Abstract

We report here observations on the effects of muscle contraction history on thresholds for the detection of movements at the elbow joint of human subjects. Detection thresholds were measured in the direction of flexion or extension to movements of the relaxed forearm at a speed of 0.2 deg s−1 with the elbow at 90 deg.

As reported previously, thresholds for movements in the direction of extension were lower than in the direction of flexion after a conditioning co-contraction of elbow muscles with the arm flexed by 30 deg from its mid-position (hold-short). After a co-contraction with the arm held extended by 30 deg (hold-long), thresholds were lower in the direction of flexion.

Here we have made two additional observations. Thresholds for movements of the passive forearm after a co-contraction at the 90 deg test position (hold-test) were low, both in the direction of flexion and extension. Secondly, when thresholds were measured while subjects were carrying out a co-contraction of forearm muscles (15–20 % maximum voluntary contraction), thresholds were much higher.

It is concluded that muscle contraction history is an important factor to consider when making measurements of movement thresholds at the relaxed elbow joint. It is speculated that during an active contraction increases in muscle spindle discharges evoked by fusimotor activity lead to the rise in movement detection threshold.

It is generally agreed that muscle spindles contribute signals to the senses of position and movement of our limbs, kinaesthesia (McCloskey, 1978). We have sought additional evidence for a role of muscle spindles in kinaesthesia by taking advantage of a property unique to spindles, that of thixotropy (Proske, Morgan & Gregory, 1993). Spindles exhibit thixotropic behaviour in that their sensitivity to stretch depends on their previous history of contraction and length changes. By controlling for the muscle's previous history we have been able to produce systematic changes in the ability of human subjects to detect movements imposed at the elbow joint (Wise, Gregory & Proske, 1996).

During these experiments, subjects were asked to co-contract biceps and triceps with the arm held either flexed (hold-short) or extended (hold-long). After hold-short conditioning, with the arm placed in an intermediate position, thresholds measured for imposed movements into extension were systematically lower than for movements in the direction of flexion. Conversely, after hold-long conditioning, thresholds for flexion were lower than for extension. These findings were interpreted in terms of the presence or absence of slack in the spindles of the muscles which were being stretched by the movement.

With the experimental protocol used, spindles in biceps and triceps were left in different mechanical states. Thus, for example after hold-short conditioning, when the arm was moved to the 90 deg test position thereby stretching biceps, it left spindles in biceps taut and stretch sensitive. At the same time triceps was shortened and its spindles fell slack and became insensitive to stretch. It meant that after this form of conditioning, for imposed movements into extension there would be little, if any, activity coming from triceps; most of it would be coming from biceps. Since it is known that proprioceptive sensations may involve afferent inflow from both agonist and antagonist muscles (see, for example, Gilhodes, Roll & Tardy-Gervet, 1986), it left open the question of whether the central nervous system was able to access information from both members of the antagonist pair, when this was available. So, for example, if at the test length slack had been removed in both biceps and triceps, would the detection threshold for imposed movements have been lower, given that now there would be an increase in spindle discharge coming from the muscle undergoing stretch as well as a decrease from the muscle undergoing shortening? In other words, does the central nervous system use both the increases and decreases in spindle input from an antagonist pair to detect movements?

An obvious difficulty with muscle spindles as detectors of limb movements is that their output is not only determined by changes in muscle length but by the level of fusimotor activity. It is known that during a voluntary contraction there is co-activation of α- and fusimotor neurones. Potentially ambiguous signals about changes in muscle length would be generated if the fusimotor-evoked activity was not taken into account. It has been postulated that in the presence of fusimotor activity some kind of subtraction process must take place within the central nervous system to extract the stretch-evoked component from the total signal (McCloskey, Gandevia, Potter & Colebatch, 1983).

Here we have addressed two questions that arise directly from our previous work. Can the method of muscle conditioning be used to provide evidence in support of the idea that signals from both agonists and antagonists contribute to the detection of movements? Secondly, how do movement detection thresholds of the passive limb compare with the measured thresholds during a co-contraction of the two antagonists, when spindles are likely to be under fusimotor control?

A preliminary report of this work has been submitted in abstract form (Proske, Wise & Gregory, 1997).

METHODS

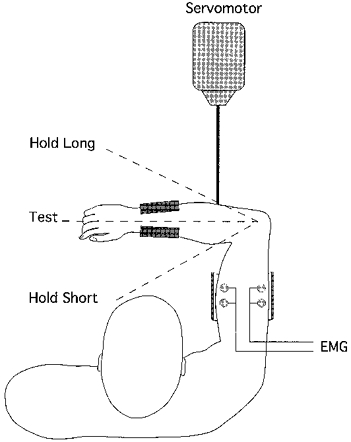

Experiments were carried out on eleven healthy young adults, six male and five female, aged 22–27 years. Informed consent had been obtained from each subject and the experiments were approved by a local human ethics committee. All subjects but one were right-handed. Blindfolded subjects were seated with their right arm held in the horizontal plane in front of them. The upper arm rested on a cushioned support and remained stationary throughout the experiment. An adjustable cuff was placed around the forearm just above the wrist, with the forearm held in a pronated position. The cuff was attached to a pivoted lever, permitting smooth movement in the horizontal plane only. The elbow joint was placed directly over the pivot point of the lever. The lever was attached to a motor with position feedback, allowing for controlled displacements at constant, predetermined velocities in either direction of extension or flexion (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of experimental set-up.

The right upper arm of the blindfolded subject rests on a padded support. A cuff is placed around the distal forearm. The cuff is attached to a horizontal lever and movements of this lever by a servomotor produce rotations of the forearm about the elbow. Conditioning and test positions are indicated. Hold-short conditioning is when a co-contraction is carried out with the forearm flexed by 30 deg from the 90 deg test position. Hold-long is when the co-contraction is carried out with the arm held extended by 30 deg from the test position. Hold-test is when a conditioning co-contraction is carried out at the test length.

Subjects were told to contract both biceps and triceps with their forearm either flexed (hold-short) or extended (hold-long) by 30 deg from its 90 deg mid-position. After the contraction, which was not necessarily maximal, subjects were asked to relax their arm. Ten seconds later the experimenter moved the passive forearm back to its 90 deg test position ready for application of a single movement. Subjects were told they had to report in which direction the arm was being moved, if it was moving at all. They were told not to guess and to say if they were unsure.

In a second experimental series, the arm was placed in its mid-position (hold-test) and subjects were asked to produce a co-contraction of both biceps and triceps. After subjects had relaxed, the test movement was imposed as before.

In a third protocol subjects were trained during a preliminary trial to develop a co-contraction of biceps and triceps at 15–20 % maximum voluntary contraction (MVC). This was achieved by first measuring EMG levels when subjects carried out an MVC. Then subjects were asked to generate submaximal contractions and when one was produced which gave an EMG that corresponded to approximately 20 % MVC, this was chosen as the target value. Subsequently, subjects were trained to develop co-contractions at this level of tension by providing them with a visual display of the target EMG. Once subjects could do this reasonably well, developing a co-contraction without a large bias in either the direction of flexion or extension, the experiment was started. Subjects were instructed that 4 s after hearing a tone a movement might or might not occur and that they should use the first 2 s to develop the co-contraction. Again, they were told to report the direction of the movement and not to guess if they were unsure.

The movement velocity used throughout these experiments was 0.2 deg s−1 which had been shown in previous experiments to provide reliable measurements of threshold (Wise et al. 1996). The method used to measure threshold was that of the staircase of limits (Cornsweet, 1962). A test movement was applied which was known to be large enough to be readily detected by the subject. Then its amplitude was reduced until the subject could no longer detect it. As soon as that point had been reached, amplitude was increased again until the movement was detected. This procedure was repeated, presenting movements at random in either the direction of flexion or extension, until a number of reversal points had been obtained for each direction. Threshold was calculated as the mean of six to eight reversals.

RESULTS

For each subject, measurements were first made of thresholds after hold-long and hold-short conditioning, as reported previously (Wise et al. 1996). Then measurements were repeated after a conditioning co-contraction at the test length (hold-test). During these measurements the subject's arm remained completely relaxed. Thresholds were then re-measured, with both elbow flexors and extensors actively contracting. Threshold values for the passive arm were compiled for a total of eleven subjects while in seven of them thresholds were also measured during a co-contraction.

An example of thresholds obtained for one subject is shown in Fig. 2. As reported previously, threshold in the direction of extension after hold-short conditioning was lower (0.12 deg) than threshold into flexion (0.39 deg). Similarly, after hold-long conditioning threshold in the direction of flexion (0.22 deg) was lower than in the direction of extension (0.32 deg). For movements imposed on the relaxed arm after a co-contraction with the forearm held at 90 deg (hold-test), thresholds in the direction of extension were approximately the same as after hold-short conditioning (0.10 deg). However, for movements in the direction of flexion, thresholds remained low (0.13 deg). Indeed, for this subject they were lower than for movements in the same direction after hold-long conditioning (0.22 deg). Finally, thresholds measured with elbow flexors and extensors co-contracting gave values which were substantially higher for movements both in the direction of flexion (0.42 deg) and extension (0.52 deg). In other words, subjects with relaxed elbow muscles were better able to detect imposed movements than when their muscles were actively contracting.

Figure 2. Movement thresholds for one subject.

Thresholds for imposed movements at a speed of 0.2 deg s−1 in the direction of extension or flexion under three different conditions. A conditioning co-contraction was carried out with the arm flexed by 30 deg from its 90 deg mid-position (hold-short, •) or extended by 30 deg (hold-long, ^) and the passive arm then brought back to the mid-position and the test movement imposed. In a second experiment, movements were imposed on the relaxed arm after a co-contraction at the mid-position (hold-test, □). In the third, elbow flexors and extensors were actively contracting while the test movement was applied (active, ▪).

This trend was confirmed for all subjects. However, because of large differences between thresholds for individual subjects it was necessary to normalize the data. Values were expressed as a fraction of the mean threshold from flexion and extension movements of the passive arm after a conditioning co-contraction at the test length. A value of 1 indicates a threshold equivalent to this average (Fig. 3). A repeated measures ANOVA (S= 11) indicated a significant interaction between hold-long, hold-short and hold-test. A Student's t test showed that thresholds in the direction of extension following hold-short or hold-test conditioning were significantly lower than after hold-long conditioning (P < 0.01). For movements into flexion, thresholds after hold-long or hold-test conditioning were significantly lower than after hold-short conditioning (P < 0.01).

Figure 3. Normalized thresholds for eleven subjects.

Thresholds for movements imposed at the forearm following hold-short conditioning (•), hold-long conditioning (^) and hold-test (□). For seven of the subjects thresholds were also measured while they were carrying out a co-contraction of elbow muscles in the test position (▪). All values are shown as means ±s.e.m.

It was found that with the muscles contracting actively, thresholds were always high, giving values within the range corresponding to that obtained with movements into extension after hold-long conditioning and into flexion after hold-short conditioning. Analysis of the EMG data indicated that, on average, EMG levels during a co-contraction were 21 % of the MVC value in elbow flexors and 13.5 % of MVC in extensors, implying a contraction biased in the direction of flexion. This was confirmed in tension recordings which showed at the onset of the co-contraction an initial overshoot in the direction of flexion. Tension levels would then gradually fall as the co-contraction became more even. When the test movement occurred tension was, nevertheless, still slightly biased in the direction of flexion, leading to a small displacement in the direction of flexion (1.5 ± 2.0 % (means ±s.e.m.) of detection threshold). In addition, during the co-contraction, arm position was not quite steady, the peak-to-peak fluctuation in amplitude at movement onset being 1.4 ± 1.0 % of detection threshold. We do not believe that fluctuations of this magnitude are likely to significantly affect detection threshold, given the large effects produced by the muscle contraction itself.

A repeated measures ANOVA (S= 7) revealed that detection thresholds during an active co-contraction were significantly higher than after hold-test conditioning (P < 0.01). Further analysis using t tests showed that thresholds during active co-contractions were no different from those obtained for measurements in the direction of extension following hold-long conditioning and in the direction of flexion following hold-short conditioning. However, as expected, thresholds were significantly higher than for movements into extension after hold-short conditioning and for movements into flexion after hold-long conditioning (P < 0.01).

We chose a co-contraction at the test length to determine active thresholds because we wanted to make a direct comparison with measurements made on the relaxed forearm after hold-test conditioning. One explanation we considered for the observed higher threshold was that the task asked of subjects was simply too difficult for them. Their concern for maintaining the required level of co-contraction could have interfered with their concentration on the task of detecting any imposed movements. We controlled for this possibility in three subjects by asking them to produce the typical co-contraction with one forearm while movements were imposed on the other, appropriately conditioned, passive forearm. Measured thresholds for the passive forearm for movements into extension and flexion when the subjects were carrying out a co-contraction with the other arm were, on average, 0.25 ± 0.05 deg. This compares with a threshold of 0.23 ± 0.03 deg following hold-test conditions without the contralateral contraction. These differences were not significant (related sample t test).

Throughout each experiment the number of errors was scored. An error was recorded if the subject reported the direction of an imposed movement as the opposite to that actually being applied. The average number of errors did not change with any of the four conditioning procedures. It was 6.6 % for movements in the direction of flexion and 5.5 % in the direction of extension.

DISCUSSION

The findings reported here have confirmed our earlier observations on the effects of muscle conditioning on detection of movements about the elbow joint. (Wise et al. 1996). Movement detection thresholds were always lowest in the direction which stretched forearm muscles that had been contracted while they were short. We interpret these findings in terms of muscle thixotropy.

In a resting muscle fibre there are present a significant number of attached cross-bridges between actin and myosin (Hill, 1968). The length at which the cross-bridges form depends on the length of the fibre immediately after the last contraction. Once stable cross-bridges have formed, shortening the fibre leads to it falling slack because of the stiffening effect of the bridges which do not normally detach in response to the compressive forces accompanying fibre shortening. Applying all of this to the intrafusal fibres of spindles, it is likely that the conditioning contraction used in this study involves activity in both α- and γ-motoneurones (Vallbo, 1970). Following the contraction, stable cross-bridges form in intrafusal fibres at the conditioning muscle length. Any shortening movement of a muscle after a contraction will lead the intrafusal fibres of its spindles to fall slack, thereby leaving the spindles insensitive to stretch. If the muscle is stretched after the contraction its spindles will remain taut and stretch sensitive. For that reason, hold-short conditioning leaves elbow flexors sensitive to movements in the direction of extension and hold-long conditioning leaves extensors sensitive to flexion movements. This is the basis of the interpretation of our findings. It is difficult to find an alternative explanation, given the strict dependence of the changes in detection thresholds on the form of conditioning.

Here we report two additional observations. The first is the measurement of thresholds, not after conditioning contractions with the arm held either flexed or extended, but after a co-contraction at the test length. Theory predicts that with this form of conditioning there should be no slack present in spindles of either flexors or extensors. Therefore, subsequent movements imposed on the relaxed arm should be detected equally readily in both directions. That, indeed, was what was observed. We had also considered the additional factor of the central nervous system accessing not just the increase in spindle discharge from the muscle undergoing stretch, but the decrease from the shortening antagonist. Since there was no slack present in spindles of either muscle, resting discharge levels would be expected to be high in both, so that an imposed movement in a selected direction would be expected to lead to a significant rise in spindle output from the stretched muscle and a significant fall from the shortening muscle. Does the additional cue of a fall in spindle output further lower movement detection thresholds, below the value obtained when the only available signal is coming from the stretched muscle? Our data suggest that a co-contraction at the test length does not lead to a significant lowering of thresholds below the low values obtained after hold-long and hold-short conditioning. The co-contraction did lead to a slightly lower threshold for movements into flexion than after hold-long conditioning, but this was not significant.

Our interpretation was based on the assumption that stretch sensitivity after hold-short conditioning was the same as after hold-test conditioning. After hold-short conditioning the muscles were stretched back to the test length. Hold-test is a conditioning contraction without any subsequent stretch. Certainly there should be no slack present in spindles with either form of conditioning. But the exact mechanical state might not be identical. In another project concerned with the responses of single identified spindle afferents of the soleus muscle of the anaesthetized cat, we took the opportunity to examine the responses of spindles to stretches of amplitudes and rates comparable to those used in the human experiments. Stretch responses following hold-short conditioning, although not quite the same as after hold-test conditioning, were of near-identical amplitude within the range corresponding to the human detection thresholds.

We provisionally conclude that thresholds for the detection of small movements are determined predominantly by signals coming from the muscles undergoing stretch. Any change in signal from the muscles being shortened by the movement does not play a major role.

The third question we asked was how did the thresholds measured in the passive arm compare with thresholds measured while the subject carried out a co-contraction. Here we found thresholds for imposed movements at the elbow joint, with actively contracting elbow flexor and extensor muscles, to be significantly higher than with the relaxed arm. In an earlier report, Taylor & McCloskey (1992) had shown that during active flexion of the forearm thresholds were significantly lower than when muscles about the joint were relaxed.

These authors considered three possible explanations for their findings. The first was a change in biomechanics of muscle and tendon as a result of the higher force levels during the contraction. Because the measurements had been made in the mid-range of joint position, biomechanical factors were considered unlikely to play a large part. Secondly, the sensitivity of spindles may have been increased by the contraction. Again, it was thought unlikely that an increased responsiveness of spindles could account for their findings. However, it was considered that the aggregate of the firing of the muscle's spindles would be greater and this could account for the lower threshold. The question was left open of any contributions from central facilitation of the transmission of afferent information by the contraction.

In the interpretation of our results it is important to remember that movements were imposed on the forearm while subjects were carrying out a co-contraction, not an active flexion. First, we propose that under the conditions of our experiments, elbow movement thresholds were lowest when the muscles were relaxed, provided the muscle being stretched by the movement had been conditioned appropriately beforehand. It may be that thresholds reported by Hall & McCloskey (1983) were higher because, amongst other factors, muscles had not been systematically conditioned beforehand. If any slack was present in spindles, thresholds would be high. Measurement during an active flexion would remove slack and would therefore lower threshold.

In our experiments, when the contraction history of the muscle had been controlled for, thresholds during an active co-contraction were systematically higher than in the passive forearm. In the search for an explanation of our results, one suggestion came from the subjects themselves. They reported that during a co-contraction there seemed to be more ‘noise in the system’ which made it more difficult for them to detect the direction of the movement. Certainly, spindle discharge rates in actively contracting muscles are likely to be significantly higher and more irregular than in the passive muscle as a result, most probably, of static fusimotor activity (Vallbo, 1974). It has been reported that for contractions of 5–10 % of maximum, 60–70 % of spindle endings showed fusimotor activation (Burke, Hagbarth & Skuse, 1978). This would also be expected to lower spindle stretch sensitivity (Hulliger, Matthews & Noth, 1977). Perhaps the postulated subtraction process which extracts the kinaesthetic signal during on-going fusimotor activity is not very precise. In addition, since it was a co-contraction, large volumes of activity would be coming from both agonists and antagonists. Perhaps the activity coming from the antagonists is able to interfere with central extraction of the relevant signal from the stretched agonist. This problem would not, of course, be present during an active flexion (Taylor & McCloskey, 1992).

We conclude that movement detection thresholds at the elbow joint are lowest when all muscles acting at the joint are relaxed, provided that the muscles being stretched by the movement have been appropriately conditioned. An active co-contraction leads to a rise in threshold, we propose, because of a fall in spindle stretch sensitivity and a noisier length signal as a result of the on-going fusimotor activity.

References

- Burke D, Hagbarth K-E, Skuse NF. Recruitment order of human muscle spindle endings in isometric voluntary contractions. Journal of Physiology. 1978;285:101–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornsweet TN. The staircase method in psychophysics. American Journal of Psychology. 1962;75:485–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhodes JC, Roll JP, Tardy-Gervet MF. Perceptual and motor effects of agonist-antagonist muscle vibration in man. Experimental Brain Research. 1986;61:395–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00239528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LA, McCloskey DI. Detection of movements imposed on finger, elbow and shoulder joints. Journal of Physiology. 1983;335:519–533. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DK. Tension due to interaction between the sliding filaments in resting striated muscle. The effect of stimulation. Journal of Physiology. 1968;199:637–684. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulliger M, Matthews PBC, Noth J. Effects of combining static and dynamic fusimotor stimulation on the response of the muscle spindle primary ending to sinusoidal stretching. Journal of Physiology. 1977;267:839–856. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DI. Kinaesthetic sensibility. Physiological Reviews. 1978;58:763–820. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1978.58.4.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DI, Gandevia S, Potter EK, Colebatch JG. Muscle sense and effort: motor commands and judgements about muscle contractions. In: Desmedt JE, editor. Motor Control Mechanisms in Health and Disease. New York: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Morgan DL, Gregory JE. Thixotropy in skeletal muscle and in muscle spindles: a review. Progress in Neurobiology. 1993;41:705–721. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90032-n. 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90032-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Wise AK, Gregory JE. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Brain and Movement. Russia: St Petersburg-Moscow; 1997. The effects of muscle conditioning on movement detection thresholds at the human elbow joint; pp. 48–49. 6–10 July. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, McCloskey DI. Detection of slow movements imposed at the elbow during active flexion in man. Journal of Physiology. 1992;457:503–513. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB. Discharge patterns in human muscle spindle afferents during isometric voluntary contractions. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1970;80:552–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1970.tb04823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB. Human muscle spindle discharge during isometric voluntary contractions. Amplitude relations between spindle frequency and torque. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1974;90:319–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1974.tb05594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise AK, Gregory JE, Proske U. The effects of muscle conditioning on movement detection thresholds at the human forearm. Brain Research. 1996;735:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00603-8. 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]