For many patients, seeing a specialist quickly is tantamount to winning the lottery. Tales of seemingly endless waits for procedures such as hip replacements and cataract surgery are endemic, and often heartbreaking.

Physician shortages are the primary obstacle in reducing wait times, according to the Wait Time Alliance — a coalition of 11 physician groups working under a Canadian Medical Association (CMA) umbrella. But documenting that shortage is an enormous problem: neither major medical organizations nor many specialty groups have much in the way of hard data. Although the first step in resolving wait times is ascertaining the manpower needed to fix the problem, few specialty associations have conducted studies and fewer still have reports on hand.

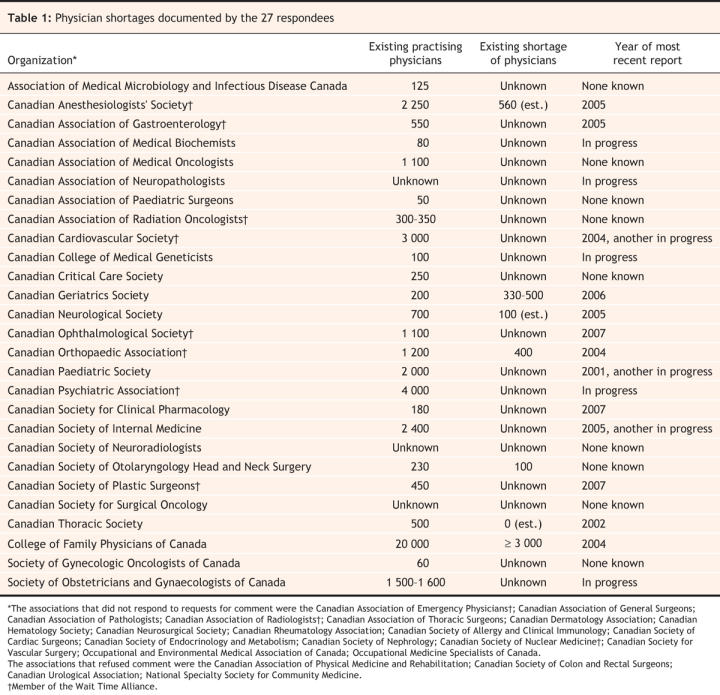

CMAJ requested human resources data from the College of Family Physicians of Canada and all 47 specialty groups registered with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons. Only 27 groups responded, a rate of 56%. All respondents reported current shortages, but only 13 had done studies over the past decade. Of the latter, only 6 could quantify their existing shortage. Eight groups are now undertaking reviews. Of the 21 groups that did not take part, 4 refused comment and 17 did not respond to repeated inquiries. But 4 have conducted studies (Table 1).

Table 1

No central agency in Canada is responsible for keeping track of specialist numbers or shortages, and no comprehensive report tracking shortfalls by discipline has ever been produced. Two organizations — the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and the CMA — have conducted research into shortages, but physician organizations take issue with their findings.

In short, nobody has much in the way of concrete evidence about how many doctors the nation needs. Many would call that astounding, let alone fundamentally essential to government determinations on how many medical school slots or residencies to fund.

Most specialty groups say responsibility for such data collection should be vested with a central health organization such as the CMA, the Royal College or the CIHR.

“The difficulty is finding up-to-date, reliable information, and that is because nobody actually has the responsibility to hold and maintain that information,” says Dr. Andrew Padmos, chief executive officer of the Royal College. “You have a lot of players at the local level, provincial governments, hospital authorities, physician groups who might be making statements. They might be accurate at a particular point at time, but they may change in the span of a reader's attention.”

With few numbers available from national agencies, the government and public ultimately have to rely on the physician specialty organizations to forecast manpower requirements, whether oncologists, psychiatrists or other specialists.

Yet reports from such organizations can be impossibly vague.

“How many emergency physicians are needed?” reads a heading in a 2002 report by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians.

The next sentence?

“Sadly, no one knows.”

The association was among organizations that declined to participate in the CMAJ canvas. Among other Wait Time Alliance nonrespondents were the Canadian Society of Nuclear Medicine and the Canadian Association of Radiologists. In fact, while a recent Alliance report fingers physician shortages as the most pressing problem that must be resolved in order to address wait times, only 8 of the 11 specialty associations who count themselves as members have conducted human resource studies. All 8 have projections of future shortages but only 2, the Canadian Anesthesiologists' Society and the Canadian Orthopaedic Association, included statistics on their current shortage, which begs the question, is it even possible to shorten wait lists without first determining how many physicians are needed to accomplish the task?

Admittedly, there are definitional and demographic difficulties in ascertaining the number of working specialists and their capacity to contribute to resolution of wait times. A doctor may practise in several different fields and be counted as a practitioner in 2 or more disciplines. Increasingly, the scope of practice of specialists is changing. As well, physicians work variable hours, depending upon age, sex, location and academic or research responsibilities.

Such factors make it difficult to get a fix on the number of specialists Canada needs, says CMA President Dr. Brian Day, a private surgical clinic owner/ operator who has long advocated the use of private clinics to claw back wait lists (CMAJ 2007;177[7]:708–9). “It's complex to gauge people who are maybe working half time or two-thirds time, or others who are dealing with a lot of chronic illness in patients.”

Getting a read on the number of family doctors required is equally problematic. A 2007 Decima poll found that 5 million Canadians lack a family doctor, says Dr. Ruth Wilson, president of the 20 000-strong College of Family Physicians of Canada, which in 2004 projected a shortfall of at least 3000 family physicians.

Startling shortfalls similarly typify the findings of the 3 specialty groups — anesthesiology, orthopedics and neurology — that have conducted human resource studies in the past decade and that have accurate numbers regarding both current and projected shortages. Yet even their reports are dated, which worries Dr. Rick Chisholm, chair of the Canadian Anathesiologists Society's physician resource committee, whose study was conducted in 2002. “Who is going to gather the data? We are all full-time clinicians. … It's all anecdotal. That's the problem.”

Small specialty associations say there's a raft of obstacles to human resources studies, particularly time and tiny membership bases, which translates into fewer dues payers and less available funding for services like research. Some societies, like the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (125 members), the Canadian Association of Paediatric Surgeons (50 members) and the Canadian Society for Clinical Pharmacology (180 members) say they're just so short-staffed they can't possibly figure out how short-staffed their disciplines are. Others, such as the Canadian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (230 members) circumvent the problem with informal straw polls.

“To do a more scientific or accurate analysis you need … time and funding,” says Dr. Satyendra Sharma, board member of the Canadian Thoracic Society. Its statistics are 7 years old. “Documenting what's fairly obvious won't get you anywhere unless the government has a backup plan to increase the number of respirologists,” adds Sharma, who chairs the Royal College's speciality committee in respirology.

Raw demographic assessments are equally suspect. According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, otolaryngology is the speciality with the highest percentage of physicians who graduated from medical school more than 35 years ago. And not only is that workforce aging, Canadian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery President Dr. Robert Rae says a 2007 survey indicates the discipline already falls 100 specialists short.

Resolving the snarl of informal surveys will require a greater commitment from governments to ensure that major health repositories keep proper statistics. At a recent Wait Times Alliance conference in Kingston, Ontario, physician groups and national statistics agencies called for centralized data collection (CMAJ 2008;178[2]:139). “In the absence of data, it is difficult to get a sense of the problem, or a solution,” Lorne Bellam, co-chair of the Alliance and president of the Canadian Ophthalmological Society, told delegates.

Delays will only make wait times worse, as a growing and aging population further strains health care resources.

According to CMA statistics, over one-third of Canada's 22 742 medical specialists (8429 physicians) and around 40% of the 8260 surgical specialists (3203 physicians) are age 55 years or older. Of the roughly 20 000 specialists and generalists who participated in the 2007 National Physician Survey (page 384), over 4000 plan to retire within the next 2 years.

The president of the second smallest organization canvassed, the 60-member Society of Gynecologic Oncologists, recently launched a 1-man campaign to document shortages in the next decade. Dr. Barry Rosen gathered numbers from Cancer Care Ontario about cancer rates in the future, factored in the number of gynecologists expected to retire soon, and determined the organization will need 30 additional people by 2016.

Among other available and specific projections is one from the 1100-strong Canadian Ophthalmological Society, which forecast last year that the ratio of doctors to the growing senior population will fall from 3 per 100 000 today to less than 2.5 in 2016.

Similarly, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society said there were 335 cardiologists in 2005 and forecast the ratio of 23.6 physicians per 100 000 Canadians would decline to 22.5 in 2021 owing to retirements. In other projections, the roughly 440 plastic surgeons practising in Canada will decrease to around 400 by 2010, and the 550 gasterenterologists practising in 2003 will fall to 500 within 10 years. Geriatrics projected in 2006 that there's now a shortage of 330–500 specialists in a discipline that only has about 200 practitioners, a disturbing notion given the aging Canadian population.

More shortfalls are in store for internal medicine, where the Canadian Society of Internal Medicine projects 60–100 new recruits will be needed each year just to maintain a current workforce of 2400. But only 20 graduate annually. Similarly, about 40% of 1683 surveyed pediatricians indicated in 2000 that they plan to retire by 2010, while a 2002 report by the Canadian Thoracic Society indicated impending retirements among its 483-strong membership would seriously threaten supply.

In some disciplines, though, the need is not as pronounced. The Canadian Neurological Society, which did respond to CMAJ inquiries, issued a 2006 report indicating that there are 198 practising neurosurgeons in Canada, a ratio of 0.63 doctors per 100 000. That falls short of the Royal College's recommended standard of 0.77 per 100 000 population, but with 15 graduates annually and just 6.5 needed to maintain existing levels, demand should be met.

That other specialty associations lack similar projections is nothing short of a disservice to Canadians. As Bellam and others like Task Force Two, the blue-ribbon panel struck to resolve means of alleviating Canada's physician shortage, have noted, numerical deficiencies and uncertainties are hardly the foundation on which to make policy decisions aimed at ensuring that “the right kind of physicians, trained to offer the right kind of care, are working in the right parts of the country at the right time,” (CMAJ 2006;174[13]:1827–8). — Elizabeth Howell, CMAJ

Figure. A computed tomography scan specialist studies his monitor and x-ray films. Although there's a widespread perception that Canada will suffer a severe shortage of specialists in many disciplines over the next decade, few attempts have been made to actually quantify national physician manpower needs. Image by: Konstantin Sutyagin / iStockphoto.com

Figure. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society forecasts that its current ratio of 23.6 physicians per 100 000 population will decline to 22.5 per 100 000 by 2021. Image by: Zsolt Nyulaszi / iStockphoto.com