Abstract

Earlier studies have shown that Fe2+ transport into erythroid cells is inhibited by several transition metals (Mn2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Ni2+) and that Fe2+ transport can occur by two saturable mechanisms, one of high affinity and the other of low affinity. Also, the transport of Zn2+ and Cd2+ into erythroid cells is stimulated by NaHCO3 and NaSCN. The aim of the present investigation was to determine whether all of these transition metals can be transported by the processes described for Fe2+, Zn2+ and Cd2+ and to determine the properties of the transport processes.

Rabbit reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes and reticulocytes from homozygous and heterozygous Belgrade rats were incubated with radiolabelled samples of the metals under conditions known to be optimal for high- and low-affinity Fe2+ transport and for the processes mediated by NaHCO3 and NaSCN.

All of the metals were transported by the high- and low-affinity Fe2+ transport processes and could compete with each other for transport. The Km and Vmax values and the effects of incubation temperature and metabolic inhibitors were similar for all the metals. NaHCO3 and NaSCN increased the uptake of Zn2+ and Cd2+ but not the other metals.

The uptake of all of the metals by the high-affinity process was much lower in reticulocytes from homozygous Belgrade rats than in those from heterozygous animals, but there was no difference with respect to low-affinity transport.

It is concluded that the high- and low-affinity ‘iron’ transport mechanisms can also transport several other transition metals and should therefore be considered as general transition metal carriers.

Immature erythroid cells have a very high capacity for iron uptake and incorporation into haemoglobin. In humans and other mammals about 80 % of the plasma iron turnover is directed to these cells and about 70 % of total body iron is contained within mature, circulating erythrocytes (Baker & Morgan, 1994). Reticulocytes, which are a circulating form of immature erythroid cells, retain the ability to take up iron and utilize it for haemoglobin synthesis and provide an excellent model for studying the mechanisms involved in iron assimilation by cells. With their use it was first shown that iron uptake occurs by endocytosis of the transferrin- iron complex. Subsequently, a similar process was identified in nucleated erythroid cells of the bone marrow and many other types of cells (Morgan, 1996a). Following endocytosis the iron is released from transferrin within the endosomes and is then transported across the endosomal membrane into the cytosol. How iron crosses this and other cellular membranes is the least understood step in the iron uptake process.

Studies with reticulocytes and non-transferrin-bound iron have helped to characterize the mechanisms involved in iron transport across erythroid cell membranes. There is good evidence for the presence of at least two transport processes (Morgan, 1988; Hodgson, Quail & Morgan, 1995; Savigni & Morgan, 1996). One, called high-affinity transport (Hodgson et al. 1995), is present in reticulocytes but not in mature erythrocytes, and can be studied most conveniently by incubating reticulocytes with ferrous iron, Fe(II), in low ionic strength media such as isotonic sucrose. The second mechanism, low-affinity transport (Hodgson et al. 1995), does not disappear when reticulocytes mature and is most active when extracellular NaCl is replaced by KCl or other non-sodium alkali metal salts such as RbCl or CsCl. Both transport mechanisms show Michaelis-Menten kinetics but with different Km values, approximately 0.2 and 15 μM Fe(II) for the high- and low-affinity mechanisms, respectively. Both are inhibited by other transition metals, such as Mn2+, Zn2+, Co2+ and Ni2+ (Morgan, 1988; Stonell, Savigni & Morgan, 1996) and, in the case of Mn2+, there is strong evidence for uptake by erythroid cells by the same mechanisms which transport iron (Chua, Stonell, Savigni & Morgan, 1996). These observations suggest that other transition metals, in addition to manganese, can be transported into erythroid cells by the iron transport mechanisms and may compete with iron for these mechanisms.

The aim of this work was to investigate the above possibility with respect to the transmembrane transport of Fe2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Zn2+ and Cd2+ and so to characterize the mechanisms involved in the transport of all of these metals into erythroid cells. Most of the experiments were performed with rabbit reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes under conditions which are optimal for the uptake of Fe2+ by the high- and low-affinity transport processes. In addition, for specific purposes some studies utilized rat cells or alternative incubation conditions.

METHODS

Materials

The radioisotopes Na125I, 57CoCl2, 63NiCl2, 65ZnCl2 and 109CdCl2 were purchased from Amersham Australia (Sydney, NSW, Australia) and 59FeCl3 and 54MnCl2 from Dupont (Sydney, Australia). The biochemical reagents were from Sigma Chemical Co.

Cells

Reticulocyte-rich blood was obtained from rabbits and heterozygous Belgrade rats with phenylhydrazine-induced haemolytic anaemia (Hemmaplardh & Morgan, 1974; Bowen & Morgan, 1987), 4–6 days after the last dose of phenylhydrazine. Blood was also obtained from homozygous Belgrade rats which have an endogenous reticulocytosis. Blood with a low reticulocyte count was obtained from untreated rabbits and untreated heterozygous Belgrade rats. The Belgrade rat has an anaemia which is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait (Sladic-Simic, Zivkovic, Pavic, Markinkovic, Martinovic & Martinovitch, 1966). The anaemia of homozygous Belgrade rats (b/b) is of the iron deficiency type due primarily to defective iron transport through the membrane of endosomes into the cytosol after receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin-bound iron (Bowen & Morgan, 1987). Heterozygous Belgrade rats (+/b) do not have anaemia or any evidence of impaired iron metabolism. The rabbit blood was obtained by incision of a marginal ear vein without anaesthesia and the rat blood by heart puncture under 5 % halothane anaesthesia.

The blood cells were washed three times with ice-cold 0.155 M NaCl and then centrifuged at a packed cell volume (PCV) of approximately 70 % for 30 min at 2500 g. With reticulocyte-rich blood the top one-quarter of the resultant red cell layer was removed, washed twice in the desired incubation solution and suspended at a PCV of approximately 30 %. These cells had a reticulocyte count of 40–80 %, and will be referred to as reticulocytes. With non-anaemic blood the bottom one-quarter of the cells was removed and treated as for reticulocytes. These cells will be referred to as erythrocytes and had a reticulocyte count of 1–5 %. With both types of cells the buffy coat was removed from the red cell layer after each centrifugation.

Incubation procedure

The incubation procedure was essentially the same as described earlier (Chua et al. 1996). Usually, samples of the cell suspensions (usually 100 μl) were incubated in an oscillating, temperature-controlled water bath in 2 ml of the incubation solutions containing radiolabelled divalent sulphate (Fe, Co) or chloride (Mn, Ni, Zn, Cd) salts of the metals. Most incubations were performed at 37°C and for 15 min since, in preliminary experiments using concentrations of 1 and 20 μM, it was found that uptake of the metals by the cells was linear for at least 30 min. Hence, under these conditions, the results obtained with a 15 min incubation represent the rate of metal uptake. However, when concentrations less than 1 μM were used the incubations were performed in 4 ml solution for 10 min since at the lowest concentrations used a linear rate of uptake was maintained only for 10–15 min. Three basic incubation media were used, but were modified in certain experiments as described below. These media were 0.155 M NaCl, pH 7.4; 0.155 M KCl, pH 7.0; and 0.27 M sucrose, pH 6.5 or 7.0. The osmolarity of each solution was 290 ± 5 mosmol kg−1 and the medium was buffered with 4 mM Tris-Hepes to the required pH.

The solutions of the transferrin-free metal salts were prepared immediately before use by mixing samples of the radioisotopes with the non-radioactive salts and diluting with 0.27 M sucrose to give solutions with at least twenty times the desired final concentrations of the metals. Aliquots of the radiolabelled solutions were then added to the cell suspensions, mixed and incubation commenced. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold 155 mM NaCl, haemolysed with 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, centrifuged to separate cytosol and stromal fractions and counted for radioactivity.

The results in the tables are presented as means ±s.e.m. Significance of differences between the means (P < 0.05) was assessed using Student's t test. The results in the figures are from experiments which were repeated two to four times, with similar results.

Analytical methods

The PCV was measured by the microhaematocrit method and the reticulocyte count by staining with New Methylene Blue (Sigma). The radioactivity of 63Ni2+ was counted in a Beckman LS 6500 liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA) and the other isotopes in a three-channel γ-scintillation counter (1282 Compugamma; LKB Wallac, Sweden). Osmolarity was determined by measurement of freezing point depression (One-Ten Osmometer; Fiske, Needham Heights, MA, USA).

RESULTS

Incubation conditions

Based on the results of previous investigations on the transport of non-transferrin-bound iron (Morgan, 1988; Quail & Morgan, 1994; Hodgson, Quail & Morgan, 1995) and manganese (Chua et al. 1996) into rabbit erythroid cells, three basic incubation media were chosen for the present studies, viz. isotonic NaCl, KCl and sucrose. Also, two different metal concentrations, 1 and 20 μM, were used in order to distinguish between high- and low-affinity transport mechanisms. In preliminary studies it was found that transport into the cells was affected by the pH of the media, maximal rates occurring at pH 6.5 with 1 μM metal concentrations and the sucrose medium and at pH 7.0 with 1 and 20 μM concentrations in KCl and with 20 μM in sucrose. There was no distinct pH optimum when NaCl solution was used as the incubation medium. Hence, in all subsequent incubations sucrose solutions were buffered at pH 6.5 when 1 μM concentrations were used and at pH 7.0 for 20 μM concentrations, and KCl solutions were buffered at pH 7.0. A pH of 7.4 was chosen for incubations in NaCl, since this pH has been used in most previous investigations in which NaCl-based media were used.

Rates of metal transport

The results for the uptake of the metals into the cytosolic fraction of the cells, using the above incubation conditions, are summarized in Table 1. With reticulocytes and 1 μM concentration of the metals the rate of uptake was much greater when the sucrose solution was used than with NaCl, and the results with KCl were intermediate between the two sets of values, with the exception of Ni2+, which showed greater uptake with KCl than with sucrose. Generally, the rates of uptake of the different metals in each of the incubation solutions were similar, the only statistically significant exceptions to this being lower values for Ni2+ with sucrose, and higher values for Zn2+ and Cd2+ with NaCl, than for the other metals. When the concentration of the metals was 20 μM the uptake from NaCl was again much lower than from KCl or sucrose but, with the exception of Cd2+, uptake was greater with KCl than with sucrose. The uptake rates of each of the metals under the three incubation conditions were similar, with the exceptions of considerably lower values for Ni2+ with KCl and Cd2+ with sucrose and higher values for Zn2+ and Cd2+ when the incubations were performed in NaCl solution.

Table 1.

Rate of transition metal uptake (nmol (ml cells)−1 min−1) to the cytosol of reticulocytes and erythrocytes

| Fe2+ | Mn2+ | Co2+ | Zn2+ | Cd2+ | Ni2+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reticulocytes | ||||||

| 1 μm metal | ||||||

| Sucrose | 1.06 ± 0.13 | 1.51 ± 0.21 | 1.13 ± 0.10 | 1.22 ± 0.13 | 1.49 ± 0.16 | 0.27 ± 0.02 * |

| KCl | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.005 * | 0.38 ± 0.04 |

| NaCl | 0.035 ± 0.009 | 0.028 ± 0.008 | 0.036 ± 0.008 | 0.082 ± 0.010 * | 0.15 ± 0.02 * | 0.040 ± 0.003 |

| 20 μm metal | ||||||

| Sucrose | 8.1 ± 1.0 | 11.8 ± 1.8 | 7.1 ± 0.51 | 9.9 ± 0.82 | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 2.0 ± 0.24 * |

| KCl | 11.8 ± 0.72 | 13.5 ± 0.77 | 11.5 ± 0.61 | 12.1 ± 0.64 | 3.3 ± 0.24 * | 7.6 ± 0.60 * |

| NaCl | 0.51 ± 0.14 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 0.26 ± 0.022 | 1.9 ± 0.18 * | 1.5 ± 0.14 * | 0.23 ± 0.072 * |

| Erythrocytes | ||||||

| 1 μm metal | ||||||

| Sucrose | 0.10 ± 0.005 | 0.10 ± 0.003 | 0.08 ± 0.024 | 0.20 ± 0.028 | 0.28 ± 0.030 | 0.048 ± 0.009 |

| 20 μm metal | ||||||

| KCl | 6.3 ± 0.38 | 6.2 ± 0.43 | 5.0 ± 0.55 | 5.9 ± 0.19 | 1.8 ± 0.48 * | 2.73 ± 0.60 * |

The cells were incubated with 1 or 20 μM concentrations of the metals in isotonic sucrose (1 μm, pH 6.5; 20 μm, pH 7.0), KCl (pH 7.0) or NaCl (pH 7.4). Each value is the mean ±s.e.m. of 10–15 measurements with reticulocytes and 8–10 measurements with erythrocytes.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) from the value for Fe2+.

Measurements of uptake by erythrocytes were restricted to 1 μM concentration in sucrose solution and 20 μM in KCl solution (Table 1). The rates of uptake from sucrose were all extremely low, only 7–18 % as great as the results for reticulocytes with each of the metals. With KCl the uptake by erythrocytes was also lower than by reticulocytes but, in this case, the erythrocyte values were 35–55 % of those with reticulocytes.

Measurements of metal uptake to the stromal or membrane fraction of the cells were also made. The values so obtained were 7–85 % as great as for uptake to the cytosol, depending on the type of incubation condition, cell and metal. In the control incubations the mean values for the proportion of uptake to the stroma was greater for Fe2+, Ni2+ and Cd2+ than for the other metals, and greater for the incubations in sucrose (26–61 %) than in the other media (13–33 %). Higher values than these were obtained when the cells were incubated with reagents or competitors which inhibited metal uptake because uptake to the cytosol was inhibited to a greater degree than uptake to the stroma although some inhibition of stromal uptake did occur in most instances. However, since the aim of this investigation was to study transport across the cell membrane into the cytosol, and for simplicity of presentation, only the results for transport into the cytosol will be presented.

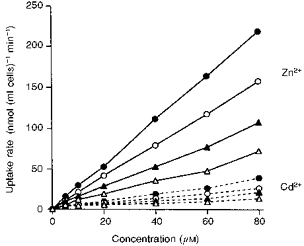

Concentration dependence of transport

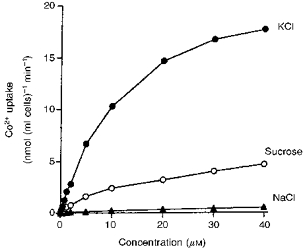

The rate of metal uptake was determined using cells incubated in NaCl, sucrose or KCl in the presence of varying concentrations of the metals. With NaCl the uptake increased linearly with increasing concentration up to at least 40 μM as shown, in Fig. 1 for Co2+. With sucrose the uptake curve showed two components, one which appeared to saturate at about 1 μM concentration and a second low-affinity or non-specific component which did not saturate within the concentrations used. These uptake curves were analysed by a non-linear, least square curve-fitting program (SigmaPlot; Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA, USA) in order to determine the maximum rates of uptake (Vmax) and Michaelis-Menten constants (Km) for the saturable component of the uptake curves. The lowest Km and highest Vmax values were found for Cd2+ transport and the highest Km and lowest Vmax for Ni2+ transport. The Km values for the other metals varied from 0.19 to 0.39 μM (Table 2).

Figure 1. Effect of Co2+ concentration on the rate of Co2+ uptake into reticulocytes incubated in solutions of KCl, sucrose or NaCl.

The cells were incubated at 37 °C in isotonic KCl (pH 7.0), sucrose (pH 7.0) or NaCl (pH 7.4) with varying concentrations of 57CoSO4. The figure shows the uptake into the cytosolic fraction of the cells. Four experiments of this type were performed with all of the metals and with similar results.

Table 2.

Km and Vmax values for transition metal uptake to the cytosol of reticulocytes and erythrocytes

| Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol (ml cells)−1 min−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose, pH 6.5 | KCl, pH 7.0 | Sucrose, pH 6.5 | KCl, pH 7.0 | |||

| Reticulocytes | Reticulocytes | Erythrocytes | Reticulocytes | Reticulocytes | Erythrocytes | |

| Fe2+ | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 16 ± 1.8 | 14 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 0.18 | 17 ± 1.7 | 8.6 ± 0.71 |

| Mn2+ | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 40 ± 4.5 * | 25 ± 1.9 * | 2.0 ± 0.36 | 32 ± 3.6 * | 16 ± 1.9 * |

| Co2+ | 0.38 ± 0.06 * | 24 ± 1.8 * | 11 ± 2.5 | 2.0 ± 0.23 | 24 ± 2.0 * | 7.0 ± 2.0 |

| Zn2+ | 0.39 ± 0.07 * | 27 ± 4.0 * | 16 ± 0.59 | 1.7 ± 0.27 | 33 ± 6.0 * | 12 ± 1.7 |

| Cd2+ | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 45 ± 8.4 * | 39 ± 5.9 * | 2.6 ± 0.47 | 11 ± 1.4 * | 6.6 ± 1.0 |

| Ni2+ | 1.8 ± 0.19 * | 25 ± 3.5 | 13 ± 1.0 | 0.80 ± 0.07 * | 15 ± 0.82 | 5.6 ± 0.95 * |

The reticulocytes or erythrocytes were incubated with 0.1–1 μm concentrations of the metals in isotonic sucrose, pH 6.5, or with 2–40 μm concentrations in isotonic KCl, pH 7.0. The curves relating uptake to metal concentration were analysed by SigmaPlot to determine Michaelis-Menten constants (Km) and the maximum rates of uptake (Vmax) of the saturable component of the curves. Each value is the mean ±s.e.m. of 4 determinations.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) from the values for Fe2+.

The rate of metal uptake from KCl solution levelled off as the concentration was raised but at a much higher concentration than with sucrose (Fig. 1). Analysis of the data by SigmaPlot showed that the results could be fitted by single saturable curves. With reticulocytes, the Km values for these curves varied from 16 to 45 μM, the lowest value being obtained with Fe2+ and the highest with Cd2+ (Table 2). Similar measurements were made with erythrocytes. Again Cd2+ was found to have the highest Km. The mean Km values for the transport of each of the metals into erythrocytes were all lower than with reticulocytes, as were the Vmax values, which varied between 30 and 61 % of the values for reticulocytes (Table 2).

Competition for metal transport

The inhibition of iron and manganese transport into reticulocytes by some of the metals studied in the present work has been reported previously (Morgan, 1988; Stonell et al. 1996; Chua et al. 1996). This inhibition was investigated systematically and more completely in the present work by determining the effect of varying concentrations of unlabelled metals on the uptake of radiolabelled samples of the metals by reticulocytes when the cells were incubated in sucrose solution with 1 μM concentrations of the labelled metals or in KCl solution with 20 μM concentrations. All of the metals inhibited the uptake of the others but with differing potency, which is expressed in Table 3 as the concentration of unlabelled metal which produced 50 % inhibition of the uptake of the labelled metal (IC50). With respect to uptake from sucrose solution with 1 μM concentration of the labelled metal, the lowest IC50 values were found with Cd2+. In terms of inhibitory effectiveness the metals were in the order Cd2+ > Fe2+ > Mn2+ > Co2+ > Ni2+ > Zn2+.

Table 3.

Inhibition of the uptake of reticulocytes of transition metals by other transition metals and Na+ shown as IC50 (μM)

| Fe2+ | Mn2+ | Co2+ | Zn2+ | Ni2+ | Cd2+ | NaCl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 μm, sucrose | |||||||

| Fe2+ | — | 3.5 ± 0.51 | 6.0 ± 0.81 | 8.0 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 0.88 | 0.65 ± 0.10 | 8700 ± 750 |

| Mn2+ | 1.8 ± 0.18 | — | 2.2 ± 0.31 | 5.8 ± 0.58 | 4.4 ± 0.28 | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 7900 ± 360 |

| Co2+ | 1.8 ± 0.26 | 2.4 ± 0.60 | — | 4.7 ± 0.80 | 3.8 ± 0.06 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 6100 ± 480 |

| Zn2+ | 0.25 ± 0.10 | 0.48 ± 0.13 | 0.50 ± 0.08 | — | 1.1 ± 0.20 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 8000 ± 800 |

| Ni2+ | 1.7 ± 0.50 | 2.0 ± 0.35 | 2.2 ± 0.42 | 6.5 ± 0.78 | — | 0.46 ± 0.08 | 8300 ± 840 |

| Cd2+ | 30 ± 1.4 | 31 ± 3.6 | 27 ± 3.9 | 20 ± 2.5 | 18 ± 2.3 | — | 14100 ± 960 |

| 20 μm, KCl | |||||||

| Fe2+ | — | 104 ± 3.8 | 20 ± 1.8 | 19 ± 1.3 | 18 ± 1.5 | 155 ± 6.2 | 4200 ± 430 |

| Mn2+ | 30 ± 3.3 | — | 26 ± 1.6 | 29 ± 1.8 | 24 ± 1.0 | 119 ± 11 | 4100 ± 500 |

| Co2+ | 47 ± 2.1 | 123 ± 12 | — | 27 ± 2.2 | 36 ± 2.4 | 178 ± 19 | 4000 ± 500 |

| Zn2+ | 57 ± 6.7 | 130 ± 12 | 31 ± 2.1 | — | 34 ± 5.6 | 160 ± 5.5 | 4900 ± 550 |

| Ni2+ | 70 ± 7.8 | 165 ± 13 | 31 ± 3.9 | 27 ± 2.7 | — | 193 ± 21 | 3700 ± 450 |

| Cd2+ | 67 ± 6.8 | 185 ± 15 | 38 ± 3.4 | 26 ± 2.7 | 45 ± 6.1 | — | 4100 ± 440 |

Reticulocytes were incubated with radiolabelled samples of the metals (uptake metal) in sucrose or KCl in the presence of varying concentrations of the other metals or NaCl (non-radioactive). The results show the concentrations of the non-radioactive metals which produced 50 % inhibition of the rate of uptake (IC50) of the radioactive metals when the incubations were performed with 1 or 20 μm concentrations of the radiolabelled metals in sucrose (pH 6.5) or KCl (pH 7.0), respectively. Each value is the mean ±s.e.m. of 3 or 4 estimations.

A very different result was found for the uptake from KCl solution using 20 μM concentration of the radiolabelled metals. Here Zn2+, Co2+ and Ni2+ had approximately equal IC50 values, followed by higher values for Fe2+, then Mn2+, with Cd2+ the highest (Table 3).

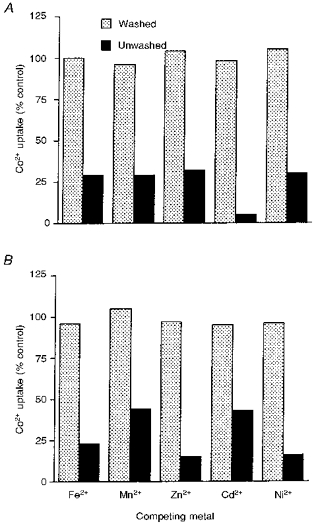

The inhibition produced by the various metals in both sucrose and KCl solutions was reversible. This was demonstrated by incubating reticulocytes with or without the metals (non-radioactive) for 5 min at 37°C, then washing twice with NaCl and once with sucrose (for uptake studies in sucrose) or three times in KCl, before reincubating the cells with radiolabelled metals in the absence or the presence of the competing non-radioactive metals. In all cases the washing procedure restored the rate of uptake of the metals to at least 95 % of that of cells in which the first incubation was performed in the absence of the metals (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Reversibility of the inhibition of Co2+ uptake into reticulocytes produced by other transition metals.

Reticulocytes were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min with or without non-radioactive samples of the metals, then washed 3 times and reincubated with radioactive samples of the metals, either in the presence (for the cells previously incubated without the metals) or the absence of the other metals (non-radioactive, for the cells originally incubated with the metals). The results are expressed as the uptake by the cells which had been washed after incubation with the non-radioactive metals, as a percentage of the uptake by the cells in which the non-radioactive metals were present during the final incubation. A, uptake from isotonic sucrose with 1 μM concentration of the radioactive metals and 10 μM concentration of the non-radioactive metals, except for Cd2+ uptake where the concentration of the competing metals was 30 μM. B, uptake from 20 μM concentration of the metals and 200 μM concentration of the competitors. The experiment was performed three times with similar results.

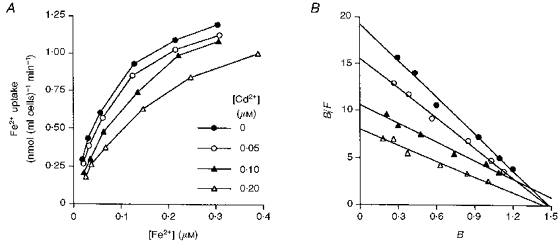

It was found in an earlier investigation (Morgan, 1988) that the inhibition of reticulocyte uptake of Fe2+ from sucrose solution by Mn2+, Co2+, Zn2+ and Ni2+ was of a competitive type. The inhibition produced by Cd2+ was investigated in a similar way by incubating reticulocytes with increasing concentrations of 59Fe2+ in the absence or presence of Cd2+. The addition of Cd2+ resulted in an increase in Km for iron uptake without change in Vmax (Fig. 3), evidence for a competitive type of inhibition.

Figure 3. Effect of Cd2+ on the uptake of 59Fe2+ by reticulocytes.

Reticulocytes were incubated in isotonic sucrose solution with varying concentrations of Fe2+ either in the absence of Cd2+ (•) or in the presence of 0.05 (○), 0.10 (▴) or 0.20 μM Cd2+ (▵). A, Fe2+ uptake to the cytosol;B,Eadie-Hofstee plots of the uptake results, in which B is the amount of Cd2+ taken up by the cells, expressed in nmol (ml cells)−1 min−1, and F is the concentration of Cd2+ in the solution in nmol ml−1. It is representative of 3 experiments which gave similar results.

Comparable studies were performed for Fe2+ uptake by reticulocytes in KCl solution in the presence of the other metals. With Mn2+, Co2+ and Zn2+, the results indicated a competitive type of inhibition, but with Cd2+ and Ni2+ there was a reduction in Vmax as well as an increase in Km. Hence, the inhibition due to Cd2+ and Ni2+ was of mixed type.

The effect of NaCl on metal uptake by reticulocytes was investigated by adding varying amounts of 290 mosmol kg−1 NaCl to the sucrose or KCl solutions so as to achieve increasing concentrations of NaCl in the solutions without altering osmolality. NaCl inhibited uptake of all of the metals from both the sucrose and KCl incubation solution. With sucrose the IC50 values for NaCl-induced inhibition varied from 6 to 14 mM, the highest value, which was significantly higher than the other values, being obtained for Cd2+ uptake. With KCl the IC50 values were lower and very similar for all of the metals, 3.7 to 4.9 mM (Table 3).

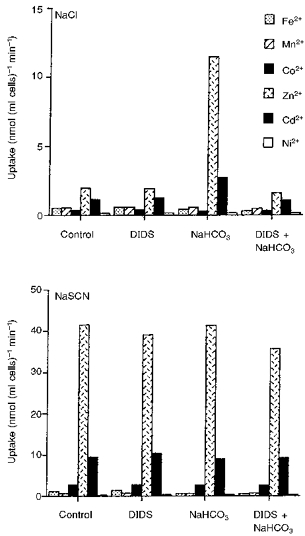

Effect of bicarbonate and thiocyanate on metal uptake

Both HCO3− and SCN− have been reported to stimulate Zn2+ uptake (Alda Torrubia & Garay, 1989) and HCO3− to stimulate Cd2+ uptake (Lou, Garay & Alda Torrubia, 1991) by human erythrocytes. The effects of these anions on the uptake of the other metals used in the present work, as well as Zn2+ and Cd2+, by rabbit reticulocytes and erythrocytes was therefore investigated. Cells were incubated with 20 μM concentration of the metals in isotonic solutions of NaCl, NaCl plus 15 mM NaHCO3, NaSCN or NaSCN plus 15 mM NaHCO3, all at pH 7.4, with or without the addition of 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2′,2′-disulphonic acid (DIDS). The addition of NaHCO3 to the NaCl solution or its replacement by NaSCN greatly accelerated the rate of uptake of Zn2+ and Cd2+ but not that of the other metals (Fig. 4). This increase in Zn2+ and Cd2+ uptake produced by NaHCO3 was almost completely inhibited by DIDS. However, that due to NaSCN was reduced only by a small degree. Addition of NaHCO3 to the NaSCN incubation solution did not increase metal uptake. However, in separate experiments in which reticulocytes were incubated in solutions containing both NaCl and NaSCN in varying proportions, the effect of addition of NaHCO3 was found to be additive to that of NaSCN (results not shown). The rates of Zn2+ uptake in the presence of HCO3− or SCN− were significantly greater with erythrocytes than with reticulocytes (Table 4). With both types of cells the uptake rates increased linearly with concentration up to at least 80 μM, the highest concentration which was examined (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Effects of NaHCO3 and DIDS on transition metal uptake by reticulocytes incubated in isotonic NaCl or NaSCN, pH 7.4.

The NaHCO3 and DIDS were added to the incubation solutions where indicated at concentrations of 15 mM and 20 μM, respectively. The figure shows the results of 1 of 3 experiments with similar results.

Table 4.

Rate of Zn2+ and Cd2+ uptake (nmol (ml cells)−1 min−1) from NaCl - NaHCO3 or NaSCN solutions by reticulocytes and erythrocytes

| Reticulocytes | Erythrocytes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn2+ | Cd2+ | Zn2+ | Cd2+ | |

| NaCl-NaHCO3 | 29 ± 1.7 | 6.6 ± 0.49 | 43 ± 4.1 * | 8.7 ± 1.3 |

| NaSCN | 46 ± 3.2 | 9.3 ± 0.72 | 65 ± 4.2 * | 12.0 ± 1.5 |

The cells were incubated at 37 °C with 20 μm concentrations of Zn2+ or Cd2+ in 140 mm NaCl-15 mm NaHCO3 or 155 mm NaSCN buffered with 4 mm Tris-Hepes, pH 7.4. The results show the rate of uptake to the cytosol fraction of the cells and are the means ± s.e.m of 12 estimations with reticulocytes and 6 estimations with erythrocytes.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the values for reticulocytes.

Figure 5. Uptake of Zn2+ and Cd2+ by reticulocytes and erythrocytes when incubated in isotonic NaCl-NaHCO3 or NaSCN.

The reticulocytes (▵, ○) and erythrocytes (▴, •) were incubated with varying concentrations of Zn2+ (continuous lines) or Cd2+ (dashed lines) in NaCl containing 15 mM NaHCO3 (▵, ▴) or in NaSCN (○, •) at pH 7.4. This experiment was repeated once, with similar results.

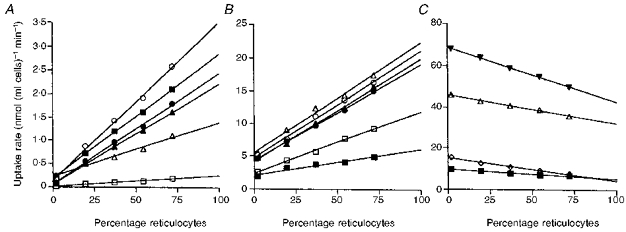

Effect of reticulocyte concentration

Erythroid and reticulocyte cell suspensions were mixed in varying proportions. They were then washed with the appropriate solutions and incubated with the metals in sucrose, KCl, NaCl plus NaHCO3 or NaSCN. The results of one experiment are illustrated in Fig. 6. A second experiment gave similar results. Under all incubation conditions the relationship between rate of uptake of the metals and reticulocyte count was linear but the patterns observed under the different incubation conditions were quite different. With 1 μM metals in sucrose solution the rates of uptake all increased markedly as the reticulocyte count was raised, the results for Fe2+, Mn2+, Co2+ and Cd2+ being similar and that for Ni2+ considerably lower, with Zn2+ between Ni2+ and the other metals. Also, with Fe2+, Mn2+, Co2+ and Ni2+ the regression lines for uptake at varying reticulocyte count passed close to zero when extrapolated to zero reticulocytes, while those for Zn2+ and Cd2+ extrapolated to a low proportion of reticulocytes, but one which was clearly above zero. When the incubations were performed with 20 μM metals in KCl solution there was, again, a positive linear correlation between uptake rate and reticulocyte count but the uptake results did not extrapolate to zero at zero reticulocytes. If the results were also extrapolated to 100 % reticulocytes the ratio of uptake at 100 % to that at 0 % reticulocytes varied from 2.4 (Ni2+) to 3.6 (Co2+). Incubation of the cells with Zn2+ or Cd2+ in NaCl-NaHCO3 or NaSCN gave quite different results, an inverse linear relationship between uptake rate and reticulocyte percentage. In this case when the results were extrapolated to 0 and 100 % reticulocytes the ratio of uptake of reticulocytes to erythrocytes was found to be approximately 0.6 for Zn2+ and 0.5 for Cd2+ under both types of incubation conditions.

Figure 6. Effect of reticulocyte count on transition metal uptake from isotonic sucrose (A), KCl (B) and NaCl-HCO3 or NaSCN (C).

Cells from a normal rabbit (2 % reticulocytes) were mixed with varying proportions of cells from a rabbit with phenylhydrazine-induced reticulocytosis (72 % reticulocytes) to give the indicated reticulocyte levels. They were then incubated at 37 °C with Fe2+ (•), Mn2+(○), Co2+(▴), Zn2+(▵), Cd2+(▪) or Ni2+(□) at 1 μM concentration in sucrose, pH 6.5 (A) or 20 μM concentration in KCl, pH 7.0 (B). In C the incubations were performed in 140 mM NaCl-15 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4, with 20 μM Zn2+ (▵) and Cd2+ (▪) and in 155 mM NaSCN, pH 7.4, with 20 μM Zn2+ (▾) and Cd2+ (⋄). The figure, which is representative of 1 of 3 similar experiments, shows the linear regression lines for each metal extrapolated to 0 and 100 % reticulocytes in order to allow a comparison between suspensions containing only erythrocytes and reticulocytes.

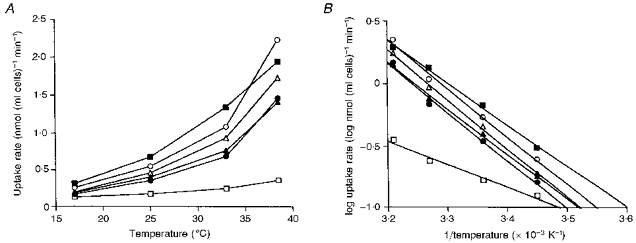

Effect of incubation temperature

When the incubations were performed at different temperatures between 19 and 38°C the transport of the metals into reticulocytes under four types of incubation conditions (1 μM metals in sucrose, 20 μM metals in KCl, NaCl-NaHCO3 or NaSCN) was found to be temperature dependent, as illustrated in Fig. 7 for the uptake of the metals from sucrose solution. Arrhenius plots of the data were performed (Fig. 7B) and the activation energies (Ea) calculated. With only two exceptions the values for Ea of all of the transport processes were found to vary between 74 and 106 kJ mol−1 (Table 5). The exceptions were the uptake of Ni2+ (1 μM) from sucrose solution and of Zn2+ (20 μM) from NaSCN, which were found to have lower activation energies than the other values, 38 and 61 kJ mol−1, respectively.

Figure 7. Effect of incubation temperature on the rate of transition metal uptake by reticulocytes incubated in isotonic sucrose, pH 6.5.

The cells were incubated with 1 μM concentrations of Fe2+ (•), Mn2+ (○), Co2+ (▴), Zn2+ (▵), Cd2+ (▪) or Ni2+ (□) at the indicated temperatures. The figure shows the rate of metal uptake (A) and Arrhenius plots of the uptake rate (B). This experiment was performed 3 times.

Table 5.

Arrhenius activation energy for the uptake of transition metals by reticulocytes

| Activation energy (kJ mol−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation solution | [Metal] (μm) | Fe2+ | Mn2+ | Co2+ | Zn2+ | Cd2+ | Ni2+ |

| Sucrose, pH 6.5 | 1.0 | 80 ± 4.5 | 83 ± 3.9 | 74 ± 5.7 | 81 ± 5.7 | 38 ± 3.4 * | 77 ± 3.5 |

| KCl, pH 7.0 | 20 | 81 ± 5.4 | 97 ± 4.5 | 79 ± 5.5 | 82 ± 6.7 | 78 ± 5.7 | 106 ± 7.2 |

| NaCl-NaHCO3, pH 7.4 | 20 | — | — | — | 76 ± 6.8 | — | 93 ± 3.5 |

| NaSCN, pH7.4 | 20 | — | — | — | 61 ± 5.7 | — | 96 ± 7.5 ** |

Reticulocytes were incubated with solutions of the metal ions at temperatures varying from 19 to 38 °C. The activation energies were determined from Arrhenius plots of the rate of metal uptake to the cytosol as shown in Fig. 7B. Each value is the mean ±s.e.m. of 3 measurements.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) from the value for Fe2+.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) from the value for Zn2+.

Effects of biochemical inhibitors

A range of biochemical reagents have been shown to inhibit Fe2+ and Mn2+ uptake by reticulocytes (Savigni & Morgan, 1996; Chua et al. 1996). In the present work these reagents were tested for their effects on the uptake of the other metals by reticulocytes, as well as on Fe2+ and Mn2+ uptake. With each of the incubation conditions the patterns of results for all six metals were very similar and, for simplicity of presentation, only the results for Zn2+ transport will be presented (Table 6). When incubated with 1 μM concentrations of the metals in sucrose solution, transport into reticulocytes was inhibited by 50 % or more by oligomycin, antimycin A, rotenone and N-ethylmaleimide and was stimulated by valinomycin and DIDS. By contrast, transport from KCl solution containing 20 μM concentrations of the metals was very strongly inhibited by valinomycin and also by amiloride, quinidine, diethylstilboestrol, imipramine and oligomycin but was not inhibited by antimycin A, rotenone and 2,4-dinitrophenol, and was relatively insensitive to N-ethylmaleimide. Only Zn2+ and Cd2+ (20 μM) were investigated with respect to the effects of inhibitors on transport into reticulocytes when incubated in NaCl-NaHCO3 and NaSCN solutions. Similar results were found with the two metals. With the incubations in NaCl-NaHCO3, DIDS significantly inhibited uptake, but uptake from NaSCN solution was reduced only slightly by this inhibitor. Another difference between the NaCl-NaHCO3 and NaSCN uptake results was the effects of oligomycin and 2,4-dinitrophenol, each of which inhibited uptake from only one of these two solutions.

Table 6.

Effects of inhibitors on Zn2+ uptake by reticulocytes

| Zn2+ uptake (% control value) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent | Concentration (μm) | 1 μm sucrose | 20 μm KCl | 20 μm NaCl-NaHCO3 | 20 μm NaSCN |

| Amiloride | 500 | 95 ± 7.0 | 13 ± 2.5 * | 101 ± 1.9 | 101 ± 5.0 |

| Valinomycin | 0.5 | 266 ± 38 * | 13 ± 2.9 * | 98 ± 4.8 | 84 ± 4.9 * |

| Oligomycin | 2.0 | 50 ± 4.6 * | 16 ± 3.0 * | 96 ± 5.6 | 34 ± 2.9 * |

| Antimycin A | 2.0 | 46 ± 5.8 * | 126 ± 14 | 94 ± 3.1 | 84 ± 2.8 * |

| Rotenone | 0.1 | 43 ± 6.5 * | 120 ± 8.0 | 102 ± 5.4 | 98 ± 3.3 |

| 2,4-Dinitrophenol | 1000 | 42 ± 5.7 * | 122 ± 7.0 | 39 ± 2.4 * | 95 ± 4.5 |

| Quinidine | 100 | 65 ± 8.0 * | 24 ± 4.3 * | 107 ± 4.0 | 65 ± 6.8 * |

| Imipramine | 20 | 89 ± 9.2 | 29 ± 2.6 * | 97 ± 3.5 | 107 ± 5.5 |

| Diethylstilboestrol | 10 | 89 ± 7.1 | 18 ± 3.4 * | 83 ± 5.0 * | 49 ± 7.8 * |

| N-Ethylmaleimide | 100 | 31 ± 3.8 * | 89 ± 9.6 | 104 ± 3.0 | 81 ± 4.7 * |

| DIDS | 20 | 294 ± 34 * | 55 ± 5.4 * | 6.0 ± 1.7 * | 91 ± 2.1 |

The cells were preincubated with the reagents at the indicated concentrations for 10 min before incubation at 37 °C with 1 μm Zn2+ in sucrose (pH 6.5) or 20 μm Zn2+ in isotonic KCl, NaCl-NaHCO3 (15 mm NaHCO3) or NaSCN. The results are expressed as percentages of control values obtained in the absence of the reagents and are means ±s.e.m. of 3-4 measurements.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) from control value, based on statistical analysis of uptake data in terms of nmol (ml cells)−1 min−1.

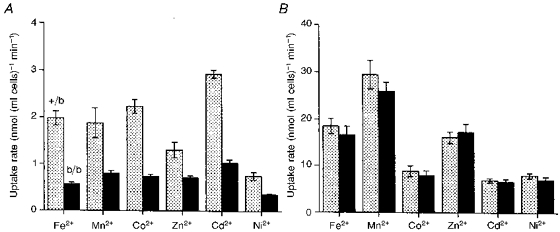

Metal transport into reticulocytes from Belgrade rats

The transport of Fe2+ and Mn2+ into reticulocytes from homozygous Belgrade rats is markedly impaired when the incubations are performed with 1 μM concentrations of the metals in sucrose solution but not with incubations at 20 μM concentrations in KCl (Farcich & Morgan, 1992a;Chua & Morgan, 1997). The uptake of Zn2+, Co2+, Cd2+ and Ni2+ was therefore studied, as well as Fe2+ and Mn2+. Due to the effect of reticulocyte count on metal uptake, the results were normalized to 40 % reticulocytes for each estimation after the relationship between reticulocyte level and metal uptake was determined for rat cells, as described above for rabbit cells. The relationships were similar for the cells from both species. The rate of transport of these metals from the sucrose incubation solution was found to be only 35–50 % as great with reticulocytes from homozygous Belgrade rats as with cells from heterozygous animals, but there was no significant difference between the two types of cells in the uptake from KCl solution (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Transition metal uptake by reticulocytes from homozygous Belgrade rats (b/b) and heterozygous Belgrade rats (+/b) when incubated in isotonic sucrose or KCl.

The cells from b/b (▪) or +/b (□) rats were incubated with 1 μM concentrations of the metals in sucrose (pH 6.5) or 20 μM concentrations in KCl (pH 7.0). The results were normalized to 40 % reticulocytes as described in the text. Each value is the mean ±s.e.m. of 4 measurements.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms of membrane transport of the transition metals iron, manganese, zinc, cobalt, nickel and cadmium were investigated in the present work by the use of different incubation solutions (sucrose, KCl, NaCl, NaSCN) and different chemical forms of the metals (ionized or bound to transferrin). The results provide evidence for at least four different transport mechanisms. This evidence includes specificity for the different metals, differences in transport activity between reticulocytes and erythrocytes, saturability and Km values, competition between the metals, effects of ionic strength, pH and salt composition of the incubation media, degree of inhibition produced by a range of biochemical reagents, and the differences in rates of transport between reticulocytes from homozygous and heterozygous Belgrade rats. Two of the transport mechanisms appeared to be capable of transporting iron and all of the other metals which were examined. These were uptake from sucrose solution and from KCl solution. They will be referred to as ‘high-affinity’ and ‘low-affinity’ transport, respectively, a terminology which was used previously for Fe2+ and Mn2+ transport (Savigni & Morgan, 1996; Chua et al. 1996) and which can now be applied to the transport of the other transition metals. The other two transport mechanisms, mediated by NaCl-NaHCO3 and NaSCN, were found to be specific for Zn2+ and Cd2+ and are probably dependent on the ability of these ions to interact with the mediators.

The conditions used for the investigation of the high-affinity transport mechanism, incubation in a low ionic strength medium such as isotonic sucrose solution, are unphysiological. Hence, the validity of using this system to study a membrane transporter may be questioned. However, several lines of evidence obtained during the study of iron transport by reticulocytes lead to the conclusion that it is a valid and useful model system for studying the transport of Fe2+ and other transition metals. This evidence includes the following observations.

(1) The process of Fe2+ uptake displays Michaelis-Menten kinetics, and the maximum rates of iron uptake and incorporation into haem are similar to those obtained for iron uptake from transferrin by cells incubated in NaCl solution at pH 7.4 (Morgan, 1988; Qian & Morgan, 1992). (2) The rate of Fe2+ uptake by the high-affinity process is reduced in direct proportion to the reduction in cellular ATP levels when reticulocytes are incubated in the presence of metabolic inhibitors (Qian & Morgan, 1991), as is the uptake of transferrin-bound iron (Kailis & Morgan, 1977). (3) High-affinity Fe2+ transport decreases at the same rate as transferrin-mediated uptake as reticulocytes mature in vivo and in vitro (Qian & Morgan, 1992). (4) The activation energy for Fe2+ transport to the cytosol of reticulocytes is high, and similar to that of other carrier-mediated processes (Morgan, 1988). (5) The rates of uptake of Fe2+ from sucrose solution and of transferrin-bound iron from NaCl solution are both impaired in reticulocytes from homozygous Belgrade rats (Farcich & Morgan, 1992a) while Fe2+ uptake by the low-affinity process is not impaired. These results show that Fe2+ uptake by reticulocytes incubated in isotonic sucrose has the characteristics of a carrier-mediated process, probably one of active transport, and the iron is efficiently transported into the intracellular pathway which leads to incorporation into haem. The present results show that this process can transport several other transition metals as well as Fe2+ into reticulocytes.

Suspension of reticulocytes and erythrocytes in media of low ionic strength has many effects on the cells, namely changes in membrane surface charge, transmembrane potential difference, permeability to monovalent cations and cell size. These changes have all been investigated with respect to their effects on Fe2+ transport into reticulocytes by the high-affinity mechanism (Quail & Morgan, 1994). All of the changes were observed but only one, an increase in negative membrane surface charge, was found to be of significance with respect to the high-affinity transport mechanism. It is likely that the increase in negative surface charge aids in the approach of Fe2+ to the cell membrane and its interaction with the iron transporter. Addition of NaCl or other salts to the medium would inhibit this effect and inhibit Fe2+ uptake. In the case of iron uptake from transferrin the interaction of transferrin with its receptor may achieve the same purpose by localization of the transferrin and its iron within the membrane close to the carrier and away from the cations present in the extracellular or endosomal medium that could compete with iron for binding to the transporter.

The high-affinity uptake of all of the metals (from isotonic sucrose solution) showed Michaelis-Menten kinetics, with relatively low Km values, and similar Vmax values, and similar sensitivity to inhibition by NaCl and the biochemical inhibitors and values for activation energy (Ea). The Km values increased in the order Cd2+ < Fe2+ < Mn2+ < Co2+ < Zn2+ < Ni2+, which is almost the same order as the IC50 values for inhibition of transport of the metals by each other. Hence, the relative affinity of the transport mechanism for the metals appears to be in this order. Although Cd2+ has the largest and Ni2+ the smallest ionic radius of the metals there does not appear to be any correlation between ionic radius and the affinity of the transport mechanism for the other metals. Ni2+ stands out a little from the other metals in having higher Km, lower Vmax and lower Ea values, but in other respects the characteristics of Ni2+ transport were similar to those of the others. Overall, the results point to a single transport mechanism which is shared by all of the metals. This process disappears as the reticulocyte matures into an erythrocyte, probably due to loss of the transporter as part of the maturation process. The disappearance occurs precisely in parallel with loss of transferrin receptors and the ability to take up transferrin-bound iron (Qian & Morgan, 1992). This, together with the results obtained with reticulocytes from homozygous Belgrade rats, supports the view that transferrin-bound iron is transported across the endosomal membrane by the same transporter as is responsible for high-affinity uptake from sucrose solution, except that in the latter situation transport occurs across the external cell membrane (Morgan, 1996b). Only with Zn2+ and Cd2+ did a low level of transport persist after maturation of reticulocytes and this may be due to Cl−-HCO3−-mediated transport due to low levels of Cl− and HCO3− present in the incubation solution derived from the cells and from atmospheric CO2, respectively. It was not possible to test for this by the use of DIDS since this reagent accelerates transport of the metals into cells incubated in sucrose solution, probably as a result of alterations in the transmembrane potential difference (Quail & Morgan, 1994).

The uptake of all of the metals by cells suspended in KCl solution (low-affinity transport) also appeared to involve a common transport mechanism, as shown by the similarities of properties and inhibition by each other. In nearly all characteristics which were studied, low-affinity transport differed from high-affinity transport. Hence, another transporter is involved, probably the Na+-Mg2+ antiport. Evidence for this with respect to Fe2+ and Mn2+ transport has been presented previously (Stonell et al. 1996; Chua et al. 1996). This mechanism normally functions to transport Mg2+ out of erythrocytes in exchange for extracellular Na+ (Flatman, 1991) but, in the absence of extracellular Na+, can probably transport transition metals into the cells. Whether this has any physiological significance or is simply a non-functional consequence of the biochemical properties of the transporter is uncertain. However, one possibility is that it serves to transport transition metals out of erythroid cells as well as Mg2+ (Chua et al. 1996). Irrespective of whether or not this is true, certain other features of the low-affinity transport of transition metals observed in the present work were of interest and require comment. Firstly, uptake of the metals from KCl solution was not impaired by incubation of reticulocytes with the metabolic inhibitors antimycin A, rotenone and 2,4-dinitrophenol, all of which lower cellular levels of ATP and inhibit high-affinity uptake of Fe2+ (Qian & Morgan, 1991) and of the other transition metals (present study). This suggests that low-affinity transport, unlike high-affinity transport, is not dependent on high cellular levels of ATP. Such a conclusion conflicts with that of a previous investigation in which incubation of reticulocytes with inosine and iodoacetamide was found to inhibit Fe2+ uptake by the low-affinity mechanism and led to the suggestion that Fe2+ is taken up by an active transport process (Stonell et al. 1996). However, iodoacetamide acts by alkylating sulfhydryl groups and is not restricted in its action to enzymes involved in energy metabolism. Possibly free sulfhydryl groups are required for the normal function of the transporter or, if ATP is required, the low-affinity transporter can function at lower ATP levels than the high-affinity transporter. There is evidence of an ATP requirement for the function of the Na+-Mg2+ antiport (Frenkel, Graziani & Schatzmann, 1989), but whether the ATP functions to supply energy for transport or to activate transport by phosphorylation of the transporter is uncertain (Flatman, 1991). Also, it must be noted that uptake of the metals was strongly inhibited by diethylstiboestrol and oligomycin, which are known to be inhibitors of ion-transporting ATPases (Whittam, Wheeler & Blake, 1964; McEnery & Pedersen, 1986). This suggests that the low-affinity transporter does depend on ATPase activity for the transport of transition metals. If so, it can probably function at lower levels of ATP than can the high-affinity transporter.

A second interesting feature of low-affinity transport is the decrease but not complete loss of activity as reticulocytes mature. In this regard the process resembles several other transport processes which show similar changes during erythroid cell maturation (Antonioli & Christensen, 1969; Brugnara & De Franceschi, 1993). A third observation of interest is that the inhibitory effects of Cd2+ and Ni2+ on Fe2+ transport are of mixed type, competitive and non-competitive, suggesting two modes of action, one by competing with Fe2+ for the transporter and a second by an indirect effect such as inhibition of the putative ATPase. A fourth point is that the highest Km values and lowest inhibitory potency on the uptake of the other metals, and highest Ea values, were observed with Mn2+ and Cd2+, the metals with the greatest ionic radii. This is in marked contrast to the results obtained for high-affinity uptake.

Two anionic mechanisms of Zn2+ and Cd2+ transport into human erythrocytes have been described previously, requiring bicarbonate plus chloride and thiocyanate (or salicylate), respectively (Alda Torrubia & Garay, 1989; Lou et al. 1991). The present investigation shows that similar transport processes are also present in rabbit erythroid cells and that transport mediated by bicarbonate plus chloride and by thiocyanate shows greater activity in mature erythrocytes than in reticulocytes. The other transition metals examined in this investigation were not transported by these mechanisms. The inhibition of bicarbonate-mediated transport of Zn2+ and Cd2+ by DIDS, and other evidence, led to the conclusion that transport into the cells occurs through the red cell anion exchanger after formation of anionic complexes of the metals with HCO3− and Cl− (Alda Torrubia & Garay, 1989; Lou et al. 1991). Failure to transport the other transition metals is probably a consequence of their inability to form such complexes. The anion exchanger of the red cell is represented by the membrane protein, band 3, which is synthesized in immature erythroid cells up to the reticulocyte stage and persists throughout the lifespan of the red cell (Foxwell & Tanner, 1981; Kirk & Lee, 1988). Since red cells decrease in size and show an increase in surface-to-volume ratio as they mature and age the relative concentration of band 3 increases. This can explain the observed increase in bicarbonate-mediated Zn2+ and Cd2+ transport which was observed. A similar change with reticulocyte maturation was observed for thiocyanate-mediated transport, which suggests that the mechanism responsible for this process also becomes more concentrated in the membrane of the cells as they mature. The observations that this process was not inhibited by DIDS but was inhibited by diethylstiboestrol and oligomycin indicate that it is unlikely to involve the anion exchanger but, nevertheless, is mediated by a membrane transporter rather than being due to a general membrane permeability to uncharged metal-thiocyanate complexes.

The results obtained with reticulocytes from Belgrade rats confirm earlier results obtained for Fe2+ and Mn2+ uptake (Farcich & Morgan, 1992a;Chua & Morgan, 1997), extend them to other transition metals, and provide further evidence that the high-affinity transport mechanism is shared by all of the metals. This process was markedly impaired in cells from homozygous Belgrade rats compared with cells for heterozygous animals. The previous studies showed no difference in Fe2+ and Mn2+ transport between reticulocytes from heterozygous Belgrade rats and normal Wistar rats. Hence, cells from heterozygous Belgrade rats may be used as normal controls for comparison with those from homozygous animals. The uptake of transferrin-bound iron and manganese, as well as that of the protein-free metals, is also impaired in cells from homozygous animals. This is due to impaired transport across the endosomal membrane, without an abnormality of the endocytotic process (Bowen & Morgan, 1987). Hence, as concluded above, it is likely that the same transport mechanism is involved in the uptake of metals derived from transferrin as in the high-affinity transport investigated in this study.

In homozygous Belgrade rats the transport of iron and manganese is impaired in the small intestine, liver, placenta and blood-brain barrier as well as in developing red blood cells (Farcich & Morgan, 1992b;Oates & Morgan, 1996; Chua & Morgan, 1997). Hence, it is likely that the high-affinity transport mechanism is present in many types of cells. Previous studies have provided numerous examples of inhibitory interactions, often shown to be of competitive type, between the absorption of iron and other transition metals in the small intestine (e.g. Forth & Rummel, 1971; Worwood, 1974) and between the uptake of iron and transition metals by the liver (Wright, Brisset, Ma & Weisiger, 1986), fibroblasts (Oshiro, Nakajima, Markello, Krasnewich, Bernadini & Gahl, 1993) and HeLa cells (Sturrock, Alexander, Lamb, Craven & Kaplan, 1990). Possibly this is the result of expression of the high-affinity transporter in these types of cells but definitive evidence for this will probably be obtained only when the transporter is isolated and cloned.

This may now have been achieved, by expression cloning in Xenopus laevis oocytes of mRNA from the duodenum of rats fed a low iron diet (Gunshin et al. 1997). By this means a transporter which can mediate the transport of a range of divalent cations (Fe2+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Cd2+, Ni2+, Pb2+) was identified. It was called DCT 1 (divalent cation transporter 1). Evidence was obtained that the transport is active, coupled with H+ transport and dependent on cell membrane potential. All of these features are compatible with those of the high-affinity transporter described in the present and in previous publications (Morgan, 1988; Qian & Morgan, 1991; Quail & Morgan, 1994). Moreover, DCT 1 mRNA is expressed in the bone marrow as well as in the duodenum and many other tissues. The amino-acid sequence of rat DCT 1 was found to be 92 % identical to that of the human protein Nramp 2. A mis-sense mutation in Nramp 2 which leads to the substitution of a glycine residue by arginine has been detected in mice with an inherited microcytic anaemia (Fleming et al. 1997). Homozygous mice with this defect (mk/mk) have a microcyte hypochromic anaemia associated with impairment of intestinal iron absorption and of iron utilization by immature erythroid cells (Bannerman, 1976). The disorder of iron metabolism closely resembles that present in homozygous Belgrade rats. Collectively, the results in these two recent publications plus those of the present investigation lead to the hypothesis that the high-affinity iron transporter is Nramp 2 or a closely related member of the Nramp family of proteins and that a mutation of this protein leads to the abnormalities of iron metabolism which occur in homozygous Belgrade rats.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council.

References

- Alda Torrubia JO, Garay R. Evidence for a major route for zinc uptake in human red blood cells: [Zn(HCO3)2Cl]− influx through the [Cl−/HCO3−] anion exchanger. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1989;138:316–322. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041380214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonioli JA, Christensen HN. Differences in schedules of regression of transport systems during reticulocyte maturation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1969;244:1505–1509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker E, Morgan EH. Iron Transport. In: Brock JH, Halliday JW, Pippard MJ, Powell LW, editors. Iron Metabolism in Health and Disease. London: W. B. Saunders; 1994. pp. 63–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman RM. Genetic defects of iron transport. Federation Proceedings. 1976;35:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen BJ, Morgan EH. Anemia of the Belgrade rat: evidence for defective membrane transport of iron. Blood. 1987;70:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugnara C, De Franceschi L. Effect of cell age and phenylhydrazine on the cation transport properties of rabbit erythrocytes. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1993;154:271–280. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041540209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua ACG, Morgan EH. Manganese metabolism is impaired in the Belgrade laboratory rat. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 1997;167:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s003600050085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua ACG, Stonell LM, Savigni DL, Morgan EH. Mechanisms of manganese transport in rabbit erythroid cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:99–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farcich EM, Morgan EH. Uptake of transferrin-bound and non-transferrin-bound iron by reticulocytes from the Belgrade laboratory rat: comparison with Wistar rat transferrin and reticulocytes. American Journal of Hematology. 1992a;39:9–14. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830390104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farcich EM, Morgan EH. Diminished iron acquisition by cells and tissues of Belgrade laboratory rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1992b;262:R220–224. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.2.R220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatman PH. Mechanisms of magnesium transport. Annual Review of Physiology. 1991;53:259–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.001355. 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MD, Trenor CC, Su MA, Foernzler D, Beier DR, Dietrich WF, Andrews NC. Microcytic anaemia mice have a mutation in Nramp 2, a candidate iron transporter gene. Nature Genetics. 1997;16:383–386. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forth W, Rummel W. Absorption of iron and chemically related metals in vitro & in vivo: specificity of the iron binding system in the mucosa of the jejunum. In: Skoryna SC, Waldron-Edward D, editors. Intestinal Absorption of Metal Ions, Trace Elements and Radionuclides. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1971. pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Foxell BMJ, Tanner MJA. Synthesis of the erythrocyte anion-transport protein. Immunological studies of its incorporation into the plasma membrane of erythroid cells. Biochemical Journal. 1981;195:129–137. doi: 10.1042/bj1950129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel EJ, Graziani M, Schatzmann HJ. ATP requirement of the sodium-dependent magnesium extrusion from human red blood cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;414:385–397. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Gunshin Y, Romero MF, Boron WF, Nussberger S, Gollan JL, Hedlger MA. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;383:482–488. doi: 10.1038/41343. 10.1038/41343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmaplardh D, Morgan EH. The mechanism of iron exchange between synthetic iron chelators and rabbit reticulocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1974;373:84–99. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson LL, Quail EA, Morgan EH. Iron transport mechanisms in reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1995;162:181–190. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041620204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kailis SG, Morgan EH. Iron uptake by immature erythroid cells. Mechanism of dependence on metabolic energy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1977;464:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(77)90013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk RG, Lee P. Anion transport during maturation of erythroblastic cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1988;101:173–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01872832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou M, Garay R, Alda Torrubia JO. Cadmium uptake through the anion exchanger in human red blood cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;443:123–136. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEnery MW, Petersen PL. Diethylstilbestrol. A novel F0-directed probe of the mitochondrial ATPase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:1745–1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EH. Membrane transport of non-transferrin-bound iron by reticulocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1988;943:428–439. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EH. Iron metabolism and transport. In: Zakim D, Boyer TD, editors. Hepatology A Textbook of Liver Disease. 3. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1996a. pp. 526–554. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EH. Cellular iron processing. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1996b;11:1027–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates PS, Morgan EH. Defective iron uptake by the duodenum of Belgrade rats fed diets of different iron contents. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:G826–832. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.5.G826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshiro S, Nakajima H, Markello T, Krasnewich D, Bernardini I, Gahl WA. Redox, transferrin-independent, and receptor-mediated endocytosis iron uptake systems in cultured human fibroblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:21586–21591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian ZM, Morgan EH. Effect of metabolic inhibitors on uptake of non-transferrin-bound iron by reticulocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1991;1073:456–462. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian ZM, Morgan EH. Changes in the uptake of transferrin-free and transferrin-bound iron during reticulocyte maturation in vivo and in vitro. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1992;1135:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90163-6. 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail EA, Morgan EH. Role of membrane surface potential and other factors in the uptake of non-transferrin-bound iron by reticulocytes. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1994;159:238–244. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041590207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savigni DL, Morgan EH. Use of inhibitors of ion transport to differentiate iron transporters in erythroid cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1996;52:371–377. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00217-1. 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladic-Simic D, Zivkovic N, Pavic D, Markinkovic D, Martinovic J, Martinovitch PN. Hereditary hypochromic microcytic anemia in the laboratory rat. Genetics. 1966;53:1079–1089. doi: 10.1093/genetics/53.6.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonell LM, Savigni DL, Morgan EH. Iron transport into erythroid cells by the Na+/Mg2+ antiport. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1282:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock A, Alexander J, Lamb J, Craven CM, Kaplan J. Characterization of a transferrin-independent uptake system for iron in HeLa cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:3139–3145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittam R, Wheeler KP, Blake A. Oligomycin and active transport reactions in cell membranes. Nature. 1964;203:720–724. doi: 10.1038/203720a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worwood M. Iron and trace Metals. In: Jacobs A, Worwood M, editors. Iron in Biochemistry and Medicine. London: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 335–367. [Google Scholar]

- Wright TL, Brissot P, Ma W-L, Weisiger RA. Characterization of non-transferrin-bound iron clearance by rat liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:10909–10914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]