Abstract

CPI-17 has recently been identified as a novel protein in vascular smooth muscle. In vitro, its phosphorylation and thiophosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC) specifically inhibits the type 1 class of protein phosphatases, including myosin light chain (MLC) phosphatase.

Both of the phosphorylated CPI-17 states dose-dependently potentiated submaximal contractions at constant [Ca2+] in β-escin-permeabilized and Triton X-100-demembranated arterial smooth muscle, but produced no effect in intact and less intensely permeabilized (α-toxin) tissue. Thiophosphorylated CPI-17 (tp-CPI) induced large contractions even under Ca2+-free conditions and decreased Ca2+ EC50 by more than an order of magnitude. Unphosphorylated CPI-17 produced minimal but significant effects.

tp-CPI substantially increased the steady-state MLC phosphorylation to Ca2+ ratios in β-escin preparations.

tp-CPI affected the kinetics of contraction and relaxation and of MLC phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in such a manner that indicates its major physiological effect is to inhibit MLC phosphatase.

Results from use of specific inhibitors in concurrence with tp-CPI repudiate the involvement of general G proteins, rho A or PKC itself in the Ca2+ sensitization by tp-CPI.

Our results indicate that phosphorylation of CPI-17 by PKC stimulates binding of CPI-17 to and subsequent inhibition of MLC phosphatase. This implies that CPI-17 accounts largely for the heretofore unknown signalling pathway between PKC and inhibited MLC phosphatase.

Regulation of the reversible Ser-19 phosphorylation of 20 kDa myosin light chain (MLC) primarily governs the extent of smooth muscle contraction (Hartshorne, 1987; Kamm & Stull, 1989). Although a rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+ acts as the main triggering mechanism for phosphorylating MLC, by activating Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent MLC kinase (MLCK), most well-known, physiological membrane and cytosolic receptor ligands, such as the catecholamines and nitrovasodilators, exert their effect in large part by dynamically changing the Ca2+ sensitivity of MLC phosphorylation and contractile force (Somlyo & Somlyo, 1994; Kitazawa, Gaznabi & Murahashi, 1995). Catecholamines and other excitatory agonists of the large membrane G protein-linked receptors, as well as GTPγS itself, inhibit MLC phosphatase (MLCP), thereby effecting an increase in the Ca2+ sensitivity of MLC phosphorylation and contractile force (Kitazawa, Masuo & Somlyo, 1991b;Kubota, Nomura, Kamm, Mumby & Stull 1992). Rho kinase, which is activated by the small cytosolic G protein rho A, appears to inhibit MLCP as well (Hirata et al. 1992; Kimura et al. 1996); whether this small G protein pathway parallels or lies downstream of the large membrane G protein pathway remains unknown. Yet another excitatory cytosolic signalling pathway, the activation of protein kinase C (PKC) by phorbol esters and diacylglycerol (DAG), also dictates an inhibition of MLCP (Itoh etal. 1993; Masuo, Reardon, Ikebe & Kitazawa, 1994), although there are several reports showing that phorbol ester-induced contractile Ca2+ sensitization can occur without an increase in MLC phosphorylation (see review by Walsh, Andrea, Allen, Clement-Chomienne, Collins & Morgan, 1994). One familiar intracellular second messenger, arachidonic acid has multiple stimulatory effects: direct inhibition of MLCP (Gong et al. 1992b), activation of an endogenous kinase associated with MLCP (Ichikawa, Ito & Hartshorne, 1996) and possibly of atypical PKCζ (Gailly, Gong, Somlyo & Somlyo, 1997). In contrast, cyclic GMP, second messenger of the nitrovasodilator and other vasodilatory signal transduction pathways, activates the MLCP and causes a resultant decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity, probably through protein kinase G (PKG) (Lee, Li & Kitazawa, 1997). Each of the known Ca2+ sensitivity regulators share one common feature, their ability to modulate Ca2+ sensitivity of MLC phosphorylation and contraction by affecting MLCP activity. The precise mechanisms of MLCP modulation as well as a complete list of the mediators in each of the various known pathways, however, are unknown.

Eto, Ohmori, Suzuki, Furuya & Morita (1995) reported seeing direct in vitro phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of protein phosphatase type 1 (PP1) in porcine aorta by a novel heat-stable protein termed CPI-17. The group later cloned and sequenced CPI-17 to show that its primary 147 amino acid sequence (molecular mass, 17 kDa) is distinct from those of other proteins including all other known inhibitor proteins and PP1 subunits (Eto, Senba, Morita & Yazawa, 1997). In addition to structural differences, CPI-17 functions differently from the other PP1 inhibitors, such as inhibitor-1. Phosphorylated CPI-17 rapidly inhibits both the catalytic subunit and the holoenzyme of MLCP with similar high potency (Eto et al. 1995) while the presence of regulatory subunit(s) significantly inhibited actions of the other PP1 inhibitor proteins (Alessi, MacDougall, Sola, Ikebe & Cohen, 1992; Mitsui, Inagaki & Ikebe, 1992; Gong et al. 1992a). Additionally, PKC, but not PKA, can phosphorylate at Thr-38 only and thereby activate CPI-17 (Eto et al. 1995), whereas PKA, but not PKC, activates inhibitor-1 by phosphorylation (see Cohen, 1989). Furthermore, Northern blot hybridization analysis revealed that CPI-17 differs from the other PP1 inhibitor proteins in tissue specificity: CPI-17 mRNA is almost exclusively expressed in smooth muscle (Eto et al. 1997), while Western blot analyses show that inhibitors-1 and-2 are distributed in various tissues (Cohen, 1989) and another inhibitor protein dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-32 (DARPP-32) is specifically seen in brain (Hemmings, Nairn & Greengard, 1984). In summary, CPI-17 appears to differ from the other PP1 inhibitors in its effect on the holoenzyme, in its activation and in its tissue localization.

We believe that CPI-17 might provide a mutual convergent point at which the various smooth muscle pathways could meet. In the previous in vitro experiments (Eto et al. 1995), however, the MLCP used was comprised of only two components, a 37 kDa catalytic subunit and a 69 kDa non-catalytic subunit which appears to be a proteolytic fragment of the 110 or 130 kDa regulatory subunit; furthermore, a 21 kDa subunit was missing (see Johnson, Cohen, Chen, Chen & Cohen, 1997). We seek, therefore, in this study to determine whether CPI-17, when phosphorylated by PKC, inhibits the physiological in situ MLCP holoenzyme associated with myofilaments to increase Ca2+ sensitivities of both MLC phosphorylation and contractile force. A part of these findings has been presented at the Annual Biophysical Society Meeting (Kitazawa, Lee, Li & Eto, 1997).

METHODS

Tissue preparation and force measurement

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Georgetown University. Male New Zealand White rabbits (2.5–3 kg) were killed by inhalation of halothane and exsanguinated. Smooth muscle strips (70 μm thick, 700–800 μm wide and 3 mm long) were dissected from femoral arteries, carefully freed of connective tissue and the endothelia removed by rubbing with a razor blade. The strips were then tied with silk monofilaments and suspended between the fine tips of two tungsten needles, one of which was connected to a force transducer (AM801; SensoNor, Horten, Norway). They were submersed in convex globules of solution over a mixing well on a Teflon bubble plate to allow for moderately rapid (within 1 s) solution exchange and freezing (Kitazawa, Gaylinn, Denney & Somlyo, 1991a). Experiments were carried out at 20°C.

The standard relaxing solution, used for resting states of the permeabilized strips contained the following: 74.1 mM potassium methanesulphonate, 2 mM Mg2+, 4.5 mM MgATP, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 30 mM Pipes, 1 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT) and 0.1 % fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA). Sometimes we used slightly modified relaxing solutions (as indicated), in which the concentration of EGTA was different. In the activating solution, 10 mM EGTA was used and a calculated amount of calcium methanesulphonate was added to give the final desired concentration of free Ca2+ ions (Kitazawa et al. 1991a). All solutions were neutralized to pH 7.1 with KOH at 20°C and an ionic strength of 0.2 M was achieved by using more or less potassium methanesulphonate as appropriate.

Cell permeabilization

After measuring the force of contractions induced by high [K+] (154 mM) and phenylephrine (100 μM) in freshly dissected strips, these strips were incubated in the standard relaxing solution for several minutes. For plasma membrane permeabilization with β-escin, the strips were then treated with 80 μM (except 60 μM in Fig. 5) in standard relaxing solution for 45 min at 5°C and then for 20 min at 30°C in the presence of 10 μM A23187, a Ca2+ ionophore (Masuo et al. 1994). For another plasma membrane permeabilization with α-toxin, the strips were then treated for 30 min at 30°C with 5000 units ml−1 of purified Staphylococcus aureusα-toxin (Gibco) at pCa 6.7, buffered with 10 mM EGTA and then with A23187 for 20 min (Masuo et al. 1994). To heavily permeabilize strips, we used 0.1 % Triton X-100 in standard relaxing solution for 30 min at 5°C and for 15 min at 30°C (Lee et al. 1997).

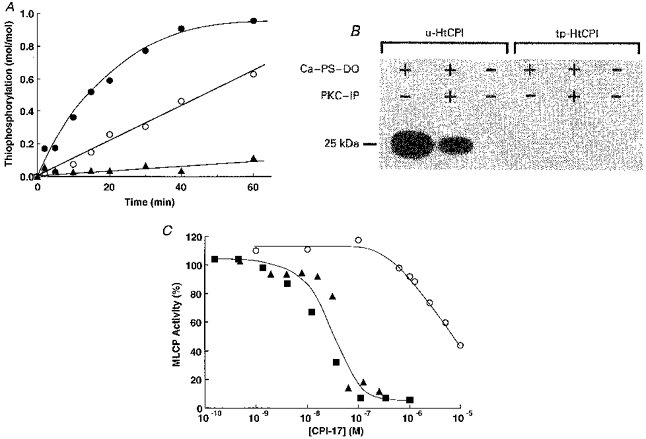

Figure 5. Effect of the presence of GDPβS, PKC pseudosubstrate inhibitor peptide (19–31) or C3 exoenzyme pretreatment on tp-HtCPI-induced Ca2+ sensitization at pCa 6.3.

All arterial strips used in Fig. 5 were permeabilized with 60 μM β-escin for 45 min at 5 °C and then for 15 min at 30 °C in the presence of 10 μM A23187. A, control without any inhibitors. tp-HtCPI (5 μM) markedly increased force levels at pCa 6.3 from 4 ± 1 to 72 ± 3 % of maximum at pCa 4.5. B, presence of 2 mM GDPβS did not affect the tp-HtCPI-induced force whereas it blocked 30 μM phenylephrine (PE) + 10 μM GTP-induced increase in force at pCa 6.3. C, presence of 30 μM PKC pseudosubstrate inhibitor peptide (PKC-IP) markedly inhibited phorbol ester (3 μM, PDBu)-induced force development, but did not inhibit the tp-HtCPI-induced contraction. D, permeabilized strips were first incubated for 60 min at 20 °C in a relaxing solution containing 30 μM β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), 2 mM thymidine and 0.3 μM calmodulin in the presence and absence of 1 μg ml−1Clostridium botulinum exoenzyme C3 (Calbiochem). The C3 pretreatment caused an inhibition of PE + GTP-induced Ca2+ sensitization at pCa 6.3, but had no significant effect on the action of tp-HtCPI.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

For measuring MLC phosphorylation, permeabilized preparations were rapidly frozen with liquid N2-cooled liquid chlorodifluoromethane under the desired conditions, with force monitored up to the time of freezing. The various phosphorylated states of MLC, un-(U), mono-(P1) and di-(P2) phosphorylated, were separated by a two-dimensional isoelectric focusing SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, stained with colloidal gold to produce separate spots for each phosphorylated state, and the amount at each spot was measured by its density (Kitazawa et al. 1991a). The percentage of MLC phosphorylation was calculated by dividing (P1 + P2) by (U + P1 + P2).

Proteins

The native CPI-17 of porcine aorta smooth muscle was isolated as described previously (Eto et al. 1995). The recombinant hexahistidine-tagged CPI-17 (HtCPI) was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) which was transformed with the expression vector of the pHtCPI plasmid, and purified to homogeneity by heat treatment, Ni2+-chelating Sepharose and Sephacryl S-200 column chromatographies (Eto et al. 1997). MLCP was prepared from porcine aorta smooth muscle (Eto et al. 1995). This preparation was characterized as a PP1 holoenzyme comprised of a 69 kDa non-catalytic subunit and a 37 kDa PP1-catalytic subunit which alone is classified as the delta isoform which dephosphorylates both MLC and myosin (Eto et al. 1995). MLC (20 kDa) was prepared from chicken gizzard, myosin from porcine aorta and PKC from porcine brain as described previously (Eto et al. 1997). Phosphorylation and thiophosphorylation of native and recombinant CPI-17 was carried out using porcine brain PKC in the presence of 0.1 mM ATP and 1 mM ATPγS, respectively, with 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 20 μg ml−1 phosphatidylserine, 2 μg ml−1 diolein, and 50 mM Mops, adjusted to pH 7.2, at 30°C. After incubation in boiling water for 5 min, the thiophosphorylated CPI-17 was purified by Mono S 5/5 or Sephadex G-50 column chromatographies (Eto et al. 1997). The extent of phosphorylation of CPI-17 was determined from the ratio of the band intensities of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated CPI-17 on the urea-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 (Eto et al. 1997).

Statistics

All values are expressed as means ±s.e.m. of n experiments. Student's unpaired two-tailed t test was used for statistical analysis of the data and P values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Thiophosphorylation of CPI-17 by PKC

Since thiophosphorylation of proteins unlike regular phosphorylation is highly resistant to protein phosphatases (Sherry, Gorecka, Aksoy, Dabrowska & Hartshorne, 1978), we mainly used the thiophosphorylated form of CPI-17 in determining the effects of the active protein on the regulatory and/or contractile apparatuses including protein phosphatases. Porcine brain PKC slowly thiophosphorylated native (Eto et al. 1995) and recombinant hexahistidine-tagged CPI-17 (HtCPI) using ATPγS as a substrate to a maximal extent of 1.0 mole of Pi per mole of HtCPI (Fig. 1A). The rate of thiophosphorylation, like regular phosphorylation by PKC, depended on the concentrations of Ca2+ and phospholipid and was reduced to half by the presence of 5 μM PKC pseudosubstrate inhibitor peptide (19–31) that corresponds to the pseudosubstrate region of Ca2+-dependent PKC isoforms (House & Kemp, 1987).

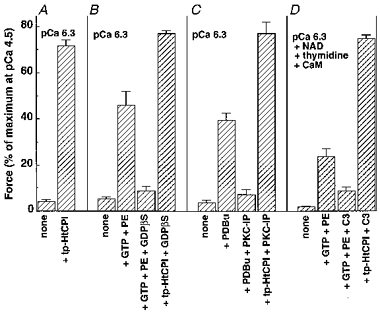

Figure 1. In vitro characterization of CPI-17.

A, thiophosphorylation of HtCPI was initiated by adding 1 mM ATPγS to a pH 7.2 solution containing 26 mU ml−1 PKC, 10 μM HtCPI, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM benzamidine, and 50 mM Mops in the presence of either a set of PKC activators (0.2 mM CaCl2+ 20 μg ml−1 phosphatidylserine + 2 μg ml−1 diolein) (•), the PKC activator set plus 5 μM PKC pseudosubstrate inhibitor peptide (19–31) (○), or 1 mM EGTA alone (▴). One unit of PKC was defined as the amount of the enzyme catalysing phosphorylation of 1 nmol MLC in 1 min. At the indicated time, an aliquot was taken out and mixed with solid urea to terminate the reaction. The extent of HtCPI thiophosphorylation was determined from the band intensities of both unphosphorylated (u-) and thiophosphorylated (tp-) HtCPI on the Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained urea-PAGE gel. B, the 32P-autoradiograph from standard phosphorylation of two HtCPI forms was initiated by adding 0.1 mM [γ-32P]ATP instead of ATPγS to the same solutions as in A, but with 2 μM u-or tp-HtCPI instead of 10 μM HtCPI. Ca-PS-DO represents the solution that contained 0.2 mM CaCl2, 20 μg ml−1 phosphatidylserine and 2 μg ml−1 diolein; PKC-IP indicates 5 μM PKC pseudosubstrate inhibitor peptide. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 % SDS, and then the sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE. The 32P-labelled HtCPI on the gel was visualized on a Fujix Bas 2000 imaging analyser. In the SDS-PAGE, due to the high basicity (theoretical isoelectric point, 10.3), the native (16.7 kDa) or recombinant hexahistidine-tagged protein (21.5 kDa) migrates to a position corresponding to 20 or 25 kDa, respectively. C, dose-response relations of CPI-17 on isolated MLCP: MLCP activities were measured after 8 min in a pH 7.2 solution containing 0.1 mg ml−1 phosphorylated MLC, 0.1 μg ml−1 MLCP, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.1 mg ml−1 BSA and 50 mM MOPS at 25 °C in the presence of either tp-HtCPI (▪), tp-CPI (▴), or u-HtCPI (○). The reaction was initiated by the addition of MLCP, and was terminated by the addition of solid urea. The extent of dephosphorylated MLC was determined by means of urea-PAGE.

To examine whether or not the thiophosphorylation site of HtCPI differs from the site normally phosphorylated (Thr-38; Eto et al. 1997), the maximally thiophosphorylated HtCPI (tp-HtCPI) was further exposed to PKC but in the presence of regular [γ-32P] ATP. In the control experiments, unphosphorylated HtCPI (u-HtCPI) was naturally phosphorylated with the extent depending on the presence of activators or inhibitor (Fig. 1B). The thiophosphorylated did not, however, accept further phosphorylation by PKC using the regular, labelled ATP, suggesting that the same site(s) accepts phosphorylation or thiophosphorylation. Figure 1C shows that the inhibitory activity of tp-HtCPI towards porcine aorta MLCP was equivalent to those of thiophosphorylated native CPI-17 (tp-CPI) and regularly phosphorylated HtCPI (not shown), but much higher than that of u-HtCPI. Similar inhibitory efficacy of tp-HtCPI was also observed using crude MLCP in diluted porcine aorta homogenates instead of purified MLCP. Thus thiophosphorylation works well to mimic standard phosphorylation in CPI-17 activation.

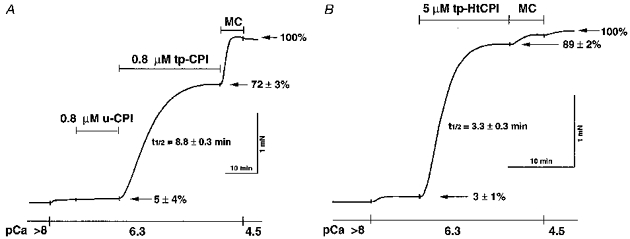

Contractile Ca2+ sensitization

CPI-17 when thiophosphorylated by PKC elicits definitive Ca2+ sensitization of contractile force in the β-escin arterial preparations (Fig. 2) but has no such sensitizing effects on intact and α-toxin preparations (not shown). The pores formed by α-toxin in the plasma membrane appear to be too small for the protein to pass through (Kitazawa et al. 1991a) and a solution of used protein vehicle seems to have neither intra-nor extracellular effects on force levels. In the experiments shown by Fig. 2, a constant Ca2+ level (pCa 6.3) alone produced minimal force development in β-escin-treated strips which did not improve in the presence of u-CPI. Thiophosphorylated native (tp-CPI in Fig. 2A) and recombinant CPI-17 (tp-HtCPI in Fig. 2B) forms, unambiguously augmented the force levels under conditions otherwise identical to those used with u-CPI. Addition of microcystin-LR (MC), a protein phosphatase type 1-and 2A-specific inhibitor (MacKintosh, Beattie, Klumpp, Cohen & Codd 1990; Gong et al. 1992a), in high concentration (10 μM) brought the level of contraction up to a value equivalent to the maximum induced by pCa 4.5. Regularly phosphorylated HtCPI at 10 μM also potentiated pCa 6.3-induced submaximal contractions from 7 ± 3 to 41 ± 2 % of maximum, but this was significantly lower than the levels evoked by tp-HtCPI at 5 μM (not shown). Due to the limited source of native protein and the comparable effects of the recombinant hexahistidine-tagged form, we used mostly the latter for the remaining experiments.

Figure 2. Efficacy of PKC-thiophosphorylated native, unphosphorylated native (A) and PKC-thiophosphorylated recombinant CPI-17 (B) at constant Ca2+ in permeabilized arterial smooth muscle.

Strips of rabbit femoral artery were permeabilized with 80 μM β-escin and then incubated in the standard relaxing solution (see Methods). They were placed in a pCa 6.3 solution until reaching a low steady-state level of force at 20 °C. Native CPI-17 (u-CPI and tp-CPI) (A) or recombinant CPI-17 (tp-HtCPI) (B) was added into the same pCa 6.3 solution with final (supramaximal) concentrations of 0.8 μM in A and 5 μM in B. After a steady-state level of force was reached, CPI-17 was washed out and a high concentration (10 μM) of the Leu-Arg analogue of microcystin (microcystin-LR, MC) was applied to completely inhibit MLCP in the permeabilized tissue. To verify maximum force levels, the last solution contained pCa 4.5. These traces are representative of the two experiments, each of which was repeated four times.

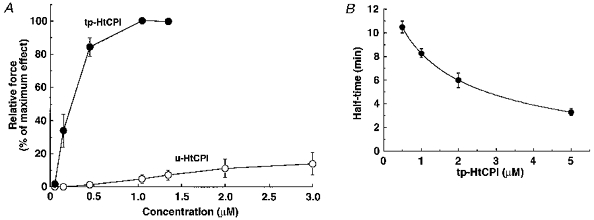

Dose-response relations of tp-CPI (not shown) and tp-HtCPI (Fig. 3A) on the steady-state, pCa 6.3-induced contractile force levels reveal the maximal efficacy and high potency of the thiophosphorylated proteins (native and recombinant) in exerting their sensitizing effects on force. The EC50 was 102 ± 19 nM for tp-CPI (not shown) and 230 ± 51 nM for tp-HtCPI (Fig. 3A) while both unphosphorylated native and recombinant CPI-17 had much lesser effects on contraction, even in the micromolar range. The half-time (t½) of force development varied inversely with the concentration of thiophosphorylated protein (Fig. 3B). High concentrations (5–10 μM) of tp-HtCPI also eliminated a delay in the onset of force development.

Figure 3. Dose-response relations of tp-HtCPI (•) and u-HtCPI (○) on steady-state levels of contractile force (A) and dose-response relation of tp-HtCPI on the half-time of force development (B).

A, CPI-17 concentration was cumulatively increased in the pCa 6.3 solution. Steady-state values were measured as a percentage of the maximum effect at 1.35 μM tp-HtCPI (n = 4). B, a single dose of tp-HtCPI was added to each strip in the pCa 6.3 solution at 20 °C (n = 4).

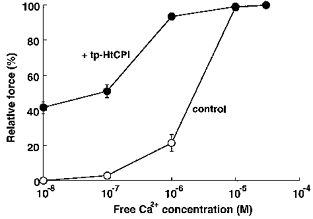

A more comprehensive and conclusive display of sensitizing effects can be best appreciated over a range of buffered Ca2+ levels (Fig. 4). A supramaximal level of tp-HtCPI (5 μM) effects not only a parallel shift to the left of steady-state levels but also an increase in the basal force under lower Ca2+ levels (pCa 8) than that found in resting in vivo smooth muscle. EC50 of Ca2+ was decreased by more than an order of magnitude. The same concentration of the protein, however, did not affect the maximal force steady state at pCa 4.5.

Figure 4. Efficacy of 5 μM tp-HtCPI on Ca2+ dose-response relations of contractile force.

Relative force was measured once steady-state levels were achieved in the absence (○, control) and presence (•) of tp-HtCPI as Ca2+ was increased stepwise (n = 4).

In the separate experiments using demembranated strips (Triton X-100 treatment), 10 μM tp-HtCPI rapidly (without delay in the time resolution used in this study) potentiated submaximal steady-state contractions (pCa 6.0 with 0.1 μM calmodulin) to a maximum steady state that could not be further increased by 10 μM MC or by pCa 5 alone. Even in Ca2+-free solutions containing 10 mM EGTA, 10 μM tp-HtCPI alone generated near maximal levels (about 79 % of maximum) of force, while u-HtCPI had virtually no effect.

The presence of a general G protein inhibitor, GDPβS (2 mM), completely prevented α1-agonist phenylephrine-induced contractile Ca2+ sensitization at pCa 6.3 (Fig. 5B;Kitazawa et al. 1991a). A PKC pseudosubstrate inhibitor peptide (19–31) at 30 μM blocked phorbol ester (PDBu)-induced potentiation of contraction at constant Ca2+ (Fig. 5C;Yoshida, Suzuki & Itoh, 1994; Gaznabi, Fujita, Murahashi & Kitazawa, 1995). A specific, small G protein (rho A)-inhibiting C3 exoenzyme pretreatment also largely, but not completely prevented phenylephrine plus GTP-induced Ca2+ sensitization in rabbit femoral artery (Fig. 5D;Fujita, Takeuchi, Nakajima, Nishio & Hata, 1995; Kokubu, Satoh & Takayanagi, 1995; Gong et al. 1996; Otto, Steusloff, Just, Aktories & Pfitzer, 1996). Neither GDPβS, C3 exoenzyme, nor PKC inhibitor peptide, however, was able to antagonize the Ca2+ sensitization induced by 5 μM tp-HtCPI (Fig. 5).

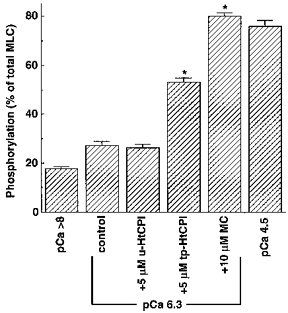

Ca2+ sensitization of MLC phosphorylation

Figure 6 shows the relationship between pCa and MLC phosphorylation in β-escin-permeabilized arterial smooth muscle and the effect of HtCPI on this relationship. An increase in Ca2+ from pCa > 8 to 6.3 caused a slight but significant elevation of MLC phosphorylation. tp-HtCPI (5 μM) further increased MLC phosphorylation at constant pCa 6.3 considerably, while unphosphorylated protein did not cause any change. Addition of 10 μM MC augmented the level of MLC phosphorylation to a value equivalent to the maximum induced by pCa 4.5. In a different series of experiments (not shown), addition of 0.8 μM tp-CPI (the native form) to the pCa 6.3 solution significantly increased phosphorylation from 24 ± 2 to 34 ± 3 % of total MLC, again qualitatively similar to the effect of tp-HtCPI. In no cases were phosphorylation levels at pCa 4.5 enhanced.

Figure 6. Effect of 5 μM tp-HtCPI or u-HtCPI on MLC phosphorylation at a constant Ca2+.

After permeabilization, strips were incubated in the standard relaxing solution at least for 10 min at 20 °C. They were frozen after being partially activated by pCa 6.3 alone for 15 min (control) or after pCa 6.3 for 10 min followed by 5 μM u-HtCPI, 5 μM tp-HtCPI or 10 μM MC for another 5 min in the pCa 6.3 solution. The fully activated samples were frozen 5 min after activation by pCa 4.5. Frozen samples were processed for measurement of MLC phosphorylation according to the procedure described in the Methods. *P < 0.001. n = 4–5.

MLCP activity was inhibited

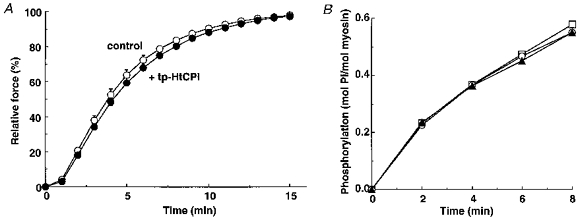

We tested whether phosphorylated CPI-17 increases MLC phosphorylation through activation of MLCK or inhibition of the MLCP in permeabilized smooth muscle. β-escin permeabilized strips, upon the addition of 10 μM MC at pCa 6.3, attained steady-state levels of force and phosphorylation that did not increase further when the Ca2+ concentration in the fibres was increased to a maximal pCa 4.5 (Figs 2 and 6), indicating that MC at 10 μM abolishes in situ MLCP activity (Gong et al. 1992b). tp-HtCPI (10 μM) did not affect the steady-state levels of, nor the rate of rise for, contractions in the pCa 6.7 solution containing 10 μM MC (Fig. 7A). The same concentration of either u-or tp-HtCPI also failed to affect the time course of phosphorylation of myosin by isolated smooth muscle MLCK (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Effects of 10 μM tp-HtCPI on the time course of force development at pCa 6.7 without MLCP activity (A) and on the time course of MLC phosphorylation by isolated MLCK in vitro (B).

A, to estimate on-rate kinetics of in situ MLC phosphorylation, individual strips permeabilized with β-escin were first depleted of ATP by washing three times in 1 mM EGTA rigor solution for 30 min and further pretreated with 10 μM MC in 0.1 mM EGTA rigor solution with or without 10 μM tp-HtCPI for 20 min, and then set in pCa 6.7 (10 mM EGTA) activating solution with MC in the absence (○) or presence (•) of tp-HtCPI (n = 3–4). B, the MLCK activity was measured at pH 7.2 and 25 °C with 2 μM porcine aorta myosin, 1 μg ml−1 chicken gizzard MLCK, 10 μg ml−1 calmodulin, 0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM [γ-32P]ATP and 50 mM Mops-NaOH in the presence of 10 μM u-HtCPI (○) or tp-HtCPI (▴) or neither (□).

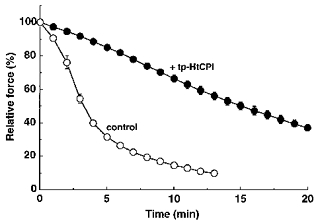

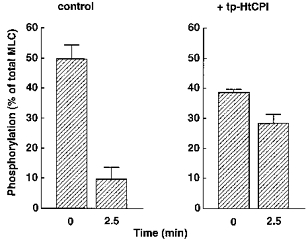

To evaluate in situ MLCP activity, we used 200 μM of the MLCK inhibitor ML-9 (Saitoh, Ishikawa, Matsushima, Naka & Hidaka, 1987) together with a Ca2+-free (10 mM EGTA) solution to rapidly block MLCK activity after a submaximal contraction and then to induce prompt relaxation and dephosphorylation of near-maximal contractions. The rates of relaxation and dephosphorylation represent, to a reasonable extent, reliable approximations to MLCP activity (Masuo et al. 1994; Lee et al. 1997). Application for 15 min of pCa 5.7 alone and pCa 6.3 plus 10 μM tp-HtCPI produced near-maximal levels of contraction (92 ± 0.7 % and 78 ± 2.4 % of maximum at pCa 4.5, respectively), from which to start the experiments. The strips were immersed in the Ca2+-free, ML-9-containing solution ± 10 μM tp-HtCPI to monitor the rates of relaxation and dephosphorylation. tp-HtCPI decreased the rates of relaxation (Fig. 8) and dephosphorylation (Fig. 9) in a pronounced fashion. The average t½ for relaxation was greatly increased by the thiophosphorylated protein from 3.2 ± 0.1 to 15.1 ± 0.9 min. Two and a half minutes after MLCK was blocked, MLC phosphorylation without tp-HtCPI was reduced by 81 % of the starting level and ultimately returned all the way to the basal level (see the value at pCa < 8 in Fig. 6); at the same 2.5 min mark, the presence of 10 μM tp-HtCPI meant that phosphorylation was reduced by only 26 %.

Figure 8. Effect of 10 μM tp-HtCPI on the time course of force relaxation without MLCK activity: indirect off-rate kinetics.

For control experiments (○), each strip was contracted by pCa 5.7 for 15 min and then relaxed by 200 μM ML-9 in 10 mM EGTA relaxing solution. For test experiments (•), individual strips were first contracted by pCa 6.3 alone for 5 min and further stimulated with 10 μM tp-HtCPI for additional 15 min and then relaxed by ML-9 in the relaxing solution containing tp-HtCPI. Relative force was expressed as a percentage of the force level at 0 min in the ML-9 relaxing solution; 100 % relative force corresponds to 92 ± 0.7 % of maximal force at pCa 4.5 for control and 78 ± 2.4 % for tp-HtCPI (n = 4). Values are expressed as means ±s.e.m. (n = 3).

Figure 9. Effect of 10 μM tp-HtCPI on MLC dephosphorylation without MLCK activity: direct off-rate kinetics.

MLC phosphorylation was measured when each strip was frozen at either 0 and 2.5 min during the relaxation under the same conditions as in Fig. 7. n = 4.

DISCUSSION

The major finding in this study is that PKC-phosphorylated CPI-17 can sensitize in situ smooth muscle contraction in response to Ca2+ through inhibiting dephosphorylation of MLC, but not through activating the phosphorylation. The increase in force evoked by phosphorylated CPI-17 at constant Ca2+ concentration occurred concomitantly with an increase in steady-state MLC phosphorylation. Even when MLCK activity was blocked, a state that allows for study of phosphorylation off-rate kinetics alone, marked reductions in the dephosphorylation and relaxation rates were observed in the presence of phosphorylated CPI-17. When MLCP activity was blocked, a state that allows for study of phosphorylation on-rate kinetics alone, we did not find any significant effect from CPI-17 on force development. We confirmed this result using isolated proteins that neither phosphorylated nor unphosphorylated CPI-17 had an effect on in vitro MLCK activity. All together, these findings strongly support the conclusion that CPI-17 slows the off-rate with little effect on the on-rate of MLC phosphorylation.

More specifically, the Ca2+ sensitization by phosphorylated CPI-17 appears to be achieved by its direct inhibition of the MLCP associated with myofilaments. First, removal of membrane structure and soluble proteins by the non-ionic detergent Triton X-100 did not inhibit, but rather accelerated the development of contraction induced by the protein. This extensive disruption of membrane integrity effects near-total loss of soluble cytosolic macromolecules, hence CPI-17 probably acted directly on the regulatory contractile machinery. Secondly, activation of either the GTP-rho A-rho kinase or the DAG-PKC pathway is known to inhibit MLCP activity and consequently increase both Ca2+ sensitivities of MLC phosphorylation and contractile force (Itoh et al. 1993; Masuo et al. 1994; Kimura et al. 1996; Gong et al. 1996). However, these pathways when activated by GTP and DAG and even by the active form of exogenous PKC or rho A are roughly abolished by treatment with Triton X-100 or high concentrations of saponin (Kitazawa et al. 1991b; Masuo et al. 1994; Gong et al. 1996), perhaps due to the loss of intermediary molecules, quite possibly including CPI-17 and rho kinase. Our results reveal no significant effect of GDPβS, PKC inhibitor peptide or C3 exoenzyme treatment on the action of CPI-17, thus supporting our conclusion that CPI-17 does not appear to act through any of these other excitatory pathways and may lie downstream of them; this would also corroborate, along with the Triton X-100 results, our firm belief that CPI-17 directly inhibits the in situ MLCP holoenzyme, which is in agreement with its inhibition of the (37 kDa + 69 kDa) MLCP apoenzyme in vitro.

It is noteworthy that phosphorylated CPI-17 generated substantial levels of force in the absence of Ca2+. Likewise, GTPγS (Kitazawa et al. 1991a), PDBu (Masuo et al. 1994) and protein phosphatase inhibitors (Gong et al. 1992a), which are all known to inhibit MLCP, all increase the basal force. The GTPγS-and phosphatase inhibitor-induced increases in basal force are associated with an increase in MLC phosphorylation, suggesting the presence of basally active in situ protein kinase(s) toward MLC in the absence of Ca2+. The presence of such a protein kinase(s) has already been suggested (Kitazawa et al. 1991b; Gong et al. 1992a) and at least one kinase (rho-kinase) has been recently identified (Amano et al. 1996; Kureishi et al. 1997).

The slow affect of phosphorylated CPI-17 on the contractility of β-escin-permeabilized smooth muscle strips may be of slight concern. However, it probably stems from a slow diffusion of the protein into the cells. The diffusion rate of the substance across the membrane depends on the concentration gradient and the permeability coefficient. Increasing the CPI-17 concentration over the saturated concentration and hence the concentration gradient effected an increased rate of rise in contractile force (Fig. 3B). Demembranation with Triton X-100, which increases the permeability coefficient, also caused faster development of contraction than did the β-escin permeabilization on strips of the same size. Thus, in these separate experiments, changing factors that directly increased the diffusion rate of CPI-17 were each associated with a more rapid CPI-17 effect with a minimal delay.

The in situ EC50 of thiophosphorylated CPI-17 was about 0.1–0.2 μM, much higher than that of the in vitro value (30 nM). The high concentrations of the inhibitor required for the Ca2+ sensitization may be due to the much higher in situ concentration (0.7 μM) of MLCP (Alessi et al. 1992) than those in the in vitro experiments (approximately 1 nM in this study) and from the existence of other types of PP1 phosphatases which would increase the EC50 of CPI-17 inhibiting MLCP.

Physiological smooth muscle MLCP, which is associated with the myofibrils and dephosphorylates myosin as well as MLC, falls in the type 1 class of protein phosphatases (PP1) (Alessi et al. 1992; Mitsui et al. 1992; Gong et al. 1992a) and is composed of a 37 kDa catalytic subunit and two other proteins with molecular weights of 110–130 kDa and 21 kDa (Johnson et al. 1997). PP1-specific inhibitor proteins in their active states potently and almost instantaneously inhibit the activity of the PP1 catalytic subunit. The holoenzymes of PP1, however, are inhibited only after long (20 min) preincubation with high concentration of inhibitor proteins (Alessi et al. 1992; Mitsui et al. 1992). As mentioned in the Introduction, CPI-17 rapidly inhibited porcine aorta MLCP ‘holoenzyme’ although the preparations were composed of only the 37 kDa catalytic subunit and the 69 kDa non-catalytic, presumably proteolytic, fragment of the 110–130 kDa subunit (Eto et al. 1995). The possibility that the intact MLCP holoenzyme might reduce the activity of CPI-17 thus remained to be solved. This study has clearly demonstrated that the novel PP1 inhibitor protein CPI-17, unlike other PP1 inhibitor proteins, potently and rapidly inhibits the physiological MLCP holoenzyme in both β-escin-and Triton X-100-permeabilized arterial smooth muscle. In contrast to the other PP1 inhibitors, the novel PP1 inhibitor protein CPI-17 is activated through phosphorylation by PKC, but not by PKA, Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMK II) or MLCK (Eto et al. 1995). Contrary to PKA and PKG activators, PKC activators increase Ca2+ sensitivities of both MLC phosphorylation and contractile force through inhibition of MLCP, but via unknown mediator(s) (Masuo et al. 1994); PKC activation might also relieve the phosphorylation-independent inhibition of contraction by calponin or caldesmon; the so-called thin filament disinhibition (Winder & Walsh, 1993; Rokolya, Ahn, Moreland, van Breemen & Moreland, 1994; Horowitz, Clementchomienne, Walsh, Tao, Katsuyama & Morgan, 1996). In agreement with the knowledge of PKC activators, PKC-phosphorylated CPI-17 potently increased both MLC phosphorylation and force and decreased MLC dephosphorylation and relaxation (this study). All these results fit the idea that CPI-17 is a physiological mediator between PKC and MLCP in smooth muscle.

Interestingly, three independent mechanisms for the Ca2+-sensitization of MLC phosphorylation and contractile force are associated directly with the regulation of MLCP. The first involves the GTP-bound form of a small G protein, rho A p21, that activates a novel kinase (rho kinase) which then phosphorylates a 130 kDa regulatory subunit of smooth muscle MLCP and thereby inhibits the catalytic activity (Kimura et al. 1996). Another involves arachidonic acid, whereby the second messenger directly interacts with and causes dissociation of the MLCP holoenzyme to inhibit its activity (Gong et al. 1992b) although this messenger has been reported to have multiple actions. The third mechanism is the PKC activation by phorbol ester or DAG, which may phosphorylate the novel inhibitor protein CPI-17, thereby directly inhibiting the MLCP catalytic subunit (Masuo et al. 1994; this study). The question as to what extent CPI-17 is phosphorylated in situ when PKC and the other pathways are activated remains to be determined. In conclusion, CPI-17, a new type 1 protein phosphatase inhibitory protein isolated from mammalian smooth muscle, is phosphorylated by PKC in vitro, but not by PKA, CaMK II or MLCK. This protein phosphorylation-dependently increases Ca2+ sensitivity of MLC phosphorylation and contraction in situ through inhibition of MLCP. These results strongly suggest that CPI-17 largely mediates the known PKC stimulatory effect to induce phosphorylation-dependent contractile Ca2+ sensitization in smooth muscle.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant HL51824 to T. K.

References

- Alessi D, MacDougall LK, Sola MM, Ikebe M, Cohen P. The control of protein phosphatase-1 by targetting subunits: The major myosin phosphatase in avian smooth muscle is a novel form of protein phosphatase-1. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1992;210:1023–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. The structure and regulation of protein phosphatases. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto M, Ohmori T, Suzuki M, Furuya K, Morita F. A novel protein phosphatase-1 inhibitory protein potentiated by protein kinase C. Isolation from porcine aorta media and characterization. Journal of Biochemistry. 1995;118:1104–1107. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto M, Senba S, Morita F, Yazawa M. Molecular cloning of a novel phosphorylation-dependent inhibitory protein of protein phosphatase-1 (CPI17) in smooth muscle: Its specific location in smooth muscle. FEBS Letters. 1997;410:356–360. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00657-1. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00657-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita A, Takeuchi T, Nakajima H, Nishio H, Hata F. Involvement of heterotrimeric GTP-binding protein and rho protein, but not protein kinase C, in agonist-induced Ca2+ sensitization of skinned muscle of guinea pig vas deferens. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1995;274:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailly P, Gong MC, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Possible role of atypical protein kinase C activated by arachidonic acid in Ca2+ sensitization of rabbit smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:95–109. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaznabi AKM, Fujita A, Murahashi T, Kitazawa T. Role of PKC activation in agonist-G protein mediated Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contraction. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:A217. [Google Scholar]

- Gong MC, Cohen P, Kitazawa T, Ikebe M, Masuo M, Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Myosin light chain phosphatase activities and the effects of phosphatase inhibitors in tonic and phasic smooth muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992a;267:14662–14668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong MC, Fuglsang A, Alessi D, Kobayashi S, Cohen P, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Arachidonic acid inhibits myosin light chain phosphatase and sensitizes smooth muscle to calcium. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992b;267:21492–21498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong MC, Iizuka K, Nixon G, Browne JP, Hall A, Eccleston JF, Sugai M, Kobayashi S, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Role of guanine nucleotide-binding proteins ras-family or trimeric proteins or both in Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:1340–1345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1340. 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne DJ. Biochemistry of the contractile process in smooth muscle. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. New York: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 423–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings HC, Jr, Nairn AC, Greengard P. DARPP-32, a dopamine-and adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-regulated neuronal phosphoprotein. II. Comparison of the kinetics of phosphorylation of DARPP-32 and phosphatase inhibitor 1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259:14491–14497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata K, Kikuchi A, Sasaki T, Kuroda S, Kaibuchi K, Matsuura Y, Seki H, Saida K, Takai Y. Involvement of rho p21 in the GTP-enhanced calcium ion sensitivity of smooth muscle contraction. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:8719–8722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Clementchomienne O, Walsh MP, Tao T, Katsuyama H, Morgan KG. Effects of calponin on force generation by single smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:H1858–1863. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House C, Kemp BE. Protein kinase C contains a pseudosubstrate prototope in its regulatory domain. Science. 1987;238:1726–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.3686012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa K, Ito M, Hartshorne DJ. Phosphorylation of the large subunit of myosin phosphatase and inhibition of phosphatase activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:4733–4740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4733. 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Shimomura A, Okubo S, Ichikawa K, Ito M, Konishi T, Nakano T. Inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase during Ca2+-independent vasocontraction. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:C1319–1324. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.5.C1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D, Cohen P, Chen MX, Chen YH, Cohen PTW. Identification of the regions on the M(110) subunit of protein phosphatase 1 M that interact with the M(21) subunit and with myosin. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;244:931–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00931.x. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm KE, Stull JT. Regulation of smooth muscle contractile elements by second messengers. Annual Review of Physiology. 1989;51:299–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.001503. 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Ito M, Amano M, Chihara K, Fukata Y, Nakafuku M, Yamamori B, Feng JH, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Science. 1996;273:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Gaylinn BD, Denney GH, Somlyo AP. G-protein-mediated Ca2+-sensitization of smooth muscle contraction through myosin light chain phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991a;266:1708–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Gaznabi AKM, Murahashi T. Regulation of Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle contraction by myosin light chain phosphatase. In: Maruyama K, Nonomura Y, Kohama K, editors. Calcium as Cell Signal. Tokyo: Igakushoin Ltd; 1995. pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Lee MR, Li L, Eto M. Phosphorylated CPI-17, a new phosphatase inhibitory protein, increases smooth muscle contraction. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:A177. [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Masuo M, Somlyo AP. G protein-mediated inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase in vascular smooth muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991b;88:9307–9310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokubu K, Satoh M, Takayanagi I. Involvement of botulinum C-3-sensitive GTP-binding proteins in alpha(1)-adrenoceptor subtypes mediating Ca2+-sensitization. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;290:19–27. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90012-8. 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Nomura M, Kamm KE, Mumby MC, Stull JT. GTPγS-dependent regulation of smooth muscle contractile elements. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:C405–410. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.2.C405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kureishi Y, Kobayashi S, Amano H, Kimura K, Kanaide H, Nakano T, Kaibuchi K, Ito M. Rho-associated kinase directly induces smooth muscle contraction through myosin light chain phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:12257–12260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12257. 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Li L, Kitazawa T. Cyclic GMP causes Ca2+ desensitization in vascular smooth muscle by activating the myosin light chain phosphatase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:5063–5068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5063. 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKintosh C, Beattie KA, Klumpp S, Cohen P, Codd GA. Cyanobacterial microcystin-LR is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A from both mammals and higher plants. FEBS Letters. 1990;264:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80245-e. 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80245-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuo M, Reardon S, Ikebe M, Kitazawa T. A novel mechanism for the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of protein kinase C on vascular smooth muscle: Inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:265–286. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.2.265. 10.1085/jgp.104.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui T, Inagaki M, Ikebe M. Purification and characterization of smooth muscle myosin-associated phosphatase from chicken gizzards. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:16727–16735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto B, Steusloff A, Just I, Aktories K, Pfitzer G. Role of Rho proteins in carbachol-induced contractions in intact and permeabilized guinea-pig intestinal smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:317–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokolya A, Ahn Y, Moreland S, van Breemen C, Moreland RS. A hypothesis for the mechanism of receptor and G-protein-dependent enhancement of vascular smooth muscle myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. Canadian The Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1994;72:1420–1426. doi: 10.1139/y94-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh M, Ishikawa T, Matsushima S, Naka M, Hidaka H. Selective inhibition of catalytic activity of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:7796–7801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry JM, Gorecka A, Aksoy MO, Dabrowska R, Hartshorne DJ. Roles of calcium and phosphorylation in the regulation of the activity of gizzard myosin. Biochemistry. 1978;17:4411–4418. doi: 10.1021/bi00614a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature. 1994;372:231–236. doi: 10.1038/372231a0. 10.1038/372231a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh MP, Andrea JE, Allen B, Clement-Chomienne O, Collins EM, Morgan K. Smooth muscle protein kinase C. Canadian The Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1994;72:1392–1399. doi: 10.1139/y94-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder SJ, Walsh MP. Calponin—thin filament-linked regulation of smooth muscle contraction. Cellular Signalling. 1993;5:677–686. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(93)90029-l. 10.1016/0898-6568(93)90029-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Suzuki A, Itoh T. Mechanisms of vasoconstriction induced by endothelin-1 in smooth muscle of rabbit mesenteric artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;477:253–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]