Abstract

Microbial degradation is the only sustainable component of natural attenuation in contaminated groundwater environments, yet its controls, especially in anaerobic aquifers, are still poorly understood. Hence, putative spatial correlations between specific populations of key microbial players and the occurrence of respective degradation processes remain to be unraveled. We therefore characterized microbial community distribution across a high-resolution depth profile of a tar oil-impacted aquifer where benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX) degradation depends mainly on sulfate reduction. We conducted depth-resolved terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting and quantitative PCR of bacterial 16S rRNA and benzylsuccinate synthase genes (bssA) to quantify the distribution of total microbiota and specific anaerobic toluene degraders. We show that a highly specialized degrader community of microbes related to known deltaproteobacterial iron and sulfate reducers (Geobacter and Desulfocapsa spp.), as well as clostridial fermenters (Sedimentibacter spp.), resides within the biogeochemical gradient zone underneath the highly contaminated plume core. This zone, where BTEX compounds and sulfate—an important electron acceptor—meet, also harbors a surprisingly high abundance of the yet-unidentified anaerobic toluene degraders carrying the previously detected F1-cluster bssA genes (C. Winderl, S. Schaefer, and T. Lueders, Environ. Microbiol. 9:1035-1046, 2007). Our data suggest that this biogeochemical gradient zone is a hot spot of anaerobic toluene degradation. These findings show that the distribution of specific aquifer microbiota and degradation processes in contaminated aquifers are tightly coupled, which may be of value for the assessment and prediction of natural attenuation based on intrinsic aquifer microbiota.

The fate of organic contaminants in groundwater environments is controlled by a multitude of abiotic and biotic processes, such as transport, dilution, dispersion, and chemical or microbial degradation. The last is considered the only sustainable component of natural attenuation (9, 46). Due to large carbon loads and the low rates of oxygen replenishment to groundwater systems, oxygen is rapidly depleted upon contaminant impact (2). Therefore, within hydrocarbon-contaminated aquifers, anoxic contaminant plumes with distinct redox compartments are formed, where microbial guilds capable of using locally available electron donors and acceptors are active (9). Biodegradation processes occur at different rates in these redox zones (46), but it is still poorly understood which plume compartments are most relevant for net contaminant removal. Especially, overlapping countergradients of electron donors and acceptors are assumed to be hot spots of biodegradation (3, 12, 53, 54), a hypothesis that has recently been summarized as the “plume fringe concept” (4). Such redox gradients may be extant on very fine spatial scales; thus, a detailed characterization of redox species and intrinsic microbiota at appropriate spatial resolutions is a prerequisite for a better understanding of biodegradation processes.

It is especially relevant to ask how the spatial distribution of plume compartments and degradation processes is correlated to local microbial communities in general and whether the distribution of specific contaminant degraders can inform us about the occurrence and localization of the respective processes. Local microbial community composition has been shown to yield important insights into the microbes characteristic of different contaminated zones, as well as into their putative involvement in specific transformation processes in aquifers (1, 13, 27, 39). However, the monitoring of microbial capacities and their distribution at contaminated sites as a basis for assessing natural attenuation and for promoting biota-based site management options is still in its infancy. This may be attributed partially to the fact that conventional multilevel groundwater sampling is performed usually with a depth resolution of meters (24, 49). This spatial resolution has been suggested to be inadequate for truly assessing ongoing natural attenuation processes (57).

In this study, to address these questions, we have characterized microbial community distribution across a high-resolution depth profile of a tar oil-impacted aquifer at a former gasworks location, where hydrocarbon degradation has been reported to depend mainly on sulfate reduction (14, 59). We have specifically traced as a model system intrinsic populations of anaerobic toluene degraders by using their benzylsuccinate synthase (bssA) genes as specific catabolic markers (58). Benzylsuccinate synthase (Bss) is the key enzyme of anaerobic toluene oxidation and has repeatedly been proven to be a valuable functional marker gene for unknown anaerobic toluene degraders (6, 55, 58). Thus, we have shown for the Flingern site in Düsseldorf, Germany, that local anaerobic toluene degraders are dominated by an as-yet unaffiliated lineage of environmental bssA genes, tentatively termed “F1-cluster” bssA, which has ∼90% amino acid similarity to known geobacterial bssA genes (58). However, the identities of the degraders carrying these bssA genes, as well as their quantitative distribution and relevance for net toluene degradation in the contaminant plume, remain to be addressed.

At the site, we have collected sediment cores and installed a unique high-resolution multilevel monitoring well (3). Using fine-scale hydrogeochemical measurements as well as spatially resolved qualitative and quantitative molecular microbial community analyses, we show that a highly specialized degrader community, as well as a surprisingly high abundance of specific anaerobic toluene degraders, resides within the biogeochemical gradient zone underneath the plume core. These findings show that the distribution of specific aquifer microbiota and redox and degradation processes in contaminated aquifers are tightly coupled.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description, sediment sampling, and biogeochemical measurements.

Subsurface samples from a tar oil-contaminated former gasworks site in Düsseldorf-Flingern, Germany (14, 26, 59), were obtained from fresh sediment cores taken during the installation of high-resolution multilevel well (HR-MLW) 19222 in June 2005. A precise description of the well and its installation is detailed elsewhere (3). Triplicate sediment subcores were taken at different depths from the liners originating from between 5.7 and 12.7 m below ground surface (bgs) (the groundwater table was ∼6.4 m bgs) by use of sterile 50-ml plastic tubes. Subsamples were immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −20°C until DNA extraction. Groundwater samples for the analysis of contaminants and redox species were sampled from HR-MLW 19222 in September 2005. Dissolved toluene, sulfide, and ferrous iron in depth-resolved groundwater samples as well as sedimentary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and ferrous iron were measured as described elsewhere (3).

Nucleic acid extraction.

Independent DNA extracts from triplicate sediment subsamples were extracted from 19 depths between 5.7 and 12.7 m bgs. These depths covered all major redox compartments of the Flingern aquifer as well as one sample from the unsaturated zone (5.7 m) and one from the capillary fringe (6.3 m). DNA was extracted from freshly thawed ∼1-g (∼500-μl) aliquots of sediment material using a modification of a previously described protocol (35). Samples were suspended in 650 μl PTN buffer (120 mM Na2HPO4, 125 mM Tris, 0.25 mM NaCl [pH 8]) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min with 40 μl lysozyme (50 mg ml−1) and 10 μl proteinase K (10 mg ml−1). After the addition of 200 μl 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate, incubation was continued for 30 min at 65°C. Subsequently, the sediments were bead beaten (45 s at 6.5 ms−1) with ∼0.2 ml of zirconia-silica beads (a 1:1 mix of 0.1- and 0.7-mm diameter; Roth) in 2-ml screw-cap vials. Afterwards nucleic acids were sequentially purified by extraction with 1 volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and 1 volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) and precipitated with 2 volumes of 30% polyethylene glycol (17) by incubation at 4°C for 2 h and by centrifugation at 20,000 × g and 20°C for 30 min. All reagents were from Sigma, if not otherwise stated. For each single extract, two replicate extractions were pooled in 25 μl of elution buffer (Qiagen) and stored frozen (−20°C) until further analyses.

qPCR.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) measurements were performed on a MX3000P qPCR cycler (Stratagene). For each sediment depth, the three independent DNA extracts from sediment subsamples were quantified in three different dilutions (1:5, 1:10, and 1:20) to account for the possibility of PCR inhibition in less diluted templates. Total bacterial 16S rRNA gene quantities were measured using a previously described Sybr green PCR (51) with minor modifications. We used standard Taq polymerase (Fermentas) assays in the presence of 0.1× Sybr green (FMC Bio Products) and 2 μl DNA template. Initial denaturation (94°C, 3 min) was followed by 50 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 15 s), annealing (52°C, 15 s), and elongation (70°C, 30 s). Subsequently, a melting curve was recorded between 55°C and 94°C to discriminate between specific and unspecific amplification products. An almost-full-length bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicon of Azoarcus sp. strain T (22) genomic DNA was quantified using the PicoGreen double-stranded DNA quantification kit (Molecular Probes) and utilized as standard DNA for qPCR in a concentration range between 107 and 101 copies μl−1.

For bssA qPCR, a TaqMan system for the previously identified F1 cluster of unidentified bssA genes (58) was developed (Table 1). We also developed an analogous assay for the bssA gene of “Aromatoleum aromaticum” strain EbN1 (23, 60). Primer and probe designs were conducted with Primer3 software v.0.3.0. (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). bssA qPCR was performed with the TaqMan universal master mix kit (Applied Biosystems), as specified by the manufacturer, using three-step thermal cycling (95°C, 10 min; and 50 cycles of 95°C, 15 s; 55°C, 20 s; and 72°C, 30 s) and 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) and 3′-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine dual-labeled probes (Biomers). A PicoGreen-quantified M13 amplicon of the F1-cluster partial bssA gene clone D12-03 (GenBank accession no. EF123678) previously retrieved from Flingern sediments and an almost-full-length bssA amplicon of “A. aromaticum” strain EbN1 were taken for standardization in concentrations between 107 and 101 copies μl−1. PCR amplification efficiencies deduced from the slopes of standardization curves for different runs of 16S rRNA and bssA gene qPCR were 85% and 79% on average, respectively.

TABLE 1.

qPCR primer and TaqMan probe sets used in this study for the quantification of defined bssA gene copy numbers in sediment DNA extracts

| Specificity (reference) | Primer or probe | 5′-3′ sequence | Locationa |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1-cluster bssA (58) | bssApd2f | CCT ATG CGA CGA GTA AGG TT | 8235-8254 |

| bssApd2r | TGA TAG CAA CCA TGG AAT TG | 8416-8435 | |

| bssApd2h | TCC TGC AAA TGC CTT TTG TCT CAA | 8295-8318 | |

| “Aromatoleum aromaticum” strain EbN1 bssA (23) | BssN2f | GGC TAT CCG TCG ATC AAG AA | 7904-7923 |

| BssN2r | GTT GCT GAG CGT GAT TTC AA | 8109-8128 | |

| BssN2h | CTA CTG GGT CAA TGT GCT ATG CAT G | 8005-8029 |

Primer and probe locations are given according to Thauera aromatica K172 bss operon nucleotide numbering (25).

To correct for potentially distinct amplification/detection efficiencies of the different qPCR assays (i.e., Sybr green versus TaqMan PCR assays) and also for putative extraction/detection efficiencies of our general workflow, defined biomass amendments were evaluated for the Flingern sediments. For this, sediments were sterilized overnight at 180°C to eliminate intrinsic nucleic acids. Then, sediments were rewetted with sterile water and amended with defined cell numbers of a freshly grown, Sybr green-counted liquid culture of “A. aromaticum” EbN1 between 8 × 105 and 8 × 106 cells g−1 (wet weight) of sediment. Care was taken to adjust the sediments to the original water contents. Strain EbN1 carries four rrn operons and one bss operon per genome (23, 42). Nucleic acids were reextracted and quantified as described above. From the detected-versus-expected gene quantities, correction factors for the 16S rRNA and bssA gene counts directly obtained from Flingern sediments were inferred. Negative controls showed that heat sterilization destroyed over 99.99% of the initial 16S rRNA gene counts.

Microbial community fingerprinting.

Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis of bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicons was done as previously described (34) with primers Ba27f-FAM and 907r (40, 56) and MspI digestion. Primary electropherogram evaluation was performed using GeneMapper 5.1 software (Applied Biosystems). T-RF frequencies were inferred from peak heights (33). Signals with a peak height below 100 relative fluorescence units (41) or with a peak abundance contribution below 1% (36) were considered background noise and excluded from further analysis. The reproducibility of our T-RFLP assay was verified via replicate determination of T-RF abundances from two independent DNA extracts of three exemplary depths (6.3 m, 6.8 m, and 7.6 m bgs). T-RF abundances were highly reproducible, with an average standard deviation of 1.1% relative T-RF abundance (variations were between 0% and maximally 5.9% standard deviation for specific T-RFs). The Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H′) was calculated as H′ = −Σ pi ln pi, where pi is the relative abundance of single T-RFs in a given fingerprint (19).

For statistics, T-RFLP data were evaluated as previously described (32, 43) using SYSTAT 10 software (SPSS, Inc.). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on T-RFLP relative peak abundance data. A covariance data matrix was extracted with pairwise deletion and no factor rotation. Data reduction provided a two-factorial PC ordination of the overall variance of the T-RFLP profiles. Additionally, a loading plot of inferred PC factors on specific T-RFs was generated to identify the T-RFs especially correlated to the discrimination of depth-resolved microbial community fingerprints in PCA ordination.

Cloning, sequencing, and phylogenetic analyses.

Almost-full-length bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicons were generated from the DNA extracts of four different depths (6.3 m, 6.8 m, 7.6 m, and 11.7 m) using the primer set Ba27f and 1492r (56). Amplicons were cloned and sequenced as previously described (58). Sequencing reads were manually assembled and checked for quality using SeqMan II software (DNAStar). All clones were subsequently screened for similarities to published sequences using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) and integrated into an ARB database (31). All clone sequences were checked for chimeric nature with Chimera Check 2.7 of the Ribosomal Database Project II version 8.1 (http://rdp8.cme.msu.edu/html/) and by manual inspection of the alignment. From 151 clones, 6 were identified as chimeras and excluded from further analysis. For phylogenetic affiliation, trees including clones and closely related representative sequences (>1,400 bp) of cultivated and uncultivated species were constructed using neighbor-joining algorithms. Highly variable regions within the 16S rRNA were omitted from analysis by the application of a 50% base frequency filter. T-RFs of cloned sequences were predicted using ARB_EDIT4. For a representative set of clones, T-RFs predicted in silico were verified by direct T-RFLP analysis of cloned amplicons to precisely assign observed environmental T-RFs to cloned lineages.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All clone sequences of this study were deposited with GenBank under accession numbers EU266776 to EU266920.

RESULTS

Depth distribution of contaminants and redox species in the plume.

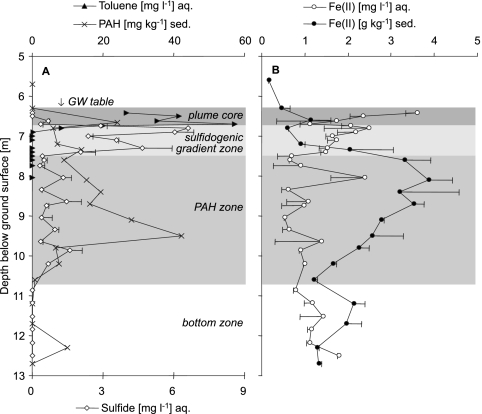

Sediment cores were taken at the tar oil-contaminated sandy aquifer in Düsseldorf-Flingern, Germany, in the course of the drilling and installation of an HR-MLW in June 2005 (3). Upon subsequent groundwater sampling in September 2005, the HR-MLW revealed steep gradients of contaminants and redox species over the depth transect. In Fig. 1, the depth-resolved distribution of the most prominent benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX) compound at the site, toluene, is displayed together with the reduced electron acceptors sulfide and ferrous iron in groundwater, as well as sedimentary PAHs and ferrous iron. In the upper 30 cm of the saturated zone, toluene concentrations averaged ∼40 mg liter−1 and thus defined a highly contaminated plume core directly beneath the groundwater table. Toluene contributed approximately two-thirds of the total BTEX concentrations detected within these depths. Underneath this plume core, an ∼65-cm-wide gradient zone, characterized by a strong decrease in contaminant concentrations and elevated levels of sulfide, was identified between 6.75 and 7.4 m bgs. These biogeochemical data indicated that this “sulfidogenic gradient zone” (Fig. 1) was a “hot spot” of BTEX degradation within the plume at the time of the sampling. Previous investigations indicated that sulfate reduction dominated contaminant degradation at the site (3, 14, 59). The gradient zone was also characterized by slightly elevated concentrations of ferrous iron in groundwater (Fig. 1B), but distinction to other zones was not as clear. Readily extractable ferric iron, however, was not detectable in significant amounts in sediments below the capillary fringe (data not shown). All BTEX compounds were below the detection limit under a depth of ∼8 m.

FIG. 1.

Depth profiles of representative aromatic contaminants (A) and reduced electron acceptors (A and B) in sediment samples (sed.) and groundwater (aq.) from the Flingern aquifer. Samples were taken in June (sed.) and September (aq.) 2005. Error bars indicate the means of duplicate measurements, and the absence of error bars indicates single measurements. Plume and redox compartments were specified in accordance with the biogeochemical data. GW, groundwater.

Beneath the strongly sulfidogenic gradient zone, increased microbial activities were still inferable from free sulfide and especially sedimentary ferrous iron concentrations. Contaminants other than BTEX, i.e., PAHs, were found sorbed to the sediments down to ∼10 m bgs, but also below that depth (Fig. 1A). This points toward a distinct, mainly PAH-contaminated zone (∼7.5 m to ∼10.7 m). Naphthalene and fluorene contributed the major mass of the PAHs identified by EPA standards. Free sulfide was below the detection limit in depths beneath 10.2 m. We thus defined the remaining sampling depth down to the underlying aquitard (∼10.7 m to 12.7 m) as a still reduced, but less contaminated, bottom zone of the Flingern aquifer.

Quantitative distribution of bacteria and anaerobic toluene degraders.

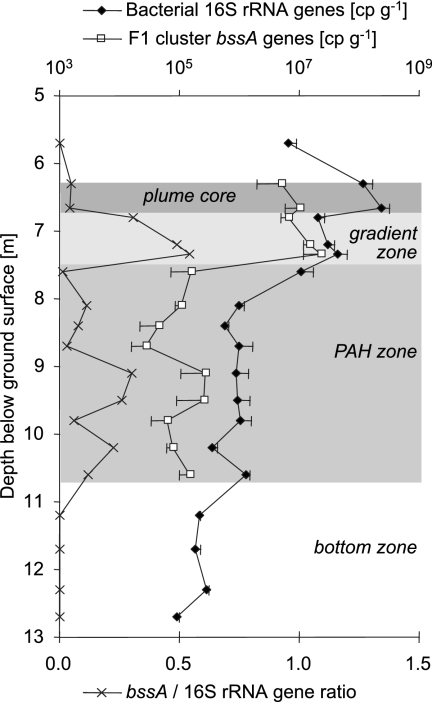

We previously detected microbes carrying an as-yet unaffiliated type of putative deltaproteobacterial bssA gene (termed the F1 cluster) that dominated the community of anaerobic toluene degraders in the Flingern aquifer (58). To correlate the quantitative distribution of the F1-cluster microbes to those of contaminant and redox species and total bacterial populations, depth-resolved qPCR quantifications were conducted. First, however, it was necessary to validate the comparative extraction/detection efficiencies of the employed qPCR assays (16S rRNA gene Sybr green PCR versus bssA TaqMan PCR). For this, we added defined cell numbers of the denitrifying anaerobic toluene degrader “Aromatoleum aromaticum” EbN1 to heat-sterilized Flingern sediments. While expected bssA abundances were almost absolutely recovered at ∼8 × 106 added cells g−1 sediment, 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were significantly underrepresented by a factor of ∼6. The inferred correction factor was 5.5 ± 0.6 for the expected-versus-detected 16S rRNA/bssA gene frequencies over several orders of magnitude of cell biomass amendment. This factor was used to deduce corrected gene quantities from field qPCR measurements (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Depth distribution of bacterial 16S rRNA genes and bssA genes of the F1 cluster of unknown anaerobic toluene degraders (58) as measured via qPCR. Shown are the means of gene cp g−1 sediment (wet weight) ± standard errors of three independent DNA extracts for each depth.

Bacterial rRNA genes were detected in all depths and peaked at a maximum of 2.4 ± 0.8 × 108 copies per g sediment (cp g−1) directly within the plume core (6.65 m bgs). 16S rRNA gene quantities were generally above 107 cp g−1 in the upper zones of the aquifer (plume core and sulfidogenic zone) and dropped drastically in the PAH and bottom zones. Abundance distributions varied least within the PAH zone at a depth between 8.7 m and 9.8 m. In contrast to bacterial rRNA genes, the quantitative distribution of bssA genes peaked at 2.3 ± 0.1 × 107 cp g−1 within the sulfidogenic gradient zone but not within the plume core. The sulfidogenic zone was generally characterized by high bssA/16S rRNA gene ratios, ranging between 0.3 and 0.5 (Fig. 2). Moreover, F1-cluster bssA genes were not detectable by TaqMan PCR (detection limit, ∼5 × 103 cp g−1) in sediments deeper than 11 m or above 6 m. Thus, their detection was highly correlated to saturated anaerobic contaminated sediments. Furthermore, by bssA-targeted T-RFLP fingerprinting with a previously published general primer set (58), we could show that the F1 cluster of bssA genes strongly dominated all bssA populations detected in the Flingern aquifer (data not shown).

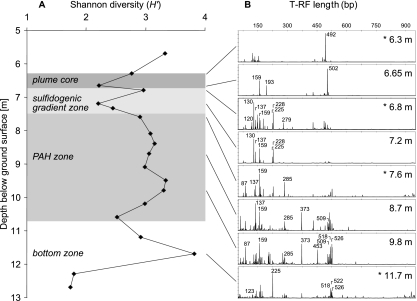

Depth-resolved shifts in bacterial communities.

Structural shifts in depth-resolved microbial communities were assessed via T-RFLP fingerprinting (Fig. 3). Fingerprinting data indicated strong changes in the diversity and composition of bacterial communities detectable by fingerprinting. The Shannon-Wiener diversity indexes (H′) as inferred from relative T-RF abundances dropped to local minima within the highly contaminated plume core (6.6 m bgs), in the sulfidogenic gradient zone (7.2 m), and between the PAH and bottom zones (10.6 m) (Fig. 3A). As with absolute gene quantities, diversity indexes varied least throughout the PAH-contaminated zone. H′ reached both the absolute maximum and minimum within the bottom zone.

FIG. 3.

Depth-resolved 16S rRNA gene T-RFLP fingerprinting of bacterial community structures in plume compartments of the Flingern aquifer. (A) Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H′) calculated for the entire T-RFLP data set. (B) Representative T-RFLP electropherograms of selected depths. Community patterns marked by an asterisk were subsequently selected for cloning. Selected characteristic T-RFs mentioned in the text are indicated by their base pair lengths.

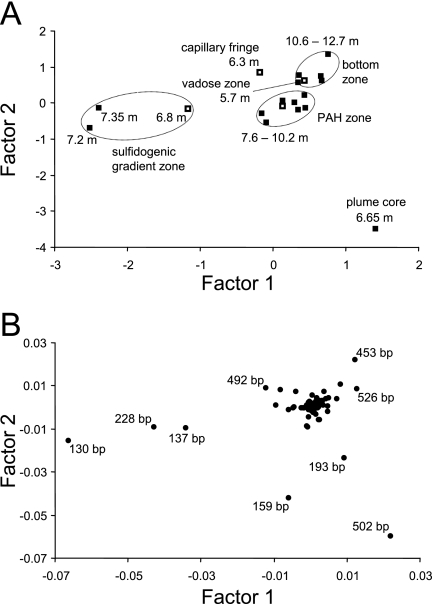

Not only the diversity, but also the structural composition (i.e., the identity [bp] and relative abundance of detected T-RFs) of fingerprints, indicated that significant community shifts were occurring with depth. To better visualize these population shifts and to identify specific T-RFs characteristic for respective zones, PCA of T-RFLP data was conducted (Fig. 4A). The percentage of total community variability explained by the two primary PC factors inferred was only ∼40%. This finding emphasizes the large variations in depth-resolved community structures evident already by visual inspection of the fingerprints (Fig. 3). The resulting limitations of reducing this variability to only a few virtual factors clearly caution the capability of our two-factorial PCA to explain overall microbial community variability in the Flingern aquifer. Nevertheless, data reduction clearly grouped fingerprints from different plume zones into distinct clusters and thus was able to recover some of the most relevant variations. Especially, populations from the sulfidogenic zone were separated in ordination from other samples, indicating distinct populations in these strata. Communities from the PAH and bottom zones were more related to each other and formed two adjacent clusters in PCA. Outliers were observed for the capillary fringe and especially the plume core, while the vadose zone community clustered together with the PAH and bottom zone samples.

FIG. 4.

(A) PC ordination of the overall variance in depth-resolved bacterial community composition as analyzed by T-RFLP fingerprinting. The depths at which specific fingerprints were retrieved are indicated next to the ordination points. Communities marked by an open square were subsequently selected for cloning. Inferred PC factors 1 and 2 accounted for 21.3% and 18% of total variance, respectively. (B) Loading plot of inferred PC factors on specific T-RFs. The identities (bp) of selected T-RFs with characteristic factor loading are indicated.

The loading plot of inferred PC factors (Fig. 4B) helped us to identify the specific T-RFs responsible for the distinct PCA ordination of fingerprints. Hence, the sulfidogenic zone samples were characterized by high relative abundances of especially the 130-bp T-RFs, but also the 137- and 228-bp T-RFs. Also, the 225- and 279-bp fragments were abundant in these communities (Fig. 3B), but not PCA discriminators from other depths. The ordination of the plume core fingerprint was correlated to high abundances of the 502- and 193-bp T-RFs, but also the 159-bp T-RFs. The last was ordinated between the plume core, sulfidogenic zone, and PAH zone samples and thus represents an important constituent of all these communities, as confirmed also by the visual inspection of electropherograms (Fig. 3B). Fragments characteristic for the PAH zone were not detectable in PCA ordination, since most remaining T-RFs clustered near zero in ordination space. Nevertheless, their high relative abundances allowed us to identify the 87-, 137-, 159-, 285-, 373-, 509-, 518-, and 526-bp fragments as important within this zone (Fig. 3B).

Bacterial 16S rRNA clone libraries from four depths.

To phylogenetically characterize the distinct microbial assemblages intrinsic to the different plume compartments and to identify putative community members represented by the identified characteristic T-RFs, four clone libraries were constructed. Overall, we sequenced 145 full-length bacterial 16S rRNA gene clones from the depths of 6.3 m bgs (capillary fringe), 6.8 m bgs (sulfidogenic zone), 7.6 m bgs (PAH zone), and 11.7 m bgs (bottom zone). The relative phylum-level composition of the clone libraries revealed surprisingly significant distinctions in local community assembly, as summarized in Table 2. Alphaproteobacteria were found almost exclusively at the capillary fringe (6.3 m), where they dominated the library together with members of the Betaproteobacteria. Deltaproteobacteria, which were frequent in all other libraries, were not detected at 6.3 m. Members of the Betaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, and Clostridia appeared especially frequently in the library of the sulfidogenic gradient zone (6.8 m). Members of the Deltaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Chloroflexi were abundant in the PAH zone library, while Betaproteobacteria were missing there. The bottom zone library (11.7 m) contained the most even distribution of major bacterial phyla (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Relative phylum-level compositions of depth-resolved bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone libraries and selected genus- or lineage-specific clone frequencies

| Phylogenetic affiliationb | % of clones in indicated library at depth (bgs) ofc:

|

T-RF length (bp)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D10

|

D12

|

D15

|

D25

|

Predicted | Measured | |

| 6.3 m | 6.8 m | 7.6 m | 11.7 m | |||

| Alphaproteobacteria | 31 | 3 | NA | |||

| Methylocystis related | 3 | NA | ||||

| Betaproteobacteria | 26 | 19 | 14 | 123/492 | 120/492 | |

| Thiobacillus related | 6 | 6 | NA | |||

| Gallionella related | 6 | 6 | 123/125 | 120/122 | ||

| Gammaproteobacteria | 9 | NA | ||||

| Beggiatoa related | 6 | 138 | 135 | |||

| Deltaproteobacteria | 26 | 16 | 11 | NA | ||

| Desulfocapsa related | 6 | 162 | 159 | |||

| Geobacter related | 19 | 132 | 130 | |||

| Syntrophus related | 7 | 6 | 127/509 | 123/509 | ||

| Desulfobacterium related | 6 | 166 | 164 | |||

| Bacteroidetes | 6 | 14 | 91 | 87 | ||

| Nitrospirae | 3 | 7 | 8 | NA | ||

| Magnetobacterium related | 5 | 8 | 290 | 285 | ||

| Bacilli | 10 | 8 | 137 | 133 | ||

| Clostridia | 14 | 29 | 2 | 3 | NA | |

| Sedimentibacter related | 19 | 280 | 279 | |||

| Uncultured Peptococcaceae | 6 | 282 | 281 | |||

| Desulfosporosinus related | 3 | 227 | 225 | |||

| Desulfotomaculum related | 3 | 214 | ND | |||

| Actinobacteria | 3 | 3 | 16 | 11 | NA | |

| Rubrobacter related | 7 | 6 | 131/162 | 128/160 | ||

| Chloroflexi | 3 | 23 | 17 | NA | ||

| Uncultured I | 14 | 518 | 518 | |||

| Uncultured II | 3 | 21 | 3 | 373/454/523 | 373/453/522 | |

| Dehalococcoides related | 2 | NA | ||||

| TM6 | 9 | NA | ||||

| OP5 | 7 | 230 | 224 | |||

| OP10 | 7 | 3 | NA | |||

| TM7/OP11 | 3 | 9 | NA | |||

| Others | 3 | 3 | 12 | 8 | NA | |

Characteristic T-RF lengths (bp) predicted from the sequence data for all or a major portion of the clones of a given affiliation are indicated together with T-RF lengths actually measured in T-RFLP analysis. Values separated by a slash indicate more than one characteristic T-RF for a lineage. NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

The naming of phyla without cultivated representatives is in accordance to reference 44.

The libraries at 6.3, 6.8, 7.6, and 11.7 m contained 35, 31, 43, and 36 clones, respectively. Division-level percentages (given in bold) include the genus- or lineage-specific percentages (nonbold).

A considerable diversity of clones closely related to defined genera or lineages well-known to be capable of characteristic catabolic or respiratory activities was detected. Sequences related to known methylotrophs, sulfur- and ferrous iron-oxidizers were found especially at the capillary fringe. The sulfidogenic zone library contained high frequencies of clones between 95 and 97% related to Geobacter chapellei, a well-known deltaproteobacterial iron reducer (10). Furthermore, clones affiliated with the Desulfocapsa-related sulfate-reducing strain TRM1 (38) were found in this library. For these two lineages, signature T-RFs of 130 and 159 bp were inferable (Table 2). The library was also characterized by a high ratio of Clostridia. These Sedimentibacter- and Desulfosporosinus-related Clostridia were represented within the 279- and 225-bp T-RFs, respectively. Desulfobacterium-related clones (164-bp T-RF) and Syntrophus-related clones (123 and 509 bp) were detected only in the libraries from the one and two deepest samples, respectively. Clones related to the unusual iron reducers of the genus “Candidatus Magnetobacterium” (285 bp) within the Nitrospirae (50) were detected only in samples deeper than the sulfidogenic zone. Other observed signature T-RFs for the sampled metacommunity were 87 bp (different members of the Bacteroidetes), 120 and 492 bp (different Betaproteobacteria), 133 bp (different Bacilli), 224 bp (OP5 candidate division), and 373, 453, 518 and 522 bp (different uncultured Chloroflexi).

Rarefaction analyses of the bacterial communities retrieved within the clone libraries showed that coverage of the libraries was by far insufficient, at both 95% sequence similarity (at the genus level) and at the phylum-level diversity cutoff (data not shown). This was expected, but the aim of this study was not to fully cover the diversity of the distinct microbial communities retrieved from the different plume compartments but to highlight the most significant distinctions.

DISCUSSION

Geochemical and microbial zonation in the Flingern plume.

In this study, we provide a fine-scale molecular characterization of the distinct microbial assemblages found within defined contaminant and redox compartments of the Flingern BTEX plume. We link microbial data based on nucleic acid extracts of aquifer sediments to groundwater and sediment geochemical data obtained from the same site, an approach which has previously been shown to provide valuable insights into aquifer microbiota/process correlations (5, 13, 18). The present study regards these couplings in fine spatial resolution, with sampling intervals ranging between 5 and 15 cm in zones of special interest and between 30 and 60 cm in deeper zones. Conventional multilevel wells usually have a spatial resolution in the range of meters (13, 24, 49, 57), but geochemical gradients formed by microbial activities can be expected to prevail at much smaller scales within contaminated aquifers (3, 12, 53). Thus, low-resolution groundwater samplings may fail to identify the defined strata where electron donors and acceptors meet and provide only insufficient information on the biogeochemical and microbiological characteristics of such hot spots of degradation.

With this high-resolution sampling, we were able to identify a zone of strong sulfidogenic activities underneath the actual BTEX plume core, a zone in which sulfate-dependent degradation activities are likely to be of special relevance (3). qPCR analysis (Fig. 2) showed that this zone was characterized by significantly increased absolute and relative abundances of the yet unidentified microbes represented by the F1-cluster bssA genes previously detected at the site (58). The quantitative distribution of this catabolic gene by depth did not correspond to that of rRNA genes. In the core of the plume, where absolute rRNA gene abundance was highest, the inferred bssA/16S rRNA gene ratio was only ∼0.04. Within the next few decimeters, this ratio increased to values between ∼0.3 and ∼0.5, concomitant to the observed increase of sulfide. This increase points toward the establishment of a highly specialized anaerobic toluene degrader community underneath the actual plume core. These findings support the presumed “plume fringe concept,” which postulates that biodegradation of groundwater contaminants occurs mostly within the biogeochemical gradients surrounding contaminant plumes (3, 4, 12, 53, 54). Here, we provide supportive field data for anaerobic toluene degradation proceeding specifically via Bss. The importance of aerobic toluene degradation at the capillary fringe, or of other degradation and fermentation processes that may have sustained the high total biomass counts in the plume core, however, cannot be explained with our present data and requires further attention.

Furthermore, we must caution that although the measured distribution profiles of both rRNA and bssA genes can be expected to be reliable, the absolute gene counts and hence also specific gene ratios may yet be biased. We have corrected for putative extraction and detection biases by analyzing defined biomass amendments of strain EbN1. However, while the inferred correction factor may hold true for strain EbN1, it may still be biased for F1-cluster organisms. In fact, the corrected relative bssA/rRNA gene ratios of up to 0.5 in the sulfidogenic zone still seem quite high, assuming that oligotrophic groundwater microbiota will typically have one or two rrn operons and that degraders will carry one bss operon. Nevertheless, the depth-resolved differences in the distribution of both markers will remain constant, clearly emphasizing the increased relative abundance of anaerobic toluene degraders within the sulfidogenic zone.

Identification of zone-specific microbiota.

We applied complementary fingerprinting and sequencing strategies to unravel the correlations between local microbial community patterns and biogeochemical processes in different compartments of the Flingern plume. Within the upper parts of the contaminated aquifer (capillary fringe, plume core, and sulfidogenic zone), where bacteria were generally more abundant than in the deeper zones, repeated significant shifts and drops in community diversity were observed on very small scales. This corroborates the existence of distinct local communities in these strata which are specifically selected for by the local contaminant and redox regimen. It is currently not known on what time scales such specialized assemblages establish or how reactive they are to hydraulic dynamics or inputs of distinct electron acceptors (18, 37). Nevertheless, this spatial selection of distinct communities may be very relevant for contaminant degradation.

Direct spatial correlations between aquifer microbial community structure and contaminant scenarios have been previously recognized (1, 13, 16, 27). However, correlations between aquifer geochemistry and microbial communities are extremely complex, and statistical tools are needed to unravel these relations (1, 39, 47). Here, we were able to actually identify distinct aquifer microbiota characteristic for the resolved plume compartments. This identification relies on a satisfactory precision in linking T-RFs observed in environmental fingerprints to T-RFs of cloned sequences. Generally, incongruencies of ± 2 to 3 bp between predicted and measured T-RFs have to be taken into account (21, 28, 33), even if T-RFLP electrophoresis and T-RF sizing conditions are optimized with utmost caution (52). Therefore, we verified predicted T-RFs for representative clone sequences. Average differences between predicted and measured T-RFs in our analyses were −2.6 ± 1.7 bp (Table 2).

The sulfidogenic zone sediments were characterized by high relative abundances of especially the 130-bp T-RFs, but also the 137-, 159-, 225-, and 228-bp T-RFs (Fig. 3 and 4). Via sequence data from the respective clone libraries, we could clearly affiliate the 130-bp T-RF to the Geobacter relatives detected only in the sulfidogenic zone library. It is striking that these well-known iron reducers were not retrieved in libraries from other zones of the Flingern aquifer. The 130-bp T-RF, however, was detected also in some fingerprints of the PAH zone, albeit at low frequencies. Furthermore, microbes affiliated with the Desulfocapsa-related sulfate-reducing contaminant degrader TRM1 (38) (159-bp T-RF), as well as clostridial sulfate reducers (45) and fermenters (7) (225 and 279 bp), were abundant in this zone. Unfortunately, a clear affiliation of the 137- and 228-bp fragments to clones retrieved within the sulfidogenic zone was not possible. Although these T-RFs were predicted for different Bacilli and Clostridia within our clone libraries (Table 2), they could not be verified by in vitro T-RFs. Thus, these apparent constituents of the Flingern community remain unidentified at present, potentially due to undersampling, and may possibly even represent fingerprinting artifacts (15). Along the same line, we must state that not all important T-RFs observed were recovered within our four libraries. Again, this may be an effect of our small clone libraries or of the different reverse primers used for both approaches. Certainly, this is also attributed to the fact that we did not clone and sequence amplicons from all relevant sediment depths, such as the plume core.

Nevertheless, the specific microbes characteristic for the sulfidogenic zone (deltaproteobacterial Geobacter and Desulfocapsa relatives and sulfate-reducing and -fermenting Clostridia) were in clear contrast to those characteristic for the capillary fringe (e.g., Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria, the latter especially represented by the 492-bp T-RF) and for deeper zones of the Flingern aquifer (e.g., Bacteroidetes, 87-bp T-RF; Magnetobacterium relatives, 285-bp T-RF; and Chloroflexi, 373-, 454-, 518-, and 526-bp T-RFs). High frequencies of deltaproteobacterial 16S rRNA genes within contaminated aquifer sediments have previously been described, especially for the iron reducers of the Geobacter genus (11, 27, 29, 30). Here, however, we show that close relatives of these well-known contaminant degraders codominate a sulfidogenic gradient zone together with relatives of deltaproteobacterial and clostridial sulfate reducers and fermenters, which may point toward a colocalization or an overlap of the respective redox processes in the Flingern aquifer.

Putative affiliation of the F1-cluster bssA genes.

The yet unaffiliated F1-cluster bssA genes (58) relatively and absolutely dominated in the sulfidogenic gradient zone. Thus, it seems fair to assume that the corresponding microbes will have also been detected in respective 16S rRNA gene analyses. We have previously identified the F1-cluster bssA genes as ∼90% related to known geobacterial bssA and only ∼75% related to the TRM1 bssA gene (58). At the same time, it was shown for a distinct site that our employed general bssA primer set is well capable of detecting typical geobacterial bssA genes when they are present (58). These facts allow the formulating of the following hypotheses on the putative affiliation of the F1-cluster bssA genes.

They may belong to the detected Geobacter relatives, which also have their respective clone and T-RF abundance distribution maxima in this zone. This would then imply that these local populations carry bssA genes more distinct from typical geobacterial bssA genes (20, 58). Concomitantly, the dominance of these specific degraders in the sulfidogenic gradient zone would imply that toluene degradation in these strata may not be as directly linked to sulfate reduction (or to typical sulfate reducers) as previously assumed (3, 14, 59). Up to now, no Geobacter isolate has been shown capable of reducing sulfate. However, some can reduce elemental sulfur (8) and thus could also be responsible for sulfide production. Nevertheless, at present we cannot exclude the possibility that the Flingern Geobacteraceae, if they carry the F1-cluster bssA genes, may well have the means of transferring electrons from toluene to sulfate. Although still a preliminary speculation, this possibility is supported by ongoing enrichment experiments in our laboratory, where Flingern toluene degraders carrying the F1-type bssA gene were detected in both sulfate-reducing as well as iron-reducing enrichment microcosms (U. Kunapuli, C. Winderl, R. U. Meckenstock, and T. Lueders, work in progress).

Alternatively, the F1 bssA genes could also stem from other deltaproteobacterial sulfate reducers found within the gradient zone. Hence, these sulfate reducers would carry bssA genes distinct from that of strain TRM1 (58), which would be acceptable, since the possibility of the horizontal gene transfer of such catabolic genes can also not be excluded (48, 58). At the same time though, this would imply that none of the detected Geobacter relatives carry bssA genes, which otherwise would have been detected. Regarding the specific allocation of these microbes to the BTEX degradation hot spot and also the closer phylogenetic affiliation of the F1 bssA genes to known geobacterial sequences, the first scenario seems more likely at present. This, however, must clearly be verified in detail by our ongoing investigations.

In summary, we show that a highly specialized degrader community, including a surprisingly high abundance of anaerobic toluene degraders, resides within the sulfidogenic gradient zone underneath the contaminant plume core of the Flingern aquifer. These findings support the “plume fringe” hypothesis, according to which the fringes of contaminant plumes are the actual hot spots of contaminant degradation (3, 4, 53, 54). Also, these findings substantiate that the distribution of specific microbes and redox and degradation processes in contaminated aquifers are tightly coupled and that locally established biotic degradation capacities may be relevant controls of contaminant degradation in aquifers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; contracts LU 1188/2-1, ME 2049/2-1, and GR 2107/1-2) within the research unit Analysis and Modeling of Diffusion/Dispersion-Limited Reactions in Porous Media (FOR 525) and by the Helmholtz Society. Sediment sampling at the Flingern site was financed by a grant from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF KORA no. 02WN0357).

We greatly acknowledge Lars Richters (Stadtwerke Düsseldorf) for support and for providing site and sampling access. We also thank Sabine Schäfer (GSF) for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, J. P., E. A. Atekwana, E. A. Atekwana, J. W. Duris, D. D. Werkema, and S. Rossbach. 2007. The microbial community structure in petroleum-contaminated sediments corresponds to geophysical signatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2860-2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, R. T., and D. R. Lovley. 1997. Ecology and biogeochemistry of in situ groundwater bioremediation. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 15:289-350. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anneser, B., F. Einsiedl, R. U. Meckenstock, L. Richters, F. Wisotzky, and C. Griebler. High-resolution monitoring of biogeochemical gradients in a tar-oil contaminated aquifer. Appl. Geochem., in press.

- 4.Bauer, R. D., Y. Zhang, P. Maloszewski, R. U. Meckenstock, and C. Griebler. Aerobic and anaerobic degradation in anoxic toluene plumes—2D microcosm studies. J. Contam. Hydrol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bekins, B. A., I. M. Cozzarelli, E. M. Godsy, E. Warren, H. I. Essaid, and M. E. Tuccillo. 2001. Progression of natural attenuation processes at a crude oil spill site. II. Controls on spatial distribution of microbial populations. J. Contam. Hydrol. 53:387-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beller, H. R., S. R. Kane, T. C. Legler, and P. J. Alvarez. 2002. A real-time polymerase chain reaction method for monitoring anaerobic, hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria based on a catabolic gene. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:3977-3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitenstein, A., J. Wiegel, C. Haertig, N. Weiss, J. R. Andreesen, and U. Lechner. 2002. Reclassification of Clostridium hydroxybenzoicum as Sedimentibacter hydroxybenzoicus gen. nov., comb. nov., and description of Sedimentibacter saalensis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:801-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caccavo, F., Jr., D. J. Lonergan, D. R. Lovley, M. Davis, J. F. Stolz, and M. J. McInerney. 1994. Geobacter sulfurreducens sp. nov., a hydrogen- and acetate-oxidizing dissimilatory metal-reducing microorganism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3752-3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen, T. H., P. L. Bjerg, S. A. Banwart, R. Jakobsen, G. Heron, and H. J. Albrechtsen. 2000. Characterization of redox conditions in groundwater contaminant plumes. J. Contam. Hydrol. 45:165-241. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coates, J. D., V. K. Bhupathiraju, L. A. Achenbach, M. J. McInerney, and D. R. Lovley. 2001. Geobacter hydrogenophilus, Geobacter chapellei and Geobacter grbiciae, three new, strictly anaerobic, dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducers. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coates, J. D., E. J. P. Phillips, D. J. Lonergan, H. Jenter, and D. R. Lovley. 1996. Isolation of Geobacter species from diverse sedimentary environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1531-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cozzarelli, I. M., B. A. Bekins, M. J. Baedecker, G. R. Aiken, R. P. Eganhouse, and M. E. Tuccillo. 2001. Progression of natural attenuation processes at a crude-oil spill site. I. Geochemical evolution of the plume. J. Contam. Hydrol. 53:369-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dojka, M. A., P. Hugenholtz, S. K. Haack, and N. R. Pace. 1998. Microbial diversity in a hydrocarbon- and chlorinated-solvent-contaminated aquifer undergoing intrinsic bioremediation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3869-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckert, P., F. Wisotzky, P. Obermann, O. Kracht, and H. Strauss. 2000. Natural bioattenuation and active remediation in a BTEX contaminated aquifer in Duesseldorf (Germany), p. 389-399. In P. L. Bjerg, P. Engesgaard, and T. D. Krom (ed.), Groundwater 2000. Balkema, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

- 15.Egert, M., and M. W. Friedrich. 2003. Formation of pseudo-terminal restriction fragments, a PCR-related bias affecting terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of microbial community structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2555-2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franzmann, P. D., W. J. Robertson, L. R. Zappia, and G. B. Davis. 2002. The role of microbial populations in the containment of aromatic hydrocarbons in the subsurface. Biodegradation 13:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths, R. I., A. S. Whiteley, A. G. O'Donnell, and M. J. Bailey. 2000. Rapid method for coextraction of DNA and RNA from natural environments for analysis of ribosomal DNA- and rRNA-based microbial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5488-5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haack, S. K., L. R. Fogarty, T. G. West, E. W. Alm, J. T. McGuire, D. T. Long, D. W. Hyndman, and L. J. Forney. 2004. Spatial and temporal changes in microbial community structure associated with recharge-influenced chemical gradients in a contaminated aquifer. Environ. Microbiol. 6:438-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill, T. C. J., K. A. Walsh, J. A. Harris, and B. F. Moffett. 2003. Using ecological diversity measures with bacterial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 43:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kane, S. R., H. R. Beller, T. C. Legler, and R. T. Anderson. 2002. Biochemical and genetic evidence of benzylsuccinate synthase in toluene-degrading, ferric iron-reducing Geobacter metallireducens. Biodegradation 13:149-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitts, C. L. 2001. Terminal restriction fragment patterns: a tool for comparing microbial communities and assessing community dynamics. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2:17-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krieger, C. J., H. R. Beller, M. Reinhard, and A. M. Spormann. 1999. Initial reactions in anaerobic oxidation of m-xylene by the denitrifying bacterium Azoarcus sp. strain T. J. Bacteriol. 181:6403-6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kube, M., J. Heider, J. Amann, P. Hufnagel, S. Kuhner, A. Beck, R. Reinhardt, and R. Rabus. 2004. Genes involved in the anaerobic degradation of toluene in a denitrifying bacterium, strain EbN1. Arch. Microbiol. 181:182-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerner, D. N., S. F. Thornton, M. J. Spence, S. A. Banwart, S. H. Bottrell, J. J. Higgo, H. E. H. Mallinson, R. W. Pickup, and G. M. Williams. 2000. Ineffective natural attenuation of degradable organic compounds in a phenol-contaminated aquifer. Ground Water 38:922-928. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leuthner, B., C. Leutwein, H. Schulz, P. Horth, W. Haehnel, E. Schiltz, H. Schagger, and J. Heider. 1998. Biochemical and genetic characterization of benzylsuccinate synthase from Thauera aromatica: a new glycyl radical enzyme catalysing the first step in anaerobic toluene metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 28:615-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liebich, D., M. Rosenberg, J. Schaefer, and H. Juette. 2000. Sanierung einer ehemaligen Gaskokerei in Düsseldorf. TerraTech 2:21-25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin, B., M. Braster, B. M. van Breukelen, H. W. van Verseveld, H. V. Westerhoff, and W. F. M. Röling. 2005. Geobacteraceae community composition is related to hydrochemistry and biodegradation in an iron-reducing aquifer polluted by a neighboring landfill. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5983-5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, W. T., T. L. Marsh, H. Cheng, and L. J. Forney. 1997. Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4516-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovley, D. R. 1997. Microbial Fe(III) reduction in subsurface environments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:305-313. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovley, D. R., S. J. Giovannoni, D. C. White, J. E. Champine, E. J. P. Phillips, Y. A. Gorby, and S. Goodwin. 1993. Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch. Microbiol. 159:336-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, R. Westram, L. Richter, H. Meier, Yadhukumar, A. Buchner, T. Lai, S. Steppi, G. Jobb, W. Forster, I. Brettske, S. Gerber, A. W. Ginhart, O. Gross, S. Grumann, S. Hermann, R. Jost, A. Konig, T. Liss, R. Lussmann, M. May, B. Nonhoff, B. Reichel, R. Strehlow, A. Stamatakis, N. Stuckmann, A. Vilbig, M. Lenke, T. Ludwig, A. Bode, and K.-H. Schleifer. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lueders, T., and M. W. Friedrich. 2002. Effects of amendment with ferrihydrite and gypsum on the structure and activity of methanogenic populations in rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2484-2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lueders, T., and M. W. Friedrich. 2003. Evaluation of PCR amplification bias by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of small-subunit rRNA and mcrA genes by using defined template mixtures of methanogenic pure cultures and soil DNA extracts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:320-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lueders, T., R. Kindler, A. Miltner, M. W. Friedrich, and M. Kaestner. 2006. Identification of bacterial micropredators distinctively active in a soil microbial food web. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5342-5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lueders, T., M. Manefield, and M. W. Friedrich. 2004. Enhanced sensitivity of DNA- and rRNA-based stable isotope probing by fractionation and quantitative analysis of isopycnic centrifugation gradients. Environ. Microbiol. 6:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lukow, T., P. F. Dunfield, and W. Liesack. 2000. Use of the T-RFLP technique to assess spatial and temporal changes in the bacterial community structure within an agricultural soil planted with transgenic and nontransgenic potato plants. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32:241-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGuire, J. T., D. T. Long, and D. W. Hyndman. 2005. Analysis of recharge-induced geochemical change in a contaminated aquifer. Ground Water 43:518-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meckenstock, R. U. 1999. Fermentative toluene degradation in anaerobic defined syntrophic cocultures. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 177:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mouser, P. J., D. M. Rizzo, W. F. M. Röling, and B. M. van Breukelen. 2005. A multivariate statistical approach to spatial representation of groundwater contamination using hydrochemistry and microbial community profiles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39:7551-7559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muyzer, G., A. Teske, C. O. Wirsen, and H. W. Jannasch. 1995. Phylogenetic relationships of Thiomicrospira species and their identification in deep-sea hydrothermal vent samples by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S rDNA fragments. Arch. Microbiol. 164:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osborn, A. M., E. R. B. Moore, and K. N. Timmis. 2000. An evaluation of terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis for the study of microbial community structure and dynamics. Environ. Microbiol. 2:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabus, R., M. Kube, J. Heider, A. Beck, K. Heitmann, F. Widdel, and R. Reinhardt. 2005. The genome sequence of an anaerobic aromatic-degrading denitrifying bacterium, strain EbN1. Arch. Microbiol. 183:27-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramakrishnan, B., T. Lueders, P. F. Dunfield, R. Conrad, and M. W. Friedrich. 2001. Archaeal community structures in rice soils from different geographical regions before and after initiation of methane production. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:175-186. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rappé, M. S., and S. J. Giovannoni. 2003. The uncultured microbial majority. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:369-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robertson, W. J., J. P. Bowman, P. D. Franzmann, and B. J. Mee. 2001. Desulfosporosinus meridiei sp. nov., a spore-forming sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from gasolene-contaminated groundwater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Röling, W. F., and H. W. van Verseveld. 2002. Natural attenuation: what does the subsurface have in store? Biodegradation 13:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schryver, J., C. Brandt, S. Pfiffner, A. Palumbo, A. Peacock, D. White, J. McKinley, and P. Long. 2006. Application of nonlinear analysis methods for identifying relationships between microbial community structure and groundwater geochemistry. Microb. Ecol. 51:177-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shinoda, Y., J. Akagi, Y. Uchihashi, A. Hiraishi, H. Yukawa, H. Yurimoto, Y. Sakai, and N. Kato. 2005. Anaerobic degradation of aromatic compounds by Magnetospirillum strains: isolation and degradation genes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69:1483-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith, R. L., R. W. Harvey, and D. R. LeBlanc. 1991. Importance of closely spaced vertical sampling in delineating chemical and microbiological gradients in groundwater studies. J. Contam. Hydrol. 7:285-300. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spring, S., R. Amann, W. Ludwig, K. H. Schleifer, H. van Gemerden, and N. Petersen. 1993. Dominating role of an unusual magnetotactic bacterium in the microaerobic zone of a freshwater sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2397-2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stubner, S. 2002. Enumeration of 16S rDNA of Desulfotomaculum lineage 1 in rice field soil by real-time PCR with SybrGreen detection. J. Microbiol. Methods 50:155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thies, J. E. 2007. Soil microbial community analysis using terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 71:579-591. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuxen, N., H.-J. Albrechtsen, and P. L. Bjerg. 2006. Identification of a reactive degradation zone at a landfill leachate plume fringe using high resolution sampling and incubation techniques. J. Contam. Hydrol. 85:179-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Breukelen, B. M., and J. Griffioen. 2004. Biogeochemical processes at the fringe of a landfill leachate pollution plume: potential for dissolved organic carbon, Fe(II), Mn(II), NH4, and CH4 oxidation. J. Contam. Hydrol. 73:181-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Washer, C. E., and E. A. Edwards. 2007. Identification and expression of benzylsuccinate synthase genes in a toluene-degrading methanogenic consortium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1367-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weisburg, W. G., S. M. Barns, D. A. Pelletier, and D. J. Lane. 1991. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173:697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson, R. D., S. F. Thornton, and D. M. Mackay. 2004. Challenges in monitoring the natural attenuation of spatially variable plumes. Biodegradation 15:359-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winderl, C., S. Schaefer, and T. Lueders. 2007. Detection of anaerobic toluene and hydrocarbon degraders in contaminated aquifers using benzylsuccinate synthase (bssA) genes as a functional marker. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1035-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wisotzky, F., and P. Eckert. 1997. Sulfat-dominierter BTEX-Abbau im Grundwasser eines ehemaligen Gaswerksstandortes. Grundwasser 2:11-20. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wöhlbrand, L., B. Kallerhoff, D. Lange, P. Hufnagel, J. Thiermann, R. Reinhardt, and R. Rabus. 2007. Functional proteomic view of metabolic regulation in “Aromatoleum aromaticum” strain EbN1. Proteomics 7:2222-2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]