Abstract

During replication arrest, the DNA replication checkpoint plays a crucial role in the stabilization of the replisome at stalled forks, thus preventing the collapse of active forks and the formation of aberrant DNA structures. How this checkpoint acts to preserve the integrity of replication structures at stalled fork is poorly understood. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the DNA replication checkpoint kinase Cds1 negatively regulates the structure-specific endonuclease Mus81/Eme1 to preserve genomic integrity when replication is perturbed. Here, we report that, in response to hydroxyurea (HU) treatment, the replication checkpoint prevents S-phase–specific DNA breakage resulting from Mus81 nuclease activity. However, loss of Mus81 regulation by Cds1 is not sufficient to produce HU-induced DNA breaks. Our results suggest that unscheduled cleavage of stalled forks by Mus81 is permitted when the replisome is not stabilized by the replication checkpoint. We also show that HU-induced DNA breaks are partially dependent on the Rqh1 helicase, the fission yeast homologue of BLM, but are independent of its helicase activity. This suggests that efficient cleavage of stalled forks by Mus81 requires Rqh1. Finally, we identified an interplay between Mus81 activity at stalled forks and the Chk1-dependent DNA damage checkpoint during S-phase when replication forks have collapsed.

INTRODUCTION

Before each nuclear division, eukaryotic cells must fully replicate their genome in order to segregate intact chromosomes into daughter cells. DNA replication requires tightly coordinated processes involving the assembly of protein complexes at well-defined replication origins and programmed timing of origin firing (Diffley and Labib, 2002). DNA synthesis is a critical phase of the cell cycle because failure of the DNA replication process can result in genetic instability. Progression of replication forks can be challenged by various obstacles including induced and spontaneous DNA lesions, DNA secondary structures, DNA/protein complexes, and defects in the replication apparatus (Lambert and Carr, 2005). To overcome such impediments, which can challenge replication fork integrity, cells have evolved several mechanisms to ensure replication completion before cell division and thereby to maintain their genome integrity. Among these, the DNA integrity checkpoints play crucial roles by preventing chromosomal rearrangements in response to replication injuries or during unchallenged replication (Kolodner et al., 2002).

In fission yeast, the DNA integrity checkpoints include both the DNA replication checkpoint, which is activated during S-phase in response to replication block, and the G2-DNA damage checkpoint that is activated in G2 in response to DNA lesions. Both checkpoints are dependent on sensors proteins such as the Rad3-Rad26 kinase complex and RFC-like Rad17 complex, which loads the PCNA-like Rad1/Rad9/Hus1 complex at junctions of single-stranded to double-stranded DNA (Caspari and Carr, 1999). In response to replication blocks, activation of the DNA replication checkpoint results in a delay to mitotic entry to prevent catastrophic mitosis (Enoch et al., 1992). In addition, late replication origin firing is actively repressed (Paulovich and Hartwell, 1995; Santocanale and Diffley, 1998; Kim and Huberman, 2001). Importantly, the DNA replication checkpoint also maintains fork integrity, both by preventing replisome dissociation from stalled forks and by maintaining the DNA structures to allow the resumption of DNA synthesis after replication block removal (Lopes et al., 2001; Tercero and Diffley, 2001; Cobb et al., 2003; Lucca et al., 2004; Tercero et al., 2003; Meister et al., 2005).

In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the DNA replication checkpoint signals through the transducer kinase Cds1 via its mediator Mrc1 (Murakami and Okayama, 1995; Lindsay et al., 1998; Alcasabas et al., 2001; Tanaka and Russell, 2001). S. pombe mutants defective in the DNA replication checkpoint exhibit extreme sensitivity to hydroxyurea (HU), a drug that inhibits ribonucleotide reductase and depletes dNTP pools. HU treatment is a common approach to study the response to replication arrest in many organisms. In budding yeast, the checkpoint kinase Rad53 (the homologue of S. pombe Cds1) has been shown to maintain the integrity of active replication forks stalled during HU treatment by preventing the formation of aberrant DNA structures such as regressed, hemi-replicated, or gapped forks (Lopes et al., 2001; Sogo et al., 2002). Abnormal DNA structures have been also observed in fission yeast upon HU treatment in the absence of Cds1 (Meister et al., 2005). Therefore, it is established that the DNA replication checkpoint prevents the “collapse” of active forks, defined as the appearance of pathogenic DNA structures during replication arrest. How this is achieved is largely unknown.

The heterodimer Mus81/Eme1 is a structure-specific endonuclease that is able to cleave branched DNA structures which resemble degenerated forks, nicked Holliday junctions (HJs), 3′ flap extension, and D-loops structures in vitro (Boddy et al., 2001; Doe et al., 2002, 2004; Gaillard et al., 2003; Whitby et al., 2003). However, the ability of Mus81/Eme1 to cleave such substrates in vivo remains poorly described. In fission yeast, Mus81/Eme1 prevents the accumulation of X-shaped structures in a thermosensitive mutant of DNA polymerase alpha (pol alpha), suggesting that Mus81/Eme1 is able to cleave HJs in vivo (Gaillard et al., 2003). The fission yeast Cds1 kinase physically interacts with Mus81 through a forkhead-associated domain (FHA) and this interaction has been shown to negatively regulate Mus81/Eme1 activity (Boddy et al., 2000; Kai et al., 2005). The fission yeast swi7-H4 mutant, a thermosensitive pol alpha allele thought to specifically affect lagging strand DNA synthesis, exhibits a mutator phenotype that results in Mus81-dependent deletion events (Kai et al., 2005). In this context, a mutant of Mus81 that is unable to interact with Cds1 (mus81-T239A) exacerbated the genetic instability, indicating that Cds1 is needed to regulate Mus81 activity in order to preserve genome integrity during replication stress.

Mus81 is found associated with chromatin during unperturbed S-phase (Kai et al., 2005). After HU treatment, Mus81 undergoes Cds1-dependent phosphorylation, leading to Mus81 release from chromatin (Boddy et al., 2000; Kai et al., 2005). In contrast to the situation when combined with the pol alpha mutant, where mus81-T239A exacerbated the mutator phenotype, the mus81-T239A mutant that cannot interact with Cds1 did not show a mutator phenotype upon HU treatment. Instead, it leads to a modest increase in recombination resulting from gene conversion (Kai et al., 2005). These data indicate that Cds1 regulates Mus81 activity in different ways when replication arrest is induced by HU compared with replication perturbation by a polymerase mutant. This raises the question as to the exact nature of Mus81 substrates during different replication arrests in vivo. Because of the structure of known in vitro Mus81 substrates, it is currently thought that Cds1 is required to remove Mus81 from chromatin to prevent inappropriate cleavage of stalled forks. However, the enzymatic cleavage of forks stalled by HU treatment has not yet been reported in fission yeast.

Here, we report that, after HU treatment, the DNA replication checkpoint prevents HU-induced DNA breaks resulting from Mus81 nuclease activity. Because these HU-induced DNA breaks are S-phase specific and do not result from recombination intermediates cleavage, stalled forks are likely the DNA structures cleaved by Mus81 in vivo and resulting in DNA breaks. However, the mus81-T239A mutant did not exhibit HU-induced DNA breaks, showing that Cds1 does not prevent cleavage of stalled forks by regulating Mus81 association with chromatin, but rather by stabilizing the replisome. In addition, we find that the Rqh1 helicase contributes to HU-induced Mus81-dependent DNA breaks formation in a manner independent of Rqh1 helicase activity. Finally, we establish that the DNA-damage checkpoint kinase Chk1 can limit the toxicity of Mus81-dependent breakage of stalled forks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetics and Cell Biology Techniques

Strains used were constructed by standard genetic techniques and are listed in Table 1. Cells were cultured in YES media. Exponentially growing cultures were treated with HU (12 mM final concentration) for the indicated times at 30°C unless otherwise stated. For release experiments, cells were recovered by centrifugation and washed once in water before being diluted in fresh YES media.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strains | Genotype | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| WT | h+ura4-D18, leu1-32, ade6-M216 | D. Beach |

| cds1Δ | h−leu1-32 ura4D18 cds1::ura4+ | P. Nurse |

| mus81Δ | h+mus81::KanR+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | P. Russell |

| cds1Δ mus81Δ | h−cds1::ura4+mus81::KanR+ura4-D18 | G. Baldacci |

| rad3Δ | h−rad3::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | G. Baldacci |

| rad9Δ | h−- rad9::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-704 | G. Baldacci |

| rad17Δ | h−rad17::ura4+leu1-32 ura4D-18 ade6-704 | G. Baldacci |

| mrc1Δ | h−mrc1::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-704 | G. Baldacci |

| crb2Δ | h−crb2::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 | G. Baldacci |

| chk1Δ | h−chk1::ura4+ura4-D18 | D. Beach |

| cds1Δ chk1Δ | cds1::ura4+chk1::ura4+ura4-D18 leu1-32 | G. Baldacci |

| cds1-KD | h−cds1-D312E:2HA6His:ura4 (KD) ura4-D18 leu1-32 | P. Russell |

| mus81-ND | h−mus81D359,360A-TAP:KanMx6 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | P. Russell |

| cds1Δ mus81-ND | mus81D359A-TAP:KanMx6 cds1::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| eme1Δ | h+eme1::KanR+ura4-D18 leu1-32 | P. Russell |

| cds1Δ eme1Δ | eme1::KanR+cds1::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | G. Baldacci |

| cdc25–22 | h−cdc25–22 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 leu1-32 | NCYCa |

| cdc25–22 cds1Δ | h−cdc25–22 cds1::ura4+Ura4-D18 | This study |

| rad22Δ | h+rad22::KanR+ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | A. Carr |

| cds1Δ rad22Δ | cds1::ura4+rad22::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | G. Baldacci |

| rqh1Δ | h−rqh1::ura4+leu1-32 ura4D-18 | G. Baldacci |

| cds1Δ rqh1Δ | rqh1::ura4+cds1::ura4+ura4D-18 leu1-32 | G. Baldacci |

| rqh1K547R | h−rqh1K547R ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | J. Murray |

| rqh1K547A | h−rqh1K547A ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | J. Murray |

| cds1Δ rqh1K547R | h−rqh1K547R cds1::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| cds1Δ rqh1K547A | h−rqh1K547A cds1::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| Mus81:myc | mus81::13myc:kanMx leu1-32 ura4-D18 | P. Russell |

| Mus81T239A:myc | mus81T239A:13myc:kanMx leu1-32 ura4-D18 | P. Russell |

| cds1Δ mus81:myc | mus81:13myc:kanMx cds1::ura4+ura4-D18 leu1-32 | This study |

| cds1Δ Mus81T239A: myc | mus81T239A:13:myc:kanMx cds1::ura4+ura4D-18 leu1-32 | This study |

| Cdc25–22 cds1Δ Chk1-HA | h−cdc25–22 chk1:HA cds1::ura4+ura4D-18 | This study |

| Cdc25–22 cds1Δ mus81Δ Chk1-HA | Cdc25–22 chk1:HA cds1::ura4+mus81:kanR+ura4D-18 | G. Baldacci |

a National Collection of Yeast Cultures, Norwich, United Kingdom.

FACS Staining

Ethanol-fixed cells were treated as described previously (Sazer and Sherwood, 1990). DNA was stained with Sytox green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 1 μM final concentration. Data acquisition was performed on a BD FacsCalibur (BD Biosciences, France).

Pulse-Field Gel Electrophoresis Analysis

Exponential growing cells at a density of 5 × 106 cells/ml were exposed to HU treatment. At the indicated times, samples were collected to prepare agar plugs containing 4 × 107 cells as previously described (Lambert et al., 2005). Pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed using the CHEF Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad, France) for 48 or 60 h in TAE buffer (0.8% agarose, Pulse time: 1800 s, 2 V/cm, angle: 120°). To determine the size of DNA fragments, electrophoresis was performed in 0.5× TBE buffer, 1% agarose, initial switch time 50 s, final switch time 90 s, 6 V/cm, angle: 120°. Agarose gels were stained in 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide for 30 min and photographed, and DNA was transferred onto positively charged nylon membrane using standard techniques. Probes corresponding to ars2-1 and to mtDNA were obtained by PCR using the following primers: 5-AAGCTTTTAGCTAAGGTTCGGTTGTCATTGGATGATACCC-3, 5-AAGCTTCACTCTGTGATAAATTCATGAAAAGAAAACATGA-3, and 5-CGGTCCCGCATGAATGACTT-3, 5-GCTGCCAGGGTCTTTCCGTC-3, respectively (Kim and Huberman, 2001). Quantification was performed using the ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences, France).

Checkpoint Analysis

Synchronous cultures of G2 cells were generated on lactose gradients, as previously described, and divided into two samples (al-Khodairy et al., 1994). One was untreated and one was treated with HU (12 mM) for 7 h at 32°C. Samples were taken every 30 min and were ethanol-fixed. Cells were analyzed by microscopy after DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and Calcofluor staining at 1 and 400 μg/ml, respectively.

RESULTS

S-phase Checkpoint Prevents HU-induced DNA Breaks

To understand the mechanisms underlying the maintenance of genome integrity by the DNA replication checkpoint, we analyzed chromosome integrity by PFGE both during HU arrest and during the recovery phase after release from replication arrest. As expected, the replication intermediates (RI) that accumulate during HU treatment prevented chromosomes prepared from both wild-type (WT) and cds1 null (cds1Δ) cells from migrating into the gel (Figure 1A). One hour after release from HU arrest chromosomes from WT cells migrated normally. Chromosomes prepared from cds1Δ cells were not visible 2 h after release (Figure 1A). Thus, in WT cells, replication was completed within 1 h after HU, whereas RIs persisted in cds1Δ for at least 2 h. These observations are in agreement with the inability of cds1Δ to complete DNA synthesis after replication arrest (Lindsay et al., 1998; Meister et al., 2005).

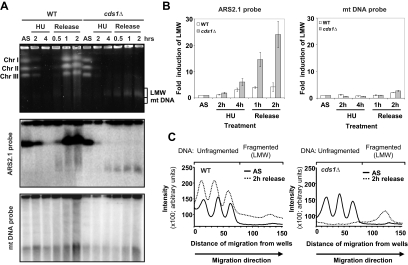

Figure 1.

HU-induced DNA fragmentation in cds1Δ. (A) PFGE analysis of indicated strains during HU block (12 mM) and after release. Top panel, EtBr staining; middle panel, ars2-1 probe; bottom panel, mtDNA probe. The smears observed with EtBr staining in the WT strain are due to increased cell number and mtDNA accumulation during recovery. LMW, low molecular weight; AS, asynchronous cells; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA. (B) Quantification of signals observed with ars2-1 probe (left panel) or mtDNA probe (right panel) using ImageQuant software. Values are the mean of three independent experiments ± SEM. (C) Representation of the intensity of the three chromosomes (unfragmented) and of LMW DNA (fragmented DNA) from asynchronous cells and cells 2 h after release from HU arrest, according to migration distance from wells, using ImageQuant software.

We detected the appearance of a band corresponding to low-molecular-weight (LMW) DNA in cds1Δ cells after 4 h of HU treatment. This band continued to accumulate during the recovery period (Figure 1, A and C). Because this region of the gel also contains the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), we hybridized the PFGE blots with either a probe corresponding to an early replicating origin (ars2-1 from chromosome II) or to mtDNA (Kim and Huberman, 2001). The ars2-1 probe revealed an increased intensity of LMW chromosomal DNA during HU treatment and recovery in DNA prepared from cds1Δ but not WT cells (Figure 1, A and B). The signal corresponding to mtDNA did not vary significantly in either the WT or cds1Δ samples (Figure 1, A and B). We conclude that loss of Cds1 function leads to extensive fragmentation of chromosomes during replication arrest and recovery.

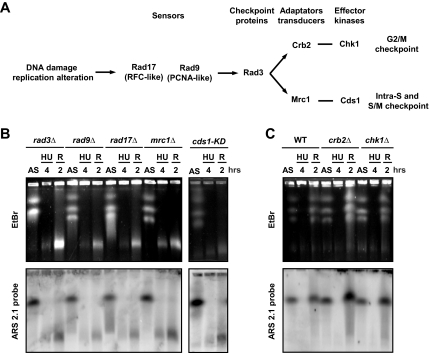

Cds1 activation during HU arrest is dependent on the checkpoint rad gene products and the Mrc1 adaptor protein (Lindsay et al., 1998; Alcasabas et al., 2001; Tanaka and Russell, 2001, 2004; Figure 2A). We therefore analyzed if HU-induced DNA fragmentation occurred in checkpoint mutants other than cds1Δ (Figure 2B). All mutants defective in Cds1 activation after HU treatment exhibited both the absence of chromosome migration and extensive DNA fragmentation during both HU treatment and recovery. Together with the observation that a cds1 kinase dead mutant (cds1-kd) showed equivalent defects, these data indicate that the DNA replication checkpoint activates Cds1 to prevent DNA fragmentation and thus maintain chromosome integrity. In addition, all mutants defective in the S-phase checkpoint exhibiting DNA fragmentation were unable to achieve replication during recovery. In contrast, in the absence of Swi1 that is also involved in S-phase checkpoint and in fork protection (Noguchi et al., 2003; Noguchi et al., 2004) cells were able to achieve replication during recovery but did not exhibit DNA fragmentation (data not shown). Therefore, HU-induced DNA fragmentation appears to be a marked feature of cells unable to resume replication, probably because of their inability to stabilize the replication apparatus. Consistent with this being an S-phase checkpoint–specific function, crb2Δ and chk1Δ mutants, which are defective in the DNA damage checkpoint but proficient in activating Cds1 in response to replication arrest, did not display HU-induced DNA fragmentation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

DNA replication checkpoint prevents HU-induced DNA fragmentation. (A) Schema of the DNA structure checkpoint pathways and proteins implicated in the signaling of DNA damage and perturbations to DNA replication in fission yeast. (B and C) PFGE analysis of indicated strains arrested with HU (12 mM) and released from arrest (R). Top panel, EtBr staining; bottom panel, ars2-1 probe.

HU-induced DNA Fragmentation Is Dependent on Mus81/Eme1

Because Cds1 regulates Mus81 association with chromatin (Kai et al., 2005), we reasoned that HU-induced DNA fragmentation could result from breaks introduced by unregulated Mus81 activity. We analyzed chromosome integrity in samples prepared from HU-treated cds1Δ mus81Δ, cds1Δ mus81-ND (nuclease dead), and cds1Δ eme1Δ double mutant cells. PFGE followed by hybridization with the ars2-1 probe revealed that HU-dependent LMW DNA was not detectable (Figure 3, A–C). Thus, the DNA fragmentation that occurs in the absence of Cds1 is due to DNA breaks resulting directly from Mus81 nuclease activity. However, the double mutant cds1Δ mus81Δ cells failed to restore chromosome integrity during recovery, and FACS analysis indicated that this strain was unable to complete replication (Supplementary Figure S1A). We also verified that HU-induced DNA breaks were independent either of the 3′ flap endonuclease Rad16/Swi10 (homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad1/Rad10) or of the homologue of Rad50/Mre11/Nbs1 complex (data not shown).

Figure 3.

HU-induced DNA fragments are dependent on Mus81/Eme1. (A, C, and D) PFGE analysis of indicated strains arrested with HU (12 mM) and released from arrest (R). Top panel, EtBr staining; bottom panel, ars2-1 probe. (B) Quantification of signals observed with ars2-1 probe using ImageQuant software. Values are the mean of three independent experiments ± SEM.

To establish if Cds1 prevents directly HU-induced DNA breaks by regulating Mus81 association with chromatin, we analyzed DNA fragmentation in a myc-tagged mus81T239A mutant, which is not regulated by Cds1, during HU treatment and release. First, the presence of the myc tag did not affect Mus81 activity because HU-induced DNA breaks were observed in a cds1Δ myc-tagged mus81 (Figure 3D). Second, HU-induced DNA breaks were detectable in a cds1Δ myc-tagged mus81T239A strain, but not in a single myc-tagged mus81T239A mutant, showing that T239A mutation did not affect Mus81 nuclease activity (Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure S1B). Importantly, these results establish that HU-induced DNA breaks can be prevented without Cds1 regulating Mus81 phosphorylation status and that the fact that Mus81 remains chromatin-associated during HU treatment does not lead to DNA breakage. Therefore, we concluded that the DNA replication checkpoint does not prevent directly HU-induced DNA breaks by regulating Mus81 and that at least one additional process is required to produce DNA breakage.

HU-induced DNA fragmentation requires that DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are introduced into the chromosomes by Mus81/Eme1-dependent DNA cleavage. This raises the question as to the exact nature of the DNA structures cleaved by Mus81 upon HU treatment and recovery. The cleavage of 3′ flap extensions by Mus81 would not introduce an additional discontinuity in DNA molecules at replication forks and would therefore not result in DSBs or DNA fragmentation when analyzed by PFGE. We have also established that the HU-induced DNA breaks are not dependent on the S. pombe homologue of S. cerevisiae Rad52 (known as Rad22; Figure 3D). In the absence of Rad22, both Rhp51-dependent (the S. pombe homologue of S. cerevisiae Rad51) and Rhp51-independent recombination pathways are compromised, and strand invasion reactions resulting in D-loop or HJs structures are unlikely to occur (Doe et al., 2004). We were assured also that our rad22Δ background strains did not contain the suppressor fbh1 by testing their sensitivity to HU (Supplementary Figure S1C). We therefore conclude that HU-induced DNA structures cleaved by Mus81 are not recombination intermediates such as D-loops or HJs generated through a Rad22-dependent pathway.

Mus81 Likely Cleaves Stalled/Collapsed Forks

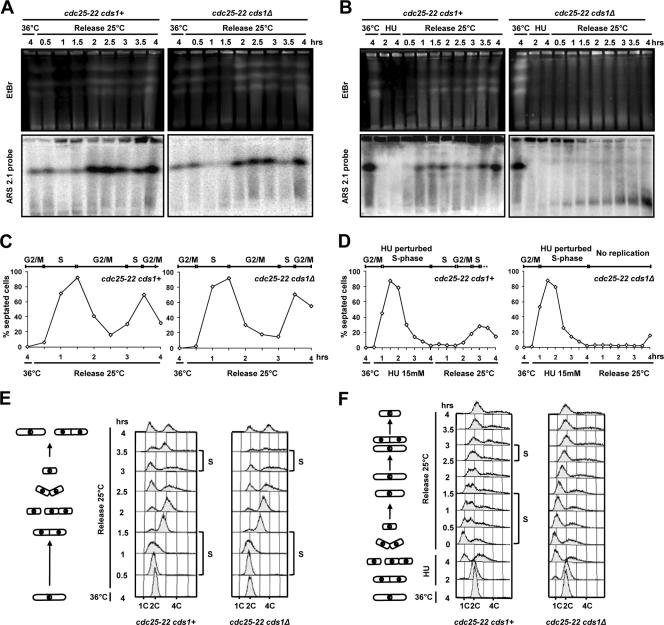

DSBs associated with stalled forks have been observed in several organisms such as bacteria, budding yeast, and mammalian cells (Michel et al., 1997; Saintigny et al., 2001; Lundin et al., 2002; Sorensen et al., 2005). We reasoned that HU-induced DNA breaks could result from cleavage of stalled fork by Mus81/Eme1. We therefore verified that DNA breaks were S-phase specific by analyzing chromosome integrity in G2-synchronized cells released into cell cycle in the presence or absence of HU (Figure 4). cds1+ and cds1Δ cells harboring the thermosensitive mutation cdc25-22 were grown at 36°C for 4 h to synchronize cells in G2 phase. Cells were then released from G2 arrest by incubation at 25°C either in the presence or absence of HU for 4 h. HU-treated cells were allowed to recover in fresh medium without HU for an additional 4 h. Both untreated cds1+ and cds1Δ cells completed replication within 2 h after release from G2 arrest (Figure 4E). No DNA breaks were observed by PFGE without HU treatment (Figure 4, A and C). In contrast, when released into HU containing media, neither cds1+ nor cds1Δ cells were able to complete replication (Figure 4, B and F). However, when HU was removed 4 h later, cds1+ cells completed two rounds of replication within 3.5 h, as judged by PFGE, FACS analysis, and septation index (Figure 4, B, D, and F). In contrast, cds1Δ cells were unable to complete DNA replication, and evidence of DNA breaks was visible as early as 1 h after HU removal (Figure 4, B, D, and F). Importantly, although cells were arrested at G2/M or were in G1-early S-phase (i.e., during the first 2 h of HU block), no significant DNA fragmentation was detected. Taken together, these data demonstrate that HU-induced DNA breaks are S-phase specific and are likely to be associated with stalled forks. Moreover, these data show that all DNA breaks observed in asynchronous cultures treated with HU result from perturbed replications.

Figure 4.

HU-induced DNA breaks are S-phase specific. (A) PFGE analysis of cdc25-22 cds1+ and cdc25-22 cds1Δ strains synchronized in G2 at 36°C for 4 h and released at 25°C for 4 h. Samples were taken at the indicated times. The smears observed with EtBr staining of WT strain are due to increased cell number and mtDNA during recovery. Top panel, EtBr staining; bottom panel, ars2-1 probe. (B) PFGE analysis of cdc25-22 cds1+ and cdc25-22 cds1Δ strains synchronized in G2 at 36°C for 4 h and then incubated at 25°C in presence of HU (15 mM) for 4 h. Cells were then washed into fresh medium (Release) for 4 h. Samples were taken at indicated times. Top panel, EtBr staining; bottom panel, ars2-1 probe. (C and D) Septation index curves of cells from kinetics shown in A and B, respectively. Septum formation occurs once cells have passed mitosis and is concomitant with DNA synthesis in the absence of replication perturbation. (E and F) FACS analysis of cells from kinetics shown in A and B, respectively. The occurrence of DNA synthesis is annotated as S. Cell morphology is drawn on the left part of each panel.

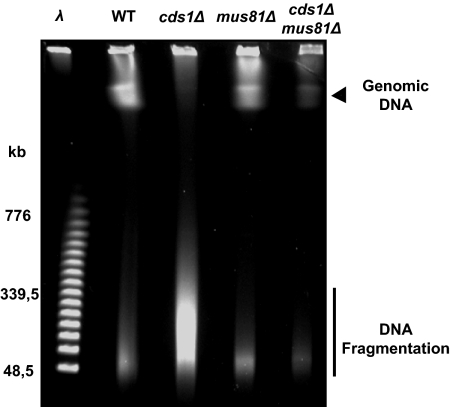

To further characterize the HU-induced DNA fragments, we determined their size by PFGE. The most abundant fragments ranged between 50 and 300 kb (Figure 5). This corresponds to the size distribution of interbubble regions observed during HU-challenged replication in S. pombe (Patel et al., 2006). Occasional gaps of up to 500 kb between active origins have been recently observed (Patel et al., 2006; Heichinger et al., 2006), which would be consistent with the less abundant but larger fragments we observe. Alternatively, not all stalled/collapsed forks may break and the size of HU-induced DNA fragments could correspond to single and multiple replicons. Consistent with this interpretation, Raveendranathan et al. (2006) reported that DNA breakages occur only at some stalled/collapsed forks in budding yeast rad53 mutant cells, which they referred to as compromised early origins (CEOs). Irrespective of whether all or only a subset of forks are susceptible to breakage, our data support a scenario in which HU-induced DNA fragments result from Mus81-dependent fork breakage, allowing unreplicated regions to migrate into the gels as linear fragments.

Figure 5.

Mus81-dependent DNA breaks are likely to occur at collapsed forks. Size determination of HU-induced DNA fragments detected at 2 h after release from HU (12 mM) using PFGE. Molecular weight (λ) corresponds to the Lambda ladder (Bio-Rad) that starts at 48.5 kb and increases by 48.5 kb in each successive band. Fragments migrating around 50 kb in all strains likely correspond to mtDNA.

HU-induced DNA Breaks Require the Rqh1 Protein But Not Its Helicase Activity

In Escherichia coli, the response to replication block includes the cleavage of reversed forks by the RuvABC resolvase (Seigneur et al., 1998). In bacteria, fork reversion can be actively driven by RuvAB, the recombinase RecA, or the helicases RecG or UvrD (Seigneur et al., 2000; McGlynn et al., 2001; Robu et al., 2001; Flores et al., 2004; Baharoglu et al., 2006). In eukaryotes, little is known about the formation of reversed forks. In budding yeast, fork reversion has been demonstrated in rad53 mutant cells during HU treatment (Sogo et al., 2002). In S. cerevisiae, fork reversion is proposed to occur passively, resulting from the migration of a hemicatenate structure formed between the two nascent strands during DNA replication (Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005). In human cells, RecQ helicase homologues such as BLM or WRN are able to promote the regression of replication forks structures in vitro (Machwe et al., 2006; Ralf et al., 2006).

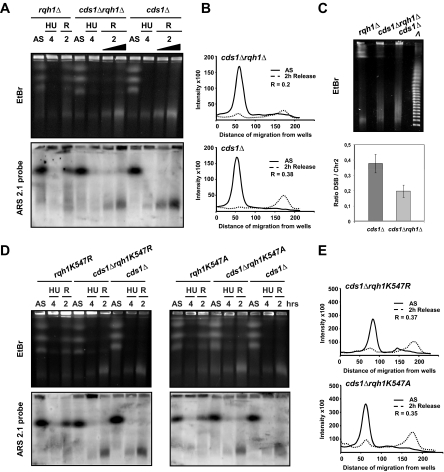

To establish if the S. pombe RecQ homologue, Rqh1, is involved in generating DNA fragmentation during HU treatment of cds1Δ cells (possibly by promoting the formation of HJ-like structures by fork regression, independently of recombination), we tested the occurrence of HU-induced DNA breaks in rqh1Δ, cds1Δ, and rqh1Δ cds1Δ cells after either 4 or 6 h of HU treatment and after release into fresh medium to allow “recovery.” A reduced level of DNA breaks was observed in rqh1Δ cds1Δ cells compared with cds1Δ after 4 h of HU treatment, in a reproductive manner (Figure 6, A–C). Similar observations were obtained by prolonged HU treatment for 6 h (Supplementary Figure S2). Because the background noise associated with PFGE using strains harboring rqh1 mutation is high (possibly because of an elevated level of DNA degradation), quantifying the gels using the method previously described (Figure 1B) proved inconclusive. Similar levels of DNA degradation were observed in other recombination mutants such as Rad22 and Rhp51. Therefore, using the ars2-1 probe on PFGE Southern blots, we quantified chromosome II and presented the signal corresponding to fragmented DNA as a function of distance migrated from the well (Figure 6, B and C). The level of HU-induced DNA breaks after 4 h of HU treatment and release is two fold reduced in cds1Δ rqh1Δ when compared with the cds1Δ single mutant. Unexpectedly, this reduction in HU-induced DNA breakage was not observed in two rqh1 mutants (rqh1K547R and rqh1K547A) that abolish helicase activity in vitro (Laursen et al., 2003; Figure 6, D and E). Thus, HU-induced DNA breaks are partially Rqh1-dependent, but do not require Rqh1 helicase activity.

Figure 6.

HU-induced DNA breaks formation requires Rqh1 but not its helicase activity. (A and D) PFGE analysis of indicated strains during HU arrest (12 mM) and after release from arrest (R). Top panel, EtBr staining; bottom panel, ars2-1 probe. The black triangle means that the cell number was increase by two fold at 2 h release to allow a better comparison between the two strains. (B and E) Quantification (using ImageQuant software) of Southern hybridization (from A and D) of chromosome II and of fragmented DNA probing with ars2-1, plotted as intensity versus migration distance from wells. Representations correspond to 2 h release after 4 h of HU treatment. R corresponds to the ratio between the intensity of fragmented DNA after release from HU block and the intensity of chromosome II from asynchronous cultures. (C) Top panel, size determination of HU-induced DNA fragments detected at 2 h after release from HU (12 mM) using PFGE. Molecular weight (λ) corresponds to the Lambda ladder (Bio-Rad) that starts at 48.5kb and increases by 48.5kb in each successive band. Bottom panel, quantification of the ratio R in indicated strains. Values are the mean of three independent experiments ± SEM.

Mus81-dependent DNA Breakages Contribute to the S-Phase DNA Damage Checkpoint

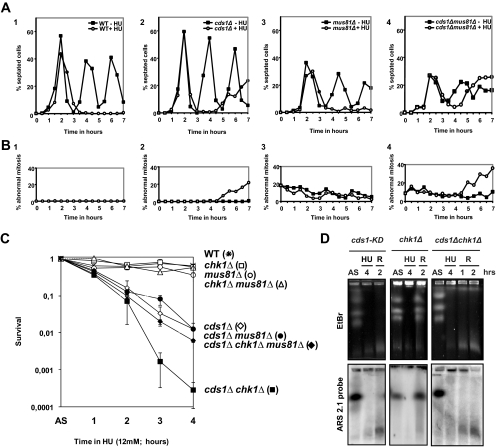

When replication forks collapse, an S-phase–specific DNA damage checkpoint that is Chk1 dependent is activated in S. pombe (Lindsay et al., 1998). This checkpoint shares many common features with the canonical G2-DNA damage checkpoint but also exhibits specific genetic control (Furuya et al., 2004). Conversion of stalled forks into DNA-damage-like structures is thought to activate this checkpoint, resulting in Chk1 activation during S-phase and in a subsequent delay to mitotic entry (Lindsay et al., 1998). Our results strongly suggest that the DNA-damage-like structures that activate the checkpoint correspond to stalled forks cleaved by Mus81. We therefore analyzed HU-induced cell cycle delay in cds1Δ and cds1Δ mus81Δ cells. Both WT and mus81Δ cells were able to delay mitosis entry during the entire HU block (Figure 7A, panels 1 and 3). mus81Δ exhibited a high background level of aberrant mitotic cells (mainly nonseptated cells with eccentric nucleus or without nucleus), but HU treatment did not increase this level (Figure 7B, panels 1 and 3). In contrast, cds1Δ cells were unable to maintain mitotic delay for the duration of the HU treatment and entered into catastrophic mitosis after a 2 h delay (Figure 7, A and B, panel 2). In cds1Δ mus81Δ cells, the delay caused by HU treatment before cells entered into catastrophic mitosis was of only 1 h (Figure 7A, panel 4), and the level of abnormal mitosis present at the end of the experiment was elevated compared with the single cds1Δ mutant (Figure 7B, panels 2 and 4). This effect of mus81Δ on HU-induced cell cycle delay was reproducible in three independent experiments (Supplementary Figure S3A). Thus, in the absence of Cds1, the HU-induced cell cycle delay is partially Mus81 dependent, and Mus81 limits entry into catastrophic mitosis. We conclude that the DNA breaks produced by Mus81 contribute to the maintenance of Chk1-dependent cell cycle arrest when Cds1 is absent. However, a Chk1-dependent arrest does occur that is independent of Mus81. Consistent with this, during HU treatment of synchronized cds1Δ mus81Δ, we can detect the phosphorylated form of Chk1 (Supplementary Figure S3B). A slight delay in Chk1 phosphorylation is observed in cds1Δ mus81Δ cells compared with cds1Δ cells, and this could be explained by the fact that the double mutant progressed slower into cell cycle than cds1Δ (data not shown). However, Chk1 can also be activated and can delay cell cycle progression independently of its phosphorylation status, especially at the metaphase-anaphase transition (Collura et al., 2005). Therefore, we cannot exclude that Mus81 contributes to a Chk1-dependent cell cycle delay in response to HU, without contributing to Chk1 phosphorylation.

Figure 7.

Interplay between Mus81 activity and DNA damage checkpoint. (A) Septation index curves of cells synchronized in G2 by lactose gradient and released into the cell cycle with (12 mM) or without HU. Samples were taken at indicated times and analyzed by DAPI and Calcofluor staining. Each experiment was repeated three times and a typical kinetic is shown. (B) Corresponding percentage of abnormal mitosis (abnormal DNA segregation during mitosis, with or without septum). (C) Survival of different S. pombe strains during short-term exposure to HU treatment (12 mM). (D) PFGE analysis of indicated strains during HU arrest (12 mM) and released from arrest (R). Top panel, EtBr staining; bottom panel, ars2-1 probe.

Chk1 Can Limit Toxicity of Mus81 Activity at Stalled Forks

cds1Δ, but not chk1Δ or mus81Δ cells are sensitive to short-term exposure to HU (al-Khodairy et al., 1994; Murakami and Okayama, 1995; Boddy et al., 2001). However, chk1Δ cds1Δ double mutant cells are more sensitive than cds1Δ single mutant cells (Boddy et al., 1998). We observed that loss of mus81 reduced the extreme sensitivity of the double mutant chk1Δ cds1Δ (Figure 7C). The triple mutant cds1Δ chk1Δ mus81Δ exhibited a limited but clear rescue of sensitivity to short-term exposure to HU, showing survival characteristics similar to the sensitivity of the single cds1Δ mutant. Because HU-induced DNA breaks occur in cds1Δ chk1Δ at the same extend as cds1Δ (Figure 7D), this suggests that Mus81-dependent fork breakage reduces cell viability when both checkpoint are absent. This could be explained by the ability of Chk1 to delay cell cycle to allow repair of stalled fork breakages produced by Mus81. Interestingly, in mammalian cells, Chk1 has been proposed to ensure the efficient repair of broken forks by homologous recombination (Sorensen et al., 2005).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that the DNA replication checkpoint contributes to the maintenance of chromosome integrity by protecting stalled fork and thus preventing unscheduled Mus81-dependent DNA breaks during perturbed DNA synthesis. We show that HU-induced DNA fragments arise only in S-phase and that their size corresponds to the distances between active replication origins. The Mus81/Eme1 complex is a heterodimeric structure-specific endonuclease that, in vitro, is able to cleave branched DNA structures resembling degenerate forks, 3′ flap extensions and recombination intermediates including HJs and D-loop structures (Boddy et al., 2001; Doe et al., 2002, 2004; Gaillard et al., 2003; Whitby et al., 2003; Osman and Whitby, 2007). We have clearly established that Rad22-dependent recombination processes are not required to produce HU-induced DNA breaks, and we can thus exclude that HU-induced DNA fragments result from cleavage of recombination intermediates. Given the similarity of these in vitro substrates to the structures proposed to be present at stalled/collapsed forks, it is reasonable to conclude that arrested forks are in vivo substrates for Mus81/Eme1. Taken together, our data support the view that HU-induced DNA breaks result directly from the cleavage of stalled/collapsed forks by Mus81.

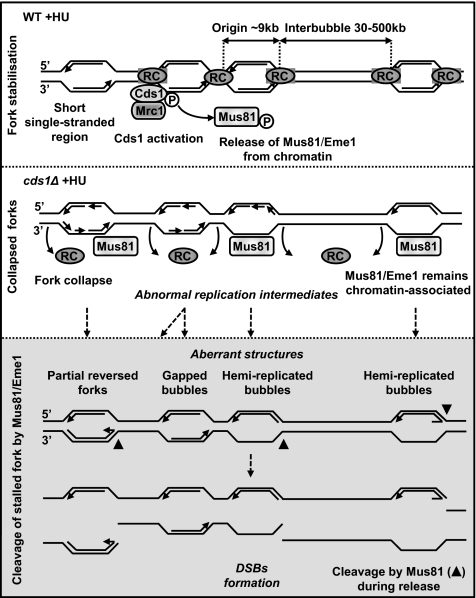

Together with the known mechanism and activities of the replication checkpoint, these data suggest a model in which, in response to HU, short single-stranded regions accumulate at replication forks, leading to a robust Cds1 kinase activity and release of Mus81 from chromatin (Figure 8, top panel). When Cds1 function is absent, the replisome dissociates from the site of nucleotide incorporation and aberrant DNA structures accumulate, resulting in “collapsed” forks (Figure 8, middle panel). Therefore, unprotected stalled forks would be physically accessible to Mus81 and cleaved, resulting in HU-induced DNA breaks. We suggest that replisome dissociation from stalled forks is required to produce Mus81-dependent DNA breaks. First, stalled fork cleavage appears to be a feature of checkpoint mutants unable to restart replication after replication perturbation, likely because of replisome dissociation. Second, Cds1 does not directly prevent HU-induced DNA breaks by regulating Mus81 association with chromatin. This shows that among the processes prevented by Cds1 at least one is required to allow stalled fork cleavage by Mus81. Third, this last result is consistent with the fact that mus81T239A, lacking Cds1-dependent regulation, does not show significant genetic instability in response to HU but exacerbates the genetic instability of a pol alpha mutant (swi7-H4), in which the replisome might be partially destabilized. Indeed, Cds1 is activated in swi7-H4 and Cds1 overexpression suppress the thermosensitivity of this mutant (Murakami and Okayama, 1995; Kai and Wang, 2003), suggesting that the replisome could be somehow unstable in swi7-H4, requiring Cds1 activation to stabilize it. Altogether, these data suggest that Mus81 cleaves unprotected (or destabilized) stalled forks, which are prevented by the DNA replication checkpoint. In this context, the fact that Mus81 remains chromatin-associated could enhance its efficiency in cleaving stalled forks. The exact nature of DNA structures cleaved at stalled forks by Mus81 is still uncertain, but our results clearly indicate that homologous recombination is not required to produce Mus81 substrates at stalled forks. However, HJ-like structures arising through fork regression or degenerated forks resembling known Mus81 substrates in vitro could also occur at stalled forks, independently of recombination.

Figure 8.

Model for HU-induced DNA breaks formation by Mus81 activity. RC: replication complex. See text for details.

The loss of Cds1 leads to the firing of late as well as early replication origins during HU-blocked early S-phase (Feng et al., 2006). It might have been anticipated that Mus81-dependent fork breakage thus would occur immediately upon fork collapse. Our observation that DNA breaks are mainly observed at late times during HU treatment and after HU removal (Figures 1A and 3B) may indicate that Mus81-dependent fork cleavage is a late response to HU treatment, requiring former biological processes. This is consistent with the idea that replisome dissociation would occur before Mus81-dependent cleavage of stalled forks. In addition, unprotected stalled forks may require enzymatic processing by exonucleases or helicases other than Rqh1 before to become suitable substrates for Mus81. Alternatively, the DNA structures cleaved by Mus81 may not be present in HU-blocked early S-phase cells or may be protected from Mus81 by binding of other proteins. In support of this second hypothesis, we have previously shown that Rad22 is recruited at HU-arrested replication forks in the absence of Cds1 (Meister et al., 2005 and our unpublished results) and that aberrant DNA structures, which likely reflect degenerated forks and Mus81 substrates, increase during recovery from HU treatment (Meister et al., 2005). This could provide an explanation as why HU-induced DNA breaks occur mainly during recovery rather than during the HU block.

Synthetic lethality has been observed between Mus81/Eme1 and RecQ helicase mutations in many organisms (Boddy et al., 2000; Kaliraman et al., 2001; Mullen et al., 2001; Trowbridge et al., 2007), suggesting that Mus81/Eme1 and RecQ act in functionally overlapping pathways. In response to stalled forks, it has been suggested that Mus81/Eme1 promotes a recombinogenic pathway, whereas RecQ helicase promotes a nonrecombinogenic pathway to restart replication and/or maintain genetic stability (Osman and Whitby, 2007). Our results suggest that Mus81/Eme1 and RecQ helicase pathways can cooperate when replication forks are arrested by HU treatment: we show that HU-induced DNA breakage is reduced by about two fold in the absence of Rqh1, indicating that efficient Mus81-dependent cleavage of stalled forks requires Rqh1. However, the requirement of Rqh1 is independent of its helicase activity. This excludes the explanation that Rqh1 helicase activity promotes the formation of Mus81 substrates. We suggest that Rqh1 facilitates Mus81-dependent cleavage of stalled forks through physical interactions, possibly helping recruitment of Mus81 to its substrates. Several recent observations support this hypothesis. In response to HU treatment the human RecQ helicase BLM physically interacts and colocalizes in foci with human Mus81 (Zhang et al., 2005). BLM also stimulates Mus81 endonuclease activity on nicked HJs and 3′ flap extension structures in vitro by enhancing the binding of Mus81 to its substrates (Zhang et al., 2005). Because the S. cerevisiae RecQ homologue Sgs1 travels with the replication forks (Cobb et al., 2003), we suggest that fission yeast Rqh1 could either help to recruit or to stabilize Mus81 at stalled forks, therefore facilitating cleavage. Thus, Rqh1 and Mus81 may cooperate in a common pathway to promote the cleavage of stalled forks in absence of Cds1 activity.

In conclusion, our results provide new insights into the control of stalled forks stability by the DNA replication checkpoint pathway. We establish that Cds1 contributes to the maintenance of chromosome integrity during replication arrest by preventing unscheduled DNA breaks resulting from Mus81 activity. We suggest that this is permitted by replisome dissociation that allows physical access of Mus81 activity to stalled forks and is not due to direct regulation of Mus81 by Cds1. These data reveal a novel function for the Cds1 checkpoint kinase in protecting stalled forks from unscheduled nuclease attack. A similar conclusion has been drawn in budding yeast, where Rad53 contributes to the maintenance of DNA integrity at stalled forks by preventing degradation of nascent DNA by the Exo1 nuclease (Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005). Taken together, these data underline the importance of interplay between checkpoint pathways and proteins involved in DNA metabolism at stalled replication forks in maintaining genomic integrity.

While we were submitting this work, Hanada et al. (2007) published data showing that in response to replication inhibition of checkpoint proficient cells, mammalian Mus81 is involved in DSB formation which could substantially allow replication restart (Hanada et al., 2007). Although we cannot conclude that Mus81-dependent DNA breaks allow replication restart in S. pombe, these data are consistent with our conclusion that HU-induced DNA breaks results from stalled fork cleavage by Mus81.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Meister for constructing cds1Δ rad22Δ and cds1Δ mus81Δ strains; P. Russell (Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) for the gift of mus81-ND, eme1Δ and cds1-KD strains; and J. Murray (Genome Damage and Stability Centre, University of Sussex, United Kingdom) for the gift of rqh1K547A and rqh1K547R strains. We thank Tony Carr and Janet Hall for reading the manuscript and comments. We thank all members of the Baldacci lab for helpful discussions. B.F. received a scholarship from the French Ministere de la Recherche et des Technologies. This work was supported in part by Association Pour la Recherche et des Technologies Grant 3471 to G.B. and by Agence Nationale de la Recherche grant ANR-06-BLAN-0271.

Abbreviations used:

- PFGE

pulse-field gel electrophoresis

- HU

hydroxyurea

- HJs

Holliday junctions.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0728) on November 21, 2007.

REFERENCES

- Alcasabas A. A., Osborn A. J., Bachant J., Hu F., Werler P. J., Bousset K., Furuya K., Diffley J. F., Carr A. M., Elledge S. J. Mrc1 transduces signals of DNA replication stress to activate Rad53. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:958–965. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Khodairy F., Fotou E., Sheldrick K. S., Griffiths D. J., Lehmann A. R., Carr A. M. Identification and characterization of new elements involved in checkpoint and feedback controls in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1994;5:147–160. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharoglu Z., Petranovic M., Flores M. J., Michel B. RuvAB is essential for replication forks reversal in certain replication mutants. EMBO J. 2006;25:596–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy M. N., Furnari B., Mondesert O., Russell P. Replication checkpoint enforced by kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Science. 1998;280:909–912. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy M. N., Gaillard P. H., McDonald W. H., Shanahan P., Yates J. R., 3rd, Russell P. Mus81-Eme1 are essential components of a Holliday junction resolvase. Cell. 2001;107:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy M. N., Lopez-Girona A., Shanahan P., Interthal H., Heyer W. D., Russell P. Damage tolerance protein Mus81 associates with the FHA1 domain of checkpoint kinase Cds1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:8758–8766. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8758-8766.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspari T., Carr A. M. DNA structure checkpoint pathways in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biochimie. 1999;81:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb J. A., Bjergbaek L., Shimada K., Frei C., Gasser S. M. DNA polymerase stabilization at stalled replication forks requires Mec1 and the RecQ helicase Sgs1. EMBO J. 2003;22:4325–4336. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collura A., Blaisonneau J., Baldacci G., Francesconi S. The fission yeast Crb2/Chk1 pathway coordinates the DNA damage and spindle checkpoint in response to replication stress induced by topoisomerase I inhibitor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:7889–7899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7889-7899.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta-Ramusino C., Fachinetti D., Lucca C., Doksani Y., Lopes M., Sogo J., Foiani M. Exo1 processes stalled replication forks and counteracts fork reversal in checkpoint-defective cells. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffley J. F., Labib K. The chromosome replication cycle. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:869–872. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe C. L., Ahn J. S., Dixon J., Whitby M. C. Mus81-Eme1 and Rqh1 involvement in processing stalled and collapsed replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32753–32759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe C. L., Osman F., Dixon J., Whitby M. C. DNA repair by a Rad22-Mus81-dependent pathway that is independent of Rhp51. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5570–5581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch T., Carr A. M., Nurse P. Fission yeast genes involved in coupling mitosis to completion of DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2035–2046. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W., Collingwood D., Boeck M. E., Fox L. A., Alvino G. M., Fangman W. L., Raghuraman M. K., Brewer B. J. Genomic mapping of single-stranded DNA in hydroxyurea-challenged yeasts identifies origins of replication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:148–155. doi: 10.1038/ncb1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores M. J., Bidnenko V., Michel B. The DNA repair helicase UvrD is essential for replication fork reversal in replication mutants. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:983–988. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya K., Poitelea M., Guo L., Caspari T., Carr A. M. Chk1 activation requires Rad9 S/TQ-site phosphorylation to promote association with C-terminal BRCT domains of Rad4TOPBP1. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1154–1164. doi: 10.1101/gad.291104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard P. H., Noguchi E., Shanahan P., Russell P. The endogenous Mus81-Eme1 complex resolves Holliday junctions by a nick and counternick mechanism. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:747–759. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada K., Budzowska M., Davies S. L., van Drunen E., Onizawa H., Beverloo H.B., Maas A., Essers J., Hickson I.D., Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81 contributes to replication restart by generating double-strand DNA breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;14:1096–1104. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heichinger C., Penkett C. J., Bahler J., Nurse P. Genome-wide characterization of fission yeast DNA replication origins. EMBO J. 2006;25:5171–5179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai M., Boddy M. N., Russell P., Wang T. S. Replication checkpoint kinase Cds1 regulates Mus81 to preserve genome integrity during replication stress. Genes Dev. 2005;19:919–932. doi: 10.1101/gad.1304305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai M., Wang T. S. Checkpoint activation regulates mutagenic translesion synthesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:64–76. doi: 10.1101/gad.1043203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliraman V., Mullen J. R., Fricke W. M., Bastin-Shanower S. A., Brill S. J. Functional overlap between Sgs1-Top3 and the Mms4-Mus81 endonuclease. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2730–2740. doi: 10.1101/gad.932201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. M., Huberman J. A. Regulation of replication timing in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2001;20:6115–6126. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodner R. D., Putnam C. D., Myung K. Maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2002;297:552–557. doi: 10.1126/science.1075277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S., Carr A. M. Checkpoint responses to replication fork barriers. Biochimie. 2005;87:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S., Watson A., Sheedy D. M., Martin B., Carr A. M. Gross chromosomal rearrangements and elevated recombination at an inducible site-specific replication fork barrier. Cell. 2005;121:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen L. V., Ampatzidou E., Andersen A. H., Murray J. M. Role for the fission yeast RecQ helicase in DNA repair in G2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:3692–3705. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3692-3705.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay H. D., Griffiths D. J., Edwards R. J., Christensen P. U., Murray J. M., Osman F., Walworth N., Carr A. M. S-phase-specific activation of Cds1 kinase defines a subpathway of the checkpoint response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev. 1998;12:382–395. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes M., Cotta-Ramusino C., Pellicioli A., Liberi G., Plevani P., Muzi-Falconi M., Newlon C. S., Foiani M. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucca C., Vanoli F., Cotta-Ramusino C., Pellicioli A., Liberi G., Haber J., Foiani M. Checkpoint-mediated control of replisome-fork association and signalling in response to replication pausing. Oncogene. 2003;23:1206–1213. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin C., Erixon K., Arnaudeau C., Schultz N., Jenssen D., Meuth M., Helleday T. Different roles for nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination following replication arrest in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:5869–5878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5869-5878.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machwe A., Xiao L., Groden J., Orren D. K. The Werner and Bloom syndrome proteins catalyze regression of a model replication fork. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13939–13946. doi: 10.1021/bi0615487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn P., Lloyd R. G., Marians K. J. Formation of Holliday junctions by regression of nascent DNA in intermediates containing stalled replication forks: RecG stimulates regression even when the DNA is negatively supercoiled. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8235–8240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121007798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister P., Taddei A., Vernis L., Poidevin M., Gasser S. M., Baldacci G. Temporal separation of replication and recombination requires the intra-S checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:537–544. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel B., Ehrlich S. D., Uzest M. DNA double-strand breaks caused by replication arrest. EMBO J. 1997;16:430–438. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen J. R., Kaliraman V., Ibrahim S. S., Brill S. J. Requirement for three novel protein complexes in the absence of the Sgs1 DNA helicase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2001;157:103–118. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H., Okayama H. A kinase from fission yeast responsible for blocking mitosis in S phase. Nature. 1995;374:817–819. doi: 10.1038/374817a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi E., Noguchi C., Du L. L., Russell P. Swi1 prevents replication fork collapse and controls checkpoint kinase Cds1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:7861–7874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7861-7874.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi E., Noguchi C., McDonald W. H., Yates J. R., 3rd, Russell P. Swi1 and Swi3 are components of a replication fork protection complex in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:8342–8355. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8342-8355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman F., Whitby M. C. Exploring the roles of Mus81-Eme1/Mms4 at perturbed replication forks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1004–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann K., Lorentz A., Schmidt H. The fission yeast rad22 gene, having a function in mating-type switching and repair of DNA damages, encodes a protein homolog to Rad52 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5940–5944. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P. K., Arcangioli B., Baker S. P., Bensimon A., Rhind N. DNA replication origins fire stochastically in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;17:308–316. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulovich A. G., Hartwell L. H. A checkpoint regulates the rate of progression through S phase in S. cerevisiae in response to DNA damage. Cell. 1995;82:841–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralf C., Hickson I. D., Wu L. The Bloom's syndrome helicase can promote the regression of a model replication fork. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:22839–22846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveendranathan M., Chattopadhyay S., Bolon Y. T., Haworth J., Clarke D. J., Bielinsky A. K. Genome-wide replication profiles of S-phase checkpoint mutants reveal fragile sites in yeast. EMBO J. 2006;25:3627–3639. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robu M. E., Inman R. B., Cox M. M. RecA protein promotes the regression of stalled replication forks in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8211–8218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131022698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saintigny Y., Delacote F., Vares G., Petitot F., Lambert S., Averbeck D., Lopez B. S. Characterization of homologous recombination induced by replication inhibition in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:3861–3870. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santocanale C., Diffley J. F. A Mec1- and Rad53-dependent checkpoint controls late-firing origins of DNA replication. Nature. 1998;395:615–618. doi: 10.1038/27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazer S., Sherwood S. W. Mitochondrial growth and DNA synthesis occur in the absence of nuclear DNA replication in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 1990;97(Pt 3):509–516. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneur M., Bidnenko V., Ehrlich S. D., Michel B. RuvAB acts at arrested replication forks. Cell. 1998;95:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneur M., Ehrlich S. D., Michel B. RuvABC-dependent double-strand breaks in dnaBts mutants require recA. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;38:565–574. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo J. M., Lopes M., Foiani M. Fork reversal and ssDNA accumulation at stalled replication forks owing to checkpoint defects. Science. 2002;297:599–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1074023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen C. S., Hansen L. T., Dziegielewski J., Syljuasen R. G., Lundin C., Bartek J., Helleday T. The cell-cycle checkpoint kinase Chk1 is required for mammalian homologous recombination repair. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:195–201. doi: 10.1038/ncb1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Russell P. Mrc1 channels the DNA replication arrest signal to checkpoint kinase Cds1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:966–972. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Russell P. Cds1 phosphorylation by Rad3-Rad26 kinase is mediated by forkhead-associated domain interaction with Mrc1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32079–32086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercero J. A., Diffley J. F. Regulation of DNA replication fork progression through damaged DNA by the Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint. Nature. 2001;412:553–557. doi: 10.1038/35087607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercero J. A., Longhese M. P., Diffley J. F. A central role for DNA replication forks in checkpoint activation and response. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1323–1336. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge K., McKim K., Brill S. J., Sekelsky J. Synthetic lethality in the absence of the Drosophila MUS81 endonuclease and the DmBlm helicase is associated with elevated apoptosis. Genetics. 2007;176:1993–2001. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.070060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitby M. C., Osman F., Dixon J. Cleavage of model replication forks by fission yeast Mus81-Eme1 and budding yeast Mus81-Mms4. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6928–6935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Sengupta S., Yang Q., Linke S. P., Yanaihara N., Bradsher J., Blais V., McGowan C. H., Harris C. C. BLM helicase facilitates Mus81 endonuclease activity in human cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2526–2531. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.