Abstract

KATP channels were reconstituted in COSm6 cells by coexpression of the sulfonylurea receptor SUR1 and the inward rectifier potassium channel Kir6.2. The role of the two nucleotide binding folds of SUR1 in regulation of KATP channel activity by nucleotides and diazoxide was investigated. Mutations in the linker region and the Walker B motif (Walker, J.E., M.J. Saraste, M.J. Runswick, and N.J. Gay. 1982. EMBO [Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.] J. 1:945–951) of the second nucleotide binding fold, including G1479D, G1479R, G1485D, G1485R, Q1486H, and D1506A, all abolished stimulation by MgADP and diazoxide, with the exception of G1479R, which showed a small stimulatory response to diazoxide. Analogous mutations in the first nucleotide binding fold, including G827D, G827R, and Q834H, were still stimulated by diazoxide and MgADP, but with altered kinetics compared with the wild-type channel. None of the mutations altered the sensitivity of the channel to inhibition by ATP4−. We propose a model in which SUR1 sensitizes the KATP channel to ATP inhibition, and nucleotide hydrolysis at the nucleotide binding folds blocks this effect. MgADP and diazoxide are proposed to stabilize this desensitized state of the channel, and mutations at the nucleotide binding folds alter the response of channels to MgADP and diazoxide by altering nucleotide hydrolysis rates or the coupling of hydrolysis to channel activation.

Keywords: diazoxide, adenosine triphosphate, adenosine diphosphate, sulfonylurea receptor, Kir6.2

introduction

KATP channels are ligand-gated potassium channels that couple membrane excitability to the metabolic state of the cell. They are present in a wide variety of tissues, including pancreatic β cells, heart, skeletal muscle, smooth muscle, and brain (Ashcroft, 1988). In the pancreas, the KATP channel serves as a sensor of blood glucose concentration to regulate insulin secretion. KATP channels have a complex regulation by intracellular nucleotides (Ashcroft, 1988; Nichols and Lederer, 1991; Terzic et al., 1994, 1995). The inhibitory effect of ATP appears to be a result of direct binding of the nucleotide and does not require ATP hydrolysis since it does not require Mg2+ and can be mimicked by nonhydrolyzable ATP analogues, AMP, and ADP in the absence of Mg2+. In the presence of Mg2+, however, ADP antagonizes channel inhibition by ATP (Dunne and Petersen, 1986; Kakei et al., 1986; Misler et al., 1986; Findlay, 1988; Lederer and Nichols, 1989), and this action is probably important in stimulating channel activity at physiological concentrations of ATP (Nichols et al., 1996). In addition to regulation by intracellular nucleotides, the KATP channel is modulated by a variety of pharmacological agents. Sulfonylureas such as tolbutamide and glibenclamide inhibit KATP channel activity in pancreatic β cells and are clinically effective in the treatment of non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (Sturgess et al., 1985). A chemically diverse group of potassium channel openers, including diazoxide, nicorandil, minoxidil, pinacidil, and cromakalim (Robertson and Steinberg, 1990) stimulate KATP channel activity, with tissue specificity. For instance, diazoxide opens pancreatic β cell KATP channels but does not activate cardiac KATP channels. Pinacidil and cromakalim, on the other hand, are potent openers of cardiac KATP channels (Nichols and Lederer, 1991).

KATP channels are formed by the interaction of two distinct protein subunits: the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR1 or SUR2; Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1995; Inagaki et al., 1996), which is a member of the ATP-binding cassette transporter family, and a small inward rectifying potassium channel (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2; Inagaki et al., 1995, 1996). The functional role of the SUR and the Kir6 subunit in forming and regulating KATP channel activity has been investigated in several recent studies. Using mutations in a putative pore-lining residue in Kir6.2, we have directly demonstrated that Kir6.2 forms the ion conducting pathway (Shyng et al., 1997; Shyng and Nichols, 1997), and by expressing a Kir6.2 construct with a deletion of the COOH-terminal 26 or 36 amino acids. Tucker et al. (1997) showed that Kir6.2 was able to form ATP-sensitive potassium channels without coexpression of SUR. They further demonstrated that ATP sensitivity is significantly reduced by neutralization of a lysine residue at position 185 of Kir6.2, although normal sensitivity to ATP inhibition still requires coupling to SUR1. These studies establish that Kir6.2 functions as the KATP channel pore and carries some intrinsic ATP sensitivity. Diazoxide is used clinically to treat hyperinsulinemia; however, the molecular mechanism by which it stimulates KATP channels, and thereby inhibits insulin secretion, remains unknown. MgATP is normally required for diazoxide stimulation (Larsson et al., 1993), suggesting that nucleotide hydrolysis is required. SUR is structurally homologous to other ATP-binding cassette (ABC)1 transporter proteins within the two nucleotide binding folds (NBFs). We have previously reported that mutations in NBF2 of the SUR1 subunit can abolish stimulation of KATP channels by MgADP (Nichols et al., 1996). Gribble et al. (1997) showed that mutation of the Walker A lysine residue in NBF1 also abolishes ADP sensitivity. In the present study, we further investigated the role of the two NBFs of SUR1 in diazoxide and MgADP stimulation by site-directed mutagenesis in the two NBFs. The results indicate that activation of KATP channels by diazoxide and MgADP shares similar molecular mechanisms, involving both NBFs, and that, while NBF2 function is required for channel activation by both reagents, NBF1 function is important in determining the kinetics of the response.

methods

Expression of KATP Channels in COSm6 Cells

COSm6 cells were plated at a density of ∼2.5 × 105 cells per well (30-mm, six-well dishes) and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium plus 10 mM glucose (DMEM-HG), supplemented with fetal calf serum (10%). The following day, cells were transfected by incubation for 4 h at 37°C in DMEM containing 10% Nuserum, 0.4 mg/ml diethylaminoethyl-dextran, 100 μM chloroquine, and 5 μg each of pCMV6b-Kir6.2, pECE-SUR1, and pECE-GFP (green fluorescent protein) cDNA. Cells were subsequently incubated for 2 min in HEPES-buffered salt solution containing DMSO (10%), and returned to DMEM-HG plus 10% FCS.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Constructs containing point mutations were prepared by overlap extension at the junctions of the relevant residues by sequential polymerase chain reaction. Resulting PCR products were subcloned into pECE vector and sequenced to verify the correct mutant construct, before transfection.

Patch-Clamp Measurements

Patch-clamp experiments were made at room temperature, in an oil-gate chamber that allowed the solution bathing the exposed surface of the isolated patch to be changed in <50 ms (Lederer and Nichols, 1989). Micropipettes were pulled from thin-walled glass (WPI, New Haven, CT) on a horizontal puller (Sutter Instruments, Co., Novato, CA). Electrode resistance was typically 0.5–1 MΩ when filled with K-INT solution (see below). Microelectrodes were ‘sealed' onto cells that fluoresced green under UV illumination, by applying light suction to the rear of the pipette. Inside-out patches were obtained by lifting the electrode and passing the electrode tip through the oil-gate. Membrane patches were voltage clamped with an Axopatch 1B patch-clamp (Axon Inc., Foster City, CA). All currents were measured at a membrane potential of −50 mV (pipette voltage = +50 mV). Inward currents at this voltage are shown as positive-going signals. Data was normally filtered at 0.5–3 kHz, signals were digitized at 22 kHz (Neurocorder; Neuro Data Instruments Corp., NY) and stored on video tape. Experiments were replayed onto a chart recorder, or digitized into a microcomputer using Axotape software (Axon Inc.). The standard bath (intracellular) and pipette (extracellular) solution used in these experiments (K-INT) had the following composition (mM): 140 KCl, 10 K-HEPES, 1 K-EGTA, with additions as described. The solution pH was 7.3. Calculations of free [Mg2+] were made with a program written by M. Kurzmak (Department of Biological Chemistry, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD), which was based on the formulations of Fabiato and Fabiato (1979).

Data Analysis

Off-line analysis was performed using Axotape and Microsoft Excel programs. Wherever possible, data are presented as mean ± SEM. Microsoft Solver was used to fit data by a least-square algorithm.

results

Stimulation of KATP Channel Activity by Diazoxide Requires the Presence of Mg2+ and Hydrolyzable Nucleotides

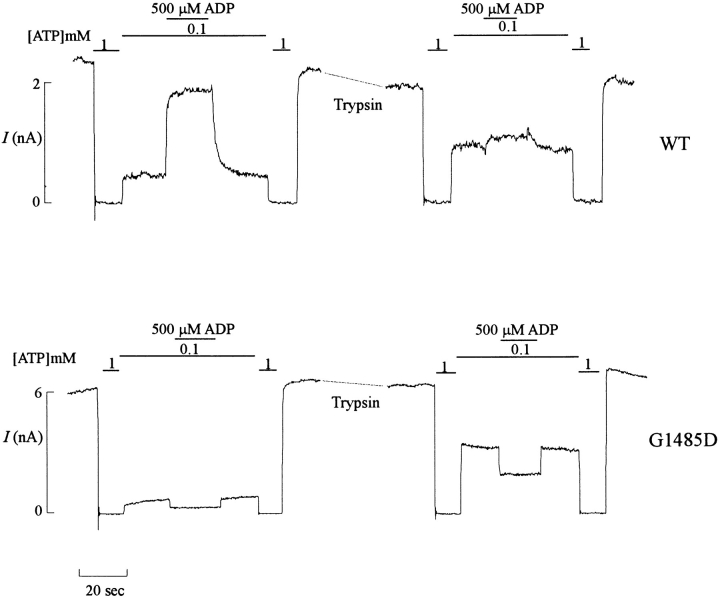

Expression of SUR1 and Kir6.2 subunits in COSm6 cells generates channels with properties similar to those of pancreatic β cell channels (Fig. 1). Previous work on native pancreatic β cell KATP channels has shown that the stimulatory effect of diazoxide requires the presence of Mg2+ and hydrolyzable nucleotides (Larsson et al., 1993). Diazoxide opened KATP channels in the presence of inhibitory ATP (Fig. 1 A), and exclusion of Mg2+ from the bath solution abolished the ability of diazoxide to stimulate the channel (Fig. 1 B). Substituting ADP for ATP produced similar stimulatory effects of MgADP (Fig. 1 C), although a high concentration of ADP (10 mM) was required to inhibit channels to a similar extent as 100 μM ATP. These results are consistent with the idea that diazoxide stimulation is a process that requires nucleotide hydrolysis or binding of Mg2+-bound nucleotides.

Figure 1.

Diazoxide stimulation of recombinant KATP channels requires hydrolyzable nucleotides. Representative currents (n = 4–5 patches) recorded from inside-out membrane patches containing wild-type KATP channels at −50 mV. Inward currents are shown as upward deflections. Patches were exposed to differing [ATP], [ADP], [diazoxide], and [Mg2+] as indicated by the bars above the records.

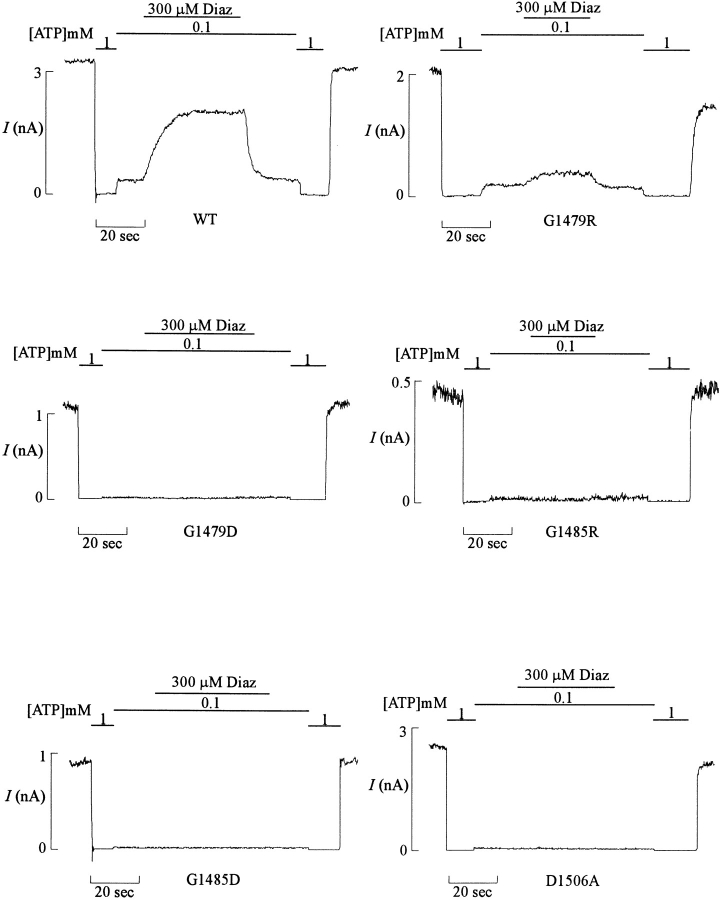

Mutations in NBF2 of SUR1 Abolish the Ability of the Channel to Respond to Diazoxide

Three sequence motifs are well conserved within the ABC transporter superfamily. Two of these, Walker A and B, form the nucleotide binding pocket and are predicted to interact with the phosphoryl group and to coordinate Mg2+ in the MgATP complex (Schlichting et al., 1990). The third motif lies between the two Walker consensus sequences and has been proposed to function as a linker that transduces the effect of nucleotide binding and hydrolysis (Mimura et al., 1991; Shyamala et al., 1991). Our previous work on a persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (PHHI) disease-associated point mutation of SUR1 has demonstrated that the linker region of the second nucleotide binding fold (NBF2) is involved in stimulation of the channel by MgADP (Nichols et al., 1996). The same mutation (G1479R) also caused a reduction in the response of the channel to stimulation by diazoxide. To extend our knowledge on the role of NBF2 in channel stimulation by diazoxide and MgADP, we constructed additional point mutations in NBF2 and examined their effects on expressed channel activity. Fig. 2 shows representative currents recorded from various mutations and compares their responses to diazoxide.

Figure 2.

Diazoxide stimulation is reduced or abolished by NBF2 mutations. Representative currents (n = 3–5 patches) recorded from inside-out membrane patches containing wild-type or NBF2 mutant KATP channels (as indicated) at −50 mV. Patches were exposed to differing [ATP] and [diazoxide], as indicated by the bars above the records. Free [Mg2+] was maintained at 1 mM in all ATP-containing solutions.

In this, and all subsequent figures, the effects of ADP are examined in the presence of 1 mM free Mg2+. These mutations were chosen because equivalent residues in the linker regions of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) nucleotide binding folds have previously been implicated in activation of CFTR chloride channels by ATP hydrolysis (Smit et al., 1993; Carson and Welsh, 1995). Except for mutation G1479R, which still retains some sensitivity to activation by diazoxide, all other NBF2 mutations, including G1479D, G1485D, G1485R, Q1486H, and D1506A, failed to respond to diazoxide (see Figs. 2 and 4). Increasing diazoxide to ∼1 mM, at which diazoxide solubility is exceeded, still resulted in no stimulation (not shown). Residue G1479 is situated very close to the ‘linker' region that is proposed to couple nucleotide hydrolysis to downstream actions in several ABC proteins (Smit et al., 1993; Carson and Welsh, 1995), and residues G1485 and Q1486 lie directly within it. Q1486 in SUR1 is homologous to residue H1350 in CFTR, and mutation of H1350 to Q reduces CFTR Cl− channel burst duration. By analogy to the effects of similar mutations in G-proteins (Der et al., 1986; Kleuss et al., 1994), this effect has been proposed to result from an increased ATP hydrolysis rate (Carson and Welsh, 1995), and therefore mutation Q1486H in SUR1 may cause a decrease in the hydrolysis rate at NBF2. Residue D1506 is located in the Walker B region of NBF2. Mutations of equivalent residues in CFTR have been shown to affect channel activities, presumably by affecting binding and/or hydrolysis of ATP, or by affecting the transduction of nucleotide binding and hydroly-sis to channel opening and closing (Anderson and Welsh, 1992; Smit et al., 1993; Carson and Welsh, 1995).2 These results are consistent with the notion that NBF2 plays a crucial role in channel stimulation by diazoxide.

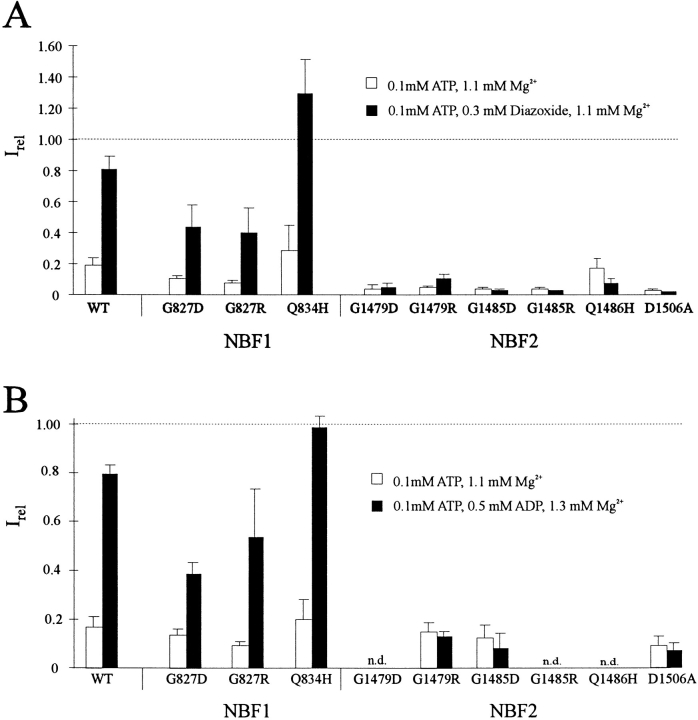

Figure 4.

Currents (see text) in 0.1 mM ATP solutions, relative to current in zero ATP solution, with (filled columns) and without (open columns) (A) 0.3 mM diazoxide, or (B) 0.5 mM ADP. Bars indicate mean ± SEM for n = 3–6 patches in each case. n.d., not done. Free Mg2+ was maintained at 1 mM in all ATP-containing solutions.

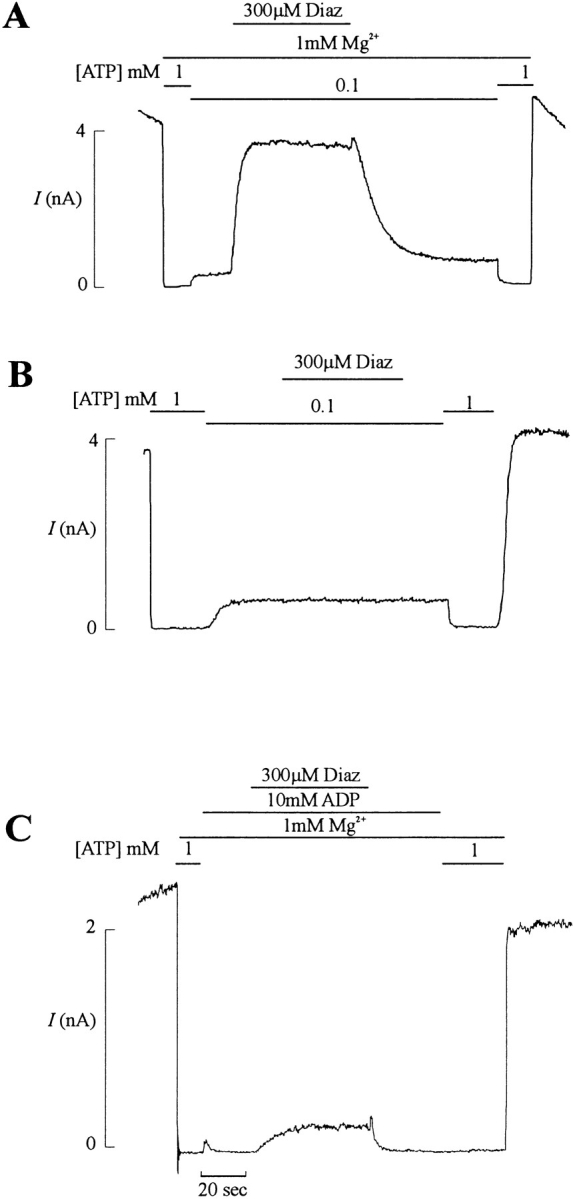

Mutations in NBF1 Alter the Kinetics of Channel Response to Stimulation by Diazoxide

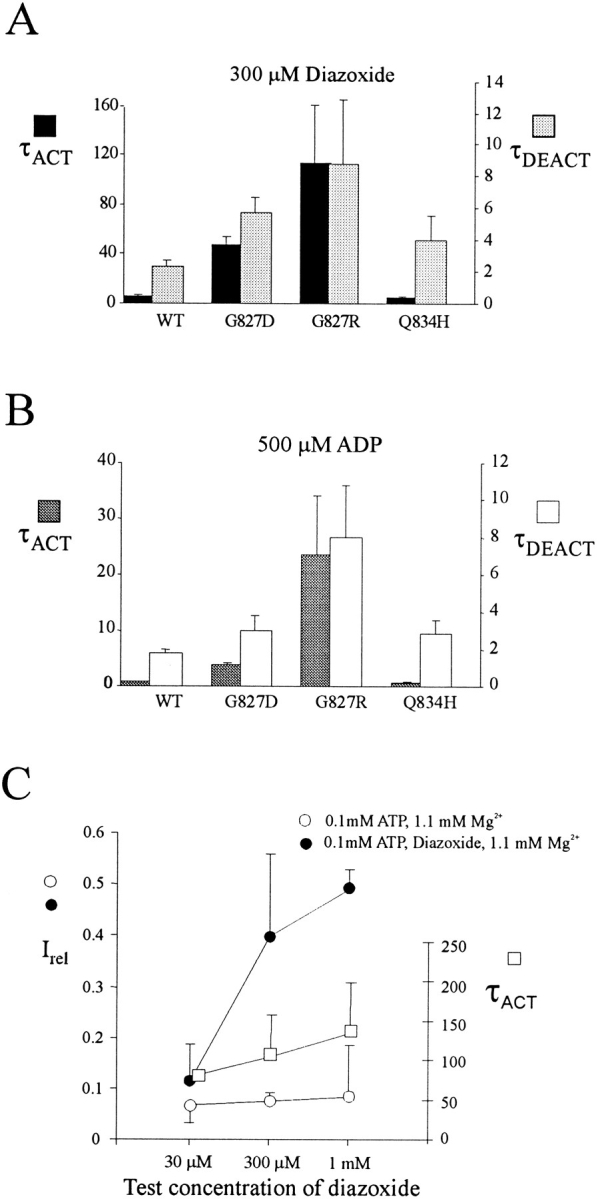

To investigate the involvement of the first nucleotide binding fold in diazoxide stimulation, we introduced homologous mutations to those described for NBF2 into NBF1. Mutating residue D854 (D1506 equivalent) in Walker B1 to alanine resulted in no functional channels, as assessed both by Rb efflux assay and by patch-clamp measurement (not shown). Mutating G827 (G1479 equivalent) to D or R caused a dramatic alteration in the kinetics of channel activation by diazoxide (Fig. 3). Channel activation during exposure to diazoxide and channel deactivation after removal of diazoxide are slowed in both G827D and G827R channels (Fig. 3). Both the activation and deactivation are reasonably well described by single exponentials. Activation time constants are increased ∼10- and 20-fold for G827D and G827R channels, respectively, and deactivation time constants are increased ∼2- and 4-fold for G827D and G827R channels, respectively (Fig. 5 A). In addition, the steady state activation by diazoxide is reduced in the G827 mutant channels when compared with the wild-type channel (Fig. 4 A). In contrast to the G827 mutant channels, the Q834H (equivalent to Q1486H) mutant channel showed enhanced response to diazoxide stimulation (Figs. 3 and 4 A), although the activation and deactivation time constants did not differ significantly from those of the wild-type channel (Fig. 5 A).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of diazoxide stimulation are altered by NBF1 mutations. Representative currents (n = 3–6 patches) recorded from inside-out membrane patches containing wild-type or NBF1 mutant KATP channels (as indicated) at −50 mV. Patches were exposed to differing [ATP] and [diazoxide], as indicated by the bars above the records. Free [Mg2+] was maintained at 1 mM in all ATP-containing solutions.

Figure 5.

Time constants of activation (τACT) and deactivation (τDEACT) during and after stimulation by (A) diazoxide or (B) ADP for wild-type (WT) and various mutant KATP channels. Bars indicate mean ± SEM for n = 3–6 patches in each case. (C) Currents (see text) in 0.1 mM ATP solution relative to current in zero ATP solution, with (•) and without (○, control) diazoxide, and time-constants of activation (τACT) during stimulation by diazoxide, versus the test diazoxide concentration, for G827R mutant channels. Free Mg2+ was maintained at 1 mM in all ATP-containing solutions.

One potential explanation for the altered diazoxide-activation kinetics in G827 mutant channels could be changes in the diazoxide binding rates. As shown in Fig. 5 C, this possibility can be discounted, for even though the stimulatory effect of diazoxide on G827R mutant channels was clearly dose dependent, there was no increase in activation rate (i.e., decrease in activation τ) with concentration. If anything, the time constant of activation increased with [diazoxide].

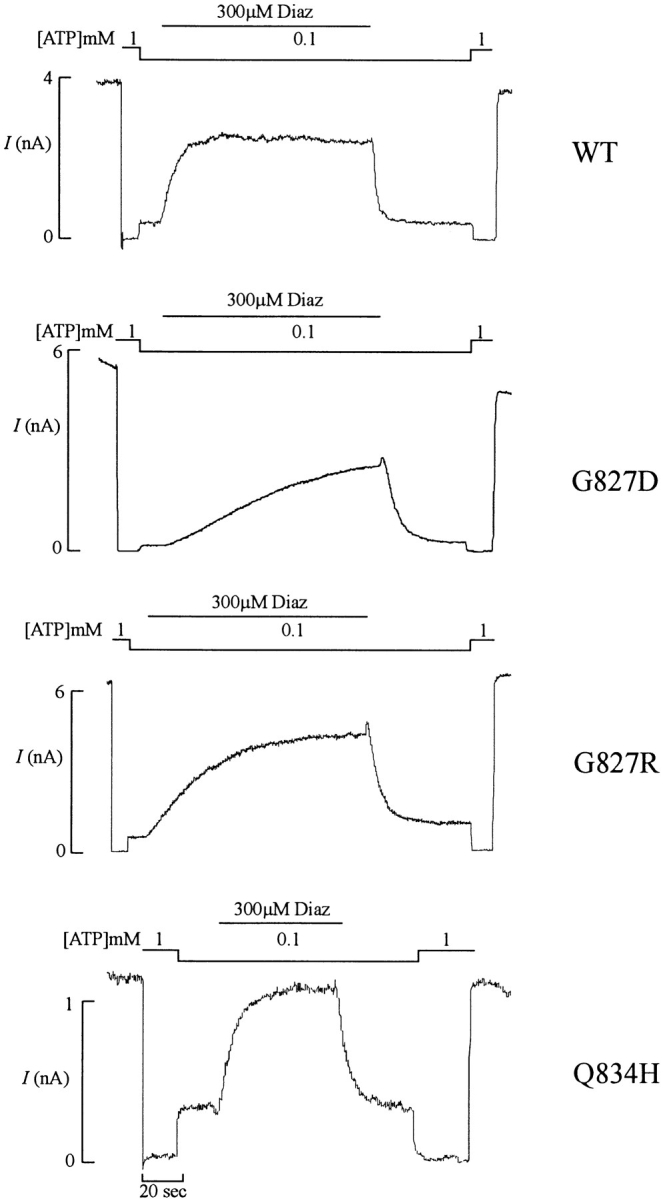

Similar Effects of the NBF Mutations on Stimulation of Channel Activity by MgADP

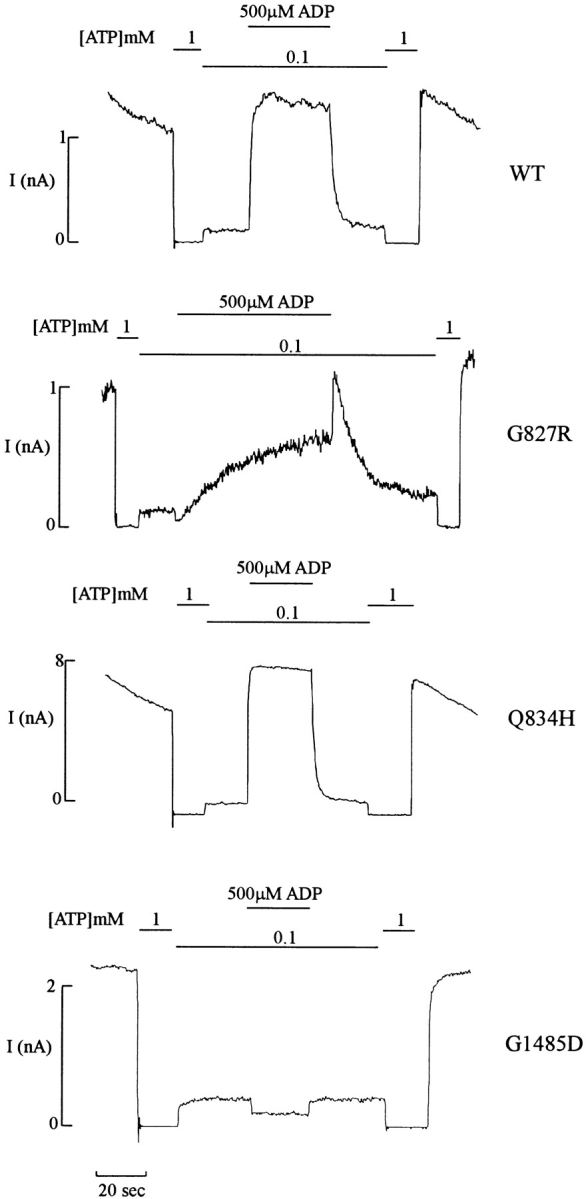

The observations that stimulation of KATP channels by ADP and by diazoxide both require Mg2+ and hydrolyzable nucleotides (Fig. 1; Dunne and Petersen, 1986; Kakei et al., 1986; Misler et al., 1986; Findlay, 1988; Lederer and Nichols, 1989) suggest that the two processes may share common molecular mechanisms. Comparison of the effects of NBF mutations on diazoxide and ADP stimulation reveals striking parallels (Fig. 4). All NBF2 mutations tested (G1479R, G1485D, D1506A) abolish stimulation by MgADP. Mutations in NBF1 either increase (Q834H) or decrease (G827D, G827R) the stimulatory ability of MgADP, comparable to the effects of these mutations on diazoxide stimulation. The slow kinetics of activation by diazoxide in G827 mutations are similarly correlated with slow kinetics of activation by MgADP (Figs. 5 B and 6). Although the time course of MgADP stimulation is much faster than that of diazoxide stimulation, a prolonged activation and deactivation phase are clearly observed in G827 mutants compared with wild-type channels (Figs. 5 B and 6).

Figure 6.

ADP stimulation is abolished by NBF2 mutations, and the kinetics are altered by NBF1 mutations. Representative currents recorded from inside-out membrane patches (n = 4–7) containing wild-type or mutant KATP channels (G827R and Q834H in NBF1, G1485D in NBF2) at −50 mV. Patches were exposed to differing [ATP] and [ADP], as indicated by the bars above the records. Free [Mg2+] was maintained at 1 mM in all ATP-containing solutions.

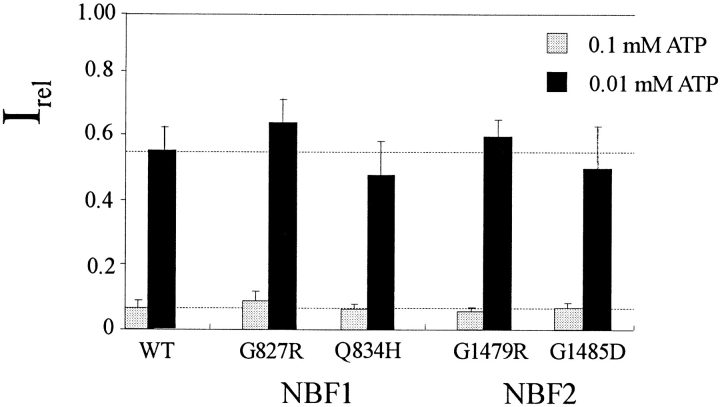

ATP Sensitivity of the Mutant Channels

While it was initially expected that the nucleotide binding folds of SUR would be involved in ATP inhibition, the recent demonstration of SUR-independent ATP-sensitive channel activity (Tucker et al., 1997), lack of effects of other SUR NBF mutations on ATP sensitivity (Nichols et al., 1996; Gribble et al., 1997), and the effects of Kir6.2 pore mutations on ATP sensitivity (Shyng et al., 1997), it now appears that inhibitory ATP binding is occurring at a different site. However, in the presence of Mg2+, there is clearly a negative correlation between the sensitivity of mutant channels to ATP inhibition and to diazoxide stimulation (Fig. 4). As discussed below, we interpret the mutational effects on diazoxide stimulation to altered MgATP hydrolysis rates, or altered coupling of such hydrolysis to channel activation, MgATP hydrolysis somehow causing a desensitization to inhibitory ATP. We therefore suggest (see below) that the primary effects of diazoxide and ADP are to stabilize the channel in a desensitized state that results from MgATP hydrolysis, and that some MgATP-dependent stimulation occurs even without the addition of these compounds. Therefore, mutations that increase the stimulatory effect of hydrolysis (e.g., Q834H) increase channel activity in 100 μM MgATP, whereas those that reduce the stimulatory MgATP hydrolysis effects (e.g., all NBF2 mutations) reduce channel activity in 100 μM MgATP, relative to wild type. If this hypothesis is correct, then the sensitivity to ATP4− (i.e., in the absence of Mg2+, and hence the absence of nucleotide hydrolysis) should be unaffected by these NBF mutations. Despite the profound effects of the NBF mutations on channel response to stimulation by MgADP and by diazoxide (Fig. 4), none of the mutations showed significant differences in their sensitivity to ATP inhibition in the absence of Mg2+, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity to ATP in the absence of Mg2+ is unaltered by NBF1 or NBF2 mutations. Currents in 0.1 or 0.01 mM ATP solutions relative to current in zero ATP solution for wild-type (WT) and mutant channels as indicated. Bars indicate mean ± SEM for n = 4–5 patches in each case.

It is apparent in certain records that the response to diazoxide and MgADP is biphasic. Application of ADP or diazoxide always induces a transient decrease of current, and there is a transient increase of current when these agents are removed. While this effect is particularly striking in the example shown for MgADP stimulation of G827R channels in Fig. 6, the effect is highly variable from patch to patch. It is, however, most obvious in constructs that show a slowing of kinetic response to activators (such as G827R), presumably because it reflects a separate mechanism that is temporally resolved by slowing down the activation response. In the absence of Mg2+, ADP3− exerts an ATP4−-like inhibitory effect on KATP channels, acting through the inhibitory nucleotide-binding site (Findlay, 1988; Lederer and Nichols, 1989; Bokvist et al., 1991). Therefore, in mutations that show no stimulation by MgADP or diazoxide (i.e., NBF2 mutations), there is a noticeable inhibitory effect of ADP (Figs. 4 and 6). We also observe a variable weak inhibition of such channels by diazoxide in the absence of Mg2+ (e.g., G1479D and G1485R channel records in Fig. 2, and has also been noted in other mutations that abolish MgADP stimulation by Gribble et al., 1997), suggesting that the transient effects represent inhibition and relief due to direct effects of diazoxide and ADP3−.

discussion

KATP channels are unique among K channels in requiring an ABC transporter protein subunit (SUR1 or SUR2) in addition to a Kir channel subunit (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2) to reconstitute channel activity (Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1995; Inagaki et al., 1995). Evidence to date suggests that the sulfonylurea receptor subunit confers regulation by nucleotides and pharmacological agents, such as sulfonylureas and potassium channel openers, and that the inward rectifier Kir6.2 subunit forms the ion conducting pore (Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1995; Nichols et al., 1996; Inagaki et al., 1996; Shyng et al., 1997; Gribble et al., 1997; Tucker et al., 1997). Loss of KATP channel function in pancreatic β cells is associated with the disease persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (Thomas et al., 1995; Kane et al., 1996), and at least one disease is caused by a mutation (G1479R) that is probably acting by abolishing MgADP stimulation of channel activity (Nichols et al., 1996). Like diazoxide, MgADP activates KATP channels in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of ATP, and both processes require Mg2+ and hydrolyzable nucleotides (Dunne et al., 1986; Kakei et al., 1986; Misler et al., 1986; Findlay, 1988; Lederer and Nichols, 1989; Larsson et al., 1993). Gribble et al. (1997) have recently shown that mutation of the conserved lysine residues in the Walker A motifs of either NBF1 (mutation K719A) or NBF2 (mutation K1384M), which are predicted to reduce ATP hydrolytic activity (Azzaria et al., 1989; Carson et al., 1995; Ko and Pedersen, 1995), can block the stimulatory effect of MgADP. In that study, diazoxide stimulated K1384M (NBF2 mutant) channels, but failed to stimulate K719A (NBF1 mutant) channels, leading to the suggestion that hydrolysis at NBF1 was most critical for diazoxide stimulation. In the present study, we show that, whereas mutations in the linker and Walker B motifs of the second nucleotide binding fold can abolish channel activation by diazoxide or MgADP, analogous mutations in NBF1 control the kinetics of activation. Based on these results, we suggest that nucleotide hydrolysis at both NBFs is involved, and propose a model for gating of the KATP channel in which MgADP and diazoxide stimulate channel activity by stabilizing an open state resulting from this hydrolysis.

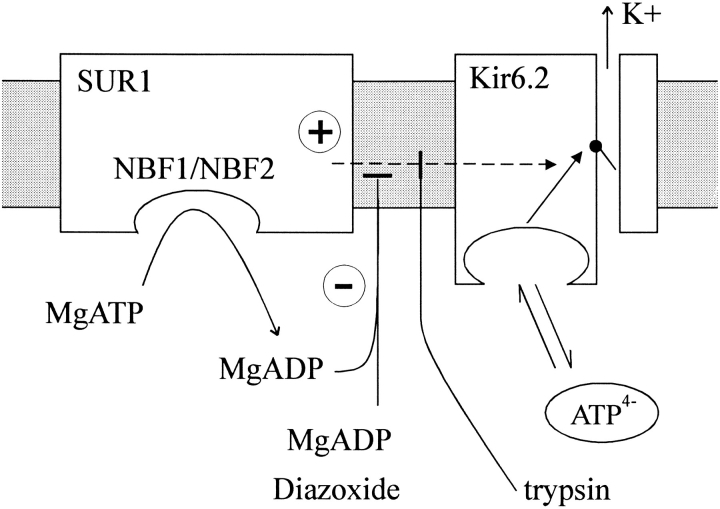

Proposed Model for Gating of the KATP Channel by MgADP and by Diazoxide: ‘SUR Sensitivity Switch'

It is clear that Kir6.2 subunits form the KATP channel pore in a directly homologous, and probably tetrameric, arrangement to that of other homomeric K channels that do not require an ABC protein subunit (MacKinnon, 1991; Yang et al., 1995; Glowatzki et al., 1996; Clement et al., 1997; Inagaki et al., 1997; Shyng et al., 1997; Shyng and Nichols, 1997). Tucker et al. (1997) have demonstrated that a COOH-terminally truncated Kir6.2 (Kir6.2[ΔC26]) can actually form ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of SUR expression, although coexpression of this construct with SUR1 shifts the ATP sensitivity from an apparent K i ([ATP] causing half-maximal inhibition of channel activity) of ∼100 μM, to ∼10 μM; i.e., SUR1 coexpression appears to ‘sensitize' the channel to ATP. In native KATP channels (Nichols and Lopatin, 1993; Proks and Ashcroft, 1993), treatment with cytoplasmic trypsin increases the K i ∼10-fold, consistent with the notion that the sensitizing effect of SUR1 might be abolished by this proteolytic treatment. Based on these observations, we now propose that the Kir6.2 complex has an intrinsic ATP sensitivity (in wild-type channels) of ∼100 μM, and that in the absence of nucleotide hydrolysis at the nucleotide binding folds, SUR1 exerts a ‘hypersensitizing' effect that reduces K i for ATP inhibition to ∼10 μM. We then propose that nucleotide hydrolysis uncouples the sensitizing effect, increasing channel activity at intermediate [ATP] (Fig. 8, Nichols et al., 1996).

Figure 8.

Model to explain nucleotide regulation of KATP channels. The SUR1 subunit acts as a ‘hypersensitivity switch' to modulate ATP sensitivity. ATP4− binds to either the Kir6.2 subunit itself, or a third, unknown protein to close KATP channels with an intrinsic K i of ∼100 μM (Tucker et al., 1997). When coupled to the SUR1 subunit, SUR1 exerts a hypersensitizing effect on channel activity to reduce the K i to ∼10 μM (Inagaki et al., 1995). This hypersensitizing switch is turned off by nucleotide hydrolysis at the SUR1 NBFs, and this effect is mimicked or enhanced by MgADP or diazoxide. Alternatively, the hypersensitizing effect is abolished when the channels are treated with trypsin, such that MgADP and diazoxide can no longer stimulate channel activity.

This model makes certain testable predictions. Firstly, if either MgADP or diazoxide stimulation and trypsin treatment are both uncoupling the hypersensitizing effect of SUR1, then the two effects should be nonadditive. As shown in Fig. 9, this is indeed the case. MgADP activates wild-type channels before trypsin treatment, but channel activity is increased (in 100 μM MgATP) after trypsin treatment, and little further stimulation occurs on application of MgADP. Secondly, in channels that are insensitive to MgADP or diazoxide, the hypersensitizing effect of SUR1 should still be removable by trypsin treatment. As shown in Fig. 9 (bottom), trypsin treatment increases the activity of G1485D mutant channels, which remain insensitive to MgADP stimulation. Thirdly, mutant Kir6.2 channels that are active in the absence of SUR1 should be insensitive to trypsin treatment. While the experiment has not been done, the hypothesis predicts that ATP sensitivity of Kir6.2[ΔC26], expressed in the absence of SUR1 (Tucker et al., 1997), will be unaffected by trypsin treatment.

Figure 9.

Trypsin treatment abolishes ADP stimulation of wild-type channels and shifts ATP sensitivity in wild-type and NBF mutant channels. Representative currents recorded from inside-out membrane patches containing wild-type (n = 3) or G1485D (n = 4) mutant KATP channels (as indicated) at −50 mV. Patches were exposed to differing [ATP] and [ADP], as indicated by the bars above the records. Each record is cut (dashed line) for ∼60 s during application of trypsin at 1 mg/ml, as indicated. Free [Mg2+] was maintained at 1 mM in all ATP-containing solutions.

It is not clear exactly how SUR1 modulates the ATP sensitivity, although the effect need not be through alteration of ATP binding. As we discussed previously (Shyng et al., 1997), alterations in the coupling of ATP-independent transitions could cause significant shifts in apparent K i. However, such an effect should be reflected in an increase of channel open probability in the absence of ATP. While we did not examine ADP or diazoxide effects in the absence of ATP, stimulation of channel activity by MgADP in the absence of ATP has been shown by others (e.g., Gribble et al., 1997). Such an action could also account for stimulation to levels greater than that seen in the absence of ATP (e.g., stimulation by diazoxide in Q834H channels; Fig. 4).

How, then, are MgADP and diazoxide acting? Even in the absence of these agents, hydrolyzable MgATP clearly has some uncoupling effect on ATP sensitivity. As shown in Fig. 4, there is a correlation between the channel activity in 100 μM MgATP, and the stimulatory effects of both ADP and diazoxide, even though sensitivity to ATP in the absence of Mg2+ ions is unaffected by the various mutations (Fig. 7). Based on the striking correlation between diazoxide and MgADP effects, we propose that these agents both act as stabilizers of the uncoupled SUR1 state that results from hydrolysis, either because they act as hydrolysis products (MgADP) or perhaps as mimics of a transition or hydrolysis state (diazoxide). Thus, the kinetics of activation by these agents, and deactivation after their removal, will reflect both the stability of this state and the rate of ATP hydrolysis.

Comparison to Proposed Models for Nucleotide Gating of CFTR Channels

SUR1 shares sequence and structure homology to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and other members of the ABC transporter protein family (Higgins, 1995). The molecular gating mechanism of the KATP channel proposed here bears analogy to those proposed for CFTR (Smit et al., 1993; Baukrowitz et al., 1994; Gunderson and Kopito, 1995; Carson and Welsh, 1995). In CFTR, MgATP stimulates channel activity, and this stimulation is antagonized by ADP. Mutational studies of the two nucleotide binding domains suggest that ADP inhibits CFTR channel activity through interaction with NBF2 but not NBF1 (Anderson and Welsh, 1992). We similarly showed that the disease-associated SUR1 NBF2 mutation G1479R causes the KATP channel to lose its ability to be stimulated by MgADP (Nichols et al., 1996), and results from the present study further demonstrate the importance of the second nucleotide binding fold in mediating the stimulatory effects of MgADP and of diazoxide.

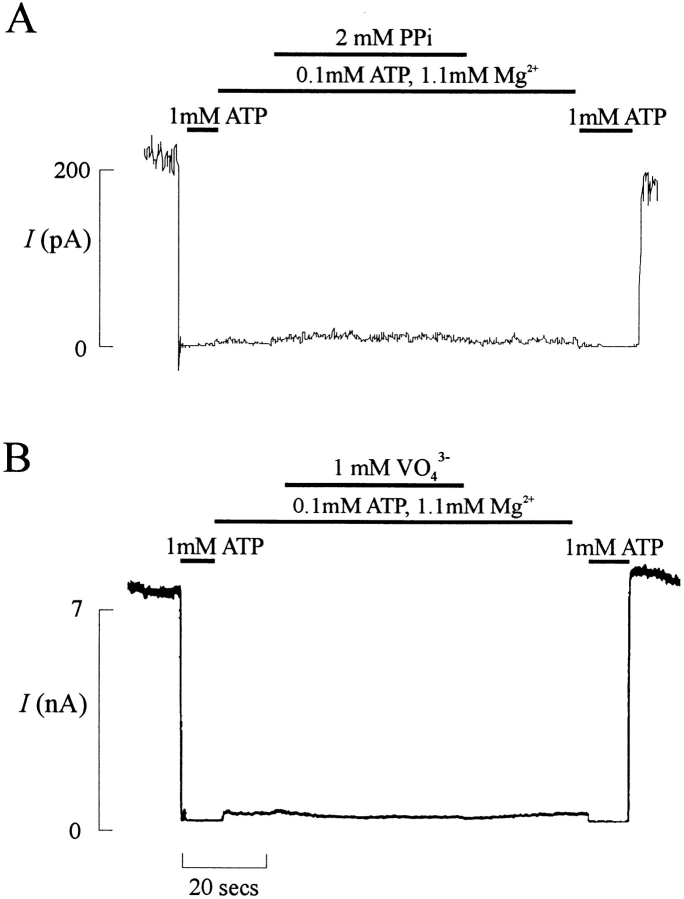

Although intracellular MgADP imposes opposite end effects on channel opening and closing in CFTR and the KATP channel, the mechanisms by which it regulates the two channels might be similar. Ko and Pedersen (1995) have shown that isolated CFTR NBF1, which is homologous to SUR NBFs, is capable of hydrolysis. Hydrolysis by the SUR nucleotide-binding folds has not been demonstrated, although we can show ATP binding to isolated NBF1 and NBF2 purified from fusion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli (Shyng, S.L., and C.G. Nichols, unpublished results). Considering the present results and those of Gribble et al. (1997), it is clear that both NBFs are involved in diazoxide and MgADP stimulation of channel activity, but at this juncture we cannot discriminate between independent nucleotide hydrolysis at each NBF, or a concerted hydrolysis reaction involving both. In CFTR, a cyclical model of activation by ATP has been presented (Baukrowitz et al., 1994; Gunderson and Kopito, 1995; Carson et al., 1995), in which ATP hydrolysis causes channel opening, and the channel can be ‘locked' in this activated state by application of hydrolysis transition state analogs such as vanadate or pyrophosphate ions. We considered the possibility that such a cycle may operate in SUR regulation of KATP channel activity and attempted to mimic the stimulatory effects of MgADP and diazoxide on KATP channels by these analogs. However, unlike their effects on CFTR, neither pyrophosphate nor VO4 altered channel activity significantly (Fig. 10). Thus, there is no compelling reason for presenting a hydrolysis cycle model to couple NBF function to channel activity such as that proposed for CFTR. On the other hand, the present results are consistent with a requirement for nucleotide hydrolysis in activation of the channel, and with diazoxide and ADP either stimulating hydrolysis or stabilizing the channel in the ‘desensitized' state that results from hydrolysis. While it seems likely that MgADP exerts its effect through binding to the NBFs, the structural element in SUR1 that binds to diazoxide has not been identified. Nevertheless, the striking similarity of the effects of different mutations on stimulation by MgADP and diazoxide argues for a common pathway of action and it is tempting to speculate that diazoxide also binds at the NBFs.

Figure 10.

Pyrophosphate and vanadate do not activate KATP channels. Representative currents (n = 3 in each case) recorded from inside-out membrane patches containing wild-type KATP channels at −50 mV. Patches were exposed to differing [ATP], as indicated by the bars above the record. 2 mM pyrophosphate (PPi) or 1 mM vanadate (VO43 −) were added where indicated. Free [Mg2+] was maintained at 1 mM in all ATP-containing solutions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. S. Seino for providing us with the Kir6.2 clone. We are grateful to the Washington University Diabetes Research and Training Center for continued molecular biology support.

This work was supported by grant HL-45742 from the National Institutes of Health (C.G. Nichols), an Established Investigatorship from the American Heart Association (C.G. Nichols), and a Career Development Award from the American Diabetes Association (S.L. Shyng).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: ABC, ATP-binding cassette; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; NBF, nucleotide binding fold; SUR, sulfonylurea receptor.

It is apparent in Figs. 2 and 4 that mutations that reduce diazoxide activation also have a reduced activity in 100 μM ATP. As discussed below (see also Fig. 7), this does not result from a change in intrinsic sensitivity to inhibition by free ATP4−. More likely, it results from a degree of stimulation of channel activity resulting from ATP hydrolysis, even in the absence of diazoxide.

references

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Nichols CG, Wechsler SW, Clement JP, IV, Boyd AE, III, Gonzalez G, Herrera H, Sosa, Nguy K, Bryan J, Nelson DA. The β cell high affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MP, Welsh MJ. Regulation by ATP and ADP of CFTR chloride channels that contain mutant nucleotide-binding domains. Science. 1992;257:1701–1704. doi: 10.1126/science.1382316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1988;11:97–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzaria M, Schurr E, Gros P. Discrete mutations introduced in the predicted nucleotide binding sites of the mdr-1 gene abolish its ability to confer multidrug resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5289–5297. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Hwang TC, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Coupling of CFTR Cl−channel gating to an ATP hydrolysis cycle. Neuron. 1994;12:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokvist K, Ammala C, Ashcroft FM, Berggren P-O, Larsson O, Rorsman P. Separate processes mediate nucleotide-induced inhibition and stimulation of the ATP-regulated K++-channels in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1991;243:139–144. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MR, Welsh MJ. Structural and functional similarities between the nucleotide-binding domains of CFTR and GTP-binding proteins. Biophys J. 1995;69:2443–2448. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80113-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MR, Winter MC, Travis SM, Welsh MJ. Pyrophosphate stimulates wild-type and mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl−channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20466–20472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement JP, IV, Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, Schwanstecher M, Panten U, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Association and stoichiometry of KATPchannel subunits. Neuron. 1997;18:827–838. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der CJ, Finkel T, Cooper GM. Biological and biochemical properties of human ras Hgenes mutated at codon 61. Cell. 1986;44:167–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MJ, Petersen OH. Intracellular ADP activates K+channels that are inhibited by ATP in an insulin-secreting cell line. FEBS Lett. 1986;208:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A, Fabiato F. Calculator programs for computing the composition of the solutions containing multiple metals and ligands used for experiments in skinned muscle cells. J Physiol (Paris) 1979;75:463–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay I. Effects of ADP upon the ATP-sensitive K+channel in rat ventricular myocytes. J Membr Biol. 1988;101:83–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01872823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowatzki E, Fakler G, Brandle U, Rexhausen U, Zenner HP, Ruppersberg JP, Fakler B. Subunit-dependent assembly of inward-rectifier K+channels. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1995;261:251–261. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. The essential role of the Walker A motifs of SUR1 in K-ATP channel activation by Mg-ADP and diazoxide. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1997;16:1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson KL, Kopito RR. Conformational states of CFTR associated with channel gating: the role of ATP binding and hydrolysis. Cell. 1995;82:231–239. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins CF. The ABC of channel regulation. Cell. 1995;82:693–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90465-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzales G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Wang CZ, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Seino S. A family of sulfonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Seino S. Subunit stoichiometry of the pancreatic β-cell ATP-sensitive K+ channel. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakei M, Kelly RP, Ashcroft SJ, Ashcroft FM. The ATP-sensitivity of K+channels in rat pancreatic B-cells is modulated by ADP. FEBS Lett. 1986;208:63–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane C, Shepherd RM, Squires PE, Johnson PRV, James RFL, Milla PJ, Aynsley-Green A, Lindey KJ, Dunne MJ. Loss of functional KATP channels in pancreatic b-cells causes persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Nat Med. 1996;2:1344–1347. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleuss C, Raw AS, Lee E, Sprang SR, Gilman AG. Mechanism of GTP hydrolysis by G-protein α subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9828–9831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko YH, Pedersen PL. The first nucleotide binding fold of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator can function as an active ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22093–22096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Ammala C, Bokvist K, Fredholm B, Rorsman P. Stimulation of the KATP channel by ADP and diazoxide requires nucleotide hydrolysis in mouse pancreatic beta-cells. J Physiol (Camb) 1993;463:349–365. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederer WJ, Nichols CG. Nucleotide modulation of the activity of rat heart KATPchannels in isolated membrane patches. J Physiol (Camb) 1989;419:193–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R. Determination of the subunit stoichiometry of a voltage-activated potassium channel. Nature. 1991;350:232–235. doi: 10.1038/350232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura CS, Holbrook SR, Ames GF-L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:84–88. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misler S, Falke LC, Gillis K, McDaniel ML. A metabolite-regulated potassium channel in rat pancreatic B cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7119–7123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Lederer WJ. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H1675–H1686. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Lopatin AN. Trypsin and α-chymotrypsin treatment abolishes glibenclamide sensitivity of KATPchannels in rat ventricular myocytes. Pflügers Arch. 1993;422:617–619. doi: 10.1007/BF00374011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Shyng S-L, Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Clement J, IV, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Permutt AM, Bryan JP. Adenosine diphosphate as an intracellular regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1996;272:1785–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Modification of K-ATP channels in pancreatic β-cells by trypsin. Pflügers Arch. 1993;424:63–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00375103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DW, Steinberg ML. Potassium channel modulators: scientific applications and therapeutic promise. J Med Chem. 1990;33:1529–1541. doi: 10.1021/jm00168a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting I, Almo SC, Rapp G, Wilson K, Petratos K, Lentfer A, Wittinghofer A, Kabsch W, Pai EF, Petsko GA, Goody RS. Nature. 1990;345:309–315. doi: 10.1038/345309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyamala V, Baichwal V, Beall E, Ames GF-L. Structure–function analysis of the histidine permease and comparison with cystic fibrosis mutations. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18714–18719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S-L, Ferrigni T, Nichols CG. Control of rectification and gating of cloned KATP channels by the Kir6.2 subunit . J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:141–153. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S-L, Nichols CG. Octameric stoichiometry of the KATPchannel complex. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:655–664. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit LS, Wilkinson DJ, Mansoura MK, Collins FS, Dawson DC. Functional roles of the nucelotide-binding folds in the activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;88:84–88. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgess, N.C., M.L. Ashford, D.L. Cook, and C.N. Hales. 1985. The sulphonylurea receptor may be an ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Lancet. ii:474–475. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Terzic A, Findlay I, Hosoya Y, Kurachi Y. Dualistic behavior of ATP sensitive K+ channels toward intracellular nucleoside diphosphates. Neuron. 1994;12:1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzic A, Jahangir A, Kurachi Y. Cardiac ATP-sensitive K+channels: regulation by intracellular nucleotides and K+ channel-opening drugs. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C525–C545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.3.C525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PM, Cote GJ, Wohllk N, Haddad B, Mathew PM, Rabl W, Aguilar-Bryan L, Gagel RF, Bryan J. Mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor gene in familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Science. 1995;268:426–429. doi: 10.1126/science.7716548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Jan YN, Jan LY. Determination of the subunit stoichiometry of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Neuron. 1995;15:1441–1447. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]