Abstract

The ion selectivity of a membrane ion conductance that is inactivated by extracellular calcium (Cao2+) in Xenopus oocytes has been studied using the voltage-clamp technique.

The reversal potential of the Cao2+-sensitive current (Ic) was measured using voltage ramps (−80 to +40 mV) as a function of the external concentration (12–240 mM) of NaCl or KCl. The direction and amplitude of the shifts in reversal potentials are consistent with permeability ratios of 1:0.99:0.24 for K+:Na+:Cl−.

Current-voltage (I–V) relations of Ic, determined during either voltage ramps of 0.5 s duration or at steady state, displayed pronounced rectification at both hyperpolarized and depolarized potentials. However, instantaneous I–V relations showed less rectification and could be fitted by the constant field equation assuming the above K+:Na+:Cl− permeability ratios.

Ion substitution experiments indicated that relatively large organic monovalent cations and anions are permeant through Ic channels with the permeability ratios K+:NMDG+:TEA+:TPA+:TBA+:Gluc− = 1:0.45:0.35:0.2:0.2:0.2.

External amiloride (200 μM), gentamicin (220 μM), flufenamic acid (40 μM), niflumic acid (100 μM), Gd3+ (0.3 μM) or Ca2+ (200 μM) caused reversible block of Ic without changing its reversal potential.

Preinjection of oocytes with antisense oligonucleotide against connexin 38, the Xenopus hemi-gap-junctional protein, inhibited Ic by 80 % without affecting its ion selectivity, thus confirming and extending the recent suggestion of Ebihara that Ic represents current carried through hemi-gap-junctional channels.

In vitro and in vivo maturation of oocytes resulted in a significant decrease in Ic conductance to 7 % and 2 % of control values, respectively. This developmental downregulation of Ic minimizes any toxic effect Ic activation would have when the mature egg is released into Cao2+-free pond water.

The results of this study are discussed in relation to other Cao2+-inactivated conductances seen in a wide variety of cell types and which have previously been interpreted as arising either from Cao2+-masked channels or from changes in the ion selectivity of voltage-gated Ca2+ or K+ channels.

For amphibian oocytes it has long been recognized that removal of extracellular calcium (Cao2+) from the bathing solution results in membrane depolarization (Tupper & Maloff, 1973; Dascal, 1987). The current underlying this depolarization has been referred to as Ic (Arellano, Woodward & Miledi, 1995). The events associated with this depolarization are toxic to immature oocytes since they lose viability and rupture within 12 h of incubation in zero-Ca2+ Ringer solution. Despite Ic being a large and consistently observable endogenous current, attempts to analyse its ion selectivity have given conflicting results. Originally Tupper & Maloff (1973), using tracer flux techniques, concluded that the Cao2+-sensitive depolarization in Ranapipiens arose through a large increase in permeability to Na+ with little contribution from K+ and Cl−. More recently, two groups using voltage-clamp techniques have analysed Ic in Xenopus oocytes. One group concluded that Ic was a cation-selective conductance which did not distinguish between Na+ and K+ (Arellano et al. 1995). The other group concluded that Ic was a Cl−-selective conductance with no apparent permeability for Na+ and K+ (Weber, Liebold, Reifarth, Uhr & Clauss, 1995a, b;Reifarth, Amasheh, Clauss & Weber, 1997). These apparently contradictory results may indicate that heterogeneities exist in the population of Ic channels in Xenopus oocytes such that Ic is mediated by subsets of cation- and anion-selective channels. In this case, under specific circumstances, one subset of channels might be masked so that the other subset dominates.

Clearly the ion selectivity of Ic has important implications both for the identity of the underlying channel mechanism(s) and for comparison with other Cao2+-masked conductances seen in a variety of cell types, including epithelium (Van Driessche, Simaels, Aelvoet & Erlij, 1988), skeletal muscle (Almers, McCleskey & Palade, 1984), cardiac muscle (Guo, Ono & Noma, 1995; Mubagwa, Stangl & Flemeng, 1997), neurone (DeVries & Schwartz, 1992) and lymphocytes (Grissmer & Cahalan, 1989). Specifically, Arellano et al. (1995) initially considered that the Ic channel may be a hemi-gap-junctional channel (DeVries & Schwartz, 1992) or possibly the Gd3+-sensitive mechanically gated (MG) cation channel studied extensively in oocyte patch-clamp recordings (for review see Hamill & McBride, 1996). However, they ruled out both possibilities, the former because of the lack of anion permeability of Ic and the latter because of the Ca2+-independent activation and fast adaptation of MG channel activity in Xenopus oocytes (Hamill & McBride, 1992).

Because of our long term interest in single MG channels and their as yet unresolved contribution to macroscopic oocyte currents, we were interested in resolving the underlying basis of the Ic conductance and, additionally, in testing the above subset channel hypothesis for Ic. Therefore, as a first step we have re-examined the ion selectivity of the macroscopic Ic. We followed two basic approaches to identify the ion species contributing to Ic, both involving measurement of reversal potential shifts. In one case, the shifts occur as a result of changes (i.e. increase or decrease) in the external NaCl (or KCl) concentration. In the other case, the shifts occur as a result of ion substitutions with large organic ions, expected to have reduced or zero permeation. In both approaches the reversal potential shifts can be compared with theoretical predictions for ideally selective cation- or anion-selective channels (see Appendix).

As a second step in testing the subset channel hypothesis, we have made attempts to block selectively one of the channel subsets. If Ic is mediated by independent cation- and anion-selective channels, one would expect to see shifts in Ic reversal potential as one subset of channels is selectively blocked. We have tested a number of agents that are commonly used to block either cation channels (e.g. amiloride and gentamicin, which like Gd3+ block MG cation channels (Hamill & McBride, 1996)), or anion channels (e.g. flufenamic, niflumic and 9-anthracene carboxylic acids; Pappone & Lee, 1995). A preliminary account of this study has been presented to the Biophysical Society (Zhang, McBride & Hamill, 1997).

METHODS

Preparation of Xenopus oocytes

Mature female frogs (Xenopus laevis) were purchased from two different sources, Xenopus I (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and Nasco (Modesto, CA, USA). We observed no differences in the results from differently sourced frogs. Frogs were anaesthetized by being placed for approximately 20 min in a beaker containing 300 mg ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulphonic acid (Aldrich) in 200 ml of distilled water. Sterile surgical procedures were used to remove oocytes, which were then treated with collagenase (1–4 mg ml−1) at room temperature for 1–2 h in normal Ringer solution. After washing with Barth's solution, immature stage V and VI oocytes were selected and stored at 18°C in Barth's solution. Measurements were performed within 7 days after removal. In most cases, oocytes were defolliculated manually by forceps to facilitate microelectrode penetration. However, we saw no difference between Ic measured from folliculated and defolliculated oocytes taken from the same donor frog. Only oocytes with initial resting potentials of -30 mV or more negative were studied. Experiments were performed over the period March 1996 to September 1997. No seasonally dependent effects on results were observed.

Solutions and chemicals

Normal Ringer (NR) solution contained (mM): 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 Hepes, 1.8 CaCl2, pH 7.2. Barth's solution contained (mM): 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 5 Tris, 0.82 MgSO4, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 CaCl2, pH 7.4, supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 each of streptomycin, penicillin and amikacin. The Ca2+-free Ringer solution had the same composition as NR solution except that no Ca2+ was added. In some experiments, measurements were made in which 2 mM EGTA (NaOH) was added to the Ca2+-free Ringer solution with no differences observed. NaCl (or KCl) solutions (pH 7 in all cases) of 12, 24, 120 and 240 mM were used to measure ion selectivity of Ic. In some experiments, mannitol was used to adjust the osmolarity with no differences observed. N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG+), tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl), tetrapropylammonium chloride (TPA-Cl), tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBA-Cl) and sodium gluconate (Na-Gluc) were used as ion substitutes in extracellular solutions. 9-Anthracene carboxylic acid was from Alfa Products (Ward Hill, MA, USA) and GdCl3 from Aldrich. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Electrophysiological recording and data analysis

Because of the wide range of ionic strengths of the solutions used, significant shifts in junction potential can occur. Furthermore, because of the large Ic (i.e. up to 10 μA), electrode polarizing effects can also be significant. To minimize these effects, a three-microelectrode voltage-clamp configuration (Stühmer, 1992), rather than the conventional two-electrode clamp, was used. The intracellular voltage recording and current passing microelectrodes, as well as the voltage reference microelectrode (2 μm tip diameter) used as a high impedance bath probe, were filled with 3 M KCl. The ground macroelectrode was an agar bridge filled with NR solution. In order to avoid contamination of the oocyte by KCl which leaked continually from the external bath probe, the probe was positioned adjacent to the suction outlet of the bath. The bath, which was home-made with a volume of 200 μl, was perfused continuously at a speed of ∼3 ml min−1. The voltage-clamp amplifier was an Axoclamp 2A (Axon Instruments).

Membrane potentials and currents were digitized by a PC through a Lab Master DMA 100 kHz (Scientific Solutions, Inc., Solon, OH, USA) data acquisition and control board using FastLab (Indec Systems, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) software. Voltage ramps were generated by a custom built circuit controlled by the computer. All results are expressed as means ±s.d.

Constant field equations to calculate relative ion permeabilities and fit I–V relations

The Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) constant field equation described below was used to calculate the relative ion permeabilities according to the measured reversal potentials (Vrev):

|

(1) |

where the [C] and [A] denote cation and anion concentration, respectively, the subscripts i and o denote intracellular and extracellular, respectively, PC and PA are the cation and anion permeabilities, respectively, and R, T and F have their usual meaning (Hille, 1992).

The GHK current equation for monovalent ions as described below was used to fit the measured current-voltage relations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where β = exp(-VF/RT), V is the membrane potential, IC, IA and I represent the currents carried by a monovalent cation and a monovalent anion and the total membrane current, respectively (Hille, 1992).

In order to check if deviations from constant field behaviour could be explained by surface charge screening as a function of ionic strength, fits were made taking into account surface charge effects using the following equations (McLaughlin, 1989; Hille, 1992):

| (5) |

| (6) |

where Ψo is the surface potential, σ is the surface charge density, ɛr is the dielectric constant of the solution, ɛo is the permittivity of free space, N is Avogadro's number, C is the ion (cation or anion) concentration in bulk phase, Co is the surface ion (cation or anion) concentration and k, T, e and z have their usual meaning.

In vitro and in vivo oocyte maturation

To induce oocytes to mature in vitro, immature stage VI oocytes were placed in NR solution supplemented with 10 μM progesterone for 12 h. Maturation was judged by germinal vesicle breakdown as indicated by the development of a white spot on the animal pole. To induce oocytes to mature in vivo, females frogs were primed by injecting 50 i.u. of pregnant mare serum into the dorsal lymph sac. Three days later the frogs were injected with 500–700 i.u. human chorionic gonadotropin to induce ovulation which typically occurred ∼12 h later. In order to record electrically from eggs, they were de-jellied according to the procedure described in Lindsay & Hedrick (1989). This involved first the collection of the jelly-coated eggs in DeBoers (DB) solution (mM: 110 NaCl, 1.3 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, buffered to pH 7.2 with NaHCO3), which were then de-jellied by incubation for 1–2 min with 45 mM mercaptoethanol in Tris-buffered DB solution (i.e. 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.9) and then washed extensively with DB solution. In control experiments we confirmed that the de-jellying procedure applied to immature oocytes did not block Ic.

Synthesis and microinjection of antisense oligonucleotides

Antisense oligonucleotides against connexin 38, the endogenous Xenopus gap junction protein (Ebihara, Beyer, Swenson, Paul & Goodenough, 1989), and scrambled antisense oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Sealy Centre for Molecular Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, with sequences according to Ebihara (1996). Oocytes were injected with oligonucleotides (40 ng per oocyte) using a Model NA-1 microinjector (Sutter Instrument Co.). The injected oocytes were kept in Barth's solution at 18°C for 3–5 days after which electrophysiological measurements were made.

RESULTS

Removal of external Ca2+ induces a large reversible conductance increase in Xenopus oocytes

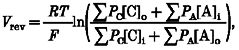

Xenopus oocytes voltage clamped at negative membrane potentials develop a large inward current (Ic) when the external bath solution is switched from NR solution to Ca2+-free Ringer solution (Fig. 1A;Arellano et al. 1995; Weber et al. 1995a). Ic was present in all oocytes studied (> 200 oocytes from 18 donor frogs) but could vary in amplitude from 100 nA to 10 μA, depending upon the donor frog. Using a voltage ramp protocol (Fig. 1B, upper panel) the measured reversal potential of Ic in the Ca2+-free solution was -8.2 ± 3.8 mV and was independent of the magnitude of Ic conductance (29 oocytes from 5 donor frogs). These results are consistent with published reversal potentials for Ic of -9.5 ± 3 mV (±s.d.) (Arellano et al. 1995) and -12.2 ± 0.8 mV (±s.e.m.) (Weber et al. 1995a). Note the rectification that develops in the current at both hyperpolarized and depolarized potentials (Fig. 1B, lower panel). As pointed out by Arellano et al. (1995), the Ic reversal potential differs from the calculated equilibrium potentials for Cl− (∼-30 mV), K+ (∼-100 mV) and Na+ (∼+60 mV) in Xenopus oocytes (Dascal, 1987) and indicates that the Ic conductance involves increased permeability to more than one of these ions.

Figure 1. A typical recording of the development of Ic upon removal of external Ca2+.

A, membrane current in response to the removal of external Ca2+. The oocyte was held at −40 mV throughout. B membrane potential and current of an oocyte in response to an applied voltage ramp in external Ca2+-free solution. The oocyte was held at -30 mV before and after a voltage ramp of 500 ms (-120 to +50 mV) was applied. The dotted lines show how the reversal potential was determined.

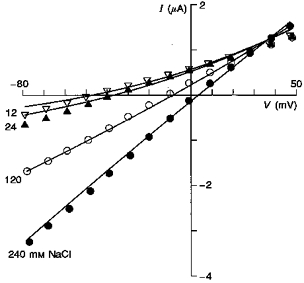

Ic conductance displays a higher permeability to monovalent cations than to anions

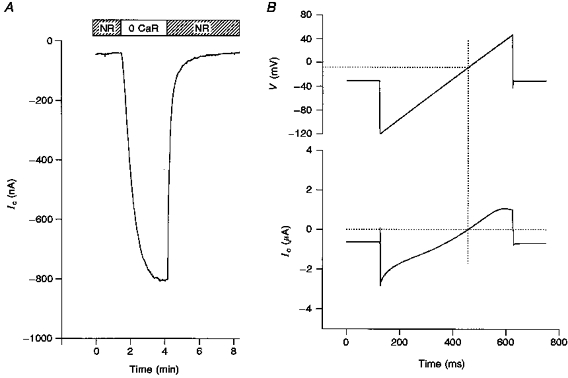

In order to identify the ion species contributing to Ic, we have studied the effects of changing external ion (i.e. NaCl or KCl) concentrations on I–V relations and reversal potentials. Figure 2 shows I–V relations of Ic measured in 24, 120 and 240 mM NaCl in two different oocytes. The I–V relations clearly indicate (i) an intersection point in the first quadrant and (ii) reversal potential (Vrev) shifts to more positive values with increasing external NaCl concentration. As described below and in the Appendix these qualitative and quantitative features rule out either ideally cation or anion conductances and indicate that Ic, although predominantly cation selective, also has an anion permeability.

Figure 2. I–V relations measured from two different oocytes in 24, 120 and 240 mM extracellular NaCl.

The solutions were all Ca2+ free. Note the common intersection point of the curves in the first quadrant and similar shifts in reversal potentials to positive values with increasing ion concentration. In the top graph the resting conductance of the oocyte in NR solution (i.e. containing 1.8 mM Ca2+) is shown as a dotted line.

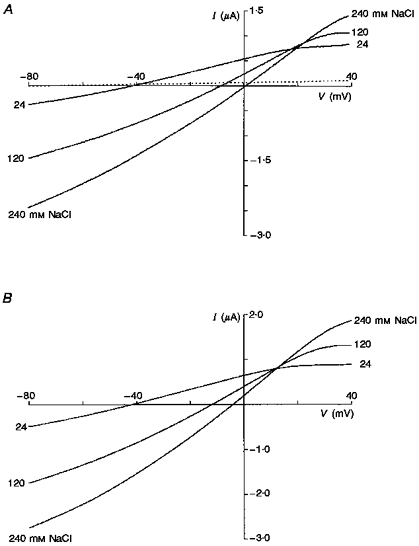

Figure 3 summarizes the reversal potential values as a function of external NaCl (Fig. 3A) and KCl (Fig. 3B) concentrations. In each case the dotted lines represent the theoretical fits for a conductance that is cation selective (positive slope) or anion selective (negative slope). The continuous lines represent a theoretical fit for a conductance with permeability ratios of 1:0.99:0.24 for K+:Na+:Cl−. These ratios derive from the average reversal potentials measured in eleven oocytes (from 3 donor frogs, 2 sources) in which complete data sets were obtained over the four ion concentrations. Furthermore, experiments in over fifty other oocytes from six donor frogs measured during the course of the entire year never gave evidence (i.e. negative slopes as in Figs 3A and B) indicating that Ic was more permeable for anions than cations. In fact, in no case did the anion/cation permeability ratio exceed 0.4.

Figure 3. Summaries of the reversal potentials of Ic in external solutions with different NaCl (A) and KCl (B) activities.

•, means of the measured reversal potentials; the error bars indicate standard deviations (NaCl: 8 oocytes from 2 donors; KCl: 3 oocytes from 1 donor). The continuous lines were calculated according to the GHK equation (eqn (1)) with the relative permeabilities obtained by curve fitting, i.e. PNa/PK = 0.99, PCl/PK = 0.24. The dotted lines show predictions for ideally cation- and anion-selective conductances. The intracellular permeant ion activities were assumed to be 110 mM for K+, 6 mM for Na+ and 33 mM for Cl−.

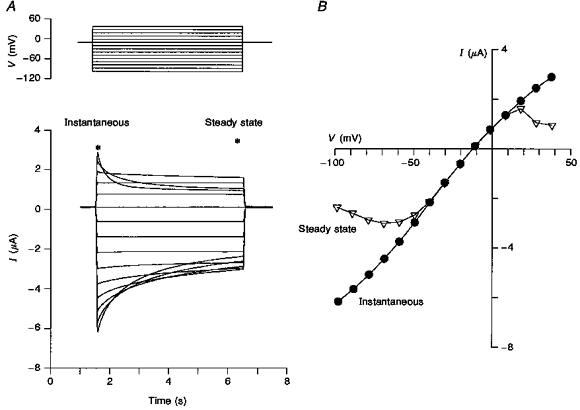

Initial attempts to fit the constant field equation to the ramp I–V relations using the above permeability ratios proved unsuccessful. This failure is most likely to reflect the pronounced rectification evident in these I–V relations. In order to distinguish whether the rectification was due to intrinsic single-channel current rectification or to channel gating, we compared instantaneous with steady-state I–V relations. Figure 4 indicates a dramatic difference in the instantaneous and steady-state relations in which the former was almost linear, indicating that most of the rectification was probably due to channel gating. Comparison with Fig. 2 indicates the 0.5 s duration ramp I–V is intermediate between the instantaneous and steady-state I–V relations. Note that in spite of the time-dependent differences in the I–V relation shapes measured with the three protocols, the reversal potentials were the same. Similar difference in instantaneous and steady-state I–V relations have been reported by Arellano et al. (1995).

Figure 4. Instantaneous versus steady-state I–V.

A, typical Ic in response to voltage steps. The asterisks indicate the time at which the respective I–V relations were made. B, the instantaneous I–V was measured 5 ms after the beginning of the voltage pulse. The steady-state I–V relation was determined by measuring after 4.8 s from the beginning of the voltage pulse. The steady-state I–V relation shows significantly more rectification but with no difference in reversal potential compared with the instantaneous I–V relation.

Figure 5 shows instantaneous I–V relations as a function of external NaCl concentration. The continuous lines are the constant field predictions based on permeability ratios as determined in Fig. 3 and indicate good fits to the measured data at 240 and 120 mM NaCl but somewhat poorer fits to data measured in 24 and 12 mM NaCl. Assuming we are measuring accurately the instantaneous I–V over the full range of ionic conditions, the less than perfect fits may indicate that constant field predictions are not obeyed. In this regard, we specifically tested whether differences in surface charge screening at the different ionic strengths could distort the I–V relations. However, curve fitting taking into account surface charge effects (see Methods) did not significantly improve the fits to the data (fits not shown). Alternatively, it may be that ion interactions within the channel cause deviations from constant field behaviour at low external ion concentrations. However, quantitative distinction between other possible permeation mechanisms for this conductance will require single-channel current-voltage measurements for Ic. To date our attempts to measure single-channel activity for Ic in patches have been unsuccessful, probably reflecting an overall low membrane channel density and high single-channel conductance.

Figure 5. Instantaneous I–V relations of Ic in different extracellular concentrations of NaCl measured from a single oocyte.

The symbols represent the measured instantaneous currents. The continuous lines were calculated according to the GHK current equation (eqns (2), (3) and (4)) assuming permeability ratios PNa/PK = 0.99 and PCl/PK = 0.24 and intracellular ion activities of 110 mM for K+, 6 mM for Na+ and 33 mM for Cl−.

Ic conductance is permeable to relatively large organic cations and anions

Given the above results indicating that the Ic conductance shows a permeability to both cations and anions, we were interested in estimating the pore size of the Ic channel(s). Specifically, we tested the permeability to some large monovalent organic ions in an attempt to find a cation and anion that did not permeate the Ic channel(s). However, no impermeant cation or anion was found. Table 1 shows the shifts in reversal potential as external Na+ or Cl− was progressively substituted with larger ions. The results indicate that all the large ions tested showed significant permeation through the Ic pores. For example, Table 2 indicates that the largest cation tested, TBA+, had a permeability ratio of 0.2. This would place the minimal pore diameter at least greater than 1 nm (Robinson & Stokes, 1955). In the case of the anion substitution, gluconate permeated the channel that conducts Ic almost as well as Cl−, indicating a minimal anion pore size at least greater than 0.6 nm (Halm & Frizzell, 1992).

Table 1.

The reversal potential shifts (mV) of Ic induced by substitution of extracellular Na+ or Cl− with organic ions

| Percentage substitution | NMDG+ (n = 2) | TEA+ (n = 2) | TPA+ (n = 3) | TBA+ (n = 4) | Gluconate− (n = 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | −6.9 ± 3.2 | −5.8 ± 0.04 | −9.4 ± 0.4 | −7.1 ± 4.8 | 0.2 ± 0.3 |

| 75 | −12.4 ± 4.6 | −14.7 ± 1.0 | −18.6 ± 0.6 | −16.4 ± 1.7 | 0.2 ± 1.8 |

| 100 | −19.7 ± 6.1 | −22.3 ± 1.8 | −32.7 ± 2.0 | −26.8 ± 4.6 | 0.5 ± 1.3 |

Table 2.

Permeability of Ic channels to some organic ions

| Organic ions | PX/PK | Diameters (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| NMDG+ | 0.45 | — |

| TEA+ | 0.35 | 0.71–0.88 |

| TPA+ | 0.2 | 0.87–1.11 |

| TBA+ | 0.2 | 1–1.38 |

| Gluconate− | ∼0.2 | ∼0.59 |

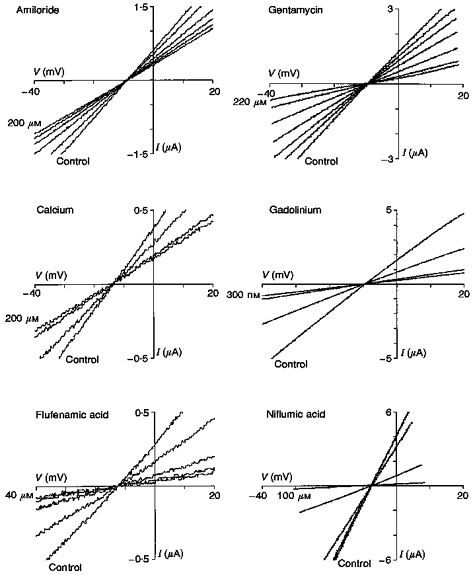

The effect of channel blockers on Ic

The above results cannot alone distinguish between a heterogeneous population of channels consisting of subsets of cation- and anion-selective channels and a single population of channels that are only partially selective for cations over anions. In an attempt to distinguish between these possibilities we have tested the effects of some commonly used cation and anion channel blockers on Ic and its reversal potential. Figure 6 shows the effects of six agents that partially block Ic, namely amiloride, gentamicin, Ca2+, Gd3+, flufenamic acid and niflumic acid. In all six cases, Ic block occurred with no change in reversal potential. This indicates that the effect was not due to block of one subset of channels with an ion selectivity different from the unblocked subset. Our study is the first report that the clinically relevant drugs amiloride and gentamicin block Ic. Previous studies have reported Ic block with Gd3+ (Arellano et al. 1995), flufenamic acid and niflumic acid (Weber et al. 1995a,b). In addition to the above agents we also tested the Cl− channel blockers 9-anthracene carboxylic acid (2 mM) and 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic acid (SITS) (200 μM) (Pappone & Lee, 1995) but found no blocking effect on Ic. In the case of K+ channel blockers, both TEA+ and Cs+ were found to permeate the channel, with TEA+ less permeant (see Table 2) and Cs+ more permeant than K+. In conclusion, the above observations do not support the hypothesis of independent subsets of Ic pores with differing ion selectivities.

Figure 6. The effect channel blockers on Ic.

In each panel the I–V relation labelled Control represents the measurement made in Ca2+-free Ringer solution immediately before perfusing a different oocyte with one of the agents in the same solution. The other I–V relations show the time course of the Ic block by the agent indicated. Note all the agents decrease the conductance of Ic without altering its reversal potential. For all I–V relations the resting I–V relation in NR solution was subtracted. The time between I–V relations is not constant but the final I–V relations represent the steady state in the presence of the agents. The variable current scale represents oocyte variability in Ic.

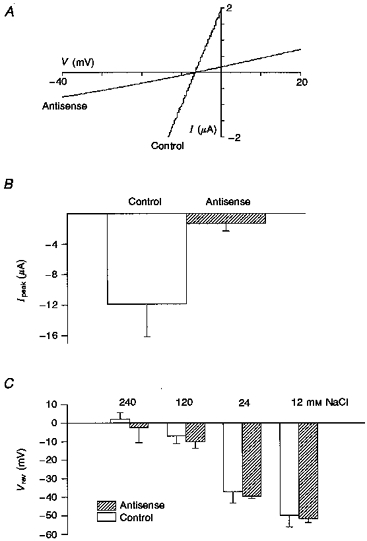

The Ic channel is most probably the endogenous hemi-gap-junctional channel

The properties we have described above for the Ic channels, namely non-selectivity, relatively large diameter pores and inactivation by external Ca2+ are reminiscent of the properties of hemi-gap-junctional channels that had been described in a variety of preparations (DeVries & Schwartz, 1992; Ebihara, Berthoud & Beyer, 1995; Trexler, Bennett, Bargiello & Verselis, 1996). Compelling evidence that the Ic is, in fact, mediated by the hemi-gap-junctional channel was provided by Ebihara (1996) with the demonstration that injection of oocytes with antisense oligonucleotides against the endogenous connexin 38 (Cx38) reduced Ic by more than 90 %. We have confirmed this result. Under our conditions we found Ic was reduced ∼80 % by Cx38 antisense injection (Fig. 7A and B). In addition, we demonstrated that the residual Ic current remaining after antisense injection showed an identical ion selectivity to the unblocked Ic in control oocytes (Fig. 7C). This observation is inconsistent with the possibility that the residual Ic reflects a subset of non-hemi-gap-junctional channels with differing ion selectivity.

Figure 7. The effect of injection of antisense against Cx38 on membrane conductance of Ic and the reversal potentials.

A, representative I–V relations measured in different oocytes (from the same donor) injected with antisense or scrambled antisense (control). B shows that the peak currents of Ic, measured when oocytes were voltage clamped at −40 mV, were significantly reduced in 5 antisense-injected oocytes compared with 3 scrambled antisense-injected oocytes (from 2 donors). C, shows that antisense injection does not change the ion selectivity of Ic compared with uninjected oocytes (17 oocytes from 1 donor for antisense, 8 oocytes from 2 donors for control). Solutions for A and B were Ca2+-free Ringer and for C Ca2+-free NaCl at the indicated concentrations.

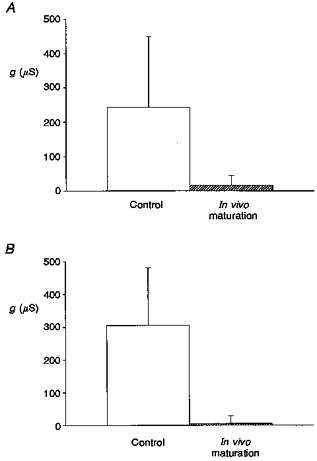

Ic is reduced in oocytes matured both in vitro and in vivo

Previous studies of the regulation of Ic before and after in vitro oocyte maturation have given somewhat variable results. Arellano et al. (1995) reported that Ic was down-regulated by as much as 90 % in oocytes matured by incubation in 10 μM progesterone for 4 h, while Weber et al. (1995b) reported that Ic was reduced approximately 30 % in oocytes matured by incubation in 0.1 μM progesterone for 6 h. Our results on the effects of maturation are indicated in Fig. 8. In addition to studying Ic in oocytes matured in vitro, we also studied the effects of in vivo maturation induced by preinjecting the female frog to induce ovulation and release of fully mature eggs. In summary, in in vitro matured eggs Ic conductance was reduced by 93 % from 243 to 16 μS, while the Ic conductance of in vivo matured eggs was reduced by 98 % from 304 to 5 μS. Our results clearly indicate that by the time the egg is released into the low-Ca2+ pond water, in which Ic could be activated, Ic has essentially disappeared and therefore would not compromise the viability of the egg or early embryo.

Figure 8. The effects of in vitro and in vivo maturation on Ic conductance.

A shows that in vitro maturation of oocytes by incubation in 10 μM progesterone for 12 h reduced Ic conductance by 93 % (21 control oocytes and 21 matured oocytes from 3 donor frogs). B shows that Ic conductance is reduced by 98 % in eggs matured in vivo (see Methods) compared with control immature oocytes which were treated with the same de-jellying protocol as the eggs (3 control oocytes from 1 donor frog, 5 de-jellied eggs from another frog).

DISCUSSION

In accessing the ion selectivity of Ic we chose a strategy in which reversal potential shifts were determined as a function of NaCl (KCl) concentration. This strategy is independent of assumptions regarding the impermeation of ion substitutes or the selectivity of cation versus anion channel blockers. However, it does require accurate measurement of true reversal potential shifts. In our preliminary experiments we used a conventional two-microelectrode voltage clamp but soon realized that reversal potential shifts had significant contributions from junction potential changes and electrode polarization effects. In hindsight, these contributions were not unexpected since there were drastic solution changes (i.e. 12 to 240 mM NaCl) and we often recorded very large currents (i.e. up to 10 μA). In order to minimize these errors, we adopted a three-microelectrode voltage-clamp arrangement in which the voltage was measured differentially across two high input impedance (3 M KCl filled) microelectrodes (one inside, the other outside the cell). This recording configuration essentially abolished junction potential changes and polarization effects.

The major result of our study is that the channels conducting Ic are mainly permeable to cations but also display an anion permeability. Previous studies have come to different conclusions regarding the ion selectivity of Ic. While one group concluded Ic is a cation-selective conductance (Arellano et al. 1995), another group concluded Ic is a Cl−-selective conductance (Weber et al. 1995a,b;Reifarth et al. 1997). In an attempt to reconcile these apparently conflicting results, we specifically tested the hypothesis that Ic is mediated by a population of two subsets of cation- and anion-selective channels. The variation in results could then arise if under different circumstances one subset dominated over the other or, as in our case, both subsets contributed.

As a first test of this hypothesis, we examined data from experiments carried over the course of a full year, thus allowing for possible seasonal variations, and specifically looked for large fluctuations in the permeability ratios. Our results indicate a K+:Na+:Cl− permeability ratio of 1:0.99:0.24, which was rather constant over this period. In particular, in no oocyte did the anion to cation permeability ratio approach, let alone exceed, 1. This constant permeability ratio is inconsistent with Ic being composed of cation- and anion-selective pores whose relative proportions can vary from one extreme to the other depending upon seasonal conditions.

More compelling evidence against the channel subset hypothesis is our finding that a variety of commonly used blockers of cation and anion channels block Ic without changing its reversal potential. The expected consequence of the subset channel hypothesis would be a shift in the Ic reversal potential as one subset was selectively blocked. Our observation of no shift in reversal potential argues against independent cation- and anion-selective channels since it would require all six agents to block the two subsets equally well. An alternative hypothesis is that Ic is mediated by a population of co-operative ‘double-barrelled’ cation and anion channels. However, this also seems unlikely since it would require that this wide variety of drugs act on a common gate controlling both pores. Although Ca2+, and possibly Gd3+, gates the Ic channel, it seems highly unlikely that amiloride, gentamicin, flufenamic acid and niflumic acid all inhibit Ic by blocking a common gate. Other evidence against double-barrelled selective pore, is our finding that even the largest organic ions tested were found to permeate the Ic conductance. This result implies that Ic pores are larger in diameter than would be expected for highly cation- or anion-selective channels (see Hille, 1992). These same arguments would seem to also rule out the idea that Ic arises through a cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-like modulation of different cation- and anion-selective channels.

The three major properties of the Ic conductance, namely its gating by external Ca2+, its relative non-selectivity for cations over anions and its permeability to large organic ions, are similar to the properties reported for hemi-gap-junctional channels in a variety of cell types (DeVries & Schwartz, 1992; Trexler et al. 1996). Although these similarities made us suspect that Ic channel may be the hemi-gap-junctional channel, it was Ebihara (1996) who, during the course of our experiments, reported the most compelling evidence for this identity. Specifically, she demonstrated that injection of the antisense to Cx38, which is endogenously expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Ebihara et al. 1989), could cause a 10-fold reduction in the Ic conductance while Cx38 overexpression could increase Ic by up to 4-fold (Ebihara, 1996). In this recent study, Ebihara did not address the issue of the ion selectivity of Ic but rather assumed, as in her previous studies of hemi-gap-junctional conductance, that the channel is either impermeable to anions or cannot distinguish between different anions (Ebihara et al. 1995). However, our study clearly indicates that Ic, and therefore presumably the Cx38 hemi-gap-junctional channel, has a significant anion permeability. This is consistent with previous studies on the permeability of other hemi-gap- and gap-junctional channels. For example, the relative Cl−/K+ permeability ratio of the Cx46 hemi-gap channel is ∼0.1 (Trexler et al. 1996). In the case of gap-junctional channels this ratio can vary between 0.12 and 1.17 (see Table 4 in Veenstra et al. 1995; Beblo & Veenstra, 1997; Wang & Veenstra, 1997). Since the amino acid sequence of many connexins is now known (Ebihara et al. 1989) and the topology is being elucidated (Zhou et al. 1997) it should be possible to predict the structural basis of these variations in anion permeability and test these predictions with site directed mutagenesis.

A number of different permeation models may explain how a single channel can pass both cations and anions. The simplest model is a neutral pore large enough to allow independent ion flow according to free solution mobility. However, the K+:Na+:Cl− mobility ratios are 1:0.68:1.04 which are different from our permeability ratios of 1:0.99:0.24. An addition to the simplest model is to assume negatively charged groups in the channel that will act to increase the concentration of cations without excluding anions (i.e. in the case of Ic by a factor of 4 to 1). Such a model, named ‘large channel theory’ (LCT) has been used to describe quantitatively the cation/anion permeability of the mitochondrial VDAC channel (Zambrowicz & Colombini, 1993). LCT assumes independent ion movement within two concentric regions of the channel pore: a central neutral core of bulk phase solution surrounded by an outer cylinder of solution adjacent to the channel walls. In LCT the relative size of the regions will depend upon permeant ion screening of charged channel sites such that at very low ion concentrations the central core will vanish and the channel should become more cation selective. An alternative model is one based on direct interactions between permeant cations and anions within the pore (Borisova, Brutyan & Ermishkin, 1986; Franciolini & Nonner, 1994). This type of model assumes that in order for an anion to permeate a cation channel, a cation must first enter and bind to a negative channel site thereby allowing an anion to enter and transiently form an ion complex with the bound cation. A consequence of this model that distinguishes it from LCT is that in the absence of permeant cations the channel should become impermeable to anions. Unfortunately, the lack of known impermeant cations (or anions) for the Ic (or gap junction) channel prevents this simple test for distinguishing between the two models (see also Wang & Veenstra, 1997; Beblo & Veenstra, 1997). On the other hand, a common feature of the ion-complex and LCT models is that the cation/anion permeability ratio varies with salt concentration. However, our observation that a single permeability ratio derived from the constant field equation fits the data, at least over the concentration range of 12–240 mM, seems inconsistent with both models.

Physiological role of Ic

The gap-junctional channel that interconnects the oocyte and follicular cells has been shown to be involved in a variety of signalling processes between the two cell types (Sandberg, Ji, Iida & Catt, 1992; Arellano & Miledi, 1995). However, the functional role of the hemi-gap-junctional conductance remains unclear, particularly since in vivo the immature oocyte is bathed in ∼2 mM Ca2+. On the other hand, Ic is not an artifact due to the splitting of gap junctions apart by defolliculation since we observe Ic of similar amplitude in folliculated and defolliculated oocytes. Instead, the hemi-gap channel proteins may serve as a readily available reservoir from which functional gap junctions can be formed with follicular cells (see also Li et al. 1996). In this regard, it is interesting that the downregulation in Ic expression seen in mature eggs corresponds with the loss of the follicular cell layer during in vivo egg maturation. Furthermore, the downregulation of Ic and the presence of the egg jelly coat, which tends to maintain Ca2+ levels near the membrane (Ishihara, Hosono, Kanatani & Katagiri, 1984), would act together to minimize Ic conductance and thus any possible toxic effects this conductance could have on eggs when they are released into low-Ca2+ pond water.

Comparison of Ic with Cao2+-masked conductances reported in other cell types

A wide variety of cell types respond to the removal of extracellular Ca2+ by a large increase in non-selective cation conductance (see Introduction for references). In the past, two general explanations have been put forward to account for this phenomenon. One proposes that the removal of extracellular Ca2+ alters the ion selectivity of voltage gated Ca2+ or K+ channels (e.g. see Almers et al. 1984; Armstrong & Miller, 1990). The other proposes that removal of Ca2+ unmasks a novel cation channel (e.g. Van Driessche et al. 1988; Mubagwa et al. 1997). This study indicates that a third possible explanation may contribute to this phenomenon, namely activation of hemi-gap-junctional channels. This would seem plausible given the wide distribution of gap junctions in different cells including epithelia, endothelia, cardiac, smooth and skeletal muscle, neurons, and even lymphocytes (Bruzzone, White & Paul, 1996; Krenacs, Van Dartel, Lindhout & Rosendaal, 1997). It may be that these other cell types have hemi-gap protein reservoirs in their plasma membrane similar to that seen in the oocyte. In this case the removal of external divalents would activate the channels. An initial test for this possibility will be to look for mixed anion/cation permeability of the Cao2+-sensitive conductance in these tissues.

In conclusion, our results indicate that Ic in Xenopus oocytes is mediated by a single population of non-selective, large diameter pores that are subject to block by a variety of drugs and are most likely to represent the endogenous hemi-gap-junctional channel. In terms of previously conflicting reports regarding the ion selectivity of the Ic conductance, we rule out the channel subset hypothesis as an explanation but, unfortunately, we cannot provide a complete explanation for all the discrepancies between the groups and in some cases discrepancies arising within a single group (Weber et al. 1995a;Reifarth et al. 1997). However, the very nature of the hemi-gap-junctional channel complicates the use of impermeant ion substitutes and selective drug block as criteria for distinguishing cation- and anion-selective channels

Acknowledgments

Our research is supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (Grant RO1-AR42782) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

APPENDIX

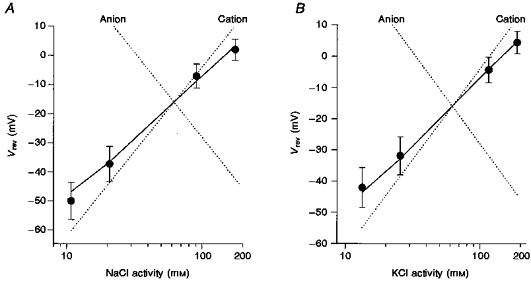

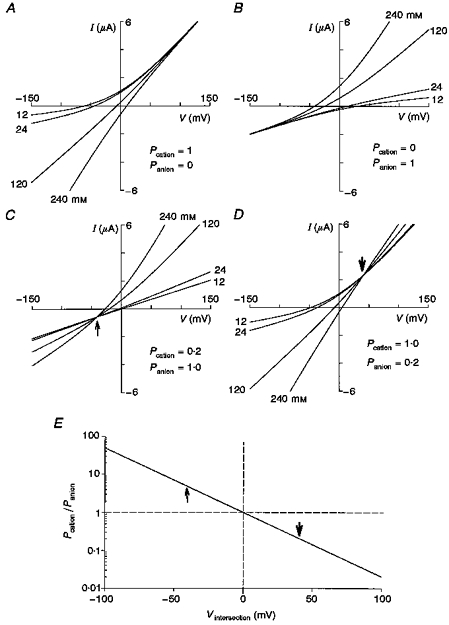

The purpose of this appendix is to illustrate how a mixed cation/anion conductance displays a specific feature in its instantaneous I–V relations measured as a function of salt concentration, namely, a common intersection point. The presence of an intersection gives an immediate indication of a mixed cation/anion permeability. Furthermore, it can be used in conjunction with the commonly measured reversal potential shifts to determine quantitatively the cation/anion permeability ratio. An additional advantage of measuring the entire instantaneous I–V relation as a function of external ion concentrations (e.g. NaCl or KCl), instead of just the reversal potential, is that it does not require any assumptions regarding the impermeability to cation or anion substitutes. Figure 9 shows constant field predictions for different ion-selective conductances. The I–V relations of ideally cation-selective (Fig. 9A) and anion-selective (Fig. 9B) channels will tend to approach limiting conductances (i.e. asymptote) at large positive and negative potentials, respectively. The asymptotic behaviour arises because at the extremes only the intracellular permeant ions contribute to the current. In contrast, conductances that are permeable to both cations and anions will not show asymptotic behaviour but instead display I–V relations that intersect. The intersection occurs because ions in both the extracellular and intracellular solutions always contribute to the current. A conductance that is more selective for anions (Fig. 9C) will show an intersection in the third quadrant whereas a conductance which is more cation selective (Fig. 9D) will show an intersection in the first quadrant. A completely non-selective channel will display an intersect at 0 mV. This intersection behaviour can be quantitatively predicted by the constant field current equation.

Figure 9. Theoretical predictions from the constant field equation for I–V curves with different external salt concentrations and ion selectivities.

The graphs show theoretical predictions for a pure cation-selective (A), a pure anion-selective (B), a partially cation-selective (C) and a partially anion-selective (D) membrane conductance. E, predicted behaviour of the I–V intersection voltage as a function of the anion/cation permeability ratio. In these calculations (A-D), the intracellular permeant ion concentrations were assumed to be 110 mM for K+, 6 mM for Na+ and 33 mM for Cl−.

From examination and rearrangement of equations (2), (3) and (4), it can be seen that the membrane current becomes independent of external ion concentrations when:

| (7) |

This also corresponds to the point at which the influxes of external cations and anions are equal. If the external permeant cation concentration is equal to the external permeant anion concentration, then eqn (7) can be simplified to β = PA/PC, which means the permeability ratio of anion and cation will determine where the I–V curves intersect. Figure 9E shows the anion/cation permeability ratio plotted as a function of the intersection voltage, assuming the external permeant cation and anion activities are equal. This figure indicates that if there is no intersection within ±60 mV then the cation and anion permeabilities differ by a factor of 10 or more.

References

- Almers W, McCleskey EW, Palade PT. A non-selective cation conductance in frog muscle membrane blocked by micromolar external calcium ions. The Journal of Physiology. 1984;353:565–583. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano RO, Miledi R. Functional role of follicular cells in the generation of osmolarity-dependent Cl− currents in Xenopus follicles. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:351–357. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano RO, Woodward RM, Miledi R. A monovalent cationic conductance that is blocked by extracellular divalent cations in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;484:593–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CM, Miller C. Do voltage-dependent K+ channels require Ca2+? A critical test employing a heterologous expression system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1990;87:7579–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beblo DA, Veenstra RD. Monovalent cation permeation through the connexin−40 gap junctional channel CS, Rb, K, Na, Li, TEA, TMA, TBA, and effects of anions Br, Cl, F, acetate, aspartate, glutamate, and NO3. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:509–522. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisova MP, Brutyan RA, Ermishkin LN. Mechanism of anion-cation selectivity of amphotericin B channels. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1986;90:13–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01869681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, White TW, Paul DL. Connections with connexins: the molecular basis of direct intercellular signaling. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1996;238:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0001q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N. The use of Xenopus oocytes for the study of ion channels. CRC Critical Review in Biochemistry. 1987;22:317–387. doi: 10.3109/10409238709086960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries SH, Schwartz EA. Hemi-gap-junction channels in solitary horizontal cells of the catfish retina. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;445:201–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara L. Xenopus connexin38 forms hemi-gap-junctional channels in the nonjunctional plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:742–748. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79273-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara L, Berthoud VM, Beyer EC. Distinct behavior of connexin56 and connexin46 gap-junctional channels can be predicted from the behavior of their hemi-gap-junctional channels. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:1796–1803. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara L, Beyer EC, Swenson KI, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Cloning and expression of a Xenopus embryonic gap junction protein. Science. 1989;243:1194–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.2466337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciolini F, Nonner W. A multi-ion permeation mechanism in background chloride channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:725–746. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.4.725. 10.1085/jgp.104.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Cahalan MD. Divalent ion trapping inside potassium channels of human T lymphocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;93:609–630. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.4.609. 10.1085/jgp.93.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Ono K, Noma A. A sustained inward current activated at the diastolic potential range in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;483:1–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm DR, Frizzell RA. Anion permeation in an apical membrane chloride channel of a secretory epithelial cell. Journal of General Physiology. 1992;99:339–366. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.3.339. 10.1085/jgp.99.3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr Rapid adaptation of single mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:7462–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacological Reviews. 1996;48:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K, Hosono J, Kanatani H, Katagiri CH. Toad egg-jelly as a source of divalent cations essential for fertilization. Developmental Biology. 1984;105:435–442. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenacs T, Van Dartel M, Lindhout E, Rosendaal M. Direct cell/cell communication in the lymphoid germinal center: connexin43 gap junctions functionally couple follicular dendritic cells to each other and to B lymphocytes. European Journal of Immunology. 1997;27:1489–1497. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Liu T-F, Lazrak A, Peracchia C, Goldberg GS, Lampe PD, Johnson RG. Properties and regulation of gap junctional hemichannels in the plasma membranes of cultured cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134:1019–1030. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.1019. 10.1083/jcb.134.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay LL, Hedrick JL. Proteases released from Xenopus laevis eggs at activation and their role in envelope conversion. Developmental Biology. 1989;135:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S. The electrostatic properties of membranes. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biophysical Chemistry. 1989;18:113–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.000553. 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubagwa K, Stengl M, Flameng W. Extracellular divalent cations block a cation non-selective conductance unrelated to calcium channels in rat cardiac muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:235–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.235bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappone PA, Lee SC. Alpha-adrenergic stimulation activates a calcium-sensitive chloride current in brown fat cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;106:231–258. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.231. 10.1085/jgp.106.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifarth FW, Amasheh S, Clauss W, Weber WM. The Ca2+-inactivated Cl− channel at work: selectivity, blocker kinetics and transport visualization. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;155:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s002329900161. 10.1007/s002329900161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RA, Stokes RH. Electrolyte Solutions. New York: Academic Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg K, Ji H, Iida T, Catt KJ. Intercellular communication between follicular angiotensin receptors and Xenopus laevis oocytes: mediation by an inositol 1,4,4-trisphosphate-dependent mechanism. Journal of Cell Biology. 1992;117:157–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.1.157. 10.1083/jcb.117.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stühmer W. Electrophysiological recording from Xenopus oocytes. Methods in Enzymology. 1992;207:319–339. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trexler RB, Bennett MVL, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. Voltage gating and permeation in a gap junction hemichannel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:5836–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5836. 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupper JT, Maloff BL. The ionic permeability of the amphibian oocyte in the presence or absence of external calcium. Experimental Zoology. 1973;185:133–144. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401850113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Driessche W, Simaels J, Aelvoet I, Erlij D. Cation-selective channels in amphibian epithelia: electrophysiological properties and activation. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1988;90A:693–699. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(88)90686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra RD, Wang H-Z, Beblo DA, Chilton MG, Harris AL, Beyer EC, Brink PR. Selectivity of connexin-specific gap junctions does not correlate with channel conductance. Circulation Research. 1995;77:1156–1165. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H-Z, Veenstra RD. Monovalent ion selectivity sequences of the rat connexin43 gap junctional channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:491–507. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.491. 10.1085/jgp.109.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber WM, Liebold KM, Reifarth FW, Uhr U, Clauss W. Influence of extracellular Ca2+ on endogenous Cl− channel in Xenopus oocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 1995a;429:820–824. doi: 10.1007/BF00374806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber WM, Liebold KM, Reifarth FW, Clauss W. The Ca2+-induced leak current in Xenopus oocytes is indeed mediated through a Cl− channel. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995b;148:263–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00235044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrowicz EW, Colombini M. Zero current potentials in a large membrane channel: a simple theory accounts for complex behavior. Biophysical Journal. 1993;65:1093–1100. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81148-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, McBride DW, Hamill OP. Ion selectivity of a membrane conductance activated by removal of extracellular calcium in Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:A272. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.763bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X-W, Pfahnl A, Werner R, Hudder A, Llanes A, Luebke A, Dahl G. Identification of a pore lining segment in gap junction hemichannels. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:1946–1953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78840-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]