Abstract

Intracellular pH (pHi) and intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) were measured during changes to superfusate PCO2 and/or [NaHCO3]. Changes to superfusate PCO2 produced sustained changes to pHi and [Ca2+]i, while changes to [NaHCO3] altered only extracellular pH (pHo).

Carbachol or caffeine induced a transient rise of [Ca2+]i due to Ca2+ release from an intracellular store. This Ca2+ transient was reduced by extracellular acidosis, but increased by intracellular acidosis. Alkalosis in either compartment produced opposite effects to acidosis. Changes to the Ca2+ transient mirrored those to phasic tension previously reported in this preparation.

A raised superfusate [K+] also induced a Ca2+ transient, due to transmembrane influx of Ca2+. This transient was depressed by extracellular acidosis, but unaffected by changes to pHi. The L-type Ca2+ current was similarly affected by changes to pHo, but not by alteration of pHi.

The results suggest that extracellular acidosis depresses the Ca2+ transient by reducing transmembrane influx through the L-type Ca2+ channel. The increase in the carbachol- and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients by intracellular acidosis is due to enhancement of Ca2+ uptake into intracellular stores as a result of a raised resting [Ca2+]i.

Detrusor smooth muscle can experience large variations of extracellular pH (pHo) and intracellular pH (pHi) under various conditions. For example, CO2 can diffuse readily across the urothelium and urinary PCO2 can rise to values as high as 20 kPa (Pitts, Ayers & Scheiss, 1948), the urothelium can be damaged and rendered permeable to the acid urine (Eldrup, Therup, Nielsen, Hald & Hainau, 1983), and H+ can be accumulated in the bladder wall during ischaemia caused by conditions such as systemic hypotension or during both bladder filling and spontaneous contractions, particularly in the obstructed bladder (Bellringer, Ward & Fry, 1994; Azadzoi, Pontari, Vlachiotis & Siroky, 1996; Batista, Wagner, Azadzoi, Krane & Siroky, 1996).

Changes to the extracellular and intracellular pH have profound and unusual effects on the contractile function of detrusor smooth muscle. Extracellular acidosis, from a normal pH value of about 7.4, depresses electrically elicited phasic contractions; however, intracellular acidosis, from a normal pH value of about 7.1, increases the magnitude of such contractions (Liston, Palfrey, Raimbach & Fry, 1991). Alkalosis in these two compartments exerts opposite effects to those of acidosis. Such effects have been observed in both human detrusor and tissue from several animal preparations, including the guinea-pig. In the case of extracellular pH changes, altered contractility is mediated by depression of the L-type Ca2+ channel (Fry, Gallegos & Montgomery, 1994a). However, the mechanisms whereby intracellular acid-base changes exert their effects on the force of contraction are unknown and form the subject of this paper.

In striated muscle, several steps in excitation-contraction coupling are altered by changes to intracellular pH; in particular, changes to the myofilament sensitivity for Ca2+ contribute significantly to pH-dependent inotropic effects (Orchard & Kentish, 1990). However, we have recently shown that changes to myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in detrusor muscle cannot explain fully the inotropic effects of changes to intracellular pH (Wu, Kentish & Fry, 1995), which suggests that modulation of the availability of intracellular Ca2+ could be a factor. Phasic detrusor contractions are initiated predominantly by cholinergic motor nerves embedded in the muscle mass, mediated by a transient rise in intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i), but independent of changes to the membrane potential (Wu & Fry, 1997). However, in many small animals and in human detrusor from some abnormally functioning bladders there is an additional, probably purinergic component which raises [Ca2+]i via membrane depolarization and activation of the L-type Ca2+ current, ICa (Sibley, 1984; Inoue & Brading, 1991; Wu, Wallis & Fry, 1995; Bayliss, Wu & Fry, 1997). The present study has investigated whether changes to extracellular and intracellular pH could modulate such Ca2+ transients and where the sites of action of H+ are located in the cell.

The results show that intracellular acidosis increases the magnitude of the intracellular Ca2+ transient evoked by the cholinergic agonist carbachol, and that such an action is most probably mediated via an enhancement of the Ca2+ sequestration rate by the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Intracellular pH changes had no effect on the rate of Ca2+ movement across the surface membrane.

METHODS

Preparation

Single detrusor smooth muscle cells were isolated from guinea-pig urinary bladders. Guinea-pigs (500–900 g) were killed by cervical dislocation, and small detrusor strips were cut from the dome of the bladder and placed in Ca2+-free solution containing (mm): NaCl, 105.4; NaHCO3, 20.0; KCl, 3.6; MgCl2.6H2O, 0.9; NaH2PO4.2H2O, 0.4; glucose, 5.5; sodium pyruvate, 4.5; and Hepes, 4.9, pH 7.1. Isolated detrusor myocytes were prepared with a collagenase-based mixture as described previously (Montgomery & Fry, 1991).

Solutions

Detrusor myocytes were superfused at 37°C with Tyrode solution gassed with 95 % O2- 5 % CO2 (pH 7.38 ± 0.01, n= 56) and of the following composition (mm): NaCl, 118; NaHCO3, 24.0; KCl, 4.0; MgCl2.6H2O, 1.0; NaH2PO4.2H2O, 0.4; CaCl2, 1.8; glucose, 6.1; sodium pyruvate, 5.0. Ca2+-free superfusates contained no added CaCl2 and 0.1 mm EGTA. To change separately intracellular pH (pHi) and extracellular pH (pHo), the Tyrode solution was modified by altering [NaHCO3] and the percentage of CO2 in the gas mixture. pHo was altered by varying [NaHCO3] between 9.6 and 48 mm at constant PCO2 (5 % CO2, 4.6 kPa). pHi was varied by changing, in proportion, [NaHCO3] and PCO2; NaHCO3 was varied between 9.6 and 48 mm and CO2 was varied between 2 % (1.8 kPa) and 10 % (9.2 kPa). Values of pHo and pHi in these solutions are shown in Table 1. Because Ca2+ and HCO3− form ion pairs in solution, changes to [NaHCO3] necessitated changes to [CaCl2] in these superfusates to maintain constant the ionized calcium concentration (Fry & Poole-Wilson, 1981). Solutions containing 9.6 and 48 mm NaHCO3 contained 1.55 and 2.34 mm CaCl2, respectively, to maintain the same ionized calcium concentration as was present in Tyrode solution (24 mm NaHCO3, 1.8 mm CaCl2), and were checked with a Ca2+-selective electrode.

Table 1.

Values of pHo and pHi in guinea-pig detrusor myocytes by variation of superfusate [NaHCO3] (between 9.6 and 48 mm) and PCO2 (between 1.8 and 9.2 kPa)

| 24 mm, 4.6 kPa | 48 mm, 9.2 kPa | 9.6 mm, 1.8 kPa | 48 mm, 4.6 kPa | 9.6 mm, 4.6 kPa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pHo | 7.38 ± 0.01 (56) | 7.39 ± 0.01 (17) | 7.39 ± 0.01 (19) | 7.70 ± 0.02 (13)* | 7.02 ± 0.01 (9)* |

| pHi | 7.10 ± 0.03 (14) | 6.98 ± 0.03 (7)* | 7.24 ± 0.07 (7)* | 7.06 ± 0.04 (6) | See text |

The particular values of the variables are given at the head of each column.

pHo or pHi significantly different (P < 0.01) from the value in normal Tyrode solution (24 mm HCO3−, 4.6 kPa CO2). Numbers of myocytes (pHi) or number of measurements (pHo) are shown in parentheses.

Measurement of pHi and [Ca2+]i

pHi and [Ca2+]i were measured by epifluorescence microscopy using BCECF (2′,7′-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6′)-carboxyfluorescein) and fura-2 (Calbiochem). Cells were loaded with acetoxymethyl (AM) esters of the indicators (4–5 μm, 30 min at room temperature, 20–23°C) then superfused at 37°C with Tyrode solution in a chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope. In voltage-clamp experiments, acid forms of the indicators (100 μm) were dialysed into cells via patch pipettes. Cells were illuminated alternately at 510/430 nm or 340/380 nm and emitted light was collected between 530 and 580 nm for BCECF or between 400 and 510 nm for fura-2. BCECF signals were calibrated to pHi values with 10 μm nigericin (Sigma) in a high-K+ medium between pH 4.0 and 9.0 (Eisner, Nichols, O'Neill, Smith & Valdeolmillos, 1989). Similarly fura-2 signals were converted to [Ca2+]i values by the equation (Grynkiewicz, Poenie & Tsien, 1985):

R is the fluorescence ratio at 340/380 nm excitation, ‘min’ and ‘max’ subscripts refer to values at zero and saturating [Ca2+], respectively; b is the fluorescence ratio at zero and saturating [Ca2+] at 380 nm alone; Kd (224 nm) is the dissociation constant for Ca2+ with fura-2. It is assumed that Kd is independent of pHi over the range of measured values (see Discussion).

The peak values of intracellular Ca2+ transients were measured when cells were stimulated by brief application of solutions containing 10 μm carbachol, 44 mm KCl or 10 mm caffeine. Preliminary experiments showed that exposures to carbachol and caffeine for 20–30 s and to KCl for 40 s were sufficient to elicit a maximal intracellular Ca2+ transient.

Electrophysiolgical recordings

Ca2+ currents (ICa) through L-type Ca2+ channels were measured using patch-type electrodes in whole-cell configuration (Axopatch-1D; Axon Instruments). An A/D converter (Digidata 1200; Axon Instruments) applied voltage steps and recorded membrane currents with a sampling frequency of 4 kHz and cut-off frequency of 2 kHz; voltage-clamp protocols were supported by pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). [Ca2+]i was measured simultaneously with the indicator fura-2. Patch electrodes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing (mm): CsCl, 20; aspartic acid, 110; MgCl2, 5.45; Na2ATP, 5.0; and Hepes, 5.0, pH 7.1 adjusted with CsOH. Preliminary experiments showed that 100 μm K5-fura-2 was required to achieve a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio and 50 μm EGTA to prevent run-down of the Ca2+ current, while not attenuating significantly the Ca2+ transient.

Statistics

Numerical data are quoted as means ±s.e.m., since experimental observations were generally repeated on the same cell. Data sets from single observations per cell are quoted as means ±s.d., and are identified specifically in the text. Student's two-tailed paired or unpaired t tests were used to test for significance between sets of data and the null hypothesis was rejected when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

pHi and resting [Ca2+]i of guinea-pig detrusor myocytes

pHi in myocytes superfused with normal Tyrode solution was 7.10 ± 0.03 (n= 14; Table 1, column 1). The table shows that pHi could be altered independently of pHo, when superfusate [NaHCO3] and PCO2 were varied in proportion, and also that changes to [NaHCO3] alone had no effect on pHi. Note that a previous study has shown that pHi was unaffected when superfusate [NaHCO3] was reduced from 24 to 6 mm at constant PCO2 (Fry, Gallegos & Montgomery, 1994b). The changes to pHi during alteration of superfusate PCO2 were rapid and sustained for the period of the intervention and recovered completely on return to control superfusate.

Resting [Ca2+]i in undialysed myocytes in Tyrode solution was 77 ± 41 nm (n= 254), which is consistent with a threshold value of about 100 nm for activation of detrusor myofibrils (Wu et al. 1995). The values of the resting [Ca2+]i were not significantly different from a normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, d= 0.078, P > 0.05). A decrease in pHi by, on average, 0.12 units (Table 1) raised the mean value of [Ca2+]i by 12 ± 1 nm (P < 0.01, n= 50) and an increase in pHi by, on average, 0.14 units decreased [Ca2+]i by 23 ± 6 nm (P < 0.01, n= 33). Extracellular pH changes had no significant effects on resting [Ca2+]i values.

Carbachol-induced intracellular Ca2+ transients - the effects of changes to pHo and pHi

Acetylcholine, and its analogue carbachol induce contraction in detrusor smooth muscle (Sibley, 1984). Figure 1A shows that in single detrusor myocytes repeated brief (20–40 s) applications of carbachol (10 μm) induced transient increases of [Ca2+]i - Ca2+ transients. The transients reached a maximum value within 2–3 s before relaxing, despite the continuous presence of carbachol. In the majority of cells (75 %, n= 150), the relaxation phase showed an undershoot before return to the baseline value. The magnitude of the Ca2+ transient was dependent on the carbachol concentration, with half-maximal activation at 1.2 ± 0.6 μm (mean ±s.d., n= 5) and maximum activation at 10 μm.

Figure 1. Intracellular Ca2+ transients induced by carbachol.

Properties of the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient. A, repeated brief applications (filled bars) of 10 μm carbachol (carb) gave consistent Ca2+ transients. B, prior application of 1 μm atropine (Atr) blocked the Ca2+ transient. C, prior application of 10 mm caffeine (caff) blocked the Ca2+ transient. D, prior application of 5 μm nicardipine (nicard) had no effect on the Ca2+ transient. E, a Ca2+ transient during superfusion with a zero-Ca2+ solution.

Several other features of the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients are also illustrated in Fig. 1. Panel B shows that the Ca2+ transient was abolished by prior application of the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine (1 μm). Panels C and D show that the Ca2+ transient was also abolished by prior treatment with caffeine (10 mm) but that 30 or 60 s pre-treatment with the L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist nicardipine (5 μm) had no effect. Finally, panel E shows that such transients could still be evoked in a nominally Ca2+-free superfusate, although the magnitude was reduced - note also a reduction in resting [Ca2+] in the Ca2+-free solution. These observations suggest that the source of Ca2+ for the Ca2+ transient is an intracellular store, probably the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Figure 2 shows the effect of altering pHo and pHi on the magnitude of the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient. Panels A and B show the effect of acidosis. Panel A shows that intracellular acidosis at constant pHo, achieved by increasing the superfusate PCO2 and [NaHCO3], increased the magnitude of the Ca2+ transient to 121 ± 4 % of control (mean ±s.e.m., P < 0.01, n= 50). However, extracellular acidosis (B) had the converse effect, namely it attenuated the Ca2+ transient magnitude to 83 ± 5 % of control (P < 0.01, n= 11).

Figure 2. The effects of changes to pHo and pHi on the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient.

Cells were briefly exposed to 10 μm carbachol and either pHo or pHi was changed by altering the superfusate PCO2 and/or [HCO3−]. A, intracellular acidosis (48 mm HCO3−, 9.2 kPa CO2). B, extracellular acidosis (9.6 mm HCO3−, 4.6 kPa CO2). C, intracellular alkalosis (9.6 mm HCO3−, 1.8 kPa CO2). D, extracellular alkalosis (48 mm HCO3−, 4.6 kPa CO2).

Intracellular and extracellular alkalosis also had opposite effects. An intracellular alkalosis (C) reduced the magnitude of the Ca2+ transient (83 ± 4 % of control, P < 0.01, n= 33), whereas an extracellular acidosis (D) augmented the transient (123 ± 6 % of control, P < 0.01, n= 32).

The relationship between the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient and contraction

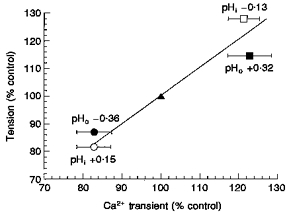

A previous study (Liston et al. 1991) established the relationship between the magnitude of phasic isometric detrusor contractions and the value of either pHo or pHi. It was found that intracellular acidosis increases, while extracellular acidosis decreases, the force of contraction. The dependence of contractile force on the magnitude of the Ca2+ transient, when either pHo or pHi is altered, can be gauged by plotting the two variables against each other. Figure 3 shows the percentage change to Ca2+ transient magnitude as a function of contractile strength when pHo and pHi are altered. The interdependence of the two variables, regardless of whether they were altered by changing pHo or pHi, suggests that pH-induced variations of phasic contractions are significantly influenced by changes to the magnitude of the cholinergic Ca2+ transient.

Figure 3. The relationship between the magnitudes of the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient and phasic tension.

Values of the Ca2+ transient and phasic tension are plotted as a function of those recorded in control Tyrode solution (100 %, ▴). Ca2+ transient values are plotted as means ±s.d.; mean tension values are taken from Liston et al. (1991). Data points were obtained during extracellular alkalosis (▪) and acidosis (•) and during intracellular alkalosis (^) and acidosis (□).

High-K+-induced intracellular Ca2+ transients - the effects of changes to pHo and pHi

In several muscle types, pH-dependent inotropic effects are in part mediated by their actions on transmembrane Ca2+ fluxes, in particular on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. In detrusor a rise in intracellular Ca2+ can be elicited by activation of the L-type Ca2+ channel (Ganitkevich & Isenburg, 1991). We therefore investigated the effect of altered pH on Ca2+ transients evoked by membrane depolarization induced by either raising extracellular [K+] or under voltage clamp.

Figure 4 shows Ca2+ transients elicited by increasing the extracellular [K+] from 4 to 40 mm for 40 s. The KCl-induced Ca2+ transients had longer time courses than the carbachol-evoked transient, were totally abolished by 5 μm nicardipine (n= 5) and were partially inhibited by 10 μm ryanodine (72 ± 14 % of control, mean ±s.d., n= 4) - not shown.

Figure 4. The effects of changes to pHo and pHi on the high-K+-induced Ca2+ transient.

Cells were briefly exposed to Tyrode containing 44 mm KCl and either pHo or pHi was changed by altering the superfusate PCO2 and/or [HCO3−]. A, extracellular acidosis (9.6 mm HCO3−, 4.6 kPa CO2). B, extracellular alkalosis (48 mm HCO3−, 4.6 kPa CO2). C, intracellular acidosis (48 mm HCO3−, 9.2 kPa CO2).

The three panels in Fig. 4 show that changes to extracellular pH affected the magnitude of the KCl-induced Ca2+ transient but that changes to intracellular pH were without effect. Panel A shows that extracellular acidosis decreased the Ca2+ transient magnitude - to 76 ± 5 % of control (P < 0.01, n= 12). Panel B shows that extracellular alkalosis increased the Ca2+ transient - to 127 ± 5 % of control (P < 0.01, n= 10). However, panel C shows that intracellular acidosis had no significant effect on the Ca2+ transient (104 ± 5 % of control, P > 0.05, n= 16). Similarly, but not illustrated, intracellular alkalosis had no significant effect (103 ± 3 % of control, P > 0.05, n= 22).

Ca2+ current (ICa) and depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients - the effects of changes to pHo and pHi

The above data show that changes to pHo exert effects on high-K+-induced Ca2+ transients whereas changes to pHi do not. To obtain more direct evidence that these effects are mediated via the L-type Ca2+ channel, Ca2+ transients and the L-type Ca2+ current, ICa, were measured simultaneously during changes to pHo and pHi.

Ca2+ transients and ICa were evoked by steps to between -40 and +60 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV. The examples given in Fig. 5A show that the decay of ICa is accelerated in the final stages when the Ca2+ transient begins, demonstrating the Ca2+ dependence of ICa. The voltage dependencies of both signals were bell shaped and a mirror of each other, with maxima at +10 mV (see Fig. 6 below). At potentials between +60 and +80 mV ICa reversed while the Ca2+ transient magnitude approached, but did not reach, a zero value. The reversal of ICa and a maintained but small Ca2+ transient may be explained by outward permeation of other ions such as Cs+ and Na+ which counterbalance a small residual Ca2+ influx (Hess & Tsien, 1984). Both ICa and the Ca2+ transient were abolished by verapamil (10 μm). These observations demonstrate a causal relationship between ICa and the Ca2+ transient and also minimize the possibility of an involvement by Na+-Ca2+ exchange to the Ca2+ transient. The Ca2+ transient was also attenuated by ryanodine (20–50 μm), suggesting the involvement of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in generating the final Ca2+ transient. To examine the effects of pH changes on these phenomena, a voltage step of 1 s duration was used, which gave the maximum increase in the intracellular [Ca2+], and a 50 s pulse interval to allow complete recovery.

Figure 5. The effect of changes to pHo to simultaneously recorded ICa and Ca2+ transient.

A, ICa (upper traces) and Ca2+ transients (lower traces) during superfusion with normal Tyrode solution (left and right traces, 24 mm HCO3−) and during extracellular acidosis (middle traces, 9.6 mm HCO3−). Traces evoked by a 1 s voltage-clamp step from -60 to +10 mV. B, rising phases of Ca2+ transients during control (24 mm HCO3−), extracellular acidosis (9.6 mm HCO3−) and extracellular alkalosis (48 mm HCO3−).

Figure 6. Voltage dependence of ICa and the Ca2+ transient.

A, voltage dependence of ICa and the Ca2+ transient in normal Tyrode solution (□) and during extracellular acidosis (•) or extracellular alkalosis (▪). B, control experiment showing changes to intracellular pH during superfusion with solutions of raised (left) and lowered (right) PCO2, at constant pHo in a patch pipette dialysed cell.

Figure 5A shows three pairs of traces, each consisting of a current trace (upper panel) and a Ca2+ transient (lower panel). The first and third pair of traces were obtained under control conditions, the centre pair during an extracellular acidosis. The magnitude of both ICa and the Ca2+ transient were reversibly attenuated in the low-pHo solution. Combined data showed that an extracellular acidosis from pH 7.38 to pH 7.02 reduced ICa and the Ca2+ transient to 87 ± 2 and 83 ± 4 %, respectively, of control (P < 0.01, n= 15). Extracellular alkalosis to pH 7.70 increased ICa and the Ca2+ transient to 116 ± 3 and 132 ± 3 %, respectively, of control (P < 0.01, n= 12).

Figure 5B shows that the rate of rise in the Ca2+ transient was similarly affected; acidosis decreased the rate from a control of 4.3 ± 0.5 to 3.9 ± 0.45 μmol l−1 s−1 (P < 0.01, n= 15) and alkalosis increased the rate from a control of 3.9 ± 0.8 to 5.0 ± 1.0 μmol l−1 s−1 (P < 0.01, n= 12). Because the rate of rise in the Ca2+ transient corresponds to the instantaneous amplitude of ICa (Becker, Singer, Walsh & Fay, 1989), this suggests that extracellular H+ exerts a primary effect on the L-type Ca2+ channels.

Changes to intracellular pH, however, had no significant effect on either ICa or the Ca2+ transient. The magnitudes of the two variables were 107 ± 5 and 102 ± 5 %, respectively, of control when pHi was reduced by 0.13 units (P > 0.05, n= 17); they were 101 ± 4 and 99 ± 4 %, respectively, of control when pHi was increased by 0.15 units (P > 0.05, n= 16).

These effects of pH were also examined over the entire voltage range from -50 to +30 mV. Figure 6 shows the voltage dependence of both ICa and the Ca2+ transient and demonstrates that, at all voltages, extracellular acidosis decreased and extracellular alkalosis augmented both variables. No effects of altering pHi were found at any voltage in this range.

The lack of effect of interventions designed to alter pHi could be due to the fact that no such change actually occurred in these cells dialysed with a patch pipette. To exclude this possibility, pHi was measured in patch-dialsysed cells exposed to the superfusates with altered PCO2 and [NaHCO3]. pHi was measured by including the free-acid form of BCECF (30 μm) in the patch pipette. Figure 6B shows that, when cells were exposed to solutions in which proportional changes to PCO2 and [NaHCO3] were made, pHi changed in the expected direction and by a similar magnitude to that measured in undialysed cells (see Table 1). Therefore the lack of effect of changes to pHi on ICa or the Ca2+ transient cannot be attributed to an inability to alter pHi under these experimental conditions.

Caffeine-induced intracellular Ca2+ transients - the effects of changes to pHo and pHi

The effects of intracellular pH changes on the magnitude of the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient cannot be explained by changes to transmembrane Ca2+ fluxes, at least through the L-type Ca2+ channel. This suggests that the actions of intracellular H+ are more likely to be on an intracellular site of Ca2+ regulation. One possibility is that the ability of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to store and/or release Ca2+ is altered by changes to pHi. To examine this, the influence of changes to pHi on the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient was measured.

Figure 7 shows Ca2+ transients elicited by brief exposure to caffeine (10 mm). These transients had a slightly longer time course than the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients, but like the latter, often exhibited a pronounced transient undershoot following relaxation. Panel A shows that these Ca2+ transients could be attenuated by prior application of 10 μm carbachol. This observation, together with the obverse experiment, whereby the carbachol-dependent Ca2+ transient is diminished by pre-treatment with caffeine (Fig. 1C), indicates that there is an overlap of the carbachol-sensitive and caffeine-sensitive Ca2+ stores in the muscle cell.

Figure 7. The effects of changes to pHo and pHi on the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient.

A, caffeine- and carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients. Brief application of carbachol (10 μm) a short time before application of caffeine (10 mm) reduced the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient. B, effect of intracellular acidosis (left trace, 48 mm HCO3−, 9.2 kPa CO2) and intracellular alkalosis (right trace, 9.6 mm HCO3−, 1.8 kPa CO2) on the magnitude of the Ca2+ transient.

Figure 7B shows that intracellular acidosis increased the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient, the mean value being 121 ± 5 % of control (P < 0.01, n= 41). Conversely, Fig. 7B also shows that an intracellular alkalosis attenuated the Ca2+ transient, the mean value being 77 ± 5 % of control (P < 0.01, n= 24). The magnitudes of these changes were quantitatively similar to the pHi-mediated effects on the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient. This suggests that the SR is the site at which intracellular H+ augments the Ca2+ transient and hence the force of contraction.

Possible mechanisms for the actions of intracellular H+ on SR Ca2+ regulation

Changes to the magnitude of the carbachol-induced or caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient by intracellular H+ could be mediated either by effects on the SR Ca2+ release channels or by influencing the accumulation of Ca2+ via the SR Ca2+ pump. Measurement of the rate of rise in the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient showed that this variable was unaffected at different values of pHi. This suggests that an effect on the Ca2+ release channels is unlikely.

The second possibility was investigated by measuring the magnitude of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient as an estimate of the amount of Ca2+ within the intracellular stores. Intracellular acidosis increased not only the magnitude of the Ca2+ transient but also the resting [Ca2+]i. It was therefore possible that the the raised [Ca2+]i was responsible for greater Ca2+ accumulation and hence a larger transient. To test this hypothesis the relationship between the caffeine-induced transient and [Ca2+]i was plotted as shown in Fig. 8. The changes are plotted as percentage variation from the control situation in normal Tyrode solution (^, during intracellular acidosis; •, during intracellular alkalosis). A significant and positive relationship between the two variables (r= 0.55, where r is the correlation coefficient; P < 0.01, n= 54) supported the hypothesis.

Figure 8. The relationship between resting [Ca2+]i and the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient.

The magnitude of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient is plotted as a function of the resting [Ca2+]i. Values are expressed as a percentage of those obtained in Tyrode solution: ^, with intracellular acidosis; •, with intracellular alkalosis. The straight line was obtained by least-squares regression.

The reason for the raised [Ca2+]i is illustrated in Fig. 9A, which shows an experiment where a cell was exposed to a Ca2+-free superfusate (containing 0.1 mm EGTA) and [Ca2+]i monitored. The resting [Ca2+]i was low in this solution (about 20 nm), but when the pHi was lowered by changing the superfusate a small, reversible increase in [Ca2+]i was still recorded, suggestive of an intracellular source for this phenomenon.

Figure 9. Source of the rise of [Ca2+]i during intracellular acidosis.

A, trace of the resting [Ca2+]i during superfusion with a zero-Ca2+ superfusate. During the time indicated an intracellular acidosis was induced by raising, in proportion, the superfusate PCO2 and [HCO3−]. B, the increase in [Ca2+]i when the superfusate was switched from a zero-Ca2+ to normal (1.8 mm) Ca2+-containing superfusate. The experiment was carried out at control pHo and pHi (24 mm HCO3−, 4.6 kPa CO2) and during intracellular acidosis (48 mm HCO3−, 9.2 kPa CO2). The recovery phases were best fitted to a single exponential process: the time constants are displayed next to the line fits.

Figure 9B shows an experiment to examine if a transmembrane source of Ca2+ might, however, also contribute to the increase in [Ca2+]i in acidosis. The traces show the recovery of [Ca2+]i when a Ca2+-containing superfusate was returned after a period of exposure to a low-Ca2+ solution. The rate of recovery was similar in the superfusate with normal PCO2 and [NaHCO3] (τ= 65 s, where τ is recovery time constant) compared with that (τ= 64 s) in the solution which would generate an intracellular acidosis. This suggests that the rate of transmembrane Ca2+ influx was not altered by intracellular acidosis and therefore was unlikely to account for the raised value of [Ca2+]i recorded when pHi was reduced.

DISCUSSION

Actions of H+ on detrusor smooth muscle

A pHi value of 7.10 in guinea-pig detrusor myocytes (Table 1) is similar to that reported for human and ferret detrusor myocytes (Liston et al. 1991; Fry et al. 1994b). The sustained nature of the pHi change when superfusate PCO2 was altered and the lack of effect upon changes to superfusate [NaHCO3] at constant PCO2 measured in this study is in contrast to observations in some other smooth muscles (Aickin & Brading, 1984; Aalkjær & Cragoe, 1988; Austin & Wray, 1993) and may reflect different pH-regulating mechanisms or surface membrane permeability to H+ between detrusor and these other muscles.

Changes to extracellular or intracellular pH have been shown to have opposite effects on phasic contractions in detrusor muscle evoked either by stimulation of the attendent motor nerves embedded in the tissue or by direct electrical stimulation of the muscle (Liston et al. 1991). In this study, extracellular acidosis was negatively inotropic, a finding similar to that in cardiac and several other smooth muscles (Wray, 1988; Orchard & Kentish, 1990); however, intracellular acidification increased the force of phasic contractions.

These observations suggested that pH changes exerted direct effects on the smooth muscle cell, and a previous study showed that extracellular effects of H+ could be attributed to an action on the L-type Ca2+ channel (Fry et al. 1994a). The intracellular actions of H+ are more equivocal but they could act by altering the myofilament sensitivity to Ca2+, or by influencing the intracellular pathways which link surface membrane activation to myofilament interaction. A previous study which investigated the actions of H+ on detrusor myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Wu et al. 1995) found that an increase in pHi, from a normal value of 7.1, decreased Ca2+ sensitivity and hence could explain in part the negative inotropic effect of intracellular alkalosis. However, a decrease in pHi was without effect so that other actions of H+ were required to explain the augmentation of contraction.

Involvement of membrane transporters

One possible action of intracellular acidosis is to increase the intracellular [Na+] via Na+-H+ exchange or Na+-HCO3− co-transport, which in turn could increase intracellular Ca2+ via Na+-Ca2+ exchange; such a mechanism has been proposed in cardiac muscle as a means whereby intracellular H+ can, under some conditions, increase force production (Bountra & Vaughan-Jones, 1989). However, several lines of evidence indicate that this is unlikely: (i) the increase in force by decreased pHi is unaffected by amiloride or DIDS (4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic acid; Liston et al. 1991), (ii) the importance of Na+-Ca2+ exchange in guinea-pig detrusor is questionable (Ganitkevich & Isenberg, 1991), and (iii) intracellular acidosis did not modulate the rate of recovery of [Ca2+]i on return from a zero-Ca2+ superfusate (Fig. 9).

Carbachol-, high-K+- and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients: actions of intracellular and extracellular H+

Extracellular application of carbachol, caffeine or a high-K+ solution evoked an intracellular Ca2+ transient. However, the source of Ca2+ differed; the high-K+ solution generated a transmembrane flux, since the associated Ca2+ transient was rapidly abolished by zero-Ca2+ superfusates or application of the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nicardipine, whereas carbachol and caffeine probably released Ca2+ from an intracellular store. The morphology of the carbachol- and caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients was different from the high-K+-induced transient, showing an undershoot on recovery (see also Baró, O'Neill & Eisner. 1993). Furthermore, prior application of caffeine or carbachol attenuated the Ca2+ transient evoked by the second agonist, indicating that the Ca2+ source was similar. In addition, they were less affected by zero-Ca2+ superfusates and nicardpine, and the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient, at least, was independent of changes to membrane potential (Wu & Fry, 1997).

Acidosis confined to the extracellular space attenuated all three types of Ca2+ transient (alkalosis increased all transients), but there were differences in their response to intracellular pH changes. The high-K+-induced transient was unaffected by changes to pHi, whereas carbachol- and caffeine-evoked transients were increased by acidosis. It has been shown previously that extracellular H+ reduces current flow through the L-type Ca2+ channel (Fry et al. 1994a) and this would explain the attenuation of the high-K+-induced transient. However, the lack of effect of intracellular H+ on the Ca2+ transient evoked by high-K+ suggested that the L-type channel was insensitive to pH changes in this compartment, and this was corroborated by direct measurement of ICa during variation of pHi. This insensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ channel to pHi changes is in contrast to the situation in other muscles where intracellular acidosis is effective in reducing the magnitude of ICa (Kaibara & Kameyama, 1988).

The attenuation of the carbachol- and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients by extracellular acidosis is less straightforward. The Ca2+ transient evoked by carbachol is not dependent on a change of the membrane potential (Wu & Fry, 1997) so that extracellular H+ must exert a secondary effect. One possibility is that H+ may have reduced the filling of intracellular Ca2+ stores via the surface membrane. The importance of such fluxes in refilling acetylcholine-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ stores has been observed in other smooth muscles (Bourreau, Kwan & Daniel, 1993). Such refilling may involve transmembrane Ca2+ influx, as it can be diminished in detrusor by L-type Ca2+ channel blockers (Wu & Fry, 1997) and thus may be attenuated by extracellular H+.

The augmentation of the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient by intracellular acidosis mirrored in a proportional manner the increase in phasic contractile force under similar conditions. Several observations suggest that the site of action might be at the sarcoplasmic reticulum: in particular, caffeine and carbachol released Ca2+ from the same intracellular site, and Ca2+ transients evoked by both agonists were altered by a similar amount with changes to pHi.

Fura-2 signals and pHi changes

It is possible that the altered magnitude of the Ca2+ transients with changes to pHi might be an artefact due to pH-dependent changes of Ca2+-binding to fura-2, even though the fluorochrome has been considered relatively insensitive to pH changes (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985). The calculated values of [Ca2+] quoted in the Results ignore the influence of pH-dependent Ca2+ binding to fura-2 itself. An in vitro control experiment was carried out whereby the binding constant, Kd, of Ca2+ to fura-2 (pentapotassium salt, 10 μm) was measured between pH 6.8 and pH 7.3. Over this range acidification decreased the pKd (-log10Kd) value from 6.73 to 6.48 - i.e. there was a decrease in Ca2+ binding. The effect of this would be to diminish the magnitude of the intracellular Ca2+ signals with acidosis by a maximum of 15 %, an effect opposite to that which was actually observed. Therefore if any pH-dependent effects of Ca2+ binding to fura-2 were taken into account the result would be to accentuate the observed effects of changes to pHi on the intracellular Ca2+ transients.

Mode of action of pHi changes on intracellular Ca2+ stores

An increase in the carbachol- and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient during intracellular acidosis could arise from (i) an increased uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum during the quiescent phase or (ii) a greater release during activation. The rate of rise in the carbachol transient was independent of pHi, which is not consistent with an augmentation of Ca2+ release by intracellular H+. This is also consistent with other observations which show that, if anything, H+ depresses function of the ryanodine and IP3 receptor (Meissner & Henderson, 1987; Tsukioka, Iino & Endo, 1994) and so is unlikely to enhance Ca2+ release.

It is, however, possible that a decrease in pHi can enhance Ca2+ uptake into the SR. Intracellular acidosis increased the resting [Ca2+]i and the positive relationship between this [Ca2+] and the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient suggested that this rise in [Ca2+]i was indeed responsible for greater accumulation of Ca2+ by the SR. This is supported by the observation that SR Ca2+ uptake is increased as [Ca2+]i is raised, with a half-maximal value of about 0.75 μm in smooth muscle (Stout, 1991).

The source of the raised resting [Ca2+]i during acidosis is unknown but could arise from an intracellular source such as displacement of Ca2+ from soluble proteins or from mitochondria (Fry & Harding, 1989). An extracellular source of this Ca2+ is thought unlikely, as the increase still occurred in a zero-Ca2+ superfusate and variation of pHi did not alter the recovery of resting [Ca2+]i when returning from a zero-Ca2+ to a Ca2+-containing superfusate. A second possibility is that H+ directly augments Ca2+ uptake by the detrusor SR (Xu, Narayanan, Samson & Grover, 1993; Elmoselhi, Blennerhasset, Samson & Grover, 1995), although this is disputed by others (Okabe, Kohno, Kato, Odajima & Ito, 1985).

Diversity of responses in smooth muscle to pH changes

The above experiments, when compared with data from other studies, emphasize the diversity of responses to changes of extracellular and intracellular pH in various smooth muscles. The surface membrane of detrusor smooth muscle is very impermeable to polar acid-base moieties such that when the extracellular [NaHCO3] is altered at constant PCO2, there is little alteration of pHi. This has enabled the separate effects of intracellular and extracellular H+ on contractile force to be distinguished, and their different modes of action explored. This relative impermeability has also been seen in vas deferens (Aickin, 1984) and myometrium (Parratt, Sheader, Taggart & Wray, 1994), as well as in cardiac muscle (Ellis & Thomas, 1976). In contrast some other smooth muscles transmit rapidly and more completely changes of extracellular pH to the intracellular space (Austin & Wray, 1993; Ramsey, Austin & Wray, 1994) so that alterations to the pH of either compartment are more likely to have comparable contractile effects.

In addition, changes to pHi can have variable effects on contractile function. The increase in force by acidosis in detrusor phasic tension is mirrored acutely, for example, in some vascular smooth muscle preparations (Matthews, Graves & Poston, 1992; Apkon & Boron, 1995), although more prolonged exposure depresses force. Acidification could reduce force by, for example, reducing myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, reducing ICa or depressing IP3-dependent SR release. On the other hand, by increasing the resting [Ca2+]i and enhancing SR Ca2+ uptake, force could be increased. In detrusor, the balance seems to favour those factors which tend to increase force. The enhanced contractile response of detrusor smooth muscle to intracellular acidification can be considered as an advantage, as this situation is most likely to occur in normal filling of the bladder when the wall is stretched and blood flow is reduced. The greater contractility will thus facilitate the efficient expulsion of urine.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to The Wellcome Trust for financial support.

References

- Aalkjær C, Cragoe EJ. Intracellular pH regulation in resting and contracting segments of rat mesenteric resistance vessels. Journal of Physiology. 1988;402:391–410. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aickin CC. Regulation of intracellular pH in the smooth muscle of guinea-pig ureter: HCO3− dependence. Journal of Physiology. 1984;479:317–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aickin CC, Brading AF. The role of chloride- bicarbonate exchange in the regulation of intracellular chloride in the guinea-pig vas deferens. Journal of Physiology. 1984;349:587–606. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkon M, Boron WF. Extracellular and intracellular alkalinization and the constriction of rat cerebral arterioles. Journal of Physiology. 1995;484:743–753. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin C, Wray S. Extracellular pH signals affect rat vascular tone by rapid transduction into intracellular pH changes. Journal of Physiology. 1993;466:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azadzoi KM, Pontari M, Vlachiotis J, Siroky MB. Canine blood flow and oxygenation: changes induced by filling, contraction and outlet obstruction. Journal of Urology. 1996;155:1459–1465. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baró I, O'Neill SC, Eisner DA. Changes of intracellular [Ca2+] during refilling of sarcoplasmic reticulum in rat ventricular and vascular smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1993;465:21–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista JE, Wagner JR, Azadzoi KM, Krane RJ, Siroky MB. Direct measurement of blood flow in the human bladder. Journal of Urology. 1996;155:630–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss M, Wu C, Fry CH. Cholinergic and purinergic mechanisms in human detrusor from stable and obstructed bladders. British Journal of Urology. 1997;79(suppl. 4):57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Becker PL, Singer JJ, Walsh JV, Fay FS. Regulation of calcium concentration in voltage-clamped smooth muscle cells. Science. 1989;244:211–214. doi: 10.1126/science.2704996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellringer JF, Ward J, Fry CH. Intramural pH changes in the anaesthetized rabbit bladder during filling. Journal of Physiology. 1994;480.P:82–83P. [Google Scholar]

- Bountra C, Vaughan-Jones RJ. Effect of extracellular and intracellular pH on contraction in isolated, mammalian cardiac muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1989;418:163–187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourreau JP, Kwan CY, Daniel EE. Distinct pathways to refill ACh-sensitive internal stores in canine airway smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:C28–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner DA, Nichols CG, O'Neill SC, Smith GL, Valdeolmillos M. The effect of metabolic inhibition on intracellular calcium and pH in isolated rat ventricular cells. Journal of Physiology. 1989;411:393–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldrup J, Therup J, Nielsen SL, Hald T, Hainau B. Permeability and ultrastructure of human bladder epithelium. British Journal of Urology. 1983;55:488–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1983.tb03354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis DE, Thomas RC. Direct measurement of the intracellular pH of mammalian cardiac muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1976;262:755–771. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmoselhi AB, Blennerhasset M, Samson SE, Grover AK. Properties of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump in coronary artery skinned smooth muscle. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1995;15:149–155. doi: 10.1007/BF01322337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry CH, Gallegos CRR, Montgomery BSI. The actions of extracellular H+ on the electrophysiological properties of isolated human detrusor smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 1994a;480:71–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry CH, Gallegos CRR, Montgomery BSI. Measurement of intracellular pH in isolated human detrusor smooth muscle cells. Journal of Urology. 1994b;152:2155–2158. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32342-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry CH, Harding DP. Homeostasis of calcium ions in calcium-tolerant myocytes. In: Piper HM, Isenberg G, editors. Isolated Adult Cardiomyocytes. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fry CH, Poole-Wilson PA. Effects of acid-base changes on excitation-contraction coupling in guinea-pig and rabbit cardiac ventricular muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1981;313:141–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganitkevich VYa, Isenburg G. Depolarization-mediated intracellular calcium transients in isolated smooth muscle cells of guinea-pig urinary bladder. Journal of Physiology. 1991;435:187–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess P, Tsien RW. Mechanism of ion permeation through ion channels. Nature. 1984;309:453–456. doi: 10.1038/309453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Brading AF. Human, pig and guinea-pig bladder smooth muscle cells generate similar inward currents in response to purinoceptor activation. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;103:1840–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaibara M, Kameyama M. Inhibition of the calcium channel by intracellular protons in single ventricular myocytes of the guinea-pig. Journal of Physiology. 1988;403:621–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston TG, Palfrey ELH, Raimbach SJ, Fry CH. The effects of pH changes on human and ferret detrusor muscle function. Journal of Physiology. 1991;342:1–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JG, Graves JE, Poston L. Relationships between pHi and tension in isolated rat mesenteric resistance arteries. Journal of Vascular Research. 1992;29:330–340. doi: 10.1159/000158948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G, Henderson JS. Rapid calcium release from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles is dependent on Ca2+ and is modulated by Mg2+, adenine nucleotide and calmodulin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:3065–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BSI, Fry CH. The action potential and net membrane currents in isolated human detrusor smooth muscle cells. Journal of Urology. 1991;147:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe E, Kohno H, Kato Y, Odajima C, Ito H. Characterization of the effect of pH on the excitation-contraction coupling system of canine masseter muscle. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1985;37:277–283. doi: 10.1254/jjp.37.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchard CH, Kentish JC. Effects of changes of pH on the contractile function of cardiac muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258:C967–981. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.6.C967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parratt J, Sheader E, Taggart M, Wray S. The relationship between extracellular pH (pHo) and intracellular pH (pHi) in human myometrium. Journal of Physiology. 1994;475.P:54P. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RF, Ayers JL, Scheiss WA. The renal regulation of acid-base balance in man. III. The reabsorption and excretion of bicarbonate. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1948;28:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J, Austin C, Wray S. Differential effects of external pH alteration on intracellular pH in rat coronary and cardiac myocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;428:674–676. doi: 10.1007/BF00374593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley GNA. A comparison of spontaneous and nerve-mediated activity in bladder muscle from man, pig and rabbit. Journal of Physiology. 1984;354:431–443. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout MA. Calcium transport by sarcoplasmic reticulum of vascular smooth muscle: I. MgATP-dependent and MgATP-independent calcium uptake. Journal of Cell Physiology. 1991;149:383–395. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041490305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukioka M, Iino M, Endo M. pH dependence of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release in permeabilized smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig. Journal of Physiology. 1994;475:369–375. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S. Smooth muscle intracellular pH: measurement, regulation and function. American Journal of Physiology. 1988;254:C213–225. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.2.C213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Fry CH. The role of the L-type Ca2+ channel in cholinergic pathways in guinea-pig detrusor smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1997;499.P:7–8P. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Kentish JC, Fry CH. Effect of pH on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in alpha-toxin permeabilized guinea-pig detrusor muscle. Journal of Urology. 1995;154:1921–1924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Wallis WRJ, Fry CH. Purinergic activation induces a transient rise of intracellular Ca2+ in isolated human detrusor myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1995;489.P:136–137P. [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Narayanan N, Samson SE, Grover AK. Effect of pH on stability of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump in rabbit heart. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1993;126:87–91. doi: 10.1007/BF01772211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]