Abstract

Zinc may be released from some presynaptic glutamatergic neurons, including hippocampal mossy fibres and retinal photoreceptors. We whole-cell-clamped glial (Müller) cells isolated from the salamander retina to investigate the effect of zinc on glutamate transporters in these cells. Glutamate-evoked currents in these cells are generated largely by carriers homologous to the mammalian GLAST/EAAT1 transporter.

Zinc inhibited both glutamate uptake into the cells, and glutamate release by reversal of the uptake process. The IC50 for inhibition of uptake (< 1 μM) was similar to or below the values for zinc modulating NMDA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA) and GABA receptors, and 100-fold less than the calculated value for the rise in extracellular zinc concentration evoked by depolarization with potassium in area CA3 of the hippocampus.

Although zinc altered the apparent affinity of the transporter for glutamate and Na+, it did not act simply by binding competitively to the glutamate-, Na+-, K+- or H+-binding sites on the transporter. Zinc inhibited both forward and reversed glutamate transport from the outside of the cell membrane, but not from the inside. The inhibitory action of zinc on uptake was voltage independent, indicating a zinc-binding site outside the membrane field.

As well as inhibiting glutamate transport, zinc potentiated activation of the anion conductance in the Müller cell glutamate transporter. However, zinc reduced the current mediated by the anion conductance in the cone synaptic terminal glutamate transporter (homologous to the mammalian EAAT5), indicating that zinc has different actions on different glutamate transporter subtypes.

By acting on glutamate transporters, zinc may have a neuromodulatory role during synaptic transmission and a neuroprotective role during transient ischaemia.

Zinc is present in glutamatergic synaptic terminals in several brain areas (Frederickson, 1989; Smart, Xie & Krishek, 1994), including the mossy fibre terminals of the hippocampus, where it is stored in vesicles (Crawford & Connor, 1972; Stengaard-Pedersen, Fredens & Larsson, 1983; Perez-Clausell & Danscher, 1985), and in photoreceptor cells of the retina (Wu, Qiao, Noebels & Yang, 1993). It is released from hippocampal mossy fibres by electrical stimulation in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Howell, Welch & Frederickson, 1984), and may reach a peak extracellular concentration of 300 μM during excitation by an elevated potassium concentration (Assaf & Chung, 1984).

Zinc can modulate synaptic transmission, both in normal and pathological conditions, by various mechanisms. It may reduce transmitter release by inhibiting presynaptic calcium channels (Busselberg, Platt, Michael, Carpenter & Haas, 1994) with an IC50 of 69 μm. It inhibits postsynaptic NMDA and GABA receptor currents, with an IC50 of 0.1–100 μm and 0.6–320 μm, respectively, and potentiates AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate) receptor currents, with an EC50 of 13–39 μm (reviewed by Smart et al. 1994). High doses of zinc (30–50 μm) block glutamate uptake (Gabrielsson, Robson, Norris & Chung, 1986), but it is uncertain whether this is a direct action or an indirect effect of inhibiting the Na+-K+ pump (Hexum, 1974) which sets up the ion and voltage gradients needed to drive the uptake process; effects of Na+-K+ pump inhibition would not be significant on the time scale of zinc release occurring during synaptic transmission. Reduction of GABAergic inhibition by zinc has been suggested as a cause of epilepsy (Buhl, Otis & Mody, 1996), and in ischaemia, zinc release from presynaptic neurons and entry into postsynaptic cells has been suggested to trigger the death of the postsynaptic cells (Koh, Suh, Gwag, He, Hsu & Choi, 1996).

We investigated the effects of zinc on glutamate uptake into retinal Müller cells. These glial cells take up glutamate released from photoreceptors and thus will be exposed to any zinc that the photoreceptors release (Wu et al. 1993). Zinc was found to inhibit glutamate transport whilst potentiating the anion conductance associated with the glutamate transporter.

METHODS

Cells and electrodes

Experiments were carried out at 25°C. Müller cells and cone photoreceptors were isolated by papain dissociation of retinae from tiger salamanders (Attwell, Werblin & Wilson, 1982; Barbour, Brew & Attwell, 1991) killed by decapitation followed by destruction of the brain. Retinal slices were prepared as described by Werblin (1978). Whole-cell clamping was used to monitor the current associated with glutamate transport or produced by the anion conductance which is activated during glutamate transport (Billups, Rossi & Attwell, 1996; Eliasof & Jahr, 1996). When studying the glutamate transporter in cones, we excluded cones that showed any current response to kainate (Sarantis, Everett & Attwell, 1988; Picaud, Larsson, Grant, Lecar & Werblin, 1995) since this response (unlike the transporter-mediated response) is blocked by the non-NMDA receptor blocker 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; D. Attwell, unpublished observations) and thus is not produced by the glutamate transporter. Electrodes had a series resistance in whole-cell mode of around 3 MΩ, leading to series resistance voltage errors of less than 2 mV. When changing the external anion present, a 4 m NaCl agar bridge was used as the bath electrode. Electrode junction potentials were compensated.

Solutions for studying forward uptake

Forward uptake was usually assessed as the inward current produced by external glutamate at a holding potential of −60 mV. The normal external solution contained (mm): NaCl, 75; choline chloride, 30; CaCl2, 3; MgCl2, 0.5; glucose, 15; Hepes, 5; BaCl2 (to block inward rectifier K+ channels), 6; pH set to 7.3 with N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG). Sometimes a 105 mm Na+ solution was used that was identical except for the substitution of NaCl for choline chloride: similar results were obtained with both solutions. This latter solution was used for sodium dependence experiments, with sodium replaced by choline as necessary. Pipette (internal) solution normally contained (mm): KCl, 95; NaCl, 5; NMDG2EGTA, 5; CaCl2, 1; MgCl2, 7; Hepes, 5; Na2ATP, 5; pH set to 7.0 with NMDG, but for experiments on the effect of 100 μm free internal zinc (which binds to EGTA and ATP) the NMDG2EGTA, CaCl2 and Na2ATP were omitted and KCl was increased to 104 mm. In some experiments, to eliminate current generated by Cl− movement through anion conductance in the transporter, we replaced all the Cl− in the above solutions with the impermeant anion D-gluconate (Wadiche, Amara & Kavanaugh, 1995). Glutamate analogues and blockers were obtained from Tocris Cookson; other chemicals were from Sigma.

Solutions for studying the anion conductance

When Cl− is the main anion present, the membrane current generated by Müller cell glutamate transporters is dominated by the inward current produced by the transport of glutamate and associated ions, because Cl− is poorly permeant through the anion conductance in the transporter (Billups et al. 1996; Eliasof & Jahr, 1996). To study the effect of zinc on the anion conductance in the carrier, we therefore replaced 50 mm of the external Cl− in the above solution with the more permeant anion NO3−. This leads to the transporter generating an outward current at positive potentials, dominated by the entry of NO3− through the anion conductance (Billups et al. 1996; Eliasof & Jahr, 1996). We also studied the anion conductance using the method of Billups et al. (1996), who showed that the anion conductance could be activated without net glutamate transport, using internal and external solutions lacking K+, and with Na+ and glutamate present inside the cell: for these experiments, the external solution was the NO3−-containing solution described above, and the internal solution was as described below for reversed uptake.

Solutions for studying reversed uptake

The pipette (internal) solution contained (mm): sodium glutamate, 10; NaCl, 5; choline chloride, 85; NMDG2EGTA, 5; CaCl2, 1; MgCl2, 7; Hepes, 5; Na2ATP, 5; pH set to 7.0 with NMDG (except for experiments on the effect of 100 μm free internal zinc, when the zinc-free internal solution contained (mm): sodium glutamate, 5; NaCl, 10; choline chloride, 107; Hepes, 5; MgCl2, 2; pH, 7.0; and the zinc-containing internal solution was the same but with 5.96 mm sodium glutamate and 0.92 mm ZnCl2). The external solution was like the ‘normal’ solution described above, but with 0.1 mm ouabain added to block the Na+-K+ pump. Reversed uptake was activated by replacing the choline chloride in this solution with KCl (Szatkowski, Barbour & Attwell, 1990).

Calculation of free zinc and glutamate concentrations

Glutamate chelates zinc according to the following reactions:

|

The total concentrations of zinc [Z] and glutamate [G] present are:

and

Defining the stability constants K1 and K2 as:

and

and the cumulative constant as:

we get:

and

These equations were used to calculate the total amounts of glutamate and zinc to be added to the solutions to produce any desired free values of these agents. Values of K1 and β are tabulated for very alkaline pH values and have to be corrected for the pH actually used (Dawson, Elliott, Elliott & Jones, 1986). (Barbour et al. 1991, omitted this pH correction, resulting in the binding of glutamate to Ba2+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ being overestimated.) At pH 7.3 and 25–30°C the corrected values are K1= 103.13 M−1 and β= 104.76 m−2. The effect of this binding depends on the free glutamate and zinc concentrations used. For example for 3 or 200 μm free glutamate at pH 7.3, the free zinc concentration is 0.4 or 22%, respectively, less than the total zinc concentration. For 80 μm free zinc and 3 μm or 200 μm free glutamate, the free glutamate concentration is 10% less than the total glutamate concentration. In this paper we always quote free concentrations of zinc and glutamate calculated as above. For the data in Fig. 7 an extra term had to be added to the equation above for the total zinc concentration, to correct for the binding of zinc to gluconate (equilibrium constant, 101.7 M−1; Smith & Martell, 1976). No correction was made for the binding of zinc to Cl− or NO3−, the published equilibrium constants for which vary considerably (Smith & Martell, 1976) and are similar for Cl− and NO3−: somewhere between 4 and 27% of our ‘free zinc’ is actually bound to Cl− in normal solution. To prevent zinc accumulating in, and later being released from, the tubes used to superfuse solution over the cells, we regularly washed them through with a solution containing the zinc chelator EDTA (1 mm), followed by several rinses with distilled water.

Figure 7. Voltage dependence of the effect of zinc on forward uptake current.

Experiments were carried out using chloride-free, gluconate-containing solutions to avoid any contamination from current generated by the anion conductance in the glutamate transporter (see Methods). Graphs show the fractional reduction produced by various free zinc concentrations of the uptake current evoked by 200 μm glutamate in 4 cells (as in Fig. 1) at −60 mV (A) and −20 mV (B). Free zinc concentrations were calculated taking into account binding of zinc by gluconate and glutamate. Smooth lines are Michaelis-Menten curves with the parameters shown in the insets (Km is the concentration giving a half-maximal reduction; Rmax is predicted reduction at high zinc doses).

Imaging zinc in retinal cells

We attempted to image the intracellular zinc concentration in slices of retina, using the dye N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluenesulfonamide (TSQ, Molecular Probes). TSQ was made up as a 3 mm stock in DMSO (Jindal, Gray, McShane & Morris, 1993) or as a 45.7 mm stock in hot ethanol (Tatsumi & Fliss, 1994). These stocks were then diluted to give a final TSQ concentration of 30–100 μm in the external solution described above containing 105 mm NaCl, and cells were loaded by bathing them in this solution for 45 min at room temperature (21–25°C). Fluorescence of TSQ was excited at 380 nm wavelength and collected at 485 nm. Fluorescence intensity at different locations in the retinal slice was quantified using a digital imaging system (Kinetic Imaging) with a cooled CCD camera (Digital Pixel 2000).

Data analysis

Currents in zinc were always compared with the means of control responses recorded immediately before and after the zinc was applied. Statistics on the data are presented as means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

Zinc inhibits glutamate uptake

The glutamate transporter in Müller cells can produce a membrane current by the transport of glutamate into the cells with two or three Na+ ions (while one K+ ion is transported out of the cell, and either an OH− ion is transported out or an H+ ion is transported in), or by allowing anions to flow through an anion conductance associated with the transporter (Bouvier, Szatkowski, Amato & Attwell, 1992; Billups et al. 1996; Eliasof & Jahr, 1996; Zerangue & Kavanaugh, 1996). With Cl− as the main anion inside and outside the cell, applying glutamate at a negative potential evokes an inward current (Fig. 1A) that is generated largely by glutamate transport, because Cl− is poorly permeant through the anion conductance (Billups et al. 1996; Eliasof & Jahr, 1996). Barbour et al. (1991) and Billups et al. (1996) found, respectively, only a 12% and a 26% reduction of the current on replacing most of the internal Cl− with the much less permeant anion gluconate−. Zinc inhibited the glutamate-evoked current (Fig. 1A).

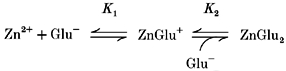

Figure 1. Inhibition of forward glutamate uptake by external zinc.

A, specimen data showing current evoked in one cell at −60 mV by 200 μm glutamate (filled bars) in control solution, and then in solutions in which different concentrations of free zinc were present. B, dose-response curve (means ±s.e.m., n = 4 cells) for the effect of zinc, using data as in A, quantified by measuring currents in zinc relative to the mean of bracketing control data. Smooth line is a fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation R =Rmax[Zn2+]/([Zn2+]+Km). Mean and s.e.m. values for the parameters of the fitted curve (inset; Km is the concentration giving a half-maximal reduction, Rmax is the predicted reduction at high zinc doses) were obtained by fitting a separate curve to the data from each cell and averaging the resulting parameters. The anion conductance of the carrier contributes to glutamate-evoked currents in this experiment, but the effect of zinc was essentially identical when the anion conductance was abolished by removal of Cl− (Fig. 7A).

A greater inhibition of the glutamate-evoked current was found at high zinc concentrations. The dependence of the inhibition on free zinc concentration could be fitted roughly by a Michaelis-Menten equation with a Km of 0.66 μm (Fig. 1B) and a maximum reduction of around 45%. If the inhibition were plotted as a function of total, instead of free zinc concentration in Fig. 1B, then the Km would be 0.84 μm. When Cl− in the internal and external solutions was replaced with gluconate, with the aim of abolishing any small contribution to the glutamate-evoked current of current flow through the anion conductance (Wadiche et al. 1995), a similar inhibition of the uptake current was seen (as shown in Fig. 7).

Since low levels of zinc could inhibit uptake, we tested whether any trace zinc in the control solution (nominally zinc free) might be tonically inhibiting uptake. To test this we included 1 mm EDTA in the control solution, which is calculated to reduce a trace zinc concentration of (say) 1 μm to 6 pM. Since this concentration of EDTA will also lower the calcium concentration from 3 to 2 mm, we compared the EDTA-containing solution with control solution containing only 2 mm CaCl2. The current evoked by 200 μm glutamate in three cells was found to be reduced by only 1.5 ± 3.2% with EDTA (data not shown), showing that trace levels of zinc were negligible in the control solution.

Since glutamate binds to zinc (see Methods), we considered the possibility that it might be a zinc-glutamate complex that blocks the operation of the transporter, rather than free zinc. To test this we compared the suppressive effect of solutions containing 1 μm free zinc but differing concentrations of zinc bound to glutamate. Calculations using the equations described in the Methods showed that for 1 μm free zinc and a free glutamate concentration of 200 μm and 600 μm (both saturating doses for uptake), the concentrations of zinc bound to glutamate are 0.27 μm and 0.83 μm, respectively (almost all of these amounts, 99.3 and 97.4%, respectively, being in the form of ZnGlu+). Thus, if it was glutamate-bound zinc that stops uptake, the effect of a solution containing 1 μm free zinc should be greater when using 600 μm than when using 200 μm free glutamate (provided that the ZnGlu+ does not block transport by competing with glutamate for binding to the transporter). Experimentally, the suppression by zinc was similar (actually slightly smaller, by 15 ± 7% in three cells) with 600 μm glutamate, implying that it is free zinc that inhibits the transporter. It could still be argued that perhaps ZnGlu+ binds to the glutamate transport site, in which case the 3-fold increase in [ZnGlu+] and [Glu] used in this experiment would not result in any difference in zinc inhibition. However, for 0.27 μm ZnGlu+ to inhibit the uptake current produced by 200 μm glutamate by 27% (Fig. 1B, point for 10−6 M zinc), it would require that the transporter could recognize ZnGlu+, a species with two positive charges and one negative charge, with an affinity that is about 300 times higher than that for glutamate (calculated assuming simple competitive inhibition). We cannot rule out such a possibility, but we are unaware of any species with two positive charges and one negative charge being recognized by glutamate transporters, and to be recognized with such a high affinity seems extremely unlikely.

Zinc inhibits reversed uptake

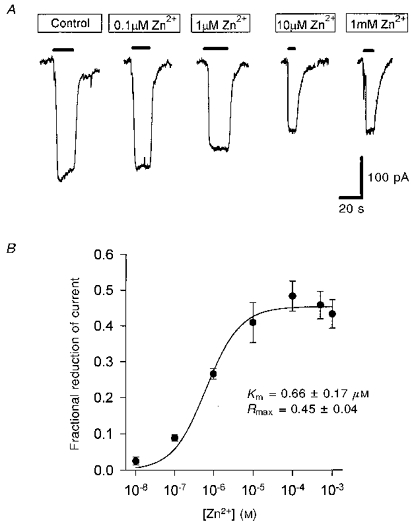

During brain or retinal ischaemia or hypoxia, the rise in extracellular potassium concentration ([K+]o) and internal sodium concentration is thought to result in glutamate transporters reversing their operation and releasing glutamate (Szatkowski & Attwell, 1994; Roettger & Lipton, 1996). This reversed uptake can be recorded (Fig. 2A) as an outward membrane current evoked by a rise in [K+]o in cells clamped to a depolarized potential with electrodes containing glutamate and sodium (Szatkowski et al. 1990). Zinc inhibited the reversed uptake current (Fig. 2A), and the dependence of inhibition on zinc concentration could be roughly fitted by a Michaelis-Menten equation (Fig. 2B). The Km of the best-fit curve was 1 μm, i.e. slightly (but not significantly) higher than that for inhibition of forward uptake, and the maximum reduction was around 40%, similar to that for the inhibition of forward uptake.

Figure 2. Inhibition of glutamate transport out of the cell (reversed uptake) by external zinc.

A, specimen data from one cell showing reversed uptake currents, evoked at +20 mV by raising the extracellular potassium concentration (filled bars) from 0 to 30 mm, in the presence of various free zinc concentrations. B, dose-response curve for the fractional reduction of current produced by different doses of zinc (each point shows data (means ±s.e.m.) from 4–10 cells). Smooth curve is a best-fit Michaelis-Menten equation (inset; Rmax is the predicted fractional reduction at a saturating zinc concentration, Km is the concentration giving a half-maximal reduction). The anion conductance of the carrier was not eliminated in this experiment or in those of Figs 3–5, but the similarity of the dose-response curves in Figs 1 and 7A, without and with the anion conductance eliminated, suggests that it has little effect on the results.

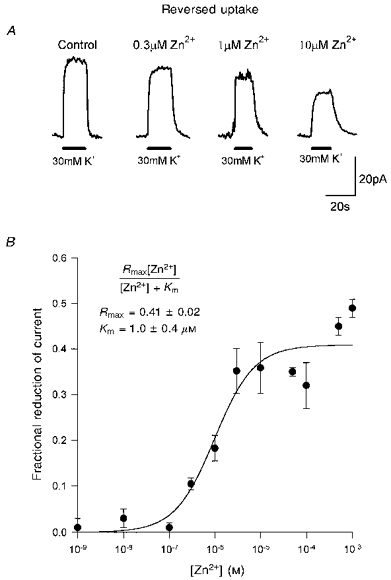

Zinc is not a simple competitive inhibitor of glutamate binding

Since zinc is charged, it could act by binding to a site which recognizes the positively charged amino group on glutamate, and thus prevent glutamate binding. To test this we measured the dose-response curve for glutamate activating a forward uptake current in the presence and absence of 8 μm zinc (Fig. 3A). Michaelis-Menten best fits to the data (Fig. 3B) showed that zinc did decrease the apparent affinity of the transporter for glutamate (the Km increased from 7.3 to 13.1 μm). However, the current at a saturating glutamate concentration was reduced by 23% in zinc, showing that it is not a simple competitive inhibitor.

Figure 3. Effect of external zinc on the glutamate dependence of the forward uptake current.

A, specimen data from one cell showing inward currents evoked at −60 mV in control solution (top panel) and in solution containing 8 μm free zinc (bottom panel) in response to different free glutamate concentrations. B, dose-response curves for the current produced by glutamate (from data as in A, for 6 cells) normalized to the current produced in control solution by 300 μm glutamate. Smooth curves are Michaelis-Menten best fits (inset; Imax is the value of normalized current for a saturating glutamate concentration, Km is the concentration giving a half-maximal current).

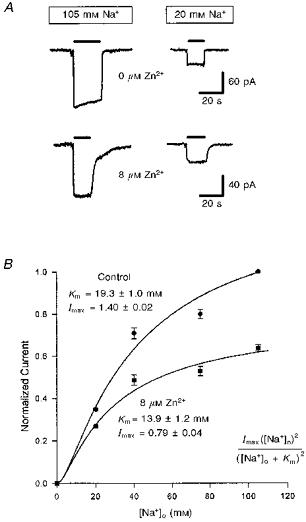

Zinc is not a competitive inhibitor at the Na+-binding site

To test whether zinc inhibits transport by competing for the Na+-binding site on the transporter, we measured the sodium dependence of the forward uptake current produced by 200 μm glutamate in the presence and absence of zinc (Fig. 4A). The data could be approximately fitted by the square of a Michaelis-Menten equation both with and without zinc present (Fig. 4B; cf. Barbour et al. 1991). Zinc reduced the current which these fits predicted would be produced at a saturating sodium concentration, and increased the apparent affinity for Na+. Thus, zinc does not compete for binding at the sodium site(s).

Figure 4. Effect of external zinc on the sodium dependence of the glutamate uptake current.

A, specimen data showing the effect of 8 μm free zinc on currents evoked at −60 mV by 200 μm free glutamate (filled bars) in normal solution (105 mm Na+, left traces) or in solution containing only 20 mm Na+ (replaced with choline, right traces). Data in zinc have been normalized (note different current scales) so that the response in 105 mm Na+ is the same as in control solution, to facilitate comparison of the relative sizes of response in 20 mm Na+. External solution was the 105 mm sodium solution described in the Methods. B, dependence of the glutamate-evoked current on external sodium concentration for 5 cells in solutions lacking zinc (circles) and containing 8 μm zinc (squares). Data are normalized to the response in normal solution with 105 mm [Na+]o. Smooth curves are the square of a Michaelis-Menten equation (inset) best fitted to the data. Imax is the normalized current predicted at a saturating sodium concentration; Km is the sodium concentration at which the normalized current is quarter-maximal.

Zinc is not a competitive inhibitor at the K+-binding site

To assess whether zinc acted at the K+-binding site of the transporter, we examined the K+ dependence of transport using reversed operation of the carrier. This allowed us to apply different potassium concentrations to the same cell, since K+ binds at the outer membrane surface during reversed uptake. Zinc (30 or 300 μm, a saturating dose) reduced the reversed uptake current by a similar fraction at all potassium concentrations (Fig. 5A and B). Michaelis- Menten fits to the [K+]o dependence of the current (Fig. 5B) showed that zinc had no significant effect on the apparent affinity for K+, but reduced the current at a saturating potassium concentration. Thus, zinc is not a competitive inhibitor of K+ binding.

Figure 5. Effect of zinc on the [K+]o dependence of the reversed uptake current.

A, specimen data showing the effect of 30 μm free zinc on currents evoked in one cell at +20 mV by raising the external potassium concentration (filled bars) from 0 to 30 mm (left traces) or from 0 to 8 mm (right traces) around cells containing 10 mm sodium glutamate. Data from cells in zinc have been normalized (note different current scales) so that the response to 30 mm K+ is the same as in control solution, to facilitate comparison of the relative sizes of response to 8 mm K+. B, potassium dependence of the reversed uptake current in 7 cells, in the absence (circles) or presence (squares) of 300 μm zinc. Data are normalized to the current produced by 30 mm K+ in the absence of zinc. Smooth curves are Michaelis-Menten equations (inset) best fitted to the data. Imax is the normalized current predicted to be produced at a saturating [K+]o; Km is the potassium concentration at which the current is half-maximal.

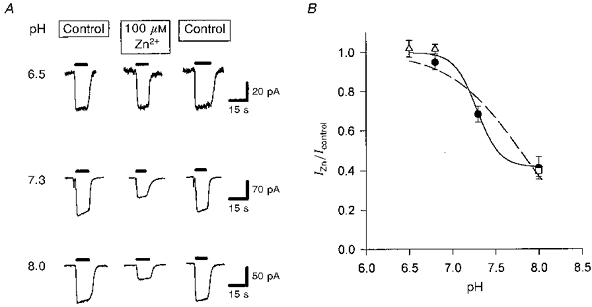

The effect of zinc at different extracellular pH values

Since glutamate transport is accompanied by the co-transport of H+ or the counter-transport of OH−, we investigated whether the action of zinc was pH dependent. For these experiments the equilibrium constants used to calculate the free zinc and glutamate concentrations (see Methods) were adjusted appropriately for each pH studied, and the experiments were carried out with intra- and extracellular chloride replaced by gluconate to ensure that none of the glutamate-evoked current measured was contributed by the anion channel in the carrier (see Methods and below).

The forward uptake current increases as the extracellular pH is lowered from 9 to 7 (Billups & Attwell, 1996), presumably due to an increased concentration of co-transported H+ or reduced rebinding of OH− to an OH− counter-transport site. We found that the suppressive effect of zinc on the uptake current was reduced at a more acid pH (Fig. 6), and was essentially absent at pH 6.5. A reduction of this sort might be expected if zinc competed for binding at an H+-binding site. However a simple competitive binding of Zn2+ (non-transported) to an H+ transport site is ruled out by the fact that even at high zinc doses the uptake current is only half suppressed (Fig. 1). A plausible explanation of the data is that protons can titrate a zinc-binding site which is separate from the substrate-binding sites on the carrier.

Figure 6. Effect of zinc on glutamate uptake at different external pH values.

A, specimen data showing currents evoked at −60 mV by 200 μm glutamate (filled bars) in control solution, in solution containing 100 μm free zinc, and again in control solution (data from a different cell for each pH value). Experiments were done using gluconate-containing solutions (see Methods) to avoid any contamination from current generated by the anion channel in the glutamate transporters. B, mean data from experiments like that in A on 4 cells (except 3 cells for pH 6.5 and 10 cells for pH 7.3), showing the suppression by zinc of the uptake current as a function of pH. Filled circles, Hepes used as a pH buffer. Open triangles and open square, 5 mm Taps and Mes, respectively, used as a pH buffer. The fitted curves have the form: IZn/Icontrol =A+[(1 - A)HN/(HN+KN)], with H =[H+] and constants A = 0, K = 1.64 × 10−8 and n = 1.047 (dashed line; assumes response is completely suppressed by zinc at very alkaline pH), or A = 0.417, K = 5.18 × 10−8 and n = 3.36 (smooth line; allows response to be incompletely suppressed by zinc at very alkaline pH).

Zinc can only act from the outer membrane surface

We considered the possibility that zinc can only act on the side of the carrier where glutamate and sodium bind (the outside for forward uptake, and the inside for reversed uptake). To test this, we investigated the effect of including 100 μm free zinc in the whole-cell pipette solution on both forward and reversed uptake currents (Cl− was the main anion present, as in Fig. 1). Separate cells were studied for pipette solutions containing or lacking zinc (alternating between control and zinc cells), and data were normalized by cell capacitance to compensate for variations in cell size (Barbour et al. 1991).

The forward uptake current produced at −60 mV by 300 μm glutamate was 0.67 ± 0.08 pA pF−1 in five cells without zinc inside, and 0.80 ± 0.16 pA pF−1 in five cells with zinc inside (n.s.; P = 0.49 on Student's 2-tailed t test). The reversed uptake current evoked at +20 mV by 30 mm [K+]o was 0.47 ± 0.04 pA pF−1 in five cells without zinc inside and 0.49 ± 0.03 pA pF−1 in four cells with zinc inside (n.s.; P = 0.71). Thus, internal zinc does not inhibit glutamate transport.

The voltage dependence of the action of zinc

If zinc acts from outside the cell membrane but has to reach a site within the electric field of the membrane to inhibit glutamate transport, it might be expected to have a greater suppressive effect at negative potentials, which would pull Zn2+ more into the membrane. We examined the reduction of forward uptake current produced by 80 μm zinc over a range of membrane potentials. Although with Cl− as the main anion present the anion conductance of the transporter makes only a small contribution to the glutamate-evoked current at negative potentials (Barbour et al. 1991; Billups et al. 1996), at depolarized potentials, when the current associated with glutamate transport is small, the current flowing through the anion conductance may be more significant. To examine the effect of zinc on just the transport-associated current, we therefore replaced the Cl− in the internal and external solutions with the impermeant anion gluconate (Wadiche et al. 1995). The suppressive effect of zinc on the uptake current was independent of potential between −60 and −20 mV (Fig. 7), suggesting that zinc binds outside the membrane field.

Zinc potentiates the anion conductance of the glutamate transporter

To examine the effect of zinc on activation of the anion conductance in the carrier, we replaced 50 mm Cl− in the external solution with the more permeant anion NO3− (see Methods). Activation of the anion conductance, when the carrier transports glutamate, leads to glutamate producing a net outward current at positive potentials, as a result of the more permeant NO3− anions entering the cell through the anion conductance generating an outward current that is larger than the inward current associated with the transport of glutamate and Na+ into the cell (Billups et al. 1996; Eliasof & Jahr, 1996). Figure 8A shows glutamate-evoked currents at −10 mV, with Cl− as the internal anion, and with Cl− or NO3− outside the cell.

Figure 8. Effect of zinc on the anion conductance in the glutamate transporters of Müller cells.

A, potentiation by zinc of the anion conductance in the Müller cell glutamate transporter with potassium present inside the cell. Traces show currents evoked at −10 mV by 200 μm glutamate (filled bars), with and without 80 μm zinc present, in normal external solution (Cl−) and in solution containing 50 mm NO3−. See text for interpretation. B, potentiation by zinc of the anion conductance in the Müller cell glutamate transporter with no potassium present (to block net glutamate transport), with sodium and glutamate present inside the cell, and with 50 mm NO3− present outside the cell. Traces are currents evoked at −20 mV by 200 μm glutamate in the absence and presence of 100 μm zinc. C, dependence of the potentiation of anion current (as in B) on zinc concentration. Data are from 5 cells (except for 10−6 M: 4 cells), and the curve is a Michaelis-Menten best fit with the parameters shown in the inset (Km is the concentration giving a half-maximal potentiation, Pmax is the predicted potentiation at high zinc doses: accuracy of the derived Pmax may be limited by the lack of data above 100 μm zinc).

In Cl− Ringer solution, the glutamate-evoked inward current was reduced by zinc, as described above. With NO3− outside the cell, glutamate evoked a net inward current in the absence of zinc (due to the inward transport-associated current still dominating the total current at the potential of −10 mV chosen for the experiment), but the current in the presence of zinc was outward. We show below that this is not simply due to zinc reducing the inward transport component of the current, but results partly from zinc increasing the outward current mediated by NO3− entry through the anion conductance, so that it now dominates the total current. Doing the experiment at a more positive potential, at which NO3− entry is large enough to make the glutamate-evoked current outward even without zinc present (Billups et al. 1996), resulted in zinc potentiating the net outward current.

To convert these current changes into a quantitative effect of zinc on the anion conductance, we assumed that the total current generated by the transporter is the sum of two components: a transport component (Itransport) and a component flowing through the anion conductance (cf. Wadiche et al. 1995). We also assumed that anion substitution alters the latter component but not the transport current (Billups et al. 1996, showed that this assumption is correct when replacing Cl− with NO3−). Zinc is then assumed to multiply the transport current by a factor f (about 0.45 at the saturating dose used, from Figs 1 and 7), and the anion current by a factor g (to be determined). Thus, the net current flowing with Cl− present in the absence and presence of zinc is:

and

respectively. Similarly, the net current with NO3− present is:

and

Thus,

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

From eqns (1) and (2), the factor by which the anion current is altered by zinc can be obtained as:

| (3) |

Using this equation, data like those in Fig. 8 were used to calculate that in five cells with 80 μm zinc the mean value of g was 1.31 ± 0.08. Thus, zinc potentiates activation of the anion conductance.

To confirm that zinc potentiates the anion conductance without the complications of interpretation arising from subtracting the transport component of the carrier current, we made use of the discovery (Billups et al. 1996) that external glutamate can activate the anion conductance without net glutamate transport (and an associated transport current) occurring if (i) K+ is removed from the internal and external solutions (since K+ counter-transport is needed for net glutamate transport: Kanner & Sharon, 1978) and (ii) Na+ and glutamate are present inside the cell. Figure 8B shows glutamate-evoked currents recorded with the anion current isolated in this way, using NO3− outside the cell to increase the size of the current (the currents were recorded at −20 mV; because external NO3− is more permeant than internal Cl−, the anion current at −20 mV is dominated by NO3− entry and so is outward). Zinc (100 μm) potentiated the anion current by a factor of 1.52 ± 0.03 in five cells. Interestingly, the dose-response curve for zinc potentiating the anion current had a significantly higher Km (about 10 μm, Fig. 8C) than for zinc inhibiting uptake (0.66 μm, Fig. 1).

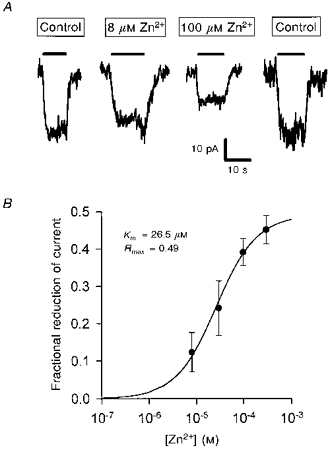

Since zinc potentiated the anion conductance in the Müller cell transporter, we tested its effects on the current generated by glutamate in the synaptic terminals of salamander retinal cones (Sarantis et al. 1988). This current, like that generated by the mammalian EAAT5 transporter (Arriza, Eliasof, Kavanaugh & Amara, 1997), is generated almost entirely by Cl− flux through an anion conductance in the cone synaptic terminal glutamate transporter (Sarantis et al. 1988; Eliasof & Werblin, 1993) since the current is almost abolished by removal of internal and external chloride (Picaud et al. 1995). Contrary to its effect on the Müller cell transporter anion conductance, zinc decreased the current generated at −60 mV by the cone transporter anion conductance (Fig. 9A), and the Km for this effect was greater than that for zinc inhibiting uptake or potentiating the anion conductance in the Müller cell (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9. Zinc reduces the current through the anion conductance in the cone synaptic terminal glutamate transporter.

A, traces are the current (almost entirely through the anion conductance, see main text) evoked at −60 mV by 200 μm glutamate (filled bars) in control solution, in the presence of 8 μm and 100 μm zinc, and then in control solution again. These experiments used the 105 mm sodium external solution described in the Methods. B, mean reduction of the current, measured as in A, in 10, 5, 9 and 5 cells to which 8, 30, 100 and 300 μm zinc, respectively, were applied. Curve is a Michaelis-Menten equation with the parameters shown in the inset (Rmax is the predicted reduction at high zinc doses; Km is the concentration giving a half-maximal reduction: standard errors are not given for these parameters because some cells were only studied with one zinc concentration, preventing the fitting of a Michaelis-Menten curve for those cells).

Attempts to image zinc release in retinal slices

Wu et al. (1993) reported that in the retina, zinc is present presynaptically in photoreceptors, raising the possibility that exocytosis of zinc from photoreceptors could influence glutamate uptake into Müller cells. We attempted to image zinc using a fluorescent zinc-sensitive dye in living retinal slices, with the aim of showing a release of zinc from photoreceptors when they were depolarized with potassium. For these experiments the slices were kept in the light to ensure that the photoreceptors were hyperpolarized before potassium was applied. TSQ has been reported to be usable as an indicator of intracellular zinc in living cells (Jindal et al. 1993; Tatsumi & Fliss, 1994). We found that it labelled the outer segments of the photoreceptor most strongly, whilst producing weaker labelling of other retinal layers. The fluoresence at all locations in the slice was increased by including 1 μm zinc in the external solution, and was greatly reduced by the membrane-permeant zinc chelator TPEN (N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine; 2 μm). However it was also decreased to a similar extent by the supposedly membrane-impermeant chelator EDTA (3.3 mm, chosen to give a similar chelating power to 2 μm TPEN, data not shown). We concluded that the dye was mainly reporting zinc bound at the outer membrane surface. Raising the external potassium concentration to 60 mm had no detectable effect on the fluorescence anywhere in the retinal slice (three slices, data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Zinc inhibits the salamander Müller cell glutamate transporter

The data presented above show that there is a modulatory site which binds zinc on the glutamate transporter in salamander retinal glial cells. Zinc has two effects when it binds, reducing the uptake of glutamate but potentiating activation of the anion conductance in the transporter. It is possible that these two effects are linked: for example zinc could slow glutamate transport by prolonging the time the transporter spends in the sodium- and glutamate-bound state, which has been postulated to allow opening of the anion conductance (Billups et al. 1996). However, the requirement for a 10-fold higher zinc concentration to potentiate the anion conductance than to inhibit uptake (Figs 1 and 8) may suggest two independent effects.

The mechanism by which zinc affects uptake is uncertain, as it does not work by simply blocking competitively the activation of the transporter by glutamate, Na+, K+ or H+. Zinc decreased the uptake current at saturating concentrations of glutamate, Na+ and K+, while decreasing, increasing, and having no effect on (respectively) the affinities for these substrates. The effect of zinc was abolished at acid pH, possibly because protons can titrate the site to which Zn2+ binds. We considered the possibility that zinc might bind to sulfhydryl groups on the transporter and found that its action was blocked by dithiothreitol (2 mm) - a strategy used by others to test the hypothesis that zinc binds to -SH groups (Yamaguchi, 1993). However, dithiothreitol is a strong zinc chelator (Cornell & Crivaro, 1972), invalidating this approach.

The effect of zinc on the glutamate-evoked current generated by the transporter was similar with Cl− present, allowing the anion conductance to generate current, or with Cl− absent to abolish the anion conductance (Figs 1 and 7A), consistent with the small contribution of the anion conductance to the glutamate-evoked current in these cells (Barbour et al. 1991; Billups et al. 1996). Thus, although the anion conductance was not abolished for experiments on the glutamate and Na+ dependence of the transporter current, the currents in Figs 3 and 4 are dominated by the current associated with glutamate transport.

Other properties of the salamander glial transporter, such as the transport of K+ (Barbour et al. 1988), the transport of a pH-changing ion (Bouvier et al. 1992), and modulation by arachidonic acid (Barbour, Szatkowski, Ingledew & Attwell, 1989), have been found to be shared by mammalian glutamate transporters, so it seems likely that mammalian transporters will also be directly modulated by zinc, consistent with the radiotracing study of Gabrielsson et al. (1986). Homologues of several mammalian glutamate transporters are found in Müller cells (Eliasof, Arriza, Amara & Kavanaugh, 1997), but the insensitivity of the glutamate-evoked current to dihydrokainate (Barbour et al. 1991; Arriza et al. 1994), and the relatively small anion conductance activated by glutamate transport (Billups et al. 1996), suggest that the glutamate-evoked current is generated largely by transporters homologous to the mammalian GLAST/EAAT1. The fact that zinc potentiated anion conductance activation in this transporter (Fig. 8) but depressed it in the salamander cone synaptic terminal transporter (Fig. 9), which is homologous to the mammalian EAAT5 (Arriza et al. 1997), suggests that zinc has different effects on different subtypes of glutamate transporter. Differential effects of arachidonic acid on different transporter subtypes have similarly been reported (Zerangue, Arriza, Amara & Kavanaugh, 1995).

Relationship between the zinc dose needed to block uptake and the zinc levels occurring in vivo

Zinc blocked glutamate uptake with an IC50 of around 0.66 μm for the free zinc present (0.84 μm for the total zinc present). A wide range of half-maximally effective doses has been reported for the effect of zinc on voltage-gated calcium channels and postsynaptic glutamate- and GABA-gated channels (see references in the Introduction, and Smart et al. 1994), but in general the IC50 we found for zinc blocking glutamate uptake was 1- to 100-fold less than those doses. Thus, if zinc has effects on those channels in vivo, it must also affect glutamate uptake.

Wensink, Molenaar, Woroniecka & Van den Hamer (1988) estimated that the free zinc concentration in the extracellular space of the CNS is about 10 nm. This will have little tonic suppressive effect on the rate of glutamate uptake (from Fig. 1). To investigate by how much neuronal activity increases the extracellular zinc concentration, Assaf & Chung (1984) depolarized hippocampal mossy fibres with potassium and measured the zinc released into the superfusate. The highest increase in the superfusate zinc concentration (total, not free) measured was 200 nm. Because of dilution into the superfusion solution, Assaf & Chung (1984) therefore estimated the extracellular concentration within the slice to rise to 300 μm, but this was calculated by assuming that all the zinc collected over a period of 12 min was released into the extracellular space at the same time. A better estimate can be obtained by scaling up the superfusate concentration of 200 nm by the ratio of the superfusate volume (3.98 ml) to the volume of the extracellular space in the slices studied (15% of the volume of 45 mg wet weight), i.e. by about 590 (3.98/(0.15 × 0.045)), giving a concentration of 118 μm. Spatial non-uniformity in the release of zinc (e.g. if it were only released from the mossy fibres) would increase this value, which is already a saturating dose for zinc blocking either forward or reversed uptake (Figs 1 and 2).

The Müller cells we have studied are the major type of glial cell present in the retina, so modulation of their rate of glutamate uptake might have an important effect on retinal information processing. Zinc is present in retinal photoreceptors and has been suggested by Wu et al. (1993) to act as a neuromodulator in the retina, but they presented no evidence that it is released into the extracellular space, and our imaging experiments were uninformative in this regard. At present it is unclear, therefore, how high the extracellular zinc concentration rises in the retina.

Possible physiological and pathological consequences of zinc modulating glutamate transport

Inhibition of glutamate uptake by zinc released during normal synaptic activity will tend to raise the background level of glutamate. This will decrease the amplitude of synaptic currents by desensitizing postsynaptic glutamate receptors, and may also slow the removal of glutamate from the synaptic cleft and thus prolong the synaptic current (both these effects are seen when glutamate uptake blockers are applied to glutamatergic synapses on cerebellar Purkinje cells: Barbour, Keller, Llano & Marty, 1994; Takahashi, Kovalchuk & Attwell, 1995). Thus, the net result may be little change in the charge transfer produced by a postsynaptic current, but a prolongation of the time over which it occurs, which will promote temporal integration of input signals by neurons.

Zinc release may accompany the massive depolarization of neurons which occurs during brain ischaemia (Koh et al. 1996). This will inhibit the release of glutamate that occurs by reversed operation of glutamate transporters at this time (Szatkowski & Attwell, 1994; Roettger & Lipton, 1996). The 40% slowing of reversed uptake that a high zinc concentration produces will not prevent the extracellular glutamate concentration rising to neurotoxic levels if the ischaemia is sustained, but will prolong the time needed for glutamate to rise. If the ischaemia is only transient, this prolongation could be neuroprotective, as has been postulated for the inhibitory effect of an acid pH on reversed uptake (Billups & Attwell, 1996).

Excessive levels of extracellular zinc in the CNS could be expected to inhibit glutamate uptake and thus cause neuronal degeneration, as occurs when glutamate transporter expression is prevented (Rothstein et al. 1996). Interestingly, there is a form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with eating flour contaminated with zinc (Duncan, Marini, Watters, Kopin & Markey, 1992).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust, European Community (BMH4 CT95-871), an MRC Studentship to Brian Billups, a British Council Studentship to Mona Spiridon and a Wellcome Trust Vacation Studentship to Daniela Kamm.

References

- Arriza JL, Eliasof S, Kavanaugh MP, Amara S. Excitatory amino acid transporter 5, a retinal glutamate transporter coupled to a chloride conductance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:4155–4160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4155. 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriza JL, Fairman WA, Wadiche JI, Murdoch GH, Kavanaugh MP, Amara S. Functional comparisons of three glutamate transporter subtypes cloned from human motor cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:5559–5569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05559.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf SY, Chung SH. Release of endogenous Zn2+ from brain tissue during activity. Nature. 1984;308:734–738. doi: 10.1038/308734a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Werblin FS, Wilson M. The properties of single cones isolated from the tiger salamander retina. Journal of Physiology. 1982;328:259–283. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Brew H, Attwell D. Electrogenic glutamate uptake is activated by intracellular potassium. Nature. 1988;335:433–435. doi: 10.1038/335433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Brew H, Attwell D. Electrogenic uptake of glutamate and aspartate into glial cells isolated from the salamander retina. Journal of Physiology. 1991;436:169–193. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Keller BU, Llano I, Marty A. Prolonged presence of glutamate during excitatory synaptic transmission to cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1994;12:1331–1343. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Szatkowski M, Ingledew N, Attwell D. Arachidonic acid induces a prolonged inhibition of glutamate uptake into glial cells. Nature. 1989;342:918–920. doi: 10.1038/342918a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billups B, Attwell D. Modulation of non-vesicular glutamate release by pH. Nature. 1996;379:171–174. doi: 10.1038/379171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billups B, Rossi D, Attwell D. Anion conductance behavior of the glutamate uptake carrier in salamander retinal glial cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:6722–6731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06722.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier M, Szatkowski M, Amato A, Attwell D. The glial cell glutamate uptake carrier countertransports pH-changing anions. Nature. 1992;360:471–473. doi: 10.1038/360471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl EH, Otis TS, Mody I. Zinc-induced collapse of augmented inhibition by GABA in a temporal lobe epilepsy model. Science. 1996;271:369–373. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busselberg D, Platt B, Michael D, Carpenter DO, Haas HL. Mammalian voltage-activated calcium channel currents are blocked by Pb2+, Zn2+ and Al3+ Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:1491–1497. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell NW, Crivaro KE. Stability constant for the zinc-dithiothreitol complex. Analytical Biochemistry. 1972;47:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90293-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford IL, Connor JD. Zinc in maturing rat brain: hippocampal concentration and localisation. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1972;19:1451–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb05088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson RMC, Elliott DC, Elliott WH, Jones KM. Data for Biochemical Research. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MW, Marini AM, Watters R, Kopin IJ, Markey SP. Zinc, a neurotoxin to cultured neurons, contaminates cycad flour prepared by traditional Guamanian methods. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:1523–1537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01523.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasof S, Arriza JL, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Immunocytochemical localization of 5 glutamate transporters cloned from salamander retina. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1997;38(suppl.):1434. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Eliasof S, Jahr S. Retinal glial cell glutamate transporter is coupled to an anionic conductance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:4153–4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4153. 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasof S, Werblin F. Characterization of the glutamate transporter in retinal cones of the tiger salamander. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;113:402–411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00402.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson CJ. Neurobiology of zinc and zinc-containing neurons. International Reviews of Neurobiology. 1989;31:145–238. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson B, Robson T, Norris D, Chung SH. Effects of divalent metal ions on the uptake of glutamate and GABA from synaptosomal fractions. Brain Research. 1986;384:218–223. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91157-1. 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hexum TD. Studies on the reaction catalyzed by transport (Na, K)adenosine triphosphatase. I. Effects of divalent metals. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1974;23:3441–3447. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90347-5. 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GA, Welch MG, Frederickson CJ. Stimulation-induced uptake and release of zinc in hippocampal slices. Nature. 1984;308:736–738. doi: 10.1038/308736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal RM, Gray DWR, McShane P, Morris PJ. Zinc-specific N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-para-toluenesulfonamide as a selective nontoxic fluorescence stain for pancreatic islets. Biotechnic and Histochemistry. 1993;68:196–205. doi: 10.3109/10520299309104698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner BI, Sharon I. Active transport of L-glutamate by membrane vesicles isolated from rat brain. Biochemistry. 1978;17:3949–3953. doi: 10.1021/bi00612a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J-Y, Suh SW, Gwag BJ, He YY, Hsu CY, Choi DW. The role of zinc in selective neuronal death after transient global cerebral ischemia. Science. 1996;272:1013–1016. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Clausell J, Danscher G. Intravesicular localization of zinc in rat telencephalic boutons. A histochemical study. Brain Research. 1985;337:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91612-9. 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picaud SA, Larsson HP, Grant GB, Lecar H, Werblin FS. Glutamate-gated chloride channel with glutamate-transporter-like properties in cone photoreceptors of the tiger salamander. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:1760–1771. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roettger V, Lipton P. Mechanism of glutamate release from rat hippocampal slices during in vitro ischemia. Neuroscience. 1996;75:677–685. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00314-4. 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, Bristol LA, Jin L, Kuncl RW, Kanai Y, Hediger MA, Wang Y, Schielke J, Welty DF. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;16:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantis M, Everett K, Attwell D. A presynaptic action of glutamate at the cone output synapse. Nature. 1988;332:451–453. doi: 10.1038/332451a0. 10.1038/332451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart TG, Xie X, Krishek BJ. Modulation of inhibitory and excitatory amino acid receptor ion channels by zinc. Progress in Neurobiology. 1994;42:393–441. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90082-5. 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RM, Martell AE. Critical Stability Constants. New York and London: Plenum Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Stengaard-Pedersen K, Fredens K, Larsson LI. Comparative localization of enkephalin and cholecystokinin immunoreactivities and heavy metals in the hippocampus. Brain Research. 1983;273:81–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91097-1. 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatkowski M, Attwell D. Triggering and execution of neuronal death in brain ischaemia: two phases of glutamate release by different mechanisms. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:359–365. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90040-x. 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90040-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatkowski M, Barbour B, Attwell D. Non-vesicular release of glutamate from glial cells by reversed electrogenic glutamate uptake. Nature. 1990;348:443–446. doi: 10.1038/348443a0. 10.1038/348443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Kovalchuk Y, Attwell D. Pre- and postsynaptic determinants of EPSC waveform at cerebellar climbing fiber and parallel fiber to Purkinje cell synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:5693–5702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05693.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi T, Fliss H. Hypochlorous acid mobilizes intracellular zinc in isolated rat heart myocytes. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1994;26:471–479. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1058. 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadiche JI, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Ion fluxes associated with excitatory amino acid transport. Neuron. 1995;15:721–728. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90159-0. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensink J, Molenaar AJ, Woroniecka UD, Van den Hamer CJA. Zinc uptake into synaptosomes. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1988;50:782–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb02982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werblin FS. Transmission along and between rods in the tiger salamander retina. Journal of Physiology. 1978;280:449–470. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SM, Qiao X, Noebels JL, Yang XL. Localization and modulatory actions of zinc in vertebrate retina. Vision Research. 1993;33:2611–2616. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90219-m. 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90219-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M. Regulatory effects of zinc and copper on the calcium transport system in rat liver nuclei. Relation to SH groups in the releasing mechanism. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1993;45:943–948. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90180-5. 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Arriza JL, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Differential modulation of human glutamate transporter subtypes by arachidonic acid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:6433–6435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6433. 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Kavanaugh MP. Flux coupling in a neuronal glutamate transporter. Nature. 1996;383:634–637. doi: 10.1038/383634a0. 10.1038/383634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]