Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, integral plasma membrane proteins destined for degradation and certain vacuolar membrane proteins are sorted into the lumen of the vacuole via the multivesicular body (MVB) sorting pathway, which depends on the sequential action of three endosomal sorting complexes required for transport. Here, we report the characterization of a new positive modulator of MVB sorting, Ist1. We show that endosomal recruitment of Ist1 depends on ESCRT-III. Deletion of IST1 alone does not cause cargo-sorting defects. However, synthetic genetic analysis of double mutants of IST1 and positive modulators of MVB sorting showed that ist1Δ is synthetic with vta1Δ and vps60Δ, indicating that Ist1 is also a positive component of the MVB-sorting pathway. Moreover, this approach revealed that Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 compose two functional units. Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 form specific physical complexes, and, like Did2 and Vta1, Ist1 binds to the AAA-ATPase Vps4. We provide evidence that the ist1Δ mutation exhibits a synthetic interaction with mutations in VPS2 (DID4) that compromise the Vps2-Vps4 interaction. We propose a model in which the Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 complexes independently modulate late steps in the MVB-sorting pathway.

INTRODUCTION

The multivesicular body (MVB) sorting pathway directs the down-regulation of proteins such as cell surface receptors by sorting these membrane proteins into vesicles that bud into the endosomal lumen. On fusion of late endosomes/MVBs with the vacuole (the yeast equivalent of the lysosome), these vesicles and their associated cargo proteins are delivered to the lumen of the vacuole. In yeast, this process sorts both endocytic and biosynthetic cargo proteins to the vacuole. Plasma membrane proteins can be down-regulated via endocytosis and MVB pathway-dependent vacuolar degradation. Monoubiquitination of membrane cargo proteins appears to be the major sorting signal in the MVB pathway (reviewed in Hicke and Dunn, 2003; Katzmann et al., 2002).

MVB sorting has implications in several human disease–related processes, including carcinogenesis and viral budding (reviewed in Saksena et al., 2007) and Katzmann et al., 2002). Down-regulation of signaling receptors such as EGFR requires the proper function of the MVB pathway (Katzmann et al., 2002; Raiborg et al., 2003), and enveloped viruses such as HIV hijack the MVB-sorting machinery for budding from the plasma membrane, a process that is topologically equivalent to budding into MVBs (Demirov and Freed, 2004; Morita and Sundquist, 2004). MVB-sorting studies, particularly those aimed at the identification of new components, often use the budding yeast S. cerevisiae as a model because of the ease of yeast genetic manipulation. These studies are also very applicable to human biology, as both the mechanisms by which the pathway proceeds and the components involved appear to be well conserved from yeast to humans (reviewed in Saksena et al., 2007; Katzmann et al., 2002; Hurley and Emr, 2006; Williams and Urbe, 2007).

Almost all of the protein components that function in the MVB-sorting pathway were originally identified in yeast genetic screens for mutants defective in vacuolar protein sorting (vps mutants; Saksena et al., 2007 and Hurley and Emr, 2006). Mutants identified in these screens that lack MVB pathway components have subsequently been grouped together as “class E” vps mutants based on the formation of an aberrant enlarged endosomal compartment called a class E compartment (Raymond et al., 1992).

MVB sorting is initiated by binding of the Vps27-Hse1 complex to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate on endosomal membranes and subsequently to ubiquitin on endosomal cargo proteins (Katzmann et al., 2003). Vps27-Hse1 then initiates the sequential endosomal recruitment of three endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT-I, -II, and -III), which function to sort cargo into vesicles that ultimately bud into the lumen of the MVB (reviewed in Saksena et al., 2007; Babst, 2005; Hurley and Emr, 2006; Slagsvold et al., 2006; Williams and Urbe, 2007). ESCRT-III is unique among these protein complexes in that its core components Vps20, Snf7, Vps2 (also known as Did4), and Vps24 are monomeric in the cytosol. Once recruited to the endosomal membrane, they form two subcomplexes: Vps20-Snf7 and Vps2-Vps24 (Babst et al., 2002a). The Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex recruits the AAA (ATPase associated with a variety of cellular activities)-ATPase Vps4 to endosomes (Babst et al., 2002a) via a recently characterized interaction between the MIT (microtubule interacting and trafficking) domain of Vps4 and the MIM (MIT-interacting motif) of Vps2 (Obita et al., 2007). Vps4 forms a multimeric (probably dodecameric) complex by coassembly with Vta1, a regulator that also stimulates the ATPase activity of the Vps4 complex (Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006; Lottridge et al., 2006). The Vps4 complex acts late in the MVB-sorting pathway, releasing ESCRT-III components from the endosomal membrane back into the cytoplasm so that additional sorting cycles can occur (Babst et al., 1998).

In yeast, the core components of the MVB-sorting machinery are Vps27-Hse1, the proteins that form the three ESCRT complexes, and Vps4. In addition, there are more peripherally associated proteins that may play somewhat less essential roles in the pathway, including the positive modulators Mvb12, Did2, Vta1, and Vps60. Although Mvb12 is an ESCRT-I subunit that modulates interactions with ESCRT-II (Chu et al., 2006; Curtiss et al., 2007; Oestreich et al., 2007), Did2, Vta1, and Vps60 likely are recruited and function much later in the MVB-sorting pathway. Did2 is a modulator of ESCRT-III dissociation from endosomes by Vps4 and is recruited by the Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex of ESCRT-III (Nickerson et al., 2006). The Vps4-activating protein Vta1 is thought to be recruited to endosomes by Vps4 itself and coassembles into the Vps4 complex (Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006). Vps60 is largely uncharacterized, but it could potentially be recruited by Vps4 along with Vta1, as it has been shown to bind to Vta1 in vivo (Bowers et al., 2004; Shiflett et al., 2004; Azmi et al., 2006). In this study, we report the identification and characterization of Ist1, a novel positive component of the MVB-sorting pathway that forms a complex with Did2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Strains and Plasmid Construction

Standard techniques and media were used for yeast and bacterial manipulations. Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The Longtine method (Longtine et al., 1998) was used to introduce gene deletions and epitopes into yeast by homologous recombination. Plasmids used in this work are described in Supplementary Table 2. Cloning of each gene was performed as described in Supplementary Table 2 by PCR from SEY6210 genomic DNA unless otherwise indicated using KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Novagen, Madison, WI) and subsequent ligation into the designated expression vector with T4 DNA ligase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD). The cloning vectors pRS415 (see Supplementary Table 2) and pRS416 (see below) are described in Sikorski and Hieter (1989). Fluorescent protein fusion vectors pBP73-C and pBP88-A2 were generous gifts from Dr. William Parrish (The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY). Briefly, pBP73-C is pRS416 with the CPY1 promoter cloned at SacI-XbaI and GFP at XbaI-BamHI. The mRFP fusion vector pBP88-A2 is pRS416 with the ADH1 promoter cloned at SacI-XbaI and mRFP at XbaI-BamHI. The bacterial expression vector pGEX6P-1 is from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ); pET-23b and pET-23d are from Novagen. To create the bacterial GST-Ist1 expression vector pSM7, a PCR fragment containing IST1 lacking its intron was generated using a 5′ primer that contained the entire first exon of IST1 and annealed to the sequence at the beginning of the second exon and a 3′ primer that annealed to the 3′ end of IST1. To prevent annealing of the 5′ primer to multiple sites in IST1, pSR65 [IST1 and its promoter cloned into pRS415 at NotI(5′)-XhoI(3′)] digested with NotI and BglII to remove the first exon was used as a template for this PCR reaction. The coding regions of all plasmids were completely sequenced to ensure that no mutations were introduced in the cloning process.

Microscopy

Living cells expressing fluorescent fusion proteins were grown in minimal media to an A600 of 0.3–0.6. Some were stained with FM4-64 as previously described for visualization of the vacuolar membrane or class E compartment (Vida and Emr, 1995). Microscopy was performed using a fluorescence microscope (DeltaVision RT; Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) equipped with fluorescein isothiocyanate and rhodamine filters. Images were captured with a digital camera (Cool Snap HQ; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and deconvolved using softWoRx 3.5.0 software (Applied Precision).

Subcellular Fractionation

Twenty A600 equivalents of yeast cells were spheroplasted and lysed in 4.3 ml ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1 mM AEBSF, 0.1 mM chymostatin, 1 μM pepstatin A, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete EDTA-free, Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Aliquots of lysates (1 ml) were precleared for 5 min at 500 × g and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to generate pellet (P13) and supernatant (S13) fractions. The S13 fraction (1 ml) was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C in a Beckman TL-100 ultracentrifuge (Fullerton, CA), resulting in the S100 and P100 fractions. Protein samples from each fraction were TCA-precipitated and acetone-washed. Fractions and 5% input controls were resolved on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and immunoblotted using monoclonal antibodies against the control proteins 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK, mAb 22C5, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), alkaline phosphatase (ALP, mAb 1D3, Invitrogen), and Pep12 (mAb 2C3, Invitrogen). An anti-FLAG mAb (M2, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used for detection of tagged Ist1.

Electron Microscopy

Samples were prepared and processed exactly as described in Efe et al. (2005).

Protein Expression and Purification

BL21(DE3)pLys cells (Novagen) transformed with protein expression plasmids were grown at 37°C to an A600 of 0.8. Protein expression was induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM for all plasmids except GST-Did2 (0.3 mM) and incubation at 25°C for 5 h. For cells expressing glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins, cell pellets were resuspended in PBS lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete EDTA-free, Roche) and lysed by sonication. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation (45 min, 10,000 × g), and GST-tagged proteins were purified using glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). After two washes with buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) and two washes with buffer B (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol), GST fusion proteins were eluted with buffer C (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 10 mM reduced glutathione, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol).

For cells expressing His6 fusion proteins, cell pellets were resuspended in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl) with protease inhibitors and lysed by sonication. Lysates were clarified, and proteins were purified using Ni-NTA agarose (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). After several washes in buffer D (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM imidazole), bound proteins were eluted with buffer E (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 250 mM imidazole). Eluted proteins were dialyzed into PBS and fusion protein purity was determined by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Pulldown Assays

After dialysis, recombinant proteins were incubated with 100 μl of 50% Ni-NTA beads or 50% glutathione Sepharose beads (depending on the tag) for 2 h at 4°C in 500 μl of binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Tween 20), except for Vps4-His6, where the binding buffer was 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1% Triton X-100. Protein-conjugated beads were then washed three times with binding buffer, and equal amounts of purified potential binding proteins were added. Samples were incubated at 4°C for 12 h. Unbound proteins were collected by centrifugation, TCA-precipitated, acetone-washed, and resuspended in 50 μl of Laemmli buffer. After protein-conjugated beads were extensively washed with binding buffer, bound proteins were eluted in 50 μl of buffer C or E (see above). Bound and unbound proteins were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and visualized by Coomassie staining.

RESULTS

Identification of Ist1 as a Potential Component of the MVB Sorting Pathway

Cargo sorting–based yeast genetic screens have been used to identify 17 of the 18 class E VPS genes known to be directly involved in MVB sorting (Bankaitis et al., 1986; Rothman and Stevens, 1986; Raymond et al., 1992, Kranz et al., 2001; Bilodeau et al., 2002; Odorizzi et al., 2003; Chu et al., 2006), and these efforts have undoubtedly uncovered most if not all of the major players in the MVB pathway. However, one limitation of these screens is that they could potentially fail to identify two classes of relevant mutants: 1) mutants that are lacking positive modulators but have little to no phenotype, and 2) mutants lacking negative modulators of MVB sorting, which would have no phenotype in screens designed to identify genes that play a positive role in sorting. Therefore, we used a bioinformatics-based approach to find new potential components of the MVB pathway. All known MVB pathway components (both core and peripheral proteins) are at least partially endosome-localized. Therefore, we took advantage of the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD; Hong et al., 2007), which lists 39 characterized and uncharacterized endosome-localized proteins, most of which were identified in a screen that systematically analyzed the localization of ∼4100 GFP-tagged proteins (Huh et al., 2003). Of these, only 12 have no well-characterized function to date. Looking at the information on SGD, one protein, Ist1/Ynl265cp, had three characteristics that made it attractive as a candidate regulator of MVB sorting. First, it was recently identified as a potential binding partner of Vps4, the AAA-ATPase responsible for catalyzing the release of ESCRT components (Krogan et al., 2006). Second, according to the SMART database (Schultz et al., 1998; Letunic et al., 2006), Ist1 has a predicted coiled-coil domain in its C terminus (aa 262-298), a domain found in many class E Vps proteins, particularly in components of ESCRT-III and its peripherally associated proteins. Finally, like virtually all known proteins in the MVB pathway, the amino acid sequence of Ist1 is well conserved from yeast to humans (25% identity, 44% similarity). Put together, the information available about Ist1 led us to hypothesize that it could play a role in MVB sorting.

We used the Longtine method (Longtine et al., 1998) to create a strain expressing a genomic Ist1-GFP fusion in our strain background, SEY6210. The Ist1-GFP fusion protein is functional based on complementation of synthetic double mutant phenotypes described below (data not shown). The endosomal localization of Ist1-GFP was tested by fluorescence microscopy in strains coexpressing the endosomal marker mRFP-FYVEEEA1 or the Golgi marker Sec7-dsRed. The Ist1-GFP fusion protein clearly colocalized with mRFP-FYVEEEA1-positive punctae but not with Sec7-dsRed–positive punctae, indicating that Ist1 does indeed localize to endosomes (Figure 1A). Ist1 is not exclusively endosomal, however, as a cytoplasmic pool of Ist1-GFP was also visible. To confirm the endosomal localization of Ist1 biochemically, we performed subcellular fractionation using a strain in which Ist1 is genomically tagged with FLAG (Figure 1B). As controls, we immunoblotted these fractions for three additional proteins: the t-SNARE Pep12, which localizes to endosomes and Golgi; ALP, a vacuole membrane-resident alkaline phosphatase; and PGK, a cytosolic kinase. As observed with ESCRT-III components (Babst et al., 2002a), Ist1-FLAG runs larger than its predicted size (∼46 kDa instead of ∼37 kDa), most likely because of its highly charged nature. Ist1-FLAG was detected predominantly in the P13 (late endosome/vacuole) and S100 (cytosol) fractions by immunoblotting, consistent with the presence of both endosomal and cytosolic pools of Ist1.

Figure 1.

Ist1 is an endosomal protein that requires Vps27 and Vps4 for proper localization. (A) Endogenous Ist1 was C-terminally tagged with GFP by genomic integration. The resultant fusion protein colocalizes with a plasmid-expressed endosomal marker mRFP-FYVEEEA1 (see arrows) but not with the Golgi marker Sec7-dsRed. (B) Subcellular fractionation was performed on lysates from a wild-type strain and a strain in which endogenous Ist1 was tagged with FLAG. Ist1 was visualized by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG antibody, and marker proteins Pep12, ALP, and PGK were detected by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for these proteins. The asterisk denotes a background band. (C) Localization of chromosomally expressed Ist1-GFP in wild-type, vps27Δ, and vps4Δ strains labeled with FM4-64. Arrows indicate class E compartments..

If Ist1 is indeed a modulator of the MVB-sorting pathway, we would expect that its localization would be dependent on the presence of class E Vps proteins. We therefore tested whether the localization of Ist1-GFP is affected in mutants lacking Vps27 and Vps4. Vps27 binds to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and to ubiquitinated cargo on endosomes and recruits the ESCRT-I complex to endosomal membranes, thereby initiating the MVB-sorting pathway (Katzmann et al., 2003). In vps27Δ mutant cells, most ESCRT proteins are mislocalized to the cytoplasm because Vps27 is required to recruit these proteins from the cytoplasm to the endosomal membrane (Katzmann et al., 2003; and our unpublished results). Like these ESCRT components, Ist1 has a clear requirement for Vps27 for its endosomal localization: Ist1-GFP was predominantly mislocalized to the cytoplasm in vps27Δ mutant cells, although a few small punctae were still visible (Figure 1C).

The AAA-ATPase Vps4 functions at a late step in the MVB-sorting pathway to release ESCRT components from the endosomal membrane. In cells lacking functional Vps4, class E Vps proteins that normally cycle on and off of endosomes are trapped on the endosomal membrane in an enlarged class E compartment (Babst et al., 1998). The lipophilic endocytic tracer dye FM4-64 is routinely used to identify the class E compartment (Vida and Emr, 1995). Ist1-GFP was trapped in an FM4-64–positive class E compartment in vps4Δ mutant cells (Figure 1C), indicating that, like all known proteins that function in the MVB pathway, its release from endosomes is Vps4-dependent. Together, these data indicate that Ist1 is an ESCRT-associated protein, as both its recruitment to and release from endosomes require key players in the MVB-sorting pathway.

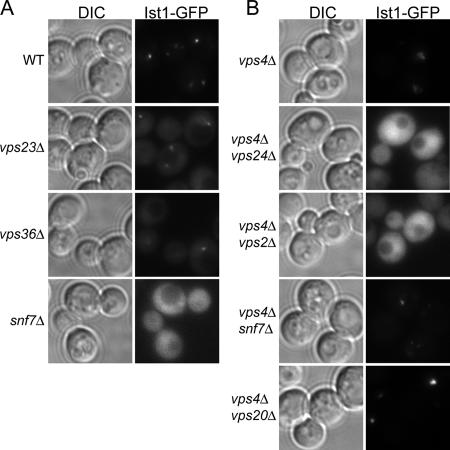

Ist1 Is Recruited to Endosomes by ESCRT-III

To identify the step in the MVB-sorting pathway at which Ist1 is recruited to endosomes, we visualized the localization of Ist1-GFP in deletion mutants of ESCRT-I, -II, and -III components. Although the cytoplasmic signal of Ist1-GFP was increased relative to wild-type in the ESCRT-I mutant vps23Δ and the ESCRT-II mutant vps36Δ, only mutants lacking core components of ESCRT-III such as snf7Δ caused a complete mislocalization of Ist1 to the cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Together with the results of Figure 1C, these data suggest that Ist1 (directly or indirectly) requires ESCRT-III for proper endosomal localization; Ist1-GFP is mislocalized in vps27Δ mutant cells and in mutants lacking components of ESCRT-I or ESCRT-II simply because of the sequential nature of the MVB-sorting pathway. Ist1 does not appear to be required for endosomal localization of ESCRT-III components; however, localization of ESCRT-III components was normal when tested by subcellular fractionation in ist1Δ mutant cells (Supplementary Figure 1 and data not shown).

Figure 2.

Endosomal recruitment of Ist1 depends on ESCRT-III. (A) Localization of Ist1-GFP in mutants lacking components of ESCRT-I (vps23Δ), -II (vps36Δ), and -III (snf7Δ). (B) The localization of plasmid-expressed Ist1-GFP was analyzed in double deletion mutants of vps4Δ and genes encoding ESCRT-III components.

In vps4Δ mutant cells, ESCRT components that are recruited to the endosomal membrane are trapped in the class E compartment, whereas ESCRT components that are not efficiently recruited remain cytoplasmic (Babst et al., 2002b; Katzmann et al., 2003). The four ESCRT-III subunits form two subcomplexes on the endosomal membrane: Snf7-Vps20 and Vps2-Vps24 (Babst et al., 2002a). To determine which of these two subcomplexes is absolutely required for the recruitment of Ist1 to endosomes, we tested the localization of Ist1-GFP in mutants in which ESCRT-III genes were deleted in the vps4Δ background. Ist1 localized to the class E endosomal compartment in snf7Δ vps4Δ and vps20Δ vps4Δ double mutant cells but remained cytoplasmic in vps24Δ vps4Δ and vps2Δ vps4Δ cells (Figure 2B). These data indicate that Ist1 is recruited to endosomes (directly or indirectly) by the Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex of ESCRT-III. This finding may seem inconsistent with the previously published model of ESCRT-III recruitment and assembly, in which the Vps20-Snf7 complex is required for endosomal recruitment of Vps2-Vps24 (Babst et al., 2002a). One model would be that Snf7 and/or Vps20 normally masks a secondary site for Ist1 binding, such that when Snf7 or Vps20 is not present in the context of the vps4Δ mutant, Ist1 still associates with endosomes via this secondary site.

Ist1, Did2, Vta1, and Vps60 Function Together to Positively Modulate Cargo Sorting

To address the potential protein sorting function for Ist1, we tested whether deletion of IST1 had an effect on the sorting of several biosynthetic and endocytic cargo proteins. Consistent with the fact that IST1 has not been identified in any of the cargo-sorting genetic screens, sorting of all six cargos tested (GFP-CPS, Sna3-GFP, Ste2-GFP, Fur4-GFP, Can1-GFP, and Mup1-GFP) to the vacuole in ist1Δ mutant cells appeared to be indistinguishable from that in wild-type cells (Supplementary Figure 2; refer to Figure 3 and data not shown).

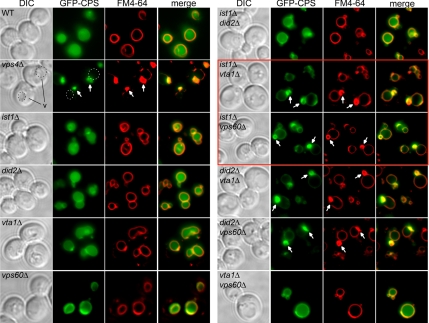

Figure 3.

Sorting of a GFP fusion of the vacuolar hydrolase CPS (GFP-CPS) and of the lipophilic dye FM4-64 was visualized in single and double deletion mutants of IST1 and three weak class E genes, DID2, VTA1, and VPS60, in order to identify synthetic genetic effects on cargo sorting. The limiting membrane of the vacuole is indicated in vps4Δ cells because it is difficult to see by GFP-CPS sorting or FM4-64 staining in this mutant. v, vacuole. Arrows indicate class E compartments. Panels that indicate that Ist1 is a positive modulator of MVB sorting are boxed in red.

The lack of a cargo-sorting phenotype in the ist1Δ mutant led us to hypothesize that Ist1 is a modulator of MVB sorting, not a core component of the ESCRT machinery. Overexpression of Ist1 also failed to cause a sorting phenotype (data not shown), suggesting that Ist1 is not a negative regulator of the MVB pathway. To test whether Ist1 is a positive regulator of this process, we looked for synthetic genetic interactions between IST1 and a group of four genes that we will refer to as “weak class E” VPS genes. Here, for the purpose of this study, we define a weak class E phenotype based on sorting of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion of the vacuolar hydrolase carboxypeptidase S (GFP-CPS) and the lipophilic dye FM4-64 in the SEY6210 strain background. In a weak class E mutant, 1) although GFP-CPS accumulates to some extent on the limiting membrane of the vacuole, at least some of this cargo is sorted into the lumen of the vacuole, and 2) there is a lack of any prominent class E compartment by FM4-64 staining. In studies of the MVB-sorting pathway, five yeast deletion mutants have been classified by our laboratory and others as having weak class E phenotypes: did2Δ, vta1Δ, vps60Δ, mvb12Δ, and doa4Δ (Amerik et al., 2000; Reggiori and Pelham, 2001; Shiflett et al., 2004; Azmi et al., 2006; Chu et al., 2006; Curtiss et al., 2007; Oestreich et al., 2007 and this study; refer to Figure 3, left panel). With the exception of Doa4, all of the proteins encoded by these weak class E genes are believed to be positive modulators of MVB sorting. Did2 is thought to modulate the dissociation of ESCRT-III from endosomes by the AAA-ATPase Vps4 (Nickerson et al., 2006), whereas Vta1 directly stimulates the ATPase activity of Vps4 (Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006; Lottridge et al., 2006). The function of Vps60 is not known, but it binds to Vta1 in vivo, although this interaction has not been shown to be direct in vitro with purified proteins (Kranz et al., 2001; Bowers et al., 2004; Shiflett et al., 2004; Azmi et al., 2006). Mvb12 is an ESCRT-I subunit that regulates the assembly of the ESCRT-I/ ESCRT-II supercomplex (Chu et al., 2006).

To look for synthetic genetic interactions between IST1 and the four weak class E genes, we analyzed the sorting of GFP-CPS in a panel of double mutants (data summarized in Table 1; refer to Figure 3 and data not shown). The ist1Δ vta1Δ and ist1Δ vps60Δ double mutants had severe, synthetic cargo-sorting defects, whereas ist1Δ did2Δ and ist1Δ mvb12Δ did not. The results of this synthetic genetic analysis suggest that Ist1 has a function that parallels that of Vta1 and Vps60. As Vta1 and (likely) Vps60 play positive roles in MVB sorting, these data also indicate that Ist1 is a positive component of this pathway (data in Figure 3 that implicate Ist1 as a positive factor are boxed).

Table 1.

Synthetic interactions between IST1 and weak class E genes

| Genotype | Synthetic GFP-CPS phenotype? |

|---|---|

| ist1Δ vta1Δ | Yes |

| ist1Δ vps60Δ | Yes |

| ist1Δ did2Δ | No |

| ist1Δ mvb12Δ | No |

Synthetic Genetic Interactions among IST1, DID2, VTA1, and VPS60

In separate studies, we had found that (like Ist1) Did2 and Vta1 specifically require the core ESCRT-III components Vps2 and Vps24 for endosomal recruitment (Table 2; our data are consistent with reports that Did2 requires the Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex for recruitment; Nickerson et al., 2006). We were unable to draw conclusions about the localization of fluorescent fusions of Vps60 in these mutants, as these fusions appeared to complement to different extents in various assays (not shown). In contrast, recruitment of the ESCRT-I subunit Mvb12 to endosomes did not require the presence of ESCRT-III components (Table 2). Together with the observation that IST1 and MVB12 did not display synthetic genetic interactions (refer to Table 1), these endosomal recruitment data indicate that Ist1, Did2, Vta1, and (likely) Vps60 represent a unique group of ESCRT-III-recruited proteins. Furthermore, the fact that, although Ist1 and Did2 have identical requirements for endosomal recruitment and both positively modulate MVB sorting, IST1 displayed synthetic genetic interactions with VTA1 and VPS60 but not DID2 suggests that Ist1 and Did2 may actually form a unit that functions separate from another unit composed of Vta1 and Vps60.

Table 2.

ESCRT-III requirements for localization of Ist1 and weak class E proteins

| Ist1-GFP | GFP-Did2 | GFP-Vta1 | Mvb12-GFP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Perivacuolar punctae and cytoplasm | Perivacuolar punctae | Perivacuolar punctae and cytoplasm | Perivacuolar punctae and cytoplasm |

| vps4Δ | E dot | E dot | E dot and cytoplasm | E dot |

| vps4Δ vps2Δ | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | E dot |

| vps4Δ vps24Δ | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | E dot |

| vps4Δ snf7Δ | E dot | E dot and cytoplasm | E dot and cytoplasm | E dot |

| vps4Δ vps20Δ | E dot | E dot and cytoplasm | E dot and cytoplasm | E dot |

To test the idea that there are two functional units composed of Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 that act at a late step in cargo sorting, we created a network of double mutants to expand our initial synthetic genetic analysis (Figure 3; see Table 3 for a summary of the results). The GFP-CPS sorting phenotypes of the ist1Δ, did2Δ, vta1Δ, and vps60Δ single mutants were all much weaker than typical class E mutants which are missing core MVB pathway components such as vps4Δ (Figure 3, left panel). These four weak mutants consistently displayed different levels of severity in terms of their GFP-CPS–sorting phenotypes, with ist1Δ having the weakest (no phenotype), vps60Δ having the strongest, and did2Δ and vta1Δ having phenotypes intermediate in severity to those of ist1Δ and vps60Δ. Interestingly, a number of synthetic interactions among these four genes became evident in the double mutants (Figure 3, right panel). As in our initial analysis, ist1Δ had a synthetic interaction with both vta1Δ and vps60Δ but not did2Δ, indicating that Ist1 has a function that is separate from that of Vta1 and Vps60. Similarly, did2Δ had synthetic interactions with both vta1Δ and vps60Δ, indicating that, like Ist1, Did2 functions separate from Vta1 and Vps60. Finally, vta1Δ and vps60Δ, like ist1Δ and did2Δ, did not display a synthetic interaction in cargo sorting. From these synthetic genetic analyses, we conclude that there are two candidate complexes with similar degrees of functional importance required for proper cargo sorting at this late step in the MVB pathway: one composed of Ist1 and Did2 and one composed of Vta1 and Vps60. Simultaneous deletion of one member from each candidate complex causes a dramatic class E phenotype because the function of both complexes is abrogated, whereas deletion of both members of the same complex only causes a weak phenotype because the function of the remaining candidate complex is still intact.

Table 3.

Synthetic genetic interactions among IST1, DID2, VTA1, and VPS60 in cargo sorting

| Genotype | GFP-CPS phenotype |

|---|---|

| ist1Δ did2Δ | Weak |

| ist1Δ vta1Δ | Strong |

| ist1Δ vps60Δ | Strong |

| did2Δ vta1Δ | Strong |

| did2Δ vps60Δ | Strong |

| vta1Δ vps60Δ | Weak |

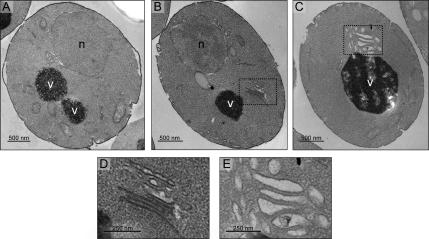

Electron Microscopy Analysis of Double Deletion Mutants

The ist1Δ, did2Δ, vta1Δ, and vps60Δ deletion mutants all caused relatively weak phenotypes as determined by sorting of GFP-CPS and FM4-64 labeling, whereas simultaneous deletion of one component from each of the two candidate complexes (Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60) caused what appeared to be a typical strong class E sorting phenotype characterized by the accumulation of a large, aberrant endosomal structure adjacent to the vacuole (Figure 3). To confirm the presence or absence of class E compartments as determined by fluorescence microscopy, we performed electron microscopy (EM) on several single and double mutants. In all EM samples, MVBs were not easy to identify or to classify as normal or abnormal. Therefore, we will limit our analysis of the EM results to the presence or absence of a class E compartment. Consistent with the fluorescence microscopy data, no classical multilamellar class E compartments were visible in photomicrographs of the ist1Δ, did2Δ, vta1Δ, and vps60Δ single mutants (data not shown). In support of our observation that the ist1Δ did2Δ double mutant did not have a strong class E phenotype by fluorescence microscopy, no aberrant structures were observed in these cells by EM (Figure 4A). In both ist1Δ vta1Δ (Figure 4, B and D) and did2Δ vta1Δ (Figure 4, C and E) mutant cells, however, enlarged multilamellar endosomal structures similar to those seen in previously characterized strong class E mutants were visible (Reider et al., 1996). These results not only validate our fluorescence microscopy data but also indicate that simultaneous deletion of one component from each of the two candidate complexes composed of Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 causes a true class E sorting phenotype. Together, our data thus far suggest that these two units function in parallel to positively modulate a requisite late event of the MVB-sorting pathway.

Figure 4.

Thin-section EM analysis of double mutant strains. Photomicrographs of (A) ist1Δ did2Δ, (B) ist1Δ vta1Δ, and (C) did2Δ vta1Δ mutant cells. (D and E) Enlargements of the class E compartments that are visible in ist1Δ vta1Δ and did2Δ vta1Δ cells, respectively. n, nucleus; v, vacuole.

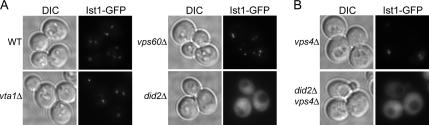

Did2 Recruits Ist1 to Endosomes

Given that Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 compose two separate candidate complexes, we predicted that each protein would interact with its partner, an idea supported by the fact that Vta1 and Vps60 have previously been shown to interact in vivo (Bowers et al., 2004; Shiflett et al., 2004; Azmi et al., 2006). To test this, we analyzed the localization of functional GFP fusions of Ist1, Did2, and Vta1 in deletion mutants of the other three genes. As mentioned above, we could not test the localization of Vps60 in deletion mutants because none of the fluorescent fusions tested were completely functional in all assays (not shown). Although Ist1-GFP was properly localized to endosomes in vta1Δ and vps60Δ cells, it was entirely cytoplasmic in did2Δ cells (Figure 5A; results summarized in Table 4). The same pattern was seen for the localization of Ist1-GFP in the double mutants vta1Δ vps4Δ, vps60Δ vps4Δ, and did2Δ vps4Δ, indicating that Did2 is required for the endosomal recruitment of Ist1 (Figure 5B and not shown). The reverse was not true, however; a GFP-Did2 fusion was properly localized in the ist1Δ, vta1Δ, and vps60Δ deletion mutants (Table 4). These findings point to a model in which Ist1 is recruited to endosomes (directly or indirectly) by Did2 but not vice versa.

Figure 5.

Ist1 requires Did2 for endosomal recruitment. (A) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of wild-type and weak class E mutant strains expressing a genomic Ist1-GFP fusion. (B) Localization of plasmid-expressed Ist1-GFP in vps4Δ and did2Δ vps4Δ cells.

Table 4.

Requirements for localization of Ist1, Did2, and Vta1

| Ist1-GFP | GFP-Did2 | Vta1-GFP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Perivacuolar punctae and cytoplasm | Perivacuolar punctae | Perivacuolar punctae and cytoplasm |

| ist1Δ | — | WT | WT |

| did2Δ | Cytoplasm | — | WT |

| vps60Δ | WT | WT | WT |

| vta1Δ | WT | WT | — |

We next tested whether Vta1 requires Ist1, Did2, or Vps60 for endosomal localization. Like Did2, Vta1 did not appear to require the presence of any of the other three proteins for its endosomal localization (Table 4). Although Vta1 clearly does not require its candidate complex partner Vps60 for endosomal recruitment, we cannot rule out the possibility that Vta1 is required for Vps60 recruitment based on these experiments. Together, these endosomal recruitment data suggest that Ist1 specifically requires the presence of Did2 for proper endosomal localization, indicating that Ist1-Did2 could be not only a functional unit but also a specific protein complex at the endosome.

Ist1-Did2, Vta1-Vps60, and Ist1-Vps4 Interact In Vitro

We analyzed whether Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 physically interact by performing pulldown experiments with purified bacterially expressed proteins. Using this approach, we found that the interaction between Ist1 and Did2 is indeed direct and specific: Ist1-His6-conjugated beads pulled down GST-Did2 but not GST-Vps60 or GST alone (Figure 6A). Additionally, we found that GST-Vps60 pulled down what appeared to be stoichiometric amounts of Vta1-His6 but GST alone, GST-Ist1, and GST-Did2 did not pull down Vta1-His6, which indicates that the interaction between Vta1 and Vps60 is specific and direct as well (Figure 6B). The fact that Did2 and Vta1 do not bind in our assays contrasts with one report that showed that Did2 and Vta1 interact in vitro (Lottridge et al., 2006). Although we cannot completely exclude the possibility that Vta1 and Did2 can interact, it is very likely that Vps60 (which we have shown to bind stoichiometrically to Vta1), not Did2, is the major binding partner of Vta1: the Vta1-Did2 interaction reported by Lottridge and colleagues appeared to be rather weak and was detected by Western blot. Altogether, our pulldown experiments using purified proteins indicate that the two functional units Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 are specific physical complexes as well.

Figure 6.

Protein–protein interactions of Ist1, Did2, Vta1, and Vps60. All proteins were visualized by Coomassie staining. Panels showing positive interactions are boxed in red. B, bound; UN, unbound. (A) Direct interaction between bacterially expressed Ist1 and Did2 was tested by pulling down GST alone, GST-Vps60, or GST-Did2 with Ist1-His6–conjugated Ni2+-NTA beads. (B) Purified Vta1-His6 protein was pulled down with GST-, GST-Ist1–, GST-Did2–, or GST-Vps60–conjugated glutathione Sepharose beads. Asterisks denote background bands. (C) Binding of Ist1 to Vps4 was tested by pulling down GST or GST-Ist1 with Vps4-His6–conjugated Ni2+-NTA beads.

Ist1 was recently identified as a potential Vps4-interacting protein in a tandem affinity purification/mass spectroscopy study designed to map protein–protein interactions in yeast (Krogan et al., 2006). We therefore tested whether bacterially expressed, purified Vps4 binds Ist1 in vitro. Indeed, Vps4 does interact directly with Ist1: Vps4-His6 pulled down GST-Ist1 but not GST alone (Figure 6C).

IST1 Interacts Genetically with Mutations That Compromise Vps2-Vps4 Interaction

In collaboration with others, we recently determined a 2-Å resolution crystal structure of the C terminus of the ESCRT-III subunit Vps2 in complex with the Vps4 MIT domain (Obita et al., 2007). In that study, we identified a conserved motif in the C terminus of both Vps2 and Did2 that is responsible for MIT domain binding, which we called the MIM (Obita et al., 2007). Amino acid substitutions in residues within the MIMs of Vps2 and Did2 that make key contacts with the Vps4 MIT domain result in cargo-sorting defects, which indicates the functional importance of Vps2-Vps4 and Did2-Vps4 interactions (Obita et al., 2007). As the MIT domain of Vps4 has been shown to be involved in both Vps4 recruitment to endosomes (Babst et al., 1998) and in Vps4-ESCRT-III interactions that probably function to release ESCRT-III from endosomes (reviewed in Shim et al., 2007; Williams and Urbe, 2007), these results suggest that the MIMs of Vps2 and Did2 participate in one or both of these important processes, thereby modulating the activity of the Vps4 complex.

Our data showing that Ist1 forms a functional and physical complex with Did2 (which has an MIM; Obita et al., 2007; Figures 3 and 6) and binds Vps4 directly (Figure 6) strongly indicate that Ist1 is a positive modulator of late steps in the MVB-sorting pathway. To further characterize the involvement of Ist1 late in the pathway, we looked for synthetic effects in cargo sorting between ist1Δ (Ist1 does not have an MIM, so the deletion mutant was used) and two mutants with substitutions in residues in the Vps2 MIM: VPS2-L225D and VPS2-L228D. Although Vps2-L225 and -L228 are present in the MIM and clearly required for normal Vps2-Vps4 interaction, based on the crystal structure they are not as essential as Vps2-R224, the anchor for Vps2 MIM-Vps4 MIT domain interaction (Obita et al., 2007). As expected in light of the crystal structure (Obita et al., 2007), the VPS2-L225D and VPS2-L228D single Vps2 substitution mutants did not exhibit a GFP-CPS–sorting defect (Figure 7). We tested for synthetic genetic interactions between these substitution mutants and ist1Δ by analyzing GFP-CPS sorting in VPS2-L225D ist1Δ and VPS2-L228D ist1Δ double mutants. Intriguingly, combining the “silent” (no phenotype) VPS2-L225D substitution with the equally “silent” ist1Δ mutant resulted in a very strong synthetic class E phenotype (Figure 7). The VPS2-L228D ist1Δ double mutant also displayed a synthetic GFP-CPS–sorting phenotype (Figure 7), although the phenotype of this double mutant was weaker than that of the VPS2-L225D ist1Δ double mutant: only accumulation of GFP-CPS on the rim of the vacuole was observed. One possible explanation for the difference in severity between the phenotypes of these double mutants is that Vps2-L225 is immediately adjacent to the anchor residue for Vps2-Vps4 interaction (Vps2-R224; Obita et al., 2007), so it may play a more important structural role in stabilizing Vps2-Vps4 interaction than Vps2-L228. These data suggest that Ist1, like Vps2, Did2, Vta1, and (likely) Vps60, is involved in requisite events late in MVB sorting.

Figure 7.

Synthetic sorting defects between ist1Δ and mutants with substitutions in the MIT-interacting motif (MIM) of Vps2. GFP-CPS sorting was visualized in mutants with substitutions in noncritical residues in the MIM of Vps2 alone and in combination with the ist1Δ deletion mutant. Cells were stained with FM4-64.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have provided evidence that Ist1 is a new positive component of the MVB-sorting pathway. Using three different approaches, we have shown that Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 form two complexes that are recruited and function at key steps late in the MVB-sorting pathway. First, our synthetic genetic analysis demonstrates that Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 form separate functional units: simultaneous deletion of one member of each functional complex causes a severe synthetic cargo-sorting phenotype (Figure 3 and Table 3) and the formation of a class E compartment visible by EM (Figure 4). Second, using fluorescence microscopy analysis of the localization of GFP fusions of Ist1, Did2, and Vta1 in mutants lacking each of the other three members of this group of proteins, we demonstrate that Did2 specifically recruits it functional partner Ist1 to endosomes (Figure 5 and Table 4). Third, the results of pulldown assays using purified bacterially expressed proteins indicate that Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 form two distinct protein complexes (Figure 6).

Our preliminary gel filtration data indicate that Did2 and Vps60 are predominantly monomeric in the cytosolic fraction (data not shown); therefore, the Ist1-Did2 and Vta-Vps60 complexes do not appear to form in the cytosol. Rather, like the ESCRT-III subcomplexes Snf7-Vps20 and Vps2-Vps24, the Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 complexes probably assemble on the endosomal membrane. Although the interaction between Vta1 and Vps60 has been detected in cells (Bowers et al., 2004; Shiflett et al., 2004; Azmi et al., 2006), we have not been able to detect an interaction between Ist1 and Did2 in cell lysates. It is possible that the Ist1-Did2 interaction is difficult to detect in vivo because this protein complex is very unstable and transient in cells, owing to the fact that Ist1 and Did2 are constantly cycling on and off of endosomes. However, our fluorescence microscopy data indicating that Did2 recruits Ist1 to endosomes (Figure 5), coupled with the fact that Ist1 directly binds Did2 in vitro (Figure 6), strongly indicate that the Ist1-Did2 complex does form within yeast cells.

The results of this and other recent studies have provided considerable insight into the order of recruitment and protein–protein interactions of factors involved in Vps4 modulation late in MVB sorting (summarized in Figure 8). Vps27-Hse1 is recruited to the endosomal membrane, after which the ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II, and ESCRT-III complexes assemble sequentially. The Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex of ESCRT-III recruits the Ist1-Did2 complex (Figure 2 and Table 2 of this study and Nickerson et al., 2006), probably via the direct interaction between Vps24 and Did2 (Nickerson et al., 2006). The recruitment of the Ist1-Did2 complex by ESCRT-III precedes the recruitment of Vps4, as GFP fusions of both Ist1 and Did2 localize to the class E compartment in vps4Δ cells (Figure 1 and Table 2 of this study and Nickerson et al., 2006).

Figure 8.

Order of assembly and protein–protein interactions of Ist1, Did2, Vta1, and Vps60 (see Discussion). Solid lines indicate interactions that we and others have shown (Babst et al., 2002a,b; Yeo et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006; Lottridge et al., 2006; Nickerson et al., 2006; Vajjhala et al., 2006, 2007; Obita et al., 2007); dashed lines indicate interactions that require further investigation.

After recruitment of Ist1-Did2, the Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex of ESCRT-III recruits Vps4, likely via interaction between Vps2 and the MIT domain of Vps4 (whether Vps24 binds Vps4 directly is unclear; Babst et al., 2002a; Obita et al., 2007). Both members of the Ist1-Did2 functional complex bind to Vps4 (Lottridge et al., 2006; Nickerson et al., 2006; Obita et al., 2007; and Figure 6). Vps4 may directly recruit the Vta1-Vps60 complex, as GFP fusions of Vta1 are partially mislocalized to the cytoplasm in vps4Δ cells (Table 2 and Azmi et al., 2006). Vta1 binds Vps4 directly (whether Vps60 binds Vps4 remains to be tested) and coassembles with it to form the Vps4 complex (Yeo et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006; Lottridge et al., 2006). Vps60 may coassemble with Vps4 and Vta1 or could bind to domains of Vta1 that are exposed on the outside of the Vps4 complex.

The Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 complexes clearly function late in MVB sorting, and given that at least three of these four components bind to Vps4 (Vps60-Vps4 binding remains to be tested), it is very probable that these two complexes modulate Vps4 in conjunction with the Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex of ESCRT-III. In fact, both Vta1 and Did2 (which according to this study are in separate functional complexes) have been shown to be required for optimal release of ESCRT-III (Azmi et al., 2006; Nickerson et al., 2006). However, there are several pieces of evidence that Did2 and Vta1 (which we have shown to be members of two separate functional and physical complexes) interact with Vps4 in very different ways. First, Did2 and Vta1 bind to different domains of Vps4. Did2 and its human ortholog CHMP1B bind the MIT domain of Vps4, which is required for recruitment of Vps4 to endosomes and for its interaction with ESCRT-III components, and Did2/CHMP1B binding to Vps4 is ATP-independent (Babst et al., 1998; Scott et al., 2005b; Lottridge et al., 2006; Nickerson et al., 2006; Obita et al., 2007). Vta1 and its ortholog LIP5, on the other hand, bind to the β domain of Vps4, which modulates its ATPase activity, and these interactions are ATP-dependent (Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006; Vajjhala et al., 2006). Second, Did2 and Vta1 appear to have different functions with regard to Vps4: Vta1 directly activates the assembly and ATPase activity of the multimeric Vps4 complex, whereas Did2 does not (Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006; Lottridge et al., 2006). These differences, coupled with the fact that Did2 is recruited before Vps4, whereas Vta1 is recruited by Vps4, indicate that the Ist1-Did2 complex and the Vta1-Vps60 complex likely play very different roles in Vps4 modulation.

Given the clear differences in how Did2 and Vta1 bind Vps4, together with the previously proposed roles for Did2 and Vta1, the simplest model to explain the observation that simultaneous deletion of one member of each of the Ist1-Did2 and Vta1-Vps60 complexes causes a synthetic class E vps phenotype is that Vps4 is regulated at several different steps in its cycle. There are three potential steps at which Vps4 requires regulation: 1) its recruitment to endosomes, 2) activation of its ATPase activity, and 3) its interaction with ESCRT-III components to release them from the endosomal membrane. The endosomal recruitment of Vps4 is carried out (at least in part) by the Vps2-Vps24 subcomplex of ESCRT-III (Babst et al., 2002a). Activation of Vps4 ATPase activity is performed by the Vta1-Vps60 complex, as Vta1 coassembles with and directly activates Vps4 (Scott et al., 2005a; Azmi et al., 2006; Lottridge et al., 2006; another group has proposed that Vps60 may be required for full activation of Vps4 by Vta1, as N-terminal truncations of Vta1 that cannot bind to Vps60 in vivo but are still capable of activating Vps4 in vitro do not complement the vta1Δ phenotype; Azmi et al., 2006). Although further experimentation is required to determine the exact step modulated by the Ist1-Did2 complex, we favor a model in which this complex regulates an aspect of the interaction between Vps4 and ESCRT-III components to favor Vps4-mediated ESCRT-III release, either by directly promoting Vps4-ESCRT-III interaction or by stabilizing ESCRT-III components in a conformation that is favorable for their interaction with Vps4. This model is in keeping with the proposed role of Did2 in modulating ESCRT-III release by Vps4 (Nickerson et al., 2006) and is supported by the fact that Did2 binds both the ESCRT-III component Vps24 and the MIT domain of Vps4, which is responsible for Vps4-ESCRT-III interaction (Nickerson et al., 2006; Obita et al., 2007). Although additional experimentation is necessary to determine the specific function of Ist1 in the Ist1-Did2 complex, one simple model is that it facilitates Did2-Vps4 interaction, as either a chaperone or a scaffold. Coordinate regulation of Vps4 by Vps2-Vps24, Vta1-Vps60, and Ist1-Did2 likely functions to ensure that the critical ESCRT-III release step in MVB sorting occurs in a timely, well-ordered manner. Further studies will be needed to resolve the precise details of this well-ordered and essential step in ESCRT protein function and recycling.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EM was performed with the assistance of Ingrid Niesman and Dr. Marilyn Farquhar in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UCSD. We are extremely grateful to Roger Williams and Markus Babst for sharing unpublished data and for insightful comments on the manuscript. We thank Christopher Stefan, David Teis, and Ji Sun for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. S.R. was supported by fellowships from the National Institutes of Health and the American Cancer Society, S.M. by a fellowship from the French Medical Research Foundation (FRM), and S.S. by a fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). This research was funded by the HHMI (S.D.E.).

Abbreviations used:

- CPS

carboxypeptidase S

- ESCRT

endosomal sorting complex required for transport

- MIM

MIT-interacting motif

- MIT

microtubule interacting and trafficking

- MVB

multivesicular body

- Vps

vacuolar protein sorting.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0694) on November 21, 2007.

REFERENCES

- Amerik A. Y., Nowak J., Swaminathan S., Hochstrasser M. The Doa4 deubiquitinating enzyme is functionally linked to the vacuolar protein-sorting and endocytic pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:3365–3380. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmi I., Davies B., Dimaano C., Payne J., Eckert D., Babst M., Katzmann D. J. Recycling of ESCRTs by the AAA-ATPase Vps4 is regulated by a conserved VSL region in Vta1. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:705–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M. A protein's final ESCRT. Traffic. 2005;6:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M., Katzmann D. J., Estepa-Sabal E. J., Meerloo T., Emr S. D. Escrt-III: an endosome-associated heterooligomeric protein complex required for mvb sorting. Dev. Cell. 2002a;3:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M., Katzmann D. J., Snyder W. B., Wendland B., Emr S. D. Endosome-associated complex, ESCRT-II, recruits transport machinery for protein sorting at the multivesicular body. Dev. Cell. 2002b;3:283–289. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M., Wendland B., Estepa E. J., Emr S. D. The Vps4p AAA ATPase regulates membrane association of a Vps protein complex required for normal endosome function. EMBO J. 1998;17:2982–2993. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankaitis V. A., Johnson L. M., Emr S. D. Isolation of yeast mutants defective in protein targeting to the vacuole. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:9075–9079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau P. S., Urbanowski J. L., Winistorfer S. C., Piper R. C. The Vps27p Hse1p complex binds ubiquitin and mediates endosomal protein sorting. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:534–539. doi: 10.1038/ncb815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers K., Lottridge J., Helliwell S. B., Goldthwaite L. M., Luzio J. P., Stevens T. H. Protein-protein interactions of ESCRT complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Traffic. 2004;5:194–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T., Sun J., Saksena S., Emr S. D. New component of ESCRT-I regulates endosomal sorting complex assembly. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:815–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss M, Jones C, Babst M. Efficient cargo sorting by ESCRT-I and the subsequent release of ESCRT-I from multivesicular bodies requires the subunit Mvb12. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;2:636–645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirov D. G., Freed E. O. Retrovirus budding. Virus Res. 2004;106:87–102. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efe J. A., Plattner F., Hulo N., Kressler D., Emr S. D., Deloche O. Yeast Mon2p is a highly conserved protein that functions in the cytoplasm-to-vacuole transport pathway and is required for Golgi homeostasis. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4751–4764. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L., Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E. L., et al. Saccharomyces Genome Database. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Huh W. K., Falvo J. V., Gerke L. C., Carroll A. S., Howson R. W., Weissman J. S., O'Shea E. K. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J. H., Emr S. D. The ESCRT complexes: structure and mechanism of a membrane-trafficking network. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:277–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann D. J., Odorizzi G., Emr S. D. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:893–905. doi: 10.1038/nrm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann D. J., Stefan C. J., Babst M., Emr S. D. Vps27 recruits ESCRT machinery to endosomes during MVB sorting. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:413–423. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz A., Kinner A., Kolling R. A family of small coiled-coil-forming proteins functioning at the late endosome in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:711–723. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan N. J., et al. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2006;440:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature04670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Copley R. R., Pils B., Pinkert S., Schultz J., Bork P. SMART5, domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottridge J. M., Flannery A. R., Vincelli J. L., Stevens T. H. Vta1p and Vps46p regulate the membrane association and ATPase activity of Vps4p at the yeast multivesicular body. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:6202–6207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601712103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita E., Sundquist W. I. Retrovirus budding. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:395–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.102350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson D. P., West M., Odorizzi G. Did2 coordinates Vps4-mediated dissociation of ESCRT-III from endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:715–720. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obita T., Saksena S., Ghazi-Tabatabai S., Gill D. J., Perisic O., Emr S. D., Williams R. L. Structural basis for selective recognition of ESCRT-III by the AAA-ATPase Vps4. Nature. 2007;449:735–739. doi: 10.1038/nature06171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi G., Katzmann D. J., Babst M., Audhya A., Emr S. D. Bro1 is an endosome-associated protein that functions in the MVB pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:1893–1903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oestreich A. J., Davies B. A., Payne J. A., Katzmann D. J. Mvb12 is a novel member of ESCRT-I involved in cargo selection by the multivesicular body pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;2:646–657. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C., Rusten T. E., Stenmark H. Protein sorting into multivesicular endosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:446–455. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond C. K., Howald-Stevenson I., Vater C. A., Stevens T. H. Morphological classification of the yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants: evidence for a prevacuolar compartment in class E vps mutants. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1992;3:1389–1402. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.12.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reider S. E., Banta L. M., Köhrer K., McCaffery J. M., Emr S. D. Multilamellar endosome-like compartment accumulates in the yeast vps28 vacuolar protein sorting mutant. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:985–999. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F., Pelham H. R. Sorting of proteins into multivesicular bodies: ubiquitin-dependent and -independent targeting. EMBO J. 2001;20:5176–5186. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J. H., Stevens T. H. Protein sorting in yeast: mutants defective in vacuole biogenesis mislocalize vacuolar proteins into the late secretory pathway. Cell. 1986;47:1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90819-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksena S., Ji S., Chu T., Emr S. D. ESCRTing proteins in the endocytic pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J., Milpetz F., Bork P., Ponting C. P. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A., et al. Structural and mechanistic studies of VPS4 proteins. EMBO J. 2005a;24:3658–3669. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A., Gaspar J., Stuchell-Brereton M. D., Alam S. L., Skalicky J. J., Sundquist W. I. Structure and ESCRT-III protein interactions of the MIT domain of human VPS4A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005b;102:13813–13818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502165102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiflett S. L., Ward D. M., Huynh D., Vaughn M. B., Simmons J. C., Kaplan J. Characterization of Vta1p, a class E Vps protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10982–10990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S., Kimpler L. A., Hanson P. I. Structure/function analysis of four core ESCRT-III proteins reveals common regulatory role for extreme C-terminal domain. Traffic. 2007;8:1068–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagsvold T., Pattni K., Malerod L., Stenmark H. Endosomal and non-endosomal functions of ESCRT proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajjhala P. R., Catchpoole E., Nguyen C. H., Kistler C., Munn A. L. Vps4 regulates a subset of protein interactions at the multivesicular endosome. FEBS J. 2007;274:1894–1907. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajjhala P. R., Wong J. S., To H. Y., Munn A. L. The beta domain is required for Vps4p oligomerization into a functionally active ATPase. FEBS J. 2006;273:2357–2373. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida T. A., Emr S. D. A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:779–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. L., Urbe S. The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:355–368. doi: 10.1038/nrm2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo S. C., et al. Vps20p and Vta1p interact with Vps4p and function in multivesicular body sorting and endosomal transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:3957–3970. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.