Abstract

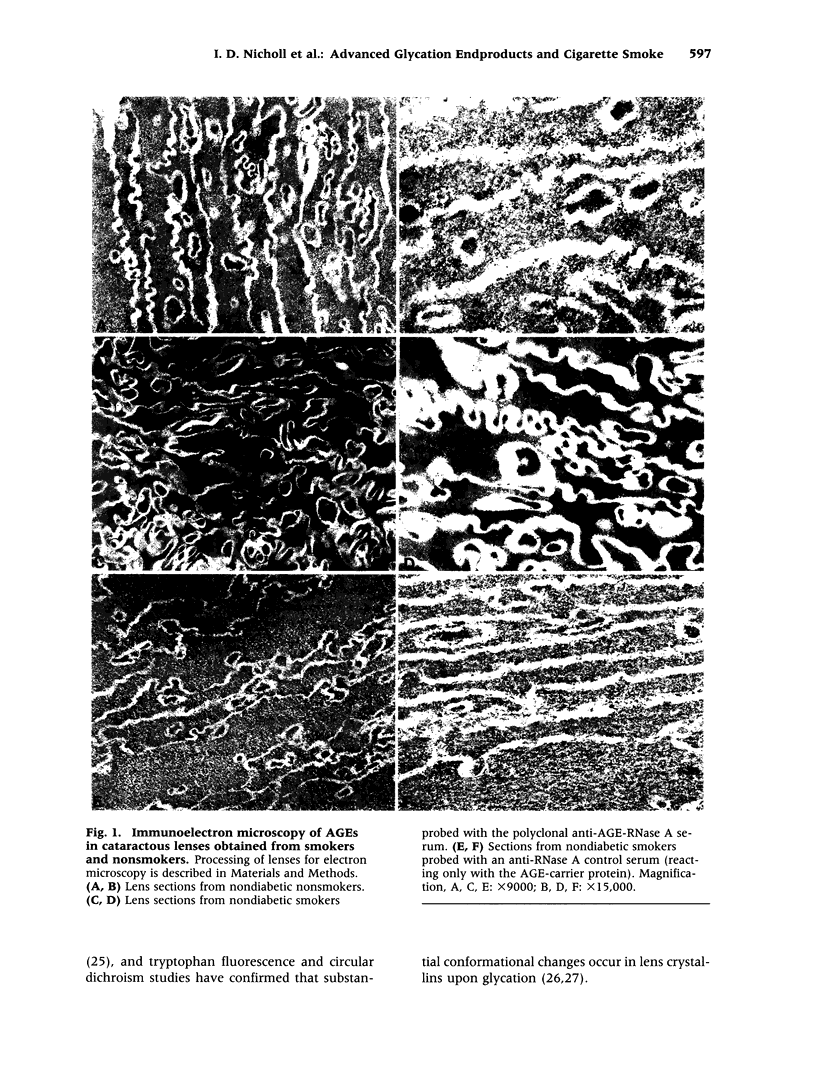

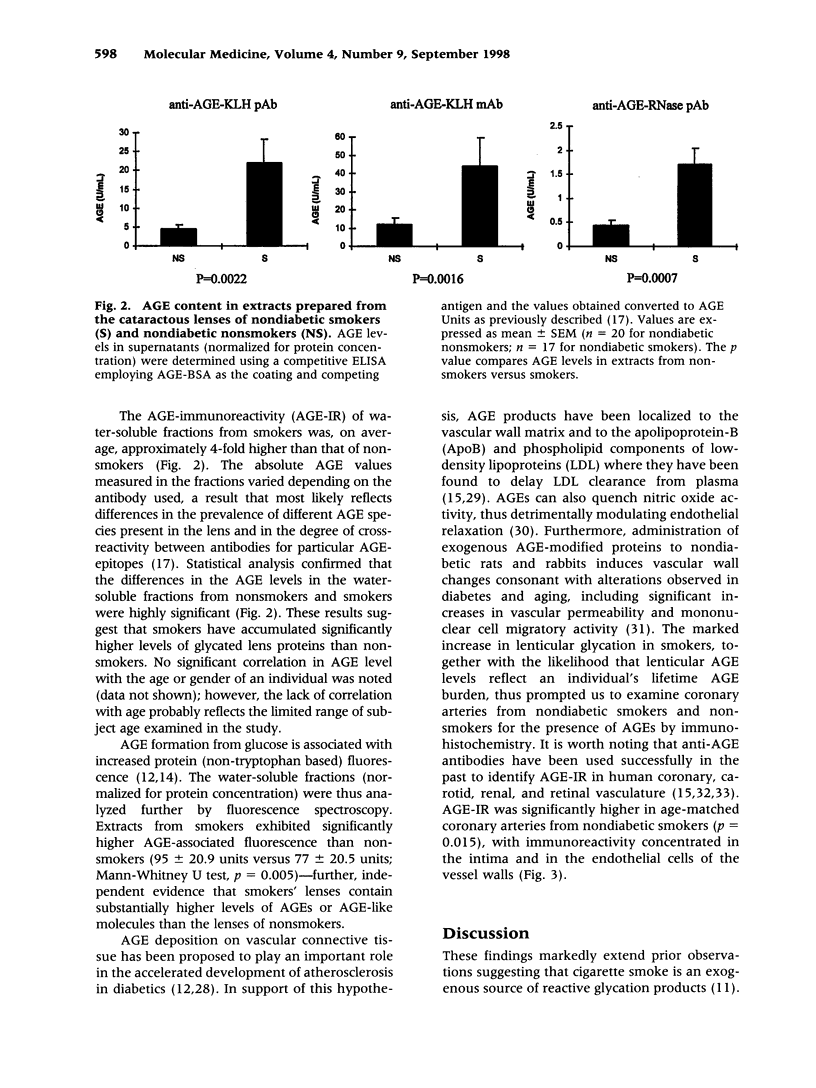

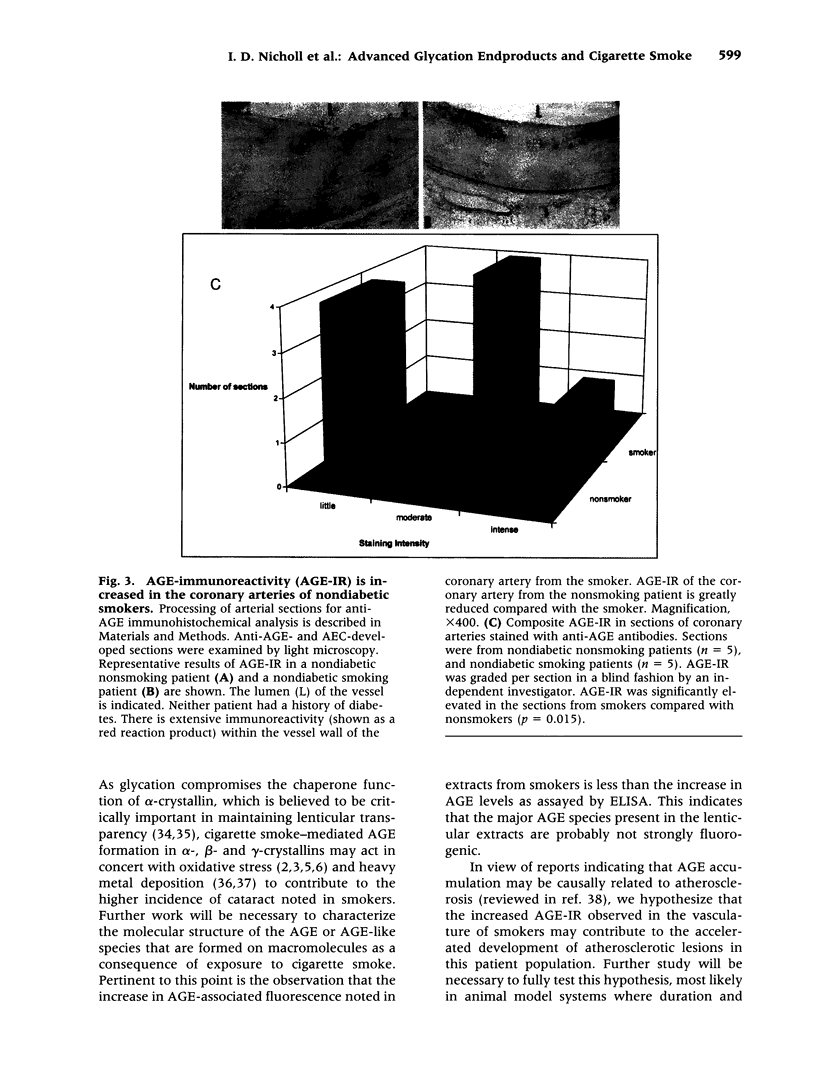

BACKGROUND: Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) arise from the spontaneous reaction of reducing sugars with the amino groups of macromolecules. AGEs accumulate in tissue as a consequence of diabetes and aging and have been causally implicated in the pathogenesis of several of the end-organ complications of diabetes and aging, including cataract, atherosclerosis, and renal insufficiency. It has been recently proposed that components in mainstream cigarette smoke can react with plasma and extracellular matrix proteins to form covalent adducts with many of the properties of AGEs. We wished to ascertain whether AGEs or immunochemically related molecules are present at higher levels in the tissues of smokers. MATERIALS AND METHODS: Lens and coronary artery specimens from nondiabetic smokers and nondiabetic nonsmokers were examined by immunohistochemistry, immunoelectron microscopy, and ELISA employing several distinct anti-AGE antibodies. In addition, lenticular extracts were tested for AGE-associated fluorescence by fluorescence spectroscopy. RESULTS: Immunoreactive AGEs were present at significantly higher levels in the lenses and lenticular extracts of nondiabetic smokers (p < 0.003). Anti-AGE immunogold staining was diffusely distributed throughout lens fiber cells. AGE-associated fluorescence was significantly increased in the lenticular extracts of nondiabetic smokers (p = 0.005). AGE-immunoreactivity was significantly elevated in coronary arteries from nondiabetic smokers compared with nondiabetic nonsmokers (p = 0.015). CONCLUSIONS: AGEs or immunochemically related molecules are present at higher levels in the tissues of smokers than in nonsmokers, irrespective of diabetes. In view of previous reports implicating AGEs in a causal association with numerous pathologies, these findings have significant ramifications for understanding the etiopathology of diseases associated with smoking, the single greatest preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Araki N., Ueno N., Chakrabarti B., Morino Y., Horiuchi S. Immunochemical evidence for the presence of advanced glycation end products in human lens proteins and its positive correlation with aging. J Biol Chem. 1992 May 25;267(15):10211–10214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartecchi C. E., MacKenzie T. D., Schrier R. W. The human costs of tobacco use (1) N Engl J Med. 1994 Mar 31;330(13):907–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beswick H. T., Harding J. J. Conformational changes induced in lens alpha- and gamma-crystallins by modification with glucose 6-phosphate. Implications for cataract. Biochem J. 1987 Sep 15;246(3):761–769. doi: 10.1042/bj2460761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M., Cerami A., Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation end products in tissue and the biochemical basis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med. 1988 May 19;318(20):1315–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805193182007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucala R., Cerami A. Advanced glycosylation: chemistry, biology, and implications for diabetes and aging. Adv Pharmacol. 1992;23:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60961-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucala R., Makita Z., Vega G., Grundy S., Koschinsky T., Cerami A., Vlassara H. Modification of low density lipoprotein by advanced glycation end products contributes to the dyslipidemia of diabetes and renal insufficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Sep 27;91(20):9441–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucala R., Tracey K. J., Cerami A. Advanced glycosylation products quench nitric oxide and mediate defective endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in experimental diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1991 Feb;87(2):432–438. doi: 10.1172/JCI115014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami C., Founds H., Nicholl I., Mitsuhashi T., Giordano D., Vanpatten S., Lee A., Al-Abed Y., Vlassara H., Bucala R. Tobacco smoke is a source of toxic reactive glycation products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Dec 9;94(25):13915–13920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Loo G. Inhibition of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase activity in human blood plasma by cigarette smoke extract and reactive aldehydes. J Biochem Toxicol. 1995 Jun;10(3):121–128. doi: 10.1002/jbt.2570100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian M., Abraham E. C. Diabetes affects alpha-crystallin chaperone function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995 Jul 6;212(1):184–189. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen W. G., Manson J. E., Seddon J. M., Glynn R. J., Buring J. E., Rosner B., Hennekens C. H. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of cataract in men. JAMA. 1992 Aug 26;268(8):989–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denissenko M. F., Pao A., Tang M., Pfeifer G. P. Preferential formation of benzo[a]pyrene adducts at lung cancer mutational hotspots in P53. Science. 1996 Oct 18;274(5286):430–432. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. A., Patrick J. S., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. Oxidation of glycated proteins: age-dependent accumulation of N epsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine in lens proteins. Biochemistry. 1989 Nov 28;28(24):9464–9468. doi: 10.1021/bi00450a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei B., Forte T. M., Ames B. N., Cross C. E. Gas phase oxidants of cigarette smoke induce lipid peroxidation and changes in lipoprotein properties in human blood plasma. Protective effects of ascorbic acid. Biochem J. 1991 Jul 1;277(Pt 1):133–138. doi: 10.1042/bj2770133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlick R. L., Mazer J. S., Chylack L. T., Jr, Tung W. H., Bunn H. F. Nonenzymatic glycation of human lens crystallin. Effect of aging and diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1984 Nov;74(5):1742–1749. doi: 10.1172/JCI111592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson S. E., Willett W. C., Colditz G. A., Seddon J. M., Rosner B., Speizer F. E., Stampfer M. J. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of cataract surgery in women. JAMA. 1992 Aug 26;268(8):994–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding J. J., Dilley K. J. Structural proteins of the mammalian lens: a review with emphasis on changes in development, aging and cataract. Exp Eye Res. 1976 Jan;22(1):1–73. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(76)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra M., Balasubramanian D. Nonenzymatic glycation alters protein structure and stability. A study of two eye lens crystallins. J Biol Chem. 1993 Aug 25;268(24):18119–18127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makita Z., Vlassara H., Cerami A., Bucala R. Immunochemical detection of advanced glycosylation end products in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1992 Mar 15;267(8):5133–5138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi T., Vlassara H., Founds H. W., Li Y. M. Standardizing the immunological measurement of advanced glycation endproducts using normal human serum. J Immunol Methods. 1997 Aug 22;207(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier V. M., Kohn R. R., Cerami A. Accelerated age-related browning of human collagen in diabetes mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Jan;81(2):583–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier V. M., Stevens V. J., Cerami A. Nonenzymatic glycosylation, sulfhydryl oxidation, and aggregation of lens proteins in experimental sugar cataracts. J Exp Med. 1979 Nov 1;150(5):1098–1107. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.5.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Horii Y., Nishino T., Shiiki H., Sakaguchi Y., Kagoshima T., Dohi K., Makita Z., Vlassara H., Bucala R. Immunohistochemical localization of advanced glycosylation end products in coronary atheroma and cardiac tissue in diabetes mellitus. Am J Pathol. 1993 Dec;143(6):1649–1656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill C. A., Halliwell B., van der Vliet A., Davis P. A., Packer L., Tritschler H., Strohman W. J., Rieland T., Cross C. E., Reznick A. Z. Aldehyde-induced protein modifications in human plasma: protection by glutathione and dihydrolipoic acid. J Lab Clin Med. 1994 Sep;124(3):359–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R., Lopez A. D., Boreham J., Thun M., Heath C., Jr, Doll R. Mortality from smoking worldwide. Br Med Bull. 1996 Jan;52(1):12–21. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan S., Sulochana K. N., Selvaraj T., Abdul Rahim A., Lakshmi M., Arunagiri K. Smoking of beedies and cataract: cadmium and vitamin C in the lens and blood. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Mar;79(3):202–206. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.3.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rácz P., Erdöhelyi A. Cadmium, lead and copper concentrations in normal and senile cataractous human lenses. Ophthalmic Res. 1988;20(1):10–13. doi: 10.1159/000266248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J. P., Jenner A., Chimel K., Aruoma O. I., Cross C. E., Wu R., Halliwell B. DNA damage in human respiratory tract epithelial cells: damage by gas phase cigarette smoke apparently involves attack by reactive nitrogen species in addition to oxygen radicals. FEBS Lett. 1995 Nov 20;375(3):179–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01199-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt A. W., He C., Friedman S., Scher L., Rossi P., Ong L., Founds H., Li Y. M., Bucala R., Vlassara H. Elevated AGE-modified ApoB in sera of euglycemic, normolipidemic patients with atherosclerosis: relationship to tissue AGEs. Mol Med. 1997 Sep;3(9):617–627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt A. W., Li Y. M., Gardiner T. A., Bucala R., Archer D. B., Vlassara H. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) co-localize with AGE receptors in the retinal vasculature of diabetic and of AGE-infused rats. Am J Pathol. 1997 Feb;150(2):523–531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassara H., Fuh H., Makita Z., Krungkrai S., Cerami A., Bucala R. Exogenous advanced glycosylation end products induce complex vascular dysfunction in normal animals: a model for diabetic and aging complications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Dec 15;89(24):12043–12047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel M. A., Hoogakker S. E., Harding J. J., de Jong W. W. The influence of some post-translational modifications on the chaperone-like activity of alpha-crystallin. Ophthalmic Res. 1996;28 (Suppl 1):32–38. doi: 10.1159/000267940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]