Abstract

Changes in cell capacitance were monitored in whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from calf adrenal chromaffin cells using a software-based phase-tracking technique. Rapid endocytosis and exocytosis were observed in extracellular solutions containing either Ca2+ or Ba2+.

There was no significant difference in the magnitude or the time course of rapid endocytosis of cells stimulated in Ca2+ as compared to Ba2+. When cells were pretreated with caffeine and thapsigargin in order to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores, rapid endocytosis in Ba2+ was not affected. This indicates that Ba2+ itself is capable of supporting rapid endocytosis.

The application of the calmodulin inhibitor calmidazolium via the intracellular pipette solution did not inhibit rapid endocytosis. Although our findings are inconsistent with an immediate requirement for calmodulin in rapid endocytosis, they do not rule out an involvement on a longer time scale.

While rapid endocytosis was not affected by the substitution of Ca2+ with Ba2+, the maximum rate of exocytosis was higher in cells stimulated in Ca2+ than in Ba2+. Since Ba2+ currents were much larger than Ca2+ currents during depolarizations to +10 mV (the test potential used in these experiments), Ba2+ appears to be less efficient at promoting exocytosis than Ca2+.

Exocytosis in neurons and secretory cells is frequently followed by a period of rapid endocytosis during which a cell retrieves membrane added during secretion (Heuser & Reese, 1973). Defects in endocytosis, such as those caused by the shibire mutation in Drosophila melanogaster, are lethal (Kosaka & Ikeda, 1983; Herskovits, Burgess, Obar & Vallee, 1993). At the cellular level, rapid endocytosis is believed to regulate the surface area of the cell as well as contribute to vesicle recycling occurring at the synapse. Membrane retrieved during rapid endocytosis can be incorporated into new vesicles locally, without the need of processing by the Golgi apparatus (Heuser & Reese, 1973; Ryan, Reuter, Wendland, Schweizer, Tsien & Smith, 1993). Since it is difficult to separate molecular events involved in exocytosis from those responsible for rapid endocytosis, an understanding of the regulation of this phenomenon is still incomplete (Ryan, 1996). It is unclear whether there is more than one mechanism of rapid endocytosis as estimates of its speed have ranged from hundreds of milliseconds to tens of seconds (Ryan, 1996) or longer. For the purposes of this paper, any membrane retrieval with a time constant of less than a minute is considered rapid endocytosis. Since this definition spans a relatively broad range of retrieval rates, it may include mechanistically distinct membrane retrieval pathways.

The role of Ca2+ in activating rapid endocytosis remains a central unresolved issue. In one report, application of the secretagogue α-latrotoxin in a Ca2+-free environment caused vesicle depletion and terminal swelling in the frog neuromuscular junction (Ceccarelli & Hurlbut, 1980), effects not observed in the presence of Ca2+, which suggested that Ca2+ was necessary for vesicle recycling. In PC12 cells, however, α-latrotoxin activated endocytosis via both Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent mechanisms (Watanabe, Torda & Meldolesi, 1983). Synaptosomes stimulated with elevated K+ showed Ca2+-dependent rapid endocytosis (Gordon-Weeks & Jones, 1983). However, in a study which monitored the uptake of FM 1-43, a fast lipophilic fluorescent dye often used to study membrane dynamics, the amount of dye taken up after a period of stimulation was independent of extracellular Ca2+ in hippocampal neurons (Betz, Mao & Bewick, 1992; Ryan et al. 1993).

Capacitance measurements provide another means of observing exocytosis and rapid endocytosis with a high time resolution. Studies of chromaffin cells suggested that elevated Ca2+ increased the rate of rapid endocytosis (Neher & Marty, 1982). In pituitary melanotrophs, elevated intracellular Ca2+ was sufficient to elicit rapid endocytosis (Thomas, Lee, Wong & Almers, 1994). In this investigation, periods of slow exocytosis did not always initiate rapid endocytosis, which suggested that addition of new membrane was not sufficient to trigger rapid endocytosis. In contrast, rapid endocytosis was inhibited in retinal bipolar cells when [Ca2+]i exceeded 900 nM (von Gersdorff & Matthews, 1994). Another recent study reported that Ca2+ initiated rapid endocytosis by binding calmodulin (Artalejo, Elhamdani & Palfrey, 1996); rapid endocytosis was blocked by calmodulin inhibitors and Ba2+ was unable to support rapid endocytosis when it was substituted for Ca2+ in the extracellular solution. As calmodulin has a low affinity for Ba2+, this latter finding reinforced the conclusion that calmodulin was involved in the initiation of rapid endocytosis (Artalejo et al. 1996).

Using high-resolution capacitance measurements as an assay of cell surface area, we studied rapid endocytosis in chromaffin cells under conditions in which the extracellular solutions contained either Ca2+ or Ba2+. Previous studies have shown that Ba2+ was capable of supporting exocytosis in chromaffin cells, although the time course of exocytosis was extended (Douglas & Rubin, 1964; Seward, Chernevskaya & Nowycky, 1996). Our work indicates that rapid endocytosis in chromaffin cells was not abolished when cells were stimulated in Ca2+-free extracellular solutions containing Ba2+ and that Ba2+-mediated endocytosis was not due to the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. In addition, treatment with calmidazolium, a potent inhibitor of calmodulin, did not block rapid endocytosis. Taken together, these data are inconsistent with the proposal that calmodulin is the primary divalent cation receptor for rapid endocytosis. In this paper we also show that the maximum rate of exocytosis was higher in cells stimulated to secrete in Ca2+-containing solutions than in Ba2+-containing solutions. Ba2+ currents were almost an order of magnitude larger than Ca2+ currents, but exocytosis was approximately equal in the two solutions, indicating that Ca2+ supports secretion more efficiently than does Ba2+.

METHODS

Cell culture

Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells were prepared from animals approximately 18 weeks old. Adrenal glands, obtained from a local abattoir, were digested with collagenase and purified by density gradient centrifugation as described previously (Artalejo, Perlman & Fox, 1992). Cells were plated with 10 μm cytosine arabinoside at a density of 0.15 × 106 cells cm−2 on collagen-coated glass coverslips, and maintained for up to 96 h in an incubator at 37°C in an atmosphere of 92.5% air and 7.5% CO2 with a relative humidity of 90%. Half the incubation medium was exchanged every day. Experiments were performed 24-96 h after preparing the cells. Cultures included both adrenaline-containing and noradrenaline-containing cells, although adrenaline constituted 65% of the total catecholamine content. Adrenaline-containing cells were selected by visual inspection, as they tended to be more spherical and somewhat smaller than noradrenaline-containing cells (author's unpublished observations).

Capacitance recordings

Capacitance was measured using the phase tracking technique (Fidler & Fernandez, 1989). To measure changes in cell capacitance a 60 mV peak-to-peak sine wave (1.3 kHz) was added to the holding potential of -90 mV. The combination of sine wave and holding potential was chosen to remain in the range of -120 to -60 mV in order to provide a suitable signal-to-noise ratio without activating any voltage-dependent ion channels. The resulting current was analysed at two orthogonal phase angles using a software-based phase sensitive detector (PSD) with a temporal resolution of 11 ms per point (Joshi & Fernandez, 1988). The phase tracking technique allowed the determination of the correct phase angle for the PSD (Fidler & Fernandez, 1989) by switching a 500 kΩ resistor, in series with the cell input impedance and ground, in and out during sinusoidal stimulation. Conductance (series resistance) and capacitance values were continuously generated by the software. The deflections produced in the conductance plot by switching the resistor in and out serve as a 500 kΩ calibration for series resistance. Correct alignment of the PSD was achieved when these series resistance changes did not project into the capacitance plot. The whole-cell capacitance was cancelled completely with the slow capacitance compensation. Unbalancing the slow capacitance compensation by 100 fF provided the calibration signal for the capacitance trace. During stimulation of cells, the sinusoidal signal was interrupted and then restarted after stimulation was complete, as described below.

Solutions

Electrodes were filled with 110 mm caesium aspartate, 20 mm Hepes, 100 μm EGTA, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm ATP, 350 μm GTP and 14 mm creatine phosphate, adjusted to pH 7.3. In some experiments, 100 nM calmidazolium was also present in the intracellular solution. Before achieving whole-cell access, cells were in a solution containing 140 mm NaCl, 10 mm dextrose, 10 mm Hepes, 2.5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2 and 2 mm MgCl2. In some experiments, 10 mm caffeine and 1.5 μm thapsigargin were also present. In experiments not involving calmidazolium, the external solution was replaced after whole-cell break-in with a recording solution containing 140 mm TEA-Cl, 10 mm dextrose, 10 mm Hepes, 100 nM TTX, and either 10 mm CaCl2 or 10 mm BaCl2. Solution exchanges after whole-cell break-in were carried out with an Adams-List fast perfusion device (model Dad-10). Patch pipettes had resistances of 2-3.5 MΩ in the bath, although when identical pipettes were filled with a CsCl-containing solution their resistances were reduced by half. No compensation for the liquid junction potential was applied.

Fura recordings

Chromaffin cells were incubated for 45 min in a solution containing 140 mm NaCl, 10 mm dextrose, 10 mm Hepes, 2.5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 3 μm fura-2 (AM ester). After loading, cells were washed for 30 min with the identical solution but with no fura-2. Cells were maintained in the same solution during fluorescence measurement, except that it contained no fura-2 and no BSA. Changes in [Ca2+]i were produced by exposing cells to 10 μm histamine or 0.8 μm bradykinin in order to trigger release from intracellular Ca2+ stores. The stores were depleted by incubating cells in 10 mm caffeine and 1.5 μm thapsigargin for more than 90 min and then re-exposing them to 10 μm histamine and 0.8 μm bradykinin to ensure store depletion. Intracellular Ca2+ was monitored via a program kindly supplied by Dr Eric Gruenstein (University of Cincinnati, OH, USA). A composite graph of [Ca2+]i was prepared by averaging the data from all the cells, off-line. Measurements of [Ca2+]i were made every 10 s in each cell. Sixteen frames of data were collected while exciting cells with 340 nm wavelength light and then sixteen more frames were collected with 380 nm light. The sixteen frames at each wavelength were averaged and the background was subtracted. The ratio of the fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm was calculated and compared to a standard curve to determine [Ca2+]i. The standard curve was obtained by measuring fluorescence ratios of known Ca2+ concentrations in vitro.

Analysis

All fits to the data, which provided statistics and modelling parameters, were carried out using Microcal Origin (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA, USA). The maximum rate of exocytosis was determined by finding the largest change in capacitance that occurred during a depolarization and dividing it by the 204 ms time period during which capacitance was not acquired. This time period comprised a 160 ms depolarization, a 24 ms prepulse period at the holding potential, and a 20 ms postpulse period at the holding potential. If exocytosis is assumed to occur only during the depolarization (and not during the prepulse or postpulse periods), then the estimates of the maximum rate of exocytosis would be increased by 28%. The 20 ms postpulse period following a depolarization was sufficient for tail currents to subside completely before capacitance measurements were restarted. Decreases in capacitance were fitted with either one or two exponentials over a range of 10-90% of the total change in capacitance. The total capacitance change caused by endocytosis was measured from the time of maximal capacitance during stimulation to the first relative minimum after a stimulation, or to the end of the trace when no relative minimum was present. Although choosing the end of the trace is arbitrary, the same measurement was used in every capacitance trace in which no relative minimum was found. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test.

RESULTS

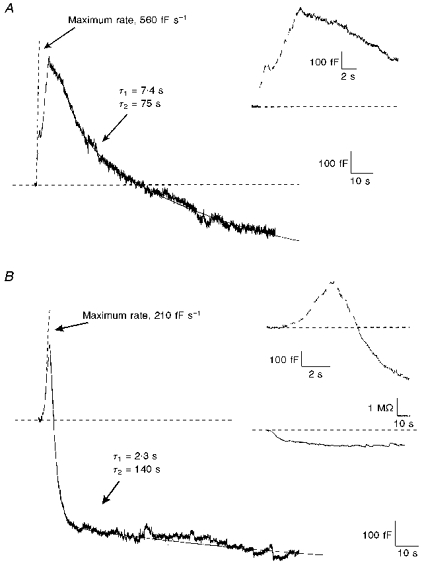

Figure 1 shows two typical capacitance recordings: one taken from a cell stimulated in 10 mm Ca2+ (Fig. 1A) and the other from a different cell stimulated in 10 mm Ba2+ (Fig. 1B). In each case, ten depolarizations to +10 mV, each lasting 160 ms, were applied at a frequency of 2 Hz. The sine waves used to determine membrane capacitance were stopped for 204 ms which included a 160 ms depolarization, a 24 ms prepulse period and a 20 ms postpulse period. During the prepulse and postpulse periods, cells were held at the holding potential of -90 mV. The inset in Fig. 1A and the top inset in Fig. 1B show each capacitance recording on an expanded time scale. The breaks in the capacitance trace correspond to the 204 ms recording gaps. The bottom inset in Fig. 1B shows the conductance trace (series resistance) obtained simultaneously with the capacitance trace. Small variations appeared in the conductance trace during stimulation, which is a common finding (Engisch & Nowycky, 1997). Changes in the conductance trace did not parallel capacitance changes, indicating that they were not due to a folding of one signal into the other.

Figure 1. Rapid endocytosis was similar when it was observed in either Ca2+- or Ba2+-containing solutions.

A, changes in the capacitance trace were triggered by Ca2+ influx. A train of 10 depolarizations lasting 160 ms to +10 mV, from a holding potential of -90 mV, was used to elicit release. Depolarizations were applied every 340 ms and are indicated by the gaps in the capacitance trace. The trace is fitted with two lines representing the maximum rate of exocytosis and a two-exponential fit of endocytosis. The largest change in capacitance during any depolarization was 115 fF, which occurred during the 204 ms that capacitance was not acquired, yielding a maximum rate of 560 fF s−1. In this capacitance trace, total endocytosis was calculated as the difference between the maximum capacitance value and the capacitance value at the end of the trace. Values corresponding to the fits are indicated in the figure. The inset shows the same data on an expanded time scale. B, changes in the capacitance trace were triggered by Ba2+ influx. Stimulation parameters were identical to those shown in A. The top inset shows the same data on an expanded time scale. The bottom inset shows the conductance trace (series resistance) obtained simultaneously with the capacitance trace. Although slight changes in conductance occurred over time, they did not parallel changes in capacitance. The pipette solution contained (mm): 110 caesium aspartate, 20 Hepes, 0.1 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 2 ATP, 0.350 GTP and 14 creatine phosphate. The extracellular Ca2+-containing solution (shown in A) contained (mm): 140 TEA-Cl, 10 dextrose, 10 Hepes, 10 CaCl2 and 0.0001 TTX. The extracellular Ba2+-containing solution (shown in B) contained (mm): 140 TEA-Cl, 10 dextrose, 10 Hepes, 10 BaCl2 and 0.0001 TTX.

In Fig. 1A and B, membrane capacitance increased immediately after the first depolarization, as a result of exocytosis. Between depolarizations, capacitance continued to climb, which indicates that exocytosis was not terminated on membrane repolarization. Exocytosis in Ca2+ was maximal at the beginning of the train, and the capacitance changes occurring during successive depolarizations diminished with time. In contrast, exocytosis in Ba2+ was maximal later in the train. The maximum rate of exocytosis was 560 fF s−1 in Ca2+ and only 210 fF s−1 in Ba2+. The maximum rate of exocytosis is shown in the figure as a dashed line. The total change in capacitance due to exocytosis in Fig. 1A was 580 fF and in Fig. 1B was 300 fF, although in both cases the actual magnitude was probably obscured by simultaneous endocytosis.

Since neither Fig. 1A nor 1B had a relative minimum in capacitance during the recording period, the decreases in capacitance due to rapid endocytosis were measured to the end of the trace. This arbitrary endpoint provided a conservative estimate of the magnitude of rapid endocytosis. The magnitude of rapid endocytosis in Fig. 1A was 800 fF and in Fig. 1B was 850 fF; in both cases this was greater than the magnitude of exocytosis. Rapid endocytosis exceeding exocytosis (excess retrieval) was observed with approximately the same frequency in Ca2+ (8 of 18 cells) as in Ba2+ (9 of 17 cells). The time course of rapid endocytosis was fitted (dashed line) as a sum of two exponentials, using time constants of 7.4 s and 75 s for the example in Ca2+ (Fig. 1A) and 2.3 s and 140 s for that in Ba2+ (Fig. 1B). Only the faster time constant was analysed further.

Capacitance recordings measure the net effect of both exocytosis and endocytosis; our measurements do not distinguish between the two processes. Therefore, the calculated time constants for rapid endocytosis should be viewed as upper estimates to allow for comparisons between Ca2+- and Ba2+-containing solutions. As the time constants in Ba2+ and Ca2+ were similar to each other and to those already published (Neher & Zucker, 1993; Thomas et al. 1994) it seems reasonable to assume that they activate rapid endocytosis through a similar mechanism.

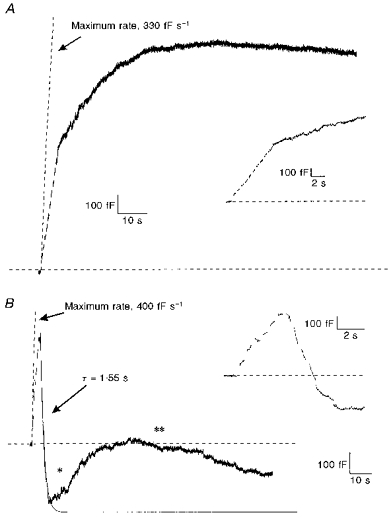

While the capacitance records shown in Fig. 1 are typical of cells undergoing stimulation in Ca2+ and in Ba2+, there was a wide variety of responses observed under both experimental conditions. Figure 2 illustrates two additional patterns of secretory responses following stimulation using protocols similar to those shown in Fig. 1. The insets show the same data on an expanded time scale. Both panels in Fig. 2 were taken from cells stimulated in Ba2+, although they are representative of some cells stimulated in Ca2+ as well. In Fig. 2A, exocytosis began normally following the first depolarization. In this cell, the maximum rate of exocytosis was 330 fF s−1 (shown by the dashed line), and the magnitude of exocytosis by the end of the stimulation was 800 fF. However, in contrast to the response illustrated in Fig. 1B, exocytosis in Fig. 2A continued past the end of the stimulation. The lack of decline in capacitance suggests that either rapid endocytosis was absent or the rate of rapid endocytosis never exceeded the rate of exocytosis. Since the maximum rate of exocytosis was fairly low, it is likely that rapid endocytosis was not triggered in this cell. In all, two of eighteen cells in Ca2+ and five of seventeen cells in Ba2+ had no detectable rapid endocytosis. Extended phases of exocytosis continuing well past the end of a depolarizing train (‘stimulus-decoupled’ exocytosis) have been previously described for chromaffin cells stimulated with Ba2+ (Seward et al. 1996). Four of five cells in Ba2+ which lacked rapid endocytosis showed ‘stimulus-decoupled’ exocytosis. Stimulus-decoupled exocytosis suggests that rapid endocytosis, when it occurred, overlapped exocytosis. Both rapid endocytosis (3 of 6 cells) and ‘stimulus-decoupled’ exocytosis (3 of 6 cells) were also observed in chromaffin cells stimulated in solutions containing 2 mm Ba2+ and in 2 mm Ca2+ (data not shown).

Figure 2. Capacitance changes following stimulation were variable.

A, exocytosis but not rapid endocytosis was observed following stimulation of a cell in Ba2+ (10 mm). Note that these data are from a different cell than that shown in Fig. 1. Stimulation parameters were identical to those described in Fig. 1B. The dashed line represents the maximum rate of exocytosis. The inset shows the same recording on an expanded time scale. Failure of rapid endocytosis following stimulation was also observed after stimulations in Ca2+-containing solutions. B, multiple increases and decreases in membrane capacitance produced by a single train of depolarizations in Ba2+ (10 mm). Conditions were identical to those in A. Rapid endocytosis occurred after exocytosis, but a second rising phase in capacitance (*) and a second falling phase (**) followed rapid endocytosis. The two lines indicate the maximum rate of exocytosis and a one-exponential fit of the initial period of rapid endocytosis. The inset shows the same recording on an expanded time scale. Solutions are described in Fig. 1.

Figure 2B illustrates another class of response to stimulation in Ba2+. Exocytosis began immediately after the first depolarization and attained a maximum rate of 400 fF s−1. Rapid endocytosis began before the end of the train of depolarizations, which was common for stimulations in Ba2+. In this example, a single exponential with a time constant of 1.55 s was used to fit the data. Fits of both exocytosis and rapid endocytosis based on the parameters listed above are shown as dashed lines. It is evident that these fits are insufficient to describe the membrane dynamics, since capacitance began to rise again as indicated by the single asterisk in the figure. Rapid endocytosis had accounted for a capacitance change of 770 fF when the second rising phase began. Within a minute of the onset of this second phase of rising capacitance, there was a second phase of falling capacitance, indicated by the double asterisk. Multiple rising and falling phases were observed in eleven of eighteen cells in Ca2+ and six of seventeen cells in Ba2+. Using capacitance measurements alone, it is not possible to determine whether the secondary capacitance increases and decreases are produced by mechanisms identical to those that produced the initial changes. It has been proposed that a second rising phase following rapid endocytosis reflects a compensation mechanism for excess retrieval with the aim of defending a surface area set-point (Artalejo et al. 1996). However, on several occasions we observed a second rising phase in capacitance when no excess retrieval had occurred. The existence of multiple rising and falling phases suggests that chromaffin cells do not regulate their surface area very tightly immediately following a stimulation. This behaviour has also been observed in mast cells (Almers & Neher, 1987).

Figure 3A and B summarizes the parameters of endocytosis from our data set. The mean capacitance change due to rapid endocytosis was 430 ± 80 fF in Ca2+ (n = 18) and 750 ± 170 fF in Ba2+ (n = 17). When normalized to the exocytosis preceding it, the mean capacitance change due to rapid endocytosis in Ca2+ was 105 ± 20% the capacitance change due to exocytosis. In Ba2+ the corresponding value was 220 ± 60%. The mean time constant of rapid endocytosis was 7.6 ± 2.2 s in Ca2+ (n = 16) and 4.1 ± 2.3 s in Ba2+ (n = 12). None of these differences between rapid endocytosis in Ca2+ and in Ba2+ was statistically significant, suggesting that there were no substantive differences when Ba2+ was substituted for Ca2+.

Figure 3. Exocytosis but not rapid endocytosis was affected by substitution of extracellular Ca2+ with Ba2+.

Parameters of both exocytosis and endocytosis used to model the data are plotted for experiments either in 10 mm Ca2+ or in 10 mm Ba2+. The mean capacitance change due to rapid endocytosis (A) and the mean time constant of rapid endocytosis (B) were not significantly different in cells stimulated in Ca2+ or in Ba2+. The mean capacitance change during exocytosis (C) was also not significantly different. However, the maximum rate of exocytosis (D) was approximately 3 times higher in cells stimulated in Ca2+ than in Ba2+. Stimulation conditions were identical to those described in Fig. 1. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Figure 3C and D, which compares parameters of exocytosis, shows that there were significant differences between exocytosis triggered in Ca2+ and in Ba2+. The maximum rate of exocytosis in Ca2+ was 750 ± 180 fF s−1 (n = 18), while in Ba2+ it was only 230 ± 20 fF s−1 (n = 17). Assuming each vesicle has a capacitance of 2 fF, this was equivalent to the fusion of 375 ± 90 secretory vesicles per second in Ca2+ and only 115 ± 10 secretory vesicles per second in Ba2+. However, the increase in capacitance due to exocytosis was 500 ± 80 fF in Ca2+ (n = 18) and 400 ± 40 fF in Ba2+ (n = 17), which was not a significant difference. It should be noted that ‘stimulus-decoupled’ exocytosis was specifically excluded from this calculation as it frequently continued past the period of our observations. In previous work, capacitance changes during ‘stimulus-decoupled’ exocytosis were reported to be much larger than capacitance changes during stimulus-coupled exocytosis (Seward et al. 1996). It is likely that both the maximum rate and overall quantity of exocytosis were affected by the substitution of extracellular Ca2+ with Ba2+.

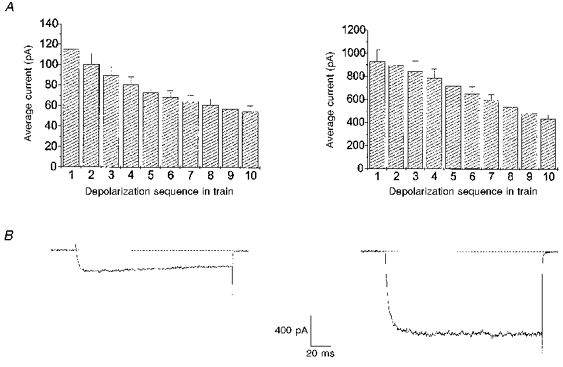

Figure 4A plots the average current pooled from all our experiments for each of the ten depolarizations in a train. The currents inactivated over the course of the train in both Ba2+ and Ca2+. The current during the last depolarization in the presence of either divalent ion was approximately half that in the first although it should be noted that the current magnitude in Ba2+ was approximately eight times larger than in Ca2+. In Fig. 4B, sample current traces are shown that were obtained from the chromaffin cells shown in Fig. 1. Each current record represents the first depolarization of the train. The peak current in Ca2+ (left) was 290 pA while that in Ba2+ (right) was 1120 pA. Inactivation of Ba2+ and Ca2+ currents has been previously documented, as has the greater permeation of Ba2+ than Ca2+ through calcium channels (Tsien, Lipscombe, Madison, Bley & Fox, 1988). Although the test potential we used (+10 mV) maximized Ba2+ current, it did not maximize Ca2+ currents, which peaked at +20 mV. For this reason, the differences we observed in the current amplitudes were partly the result of our depolarization protocol. Nevertheless, taken together our data indicate that Ca2+ was almost ten times more efficient overall at promoting secretion than Ba2+, confirming previous work (von Ruden, Garcia & Lopez, 1993; Seward et al. 1996). Furthermore, since the maximum rate of exocytosis was higher in Ca2+ than in Ba2+, during some phases of secretion Ca2+ may have been up to thirty times more efficient than Ba2+ in stimulating exocytosis.

Figure 4. Current magnitudes were much larger in Ba2+ than in Ca2+.

A, mean current magnitudes during each of the 10 depolarizations which made up a stimulation train are plotted for all experiments in 10 mm Ca2+ (left) and in 10 mm Ba2+(right). The 160 ms depolarizations to +10 mV were applied at 2 Hz from a holding potential of −90 mV. This test potential represents the peak of the Ba2+I-V curve, but the peak of the Ca2+I-V curve was at +20 mV. Note the difference in the scale of the ordinates for the two graphs. The current evoked by depolarization inactivated over the course of the train. B, sample current sweep taken from the first depolarization of a train. Current sweep obtained in Ca2+ (left) was taken from the stimulation illustrated in Fig. 1A; the maximum current is 290 pA. Current sweep obtained in Ba2+ (right) was taken from the stimulation illustrated in Fig. 1b; the maximum current is 1120 pA. Note, 400 μs of data are not shown at the beginning and end of the depolarization.

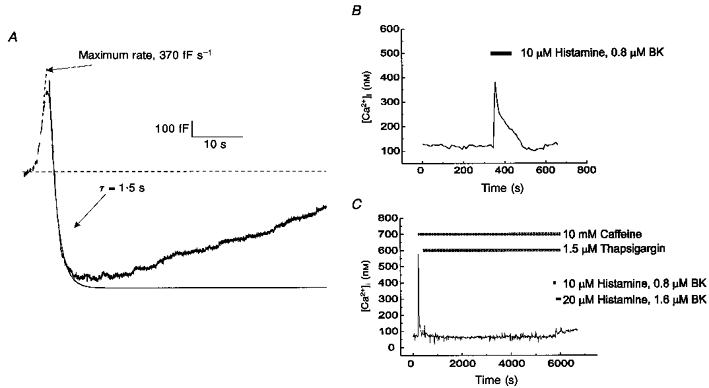

Ba2+ is known to release Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Przywara, Chowdhury, Bhave, Wakade & Wakade, 1993). To investigate the possibility that release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores is the mechanism by which Ba2+ initiates endocytosis, we depleted the stores by treating cells with 10 mm caffeine and 1.5 μm thapsigargin for a minimum of 90 min. After the depletion treatment was complete, extracellular Ca2+ was replaced with 10 mm Ba2+ and cells were stimulated using a standard train of depolarizations. Rapid endocytosis was still observed in three of the four cells treated in this manner. An example of a capacitance recording taken from a store-depleted cell is shown in Fig. 5A. The maximum rate of exocytosis in this recording was 370 fF s−1, and the magnitude of exocytosis was 500 fF. Rapid endocytosis which commenced during stimulation had a time constant of 1.5 s, and produced a 1100 fF change in membrane capacitance. Rapid endocytosis was followed by a second rising phase in the capacitance trace. The parameters for exocytosis and rapid endocytosis in cells with depleted intracellular Ca2+ stores were similar to those of untreated cells stimulated in Ba2+.

Figure 5. Ba2+-evoked rapid endocytosis was not due to the release of Ca2+ from internal stores.

Cells were store depleted by treatment for a minimum of 90 min in 140 mm NaCl, 10 mm dextrose, 10 mm Hepes, 2.5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm caffeine and 1.5 μm thapsigargin. A, capacitance recording from a store-depleted cell stimulated in 140 mm TEA-Cl, 10 mm dextrose, 10 mm Hepes, 10 mm BaCl2 and 100 nM TTX. Exocytosis and rapid endocytosis occurred normally following stimulation. Trace is fitted with two lines representing the maximum rate of exocytosis and a single-exponential fit of rapid endocytosis. A second rising phase is present in the capacitance trace. B and C, [Ca2+]i responses from treated and untreated cells to a challenge with agents promoting store release (10 μm histamine, 0.8 μm bradykinin (BK)). Untreated cells (B) showed increase in [Ca2+]i, as measured with fura-2 imaging. Cells treated for 90 min with caffeine and thapsigargin (C) no longer showed a response when challenged with 10 μm histamine and 0.8 μm bradykinin at the end of the treatment, indicating that Ca2+ stores were effectively depleted.

To ensure that our treatment was effective in depleting the intracellular Ca2+ stores, the effects of a challenge with 10 μm histamine and 800 nM bradykinin on cells treated with caffeine and thapsigargin were compared with untreated cells. [Ca2+]i was measured with fura-2 (see Methods). In untreated cells, shown in Fig. 5B, [Ca2+]i increased when the histamine and bradykinin were administered. Depletion treatment with caffeine and thapsigargin caused an initial spike in [Ca2+]i as the intracellular stores were emptied (Fig. 5C). However, when histamine and bradykinin were applied at the end of this treatment, there were no significant changes in [Ca2+]i. This demonstrates that the extended application of caffeine and thapsigargin was successful in depleting intracellular Ca2+ stores. The data suggest that rapid endocytosis in Ba2+-containing solutions was not mediated by the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores as the store-depletion protocols used in Fig. 5A and C were essentially identical.

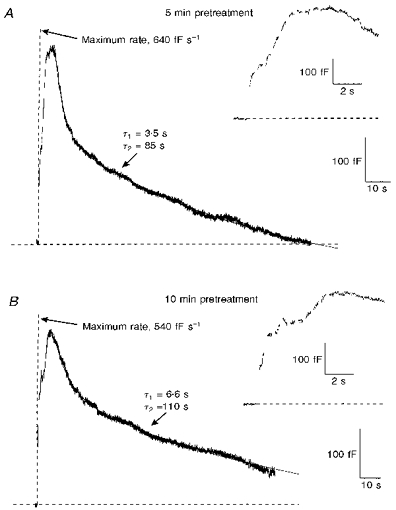

Since calmodulin has little affinity for Ba2+, the ability of Ba2+ to trigger rapid endocytosis in the absence of Ca2+ strongly suggests that rapid endocytosis does not require the immediate activity of calmodulin. To address this issue more directly, 100 nM calmidazolium, a potent calmodulin inhibitor, was introduced into the intracellular pipette solution. After allowing 5 min for calmidazolium to diffuse into the cell, we applied a train of ten depolarizations. These experiments were carried out in an extracellular saline containing 2 mm Ca2+. There was no block of rapid endocytosis in any of the six cells treated with calmidazolium. Figure 6A shows a typical secretory response observed during stimulation of a calmidazolium-treated cell. Rapid endocytosis began at the end of the stimulation and was fitted with time constants of 3.5 and 85 s. While rapid endocytosis did not continue past baseline in this example, excess retrieval did occur in two of the six calmidazolium-treated cells, consistent with our previous observations. Since there was no positive control for calmodulin inhibition, we allowed additional time for calmidazolium to diffuse into the cell and then applied a second train of depolarizations. The capacitance recording in Fig. 6B was taken 5 min after that shown in Fig. 6A, from the same cell. Rapid endocytosis was still not blocked, and was fitted with time constants of 6.6 and 110 s. Although there was some slowing and a decline in rapid endocytosis in the second stimulation, differences in rapid endocytosis between stimulations spaced 5 min apart were also observed in cells not treated with calmidazolium. Such changes were probably the result of a run-down of rapid endocytosis over time and over multiple stimulations. No inhibition of rapid endocytosis was observed in cells treated with other calmodulin inhibitors, including W-7 and the calmodulin inhibitory peptide fragment CaMKII290-309 (data not shown).

Figure 6. Calmidazolium, a potent calmodulin inhibitor, did not block rapid endocytosis.

A, capacitance changes from a cell in which 100 nM calmidazolium was added to the standard intracellular pipette solution (see Fig. 1). After gaining whole-cell access, 5 min passed before stimulation in order to allow time for calmidazolium to diffuse into the cell. Exocytosis and rapid endocytosis occurred normally following stimulation. The extracellular solution was a physiological saline containing 140 mm NaCl, 10 mm dextrose, 10 mm Hepes, 2.5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2 and 2 mm MgCl2. B, capacitance changes produced by a second stimulation of the same cell, 5 min after the first stimulation. Despite the additional time allowed for calmidazolium to enter the cell, rapid endocytosis still occurred following stimulation. Although the time constants of rapid endocytosis during the second stimulation differed from those in the first, a similar decline in the rate of rapid endocytosis over multiple stimulations was also observed in untreated cells.

DISCUSSION

Exocytosis can be triggered by increasing the cytoplasmic concentration of Ca2+, Ba2+ or Sr2+ (Douglas & Rubin, 1964; Neher & Zucker, 1993). In contrast, the role of Ca2+ and other divalent ions in triggering rapid endocytosis is much less clear (Ryan, 1996). In part, the difficulty in analysing rapid endocytosis has been in separating its requirements from those of exocytosis, which by necessity precedes it. In a study by Ceccarelli & Hurlbut (1980) α-latrotoxin was used to stimulate release from the frog neuromuscular junction in a Ca2+-independent manner. In the absence of Ca2+ the vesicle population was depleted more quickly and the uptake of horseradish peroxidase was reduced, suggesting that Ca2+ was required for endocytosis. However, more recent studies in PC12 cells suggest that α-latrotoxin may activate endocytosis through both Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent mechanisms (Watanabe et al. 1983). Other studies examined the Ca2+ dependence of endocytosis using the styryl dye FM 1-43 (Ryan et al. 1993), which can be used to follow the fate of membrane lipids as they undergo endocytosis and exocytosis (Betz et al. 1992). In hippocampal neurons, removing extracellular Ca2+ after initiating exocytosis did not affect the time course of endocytosis (Ryan et al. 1993). In addition, inhibition of the Na+-Ca2+ transporter with Li+ did not have an effect on endocytosis, although it caused an elevation in [Ca2+]i (Reuter & Porzig, 1995). These studies suggest that endocytosis is not Ca2+ dependent.

Capacitance measurements provide a means of observing exocytosis and endocytosis in single cells with very high time resolution. Studies of chromaffin cells using flash photolysis of photolabile caged Ca2+ to trigger catecholamine release showed that large increases in [Ca2+]i were followed by vigorous rapid endocytosis (Neher & Zucker, 1993; Heinemann, Chow, Neher & Zucker, 1994). A similar study in pituitary melanotrophs confirmed that photolysis of caged Ca2+ triggered rapid endocytosis (Thomas et al. 1994). In contrast, elevated [Ca2+]i was shown to slow rapid endocytosis in a study of retinal bipolar-cell terminals (von Gersdorff & Matthews, 1994). Thus, there has been no consensus on the requirement for Ca2+ in eliciting rapid endocytosis even when similar experimental techniques have been employed. In another recent study of chromaffin cells it was proposed that calmodulin was the divalent sensor for rapid endocytosis (Artalejo et al. 1996); Ca2+ dependence arose from the need to activate calmodulin. In this study, rapid endocytosis was suppressed by inhibitors of calmodulin, such as calmidazolium. Moreover, rapid endocytosis was not observed when secretion was triggered by Ba2+, which is known to have a low affinity for calmodulin. Rapid endocytosis could be observed in Ba2+ only if calmodulin had been previously activated. Another study in RINm5F cells, an insulinoma line, also found that rapid endocytosis was absent when secretion was triggered by Ba2+ (Richmond, Codignola, Cooke & Sher, 1996).

Our data show that the magnitude of rapid endocytosis, expressed either in absolute terms or as a fraction of the capacitance change due to exocytosis, was independent of whether Ca2+ or Ba2+ was present in the extracellular bath. Furthermore, the time course of rapid endocytosis was not significantly different in Ca2+ or in Ba2+. These findings are in agreement with studies of pancreatic β-cells, which showed that rapid endocytosis was not affected by the substitution of extracellular Ba2+ for Ca2+ (Proks & Ashcroft, 1995). Additionally, two other studies in chromaffin cells of surface binding to dopamine β-hydroxylase, a vesicle membrane protein, concluded that Ba2+ was capable of supporting vesicle recycling (Hunter & Phillips, 1989; Hurtley, 1993). The results presented in this paper are consistent with a model in which Ca2+ has no role in the events leading to rapid endocytosis. The data are also consistent with a model in which Ba2+ can directly trigger rapid endocytosis by acting as a substitute for Ca2+ in a Ca2+-dependent mechanism. It is known that Ba2+ is capable of substituting for Ca2+ in binding synaptotagmin, a possible molecular trigger for exocytosis (Davletov & Sudhof, 1994). In an analogous manner, a divalent sensor responsible for triggering rapid endocytosis may bind both to Ca2+ and to Ba2+. For this reason, we cannot conclude whether Ca2+ or Ba2+ has a direct role in rapid endocytosis but in any case the results are inconsistent with the existence of a divalent sensor, like calmodulin, which does not respond to Ba2+.

To examine the role of calmodulin in triggering rapid endocytosis, we treated chromaffin cells with calmidazolium, a potent inhibitor of calmodulin (Van Belle, 1984), perfused into the cells via the patch pipette. There was no significant change in rapid endocytosis when calmidazolium was allowed to diffuse into cells for either 5 or 10 min before stimulation. These results differ from a previous study which found that rapid endocytosis was completely blocked by the application of calmodulin inhibitors (Artalejo et al. 1996). Another study in chromaffin cells found endocytosis of vesicle antigens unchanged after applying trifluoperazine, a calmodulin inhibitor (Patzak et al. 1984). In yet another study, prolonged secretion of catecholamines by chromaffin cells stimulated with Ba2+ was also not affected by trifluoperazine (Heldman, Levine, Raveh & Pollard, 1989).

While Ca2+ released from internal stores appears to play a role in exocytosis (Augustine & Neher, 1992; Guo, Przywara, Wakade & Wakade, 1996), its involvement in rapid endocytosis is still uncertain. Ba2+-mediated exocytosis is not due to the release of Ca2+ from internal stores (Przywara et al. 1993), as exocytosis in Ba2+ has been shown to occur even in cells whose stores were depleted (von Ruden et al. 1993). Similarly, our data show that the release of Ca2+ from internal stores by Ba2+ is not necessary to trigger rapid endocytosis as prior depletion of stores did not affect rapid endocytosis. The relationship between rapid endocytosis and Ca2+ release from internal stores has also been investigated in pancreatic β-cells, in which it was found that rapid endocytosis proceeded normally even when sufficient intracellular EGTA was present to buffer any Ca2+ released from internal stores (Proks & Ashcroft, 1995). These results lend support to the conclusion that either Ca2+ is not required to initiate rapid endocytosis, or that Ba2+ can substitute for Ca2+.

The experiments outlined in this paper rule out an absolute requirement for Ca2+ as a trigger for the final steps of rapid endocytosis. However, it is possible that rapid endocytosis, like exocytosis, involves ‘priming’ steps which must be completed well before the entry of divalent cations into the cell. Our data suggest that if there is a priming step in rapid endocytosis that requires calmodulin, such a step should be completed at least 10 min before the final steps of endocytosis, as incubating cells in calmidazolium for 10 min did not block endocytosis. However, our findings are inconsistent with a model for rapid endocytosis in which calmodulin plays a triggering role analogous to that of synaptotagmin in exocytosis. The role of calmodulin in modulating rapid endocytosis, if any, is likely to be confined to events taking place well before vesicle fusion.

Regardless of whether calmodulin is involved in priming rapid endocytosis, our findings are consistent with the possibility that some form of priming occurs, since a gradual decline in rapid endocytosis was observed over multiple stimulations. If a priming step is slow, the 5 min intervals we used between stimulations may be too short to allow normal rapid endocytosis after multiple stimulations. The run-down of endocytosis with time may be initiated by the intracellular perfusion of the cell and may simply reflect the loss of a soluble factor necessary for rapid endocytosis (Gillis, Pun & Misler, 1991; Augustine & Neher, 1992; Ammala, Eliasson, Bokvist, Larsson, Ashcroft & Rorsman, 1993; Burgoyne, 1995); rapid endocytosis appears to be more robust in perforated-patch recordings (Engisch & Nowycky, 1997).

Alternatively the run-down of endocytosis observed may be use dependent. For example, rapid endocytosis might be substrate limited: it has been noted that membrane retrieval is selective for vesicular membrane over plasma membrane, and therefore rapid endocytosis might decrease as exocytosis runs down and less ‘retrievable’ membrane is made available (Suchard, Corcoran, Pressman & Rubin, 1981; Patzak et al. 1984). If this is so, membrane substrate for rapid endocytosis might accumulate over multiple episodes of exocytosis which are not followed by full recovery. Such episodes may occur spontaneously before a cell is voltage clamped, and for this reason the first round of triggered rapid endocytosis after whole-cell access may be larger than subsequent episodes, as noted by Thomas et al. (1994). Further experimentation will be required to resolve these issues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants to A. P. F. and by MSTP funding to P. N. (Medical Scientist National Research Service Award, NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant No. 5 T32 GM07281). We would like to thank Dr Zhong Zhou for kindly preparing the chromaffin cells.

References

- Almers W, Neher E. Gradual and stepwise changes in the membrane capacitance of rat peritoneal mast cells. Journal of Physiology. 1987;386:205–217. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammala C, Eliasson L, Bokvist K, Larsson O, Ashcroft F M, Rorsman P. Exocytosis elicited by action potentials and voltage-clamp calcium currents in individual mouse pancreatic B-cells. Journal of Physiology. 1993;472:665–688. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artalejo C R, Elhamdani A, Palfrey H C. Calmodulin is the divalent cation receptor for rapid endocytosis, but not exocytosis, in adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1996;16:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80036-7. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artalejo C R, Perlman R L, Fox A P. Omega-conotoxin GVIA blocks a Ca2+ current in bovine chromaffin cells that is not of the ‘classic’ N type. Neuron. 1992;8:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90110-y. 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90110-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine G J, Neher E. Calcium requirements for secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:247–271. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz W J, Mao F, Bewick G S. Activity-dependent fluorescent staining and destaining of living vertebrate motor nerve terminals. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:363–375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00363.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne R D. Fast exocytosis and endocytosis triggered by depolarisation in single adrenal chromaffin cells before rapid Ca2+ current run-down. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;430:213–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00374652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli B, Hurlbut W P. Ca2+-dependent recycling of synaptic vesicles at the frog neuromuscular junction. Journal of Cell Biology. 1980;87:297–303. doi: 10.1083/jcb.87.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davletov B A, Sudhof T C. Ca2+-dependent conformational change in synaptotagmin I. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:28547–28550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas W W, Rubin R P. The effects of alkaline earths and other divalent cations on adrenal medullary secretion. Journal of Physiology. 1964;175:231–241. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engisch K L, Nowycky M C. Threshold calcium requirement for excess membrane retrieval in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:A155. [Google Scholar]

- Fidler N, Fernandez J M. Phase tracking: an improved phase detection technique for cell membrane capacitance measurements. Biophysical Journal. 1989;56:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82762-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis K D, Pun R Y, Misler S. Single cell assay of exocytosis from adrenal chromaffin cells using ‘perforated patch recording. Pflügers Archiv. 1991;418:611–613. doi: 10.1007/BF00370579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Weeks P R, Jones D H. Binding and uptake of concanavalin A into rat brain synaptosomes: evidence for synaptic vesicle recycling. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1983;219:413–422. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1983.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Przywara D A, Wakade T D, Wakade A R. Exocytosis coupled to mobilization of intracellular calcium by muscarine and caffeine in rat chromaffin cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;67:155–162. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67010155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann C, Chow R H, Neher E, Zucker R S. Kinetics of the secretory response in bovine chromaffin cells following flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:2546–2557. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80744-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldman E, Levine M, Raveh L, Pollard H B. Barium ions enter chromaffin cells via voltage-dependent calcium channels and induce secretion by a mechanism independent of calcium. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:7914–7920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovits J S, Burgess C C, Obar R A, Vallee R B. Effects of mutant rat dynamin on endocytosis. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;122:565–578. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser J E, Reese T S. Evidence for recycling of synaptic vesicle membrane during transmitter release at the frog neuromuscular junction. Journal of Cell Biology. 1973;57:315–344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.57.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A, Phillips J H. The recycling of a secretory granule membrane protein. Experimental Cell Research. 1989;182:445–460. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtley S M. Recycling of a secretory granule membrane protein after stimulated secretion. Journal of Cell Science. 1993;106:649–655. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.2.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi C, Fernandez J M. Capacitance measurements. An analysis of the phase detector technique used to study exocytosis and endocytosis. Biophysical Journal. 1988;53:885–892. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka T, Ikeda K. Possible temperature-dependent blockage of synaptic vesicle recycling induced by a single gene mutation in Drosophila. Journal of Neurobiology. 1983;14:207–225. doi: 10.1002/neu.480140305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Marty A. Discrete changes of cell membrane capacitance observed under conditions of enhanced secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1982;79:6712–6716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Zucker R S. Multiple calcium-dependent processes related to secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1993;10:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90238-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzak A, Bock G, Fischer-Colbrie R, Schauenstein K, Schmidt W, Lingg G, Winkler H. Exocytotic exposure and retrieval of membrane antigens of chromaffin granules: quantitative evaluation of immunofluorescence on the surface of chromaffin cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1984;98:1817–1824. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.5.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Ashcroft F M. Effects of divalent cations on exocytosis and endocytosis from single mouse pancreatic β-cells. Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:465–477. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przywara D A, Chowdhury P S, Bhave S V, Wakade T D, Wakade A R. Barium-induced exocytosis is due to internal calcium release and block of calcium efflux. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:557–561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H, Porzig H. Localization and functional significance of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in presynaptic boutons of hippocampal cells in culture. Neuron. 1995;15:1077–1084. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J E, Codignola A, Cooke I M, Sher E. Calcium- and barium-dependent exocytosis from the rat insulinoma cell line RINm5F assayed using membrane capacitance measurements and serotonin release. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;432:258–269. doi: 10.1007/s004240050132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T A. Endocytosis at nerve terminals: timing is everything. Neuron. 1996;17:1035–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T A, Reuter H, Wendland B, Schweizer F E, Tsien R W, Smith S J. The kinetics of synaptic vesicle recycling measured at single presynaptic boutons. Neuron. 1993;11:713–724. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seward E P, Chernevskaya N I, Nowycky M C. Ba2+ ions evoke two kinetically distinct patterns of exocytosis in chromaffin cells, but not in neurohypophysial nerve terminals. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:1370–1379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01370.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchard S J, Corcoran J J, Pressman B C, Rubin R W. Evidence for secretory granule membrane recycling in cultured adrenal chromaffin cells. Cell Biology International Reports. 1981;5:953–962. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(81)90211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Lee A K, Wong J G, Almers W. A triggered mechanism retrieves membrane in seconds after Ca2+-stimulated exocytosis in single pituitary cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;124:667–675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R W, Lipscombe D, Madison D V, Bley K R, Fox A P. Multiple types of neuronal calcium channels and their selective modulation. Trends in Neurosciences. 1988;11:431–438. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belle H. The effect of drugs on calmodulin and its interaction with phosphodiesterase. Advances in Cyclic Nucleotide and Protein Phosphorylation Research. 1984;17:557–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Matthews G. Inhibition of endocytosis by elevated internal calcium in a synaptic terminal. Nature. 1994;370:652–655. doi: 10.1038/370652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ruden L, Garcia A G, Lopez M G. The mechanism of Ba2+-induced exocytosis from single chromaffin cells. FEBS Letters. 1993;336:48–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81606-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe O, Torda M, Meldolesi J. The effect of alpha-latrotoxin on the neurosecretory PC12 cell line: electron microscopy and cytotoxicity studies. Neuroscience. 1983;10:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]