBD-GRIP1 structure and that of 17β-E2-ERα LBD (PDB ID: 1GWR) [22] shows the most obvious difference to be the interactions of the ligands with His524. The 17β-OH group of 17β-E2 is positioned 2.95 Å from the nearest nitrogen (δ1-N) of His524 (Figure 5A), allowing efficient hydrogen bonding, whereas the 17α-OH of NCI 122 is 3.76 Å from the nearest His524 nitrogen (ε2-N) and therefore cannot form a hydrogen bond with His524 (Figure 5B). The absence of this hydrogen bond in the D-ring region for NCI 122 undoubtedly contributes to its weaker potency. As both 17α-E2 and 17α-Eqn possess 17α-OH groups, our analyses of NCI 122 would predict that they too cannot hydrogen bond with His524. This would likely result in the potencies of these α epimer compounds being lower than their corresponding β epimers. This prediction is consistent with transactivation data, which show that the 17β epimers of both the estradiols and dihydroequilenins are more potent than the 17α epimers (Table 1B).

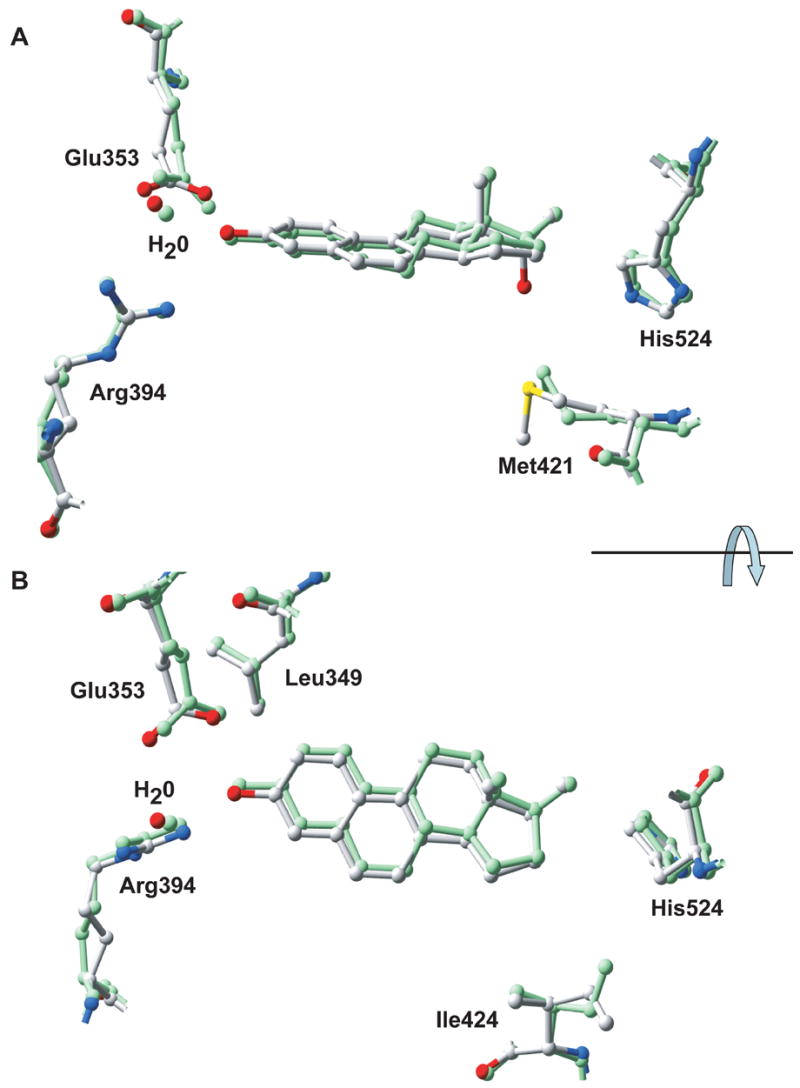

However, the differences in the activities of NCI 122 and 17β-E2 are not completely accounted for by differences in their hydrogen bonding with His 524. This is illustrated by the finding that estrogens with similar stereochemistry at the 17-position (and presumably hydrogen bond interactions with His524) also differ in their activities. In particular, the B-ring saturated estradiols are transcriptionally more potent than the B-ring unsaturated dihydroequilenins (Table 1B). For ERα, 17β-E2 is 60 times more potent than 17β-Eqn, while 17α-E2 is 7 times more potent than 17α-Eqn. These data suggest that unsaturation at the B-ring decreases the activity of steroids. The differences are not obviously explained by comparing the ligand binding interactions of 17β-E2 and NCI 122 with ERα in their respective crystal structures. Structurally, the positioning of the steroid scaffolds of 17β-E2 and NCI 122 are nearly identical (Figures 7A and 7B). This position is dictated by the requisite interactions made via the phenolic A-rings to establish a hydrogen bonding network with Glu353, Arg 394 and a conserved water molecule (Figures 5A and 5B). The hydrophobic interactions made by the steroid scaffolds of both ligands with the residues lining the ligand-binding pocket of ERα are also almost identical (Figures 6A and 6B). The minor observed differences are unique contacts made by NCI 122 with Met421 and Ile424, which are not observed in the 17β-E2-bound ERα structure. Contact with Met421 is made by the 17α hydroxyl of NCI 122 (Figure 7A), while contact with Ile424 occurs because the position of NCI 122 is slightly offset towards Ile424 and away from Leu349 when compared to the position of 17β-E2 (Figure 7B). These minor differences in interactions, however, do not fully account for the large disproportion in activity observed between the estradiols and the dihydroequilenins.

Figure 7.

Two orthogonal views comparing the binding of NCI 122 and 17β-E2 to ERα LBD. The NCI 122-ERα LBD-GRIP1 complex (multi-colored)) (PDB ID: 2B1Z) was superimposed with the 17β-E2-ERα LBD complex (green) (PDB ID: 1GWR) by alignment of their backbone atoms. Residues in the ligand binding site are shown as ball-and-stick diagrams. Glu353, Arg394, His524 and a water molecule are shown in both figures. For viewing simplicity, A) shows Met421 while B) shows Ile424 and Leu349.

As B-ring saturation is the major difference between the estradiols and dihydroequilenins, one can predict that these B-ring properties also relate to the differences in the observed ligand activities. The importance of the B-ring is evident from published studies of 17β-E2 with ERα, which show that it is second only to the A-ring in its contribution to receptor binding [24]. The primary effect of changes to B-ring saturation is on the overall flexibility and hydrophobicity of the ligands. For 17β-E2, which has a saturated B-ring, the B-ring is responsible for most of the conformational flexibility present in the steroidal scaffold [24]. Crystal structures show that 17β-E2 binds ERα with its flexible B-ring in a half-chair conformation and C-ring in a chair conformation (Figures 5A and 7A). In contrast, the crystal structure of NCI 122 with ERα shows that it binds receptor with a planar B-ring, kept rigid by the π-electron system shared between its B and A-rings (Figures 5B and 7A). The C-ring of NCI 122 is also affected by the planarity of the B-ring, as it resides in the half-chair conformation (Figures 5B and 7A). The effect of these differences is that the more flexible steroid scaffold of 17β-E2 has additional freedom to sample receptor conformations than can be achieved by the more rigid steroid scaffold of NCI 122. Thus, 17β-E2 is able to adopt a better ligand-receptor fit than NCI 122, which translates into an increased potency of 17β-E2 on ERα compared to the rigid dihydroequilenins, as confirmed by our cell-based transcriptional studies. This correlation of decreased planarity with increased ERα activity has also been observed for other ER ligand classes [25].

The B-ring also influences the overall hydrophobicity of the molecule. Based on calculated log P values, the estradiols are more hydrophobic than the dihydroequilenins (Table 1C). Since the ligand-binding pocket is predominantly hydrophobic [26], the more hydrophobic estradiol molecules can interact more effectively with the receptor than the dihydroequilenins. This difference may also contribute significantly to ERα activity because hydrophobic interactions between 17β-E2 and receptor are believed to account for over half of its free energy of binding [24]. Thus, a combination of decreased hydrophobicity and a planar, less flexible steroid scaffold likely explains the less potent activity of the dihydroequilenins relative to the estradiols on ERα, when comparing ligands that are stereochemically equivalent at the 17-position.

Interestingly, an additional unexpected mechanism may also contribute both to the weak ERα activity of NCI 122 and to differences in activity between 17β-E2 and NCI 122. In the NCI 122-ERα LBD-GRIP1 structure, the imidazole ring of His524 is flipped approximately 180° (Figure 5B) relative to that found in other agonist-ER complexes [22,23,26], such as those containing 17β-E2 (Figure 5A). When agonists such as 17β-E2 are bound, His524 on H11 is stabilized by two hydrogen bonds, one between the His524 imidazole δ1-nitrogen and the 17β-OH of 17β-E2, and the other between the His524 imidazole ε2-nitrogen and the main chain oxygen of Glu419 (Figure 5A). However, for NCI 122, both of these stabilizing hydrogen bonds are lost due to the rotation of the His524 imidazole (Figure 5B). The driving force behind this rotation appears to be the hydrophobic interaction established between the δ2-carbon of the imidazole and the 17β-methyl of NCI 122. This interaction partially compensates for the inability of NCI 122 to form the prototypical ligand-His524 hydrogen bond (Figure 5A), but has a secondary effect of disrupting a potential His524-Glu419 hydrogen bond. Thus, H11 is somewhat de-stabilized when NCI 122 is bound because the single hydrophobic interaction between H11 and NCI 122 does not replace the two hydrogen bonds that are formed with other agonists. Due to the importance of H11 in controlling the agonist conformation of nuclear receptors and their subsequent coactivator recruitment [27–30], de-stabilization of H11 on binding NCI 122 may contribute to the weaker potency of NCI 122 in stimulating ERα transcriptional activity. Thus, the combined effects of the 17α-OH group, the unsaturated B-ring and the de-stabilization of H11 result in reduced potency for NCI 122 as an estrogen.

Although NCI 122 and other weakly ER-active steroids (such as 17α-Eqn) have less potent affinity for ER than 17β-E2, differences in their transcriptional activity as well as examples of their therapeutic potential can perhaps be attributed to non-ER interactions. The dihydroequilenin epimers, for example, have been shown to be among the most potent estrogens in CEE for the prevention of low density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation [31,32]. They were also shown to be more effective than the estradiol epimers in protecting cultured neuronal cells from glutamate toxicity [33,34]. These effects may be due to properties of the dihydroequilenins that affect their ability to modify and cross lipid bilayers, interact with other cellular proteins or become oxidized/metabolized. The dihydroequilenins and possibly other estrogens found in CEE drugs may have implications for the prevention of atherosclerosis and neurodegenerative disease and warrant further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NCI Grant CA089489, Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-04-1-0791 and the Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research. R.W.H. was supported by the University of Chicago unendowed Medical Scientist Training Program. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. Use of the BioCARS Sector 14 was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, under grant number RR07707. The authors would like to acknowledge support of the UCCRC Protein Peptide Synthesis Core in the processing of peptides (CCSG grant 5 P30 CA014599-32). We thank Drs. Andzrej Joachimiak and Frank Collart (Argonne National Laboratory) for the use of materials and facilities at Argonne National Laboratory, Drs. Ning Lei and Vukica Srajer (Argonne National Laboratory) for assistance at BioCARS, Drs. Milan Mrksich, Stephen Kent and Wei-Jen Tang (The University of Chicago) for helpful comments. We also thank all of our colleagues who provided plasmids and cells used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. Jama. 2004;291(1):47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefanick ML. Estrogens and progestins: background and history, trends in use, and guidelines and regimens approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Med. 2005;118(12 Suppl 2):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, Margolis K, Ockene J, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Ritenbaugh C, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto G, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace R, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;291(14):1701–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288(3):321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petitti DB, Perlman JA, Sidney S. Noncontraceptive estrogens and mortality: long-term follow-up of women in the Walnut Creek Study. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70(3 Pt 1):289–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of postmenopausal estrogen therapy and coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(17):1044–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510243131703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush TL, Barrett-Connor E, Cowan LD, Criqui MH, Wallace RB, Suchindran CM, Tyroler HA, Rifkind BM. Cardiovascular mortality and noncontraceptive use of estrogen in women: results from the Lipid Research Clinics Program Follow-up Study. Circulation. 1987;75(6):1102–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.6.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson BE, Paganini-Hill A, Ross RK. Estrogen replacement therapy and protection from acute myocardial infarction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159(2):312–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(88)80074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhavnani BR. Estrogens and menopause: pharmacology of conjugated equine estrogens and their potential role in the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;85(2–5):473–82. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Strom A, Treuter E, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):905–31. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh RW, Rajan SS, Sharma SK, Guo Y, DeSombre ER, Mrksich M, Greene GL. Identification of ligands with bicyclic scaffolds provides insights into mechanisms of estrogen receptor subtype selectivity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(26):17909–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monroe DG, Getz BJ, Johnsen SA, Riggs BL, Khosla S, Spelsberg TC. Estrogen receptor isoform-specific regulation of endogenous gene expression in human osteoblastic cell lines expressing either ERalpha or ERbeta. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90(2):315–26. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–26. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit--A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol. 1999;125(2–3):156–65. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunger AT. Free R-Value - a Novel Statistical Quantity for Assessing the Accuracy of Crystal-Structures. Nature. 1992;355(6359):472–75. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(Pt 3):240–55. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esnouf RM. An extensively modified version of MolScript that includes greatly enhanced coloring capabilities. J Mol Graph Model. 1997;15(2):132–34. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(97)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merritt EA, Bacon DJ. Raster3D: Photorealistic molecular graphics. Method Enzymol. 1997;277:505–24. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18(15):2714–23. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warnmark A, Treuter E, Gustafsson JA, Hubbard RE, Brzozowski AM, Pike AC. Interaction of transcriptional intermediary factor 2 nuclear receptor box peptides with the coactivator binding site of estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(24):21862–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95(7):927–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anstead GM, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen JA. The estradiol pharmacophore: ligand structure-estrogen receptor binding affinity relationships and a model for the receptor binding site. Steroids. 1997;62(3):268–303. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(96)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anstead GM, Kym PR. Benz[a]anthracene diols: predicted carcinogenicity and structure-estrogen receptor binding affinity relationships. Steroids. 1995;60(5):383–94. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(94)00070-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389(6652):753–8. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Radek JT, Meyers MJ, Nettles KW, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA, Agard DA, Greene GL. Structural characterization of a subtype-selective ligand reveals a novel mode of estrogen receptor antagonism. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9(5):359–64. doi: 10.1038/nsb787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray DW, Suen CS, Brass A, Soden J, White A. Structure/function of the human glucocorticoid receptor: tyrosine 735 is important for transactivation. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(11):1855–63. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.11.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens A, Garside H, Berry A, Waters C, White A, Ray D. Dissociation of steroid receptor coactivator 1 and nuclear receptor corepressor recruitment to the human glucocorticoid receptor by modification of the ligand-receptor interface: the role of tyrosine 735. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(5):845–59. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nettles KW, Sun J, Radek JT, Sheng S, Rodriguez AL, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Greene GL. Allosteric control of ligand selectivity between estrogen receptors alpha and beta: implications for other nuclear receptors. Mol Cell. 2004;13(3):317–27. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhavnani BR, Cecutti A, Gerulath A, Woolever AC, Berco M. Comparison of the antioxidant effects of equine estrogens, red wine components, vitamin E, and probucol on low-density lipoprotein oxidation in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2001;8(6):408–19. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subbiah MT, Kessel B, Agrawal M, Rajan R, Abplanalp W, Rymaszewski Z. Antioxidant potential of specific estrogens on lipid peroxidation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77(4):1095–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.4.8408459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhavnani BR, Berco M, Binkley J. Equine estrogens differentially prevent neuronal cell death induced by glutamate. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003;10(5):302–8. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Lu X, Bhavnani BR. Equine estrogens differentially inhibit DNA fragmentation induced by glutamate in neuronal cells by modulation of regulatory proteins involved in programmed cell death. BMC Neurosci. 2003;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]