If Mags and Fags doesn't carry a magazine that interests you, chances are you aren't interested in anything. With somewhere between 6500 and 7000 titles, on subjects ranging from miniature doll houses to elk hunting, the store offers the widest selection in the nation's capital.

The variety of magazines is matched only by the variety of ads within their pages. Every product imaginable — wrist watches, throat lozenges, spark plugs — is promoted somewhere on these shelves. For the past 10 years, however, one product has been absent from Canadian magazine ads: cigarettes. Now, much to the chagrin of anti-smoking advocates, they're back.

Last summer, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the advertising restrictions listed in the Tobacco Act, which the federal government passed in 1997. The Act states, among other things, that no person or fictional character can be used to promote a tobacco product. That spelled the end of lifestyle advertising campaigns, such as those featuring the über-rugged Marlboro Man or cartoon hipster Joe Camel.

The Canadian tobacco industry's “big 3” — Imperial Tobacco Canada Ltd., JTI-Macdonald Corp. and Rothmans, Benson and Hedges Inc. — opposed the new restrictions. During the decade-long court battle that ensued, the companies refrained from advertising in mass-market publications, arguing that the restrictions were so limiting as to essentially constitute a ban anyways.

About 5 months after the Supreme Court's June decision, however, JTI-Macdonald launched several new products with accompanying ad campaigns. The ads have appeared in entertainment magazines, such as Montréal's Mirror and Vancouver's Georgia Straight, and in the Canadian edition of Time.

The new cigarettes contain additives to improve their taste or mask the smell of their smoke. One brand, called More International, comes in whisky or liqueur d'orange flavours. Another, called Mirage, emits a vanilla aroma when smoked and is being promoted as the only cigarette in Canada with “unique Less Smoke Smell (LSS) Technology.”

Cynthia Callard, director general of Physicians For a Smoke-Free Canada, says the ads violate the Tobacco Act, which forbids promotions that are “likely to create an erroneous impression about the characteristics, health effects or health hazards of the tobacco product or its emissions.” In early December, her organization objected to the Mirage ad campaign in a written complaint to federal Health Minister Tony Clement. Health Canada is investigating the complaint.

“People will think that if there is less of a smoke smell, there is less smoke and therefore less harm,” said Callard.

JTI-Macdonald defends the Mirage ad campaign, claiming it contains no ambiguous health messages and adheres to the Tobacco Act. It also claims the ads are to promote a new brand to existing smokers, not to recruit new smokers. “In our minds, we have the right to communicate new products to smokers,” said André Benoît, vice-president of corporate affairs and communications. “The only way to do that is through advertising.”

Callard believes Mirage cigarettes will compromise non-smokers' health. When the smell is masked, people will unknowingly expose themselves to more second-hand smoke. The return of tobacco ads can only harm Canadians' health and by not issuing a comprehensive ban, the government is responsible for allowing it to happen. “I don't entirely blame the tobacco companies. It's their job to sell cigarettes.”

As 1 of 168 members of the World Health Organization's (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, Canada is obligated to ban all tobacco product advertising by 2010. But the ban must adhere to each member country's constitution and antismoking advocates say that gives Canadian tobacco companies some wiggle room, which they will be sure to take advantage of. “Nothing short of a complete ban on advertising and sponsorship is effective,” said Douglas Bettcher, director of WHO's Tobacco Free Initiative.

Bettcher says many studies have shown partial bans have no effect on reducing tobacco consumption. Restricting one form of advertising merely results in a shift to another form. Complete bans, however, can reduce smoking rates by as much as 6%, according to the World Bank Group's 1999 report “Curbing the Epidemic.” About 20 countries have such bans in place.

In addition to implementing advertising bans, Bettcher would like to see countries forbid retailers from displaying cigarettes and require them to keep tobacco products under store counters. “The package itself is the last point of promotion to the customer.”

Keeping Canadian tobacco companies out of the ad game won't be easy, says Richard Pollay, a University of British Columbia marketing professor who has followed the advertising practices of tobacco companies for 20 years. The industry is endlessly creative, he says, not only adapting to new legislation or changing public sentiment, but anticipating them: “They're playing chess when everyone else is playing checkers.” — Roger Collier, CMAJ

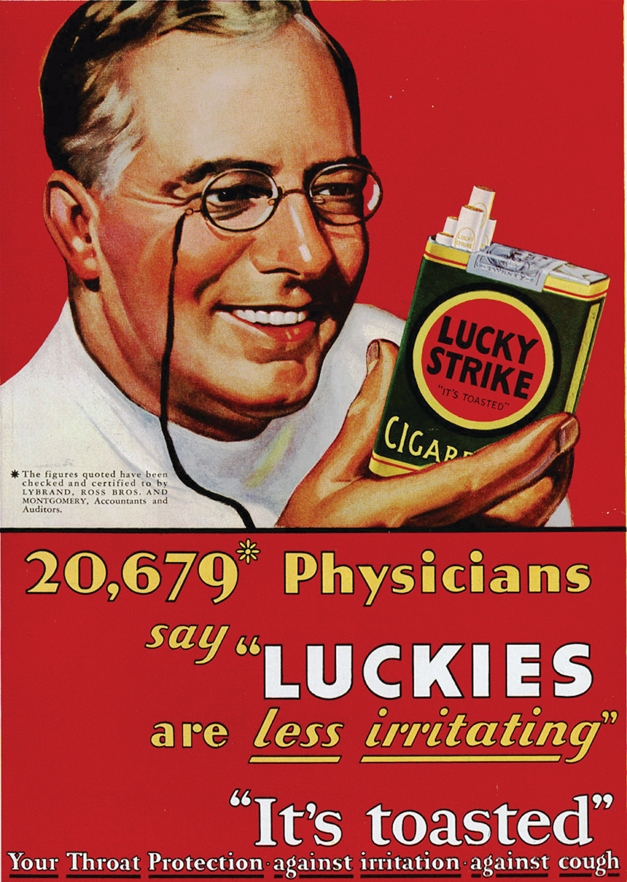

Figure. The days of the medical profession and the Marlboro Man serving as shills and icons for the tobacco industry are long gone, but tobacco advertising is back. Image by: Stanford University Lane Medical Library / tobacco.stanford.edu