Abstract

We have examined the mechanisms by which cultured central neurones from embryonic rat brain buffer intracellular Ca2+ loads following kainate receptor activation using fluorescent indicators of [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i.

Stimulation of cultured forebrain neurones with 100 μm kainate produced a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i that displayed a variable rate of recovery. Kainate also increased [Na+]i with a response that was slightly slower in onset and markedly slower in recovery.

The recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline was not very sensitive to the [Na+]i. The magnitude of the increase in [Na+]i in response to kainate did not correlate well with the [Ca2+]i recovery time, and experimental manipulations that altered [Na+]i did not have a large impact on the rate of recovery of [Ca2+]i.

The recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline was accelerated by the mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange inhibitor CGP-37157, suggesting that the recovery rate is influenced by release of Ca2+ from a mitochondrial pool and also that variation in the recovery rate is related to the extent of mitochondrial Ca2+ loading. Kainate did not alter the mitochondrial membrane potential.

These studies reveal that mitochondria have a central role in buffering neuronal [Ca2+]i changes mediated by non-N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors, and that the variation in recovery times following kainate receptor activation reflects a variable degree of mitochondrial Ca2+ loading. However, unlike NMDA receptor-mediated Ca2+ loads, kainate receptor activation has minimal effects on mitochondrial function.

Activation of glutamate receptors results in an increase in intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in central neurones. This increase can occur as the result of direct influx through glutamate-gated ion channels, as in the case of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and certain subtypes of non-NMDA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA)/kainate) receptors, through neuronal depolarization and the subsequent opening of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels, or by the production of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Mayer & Miller, 1990). Neuronal Ca2+ influx following ionotropic receptor activation results in the activation of a variety of intracellular signals, including some that are ultimately neurotoxic (Mayer & Miller, 1990). Interestingly, the activation of both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors results in [Ca2+]i changes that are of similar magnitude when estimated with fluorescent dyes such as fura-2 and indo-1 (Michaels & Rothman, 1990; Dubinsky & Rothman, 1991; Tymianski, Charlton, Carlen & Tator, 1993; Lu, Yin, Chiang & Weiss, 1996). However, whereas intense NMDA receptor activation for as little as 5 min can induce Ca2+-dependent delayed neurotoxicity, much more prolonged activation of non-NMDA receptors is necessary to achieve a similar degree of injury (Koh, Goldberg, Hartley & Choi, 1990). This suggests that there must be an important difference in some aspect of the [Ca2+]i increase triggered by non-NMDA receptors that is not sufficient to support the induction of delayed toxicity. However, the specific features that distinguish the Ca2+ movements associated with the rapid induction of neuronal injury following NMDA receptor activation from non-NMDA receptor-induced [Ca2+]i changes that are less toxic are not well understood. The basis for this important difference may lie in a differential Ca2+ loading that is not evident from the conventionally used fluorescent dyes (Hartley, Kurth, Bjerkness, Weiss & Choi, 1993; Eimerl & Schramm, 1994; Lu et al. 1996). Alternatively, it is possible that the mechanisms responsible for buffering Ca2+ loads induced by the two stimuli are different.

A number of cellular mechanisms are available to buffer [Ca2+]i changes (Miller, 1991; Pozzan, Rizzuto, Volpe & Meldolesi, 1994). Neurones are endowed with an as yet unidentified endogenous buffer capacity that is responsible for absorbing Ca2+ following very short stimuli (Neher, 1995). Longer stimuli, such as those associated with neurotoxicity, require pumping processes to compartmentalize or extrude Ca2+ (Miller, 1991). Previous studies that have focused on NMDA receptor-mediated Ca2+ loads have suggested that Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria is an important mechanism for buffering [Ca2+]i changes, and that mitochondria become progressively more important as the intensity of the stimulus increases (White & Reynolds, 1995, 1997; Wang & Thayer, 1996; Khodorov, Pinelis, Storozhevykh, Vergun & Vinskaya, 1996). It has also become evident that mitochondrial Ca2+ loading shapes the recovery from increases in [Ca2+]i because the time necessary for [Ca2+]i to return to baseline following NMDA receptor activation is dominated by the Ca2+ release from the mitochondrial pool that is mediated by mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange (Nicholls & Akerman, 1982; Kiedrowski & Costa, 1995; Wang & Thayer, 1996; White & Reynolds, 1997). However, the contribution of mitochondria to the buffering of [Ca2+]i triggered by non-NMDA receptor activation has not been defined. Neuronal plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange also plays an important role in Ca2+ extrusion, because extracellular Na+ removal delays recovery somewhat following NMDA receptor activation, and because block of plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange enhances the neurotoxicity of glutamate (Hartley & Choi, 1989; Andreeva, Khodorov, Stelmashook, Cragoe & Victorov, 1991; White & Reynolds, 1995). However, plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange is a reversible process, and the elevated [Na+]i and depolarization associated with non-NMDA receptor activation decreases the gradient for Na+ entry and Ca2+ extrusion, or may even mediate Ca2+ influx (Eisner & Lederer, 1985; Hoyt, Arden, Aizenman & Reynolds, 1998). Thus, based on data obtained in cerebellar granule neurones it has been suggested that the magnitude of the [Na+]i change will have a critical role in the buffering of glutamate- and kainate-induced [Ca2+]i changes (Kiedrowski, Brooker, Costa & Wroblewski, 1994a; Kiedrowski, Wroblewski & Costa, 1994b; Courtney, Enkvist & Akerman, 1995; Wang & Thayer, 1996), because the effectiveness of plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange in extruding Ca2+ depends on the relative Na+ gradient and the membrane potential.

In the present study we have investigated the mechanisms responsible for buffering kainate-induced [Ca2+]i changes in an attempt to determine whether the Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms can provide any insight into the differential toxicity of kainate compared with NMDA in light of ostensibly similar [Ca2+]i changes. We have investigated the role of both Na+ and mitochondria in the buffering of kainate-induced [Ca2+]i changes using embryonic rat cultured forebrain neurones. These data demonstrate that, although extracellular Na+ can regulate the recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline following a kainate stimulus, it is not the principal determinant of the characteristics of the recovery process. We have also established that mitochondria have an important role both in transporting Ca2+ and in shaping the recovery phase of the [Ca2+]i transient, and may account for the variation seen in the recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline after kainate receptor activation. However, although the mitochondria unequivocally transport Ca2+ following kainate stimulation, under these conditions kainate does not alter the mitochondrial membrane potential. This distinguishes the kainate-induced [Ca2+]i signal from that previously observed with NMDA receptor activation where mitochondrial depolarization is a prominent, Ca2+-dependent response (White & Reynolds, 1996).

METHODS

Materials

Fluorescent dyes were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Kainate was obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, USA). Cell culture media were obtained from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). CGP-37157 was a generous gift from Ciba-Geigy (Basel, Switzerland). All of the other chemicals were obtained from Sigma.

Cell culture

Forebrain neurones were cultured from embryonic day 17 Sprague- Dawley rat pups exactly as previously described (White & Reynolds, 1995). This preparation contains neurones from the entire cortical lobe, and thus contains cortical, striatal and hippocampal neurones, amongst others. Pregnant rats were deeply anaesthetized with diethyl ether and were not allowed to regain consciousness. Embryos were then taken and used to obtain forebrain neurones. All animal handling procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh.

After cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips, the coverslips were inverted to prevent glial growth and maintained in vitro for 12-19 days until use. On the day of use the culture medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10 % donor horse serum, 24 units ml−1 penicillin and 24 μg ml−1 streptomycin) was removed and the coverslips were rinsed with a Hepes-buffered salt solution (HBSS) of the following composition (mm): 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.9 MgSO4, 1.4 CaCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 5.6 glucose, and 20 Hepes; adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Coverslips were then inverted and the cells loaded with dyes as described below. Na+-free buffer contained (mm): 140 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 0.9 MgSO4, 1.4 CaCl2, 5 KHCO3, 0.6 K2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 5.6 glucose, and 20 Hepes; adjusted to pH 7.4 with HCl.

Indo-1 measurements

[Ca2+]i was measured from individual neurones using indo-1 microfluorimetry as previously described (White & Reynolds, 1995). Neurones were loaded with 5 μm indo-1 AM in HBSS supplemented with 5 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin for 45-60 min at 37°C, and incubated for a further 15-20 min to allow dye cleavage. Coverslips were then mounted in a recording chamber which was placed on the stage of a Nikon Diaphot microscope. Cells were illuminated by a 100 W mercury arc lamp for 50 ms of each 1 s period using a computer-controlled shutter (Uniblitz VA10; Vincent Associates, Princeton, NJ, USA), at 350 nm. Emission was simultaneously determined at 405 and 490 nm using a dual photomultiplier system (obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Biomedical Instrumentation Group). Ratios were generated from background-subtracted fluorescence values at each wavelength. Coverslips were perfused with HBSS at approximately 20 ml min−1 for the duration of the experiment. This resulted in an exchange of the chamber volume of 1.5-2 ml more than ten times per minute. In a typical experiment, basal ratios were collected for 2-3 min, after which kainate (100 μm) was applied for 15 s. Cells were allowed to recover for 15-20 min, at which point the second kainate stimulus was applied. Modifications to the recovery were usually made by adding drugs to the perfusate at the point at which the second kainate application was washed out. Drugs were typically applied for 2 min. Ratios were converted to [Ca2+]i values using parameters derived from an in situ calibration approach as previously described (White & Reynolds, 1995).

SBFI and fluo-3 measurements

Intracellular free Na+ ([Na+]i) and [Ca2+]i were additionally measured using a CCD-based imaging system. Neurones were loaded for 60 min with 10 μm SBFI AM in HBSS supplemented with 5 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin and 0.1 % Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes). After 60 min 3 μm fluo-3 AM was added and the incubation continued for an additional 20 min. Cells were mounted in a recording chamber that was placed on the stage of a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope, and perfused with HBSS at 20 ml min−1. Fields of cells were illuminated using a 75 W xenon bulb-based monochromator (Applied Scientific Instrumentation, Eugene, OR, USA) at 345 ± 6 nm and 375 ± 6 nm (SBFI) or 504 ± 6 nm (fluo-3). Light from the monochromator passed through a quartz light guide and neutral density filters, which attenuated the light by > 99 %. A 515 nm dichroic mirror reflected light onto the sample through a × 40 oil-immersion objective lens. Collected light passed through a 535 ± 12.5 nm bandpass emission filter and was projected onto an intensified CCD camera (CCD 72 STX camera fitted with a Gen II Sys image intensifier; Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN, USA). Ten frames were averaged for each data point collected at each wavelength. Illumination and acquisition were controlled using SIMCA software (Compix Inc., Cranberry, PA, USA). Using this approach, SBFI and fluo-3 could be measured individually or simultaneously. When the two dyes were used simultaneously the SBFI signal was corrected for a small amount of signal that derived from fluo-3 (usually less than ∼11 % of the 375 nm signal and ∼5.5 % of the 345 nm signal). [Na+]i was derived from 345 nm/375 nm ratios using in situ calibration parameters determined as previously described (Stout, Li-Smerin, Johnson & Reynolds, 1996). No attempt was made to calibrate the fluo-3 signal, which is expressed as arbitrary units corrected for background fluorescence. The same experimental protocol as described above for indo-1 measurements was used except that background values from cell-free regions of the coverslip were continuously determined during the experiment.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

Semi-quantitative estimates of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm) were made using the dye JC-1 as previously reported (White & Reynolds, 1996). Neurones were loaded with dye (3 μm) for 20 min at 37°C, rinsed in dye-free HBSS for 20 min at room temperature (22-25°C), and then mounted on the stage of an ACAS 570c confocal microscope. Fields were illuminated using the 488 nm line of an argon laser, and emission at 530 and 590 nm was monitored. Emitted light was passed through a pinhole to limit data acquisition to a horizontal slice that was approximately 1 μm thick. Solution changes in this protocol were made by aspirating and replacing the contents of the recording chamber. Ratio values were obtained by dividing the signal at 590 nm by the signal at 530 nm after background subtraction. Ratios were then normalized to a starting value of 1 for comparison between cells. Using this approach a decrease in the normalized ratio represents mitochondrial depolarization.

Statistics

Mean data are presented as means ±s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc correction for multiple comparisons, or by Student's two-tailed t test as appropriate, using commercially available software (Prism, GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of recovery following kainate stimulation

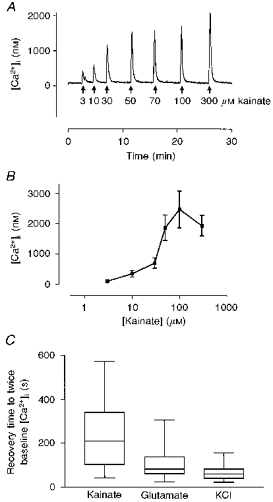

Our previous studies demonstrated that the characteristics of recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline after a glutamate stimulus were dependent upon the glutamate concentration (White & Reynolds, 1997). We therefore first investigated the concentration dependence of kainate-induced [Ca2+]i changes in order to determine a maximal concentration. Figure 1A illustrates a typical concentration-response relationship, and summary data are shown in Fig. 1B. On the basis of these experiments we chose 100 μm kainate for the subsequent studies. As a just maximal concentration of agonist, this concentration of kainate can be considered to be equivalent to 3 μm glutamate that we previously characterized (White & Reynolds, 1995). However, it is important to note that the 3 μm glutamate response is mediated almost entirely by NMDA receptors (Hoyt, Rajdev, Fattman & Reynolds, 1995). Recovery to baseline [Ca2+]i was slower following kainate application than following KCl stimulation (50 mm, 15 s), and was also slower than recovery from a glutamate stimulus (3 μm with 1 μm glycine; Fig. 1C). Interestingly, the inter-cell variation in the recovery time was substantially greater following 15 s kainate stimulation compared with the other stimuli (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Concentration-response relationship for kainate-stimulated [Ca2+]i changes in cultured rat forebrain neurones.

A, typical concentration-response data obtained in a single neurone. Kainate at the concentrations indicated was applied to a single indo-1-loaded neurone for 15 s at the times shown by the arrows. B, mean concentration-response data for kainate-induced increases in [Ca2+]i. Each data point represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 8-12 experiments. C, comparison of recovery times between agonists that increase [Ca2+]i. The time for [Ca2+]i to recover to twice the prestimulus baseline was measured following 15 s stimulation with 100 μm kainate (n= 41 neurones), 3 μm glutamate with 1 μm glycine (n= 72) or 50 mm KCl (n= 35). The data are presented as a Tukey box plot, where the horizontal line through the bar represents the mean, the bar represents the interquartile range and the error bars the 95th percentile.

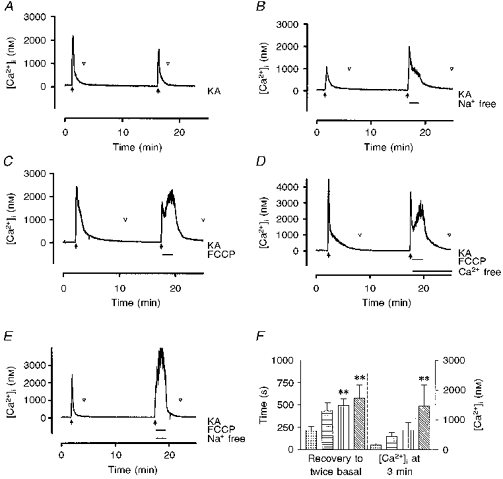

We next examined the effects of manipulating the major Ca2+ buffering systems on the recovery from a 15 s kainate stimulus (Fig. 2). In untreated cells the peak of the second kainate response was 68 ± 4 % (n= 12) of the first (Fig. 2A). The recovery times of the first and second responses were similar (162 ± 35 and 213 ± 45 s, respectively, n= 12). We expressed the recovery both as time required for [Ca2+]i to return to twice basal concentrations and as the [Ca2+]i 3 min after agonist removal. The first parameter represents the time taken for the kainate-induced transient to almost entirely recover to baseline, while the second parameter reflects the state of the cell at a relatively short period after agonist removal. In general, these two parameters followed each other. However, as will be seen below, in some experimental conditions they markedly diverged.

Figure 2. Effects of manipulating extracellular Na+ and Ψm on recovery from kainate-induced [Ca2+]i changes.

A, control trace in which kainate (KA, 100 μm) was added (filled arrows) for 15 s twice with a 15 min interval between drug applications. In control experiments the second response was 68 % of the first (n= 12). The point at which [Ca2+]i recovered to twice basal concentration is indicated by the open arrowheads. B, removal of extracellular Na+ ([Na+]o) for the first 2 min of kainate washout resulted in a small increase in the peak response (to 84 % of the first response, n= 9, P > 0.05) and a marked delay in the recovery to baseline. Reintroduction of [Na+]o accelerated the recovery process. C, addition of 750 nm FCCP for the first 2 min of kainate washout initially had no effect but then elevated [Ca2+]i to a level equal to or exceeding the initial peak. Washout of FCCP resulted in a prompt recovery to baseline. D, when FCCP was applied in Ca2+-free HBSS the extent of the recovery from the kainate peak was typically greater but FCCP still induced a secondary rise in [Ca2+]i consistent with the release from an intracellular (presumably mitochondrial) pool. As this peak was smaller than that observed in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ there is likely to be some on-going Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane during exposure to FCCP in normal HBSS. E, simultaneous removal of [Na+]o and addition of FCCP resulted in an increase in [Ca2+]i that promptly recovered upon return to HBSS. These traces are from representative experiments. F, mean data showing the time taken for [Ca2+]i to recover to twice basal concentrations (left) and the [Ca2+]i at 3 min following agonist washout (right) for the experiments represented in A-E.  , HBSS;

, HBSS;  , Na+ free;

, Na+ free;  , FCCP;

, FCCP;  , FCCP-Na+ free. The data represent means ±s.e.m. of 7-12 experiments. ** Significantly different from HBSS condition, ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test, P < 0.05.

, FCCP-Na+ free. The data represent means ±s.e.m. of 7-12 experiments. ** Significantly different from HBSS condition, ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test, P < 0.05.

The removal of extracellular Na+ during the recovery did not significantly alter the peak of the second response (84 ± 15 % of the first response, n= 9) but slightly delayed the recovery to twice basal concentration (Fig. 2B and F). Our previous studies demonstrated that the addition of 750 nm carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) rapidly depolarizes mitochondria in neurones and thereby dissipates the gradient that drives Ca2+ uptake into this organelle (Nicholls & Akerman, 1982; White & Reynolds, 1996). The addition of FCCP during the washout of kainate caused a secondary rise in [Ca2+]i after a short delay (Fig. 2C) and significantly delayed recovery. This phenomenon is unlikely to be due to Ca2+ influx because the addition of FCCP in Ca2+-free HBSS reduced but did not eliminate the effect (Fig. 2D). Thus, this secondary rise was most probably due to release of Ca2+ from a mitochondrial pool. The addition of FCCP in Na+-free buffer further accentuated this secondary rise in [Ca2+]i, and prevented recovery of [Ca2+]i until the cell was returned to Na+-containing, drug-free HBSS (Fig. 2E).

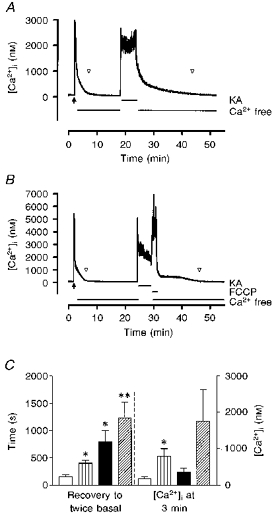

We have demonstrated previously that the time taken for [Ca2+]i to recover from a glutamate stimulus is increased if the duration of exposure to glutamate is increased (White & Reynolds, 1997). We explored this phenomenon in the present study using a 5 min exposure to 100 μm kainate (Fig. 3). In these experiments each kainate stimulus was washed out with Ca2+-free buffer to preclude Ca2+ entry during recovery. Prolonging the exposure to kainate significantly increased the recovery time (Fig. 3A and C) compared with 15 s agonist exposure. As mitochondria play an increasingly important role in the buffering of [Ca2+]i following longer glutamate stimuli, we investigated their role in this protocol by using FCCP. The addition of FCCP after exposure to kainate for 5 min also produced a secondary rise in [Ca2+]i, and was associated with a further small increase in the recovery time (Fig. 3B and C). Although there was a substantial change in the mean [Ca2+]i 3 min after washout of kainate in an FCCP-containing solution this effect was quite variable and did not reach significance.

Figure 3. Effects of increasing the duration of the kainate stimulus on recovery time.

A, to evaluate the recovery properties of [Ca2+]i with more intense stimuli the duration of the second kainate exposure was increased to 5 min. The recovery of [Ca2+]i in these experiments was measured in Ca2+-free HBSS. The point at which [Ca2+]i recovered to twice basal concentration is indicated by the open arrowheads. B, when FCCP was added after the 5 min kainate stimulus there was typically a small increase in [Ca2+]i. This decreased after FCCP was washed out, but cells still took longer to return to baseline compared with controls. These traces are from representative experiments. C, a comparison of recovery times shows that FCCP delayed recovery in Ca2+-free HBSS after both 15 s and 5 min of kainate exposure. □, Ca2+ free, 15 s;  , FCCP-Ca2+ free, 15 s; ▪, Ca2+ free, 5 min;

, FCCP-Ca2+ free, 15 s; ▪, Ca2+ free, 5 min;  , FCCP-Ca2+ free, 5 min. * Significantly different from 15 s Ca2+-free condition, P < 0.05, t test. ** Significantly different from 15 s Ca2+-free condition with FCCP, P < 0.05, t test. The data represent means ±s.e.m. of 8-10 cells in each condition.

, FCCP-Ca2+ free, 5 min. * Significantly different from 15 s Ca2+-free condition, P < 0.05, t test. ** Significantly different from 15 s Ca2+-free condition with FCCP, P < 0.05, t test. The data represent means ±s.e.m. of 8-10 cells in each condition.

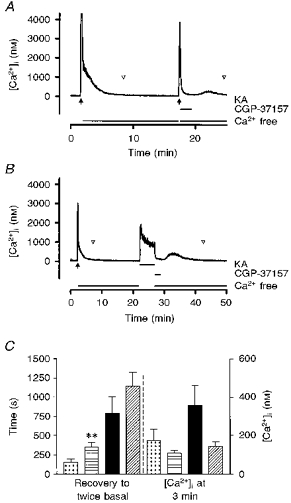

The duration of the post-stimulus recovery following NMDA receptor activation of [Ca2+]i in neurones is heavily influenced by mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange activity, which is likely to be the predominant mechanism for mitochondrial Ca2+ release in these cells (Kiedrowski & Costa, 1995; Wang & Thayer, 1996; White & Reynolds, 1997). The preceding experiments with FCCP suggested that kainate stimulation might result in the accumulation of a significant mitochondrial Ca2+ pool. To test this hypothesis we added the mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange inhibitor CGP-37157 to neurones after kainate stimulation (Fig. 4). In a neurone with a prominent ‘shoulder’ on the [Ca2+]i recovery following the first control kainate application, CGP-37157 produced a more rapid recovery from a 15 s kainate challenge, followed by a delayed secondary rise in [Ca2+]i that occurred in Ca2+-free HBSS (Fig. 4A). When added after a 5 min kainate stimulation, CGP-37157 also hastened the initial phase of recovery. Moreover, the delayed rise in [Ca2+]i was typically more pronounced following the longer stimulation (Fig. 4B). When recovery to twice basal [Ca2+]i was used as the index of recovery time the recovery in the presence of CGP-37157 was apparently delayed to a small degree (Fig. 4C). This delay occurred because the secondary rise was superimposed on the initial recovery. When the [Ca2+]i 3 min after kainate washout was used as the recovery index (which represents 1 min after the washout of CGP-37157) it became apparent that inhibition of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange resulted in a somewhat lower [Ca2+]i 3 min after agonist washout (Fig. 4C), although this period of drug exposure was not sufficient to allow [Ca2+]i to return to twice basal concentrations. This phenomenon was also observed following glutamate stimulation (White & Reynolds, 1997).

Figure 4. Effects of inhibition of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange on recovery from a kainate stimulus.

The mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange inhibitor CGP-37157 (25 μm) was added for 2 min after a 15 s kainate stimulus (A) or a 5 min kainate stimulus (B), with 100 μm agonist in each case. The point at which [Ca2+]i recovered to twice basal concentration is indicated by the open arrowheads. When the recovery time was monitored (C) CGP-37157 had the effect of slightly increasing the apparent recovery time because [Ca2+]i does not return to twice basal prior to the onset of the secondary rise in [Ca2+]i when CGP-37157 is washed out. However, a comparison of the [Ca2+]i 3 min after washout of kainate (i.e. 1 min after removal of CGP-37157) reveals a trend towards greater [Ca2+]i recovery in the drug-treated cells before the secondary rise occurred.  , Ca2+ free, 15 s;

, Ca2+ free, 15 s;  , CGP-37157-Ca2+ free, 15 s; ▪, Ca2+ free, 5 min;

, CGP-37157-Ca2+ free, 15 s; ▪, Ca2+ free, 5 min;  , CGP-37157-Ca2+ free, 5 min. These data represent means ±s.e.m. of 8-10 cells in each condition. ** Significantly different from 15 s Ca2+-free condition, P < 0.05, t test.

, CGP-37157-Ca2+ free, 5 min. These data represent means ±s.e.m. of 8-10 cells in each condition. ** Significantly different from 15 s Ca2+-free condition, P < 0.05, t test.

The effect of kainate on mitochondrial function

Several recent studies have shown that intense NMDA receptor activation can result in mitochondrial depolarization, apparently through mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and activation of the permeability transition pore (PTP) (Ankarcrona et al. 1995; White & Reynolds, 1996; Schinder, Olson, Spitzer & Montal, 1996). Since the preceding experiments provided strong evidence for kainate-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, we sought to determine whether kainate alters mitochondrial function as shown by an alteration in the mitochondrial membrane potential, Ψm. We monitored the fluorescence signal from JC-1-loaded neurones and added 100 μm kainate for 5 min (Fig. 5). Kainate alone had no effect on the JC-1 signal either during exposure or during washout. As depolarization of Ψm is a consequence of increased mitochondrial Ca2+, inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux should result in increased intra-mitochondrial Ca2+ and potentiate any effects of kainate. The addition of CGP-37157 alone increased the JC-1 ratio, consistent with previous observations (White & Reynolds, 1997) and suggesting the presence of on-going mitochondrial Ca2+ cycling. The addition of CGP-37157 in the presence of kainate resulted in changes in the JC-1 ratio that were indistinguishable from the effects of CGP-37157 alone. FCCP produced a marked and rapid mitochondrial depolarization regardless of the stimulus history of the cells. Thus, although kainate stimulation apparently results in the generation of a mitochondrial Ca2+ pool, this pool is evidently insufficient to alter Ψm as revealed by JC-1.

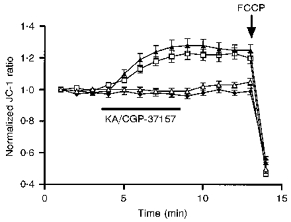

Figure 5. Kainate stimulation does not change Ψm.

Kainate (100 μm) was applied to neurones loaded with the potential-sensitive dye JC-1 as indicated by the horizontal bar. CGP-37157 (25 μm) when used was applied at the same time. ♦, control; ▵, KA; □, CGP-37157; ▴, KA-CGP-37157. Neurones were exposed to drugs for 5 min after which the drugs were removed by exchanging the buffer in the recording chamber 4 times with HBSS. FCCP (750 nm) was added at the time indicated by the arrow as a positive control to illustrate mitochondrial depolarization. These data represent the ratio of JC-1 emission measured at 530 and 590 nm. The ratios were then normalized to unity before averaging to limit the cell-to-cell variation. The actual mean non-normalized JC-1 ratio (590 nm/530 nm) was 1.27 ± 0.03 (n= 129 cells) in these experiments. Kainate did not depolarize the cells when added alone or in the presence of CGP-37157. As we have previously noted, CGP-37157 increased Ψm, presumably as a result of increasing intramitochondrial Ca2+. These data represent means ±s.e.m. of 28-43 cells from at least 3 different experiments under each condition.

What is the basis for the variation in the [Ca2+]i recovery time?

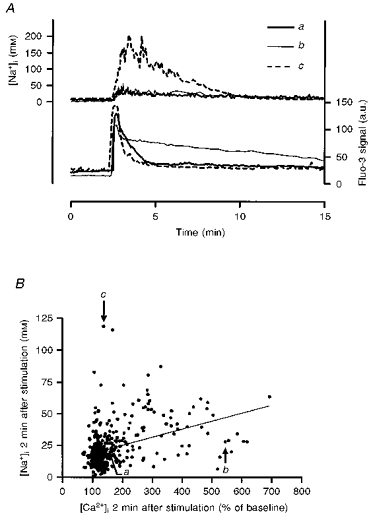

The preceding experiments suggest a role for both plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange and mitochondria in buffering kainate-induced Ca2+ loads. As noted in Fig. 1C, we encountered substantial variation in the recovery time of [Ca2+]i to baseline after brief kainate stimulation. Previous studies in cerebellar granule cells have suggested that the [Na+]i might be a critical variable in buffering Ca2+ loads (Kiedrowski et al. 1994a, b). As the Na+ gradient is the principal driving force for plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange-mediated extrusion of Ca2+, large or prolonged elevation of [Na+]i could account for the delay in recovery of [Ca2+]i that we observed in some cells. To test this hypothesis we simultaneously measured [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i using SBFI and fluo-3, respectively. The addition of kainate to SBFI- fluo-3-loaded cells resulted in a rapid increase in the fluo-3 signal and an increase in the SBFI ratio that was slightly delayed compared with fluo-3 (Fig. 6). In addition, the [Na+]i generally returned to baseline much more slowly than the fluo-3 signal (Fig 6A and Fig 7A). As shown in Fig. 6A, there was significant inter-cell variation in the extent of recovery of [Ca2+]i following kainate stimulation. However, the rate of recovery of [Ca2+]i did not appear to correlate well with the rate of recovery of [Na+]i (compare a with b in Fig. 6A). Regression analysis comparing the extent of recovery of the two ions at 2 min post-stimulation showed only a weak correlation (Fig. 6B; r2= 0.16, slope significantly different from zero, P < 0.0001).

Figure 6. Relationship between the recovery of [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i following kainate stimulation.

Cells were stimulated with kainate (100 μm) for 15 s and [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i were monitored simultaneously using fluo-3 and SBFI, respectively. A, inter-cell variation in [Ca2+]i recovery rates and lack of correlation between [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i recoveries are illustrated for 3 individual neurones from a single coverslip. The fluo-3 signal is expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.) corrected for background fluorescence. B, lack of correlation between Na+ and Ca2+ recovery. The extent of recovery, expressed as percentage of baseline fluorescence for fluo-3 and as millimolar [Na+]i for SBFI, was estimated 2 min after kainate washout. A linear regression of these data generated a slope that was significantly different from zero (P < 0.0001), but with a regression coefficient of 0.159. The labelled cells correspond to the traces shown in A, while a total of 417 neurones were included in this analysis from 20 separate experiments.

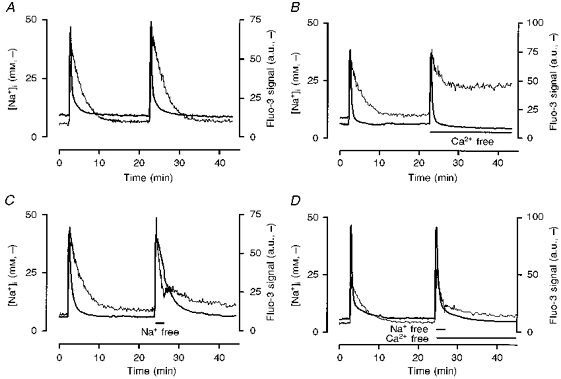

Figure 7. Effects of extracellular Ca2+ and Na+ manipulation on [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i recovery.

[Ca2+]i and [Na+]i were determined with fluo-3 and SBFI, respectively. The fluo-3 signal is expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.) corrected for background fluorescence. A, control experiment showing that repeated exposures to kainate (100 μm) for 15 s generated reproducible responses. Note also that [Na+]i reached a peak later than [Ca2+]i in all coverslips tested (13.8 ± 0.91 s later, P < 0.0001, paired t test). B, removal of extracellular Ca2+ following the second stimulus resulted in a [Ca2+]i recovery rate that was faster than control, but produced only a partial recovery of [Na+]i. C, removal of extracellular Na+ during the first 2 min of washout of the second kainate stimulus slowed the recovery of [Ca2+]i but increased the rate of recovery of [Na+]i. Reintroduction of extracellular Na+ slowed the subsequent rate of recovery of [Na+]i and initially accelerated the rate of recovery of [Ca2+]i. D, the effects of extracellular Ca2+ removal on [Na+]i were offset by the simultaneous removal of extracellular Na+. These traces are averages of the responses of 10-36 cells from a single representative experiment in each case, which was repeated an additional 4 times with similar results. Mean data from these experiments are provided in Table 1.

To further explore the relationship between [Na+]i and the recovery of [Ca2+]i after kainate stimulation we tested the effects of removing extracellular Ca2+ and Na+ during washout. We observed that removal of extracellular Ca2+ during recovery from kainate application resulted in a modest but prolonged elevation of [Na+]i. Figure 7B illustrates that this elevation of [Na+]i associated with extracellular Ca2+ removal did not delay the recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline after kainate washout (Table 1). We have previously shown that removal of extracellular Na+ rapidly decreases [Na+]i in these cells (Stout et al. 1996). We exploited this protocol to achieve a more rapid decrease in [Na+]i following kainate removal (Fig. 7C). Replacing extracellular Na+ with N-methyl-d-glucamine resulted in a more rapid decrease in [Na+]i compared with control cells. However, in this case [Ca2+]i declined more slowly (Fig. 7C and Table 1), which is consistent with our previous observations about the contribution of extracellular Na+ to recovery (White & Reynolds, 1995). Finally, removal of both extracellular Na+ and Ca2+ during recovery had no significant effect on the recovery of [Ca2+]i, and the elevation in [Na+]i was no longer apparent (Fig. 7D and Table 1). Collectively, these results suggest that although the presence or absence of extracellular Na+ can alter the characteristics of the buffering of [Ca2+]i changes, [Na+]i does not appear to be a critical determinant of [Ca2+]i recovery because neither the magnitude of the [Na+]i elevation nor experimental depression of [Na+]i fundamentally altered the capability of neurones to restore [Ca2+]i to baseline values.

Table 1.

Comparison of [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i at 2 min following washout in Ca2+-free, Na+-free, or Ca2+- and Na+-free buffers

| Condition | [Ca2+]1 (%) | [Na+]1 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 33.6 ± 4.7 | 73.7 ± 4.9 |

| Ca2+ free | 23.5 ± 4.0 | 80.0 ± 2.6 |

| Na+ free | 63.2 ± 4.8 * | 47.4 ± 4.5 * |

| Ca2+, Na+ free | 24.6 ± 3.4 | 55.3 ± 3.7 * |

Neurones were stimulated with kainate (100 μm) for 15 s. Values shown are the respective intracellular ion concentration measured 2 min after agonist washout as a percentage of the peak value determined in the presence of agonist. The fluo-3 signal was measured as background-subtracted fluorescence intensity, while the SBFI data have been converted from ratios into [Na+]i as described in Methods. These data represent means ±s.e.m. of 5 different coverslips, with 10-36 cells for each coverslip.

Significantly different from control (P < 0.05, ANOVA with Dunnett's correction for multiple comparisons).

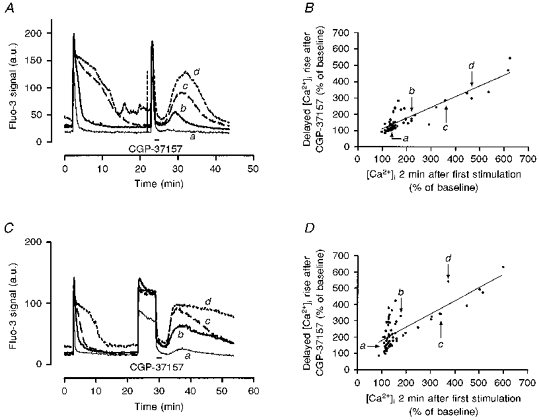

In the absence of a compelling role for [Na+]i in the variable recovery of [Ca2+]i we hypothesized that mitochondrial uptake might represent the critical determinant of recovery time. As noted above, inhibition of the release of the mitochondrial Ca2+ pool with CGP-37157 resulted in the more rapid recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline (Fig. 4). This suggested that the slowest recovery could be associated with the greatest degree of mitochondrial Ca2+ loading. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the control rate of [Ca2+]i recovery following the first kainate stimulus with the size of the delayed [Ca2+]i rise induced by the addition and subsequent removal of CGP-37157 following the second kainate stimulus (Fig. 8). We observed an interesting association between recovery time and the magnitude of the delayed [Ca2+]i rise using this protocol. In general, neurones that recovered from kainate application quickly produced rather small delayed increases in [Ca2+]i upon washout of the inhibitor, whereas neurones that recovered slowly showed larger delayed rises. This was true whether kainate was applied for 15 s or 5 min (Fig. 8), although the delayed rise tended to be larger and more prolonged following 5 min of kainate application. This is consistent with greater mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake resulting from the longer agonist exposure. An analysis of the correlation between recovery from the first stimulus and delayed [Ca2+]i rise (Fig. 8B and D) indicated that most of the cells that recovered slowly from the first stimulation produced substantial delayed rises (r2= 0.78 following 15 s stimulation, r2= 0.61 following 5 min stimulation). Thus, the variation in the recovery of [Ca2+]i following kainate stimulation appears to be due to differences in the extent of mitochondrial Ca2+ loading, and is consistent with the suggestion that the rate of mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux is fixed while the rate of Ca2+ accumulation depends on the cellular Ca2+ load (Nicholls & Akerman, 1982).

Figure 8. Correlation between rate of recovery of [Ca2+]i following kainate stimulation and mitochondrial Ca2+ loading.

A, neurones were stimulated with kainate (100 μm) for 15 s, allowed to recover for 20 min, and stimulated again with kainate for 15 s. The mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange inhibitor CGP-37157 (25 μm) was added for the first 2 min of washout of the second kainate response. Representative traces are shown from individual neurones from a single experiment that showed fast, intermediate and slow recoveries from the first stimulation. The fluo-3 signal is expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.) corrected for background fluorescence. B, correlation between the rate of [Ca2+]i recovery and the size of the secondary [Ca2+]i rise following CGP-37157 washout, both expressed as percentage of baseline fluorescence. There are clearly a number of cells that were very close to baseline [Ca2+]i after 2 min of recovery, and these cells usually showed rather small secondary rises. In contrast, cells that recovered more slowly showed larger rises after the second stimulus (r2= 0.784, n= 53). The points representing the cells illustrated in A are shown. C, the experimental protocol was the same except that neurones were stimulated by kainate (100 μm) for 5 min for the second stimulus. Individual neurones from a single experiment exhibiting slow, intermediate and fast recovery from the first stimulus are shown for comparison. The mean size of the secondary rise in [Ca2+]i was significantly larger following the 5 min stimulation compared with the 15 s stimulation with 100 μm kainate (240.2 ± 14.0 % of baseline after 5 min compared with 175.2 ± 12.7 % for 15 s, P < 0.001, t test). D, correlation between the rate of [Ca2+]i recovery and the secondary rise in [Ca2+]i following CGP-37157 treatment. In this case more of the cells that recovered quickly after the first, short stimulus showed secondary rises following CGP-37157 washout. Nevertheless, for a number of the cells there was a clear relationship between the extent of recovery from the first stimulus and the size of the secondary rise (r2= 0.606, n= 64).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have examined the mechanisms responsible for buffering of kainate-induced intracellular Ca2+ loads. Our results demonstrate that most of the buffering can be attributed to the mitochondria and Ca2+ efflux mediated by plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange. In particular, mitochondrial Ca2+ transport appears to make a much more substantial contribution to Ca2+ buffering following kainate stimulation than has previously been appreciated. A role for Ca2+ transport into mitochondria is clearly indicated by the impact of FCCP on the rate of recovery (Fig. 2). That Ca2+ is transported into and is accumulated by mitochondria is also suggested by the effects of inhibiting the major physiological mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux pathway, mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange, with CGP-37157 (Fig 4 and Fig 8). Surprisingly, however, kainate-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ transport is not associated with a detectable change in Ψm (Fig. 5), which might provide an important clue to the differential toxicity of kainate compared with NMDA receptor-mediated [Ca2+]i changes.

In contrast to previous studies (Kiedrowski et al. 1994a, b) we found that the interaction of [Na+]i with plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange does not appear to be a critical determinant governing the recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline values following kainate stimulation. Although elevation of [Na+]i is a prominent event associated with activation of non-NMDA receptors (Pinelis, Segal, Greenberger & Khodorov, 1994; Kiedrowski et al. 1994b; Courtney et al. 1995), we found that it was possible to manipulate [Na+]i without having a major impact on the overall pattern of recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline concentrations. Thus, experimental manipulations that resulted in a modest but prolonged elevation of [Na+]i during recovery (Fig. 7B) did not markedly alter the rate of decline of [Ca2+]i. In fact, this condition was associated with an acceleration of the rate of recovery of [Ca2+]i. In addition, the magnitude of the kainate-induced increase in [Na+]i correlated poorly with the rate of recovery of [Ca2+]i. This is different from the conclusion suggested by Kiedrowski and colleagues (Kiedrowski et al. 1994a, b) who proposed that the elevation of [Na+]i by kainate and the concomitant membrane depolarization would offset the main gradient driving Ca2+ extrusion by plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange. Our results suggest that the magnitude of the [Na+]i observed in forebrain neurones in combination with the presumably depolarized membrane potential is insufficient to markedly change the Ca2+-extruding activity of plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange. Although the gradients for transporting Ca2+ are likely to be altered, the activity of the transporter is sufficient, when combined with the prominent role of mitochondria in transporting and storing Ca2+, to restore [Ca2+]i to very close to baseline values. It is surprising that the effects of extracellular Na+ removal on the recovery of [Ca2+]i were not observed when Na+ and Ca2+ were removed together (Table 1). Extracellular Ca2+ removal would greatly alter the gradient for Ca2+ extrusion from these cells, which would facilitate any other mechanisms that pump Ca2+ across the plasma membrane. However, it is at present unclear which processes may be participating in this Ca2+ transport.

Several previous studies have documented the role of mitochondria in buffering depolarization- or glutamate-induced [Ca2+]i changes in neurones (Thayer & Miller, 1990; Werth & Thayer, 1994; White & Reynolds, 1995; Kiedrowski & Costa, 1995; Wang & Thayer, 1996; Khodorov et al. 1996). However, these previous studies have not explicitly documented the role of mitochondria in kainate-induced [Ca2+]i changes. We were able to infer the role of mitochondria in buffering kainate-induced [Ca2+]i changes in two ways: by depolarizing mitochondria with the protonophore FCCP, which blocks Ca2+ uptake by dissipating the main driving force for uptake, Ψm; and by using CGP-37157 to block Ca2+ release from mitochondria. We (White & Reynolds, 1997) and others (Thayer & Miller, 1990; Wang & Thayer, 1996) have shown that the delayed recovery of [Ca2+]i in neurones following a brief stimulation is likely to be the consequence of prolonged release of Ca2+ following accumulation into mitochondria. FCCP blocks the accumulation of the slowly released pool (Colwell & Levine, 1996; White & Reynolds, 1997). Conversely, CGP-37157 blocks mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange, which appears to be the principal mechanism for the slow release of Ca2+ from mitochondria under these experimental conditions (Colwell & Levine, 1996; White & Reynolds, 1997). Blocking this release results in the rapid recovery of [Ca2+]i to baseline (indicating that plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange is not inhibited by CGP-37157, and is fully capable of extruding cytoplasmic Ca2+), and a subsequent rise in [Ca2+]i following removal of inhibition of the exchanger. In this study we assumed that the magnitude of this late rise in [Ca2+]i reflected the size of the mitochondrial Ca2+ pool. It is certainly possible that the size of the late rise could also be a function of the relative abundance of the exchanger in any given cell, and could also be affected by any regulatory mechanisms that alter the rate of transport of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange. Substantial differences in [Na+]i could also alter exchanger activity. However, there is no documentation of modulation of activation of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange in neurones. Also, we found no correlation between the size of the late rise in [Ca2+]i and the [Na+]i (data not shown). Thus, the late rise in [Ca2+]i appears to be a reasonable surrogate for the size of the mitochondrial Ca2+ pool.

In our previous studies we established that the relative contribution of mitochondria and plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchange changed as the duration of the glutamate stimulus was extended (White & Reynolds, 1997), such that the role of mitochondria became more pronounced as stimuli approached the point at which cell death would ultimately ensue. We also compared the properties of brief (15 s) and more prolonged (5 min) stimuli in this study. We observed an increase in the recovery time as the stimulus duration was extended (Fig 3 and Fig 4). It is also apparent that the pattern of the delayed rise in [Ca2+]i following washout of CGP-37157 is slightly different following the longer agonist exposure (Fig. 8A and C). These data suggest that more intense stimulation results in a greater degree of Ca2+ loading. However, the extent of the increase in recovery time is much less than we previously observed following NMDA receptor activation (White & Reynolds, 1997), so it seems likely that processes of receptor desensitization and/or channel inactivation are much more effective at limiting kainate-induced Ca2+ entry than is the case for NMDA receptors.

In comparison with our previous observations on the mechanisms of Ca2+ buffering following glutamate-induced (mostly NMDA receptor-mediated) [Ca2+]i changes, recovery from kainate-induced changes showed much greater variation (Fig. 1C). There are a number of possibilities to account for this range of responses. The prominent response to kainate receptor stimulation should be Na+ entry, cell depolarization and subsequent Ca2+ entry through voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels (Murphy, Thayer & Miller, 1987). It is also possible that some fraction of these neurones express Ca2+-permeable receptors which could result in an additional more direct Ca2+ load (Hoyt et al. 1995; Lu et al. 1996). Indeed, our previous study showed that essentially all neurones in our culture preparation responded to kainate with an elevation of [Ca2+]i when responses were measured in Na+-free buffer solutions, which is usually interpreted to reflect the presence of Ca2+-permeable non-NMDA receptors. We initially supposed that the difference in the elevation of [Na+]i would account for the variation, and that this could be explained by different densities of non-NMDA receptors between cells. However, our data did not reveal a correlation between the recovery of [Na+]i and the recovery of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 6) suggesting that these variables were not related. Instead, the cells that took longest to recover also showed the largest CGP-37157-induced secondary rise in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 8). From this we infer that these represent the neurones in which kainate stimulation resulted in the largest intramitochondrial Ca2+ pool. This presumably means that these cells also had the largest Ca2+ load, which could reflect the presence or relative density of the Ca2+-permeable form of the receptor (Hoyt et al. 1995; Lu et al. 1996). However, the correlation of these two parameters would require the direct measurement of the intramitochondrial Ca2+ pool in conjunction with a determination of the influx of Ca2+ through the kainate receptor, which we are unable to do at this time. It is also possible that there is inter-neurone variation in the ability of mitochondria to accumulate and/or release Ca2+. In particular, factors that modulate mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange activity would have a substantial influence on the recovery of these responses.

A number of recent studies have documented the Ca2+-dependent effects of NMDA receptor activation on Ψm (Ankarcrona et al. 1995; Isaev, Zorov, Stelmashook, Uzbekov, Kozhemyakin & Victorov, 1996; White & Reynolds, 1996; Schinder et al. 1996; Nieminen, Petrie, Lemasters & Selman, 1996) in several neurone types. Depolarization of Ψm could result either from Ca2+ cycling through mitochondria resulting in net positive charge entry into the matrix (Nicholls & Akerman, 1982), or from opening of the PTP. It is possible too that the former mechanism leads to the latter because PTP activation is also promoted by mitochondrial depolarization (Petronilli, Nicolli, Constanti, Colonna & Bernardi, 1994; Zoratti & Szabo, 1995). An elevation of [Ca2+]i can also result in hyperpolarization of Ψm in these neurones (White & Reynolds, 1996). This is likely to be the consequence of stimulation of respiration by a modest elevation of mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m) below that required to induce PTP. This can also be accomplished by blocking mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange with CGP-37157 (Fig. 5). In view of our ability to demonstrate the presence of a kainate-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ pool using CGP-37157 it is surprising that kainate had no effect on Ψm measured using JC-1. It could be suggested that the increase in [Na+]i that occurs in conjunction with [Ca2+]i promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux through mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange, and that this prevents the excessive build-up in [Ca2+]m. However, if this were the case, the depolarization would have been revealed by the addition of CGP-37157, because inhibition of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange would then have raised [Ca2+]m to a point sufficient to activate the PTP. We have previously documented the ability of NMDA, but not kainate, receptor activation to generate reactive oxygen species using dichlorofluorescin (Reynolds & Hastings, 1995). As PTP activation is also promoted by oxidation (Zoratti & Szabo, 1995) it is possible that the lack of kainate-induced depolarization of Ψm reflects a combination of insufficient Ca2+ entry and inadequate reactive oxygen species generation.

Collectively, then, these findings suggest that the mechanisms responsible for buffering NMDA and non-NMDA receptor-mediated [Ca2+]i changes are rather similar. However, the critical difference may lie in the extent of the Ca2+ load imposed by the two receptor types. The present data suggest that, while kainate receptor activation is sufficient to trigger enough Ca2+ entry to generate a mitochondrial Ca2+ pool, the net mitochondrial Ca2+ load does not rise to the level associated with acute changes in mitochondrial function. Such a conclusion is supported by the observation that kainate causes less net Ca2+ accumulation than NMDA (Hartley et al. 1993), and by more recent studies that suggest that NMDA-induced [Ca2+]i changes are, indeed, larger than those caused by kainate (Hyrc, Handran, Rothman & Goldberg, 1997; Stout & Reynolds, 1998). The larger Ca2+ burden imposed on mitochondria by NMDA receptor activation reinforces the suggestion that Ca2+-triggered alterations in mitochondrial function are the critical event in the most acute forms of NMDA receptor-mediated neuronal injury (Budd & Nicholls, 1996).

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristi Rothermund for the preparation of cell cultures. This work was supported by NIH grants NS 34138 (I. J. R.) and NS 09998 (A. K. S.). I. J. R. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. J. M. C. was supported by a fellowship from the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics.

References

- Andreeva N, Khodorov B, Stelmashook E, Cragoe EJ, Victorov I. Inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchange enhances delayed neuronal death elicited by glutamate in cerebellar granule cell cultures. Brain Research. 1991;548:322–325. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91141-m. 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91141-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankarcrona M, Dypbukt JM, Bonfoco E, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Lipton SA, Nicotera P. Glutamate-induced neuronal death: a succession of necrosis or apoptosis depending on mitochondrial function. Neuron. 1995;15:961–973. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90186-8. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd SL, Nicholls DG. Mitochondria, calcium regulation and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;67:2282–2291. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell CS, Levine MS. Glutamate receptor-induced toxicity in neostriatal cells. Brain Research. 1996;724:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney MJ, Enkvist MOK, Akerman KEO. The calcium response to the excitotoxin kainate is amplified by subsequent reduction of extracellular sodium. Neuroscience. 1995;68:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00211-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubinsky JM, Rothman SM. Intracellular calcium concentrations during ‘chemical hypoxia’ and excitotoxic neuronal injury. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:2545–2551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02545.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimerl S, Schramm M. The quantity of calcium that appears to induce neuronal death. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;62:1223–1226. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62031223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner DA, Lederer WJ. Na-Ca exchange: stoichiometry and electrogenicity. American Journal of Physiology. 1985;248:C189–202. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1985.248.3.C189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley DM, Choi DW. Delayed rescue of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor mediated neuronal injury in cortical culture. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1989;250:752–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley DM, Kurth MC, Bjerkness L, Weiss JH, Choi DW. Glutamate receptor-induced 45Ca2+ accumulation in cortical cell culture correlates with subsequent neuronal degeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:1993–2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-01993.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt KR, Arden SR, Aizenman E, Reynolds IJ. Reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange contributes to glutamate-induced [Ca2+]i increases in cultured rat forebrain neurons. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998 in the Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt KR, Rajdev SR, Fattman CL, Reynolds IJ. Cyclothiazide modulates AMPA receptor-mediated increases in intracellular free Ca2+ and Mg2+ in cultured neurons from rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1995;64:2049–2056. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyrc K, Handran SD, Rothman SM, Goldberg MP. Ionized intracellular calcium concentration predicts excitotoxic neuronal death: observations with low affinity fluorescent calcium indicators. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:6669–6677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06669.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaev NK, Zorov DB, Stelmashook EV, Uzbekov RE, Kozhemyakin MB, Victorov IV. Neurotoxic glutamate treatment of cultured cerebellar granule cells induces Ca2+-dependent collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential and ultrastructural alterations of mitochondria. FEBS Letters. 1996;392:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00804-6. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00804-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodorov B, Pinelis V, Storozhevykh T, Vergun O, Vinskaya N. Dominant role of mitochondria in protection against a delayed neuronal Ca2+ overload induced by endogenous excitatory amino acids following a glutamate pulse. FEBS Letters. 1996;393:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00873-3. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00873-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiedrowski L, Brooker G, Costa E, Wroblewski JT. Glutamate impairs neuronal calcium extrusion while reducing sodium gradient. Neuron. 1994a;12:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90272-0. 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiedrowski L, Costa E. Glutamate-induced destabilization of intracellular calcium concentration homeostasis in cultured cerebellar granule cells: role of mitochondria in calcium buffering. Molecular Pharmacology. 1995;47:140–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiedrowski L, Wroblewski JT, Costa E. Intracellular sodium concentration in cultured cerebellar granule cells challenged with glutamate. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994b;45:1050–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JY, Goldberg MP, Hartley DM, Choi DW. Non-NMDA receptor mediated neurotoxicity in cortical culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:693–705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-02-00693.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YM, Yin HZ, Chiang J, Weiss JH. Ca2+-permeable AMPA/kainate and NMDA channels: High rate of Ca2+ influx underlies potent induction of injury. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5457–5465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05457.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Miller RJ. Excitatory amino acid receptors and regulation of intracellular Ca2+ in mammalian neurons. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1990;11:254–260. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90254-6. 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels RL, Rothman SM. Glutamate neurotoxicity in vitro: antagonist pharmacology and intracellular calcium concentrations. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:283–292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00283.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RJ. The control of neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis. Progress in Neurobiology. 1991;37:255–285. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90028-y. 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90028-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SN, Thayer SA, Miller RJ. The effects of excitatory amino acids on intracellular calcium in single mouse striatal neurons in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:4145–4158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-12-04145.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. The use of fura-2 for estimating Ca buffers and Ca fluxes. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1423–1442. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00144-u. 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00144-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Akerman KEO. Mitochondrial calcium transport. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1982;683:57–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(82)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen A-L, Petrie TG, Lemasters JJ, Selman WR. Cyclosporin A delays mitochondrial depolarization induced by N-methyl-d-aspartate in cortical neurons: evidence of the mitochodrial permeability transition. Neuroscience. 1996;75:993–997. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00378-8. 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronilli V, Nicolli A, Constanti P, Colonna R, Bernardi P. Regulation of the permeability transition pore, a voltage dependent mitochondrial channel inhibited by cyclosporin A. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1187:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelis VG, Segal M, Greenberger V, Khodorov BI. Changes in cytosolic sodium caused by a toxic glutamate treatment of cultured hippocampal neurons. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology International. 1994;32:475–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzan T, Rizzuto R, Volpe P, Meldolesi J. Molecular and cellular physiology of intracellular calcium stores. Physiological Reviews. 1994;74:595–636. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds IJ, Hastings TG. Glutamate induces the production of reactive oxygen species in cultured forebrain neurons following NMDA receptor activation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3318–3327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03318.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinder AF, Olson EC, Spitzer NC, Montal M. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary event in glutamate neurotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:6125–6133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06125.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout AK, Li-Smerin Y, Johnson JW, Reynolds IJ. Mechanisms of glutamate-stimulated Mg2+ and subsequent Mg2+ efflux in rat forebrain neurones in culture. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:641–657. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout AK, Reynolds IJ. High-affinity calcium indicators underestimate increases in intracellular calcium concentrations associated with excitotoxic glutamate stimulations. Neuroscience. 1998 doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00441-2. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SA, Miller RJ. Regulation of the intracellular free calcium concentration in single rat dorsal root ganglion neurones in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1990;425:85–115. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymianski M, Charlton MP, Carlen PL, Tator CH. Source specificity of early calcium neurotoxicity in cultured embryonic spinal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:2085–2104. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02085.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Thayer SA. Sequestration of glutamate-induced Ca2+ loads by mitochondria in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:1611–1621. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth JL, Thayer SA. Mitochondria buffer physiological calcium loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:348–356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondria and Na+/Ca2+ exchange buffer glutamate-induced calcium loads in cultured cortical neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:1318–1328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01318.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial depolarization in glutamate-stimulated neurons: An early signal specific to excitotoxin exposure. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5688–5697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05688.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondria accumulate Ca2+ following intense glutamate stimulation of cultured rat forebrain neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1997;498:31–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoratti M, Szabo I. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1241:139–176. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]