Abstract

The effects of pH on the uptake and accumulation of Hg(II) by Escherichia coli were determined at trace, environmentally relevant, concentrations of Hg and under anaerobic conditions. Hg(II) accumulation was measured using inducible light production from E. coli HMS174 harboring a mer-lux bioreporter plasmid (pRB28). The effect of pH on the toxicity of higher concentrations of Hg(II) was measured using a constitutive lux plasmid (pRB27) in the same bacterial host. In this study, intracellular accumulation and toxicity of Hg(II) under anaerobic conditions were both significantly enhanced with decreasing pH over the pH range of 8 to 5. The pH effect on Hg(II) accumulation was most pronounced at pHs of <6, which substantially enhanced the Hg(II)-dependent light response. This enhanced response did not appear to be due to pH stress, as similar results were obtained whether cells were grown at the same pH as the assay or at a different pH. The enhanced accumulation of Hg(II) was also not related to differences in the chemical speciation of Hg(II) in the external medium resulting from the changes in pH. Experiments with Cd(II), also detectable by the mer-lux bioreporter system, showed that Cd(II) accumulation responded differently to pH changes than the net accumulation of Hg(II). Potential implications of these findings for our understanding of bacterial accumulation of Hg(II) under anaerobic conditions and for bacteria-mediated cycling of Hg(II) in aquatic ecosystems are discussed. Arguments are provided suggesting that this differential accumulation is due to changes in uptake of mercury.

The fate of mercury [Hg(II)] in aquatic ecosystems is highly dependent on a number of microbe-mediated transformations. Hg(II) methylation, demethylation, reduction, and elemental mercury (Hg0) oxidation are the four primary bacterium-mediated transformations that make up this cycle (3). Some of these reactions are specific for Hg(II), while others appear to mistake Hg(II) as an essential substrate in metabolic pathways. What is common among these transformations is that they are enzymatically catalyzed inside bacterial cells. Therefore, the rates of bacterial Hg(II) transformation will depend on (i) the amount of enzyme in the cell and (ii) the concentration of Hg(II) inside the cell.

The only clearly identified mechanism of Hg(II) uptake into bacterial cells is that mediated by proteins encoded by the mer operon (reviewed in references 3 and 10), which encodes enzymes that catalyze the reduction of Hg(II) to Hg(0) and thus prevents accumulation of Hg(II) taken up into the cell. Most bacteria do not contain the mer operon, and uptake of Hg(II) at trace external Hg concentrations still occurs (e.g., 14, 15), but the specific mechanism(s) by which Hg(II) is taken up has not been identified.

Recent work suggests that there could be more than one facilitated mechanism of Hg(II) uptake in bacteria (15), in addition to the possibility that Hg(II) is taken up by passive diffusion (5, 19). Knowledge of the mechanism(s) of Hg(II) uptake and accumulation in bacteria is important for the understanding of all of the transformations listed above. An understanding of the cellular parameters controlling bacterial Hg(II) methylation is especially important because methylmercury is more toxic than Hg(II) and is also more effectively bioaccumulated up the food chain (reviewed in reference 31).

One of the first steps in attempting to identify the mechanisms by which Hg(II) is taken into bacteria and accumulated is to find factors that enhance or decrease Hg(II) accumulation. Evidence that pH could be an important factor in affecting Hg(II) uptake in bacteria was first found when anaerobic Hg(II) accumulation was enhanced in the presence of carboxylic acids that lowered the assay medium pH below 6 (15). A subsequent study into the effect of pH on Hg(II) accumulation in Vibrio anguillarum demonstrated that even small changes in pH (7.3 to 6.3) resulted in large increases in Hg(II) accumulation under aerobic conditions (25). Since methylation of Hg(II) occurs predominantly under anaerobic conditions (12) and bacterial Hg(II) methylation rates increase following acidification of natural environments (8, 30, 41), further studies into the effect of pH on Hg(II) accumulation under anaerobic conditions were warranted.

In the work presented here, the effect of pH on the internal Hg(II) concentration at trace external concentrations was investigated for the first time under anaerobic conditions. In order to study trace concentrations of Hg(II) that are bioavailable within a bacterial cell, radiolabeled 203Hg could not be used, because the specific activity currently available does not provide sufficient sensitivity and it is difficult to distinguish trace concentrations of Hg(II) inside the cell from Hg(II) bound to the outside of the cell. Therefore, intracellular Hg(II) accumulation was investigated using a plasmid borne mer-lux bioreporter (pRB28) (33) as an indicator of the Hg(II) concentration inside the cell and a plasmid-borne constitutive lux system (pRB27) (1) as an indicator of Hg(II) toxicity and general cell fitness. Results from these assays demonstrated that, under anaerobic conditions and within a pH range where the cells were capable of growth (pH 5 to 8), the accumulation and toxicity of Hg(II) were significantly enhanced as the pH of the assay medium decreased. Potential implications of these findings for our understanding of how Hg(II) is transported into bacterial cells under anaerobic conditions are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains used in this study included Escherichia coli HMS174 ATCC 47011 and Vibrio anguillarum ATCC 14181. The E. coli strains RKP2922 (formerly SJB201) and MG1655 were kindly provided by R. K. Poole and were described by Beard et al. (4). Net accumulation of Hg(II) was quantified by light production from the mer-lux bioreporter plasmid (pRB28) (33). A constitutive lux plasmid (pRB27) was used as a control to test for changes in light emission unrelated to Hg(II) accumulation, which might be caused by physiological responses of host bacteria to the chemistry of the different environments from which the cells are being assayed (2). The constitutive plasmid was also used in toxicity assays as a means of measuring general cell fitness in response to an elevated Hg(II) concentration.

Reagents and HgTotal analysis.

Culture flasks, Teflon centrifuge tubes, and reagent bottles were washed in 30% H2S04 and rinsed thoroughly with low-Hg(II) [<0.3 ng liter−1 Hg(II)] Milli-Q water. Reagents were periodically analyzed for total Hg(II) by Flett Research Ltd. (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) using a cold atomic fluorescence spectrometer (model 2; Brooks Rand, Ltd.) and EPA Method 1631, as adapted by Bloom and Creselius (9).

Growth of cultures for toxicity and bioreporter assays.

For maintenance of the plasmids, kanamycin (Kan) was added to a final concentration of 60 μg ml−1 in the growth medium. Five ml of aerobic Luria-Bertani broth was inoculated with a single isolated colony from a Luria-Bertani-Kan agar plate and incubated at 28°C with shaking until late log phase. The culture was brought into an anaerobic Coy glove bag and maintained under a 93% N2-7% H2 atmosphere, and 100 μl was transferred to a serum vial containing 5.9 ml of anaerobic glucose minimal medium, as described by Golding et al. (15), and sealed with a rubber butyl stopper. The culture was reincubated at 28°C with shaking at 150 rpm until late/mid-log phase. The culture was brought back into the anaerobic glove bag, and 20 ml of fresh anaerobic glucose minimal medium-Kan broth was added. The cultures were reincubated at 28°C with shaking at 150 rpm until mid-log phase.

Cell preparation for toxicity and bioreporter assays.

The final 25-ml mid-log culture was decanted into 50-ml nominal capacity O-ring Teflon centrifuge tubes in the glove bag. The tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 20 ml of anaerobic 67 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7). The centrifugation and resuspension in anaerobic phosphate buffer were then repeated. The final cell pellet was resuspended in 3 to 5 ml of anaerobic phosphate buffer. The optical density (OD) of the final cell suspension was diluted to an OD600 of 0.4 using anaerobic phosphate buffer via a syringe. The cultures were further diluted 100-fold in anaerobic phosphate buffer to a final cell concentration of ∼ 2 × 106 cells/ml.

Toxicity and bioreporter assays.

The assays were performed in simple chemically defined medium made using analytical-grade components consisting of 5 mM glucose, 9 mM (NH4)2SO4, and a total inorganic phosphate concentration of 67 mM, unless otherwise noted, consisting of NaH2PO4 and K2HPO4, with the ratio of these two reagents determining the pH. All exposures of cells to Hg(II) in these assays were done under anaerobic conditions. The Hungate method (23) was used to eliminate O2 for the reagents used in the anaerobic assays, and no reducing agents were added to substantially lower the Eh. A ChemMets O2 kit was used to ensure the media were O2 free (O2 < 1 ppb). In the glove bag the anaerobic components of the defined assay medium were mixed directly into the scintillation vials, to a final volume of 19 ml.

The primary mercury standard was a 1-μg ml−1 Hg(II) solution, containing 1% BrCl, provided by Flett Research Ltd. A 0.5-ml aliquot of the primary standard was transferred to a Teflon vial and brought into the glove bag. The primary Hg(II) standard was diluted twice in anaerobic Milli-Q water in Teflon vials left overnight in the Coy anaerobic glove bag. Assays were initiated by adding 1 ml of the diluted cell suspension at timed intervals coinciding with the time it takes for the scintillation counter to measure each vial. The vials were incubated at room temperature in the glove bag until the desired time of measurement. At that time the samples were removed from the glove bag. For light measurement the vial was quickly opened and shaken three times to aerate the sample and then immediately placed in the scintillation counter for counting (Beckman LS 6500; set in noncoincidence mode for 30-s count intervals). The effect of aerating the anaerobic sample for this short period would not be expected to have an effect on the bioreporter response, since it takes about 20 min for the bacteria to express the proteins required for bioluminescence to detectable levels. The photons of light detected by the scintillation counter over a 30-second interval are represented in the figures as counts per minute. Relative luminescence was calculated by dividing the counts per minute measured in the Hg(II)-amended samples by the counts per minute measured in non-Hg(II)-amended blank samples at each pH tested.

Growth measurements in defined assay media.

For the growth measurements in defined assay media, the cells were initially grown and prepared as described above for the toxicity and bioreporter assays. Balch-Wolfe tubes containing 10 ml of the assay medium were inoculated with the bacterium for an initial cell concentration of ∼1 × 105 cells/ml. To mimic the bioreporter assays, the tubes were maintained at room temperature without shaking and the growth was monitored over time by measuring the OD600 in a Biochrom Novaspec II spectrophotometer.

Hg(II) speciation calculations.

The speciation of Hg(II) was calculated using MINEQL+ version 4.5 and stability constants of Martell and Smith (28). Calculations were based on the measured pH of the assay medium and the calculated concentrations of the various ligands added to the sample vials. Since no reducing agents were used under anaerobic conditions, the effect of Eh was not considered in the speciation calculations. To limit the carryover of bacterial exudates that might have been present in the initial growth medium, the cells were washed twice in phosphate buffer prior to the bioreporter and toxicity assays.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of pH on Hg(II)-dependent light production.

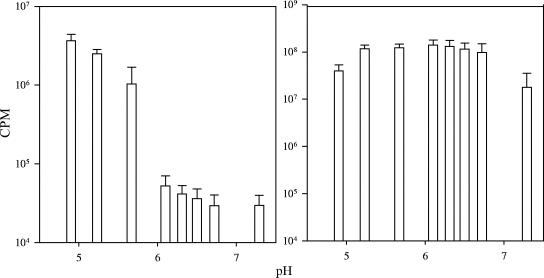

The effect of pH on Hg(II)-dependent light production following exposure to trace concentrations of Hg(II) under anaerobic conditions was investigated in E. coli HMS174 cells harboring a bioreporter plasmid (pRB28) (33). A pH range of 5 to 8 was chosen because it is within the growth range of E. coli (24) and is also representative of many natural anoxic environments. In samples supplemented with 1 ng liter−1 Hg(II), a significant light response above background from E. coli HMS174(pRB28) was only observed when the pH of the assay medium was <6 (Fig. 1, left, and Fig. 2, left). This response continued to increase as the pH of assay medium was further decreased below 6 (Fig. 1, left). Similar results were also obtained using V. anguillarum as the bioreporter host under anaerobic conditions (14).

FIG. 1.

Effect of varying pH on the Hg(II)-induced light response of 1 ng liter−1 in E. coli HMS174(pRB28) (left) and on constitutive light production from E. coli HMS174(pRB27) (right). Light production was measured following 120 min of incubation. Error bars represent the standard deviations of two independent experiments (n = 4).

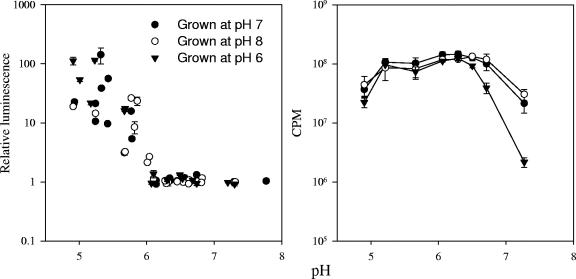

FIG. 2.

Effect of varying pH on the Hg(II)-induced light response from E. coli HMS174(pRB28) preconditioned in pH 6 to 8 growth medium (left) and on constitutive light production from E. coli HMS174(pRB27) (right). Hg(II) was added to a final concentration of 1 ng liter−1 in the bioreporter assays, and light production was measured following 120 min of incubation. Error bars for the mer-lux bioreporter assays represent the standard deviations of duplicate samples. Error bars for the constitutive lux assays represent the standard errors of three independent assays (n= 6).

These results could most simply be interpreted as a direct effect of pH on intracellular Hg(II) accumulation, and therefore on induction of the mer-lux operon. In order to be confident of this interpretation, a number of alternative reasons for the increased light production at lower pH were examined. These were (i) possible enhancement of luminescence levels at a lower pH, (ii) increased light production following the sudden shift of cells grown at neutral pH to assay medium at a lower pH, and (iii) possible effects of a lower pH on the functioning of the regulatory site responsible for induction of the mer-lux bioreporter genes.

Effect of pH on luminescence [independent of Hg(II)].

To ensure that the enhanced bioluminescence in our assays was Hg(II) dependent and not a result of increased light capability of the cell from a decreased pH of the assay medium, bioluminescence levels from E. coli HMS174 cells harboring the lux-constitutive control plasmid (pRB27), as well as growth rates, were measured to evaluate general cell fitness throughout the pH range tested. There was little change in constitutive light production between pH 6.8 and 5.2, but light emission did decrease when the pH of the assay medium was below 5.2 or above pH 7 (Fig. 1, right). The mean generation times of E. coli HMS174(pRB28) decreased as the pH decreased below 6.5 or increased above 6.5 (Table 1). Therefore, even though the cells were physiologically compromised in their light-producing capability at pHs of <5.5 and in their growth at pHs of <6, the activity of the Hg(II)-inducible system was still significantly increased.

TABLE 1.

Effects of varying the pH on mean generation time for E. coli HMS174 in defined assay medium

| pH of assay medium | Mean generation timea (h/generation) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 7.2 |

| 5.5 | 6.1 |

| 6 | 5.7 |

| 6.5 | 4.7 |

| 7 | 6.5 |

| 7.5 | 7 |

Averages of triplicate samples are shown.

Effect of sudden shift in pH at initiation of assays.

Another artifact that could have influenced the results was the sudden shift in pH as the cells were transferred from the growth medium (pH 6.8) to the assay media of different pHs. To examine this, the cells were preconditioned in growth media of pHs 6, 7, or 8 prior to the assay. Regardless of the initial growth pH, an assay medium with a pH of <6 was still required for an Hg(II)-induced light response to 1 ng liter−1, which continued to increase with further decreases in pH below 6 (Fig. 2, left). Light production from pRB27 indicated that the shift in pH had little effect on light capability of the cell, except at the lowest and highest pHs tested, where light production declined (Fig. 2, right). Therefore, the pH effect observed appeared not to be the result of a sudden pH shift.

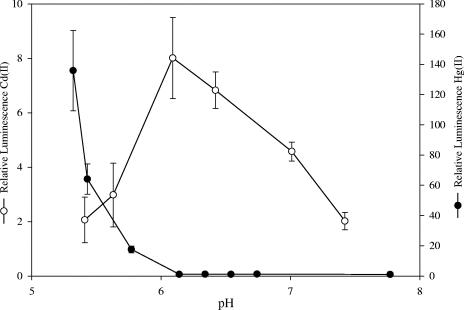

Investigation of possible effects of pH on induction of mer-lux using Cd(II).

Lowering the pH of the assay medium might have altered the sensitivity of the mer-lux bioreporter genes to induction by Hg(II). For example, induction of the mer operon is sensitive to the supercoiled state of the DNA (13), which can be altered by differences in osmolarity (22). To determine the effect of external pH on the induction of the mer-lux bioreporter, we compared the effect of pH on induction by Cd(II). Both metals have the ability to induce mer-lux, but we did not expect that the mechanisms governing their internal cell accumulation would be the same. Higher Cd(II) concentrations of 11.2 to 112 μg liter−1 (0.1 to 1 μM) were required to induce the mer-lux bioreporter in our assays, which was consistent with previous reported concentrations of Cd(II) required for induction of the mer operon (11, 32). Under anaerobic conditions, in pH 5.5 to 7.4 assay media, the mer-lux bioreporter response to Cd(II) followed a completely different pattern of induction compared to Hg(II) (Fig. 3). In the samples containing Cd(II), a bell-shaped curve was observed over the pH range tested, with an optimal Cd(II)-induced light response at pH 6.1. In contrast to Hg(II), the Cd(II)-induced light production decreased sharply as the pH was further lowered below pH 6.1. These experiments demonstrated that the pH effect observed with Hg(II) was not due to some general effect that caused MerR to respond more efficiently to its inducer metal. Rather, the external pH must have affected the mechanisms responsible for intracellular Cd(II) accumulation differently from the way that it affected Hg(II) accumulation.

FIG. 3.

Effect of pH on Cd(II)- and Hg(II)-induced light production in E. coli HMS174(pRB28). The assay medium contained a final concentration of 6.7 mM phosphate. Cd(II) and Hg(II) were added to final concentrations of 112 μg liter−1 and 1 ng liter−1, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviations of two independent assays (n = 4).

After eliminating the possible artifacts described above, we can conclude that the increased light production following anaerobic exposure to Hg at lower pHs (Fig. 1, left, 2, left, and 3) occurred because Hg(II) accumulated to higher internal concentrations and not because there were direct effects of pH on luminescence intensity or on the efficiency of mer-lux induction.

Effect of pH on net accumulation of Hg(II) under anaerobic conditions compared to aerobic conditions.

The pattern observed under anaerobic conditions was that lowering the pH from 8 to just above 6 had very little effect on Hg(II) accumulation, while lowering the pH further had a much larger effect. This was different than the effect of pH on Hg(II) uptake under aerobic conditions, where small decreases within the pH range 7.2 to 6.3 resulted in large increases in uptake in both V. anguillarum and E. coli (15, 25). It should be noted that at neutral pH, anaerobic bioreporter cells do not even show detectable Hg(II) accumulation at trace Hg concentrations. Thus, the pH enhancements under the two different conditions could be operating on two different pH-sensitive mechanisms. Alternatively, only one transport mechanism might be involved, but with regulatory or other factors affecting the mechanism differently under the two conditions.

The different characteristics of the effect of pH on Hg(II) accumulation under anaerobic and aerobic conditions in this study corroborate previous reports demonstrating that differences in bacterial physiology, as a result of the presence or absence of O2, play a significant role in the accumulation of Hg(II) inside the cell (15, 34). These differences are not surprising, considering the differential expression of a vast array of genes dependent on pH and O2 in E. coli (6, 21, 29, 35, 37, 42). For instance, under anaerobic conditions, 1,384 genes are differentially expressed in E. coli as a result of varying the pH of the medium from 5.7 to 8.5 (21). However, only 251 of these genes show similar responses under aerobic conditions (29). Thus, cells growing anaerobically show differences in genetic expression with respect to pH, which could explain the differential accumulation of Hg(II) observed in this study and others (15, 25, 34).

Effect of pH on Hg(II) toxicity under anaerobic conditions.

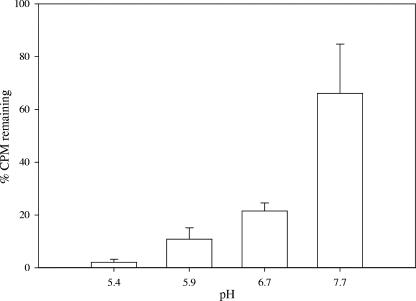

On the basis of the mer-lux bioreporter results, it could be hypothesized that conditions that enhance Hg(II) accumulation should also enhance the cytotoxic effect of Hg(II). Hg(II) toxicity can be measured as a reduction in bioluminescence from E. coli HMS174 harboring the constitutive lux plasmid pRB27 (16). At pH 7.7, the addition of 2,000 ng liter−1 of Hg(II) reduced bioluminescence levels to about 65% of that with no Hg added (Fig. 4). At lower pHs the reductions were much greater (Fig. 4). This increase in toxicity of Hg(II) is not surprising, considering the increased accumulation of Hg(II) observed at lower pHs when using the mer-lux bioreporter (Fig. 1, left).

FIG. 4.

Effect of pH on Hg(II) toxicity. Hg(II) was added to a final concentration of 2,000 ng liter−1. The amount of light measured in the Hg(II)-spiked medium was compared to the amount of light in the nonamended medium, at the same pH, and is expressed as a percentage of light remaining. Error bars represent the standard deviations of three independent assays (n = 5).

Possible role of PitA and formation of HgHPO4 in Hg(II) accumulation?

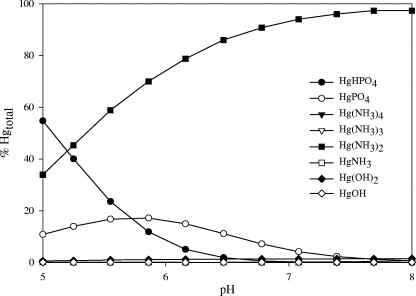

At pH 7, the predominate Hg(II) species calculated by MINEQL+ was Hg(NH3)22+, which accounted for 94 to 97% of the total Hg(II) in the bulk solution of the assay medium (Fig. 5). However, as the pH decreased below 6 there was a significant increase in the formation of a neutral Hg(II)-phosphate species, HgHPO4, which closely mimicked the anaerobic bioreporter response (Fig. 1, left, and 3). This led us to speculate that the neutral HgHPO4 species might be the form of Hg(II) taken up preferentially by E. coli under anaerobic conditions.

FIG. 5.

Effect of pH on Hg(II) speciation in the assay medium.

Interestingly, the formation of a neutral metal phosphate species, MeHPO4, is required for uptake by the phosphate inorganic transport system (PitA). PitA is a ubiquitous transport system that is constitutively expressed in E. coli and functions as an H+/solute symport system (reviewed in reference 39). PitA is a secondary low-affinity transporter for the divalent metal ions Mg(II), Ca(II), Mn(II), Co(II), Zn(II), and potentially Cd(II) (4, 40), but the uptake of Hg(II) was not tested in these previous reports.

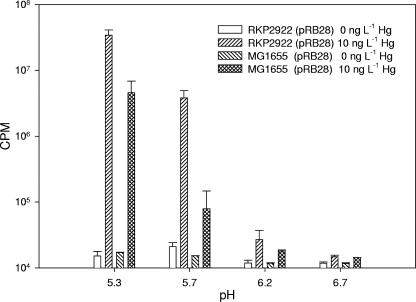

To determine if PitA was involved in the nonspecific transport of Hg(II), we obtained E. coli RKP2922 (formerly SJB201), which is a Tn10 pitA knockout mutant, and the corresponding parental strain, MG1655 (4). These two strains were transformed with the bioreporter plasmid pRB28 and assayed for their ability to accumulate Hg(II) under various assay conditions. Under anaerobic conditions, Hg(II)-induced light production increased with decreasing pH in both E. coli RKP2922(pRB28) and E. coli MG1655(pRB28) (Fig. 6). Since no differences in Hg(II) accumulation patterns were observed, it appears that PitA does not play a significant role in Hg(II) uptake.

FIG. 6.

Effects of varying the pH on Hg(II) uptake in E. coli MG1655(pRB28) and E. coli RKP2922(pRB28). Samples were incubated 120 min prior to measurement. Error bars represent the standard deviations of two independent assays (n = 4).

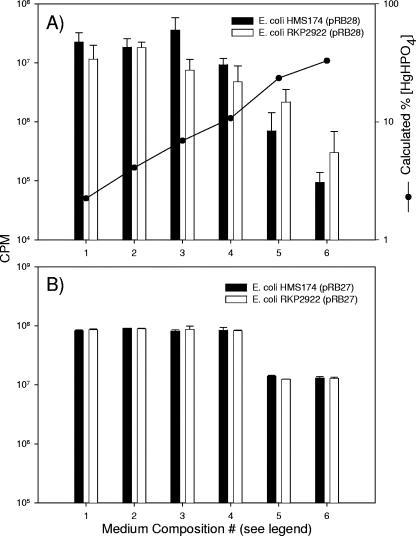

The possible role of neutral phosphate species diffusing passively into the cell was also examined by varying the concentrations of phosphate (8.75 to 67 mM) and (NH4)2SO4 (2.225 to 9 mM) in our assay media at a constant total added Hg(II), which enabled us to manipulate the speciation of HgHPO4 independently of pH. E. coli HMS174(pRB28) and E. coli RKP2922(pRB28) were used as indicators of Hg(II) accumulation under anaerobic conditions to distinguish whether increased concentrations of HgHPO4 could enhance Hg(II) accumulation in the absence of lowered pH. Hg(II) accumulation in E. coli HMS174(pRB28) and E. coli RKP2922(pRB28) did not correlate with the changes in the percentage of Hg(II) as HgHPO4 at a constant pH of 5.9 (Fig. 7A). The lessened response observed in the media containing lower concentrations of (NH4)2SO4 (media 5 and 6) appeared to be due to the energetics of the cell, as light production from the constitutive control (pRB27) was also decreased in this same medium for both strains (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Effects of varying the concentration of HgHPO4 independently of pH on Hg(II) uptake (pRB28) (A) and the effect of varying the concentration of phosphate and (NH4)2SO4 on constitutive light production (pRB27) (B) in E. coli HMS174 and E. coli RKP2922. Assays were performed in pH 5.9 assay medium containing 10 ng liter−1 Hg(II). The concentrations of phosphate and (NH4)2SO4 in the media were as follows: data set 1, 67 mM and 9 mM; 2, 33.5 mM and 9 mM; 3, 17.5 mM and 9 mM; 4, 8.75 mM and 9 mM; 5, 67 mM and 4.5 mM; 6, 67 mM and 2.25 mM. Samples were incubated for 120 min prior to measurement. Error bars represent the standard deviations of two independent assays of triplicate samples (n = 6) (A) and two independent assays of duplicate samples (n = 4) (B).

Thus, abundance of the neutral species, HgPO4, was correlated with accumulation in one case (Fig. 1, left, 3, and 5), but not in another (Fig. 7), and the PitA transport system was not significant for Hg(II) accumulation in these bacteria (Fig. 6). While this outcome is a negative one, it is important to present such results, because the speciation calculations and the role of PitA in transport of other metals pointed to this transport system as a likely mechanism for Hg(II) uptake.

Implications for our understanding of Hg(II) accumulation in bacteria.

The method used in this work measures internal Hg(II) accumulation, which is not necessarily equivalent to uptake if loss of Hg(II) is occurring simultaneously. Such losses might occur if there is an efflux mechanism that operates at trace Hg(II) concentrations, increased binding to extracellular components, or decreased nonspecific reduction.

Efflux is known to play a role in the homeostasis of a wide range of divalent cations in eukaryotes and prokaryotes, including E. coli (20); however, they have not been demonstrated to transport trace concentrations of Hg(II). Preliminary evidence against efflux of Hg(II) was provided from measurements of Hg(II) accumulation in the presence of various concentrations of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone, which revealed no increase in the accumulation of Hg(II) under anaerobic conditions in E. coli (14). Increased accumulation could also be the result of decreased binding capabilities of the cells at lower pH. However, there were no apparent differences in Hg(II) binding to E. coli cells within the pH range of 5 to 8 (14). Total Hg(II) measurements of the samples containing bacteria at the different pHs (Flett Research Ltd.) also indicated that the increase in Hg(II) response at low pH was not a result of increased nonspecific reduction of Hg(II) in higher-pH samples or leaching of potential contaminant Hg(II) from the scintillation vials at low pHs (25).

We therefore consider that the enhanced accumulation of Hg(II) was a result of increased uptake into the cell. There is no known function for Hg(II) in cells, and so its uptake likely occurs by accidental means, such as being mistaken for some essential metal ion or being associated with some useful organic moiety. Because it was believed for many years that Hg(II) only entered bacterial cells by passive diffusion of neutral, lipophilic species (5, 19), the effort to elucidate mechanisms of facilitated uptake is in the beginning stages and warrants further examination.

The work presented here showed that pH enhances Hg(II) accumulation under anaerobic conditions. Enhancement has also been observed under aerobic conditions for both E. coli (14) and V. anguillarum (25). The main difference was that under anaerobic conditions at trace Hg concentrations (1 ng Hg/liter), very little accumulation occurred until the pH was decreased below 6 (Fig. 1, left), while aerobic accumulation was easily measured at pHs of >6 (24). To put the anaerobic results in perspective, it should be noted that at neutral pH, in the same assay media as used in this work, Hg(II) accumulation in cells was not measurable unless more than 50 ng Hg/liter was added (15). Thus, lowering the pH to below 6 had a similar effect on internal Hg(II) accumulation as increasing the external Hg(II) concentration by over 50 times. Whether or not the same means of accumulation was used under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions is unclear at this point. Under both growth conditions, a pH-dependent accumulation was observed.

E. coli HMS174 was used in these experiments because it is a derivative of strain K-12, one of the best-characterized bacterial strains and whose genome has been sequenced (7). It contains a variety of ubiquitous heavy metal divalent cation uptake systems (e.g., MntH [27] and ZupT [17]) and efflux (e.g., FieF [18]) systems to maintain heavy metal homeostasis. The broad range of organisms sharing components involved in heavy metal homeostasis with E. coli (including Archaea and Eukarya) make this organism a relevant model system for the investigation of intracytoplasmic mercury accumulation. It also helps explain why very similar observations were also made with V. anguillarum (15; this study). These findings could have applications in other Proteobacteria, including those found to methylate mercury (5).

Hg(II) methylation is predominantly a microbiological process that takes place in anaerobic habitats of aquatic systems. Any effect of pH on the internal concentration of Hg(II) by methylating bacteria would likely be seen in the overall methylation activity in these systems. Indeed, one environmental parameter that has consistently shown positive correlations with methylmercury concentration is pH (reviewed in reference 38). For example, in aquatic ecosystems where the pH tends to be low, e.g., wetlands, the methylmercury concentration tends to be high (26, 36). Such an increase in the methylmercury concentration in acidified lakes has been attributed to increased rates of bacterial Hg(II) methylation (8, 30, 41). The results from this study suggest that one of the reasons for this enhancement of methylation rates observed in some acidified waters could be the result of enhanced net intracellular accumulation of Hg(II), most likely due to enhanced uptake into the cells.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by Manitoba Hydro and NSERC.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barkay, T., M. Gillman, and R. R. Turner. 1997. Effects of dissolved organic carbon and salinity on bioavailability of mercury. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4267-4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkay, T., R. R. Turner, L. D. Rasmussen, C. A. Kelly, and J. W. M. Rudd. 1998. Luminescence facilitated detection of bioavailable mercury in natural waters, p. 231-246. In R. A. Rossa (ed.), Bioluminescence methods and protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Barkay, T., S. M. Miller, and A. O. Summers. 2003. Bacterial mercury resistance from atoms to ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:355-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard, S. J., R. Hashim, G. Wu, M. R. B. Binet, M. N. Hughes, and R. K. Poole. 2000. Evidence for the transport of zinc(II) ions via the Pit inorganic phosphate transport system in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benoit, J. M., C. C. Gilmour, and R. P. Mason. 2001. Aspects of bioavailability of mercury for methylation in pure cultures of Desulfobulbus propionicus (1pr3). Environ. Sci. Technol. 35:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankenhorn, D., J. Phillips, and J. L. Slonczewski. 1999. Acid- and base-induced proteins during aerobic and anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli revealed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol. 181:2209-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloom, N. S., C. J. Watras, and J. P. Hurley. 1991. Impact of acidification on the methylmercury cycle of remote seepage lakes. Water Air Soil Pollut. 56:477-491. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloom, N. S., and E. A. Crecelius. 1983. Determination of mercury in seawater at subnanogram per liter levels. Mar. Chem. 14:49-59. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown, N. L., Y.-C. Shih, C. Leang, K. J. Glendinning, J. L. Hobman, and J. R. Wilson. 2002. Mercury transport and resistance. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30:715-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caguiat, J. J., A. L. Watson, and A. O. Summers. 1999. Cd(II)-responsive and constitutive mutants implicate a novel domain in MerR. J. Bacteriol. 181:3462-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compeau, G. C., and R. Bartha. 1985. Sulfate-reducing bacteria: principle methylators of mercury in anoxic estuarine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:498-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condee, C. W., and A. O. Summers. 1992. A mer-lux transcriptional fusion for real-time examination of in vivo gene expression kinetics and promoter response to altered superhelicity. J. Bacteriol. 174:8094-8101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golding, G. R. 2005. Ph.D. thesis. University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

- 15.Golding, G. R., C. A. Kelly, R. Sparling, P. C. Loewen, J. W. M. Rudd, and T. Barkay. 2002. Evidence for facilitated uptake of Hg(II) by Vibrio anguillarum and Escherichia coli under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:967-975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golding, G. R., C. A. Kelly, R. Sparling, P. C. Loewen, and T. Barkay. 2007. Evaluation of mercury toxicity as a predictor of mercury bioavailability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41:5685-5692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grass, G., S. Franke, N. Taudte, D. H. Nies, L. M. Kucharski, M. E. Maguire, and C. Rensing. 2005. The metal permease ZupT from Escherichia coli is a transporter with a broad substrate spectrum. J. Bacteriol. 187:1604-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grass, G., M. Otto, B. Fricke, C. J. Haney, C. Rensing, D. H. Nies, and D. Munkelt. 2005. FieF (YiiP) from Escherichia coli mediates decreased cellular accumulation of iron and relieves iron stress. Arch. Microbiol. 183:9-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutknecht, J. 1981. Inorganic mercury (Hg2+) transport through lipid bilayer membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 61:61-66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haney, C. J., G. Grass, S. Franke, and C. Rensing. 2005. New developments in the understanding of the cation diffusion facilitator family. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32:215-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes, T. H., J. C. Wilks, P. Sanfilippo. E. Yohannes, D. P. Tate, B. D. Jones, M. D. Radmacher, S. S. BonDurant, and J. L. Slonczewski. 2006. Oxygen limitation modulates pH regulation of catabolism and hydrogenases, multidrug transporters, and envelope composition in Escherichia coli K-12. BMC Microbiol. 6:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins, C. F., C. J. Dorman, D. A. Stirling, L. Waddell, I. R. Booth, G. May, and E. Bremer. 1988. A physiological role for DNA supercoiling in the osmotic regulation of gene expression in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Cell 52:569-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hungate, R. E. 1969. A roll-tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes, p. 117-132. In J. R. Norris and D. W. Robbins (ed.), Methods in microbiology. Academic Press, London, England.

- 24.Ingraham, J. 1987. Effect of temperature, pH, water activity, and pressure on growth, p. 1543-1554. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 25.Kelly, C. A., J. W. M. Rudd, and M. H. Holoka. 2003. Effect of pH on mercury uptake by an aquatic bacterium: implications for Hg cycling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37:2941-2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly, C. A., J. W. M. Rudd, R. A. Bodaly, N. P. Roulet, V. L. St. Louis, A. Heyes, T. R. Moore, S. Schiff, R. Aravena, K. J. Scott, B. Dyck, R. Harris, B. Warner, and G. Edwards. 1997. Increases in fluxes of greenhouse gases and methyl mercury following flooding of an experimental reservoir. Environ. Sci. Technol. 31:1334-1344. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makui, H., E. Roig, S. T. Cole, J. D. Helmann, P. Gros, and M. F. Cellier. 2000. Identification of the Escherichia coli K-12 Nramp orthologue (MntH) as a selective divalent metal ion transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1065-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martell, A. E., and R. M. Smith. 2001. NIST critically selected stability constants of metal complexes database. U.S. Department of Commerce, Technology Administration, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD.

- 29.Maurer, L. M., E. Yohannes, S. S. Bondurant, M. Radmacher, and J. L. Slonczewski. 2005. pH regulates genes for flagellar motility, catabolism, and oxidative stress in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 187:304-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miskimmin, B. M., J. W. M. Rudd, and C. A. Kelly. 1992. Influence of dissolved organic carbon, pH, and microbial respiration rates on mercury methylation and demethylation in lake water. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 49:17-22. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morel, F. M. M., A. M. L. Kraepiel, and M. Amyot. 1998. The chemical cycle and bioaccumulation of mercury. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29:543-566. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ralston, D. M., and T. V. O'Halloran. 1990. Ultrasensitivity and heavy-metal selectivity of the allosterically modulated MerR transcription complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3846-3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selifonova, O., R. Burlage, and T. Barkay. 1993. Bioluminescent sensors for detection of bioavailable Hg(II) in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3083-3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaefer, J. K., J. Letowski, and T. Barkay. 2002. mer-mediated resistance and volatilization of Hg(II) under anaerobic conditions. Geomicrob. J. 19:87-102. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stancik, L. M., D. M. Stancik, B. S. Schmidt, D. M. Barnhart, Y. N. Yoncheva, and J. L. Slonczewski. 2002. pH-dependent expression of periplasmic proteins and amino acid catabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:4246-4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.St. Louis, V. L., J. W. M. Rudd, C. A. Kelly, K. G. Beaty, N. S. Bloom, and R. J. Flett. 1994. Importance of wetlands as sources of methyl mercury to boreal forest ecosystems. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 51:1065-1076. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker, D. L., N. Tucker, and T. Conway. 2002. Gene expression profiling of the pH response in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:6551-6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulrich, S. M., T. W. Tanton, and S. A. Abdrashitova. 2001. Mercury in the aquatic environment: a review of factors affecting methylation. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 31:241-293. [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Veen, H. W. 1997. Phosphate transport in prokaryotes: molecules, mediators and mechanisms. Antonie Leewenhoek 72:299-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Veen, H., T. Abee, G. J. J. Kortstee, W. N. Konings, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1994. Translocation of metal phosphate via the phosphate inorganic transport system of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 33:1766-1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xun, L., N. E. R. Campbell, and J. W. M. Rudd. 1987. Measurement of specific rates of net methyl mercury production in the water column and surface sediments of acidified and circumneutral lakes. Can. J. Fish Aquat. Sci. 44:750-757. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yohannes, E., D. M. Barnhart, and J. L. Slonczewski. 2004. pH-dependent catabolic protein expression during anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 186:192-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]