Abstract

Striated muscle myosin is a multidomain ATP-dependent molecular motor. Alterations to various domains affect the chemomechanical properties of the motor, and they are associated with skeletal and cardiac myopathies. The myosin transducer domain is located near the nucleotide-binding site. Here, we helped define the role of the transducer by using an integrative approach to study how Drosophila melanogaster transducer mutations D45 and Mhc5 affect myosin function and skeletal and cardiac muscle structure and performance. We found D45 (A261T) myosin has depressed ATPase activity and in vitro actin motility, whereas Mhc5 (G200D) myosin has these properties enhanced. Depressed D45 myosin activity protects against age-associated dysfunction in metabolically demanding skeletal muscles. In contrast, enhanced Mhc5 myosin function allows normal skeletal myofibril assembly, but it induces degradation of the myofibrillar apparatus, probably as a result of contractile disinhibition. Analysis of beating hearts demonstrates depressed motor function evokes a dilatory response, similar to that seen with vertebrate dilated cardiomyopathy myosin mutations, and it disrupts contractile rhythmicity. Enhanced myosin performance generates a phenotype apparently analogous to that of human restrictive cardiomyopathy, possibly indicating myosin-based origins for the disease. The D45 and Mhc5 mutations illustrate the transducer's role in influencing the chemomechanical properties of myosin and produce unique pathologies in distinct muscles. Our data suggest Drosophila is a valuable system for identifying and modeling mutations analogous to those associated with specific human muscle disorders.

INTRODUCTION

The myosin molecular motor of striated muscle is a hexameric molecule composed of two myosin heavy chains (MHCs) and four light chains. The N-terminal globular motor domain is a product inhibited ATPase comprised of several communicating domains and functional units (reviewed by Geeves and Holmes, 1999, 2005; Geeves et al., 2005). Alterations to the various domains dramatically affect the biochemical and mechanical properties of the motor in vitro, and mutations that diminish or enhance the molecular performance of myosin in vivo are associated with the pathogenesis of both skeletal and cardiac myopathies (reviewed by Sellers, 1999; Redowicz, 2002; Oldfors et al., 2004; Chang and Potter, 2005; Laing and Nowak, 2005; Tardiff, 2005; Oldfors, 2007). Central to an understanding of myosin-based myopathies is a fundamental appreciation for how depressed or enhanced molecular motor function differentially affects diverse striated muscles.

Among the communicating functional units of myosin is the recently described transducer region (Coureux et al., 2004). Myosin V crystal structures reveal the transducer's central location within the motor domain near the nucleotide binding site. The transducer includes the last three strands of a seven-stranded β-sheet, which undergoes distortion essential for rearrangements within the nucleotide pocket during the ATPase cycle, and the loops and linkers that accommodate the distortion (Coureux et al., 2004). Among the elements of the transducer is hypervariable loop 1, a flexible surface loop shown to influence a wide range of kinetic and mechanical properties of myosin (Kurzawa-Goertz et al., 1998; Sweeney et al., 1998; Clark et al., 2005). The transducer ultimately integrates information from all parts of the motor domain to facilitate efficient conversion of the energy liberated during ATP hydrolysis into force production (Coureux et al., 2004).

In striated muscle, myosin-containing thick filaments drive contraction in an ATP-dependent manner through cyclical interactions with actin-containing thin filaments. The thin filament troponin–tropomyosin regulatory complex inhibits contraction in resting muscle by occluding myosin binding sites on actin (reviewed by Gordon et al., 2000; Brown and Cohen, 2005). On activation, tropomyosin shifts positions in a stepwise manner away from these binding sites, first as a result of Ca2+ binding to troponin and then by myosin cross-bridge binding to actin (McKillop and Geeves, 1993; Vibert et al., 1997; Poole et al., 2006). Initial cross-bridge binding to actin seems to have allosteric effects on thin filaments such that there is a spread of accessible myosin binding sites along the filaments leading to cooperative activation of contraction (reviewed by Tobacman, 1996; Gordon et al., 2000; Moss et al., 2004). Thus, both elevated Ca2+ levels and cross-bridge binding are required for full activation.

Investigations of the functional domains of myosin and the effects of mutations on muscle contractile properties are greatly facilitated by studying the genetically tractable Drosophila melanogaster system. The Drosophila Mhc gene exists as a single copy per haploid genome that encodes all muscle MHCs through alternative splicing of the primary transcript (Bernstein et al., 1983; Rozek and Davidson, 1983; George et al., 1989). Nonlethal mutations located in constitutive exons are expressed in all myosin isoforms of every striated muscle. Consequently, in such mutants, unlike in vertebrate systems possessing complex Mhc multigene families, compensatory up-regulation of nonmutated myosin isoforms cannot occur. Furthermore, changes in striated muscle performance due to developmental or senescent-dependent switches in myosin isoform complements lacking the mutations are impossible.

The effects of particular myosin isoforms on muscle function during aging can be readily studied in Drosophila. Muscles amenable to such analyses include indirect fight (IFM) (Baker, 1976; Magwere et al., 2006) and cardiac muscles (Paternostro et al., 2001; Wolf et al., 2006; Ocorr et al., 2007). IFM function is not required for viability, and Drosophila cardiac function can be dramatically compromised without causing immediate death. Drosophila age in weeks, and they share common mechanisms that determine aging rates and longevity with higher organisms (Parkes et al., 1999; Finch and Ruvkun, 2001; Tatar et al., 2003; Wessells and Bodmer, 2007). Thus, the fly is an extremely powerful model for studying the progression of myosin-related skeletal and cardiac muscle dysfunction.

Two myosin point mutations in the Drosophila Mhc gene, D45 and Mhc5, were localized in proximity to coding regions for loops and linkers of the transducer (Kronert et al., 1999; Montana and Littleton, 2004). These mutations are in Mhc constitutive exons 5 and 4, respectively. Both mutations impair Drosophila flight ability, and they either suppress (D45) or enhance (Mhc5) IFM myofibrillar destruction when combined with certain troponin mutations (Kronert et al., 1999). These findings suggest the amino acid changes differentially alter the fundamental chemomechanical properties of myosin and possibly mimic perturbations in motor function caused by certain myosin-based myopathy mutations. Because every isoform of striated muscle myosin from the two lines possesses the alterations, the mutants are unique tools for examining the pathophysiological responses to perturbed motor function in distinct striated muscles of a single model organism.

Here, we provide the first detailed analysis of the effects of mutations in specific transducer elements on myosin molecular function and on age-related changes in skeletal and cardiac muscles. To identify changes in molecular motor performance, myosin was purified from IFM of wild-type and mutant flies for biochemical and biophysical analyses. Skeletal muscle locomotory function was assessed by evaluating flight abilities of wild-type and transducer mutant flies throughout life. We used electron microscopy to evaluate the consequences of mutant myosin expression on IFM myofibrillar ultrastructure. We additionally investigated the progressive changes in cardiac structure and function as a result of altered motor properties by using high-speed video microscopy and advanced motion detection analysis. Our efforts to define the role of the transducer in determining chemomechanical properties of myosin and in diverse striated muscles demonstrate that Drosophila is useful for investigating the pathogenesis of skeletal and cardiac disorders. Furthermore, our model may serve to identify novel mutations that lead to specific myopathies found in the human population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly Lines and Aging

yw (wild-type), D45, and Mhc5 Drosophila were maintained on a standard yeast-sucrose-agar medium at 25°C. For flight and cardiac muscle studies, newly eclosed flies were collected over an 8-h span. All flies were transferred to fresh vials every 2–3 d over a 5-wk period.

Protein Isolation and Purification

IFM myosin was purified from 1- to 2-d-old yw or mutant flies as described previously (Swank et al., 2001) with the following modifications: 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in distilled H2O was used for all dilutions, and all solution volumes were decreased to 75% of previously published volumes. Purified myosin pellets were resuspended in myosin storage buffer consisting of 0.5 M KCl, 20 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid, pH 7.0, 2 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM DTT. Subsequent biochemical and mechanical experiments were performed immediately after spectroscopic methods (Margossian and Lowey, 1982) for determining myosin concentrations.

ATPase Assays

Myosin ATPase activities were determined using [γ-32P]ATP. Ca2+ ATPase was measured as described previously (Swank et al., 2001). Actin-activated ATPase was determined using chicken skeletal muscle actin (Swank et al., 2003). G-actin was isolated from acetone powder of chicken skeletal muscle according to Pardee and Spudich (1982). F-actin was prepared by adding 1 volume of 10X polymerization buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, 0.5 M KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM ATP) to 9 volumes of G-actin. The working F-actin solution had a concentration of ∼30 μM, so that the amount of nonradioactive ATP added to the reaction mixture was minimized. Actin-activated Vmax and Km values for actin were computed by fitting all data points from multiple preparations of each myosin isoform (wild type [n = 9], D45 [n = 4], or Mhc5 [n = 3]) with the Michaelis-Menten equation. Values were averaged to give mean ± SD. Statistical differences in Vmax and Km between wild-type and mutant myosin isoforms were evaluated using Student's t tests.

In Vitro Motility Assays

In vitro actin sliding velocity was determined according to Swank et al. (2001), with some alterations: 20 mM DTT was used in all solutions of the assay. The 0 salt motility assay buffer/0.4% methyl cellulose/glucose oxidase and catylase (0B/MC/GOC) and 0B/MC/GOC + ATP (0B/MC/GOC with 2 mM ATP added) solutions were diluted to 70% of that used previously. Lower ionic strength elevated levels of continuous movement for the majority of actin filaments. Analysis of captured video sequences was performed as described by Root and Wang (1994), by using the modifications described in Swank et al. (2001). Velocities of 15–20 individual filaments were calculated and recorded from each assay; values from multiple preparations (wild-type [n = 4], D45 [n = 4], or Mhc5 [n = 3]) were averaged to give mean ± SD. Statistical differences in the average velocity of actin filaments driven by wild-type and mutant myosin isoforms were determined by Student's t tests.

Flight Testing

Flight testing of 2-, 7-, 21-, or 35-d-old flies was performed as described in Drummond et al. (1991) and Suggs et al. (2007). Each fly was assigned a flight index (FI) value based on its ability to fly up (6), horizontal (4), downward (2), or not at all (0). The average FI (±SD) for each line was calculated by dividing the sum of the individual FI values by the number of individuals tested (n > 200) at each age point. Statistical testing of age-associated changes in mean FI among groups and within each line was performed as described below for calculating differences in age-dependent changes in cardiac parameters between and within genotypes.

Electron Microscopy of Drosophila IFM

Thoraces from late pupa and 2-d-old female flies were isolated and prepared for transmission electron microscopy according to Cripps et al. (1994). Fixatives and Embed812 resin were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Fort Washington, PA); other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Late pupal and 2-d-old adult samples were examined on a Philips 410 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV. Images were recorded on film and later digitized using an Epson 1640SU PHOTO flatbed scanner. Young adult and some pupal samples were examined with a FEI Tecnai 12 transmission electron microscope operating at 120 kV. Digital images were taken with a TemCam-F214 high-resolution digital camera (TVIPS-Tietz, Gauting, Germany). Microscope magnifications were calibrated using a diffraction grating replica and latex calibration standard (Ted Pella, Redding, CA).

Image Analysis of Semi-intact Heart Preparations

Image analysis of beating, semi-intact heart preparations from 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-wk-old adults was performed according to Ocorr et al. (2007). M-modes were generated using a MatLab (MathWorks, Natick, MA)-based image analysis program (Ocorr et al., 2007). Briefly, a 1 pixel-wide region is defined in a single frame of a high-speed digital movie that encompasses both edges of the heart tube; identical regions are then cut from all consecutive movie frames and aligned horizontally. This provides an edge trace that documents the movement of the heart tube walls in the y-axis over time in the x-axis.

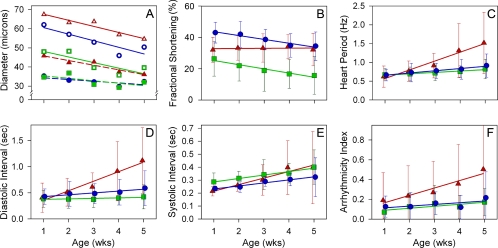

Measurements of diastolic and systolic diameters were made within the third abdominal segment of heart tubes directly from individual video frames. These and other cardiac contractile parameters were obtained as output from the MatLab-based program. Heart periods (HP) are defined as the time between the ends of two consecutive diastolic intervals. The arrythmicity index (AI) was calculated as the standard deviations of all recorded HP for an individual fly normalized to the median HP for that fly. Large standard deviations in HP for a single fly are a reflection of nonuniformly rhythmic contraction/relaxation cycles.

Age-dependent changes in cardiac parameters were modeled hierarchically. For all analyses, values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. Measured parameters included cardiac diameters (diastolic and systolic wall distances), percentage of fractional shortening, HP, diastolic intervals (DIs) and systolic intervals (SIs), and AI. For each fly line, we initially fit a linear model to the mean parameter values from 1 through 5 wk of age. We estimated potential nonlinear change through time using an added sums of squares F-test. For all cardiac parameters, except diastolic distances, there was no strong evidence (p > 0.05) of significant nonlinear change through time. Although diastolic heart wall distance changes with age did reveal statistical evidence of nonlinearity (p = 0.03), the deviation was considered minor; therefore, these and all other response variables were fit with linear models. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test for heterogeneities in the slopes of the fitted lines from each genotype, for each parameter. When significant heterogeneity in slopes was found, we estimated the different functional relationships (slopes) by regression analysis, and we tested for significant change with respect to age. If no significant heterogeneity was found among the slopes, a common slope was estimated via linear regression. We determined whether the common slope, shared among groups, was significant and we performed multiple comparisons among the elevations of the lines to investigate statistical differences between the genotypes. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for genotype as a function of SI was used to test whether significant differences between yw and Mhc5 existed at each of the five age points.

RESULTS

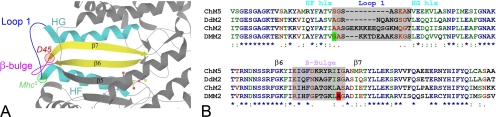

D45 and Mhc5 Mutations Reside within Distinct Transducer Elements

The D. melanogaster Mhc mutants D45 and Mhc5 contain single amino acid conversions previously localized to the vicinity of ATP entry and the ATP binding site on chicken skeletal myosin S1 fragment (Kronert et al., 1999). It was postulated that both mutations affect the ATPase cycle by regulating nucleotide entry or product release from the binding pocket (Kronert et al., 1999). Mapping the point mutations onto chicken myosin V motor domain structures reveals that the specific amino acid alterations reside within distinct structural elements of the transducer region (Figure 1A) (Coureux et al., 2003, 2004). The D45 (A261T) mutation occurs at the junction between the β-bulge and the seventh strand of the central β-sheet, whereas the Mhc5 mutation (G200D) maps close to the junction between the HF helix and loop 1. Sequence comparisons corroborate the locations of the Drosophila mutations relative to specific transducer elements from different organisms (Figure 1B). The alignments also demonstrate the variability found within loop 1 primary structures among various myosin isoforms. The structural elements of the transducer were proposed to interact in a coordinated manner to bring about kinetic tuning of product release after ATP hydrolysis (Coureux et al., 2004). Point mutations within the transducer may alter rates of transitions between states of the actomyosin ATPase cycle and thereby influence chemomechanical transduction in the muscles in which they are expressed.

Figure 1.

Locations of myosin transducer mutations and the alignment and sequence comparison of transducer elements from various myosin isoforms. (A) Ribbon diagram (prepared using the KiNG 1.39 [Kinemage, Next Generation, Durham, NC] interactive system for three-dimensional vector graphics) of a portion of the chicken myosin V (Protein Data Bank code 1W7J) motor domain near the nucleotide (shown as a ball and stick model) binding pocket, with specific components of the transducer region labeled. The locations of D. melanogaster D45 and Mhc5 mutations are shown relative to specific transducer elements. D45 is at the junction between the β-bulge and the seventh strand of the central β-sheet, whereas Mhc5 lies close to the junction between the HF helix and hypervariable loop 1. (B) ClustalW amino acid alignment of specific MHC regions from ChM5, Gallus gallus (chicken) myosin Va; DdM2, Dictyostelium discoideum nonmuscle myosin II; ChM2, G. gallus skeletal muscle myosin II; and DMM2, D. melanogaster muscle myosin II. (*), fully conserved residues; (:), conservation of strong groups; and (.), conservation of weak groups. DMM2 sequences reveal the locations of the Mhc5 (G200D) mutation (green) and the D45 (A261T) mutation (red) relative to specific transducer elements (chicken numbering system). The sequences and designations of the HF helix (hlx), Loop 1, HG hlx, β-strand 6 (β6), β-bulge, and β7 are based on the sequences of key structural elements of chicken myosin V and Dictyostelium myosin II motors as described in Coureux et al. (2004) Supplementary Table 8.

Biochemical and Mechanical Properties of the Mutant Myosin Isoforms

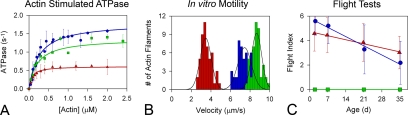

To determine the effects of distinct transducer mutations on the biochemical and molecular mechanical properties of myosin in vitro, we measured Ca2+, Mg2+, and actin-stimulated ATPase activities, determined Km values for actin, and performed in vitro motility assays on the wild-type indirect flight isoform (IFI) and mutant IFM myosin (see Table 1). Basal Ca2+ ATPase activities of purified D45 and Mhc5 myosin were similar to the IFI. However, basal Mg2+ ATPase activity for D45 myosin was about half that of the IFI, whereas basal Mg2+ ATPase activity for Mhc5 myosin was more than twofold higher than for the IFI. Maximum actin-activated ATPase activity (Vmax) (Figure 2A) for D45 myosin was almost threefold lower than that of the IFI, and it was approximately twofold lower than that of Mhc5 myosin. Km, a measure of actin-binding affinity, for either transducer mutant did not differ significantly from that for wild-type myosin. In vitro motility assays (Table 1 and Figure 2B), performed using D45 myosin displayed a reduction in actin filament translocation to about half the velocity of the IFI. Myosin containing the Mhc5 mutation increased actin velocity roughly 15%. Thus, distinct mutations in the transducer region elicit opposing effects on myosin. The D45 mutation depresses the biochemical and mechanical functions of the motor, whereas the Mhc5 mutation enhances them.

Table 1.

Wild-type (IFI) and mutant myosin biochemical and mechanical data

| Ca2+ ATPase (s−1) | Mg2+ ATPase (s−1) | Vmax (s−1) Actin-ATPase | Km, Actin (μM) Actin-ATPase | In vitro motility (μm/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFI | 6.95 ± 1.43 (9) | 0.203 ± 0.063 | 1.83 ± 0.061 | 0.28 ± 0.050 | 7.44 ± 0.73 (4) |

| D45 | 5.42 ± 1.13 (4) | 0.106 ± 0.037* | 0.69 ± 0.077* | 0.30 ± 0.014 | 3.47 ± 0.57* (4) |

| Mhc5 | 5.16 ± 1.17 (3) | 0.482 ± 0.097* | 1.47 ± 0.084* | 0.23 ± 0.014 | 8.69 ± 0.50* (3) |

Values in parentheses denote the number of myosin preparations used to generate mean values for ATPase and in vitro motility assays. SD values are provided for all measured parameters.

* Values are statistically different (p < 0.001) from those obtained for the IFI.

Figure 2.

Effects of myosin transducer mutations on molecular and skeletal muscle function. (A) Steady-state rates of actin-activated myosin ATPase for IFI (●), D45 (▲) and Mhc5 (■) myosin molecules. ATPase results are represented with data fitting lines. Vmax values obtained in actin-stimulated Mg2+ ATPase assays by using D45 myosin are reduced to nearly a third of the values obtained for the IFI, whereas Vmax values for the Mhc5 isoform are slightly reduced compared with that of the IFI. Km values do not differ (see Table 1). (B) Histograms comparing the rates of in vitro actin sliding. Actin sliding velocities for IFI are shown in blue, D45 in red, and Mhc5 in green. Velocity values (see Table 1) were calculated from roughly 50 continuously moving actin filaments compiled from at least three different assays from at least three independent preparations of each myosin isoform. D45 myosin translocates F-actin at a velocity about half that of the IFI. However, Mhc5 myosin drives F-actin movement at a velocity 15% faster than IFI. The average sliding velocities obtained for the three myosin isoforms differ significantly (p < 0.001). See Table 1 for details. (C) Effect of depressed or enhanced myosin motor function on flight ability. FIs were calculated for yw (●), D45 (▲), and Mhc5 (■) at 2 d, 1 wk, 3 wk, and 5 wk of age. Linear regression analysis reveals both yw and D45 exhibited statistically significant (p < 0.05) age-dependent decreases in flight ability. ANCOVA analysis showed significant (p < 0.05) heterogeneity in rates (slopes) of flight ability loss over time with the rate of FI decrease being significantly higher in yw flies compared with D45.

Effects of Mutant Myosin on Skeletal Muscle Function

Because the D. melanogaster transducer is conserved in every striated muscle myosin isoform, we investigated the effects of depressed or enhanced molecular motor function on distinct muscles with differing physiological roles and properties. We assessed skeletal muscle function by evaluating age-dependent changes in flight ability. Wild-type (yw) flies expressing IFI myosin showed a characteristically rapid and steady decline in flight ability from 2 d through 5 wk of age (Figure 2C). Over 35 d, there was an ∼60% overall decrease in FI. In addition to exhibiting an ∼20% reduction in initial flight ability, relative to yw, D45 flies also showed a significant decrease in FI over the 35-d period. However, the rate of decline was less and the overall decrease was only ∼30%, which was markedly lower than wild type. Thus, hypoactive flight muscle myosin expressed in D45 flies provided protection against normal age-dependent muscle dysfunction. Conversely, flies expressing hyperactive Mhc5 myosin showed no flight ability at any age.

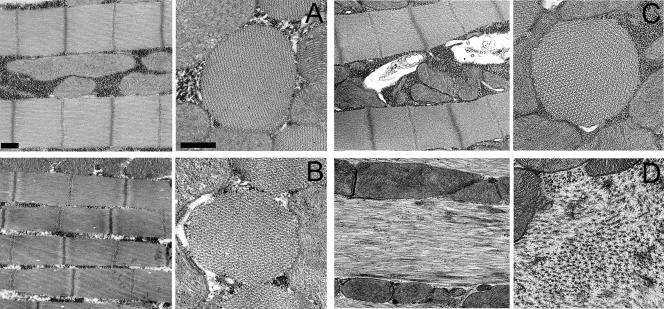

Effects of Mutant Myosin on Skeletal Muscle Ultrastructure

To ascertain whether expression of myosin with depressed or enhanced ATP hydrolytic and mechanical properties produced ultrastructural abnormalities within skeletal muscles, we examined the IFM by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 3, A–D). Longitudinal and transverse sections revealed that D45 myosin expression (Figure 3B) did not disrupt the assembly or integrity of myofibrils within the IFM, because their general appearance closely resembled that of yw myofibrils (Figure 3A). Sarcomeric structure in both lines seemed highly organized with easily discernible Z-lines, I-bands, A-bands, H-zones, and M-lines. In cross section, yw and D45 myofibrils displayed the normal, crystalline-like double hexagonal array of myofilament packing. Myofibrils containing the Mhc5 isoform seem to have assembled normally, as shown by longitudinal and cross sections through late pupae (Figure 3C). By 2 d after eclosion, however, adult Mhc5 IFM displayed a dramatic disarray of contractile filaments with a loss of sarcomeric structure and integrity of Z-lines, I-bands, A-bands, H-zones, and M-lines (Figure 3D). This is reminiscent of the IFM phenotype arising from unregulated cross-bridge cycling and excessive force production (Beall and Fyrberg, 1991).

Figure 3.

Ultrastructure of IFM myofibrils from flies expressing IFI and mutant myosin isoforms. (A) Longitudinal section (left) of wild-type IFM myofibrils at 2 d after eclosion displays easily discernible sarcomeric M-lines and I-, A-, and Z-band structures. Cross section (right) of yw myofibrils shows the characteristic double hexagonal array of thin and thick filaments. Bars, 500 nm. (B) Myofibrils from a fly expressing the hypoactive D45 isoform at 2 d after eclosion seem very similar to those from wild-type IFM in both longitudinal and cross sections. The formation and stability of myofibrils seems normal, with no visible disorganization. (C) Mhc5 late pupa possesses myofibrils that seem to have assembled normally into well-organized structures. (D) IFM myofibrils from an adult expressing the hyperactive Mhc5 isoform at 2 d after eclosion. Severe disruption and disorganization of sarcomeric material is observed. Myofibrillar destruction may be due to excessive actomyosin interactions initiated upon wing movement.

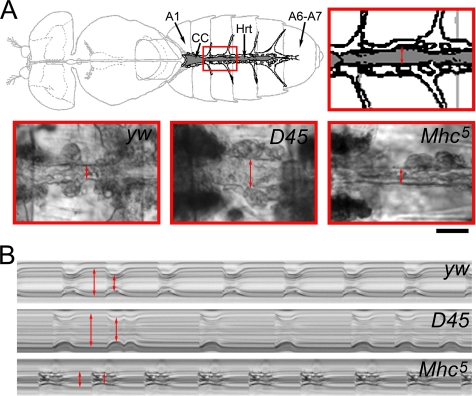

Morphological and Functional Effects of Mutant Myosin Activity on Cardiac Muscle

To investigate the effects of depressed or enhanced myosin motor function on cardiac muscle, we surgically exposed, imaged, and tracked beating heart wall movements of semi-intact flies by using direct immersion differential interference contrast optics in conjunction with a high speed digital video camera (see Supplemental Movies 1–3). Visual inspection of the ventral aspect of the heart tubes at 10× magnification revealed obvious differences in mutant cardiac morphology as early as 1 wk after eclosion. Hearts expressing hypoactive D45 myosin seemed considerably dilated compared with wild-type heart tubes (Figure 4A). The D45 heart walls also qualitatively displayed compromised shortening abilities and thus perturbed systolic function. Hyperactive Mhc5 myosin expression induced a narrowing of the heart tubes with obvious restricted regions. These restricted segments seemed unable to adequately relax, and they severely perturbed diastolic function. The restricted region was initially confined to abdominal segment three in several Mhc5 hearts from 1- to 2-wk-old flies. Subsequently, there seemed to be a lateral spread of restriction gradually affecting abdominal segments 2 and 4 of the heart tubes. The overall incidence of the phenotype increased with advancing age such that by 5 wk nearly all hearts showed some sign of restriction and impaired diastolic function.

Figure 4.

Wild-type and mutant heart morphology and function. (A) Top, schematic of the D. melanogaster heart tube, located along the dorsal midline of the abdomen, and the supportive alary muscles (modified from Miller, 1950). Hrt, Drosophila heart tube; A1, abdominal segment 1; A6–A7, abdominal segments 6 and 7; and CC, conical chamber of the heart tube. Abdominal segment three of the heart tube is outlined in red and enlarged to demonstrate the region analyzed via motion detection software. The double-headed arrow delineates the heart walls. Bottom, images of A3 heart segments of yw, D45, and Mhc5 hearts captured during systole. Note similar systolic wall distances (double-headed red arrows) of yw and Mhc5 heart tubes compared with the dilated systolic distance of the D45 tube. Bar, 50 μm. (B) M-mode traces showing cardiac cycle dynamics of 3-wk-old yw, D45, and Mhc5 hearts. These reveal the locations and movements of the heart walls over a 5-s time period. Note fairly regular heart periods and rhythmicities of yw and Mhc5 heart tubes. However, the extent of diastolic relaxation and fractional shortening seems severely abnormal in Mhc5 compared with yw hearts. Mhc5 systolic intervals are prolonged. D45 hearts show dilated systolic and diastolic distances between heart walls and reduced fractional shortening. Additionally, the D45 cardiac contraction cycles show an arrhythmic pattern with alternating extended and decreased heart periods.

High-speed videos of contracting heart tubes were used to generate M-mode traces at 3 wk of age (Figure 4B), the age where AIs become increasingly divergent among fly lines (see below; Ocorr et al., 2007). These traces qualitatively display the dynamics of cardiac contractions. M-modes from semi-intact 3-wk-old yw and Mhc5 heart preparations show fairly regular contractions. However, the rhythmic beating pattern progressively worsened with age. By 5 wk, both lines exhibited nonrhythmical heart contractile patterns, which included asystoles and fibrillations, reflected by increased AI (see below). In contrast to yw and Mhc5 flies, M-mode records from 3-wk D45 mutant hearts exhibited abundantly more nonrhythmical beating patterns (Figure 4B). Consistent with a substantial AI increase over time (see below) the incidence of arrhythmias became more prevalent by 4 and 5 wk of age in the D45 mutants compared with the other lines.

To confirm the qualitative differences seen among the genotypes, we quantitatively compared the senescent-dependent changes in a number of cardiac parameters from wild-type and mutant hearts. Heart diameters at 1 through 5 wk of age were measured from individual video frames at peak diastolic and systolic time points. All three genotypes exhibited significant decreases in both diastolic and systolic dimensions with age, reflecting a narrowing of the cardiac chamber (Figure 5A). At every age point studied, however, D45 heart walls showed increased mean diastolic and systolic distances, whereas Mhc5 displayed only decreased diastolic diameters relative to wild type. Both wild-type and Mhc5 hearts showed an age-related decrease in fractional shortening, with Mhc5 hearts displaying severely compromised ejection abilities throughout life compared with control hearts (Figure 5B). Fractional shortening for D45 hearts was substantially perturbed at younger ages, relative to that of wild-type hearts; yet, the tubes showed no overall age-related decrease in contractility.

Figure 5.

Analysis of age-dependent changes in physiological parameters of yw (●), D45 (▲), and Mhc5 (■) hearts. Measurements were made on 28–33 hearts from each Drosophila line at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 wk of age. The means were jittered to facilitate SD comparison. Mean values for each genotype were fit with a linear function and color coded so changes with age could be easily compared. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. (A) The mean diastolic and systolic diameters are denoted by open or closed symbols, respectively. Solid lines denote diastolic diameter changes, whereas dotted lines reflect systolic diameter changes, with age. All genotypes showed the same significant rate of mean diastolic diameter decrease with age. However, D45 diastolic heart diameters were significantly greater, whereas Mhc5 values were significantly less than for yw over all age points. There were no significant differences in mean systolic dimensions between yw and Mhc5 hearts over time. Both lines showed identical significant age-dependent decreases in systolic diameter. The mean systolic diameter of D45 hearts was significantly greater than that of yw hearts and the rate of diameter decrease with age was higher for the mutant. (B) Percentage of fractional shortening decreased significantly with age and at the same rate for both yw and Mhc5 hearts; the extent of overall shortening was significantly less for Mhc5 hearts. D45 hearts showed no significant age-dependent change in fractional shortening. (C) Both yw and Mhc5 flies displayed the same significant increase in HP with age. The rate and extent of increase for D45 flies were significantly higher than for control flies. (D) yw and Mhc5 hearts had significant increases in DI, which with age, increased overall at the same rate and to the same extent. D45 hearts exhibited a significantly greater age-dependent increase in DI compared with wild type. (E) yw and Mhc5 hearts showed identical, significant age-related rate increases in SI. The linear function for Mhc5 SI, however, was significantly elevated with respect to yw. A week-by-week ANOVA confirmed significantly longer mean SI for Mhc5 hearts at every age point, relative to yw. SI for D45 hearts also showed an age-associated increase that took place at a significantly higher rate than that for yw hearts. (F) AI for yw and Mhc5 hearts increased significantly over time, at the same rate, and to the same extent. The AI for D45 hearts also increased significantly with age, but it increased by a significantly larger amount over time compared with control hearts.

We characterized the inherent myogenic contractile dynamics and properties of semi-intact hearts by measuring several cardiac parameters from movies of wild-type and mutant flies from 1 through 5 wk of age. The mean HPs of both yw and Mhc5 flies increased moderately and significantly with age (Figure 5C). In contrast, flies expressing hypoactive D45 myosin exhibited a dramatic and highly significant age-dependent increase in HP compared with age-matched controls. Separating HPs into individual DIs and SIs revealed distinct differences between yw and Mhc5 age-dependent cardiac dynamics (Figure 5, D and E). Over the 5-wk time period, no significant differences were found between DI increases in wild-type and Mhc5 hearts. Hearts from both lines showed similar significant rate increases in SI; however, at all five age points the Mhc5 mean SI was significantly longer than that for yw. Thus, the increase in Mhc5 SI substantially contributed to the prolonged HP seen with advancing age in these mutants. D45 hearts showed significant increases in both DI and SI, a hallmark of failing myocardium. The highly prolonged DI for older D45 hearts was predominately responsible for the progressive and dramatic increase in HP of these mutants.

To explore senescent-dependent increases in heart rhythm irregularities, we compared the AIs of the three lines (Figure 5F). In both wild-type and Mhc5 flies, the AI increased progressively, with no significant differences in rates or overall amounts. The AI for D45 mutant hearts was roughly the same as for control flies at 1 wk of age, and then it increased considerably and significantly compared with control flies, throughout life. Thus, the incidence of arrhythmic cardiac beating patterns increased with age in both wild type and in the mutants, but the extent of increase was much greater in D45 flies.

As discussed below, diminished molecular motor function of D45 myosin in our model system seemed to induce a cardiac phenotype similar to that found in humans with dilated cardiomyopathy (Fatkin and Graham, 2002; Ahmad et al., 2005; Chang and Potter, 2005). Enhanced molecular properties of Mhc5 myosin, however, generated pathological hallmarks seemingly analogous to those found in patients suffering from the clinically rare restrictive cardiomyopathy (Kushwaha et al., 1997; Fatkin and Graham, 2002; Ahmad et al., 2005).

DISCUSSION

Here, we have demonstrated that the myosin transducer is intimately involved with determining the motor's biochemical and mechanical properties and hence the structure and performance of striated muscles. The Drosophila transducer is encoded by constitutively expressed exons so that mutations likely alter the kinetic and mechanical properties in a similar manner in all fly striated muscle motors. Therefore, Drosophila is a valuable model system to explore dysfunction of multiple muscles resulting from enhanced or depressed motor activity. This is particularly beneficial because similar alterations in myosin performance are associated with the development and age-related progression of numerous skeletal and cardiac myopathies found in higher organisms (Sellers, 1999; Redowicz, 2002; Oldfors et al., 2004; Chang and Potter, 2005; Laing and Nowak, 2005; Tardiff, 2005; Oldfors, 2007).

The Mhc5 mutation maps close to the junction between the HF helix and hypervariable loop 1, a critical element of the transducer. Biochemical and structural studies of wild-type and engineered myosins have shown loop 1 to be involved in kinetic tuning of the motor by influencing a wide range of myosin activities (Kurzawa-Goertz et al., 1998; Sweeney et al., 1998; Clark et al., 2005). The size and flexibility of loop 1 can affect the rate of ATP hydrolysis, product release, actin filament translocation, access to the nucleotide pocket and nucleotide binding affinity (Sweeney et al., 1998). Larger and more flexible loops were shown to enhance product release (Sweeney et al., 1998). The Mhc5 transducer mutation may straighten the C-terminal segment of the HF helix and increase the length and/or flexibility of loop 1, thereby enhancing the molecular motor's properties.

The D45 transducer mutation is located at the β-bulge/β-strand 7 junction and leads to depressed motor activity. Structural studies showed the transducer's loops and linkers interact with each other and undergo coupled distortions to accommodate the distortion of the central β-sheet that occurs during the ATPase cycle (Coureux et al., 2003, 2004). The D45 mutation may disrupt vital interactions between distinct transducer elements, disturbing the coordinated distortion of the mutant transducer and the resulting sequential release of products from the nucleotide-binding pocket during force generation (Coureux et al., 2004).

The altered motor activity of the Drosophila mutants affected skeletal muscle locomotory function. At young ages, perturbed motor function decreased or eliminated flight ability in D45 or Mhc5 flies, respectively. Both wild-type and D45 flies displayed a characteristic age-dependent reduction in flight ability. Such reductions correlate with declines in glycogen levels and in mitochondrial efficiency and with low myofibrillar protein turnover rates and increased levels of oxidative damage to proteins and lipids (Baker, 1976; Magwere et al., 2006). Protein oxidation, which leads to inactivation of certain enzyme systems and to structural protein damage, is considered critical for the aging process (Stadtman, 1992; Levine and Stadtman, 2001; Magwere et al., 2006). Thus, extreme physical activity, like flight, poses an inherent, deleterious threat to muscle function. Expression of D45 myosin with depressed motor function may diminish IFM contraction rates and flight capacity, and also metabolic demands, metabolic by-product accumulation, and associated oxidative damage to proteins and lipids of muscle cells. Therefore, the functional decline normally associated with IFM may be decelerated by hypoactive myosin, and in general, motors with diminished molecular properties could provide age-dependent protection in demanding muscles that normally operate at very high contraction rates.

Electron microscopic examination of D45 IFM revealed that depressed myosin activity does not perturb IFM sarcomeric structure. In contrast, although Mhc5 IFM expressing myosin with enhanced molecular function developed normally in the pupa, sarcomeric structure was suddenly destroyed in an apparent use-initiated manner in newly eclosed adults. The ultrastructural phenotype of Mhc5 IFM seems similar to that found in the hypercontracted IFM of hdp2 troponin mutants; both phenotypes have been suggested to result from altered actomyosin interactions (Beall and Fyrberg, 1991; Nongthomba et al., 2003; Montana and Littleton, 2004). hdp2 IFM thin filaments exhibit perturbed contractile regulation by troponin-tropomyosin such that myosin binding sites remain unblocked in both the absence and presence of activating Ca2+ (Cammarato et al., 2004). Thus, cross-bridge cycling and force generation would proceed uninhibited and may initiate IFM hypercontraction. Similarly, enhanced kinetic and mechanical properties of Mhc5 myosin may induce excessive cross-bridge cycling and promote cooperative and constitutive activation of thin filaments and force generation. Consequently the contractile system would remain fully activated and, as with hdp2 IFM, which are incapable of relaxing, the fibers could quickly destroy themselves and flight ability would be lost.

Expression of D45 myosin with diminished biomechanical properties produced a Drosophila cardiac phenotype displaying structural and functional characteristics remarkably similar to those found in humans with, and in vertebrate models of, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (Fatkin and Graham, 2002; Ahmad et al., 2005; Chang and Potter, 2005; Schmitt et al., 2006; Debold et al., 2007). DCM is a myocardial disorder characterized by left and/or right ventricular dilation and distended chambers (Fatkin and Graham, 2002; Ahmad et al., 2005; Chang and Potter, 2005). Cardiac contractility is depressed, resulting in systolic dysfunction, reduced fractional shortening, and diminished ejection fractions. Affected individuals demonstrate progressive symptoms and gradually develop heart failure, often associated with life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias.

At least 30% of DCM cases are genetic in origin, with more than 15 autosomal dominant missense mutations localized to the β-cardiac Mhc gene (Kamisago et al., 2000; Ahmad et al., 2005; Chang and Potter, 2005). Disrupted contractile performance of the diseased myocardium may result from alterations in the mutant myosin's ability to generate force and motion (Schmitt et al., 2006; Debold et al., 2007). Mouse models engineered with DCM-causing β-cardiac MHC mutations reproduced morphological and functional characteristics consistent with the human phenotype (Schmitt et al., 2006). At the molecular level, the mutations depressed ATPase activities, in vitro actin filament sliding velocities, and/or maximal force generating capacity of myosin motors (Schmitt et al., 2006; Debold et al., 2007). Depressing one or more of these molecular indices of myosin function was considered sufficient to trigger the cascade of events that lead to DCM (Debold et al., 2007). Our analysis of D45 Drosophila mutants corroborates this hypothesis. D45 myosin showed substantial decreases in basal and actin-stimulated ATPase rates, and a significant drop in actin sliding velocity. The hearts in turn developed a dilated morphology and functional deficits that worsened with age, consistent with DCM. Thus, the pathological response to depressed motor function seems to be surprisingly similar to that found in higher organisms.

Additional studies have demonstrated a dilatory cardiac response in Drosophila resulting from an N-terminal mutation in the TnI inhibitory troponin subunit of the regulatory complex (Wolf et al., 2006). This Drosophila cardiac response is consistent with an N-terminal DCM-causing mutation in human cardiac TnI (cTnI) (Murphy et al., 2004; Wolf et al., 2006). Drosophila may, therefore, serve as a powerful model for investigating an apparently conserved age-associated cascade of events and cardiac remodeling that occur in response to altered myosin or troponin function that result in specific cardiomyopathies.

In vertebrates, some hypertrophic cardiomyopathy myosin mutations have been shown to increase motor ATPase activities, actin sliding velocities, and/or maximal force generating capacities, suggesting the molecular defects result in a gain of myosin function (Fatkin and Graham, 2002; Ahmad et al., 2005; Debold et al., 2007). Thus, augmented biophysical properties of individual myosin motors potentially initiate hypertrophic cardiac remodeling. Drosophila heart tubes, however, expressing Mhc5 myosin with enhanced biomechanical properties exhibited a cardiac phenotype displaying structural and functional characteristics remarkably similar to those in human restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM). RCM is a rare myocardial disorder characterized by cardiac remodeling, decreased myocardial wall elasticity, impaired diastolic ventricular filling, and elevated systemic and pulmonary venous pressures (Kushwaha et al., 1997; Fatkin and Graham, 2002; Ahmad et al., 2005). Cardiac rhythmicity, systolic function, and myocardial wall thickness seem unaffected; however, stroke volume and cardiac output are reduced as a result of diastolic dysfunction and restricted filling. The prognosis for RCM patients is poor in that the majority of them experience progressive deterioration of cardiac function and heart failure with a high incidence of premature mortality.

Six missense cTnI mutations were identified in patients with autosomal dominant RCM (Mogensen et al., 2003). Reconstituted troponin complexes with RCM cTnI were unable to properly inhibit actomyosin ATPase (Gomes et al., 2005). Replacing endogenous cTnIs with the RCM cTnIs, in skinned cardiac fibers revealed elevated levels of basal force production (Gomes et al., 2005; Yumoto et al., 2005). Furthermore, relative to wild-type, the RCM cTnI mutations significantly increased the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development in skinned cardiac fibers. The impaired myocardial relaxation seen in RCM patients was proposed to result from an inability of the mutant troponin complex to properly inhibit basal ATPase and force development at low Ca2+ concentrations (Gomes et al., 2005). A recent study on membrane intact cardiomyocytes expressing an RCM cTnI mutation indeed resulted in thin filament disinhibition and a Ca2+-independent precontracted basal state (Davis et al., 2007).

Our Mhc5 results suggest that increased motor function could also be involved in RCM development. Enhanced kinetic and mechanical activity of this myosin, consistent with inducing IFM hypercontraction, probably promotes excessive cross-bridge cycling in the mutant hearts. Cross-bridge binding physically impedes troponin-tropomyosin regulatory strand movement back to its blocking position on thin filaments and it increases the affinity of troponin for Ca2+, especially in cardiac muscle (Tobacman, 1996; Moss et al., 2004; Hinken and Solaro, 2007). Enhanced myosin cycling may therefore cooperatively promote its own activity by disproportionately increasing the number of available binding sites on actin and by enhancing the Ca2+ sensitivity of the system. Consequently, this could promote the onset of systole and delay relaxation and diastole, prolonging the systolic interval. Mhc5 hearts displayed significantly prolonged systolic intervals, similar to those in children with heart failure secondary to RCM (Friedberg and Silverman, 2006). Thus, excessive actin–myosin interactions caused by enhanced motor activity, heightened Ca2+ sensitivity, and/or thin filament disinhibition, possibly initiating high levels of basal tension and extended systolic intervals, may be major determinants of the diastolic dysfunction seen in Mhc5 hearts, and they are likely key components in the pathogenesis of RCM. Myosin mutations have never been associated with the development of RCM. However, because impaired myosin or TnI function induces an apparently evolutionarily conserved dilatory response in the Drosophila model system, myosin mutations that enhance motor properties should also be considered legitimate candidates in the etiology of the clinically rare RCM.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Douglas Deutschman (San Diego State University) and Douglas M. Swank (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute) for help with statistical analysis, Chi Lee (San Diego State University) for technical assistance, and Mary C. Reedy (Duke University) for helpful comments and discussions regarding manuscript preparation. This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Western States Affiliate of the American Heart Association and National Institutes of Health (NIH) research supplement AR-43396-S1 (to A.C.), NIH grant R01 AR-43396 and NIH grant R01 GM-32443 (to S.I.B.), and NIH grants R01 HL-54732 and P01 AG-15434 (to R.B.).

Abbreviations used:

- AI

arrythmicity index

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- DI

diastolic interval

- FI

flight index

- HP

heart period

- IFI

indirect flight isoform

- IFM

indirect flight muscle

- MHC

myosin heavy chain

- RCM

restrictive cardiomyopathy

- SI

systolic interval

- Tn

troponin.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0890) on November 28, 2007.

REFERENCES

- Ahmad F., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. The genetic basis for cardiac remodeling. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2005;6:185–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker G. T., 3rd Insect flight muscle: maturation and senescence. Gerontology. 1976;22:334–361. doi: 10.1159/000212147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall C. J., Fyrberg E. Muscle abnormalities in Drosophila melanogaster heldup mutants are caused by missing or aberrant troponin-I isoforms. J. Cell Biol. 1991;114:941–951. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.5.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein S. I., Mogami K., Donady J. J., Emerson C. P., Jr Drosophila muscle myosin heavy chain encoded by a single gene in a cluster of muscle mutations. Nature. 1983;302:393–397. doi: 10.1038/302393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. H., Cohen C. Regulation of muscle contraction by tropomyosin and troponin: how structure illuminates function. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;71:121–159. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)71004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarato A., Hatch V., Saide J., Craig R., Sparrow J. C., Tobacman L. S., Lehman W. Drosophila muscle regulation characterized by electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction of thin filament mutants. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A. N., Potter J. D. Sarcomeric protein mutations in dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail. Rev. 2005;10:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R., Ansari M. A., Dash S., Geeves M. A., Coluccio L. M. Loop 1 of transducer region in mammalian class I myosin, Myo1b, modulates actin affinity, ATPase activity, and nucleotide access. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30935–30942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504698200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coureux P. D., Sweeney H. L., Houdusse A. Three myosin V structures delineate essential features of chemo-mechanical transduction. EMBO J. 2004;23:4527–4537. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coureux P. D., Wells A. L., Menetrey J., Yengo C. M., Morris C. A., Sweeney H. L., Houdusse A. A structural state of the myosin V motor without bound nucleotide. Nature. 2003;425:419–423. doi: 10.1038/nature01927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps R. M., Becker K. D., Mardahl M., Kronert W. A., Hodges D., Bernstein S. I. Transformation of Drosophila melanogaster with the wild-type myosin heavy-chain gene: rescue of mutant phenotypes and analysis of defects caused by overexpression. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:689–699. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Wen H., Edwards T., Metzger J. M. Thin filament disinhibition by restrictive cardiomyopathy mutant R193H troponin I induces Ca2+-independent mechanical tone and acute myocyte remodeling. Circ. Res. 2007;100:1494–1502. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000268412.34364.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debold E. P., Schmitt J. P., Patlak J. B., Beck S. E., Moore J. R., Seidman J. G., Seidman C., Warshaw D. M. Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy mutations differentially affect the molecular force generation of mouse alpha-cardiac myosin in the laser trap assay. Am. J. Physiol. 2007;293:H284–H291. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00128.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond D. R., Hennessey E. S., Sparrow J. C. Characterisation of missense mutations in the Act88F gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1991;226:70–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00273589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatkin D., Graham R. M. Molecular mechanisms of inherited cardiomyopathies. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:945–980. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch C. E., Ruvkun G. The genetics of aging. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2001;2:435–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg M. K., Silverman N. H. The systolic to diastolic duration ratio in children with heart failure secondary to restrictive cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2006;19:1326–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeves M. A., Fedorov R., Manstein D. J. Molecular mechanism of actomyosin-based motility. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1462–1477. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeves M. A., Holmes K. C. Structural mechanism of muscle contraction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:687–728. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeves M. A., Holmes K. C. The molecular mechanism of muscle contraction. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;71:161–193. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)71005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George E. L., Ober M. B., Emerson C. P., Jr Functional domains of the Drosophila melanogaster muscle myosin heavy-chain gene are encoded by alternatively spliced exons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:2957–2974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A. V., Liang J., Potter J. D. Mutations in human cardiac troponin I that are associated with restrictive cardiomyopathy affect basal ATPase activity and the calcium sensitivity of force development. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30909–30915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M., Homsher E., Regnier M. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:853–924. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinken A. C., Solaro R. J. A dominant role of cardiac molecular motors in the intrinsic regulation of ventricular ejection and relaxation. Physiology. 2007;22:73–80. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisago M., et al. Mutations in sarcomere protein genes as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1688–1696. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronert W. A., Acebes A., Ferrus A., Bernstein S. I. Specific myosin heavy chain mutations suppress troponin I defects in Drosophila muscles. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:989–1000. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzawa-Goertz S. E., Perreault-Micale C. L., Trybus K. M., Szent-Gyorgyi A. G., Geeves M. A. Loop I can modulate ADP affinity, ATPase activity, and motility of different scallop myosins. Transient kinetic analysis of S1 isoforms. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7517–7525. doi: 10.1021/bi972844+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha S. S., Fallon J. T., Fuster V. Restrictive cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:267–276. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing N. G., Nowak K. J. When contractile proteins go bad: the sarcomere and skeletal muscle disease. Bioessays. 2005;27:809–822. doi: 10.1002/bies.20269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. L., Stadtman E. R. Oxidative modification of proteins during aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwere T., Pamplona R., Miwa S., Martinez-Diaz P., Portero-Otin M., Brand M. D., Partridge L. Flight activity, mortality rates, and lipoxidative damage in Drosophila. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006;61:136–145. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margossian S. S., Lowey S. Structural and contractile proteins. In: Cunningham L. W., Frederiksen D. W., editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 85. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- McKillop D. F., Geeves M. A. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1, evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys. J. 1993;65:693–701. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. The internal anatomy and histology of the imago of Drosophila melanogaster. In: Demerec M., editor. Biology of Drosophila. New York: Wiley; 1950. pp. 420–534. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen J., Kubo T., Duque M., Uribe W., Shaw A., Murphy R., Gimeno J. R., Elliott P., McKenna W. J. Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy is part of the clinical expression of cardiac troponin I mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:209–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI16336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana E. S., Littleton J. T. Characterization of a hypercontraction-induced myopathy in Drosophila caused by mutations in Mhc. J. Cell Biol. 2004;164:1045–1054. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R. L., Razumova M., Fitzsimons D. P. Myosin crossbridge activation of cardiac thin filaments: implications for myocardial function in health and disease. Circ. Res. 2004;94:1290–1300. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127125.61647.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R. T., Mogensen J., Shaw A., Kubo T., Hughes S., McKenna W. J. Novel mutation in cardiac troponin I in recessive idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2004;363:371–372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nongthomba U., Cummins M., Clark S., Vigoreaux J. O., Sparrow J. C. Suppression of muscle hypercontraction by mutations in the myosin heavy chain gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2003;164:209–222. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocorr K., Reeves N. L., Wessells R. J., Fink M., Chen H. S., Akasaka T., Yasuda S., Metzger J. M., Giles W., Posakony J. W., Bodmer R. KCNQ potassium channel mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias in Drosophila that mimic the effects of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3943–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609278104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfors A. Hereditary myosin myopathies. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2007;17:355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfors A., Tajsharghi H., Darin N., Lindberg C. Myopathies associated with myosin heavy chain mutations. Acta Myol. 2004;23:90–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee J. D., Spudich J. A. Structural and contractile proteins. In: Cunningham L. W., Frederiksen D. W., editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 85. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 164–179. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes T. L., Hilliker A. J., Phillips J. P. Motorneurons, reactive oxygen, and life span in Drosophila. Neurobiol. Aging. 1999;20:531–535. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternostro G., Vignola C., Bartsch D. U., Omens J. H., McCulloch A. D., Reed J. C. Age-associated cardiac dysfunction in Drosophila melanogaster. Circ. Res. 2001;88:1053–1058. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. J., Lorenz M., Evans G., Rosenbaum G., Pirani A., Craig R., Tobacman L. S., Lehman W., Holmes K. C. A comparison of muscle thin filament models obtained from electron microscopy reconstructions and low-angle X-ray fibre diagrams from non-overlap muscle. J. Struct. Biol. 2006;155:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redowicz M. J. Myosins and pathology: genetics and biology. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2002;49:789–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root D. D., Wang K. Calmodulin-sensitive interaction of human nebulin fragments with actin and myosin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12581–12591. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozek C. E., Davidson N. Drosophila has one myosin heavy-chain gene with three developmentally regulated transcripts. Cell. 1983;32:23–34. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J. P., et al. Cardiac myosin missense mutations cause dilated cardiomyopathy in mouse models and depress molecular motor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14525–14530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606383103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers J. R. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. Myosins. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman E. R. Protein oxidation and aging. Science. 1992;257:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1355616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suggs J. A., Cammarato A., Kronert W. A., Nikkhoy M., Dambacher C. M., Megighian A., Bernstein S. I. Alternative S2 hinge regions of the myosin rod differentially affect muscle function, myofibril dimensions and myosin tail length. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;367:1312–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank D. M., Bartoo M. L., Knowles A. F., Iliffe C., Bernstein S. I., Molloy J. E., Sparrow J. C. Alternative exon-encoded regions of Drosophila myosin heavy chain modulate ATPase rates and actin sliding velocity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15117–15124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank D. M., Knowles A. F., Kronert W. A., Suggs J. A., Morrill G. E., Nikkhoy M., Manipon G. G., Bernstein S. I. Variable N-terminal regions of muscle myosin heavy chain modulate ATPase rate and actin sliding velocity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17475–17482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney H. L., Rosenfeld S. S., Brown F., Faust L., Smith J., Xing J., Stein L. A., Sellers J. R. Kinetic tuning of myosin via a flexible loop adjacent to the nucleotide binding pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6262–6270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff J. C. Sarcomeric proteins and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: linking mutations in structural proteins to complex cardiovascular phenotypes. Heart Fail. Rev. 2005;10:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M., Bartke A., Antebi A. The endocrine regulation of aging by insulin-like signals. Science. 2003;299:1346–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1081447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacman L. S. Thin filament-mediated regulation of cardiac contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1996;58:447–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibert P., Craig R., Lehman W. Steric-model for activation of muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:8–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessells R. J., Bodmer R. Age-related cardiac deterioration: insights from Drosophila. Front. Biosci. 2007;12:39–48. doi: 10.2741/2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. J., Amrein H., Izatt J. A., Choma M. A., Reedy M. C., Rockman H. A. Drosophila as a model for the identification of genes causing adult human heart disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1394–1399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507359103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumoto F., et al. Drastic Ca2+ sensitization of myofilament associated with a small structural change in troponin I in inherited restrictive cardiomyopathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;338:1519–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.