Abstract

The transient outward current (Ito) plays a prominent role in the repolarization phase of the cardiac action potential. Several K+ channel genes, including Kv1.4, are expressed in the heart, produce rapidly inactivating currents when heterologously expressed, and may be the molecular basis of Ito.

We engineered mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the K+ channel gene Kv1.4 and compared Ito in wild-type (Kv1.4+/+), heterozygous (Kv1.4+/-) and homozygous ‘knockout’ (Kv1.4−/−) mice. Kv1.4 RNA was truncated in Kv1.4−/− mice and protein expression was absent.

Adult myocytes isolated from Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− mice had large rapidly inactivating outward currents. The peak current densities at 60 mV (normalized by cellular capacitance, in pA pF−1; means ± s.e.m.) were 53.8 ± 5.3, 45.3 ± 2.2 and 44.4 ± 2.8 in cells from Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− mice, respectively (P < 0.02 for Kv1.4+/+ vs. Kv1.4−/−). The steady-state values (800 ms after the voltage clamp step) were 30.9 ± 2.9, 26.9 ± 3.8 and 23.5 ± 2.2, respectively (P < 0.02 for Kv1.4+/+ vs. Kv1.4−/−). The inactivating portion of the current was unchanged in the targeted mice.

The voltage dependence and time course of inactivation were not changed by targeted disruption of Kv1.4. The mean best-fitting V½ (membrane potential at 50 % inactivation) values for myocytes from Kv1.4 +/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− mice were -53.5 ± 3.7, -51.1 ± 2.6 and -54.2 ± 2.4 mV, respectively. The slope factors (k) were -10.1 ± 1.4, -8.8 ± 1.4 and -9.5 ± 1.2 mV, respectively. The fast time constants for development of inactivation at -30 mV were 27.8 ± 2.2, 26.2 ± 5.1 and 19.6 ± 2.1 ms in Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− myocytes, respectively. At +30 mV, they were 35.5 ± 2.6, 30.0 ± 2.1 and 28.7 ± 1.6 ms, respectively. The time constants for the rapid phase of recovery from inactivation at -80 mV were 32.5 ± 8.2, 23.3 ± 1.8 and 39.0 ± 3.7 ms, respectively.

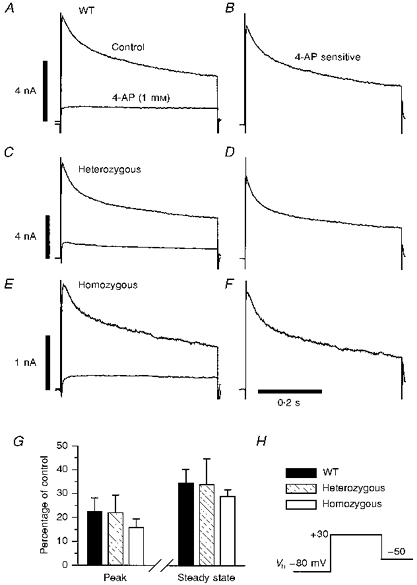

Nearly the entire inactivating component as well as more than 60 % of the steady-state outward current was eliminated by 1 mm 4-aminopyridine in Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− myocytes.

Western blot analysis of heart membrane extracts showed no significant upregulation of the Kv4 subfamily of channels in the targeted mice.

Thus, Kv1.4 is not the molecular basis of Ito in adult murine ventricular myocytes.

Transient outward or A-type K+ currents show marked inactivation, are found in brain and heart, and function to modify action potential shape (Hille, 1992). The cardiac transient outward current, Ito, is a Ca2+-independent 4-aminopyridine-sensitive current that underlies the initial phase of action potential repolarization in numerous species (Gintant, Cohen, Datyner & Kline, 1991; Campbell, Rasmusson, Comer & Strauss, 1995). Ito has been best characterized in rat cardiac myocytes (Kilborn & Feddida, 1990; Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991), is present in mouse myocytes (Benndorf & Nilius, 1988; Nuss & Marban, 1994; Zhou, Hoa, Wang, Jin, Qian & Liu, 1995; Wang & Duff, 1997), and is known to play a role in human cardiac physiology and disease (Beuckelmann, Nabauer & Erdmann, 1993; Tomaselli et al. 1994). By modulating action potential duration, Ito can have profound effects on excitation- contraction coupling, cardiac function and susceptibility to life-threatening arrhythmias.

Numerous K+ channel genes have been cloned over the last several years, several of which are expressed in the heart and produce rapidly inactivating currents (reviews: Chandy & Gutman, 1995; Deal, England & Tamkun, 1996). These include Kv1.4 (Stuhmer et al. 1989; Tseng-Crank, Tseng, Schwartz & Tanouye, 1990; Po, Snyders, Baker, Tamkun & Bennett, 1992; Wymore et al. 1994), Kv4.2 (Baldwin, Tsaur, Lopez, Jan & Jan, 1991; Roberds & Tamkun, 1991a), Kv4.3 (Dixon et al. 1996), heteromultimers of non-inactivating K+ channel subunits such as Kv1.2 or Kv1.5 with inactivating subunits such as Kv1.4 (Po, Roberds, Snyders, Tamkun & Bennett, 1993), and assembly of non-inactivating K+ channel subunits with β subunits (Morales, Castellino, Crews, Rasmusson & Strauss, 1995; England, Uebele, Shear, Kodali, Bennett & Tamkun, 1995). Identification of the molecular basis of Ito is complicated further by alternative splicing of K+ channel genes (Wymore et al. 1996; London et al. 1997), developmental changes in cardiac K+ channel gene expression (Roberds & Tamkun, 1991b; Matsubara, Suzuki & Inada, 1993; Xu et al. 1996), gradients of channel expression within the heart (Dixon & McKinnon, 1994), hormonal regulation of transcription (Takimoto & Levitan, 1994), post-translational channel modifications (Chandy & Gutman, 1995), the poor correlation between RNA and protein expression for some cardiac channels (Kv1.4; Barry, Trimmer, Merlie & Nerbonne, 1995; Xu et al. 1996), differences between animal species, and the on-going identification of novel K+ channel genes. To attempt to clarify the role of single channel genes, investigators have compared (a) detailed kinetic and pharmacological properties of Ito to those of channel genes expressed in vitro (Dixon et al. 1996), (b) transmural gradients of Ito to gradients of K+ channel gene expression (Dixon & McKinnon, 1994), and (c) developmental changes of Ito to changes of K+ channel gene expression (Xu et al. 1996). More recently, genetic manipulation of cardiac cells in vitro has been performed using antisense and dominant negative strategies (Fiset, Clark, Shimoni & Giles, 1997; Johns, Nuss & Marban, 1997). These studies suggest that Ito is primarily encoded by the Kv4 family of K+ channels.

Genetic manipulation of the mouse using gene-targeting technology (gene knockout) has been instrumental in clarifying the role of many mammalian genes, and has been used to define the roles of several K+ channel genes in the CNS and skeletal muscle (e.g. Vetter et al. 1996). This gene disruption is a novel, powerful tool for the dissection of the role of individual channel genes in cardiac electrophysiology. To investigate the possible role of a K+ channel subunit in the genesis of A-type currents in heart and brain, we engineered mice lacking a functional copy of mKv1.4, the gene coding for the murine K+ channel Kv1.4. Here we report in detail the properties of cardiac Ito in wild-type and targeted ventricular myocytes, and demonstrate that Kv1.4 is not the molecular basis of Ito in ventricular cells from the adult mouse heart.

METHODS

Cloning Kv1.4 and generation of the targeting constructs

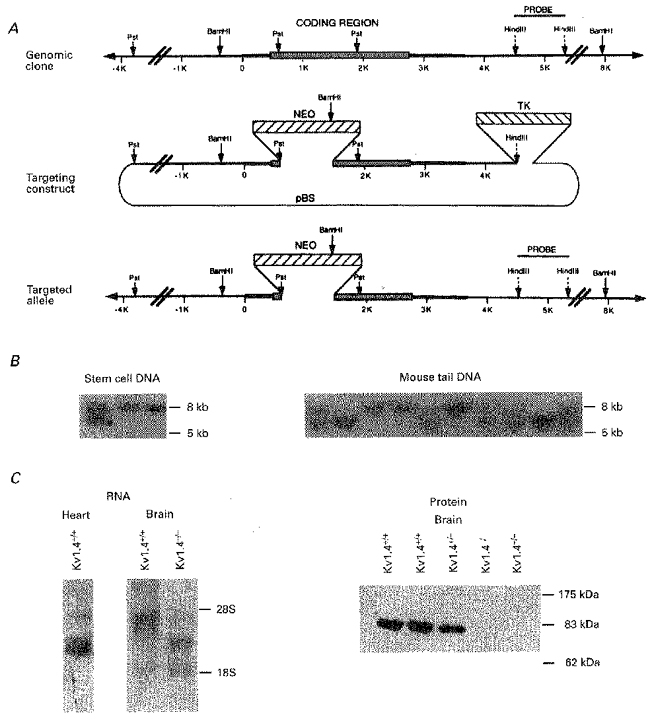

Mouse genomic DNA was isolated from J1 embryonic stem (ES) cells. Nested primers were designed based on the published rat Kv1.4 sequence (RCK4; Stuhmer et al. 1989), and DNA fragments corresponding to the 5′ end (Kv14A, nucleotides 38-1059) and the 3′ end (Kv14B, nucleotides 1472-2838) of rKv1.4 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and subcloned into pBluescript (pBS, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). These fragments were used to screen an SV129 mouse genomic library and a clone containing the mKv1.4 coding region was isolated. The 5′ arm of the targeting construct was engineered from an ∼4 kb PstI fragment of the genomic clone (which ends at 40 amino acids into coding sequence). The 3′ arm of the targeting construct was ∼5 kb and was engineered from a fragment of Kv14B (which starts after the S1 transmembrane domain at amino acid 328) ligated to a 5 kb BsteII-HindIII restriction fragment of the genomic clone. The knockout construct consisted of the 5′ arm, a neomycin resistance gene driven by the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter for positive selection, the 3′ arm, and a thymidine kinase cassette driven by the PGK promoter for negative selection (Fig. 1A). The targeting vector was constructed such that the remaining channel fragment would not have the N-terminal multimerization domain described in the Shaker family of channels, minimizing the possibility that it would have a dominant negative effect (Li, Jan & Jan, 1992).

Figure 1. Targeted disruption of mKv1.4.

A, schematic representation and partial restriction map of the genomic clone of mouse Kv1.4, the targeting construct, and the targeted allele. NEO stands for the neomycin resistance cassette used for positive selection with G418, and TK stands for the thymidine kinase cassette used for negative selection with FIAU. B, genomic Southern blots using BamHI-digested DNA isolated from neomycin- and FIAU-resistant ES cell lines (left) and from tails from offspring of two targeted heterozygous mice (right). The probe is the 1.5 kb HindIII restriction fragment identified in A that lies within the BamHI restriction fragment that contains the Kv1.4 coding region but outside of the targeting construct. Note that the wild-type allele is 8 kb and the targeted allele is reduced to 5 kb as a result of a BamHI site introduced by the targeting construct. C, Northern blot (left) and Western blot (right) from wild-type (Kv1.4+/+) and targeted (Kv1.4+/−, Kv1.4−/−) mice. The Northern blots were loaded with either 5 μg of poly-A+ ventricular RNA or 25 μg of total brain RNA per lane and were probed with the 1 kb fragment Kv14A from the 5′ end of the Kv1.4 cDNA clone. The Western blot was loaded with 100 μg of brain membrane protein extract per lane and was incubated with the N-terminal Kv1.4 antibody KV14N at a dilution of 1 : 400.

ES cell electroporation and blastocyst injection to generate targeted mice

ES cells of the J1 line were expanded on neomycin-resistant embryonic ‘feeder’ fibroblasts in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media supplemented with non-essential amino acids, 15 % fetal calf serum, and leucocyte inhibitory factor (LIF, 1000 units ml−1, Gibco). The targeting construct was then electroporated into 40 million cells, the cells replated on neomycin-resistant fibroblasts, and treated with G418 (Geneticin, Gibco; 200 μg ml−1) starting 24 h after electroporation and with FIAU (fialuridine (1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-β-D-arabinofuranosyl)-5-iodouracil), Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA; 0.2 μm) starting 48 h after electroporation. Double selection was continued for 7-8 days. At that point, surviving doubly resistant clones were picked, expanded in 24-well plates in the presence of G418, and frozen at -80°C. An aliquot of each clone was replated, grown for DNA analysis in 12-well plates without LIF, and used to isolate genomic DNA. Clones heterozygous for homologous recombination were determined by the hybridization pattern on a genomic Southern blot of ES genomic DNA digested with BamHI and probed with a radiolabelled fragment (T7 Quickprime, Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) of the mKv1.4 genomic clone that was inside the BamHI restriction fragment but outside the targeting construct. Genomic Southern blots were performed with 10-15 μg of genomic DNA on nylon membrane at high stringency.

Blastocyst injection was performed at the core knockout facility of the Massachusetts General Hospital and in the Department of Cardiology, Children's Hospital, both in Boston, MA, USA. ES cells heterozygous for the targeted allele were expanded, trypsinized, and injected into blastocysts from C57BL/6 mice. The blastocyts were reimplanted into foster mothers and yielded chimeric mice. The J1 ES cell line is dominant homozygous for agouti colour. Highly chimeric males were mated with C57BL/6 females, and germ line transmission of the ES cell line was determined by the colour of the offspring. Agouti offspring were genotyped by Southern blot analysis of tail DNA. Heterozygotes were mated with each other to give homozygotes lacking a functional copy of Kv1.4.

After anaesthesia with methoxyflurane (Metofane) mice were killed by cervical dislocation, with the exception of those used for cellular electrophysiology (see below). All animal experiments were performed under approved animal protocols at Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA and Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA.

Northern blot and Western blot of heart and brain

For Northern blots, either 5 μg of poly-A+ RNA (polyATract, Promega) or 25 μg of whole RNA (RNEasy, Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA) was run on a formaldehyde gel, transferred to a nylon membrane by capillary action, stained with Methylene Blue, and probed with a radiolabelled fragment from the 5′ untranslated and coding region of mKv1.4 (KV14A) at high stringency.

Immunoblotting was performed as described by Takimoto & Levitan (1994). Membranes from heart (atria dissected away) and brain were isolated by homogenization of organs in a solution containing sucrose (250 mm for heart, 300 mm for brain), phenylmethylsulphonic fluoride (PMSF; 1 mm), and iodoacetamide (1 mm). The homogenate was spun at 1000 g to pellet insoluble material, and the supernatant spun at 100 000 g to pellet the membrane fraction. The pellet was washed in a solution containing Tris (20 mm, pH 7.4), EDTA (1 mm), PMSF (1 mm), and iodoacetamide (1 mm), solubilized in the same solution with 1 % SDS, run on an 8 % polyacrylamide gel, transferred to PVDF membrane (MSI, Westboro, MA, USA) using a semidry transfer apparatus, blocked with PBS-5 % milk for at least 2 h, and incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The blots were then washed with PBS-0.15 % Tween, incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody, washed, and detected using a chemiluminescence system (NEN).

Antibodies for Kv1.4 were supplied by Dr Morgan Sheng (Sheng, Tsaur, Jan & Jan, 1992; KV14N) and were used at a dilution of 1: 500. Antibodies for Kv4.2 (directed against an epitope common to both Kv4.2 and Kv4.3) were a gift of Dr Jeanne Nerbonne and were used at a dilution of 1: 250.

Isolation of adult mouse cardiac myocytes

Single ventricular myocytes from adult wild-type and targeted adult mice were isolated using a modified Langendorff procedure (Wang, Feng, Kondo, Sheldon & Duff, 1996). Briefly, mice were killed by cervical dislocation followed by excision of the heart. The hearts were initially washed free of blood with Tyrode solution containing (mm): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.16 NaH2PO4, 3 NaHCO3, 5 Hepes and 5.5 glucose (pH 7.4). This washing was followed by a perfusion with a nominally Ca2+-free Tyrode solution. The perfusion was then recirculated with the enzymes at concentrations of 200 U ml−1 collagenase (Type 2, Worthington) and 0.5 U ml−1 protease (Type IV, Sigma). The hearts were then washed out with a recovery solution of the following composition (mm): 5 KCl, 70 glutamic acid, 20 taurine, 10 oxalic acid, 5 KH2PO4, 5 Hepes, 11 glucose and 0.5 EGTA (pH 7.4 with KOH). The procedures were carried out at 35 ± 0.5°C. Each solution was saturated with 100 % O2 during perfusion. The resultant ventricular myocytes were Ca2+ tolerant and had a typical rod-shaped appearance with clear cross-striations.

Electrophysiological studies were performed on cells from homozygous targeted mice and heterozygous littermates. Cells from C57BL/6 mice were used as wild-type controls.

Whole-cell voltage clamp of myocytes

Standard methods for whole-cell patch clamp recording were used as described previously (Snyders, Tamkun & Bennett, 1993). Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass. Data acquisition and command potentials were controlled by pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). To minimize voltage errors due to series resistance, patch electrode resistance was kept as low as tolerated by the preparation (< 1-2 MΩ), and cells expressing excessively large currents were rejected (ideally < 5 nA). Voltage control was further improved with capacitance and series resistance compensation. For all cells the capacitive transients elicited by small depolarizations (before any compensation) were recorded to yield the capacitive surface area and the access resistance. The pipette solution (intracellular) was (mm): 110 KCl, 10 Hepes, 5 K4-BAPTA, 2 K2-ATP, 2 MgCl2; pH 7.2 (KOH). The extracellular solution comprised (mm): 145 NaCl, 10 Hepes, 10 glucose, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2; pH 7.35 (NaOH).

Voltage clamp protocols

The pulse protocols used to characterize the gating properties (activation, inactivation and kinetics), and drug-channel interaction (block induction, recovery) were similar to the ones used previously (Snyders et al. 1993). The interval between pulses in these protocols was adjusted based on channel and block recovery kinetics to ensure identical initial conditions.

Voltage dependence of activation and inactivation

The membrane potential dependence of channel opening was determined using a single voltage clamp protocol. The cell was held at a negative potential (-80 mV), depolarized to a test potential of +60 mV for 500 ms, and then returned to -80 mV. Subsequent test potentials were decremented by 10 mV. The time course of inactivation was estimated by non-linear least squares fitting of an exponential function as described below.

Steady-state voltage dependence of inactivation

The membrane potential was held at -80 mV and a 250 ms prepulse to between -100 and 0 mV (in 10 mV intervals) was applied, followed by depolarization to +20 mV. The current at each prepulse was normalized to the current with a prepulse of -100 mV.

Recovery from inactivation

The time dependence of the recovery from inactivation was measured using a twin-pulse protocol. Cells were depolarized to +40 mV for 300 ms followed by repolarization to -80 mV for a variable period. This was followed by a test pulse to +40 mV to determine the fraction of channels not inactivated. The peak K+ current during the test pulse was plotted as a function of the duration of the recovery interval.

Data analysis

The voltage dependence of steady-state activation or inactivation was fitted with the equation:

where Imax is the maximum observed current, V is membrane potential, V½ is the membrane potential for 50 % activation (inactivation), z is the equivalent electrical charge that must traverse the entire electrical field to give the observed voltage dependence, and where F, R and T have their usual thermodynamic meanings. In practice a slope factor, k, equal to RT/zF, was determined in the fit and this value is reported.

The time courses of the falling phase of the macroscopic K+ current (‘apparent inactivation’), as well as onset of recovery from inactivation were characterized by fitting the data with an exponential function of the form:

where An is the amplitude of the nth component and A is the steady-state level; τn is the time constant of the nth component. Curve fitting was based on a non-linear least squares algorithm. The results were displayed in linear and semilogarithmic formats together with a plot of the residuals. The best-fitting function was determined by visual inspection and by calculation of a χ2 statistic. The χ2 function decreased with increasing numbers of parameters until it plateaued. An F ratio test was applied to determine whether the increase in parameters was justified. Results of multiple experiments were expressed as means and standard error of the mean (mean ±s.e.m.). Differences between means of two samples were tested using grouped Student's t tests when appropriate. Statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Phenotype of targeted mice lacking Kv1.4

Figure 1A shows a partial restriction map of the Kv1.4 gene and the targeting construct that was electroporated into the ES cells. Of the ninety-two neomycin- and FIAU-resistant clones isolated and genotyped, nine were heterozygous for the targeted allele (Fig. 1B). Two of these heterozygous ES cell lines (K4-52, K4-27) were injected into blastocysts to yield chimeric mice. Mating of the chimeras with C57BL/6 control mice yielded agouti offspring indicating germ line transmission, and genomic Southern blot analysis of the F1 offspring indicated that ∼50 % carried the targeted allele. Mating of male and female mice heterozygous for the targeted allele yielded F2 mice in approximately the expected Mendelian ratios: 11/61 (18 %) wild-type (Kv1.4+/+), 35/61 (57 %) heterozygous (Kv1.4+/−) and 15/61 (25 %) homozygous targeted (Kv1.4−/−) for the K4-52 line and 2/20 (10 %) Kv1.4+/+, 11/20 (55 %) Kv1.4+/− and 7/20 (35 %) Kv1.4−/− for the K2-27 line (Fig. 1B). Except as indicated, subsequent experiments were carried out using the F2 mice of mixed (50 % SV129, 50 % C57BL/6) background from the K4-52 line.

Several distinct transcipts of Kv1.4 RNA were expressed in the hearts and brains of wild-type mice, as previously described in detail by Wymore et al. (1996). The predominant Kv1.4 mRNA transcript seen in Northern blots of RNA from the brains of Kv1.4+/+ mice was truncated in the Kv1.4−/− mice, and the abundant 85 kDa Kv1.4 protein band seen in Western blots of crude brain membrane fractions was absent in the Kv1.4−/− mice (n= 5; Fig. 1C). Very low levels of Kv1.4 protein were occasionally detected in membrane fractions from Kv1.4+/+ and Kv1.4+/− mouse hearts using the same antibody (data not shown) but not in Kv1.4−/− hearts (n= 6). The antibody did detect an abundant 65 kDa band in the cardiac membrane preparation that did not differ between wild-type and targeted mice and might represent another channel that cross-reacts with the Kv14N antibody. The near absence of Kv1.4 protein in the wild-type mouse heart despite abundant RNA expression is similar to findings previously reported in the rat (Barry et al. 1995).

The Kv1.4−/− mice were fertile and were bred to maintain the line. They appeared grossly normal although spontaneous seizure activity was occasionally observed (< 10 % of mice). No histological abnormalities were noted in the heart, and high-resolution electrocardiograms did not demonstrate prolongation of the PR or QT intervals (data not shown).

Outward K+ currents in wild-type and targeted mice

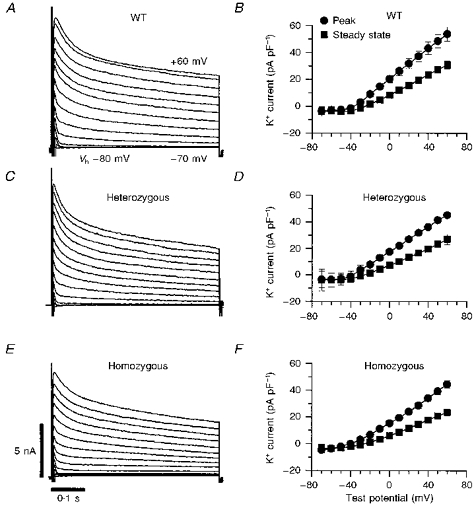

Figure 2A, C and E illustrates representative K+ currents recorded from single myocytes enzymatically isolated from the ventricles of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mice. The patch electrode and bath solutions were designed to mimic physiological conditions as closely as possible within the constraints of the whole-cell voltage clamp method that was used. Superimposed current recordings for steps from a holding potential of -80 mV to membrane potentials ranging from -70 to +60 mV (in 10 mV increments) are shown. Following the initial surge of current charging membrane capacitance, there is activation followed by rapid inactivation of an outward current similar to the K+ current Ito reported in other neonatal and adult cardiac myocytes (see, e.g., Campbell et al. 1995).

Figure 2. Voltage-dependent outward currents in mouse ventricular myocytes.

A, C and E, original recordings of outward currents from voltage-clamped single myocytes isolated from Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− mice, respectively. Outward currents were elicited by a series of 500 ms step depolarizations from a holding potential (Vh) of -80 mV to potentials between -70 and +60 mV in 10 mV increments. B, D and F, peak outward and steady-state current-voltage relationships for Kv1.4+/+ (n= 10), Kv1.4+/− (n= 5) and Kv1.4−/− (n= 12) myocytes, respectively, shown as means ±s.e.m. Peak outward current was measured as the maximum outward current within the initial few milliseconds of a depolarization after the capacity transient. The ionic current was then normalized to cell capacitance to control for cell surface area. The amplitude of the steady-state current was determined at the end of each voltage pulse.

Figure 2B, D and F shows the peak and steady-state current density as a function of depolarization voltage in cells isolated from Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− mice. Steady-state current was measured at the end of the 800 ms voltage clamp step. On average, the peak current density at 60 mV (normalized by cellular capacitance, in pA pF−1) was 53.8 ± 5.3 in cells from Kv1.4+/+ mice, 45.3 ± 2.2 in cells from Kv1.4+/− mice and 44.4 ± 2.8 in cells from Kv1.4−/− mice (P < 0.02 for Kv1.4+/+ vs. Kv1.4−/−). Similarly, the steady-state values were 30.9 ± 2.9 in cells from Kv1.4+/+ mice, 26.9 ± 3.8 in cells from Kv1.4+/− mice and 23.5 ± 2.2 in cells from Kv1.4−/− mice (P < 0.02 for Kv1.4+/+ vs. Kv1.4−/−). Thus, there was a small decrease in a sustained outward current in cells from Kv1.4−/− mice that was statistically significant when compared with wild-type Kv1.4+/+ controls but not when compared with Kv1.4+/− littermates. The decaying portion of the currents, Ito, did not differ significantly between wild-type and targeted mice, however.

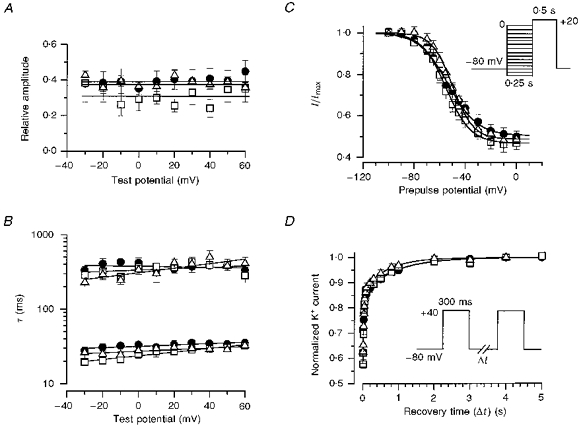

Inactivation properties of Ito

We next characterized the inactivation phase of the transient outward current. The time course of the decay phase of Ito was best fitted with a sum of two exponentials plus a baseline. The relative amplitude of the fast component (Afast) and the time constants (τ1 and τ2) obtained from this analysis as a function of depolarizing potential are shown in Fig. 3A and B. The fast time constant was in the range 20-30 ms, and the slow time constant was in the range 200-400 ms. These time constants showed little membrane potential dependence and we were unable to identify any statistically significant difference between wild-type and targeted mice.

Figure 3. Inactivation properties of Ito in myocytes from wild-type (•), heterozygous (▴) and homozygous (□) targeted mice.

A and B, voltage dependence of inactivation of Ito. The decay of each record of Ito from each myocyte was fitted with a sum of two exponential components (see Methods). A shows the relative amplitudes of the fast component (Afast) of Ito as a function of membrane potential, while B shows the fast and slow time constants of the decay phase of current for cells from Kv1.4+/+ (n= 10), Kv1.4+/− (n= 5) and Kv1.4−/− (n= 12) mice. C, voltage dependence of Ito channel availability (steady-state inactivation). Voltage dependence of inactivation was assessed using a double-pulse protocol from a holding potential of -80 mV, with a 250 ms prepulse to voltages between -100 and 0 mV (displayed on the abscissa), followed by a 500 ms test pulse to +20 mV to assay the available Ito current. This was normalized to the current measured using a prepulse of -100 mV. The continuous curves represent non-linear least-squares fits of the Boltzmann equation (see Methods). The analysis was applied in each experiment, giving mean values. Note that the total peak outward current includes a steady-state component which may not represent Ito. D, time course of recovery from inactivation, with normalized currents shown as a function of repolarization time. The holding potential was -80 mV; a prepulse of 300 ms to +40 mV was applied, the membrane potential was changed back to -80 mV for the period of time indicated on the abscissa, and a test pulse to +40 mV was applied to access the fractional recovery of current after inactivation during the prepulse. Each current was normalized by the maximum current at +40 mV obtained after a 10 s interval at -80 mV, and was fitted with a double-exponential function (see Methods). The best fit parameters (τ1, τ2) were obtained from the averaged data (see text). All current recovered in all three types of mice within 4 s.

We then analysed the steady-state voltage dependence of inactivation using 250 ms prepulses in a standard twin-pulse protocol (Fig. 3C). This prepulse duration was chosen because preliminary experiments indicated that it was sufficiently long to induce nearly full inactivation of Ito, but was not so long as to induce the slow inactivation seen with other outward K+ currents (also see, e.g., Gintant et al. 1991). These data were fitted with the Boltzmann equation to obtain the membrane potential at which 50 % of the inactivatable channels had inactivated (V½) and the slope factor (k) of the relationship. Under these conditions, maximal inactivation occurred at potentials above -20 to 0 mV and the residual steady-state current was approximately 50 % of the peak current level. The average best-fitting V½ for myocytes from Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− mice was -53.5 ± 3.7 mV (n= 7), -51.1 ± 2.6 mV (n= 5) and -54.2 ± 2.4 mV (n= 10), respectively. The slope factors (k) were -10.1 ± 1.4 mV, -8.8 ± 1.4 mV and -9.5 ± 1.2 mV, respectively. These values were not statistically different from each other (P > 0.1).

In addition, we analysed the recovery of inactivation using a twin-pulse protocol. Cells were voltage clamped to -80 mV, stepped to +40 mV for 300 ms to inactivate the channels, and then stepped back to -80 mV for variable durations. This was followed by a test pulse to assess the amplitude of outward K+ current which was normalized to the peak outward K+ current obtained after a 5 s pulse interval. The time courses obtained in this way are shown in Fig. 3D Each set of data was also fitted by a biexponential function which gave two time constants of recovery from inactivation. The continuous lines in Fig. 3D indicate the best-fitting function for each data set. The time constants for the rapid phase of recovery from inactivation at -80 mV (τ1) for myocytes from Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− and Kv1.4−/− mice were 32.5 ± 8.2, 23.3 ± 1.8 and 39.0 ± 3.7 ms, respectively, while the time constants for the slow phase of recovery (τ2) were 1023.5 ± 67.0, 709.6 ± 156.8 and 946.9 ± 181.1 ms, respectively. Note that the initial part of the curve (the earliest time point) begins with a fractional current of approximately 0.55. These kinetic parameters were not statistically significantly different from one another.

Block of Ito by 4-aminopyridine

Figure 4 shows the effect of 4-AP on outward currents in ventricular myocytes. A concentration of 1 mm 4-AP eliminated almost the entire inactivating component of the outward current, as well as approximately 60 % of the steady-state current (Fig. 4A-F). There were no statistically significant differences in the residual currents between cells from Kv1.4+/+, Kv1.4+/− or Kv1.4−/− mice (Fig. 4G).

Figure 4. Effects of 4-aminopyridine on Ito.

A (Kv1.4+/+, n= 5), C (Kv1.4+/−, n= 6) and E (Kv1.4−/−, n= 6) show the currents of control and targeted mice in the absence and presence of 1 mm 4-AP during steps to a test potential of +30 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV. B, D and F are the 4-AP-sensitive currents for the representative mouse of each genotype. G shows the summarized data of 4-AP block for peak and steady-state currents. The voltage protocol is shown in H.

Effect of Kv1.4 knockout on other A-type potassium channels

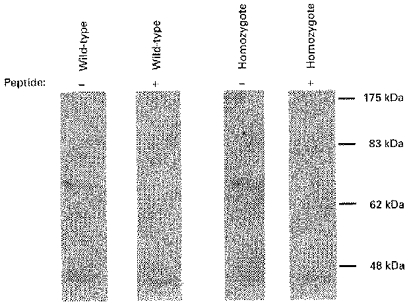

Targeted disruption of Kv1.4 could lead to upregulation of another channel with similar electrophysiological characteristics, thus compensating electrophysiologically for the loss of Kv1.4. Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 are candidates for Ito and are expressed at the RNA level in the mouse heart (data not shown). We therefore examined the level of Kv4 channel proteins in the hearts of wild-type and targeted mice using an antibody to an epitope common to both Kv4.2 and Kv4.3. We identified an ∼72 kDa band in the heart that was similar to data published in rat heart (Barry et al. 1995) and was competed with by the peptide against which the antibody was raised (Fig. 5). The amount of channel protein detected did not appear to vary significantly between Kv1.4+/+ and Kv1.4−/− mice. Thus, we found no evidence that targeted disruption of Kv1.4 resulted in the upregulation of Kv4.2 or Kv4.3 in the heart.

Figure 5. Kv4 channel protein in wild-type and Kv1.4-targeted mice.

Western blot loaded with 90 μg of a membrane protein extract from hearts of representative wild-type and homozygous targeted mice. Duplicate blots were incubated with a 1: 250 dilution of an antibody designed to rat Kv4.2 (but which also recognized Kv4.3) and with the same antibody preincubated with 10 μg of the peptide against which the antibody was raised. Similar results were obtained using protein extracts from other Kv1.4+/+ and Kv1.4−/− mice (n= 3).

DISCUSSION

Ito in myocytes from wild-type mice

We have described the properties of Ito in cells isolated from the ventricle of the mouse, an animal with an extremely short cardiac action potential. Detailed descriptions of the properties of Ito in the adult mouse ventricular myocyte are critical due to the increasing use of genetic manipulation in the study of the electrophysiological properties of the heart. Our data show that the 4-AP-sensitive Ito is a major outward current during the action potential in these cells and should play a key role in repolarization of the heart. Descriptions of the properties of Ito have previously been reported for neonatal mouse myocytes (Nuss & Marban, 1994) and for ventricular myocytes isolated from mice of various ages (Benndorf & Nilius, 1988; Zhou et al. 1995; Wang & Duff, 1997). Wang & Duff (1997) reported a V½ for inactivation that was ∼20 mV more positive than we report in the present study, and their time constants for inactivation and recovery from inactivation were substantially longer. These differences may reflect details of the experimental protocols or the different strains of mice used in the two studies (CD-1 mice in their study vs. SV129 and C57BL/6 in the present study), and emphasize the importance of littermate control groups in studies of this type.

Kv1.4 is not the molecular basis of Ito in isolated adult mouse ventricular myocytes

Kv1.4 subunits produce a rapidly inactivating 4-AP-sensitive K+ current when expressed in Xenopus oocytes or mammalian cell lines (Stuhmer et al. 1989; Tseng-Crank et al. 1990; Po et al. 1992; Wymore et al. 1994), and Kv1.4 RNA is expressed in moderate abundance in the hearts of many species (Roberds & Tamkun, 1991a; Matsubara et al. 1993; Dixon & McKinnon, 1994). Kv1.4 was therefore the first candidate for the molecular basis of Ito, either alone or as a component of a heterotetramer (Po et al. 1993). The kinetic and pharmacological properties of Kv1.4 and Ito do not perfectly match, however, and Kv1.4 protein has been shown to be quite rare in rat ventricular myocardium (Barry et al. 1995; Xu et al. 1996).

Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 are also rapidly inactivating potassium channels expressed in the heart. Kv4.3 RNA is abundant in rat, dog and human heart, while Kv4.2 is abundant in rat heart and not detected in dog or human heart (Baldwin et al. 1991; Roberds & Tamkun, 1991a; Dixon & McKinnon, 1994; Dixon et al. 1996). Previous studies have shown that the kinetic and pharmacological properties of Kv4.3 (and Kv4.2 in the rat) closely resemble Ito (Dixon et al. 1996). In addition, a gradient of expression of Kv4.2 mRNA across the rat cardiac wall correlates to the decrease in Ito seen from epicardium to endocardium in several species. Recently, direct manipulations of channel expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro have supported a role for Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 in the aetiology of Ito. Fiset et al. (1997) showed a decrease in Ito in cells treated with antisense oligonucleotides directed against Kv4.2 and Kv4.3. Similarly, a dominant negative fragment of Kv4.2 transfected into cardiac cells using an adenoviral vector decreases Ito (Johns et al. 1997). These studies strongly support a role for the Kv4 family in the genesis of Ito, but are limited by uncertainty in the extent of removal of the target protein and a potential lack of specificity. In addition, they do not exclude a role for Kv1.4 as a component of Ito.

We have compared Ito in wild-type mice to Ito in mice genetically engineered to completely lack a functional copy of the gene Kv1.4 and tested the hypothesis that the Kv1.4 gene product plays a major role in producing the channels responsible for Itoin vivo. We found that the electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of the transient outward current in knockout mice are essentially identical to those in wild-type mice. Changes in Ito following deletion of the Kv1.4 gene product could be masked by upregulation of another potassium channel gene. Electrophysiological and pharmacological data make Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 likely candidates for Ito in the heart, and RNA from Kv4.2 and Kv4.3is present in the mouse heart. We found that the protein level of the detected channel appeared to be similar in wild-type and homozygous mice, however, and this suggests that expression of these channels was not perturbed. We cannot absolutely exclude altered regulation of a known or unknown channel in the Kv1.4-targeted mice. The remarkable kinetic and pharmacological similarities of Ito in wild-type and homozygous knockout mice make this possibility extremely unlikely. Thus, our results show that Kv1.4 does not play a major role in the genesis of Ito in most adult mouse ventricular myocytes.

A 4-AP-sensitive sustained outward current is decreased in myocytes from homozygous targeted mice

Mouse ventricular myocytes have a sustained component to the outward potassium current that is 4-AP sensitive (Fig. 4). Although similar currents have not been described in rat or human ventricular myocytes, 4-AP-sensitive sustained currents with varying pharmacological properties have been described in atrial myocytes isolated from several species including human and named IKur (Chandy & Gutman, 1995; Li, Feng, Yue, Carrier & Nattel, 1996). The sustained outward current described in this study may play an important role in the repolarization of the mouse ventricle, which has an extremely rapid rate and a short action potential. The small but statistically significant decrease that we found in this sustained current in the Kv1.4−/− mice compared with the Kv1.4+/+ mice could reflect the minor species difference between the Kv1.4−/− (50 % SV129, 50 % C57BL/6), Kv1.4+/− (50 % SV129, 50 % C57BL/6) and Kv1.4+/+ (C57BL/6) mice, a secondary effect on the heart or its channels resulting from the loss of Kv1.4 in another organ such as the brain, or a small direct effect from participation of Kv1.4 subunits in this cardiac current.

Limitations

Our findings may not generalize to all conditions. Our experiments sampled only a subpopulation of cells isolated from the mouse ventricle and we cannot rule out the possibility that Kv1.4 is important in a small fraction of ventricular cells. Similarly, expression of channel genes is known to vary during development and Kv1.4 may play a more important role earlier in the fetal or neonatal heart. We did not study cells isolated from the atrium. In addition, our results may not be applicable to other species, particularly larger mammals with markedly slower heart rates.

Conclusions

Ito is a prominent inactivating current involved in the repolarization of mouse myocytes, and a number of K+ channel gene products have been suggested as its molecular basis. Kv1.4 RNA is abundantly expressed in the heart, and Kv1.4 tetramers produce a rapidly inactivating current in vitro. We have used gene targeting to engineer mice lacking Kv1.4 and demonstrated that Ito is unchanged. Thus, Kv1.4 does not contribute significantly to Ito in the majority of mouse ventricular myocytes.

The studies described here provide a template for future investigations of the molecular basis of specific cardiac currents using gene targeting. This type of work may ultimately elucidate the molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmias. In addition, Kv1.4 may contribute to repolarization in the brain, peripheral nervous system, and other organs. Future studies using the Kv1.4-targeted mice, other genetically engineered mice, and animals crossbred to carry multiple channel mutations will explore these possibilities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sandra Schieferl, Brady Palmer, Kimberly P. Newton, Anita K. Beyer and Christopher M. Lewarchik for their technical assistance; Jeanne M. Nerbonne and Morgan Sheng for supplying the K+ channel antibodies; and Mark C. Fishman for his assistance with the studies and for his comments on the manuscript. This study was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, USA) grants HL-02843 (B. L.), HL-51197 (P. B. B.) and HL-46681 (P. B. B.), by a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (B. L.) and by funding from the Procter and Gamble Corporation (J. A. H.).

References

- Apkon M, Nerbonne JM. Characterization of two distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:973–1011. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.5.973. 10.1085/jgp.97.5.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin TJ, Tsaur M-L, Lopez GA, Jan YN, Jan LY. Characterization of a mammalian cDNA for an inactivating voltage-sensitive K+ channel. Neuron. 1991;7:471–483. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90299-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Trimmer JS, Merlie JP, Nerbonne JM. Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ channel subunits in adult rat heart. Relation to functional K+ channels. Circulation Research. 1995;77:361–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benndorf K, Nilius B. Properties of an early outward current in single cells of the mouse ventricle. General Physiology and Biophysics. 1988;7:449–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Alterations of K+ currents in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation Research. 1993;73:379–385. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Comer MB, Strauss HC. The cardiac calcium-independent transient outward potassium current: kinetics, molecular properties and role in ventricular repolarization. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 2. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 1995. pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chandy KG, Gutman GA. Voltage-gated K+ channel genes. In: North RA, editor. Handbook of Receptors and Channels: Ligand- and Voltage-gated Ion Channels. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Deal KK, England SK, Tamkun MM. Molecular physiology of cardiac potassium channels. Physiological Reviews. 1996;76:49–67. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JE, McKinnon D. Quantitative analysis of potassium channel mRNA expression in atrial and ventricular muscle of rats. Circulation Research. 1994;75:252–260. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JE, Shi W, Wang H-S, McDonald C, Yu H, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, McKinnon D. Role of the Kv4.3 K+ channel in ventricular muscle. A molecular correlate for the transient outward current. Circulation Research. 1996;79:659–668. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England SK, Uebele VN, Shear H, Kodali JV, Bennett PB, Tamkun MM. Characterization of a novel K+ channel beta subunit expressed in human heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:6309–6313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiset C, Clark RB, Shimoni Y, Giles WR. Shal-type channels contribute to the Ca2+-independent transient outward K+ current in rat ventricle. Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:51–64. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gintant GA, Cohen IS, Datyner NB, Kline RP. Time-dependent outward currents in the heart. In: Fozzard HA, Jinnengs RB, Haber E, Katz AM, Morgan HE, editors. The Heart and Cardiovascular System. 2. New York: Raven Press Publishers; 1991. pp. 1121–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1992. pp. 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Johns DC, Nuss HB, Marban E. Suppression of neuronal and cardiac transient outward currents by viral gene transfer of a dominant negative Kv4.2 construct. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:A349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilborn MJ, Fedida D. A study of the developmental changes in outward currents of rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:37–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G-R, Feng J, Yue L, Carrier M, Nattel S. Evidence for two components of delayed rectifier K+ current in human ventricular myocytes. Circulation Research. 1996;78:689–696. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Jan Y, Jan L. Specification of subunit assembly by the hydrophilic amino-terminal domain of the Shaker potassium channel. Science. 1992;257:1225–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1519059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Trudeau MC, Newton KP, Beyer AK, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Satler CA, Robertson GA. Two isoforms of the mouse ether-a-go-go-related gene coassemble to form channels with properties similar to the rapidly activating component of the cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Circulation Research. 1997;81:870–878. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara H, Suzuki J, Inada M. Shaker-related potassium channel, Kv1.4, mRNA regulation in cultured rat heart myocytes and differential expression of Kv1.4 and Kv1.5 genes in myocardial development and hypertrophy. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;92:1659–1666. doi: 10.1172/JCI116751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales MJ, Castellino RC, Crews AL, Rasmusson RL, Strauss HC. A novel β subunit increases rate of inactivation of specific voltage-gated potassium channel α subunits. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:6272–6277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss HB, Marban E. Electrophysiological properties of neonatal mouse cardiac myocytes in primary culture. Journal of Physiology. 1994;479:265–279. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Po S, Roberds S, Snyders DJ, Tamkun MM, Bennett PB. Heteromultimeric assembly of human potassium channels. Molecular basis of a transient outward current. Circulation Research. 1993;72:1326–1336. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Po S, Snyders DJ, Baker R, Tamkun MM, Bennett PB. Functional expression of an inactivating potassium channel cloned from human heart. Circulation Research. 1992;71:732–736. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberds SL, Tamkun MM. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of five voltage-gated potassium channel cDNAs expressed in rat heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991a;88:1798–1802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberds SL, Tamkun MM. Developmental expression of cloned cardiac potassium channels. FEBS Letters. 1991b;284:152–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80673-q. 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80673-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Tsaur M-L, Jan YN, Jan LY. Subcellular segregation of two A-type K+ channel proteins in rat central neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90166-b. 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90166-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyders DJ, Tamkun MM, Bennett PB. A rapidly activating and slowly inactivating potassium channel cloned from human heart: Functional analysis after stable tissue culture expression. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;101:513–543. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.4.513. 10.1085/jgp.101.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhmer W, Ruppersberg JP, Schroter KH, Sakmann B, Stocker M, Giese KP, Perschke A, Baumann A, Pongs O. Molecular basis of functional diversity of voltage-gated potassium channels in mammalian brain. EMBO Journal. 1989;8:3235–3244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto K, Levitan ES. Glucocorticoid induction of Kv1.5 K+ channel gene expression in ventricle of rat heart. Circulation Research. 1994;75:1006–1013. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.6.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Beukelmann DJ, Calkins HG, Berger RD, Kessler PD, Lawrence JH, Kass D, Feldman AM, Marban E. Sudden cardiac death in heart failure. The role of abnormal repolarization. Circulation. 1994;90:2534–2539. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng-Crank JC, Tseng G-N, Schwartz A, Tanouye MA. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a potassium channel cDNA isolated from a rat cardiac library. FEBS Letters. 1990;268:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80973-m. 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80973-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter DE, Mann JR, Wangemann P, Liu J, McLaughlin KF, Lesage F, Marcus DC, Lazdunski M, Heinemann SF, Barhanin J. Inner ear defects induced by null mutation of the Isk gene. Neuron. 1996;17:1251–1264. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80255-x. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80255-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Duff HJ. Developmental changes in transient outward current in mouse ventricle. Circulation Research. 1997;81:120–127. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Feng Z-P, Kondo CS, Sheldon ES, Duff HJ. Developmental changes in the delayed rectifier K+ channels in mouse heart. Circulation Research. 1996;79:79–85. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymore RS, Korenberg JR, Kinoshita KD, Aiyar J, Coyne C, Chen X-N, Hustad CM, Copeland NG, Gutman GA, Jenkins NA, Chandy KG. Genomic organization, nucleotide sequence, biophysical properties, and localization of the voltage-gated K+ channel gene KCNA4/Kv1.4 to mouse chromosome 2/human 11p14 and mapping of KCNC1/ Kv3.1 to mouse 7/human 11p14.3-p15.2 and KCNA1/Kv1.1 to human 12p13. Genomics. 1994;20:191–202. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1153. 10.1006/geno.1994.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymore RS, Negulescu D, Kinoshita K, Kalman K, Aiyar J, Gutman GA, Chandy KG. Characterization of the transcriptional unit of mouse Kv1.4, a voltage-gated potassium channel gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:15629–15634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15629. 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Dixon JE, Barry DM, Trimmer JS, Merlie JP, McKinnon D, Nerbonne JM. Developmental analysis reveals mismatches in the expression of K+ channel α subunits and voltage-gated K+ channel currents in rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:405–419. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.5.405. 10.1085/jgp.108.5.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Hoa XM, Wang ZM, Jin MW, Qian JQ, Liu TF. Characterization of outward current in mouse ventricular myocytes. Sheng Li Hsueg Pao - Acta Physiologica Sinica. 1995;47:535–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]