Abstract

The Bacillus halodurans voltage-gated sodium-selective channel (NaChBac) (Ren, D., B. Navarro, H. Xu, L. Yue, Q. Shi, and D.E. Clapham. 2001b. Science. 294:2372–2375), is an ideal candidate for high resolution structural studies because it can be expressed in mammalian cells and its functional properties studied in detail. It has the added advantage of being a single six transmembrane (6TM) orthologue of a single repeat of mammalian voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV) and Na+ (NaV) channels. Here we report that six amino acids in the pore domain (LESWAS) participate in the selectivity filter. Replacing the amino acid residues adjacent to glutamatic acid (E) by a negatively charged aspartate (D; LEDWAS) converted the Na+-selective NaChBac to a Ca2+- and Na+-permeant channel. When additional aspartates were incorporated (LDDWAD), the mutant channel resulted in a highly expressing voltage-gated Ca2+-selective conductance.

Keywords: bacterial channels, calcium channels, sodium channels, ion/membrane channel

INTRODUCTION

Multicellular organisms rely on voltage-dependent Na+ and Ca2+-selective ion channels for rapid signal transduction and initiation of cellular events such as neurosecretion or muscle contraction. Over the last two decades, electrophysiology and molecular biology have effectively revealed the general structure-function relationships of these channels.

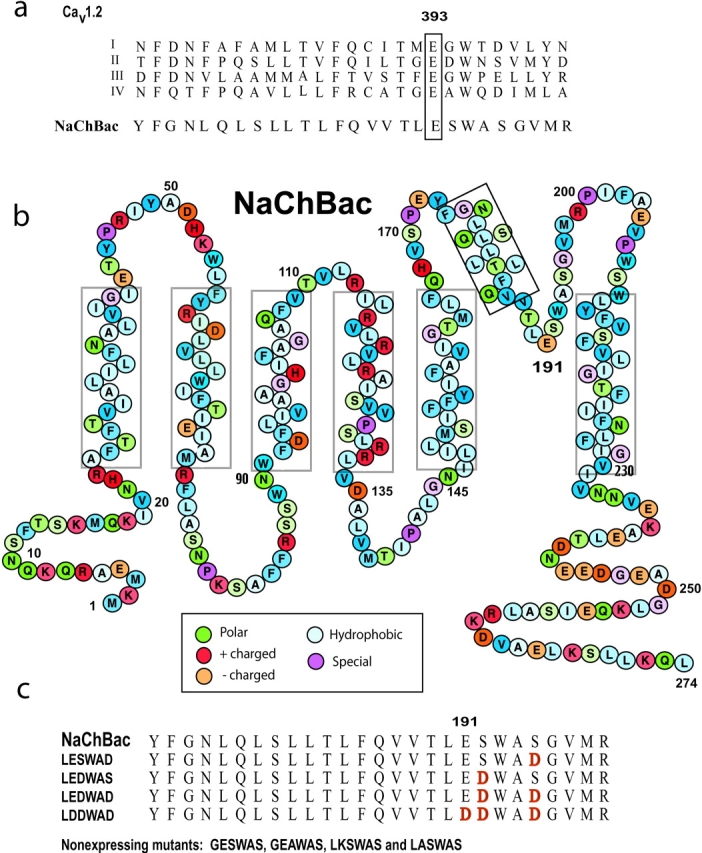

We recently described the expression of a six transmembrane (6TM)* domain voltage-gated sodium channel gene (NaChBac) from Bacillus halodurans (Ren et al., 2001b). The primary structure of NaChBac is similar to that of a mammalian 6TM putative voltage-gated cation channel CatSper (Ren et al., 2001a) and the pore structure of NaChBac is similar to that of voltage-gated CaVs (Durell and Guy, 2001). In particular, NaChBac contains the signature FxxxTxExW sequence of CaV in the pore segments, and the conserved glutamate (E) residues (Ren et al., 2001b) that are essential for Ca2+ selectivity (Fig. 1) (Elliott et al., 1995). However, NaChBac encoded a voltage-gated channel that was Na+ selective. Also, INaChBac kinetics, including activation, inactivation, and recovery from inactivation, were 10–100 times slower than that of Nav.

Figure 1.

Structure of NaChBac and alignment of amino acid sequences of the P loops of CaV and NaChBac. (A) Alignment of the putative pore region of NaChBac with that of the four domains (I–IV) of CaV1.2 channel. The numbers correspond to residues in the P loop of CaV1.2 domain I. Residues in the EEEE selectivity filter motif are boxed. (B) NaChBac contains 274 amino acid residues, here color-coded according to their properties. (C) Alignment of the putative pore region of NaChBac and NaChBac mutants. Residues in red refer to relevant mutation sites.

Voltage-gated Na+-selective (Nav) and Ca2+-selective (Cav) 24TM channels contain four similar repeats (domains D1–D4) of six (S1–S6) segments. Like single repeat 6TM channels, the pore loop joins the S5-S6 segments and determines the selectivity of cation permeation. Unlike K+ channels in which main chain carbonyls create the selectivity filter (Doyle et al., 1998), Cav and Nav channel amino acid side chains are postulated to form their selectivity filters (Heinemann et al., 1992; Ellinor et al., 1995; Favre et al., 1996; Armstrong and Hille, 1998; Penzotti et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2000). Soon after the functional expression of the first NaV channel in 1986 (Noda et al., 1986), several groups attempted to express single repeats of the NaV channel in hopes that they might form functional homomers of the 6TM domain. These attempts did not yield functional channels (although recently, ionophore activity has been reported from a ligated S5-P-S6 segment of a rat skeletal NaV [Chen et al., 2002]).

Nonetheless, the identification of the important residues in the selectivity filter in NaV was soon established. Substitution of lysine (K) and alanine (A) within the DEKA [aspartate (D), glutamate (E), lysine (K) and alanine (A)] locus decreased Na+ selectivity and allowed channels to permeate Ca2+ (Heinemann et al., 1992). Replacement of lysine (K; D3) or alanine (A; D4) by glutamate (E; D3, D4) (Heinemann et al., 1992), or lysine (K; D3) by alanine (A; D3)(Sun et al., 1997) altered the ion selectivity of NaV to more closely resemble that of CaV channels. Biophysical studies on CaV channels had suggested that the channel contained one or two Ca2+ binding sites (Hess and Tsien, 1984; Hess et al., 1986; Ellinor et al., 1995; McCleskey, 1999). The CaV channel selectivity filter was proposed to contain one glutamate (E) residue from each of the four domains drawn into a circle around the pore EEEE motif (Heinemann et al., 1992; Yang et al., 1993; Ellinor et al., 1995). In comparison, the similarly placed residues in the four domains (DEKA motif) form a dynamic (Benitah et al., 1999), asymmetric (Benitah et al., 1997), and flexible (Perez-Garcia et al., 1997) ion selectivity filter in NaV channels.

Favre et al. (1996) provided evidence that the Lys (K) residue in D3 was the critical determinant that specified both the impermeability of Ca2+ and the selective permeability of Na+ over K+. Furthermore, substitution for lysine or an exchange of the positions of the lysine and glutamate residues (DEKA to DKEA) decreased Na+ selectivity (Chen et al., 1997; Perez-Garcia et al., 1997). Cysteine accessibility experiments revealed that the D2 pore loop is most superficial, D1 and D3 intermediate, and D4 most internal (Chiamvimonvat et al., 1996).

In parallel with the studies of NaV, similar mutagenesis studies focused on the CaV selectivity filter. Asp (D) and Ala (A) substitutions in the EEEE locus reduce ion selectivity by weakening ion binding affinity. Mutations within the set of glutamates (e.g., CaV1.2 EEEE changed to EEKA) effectively increased Na+ permeability by 15-fold (Tang et al., 1993). Substitution of the EEEE motif by AAAA, QQQQ, or DDDD motifs eliminated Ca2+ or Ba2+ currents (Ellinor et al., 1995; Cibulsky and Sather, 2000). In a mixture of ions, weakly binding ions are impermeant, strongly binding ions are permeant, and very strongly binding ions act as pore blockers (Cloues et al., 2000). Thus, competition among ion species is an intrinsic feature of the CaV selectivity filter.

To understand more about the Na+ and Ca2+ selectivity filters, we compared the relative permeabilities of expressed wild-type (wt) NaChBac with a series of mutants in which the pore residues had been altered. The short length of NaChBac (274 amino acids) and presumed homotetrameric assembly greatly simplifies the potential structure-function relationships.

Here we find that replacing the amino acid residues adjacent to glutamatic acid (E) by negatively charged aspartate (D) converted the Na+-selective NaChBac to a Ca2+-selective channel. We were also able to mutate pore residues within NaChBac that converted it into a nonselective ion channel.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of wt and Mutant NaChBac

NaChBac was cloned from Bacillus halodurans C-125 DNA by PCR (BAB05220) (Ren et al., 2001b). The NaChBac construct containing an open reading frame of 274 amino acid residues was subcloned into a pTracer-CMV2 vector (Invitrogen) containing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP). The skeletal muscle Na+ channel SKM1 (M26643) was used in comparison to NaChBac under identical recording conditions and determinations of permeability ratios. Mutations were introduced into the NaChBac cDNA by site-directed mutagenesis (QuickchangeTM site-directed mutagenesis kit; Stratagene). All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing and restriction digestion. wt NaChBac and mutant cDNAs were transfected into CHO-K1 cells or COS-7 cells with LipofectAMINE 2000 (Life Technologies). Transfected cells were identified by fluorescence microscopy and membrane currents were recorded 24–48 h after transfection.

Electrophysiology and Data Analysis

Unless otherwise stated, the pipette solution contained (in mM): 147 Cs, 120 methanesulfonate, 8 NaCl, 10 EGTA, 2 Mg2+-adenosine triphosphate, and 20 HEPES, pH 7.4. Bath solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 10 CaCl2, 5 KCl, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, and 10 glucose. For some experiments, NaCl was isotonically replaced by CaCl2.

For reversal potential measurements to determine the relative permeabilities of Na+ and Ca2+, the internal pipette solution contained (in mM): 100 mM Na-Gluconate, 10 NaCl, 10 EGTA, 20 HEPES-Na (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH, [Na+]total = 140). The external solution was (in mM): 140 NMDG-Cl, 10 CaCl2, 20 HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with HCl), or 80 NMDG-Cl, 50 CaCl2, and 20 HEPES. The fast kinetics and small current amplitude of SKM1 in 10 mM [Ca2+]o necessitated the use of 50 mM [Ca2+]o for accurate determination of Erev. The permeability ratio of Ca2+ was estimated according to the following equation:

|

where R, T, F, and Erev are the gas constant, absolute temperature, Faraday constant, and reversal potential, respectively, and x represents Cs+ or Na+ (i, internal; e, external) (Hille, 2001). For calculations of membrane permeability, activity coefficients for Ca2+, Cs+ and Na+ were estimated as follows:

|

where activity, as, is the effective concentration of an ion in solution, s related to the nominal concentration [Xs] by the activity coefficient, γs. γs was calculated from the Debye-Hückel equation:

|

where μ is the ionic strength of the solution, zs is the charge on the ion, and αs is the effective diameter of the hydrated ion in nanometers (nm). The calculated activity coefficients were γ(Cs)i = 0.70, γ(Ca)e = 0.331, γ(Na)i = 0.75 and γ(Na)e = 0.73. The liquid junction potentials were measured using a salt bridge as described by Neher (Neher, 1992) and these measurements agreed within 3 mV to those calculated by the JPCalc program (P. Barry) within Clampex (Axon Instruments, Inc.).

The voltage dependence of NaChBac and mutants channel activation was determined from a holding potential of −100 mV. Instantaneous tail current were measured at −100 mV after a test potential of 40 ms duration. Normalized tail current amplitude (I/Imax) was plotted versus test potentials and fitted with a Boltzmann function. Measurements of steady-state inactivation for NaChBac and mutants channel were resolved using 2-s prepulses and 1-s test pulse to −10, 0, or 10 mV depending on the mutant's peak voltage. Cells were held at −100 mV for 20 s between pulses to allow the recovery from inactivation. Normalized test current amplitude (I/Imax) was plotted versus prepulse potential and fitted with a Boltzmann function. The activation and steady-state inactivation curve were fitted by the Boltzmann equation:

|

where Imax and Imin are the maximum and minimum current values, V is the test voltage, V1/2 is the voltage activation midpoint, and k is the slope factor.

Whole-cell currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments, Inc.) amplifier. Data were digitized at 10 or 20 kHz, and digitally filtered off-line at 1 kHz. Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass and had resistances of 2–5 MΩ. All experiments were conducted at 22°C ± 2°C. For CHO cells, cell capacitance was 7.6 ± 0.3 pF and for COS-7 cells was 13.9 ± 0.6 pF. Mutant NaChBac current amplitudes ranged from ∼100–800 pA. For wt NaChBac, current amplitudes ranged from 800 pA to 2 nA. Series resistance (Rs) was compensated up to 90% to reduce all series resistance errors to <5 mV. Cells in which Rs was >10 mΩ were discarded. Pooled data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and two-tailed t test with Bonferroni correction; P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

The mutations of the NaChBac pore region described in this study are summarized in Fig. 1. The six relevant pore amino acids in NaChBac are LESWAS (residues 190–195), and mutants are specified with respect to this nomenclature.

Expression Levels of wt and Mutant NaChBac

The wt NaChBac currents and I-V curve were similar to those reported previously in CHO-K1 cells (Ren et al., 2001b), but four to six times larger in COS-7 cells (Fig. 2 A). Current densities of the LESWAD, LEDWAS, LDDWAD, and especially LEDWAD mutants were smaller than that of wt NaChBac (24–48 h after transfection). More than 98% of wt NaChBac-GFP–expressing cells had substantial currents, whereas only 30–50% LESWAD-, LEDWAS-, LEDWAD- or LDDWAD-GFP–transfected cells produced detectable currents. The LEGWAS mutant current was essentially the same as wt NaChBac. GESWAS, GEAWAS, LKSWAS, and LASWAS mutant currents were not measurable.

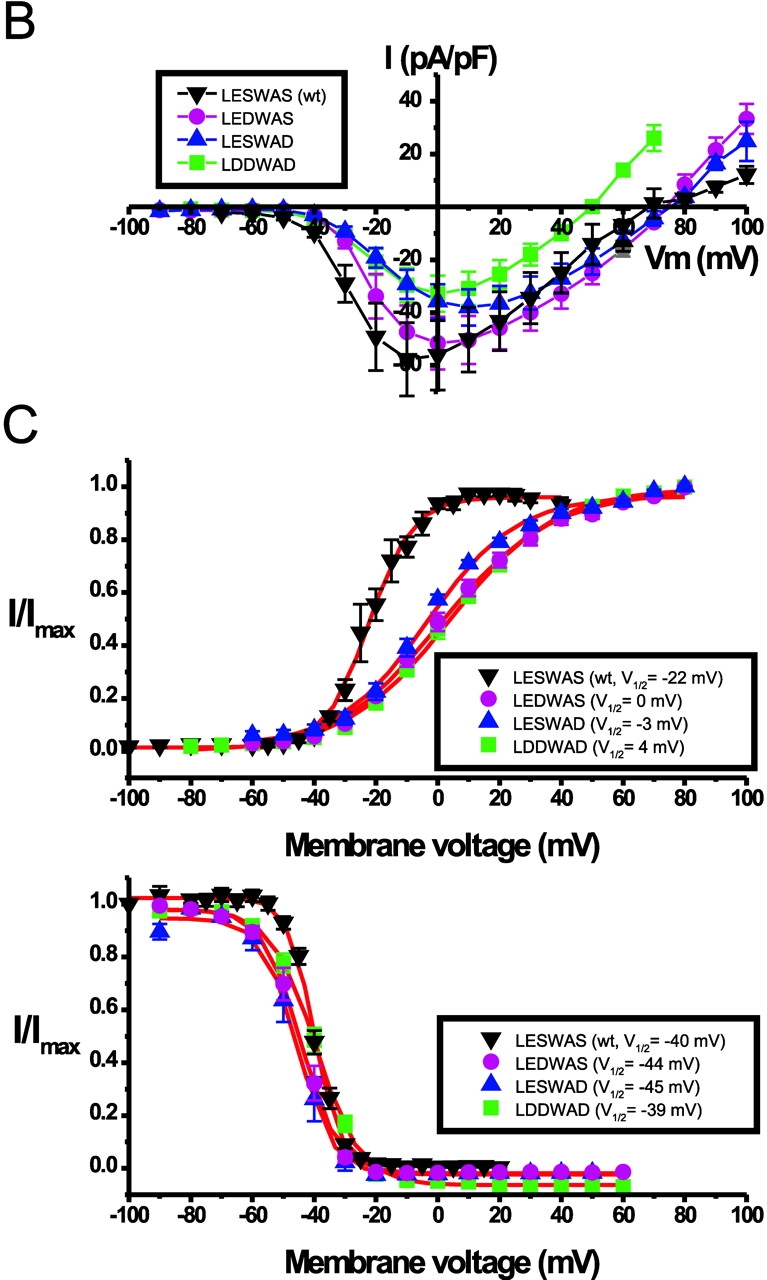

Figure 2.

Voltage dependence of wt NaChBac and NaChBac mutants. (A) Representative currents recorded in 10 mM Ca2+/140 Na+ modified Tyrode's solution (left) from NaChBac and mutant NaChBac with residues 190–195 as indicated. Voltage was stepped from VH = −100 to 100 mV in 10-mV increments at 15-s intervals. (B) Averaged I-V curves derived from currents recorded as in (A) of NaChBac and mutant NaChBac (n = 8–12 cells each). (C) Activation (top; VH = −100 mV) and steady-state inactivation (bottom; VH = −100 mV, pulse test to peak for 2 s) curves of NaChBac and mutant NaChBac (n = 7–12 cells each).

Kinetics of the NaChBac Mutant Channels

The averaged current density-voltage relations (I-V relations) are shown in Fig. 2 B. LEDWAS, LEDWAD, and LDDWAD mutant currents peaked at 0 mV, whereas the LESWAD mutant peaked at 10 mV. Fig. 2 C and Table I summarizes the activation, inactivation, and slope factor for the most interesting NaChBac mutants. The 50% steady-state inactivation (V1/2-inact) of LESWAD, LEDWAS, and LDDWAD were similar to those of wt NaChBac, whereas the midpoints of their activation curves were shifted 19, 22, and 26 mV, respectively, in the positive direction. The difference in the midpoint voltage (V1/2) and slope factor (k) activation of wt NaChBac and the mutants suggests that introduction of aspartate into the pore region altered the gating function of the channel. The activation and inactivation kinetics of these mutants are similar to that of wt NaChBac with the exception of the LESWAD mutant, which inactivated 2.7 times more rapidly than wt NaChBac (P < 0.05).

TABLE I.

Functional Parameters of NaChBac Pore Mutants

| τact | τinact | V1/2 act | V1/2 inact | kact | PCa/PNa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms | ms | mV | mV | mV/e-fold | ||

| SKM1 | 0.32 ± 0.07 (n = 8)e | |||||

| LESWAS(wt) | 12.9 ± 0.4a | 166.0 ± 13a | −22 | −40 | 7 | 0.15 ± 0.01 (n = 5)e |

| LESWAD | 6.7 ± 0.4b | 97.1 ± 5b | −3 | −45 | 14 | 17 ± 2.7 (n = 8)d |

| LEDWAS | 6.6 ± 0.5c | 191.1 ± 10c | 0 | −44 | 18 | 35 ± 7.4 (n = 7)d |

| LEDWAD | 73 ± 5.6 (n = 6)d | |||||

| LDDWAD | 8.3 ± 0.5c | 225.5 ± 7c | 4 | −39 | 17 | 133 ± 16.1 (n = 9)d

105 ± 18 (n = 9)e |

Membrane voltage is −10 mV.

Membrane voltage is 10 mV.

Membrane voltage is 0 mV.

Erev was measured under quasibiionic conditions and corrected for junction potential. The external solution for PCa/PNa was (in mM): 140 NMDG-Cl, 10 CaCl2, 20 HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with HCl). The internal solution was (in mM): 100 Na-Gluconate, 10 NaCl, 10 EGTA, 20 HEPES-Na (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH, [Na+]total = 140). The fast kinetics and small current amplitude of SKM1 in 10 mM [Ca2÷]o necessitated the use of 50 mM [Ca2+]o for accurate determination of Erev.

The external solution for PCa/PNa was (in mM): 80 NMDG-Cl, 50 CaCl2, 20 HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with HCl).

Selectivity of the NaChBac Mutant Channels

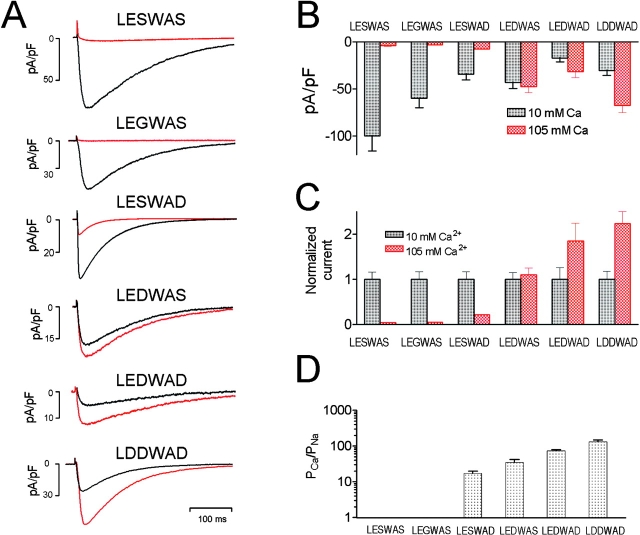

Reversal potentials of the NaChBac mutants were measured under quasi-biionic conditions as described in materials and methods. Fig. 3 A shows representative currents of wt NaChBac, LEGWAS, LEDWAS, LESWAD, LEDWAD, and LDDWAD mutants recorded in 10 mM Ca2+ (modified Tyrode's) solution and isotonic (105 mM) Ca2+ solution. NaChBac (wt) and LEGWAS currents were practically undetectable after replacement of the 140 mM Na+/10 mM Ca2+-containing solution by the 0 mM Na+/105 mM Ca2+ solution, indicating the low Ca2+ permeability of these channels. Current amplitudes of the LEDWAD and LDDWAD mutants were significantly increased when the external solution was changed to isotonic Ca2+ solution while the amplitude of LEDWAS mutant currents was not significantly increased. The LESWAD mutant current was dramatically decreased in isotonic [Ca2+]o. The average peak current amplitude measured at 0 mV obtained in 10 mM Ca2+ Tyrode's solution or in 105 mM Ca2+ solution is shown in Fig. 3 B and normalized to the current amplitude measured in 10 mM Ca2+ solution (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

Relative current amplitudes, current densities, and permeabilities of wt NaChBac and mutant NaChBac. (A) Original traces elicited by depolarizing from −100 to 0 mV in 10 mM Ca2+/140 Na+ solution (black) and in isotonic Ca2+ (105 mM) solution (red). (B) Averaged peak current densities of wt NaChBac and mutant NaChBac (n = 8). (C) Current amplitudes were normalized to the current amplitude in 10 mM Ca2+/140 Na+ solution (n = 8). (D) Relative permeabilities (PCa/PNa) of wt NaChBac and mutant NaChBac.

Relative permeability (PCa/PNa) was calculated as described in materials and methods and Table I. Since PCa/PNa had not been described for native Nav channels under these specific conditions, we also measured the relative permeability for SKM1, a skeletal muscle Na+-selective channel. SKM1 (Kraner et al., 1998) was expressed in COS7 and CHO cells and examined under identical conditions as NaChBac and similar to its mutants (Table I). For NaChBac, substitution of serine (192) by glycine (LEGWAS) did not change NaChBac's relative permeability (LESWAS: PCa/PNa = 0.15). Replacement of the serine at position 195 by aspartate (S195D; LESWAD) converted the normally Na+-selective wt NaChBac (PCa/PNa = 0.15) into a relatively nonselective cation channel (PCa/PNa = 17).

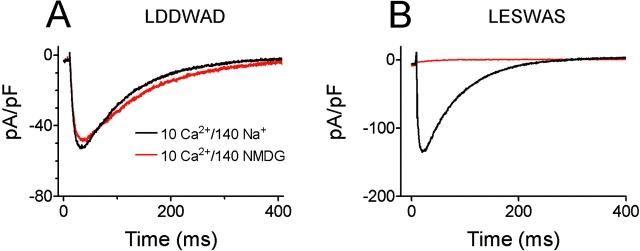

As uncharged amino acids were replaced by an increasing number of negatively charged aspartates, Ca2+ selectivity dramatically increased. Replacing the serine at position 192 by aspartate (S192D; LEDWAS) increased wt NaChBac's Ca2+ selectivity over Na+ by 233-fold (PCa/PNa= 35). Although the current amplitude was reduced, substitution of serines 192 and 195 by aspartate (LEDWAD) increased Ca2+ selectivity by 486-fold (PCa/PNa = 73). Further substitution by the negatively charged aspartate into position 195 (LDDWAD; denoted CaChBacm) yielded the highest Ca2+ permeability (PCa/PNa = 133), with a much larger current amplitude (500 to 1,000 pA) in 10 mM Ca2+ solution. As shown in Fig. 4 A, the current amplitude of CaChBacm in 10 mM Ca2+ solution was virtually identical to that obtained in 10 mM Ca2+/NMDG solution, suggesting that CaChBacm's conductance was not permeant to, nor affected by, [Na+]o. In comparison, the wt LESWAS current was almost undetectable in 10 mM Ca2+/NMDG solution (Fig. 4 B), consistent with it being a relatively selective Na+ channel.

Figure 4.

Currents of the Ca2+-selective CaChBacm (LDDWAD) mutant compared with wt NaChBac (LESWAS). (A) The current amplitude of the LDDWAD mutant recorded in 10 mM Ca2+/140 mM Na+ solution was not significantly different from that recorded in 10 mM Ca2+/140 mM NMDG solution. (B) The current amplitude of the wt NaChBac (LESWAS) was virtually eliminated by replacing 140 mM [Na]o by 140 mM [NMDG]o.

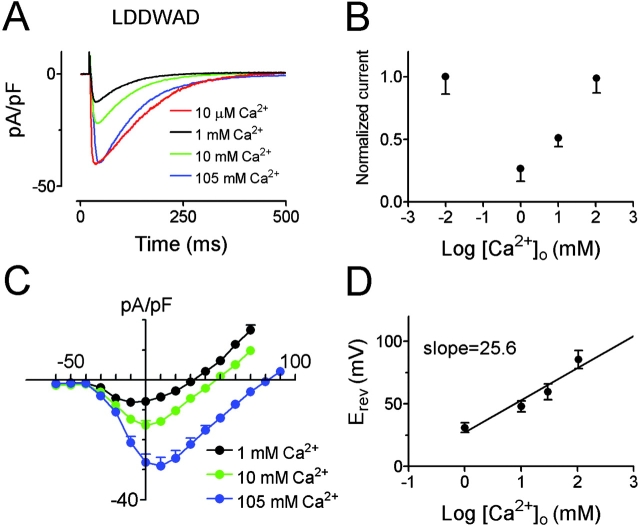

The Anomalous Mole Fraction Effect

Ca2+ -selective channels exhibit a concentration-dependent permeability ratio, called the anomalous mole fraction effect. This effect is thought to be a consequence of the Ca2+ channel's capacity to hold two or more divalent ions in the pore at the same time, and is usually interpreted to mean that ions interact within the pore. CaChBacm's (LDDWAD) conductance increased with increasing external [Ca2+]o and its conductance to Na+ increased when [Ca2+]o was decreased to 10 μM (Fig. 5 A). Presumably at low [Ca2+]o, the pore binding site for Ca2+ is no longer occupied and Na+ is less impeded in its transit through the pore. The normalized current amplitude plotted as a function of [Ca2+]o (Fig. 5 B) is typical of anomalous mole fraction behavior.

Figure 5.

CaChBacm (LDDWAD mutant) is a Ca2+-selective channel. (A) CaChBacm (LDDWAD) currents in various [Ca2+]o (substituted by Na+ to maintain isotonicity) elicited by depolarization from −100 to 0 mV. (B) Normalized current amplitude of the LDDWAD mutant plotted as a function of [Ca2+]o with Na+ substitution (±SEM, n = 6). (C) Averaged current density-voltage relations of LDDWAD in external solutions containing 1, 10, and 105 mM Ca2+ (±SEM, n = 6). (D) Reversal potentials (Erev) of the LDDWAD mutant plotted as a function of log [Ca2+]o (Na+ substitution; ±SEM, n = 6). The slope was fitted by linear regression analysis slope (25.6 mV per decade), close to slope predicted by the Nernst equation at 22°C (29 mV).

CaChBacm Is a Calcium-selective Channel

CaChBacm's (LDDWAD) channel conductance increased and the reversal potentials shifted to more positive potentials as [Ca2+]o was increased from 1 to 10 to 105 mM (Fig. 5 C). A plot of reversal potentials against log[Ca2+]o was best fit by a linear regression slope of 25.6 ± 3.2 mV/decade (mean ± SEM, n = 8) close to that predicted by the Nernst equation for a Ca2+-selective electrode (29 mV/decade). CaChBacm (LDDWAD) is thus a Ca2+-selective channel.

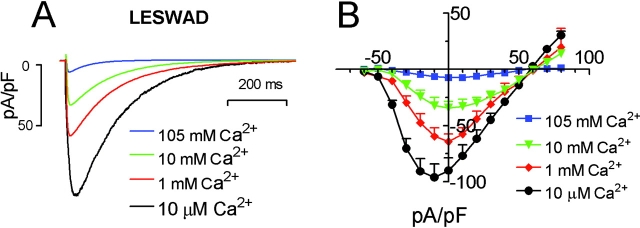

Interestingly, the LESWAD mutant that displayed a decreased permeability to Na+ compared with wt NaChBac, was blocked by [Ca2+]o. Fig. 6 A shows LESWAD currents recorded at 10 μM, 1 mM, 10 mM (in 130 mM [Na+]o), and 105 mM [Ca2+]o. The LESWAD mutant permeable to both Na+ and Ca2+, were largest in 10 μM Ca2+ solution and smallest in 105 mM [Ca2+]o. The mean I-V relations of LESWAD under various [Ca2+]o are shown in Fig. 6 B.

Figure 6.

The NaChBac LESWAD mutant is sensitive to Ca2+ blockade. (A) Currents recorded at 0 mV in varying [Ca2+]o with Na+ substitution. (B) Averaged I-V relations of the LESWAD mutant in 10 μM, 1 mM, 10 mM, and 105 mM [Ca2+]o (±SEM, n = 6). Note that the current density, but not Erev, changed with increasing [Ca2+]o.

DISCUSSION

We have used the simple 274 amino acid bacterial voltage–gated Na+-selective channel to explore the mechanism of Na+- and Ca2+-selective permeation. This opportunity is fairly unique since no other voltage-gated ion-selective bacterial channel has been functionally expressed in mammalian systems and there are no known mammalian voltage–gated Ca2+- or Na+-selective channels with the single repeat structure. Together with the wt NaChBac, the mutants described here suggest that voltage-gated Na+-selective, Ca2+-selective, and Na+/Ca2+-permeable cation channels can all be formed with the polypeptides of single repeat of the 6TM. The single-repeat 6TM structure is shared by voltage-gated potassium channels, TRP channels, and cyclic-nucleotide–gated channels. Voltage-gated Na+ or Ca2+ channels with this single-repeat structure have not been discovered in cells other than bacteria, but the recently reported mammalian sperm ion channels (Quill et al., 2001; Ren et al., 2001a) may be candidates for the functional homologues of the bacterial channel.

Our experiments show that mutation of amino acid residues in the pore domain can be mutated to make the channel cation nonselective, or even highly Ca2+ selective. The most interesting residues of the pore region were between amino acids 190–195 of NaChBac (LESWAS). We found a correlation between increasing numbers of negatively charged aspartic acid substitutions within the domain and increasing Ca2+ selectivity. The mutants denoted LESWAD, LEDWAS, LEDWAD, and LDDWAD displayed increasing selectivity for Ca2+, with LESWAD having the lowest and LDDWAD the highest Ca2+ selectivity.

In a model based on alignment with the bacterial K+-selective channel, KcsA, NaV channel Na+ permeation is theoretically blocked by an interaction between the D3 lysine (K;D3) amino group and the D2 glutamate (E;D2) carboxyl group (Lipkind and Fozzard, 2000). In this model the D3-K side chain must change its conformation for each Na+ ion that permeates, and selectivity is not determined by the size of the pore but by the ability of the permeating ion to compete with the amino group of K-D3. In contrast, Favre et al. (Favre et al., 1996) proposed a mechanism analogous to the selectivity filter of the Ca2+ channel. They suggested that Na+ binds to the filter, with the K-D3 amino group stabilizing the metal binding cavity, and as an endogenous cation altering the affinity of Na+ binding within the pore. In both cases, the D3-positive charge is a dominant component of the electrostatic field within the selectivity filter and the side chain determines the selectivity. Interestingly, there is no positively charged residue (K,R,H) in an analagous position in the NaChBac selectivity filter. The only positive charge (R199) in NaChBac pore loop is distal to the presumed selectivity filter, and neutralization (R199A) or replacement with a negatively charged amino acid (R199D) yields a channel that either is nonfunctional or too poorly conducting to yield measurable current (unpublished data).

Can the carbonyl oxygens (not the side chains), form a Na selectivity filter? Schild and colleagues propose that ENaC's (PNa/PK >100) subunit main-chain carbonyl oxygens line the channel pore with their side chain pointing away from the pore lumen. ENaC is more permeable to Li+ than Na+ ions and mutations of the residue in the pre-M2 segment made the channel permeant to K+ ions. Substitution of the critical residue (S589) with amino acids of increasing sizes shifted the molecular cutoff of the channel pore for inorganic and organic cations. Mutants with an increased permeability to large cations showed a decrease in the ENaC unitary conductance of small cations such as Na+ and Li+. They proposed that substitution of the ENaC S589 subunit by larger residues increases the pore diameter by adding extra volume at the subunit–subunit interface (Kellenberger et al., 2001). Such a hypothesis can be tested for NaChBac by further mutagenesis or obtainment of the high resolution structure.

In computational studies of K+ permeation, dynamical fluctuations of the carbonyl oxygen atoms that form the selectivity filter (Berneche and Roux, 2001) produce movements that are much larger than the difference in the radius of Na+ and K+ ions. Thus, for the K+ channel in which much more concrete data is available, selectivity does not arise from simple geometric considerations based on a rigid pore. Moreover, computational experiments indicate that the fluctuations of the protein structure have a large effect on the free energy profiles and on the selectivity of the channel (important properties of the pore are coupled to the fluctuations of a hydrogen bond between two residues nearly 12Å away). Understanding the mechanism of monovalent selectivity (e.g., Na+ vs. K+) is likely to be subtle and require both structural and functional data.

The permeation pathway of the NaV channel is formed by asymmetric loops from each domain, and asymmetry is commonly assumed to be an important aspect of Na+ selectivity. Since each subunit of NaChBac is presumably identical, is asymmetry a key attribute? It is likely that the linked four-domain structure for NaV and CaV channels conferred an evolutionary advantage, either in the kinetics of channel activation, inactivation, or recovery from inactivation. Given the high PNa/PK of NaChBac it seems less likely the four-domain structure evolved to provide increased monovalent selectivity.

NaChBac is truly highly Na+ selective (PNa/PK∼170, PNa/PCs∼380). In the present studies, we constructed a Ca2+-selective channel, but we did not switch the Na+-selective channel into a K+-selective channel. It is possible that the LDDWAD mutant merely created the right conditions for Ca2+ binding in the pore, but that the true monovalent selectivity filter may involve slightly shifted residues. Interestingly, two bacterial strains have homologues to our Ca-selective mutants (FEDWTD in Colwellia sp.34H and Microbulbifer degradans) and it will be important to determine if these are indeed native Ca2+-selective channels.

Although the steady-state inactivation (V1/2-inact) of LESWAD, LEDWAS, and LDDWAD were similar to those of wt NaChBac, their activation curves were shifted significantly to more depolarized potentials. The slope factor, k, of the Boltzmann fits for these mutants also indicated that the energy for activation was decreased; less charge has to be moved across the membrane to gate the channel. Thus, mutations in this restricted region of the pore not only affect selectivity, but also alter gating. We do not yet understand the activation and inactivation of NaChBac, but the short length of the intracellular domains and our early mutagenic studies indicate that NaChBac inactivation does not rely on the N and C termini. Also noteworthy is the especially short linker between the S3 and S4 domains, which may constrain the movement of the activation gate (Gonzalez et al., 2001). We postulate that the four-domain structure somehow enables the increased speed of activation and recovery from inactivation needed for fast, repetitive signaling. Hopefully, this hypothesis can be tested in future studies of NaChBac gating.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Kraner (University of Kentucky) for generously providing the SKM1 clone and to Louis DeFelice, Robert Guy, Richard Aldrich, Chris Miller, and Ed Moczydlowski for helpful discussion.

B. Navarro was supported by the Kaplan Fellowship.

Lixia Yue, Betsy Navarro, and Dejian Ren contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: 6TM, six transmembrane; wt, wild-type.

References

- Armstrong, C.M., and B. Hille. 1998. Voltage-gated ion channels and electrical excitability. Neuron. 20:371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitah, J.P., Z. Chen, J.R. Balser, G.F. Tomaselli, and E. Marban. 1999. Molecular dynamics of the sodium channel pore vary with gating: interactions between P-segment motions and inactivation. J. Neurosci. 19:1577–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitah, J.P., R. Ranjan, T. Yamagishi, M. Janecki, G.F. Tomaselli, and E. Marban. 1997. Molecular motions within the pore of voltage-dependent sodium channels. Biophys. J. 73:603–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berneche, S., and B. Roux. 2001. Energetics of ion conduction through the K+ channel. Nature. 414:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., H.A. Hartmann, and G.E. Kirsch. 1997. Cysteine mapping in the ion selectivity and toxin binding region of the cardiac Na+ channel pore. J. Membr. Biol. 155:11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z., C. Alcayaga, B.A. Suarez-Isla, B. O'Rourke, G. Tomaselli, and E. Marban. 2002. A “minimal” sodium channel construct consisting of ligated S5-P-S6 segments forms a toxin-activatable ionophore. J. Biol. Chem. 277:24653–24658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamvimonvat, N., M.T. Perez-Garcia, R. Ranjan, E. Marban, and G.F. Tomaselli. 1996. Depth asymmetries of the pore-lining segments of the Na+ channel revealed by cysteine mutagenesis. Neuron. 16:1037–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibulsky, S.M., and W.A. Sather. 2000. The EEEE locus is the sole high-affinity Ca2+ binding structure in the pore of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel: block by Ca(2+) entering from the intracellular pore entrance. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:349–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloues, R.K., S.M. Cibulsky, and W.A. Sather. 2000. Ion interactions in the high-affinity binding locus of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:569–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, D.A., J. Morais Cabral, R.A. Pfuetzner, A. Kuo, J.M. Gulbis, S.L. Cohen, B.T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 1998. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 280:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durell, S.R., and H.R. Guy. 2001. A putative prokaryote voltage-gated Ca2+ channel with only one 6TM motif per subunit. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinor, P.T., J. Yang, W.A. Sather, J.F. Zhang, and R.W. Tsien. 1995. Ca2+ channel selectivity at a single locus for high-affinity Ca2+ interactions. Neuron. 15:1121–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, E.M., A.T. Malouf, and W.A. Catterall. 1995. Role of calcium channel subtypes in calcium transients in hippocampal CA3 neurons. J. Neurosci. 15:6433–6444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre, I., E. Moczydlowski, and L. Schild. 1996. On the structural basis for ionic selectivity among Na+, K+, and Ca2+ in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biophys. J. 71:3110–3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, C., E. Rosenman, F. Bezanilla, O. Alvarez, and R. Latorre. 2001. Periodic perturbations in Shaker K+ channel gating kinetics by deletions in the S3-S4 linker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:9617–9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, S.H., H. Terlau, W. Stuhmer, K. Imoto, and S. Numa. 1992. Calcium channel characteristics conferred on the sodium channel by single mutations. Nature. 356:441–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, P., J.B. Lansman, and R.W. Tsien. 1986. Calcium channel selectivity for divalent and monovalent cations. Voltage and concentration dependence of single channel current in ventricular heart cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 88:293–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, P., and R.W. Tsien. 1984. Mechanism of ion permeation through calcium channels. Nature. 309:453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. 2001. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, third edition, Sunderland, MA.

- Kellenberger, S., M. Auberson, I. Gautschi, E. Schneeberger, and L. Schild. 2001. Permeability properties of ENaC selectivity filter mutants. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:679–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraner, S.D., M.M. Rich, R.G. Kallen, and R.L. Barchi. 1998. Two E-boxes are the focal point of muscle-specific skeletal muscle type 1 Na+ channel gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 273:11327–11334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind, G.M., and H.A. Fozzard. 2000. KcsA crystal structure as framework for a molecular model of the Na+ channel pore. Biochemistry. 39:8161–8170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleskey, E.W. 1999. Calcium channel permeation: A field in flux. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:765–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher, E. 1992. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods Enzymol. 207:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda, M., T. Ikeda, T. Kayano, H. Suzuki, H. Takeshima, M. Kurasaki, H. Takahashi, and S. Numa. 1986. Existence of distinct sodium channel messenger RNAs in rat brain. Nature. 320:188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzotti, J.L., H.A. Fozzard, G.M. Lipkind, and S.C. Dudley, Jr. 1998. Differences in saxitoxin and tetrodotoxin binding revealed by mutagenesis of the Na+ channel outer vestibule. Biophys. J. 75:2647–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garcia, M.T., N. Chiamvimonvat, R. Ranjan, J.R. Balser, G.F. Tomaselli, and E. Marban. 1997. Mechanisms of sodium/calcium selectivity in sodium channels probed by cysteine mutagenesis and sulfhydryl modification. Biophys. J. 72:989–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quill, T.A., D. Ren, D.E. Clapham, and D.L. Garbers. 2001. A voltage-gated ion channel expressed specifically in spermatozoa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12527–12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, D., B. Navarro, G. Perez, A.C. Jackson, S. Hsu, Q. Shi, J.L. Tilly, and D.E. Clapham. 2001. a. A sperm ion channel required for sperm motility and male fertility. Nature. 413:603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, D., B. Navarro, H. Xu, L. Yue, Q. Shi, and D.E. Clapham. 2001. b. A prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel. Science. 294:2372–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.M., I. Favre, L. Schild, and E. Moczydlowski. 1997. On the structural basis for size-selective permeation of organic cations through the voltage-gated sodium channel. Effect of alanine mutations at the DEKA locus on selectivity, inhibition by Ca2+ and H+, and molecular sieving. J. Gen. Physiol. 110:693–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S., G. Mikala, A. Bahinski, A. Yatani, G. Varadi, and A. Schwartz. 1993. Molecular localization of ion selectivity sites within the pore of a human L-type cardiac calcium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 268:13026–13029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.S., H.D. Edwards, and W.A. Sather. 2000. Side chain orientation in the selectivity filter of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31778–31785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., P.T. Ellinor, W.A. Sather, J.F. Zhang, and R.W. Tsien. 1993. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ selectivity and ion permeation in L-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 366:158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]