Abstract

Background

Low grade fibromyxoid sarcomas (LGFMS) are very rarely seen. They commonly arise from deep soft tissues of the lower extremities. Very few cases of intra-abdominal location have been reported.

Case presentation

We report a 37 year old man who presented with an abdominal mass and dragging pain. Pre-operative imaging suggested the possibility of a subcapsular hemangioma of liver.

Conclusions

Laparoscopy was useful to locate the tumor as arising from falciform ligament and made the subsequent surgery simpler. This is one of the large fibromyxoid sarcomas to be reported.

Background

Low grade fibromyxoid sarcomas (LGFMS) of the soft tissues are usually situated in the deep soft tissues of the lower extremity, particularly the thigh [1]. It is seen in a young or middle aged adult and is more common in the male. Though they are sporadically seen in other areas like the chest wall or shoulder they are very rarely reported in an intra-abdominal location. We report a 37-year old man with a giant intra-abdominal low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma measuring 21 cm in size; which was mistaken for a possible hemangioma of the liver on CT scan.

Case report

A 37 year old man noticed a mass in the epigastric region since four months and dull non radiating pain in the epigastrium since a month and a half. A few distended veins were seen over the abdominal wall. Abdominal examination revealed a non tender firm intra-abdominal mass in the epigastrium moving with respiration. A doubtful lateral mobility was present. An ultrasound study of the abdomen showed a large well encapsulated mass in the left lobe of liver with caudal exophytic expansion [Fig 1]. CT scan demonstrated the lesion extrinsically indenting stomach showing initial peripheral enhancement with centripetal filling on time delay [Fig 2]. There was no calcification. The mass was situated between the anterior abdominal wall and liver; but in close relation to the latter. In view of these findings, the possibility of a sub capsular mass, probably a hemangioma on the anterior surface of the left lobe of liver was considered. Biochemical and hematological investigations were within normal limits including liver function tests.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound study of abdomen showing the mass in close relation to left lobe of liver.

Figure 2.

CT scan of the abdomen shows the close relation of mass to abdominal wall and liver. Peripheral enhancement of contrast can also be appreciated.

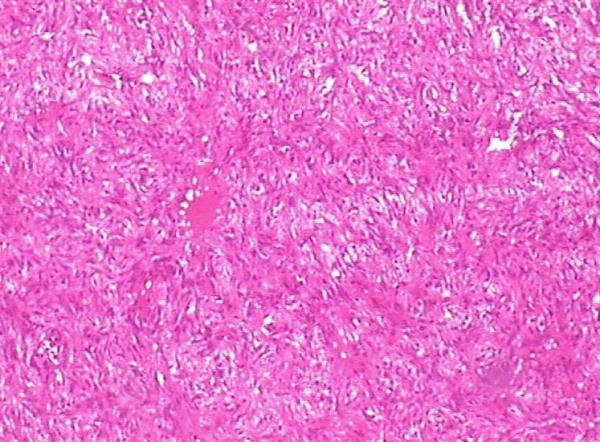

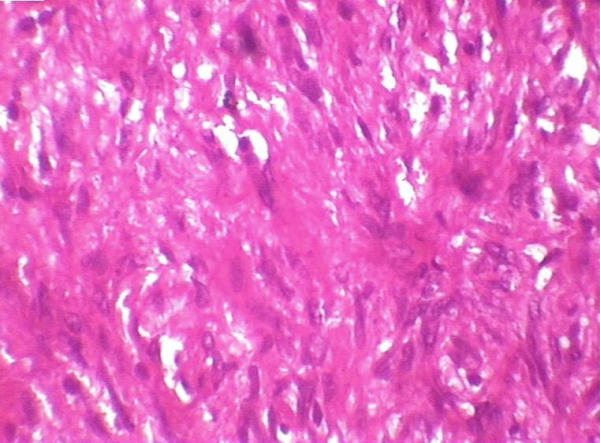

A pre-operative fine needle aspiration was not done as there was a suspicion of hemangioma. A diagnostic laparoscopy was planned to visualize the location of the tumor and its relation to other organs. It was decided that the surgical plan would be based on the laparoscopic findings. If the lesion were found to arise from the liver or if the excision of the tumor necessitated removal of a segment of liver, it was decided to biopsy the lesion and plan a definitive surgery later. Laparoscopy revealed a large mass lesion situated between the leaves of the falciform ligament abutting against the anterior surface of the liver; but the liver per se was normal and free from the tumor. A number of enlarged tortuous blood vessels were seen running from the anterior abdominal wall to the mass. Anterior abdominal wall was incised and the tumor accessed through a supra-umbilical incision. The laparoscope also assisted in identifying the tortuous vessels limiting the intra-operative blood loss. Wide excision was completed. As it was desirable to perform an excision with intact capsule, a laparoscopic excision was not attempted. The globular bosselated well encapsulated mass [Fig 3, 4] measuring 21 × 16 × 10 cm was situated between the leaves of the falciform ligament with neither involvement of the abdominal wall nor the liver. A frozen section study was not considered as the surgery would not have been different if the report were to be either benign or malignant. Cut section showed a grayish white appearance with focal areas of hemorrhage [Fig 5]. Post operative recovery was uneventful. Histologically, on initial evaluation, the mass appeared to be composed of interlacing fascicles of spindle shaped fibroblasts with cartwheel arrangement [Fig 6, 7] suggesting a possibility of fibrous histiocytoma. However, further evaluation with multiple sections showed a tumor with moderate to low cellularity. The tumor was composed of bland spindle shaped cells with small hyperchromatic oval to tapering nuclei, containing finely clumped chromatin with palely eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells showed mild nuclear pleomorphism with little mitotic activity. The cells were deposited in a variably fibrous and myxoid stroma having stellate cells [Fig 8]. The cells showed whorled arrangement in a random manner. Perivascular hypercellularity was noted in some areas [Fig 9]. Based on these features, the tumor was diagnosed as low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Immunohistochemistry was performed to confirm the diagnosis. The neoplasm stained strongly and diffusely for vimentin [Fig 10]. Staining for other markers including CD 34, CD 68, smooth muscle actin and S 100 were negative [Fig 11].

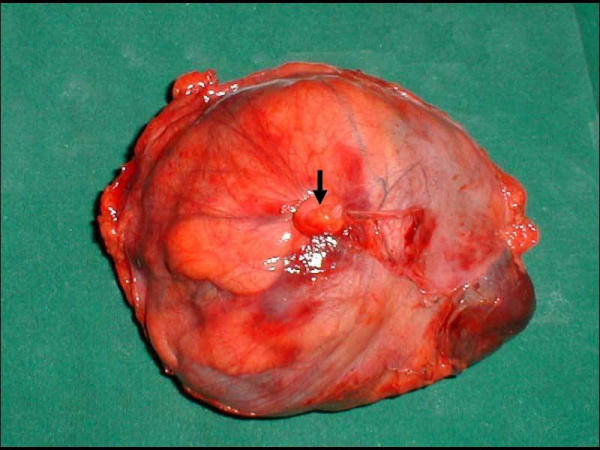

Figure 3.

Post operative specimen showing bosselated appearance with intact capsule (anterior view).

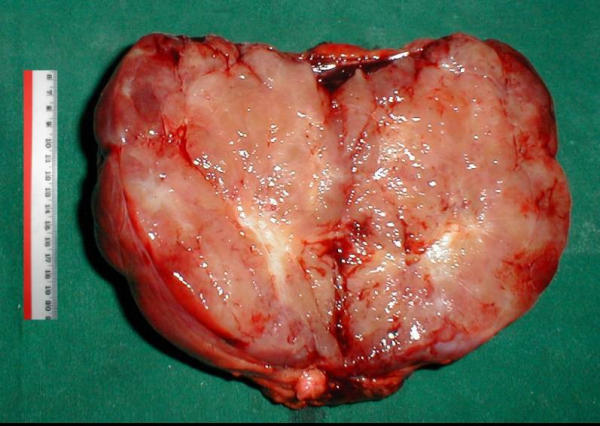

Figure 4.

Specimen showing tumor covered with falciform ligament and the tied ligamentum teres which is indicated by bold arrow (posterior view).

Figure 5.

Cut section of the tumor showing a fleshy mass with some areas of hemorrhage.

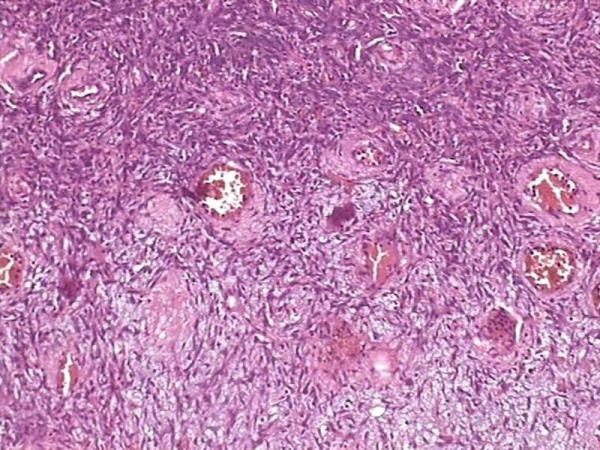

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of the mass showing spindle cells arranged in storiform pattern as seen with low magnification (100X). Staining is done with hematoxylin and eosin.

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph of the mass with high magnification (400X). Staining is done with hematoxylin and eosin.

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph showing bland spindle shaped cells deposited in a variably fibrous and myxoid stroma (100X). Hematoxylin and eosin stain.

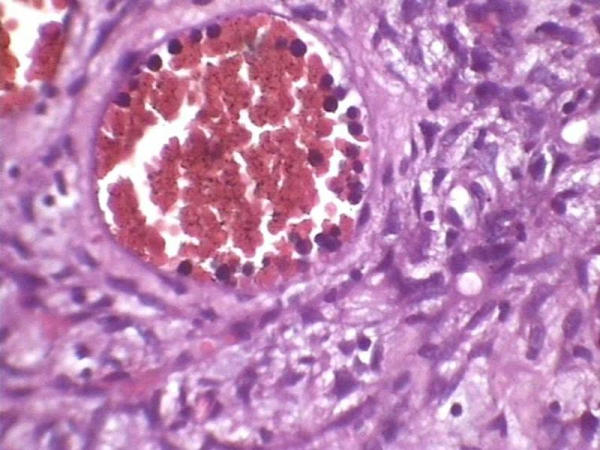

Figure 9.

Photomicrograph showing perivascular hypercellularity (400X). Hematoxylin and eosin stain.

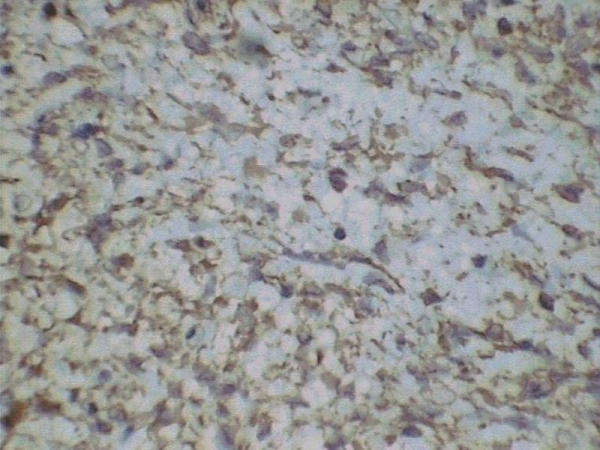

Figure 10.

Immunohistochemistry: Tumor immunoreactive to vimentin.

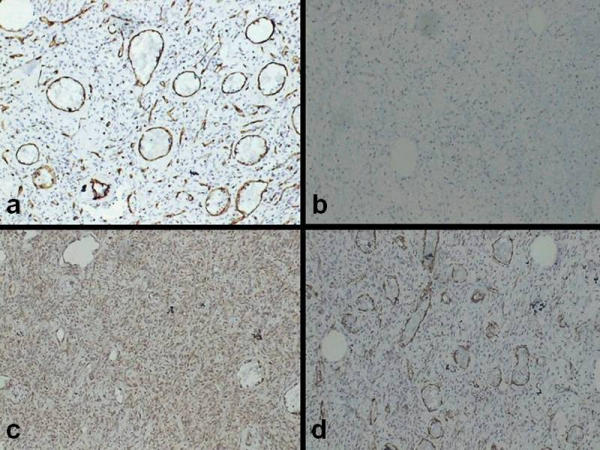

Figure 11.

Immunohistochemistry: Tumor non reactive with CD 34 (a), CD 68 (b), S 100 (c) and smooth muscle actin (d).

Conclusion

LGFMS was identified as a distinct entity in 1987 [2]. Though patients as young as 3 years and as old as 78 years have been diagnosed with this tumor, it commonly afflicts young to middle aged adults, males more than females [1,3-5].

Dragging of Glisson's capsule due to the large size probably accounts for pain in the present case as these are usually painless slowly growing masses. This mass was mistaken for a hemangioma for reasons cited earlier. Hence a pre-operative cytological diagnosis was not possible. In addition, needle aspiration study is not specific for diagnosis [6]. This problem of diagnosis was partly circumvented by laparoscopy. The surgical plan was based on the laparoscopic findings and it helped in anatomic localization of the lesion. Further, the identification of large tortuous vessels in the vicinity of the tumor helped in reducing the hemorrhage at surgery. This vascular supply of the tumor accounts for the peripheral enhancement which led us to suspect a possible subcapsular hemangioma of the liver.

LGFMS usually arises in the deep soft tissue of the lower extremity particularly the thigh [1,7]. Many of them arise in the skeletal muscle while some of them are confined to subcutaneous tissue [1]. Although this patient did not show invasion of surrounding tissues on microscopy, these tumors could have extensive infiltration to surrounding tissues even when the tumor is grossly well circumscribed. These tumors have been described in locations like the chest wall, axilla, shoulder, inguinal region, buttock and the neck apart from thigh [1,8-10]. Rare reports include those in the retroperitoneum, the small bowel mesentery, pelvis and the mediastinum [11-15]. Though a large LGFMS has been reported to arise from the abdominal wall [16], it has not been reported in the falciform ligament.

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells stain strongly and diffusely for vimentin [1]. Rarely, focal immunoreactivity could be seen for smooth muscle actin, desmin or cytokeratin [1,17]. Though CD 34 is negative, one case of diffuse staining has been reported [18]. LGFMS with giant rosettes has been identified as a separate entity but there are arguments to consider them as same tumor with some varying features on microscopy [3,19]. In two LGFMS, no abnormal DNA content or chromosomal aberrations were noted but cytogenetic analysis revealed a ring chromosome in another report [20,21]. In the present case, the cells expressed vimentin but there was no immunoreactivity with other markers.

LGFMS must be distinguished from myxofibrosarcoma as their clinical behaviors are different with LGFMS likely to metastasize more often [22]. The latter lacks areas of fibrous stroma, is uniformly myxoid and in addition it does not show whorled arrangement of tumor cells [12]. Other malignant tumors that need to be distinguished from LGFMS include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor and spindle cell liposarcoma [1]. More often these lesions are mistaken for benign lesions like myxoid neurofibroma, desmoid fibromatosis, perineuroma or nodular fascitis [1,23]. The initial evaluation led us to believe that the tumor was a fibrous histiocytoma. However, with the study of more sections and the help of a reference pathologist, the tumor was diagnosed as LGFMS. The other lesions described above have been excluded in the present case by microscopic findings and immunohistochemistry.

These tumors have been reported to recur and metastasize [1,10,24]. These tumors have recurred as early as 6 months to as late as 50 years in 65% of patients. Metastasis also has been reported to occur frequently with lung being a common site. These tumors have a protracted course even after metastasis. Interestingly, in a larger study, only 5% metastasis has been reported attributing this to prospectively following up a low grade sarcoma while earlier studies have worked back on a metastatic disease [3]. Although a satisfactory wide excision with an intact capsule was possible, as the tumor was large and deep seated, this patient is kept under follow-up. Patient is recurrence free at one year. Adjuvant radiation was not considered in view of the peculiar position of the tumor. Responses to chemotherapy have been poor and with the limited experience must be considered investigational.

Even with advent of many imaging modalities, in certain situations like the one described, a cytopathological diagnosis may not be technically feasible. Diagnostic laparoscopy would be very useful for anatomic localization. Proper histopathologic evaluation of the tumor and immunohistochemistry is necessary for accurate diagnosis. Exclusion of other similar appearing tumors is essential.

List of abbreviations used

LGFMS: Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma

Authors' contributions

KH was the principal clinician who planned the evaluation and procedure, in addition to conceptualizing and drafting the article.

ACA performed the laparoscopy

NKA was the pathologist who evaluated the specimen.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

Dr. Rekha V Kumar, Associate Professor of Pathology at the Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology (A Regional Cancer Center), Bangalore, INDIA was the reference pathologist. We wish to thank her for helping us with the pathologic study of the tumor including the immunohistochemical study.

"Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the patient's details."

Contributor Information

K Harish, Email: drkhari@yahoo.com.

AC Ashok, Email: acashok@hotmail.com.

NK Alva, Email: alvakishore@yahoo.com.

References

- Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Benign fibrohistiocytic tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW Mosby, editor. In Soft tissue tumors. 4. 2001. pp. 409–39. [Google Scholar]

- Evans HL. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. A report of two metastasizing neoplasms having a deceptively benign appearance. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;88:615–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/88.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folpe AL, Lane KL, Paull G, Weiss SW. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes: a clinicopathologic study of 73 cases supporting their identity and assessing the impact of high-grade areas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1353–60. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka Y, Matsuda M, Katsura T, Tanaka K, Ebara H, Yoshida F, Takaba E, Takimoto M. Case of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma [in Japanese] Nippon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;86:1458–60. doi: 10.2169/naika.86.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canpolat C, Evans HL, Corpron C, Andrassy RJ, Chan K, Eifel P, Elidemir O, Raney B. Fibromyxoid sarcoma in a four-year-old child: case report and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27:561–4. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199612)27:6<561::AID-MPO10>3.3.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg GM, Maitra A, Gokaslan ST, Saboorian MH, Albores-Saavedra J. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: fine-needle aspiration cytology with histologic, cytogenetic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural correlation. Cancer. 1999;87:75–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990425)87:2<75::AID-CNCR6>3.3.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugai K, Kizaki T, Morimoto K, Sashikata T. A case of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the thigh. Pathol Int. 1994;44:793–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1994.tb02928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husek K, Janicek P, Jelinek O. Low grade malignant fibromyxoid sarcoma [In Czech with English abstract] Cesk Patol. 1998;34:139–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamecnik M, Michal M. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma: A Report of Eight Cases With Histologic, Immunohistochemical, and Ultrastructural Study. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:207–17. doi: 10.1053/adpa.2000.8122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaney DM, Dervan P, O'Neill S, Carney D, Leader M. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Histopathology. 1990;17:463–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans HL. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. A report of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:595–600. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlad JR, Mentzel T, Fletcher CD. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of eleven new cases in support of a distinct entity. Histopathology. 1995;26:229–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji M, Konishi K, Funaki K, Nukui A, Goka T, Arakawa G, Onishi I, Kimura H, Maeda K, Yabushita K, Tsuji M, Yamashita H, Miwa A. A case of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the small bowel mesentery [In Japanese] Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1999;96:670–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidham VB, Ayala GE, Lahaniatis JE, Garcia FU. Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma: Clinicopathologic Case Report With Review of the Literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:150–5. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takanami I, Takeuchi K, Naruke M. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma arising in the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118:970–1. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bossche MR, Van Mieghem H. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Oncology. 2000;58:207–9. doi: 10.1159/000012101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga M, Ushigome S, Fukunaga N. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Virchows Archiv. 1996;429:301–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00198346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols GE, Cooper PH. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: case report and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:356–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1994.tb00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane KL, Shannon RJ, Weiss SW. Hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes: a distinctive tumor closely resembling low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1481–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199712000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzelani A, Sozzi G, Nessling M, Riva C, Della Torre G, Testi MA, Azzarelli A, Pierotti MA, Lichter P, Pilotti S. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. a further low-grade soft tissue malignancy characterized by a ring chromosome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;122:144–8. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(00)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akoi T, Hisaoka M, Kouho H, Hashimoto H, Nakata H. Interphase cytogenetic analysis of myxoid soft tissue tumors by fluorescence in situ hybridization and DNA flow cytometry using paraffin embedded tissue. Cancer. 1997;79:284–93. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970115)79:2<284::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentzel T, Katenkamp D, Fletcher CD. Low malignancy myxofibrosarcoma versus low malignancy fibromyxoid sarcoma. Distinct entities with similar names but different clinical course [in German with English abstract] Pathologe. 1996;17:116–21. doi: 10.1007/s002920050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollowood K, Fletcher CD. Soft tissue sarcomas that mimic benign lesions. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1995;12:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvornik G, Barbareschi M, Gallotta P, Palma PD. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Histopathology. 1997;30:274–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.d01-595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]