Abstract

The relationship between phosphorylation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride channel and its gating by nucleotides was examined using the patch clamp technique by comparing strongly phosphorylated wild-type (WT) channels with weakly phosphorylated mutant channels lacking four (4SA) or all ten (10SA) dibasic consensus sequences for phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA).

The open probability (Po) of strongly phosphorylated WT channels in excised patches was about twice that of 4SA and 10SA channels, after correcting for the number of functional channels per patch by addition of adenylylimidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP). The mean burst durations of WT and mutant channels were similar, and therefore the elevated Po of WT was due to its higher bursting rate.

The ATP dependence of the 10SA mutant was shifted to higher nucleotide concentrations compared with WT channels. The relationship between Po and [ATP] was noticeably sigmoid for 10SA channels (Hill coefficient, 1.8), consistent with positive co-operativity between two sites. Increasing ATP concentration to 10 mM caused the Po of both WT and 10SA channels to decline.

Wild-type and mutant CFTR channels became locked in open bursts when exposed to mixtures of ATP and the non-hydrolysable analogue AMP-PNP. The rate at which the low phosphorylation mutants became locked open was about half that of WT channels, consistent with Po being the principal determinant of locking rate in WT and mutant channels.

We conclude that phosphorylation at ‘weak’ PKA sites is sufficient to sustain the interactions between the ATP binding domains that mediate locking by AMP-PNP. Phosphorylation of the strong dibasic PKA sites controls the bursting rate and Po of WT channels by increasing the apparent affinity of CFTR for ATP.

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a low-conductance chloride channel expressed in epithelial, cardiac and other cells (see Gadsby, Nagel & Hwang, 1995; Hanrahan et al. 1995 for reviews). Its activity is increased by hormones and agonists that raise cAMP, through a mechanism involving protein kinase A (PKA)-catalysed phosphorylation at multiple sites (Cheng, Rich, Marshall, Gregory, Welsh & Smith, 1991; Tabcharani, Chang, Riordan & Hanrahan, 1991; Picciotto, Cohn, Bertuzzi, Greengard & Nairn, 1992; Berger, Travis & Welsh, 1993; Chang et al. 1993; Hwang, Nagel, Nairn & Gadsby, 1994).

A conspicuous feature of the amino acid sequence of CFTR is the presence of ten strong dibasic PKA consensus sequences (R, R/K, X, S/T) and numerous monobasic (R, X2, S/T and R, X, S/T) sequences (where X represents a polar amino acid; Kennelly & Krebs, 1991). In vivo phosphorylation of full-length CFTR has been demonstrated at five of these (serines 660, 737, 795, 813, Cheng et al. 1991; serine 700, Picciotto et al. 1992) whereas in vitro exposure of full length CFTR or recombinant peptides containing the R domain leads to phosphorylation of six to eight sites (Picciotto et al. 1992; Townsend, Lipniunas, Tulk & Verkman, 1996). Although PKA is undoubtedly the main physiological activator of CFTR, phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC) and perhaps other kinases also modulate its activity (Tabcharani et al. 1991). Forskolin-induced 32PO4 labelling of CFTR is enhanced in vivo when cells are briefly pre-treated with phorbol ester to activate PKC (Chang et al. 1993). Indeed, it has recently been shown that constitutive phosphorylation by PKC is required for acute activation of CFTR by PKA in both cell-attached and excised membrane patches (Jia, Mathews & Hanrahan, 1997). Despite considerable progress, the mechanism by which phosphorylation increases open probability (Po) remains obscure.

Once CFTR is phosphorylated, opening and closing transitions require ATP hydrolysis (Anderson, Berger, Rich, Gregory, Smith & Welsh, 1991; Baukrowitz, Hwang, Nairn & Gadsby, 1994; Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Li et al. 1996). The channel becomes ‘locked’ in an open burst state when exposed to solutions containing both ATP and the non-hydrolysable analogue, adenylylimidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP; Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Hwang et al. 1994). This locked-open state is believed to result from stabilizing interactions between the two nucleotide binding folds (NBFs). Similar interactions may occur when ATP binds at NBF2 during normal gating, although the channels do not become permanently locked in this case because the ATP can be hydrolysed (Gadsby et al. 1995). By analogy with other ATP- and particularly GTP-binding proteins (Carson & Welsh, 1995; Manavalan, Dearborn, McPherson & Smith, 1995; Randak et al. 1996), such interactions between domains may control release of the hydrolysis products from the other NBF (Baukrowitz et al. 1994; Carson, Travis & Welsh, 1995; Carson & Welsh, 1995). Phosphorylation of the R domain could potentially stimulate ATP hydrolysis at NBF1 in a manner analogous to GTPase activating proteins (GAPs; Scheffzek, Lautwein, Kabsch, Ahmadian & Wittinghofer, 1996) or, like a GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI; Sasaki et al. 1990), catalyse the inhibitory action of NBF2 on ADP and phosphate release from NBF1.

In this paper we study the effects of phosphorylation on nucleotide-dependent gating. It is difficult to manipulate steady-state levels of phosphorylation using only kinases and phosphatases; therefore we have compared fully phosphorylated, wild-type CFTR with mutated channels lacking four or all ten dibasic PKA sites (Chang et al. 1993). We have shown that mutants lacking multiple PKA sites are processed normally and targeted to the plasma membrane like WT CFTR (Chang et al. 1993). Anion permeability in these mutants is indistinguishable from WT CFTR. They also exhibit normal (permissive) regulation by PKC and, like WT, CFTR are strongly activated by the tyrosine kinase p60c-Src in the absence of PKA (Jia, Seibert, Chang, Riordan & Hanrahan, 1997). We conclude that these mutants are fully functional except for the loss of PKA responsiveness, and are therefore useful for studies of PKA regulation.

Mutants lacking dibasic PKA sites had normal open burst durations and prolonged interbursts; there was no destabilization of the open state associated with reduced phosphorylation. However the decrease in bursting rate was associated with a marked reduction in ATP sensitivity. The results suggest that phosphorylation may elevate Po by increasing the apparent affinity of CFTR for ATP, thereby increasing the rate at which it enters open bursts. Weakly phosphorylated mutant channels were locked open by AMP-PNP at about half the rate of WT channels and paralleled the decline in Po, consistent with AMP-PNP binding only when the channel is in the open state. These results have appeared in preliminary form (Mathews, Tabcharani, Chang, Riordan & Hanrahan, 1995; Mathews, Tabcharani, Chang, Riordan & Hanrahan, 1996).

METHODS

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing CFTR were plated at a density of ∼500 000 cm−2 on glass coverslips and used in patch clamp experiments 3-5 days later. CHO cell lines expressing (i) wild-type (WT) CFTR, (ii) 4SA (serine residues at positions 660, 737, 795 and 813 mutated to alanines), and (iii) 10SA (serine residues at 422, 660, 686, 700, 712, 737, 768, 795 and 813 and threonine 788 mutated to alanines; see Fig. 1A and Chang et al. 1993 for details of the mutagenesis) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 8% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1) and methotrexate (100 μM) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Media constituents were from Gibco (Burlington, Ontario, Canada).

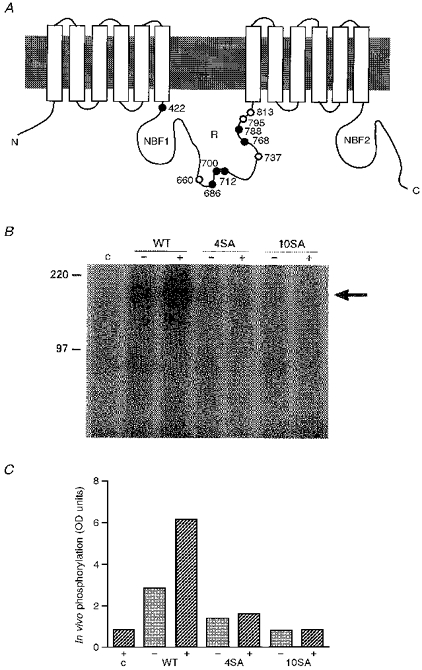

Figure 1. Effect of eliminating dibasic PKA consensus sequences on in vivo phosphorylation.

A, cartoon showing the locations of dibasic consensus PKA sites altered in the phosphorylation-deficient channels; open circles, 4SA; all circles, 10SA. B, each of the three cell lines (WT, 4SA and 10SA) were grown on 60 mm dishes. Following washes with phosphate-free medium, cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in 1.0 ml of the same medium containing 300 μCi [32P]orthophosphate (see Methods for details). Agonists were added to plates marked (+) at 15 min before the end of the 4 h labelling period. Vehicle alone (dimethylsulphoxide) was added to the cell controls marked (-). Proteins were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal antibody (M3A7) and analysed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the 7% polyacrylamide gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film for 14 h at -80 °C. Lane c indicates host CHO cells not expressing CFTR. Values to the left are in kDa. C, graph of densitometry readings for the autoradiograph shown in B. (-) indicates WT and mutant cells which were exposed to vehicle alone, and (+) indicates cells in which PKA levels were increased by the addition of agonists (10 μM forskolin, 200 μM dibutyryl-cAMP and 1 mM IBMX).

Methods used to compare in vivo phosphorylation of WT, 4SA and 10SA were those used previously (Chang et al. 1993). Briefly, CHO cell lines expressing each construct were grown to 90% confluence in 60 mm plastic culture dishes, washed twice with phosphate-free minimum essential medium (αMEM) containing 8% (v/v) dialysed fetal bovine serum and 50 μM Na3VO4. Labelling was carried out by incubating cells for 4 h at 37°C in 1.0 ml of the same medium containing 300 μCi [32P]orthophosphate (Amersham, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 13A). Cells were stimulated by adding 10 μM forskolin, 200 μM dibutyryl-cAMP and 1 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) (in a dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) stock solution) to the experimental plates 15 min before the end of the 4 h labelling period. Control plates received vehicle alone. After washing with cold PBS, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (1% v/v Triton X-100, 1% w/v deoxycholic acid, 0.1% w/v sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 10 mM iodoacetamide, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 2 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 2 μg ml−1 aprotinin). Phosphorylated CFTR was immunoprecipitated using the monoclonal antibody M3A7 (1 μg), which recognizes an epitope in the carboxy terminus (Kartner, Augustinas, Jensen, Naismith & Riordan, 1992). Following overnight incubation in a shaker at 4°C, 10 μl of protein G-sepharose 4B beads (Sigma) were added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with shaking. The beads were recovered by centrifugation and bound proteins were solubilized in 50 μl 2 × sample buffer prior to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Chang et al. 1993). After electrophoresis, the 7% polyacrylamide gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film. Densitometry of the phosphorylated CFTR bands on the autoradiogram was then performed.

Cells were placed in a recording chamber containing standard buffer (mM): 150 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 Tes, pH adjusted to 7.4 with 1 N NaOH. The catalytic subunit of PKA (180 nM; from the laboratory of Dr M. P. Walsh, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada; see Tabcharani et al. 1991) and MgATP (1 mM) were both present in the bath unless otherwise indicated. MgATP was added from 100 mM stock solution in standard recording buffer at pH 7.4. To study the rate of locking and estimate the number of functional channels in patches, the non-hydrolysable nucleotide adenylyl-imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP; tetralithium salt) was added to the bath from a 100 mM stock solution (in standard recording buffer) to yield a final concentration of 1 mM. When the ATP dependence of the open probability (Po) of CFTR channels was determined, standard recording solution containing 2 mM MgCl2 was used in the bath and MgATP was added from a 100 mM stock solution, to give final MgATP concentrations of 33 μM to 10 mM. All chemicals were from Sigma.

Pipettes were prepared using a conventional puller (PP-83, Narishige Instrument Laboratory, Tokyo) and had resistances of 4-6 MΩ when filled with 154 mM Cl− solution. The bath solution was earthed through an agar bridge having the same ionic composition as the pipette solution. All patches were studied using the inside-out configuration with the pipette potential clamped at +30 mV (i.e. membrane potential Vm= -30 mV). Single-channel currents were amplified (Axopatch 1C, Axon Instruments), recorded on videocassette tape by a pulse-coded modulation-type recording adapter (DR384, Neuro Data Instruments Corp., NY, USA) and low-pass filtered during playback using an 8-pole Bessel-type filter (900 LPF, Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA). The recording bandwidth (-3 dB) was 230 Hz. Multichannel records were sampled at 1 kHz and analysed using a microcomputer as described previously (Hanrahan & Tabcharani, 1990; Tabcharani et al. 1991). Conventional threshold crossing analysis was performed using pCLAMP acquisition and analysis (version 6.0.3, Axon Instruments), following digitization at 800 Hz and filtering at 150 Hz (-3 dB). The rise time (Tr) of the low-pass Bessel filter was approximately 2.2 ms (0.33/fc, where fc is the -3 dB corner frequency of the filter; see Colquhoun & Sigworth, 1995). The minimum pulse duration that would reach a threshold set at 50% of the pulse amplitude (the dead time; Td) was approximately 1.2 ms as determined by applying voltage pulses of varying duration to excised patches. Although the durations of brief events (circa 1 ms) would be underestimated under these conditions, they were nonetheless excluded from our analysis of bursts, which typically lasted hundreds of milliseconds. Most patches contained several channels (averaging 6 channels per patch), precluding routine use of the threshold crossing method for estimating open and closed times. To evaluate kinetics in multi-channel patches, the mean number of channels open was determined by measuring the fraction of time spent at each multiple of the unitary current. The single-channel open probability (Po) was calculated according to the relationship:

| (1) |

where ti is the time spent above a threshold i set at 0.5, 1.5, 2.5,… times the single-channel current amplitude, N is the number of channels locked open at the end of the experiment using AMP-PNP, and T is the duration of the segment (> 120 s). The total length of an experiment was approximately 15 min; see below. The number of opening transitions during each segment was counted and used to estimate the mean burst (τopen) and interburst (τclosed) durations by the cycle time method (Gray, Greenwell & Argent, 1988) according to:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where N is the number of channels locked open by AMP-PNP (see below) and T is the duration of the segment (> 120 s).

This method for calculating mean burst duration assumes that the channel cycles between one open and one closed state. CFTR has at least two closed states (interburst closures and flickery closures within bursts; e.g. Haws, Krouse, Xia, Gruenert & Wine, 1992; Fischer & Machen, 1994); however, we found that brief closures within bursts had little impact on Po and were not dependent on nucleotide concentration, and therefore they were omitted from the analysis. After excluding flickery closures within bursts (see below and Fig. 3), CFTR kinetics were well described by a single population of long openings (bursts) and closings (interbursts). Evidence supporting the validity of this method when applied to 10SA channels, as for wild-type CFTR channels (Gray et al. 1988; Dalemans et al. 1991), is given in the Results section.

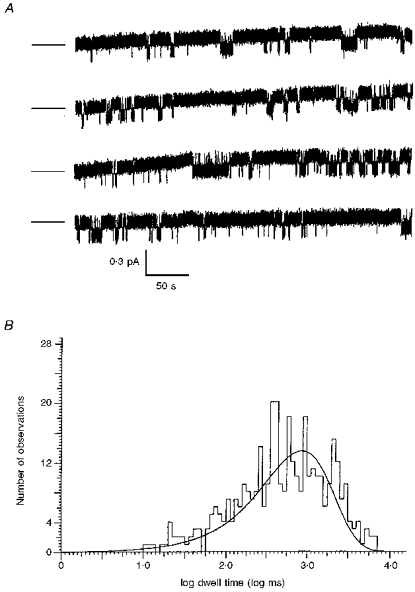

Figure 3. Validation of the method used to calculate kinetics with multichannel patches.

A, continuous 32 min recording from one 10SA channel. B, histogram of burst durations for the data shown in A computed using the threshold crossing method after excluding flickery closures (< 9.2 ms). The mean burst duration was 864 ms according to this method and 900 ms when calculated using eqn (2); see Methods for details.

An estimate of the number of functional channels (N) is also required when using the above method to calculate Po and mean interburst duration for multi-channel patches (eqns (1) and (3)). AMP-PNP, which locks functional CFTR open in the presence of ATP, was added at the end of each experiment. This generated a staircase-like increase in patch current that eventually reached a plateau (see Fig. 6). The value of N obtained by counting the steps always equalled or exceeded the maximum number of channels that opened simultaneously during long recordings. The rate of locking was calculated from the distribution of latencies (in seconds) between the addition of AMP-PNP and the time at which individual channels become locked open. Channels were defined as being locked open when they remained in the open burst state for the duration of the experiment without being interrupted by closures lasting more than 500 ms, and channels were not considered locked unless they satisfied this criterion for at least 1 min. The number of latency values obtained from each experiment varied between two and ten because most patches contained multiple channels. The total number of WT and mutant channels analysed are shown in the legend to Fig. 7. Studies were carried out at room temperature (∼22°C).

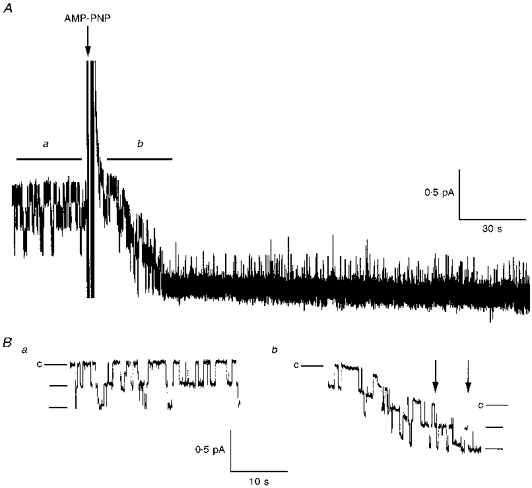

Figure 6. Channel locking after addition of AMP-PNP.

A, representative trace showing activity of WT CFTR channels in a patch excised into a recording chamber containing standard buffer, 180 nM PKA and 1 mM MgATP. AMP-PNP (1 mM) was added as indicated and channels were progressively locked in the open state. B, expanded traces of data shown in A before (a), and immediately after (b) addition of AMP-PNP. Some baseline drift was usually observed following addition of AMP-PNP, as indicated in b by the lines to the left and right of the trace. The times at which channels became locked open are indicated by arrows. Expanded traces have been fast Fourier transform (FFT) filtered at 50 Hz (using Microcal Origin 4.1) for presentation purposes.

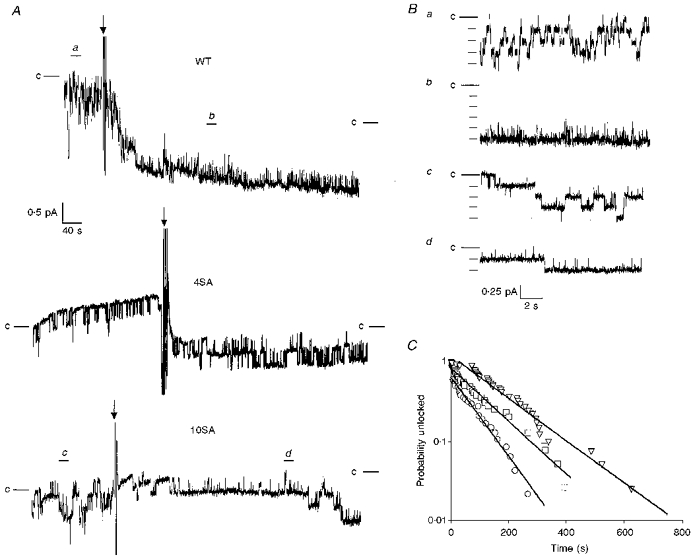

Figure 7. Comparison of locking rates for wild-type and mutant CFTR channels.

A, traces obtained from excised, inside-out patches from cells expressing WT, 4SA or 10SA channels showing the locking open induced by AMP-PNP. PKA (180 nM) and MgATP (1 mM) were present throughout and AMP-PNP (1 mM) was added at the arrows. The segments indicated by a, b, c and d are shown on expanded scale in panel B. Zero current levels are indicated by lines alongside the traces. C, rates of locking were calculated by determining the latency between addition of AMP-PNP and the locking of wild-type (○, n = 47 channels, 6 patches), 4SA (□, n = 38 channels, 8 patches), or 10SA channels (▿, n = 40 channels, 10 patches).

RESULTS

Comparison of in vivo phosphorylation of wild-type and mutant CFTR protein

Figure 1A illustrates the dibasic PKA consensus sequences on CFTR and identifies the ones altered in the 4SA and 10SA mutants (see Chang et al. 1993 for details). Stable CHO cell lines expressing similar levels of WT, 4SA or 10SA protein were used for patch-clamp experiments. In vivo phosphorylation was compared as described in Methods. Figure 1B shows the autoradiographs of radiolabelled phosphate incorporated into wild-type, 4SA and 10SA protein after in vivo phosphorylation. Figure 1C shows the results of densitometry of the autoradiographs. Most phosphorylation during cAMP stimulation was eliminated by mutation of four sites on the R domain (4SA), but some labelling (∼2% of maximally phosphorylated WT CFTR) was still detectable when all ten dibasic PKA consensus sequences were altered (see Seibert et al. 1995). This low percentage presumably represents the average phosphorylation when low-affinity PKA phosphorylation sites are labelled on a subpopulation of CFTR molecules. Only phosphorylated channels are detected electrophysiologically, and therefore the Po measured during patch-clamp experiments is for that subpopulation which is labelled. Hence the lower Po of mutants may result from less efficacious activation by the sites that remain, and is not expected to be strictly proportional to the number of moles of PO4 per mole of total protein.

Mechanism by which the Po of phosphorylation site mutants is reduced

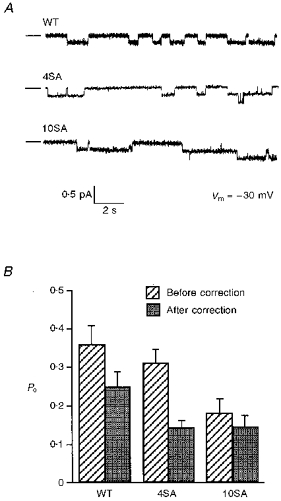

Figure 2A shows traces of WT, 4SA and 10SA channels under standard conditions (1 mM MgATP, 180 nM PKA). Po was calculated by dividing the mean number of channels in the open state (NPo) by the number of functional channels in the patch (N; determined by adding AMP-PNP at the end of each experiment and counting the number of steps in the staircase-like increase in patch current) as described in Methods. Estimating N in each patch using AMP-PNP caused our estimates of Po to be somewhat lower than in previous studies (Tabcharani et al. 1991; Chang et al. 1993). The Po of WT channels was reduced from 0.353 ± 0.05 to 0.244 ± 0.04 (n = 6), while for 4SA, Po decreased from 0.307 ± 0.04 to 0.138 ± 0.02 (n = 8). The Po of 10SA decreased from 0.177 ± 0.04 to 0.142 ± 0.03 (n = 8). Thus after correcting N, 4SA and 10SA channels had similar Po values, which were about half that of WT CFTR (Fig. 2b; P < 0.01).

Figure 2. Single-channel activity of WT and mutant CFTR.

A, recordings obtained using inside-out patches excised from cells expressing wild-type (WT) or mutant 4SA or 10SA channels. The bath contained 1 mM MgATP and 180 nM PKA catalytic subunit. In this and subsequent figures the closed channel current level is indicated by lines to the left of traces and channel openings are downwards. B, open probability estimated for WT and mutant channels before and after correcting N by locking channels open with 1 mM AMP-PNP. n = 6 patches for WT and 8 patches for each mutant.

To examine if the twofold higher Po of WT channels results from stabilization of the open burst state, we compared the kinetics of WT and mutant channels under standard conditions of 180 nM PKA and 1 mM MgATP. To validate the method used for calculating kinetics when patches contained more than one mutant channel, we compared the results obtained when single-channel records were analysed with both ‘cycle time’ and conventional threshold crossing methods. Figure 3A shows a long recording of a single 10SA channel (> 30 min) which was analysed using both methods. Burst duration was calculated to be 900 ms by the first method (using eqn (2) in Methods). A threshold was then set at one-half the open channel amplitude and the distribution of open bursts was obtained for the same recording by excluding closures within bursts that were shorter than 9.2 ms. Excluding flickery closures (mean apparent duration, 0.92 ms) had little effect on estimates of the Po under these conditions (0.203 vs. 0.197 when intraburst closures were included). The histogram of open-burst durations (on a log scale with 20 bins decade−1; minimum bin value 1 ms) shown in Fig. 3B was well fitted, using Simplex least squares fitting, by a single exponential having a time constant of 864 ms, in close agreement with the mean open-burst duration of 900 ms obtained previously. These results suggest that the ‘cycle time’ method can be used for estimating the mean burst duration of 10SA channels when they are studied in multi-channel patches.

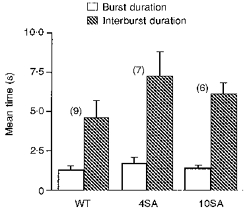

Mean burst durations of WT, 4SA and 10SA channels were closely similar (1.3 ± 0.3, 1.7 ± 0.4 and 1.4 ± 0.2 s, respectively) and therefore the reduction in Po caused by removal of the ten dibasic consensus sites was not associated with altered stability of the open burst state (Fig. 4). If open burst duration depends on interactions between the NBFs as proposed (Hwang et al. 1994), phosphorylation at sites other than the ten obvious ones must be sufficient to fully stabilize those interactions. Interburst durations are less well determined by this method due to the existence of multiple closed states; nevertheless, the low Po of 4SA and 10SA channels was associated with prolonged intervals between bursts (Fig. 4). These results suggest that phosphorylation of four or all ten dibasic sites increases open probability by increasing the bursting rate.

Figure 4. Reduced Po of mutant channels results from altered interburst durations.

Mean burst and interburst durations calculated for WT and phosphorylation-deficient mutant channels (4SA, 10SA).

Dibasic PKA sites increase Po by modulating the ATP dependence of CFTR

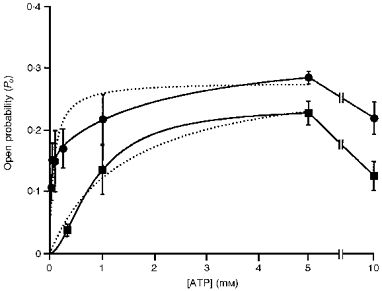

Since gating requires nucleotide binding and hydrolysis, we examined whether phosphorylation at the ten strong PKA sites enhances channel opening rate by altering its nucleotide dependence. The dependencies of Po and burst kinetics on ATP concentration were compared for WT and 10SA channels. The number of channels in each patch was determined by locking them open at the end of each experiment using AMP-PNP. As shown in Fig. 5, the Po of WT channels was a steep function of ATP concentration, with Po increasing at high [ATP] due to a decrease in interburst duration (not shown) in agreement with previous studies (Venglarik, Schultz, Frizzell & Bridges, 1994; Winter, Sheppard, Carson & Welsh, 1994; Li et al. 1996). The relationship between ATP concentration (0-5 mM) and Po was poorly fitted by a single Michaelis-Menten function (KM= 73 μM; correlation coefficient, r2= 0.9056; see dotted line in Fig. 5), but pooled data were well fitted by a Michaelis-Menten function having two KM values (14 ± 3 μM and 2.3 ± 0.4 mM; r2= 0.989; Fig. 5). The relationship was less well fitted by the sigmoidal Hill equation (r2= 0.9645; n = 0.43), possibly due to insufficient data at low ATP concentrations. In contrast, Fig. 5 shows that the ATP dependence of 10SA channels was shifted to much higher ATP concentrations when compared with WT channels (KM= 1.4 mM; r2= 0.985; 19.2-fold higher than the value for a single KM fit of WT data, and 100-fold higher than the dominant KM when WT data were fitted with two Michaelis-Menten functions). For 10SA channels, fitting the sigmoid ATP dependence of Po yielded a Hill coefficient of n = 1.76 (r2= 0.999), consistent with ATP binding at two or more sites that interact co-operatively. At low concentrations of ATP, changes in Po are mainly due to altered interburst duration, and therefore the EC50 calculated from Po reflects an effect on channel opening. Interestingly, when the ATP concentration was increased further to 10 mM, the Po of both WT and 10SA CFTR channels was reduced and this decrease was associated with an elevation of the closing rate, at least for 10SA channels (data not shown). This result has several possible explanations, but is consistent with ATP interacting at two sites which have different ATP affinities and opposing effects on channel gating.

Figure 5. Relationship between ATP concentration and Po for WT and 10SA mutant channels.

Dotted lines show Michaelis-Menten fits to data pooled from 3-9 patches at each concentration between 0 and 5 mM MgATP. WT data were best fitted by an expression containing two KM (•; continuous line), while 10SA data were best fitted by the Hill equation (▪; continuous line). The values of Po determined with 10 mM MgATP present are also shown but were not used for fitting. All Po values were corrected for the maximum number of channels in each patch during exposure to 1 mM AMP-PNP. The number of experiments at each ATP concentration was 3-9 for WT, and 3-7 for 10SA. The bath contained PKA (180 nM) and 2 mM MgCl2 throughout each experiment, and MgATP was added from a 100 mM stock solution.

Locking and unlocking of wild-type and mutant CFTR channels

CFTR can be locked in open bursts by exposure to non-hydrolysable analogues of ATP in the presence of ATP (Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Hwang et al. 1994). This behaviour is illustrated in Fig. 6 for CFTR channels expressed in CHO cells and studied in excised patches in the presence of PKA (180 nM) and MgATP (1 mM). To study the dependence of locking on phosphorylation at dibasic PKA sites, we compared the effect of 1 mM AMP-PNP on WT, 4SA and 10SA channels (Fig. 7). Figure 7A shows continuous recordings of all three channel types in the presence of 1 mM MgATP and 180 nM PKA catalytic subunit. AMP-PNP caused channel locking in every patch after time intervals ranging from a few seconds to several minutes. Expanded traces from wild-type and 10SA channels are shown in Fig. 7B, before and after, the addition of AMP-PNP. When the time intervals between AMP-PNP addition and locking were ranked in descending order, plotted against rank order using an exponential scale, and fitted by linear regression, it became apparent that the low-phosphorylation mutants were locked at about half the rate of wild-type channels (Fig. 7C). The exponential time constants for locking obtained by least squares yielded rates of 0.0115 s−1 (WT), 0.0077 s−1 (4SA), and 0.0061 s−1 (10SA). It has been proposed that CFTR can only be locked when open (Hwang et al. 1994). Under these conditions the true on-rate for AMP-PNP is determined by the cumulative open time between the addition of AMP-PNP and channel locking, rather than total time. To estimate the on-rate, we multiplied the latencies measured for locking of individual WT and mutant channels by their Po. When placed in descending order and plotted against rank order, least squares exponential fits of these distributions yielded estimates of the apparent AMP-PNP on-rate of 0.0471 s−1 (WT), 0.0434 s−1 (4SA), and 0.0188 s−1 (10SA). The on-rates for WT and 4SA channels were very similar suggesting that phosphorylation affects AMP-PNP binding only indirectly through its effects on Po. The lower on-rate calculated for 10SA channels is possibly caused by a decrease in channel Po following the addition of AMP-PNP (see Fig. 7A). The reason for this decrease in Po is unknown and was not seen for WT or 4SA channels (see Figs 6 and 7A). Once channels became locked in the open burst state by AMP-PNP they invariably remained locked for the duration of the experiment (typically > 15 min), indicating a very slow off-rate which is not strongly influenced by phosphorylation at four or all ten dibasic PKA sites.

DISCUSSION

This paper examines the relationship between CFTR phosphorylation and its gating by nucleotides. The results indicate that phosphorylation at the strong (dibasic) PKA consensus sequences causes a doubling of open probability by increasing the bursting rate without altering burst duration. Associated with the increased bursting rate is a large (> 20-fold) enhancement of the apparent affinity for ATP, but there is only a modest (2-fold) increase in the locking rate, possibly accounted for by the elevation of open probability. The on-rate for AMP-PNP is unchanged by the removal of four dibasic PKA consensus sequences. This implies that affinity of the ATP site that controls channel opening may be increased preferentially by phosphorylation at one or more of the dibasic consensus sequences, while ATP (or AMP-PNP) binding that regulates closing is unaffected. Parallel changes in Po and locking suggests that AMP-PNP can only bind when the channel is already in the open conformation. This finding explains why CFTR channels are not locked in the closed state by AMP-PNP and is consistent with predictions of existing models (Hwang et al. 1994).

Dibasic PKA sites modulate ATP dependence (apparent KM)

Incremental phosphorylation of dibasic PKA sites increases the sensitivity of CFTR to nucleotides and enhances the bursting rate when channels are bathed with the submaximal concentration of 1 mM ATP. These effects may be causally related since the increase in opening rate is comparable with that caused by elevating ATP concentration (Venglarik et al. 1994; Winter et al. 1994; Li et al. 1996), and increasing nucleotide affinity and ATP concentration are expected to have equivalent effects. Other conditions that influence bursting include the presence of inorganic phosphate, which stimulates CFTR channel activity by increasing the bursting rate (Carson, Travis, Winter, Sheppard & Welsh, 1994), and ADP, which decreases this rate (Winter et al. 1994) without affecting mean burst duration (Gunderson & Kopito, 1994).

The ATP dependence of WT channels was best fitted by an equation containing two Michealis-Menten functions. The low KM (14 ± 3 μM ATP) agrees reasonably well with one reported for CFTR channels expressed in mouse L-cells (24 ± 8 μM; Venglarik et al. 1994), but is lower than in most other studies (e.g. 111 μM; Gunderson & Kopito, 1994). The possibility that the high KM (2.3 mM ATP) represents nucleotide interactions at a second site (e.g. NBF2) is appealing but remains speculative. We cannot exclude the possibility that high concentrations of ATP have some indirect stimulatory effect on Po. For example, ATP may inhibit membrane-associated phosphatase activity (Tabcharani et al. 1991; Becq et al. 1994), thereby introducing a second plateau at high ATP concentrations. In this case the single KM of 73 μM may be more accurate. The reason for the decline in burst duration at very high ATP concentrations (> 5 mM; Fig. 5) is unknown. Further experiments are, however, needed since the ATP dependencies of bursting and closing rates were similar when purified CFTR channels were reconstituted into planar bilayers (Li et al. 1996). Regardless of the actions of high ATP concentrations, the results strongly suggest that differences in Po between wild-type and 10SA channels under standard conditions of 1 mM MgATP are due, at least in part, to their different ATP dependencies. Since all these experiments were performed on excised patches in the presence of saturating concentrations of PKA catalytic subunit and the same membrane-associated endogenous phosphatases are present in cells expressing WT and mutant channels, phosphatases are unlikely to have played a significant role in the differences observed between WT channels and those lacking dibasic consensus sites.

Phosphorylation at weak PKA consensus sites is sufficient for locking by AMP-PNP

To explain why AMP-PNP locks CFTR in open bursts, a scheme has been proposed in which ATP is hydrolysed at one NBF (probably NBF1) to cause the channel to open, and binding of a second nucleotide inhibits ADP and inorganic phosphate release, thereby prolonging the burst until the second nucleotide is hydrolysed (Gadsby et al. 1995). Previous studies using ATPase inhibitors and mutant channels have provided data consistent with this model (Baukrowitz et al. 1994; Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Carson et al. 1995), but the precise role of phosphorylation remains poorly understood. The sites that enable these stabilizing interactions between the NBFs were not previously identified, but the ten strong consensus sequences were obvious candidates.

In the present study we found that AMP-PNP can still induce locking of the 4SA mutant and the 10SA mutant, which lack all the dibasic PKA sites. Both these mutants have greatly reduced phosphorylation. However, since wild-type CFTR reaches a stoichiometry of only ∼5 mol PO4 mol−1 CFTR when phosphorylated in vitro (unpublished observation reported in Picciotto et al. (1992)), and a single phosphoryl group is the lowest number capable of activating one CFTR, any channel observed during patch clamp experiments must have at least 20% of the (average) phosphorylation on wild-type CFTR. We interpret the lower values estimated by densitometry to mean that the proportion of CFTR molecules phosphorylated is reduced, as might be expected when the weak sites remaining on 4SA and 10SA are less efficiently phosphorylated by PKA. Indeed, our patch clamp experiments provide support for this interpretation since the average number of functional WT channels per patch during PKA stimulation was more than twice that of 10SA channels, even though similar levels of wild-type and mutated CFTR protein were expressed (Chang et al. 1993). These mutants (4SA, 10SA) have been extensively studied and alterations in their opening rates are most easily explained by their reduced PKA-mediated phosphorylation rather than by some non-specific effect of mutagenesis. Changes caused by reduced phosphorylation may be exacerbated by other factors, such as enhanced dephosphorylation; however this would not explain the residual activity of 10SA, since enhanced dephosphorylation would lead to underestimation of Po.

Phosphorylation mutants provide evidence that two nucleotides bind sequentially

The locking rates and Po values of mutant channels were both reduced by about half when compared with wild-type channels. A parsimonious explanation would be that two nucleotides bind sequentially at the NBFs, and the AMP-PNP site is only accessible when the channel is open (Mathews et al. 1995). Sequential binding has also been suggested based on the ineffectiveness of AMP-PNP when it is applied during the interburst period (Hwang et al. 1994).

Phosphorylation of dibasic PKA sites elevates Po by increasing the bursting rate

Considering the differences in experimental conditions, the mean burst duration estimated for wild-type CFTR in this study (at -30 mV and 22°C) agrees reasonably well with previous reports. CFTR channels in the Calu-3 submucosal gland cell line had open bursts of 1.8 s at 22°C (Haws, Finkbeiner, Widdicombe & Wine, 1994), while those in Vero cells had bursts lasting 1.55 s at 22°C (Dalemans et al. 1991). Tareen, Ono, Noma & Ehara (1991) calculated a mean burst duration of 635 ms when studying patches from cardiac cells at 35°C whereas Haws et al. (1992) found two closed states and a single open burst state lasting 800 ms at 22°C in patches from transformed airway cells (19HTE). Channels recorded in planar bilayers after incorporation of purified CFTR had a mean burst duration of 338 ms (Li et al. 1993). Burst durations at physiological temperatures (35°C) are in the range 120-250 ms (Fischer & Machen, 1994; Carson & Welsh, 1995).

The temperature dependencies of CFTR gating and locking have not been studied systematically. Locking by AMP-PNP is absent (Schultz, Venglarik, Bridges & Frizzell, 1995) or incomplete (Carson et al. 1995) at physiological temperatures (∼35°C). Moreover, we recently found that locked channels became unlocked when the temperature was increased from 23 to 30°C (Mathews et al. 1996). Although locking is not observed at physiological temperatures, the domain interactions that cause locking at room temperature probably persist above 30°C, since Po is still elevated when AMP-PNP is present at 37°C (C. J. Mathews & J. W. Hanrahan, unpublished work).

The relationship between Po and ATP was altered dramatically by mutations at the ten dibasic PKA sites even though 10SA channels were locked open by AMP-PNP, had the same mean burst duration as WT channels, and exhibited the same inhibition when exposed to high (> 5 mM) ATP concentrations. These results do not exclude a role for the ten dibasic sites in controlling burst duration or locking open of wild-type channels, since enhanced phosphorylation of the mutants at weak sites could potentially compensate for the loss of dibasic sites. There may also be complexities, such as offsetting stimulatory and inhibitory regulation by particular sites, that are missed when all the dibasic sequences are mutated. Comparisons between gating behaviours and phosphoforms of WT CFTR are needed to assess these possibilities.

A range of KM values has been reported for ATP-dependent gating of CFTR. The present results suggest that much of this variability could be due to differences in the phosphorylation state of CFTR. When compared with the 10SA mutant, the faster rates of bursting and locking open of WT channels are best explained by a phosphorylation-induced increase in nucleotide affinity, although this should be considered only an apparent affinity since it includes both binding and catalytic reactions. Li et al. (1996) observed a threefold decrease in the KM of ATPase activity measured biochemically in PKA-treated vs. untreated CFTR protein with no change in maximum velocity (Vmax). The present data are compatible with those results and with the previous finding that elevating ATP (without altering phosphorylation) increases Po by enhancing the bursting rate rather than by stabilizing open bursts (Winter et al. 1994), since, by increasing affinity, phosphorylation could have the same functional consequences as increasing the ATP concentration.

CFTR mutants lacking dibasic PKA sites can still be locked open by non-hydrolysable nucleotide analogues and have normal burst durations. Thus, phosphorylation at one or more cryptic sites is sufficient to support stabilizing interactions between NBFs that have been proposed to mediate locking open and control burst duration in wild-type channels. The low Po of 4SA and 10SA mutants reflects a shift in the ATP dependence of CFTR, which can be largely overcome by elevating ATP concentration. We propose that the dibasic sites control the bursting rate and Po of CFTR indirectly through modulation of its ATP sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandy Zheng and Jie Liao for cell culture. This work was supported by the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Medical Research Council of Canada, Respiratory Health Network of Centres of Excellence, and the NIH(NIDDK). C. J. M. was a fellow of the Montréal Chest Institute. J. W. H. is a MRC (Canada) scientist.

References

- Anderson M P, Berger H A, Rich D P, Gregory R J, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Nucleoside triphosphates are required to open the CFTR chloride channel. Cell. 1991;67:775–784. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Hwang T-C, Nairn A C, Gadsby D C. Coupling of CFTR Cl− channel gating to an ATP hydrolysis cycle. Neuron. 1994;12:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becq F, Jensen T J, Chang X-B, Savoia A, Rommens J M, Tsui L-C, Buchwald M, Riordan J R, Hanrahan J W. Phosphatase inhibitors activate normal and defective CFTR chloride channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:9160–9164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger H A, Travis S M, Welsh M J. Regulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel by specific protein kinases and phosphatases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:2037–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson M R, Travis S M, Welsh M J. The two nucleotide-binding domains of CFTR have distinct functions in controlling channel activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:1711–1717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1711. 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson M R, Travis S M, Winter M C, Sheppard D N, Welsh M J. Phosphate stimulates CFTR Cl− channels. Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80668-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson M R, Welsh M J. Structural and functional similarities between the nucleotide-binding domains of CFTR and GTP-binding proteins. Biophysical Journal. 1995;69:2443–2448. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80113-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X-B, Tabcharani J A, Hou Y-X, Jensen T J, Kartner N, Alon N, Hanrahan J W, Riordan J R. Protein kinase A (PKA) still activates CFTR chloride channel after mutagenesis of all ten PKA consensus phosphorylation sites. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:11304–11311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S H, Rich D P, Marshall J, Gregory R J, Welsh M J, Smith A E. Phosphorylation of the R domain by cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates the CFTR chloride channel. Cell. 1991;66:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sigworth F J. Fitting and statistical analysis of single-channel records. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-Channel Recording. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 483–587. [Google Scholar]

- Dalemans W, Barbry P, Champigny G, Jallat S, Dott K, Dreyer D, Crystal R G, Pavirani A, Lecocq J-P, Lazdunski M. Altered chloride ion channel kinetics associated with the delta F508 cystic fibrosis mutation. Nature. 1991;354:526–528. doi: 10.1038/354526a0. 10.1038/354526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Machen T E. CFTR displays voltage dependence and two gating modes during stimulation. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:541–566. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.3.541. 10.1085/jgp.104.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby D C, Nagel G, Hwang T-C. The CFTR chloride channel of mammalian heart. Annual Review of Physiology. 1995;57:387–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002131. 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M A, Greenwell J R, Argent B E. Secretin-regulated chloride channel on the apical plasma membrane of pancreatic duct cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1988;105:131–142. doi: 10.1007/BF02009166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson K L, Kopito R R. Effects of pyrophosphate and nucleotide analogs suggest a role for ATP hydrolysis in cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator channel gating. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:19349–19353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan J W, Tabcharani J A. Inhibition of an outwardly rectifying anion channel by Hepes and related buffers. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1990;116:65–77. doi: 10.1007/BF01871673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan J W, Tabcharani J A, Becq F, Mathews C J, Augustinas O, Jensen T J, Chang X-B, Riordan J R. Function and dysfunction of the CFTR chloride channel. In: Dawson D C, Frizzell R A, editors. Ion Channels and Genetic Diseases. New York: Rockefeller University Press; 1995. pp. 125–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haws C, Finkbeiner W E, Widdicombe J H, Wine J J. CFTR in Calu-3 human airway cells: channel properties and role in cAMP-activated Cl− conductance. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:L502–512. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.5.L502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haws C, Krouse M E, Xia Y, Gruenert D C, Wine J J. CFTR channels in immortalized human airway cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:L692–707. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.6.L692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T-C, Nagel G, Nairn A C, Gadsby D C. Regulation of the gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl channels by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:4698–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Mathews C J, Hanrahan J W. Phosphorylation by protein kinase C is required for acute activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by protein kinase A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:4978–4984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4978. 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Seibert F, Chang X-B, Riordan J R, Hanrahan J W. Activation of CFTR chloride channels by tyrosine phosphorylation. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1997;(suppl. 14):214A. [Google Scholar]

- Kartner N, Augustinas O, Jensen T J, Naismith A L, Riordan J R. Mislocalization of ΔF508 CFTR in cystic fibrosis sweat gland. Nature Genetics. 1992;1:321–327. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-321. 10.1038/ng0892-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly P J, Krebs E G. Consensus sequences as substrate specificity determinants for protein kinases and protein phosphatases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:15555–15558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Reyes E, Jensen T, Chang X, Rommens J M, Bear C E. The cystic fibrosis mutation (ΔF508) does not influence the chloride channel activity of CFTR. Nature Genetics. 1993;3:311–316. doi: 10.1038/ng0493-311. 10.1038/ng0493-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Wang W, Garami E, Hewryk M, Lee D, Rommens J M, Galley K, Bear C E. ATPase activity of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:28463–28468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28463. 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manavalan P, Dearborn D G, McPherson J M, Smith A E. Sequence homologies between nucleotide binding regions of CFTR and G-proteins suggest structural and functional similarities. FEBS Letters. 1995;366:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00463-j. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00463-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews C J, Tabcharani J A, Chang X-B, Riordan J R, Hanrahan J W. Pediatric Pulmonology. suppl. 12. 1995. Models for gating of CFTR chloride channels; p. 424A. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews C J, Tabcharani J A, Chang X-B, Riordan J R, Hanrahan J W. Characterization of nucleotide interactions with CFTR channels. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1996;(suppl. 13):221A. [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto M R, Cohn J A, Bertuzzi G, Greengard P, Nairn A C. Phosphorylation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:12742–12752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randak C, Neth P, Auerswald E A, Assfalg-Machleidt I, Roscher A A, Hadorn H-B, Machleidt W. A recombinant polypeptide model of the second predicted nucleotide binding fold of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is a GTP-binding protein. FEBS Letters. 1996;398:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01217-3. 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kikuchi A, Araki S, Hata Y, Isomura M, Kuroda S, Takai Y. Purification and characterization from bovine brain cytosol of a protein that inhibits the dissociation of GDP from and the subsequent binding of GTP to smg p25A, a ras p21-like GTP-binding protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:2333–2337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffzek K, Lautwein A, Kabsch W, Ahmadian M R, Wittinghofer A. Crystal structure of the GTPase-activating domain of human p120GAP and implications for the interaction with Ras. Nature. 1996;384:591–596. doi: 10.1038/384591a0. 10.1038/384591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz B D, Venglarik C J, Bridges R J, Frizzell R A. Regulation of CFTR Cl− channel gating by ADP and ATP analogues. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;105:329–361. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.3.329. 10.1085/jgp.105.3.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert F S, Tabcharani J A, Chang X-B, Dulhanty A M, Mathews C J, Hanrahan J W, Riordan J R. cAMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator residue ser-753 and its role in channel activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:2158–2162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2158. 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabcharani J A, Chang X, Riordan J R, Hanrahan J W. Phosphorylation-regulated Cl− channel in CHO cells stably expressing the cystic fibrosis gene. Nature. 1991;352:628–631. doi: 10.1038/352628a0. 10.1038/352628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tareen F M, Ono K, Noma A, Ehara T. β-Adrenergic and muscarinic regulation of the chloride current in guinea-pig ventricular cells. Journal of Physiology. 1991;440:225–241. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend R R, Lipniunas P H, Tulk B M, Verkman A S. Identification of protein kinase A phosphorylation sites on NBD1 and R domains of CFTR using electrospray mass spectrometry with selective phosphate ion monitoring. Protein Science. 1996;5:1865–1873. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venglarik C J, Schultz B D, Frizzell R A, Bridges R J. ATP alters current fluctuations of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: Evidence for a three state activation mechanism. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:123–146. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.1.123. 10.1085/jgp.104.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter M C, Sheppard D N, Carson M R, Welsh M J. Effect of ATP concentration on CFTR Cl− channels: A kinetic analysis of channel regulation. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:1398–1403. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80930-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]