Abstract

Background

Current intra-domiciliary vector control depends on the application of residual insecticides and/or repellents. Although biological control agents have been developed against aquatic mosquito stages, none are available for adults. Following successful use of an entomopathogenic fungus against tsetse flies (Diptera: Glossinidae) we investigated the potency of this fungus as a biological control agent for adult malaria and filariasis vector mosquitoes.

Methods

In the laboratory, both sexes of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto and Culex quinquefasciatus were passively contaminated with dry conidia of Metarhizium anisopliae. Pathogenicity of this fungus for An. gambiae was further tested for varying exposure times and different doses of oil-formulated conidia.

Results

Comparison of Gompertz survival curves and LT50 values for treated and untreated specimens showed that, for both species, infected mosquitoes died significantly earlier (p < 0.0001) than uninfected control groups. No differences in LT50 values were found for different exposure times (24, 48 hrs or continuous exposure) of An. gambiae to dry conidia. Exposure to oil-formulated conidia (doses ranging from 1.6 × 107 to 1.6 × 1010 conidia/m2) gave LT50 values of 9.69 ± 1.24 (lowest dose) to 5.89 ± 0.35 days (highest dose), with infection percentages ranging from 4.4–83.7%.

Conclusion

Our study marks the first to use an entomopathogenic fungus against adult Afrotropical disease vectors. Given its high pathogenicity for both adult Anopheles and Culex mosquitoes we recommend development of novel targeted indoor application methods for the control of endophagic host-seeking females.

Introduction

Malaria and bancroftian filariasis rank amongst the world's most prevalent tropical infectious diseases. An estimated 300–500 million people are infected with malaria annually, resulting in 1.5–3 million deaths [1]. Lymphatic filariasis is probably the fastest spreading insect-borne disease of man in the tropics, affecting about 146 million people [2]. The use of residual insecticides for anopheline vector control, either through indoor house spraying [3] or for bednet impregnation [4], has proven highly effective in various parts of Africa, but is not without obstacles. Emergence and spread of insecticide resistance in anophelines [1,5-7], environmental pollution [8], and unresolved issues pertaining to their toxicity to humans and non-target organisms [3,9,10] hamper progressive use and broad acceptance of these tools. Limited susceptibility and rapid build-up of resistance to synthetic pyrethroids by culicine filariasis vectors [11], combined with the availability of effective anti-filarial drugs [12], is causing a gradual shift from vector control to mass-chemotherapy, though resurgence of transmission in the absence of vector control remains problematic [13,14]. A continued search for appropriate vector control strategies to augment this limited arsenal of tools is called for [15], and includes biological control methods [16,17].

Many biological control agents have been evaluated against larval stages of mosquitoes, of which the most successful ones comprise bacteria such as Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis and B. sphaericus [18,19], mermithid nematodes such as Romanomermis culicivorax [20], microsporidia such as Nosema algerae [21], and several entomopathogenic fungi [17]. Among these fungi, the oomycete Lagenidium giganteum has proven successful for vector control in rice fields [22] and is currently produced commercially [23]. Other mosquito-pathogenic fungi that target larval instars include the chytidriomycetes Coelomomyces [24,61], and the deuteromycetes Culicinomyces [25,62], Beauveria [26] and Metarhizium [27]. Of the few fungi known to infect adult Diptera, the majority belong to the group of Zygomycetes (Entomophthoraleans) [28-30,63]. Unfortunately, problems associated with growing Entomophthoraleans in vitro have proven a major obstacle for these fungi to be used for biological control [30].

Only a handful of studies have evaluated biological control agents/methodologies to control adult stages of tropical disease vectors. Soarés [31] infected adult Ochlerotatus sierrensis with the deuteromycete Tolypocladium cylindrosporum, resulting in 100% mortality after 10 days, whereas Clark et al. [26] showed in a laboratory study that adult mosquitoes of Culex tarsalis, Cx. pipiens, Aedes aegypti, Ochlerotatus sierrensis, Ochlerotatus nigromaculis, and Anopheles albimanus were susceptible to Beauveria bassiana. Recently, Scholte et al. [32] reported that adult An. gambiae is susceptible to B. bassiana, a Fusarium spp., and Metarhizium anisopliae.

M. anisopliae is a soil-borne metropolitan fungus and infects predominantly soil-dwelling insects [33,34]. It has a large host-range, including arachnids and five orders of insects [35], comprising over 200 species. Although mosquitoes are not listed as natural hosts for M. anisopliae [27,33] some strains have shown to be virulent against mosquito larvae [27,36-40].

Spores (conidia) of M. anisopliae have been known for some time to be infectious to adults and emerging pupae of tsetse flies (Diptera: Glossinidae) [41,42] and novel devices for exposing wild-caught specimens have been developed [43]. Following our initial observation that the same fungus is pathogenic to An. gambiae [32], we report here on the effects of different exposure times to conidia-treated substrates (24, 48 hrs or continuous exposure), and dose-response experiments using oil-formulations of conidia. In addition, we report the effects of continuous exposure to conidia of adult Cx. quinquefasciatus.

Materials and Methods

Bioassays

Three different bioassays were conducted to study the effect of:

1) dry conidia of M. anisopliae on infection and survival of adult male and female An. gambiae s.s. and Cx. quinquefasciatus. In this bioassay exposure of mosquitoes to conidia was continuous throughout the experimental period;

2) limited exposure (24 or 48 hrs only) to dry conidia on infection and survival of male and female An. gambiae s.s.. Following these periods the source of conidia was removed to avoid further exposure;

3) different doses of conidia, formulated in sunflower oil on infection and survival of female An. gambiae s.s..

Mosquitoes

Anopheles gambiae s.s. mosquitoes for bioassays 1 and 2 were obtained from a colony that originates from specimens collected in Njage village in 1996, 70 km from Ifakara town, in south-east Tanzania. All maintenance and rearing procedures have been described in detail elsewhere [44,45]. An. gambiae s.s. mosquitoes for bioassay 3 originated from Suakoko, Liberia (courtesy Prof. M. Coluzzi). Rearing procedures for this strain were recently described by Mukabana et al. [46]. Climatic conditions were 18–30°C and 40–90% RH (bioassay 1), 28 ± 2° C and 70 ± 5% RH (bioassay 2) and 27 ± 1°C and 80 ± 5% RH (bioassay 3).

Bloodfed Cx. quinquefasciatus were collected daily from local houses in Mbita Point, western Kenya. For bioassays, only the F1 offspring from these wild mosquitoes was used. Larvae and adult mosquitoes were kept under similar conditions as the An. gambiae s.s. used in bioassay 1.

Fungus

Metarhizium anisopliae var. anisopliae (Metsch.) Sorokin, isolate ICIPE-30 (courtesy Dr. N. Maniania) was used for all three bioassays. The fungus was originally isolated in 1989 from a stemborer, Busseola fusca Fuller, near Kendu Bay, western Kenya. Prior to use, fresh conidia were stored in the dark at 4°C.

Experimental procedures

Bioassay 1

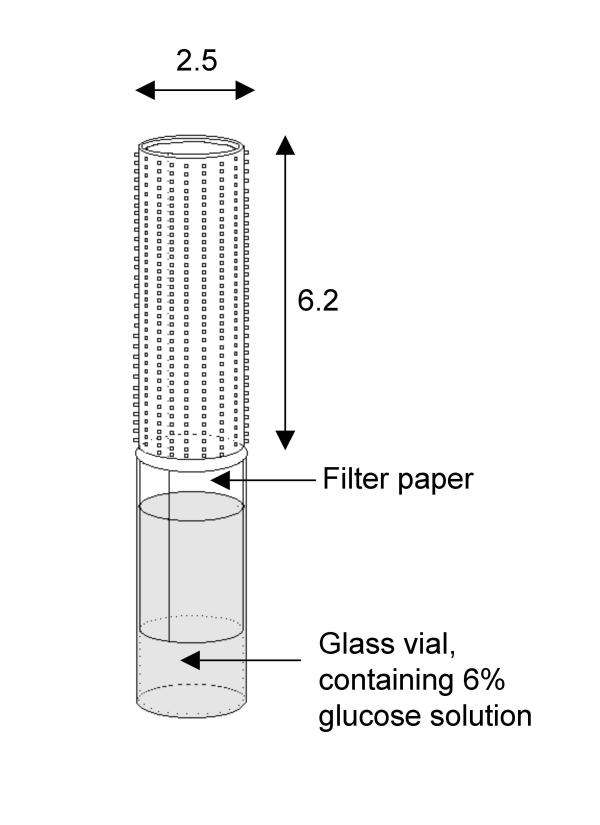

For each of three replicates, 30–50 male and female An. gambiae s.s. or Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes, aged 1–2 days at the start of the experiment, were placed in a 30 cm cubic iron-framed cage covered with white mosquito netting. These mosquitoes were offered a 6% glucose solution absorbed onto white laboratory filter-paper placed in a glass vial (Figure 1). The paper was enveloped by a locally available hair-roller ('suspensor'), basically a polyethylene perforated tube (height 6.2 cm, diameter 2.5 cm) with protruding, short plastic hairs that enlarged its surface area. This suspensor was dusted with 100 mg of dry conidia using a small paintbrush and carefully placed over the filter-paper. Mosquitoes landing on the suspensor to consume glucose would thus be exposed to conidia through tarsal contact or on the head and thorax region when feeding through the holes in the suspensor. The suspensor remained in the cage until the end of the bioassay (a minimum of 8 days), resulting in continuous exposure of mosquitoes to the conidia whenever they consumed glucose. The control group was exposed to a similar suspensor, but without conidia. An estimation of conidia density was made using a haemocyte counter (Fuchsrosenthal®, 0.2 mm depth), showing that 100 mg of conidia equalled approximately 6 × 108 conidia. Dead mosquitoes were removed from the cage daily, placed on moist filter-paper (distilled water) in a parafilm-sealed petri dish, and examined for fungal growth after a few days.

Figure 1.

The set-up used to contaminate mosquitoes with dry conidia of Metarhizium anisopliae. Dimensions are in cm.

Bioassay 2

Experimental procedures were identical to those described above, except that the source of conidia was removed from the cages after either 24 or 48 hrs and replaced with a non-contaminated source of glucose.

Bioassay 3

Conidia were inoculated on oatmeal agar and placed in an incubator to grow for 2 weeks, after which fresh conidia were harvested using a 0.05% Triton-x solution and a glass rod. The solvent containing conidia was concentrated by removing the supernatant after centrifuging for 3 min at 5000 rpm. Dilutions were made using 0.05% Tween 20 to obtain conidia concentrations of 105, 106, 107, and 108 conidia/ml. Sunflower oil was added to these solvents to obtain 10% oil-formulations for all solvents. For the bioassay, 1 ml of the various oil-formulations was pipetted evenly over a 8 × 6 cm piece of filter-paper and left to dry at 70% RH for 48 hrs, resulting in spore densities of 1.6 × 107-1.6 × 1010 conidia/m2. These papers were gently placed in cylindrical glass vials so that the paper coated the inside of the vial. Mosquitoes were tested individually by placing a 1 to 3 day-old female An. gambiae s.s. in a vial, which was then sealed with cotton netting material. For each dose, 10–15 mosquitoes were tested each time, and all of the above procedures replicated thrice. Mosquitoes had access to a 6% glucose solution by placing freshly soaked cotton wool pads on the netting daily. The filter-paper was removed from the vial after three days, essentially delivering tarsal exposure of mosquitoes to conidia for 72 hrs. Dead mosquitoes were removed from the vials daily and placed in petri dishes containing moist filter-paper. These were then sealed off and placed in an incubator at 27°C for three days, after which the cadavers were checked for sporulating M. anisopliae using a dissection microscope.

Data analysis

Survival curves were analysed by Kaplan-Meier pair-wise comparison [47] and Cox regression analysis (using SPSS 11.0 and Genstat 5 software). For each trial, mosquito survival data were fitted to the Gompertz distribution model [48] (using Genstat 5) as described by Clements and Paterson [49], from which LT50 values were calculated. LT50 values of treated versus control groups were compared using paired sample t-tests.

Results

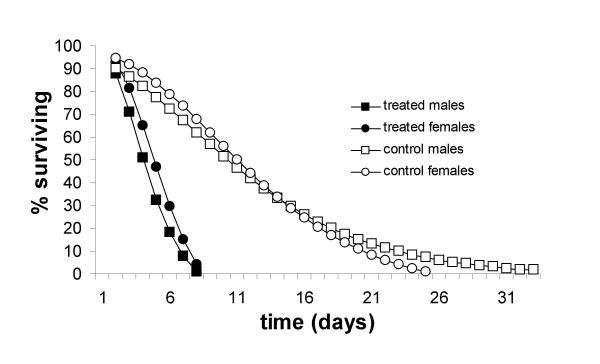

M. anisopliae showed to be pathogenic to adult male and female An. gambiae s.s., both when mosquitoes were exposed to oil-formulated or dry conidia. Cox regression analysis showed that this pathogenicity was not dependant on exposure time. Mosquitoes exposed to conidia for 24 or 48 hrs or continuously, died significantly faster (p < 0.001) than the untreated groups (Table 1). No significant differences in survival were found between groups exposed for either 24 or 48 hrs (p = 0.861), but there appeared to be a trend that survival was lower under continuous exposure, compared to 24 or 48 hrs, although this difference was also not significant (p = 0.092). Overall, males died faster than females (p = 0.020). Following continuous exposure, 100% mortality of both male and female An. gambiae was observed by day 7, at which time an average of 41.7 and 82.3% of the respective sexes in the control treatment were still alive.

Table 1.

LT50 ± SE values for adult An. gambiae s.s. and Cx. quinquefasciatus exposed to dry conidia of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae for variable periods of time.

| Species | Exposure time | Sex | LT50 ± SE1 | p-value2 | |

| Control | Treated | ||||

| An. gambiae s.s. | continuous | female | 11.00 ± 0.58 | 5.08 ± 1.61 | 0.030 |

| continuous | male | 7.65 ± 1.60 | 3.75 ± 0.29 | 0.042 | |

| 48 hrs | female | 10.31 ± 1.30 | 3.80 ± 0.25 | 0.076 | |

| 48 hrs | male | 11.66 ± 4.28 | 3.15 ± 0.37 | 0.125 | |

| 24 hrs | female | 8.87 ± 1.32 | 3.39 ± 0.28 | 0.010 | |

| 24 hrs | male | 11.68 ± 1.16 | 3.29 ± 0.59 | 0.048 | |

| Cx. quinquefasciatus | continuous | female | 13.33 ± 2.91 | 3.88 ± 0.19 | 0.010 |

| continuous | male | 18.00 ± 1.00 | 3.24 ± 0.23 | 0.010 | |

1 standard error; 2 paired t-test

In all bioassays where mosquitoes were exposed to dry conidia, fungal sporulation was observed in > 95% of the cadavers. For conidia in oil-formulations, percentage sporulation was positively correlated with conidial dose. Percentages ranged from 4.43 ± 4.4 % for mosquitoes that had been exposed to the lowest, to 83.70 ± 8.3 % for those that had been exposed to the highest dose (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pair-wise Kaplan-Meier survival curve and LT50 comparison for adult Anopheles gambiae s.s. exposed to four different doses of sunflower oil-formulated Metarhizium anisopliae.

| Dose1 | Survival curves2 | LT50 ± SE3 | LT50-grouping2 | % Infected |

| Control | a | 9.86 ± 1.16 | a | N/a |

| 105 | ab | 9.37 ± 1.26 | a | 4.43 ± 4.4 |

| 106 | bc | 6.85 ± 0.44 | b | 32.63 ± 5.4 |

| 107 | c | 6.65 ± 0.43 | b | 59.74 ± 5.6 |

| 108 | d | 5.85 ± 0.26 | b | 83.70 ± 8.3 |

1 conidia per ml of 10% oil-formulation ; 2 treatments without letters in common are significantly different at P < 0.05; 3 standard error. N/a: not applicable.

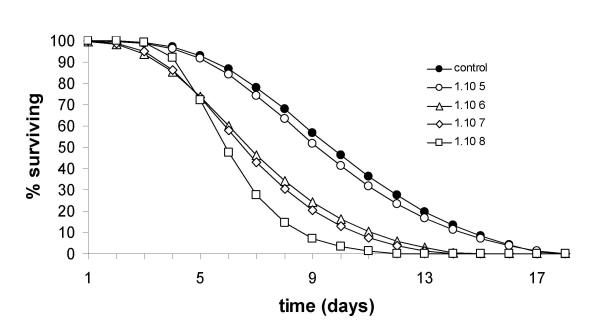

Mosquito survival data from all three bioassays closely fitted the Gompertz distribution model (variance accounted for ranged from 96.2–99.6%; Figure 2 and 3). Estimates of daily survival rates derived from the Gompertz model [49] showed a dramatic reduction following exposure to conidia. In the dose-response experiment, daily survival rates were inversely related to the exposure dose. Table 3 shows estimated daily survival rates for An. gambiae at different ages for the doses tested.

Figure 2.

Gompertz survival curves for adult male and female Anopheles gambiae s.s. infected with dry conidia of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae (pooled data for 24/48 hrs or continuous exposure).

Figure 3.

Gompertz survival curves for adult female Anopheles gambiae s.s. infected with different doses of oil-formulated conidia of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae (bioassay 3, for details see text).

Table 3.

Estimated daily survival rates (± standard error), derived from the Gompertz model [see [49]], for female Anopheles gambiae s.s., following exposure to varying doses of oil-formulated conidia of Metarhizium anisopliae.

| Days after exposure1 | Dose (conidia/ml) | ||||

| 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | Control | |

| 3 | 0.98 (0.012) | 0.93 (0.021) | 0.92 (0.028) | 0.93 (0.046) | 0.97 (0.017) |

| 7 | 0.83 (0.076) | 0.73 (0.069) | 0.69 (0.030) | 0.51 (0.026) | 0.87 (0.052) |

| 10 | 0.80 (0.024) | 0.77 (0.024) | 0.37 (0.239) | 0.22 (0.208) | 0.81 (0.047) |

1 Mosquitoes were 1–2 days old at the start of the experiment (day 0).

Pair-wise comparisons of Kaplan-Meier data and survival-curves for the different doses of exposure (Table 2, Figure 3) showed that mosquito survival in the untreated group was not significantly different from that observed for mosquitoes exposed to the lowest dose (1.6 × 107 conidia/m2) (p= 0.448). Survival of mosquitoes exposed to the two intermediate doses (1.6 × 108 and 1.6 × 109 conidia/m2) was significantly different from the lowest (1.6 × 107conidia/m2) (p = 0.014 and p < 0.001), as well as the highest (1.6 × 1010 conidia/m2) dose, (p = 0.001 and p = 0.014). LSD multiple comparison analysis of the LT50 values showed similar, but not equal cluster formation: the five groups appeared to be divided into two clusters (Table 2). One cluster contained the untreated group and the dose 1.6 × 107 conidia/m2. Within this cluster the LT50 values were not significantly different from each other (p = 0.668), but they were both significantly different from the three other doses (p-values ranging between 0.003 and 0.040). Within this other cluster the LT50's did not differ significantly from each other (p-values ranging between 0.261 and 0.880).

As for An. gambiae, male Cx. quinquefasciatus died faster than females (p < 0.001). Under continuous exposure, 100% mortality was reached at day 6 for males and at day 7 for females, at which time 85.3% and 90.0% of the respective sexes in the control treatments were still alive. Highly significant reductions in both male and female survival were observed (Table 1).

Discussion

Epidemiological models on malaria and filariasis show that adult mosquito survival is the most sensitive component of vectorial capacity [50-52]. Notable reductions in the life-span of female An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus will therefore have a considerable impact on reducing the transmission risk of malaria and lymphatic filariasis. For An. gambiae, daily survival rates (p) have been calculated for field populations, either from mark-release-recapture studies or physiological state ratios of wild-caught females. Takken et al. [53], using mark-release-recapture methodology near Ifakara, southeast Tanzania, estimated p to be 0.78. Gillies [54], using physiological state methodology in the coastal lowlands of Tanzania, found that female mortality rate was almost constant during the 1-parous to 6-parous age period, with p being 0.85, but that it increased sharply thereafter. Killeen et al. [55] arrived at a mean p value of 0.90, reflecting an approximate median of estimates for four holoendemic sites in Africa, which equals our estimates from the Gompertz model.

The results from the current study show that the daily survival rates of M. anisopliae-infected adult mosquitoes at any given moment in the mosquito's life span, is lower than non-infected mosquitoes, and that their life span is reduced, provided that the conidial dose is high enough.

If this is translated from a laboratory situation to the field it could result (under favourable circumstances) in reduced vectorial capacities of these mosquitoes. For Cx. quinquefasciatus, life-expectancies of 30.82 ± 3.41 and 44.12 ± 4.19 days were found for caged male and females in Tanzania [56]. Oda et al. [57] found mean longevities of 39.8 (males) and 64.4 days (females), when kept in the laboratory at 25°C. In our study we recorded lower survival of uninfected specimens, but when 100% of the treated female Cx. quinquefasciatus had died, 90 ± 6 % of the untreated specimens were still alive, demonstrating that this species is highly susceptible to infection with M. anisopliae.

The correlation of increasing proportion of sporulation with exposure of An. gambiae to increasing conidial doses suggests that the mosquitoes' immune system is only able to defend against the fungal infection at low doses, diminishing effectiveness when exposed to increasing conidial doses. Mosquitoes may overcome a low infection level by melanization and/or encapsulation of blastospores [58]. These defences would however have a cost to the mosquito's fitness [59,60], which is a possible explanation for the positive correlation between conidial dose, mortality rate and proportion of sporulation found in bioassay 3. Unfortunately, in the present study we did not examine mosquitoes for melanization.

For successful conidial attachment, fungal penetration and, in the end, killing of a mosquito, a threshold number of condia per unit surface area is required. In our dose-response experiments the lowest dose resulting in a significant effect on mosquito survival was 1.6 × 108 conidia/m2, equaling 160 conidia/mm2. Apart from the two claws at the end of the last tarsus, the legs/tarsae of mosquitoes are densely covered with hair-like structures ('feathers'), which make it difficult for conidia to attach to the cuticula of the tarsus. This was confirmed by observations under a light microscope at magnification 40×. Several mosquitoes were gently removed from the contamination cage, placed into a glass vial (they had been exposed for 24 hrs to 1 × 106 conidia/ml of oil-formulated conidia on impregnated filter-paper) and killed by adding a small droplet of chloroform in the vial. Many conidia were found attached to the 'feathers' of the last few tarsae, and several at the 'feathers'of the tibia, but only few were actually attached to the cuticle. The ones that appeared to be attached to the cuticle, were located near the end of the last tarsus, around the claws, and in the intersegmental areas of the tarsae, where very few 'feathers' are present. Apparently the effective conidial dose (i.e. conidia that actually attach to the mosquito's cuticle and subsequently invade the integument and haemocoel) is an unknown, but presumably it is a rather low fraction of the conidial dosage that attaches to the mosquito. There appeared to be considerable differences in LT50 values between An. gambiae exposed to dry or to oil-formulated conidia. The dose of dry conidia that was used was estimated to be 6 × 108 conidia per suspensor. The suspensor has a surface area 48.7 cm2, but has a 'hairy' surface area, containing approximately 40 plastic 'hairs' (height 3.5 mm, diameter 0.5 mm) per cm2 suspensor surface, which increases its surface area with an estimated 107 cm2 to 155.7 cm2, resulting in a conidial dose per surface area of approximately 5.6 × 1010 conidia/m2. This is 3.5 times higher than the highest oil-formulated dose used in bioassay 3 (1.6 × 1010 conidia/m2).

When comparing the effects of indoor application of residual insecticides, or bednets treated with synthetic pyrethroids, on mosquito mortality, M. anisopliae delivers lower overall mortality rates and speed of killing target insects. However, apart from its demonstrated pathogenicity to An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus, M. anisopliae exhibits several characteristics that make it an attractive agent for biocontrol of adult mosquitoes in sub-Saharan Africa. It can be mass-produced easily and cheaply [23] and has a considerable shelf-life if stored under proper conditions. The fungus is not harmful to either birds, fish, or mammals [34] and since the fungus is one of the most common entomopathogenic fungi, with a worldwide distribution, its use for biocontrol would not mean the introduction of a non-endemic organism into the African ecosystem.

Conclusions

The experiments clearly showed that the malaria vector An. gambiae s.s., and the filariasis vector Cx quinquefasciatus are susceptible to M. anisopliae. Their lifespan is greatly reduced if contaminated with an appropriate dose of conidia. As mosquito longevity is the single-most important parameter in the vectorial capacity equation, prospects for developing this adult mosquito control strategy are promising and may in due course be developed into an adult mosquito control tool. Questions regarding application methodology, with the aim to optimize exposure of vector mosquitoes to sources of fungal spores/conidia, are currently being addressed.

Authors contributions

E-JS, BNN and RCS were directly involved in the experimental work, analysis of the data and drafting of the manuscript. BGJK conceived of the study, obtained funding for it in collaboration with WT and revised the manuscript prior to submission.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Milcah Gitau, Bernard Odhiambo, Leo Koopman, André Gidding and Frans van Aggelen for technical assistance. This study was supported by the Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO), grant number W83-174.

Contributor Information

Ernst-Jan Scholte, Email: ErnstJan.Scholte@wur.nl.

Basilio N Njiru, Email: bnjiru@mbita.mimcom.net.

Renate C Smallegange, Email: Renate.Smallegange@wur.nl.

Willem Takken, Email: Willem.Takken@wur.nl.

Bart GJ Knols, Email: B.Knols@iaea.org.

References

- WHO WHO expert committee on malaria, WHO Technical Report Series 892. Geneva, Switzerland. 2000. [PubMed]

- WHO Lymphatic filariasis: The disease and its control. 5th report: WHO Expert Committee on Filariasis. Technical Report Series 821. Geneva, Switserland. 1992. [PubMed]

- Curtis CF. Should the use of DDT be revived for malaria vector control? Biomédica. 2002;22:455–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated bednets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Library Reports. 1998;3:1–70. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandre F, Darrier F, Manga L, Akogbeto M, Faye O, Mouchet J, Guillet P. Status of pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae sensu lato. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:230–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Koekemoer LL, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Mthembu J, Coetzee M. Anopheles funestus resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:181–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaim M, Guillet P. Alternative insecticides: An urgent need. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:161–163. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(01)02220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariee F, Ernst WHO, Sijm DTHM. Natural and synthetic organic compounds in the environment-a Symposium report. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2001;10:65–80. doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(01)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Wildlife Fund Hazards and exposures associated with DDT and synthetic pyrethroids used for vector control. WWF, Toronto, Canada. 1999.

- Turusov V, Rakitsky V, Tomatis L. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT): ubiquity, persistence, and risks. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:125–128. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandre F, Darriet F, Darder M, Cuany A, Doannio JM, Pasteur N, Guillet P. Pyrethroid resistance in Culex quinquefasciatus from west Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 1998;12:359–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1998.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiah KD, Vanamail P, Pani SP, Yuvaraj J, Das PK. The effect of six rounds of single dose mass treatment with diethylcarbamazine or ivermectin on Wuchereria bancrofti infection and its implications for lymphatic filariasis elimination. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:767–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkot T, Ichimori K. The PacELF programme: will mass drug administration be enough? Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:109–115. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(01)02221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunish IP, Rajendran R, Mani TR, Munirathinam A, Tewari SC, Hiriyan J, Gajanana A, Satyanarayana K. Resurgence in filarial transmission after withdrawal of mass drug administration and the relationship between antigenaemia and microfilaraemia – a longitudinal study. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:59–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiff C. Integrated approach to malaria control. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:278–298. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.278-293.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey LA, Undeen AH. Microbial control of black flies and mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1986;25:265–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.31.010186.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federici BA. The future of microbial insecticides as vector control agents. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1995;11:260–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker N, Margalit J. Use of Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis against mosquitoes and blackflies. In: Entwistle PF, Cory JS, Bailey MJ, Higgs S, editor. Bacillus thuringiensis, an environmental pesticide: theory and practice. Wiley & Sons, Chichester; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Fillinger U, Knols BGJ, Becker N. Efficacy and efficiency of new Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis and B. sphaericus formulations against the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae in Western Kenya. Trop Med Intl Health. 2003;8:37–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaim M, Ladonni H, Ershadi MRY, Manouchehri AV, Sahabi Z, Nazari M, Shahmohammadi H. Field application of Romanomermis culicivorax (Mermithidae: Nematoda) to control anopheline larvae in southern Iran. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1988;4:351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undeen AH, Dame DA. Measurement of the effect of microsporidian pathogens on mosquito larval mortality under artificial field conditions. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1987;3:91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmon CF, Schreiber ET, Vo T, Bloomquist MA. Field trials of three concentrations of Laginex TM as a biological larvicide compared to VectobacTM-12AS as a biocontrol agent for Culex quinquefasciatus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2000;16:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetan SK. Microbial Pest Control. Marcel Dekker, New York. 2001.

- Shoulkamy MA, Lucarotti CJ. Pathology of Coelomomyces stegomyiae in larval Aedes aegypti. Mycologia. 1998;90:559–564. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney AW. Preliminary field tests of the fungus Culicinomyces against mosquito larvae in Australia. Mosq News. 1981;41:470–476. [Google Scholar]

- Clark TB, Kellen W, Fukuda T, Lindgren JE. Field and laboratory studies on the pathogenicity of the fungus Beauvaria bassiana to three genera of mosquitoes. J Invertebr Path. 1968;11:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(68)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DW. Coelomomyces, Entomophtora, Beauvaria, and Metarrhizium as parasites of mosquitoes. Misc Publ Entom Soc Am. 1970;7:140–155. [Google Scholar]

- Low RE, Kennel EW. Pathogenicity of the fungus Entomophthora coronata in Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus and Aedes taeniorhynchus. Mosq News. 1972;32:614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JP. Entomophthora culicis (Zygomycetes, Entomophthorales) as a pathogen of adult Aedes aegypti (Diptera, Culicidae) Aquat Insects. 1982;4:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Eilenberg J, Damgaard PH, Hansen BM, Pedersen JC, Bresciani J, Larsson R. Natural coprevalence of Strongwellsea castrans, Cystosporogenes deliaradicae, and Bacillus thuringiensis in the host, Delia radicum. J Invertebr Pathol. 2000;75:69–75. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1999.4892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soarés GG., Jr Pathogenesis of infection by the hyphomycetous fungus Tolyplcladium cylindrosporum in Aedes sierrensis and Culex tarsalis (Dipt.: Culicidae) Entomophaga. 1982;27:283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Scholte E-J, Takken W, Knols BGJ. Pathogenicity of six East African entomopathogenic fungi to adult Anopheles gambiae s.s. (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes. Proc Exp Appl Entomol NEV, Amsterdam. 2003;14:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Veen KH. Recherches sur la maladie, due a Metharhizium anisopliae chez le criquet pèlerin. PhD-thesis, Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen 68–5. 1968.

- Zimmermann G. The entomopathogenic fungus Metahizium anisopliae and its potential as a biocontrol agent. Pestic Sci. 1993;37:375–379. [Google Scholar]

- Boucias DR, Pendland JC. Entomopathogenic fungi; Fungi Imperfecti. In: Boucias DR, Pendland JC, editor. Principles of Insect Pathology. Vol. 10. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DW. Some effects of Metarhizium anisopliae and its toxins on mosquito larvae. In: Van der Laan, editor. Insect Pathology & Microbial Control. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: North-Holland Publishing Company; 1967. pp. 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DW. Fungal infections of mosquitoes. In: Aubin A, Belloncik S, Bourassa JP, LaCoursière E, Péllissier M, editor. Le contrôle des moustiques/Mosquito control. La Presse de l'Université du Quebec, Canada; 1974. pp. 143–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ramoska WA. An examination of the long-term epizootic potential of various artificially introduced mosquito larval pathogens. Mosq News. 1982;42:603–607. [Google Scholar]

- Daoust RA, Roberts DW. Studies on the prolonged storage of Metarhizium anisopliae conidia: effect of temperature and relative humidity on conidial viability and virulence against mosquitoes. J Invertebr Path. 1983;41:143–150. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(83)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravallec M, Riba G, Vey A. Sensibilité d' Aedes albopictus (Dipt.: Culicidae) à l'hyhomycète entomopathogène Metarhizium anisopliae. Entomophaga. 1989;34:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kaaya GP. Glossina morsitans morsitans : mortalities caused in adults by experimental infection with entomopathogenic fungi. Acta Trop. 1989;46:107–114. doi: 10.1016/0001-706X(89)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaya GP, Munyinyi DM. Biocontrol potential of the entomogenous fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae for tsetse flies (Glossina spp.) at developmental sites. J Invertebr Pathol. 1995;66:237–241. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1995.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniania NK. A device for infecting adult tsetse flies, Glossina spp., with an entomopathogenic fungus in the field. Biol Control. 1998;11:248–254. doi: 10.1006/bcon.1997.0580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathenge EM, Killeen GF, Oulo DO, Irungu LW, Ndegwa PN, Knols BGJ. Development of an exposure-free bednet trap for sampling Afrotropical malaria vectors. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16:67–74. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-283x.2002.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knols BGJ, Njiru BN, Mathenge EM, Mukabana WR, Beier JC, Killeen GF. MalariaSphere: A greenhouse-enclosed simulation of a natural Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) ecosystem in western Kenya. Malaria J. 2002;1:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukabana WR, Takken W, Seda P, Killeen GF, Hawley WA, Knols BGJ. Extent of digestion affects the success of amplifying human DNA from blood meals of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) Bull Ent Res. 2002;92:233–239. doi: 10.1079/BER2002164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BS. Statistical methods for medical investigations. New York: Halsted Press. 1994.

- Gompertz B. On the nature of the function expressive of the law of human mortality, and on a new mode of determining the value of life continguencies. Phil Trans R Soc. 1825. pp. 513–585.

- Clements AN, Paterson GD. The analysis of mortality and survival rates in wild populations of mosquitoes. J Appl Ecol. 1981;18:373–399. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DR, Weidhaas DE, Hall RC. Parameter sensitivity in insect population modeling. J Theor Biol. 1973;42:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(73)90089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald G. The epidemiology and control of malaria. London: Oxford University Press. 1957.

- Garrett-Jones C. Prognosis for interruption of malaria transmission through assessment of the mosquito's vectorial capacity. Nature. 1964;204:1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/2041173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takken W, Charlwood JD, Billingsley PF, Gort G. Dispersal and survival of Anopheles funestus and A. gambiae s.l. (Diptera: Culicidae) during the rainy season in southeast Tanzania. Bull EntRes. 1998;88:561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Gillies MT. Studies on the dispersion and survival of Anopheles gambiae Giles in East Africa, by means and release experiments. Bull Ent Res. 1961;52:99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Killeen GF, McKenzie FE, Foy BD, Schieffelin C, Billingsley PF, Beier JC. A simplified model for predicting malaria entomologic inoculation rates based on entomologic and parasitologic parameters relevant to control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:535–544. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasule FK. A comparison of the life history components of Aedes aegypti (L.) and Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) Insect Sc Applic. 1986;7:143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Eshita Y, Uchida K, Mine M, Kurokawa K, Ogawa Y, Kato K, Tahara H. Reproductive activity and survival of Culex pipiens pallens and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Japan at high temperature. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:185–190. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak JPN. Insect Immunity. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1993.

- Schwartz A, Koella JC. Melanization of Plasmodium falciparum and C-25 sephadex beads by field-caught Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) from southern Tanzania. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:84–88. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd H. Manipulation of medically important insect vectors by their parasites. Annu Rev Entomol. 2003;48:141–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucarotti CJ. Invasion of Aedes aegypti ovaries by Coelomomyces stegomyiae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1992;60:176–184. doi: 10.1006/jipa.2000.4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debenham ML, Russell RC. The insect pathogenic fungus Culicinomyces in adults of the mosquito Anopheles amictus hilli. J Austr Entomol Soc. 1977;16:46. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JP. Pathogenicity of the fungus Entomophthora culicis for adult mosquitoes: Anopheles stephensi and Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus. J NY Entomol Soc. 1983;91:177–182. [Google Scholar]