Abstract

Whole-cell patch clamp and intracellular recordings were obtained from 190 sympathetic preganglionic neurones (SPNs) in spinal cord slices of neonatal rats. Fifty-two of these SPNs were identified histologically as innervating the superior cervical ganglion (SCG) by the presence of Lucifer Yellow introduced from the patch pipette and the appearance of retrograde labelling following the injection of rhodamine-dextran-lysine into the SCG.

Electrical stimulation of the ipsilateral (n= 71) or contralateral (n= 32) lateral funiculi (iLF and cLF, respectively), contralateral intermediolateral nucleus (cIML, n= 41) or ipsilateral dorsal horn (DH, n= 34) evoked EPSPs or EPSCs that showed a constant latency and rise time, graded response to increased stimulus intensity, and no failures, suggesting a monosynaptic origin.

In all neurones tested (n= 60), fast rising and decaying components of EPSPs or EPSCs evoked from the iLF, cLF, cIML and DH in response to low-frequency stimulation (0.03-0.1 Hz) were sensitive to non-NMDA receptor antagonists.

In approximately 50 % of neurones tested (n= 29 of 60), EPSPs and EPSCs evoked from the iLF, cLF, cIML and DH during low-frequency stimulation were reduced by NMDA receptor antagonists. In the remaining neurones, an NMDA receptor antagonist-sensitive EPSP or EPSC was revealed only in magnesium-free bathing medium, or following high-frequency stimulation.

EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the iLF exhibited a sustained potentiation of the peak amplitude (25.3 ± 11.4 %) in six of fourteen SPNs tested following a brief high-frequency stimulus (10-20 Hz, 0.1-2 s).

These results indicate that SPNs, including SPNs innervating the SCG, receive monosynaptic connections from both sides of the spinal cord. The neurotransmitter mediating transmission in some of the pathways activated by stimulation of iLF, cLF, cIML and DH is glutamate acting via both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors. Synaptic plasticity is a feature of glutamatergic transmission in some SPNs where EPSPs are potentiated following a brief high-frequency stimulus. Our data also suggest a differential expression of NMDA receptors by these neurones.

Sympathetic preganglionic neurones (SPNs) in the thoracolumbar spinal cord constitute an important integrative site. SPNs receive inputs from a wide variety of sources including local interneurones originating in spinal laminae I, IV, V, VII and IX (Strack, Sawyer, Hughes, Platt & Loewy, 1989; Craig, 1993; Cabot, Alessi, Carrol & Lignori, 1994), and inputs originating in upper cervical spinal levels in laminae I, V and VII, and the lateral spinal nucleus (LSN) and lateral funiculus (LF) (Jansen & Loewy, 1997). The LF also carries descending inputs from the brain centres that innervate SPNs directly. These centres include the caudal raphe area, rostral ventrolateral medulla, ventromedial medulla, A5 cell group of the medulla, paraventricular and lateral hypothalamic nuclei, and periaqueductal grey matter (for reviews see Coote, 1988; Laskey & Polosa, 1988).

Many studies implicate excitatory amino acids (EAAs) such as L-glutamate as putative neurotransmitters acting on SPNs. EAAs excite SPNs when applied iontophoretically in vivo (Backman & Henry, 1983) and selective EAA-receptor agonists have been shown to excite SPNs in vitro (Shen, Mo & Dun, 1990; Spanswick & Logan, 1990; Inokuchi, Yoshimura, Yamada, Polosa & Nishi, 1992). The intermediolateral nucleus (IML), where the majority of SPNs are located, contains binding sites for the EAA-receptor agonist kainate (Morrison, Ernsberger, Milner, Callaway, Gong & Reis, 1989) and glutamate-immunoreactive synapses have been shown to impinge on SPNs (Morrison, Callaway, Milner & Reis, 1989; Llewellyn-Smith, Phend, Minson, Pilowsky & Chalmers, 1992) as have synapses immunoreactive for phosphate-activated glutaminase, which catalyses the conversion of glutamine to glutamate (Chiba & Kaneko, 1993).

Electrophysiological studies in adult cat in vivo have demonstrated that summating fast EPSPs are largely responsible for both background and reflex firing in SPNs (Dembowsky, Czachurski & Seller, 1985). Investigations into the properties of fast EPSPs in vitro, although indicating that they are most likely to be mediated by EAAs, have provided conflicting reports on the nature of the receptors involved. Studies in a longitudinal slice preparation from rat have demonstrated a role for non-NMDA receptors (Sah & McLachlan, 1995). In neonatal rat, it has been suggested that dorsal root afferent transmission to SPNs is mediated exclusively via NMDA receptors whereas descending inputs from the lateral funiculus use non-NMDA receptors (Shen et al. 1990). However, data from a recent study suggest that both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors mediate synaptic transmission in segmental and descending pathways (Krupp & Feltz, 1995). Similar dual-component NMDA and non-NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs have been observed in adult cat (Inokuchi et al. 1992), and recent studies in neonatal rats indicate a role for NMDA and non-NMDA receptors in pathways from the ventrolateral medulla (Deuchars, Morrison & Gilbey, 1995).

We have utilized a spinal cord slice preparation to investigate the role of EAA receptors in mediating fast excitatory synaptic transmission to SPNs. In this study we introduced retrograde tracers to identify specific SPNs innervating the superior cervical ganglion (SCG). We now report on the involvement of EAA receptors in the responses of SPNs to stimulation of the ipsilateral lateral funiculus (iLF), contralateral lateral funiculus (cLF), contralateral intermediolateral nucleus (cIML), and ipsilateral dorsal horn (DH), and of a differential expression of NMDA receptors by these neurones. Synaptic plasticity is also a feature of glutamatergic transmission in some SPNs where EPSPs are potentiated following a brief high-frequency stimulus.

METHODS

Pre-labelling of SPNs

SPNs were prelabelled using methods modified from those used to label hypoglossal motoneurones projecting to peripheral targets (Viana, Gibbs & Berger, 1990). Neonatal rats (9-16 days old) were anaesthetized with halothane (4 % in O2), administered by placing the animal in a gas-tight chamber manufactured in the Department of Neurology, Ottawa Civic Hospital, Ottawa, Canada. The pedal and tail withdrawal reflexes were monitored to assess the depth of anaesthesia during prelabelling and prior to slice preparation (see below). The superior cervical ganglion was exposed and a small volume (10-20 μl) of 5-10 % tetramethylrhodamine-dextran- lysine (RDL, Molecular Probes) injected into the SCG, the wound sutured and the animals allowed to recover for a period of 2-6 days.

Recording and slice preparation

The methods employed in obtaining conventional intracellular and whole-cell recordings from rat spinal cord slices have been described in detail previously (Spanswick & Logan, 1990; Pickering, Spanswick & Logan, 1991). Briefly, Sprague-Dawley rats (9-21 days old) were anaesthetized with Enflurane (7 % in O2; Abbot Laboratories, Queensborough, Kent, UK), administered by placing the animal in a gas-tight chamber manufactured in the Department of Neurology, Ottawa Civic Hospital. Animals were subsequently decapitated, the spinal cord removed and a section of thoracolumbar segment cut into 350-500 μm thick slices using a Vibratome (Technical Products International Inc., St Louis, MO, USA). In the case of animals with RDL injected into the SCG, a section of spinal cord between C6 and T6 was removed and cut into slices. Slices were transferred to a recording chamber and superfused with an artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) of the following composition (mm): 127 NaCl, 1.9 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3 and 10 D-glucose; gassed with 95 % O2, 5 % CO2; pH 7.4. In experiments where low-calcium, high-magnesium solution was used, CaCl2was omitted and MgCl2 was increased to 5.2 mm. In experiments where magnesium-free solution was used, MgCl2was omitted.

Intracellular recordings were obtained at 35 ± 0.5°C with 3 M potassium acetate-filled glass microelectrodes with tip resistances ranging from 50 to 120 MΩ. Measurement of membrane potential and intracellular current injection was achieved using a high impedance bridge amplifier (SVC 2000, WPI, or Axoclamp-2A, Axon Instruments). Whole-cell recordings were obtained from SPNs at room temperature (17-20°C) with patch pipettes of resistance 3-12 MΩ filled with the following solution (mm): 130 potassium gluconate, 10 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA-Na, 10 Hepes and 2 Na2ATP; pH 7.4 with NaOH. In some experiments the concentration of EGTA was reduced to 0.5 mm and CaCl2 to 0.1 mm. Recordings were obtained with a patch-clamp amplifier (EPC-7, List Electronic, or Axopatch-1D, Axon Instruments). Correction of the liquid junction potential was applied to whole-cell recordings and access resistances ranged between 5 and 25 MΩ. Series resistance compensation (typically of approximately 70 %) was used for whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments. Intracellular and whole-cell recordings were monitored on an oscilloscope (Gould 1604), displayed on a pressure ink pen recorder (Gould 2400S or Gould RS3200) and stored on videotape for later analysis.

Synaptic potentials were elicited by stimulation of the ipsilateral lateral funiculus (iLF), ipsilateral dorsal horn (DH), contralateral lateral funiculus (cLF) or contralateral intermediolateral nucleus (cIML) of the spinal cord with concentric bipolar stimulating electrodes at stimulus intensities of between 1 and 12 V. A variety of stimulating electrodes were used with tip diameters ranging between 10 and 50 μm. To ensure selective activation of iLF, DH, cLF and cIML, electrodes were also manoeuvred to positions outside of, and proximal to, these sites (see Fig. 2). Failure to generate synaptic responses outside of these areas was taken to indicate selective activation of pathways from iLF, cLF, cIML and DH, and was not the result of current spread recruiting other pathways. Low-frequency stimulation of one stimulus per 10 s up to one stimulus per 30 s (0.03-0.1 Hz) was used to evoke constant and consistent EPSPs. High-frequency stimuli (10-20 Hz) were used to test for failures of synaptic responses, and in experiments to examine potentiation of postsynaptic responses.

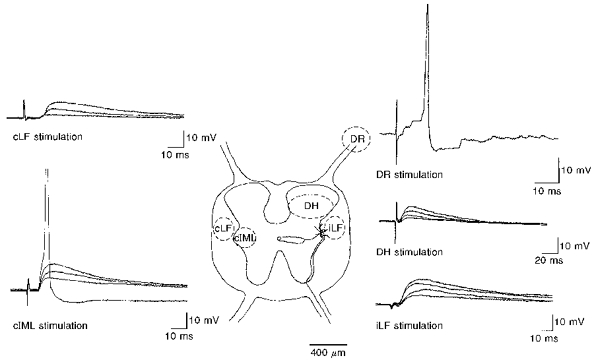

Figure 2.

Sites of activation of EPSPs in SPNsCentre, schematic diagram illustrating a transverse section of thoracolumbar spinal cord and areas (dashed lines) from where EPSPs were evoked. cLF, contralateral lateral funiculus; iLF, ipsilateral lateral funiculus; DH, dorsal horn; DR, dorsal rootlets; cIML, contralateral intermediolateral cell nucleus. Surrounding panels show representative examples of synaptic responses obtained with whole-cell current clamp or intracellular recording techniques from different SPNs. DR, intracellular record of an EPSP evoked by stimulation of dorsal rootlets (Vm, -58 mV) shows summating EPSPs leading to action potential discharge. Also shown are examples of whole-cell recordings of EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the DH (Vm, -60 mV), iLF (Vm, -59 mV), cLF (Vm, -63 mV) and cIML (Vm, -60 mV). Note each of these records shows three or four superimposed EPSPs evoked in response to increasing stimulus intensity.

The following drugs were used: 3-((R)-2-carboxypiperazin-4-yl)-propyl-1-phosphonic acid (D-CPP), 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), D-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (D-APV), and DL-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (DL-APV) were all from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). 2,3-Dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulphamoyl-benzo(f)quinoxalin (NBQX), 1-(4-aminophenyl)-4-methyl-7,8-methylenedioxy-5H-2,3-benzodiazepine hydrochloride (GYKI 52466), phentolamine, prazosin and yohimbine were all from Research Biochemicals International (RBI). Strychnine hydrochloride and bicuculline methiodide were from Sigma. CNQX and NBQX were made up as concentrated stocks in NaOH, and prazosin in methanol. The remaining agents were made up as concentrated stocks in distilled water or ACSF. All drugs were subsequently diluted to concentrations indicated in ACSF. Appropriate controls were carried out for CNQX, NBQX and prazosin with vehicles used to dissolve these agents.

Double labelling of SPNs

In slices from animals in which one SCG had been injected with RDL, only one cell on the ipsilateral side was recorded from per slice, using a ‘blind’ approach. Neurones were identified as SPNs innervating the SCG by the presence of double labelling with Lucifer Yellow from the pipette and RDL injected into the SCG. Following recording, slices were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (PB) for 4-12 h, and subsequently transferred to 25 % sucrose in PB for 2-8 h. Slices were then frozen and resectioned into 25-40 μm sections, collected on a glass slide and air dried. Sections were viewed under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioskop) with appropriate filters for rhodamine and Lucifer Yellow.

Morphology of SPNs

For unambiguous identification of non-prelabelled SPNs, the morphology of neurones was examined by including the intracellular markers Lucifer Yellow (dipotassium salt, 1 mg ml−1, Sigma) or biocytin (5-10 mm, Sigma) or neurobiotin (5-10 mm, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in the patch pipette solution. Methods for visualizing SPNs after filling with Lucifer Yellow have been described in detail previously (Pickering et al. 1991).

For visualization of neurones after filling with biocytin or neurobiotin, the following protocol modified from the work of Sah & McLachlan (1993) was used. Slices were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in PB for 1-2 h, washed thoroughly in 0.05 M Tris-saline, and incubated overnight in 1 % Triton in 0.05 M Tris-saline (Tris-Triton). Slices were subsequently incubated in 3 % H2O2 in 100 % methanol for 30 min, and then washed in Tris-Triton. After washing, slices were incubated in streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in 0.05 M Tris-saline, 1 % Triton X-100 and 3 % fish gelatin for 2 h. Slices were then washed in Tris-saline and subsequently in 0.1 M acetate buffer. Following rinsing, slices were reacted for staining with diaminobenzidine, nickel ammonium sulphate and hydrogen peroxide in acetate buffer for 7-10 min. Slices were rinsed in acetate buffer followed by Tris-saline, and dehydrated through a graded series of alcohol before being cleared in methylsalicylate for examination under a light microscope.

RESULTS

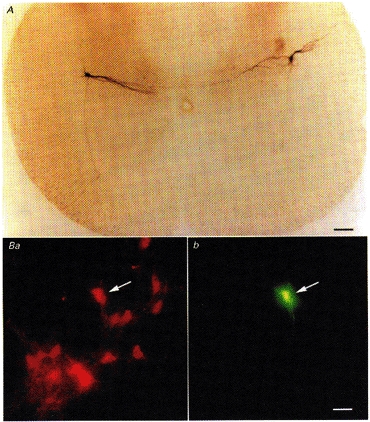

Intracellular recordings from sixty SPNs and whole-cell recordings from 130 SPNs were included in this study. Neurones recorded with intracellular pipettes were identified as SPNs by (1) their location in the IML and the presence of an antidromic action potential following stimulation of the ventral rootlets and (2) their characteristic membrane properties including a slow after-hyperpolarization potential or the presence of a marked rectification observed as a delay in the return to rest of the voltage response to a hyperpolarizing square-wave current pulse (Yoshimura, Polosa & Nishi, 1987; Spanswick & Logan, 1990; Pickering et al. 1991; Sah & McLachlan, 1995). Although characteristic membrane properties enabled SPNs to be identified, not all SPNs had such properties. In these instances, antidromic stimulation and criteria outlined below were used to identify SPNs. Neurones recorded with patch pipettes were also unambiguously identified as SPNs by their characteristic morphology revealed with Lucifer Yellow, biocytin or neurobiotin. SPNs had somata located in the IML, medially projecting dendrites and an axon that coursed ventrally towards the anterior horn or to exit the ventral rootlets (Fig. 1A). Fifty-two SPNs were also identified as projecting to the SCG by the presence of double labelling with Lucifer Yellow from the patch pipette and RDL from the SCG (Fig. 1Ba and Bb). No obvious differences were detected in the membrane properties of double-labelled SPNs compared with other positively identified SPNs, recorded at the same segmental levels in non-prelabelled slices. However, differences were detected in the properties of different SCG SPNs (D. Spanswick, L. P. Renaud & S. D. Logan, unpublished observations).

Figure 1. Intracellular and retrograde labels confirm identity of SPNs.

A, transverse section (450 μm) of thoracic spinal cord showing the characteristic morphology of intracellular biocytin-labelled SPNs. Two neurones are shown, one on either side of the slice. Note the characteristic medial dendrites, axons projecting ventrally and the location of the neurones in the lateral horn. Ba, transverse sections (25 μm) of thoracic spinal cord showing SPNs labelled with rhodamine-dextran-lysine (RDL), after injection into the superior cervical ganglion. Bb, the recorded neurone indicated with the arrow was also filled with Lucifer Yellow from the recording pipette, and therefore identified as innervating the superior cervical ganglion. Scale bars are 100 μm in A and 25 μm in B.

Sites of activation of synaptic responses

Fast EPSPs were evoked in SPNs by stimulation of the iLF, cLF, cIML, DH and ipsilateral dorsal rootlets (DR). Examples of evoked EPSPs and a schematic of the sites from which EPSPs were evoked are given in Fig. 2. Consistent with a monosynaptic origin, EPSPs evoked in SPNs, including SPNs innervating the SCG, showed graded responses to increased stimulation, constant rise times and no failures when challenged with high-frequency stimuli (10-20 Hz) (n= 71, 32, 41 and 45, respectively, for the iLF, cLF, cIML and DH; see Figs 2 and 3B and C). The mean latency and 10-90 % rise times of EPSPs recorded with patch electrodes were: 2.5 ± 0.2 and 4.9 ± 0.6 ms, respectively, for the iLF; 8.9 ± 0.4 and 6.0 ± 0.5 ms, respectively, for the cLF; 7.1 ± 0.2 and 6.1 ± 0.5 ms, respectively, for the cIML; and 3.2 ± 0.3 and 7.0 ± 1.9 ms, respectively, for the DH. Latencies were shorter and 10-90 % rise times faster when recorded with intracellular electrodes at 36°C than the corresponding values observed with patch electrodes at room temperature. Stimulation of the iLF evoked EPSPs with mean latency and 10-90 % rise time of 1.4 ± 0.1 ms and 2.5 ± 0.4 ms, respectively, with intracellular electrodes compared with 2.5 ± 0.2 and 4.9 ± 0.6 ms, respectively, with patch electrodes. Stimulation of the DH evoked EPSPs with mean latency and 10-90 % rise time of 1.6 ± 0.5 and 3.1 ± 0.5 ms, respectively, with intracellular electrodes compared with 3.2 ± 0.3 and 7.0 ± 1.9 ms, respectively, with patch electrodes. Table 1 summarizes the properties of EPSPs included in this study.

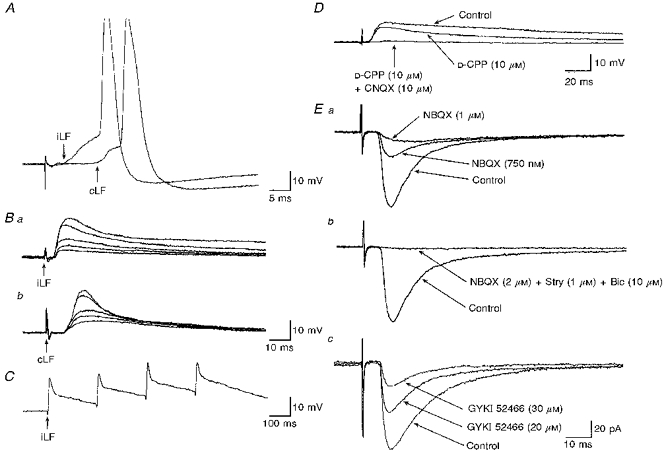

Figure 3. SPNs receive EAA receptor-mediated inputs from both sides of the spinal cord.

A, whole-cell recordings from a SPN (Vm, -56 mV) showing two superimposed EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the iLF and cLF. Stimulation of either of the lateral funiculi evoked EPSPs which reached threshold for firing. B, whole-cell recordings from the same SPN as in A showing the responses to increased stimulus intensity of the iLF (a) and cLF (b). Five superimposed records are shown for each stimulation site. Note the constant latency and rise times of the EPSPs, and the differences in the decay times of EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the iLF compared with the cLF. C, in the same neurone as A and B, EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the iLF showed no failures and a constant waveform in response to high-frequency stimulation. D, the role of glutamate receptors in synaptic transmission from the cLF. Three superimposed whole-cell recordings of EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the cLF (Vm, -58 mV). The EPSP (Control) was reduced in the presence of D-CPP and was completely abolished by subsequent addition of CNQX. E, the role of non-NMDA receptors in synaptic transmission. a, three superimposed records (Vhold, -60 mV) illustrate EPSCs, evoked by stimulation of the cIML, and their reduction in the presence of increasing concentrations of NBQX. b, data from the same neurone as above illustrate the reversed IPSC remaining in the presence of NBQX to be reduced by bicuculline (Bic) and strychnine (Stry). c, three superimposed recordings (Vhold, -60 mV) from another SPN illustrate EPSCs evoked by stimulation of the cLF, and their reduction in the presence of increasing concentrations of GYKI 52466. Traces represent the average of 16 responses.

Table 1.

Summary of properties of EPSPs and EPSCs evoked in SPNs

| Site of stimulation (electrode type) | n | Latency (ms) | EPSP amplitude (mV) | 10-90 % rise time (ms) | EPSP half-decay time (ms) | Peak current (pA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iLF (patch) | 54 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 75 ± 10 | 87 ± 17 |

| iLF (intracellular) | 17 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 25 ± 2 | — |

| DH (patch) | 34 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 7.0 ± 1.9 | 79 ± 16 | 65 ± 15 |

| DH (intracellular) | 11 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 11.7 ± 1.3 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 21 ± 7 | — |

| cLF (patch) | 32 | 8.9 ± 0.4 | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 63 ± 13 | 72 ± 16 |

| cIML (patch) | 41 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 63 ± 7 | 80 ± 13 |

Whole-cell recordings were obtained at room temperature (17-20 °C) and intracellular recordings at 35 °C. Peak amplitudes of responses were estimated as the amplitude just below threshold for firing or the amplitude reached before subsequent increases in stimulus intensity resulted in no significant change. Corresponding peak current was measured at holding potentials close to resting membrane potentials of between -55 and -70 mV. Results are expressed as means ±s.d. iLF, ipsilateral lateral funiculus; cLF, contralateral lateral funiculus; DH, dorsal horn; cIML, contralateral intermediolateral cell nucleus.

EPSPs evoked by stimulation at these sites could give rise to action potential firing (Fig. 3A). EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the iLF, cLF, cIML, DH or DR were blocked in the presence of low-calcium, high-magnesium bathing medium (n= 3, 3, 3, 2 and 1 neurones, respectively) suggesting they were the product of calcium-dependent synaptic transmission. Stimulation of the DR evoked EPSPs of variable latency suggesting a polysynaptic origin. Generally, EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the DH had slower rise times compared with those of the iLF, cLF and cIML. iLF-evoked EPSPs had faster rise times than those from the cIML and cLF. cLF- and cIML-stimulated EPSPs were similar in terms of rise and decay times suggesting the same pathways were recruited when stimulating these sites. Polysynaptic responses were evoked in some SPNs by stimulation of the cLF, cIML and LF. Unlike the monosynaptic inputs, these responses were of variable latency and prone to failure, presumably indicating recruitment of fibres or axon collaterals innervating one or more interneurones presynaptic to SPNs.

Identification of non-NMDA receptor-mediated components of synaptic transmission from the lateral funiculi and cIML

The effects of EAA-receptor antagonists were tested on monosynaptic EPSPs and EPSCs evoked by low-frequency (0.03-0.1 Hz) stimulation of the iLF (n= 18), cLF (n= 10) and cIML (n= 12). In all neurones, the initial fast-rising and decaying component of the EPSP or EPSC, observed at holding potentials close to resting membrane potentials of between -55 and -70 mV, was reduced in the presence of CNQX (2-20 μm, n= 23), NBQX (1-2 μm, n= 14) or GYKI 52466 (20-30 μm, n= 3) (Fig. 3D and E). The order of antagonist potency was NBQX > CNQX > GYKI 52466. In two SPNs, concentrations of GYKI 52466 up to 30 μm failed to block completely the fast EPSP or EPSC (Fig. 3Ec). In several SPNs a bicuculline- and/or strychnine-sensitive component of synaptic transmission remained. To eliminate contamination of EPSPs and EPSCs with concurrently activated inhibitory amino acid-mediated synaptic responses, bicuculline (10 μm) and strychnine (1-2 μm) were routinely included in the ACSF unless otherwise indicated. Non-NMDA receptor antagonists completely blocked the fast EPSP or EPSC in 56 % (n= 10 of 18) of responses evoked from the iLF, 60 % (n= 6 of 10) evoked from the cLF and 50 % (n= 6 of 12) evoked from the cIML. Hence around one-half of responses, evoked at low frequency, appeared to have little or no involvement of NMDA receptors. However, in all of these neurones, superfusion with magnesium-free bathing medium uncovered EPSPs or EPSCs with slower rise times and longer decay times (Fig. 4C). Their NMDA receptor-mediated basis was confirmed by the sensitivity of the response to D-CPP (5-20 μm, Fig. 4Cb) or DL-APV (20-50 μm).

Figure 4. Differential roles for NMDA receptors in synaptic transmission to SPNs.

A, NMDA receptor-mediated components of synaptic transmission during low-frequency stimulation varied between SPNs. a, EPSPs evoked by low-frequency (0.03 Hz) stimulation of the iLF displayed a biphasic decay characterized by an initial fast decay from the peak response followed by a slower decay. b, in the presence of the non-NMDA receptor antagonist NBQX, the fast rising phase was blocked and an EPSP, with slower rise time, remained. C, subsequent inclusion of the NMDA receptor antagonist D-CPP completely blocked the remaining EPSP. B, three superimposed whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from the same neurone as in A illustrate that the initial fast inward current component of the EPSC was blocked by NBQX, leaving an EPSC with a slower rise time. This EPSC was completely blocked by D-CPP. C, in some SPNs an NMDA component of synaptic transmission was only apparent, during low-frequency stimulation, in magnesium-free bathing medium. a, two superimposed whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from an SPN showing an EPSC (Control), evoked by stimulation of the cIML, to be completely blocked following superfusion of a combination of NBQX and strychnine and bicuculline (the latter agents being used to block any contaminating IPSCs). b, the same neurone showing that superfusion of the same antagonist cocktail as above in magnesium-free bathing medium revealed a slower rising EPSC that was subsequently blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonist D-CPP. Note that the records shown in B and C were obtained at identical holding potentials (-60 mV). Each record shown here is the average of 16 responses.

Identification of NMDA receptor-mediated components of synaptic transmission from the lateral funiculi and cIML

A prominent NMDA receptor-mediated component of synaptic transmission was apparent during low-frequency stimulation in 44 % (n= 8 of 18) of EPSPs and EPSCs evoked from iLF, 40 % (n= 4 of 10) from cLF and 50 % (n= 6 of 12) from cIML in the presence of normal levels of magnesium (1.3 mm) (Figs. 3D, 4A and B, 5A and B). The resting membrane potentials of these neurones, including fifteen neurones identified as innervating the SCG, were similar to those neurones where little or no NMDA receptor-mediated component was apparent. This suggests that the presence of the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSP was not due to different extents of voltage-dependent blockade of the receptor related to resting membrane potential. This notion is supported further by observations made under voltage-clamp conditions at identical holding potentials. In one group of SPNs the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC was absent until removal of magnesium from the bathing medium, whereas in others a clear NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC was present (Fig. 4B and C). In this latter group of SPNs, bath application of the NMDA receptor antagonists D-CPP (5-20 μm, n= 15) or DL-APV (20-50 μm, n= 3) reduced the late decay phase of the EPSP or EPSC and in some instances reduced the peak amplitude of the response. The NMDA component of the EPSP or EPSC did not require pre- or coactivation of non-NMDA receptors to be evoked, although it was always associated with such. Following blockade of the fast component of the EPSP or EPSC with NBQX or CNQX, a slower rising and long lasting EPSP or EPSC remained, that in all neurones tested was confirmed as NMDA receptor mediated by its sensitivity to D-CPP (Figs 4A and B and 5A, n= 12). These EPSPs and EPSCs had constant latencies, waveforms and rise times (Fig. 5A and B), could reach threshold for firing, and showed a constant latency and no failures in response to high-frequency stimulation (Fig. 5C).

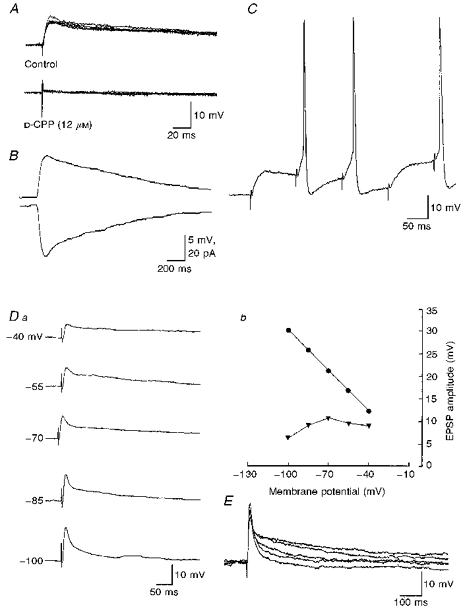

Figure 5. Properties of NMDA receptor-mediated components of synaptic transmission.

Properties of pharmacologically isolated NMDA receptor-mediated components observed during low-frequency stimulation. A, whole-cell current clamp recordings of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the iLF. Upper records show five superimposed EPSPs. Note the constant latency and rise time of the response. Below, four superimposed recordings from the same neurone as above showing EPSPs to be completely blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonist D-CPP. B, same neurone as A showing the waveform of the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSP (above, Vrest, -62 mV) and below the corresponding EPSC (Vhold, -62 mV). Note records shown here are the average of 16 responses. C, the NMDA receptor-mediated component of synaptic transmission showed no failures on repetitive stimulation, and could reach threshold for firing. D, voltage dependence of EPSPs. a, whole-cell current clamp recordings from a SPN showing the effects of changes in membrane potential on EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the iLF. Each record is the average of 8 EPSPs. The neurone was held at the membrane potentials indicated by the passage of constant negative current via the electrode. As illustrated graphically on the right (b) the peak amplitude of the EPSP (circles) increases whereas the amplitude at 100 ms (triangles) decreased at membrane potentials between -70 and -100 mV. E, five superimposed whole-cell current clamp recordings of EPSPs evoked in another SPN following stimulation of the iLF reflect responses obtained at holding potentials of -60, -70, -80, -90 and -100 mV. Note the increase in peak amplitude but decrease in the later component of the EPSPs with increased membrane hyperpolarization. Each record is the average of 4 EPSPs evoked at each holding potential.

To test the voltage sensitivity of EPSPs, we investigated the effects of changes in membrane potential on EPSPs evoked by stimulation of iLF in the presence of 1.3 mm extracellular magnesium (n= 6). We measured both the peak amplitude and EPSP amplitude at between 50 and 150 ms after the onset of the response. The latter times were chosen as they were as close to the time to peak amplitude of the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs as possible without inclusion of the non-NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic response. The initial peak amplitude of the EPSP increased in amplitude with increased membrane hyperpolarization from -55 to -110 mV in three SPNs. However, in these neurones, the amplitude of the EPSP at 50-150 ms after the onset of the response initially showed a small increase, followed by a subsequent decrease in amplitude with increased membrane hyperpolarization (Fig. 5Da and E). The data from Fig. 5Da are shown graphically in Fig. 5Db. In the remaining SPNs both the peak amplitude of the EPSP and the amplitude measured 50 ms after the onset of the response increased with increased membrane hyperpolarization.

NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs are revealed by, and EPSPs potentiated following, high-frequency stimulation

The receptors mediating EPSPs evoked in response to high-frequency stimulation (10-20 Hz, 0.1-2 s) of the iLF, cLF and cIML (n= 12, 6 and 8 neurones, respectively) were investigated. High-frequency stimulation of these areas evoked complex synaptic responses comprising summating EPSPs superimposed on a depolarizing shift that could reach threshold for firing (Fig. 6A). Complex EPSPs lasted for time periods of one up to several seconds. In addition, late slow EPSPs or IPSPs lasting several tens of seconds were also evoked that were sensitive to prazosin and yohimbine, respectively, and both late slow responses were sensitive to phentolamine (data not shown). D-CPP or DL-APV reduced these complex EPSPs in all neurones tested (Fig. 6Ab), including SPNs with little or no apparent NMDA receptor-mediated component during low-frequency stimulation. The remaining components of the response were blocked by CNQX or NBQX, and strychnine and/or bicuculline.

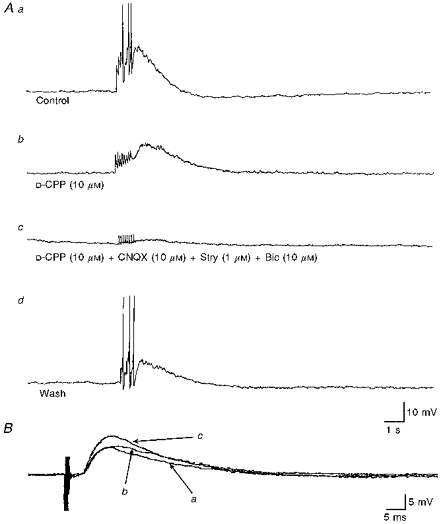

Figure 6. NMDA receptor-mediated components of synaptic transmission revealed by, and EPSPs potentiated following, high-frequency stimulation.

A, the effects of NMDA receptor antagonists were tested on EPSPs evoked by high-frequency stimulation of the lateral funiculi. a, high-frequency stimulation (10 Hz, 1 s) of the iLF evoked, in this SPN, a complex synaptic response comprised several summating EPSPs, which reached threshold for firing, followed by an IPSP. b, the NMDA receptor antagonist D-CPP reduced the complex EPSP revealing a series of small fast EPSPs followed by a slower prolonged EPSP. c, the remaining fast EPSPs and slow EPSP were blocked by a combination of CNQX, strychnine and bicuculline. d, these effects were at least partly reversible on washout of the drugs. B, potentiation of EPSPs following high-frequency stimulation. Three superimposed intracellular records showing EPSPs evoked during low-frequency stimulation (0.01 Hz) of the iLF, before (a), immediately following (B), and 5 min after (c) delivery of a brief high-frequency stimulation (10 Hz, 1 s). The initial decaying phase was observed to be enhanced at first, and within 5 min the peak amplitude of the EPSP was potentiated. Each record is the average of 16 trials.

The effects of a brief high-frequency stimulation (10-20 Hz, 0.1-2 s) on the peak amplitude of EPSPs evoked by low-frequency stimulation (0.05-0.1 Hz) of the iLF were tested in SPNs recorded with intracellular electrodes at resting membrane potentials between -55 and -65 mV (n= 14). In six SPNs the EPSP was observed to be enhanced in amplitude following delivery of the high-frequency stimulation (Fig. 6B). The potentiation of the EPSP was sustained over the time course of recording (up to 70 min). The mean increase in the amplitude of the EPSP in these SPNs was 25.3 ± 11.4 %, ranging between 12 and 42 %. The remaining SPNs showed no significant increase in the peak amplitude of the EPSP, and in two neurones a suppression of the peak amplitude was observed following the high-frequency stimulation.

Properties of DH-evoked EPSPs

EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the DH were characterized by a slow rise time compared with those of the iLF, observed with intracellular and patch electrodes, and slower rising EPSPs compared with contralateral sites of stimulation. This suggests that inputs activated by stimulation of DH contact SPNs at a site more distal to the recording electrode than iLF, cLF or cIML.

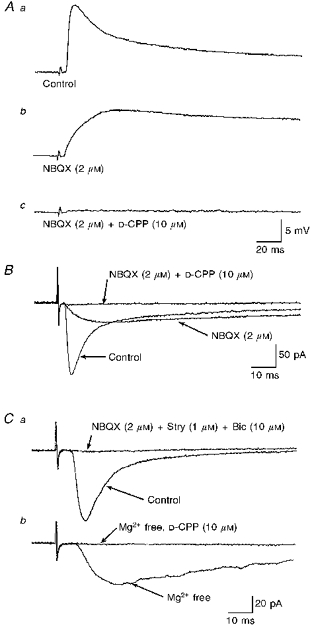

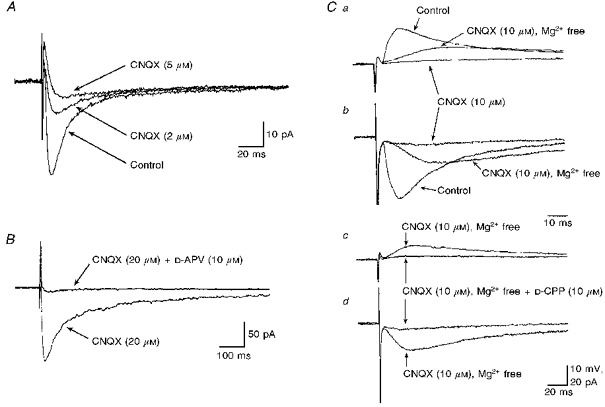

The effects of EAA-receptor antagonists were tested on EPSPs evoked by stimulation, at low frequency (0.03-0.1 Hz), of the DH. Bath application of CNQX (5-20 μm) attenuated the EPSP or EPSC in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7A) in all neurones tested (n= 20). In nine SPNs the EPSP or EPSC observed in voltage clamp at holding potentials close to resting membrane potentials of between -55 and -70 mV was completely blocked by this antagonist (Fig. 7C). D-CPP or D-APV attenuated the synaptic response in four neurones, and subsequent addition of CNQX abolished the remainder of the response in these neurones. In seven SPNs, a prominent EPSP or EPSC remained in the presence of CNQX or NBQX. This synaptic response was of large amplitude, ranging between 8 and 19 mV when recorded in current clamp at rest, and 75-160 pA under voltage-clamp conditions close to resting membrane potentials between -60 and -70 mV. This synaptic response was also of long duration, ranging between 600 and 1200 ms, and could reach threshold for firing. Bath application of D-CPP or D-APV markedly attenuated the EPSP or EPSC (Fig. 7B), by as much as 95 % of control, recorded in the presence of CNQX. In SPNs in which the EPSP was completely blocked by CNQX, subsequent superfusion of magnesium-free bathing medium revealed an EPSP or EPSC with a slower rise time and longer duration than the CNQX-sensitive component. The EPSP or EPSC observed under these conditions was completely blocked by D-CPP (10 μm, n= 7) or DL-APV (20-50 μm, n= 2) (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. DH-evoked responses are differentially mediated by both non-NMDA and NMDA receptors.

Non-NMDA and NMDA receptors differentially mediate excitatory synaptic transmission evoked in SPNs by stimulation of DH. A, a prominent non-NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC. Three superimposed records showing the progressive concentration-dependent suppression of the EPSC by CNQX. Each record is the average of 16 trials. B, a prominent NMDA receptor-mediated component of synaptic transmission in another SPN. Two superimposed records showing stimulation of the DH in the presence of CNQX evoked an EPSC that was markedly attenuated by D-CPP. Each record is the average of 8 trials. C, NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs and EPSCs uncovered in magnesium-free bathing medium. DH-evoked EPSPs (a) and the corresponding EPSCs (b) were completely blocked by addition of CNQX. Subsequent removal of magnesium from the bathing medium uncovered a slower EPSP or EPSC. This EPSP (c) and EPSC (d) evoked in CNQX-containing magnesium-free bathing medium was almost completely blocked after addition of D-CPP.

DISCUSSION

Excitatory synaptic inputs to SPNs

We have presented here, for the first time in an in vitro slice preparation, data of synaptic inputs to SPNs whose target is known. SPNs projecting to the SCG were identified, the SCG being the site of origin of sympathetic postganglionic neurones that innervate diverse target organs in the head, neck and upper abdomen. We also present evidence for the first time that SPNs receive direct monosynaptic inputs from ipsilateral and contralateral locations. Failure to produce synaptic responses from areas other than the contralateral sites of stimulation (e.g. contralateral dorsal and ventral horns) negates the argument that responses evoked here were due to artefactual current spread.

Intracellular versus whole-cell recording of EPSPs

Both intracellular and whole-cell recording techniques were employed in this study. Generally, the main differences in properties of EPSPs observed with intracellular electrodes at 35°C were faster rise and decay times compared with the corresponding parameters observed with patch electrodes. The longer decay of the EPSP observed with patch electrodes is presumably partly related to the longer membrane time constant and associated increased input resistance recorded with patch pipettes as a result of the improved cell-electrode seal (see Pickering et al. 1991), and partly related to the temperature difference. The time course of decay of EPSPs in some SPNs was within the range of membrane time constants measured in these neurones, indicating that the synaptic current flow was comparatively quick. However in around 45 % of SPNs, the time course of decay of the EPSPs was longer than the membrane time constant, this being at least partly due to the responses being mediated by NMDA receptors. The differences in pharmacological profile of synaptic responses were independent of recording method.

Origins of ipsi- and contralaterally evoked monosynaptic EPSPs

Stimulation of the cLF, cIML and iLF evoked monosynaptic EPSPs and EPSCs in all neurones tested, including SPNs innervating the SCG, indicating that SPNs receive inputs from both sides of the spinal cord. No significant differences in the properties and pharmacology of EPSPs were detected in SCG SPNs compared with non-prelabelled SPNs. That these connections are monosynaptic is indicated by the fact that stimulation of the cLF, iLF or cIML evoked EPSPs that showed a consistent latency and rise time, and no failures and a consistent waveform in response to high-frequency stimulation. cIML- and cLF-stimulated responses were generally similar in terms of rise and decay time, suggesting the same pathways were being activated. The latency and monosynaptic nature of the responses from cLF and cIML suggest direct activation of pathways originating in the contralateral spinal cord rather than activation of polysynaptic segmental circuits via axon collateral and interneurones. This is further suggested by the slower rise times of the DH-evoked responses that probably involve such interneurones, the slow rise time indicating sites of contact more distal to the recording electrode than the faster rising cIML- and cLF-evoked responses. A similar observation has been made for iLF- and DH-evoked EPSPs by others (Krupp & Feltz, 1995).

Descending inputs to SPNs from higher centres project through the lateral funiculi, from where they branch at right angles towards the SPNs and the IML (Anderson, McLachlan & Srb-Christie, 1989). EPSPs described here are therefore likely to include those of supraspinal origin. That this is the case is further suggested by the fact that in addition to these EPSPs, slow EPSPs and IPSPs sensitive to prazosin and yohimbine, respectively, and phentolamine were often evoked along with the fast EPSPs. The origin of these catecholamine-mediated inputs is known to be supraspinal (see Coote, 1988). In addition, we have evoked qualitatively and quantitatively similar synaptic responses in a longitudinal spinal slice preparation by stimulation of iLF and cLF, at distances of several milliimetres away from the site or segment of recording, suggesting recruitment of fibres or pathways originating from both sides of the spinal cord (Spanswick, Renaud & Logan, 1995).

Since EPSPs evoked following iLF, cLF and cIML stimulation had similar and fast rise times it would appear that all of these inputs are close to the recording site (viz. the soma). This supports the notion that fibres arising from contralateral locations project close to SPN somata. Bilateral influences on SPNs from higher centres have been previously shown or suggested from both anatomical and physiological studies, particularly in relation to adrenal function (Carlsson, Falck, Fuxe & Hillarp, 1964; Dahlstrom & Fuxe, 1965; Taylor & Brody, 1976; Gauthier, Gagner & Sourkes, 1979; Francke, Culberson, Carmichael & Robinson, 1982; Stoddard, Bergdall, Townsend & Levin, 1986a, b), although these studies did not unequivocally determine the nature of the transmitter involved.

Although stimulation of the iLF, cIML and cLF undoubtedly recruited fibres of supraspinal origin, recruitment or contamination of these responses with inputs from other sources is also likely. These sources include neurones originating in the lateral funiculi of the white matter itself, that also bilaterally project towards SPNs (Jansen & Loewy, 1997), and propriospinal and ascending inputs, likely to be recruited when stimulating the iLF (e.g. see Akeyson & Schramm, 1994). Polysynaptic inputs were apparent when stimulating the iLF, cIML and cLF, suggesting we were activating segmental circuits involving interneurones, presumably located in laminae I, IV, V, VII or IX (Strack et al. 1989; Craig, 1993; Cabot et al. 1994), in addition to pathways directly innervating SPNs. In our study, therefore, inputs activated by stimulation of the cLF, cIML and iLF could comprise combinations of descending inputs from higher centres, inputs originating in the LF of the white matter itself and possibly a contribution from ascending inputs, particularly in the case of iLF stimulation.

SPNs are known to extend medial dendrites into the contralateral spinal cord (Forehand, 1990; Vera, Hurwitz & Schneiderman, 1990). Therefore the possibility arises of cIML- and cLF-stimulated inputs regulating SPNs located in the contralateral IML through their medially projecting dendrites. However in our study this does not appear to be the case as SPNs examined after recording had medial dendrites that did not extend to the contralateral spinal cord, and yet postsynaptic responses were readily evoked in these neurones by stimulation of the cIML or cLF. Furthermore, the latencies associated with EPSPs evoked from the cLF and cIML suggest that the fibres carrying the contralateral inputs extend across the cord to synapse on SPNs, and do so monosynaptically rather than polysynaptically via axon collaterals and interneurones. This notion is supported by the fast rise time of the contralateral synaptic responses, faster than the dorsal horn. One implication of our results, together with previous anatomical studies demonstrating that descending inputs project through the lateral funiculi, from where they branch at right angles towards SPNs and the ipsilateral IML and extend contralaterally towards the contralateral IML (e.g. see Anderson et al. 1989), is that SPNs on either side of the spinal cord may receive the same inputs. This may be important in synchronizing SPNs, and hence the outflow to the periphery.

Role of NMDA and non-NMDA receptors in synaptic transmission

Data presented here, using both conventional intracellular and whole-cell recording techniques, suggest a role for both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors in synaptic transmission in all pathways studied, i.e. the DH, cLF and cIML, and the iLF. This conclusion is based on the sensitivity of EPSPs to EAA-receptor antagonists. A role for non-NMDA receptors in mediating a fast EPSP from both sides of the spinal cord was demonstrated by the sensitivity of the EPSP and EPSC to the selective antagonists NBQX, CNQX and GYKI 52466. These antagonists suppressed the early fast EPSP and EPSCs in all neurones, with NBQX being the most, and GYKI 52466 the least effective of these antagonists. That non-NMDA (AMPA/kainate) receptors mediate a fast synaptic response when elicited from the iLF is in agreement with previous studies (Shen et al. 1990; Inokuchi et al. 1992; Krupp & Feltz, 1995; Sah & McLachlan, 1995). However, the relative contribution of NMDA receptors to synaptic transmission elicited from the iLF has remained somewhat unclear. An investigation in neonatal rat transverse spinal cord slices suggested an exclusive role for non-NMDA receptors in pathways projecting from the iLF and NMDA receptors exclusive to pathways elicited from the DH (Shen et al. 1990). However, data presented here, and by others in the neonatal rat (Krupp & Feltz, 1995) and adult cat (Inokuchi et al. 1992), suggest a dual role for both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors. Similarly in early neonatal animals, dual-component EPSPs were evoked in SPNs by stimulation of the ventrolateral medulla (Deuchars et al. 1995). In the present study, a role for NMDA receptors in low-frequency synaptic transmission in pathways from the cLF and cIML, and the iLF is suggested by the sensitivity of EPSPs to the selective NMDA receptor antagonists D-CPP or D-APV. In SPNs described here, these antagonists suppressed EPSPs or EPSCs evoked from the cLF, cIML or iLF by as much as 90 % of control, leaving unaffected an associated fast EPSP. In other SPNs, no NMDA receptor-mediated component was apparent during low-frequency stimulation but was uncovered in magnesium-free bathing medium, or on high-frequency stimulation.

Differential role for NMDA receptors

Our data raise an interesting issue of a differential role for NMDA receptors in synaptic transmission from pathways originating from both sides of the spinal cord. Low-frequency stimulation of the iLF, cLF or cIML evoked EPSPs or EPSCs that were markedly suppressed by NMDA receptor antagonists. Suppression of this synaptic component, including the peak of the response, could prevent threshold for firing being achieved, even on high-frequency stimulation. This NMDA component, which comprised much of the late component of the synaptic response, was voltage sensitive. The voltage sensitivity was relieved by removal of magnesium from the bathing medium. These observations are consistent with the voltage-dependent block of NMDA receptors by magnesium described previously in SPNs (Shen et al. 1990; Spanswick & Logan, 1990; Inokuchi et al. 1992; Krupp & Feltz, 1995), and on other central neurones (Mayer, Westbrook & Guthrie, 1984; Nowak, Bregestovski, Ascher, Herbert & Prochiantz, 1984). Pharmacological isolation of this NMDA receptor-mediated component of synaptic transmission elicited from the iLF, cLF or cIML revealed an EPSP or EPSC in normal magnesium-containing bathing medium that showed a constant latency and rise time and no failures in response to high-frequency stimulation, and could reach threshold for firing, conclusive evidence of a monosynaptic role for NMDA receptors in SPNs. It is also interesting that this type of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSP did not require coactivation of non-NMDA receptors to relieve the magnesium block, although it was always observed concurrently with a non-NMDA receptor-mediated component of synaptic transmission. In SPNs where an NMDA receptor-mediated EPSP was not readily apparent during low-frequency stimulation, over a similar range of resting membrane and holding potentials, such a component was revealed in magnesium-free bathing medium and on high-frequency stimulation. Similar observations have been extensively documented in hippocampus where NMDA receptors are thought to contribute little to a subthreshold EPSP at rest in normal magnesium-containing bathing medium, but are observed during high-frequency stimulation, during low-frequency stimulation in the absence of magnesium or with the cell depolarized (see Collingridge & Lester, 1989). The properties of the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs observed in the presence of normal magnesium-containing and magnesium-free bathing medium were also markedly different in that one could only be observed following omission of magnesium. Furthermore, the EPSP observable in the presence of magnesium was prolonged, lasting for hundreds of milliseconds when observed with patch electrodes at room temperature. The differences in these EPSPs could be explained in several ways. Firstly, there may be different numbers of postsynaptic NMDA receptors involved at the synapses activated in different SPNs, such that EPSPs with extensive NMDA receptor-mediated components during low-frequency stimulation express a higher number of receptors that could contribute to the response. Secondly, differential expression of NMDA receptor subunits constituting the channel may occur, providing the channel with a differing magnesium-dependent voltage sensitivity. Regional variations in the slice of the availability of, or ability to retain, magnesium may also be an issue, although unlikely in view of the voltage and magnesium sensitivity of the responses. Finally, the site of the synaptic inputs relative to the recording site may vary such that the cable properties of SPNs, which posses long medial dendrites, distort the signal in some instances. However in view of the slow kinetics of these NMDA receptor-mediated responses, and the fact that our data suggest these inputs are proximal to the recording site, presumably the soma, we believe that the latter is also unlikely. The fact that the different types of synaptic response were obtained using both recording methods, were observed in the same series of slices and in some instances the same slice, and observed in SPNs with a common target, i.e. the SCG, indicates that the different types of response do not reflect a pathological situation.

The physiological relevance of this variable role of NMDA receptors is unclear. The differences may be related to the target and function of this diverse and heterogeneous population of neurones. In relation to this, both types of NMDA receptor-mediated response were observed to occur in different SCG SPNs, a population of neurones heterogeneous in terms of function and membrane properties. One well documented role for NMDA receptors is in synaptic plasticity (see Collingridge & Lester, 1989). In this respect we have demonstrated, for the first time, potentiation of EPSPs following high-frequency stimulation in a proportion of SPNs, a protocol often employed to induce long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampus, and potentiation of EPSPs by nitric oxide, acting as a retrograde signaller following liberation in SPNs, has recently been shown (Wu & Dun, 1995). It may be that these NMDA receptors are important in the plasticity in SPNs in which enhanced synaptic efficiency is required, for example under conditions of stress. Finally, the long time course of the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSP in normal magnesium may be an important mechanism for temporal and spatial summation and facilitation of other excitatory inputs from more distal sites, functioning in response to short-term, moment by moment demands for regulation of the internal enviroment.

Dorsal horn-evoked EPSPs

EPSPs and EPSCs evoked by stimulation of the DH displayed a constant latency and rise time, and constant waveform, latency and no failures in response to high-frequency stimulation, indicating that these inputs were monosynaptically generated. Our data suggest that DH-evoked inputs to SPNs are mediated by both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors, and in some instances predominantly by the latter class. These data are in partial agreement with previous data in the neonatal rat (Krupp & Feltz, 1995) that demonstrated predominantly dual-component EPSPs. However, the extent of involvement of NMDA receptors in these pathways appears to vary considerably between SPNs. In some instances the charge carried by the EPSC is largely mediated through NMDA receptors, though not exclusively, indicated by data described here and previously by others (Krupp & Feltz, 1995). On the other hand the present study reveals that a predominantly non-NMDA receptor-mediated EPSP or EPSC can be observed, and in these neurones an NMDA receptor-mediated component was revealed in magnesium-free bathing medium. These observations suggest a similar situation to that observed with the pathways activated by stimulation of the cLF, cIML and iLF, i.e. a differential role for NMDA receptors. However, in this instance variations may be due to different stimulating electrode placements in the DH, the DH being a larger and more diffuse target for such placements than the funiculi or the IML. The stimulus may therefore have activated, in some instances, different pathways. Furthermore, exactly what is stimulated from the DH is unclear. As a monosynaptic input to SPNs via the dorsal roots has yet to be demonstrated, we were presumably activating interneurones that were monosynaptic with SPNs. Interneurones projecting to SPNs have been localized to spinal laminae I, IV, V, VII and IX (Strack et al. 1989; Craig, 1993; Cabot et al. 1994). Fibres originating in laminae I, IV and V were within the range of stimulation sites targeted by our study. Our data therefore suggest a role for excitatory interneurones projecting to SPNs, situated in dorsal laminae I, IV or V, using glutamate as a neurotransmitter acting via both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors.

In conclusion, our results indicate that SPNs, including SPNs innervating the SCG, receive monosynaptic connections from both sides of the spinal cord. The neurotransmitter mediating transmission is glutamate acting via both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors. Our data also suggest a differential expression of NMDA receptors by SPNs, and that in some SPNs, glutamate receptor-mediated EPSPs can be potentiated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada, The Canadian MRC, the British Heart Foundation and The Wellcome Trust. We would like to thank Dr Michael Hermes for help with the biocytin processing, Elaine Corderre and Paula Richardson for technical assistance and Dr I. Gibson for comments and help with the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Akeyson EW, Schramm LP. Processing of splanchnic and somatic input in thoracic spinal cord of the rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:R257–267. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.1.R257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CR, McLachlan EM, Srb-Christie O. Distribution of sympathetic preganglionic neurons and monoaminergic nerve terminals in the spinal cord of the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;283:269–284. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman SB, Henry JL. Effects of glutamate and aspartate on sympathetic preganglionic neurones in the upper thoracic intermediolateral nucleus of the cat. Brain Research. 1983;277:370–374. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabot JB, Alessi V, Carroll J, Ligorio M. Spinal cord lamina V and lamina VII interneuronal projections to sympathetic preganglionic neurones. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994;347:515–530. doi: 10.1002/cne.903470404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Falck B, Fuxe K, Hillarp N-A. Cellular localisation of monoamines in the spinal cord. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1964;60:112–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1964.tb02874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, Kaneko T. Phosphate-activated glutaminase immunoreactive synapses in the intermediolateral nucleus of rat thoracic spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1993;57:823–831. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90027-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Lester RAJ. Excitatory amino acid receptors in the vertebrate central nervous system. Pharmacological Reviews. 1989;40:143–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coote JH. The organization of cardiovascular neurones in the spinal cord. Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology. 1988;110:148–285. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. Propriospinal input to thoracolumbar sympathetic nuclei from cervical and lumbar lamina I neurons in the cat and monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;331:517–530. doi: 10.1002/cne.903310407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrom A, Fuxe K. Evidence for the existence of monoamine-containing neurones in the central nervous system. II. Experimentally induced changes in intraneuronal amine levels of bulbospinal neurone systems. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1965;64(suppl. 247):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembowsky K, Czachurski J, Seller H. An intracellular study of the synaptic input to sympathetic preganglionic neurones of the third thoracic segment of the cat. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1985;13:201–244. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(85)90012-8. 10.1016/0165-1838(85)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuchars SA, Morrison SF, Gilbey MP. Medullary-evoked EPSPs in neonatal rat sympathetic preganglionic neurones in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:453–463. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand CJ. Morphology of sympathetic preganglionic neurones in the neonatal rat spinal cord: an intracellular horseradish peroxidase study. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;298:334–342. doi: 10.1002/cne.902980306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francke PF, Culberson JL, Carmichael SW, Robinson RL. Bilateral secretory responses of the adrenal medulla during stimulation of hypothalamic or mesencephalic sites. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1982;8:1–6. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490080102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S, Gagner J-P, Sourkes TL. Role of descending spinal pathways in the regulation of adrenal tyrosine hydroxylase. Experimental Neurology. 1979;66:42–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90061-x. 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuchi H, Yoshimura M, Yamada S, Polosa C, Nishi S. Fast excitatory postsynaptic potentials and the responses to excitant amino acids of sympathetic preganglionic neurones in the slice of the cat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1992;46:657–667. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90152-r. 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90152-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen ASP, Loewy AD. Neurons lying in the white matter of the upper cervical spinal cord project to the intermediolateral cell column. Neuroscience. 1997;77:889–898. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)86660-2. 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)86660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp J, Feltz P. Excitatory postsynaptic currents and glutamate receptors in neonatal rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:1503–1512. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskey W, Polosa C. Characteristics of the sympathetic preganglionic neurone and its synaptic input. Progress in Neurobiology. 1988;31:47–84. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(88)90022-6. 10.1016/0301-0082(88)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Phend KD, Minson JB, Pilowsky PM, Chalmers JP. Glutamate-immunoreactive synapses on retrogradely-labelled sympathetic preganglionic neurones in rat thoracic spinal cord. Brain Research. 1992;581:67–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90345-a. 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90345-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL, Guthrie PB. Voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ of NMDA responses in spinal cord neurones. Nature. 1984;309:261–263. doi: 10.1038/309261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SF, Callaway J, Milner TA, Reis DJ. Glutamate in the spinal sympathetic intermediolateral nucleus: localisation by light and electron microscopy. Brain Research. 1989;503:5–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91696-x. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91696-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SF, Ernsberger P, Milner TA, Callaway J, Gong A, Reis DJ. A glutamate mechanism in the intermediolateral nucleus mediates sympathoexcitatory responses to stimulation of the rostral ventrolateral medulla. In: Ciriello J, Caverson MM, Polosa C, editors. The Central Neural Organization of Cardiovascular Control. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989. pp. 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak L, Bregestovski P, Ascher P, Herbert A, Prochiantz A. Magnesium gates glutamate-activated channels in mouse central neurones. Nature. 1984;307:462–465. doi: 10.1038/307462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering AE, Spanswick D, Logan SD. Whole-cell recording from sympathetic preganglionic neurones in rat spinal cord slices. Neuroscience Letters. 1991;130:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90405-i. 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90405-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, McLachlan EM. Differences in electrophysiological properties between neurones of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in rat and guinea-pig. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1993;42:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90041-r. 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90041-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, McLachlan EM. Membrane properties and synaptic potentials in rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons studied in horizontal spinal cord slices in vitro. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1995;53:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00161-c. 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00161-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen E, Mo N, Dun NJ. APV-sensitive dorsal root afferent transmission to neonate rat sympathetic preganglionic neurones in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;64:991–999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.3.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanswick D, Logan SD. Sympathetic preganglionic neurones in neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: electrophysiological characteristics and the effects of selective excitatory amino acid receptor agonists. Brain Research. 1990;525:181–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90862-6. 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanswick D, Renaud LP, Logan SD. Descending synaptic inputs to rat sympathetic preganglionic neurones in a longitudinal spinal cord slice preparation. Journal of Physiology. 1995;489.P:157 P. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SL, Bergdall VK, Townsend DW, Levin BE. Plasma catecholamines associated with hypothalamically-elicited defence behaviour. Physiology and Behavior. 1986a;36:867–873. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90445-2. 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SL, Bergdall VK, Townsend DW, Levin BE. Plasma catecholamines associated with hypothalamically-elicited flight behaviour. Physiology and Behavior. 1986b;37:709–715. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90176-9. 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack AM, Sawyer WB, Hughes JH, Platt KB, Loewy AD. A general pattern of CNS innervation of the sympathetic outflow demonstrated by transneuronal pseudorabies viral infections. Brain Research. 1989;491:156–162. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90098-x. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90098-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DG, Brody MJ. Spinal adrenergic mechanisms regulating sympathetic outflow to blood vessels. Circulation Research. 1976;38:10–20. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.6.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera PL, Hurwitz BE, Schneiderman N. Sympathoadrenal preganglionic neurons in the adult rabbit send their dendrites into the contralateral hemicord. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1990;30:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90250-m. 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90250-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana F, Gibbs L, Berger AJ. Double- and triple-labelling of functionally characterized central neurons projecting to peripheral targets studied in vitro. Neuroscience. 1990;38:829–84. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90075-f. 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90075-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Dun NJ. Calcium-activated release of nitric oxide potentiates excitatory synaptic potentials in immature rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:2600–2603. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Polosa C, Nishi S. A transient outward rectification in the cat sympathetic preganglionic neuron. Pflügers Archiv. 1987;408:207–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00581354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]