Abstract

Ionotropic glutamate receptor-mediated responses were recorded from rat magnocellular basal forebrain neurones under voltage clamp from a somatically located patch-clamp pipette. Currents were recorded from both acutely dissociated neurones and neurones maintained in culture for up to 6 weeks.

Non-NMDA and NMDA receptor-mediated events could be distinguished pharmacologically using the selective agonists (S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), kainate and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and antagonists 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) and D(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5).

Responses to rapid application of AMPA displayed pronounced and rapid desensitization. Responses to kainate showed no desensitization. Steady-state EC50 values for AMPA and kainate were 2.7 ± 0.4 μm (n = 5) and 138 ± 25 μm (n = 10), respectively. Cyclothiazide markedly increased current amplitude of responses to both agonists, whereas concanavalin A had no clear effect on either response. The selective AMPA receptor antagonist GYKI 53655 inhibited responses to kainate with an IC50 of 1.2 ± 0.08 μm (n = 5) at -70 mV. These data strongly suggest that AMPA receptors are the predominant non-NMDA receptors expressed by basal forebrain neurones.

At -70 mV, approximately 6% of control current amplitude remained, at a maximally effective concentration of GYKI 53655. This residual response displayed desensitization, was insensitive to cyclothiazide and was potentiated by concanavalin A, suggesting that it was mediated by a kainate receptor.

Current-voltage relationships for non-NMDA receptor-mediated currents were obtained from both nucleated patches pulled from neurones in culture and from acutely dissociated neurones. With 30 μm spermine in the recording pipette, currents frequently displayed double-rectification characteristic of non-NMDA receptors with high Ca2+ permeabilities. Ca2+ permeability, relative to Na+ and Cs+, was investigated using constant field theory. The measured Ca2+ to Na+ permeability coefficient ratio was 0.26-3.6; median, 1.27 (n = 15).

Current flow through non-NMDA receptors was inhibited by Ca2+, Cd2+ and Co2+ ions. At a holding potential of -70 mV, a maximally effective concentration of Cd2+ (> 30 mm) reduced current amplitude by approximately 90%, with an IC50 of 44 μm. In six out of seven cells tested, block by Cd2+ was voltage sensitive.

Ca2+ permeability of many of the non-NMDA receptors expressed by magnocellular basal forebrain neurones may underlie the unusual sensitivity of cholinergic basal forebrain neurones to non-NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity.

The rat basal forebrain consists of a number of diffuse nuclei distributed within the medial septum, vertical and horizontal limbs of the diagonal band of Broca, and the nucleus basalis, the latter falling within the boundaries of the substantia innominata and corresponding to the nucleus basalis of Meynert in primates. These nuclei are composed of heterogeneous collections of cells, including a large population of magnocellular neurones which provide the principal source of cholinergic afferents to the neocortex, hippocampus, olfactory bulb and amygdala (Mesulam, 1995). Loss of cholinergic afferents to these cortical regions is thought to be an important factor in Alzheimer's disease (Perry, Tomlinson, Blessed, Bergmann, Gibson & Perry, 1978; Whitehouse, Price, Struble, Clark, Coyle & DeLong, 1982).

One condition which commonly leads to cellular damage or death is an excessive intracellular free Ca2+ concentration, such as may result from the stimulation of Ca2+-permeable glutamate receptors. This is termed excitotoxicity. Evidence suggesting that excitotoxicity plays a role in many forms of CNS injury is very strong (Choi, 1995). These conditions include hypoxic/ischaemic injury (Choi, 1995), which has been proposed to contribute to cytotoxicity in Alzheimer's disease (Yankner, 1996). In addition, exposure to β-amyloid peptides, which are a characteristic feature of Alzheimer's tissue, increases neuronal sensitivity to excitotoxicity (Mattson, Cheng, Davis, Bryant, Lieberburg & Rydel, 1992) by disrupting Ca2+ homeostasis (Mattson, Barger, Cheng, Lieberburg, Smith-Swintosky & Rydel, 1993).

Throughout the mammalian CNS, fast synaptic responses to glutamate are mediated by ionotropic glutamate receptors of two classes: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptors (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994). Non-NMDA receptors can be further subdivided into AMPA and kainate receptors (Bettler & Mulle, 1995). Cloning studies have revealed four AMPA receptor subunits, termed GluR1-GluR4, and five kainate receptor subunits, termed GluR5-GluR7, KA1 and KA2 (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994). NMDA and non-NMDA receptors have integral ion channels which are permeable to univalent cations. It has been known for a long time that NMDA receptors are also permeable to some divalent ions, including Ca2+; hence, excitotoxicity has been thought to result from Ca2+ influx through the NMDA receptor. A minority of non-NMDA receptors also exhibit significant Ca2+ permeability. The Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors is determined by their subunit composition. Receptors expressing the GluR2 subunit have low Ca2+ permeabilities, whereas others have higher Ca2+ permeabilities (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994).

Cholinergic neurones are unusually susceptible to non-NMDA receptor-mediated toxicity in vivo (Dunnett, Everitt & Robbins, 1991; Page, Sirinathsinghji & Everitt, 1995). This toxicity is dependent on extracellular Ca2+ concentration and follows a rise in intracellular free Ca2+ concentration (Yin, Lindsay & Weiss, 1994), strongly suggesting that cell death results directly or indirectly from a non-NMDA receptor-mediated rise in intracellular free Ca2+ concentration. Immunocytochemical approaches indicate that throughout the basal forebrain a large proportion of cholinergic magnocellular neurones express the GluR4 subunit, whereas only a small proportion express GluR1, 2 or 3 (Page & Everitt, 1995). One might, therefore, expect that a significant proportion of magnocellular basal forebrain neurones express Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors and that this might explain the unusual sensitivity of magnocellular neurones to AMPA receptor-induced excitotoxicity.

Functional ionotropic glutamate receptor-mediated whole-cell currents have been described in septal neurones (Schneggenburger, Zhou, Konnerth & Neher, 1993b), where combined electrophysiological and fluorimetric measurements indicated that non-NMDA receptors may be of a Ca2+-permeable subtype. In contrast, embryonic septal neurones express functional NMDA and non-NMDA receptors with low Ca2+ permeabilities (Kumamoto & Murata, 1995).

Kumamoto & Murata (1995) and Schneggenburger et al. (1993b) examined only septal neurones. However, all regions of the basal forebrain are extensively innervated by glutamatergic fibres (Carnes, Fuller & Price, 1990), and the majority of studies in which cholinergic neurones were lesioned using glutamate receptor agonists were confined to the nucleus basalis. We have, therefore, investigated the functional properties of non-NMDA receptors expressed by rat magnocellular basal forebrain neurones from both septum and nucleus basalis in dissociated culture using electrophysiological techniques, with a view to (i) quantifying the Ca2+ permeabilities of magnocellular neurones throughout the basal forebrain, and (ii) determining whether magnocellular basal forebrain neurones express both AMPA and kainate receptors.

Some of the data presented herein have been published in abstract form (Waters, 1996).

METHODS

Culture preparation

Dissociated cultures were prepared from rat basal forebrain as described previously (Allen, Sim & Brown, 1993). Briefly, 11- to 14-day-old rat pups were killed by decapitation and the brain removed. The basal forebrain regions were isolated and physically dissociated following incubation with trypsin. Cells were plated onto poly-D-lysine-coated plastic Petri dishes and maintained in culture for between 6 and 45 days prior to use. Where neurones were to be used acutely (within 1.5-8 h of preparation), cells were plated onto borosilicate glass coverslips treated with 0.1% (w/v) Alcian Blue. Recordings were obtained only from magnocellular neurones, approximately 93% of which stain positive for acetylcholinesterase under these culture conditions (Allen et al. 1993).

Recording apparatus

Two configurations of the patch-clamp technique were employed: whole-cell and nucleated patch (Sather, Dieudonné, MacDonald & Ascher, 1992). For whole-cell recording, neurones were voltage clamped to -70 mV using a discontinuous voltage-clamp amplifier (Axoclamp-2A; Axon Instruments) operated at a sampling frequency of 4-6 kHz and a gain of 5-25 nA mV−1. The micropipette capacitance artefact was continuously monitored throughout every experiment to ensure that decay was complete by the end of each duty cycle. Nucleated patches were voltage clamped to a holding potential (Vh) of -70 mV using a continuous voltage-clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200A; Axon Instruments). Series resistance compensation of 75-90% was employed (series resistance after compensation was 2-5 MΩ).

Amplifiers were connected via a DMA interface (Labmaster TL-1-125; Axon Instruments) to a PC (Dell 325D or 466/MX) which both generated voltage commands and recorded current and voltage traces using the pCLAMP suite of software (Axon Instruments). Traces were generally filtered at 1 kHz with an 8-pole low-pass Bessel filter, prior to acquisition at 10 kHz.

Electrodes were fabricated from borosilicate glass (Clark Electromedical Instruments, Reading, UK), coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning) and fire polished. Electrode resistances were approximately 5-10 MΩ when filled with intracellular solution (see below). All experiments were conducted at room temperature (22-25°C).

During whole-cell recording, the culture dish (volume, 2-3 ml) was continuously perfused at a rate of 5-15 ml min−1 with the following solution (mm): NaCl, 123; KCl, 3; CaCl2, 2.5; MgCl2, 1.2; Hepes, 5; NaHCO3, 25; glucose, 11; and tetrodotoxin, 0.5 μm. The solution was continuously gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2, and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The corresponding intracellular solution for whole-cell recording was as follows (mm): potassium acetate, 108; KCl, 15.6; Hepes, 40; EGTA, 3; CaCl2, 0.822 (calculated free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]free), 30 nM); MgCl2, 1; Mg-ATP, 4; and Na2-GTP, 0.1. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.3 using 10-12 mm NaOH and the measured osmolarity was 260 mosmol l−1. For nucleated patch recording, the intracellular solution was (mm): caesium acetate, 102.4; CsCl, 10.6; Hepes, 40; EGTA, 3; CaCl2, 0.822 ([Ca2+]free, 30 nM); MgCl2, 1.2; Mg-ATP, 4; Na2-GTP, 0.1; and spermine, 30 μm. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 using 10-12 mm NaOH and the measured osmolarity was 250 mosmol l−1. The corresponding extracellular solution was as for whole-cell recording, except that the NaCl content was reduced to 110 mm to adjust the osmolarity to that of the intracellular solution.

Drug application

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), (S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), kainate, domoate, quisqualate, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), D(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5), (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid ((1S,3R)-ACPD), L(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (l-AP4) and cyclothiazide were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). Stock solutions were prepared at appropriate concentrations in 1 equiv NaOH, except for cyclothiazide which was dissolved into DMSO at 100 mm. Spermine and concanavalin A (ConA; type IV) were obtained from Sigma and dissolved directly into intra- and extracellular solutions, respectively, no more than a few hours prior to use. GYKI 53655 (1-(4-aminophenyl)-3-methylcarbamyl-4-methyl-7,8-methylenedioxy-3,4-dihydro-5H-2,3-benzodiazepine) was a gift from Eli Lilly & Co. and was dissolved into DMSO to give a stock solution of 100 mm.

Drugs were applied by one of three routes: bath superfusion, focal pressure ejection or using a fast-stepper device. Application by pressure ejection required the positioning of the tip of a pipette (tip diameter, ∼1 μm) within 10 μm of the cell soma. Ejection pressure was approximately 30-40 kPa. The most rapid application was offered by the fast-stepper device, which consisted of a reservoir of test solution which fed, by gravity, into a truncated pipette (tip diameter, 50-150 μm). The pipette was mounted onto a mechanical step translator such that a single motion directed the stream of test solution flowing from the tip of the pipette alternately towards and away from the cell soma and proximal dendrites. The tip of the perfusion pipette was positioned approximately 100 μm from the cell soma and was usually fabricated with a bend in it such that the stream of test solution flowed parallel to the base of the recording chamber, thereby reducing mixing with the bath solution. The distance of translation was 0.5-1 mm. To ensure that under control conditions test solution (which passed continuously into the recording chamber) flowed to waste without contacting the neurone under examination, another truncated electrode (tip diameter, 100-200 μm) was positioned approximately 100-150 μm from the cell soma. Control solution flowed continuously through this pipette, angled approximately perpendicular to the flow of test solution and towards the outflow from the recording chamber. The linear velocity of the translator motor was approximately 0.025 m s−1, and hence mechanical translation of the pipette tip across a cell body of diameter 25 μm would occur in approximately 1 ms. Measurements using the same device for application to an excised patch approximately 2 μm in diameter indicated that the solution exchange time was approximately 15 times slower than the mechanical translation. It is therefore estimated that solution exchange around the cell body using the stepper device required a minimum of 15 ms.

Dose dependence data

Dose dependence data from individual cells were fitted using an independent binding model of the form:

where n is the Hill coefficient and ymin and ymax are the fitted or constrained minimum and maximum currents, respectively. Maximum current amplitude for each cell was derived from the fitted sigmoid. Dose-response data from individual cells were pooled by normalizing to these maxima, and the means and standard errors for the normalized current values were calculated for each agonist concentration. Mean EC50 and Hill slope values were calculated from the values for individual cells. A curve was then plotted, constrained to these mean EC50 and Hill slope values and to minima and maxima of 0 and 1, respectively. Numbers of cells are given in parentheses.

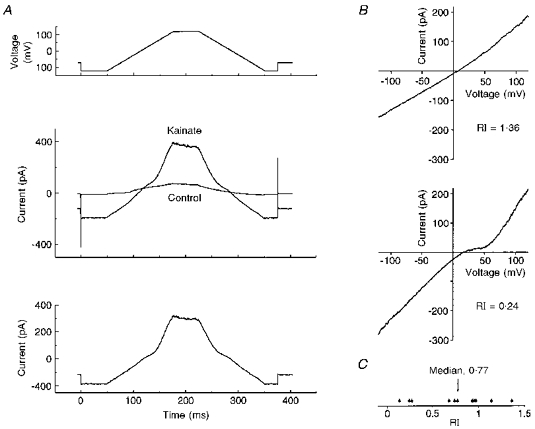

Rectification index

The degree of rectification of an I-V relationship was quantified using a rectification index (RI) defined as the ratio of slope conductances at +35 and -60 mV. Slope conductances were measured following differentiation of the I-V relationship with respect to voltage.

Ca2+ permeability measurements

Freshly dissociated cells were voltage clamped using the whole-cell variant of the patch-clamp technique and discontinuous single-electrode voltage clamp. The intracellular solution was as follows (mm): CsF, 30; CsOH, 65 (pH 7.3); Hepes, 40; BAPTA, 30; and spermine hydrochloride, 30 μm. Measured osmolarity was 307 mosmol l−1.

Cells were bathed in an extracellular solution identical to that given above for whole-cell recording except for the addition of 20 mm mannitol to increase the osmolarity to that of the intracellular solution. After obtaining the whole-cell recording configuration, the extracellular solution was exchanged for one of the following three solutions. (i) Ca2+ extracellular solution (mm): CaCl2, 100; Ca(OH)2, 2.27; Hepes, 10; and d-mannitol, 60. (ii) Na+-Ca2+ extracellular solution (mm): NaCl, 50; NaOH, 4; CaCl2, 50; Hepes, 10; and d-mannitol, 80. (iii) Na+ extracellular solution (mm): NaCl, 100; NaOH, 4; CaCl2, 1; Hepes, 10; and D-mannitol, 110. Each of these solutions was at pH 7.3 and had an osmolarity of 300-310 mosmol l−1.

Current-voltage (I-V) relationships were generated by imposing voltage ramps from -100 to +100 mV, and back to -100 mV (rate of ramp, 1 mV ms−1) under control conditions and in the presence of 1 mm kainate. Several (generally five) consecutive traces (filtered at 1 kHz) were averaged for each condition (±kainate). An I-V relationship for a kainate-induced current could then be calculated by subtracting the mean I-V relationships in the presence and absence of kainate. In order to allow for any voltage-clamp error under these two conditions, subtractions were performed on I-V relationships plotted using attained rather than command potentials. The quantities of kainate added to extracellular solutions were adjusted to account for binding to Ca2+ (Gu & Huang, 1991). A free kainate concentration of 1 mm was achieved by the addition of 1, 1.347 and 1.7 mm kainate to Na+, Na+-Ca+ and Ca2+ extracellular solutions, respectively.

Reversal potentials for the kainate-sensitive currents in each of these solutions were measured from plotted I-V relationships. Reversal potentials were corrected for a measured junction potential of -3 mV in each of these solutions. From these reversal potential measurements, relative permeabilities for the Cs+, Na+ and Ca2+ ions permeating non-NMDA receptors were calculated using the extended constant field equation (Spangler, 1972; Piek, 1979):

where Vrev is the reversal potential, and R, F and T are the gas and Faraday constants and the absolute temperature, respectively, and:

and

where aα denotes the ion activity of ion α and the superscripts i and o refer to intracellular and extracellular activites, respectively. Pα represents the permeability coefficient for ion α through the non-NMDA receptor.

Activity coefficients for metal ion salts were calculated according to Pitzer & Mayorga (1973). Ion activities were calculated from these values by assuming that (i) the activities of Cs+ and of Na+ ions in these solutions were equal to the activities of the corresponding salts, and (ii) the activity coefficient of the Ca2+ ion was equal to the square of the activity coefficient of the corresponding salt (Guggenheim convention). Calculated ion activites were as follows: , 75.57 mm in the intracellular solution; , 37.09 mm and 80.19 mm in Na+-Ca2+ and Na+ extracellular solutions, respectively; and , 27.26 mm, 13.64 mm and 0.29 mm in Ca2+, Na2+-Ca2+ and Na2+ extracellular solutions, respectively.

RESULTS

Responses to glutamate in culture

In all cells tested, application of glutamate to magnocellular basal forebrain neurones caused depolarization and, where depolarization was sufficiently rapid, firing (Fig. 1A). Prolonged application resulted in a sustained depolarization in the continued presence of glutamate. This depolarization was accompanied by a decrease in input resistance. The observed decrease in input resistance resulted from ionotropic glutamate receptor activation, rather than voltage-dependent activation of other conductances, since the observed fall in input resistance was not prevented by manually clamping the cell back to -70 mV (not shown). Under voltage clamp (Vh, -70 mV), step application of glutamate produced an initial large, transient inward current which rapidly decayed to a smaller, steady-state value (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Responses to glutamate.

A, voltage recording from a neurone with a resting membrane potential (Vm) of -76 mV. Arrowheads mark applications of 100 μm glutamate for 30 ms by pressure application to the soma. Inset, the first response on an expanded time scale. B, non-NMDA receptor-mediated response to 100 μm glutamate from a neurone voltage clamped to -70 mV. Glutamate was applied using a mechanical stepper device, and with 1.2 mm MgCl2 and 10 μm AP5 in the extracellular solution.

Receptor pharmacology

The presence of functional NMDA and non-NMDA receptors was readily demonstrated pharmacologically (Fig. 2). AMPA, kainate and NMDA (in Mg2+-free extracellular solution) each elicited inward currents. Responses to AMPA and to kainate were selectively antagonized by the non-NMDA receptor antagonist CNQX (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly, responses to NMDA were selectively antagonized by the NMDA receptor antagonist AP5, and by extracellular Mg2+ ions (Fig. 2C). Responses to glutamate, AMPA, kainate and NMDA could all be inhibited by 10 mm kynurenic acid (data not shown).

Figure 2. Receptor pharmacology.

Current traces from three neurones, held at -70 mV, to each of which was applied a different ionotropic glutamate receptor agonist. Arrowheads mark agonist applications for 200 ms each, by pressure ejection. Applications were repeated at intervals of 20-30 s. Voltage errors at the peaks of agonist-induced currents were less than 1 mV. (Voltage traces are excluded for clarity.) A, B and C each show three sequential responses to an ionotropic glutamate receptor agonist under various conditions. Responses to AMPA and to kainate were reversibly inhibited by CNQX. Responses to NMDA (recorded in the absence of extracellular Mg2+ and without added glycine) were reversibly inhibited by AP5 and by extracellular Mg2+ ions.

Application of the metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists (1S,3R)-ACPD and L-AP4 (10-100 μm) had no observed effect in any of the cells tested (n = 4). However, this apparent lack of any metabotrophic receptor-mediated responses may simply reflect a loss of intracellular messengers as a result of dialysis of the cell during whole-cell recording (Shirasaki, Harata & Akaike, 1994).

Responses to rapid application of AMPA or quisqualate exhibited similar kinetics to those evoked by glutamate, consisting of a fast activating current exhibiting rapid desensitization to a steady-state level. In contrast, responses to kainate and domoate exhibited a slower rate of activation and lacked desensitization (see Fig. 3A). Such kinetics are characteristic of the action of these agonists at AMPA receptors; were kainate acting at a kainate receptor, the response would be expected to exhibit a desensitizing component (see, for example, Paternain, Morales & Lerma, 1995). Note that whilst pressure application of agonists was sufficiently rapid to resolve the initial desensitizing component in some cases (see Fig. 3A), in others, particularly when applying low concentrations of an agonist, it was not (see Fig. 4A). In some cases the lack of an intial transient component could also have resulted from desensitization as a result of slight leakage of agonist from the ejection pipette. With bath application of these agonists, only the steady-state component of the current could be discerned.

Figure 3. Non-NMDA agonist pharmacology.

A, typical kinetics of responses to AMPA and to kainate applied by pressure ejection. B, dose-response relationships for steady-state responses to AMPA and to kainate. Data were derived from neurones held at -70 mV (numbers of cells in parentheses). In order to obtain data for the two highest kainate concentrations, cells were clamped to -40 mV, reducing voltage error to acceptable proportions (< 5 mV). Data generated at -40 and at -70 mV were very similar and, hence, were pooled to generate the presented kainate dose-response curve.

Figure 4. Effects of cyclothiazide and ConA.

A, effects of cyclothiazide and of ConA on responses to AMPA recorded from a single cell. AMPA (3 μm) was repeatedly applied by pressure application with the cell clamped to -70 mV. Cyclothiazide (100 μm) and ConA (0.3 mg ml−1) were bath applied, and cyclothiazide was also included in the pressure-application pipette where appropriate. Top, plot in which each data point represents peak current amplitude for a single agonist application. Bottom, sample traces from which the current amplitude measurements were made. The displayed traces are those labelled with arrows in the graph. Voltage traces are shown below the current traces. B, analagous data showing effects of cyclothiazide and of ConA on responses to 10 μm kainate.

Dose-response curves were constructed for steady-state currents evoked in response to bath application of AMPA and kainate (Fig. 3B). EC50 and Hill slope values were 2.7 ± 0.4 μm (n = 5) and 1.35 ± 0.18, respectively, for AMPA, and 138 ± 25 μm (n = 10) and 1.24 ± 0.09, respectively, for kainate. These values, particularly the low micromolar EC50 value for AMPA, indicate that these responses are mediated by AMPA rather than kainate receptors (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994).

Maximally effective concentrations of AMPA and kainate elicited very large steady-state currents. The current amplitude also increased with time in culture. Maximal kainate-induced responses increased from approximately 2 nA at 5 days in vitro to around 13 nA after 16 days in vitro (Vh, -70 mV). All dose-response data were obtained from cells within this age range, as outside this age bracket currents were either too small or too large to permit the accurate measurement of evoked currents across the full range of agonist concentrations. Mean cell capacitance also increased during the first 10 days in vitro. Thereafter it remained largely constant up to 31 days in vitro (beyond which no measurements were made). Capacitance values for cells maintained for between 10 and 31 days in vitro were normally distributed with a mean of 61 ± 1.6 pF (n = 102). Assuming a cell capacitance of 60 pF and a current amplitude of 13 nA, this corresponds to a current density of approximately 220 pA pF−1.

Effects of cyclothiazide and of concanavalin A

Benzothiazide diuretics, such as cyclothiazide, and plant lectins, such as concanavalin A (ConA), have been found useful in distinguishing between AMPA and kainate receptor-mediated responses. Cyclothiazide inhibits desensitization of AMPA, but not kainate, receptors; in contrast, whilst lectins have been found to inhibit desensitization at both AMPA and kainate receptors, ConA exerts a much stronger effect at kainate receptors (Wong & Mayer, 1993).

Responses of basal forebrain neurones to AMPA were potentiated by 100 μm cyclothiazide (n > 20), but not 0.3 mg ml−1 ConA (n = 6), even after 30 min of exposure (see Fig. 4A). In addition to increasing current amplitude, cyclothiazide also altered the kinetics of the response to AMPA by greatly reducing the rate of desensitization (Fig. 4A), further reinforcing the suggestion that responses to AMPA result primarily from activation of AMPA rather than kainate receptors.

A similar protocol was used to investigate the effects of cyclothiazide and ConA on responses to kainate (Fig. 4B). Again, 100 μm cyclothiazide increased current amplitude (n = 10), indicating the involvement of an AMPA receptor. The effect of 0.3 mg ml−1 ConA was less clear; in the majority of cells ConA produced no discernible effect, but in a few cells ConA appeared to potentiate responses to kainate by approximately 50%, indicating the possible additional involvement of kainate receptors. However, in most cells it was difficult to resolve clearly the potentiation (if there was any) over the natural variation in the control responses (n = 10). Therefore, in order to examine more clearly the possibility that basal forebrain neurones might also express functional kainate receptors, we attempted to isolate pharmacologically the kainate receptor-mediated current.

In the first instance we step applied a low concentration of kainate (10 μm) to the cells. At this concentration one should achieve near-maximal activation of any kainate receptors whilst at the same time minimizing any contamination due to AMPA receptor activation (see Fig. 3B). Under such conditions, kainate induced a current exhibiting pronounced desensitization. In the example shown in Fig. 5Bb the decay phase was fitted by a single exponential of 589 ms. This value is similar to the slow component of desensitization reported by Huettner (1990; τ, ∼400 ms) and Wong & Mayer (1993; τ, ∼700 ms) for kainate-mediated activation of kainate receptors. However, in both these publications the authors also observed an initial fast component of desensitization of the order of 40-60 ms. A similarly rapid component could be present in basal forebrain neurones, though because of the limitations of our agonist application system we would not expect to be able to resolve it.

Figure 5. Currents recorded in GYKI 53655.

A, dose-dependent inhibitory effect of GYKI 53655. Kainate was applied using a stepper device, and GYKI 53655 by bath application. Kainate response was measured as peak current amplitude. B, kinetics of responses to kainate. a, effects of bath application of 100 μm GYKI 53655 on a response to pressure ejection of 100 μm kainate, showing decreased response amplitude with time in the presence of GYKI 53655. b, kinetics of response to stepper application of 10 μm kainate. Current decay was fitted by a first-order exponential with a time constant of 589 ms (dashed line). Rise time (10-90%) of response, 167 ms. C, effects of 100 μm cyclothiazide (a) and 0.3 mg ml−1 ConA (b) on responses to pressure application of 100 μm kainate, illustrating desensitization to kainate. All neurones were voltage clamped to -70 mV. A discontinuous voltage-clamp amplifier was employed for the experiments illustrated in A and C, and a continuous voltage-clamp amplifier for the experiments illustrated in B. Where appropriate, cyclothiazide, but not ConA, was included in the pressure-application pipette with kainate and GYKI 53655.

GYKI 53655 reveals a kainate receptor

AMPA receptors were inhibited using the non-competitive AMPA receptor antagonist GYKI 53655 (Paternain et al. 1995). The concentration dependence of the inhibition produced by GYKI 53655 on responses to 100 μm kainate was examined (Fig. 5A). The IC50 and Hill slope values for GYKI 53655 were 1.2 ± 0.08 μm and -0.89 ± 0.06 (n = 5), respectively, consistent with previously published data on AMPA receptors (Paternain et al. 1995). The fitted curve also indicates that a residual current, accounting for 6.1 ± 1.6% of the control current amplitude, remained in the presence of maximal concentrations of GYKI 53655.

Figure 5Ba shows an example of the effect of 100 μm GYKI 53655 on the response to pressure application of 100 μm kainate. (Dose-response data indicated that 100 μm GYKI 53655 reduced current amplitude to approximately 8% of control.) Following maximal inhibition with GYKI 53655, the remaining resistant kainate-induced current typically exhibited transient kinetics (Fig. 5Ba). Mean current amplitude at the end of agonist application (pseudosteady state) was 70% of peak current amplitude (n = 7). Since it has been reported that 2,3-benzodiazepines do not display use dependence (Donevan & Rogawski, 1993), it seems likely that this decay may result from desensitization such as one would expect to observe were kainate acting at a kainate receptor.

The identity of the receptor underlying the residual response to kainate in the presence of GYKI 53655 was further investigated using cyclothiazide and ConA (Fig. 5C). Cyclothiazide (100 μm) had little effect on responses to kainate: of the five cells to which cyclothiazide was applied, only one displayed potentiation (approximately 2-fold). ConA (0.3 mg ml−1) was applied to four cells, in all of which it reduced desensitization of the response. Mean peak to pseudosteady-state current ratio after ConA treatment was 1. ConA potentiated the pseudosteady-state current 2-fold (mean value). The effect of ConA was irreversible over the length of time for which recordings were continued after removing kainate from the bath (approximately 7 min). These findings are consistent with the expression by basal forebrain neurones of a kainate receptor population in addition to the functionally more significant (under these recording conditions) AMPA receptor population.

Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors

The divalent ion permeability of an AMPA receptor subunit is largely determined at the so-called Q/R/N site (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994). GluR2 subunits possess an arginine (R) residue at this site, severely restricting divalent ion permeation of the channel. In contrast, GluR1, GluR3 and GluR4 possess a glutamine (Q) residue at this site and are permeable to some divalent ions, including Ca2+. In heteromeric assemblies GluR2 subunits dominate Ca2+ permeability. Likewise, the Q/R/N site governs the shape of the current-voltage (I-V) relationship: a linear or mildly outwardly rectifying relationship being characteristic of a receptor containing a GluR2 subunit, whilst the I-V relationship of receptors containing no GluR2 subunit typically exhibits double rectification. Thus for non-NMDA receptors, the shape of the I-V relationship is indicative of subunit composition and divalent ion permeability.

The I-V relationships of the non-NMDA receptors expressed by basal forebrain neurones were examined using nucleated patches which afford excellent stability and can be accurately voltage clamped. The voltage protocol imposed on nucleated patches included an ascending (positive-going) ramp followed by a descending (negative-going) ramp. This permitted resolution of any hysteresis which occurred in the current traces (see Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. I-V relationships recorded from nucleated patches.

A, top, voltage protocol used to generate I-V relationships (inter-episode holding potential, -70 mV). For each condition, ten replicates were recorded and averaged off-line. Middle, currents recorded in the absence and presence of 1 mm kainate using this voltage protocol. Bottom, leak-subtracted current induced by 1 mm kainate, calculated from the data given in the middle panel. Two examples of I-V relationships are presented in B, one displaying little rectification (RI, 1.36), and the other pronounced double rectification (RI, 0.24). C, the distribution of rectification indices for nucleated patch I-V relationships (n = 11).

Following excision, patches were left for 20-30 min to achieve maximal dialysis and inhibition of contaminating K+ currents. Under these conditions, the I-V relationship exhibited weak hysteresis (see Fig. 6A, middle) due to time-dependent inactivation of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels. Since the Ca2+ current was less pronounced on the descending than the ascending ramp, and the effect of non-NMDA receptor activation on the Ca2+ current was unknown, the descending limb of the current response was used in the generation of I-V relationships (see Fig. 6A). I-V relationships were generated from eleven nucleated patches in the presence of 30 μm intracellular spermine. Rectification ranged from doubly rectifying to linear (see Fig. 6B). Rectification was quantified using a rectification index (RI; see Methods). Calculated values ranged from 0.13 to 1.36, with a median of 0.77. The distribution of rectification indices is illustrated in Fig. 6C.

Determination of permeability coefficients for Ca2+, Na+ and Cs+

The rectification of the current-voltage relationship from nucleated patches suggests that many basal forebrain neurones express Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors, but provides neither direct nor quantitative evidence for this. In order to quantify Ca2+ permeability, we carried out further experiments using constant field theory to determine permeability coefficient ratios for Ca2+, Na+ and Cs+ ions. This approach requires determining the reversal potential of the receptor-mediated current in different solutions of known ionic composition. For these experiments, acutely dissociated neurones were used, since it was possible that the non-NMDA receptor subunits expressed by neurones in culture may be influenced by culture conditions. The solutions for these experiments were designed such that the intracellular side of the membrane was only exposed to a known concentration of Cs+ (initially as chloride, acetate and hydroxide salts), no other metal ions being present. This permitted simplification of the constant field equations used to calculate divalent to monovalent cation permeability coefficient ratios.

Ca2+ buffering was initially provided by 5 mm EGTA (no added Ca2+). This proved insufficient to prevent Ca2+-dependent inhibition of the Ca2+ current in the elevated extracellular Ca2+ concentrations used for these experiments, indicating that intracellular Ca2+ levels were rising during the recording (Fig. 7A). Under such conditions, outward current through non-NMDA receptors could be carried by both Cs+ and Ca2+ ions, invalidating the simplifying assumptions used in the constant field calculations. This problem was overcome by substituting intracellular EGTA for 20 mm BAPTA (Fig. 7B). However, even with 20 mm intracellular BAPTA we frequently observed Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ current inhibition during the application of kainate (Fig. 7C). Whilst this is interesting (since it suggests that Ca2+ may enter through the non-NMDA receptor), this situation was again not satisfactory and, thus, in order to prevent it, the concentration of BAPTA was increased to 30 mm. The amplitude of the calcium current was reduced by the inclusion of 30 mm CsF in the pipette.

Figure 7. The effects of intracellular BAPTA and CsF.

BAPTA and CsF were used to stabilize and inhibit Ca2+ current which contaminated I-V relationships recorded from freshly dissociated neurones. Each panel shows a series of traces, recorded at 30 s intervals and overlaid for comparison. A, traces recorded in 50 mm extracellular Ca2+ with 5 mm intracellular EGTA. Ca2+ current run-down is evident. B, 100 mm extracellular Ca2+ and 20 mm intracellular BAPTA. Ca2+ current amplitude is stable. C, 100 mm extracellular Ca2+ and 20 mm intracellular BAPTA. Under these conditions, application of 1 mm kainate reduces Ca2+ current amplitude. D, 100 mm extracellular Ca2+ and 30 mm intracellular BAPTA. Addition of 30 mm CsF to the intracellular solution reduces and stabilizes Ca2+ current amplitude.

I-V relationships were generated using voltage ramps from -100 to +100 mV. (Note, hysteresis was more pronounced than with nucleated patches, probably because 30 mm BAPTA prevented Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the Ca2+ current; see Fig. 8.) Analysis of the descending limb of the protocol did not entirely overcome contamination by the Ca2+ current. Furthermore, the predicted reversal potential for the AMPA receptor-mediated current was close to the peak of the Ca2+ current (see Fig. 8). Hence, it is likely that reversal potentials measured in Na+ and Na+-Ca2+ extracellular solutions are more accurate than those made in Ca2+ extracellular solution, where the Ca2+ current was most pronounced. Therefore, relative permeabilities were calculated using reversal potential measurements for the two Na+-containing solutions. Whilst this required the assumption that the Ca2+ activity in Na+ extracellular solution was negligible, it is likely that this approximation will influence the calculated permeability less than would errors in reversal potential measurement. Reversal potentials were measured from the intersection of these ramps (rather than subtracting the control from the trace in kainate and measuring the reversal potential from this trace). Thus, data from cells where the degree of Ca2+ current ‘contamination’ was pronounced were identified and discarded.

Figure 8. I-V relationship hysteresis increases with extracellular Ca2+ concentration.

Hysteresis resulted from Ca2+ current activity, which became more conspicuous and shifted towards positive potentials as extracellular Ca2+ concentration was increased. Each of the six panels shows two curves, one derived in the absence of kainate (dotted line) and one in the presence of 1 mm kainate (continuous line). Traces are presented for all three extracellular solutions. A, Na+ extracellular: 100 mm Na+, 1 mm Ca2+. B, Na+-Ca2+ extracellular: 50 mm Na+, 50 mm Ca2+. C, Ca2+ extracellular: 100 mm Ca2+. For each solution, current traces corresponding to both ascending and descending limbs of the voltage protocol are presented, ascending ramp on the left and descending ramp on the right. All traces are from the same cell.

I-V relationships were recorded from fifteen acutely dissociated neurones, and displayed a range of RI values and relative Ca2+ permeabilities. Reversal potential shifts between Na+ extracellular solution and Na+-Ca2+ extracellular solution, ion permeability coefficient ratios and RI values are presented in Table 1. Two examples of I-V relationships are presented in Fig. 9A: one doubly rectifying and the other outwardly rectifying. RI values were distributed from 0 to 3.56, with a median of 1.38 (Table 1 and Fig. 9B).

Table 1.

Ca2+ permeability and rectification data from acutely dissociated neurones

| Cell | Vrev shift | PNa/PCs | PCa/PCs | PCa/PNa | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | +6.5 | 0.92 | 3.32 | 3.60 | 0.09 |

| 2 | +7 | 0.89 | 2.49 | 2.80 | 1.39 |

| 3 | +1 | 0.98 | 2.42 | 2.50 | 1.40 |

| 4 | +1 | 0.92 | 1.58 | 1.71 | 0.82 |

| 5 | +1 | 0.91 | 1.54 | 1.70 | 0.97 |

| 6 | −1.5 | 1.08 | 1.59 | 1.47 | 2.52 |

| 7 | −1.5 | 1.04 | 1.50 | 1.44 | 11.4 |

| 8 | −4 | 1.08 | 1.37 | 1.27 | 1.41 |

| 9 | −4 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 3.56 |

| 10 | −9.5 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 1.95 |

| 11 | −7 | 1.36 | 1.26 | 0.92 | 0 |

| 12 | −8 | 1.10 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.51 |

| 13 | −4 | 1.53 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 1.47 |

| 14 | −12 | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.36 |

| 15 | −15 | 1.45 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 1.20 |

See text for details.

Figure 9. I-V relationships from acutely dissociated neurones.

A, two examples of leak-subtracted kainate-induced I-V relationships from freshly dissociated neurones, one from a neurone expressing non-NMDA receptors with high Ca2+ permeability (top), and the other from a neurone expressing non-NMDA receptors with low Ca2+ permeability (bottom). Both traces were recorded in 1 mm extracellular Ca2+. B, distribution of rectification index (RI) values for I-V relationships from nucleated patches.

Ion permeability coefficient ratios were calculated from reversal potential measurements using constant field theory. PNa/PCs values were tightly grouped, describing a range of 0.87-1.53. Values for PCa/PCs were more widely scattered; range, 0.33-3.32. The resulting PCa/PNa range was 0.26-3.6; median, 1.27. The scatter for each of these ratios is illustrated in Fig. 10. These data suggest that basal forebrain neurones express AMPA receptors with various subunit compositions, the majority of basal forebrain neurones expressing Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors. The observed range of ion permeabilities presumably reflects the expression either of a mixture of Ca2+-permeable and -impermeable receptors in varying proportions or of receptors with different Ca2+ permeabilities in different cells.

Figure 10. Permeability coefficient ratios.

The distribution of permeability coefficient ratios for Ca2+, Cs+ and Na+ ions derived using constant field theory from reversal potential shift data from fifteen neurones. Each symbol represents the ratio from a single neurone. The median value for PCa/PCs is marked.

Divalent ion block of AMPA receptors

In addition to shifting the reversal potential, elevating extracellular Ca2+ also reduced the amplitude of the kainate-induced current. This effect was observed in all cells, regardless of relative Ca2+ permeability (n = 15). An example is given in Fig. 11A. Elevation of extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 1 to 10 mm (in the presence of 1 mm MgCl2) reduced current amplitude by 37 ± 2% (n = 3).

Figure 11. Non-NMDA receptor blockade by divalent ions.

A, effect of partial substitution of extracellular Na+ ions with Ca2+ ions. This example is taken from a neurone with approximately equal permeability coefficients for Na+ and Ca2+, yet current amplitudes both at negative potentials and at potentials positive to approximately +50 mV are reduced upon replacement, suggesting that Ca2+ may act as a channel blocker in addition to permeating the channel. B, dose dependence of the blocking effect of Cd2+ on responses to 300 μm kainate. C, traces from three neurones illustrating the voltage sensitivity of block by 3 mm Cd2+. Central sections of each trace are excluded for clarity. Inset, corresponding I-V relationships for the currents to 300 μm kainate prior to and following addition of Cd2+ to the bathing solution.

Cd2+ and Co2+ also reduced kainate-induced current amplitude. The dose dependence of the effect of extracellular Cd2+ was examined in cells clamped to -70 mV (without intracellular spermine). The resulting dose-response relationship is given in Fig. 11B. The fitted curve yields an IC50 of 44 μm, a slope of -0.67 and a maximum inhibition of 87% (calculated by extrapolation of the fitted curve). Whilst the effects of Cd2+ on kainate-elicited currents were reversible, application of high concentrations of Cd2+ led to deterioration of the recording. This prevented the construction of a full curve from any one cell. The dose dependence was therefore examined by expressing the effect of a single Cd2+ application as a percentage reduction of current amplitude, then pooling data from many cells. This method is prone to underestimation of the slope of the true mean curve and may, therefore, account for the shallow observed slope of -0.67. The dose dependence of the effect of Co2+ was not examined, though it was less effective than similar concentrations of Cd2+. Co2+ block was observed in the sub- to low-millimolar range.

The effect of Cd2+ was voltage dependent. Of seven cells in which this was studied, six exhibited block which decreased with voltage from -100 mV towards zero. Minimum block was observed at 0 to +50 mV, with block increasing with voltage from +50 to +100 mV. All six of these cells exhibited doubly rectifying current-voltage relationships (in the presence of 30 μm intracellular spermine). The other cell studied exhibited relatively mild voltage sensitivity which increased linearly from -100 to +100 mV. This cell exhibited a mildly outwardly rectifying current-voltage relationship.

Plots of percentage block by Cd2+ against voltage are given for three cells in Fig. 11C. The top and middle traces illustrate the effects of voltage on two of the six cells exhibiting strong voltage dependence and doubly rectifying current-voltage relationships (insets). The voltage sensitivity of Cd2+ block in the cell with an outwardly rectifying current-voltage relationship is shown in the bottom trace. Note that the percentage block by 3 mm Cd2+ is less than that calculated from the dose dependence given above. This presumably results from the different solutions used, possibly from the presence of spermine in experiments where the voltage sensitivity of block was examined.

It is also interesting that divalent ion block is progressively relieved at potentials positive to approximately +50 mV, since spermine is thought to permeate the channel at these potentials (Bowie & Mayer, 1995). One interpretation of these data is that spermine relieves extracellular divalent ion block by interaction with the divalent blocker following efflux of spermine through the channel.

DISCUSSION

Evidence for expression of a kainate receptor

Inhibition of kainate-elicited current by GYKI 53655 is strong evidence that this current is largely mediated by an AMPA receptor in magnocellular basal forebrain neurones. That there remains a current in the presence of 300 μm GYKI 53655 (the limit both of solubility and of selectivity of this compound) and that this current shows desensitization to kainate, and is potentiated by ConA but not by cyclothiazide, suggest that magnocellular basal forebrain neurones also express kainate receptors. Two issues warrant further discussion: (i) the possibility of an interaction between cyclothiazide and GYKI 53655, and (ii) the magnitude of potentiation by ConA.

From published data it appears that 2,3-benzodiazepines do not influence the inhibition of desensitization by cyclothiazide. In contrast, some authors have reported relief of the inhibitory effect of 2,3-benzodiazepines by cyclothiazide. Johansen, Chaudhary & Verdoorn (1995) examined interactions at a variety of recombinant AMPA receptors and found that cyclothiazide decreased the potency of a 2,3-benzodiazepine only at AMPA receptors containing the GluR2 subunit. Therefore, it seems unlikely that such an interaction should occur at receptors displaying high Ca2+ permeability, such as observed in basal forebrain neurones. However, should such an interaction between cyclothiazide and GYKI 53655 occur at AMPA receptors expressed by basal forebrain neurones, then in the presence of GYKI 53655 one would expect to observe an increase in current amplitude upon application of cyclothiazide, as a result of relief of inhibition by GYKI 53655.

The potentiation by ConA of the residual current (in the presence of GYKI 53655) in basal forebrain neurones is slightly less than expected for a kainate receptor. For example, Partin, Patneau, Winters, Mayer & Buonanno (1993) reported a 150-fold increase in the amplitude of kainate-induced current upon ConA treatment of oocytes expressing GluR6. However, potentiation is less marked at native GluR5 receptors. For example, Wong & Mayer (1993) reported approximately 60% desensitization to kainate under control conditions (slightly more than observed for basal forebrain neurones) and approximately 3-fold potentiation of the pseudosteady-state response by ConA. Therefore, the potentiation observed in basal forebrain neurones (in the presence of 100 μm GYKI 53655) is only slightly less than reported for other native kainate receptors.

Wong & Mayer (1993) also noted that on dorsal root ganglion neurones the effects of ConA were not reversible within 20 min. The effects of ConA on GluR6 (expressed in oocytes) were also maintained for at least 10 min, in contrast to the effects on GluR1, which were largely reversed after only 3 min (Partin et al. 1993). The lack of reversal of ConA effects on the residual current in basal forebrain neurones is, therefore, more consistent with an effect at a kainate than at an AMPA receptor.

The failure to observe kainate receptor-mediated responses prior to inhibition of AMPA receptor-mediated responses has also been reported in a subset of hippocampal neurones in culture (Paternain et al. 1995). The masking of kainate receptors is likely to be particularly pronounced at high agonist concentrations since kainate receptors generally have a lower EC50 for kainate than have AMPA receptors (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994).

Ca2+ permeability measurements

Ca2+ permeabilities were calculated using constant field theory. This approach has several potential sources of error. Firstly, we have assumed that non-NMDA receptors are essentially impermeable to anions. Burnashev and associates (Burnashev, 1996; Burnashev & Sakmann, 1996; Burnashev, Villarroel & Sakmann, 1996) have considered this possibility and determined that PCl/PCs was significant for the homomerically expressed R-form subunits GluR2(R) and GluR6(R) (PCl/PCs, 0.1-0.2 and 0.7-0.8, respectively). In contrast, chloride permeabilities were insignificant for Q-form subunits and mixed Q/R-form heteromers. Thus, anion concentrations are unlikely to influence the Ca2+ permeability values calculated for Ca2+-permeable receptors (Q-form subunits) as a result of channel permeation.

Secondly, no account was made of the following factors: the junction potential between pipette solution and cytoplasm, surface potential effects (Frankenhäuser, 1960; Lewis, 1979; Green & Anderson, 1991), interactions between permeating species, and effects of voltage and ion (particularly Ca2+) concentration on measured relative permeabilties (Burnashev, Zhou, Neher & Sakmann, 1995). An alternative approach utilizing Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent indicator dyes, such as fura-2, permits Ca2+ permeability measurements under conditions more akin to those in vivo, avoiding these factors. Comparison with the constant field approach reveals that constant field theory overestimates fractional Ca2+ currents of both Ca2+-permeable and -impermeable non-NMDA receptors (Burnashev et al. 1995) and of NMDA receptors, though the two methods were considered to be ‘in reasonable agreement’ (Schneggenburger, 1996).

The relative Ca2+ permeabilities of non-NMDA receptors in magnocellular basal forebrain neurones are comparable to those calculated for other native ‘Ca2+-permeable’ non-NMDA receptors, including hippocampal type II neurones (PCa/PCs, 2.3; Iino, Ozawa & Tsuzuki, 1990), type 1 and type 2 retinal ganglion cells (PCa/PCs, 3.3 and 8.5, respectively; Leinders-Zufall, Rand, Waxman & Kocsis, 1994), avian nucleus magnocellularis neurones (PCa/PNa, 5; Otis, Raman & Trussell, 1995), hippocampal dentate gyrus basket cells (PCa/PNa, 1.59), hippocampal hilar interneurones (PCa/PNa, 1.44), auditory MNTB relay neurones (PCa/PNa, 1.12) and Bergman glial cells (PCa/PNa, 2.8; Geiger et al. 1995).

In the present study, no correlation was apparent between rectification index and calcium permeability. This may indicate that some or all neurones expressed a mixture of receptors with different divalent ion permeabilities and that in these circumstances rectification and calcium permeability may not be simply related. Alternatively, the lack of correlation may reflect different rates or extents of dialysis of spermine into different neurones.

Dialysis of spermine may also account for the apparent differences between rectification indices derived from nucleated patches and acutely dissociated neurones (compare Figs 6C and 9B). One might expect dialysis of nucleated patches to be poorer than that of whole cells, given the higher access resistance typically observed with this configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Were the endogenous intracellular spermine concentrations lower than 30 μm (the concentration in the patch pipette), the greater rectification observed in traces from whole-cell than from nucleated patch recordings could result where dialysis limits spermine access to the nucleated patch. Alternatively, the volume of the patch/cell, rather than access resistance, may be the principal factor limiting spermine exchange between cytoplasm and pipette. In this circumstance, the observed difference in rectification between nucleated patch and whole-cell recordings would result were the endogenous intracellular spermine concentration greater than 30 μm.

Bowie & Mayer (1995) used the effect of polyamines on the rectification of non-NMDA receptor I-V relationships to estimate endogenous intracellular spermine concentrations, concluding that hippocampal neurones contained 40 μm spermine and 120 μm spermidine. These data suggest that a pipette concentration of 30 μm spermine may be lower than the endogenous concentration; hence, incomplete dialysis in the whole-cell recording configuration may account for the higher median rectification index for I-V relationships from whole-cell recordings than from nucleated patches. Incomplete dialysis during whole-cell recording may also account for the poor correlation between rectification index and calcium permeability as dicussed above.

Blocking actions of extracellular divalent ions

Inhibition of current flow through non-NMDA receptors by extracellular Ca2+ (Burnashev, Monyer, Seeburg & Sakmann, 1992; Burnashev et al. 1995), Cd2+ (Mayer, Vyklicky & Westbrook, 1989; Rörig & Grantyn, 1993) and Zn2+ (Mayer et al. 1989) has been observed. No dose-response data were presented in these publications and the voltage sensitivities were not examined in detail. The results presented herein, therefore, expand the available information regarding the blocking action of divalent ions at non-NMDA receptors. Interestingly, Mayer et al. (1989) found that Zn2+ potentiated responses at a low concentration (50 μm), only inhibiting at higher concentration (1 mm). No such effect was apparent with Cd2+ and basal forebrain neurones.

Extracellular Co2+ and Ni2+ ions block the NMDA receptor in a manner similar to magnesium ions, displaying a strongly voltage-dependent block (Mayer & Westbrook, 1987). In contrast, inhibitions by Zn2+ and by Cd2+ ions are voltage independent (Mayer & Westbrook, 1987; Mayer et al. 1989). In addition, the action of Zn2+ is non-competitive (Mayer et al. 1989), suggesting that these ions may act at an allosteric site rather than inhibiting current flow by open channel block. In contrast, the block by Cd2+ ions of basal forebrain non-NMDA receptors was voltage dependent, suggesting that Cd2+ ions probably act as open channel blockers.

Comparison with septal neurones

Kumamoto & Murata (1995) took a similar approach to that presented in the present study, examining I-V relationships for non-NMDA receptor-mediated currents from cultured fetal rat cholinergic septal neurones. I-V relationships for quisqualate-, AMPA- and kainate-elicited currents were all slightly outwardly rectifying, though this may be a result of omission of spermine from their intracellular solution. However, the authors also reported negligible (approximately zero) Ca2+ permeability of non-NMDA receptors. This is important, since Ca2+ permeability is thought to be independent of spermine (Kamboj, Swanson & Cull-Candy, 1995; Burnashev, 1996). Presumably either neurones from fetal rats express different non-NMDA receptor subunits than those from 13-day-old animals, or septal neurones express receptors with lower divalent ion permeabilities than neurones from more caudal regions of the basal forebrain.

Ca2+ permeabilities of non-NMDA receptors in postnatal septal neurones have been studied by combined fluorescence and electrophysiological methods (Schneggenburger, Tempia & Konnerth, 1993a; Schneggenburger et al. 1993b). The authors studied responses in 14- to 20-day-old rat septal slices and found that the fractional Ca2+ current through non-NMDA receptors was 1.2-1.4%, and concluded that the cells expressed receptors with low to moderate Ca2+ permeabilities. Whilst it is difficult to compare these fractional Ca2+ current measurements with constant field calculations directly, comparison with published data suggests that at both pre- and postnatal stages septal neurones may express non-NMDA receptors with lower Ca2+ permeabilities than other cholinergic basal forebrain neurones. Therefore, whilst cholinergic septal neurones are susceptible to non-NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity (Yin et al. 1994), one might expect that cholinergic neurones from more caudal regions of the basal forebrain show greater sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Eisai London Research and the Medical Research Council. GYKI 53655 was a gift from Eli Lilly & Co. The authors would also like to thank Professor David Brown, in whose laboratories the experiments were conducted, for advice and for comments on the manuscript, and Joan Sim for assistance with the tissue culture method and for comments on the manuscript.

References

- Allen T G J, Sim J A, Brown D A. The whole-cell calcium current in acutely dissociated magnocellular cholinergic basal forebrain neurones of the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1993;460:91–116. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettler B, Mulle C. AMPA and kainate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:123–139. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00141-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie D, Mayer M. Inward rectification of both AMPA and kainate subtype glutamate receptors generated by polyamine-mediated ion channel block. Neuron. 1995;15:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N. Calcium-permeability of glutamate-gated channels in the central nervous system. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1996;6:311–317. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N, Monyer H, Seeburg P H, Sakmann B. Divalent ion permeability of AMPA receptor channels is dominated by the edited form of a single subunit. Neuron. 1992;8:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N, Sakmann B. RNA editing makes homomeric GluR6 subunit channels permeable to anions without altering the apparent size of the pore. Biophysical Journal. 1996;60:A78. [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N, Villarroel A, Sakmann B. Dimensions and ion selectivity of recombinant AMPA and kainate receptor channels and their dependence on Q/R site residues. Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:165–173. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N, Zhou Z, Neher E, Sakmann B. Fractional calcium currents through recombinant GluR channels of the NMDA, AMPA and kainate receptor subtypes. Journal of Physiology. 1995;485:403–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes K M, Fuller T A, Price J L. Sources of presumptive glutamatergic/aspartatergic afferents to the magnocellular basal forebrain in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;302:824–852. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D W. Calcium: still center-stage in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donevan S D, Rogawski M A. GYKI 52466, a 2,3-benzodiazepine, is a highly selective, noncompetitive antagonist of AMPA/kainate receptor responses. Neuron. 1993;10:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90241-i. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90241-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett S B, Everitt B J, Robbins T W. The basal forebrain-cortical cholinergic system: interpreting the functional consequences of excitotoxic lesions. Trends in Neurosciences. 1991;14:494–501. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90061-x. 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhäuser B. Sodium permeability in toad nerve and in squid nerve. Journal of Physiology. 1960;152:159–166. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger J R P, Melcher T, Koh D-S, Sakmann B, Seeburg P H, Jonas P, Monyer H. Relative abundance of subunit mRNAs determines gating and Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors in principal neurons and interneurons in rat CNS. Neuron. 1995;15:193–204. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90076-4. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green W N, Anderson O S. Surface charges and ion channel function. Annual Review of Physiology. 1991;53:341–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002013. 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Huang L-YM. Block of kainate receptor channels by Ca2+ in isolated spinal trigeminal neurons of rat. Neuron. 1991;6:777–784. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90174-x. 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90174-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner J E. Glutamate receptor channels in rat DRG neurons: activation by kainate and quisqualate and blockade of desensitization by Con A. Neuron. 1990;5:255–266. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90163-a. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90163-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M, Ozawa S, Tsuzuki K. Permeation of calcium through excitatory amino acid receptor channels in cultured rat hippocampal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1990;424:151–165. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen T H, Chaudhary A, Verdoorn T A. Interactions among GYKI-52466, cyclothiazide, and aniracetam at recombinant AMPA and kainate receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 1995;48:946–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj S K, Swanson G T, Cull-Candy S G. Intracellular spermine confers rectification on rat calcium-permeable AMPA and kainate receptors. Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:297–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto E, Murata Y. Excitatory amino acid-induced currents in rat septal cholinergic neurons in culture. Neuroscience. 1995;69:477–493. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00260-p. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00260-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T, Rand M N, Waxman S G, Kocsis J D. Differential role of two Ca2+-permeable non-NMDA glutamate channels in rat retinal ganglion cells: kainate-induced cytoplasmic and nuclear Ca2+ signals. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:2503–2516. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C A. Ion-concentration dependence of the reversal potential and the single channel conductance of ion channels at the frog neuromuscular junction. Journal of Physiology. 1979;286:417–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M P, Barger S W, Cheng B, Lieberburg I, Smith-Swintosky V L, Rydel R E. β-Amyloid precursor protein metabolites and loss of neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis in Alzheimer's disease. Trends in Neurosciences. 1993;16:409–414. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90009-b. 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90009-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M P, Cheng B, Davis D, Bryant K, Lieberburg I, Rydel R E. β-Amyloid peptides destabilize calcium homeostasis and render human cortical neurons vulnerable to excitotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:376–389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M L, Vyklicky L, Westbrook G L. Modulation of excitatory amino acid receptors by group IIB metal cations in cultured mouse hippocampal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1989;415:329–350. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M L, Westbrook G L. Permeation and block of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor channels by divalent cations in mouse cultured central neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1987;394:501–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M-M. The cholinergic contribution to neuromodulation in the cerebral cortex. Seminars in the Neurosciences. 1995;7:297–307. 10.1006/smns.1995.0033. [Google Scholar]

- Otis T S, Raman I M, Trussell L O. AMPA receptors with high Ca2+ permeability mediate synaptic transmission in the avian auditory pathway. Journal of Physiology. 1995;482:309–315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page K J, Everitt B J. The distribution of neurons coexpressing immunoreactivity to AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor subtypes (GluR1–4) and nerve growth factor receptor in the rat basal forebrain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;7:1022–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page K J, Sirinathsinghji D J S, Everitt B J. AMPA-induced lesions of the basal forebrain differentially affect cholinergic and non-cholinergic neurons: lesion assessment using quantitative in situ hybridization histochemistry. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;7:1012–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partin K M, Patneau D K, Winters C A, Mayer M L, Buonanno A. Selective modulation of desensitization at AMPA versus kainate receptors by cyclothiazide and concanavalin A. Neuron. 1993;11:1069–1082. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90220-l. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90220-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternain A V, Morales M, Lerma J. Selective antagonism of AMPA receptors unmasks kainate receptor-mediated responses in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90253-8. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry E K, Tomlinson B E, Blessed G, Bergmann K, Gibson P H, Perry R H. Correlation of cholinergic abnormalities with senile plaques and mental test scores in senile dementia. British Medical Journal. 1978;2:1457–1459. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6150.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piek T. Ionic and electrical properties. In: Usherwood E N R, editor. Insect Muscle. London, New York and San Francisco: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 281–336. [Google Scholar]

- Pitzer K S, Mayorga G. Thermodynamics of electrolytes II. Activity and osmotic coefficients for strong electrolytes with one or both ions univalent. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1973;77:2300–2307. [Google Scholar]

- Rörig B, Grantyn R. Rat retinal ganglion cells express Ca2+-permeable non-NMDA glutamate receptors during the period of histogenetic cell death. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;153:32–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90070-2. 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather W, Dieudonné S, MacDonald J F, Ascher P. Activation and desensitization of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in nucleated outside-out patches from mouse neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:643–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R. Simultaneous measurement of Ca2+ influx and reversal potentials in recombinant N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channels. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2165–2174. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79782-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Tempia F, Konnerth A. Glutamate- and AMPA-mediated calcium influx through glutamate receptor channels in medial septal neurons. Neuropharmacology. 1993a;32:1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90016-v. 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90016-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Zhou Z, Konnerth A, Neher E. Fractional contribution of calcium to the cation current through glutamate receptor channels. Neuron. 1993b;11:133–143. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90277-x. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki T, Harata N, Akaike N. Metabotropic glutamate responses in acutely dissociated hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurones of the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1994;475:439–453. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler S. Expansion of the constant field equation to include both divalent and monovalent ions. Alabama Journal of Medical Sciences. 1975;2:218–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters D J. Expression of a kainate-type glutamate receptor by rat basal forebrain neurones in dissociated culture. Journal of Physiology. 1996;495.P:45P. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse P J, Price D, Struble R G, Clark A W, Coyle J T, DeLong M R. Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science. 1982;215:1237–1239. doi: 10.1126/science.7058341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong L A, Mayer M L. Differential modulation by cyclothiazide and concanavalin A of desensitization at native α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid and kainate-preferring glutamate receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 1993;44:504–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankner B A. Mechanisms of neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1996;16:921–932. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80115-4. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H-Z, Lindsay A D, Weiss J H. Kainate injury to cultured basal forebrain cholinergic neurons is Ca2+ dependent. NeuroReport. 1994;5:1477–1480. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199407000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]