Abstract

We have used the patch clamp technique to study the effects of inhibiting the apical Na+ transport on the basolateral small-conductance K+ channel (SK) in cell-attached patches in cortical collecting duct (CCD) of the rat kidney. Application of 50 μM amiloride decreased the activity of SK, defined as nP o (a product of channel open probability and channel number), to 61% of the control value. Application of 1 μM benzamil, a specific Na+ channel blocker, mimicked the effects of amiloride and decreased the activity of the SK to 62% of the control value. In addition, benzamil reduced intracellular Na+ concentration from 15 to 11 mM. The effect of amiloride was not the result of a decrease in intracellular pH, since addition 50 μM 5-(n-ethyl-n-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA), an agent that specifically blocks the Na/H exchanger, did not alter the channel activity. The inhibitory effect of amiloride depends on extracellular Ca2+ because removal of Ca2+ from the bath abolished the effect. Using Fura-2 AM to measure the intracellular Ca2+, we observed that amiloride and benzamil significantly decreased intracellular Ca2+ in the Ca2+-containing solution but had no effect in a Ca2+-free bath. Furthermore, raising intracellular Ca2+ from 10 to 50 and 100 nM with ionomycin increased the activity of the SK in cell-attached patches but not in excised patches, suggesting that changes in intracellular Ca2+ are responsible for the effects on SK activity of inhibition of the Na+ transport. Since the neuronal form of nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) is expressed in the CCD and the function of the nNOS is Ca2+ dependent, we examined whether the effects of amiloride or benzamil were mediated by the NO-cGMP–dependent pathways. Addition of 10 μM S-nitroso-n-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP) or 100 μM 8-bromoguanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate (8Br-cGMP) completely restored channel activity when it had been decreased by either amiloride or benzamil. Finally, addition of SNAP caused a significant increase in channel activity in the Ca2+-free bath solution. We conclude that Ca2+-dependent NO generation mediates the effect of inhibiting the apical Na+ transport on the basolateral SK in the rat CCD.

Keywords: nitric oxide synthase, Na+ channel, K+ channel, collecting duct, patch clamp

introduction

The cortical collecting duct (CCD)1 plays an important role in Na+ reabsorption and K+ excretion as evidenced by the fact that Na+ reabsorption and K+ secretion are finely regulated and controlled by several hormones, such as aldosterone and vasopressin (Schafer and Hawk, 1992; Palmer et al., 1993; Breyer and Ando, 1994). Na+ reabsorption and K+ secretion are two-step processes that involve several transport proteins such as ion channels and Na-K-ATPase (Smith and Benos, 1991; Palmer et al., 1993; Giebisch, 1995). Changes in channel activity or turnover rate of Na-K-ATPase may have a profound effect on K+ secretion and Na+ reabsorption in the CCD (Strieter et al., 1992a , 1992b ). Three functions are served by basolateral K+ channels. First, they participate in generating the cell membrane potential. Since K+ secretion and Na+ reabsorption are electrogenic processes, alteration of cell membrane potential has a significant effect on K+ secretion and Na+ reabsorption. It has been found that inhibition of the basolateral K+ conductance with Ba2+ reduced the Na+ reabsorption rate (Schafer and Troutman, 1987). Second, the K+ channels in the basolateral membrane are involved in K+ recycling across the basolateral membrane (Dawson and Richards, 1990), this recycling being important for maintaining the function of the Na-K-ATPase. Inhibition of K+ recycling diminished the short circuit current, an index for active Na+ transport, in frog skin (Urbach et al., 1996b ). Finally, the basolateral K+ channels provide a route for K+ entering the cell under conditions, such as hyperaldonism, in which the cell membrane potential exceeds the K+ equilibrium potential.

Three types of K+ channels, large conductance (>198 pS), intermediate conductance (85 pS), and small conductance (28 pS), have been found in the basolateral membrane of the CCD (Hirsch and Schlatter, 1993; Wang et al., 1994; Wang, 1995). The 28-pS K+ channel is predominant in the lateral membrane of the CCD in rats on either a normal or high potassium diet (Lu and Wang, 1996). In contrast, the 198-pS K+ channel is predominant in the basolateral membrane of the CCD in the rats on a low sodium diet (Hirsch and Schlatter, 1993). The small-conductance K+ channel (SK) is activated by nitric oxide via a cGMP-dependent pathway (Lu and Wang, 1996), but is insensitive to ATP (Wang et al., 1994).

It is well established that the basolateral K+ conductance is closely correlated with the activity of the basolateral Na-K-ATPase and Na+ transport across the apical membrane (Horisberger and Giebisch, 1988a , 1988b ; Harvey, 1995). Inhibition of the apical Na+ channels with amiloride reduced the basolateral K+ permeability in the toad urinary bladder (Davis and Finn, 1982). Horisberg and Giebisch (1988a) have further shown that inhibition of Na-K-ATPase reduced basolateral K+ conductance. On the other hand, stimulation of Na+ transport has been shown to increase the basolateral K+ conductance (Tsuchiya et al., 1992; Beck et al., 1993). Such “cross talk” between the apical Na+ transport and the basolateral K+ conductance is important in maintaining salt and water transport and ion concentration in the intracellular milieu (Schultz, 1981). The mechanisms of cross talk have been extensively explored and several candidates, including changes in pH, Ca2+, and ATP, for mediating the feed-back between apical Na+ transport and basolateral K+ channels, have been identified (Harvey, 1995). In the present study, we investigate the role of NO in linking activity of the basolateral K+ channels to apical Na+ transport.

methods

Preparation of Rat CCD

The CCDs were isolated from kidneys of pathogen-free Sprague-Dawley rats purchased from Taconic Farms Inc. (Germantown, NY) and the animals kept on either a normal rat chow diet or a high K+ diet. The kidneys were removed immediately after killing and thin coronal sections were cut with a razor blade. The CCD was dissected in HEPES-buffered NaCl Ringer solution containing (mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH) at 22°C and transferred onto a 5 × 5 mm cover glass coated with “Cell-Tak” (Collaborative Research Inc., Bedford, MA) to immobilize the tubules. The cover glass was placed in a chamber mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY) and the tubules were superfused with HEPES-buffered NaCl solution. The CCD was cut open with a sharpened micropipette and intercalated cells were then removed to expose the lateral membrane of principal cells. The temperature of the chamber (1,000 μl) was maintained at 37 ± 1°C by circulating warm water around the chamber.

Patch-clamp Technique

We used a patch-clamp amplifier (200A; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) to record channel current. The current was low pass filtered at 1 kHz using an 8-pole Bessel filter (902LPF; Frequency Devices Inc., Haverhill, MA) and was digitized at a sampling rate of 44 kHz using a modified PCM-501ES pulse code modulator (Sony Corp., Park Ridge, NJ) and stored on videotape (SL-2700; Sony Corp.). For analysis, data stored on the tape were transferred to an IBM-compatible 486 computer (Gateway 2000, Sioux Falls, South Dakota) at a rate of 4 kHz and analyzed using the pClamp software system 6.03 (Axon Instruments). Channel activity is defined as nP o and no efforts were made to determine whether alterations of channel activity were due to changes in channel number (n) or channel open probability (P o). The nP o was calculated from data samples of 30–60-s duration in the steady state as follows: nP o = Σ(t1 + t 2 +......tn), where tn is the fractional open time spent at each of the observed current levels.

Measurement of Intracellular Ca2+

Fluorescence was imaged digitally with an intensified video imaging system including a SIT 68 camera, controller, and HR 1000 video monitor (Long Island Industries, North Bellmore, NY). The exciting and emitted light passed through a 40× fluorite objective (NA = 1.30; Nikon Inc.). The microscope was coupled to an alternating wavelength illumination system (Ionoptix, Milton, MA). Digital images were collected at the rate of 10 ratio pairs/ min and analyzed with Ionoptix software (Ionoptix, Milton, MA).

The CCD was loaded with the fluorescent dye Fura-2 AM (5 μM) (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) at room temperature (22°C) for 30 min. At the end of the incubation period, the tubules were washed with the Ringer solution and transferred to a new cover glass coated with Cell-Tak. The cover glass was transferred to a chamber and the tubules were incubated for an additional 15 min before experiments. Three to seven cells were selected for each experiment. Dye in the tubule was excited with light of 340/380-nM wavelengths using a 75-W xenon source, and emission was recorded at 510 nM. The Ca2+ i was measured from the ratio of fluorescence at excitations of 340/380 nM and calculated using the equation described by Grynkiewicz et al. (1985): Ca2+ i = [(R − R min)/(R max − R)] × (F max/F min) × K d, where R is the measured ratio of emitted light, F max is the fluorescence at 380 nM with 0 mM Ca2+ bath solution, F min is the fluorescence at 380 nM with 2 mM Ca2+ bath solution, and K d = 225 nM for the Fura-2–calcium binding.

Measurement of Intracellular Na+ Concentrations

The same set-up used for measuring Ca2+ was employed to measure intracellular Na+. The split-open CCD was loaded with the fluorescent dye SBFI-AM (7 μM) and 0.001% pluronic acid (Molecular Probes, Inc.) at room temperature (22°C) for 60 min. At the end of the incubation period, the tubules were washed with the Ringer solution and transferred to a new cover glass coated with Cell-Tak. The cover glass was transferred to a chamber and the tubules were incubated for an additional 15 min before experiments. Three to seven cells were selected for each experiment. Dye in the tubule was excited with light of 340/380 nM wavelengths using a 75-W xenon source, and emission was recorded at 510 nM. Intracellular Na+ was measured from the ratio of fluorescence at excitations of 340/380-nM wavelengths. Fluorescence ratio was calibrated in situ by permeabilizing cells with 10 μM ionophore, lasalocid (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), and altering the Na+ concentration of the bath at the end of each experiment.

Experimental Solution and Statistics

The pipette solution contained (mM): 140 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.40 with KOH). The bath solution for cell-attached patches and for fluorescence measurements was composed of (mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.8 MgCl2, 5 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.40 with NaOH) under control conditions. The Ca2+-free bath was achieved by removal of Ca2+ and addition of 1 mM EGTA. To study the effect of Ca2+ on channel activity, the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations were clamped with 1 μM ionomycin when extracellular free Ca2+ was titrated to 10, 50, and 100 nM, respectively. Ionomycin, 8-bromoguanosine 3′: 5′-cyclic monophosphate (8Br-cGMP), L-arginine, and N-acetyl-penicillamine were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. S-nitroso- N-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP) was obtained from Calbiochem Corp. (La Jolla, CA), and 5-(n-ethyl-n-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA) was obtained from LC laboratory (Woburn, MA). Ionomycin, SNAP, and EIPA were dissolved in pure ethanol (Ionomycin and SNAP) or DMSO (EIPA). The final concentration of ethanol or DMSO in the bath was 0.1% and had no effect on channel activity. The chemicals were added directly to the bath to reach the final concentration.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM and paired Student's t test was used to determine the significance between the control and experimental periods. Statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05.

results

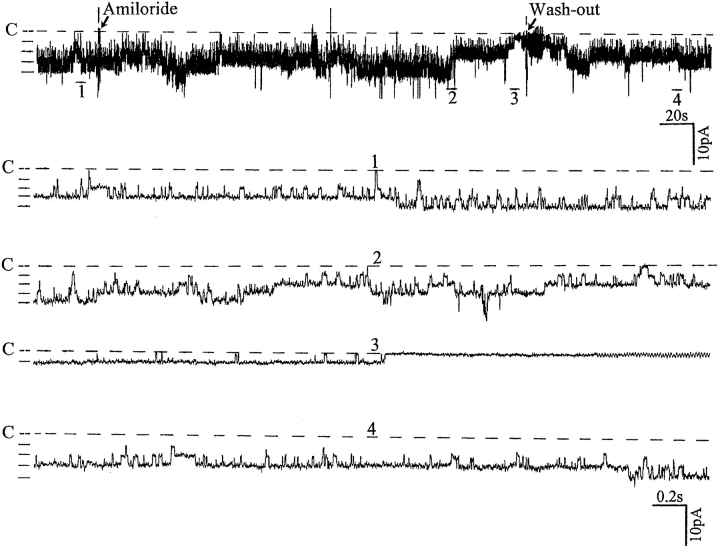

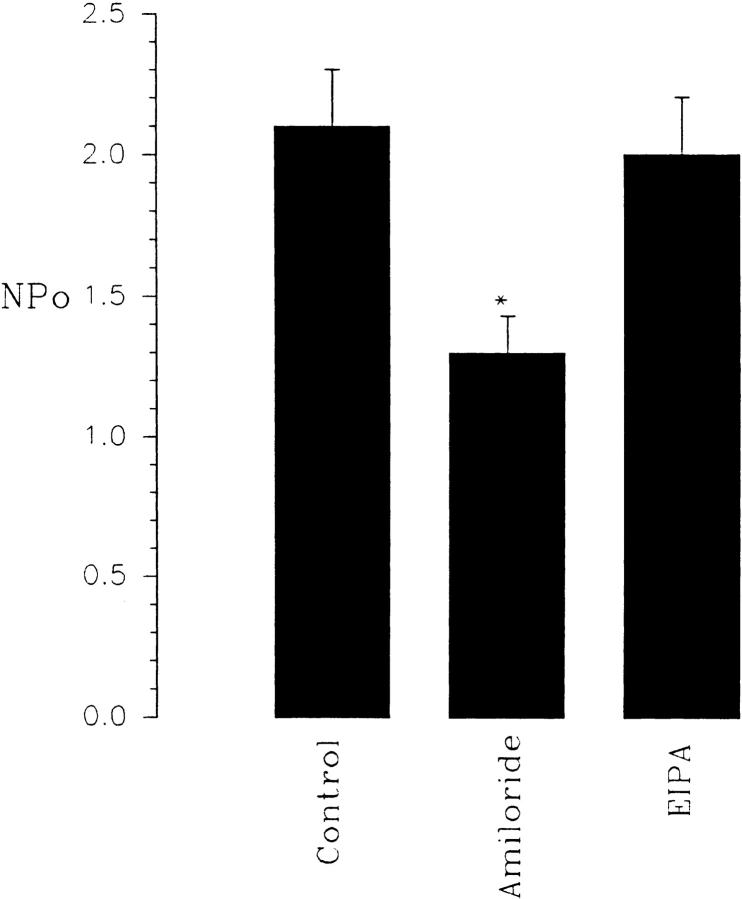

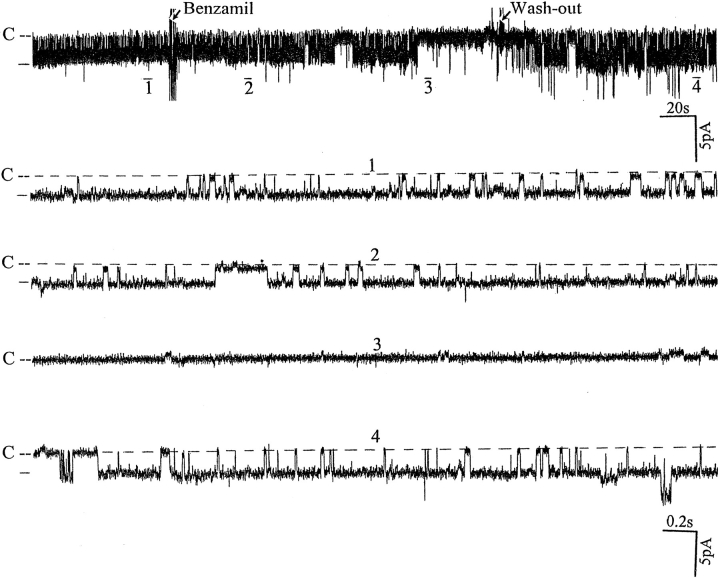

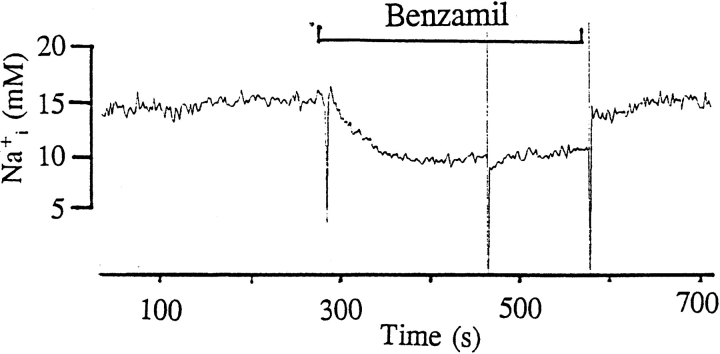

Fig. 1 is a representative recording made in a cell- attached patch showing the effect of 50 μM amiloride on the activity of the SK. It is apparent that addition of amiloride decreased the activity of the SK. In 10 experiments, we observed that 50 μM amiloride decreased nP o from 2.1 ± 0.2 to 1.3 ± 0.1 within 3–5 min (Fig. 2). The effect of amiloride was fully reversible and wash-out restored the channel activity. In addition to inhibiting Na+ channels, amiloride blocks Na/H exchange. To exclude the possibility that the effect of amiloride was the result of inhibiting the Na/H exchanger, we examined the effect of EIPA, an agent that specifically inhibits the Na/H exchanger without blocking Na+ channels (Gupta et al., 1989). Fig. 2 shows that addition of 50 μM EIPA had no significant effect on the SK in cell-attached patches (n = 5). To confirm further that the effect of amiloride on the SK was the result of inhibition of the Na+ channels, we investigated the effect of benzamil, a specific Na+ channel inhibitor (Kleyman and Cragoe, 1988). Fig. 3 shows that application of 1 μM benzamil mimicked the effect of amiloride and reduced channel activity in cell-attached patches by 38 ± 5% (n = 8). The notion that the effect of benzamil is the result of blocking Na+ transport is further indicated by experiments in which addition of 1 μM benzamil significantly reduced intracellular Na+ concentration from 15 ± 2 to 11 ± 2 mM (n = 5) (Fig. 4).

Figure 1.

Recording showing the effect of 50 μM amiloride on the activity of the SK in a cell-attached patch. The pipette solution contained 140 mM KCl and the bath solution was composed of (mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.40. The pipette holding potential was 0 mV. The arrows indicate addition of 50 μM amiloride and its removal. The channel closed level is indicated by C and a dotted line. The top trace shows the time course of the amiloride effects. Four parts of the trace (1–4) are extended to display the detail of the channel activity.

Figure 2.

Effects of 50 μM amiloride (n = 10) and 50 μM EIPA (n = 5) on the activity of the SK in cell-attached patches. *Data are significantly different from the control value.

Figure 3.

Recording showing the effect of 1 μM benzamil on the SK in a cell-attached patch. The pipette holding potential is −30 mV and the channel closed line is indicated by C. The trace (top) shows the time course of benzamil effects, and four parts of the trace (1–4) are extended to show the channel activity at a faster time resolution.

Figure 4.

The effect of 1 μM benzamil on intracellular Na+ concentration.

Since EIPA failed to mimic the effect of amiloride, the role of intracellular pH in mediating cross talk in the CCD is largely excluded. It is also unlikely that ATP is involved in mediating the effect since the basolateral K+ channels are not sensitive to ATP. To examine the role of Ca2+, we studied the effects of amiloride on the SK in a Ca2+-free bath solution and the results are summarized in Table I. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ abolished the effect of amiloride since channel activity was not significantly different from the control value (110 ± 10%), whereas amiloride reduced channel activity by 39 ± 5% in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 2 and Table I).

Table I.

The Effects of Amiloride (50 μM) on the Activity of the SK in the Presence or Absence of Extracellular Ca2+

| Ca2+ | zero Ca2+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPo (control) | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.85 ± 0.1 | ||

| NPo (amiloride) | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.93 ± 0.1 | ||

| Percentage of the control NPo | 61 ± 6 | 106 ± 10 | ||

| n | 10 | 5 |

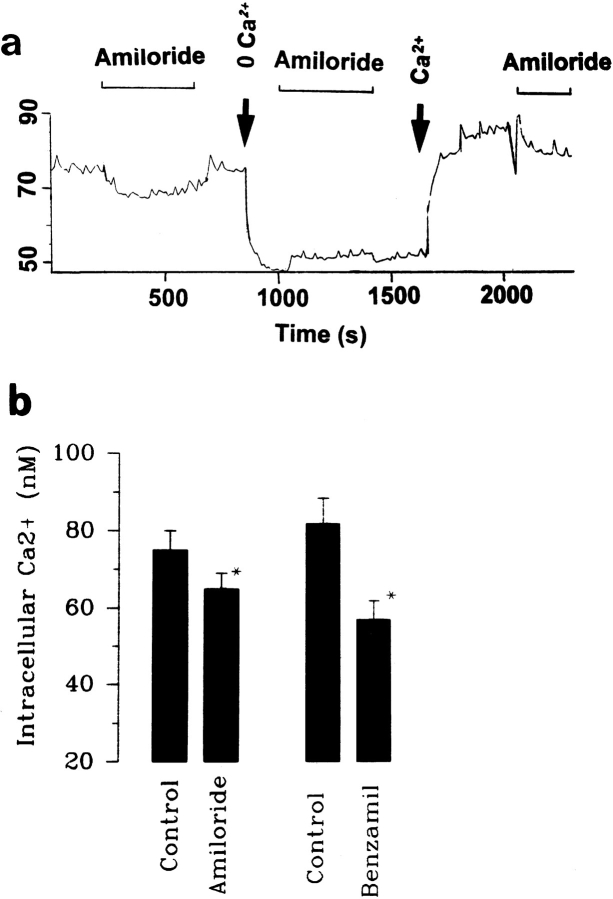

Schlatter et al. (1996) found that amiloride decreased intracellular Ca2+. We have also examined the effect of amiloride on the intracellular Ca2+ in the absence and presence of extracellular Ca2+. Fig. 5 a is one representative trace out of four experiments showing that addition of 0.5–1 μM amiloride significantly reduced intracellular Ca2+ from 75 ± 8 to 64 ± 5 nM. Also, Fig. 5 a shows that removal of extracellular Ca2+ significantly reduced intracellular Ca2+ to 45 ± 5 nM, and, moreover, amiloride had no significant effect on intracellular Ca2+ in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Although we observed only a modest (15%) decrease in the intracellular Ca2+ with 0.5–1 μM amiloride, a higher concentration of amiloride might result in a larger decrease. However, we were unable to use amiloride at higher concentrations since fluorescence emitted by amiloride at high concentrations interfered with the measurement. That the amiloride-induced small decrease in intracellular Ca2+ is due to incompletely inhibiting Na+ channels is supported by experiments in which adding 1 μM benzamil reduced intracellular Ca2+ by 30% from 82 ± 7 to 57 ± 6 nM (Fig. 5 b). The observation is consistent with the results reported by Frindt et al. (1993).

Figure 5.

(a) The effect of amiloride (0.5 μM) on intracellular Ca2+ in the presence and absence of 1.8 mM Ca2+. The arrows indicate removal of extracellular Ca2+ (0 Ca2+) and addition of 1.8 mM Ca2+ (Ca2+). (b) The effect of amiloride (0.5–1 μM) and benzamil (1 μM) on intracellular Ca2+ (n = 4).

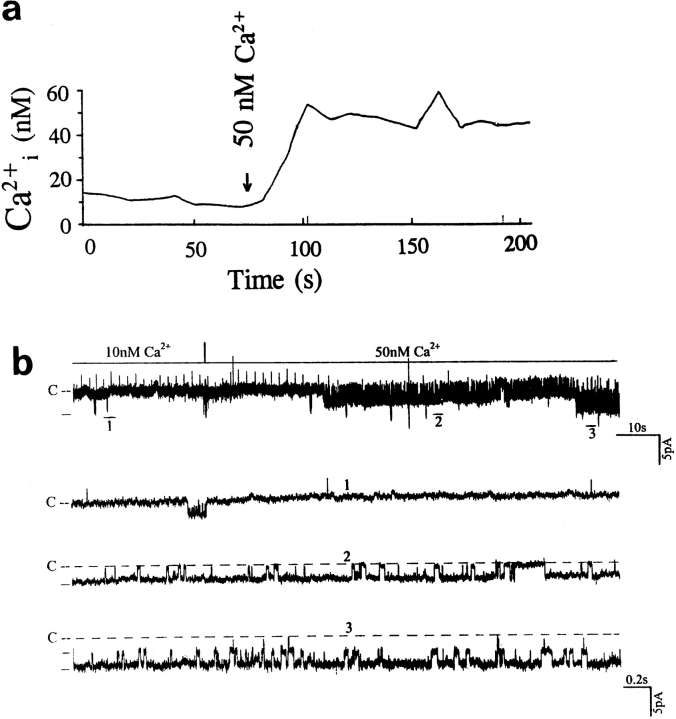

Data supporting the notion that the decrease in intracellular Ca2+ is responsible for the effects of inhibiting Na+ transport on the SK were obtained from experiments in which the effects of Ca2+ on the SK were investigated. We used 1 μM ionomycin to clamp the intracellular Ca2+. Fig. 6 a is a representative recording showing the changes in intracellular Ca2+ in the presence of 1 μM ionomycin when the extracellular Ca2+ increased from 10 to 50 nM. Fig. 6 b is a representative recording showing the effect of raising Ca2+ on channel activity in a cell-attached patch. It is apparent that the increase in intracellular Ca2+ to 50 nM significantly stimulates the SK. Fig. 7 shows a relationship between the channel activity and intracellular Ca2+ obtained from eight experiments. Raising intracellular Ca2+ to 50 and 100 nM increases the nP o (0.9 ± 0.3, control value) by 105 ± 11 and 190 ± 15%, respectively. Thus, data strongly indicate that a decrease in intracellular Ca2+ is responsible for the effect of inhibiting Na+ transport.

Figure 6.

(a) Changes in intracellular Ca2+ when extracellular Ca2+ was raised from 10 to 50 nM in the presence of 1 μM ionomycin. (b) Recording demonstrating the effect of raising intracellular Ca2+ from 10 to 50 nM. The intracellular Ca2+ was clamped with 1 μM ionomycin and the free Ca2+ concentration in the bath was titrated to 10 or 50 nM with 1 mM EGTA. The channel closed level is indicated by C and the pipette holding potential is −30 mV. The time course of the effect of Ca2+ is shown in the top panel. Three parts of the trace (1–3) are extended to show the channel activity at faster time resolution.

Figure 7.

The effect of intracellular Ca2+ on the activity of the SK. nP o obtained in the presence of 10 nM Ca2+ is defined as the control value. *Data are significantly different from the control value. Ionomycin (1 μM) was used to clamp intracellular Ca2+ to 10, 50, and 100 nM (n = 8).

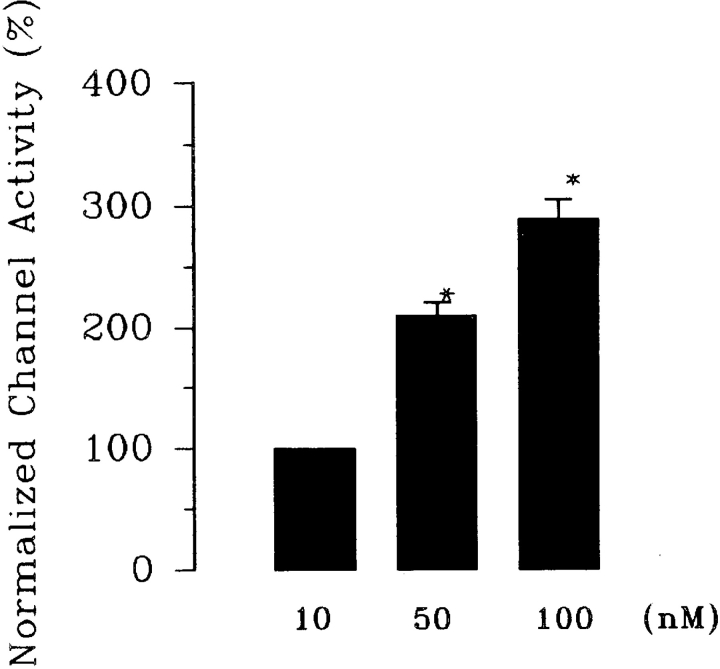

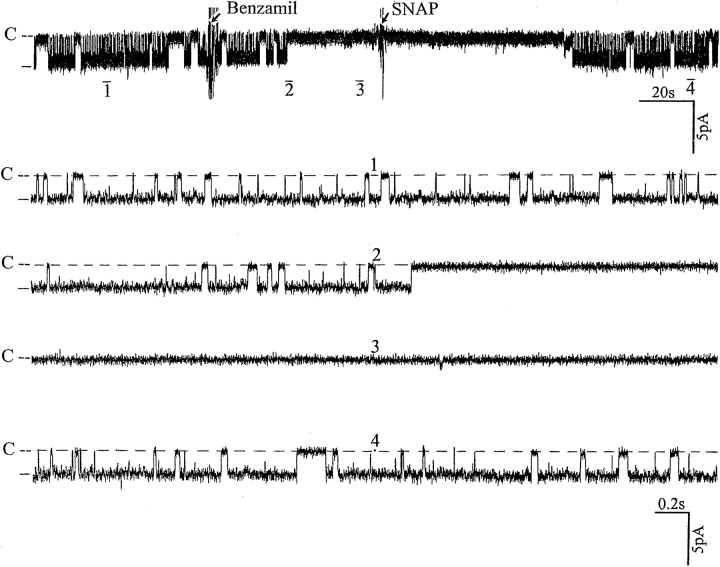

Having proposed that Ca2+ is involved in mediating the effect of inhibiting Na+ channels on the SK, we explored the mechanism by which intracellular Ca2+ modulates channel activity. The effect of Ca2+ is not direct since in excised patches we did not find significant changes in channel activity when the Ca2+ concentration was increased from 0 to 100 nM (data not shown). Moreover, an increase in Ca2+ to 1 μM inhibited the SK and led to channel run-down in excised patches (data not shown). Thus, our data strongly suggest that the effect of Ca2+ is indirect and mediated by a Ca2+-dependent pathway. Our previous study had demonstrated that NO stimulated the SK via a cGMP-dependent pathway (Lu and Wang, 1996), and we recently found that neuronal NOS (nNOS) is expressed in the CCD (Wang et al., 1997). Since nNOS activity has been shown to depend critically on intracellular Ca2+ in the physiological range of Ca2+ concentration (50–250 nM) (Knowles et al., 1989), we examined the possible role of NO in mediating the effect of inhibiting apical Na+ transport. Fig. 8 shows the effect of SNAP, a NO donor, on channel activity that had been decreased by benzamil. It is apparent that addition of 10 μM SNAP reversed the benzamil-induced decrease of the channel activity.

Figure 8.

A recording from a cell-attached patch showing the effect of 10 μM SNAP on benzamil-induced effects. The pipette holding potential was −30 mV. (C) The channel closed level. (top) Time course of the experiments and four parts of the trace (1–4) are displayed at faster time resolution.

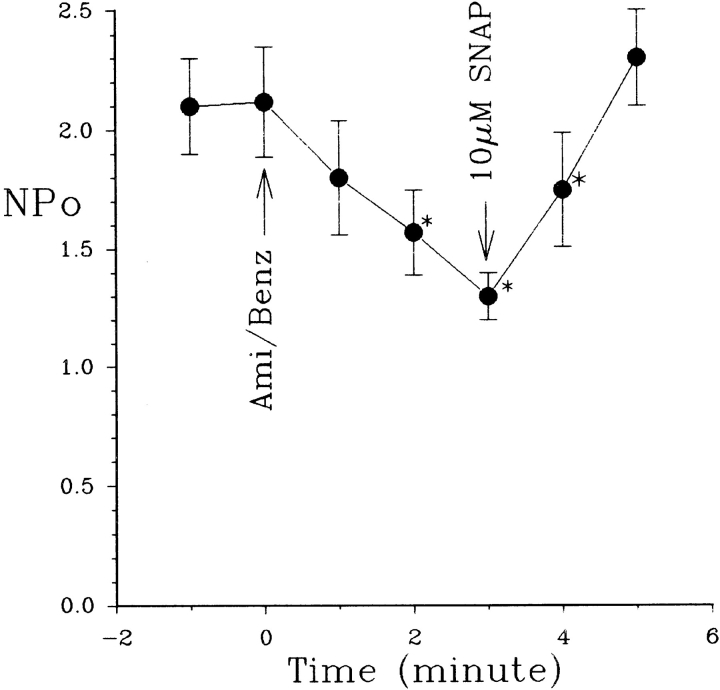

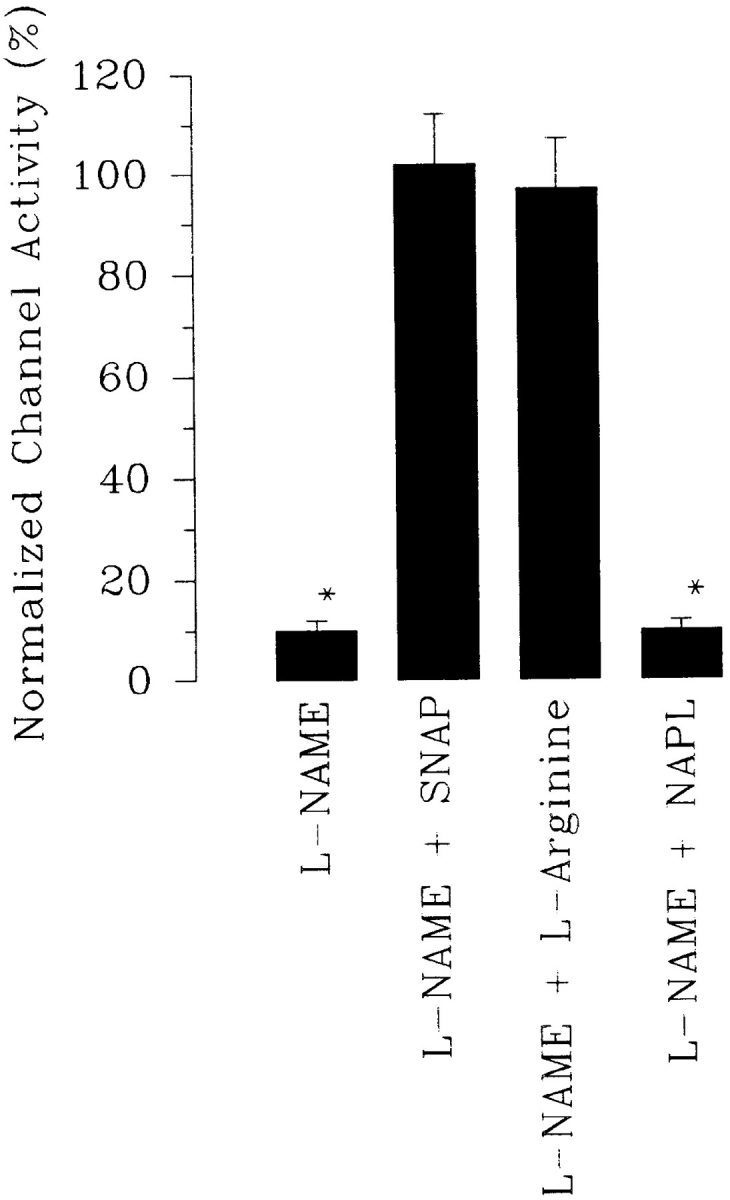

Fig. 9 summarizes the effect of SNAP on SK in the presence of either 50 μM amiloride or 1 μM benzamil. Both decreased channel activity (nP o) from 2.1 ± 0.2 to 1.3 ± 0.1 (n = 12); however, application of SNAP restored channel activity (nP o) to 2.25 ± 0.25 (n = 12), suggesting that the decrease in NO production may be responsible for the effect of inhibiting Na+ channels. We have previously shown that addition of 100 μM L-NAME (l-N G-nitroarginine methyl ester) blocked the SK channel (Lu and Wang, 1996). We have further extended our study to examine the effect of L-NAME in the presence of L-arginine. Fig. 10 summarizes the results from such experiments, showing that application of 400 μM L-arginine abolished the effect of L-NAME. In addition, the effect of L-NAME can be reversed by 10 μM SNAP but not by N-acetyl-penicillamine (10 μM), the byproduct of SNAP, suggesting that the effect of SNAP results from NO release.

Figure 9.

The effects of 50 μM amiloride/1 μM benzamil on the SK in the absence and presence of 10 μM SNAP. *Data are significantly different from the control value. 50 μM amiloride or 1 μM benzamil was added to the bath at time 0 (arrow).

Figure 10.

Effects on the activity of the SK channel of L-NAME (100 μM) (n = 10), L-NAME + L-arginine (400 μM) (n = 5), L-NAME + SNAP (10 μM) (n = 10), and L-NAME + 10 μM N-acetyl-penicillamine (NAPL) (n = 5). Experiments were carried out in cell-attached patches.

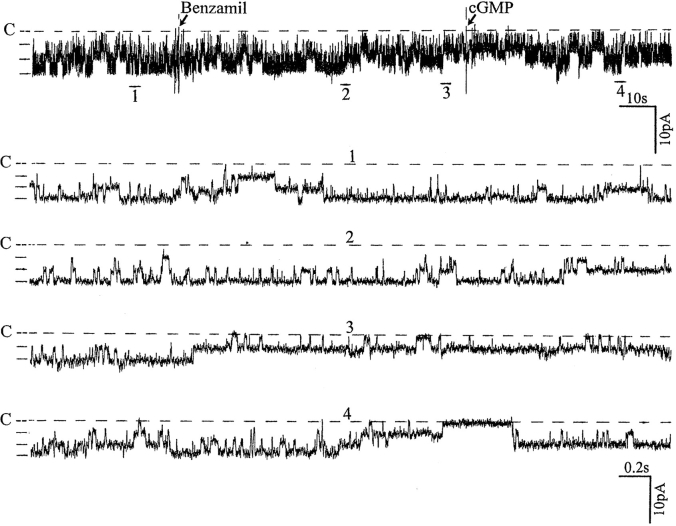

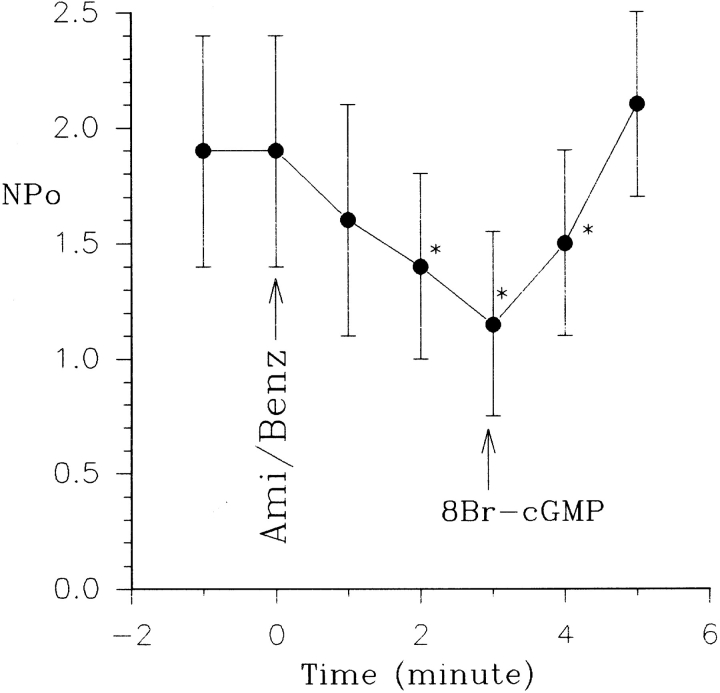

Since cGMP has been shown to mimic the effect of NO donors such as SNAP, we next investigated whether cGMP can reverse the effect of inhibiting apical Na+ transport. Fig. 11 shows that addition of 100 μM 8Br-cGMP mimicked the effect of SNAP and reactivated the SK in cell-attached patches in the presence of benzamil. Fig. 12 summarizes these results, showing inhibition of the Na+ channel–reduced nP o of the SK from 1.9 ± 0.4 to 1.2 ± 0.3 (n = 5), whereas addition of 100 μM cGMP restored channel activity (nP o = 2.0 ± 0.4). Moreover, the effect of cGMP and SNAP is not additive (data not shown), further supporting the notion that cGMP mediates the effect of NO.

Figure 11.

A recording from a cell-attached patch showing the effect of 100 μM 8Br-cGMP on benzamil-induced effects. The pipette holding potential is −30 mV and the channel closed level is indicated by C and a dotted line. (top) Time course of the experiments and four parts of the trace (1–4) are displayed at a faster time resolution.

Figure 12.

The effects of 50 μM amiloride/1 μM benzamil on the SK in the absence and presence of 100 μM 8Br-cGMP. *Data are significantly different from the control value. 50 μM amiloride or 1 μM benzamil were added to the bath at time of 0 s (arrow).

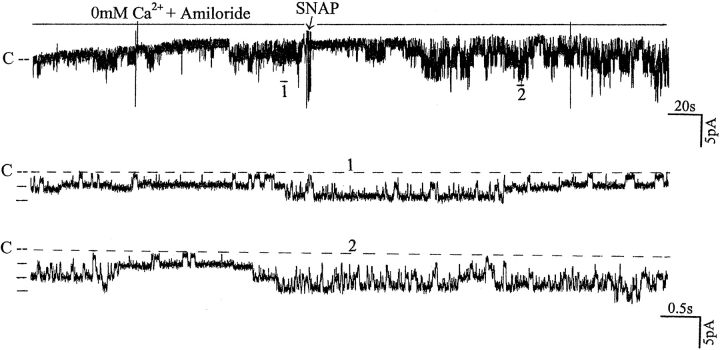

The notion that NO may be involved in mediating the effects of inhibition of the Na+ channel is further supported by experiments in which addition of SNAP stimulated channel activity in the Ca2+-free bath solution (Fig. 13). Application of 10 μM SNAP caused a significant increase in channel activity (nP o) from 0.5 ± 0.1 to 1.1 ± 0.2, suggesting that diminished NO formation associated with the decrease in intracellular Ca2+ is responsible for the effect of inhibiting Na+ channels.

Figure 13.

Recording showing the effects of 10 μM SNAP on the activity of the SK in a cell-attached patch. The bath solution contained 50 μM amiloride and zero free Ca2+. The arrow indicates the addition of SNAP. The top trace shows the channel activity at a slow time course and two parts of the trace are extended to display the details of the channel activity. The channel closed level is indicated by C and a dotted line. The pipette holding potential was −30 mV.

discussion

Three types of K+ channels have been found in the basolateral membrane of the rat CCD (Wang et al., 1994; Hirsch and Schlatter, 1993) and we confirmed previous observations that in rats on either normal or high potassium diet the SK is predominant in the lateral membrane of the CCD. Accordingly, the SK plays an important role in determination of cell membrane potential. We have previously shown that NO stimulates the SK channel via a cGMP-dependent pathway (Lu and Wang, 1996). This finding is further confirmed by results in experiments in which the effect of L-NAME was abolished in the presence of L-arginine, suggesting that the effect of L-NAME is the result of competing for NOS with the endogenous L-arginine in the CCD.

In the present study, we examined the effect of inhibiting Na+ transport on the SK to gain an insight into the mechanism by which apical Na+ transport is linked to the basolateral K+ conductance. Since it has been observed that cGMP stimulates basolateral K+ channels other than the SK (Hirsch and Schlatter, 1995), it is conceivable that the SK is not the only K+ channel that is involved in the cross-talk mechanism.

The present study confirms other investigators' findings that the transepithelial Na+ transport is coupled to the basolateral K+ conductance (Horisberger and Giebisch, 1988a , 1988b ; Harvey, 1995; Beck et al., 1993; Tsuchiya et al., 1992). The cross-talk mechanism by which the apical Na+ transport links to the basolateral K+ channel has been extensively explored and changes in intracellular ATP, pH, and Ca2+ have been suggested to be involved (Beck et al., 1993; Harvey, 1995; Schlatter et al., 1996; Tsuchiya et al., 1992). ATP has been shown to play a key role in linking apical Na+ transport to the basolateral ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the proximal tubule cells of rabbit and rat kidneys (Tsuchiya et al., 1992; Hurst et al., 1991; Beck et al., 1993), and in the principal cells of amphibian tight epithelial cells (Urbach et al., 1996b ). However, since the basolateral K+ channel in the CCD is not sensitive to ATP, a role of ATP in linking apical Na+ transport to basolateral K+ conductance is largely excluded.

Intracellular pH has been demonstrated to play an important role in mediating the aldosterone-induced stimulation of basolateral K+ conductance in amphibian distal nephron cells (Urbach et al., 1996a ; Wang et al., 1989). Application of aldosterone to stimulate the Na+ transport induces a significant alkalinization of intracellular pH and, accordingly, increases the basolateral pH-sensitive K+ conductance in the frog distal nephron. Although the basolateral K+ channels are pH sensitive, several lines of evidence indicate that the effect of amiloride is not the result of decreasing intracellular pH. First, EIPA, which selectively inhibits the Na/H exchanger but not Na+ channels, has no effect on the basolateral K+ channels. Second, benzamil, which is a specific Na+ channel blocker, reduces the activity of the SK. We also confirmed observations of Schlatter et al. (1996) that inhibition of Na+ transport significantly reduced intracellular Na+ concentration. Finally, the effect of amiloride on the SK is abolished in a Ca2+-free bath solution, further suggesting that intracellular pH is not involved in mediating the effect of amiloride. In addition, Frindt et al. (1993) have shown that application of 10 μM amiloride has no effect on intracellular pH. Thus, it is unlikely that intracellular pH plays a significant role in mediating the effect of inhibiting the Na+ channels.

Three lines of evidence strongly suggest that Ca2+ is critically involved in mediating the effect on the SK of inhibition of the Na+ channels: first, the effect is correlated with a decrease in intracellular Ca2+; second, removal of Ca2+ abolishes the effect; and third, raising intracellular Ca2+ from 10 to 50 and 100 nM stimulates the SK. The amiloride-induced reduction of intracellular Ca2+ is presumably the result of an increase in the electrochemical gradient of Na+ that drives the Na/Ca exchanger. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ not only abolishes the Ca2+ influx, but also facilitates the extrusion of Ca2+ along its electrochemical gradient.

Although the present data indicate that the effect of inhibiting the Na+ channels on the activity of the SK is related to the decline of intracellular Ca2+, the effect of Ca2+ on the SK is not a direct action since Ca2+-induced increases in channel activity were absent in excised patches (data not shown). Moreover, the effect of raising Ca2+ from 10 to 100 nM is absent in the presence of 100 μM L-NAME (our unpublished observations), suggesting that the effect of Ca2+ is related to NO formation. Several lines of evidence suggest that NO could be responsible for mediating the effect of inhibiting Na+ transport. The constitutive form of NOS has been shown to be present in the kidney, including the CCD (Terada et al., 1992), and we have confirmed this using the reverse transcription–PCR and immunocytochemical methods (Wang et al., 1997). It is well established that the activity of nNOS dependents on Ca2+ in the physiological ranges (50–250 nM) and a decrease in Ca2+ significantly reduces the activity of nNOS (Knowles et al., 1989). NO has been found to stimulate the activity of the SK by a cGMP-dependent pathway (Lu and Wang, 1996), and addition of NO donors or cGMP reversed the effect of inhibiting Na+ channels. Finally, NO donors mimic the effect of raising extracellular Ca2+ and increase the activity of the SK in a Ca2+-free bath. Taken together, these data suggest that inhibition of Na+ channels leads to reduction of intracellular Ca2+, which in turn decreases NO formation and inhibits basolateral K+ channels.

Ca2+ has also been found to play a key role in linking the apical K+ conductance (Wang et al., 1993) and Na+ transport to the activity of Na-K-ATPase (Frindt et al., 1996; Silver et al., 1993; Ling and Eaton, 1989). Inhibition of Na-K-ATPase decreased the open probability of the apical K+ channel in the CCD, and the effect of inhibiting the Na-K-ATPase was mediated by Ca2+-dependent PKC (Wang et al., 1993). Inhibition of the Na-K-ATPase has also been shown to decrease the basolateral K+ transference number, an index of the basolateral K+ permeability (Schlatter and Schafer, 1987). This effect is believed to be mediated by raising intracellular Ca2+ (Schlatter et al., 1996). In the present study, we show that a decrease in intracellular Ca2+ leads to a decline in the activity of the basolateral K+ channels. Therefore, it is conceivable that the intracellular Ca2+ may have biphasic effects on basolateral K+ conductance. At a low concentration, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ activates the basolateral K+ conductance by stimulating the cGMP pathway. On the other hand, at a high concentration, intracellular Ca2+ may inhibit the basolateral K+ channels. Further experiments are needed to determine the precise relationship between intracellular Ca2+ and basolateral K+ channel activity.

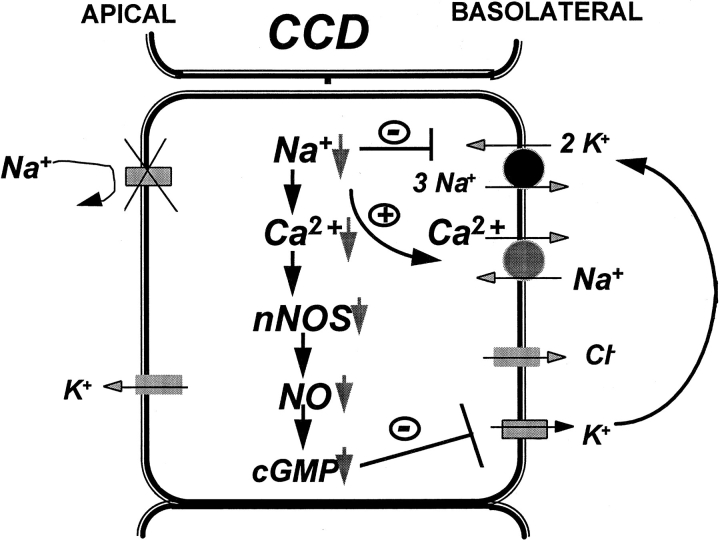

Fig. 14 is a cell model to illustrate the mechanism by which inhibition of apical Na+ channels reduces the activity of the SK. The blockade of the Na+ channels by amiloride/benzamil decreases intracellular Na+ concentration and reduces the turnover rate of the Na-K-ATPase since the activity of the Na-K-ATPase has been shown to be coupled to apical Na+ transport (Flemmer et al., 1993). Such a decrease in intracellular Na+ increases the electrochemical driving force for Ca2+/Na+ exchange and enhances the extrusion of intracellular Ca2+ from the cell. Since the activity of nNOS is Ca2+ dependent, a decrease in intracellular Ca2+ is expected to inhibit nNOS and reduce the formation of NO and cGMP. As a consequence, the activity of the basolateral small conductance K+ channels decreases.

Figure 14.

A model of a principal tubule cell in the CCD illustrating the mechanisms by which inhibition of the apical Na+ transport reduces the basolateral K+ channel activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R.W. Berliner for help in preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK-17433 (G. Giebisch), DK-47402, and HL-34300 (W.H. Wang).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: CCD, cortical collecting duct; SK, small-conductance K+ channel.

references

- Beck JS, Hurst AM, Lapointe JY, Laprade R. Regulation of basolateral K channels in proximal tubule studied during continuous microperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F496–F501. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.3.F496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyer MD, Ando Y. Hormonal signaling and regulation of salt and water transport in the collecting duct. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:711–739. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis W, Finn AL. Sodium transport inhibition by amiloride reduces basolateral membrane K conductance in tight epithelia. Science. 1982;26:525–527. doi: 10.1126/science.7071599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DC, Richards NW. Basolateral K conductance: role in regulation of NaCl absorption and secretion. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C181–C195. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.2.C181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemmer A, Doerge A, Thurau K, Beck FX. Transcellular sodium transport and basolateral rubidium uptake in the isolated perfused cortical collecting duct. Pflügers Arch. 1993;424:250–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00384350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frindt G, Silver RB, Windhager EE, Palmer LG. Feedback regulation of Na channels in rat CCT. II. Effects of inhibition of Na entry. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F565–F574. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.3.F565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frindt G, Palmer LG, Windhager EE. Feedback regulation of Na channels in rat CCT. IV. Mediation by activation of protein kinase C. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:F371–F376. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.2.F371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebisch G. Renal potassium channels: an overview. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1004–1009. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Ponie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Cragoe EJ, Deth RC. Influence of atrial natriuretic factor on 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride-sensitive 22Na uptake in rabbit aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248:991–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey BJ. Cross-talk between sodium and potassium channels in tight epithelia. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1191–1199. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch J, Schlatter E. K+channels in the basolateral membrane of rat cortical colleting duct. Pflügers Arch. 1993;424:470–477. doi: 10.1007/BF00374910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch J, Schlatter E. K+channels in the basolateral membrane of rat cortical collecting duct are regulated by a cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Pflügers Arch. 1995;429:338–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00374148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horisberger JD, Giebisch G. Intracellular Na+ and K+activities and membrane conductances in the collecting tubule of Amphiuma. J Gen Physiol. 1988a;92:643–665. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horisberger JD, Giebisch G. Voltage dependence of the basolateral membrane conductance in the amphiuma collecting tubule. J Membr Biol. 1988b;105:257–263. doi: 10.1007/BF01871002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst AM, Beck JS, Laprade R, Lapointe JY. Na+ pump inhibition downregulates an ATP-sensitive K+channel in rabbit proximal convoluted tubule. Am J Physiol. 1991;264:F760–F764. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.4.F760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleyman TR, Cragoe EJ., Jr Amiloride and its analogs as tools in the study of ion transport. J Membr Biol. 1988;105:1–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01871102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles RG, Palacios M, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Formation of nitric oxide from L-arginine in the central nervous system: a transduction mechanism for stimulation of the soluble guanylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5159–5162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling BN, Eaton DC. Effects of luminal Na+on single Na channels in A6 cells, a regulatory role for protein kinase C. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:F1094–F1103. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.6.F1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Wang WH. Nitric oxide regulates the low-conductance K channel in the basolateral membrane of the cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C1338–C1342. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.5.C1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG, Antonian L, Frindt G. Regulation of the Na-K pump of the rat cortical collecting tubule by aldosterone. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:43–57. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JA, Hawk CT. Regulation of Na+channels in the cortical collecting duct by AVP and mineralocorticoids. Kidney Int. 1992;41:255–268. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JA, Troutman SL. Potassium transport in cortical collecting tubules from mineralcorticoid-treated rat. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:F76–F88. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.253.1.F76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlatter E, Haxelmans S, Ankorina I. Correlation between intracellular activities of Ca2+ and Na+ in rat cortical collecting duct—a possible coupling mechanism between Na+-K+-ATPase and basolateral K conductance. Kidney Blood Press Res. 1996;19:24–31. doi: 10.1159/000174042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlatter E, Schafer JA. Electrophysiological studies in principal cells of rat cortical collecting tubules. ADH increases the apical membrane Na+-conductance. Pflügers Arch. 1987;409:81–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00584753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz SG. Homocellular regulatory mechanisms in sodium-transporting epithelia: avoidance of extinction by “flush-through.” . Am J Physiol. 1981;241:F579–F590. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.241.6.F579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RB, Frindt G, Windhager EE, Palmer LG. Feedback regulation of Na channels in rat CCT. I. Effects of inhibition of Na pump. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F557–F564. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.3.F557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PR, Benos DJ. Epithelial Na channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 1991;53:509–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieter J, Stephenson JL, Giebisch G, Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of the rabbit cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol. 1992a;263:F1063–F1075. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.6.F1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieter J, Weinstein AM, Giebisch G, Stephenson J. Regulation of K transport in a mathematical model of the cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol. 1992b;263:F1076–F1086. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.6.F1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y, Tomta K, Nonoguchi H, Marumo F. Polymerase chain reaction localization of constitutive nitric oxide synthase and soluble guanylate cyclase messenger RNAs in microdissected rat nephron segments. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:659–665. doi: 10.1172/JCI115908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya K, Wang WH, Giebisch G, Welling PA. ATP is a coupling-modulator of parallel Na/K ATPase-K channel activity in the renal proximal tubule. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6418–6422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach V, Kerkhove EV, Maguire D, Harvey BJ. Rapid activation of KATPchannels by aldosterone in principal cells of frog skin. J Physiol (Camb) 1996a;491:111–120. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach V, Kerkhove EV, Maguire D, Harvey BJ. Cross-talk between ATP-regulated K+ channels and Na+transport via cellular metabolism in frog skin principal cells. J Physiol (Camb) 1996b;491:99–109. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WH, Henderson RM, Geibel J, White S, Giebisch G. Mechanism of aldosterone-induced increase of K conductance in early distal renal tubule cells of the frog. J Membr Biol. 1989;111:277–289. doi: 10.1007/BF01871012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WH, Geibel J, Giebisch G. Mechanism of apical K channel modulation in principal renal tubule cells: effect of inhibition of basolateral Na-K-ATPase. J Gen Physiol. 1993;101:673–694. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.5.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WH, McNicholas CM, Segal AS, Giebisch G. A novel approach allows identification of K+channels in the lateral membrane of rat CCD. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:F813–F822. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.5.F813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WH. Regulation of the hyperpolarization-activated K channel in the lateral membrane of the CCD. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:25–43. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XH, Lu M, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa W, Wang WH. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase is expressed in the cortical collecting duct (CCD) of the rat kidney. FASEB (Fed Am Soc Exp Biol) J. 1997;11:A551. . (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]