Abstract

We studied the G protein inhibition of heteromultimeric neuronal Ca2+ channels by constructing a series of chimeric channels between the strongly modulated α1B subunit and the α1E(rbEII) subunit, which showed no modulation.

In parallel studies, α1 subunit constructs were co-expressed together with the accessory Ca2+ channel α2-δ and β2a subunits in mammalian (COS-7) cells and Xenopus oocytes. G protein inhibition of expressed Ca2+ channel currents was induced by co-transfection of Gβ1 and Gγ2 subunits in COS-7 cells or activation of co-expressed dopamine (D2) receptors by quinpirole (100 nm) in oocytes.

The data indicate that transfer of the α1B region containing the N-terminal, domain I and the I-II loop (i.e. the α1B1-483 sequence), conferred G protein modulation on α1E(rbEII), both in terms of a slowing of activation kinetics and a reduction in current amplitude.

In contrast, the data are not consistent with the I-II loop and/or the C-terminal forming a unique site for G protein modulation.

G protein inhibition of neuronal N (α1B) and P/Q type (α1A) Ca2+ currents is mediated by Gβγ subunits (Herlitze, Garcia, Mackie, Hille, Scheuer & Catterall, 1996; Ikeda, 1996). Both the intracellular loop that links Ca2+ channel transmembrane domains I and II (DeWaard, Liu, Walker, Scott, Gurnett & Campbell, 1997; Zamponi, Bourinet, Nelson, Nargeot & Snutch, 1997) and a C-terminal sequence (Qin, Platano, Olcese, Stefani & Birnbaumer, 1997) have been implicated as sites at which Gβγ subunits bind to α1 subunits.

Functionally, the site of G protein action remains controversial. Mutations within the I-II loop, and specifically to the arginine residue in a QxxER consensus sequence proposed to be involved in Gβγ binding (Chen et al. 1995), abolish Gβγ binding and prevent the slowing of activation induced by GTPγS (De Waard et al. 1997). In contrast, the same mutation actually enhanced modulation in a different study (Herlitze, Hockerman, Scheuer & Catterall, 1997); whereas conversion of the entire α1A consensus sequence (QIEER) to that in α1C (QQLEE) did attenuate modulation. Transfer of the IS6/I-II loop from α1B to the non-modulated α1E(rbEII) causes some slowing of current activation kinetics in the presence of GTPγS, but does not result in current amplitude modulation (Page, Stephens, Berrow & Dolphin, 1997). In contrast, α1B was reported to retain G protein sensitivity when its I-II loop was replaced by the corresponding sequence from non-modulated α1C (Zhang, Ellinor, Aldrich & Tsien, 1996); their study implicated a role of domain I together with the C-terminal in G protein modulation. However, the G protein inhibition of human α1E appears to be due to Gβγ binding solely at the C-terminal site (Qin et al. 1997).

Here, we examine the potential contribution of regions implicated in G protein modulation using a series of constructs between the strongly modulated α1B subunit and the rat α1E(rbEII) subunit (Soong, Stea, Hodson, Dubel, Vincent & Snutch, 1993), which shows no modulation (Bourinet, Soong, Stea & Snutch, 1996a; Page et al. 1997). The results suggest that the α1B1-483 sequence contains important determinants of G protein modulation.

METHODS

Materials

The following cDNAs were used: rat α1E (rbEII, GenBank accession number L15453); rabbit α1B (D14157); rat β2a (M80545); rat α2-δ (M86621); rat D2long receptor (X77458, N5→G); bovine Gβ1 (M13236), bovine Gγ2 (M37183) and Mut3-Green fluorescent protein (GFP) (U73901).

Production of Ca2+ channel constructs

Individual constructs were produced by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methodology as detailed previously (Page et al. 1997), using lower case letters for C termini and I-II loops and upper case for each of the four transmembrane domains as follows.

α1EbEEE

The pMT2 forward primer, pMT2F (AGC TTG AGG TGT GGC AGG CTT) and the chimeric reverse primer, TCC TGA GAG CAC ACC CAG GAC AAG GTT G, were used with the α1E(rbEII) template; the resulting fragment was used as a primer and extended on the α1EBE1-pMT2 template using the reverse primer, GAC TTC ATG GAG CTC ATC AAG G. The product was digested with Xba I and Acc B7I and subcloned into the corresponding region of the α1E(rbEII)-pMT2 vector. The α1EbEEE construct differs from the chimera (termed EBE) used previously (Page et al. 1997); α1EbEEE substitutes only the I-II loop, whilst EBE exchanged both the 1S6 region and I-II loop.

α1EbEEEb and α1EEEEb

An Xho I site was removed from position 5433 of α1B using the forward primer, AAG TGC CCT GCA CGA GTC GCG TA and the reverse primer, GCA CTC GAG CGC GGA AGA TGA AGC. The product was extended on the α1B-pMT2 template using the forward primer, TTA CTC GAG ACT CTT CCA TCT TAG G, to introduce the Xho I site. This product was digested and subcloned into α1E(rbEII) to give α1EEEEb, and into α1EbEEE to give α1EbEEEb.

α1BbEEE and α1BbEEEb

A Mfe I (pMT2) to Kpn I α1B digestion was used to swap the first domain of α1EbEEE with that of α1B to make α1BbEEE. α1BbEEEb was made by using the same Kpn I site in α1EbEEEb.

PCR was carried out using the proof-reading enzyme, Pfu (Stratagene). The sequences of the sub-cloned PCR products were verified by cycle-sequencing using SequiTherm Excel™ II (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, USA).

Expression of constructs

COS-7 cells

Cells were transfected by electroporation as described (Campbell, Berrow, Brickley, Page, Wade & Dolphin, 1995). Fifteen, 5, 5 and 1 μg of the pMT2-α1, α2-δ, β2a or β1b and green fluorescent protein (GFP) constructs, respectively, were used for transfection. When used, Gβ1 and Gγ2 were included at 2.5 μg each. Cells were maintained at 37°C, then replated and maintained at 25°C prior to recording.

Xenopus oocytes

Adult Xenopus laevis females were anaesthetized by immersion in 0.2 % tricaine then killed by decapitation and pithing, oocytes were surgically removed and defolliculated with 2 mg ml−1 collagenase type Ia in a Ca2+-free ND96 saline (containing (mm): NaCl, 96; KCl, 2; MgCl2, 1; Hepes, 5; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH) for 2 h at 21°C. cDNAs for the different α1, β2a and α2-δ subunits and D2 receptors were co-injected at a ratio of 3:1:1: 3 into the nuclei of stage V and VI oocytes using a Drummond microinjector. Oocytes were incubated at 18°C for 3-7 days in ND96 saline (as above plus 1.8 mm CaCl2) supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 penicillin and 100 i.u. ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco) and 2.5 mm sodium pyruvate.

Electrophysiology

COS-7 cells

Recordings were made from fluorescent cells expressing the GFP reporter gene, replated between 1 and 16 h previously, using a non-enzymatic cell dissociation medium (Sigma). Borosilicate glass electrodes of resistance 2-4 MΩ were filled with a solution containing (mm): caesium aspartate, 140; EGTA, 5; MgCl2, 2; CaCl2, 0.1; K2ATP, 2; Hepes, 10; pH 7.2; osmolarity adjusted to 310 mosmol l−1 with sucrose. GDPβS (2 mm) was included where stated. The external solution contained (mm): tetraethylammonium (TEA) bromide, 160; KCl, 3; NaHCO3, 1.0; MgCl2, 1.0; Hepes, 10; glucose, 4; BaCl2, 1; pH 7.4; osmolarity adjusted to 320 mosmol l−1 with sucrose.

Whole cell currents were recorded using an Axopatch 1D amplifier. Data were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 5-10 kHz and analysed using pCLAMP6 and Origin 3.5. The junction potential between external and internal solutions was 6 mV, the values given in the figures and text have not been corrected for this. Current records are shown following leak and capacitance current subtraction (P/4 or P/8 protocol) and series resistance compensation up to 85 %.

Xenopus oocytes

Whole cell recordings from oocytes were made in the two-electrode voltage clamp configuration with a chloride-free solution containing (mm): Ba(OH)2, 40; TEA-OH, 50; KOH, 2; niflumic acid, 0.4; Hepes, 5; pH adjusted to 7.4 with methanesulphonic acid). In some experiments, niflumic acid was omitted and oocytes injected with 30-40 nl of 100 mm BAPTA to suppress endogenous chloride currents. Data were filtered at 1 kHz using a Geneclamp 500 amplifier, digitized th rough a Digidata 1200 interface (Axon Instruments) and stored using data acquisition software pCLAMP6. Currents were leak subtraction on line (P/4 protocol)

Experiments were performed at room temperature (20-24°C). Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's paired or unpaired t test as appropriate.

RESULTS

Effect of Gβ1γ2 co-expression on Ca2+ channel constructs

A series of chimeras between Ca2+ channel α1B and α1E(rbEII) subunits was constructed as shown in Fig. 1A to investigate the role of domain I, the I-II loop and the C-terminal in G protein regulation. α1 subunits were co-expressed together with accessory α2-δ and β2a subunits in COS-7 cells and modulation was studied by co-expressing Gβ1γ2 subunits. In controls, Gβ1γ2 was replaced by pMT2 vector and 2 mm GDPβS was included in the patch pipette to limit tonic facilitation (Stephens, Brice, Berrow & Dolphin, 1998). Current-voltage profiles were constructed (Fig. 1B) and the ability of co-expressed Gβ1γ2 subunits to slow current activation, a characteristic of G protein inhibition, was examined. Time constants of activation (τact) were derived from single exponential fits to the rising phase of currents (Fig. 1C). In the absence of exogenous Gβγ subunits, all currents activated rapidly and showed little inactivation over the time course used (as expected for co-expression of the β2a subunit which retards voltage-dependent inactivation of Ca2+ channels (Olcese et al. 1994)). In the presence of Gβ1γ2, α1B currents showed a marked slowing of activation kinetics in comparison to controls; in contrast, α1E(rbEII) currents showed no difference in activation with or without Gβ1γ2. Of the other constructs, those containing the N-terminal sequence/domain I/I-II loop of the α1B subunit sequence (α1B1-483) exhibited currents showing clear kinetic slowing in the presence of Gβ1γ2. Time constants of activation showed no significant differences for the effects of Gβ1γ2 on these responsive constructs: at -10 mV τact values were 32 ± 9 ms (α1B, n= 8), 29 ± 6 ms (α1BbEEE, n= 11) and 26 ± 5 ms (α1BbEEEb, n= 7). Thus, the subsequent exchange of the C-terminal, in addition to the α1B1-483 sequence, had no further effect on current activation kinetics.

Figure 1. Effect of Gβ1γ2 on Ca2+ channel constructs in COS-7 cells.

Ca2+ channel constructs between α1B and α1E(rbEII) subunits (as shown in A) were transfected together with cDNA coding for α2-δ and β2a subunits. B, example current density-voltage profiles for control cells (in the presence of GDPβS) and in the presence of Gβ1γ2. The initial test potential (Vt) shown was always -50 mV and was increased in 10 mV increments; holding potential VH= -100 mV. Values for scale bars on the left apply also to scale bars on the right. C, time constant of activation (τact) at -10 mV for Ca2+ channel constructs coexpressed with Gβ1γ2 (black columns) or in control conditions in the presence of GDPβS (open columns); number of experiments, n, is given in parentheses. Only currents resulting from constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence showed a clear slowing of activation kinetics.

Constructs in which either the I-II loop alone (α1EbEEE), the C-terminal sequence alone (α1EEEEb) or both elements (α1EbEEEb) were exchanged exhibited currents showing no significant slowing in activation kinetics in the presence of Gβ1γ2 (Fig. 1B and C).

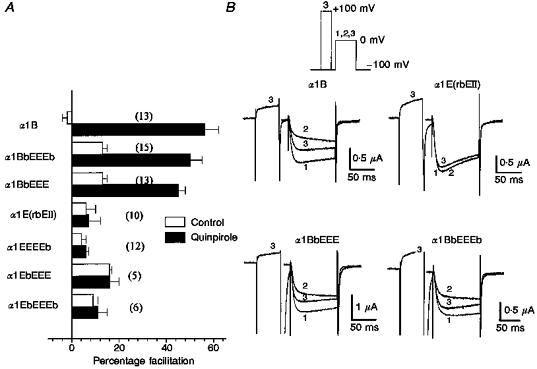

Receptor-mediated G protein inhibition of Ca2+ channel constructs

In parallel studies, we reconstructed receptor-mediated inhibition of constructs (together with α2-δ and β2a subunits) in Xenopus oocytes. Inhibitory coupling of dopamine (D2) receptors was assessed in terms of the reduction in current amplitude by a saturating concentration of quinpirole (100 nm) (Fig. 2A). Only constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence were modulated by receptor activation. There were no significant differences in inhibition by quinpirole amongst the responsive chimeras; however, quinpirole did cause a higher percentage inhibition in α1B than in α1BbEEE (P < 0.005) or α1BbEEEb (P < 0.005). No additional modulation to that seen in α1BbEEE was apparent in α1BbEEEb. Inhibition by quinpirole was absent in all of the other chimeras.

Figure 2. Effect of activation of D2 receptors on Ca2+ channel constructs in Xenopus oocytes.

Quinpirole-induced inhibition in constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence was accompanied by a depolarizing shift in the midpoint of activation (V½) of current-voltage curves (Fig. 2B). Modified Boltzmann functions fitted to the data shown gave similar shifts in V½ with quinpirole: α1B, +7.4 mV; α1BbEEE, +5.6 mV; α1BbEEEb, +6.5 mV. No such shift was seen for α1E(rbEII) (Fig. 2B).

Effects of facilitating prepulses on Gβ1γ2-induced inhibition on Ca2+ channel constructs

The voltage-dependent G protein modulation of Ca2+ channels can be reversed by the application of a large depolarizing prepulse prior to an activating pulse. Figure 3A illustrates that a depolarizing prepulse reversed both the inhibition of current amplitude and the slowed activation kinetics induced by Gβ1γ2 overexpression in COS cells expressing constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence. Gβ1γ2-induced slowing of activation kinetics was maximal at just supra-threshold potentials and was reversed by prepulses to the control levels observed in the presence of GDPβS (Fig. 3B). The degree of prepulse-induced current amplitude facilitation (P2 : P1) in the presence of Gβ1γ2 was also maximal over a similar voltage range in responsive constructs (Fig. 3C). No facilitation was observed in constructs lacking the first domain of α1B.

Figure 3. Reversal of Gβγ inhibition of Ca2+ channel constructs by large depolarizing prepulses in COS-7 cells.

Application of depolarizing prepulses reversed Gβ1γ2-induced inhibition, as shown for selected constructs. A, IBa (Vt= -40 to 0 mV) was examined immediately before (P1) and 10 ms after (P2) application of a depolarizing prepulse to +120 mV; VH= -100 mV. B, in constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence, prepulses (pp) reversed Gβ1γ2-induced slowing of activation kinetics to control levels (recorded separately at P1 in control cells). C, in constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence, prepulses reversed Gβ1γ2-induced inhibition of current amplitude (P2 : P1 measured at 50 ms). In all instances, note the lack of effects on α1E(rbEII). Number of experiments, n, is given in parentheses.

Prepulses also partially reversed the quinpirole-induced inhibition of current amplitude in constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence in oocytes (Fig. 4A and B). An incomplete reversal of inhibition by a large depolarizing prepulse is a characteristic of G protein inhibition and might be indicative of additional non-voltage-dependent mechanisms (Luebke & Dunlap, 1994) or due partially to the rebinding of Gβγ subunits during the 10 ms interpulse interval. Prepulses caused a significant facilitation of quinpirole-inhibited currents in comparison to control levels (prepulses applied in the absence of quinpirole) for responsive constructs (Fig. 4A). There was no clear difference in the percentage facilitation between responsive constructs. No facilitation was observed in constructs lacking the first domain of α1B.

Figure 4. Reversal of D2 receptor-induced inhibition of Ca2+ channel constructs by large depolarizing prepulses in Xenopus oocytes.

Application of depolarizing prepulses caused a reversal of quinpirole-induced inhibition of IBa for constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence. A, percentage facilitation of control (open columns) and quinpirole-inhibited IBa (black columns) induced by a prepulse to +100 mV. B, in constructs containing the α1B1-483 sequence, inhibition of control IBa (1) by quinpirole (2) was partially reversed by prepulse to +100 mV (3). In all cases, Vt= 0 mV and VH= -100 mV. Number of experiments, n, is given in parentheses.

Therefore, the transfer of the α1B1-483 sequence conferred full G protein modulation onto α1E(rbEII) which was reversed by depolarizing prepulses. No additional effects were seen with the subsequent exchange of the C-terminal sequence.

DISCUSSION

Taking clues from our previous studies and those of others, we constructed chimeric channels to study the role of several regions of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit implicated in G protein regulation. The data indicate that the α1B1-483 sequence, representing the N-terminal, domain I and the I-II loop, contain important determinants. In contrast, the data are not consistent with the I-II loop and/or the C-terminal alone forming a unique site for G protein modulation.

Role of the I-II loop in G protein inhibition

Despite data demonstrating binding of radiolabelled Gβγ to the Ca2+ channel I-II loop (De Waard et al. 1997; Zamponi et al. 1997; Qin et al. 1997), the functional importance of this site is still controversial (see Dolphin, 1998). Substitution of the I-II loop of α1C, which does not bind Gβγ (De Waard et al. 1997; Zamponi et al. 1997), into α1B (Zhang et al. 1996) or α1E (Qin et al. 1997) produces constructs that retain G protein sensitivity. However, opposite results have also been reported (Herlitze et al. 1997); conversion of the Gβγ-binding QxxER consensus sequence in the I-II loop of α1A subunit to the corresponding α1C sequence greatly reduced G protein inhibition. Importantly, this conversion did not completely abolish inhibition (Herlitze et al. 1997). Furthermore, whilst replacement of the I-II loop of α1A with that of α1B did increase G protein inhibition, it did not fully account for all of the inhibition seen in parental α1B (Zamponi et al. 1997). These findings suggest that molecular determinants for G protein modulation additional to the I-II loop are likely to exist. In support of this, we have demonstrated that a chimera in which the IS6/I-II loop of α1E(rbEII) was replaced by that of α1B (termed EBE) exhibited a greater slowing of current activation kinetics with GTPγS than did α1E(rbEII), but that GTPγS had no effects on current amplitude (Page et al. 1997).

In the present study, the α1EbEEE construct, in which only the I-II loop and not IS6 was exchanged, was examined. In agreement with our previous study, G proteins had no effect on current amplitude. However, no significant changes in activation kinetics were seen. In our previous study the β subunit used was β1b, which produces less antagonism of Gβγ than the β2a subunit used here (Qin et al. 1997). However, it appears that the additional substitution of the 1S6 region of transmembrane domain I, which has been implicated as a determinant of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel inactivation (Zhang, Ellinor, Aldrich & Tsien, 1994), can also subtly affect activation kinetics in the presence of Gβγ subunits.

Role of the intracellular C-terminal tail in G protein inhibition

The Ca2+ channel C-terminal has been implicated in G protein inhibition. Zhang et al. (1996) propose that both domain I and the C-terminal contribute elements to a multi-structural site, whilst Qin et al. (1997) suggest a unique site on the C-terminal. The thirty-eight amino acid Gβγ-binding site identified in the human α1E C-terminal sequence (Qin et al. 1997) is entirely conserved in α1E(rbEII). Despite the presence of this site, we saw no evidence of inhibition of α1E(rbEII). A possible explanation for this is that β subunits may compete for Gβγ binding and effectively block any modulation. More specifically, the β2a subunit presence here was shown selectively to block Gβγ binding to the human α1E C-terminal site (Qin et al. 1997). However, this is unlikely to explain the lack of G protein effects here as we also see no receptor-mediated inhibition of α1E(rbEII) in the absence of any exogenous β subunits (C. Cantí and A. C. Dolphin, unpublished results), suggesting an inherent G protein insensitivity of the α1E(rbEII) subunit.

The α1B1-483 sequence contributes to G protein inhibition

Transfer of the α1B1-483 sequence to α1E(rbEII) conferred G protein-induced slowing of current activation kinetics and reduction in current amplitude. In another major study on the determinants of G protein modulation, Zhang et al. (1996) proposed a role for domain I together with the C-terminal, but not the I-II loop. In contrast, we find that for α1E(rbEII), inhibition was not further increased by the subsequent exchange of the C-terminal in combination with the α1B1-483 sequence; this suggests that α1E(rbEII) lacks only molecular determinants within the α1B1-483 sequence. Despite these discrepancies, it is clear that domain I contains important determinants of G protein modulation. In this regard, the reduction in G protein inhibition caused by exchanging both domain I and the C terminal of α1B for these regions of α1C (Zhang et al. 1996) may be interpreted not as a lack of Gβγ binding to the α1B I-II loop, but rather a failure of binding to be fully translated into a functional effect due to the lack of the α1B domain I. Such an effect is consistent with the present results (as discussed below).

The α1B1-483 sequence represents the N-terminal, domain I and the I-II loop regions. The corresponding sequence of α1E(rbEII) shows only a few major regions of difference. The N-terminal shows the clearest difference, with the α1E(rbEII) N-terminal being fifty-five amino acids shorter than that of α1B. The involvement of the N-terminal region is currently under investigation. The entire 1S1-1S6 region shows a remarkable degree of homology (including complete conservation of the intracellular loops between IS2-IS3 and IS4-IS5); only the H5 linker between IS5 and IS6 in the putative pore region shows a clear divergence. However, this more likely reflects differences in pore properties such as ion permeation (Bourinet et al. 1996b) and single channel conductance (Dirksen, Nakai, Gonzalez, Imoto & Beam, 1997). Finally, the I-II loop shows sequence differences. However, as discussed previously (Page et al. 1997) and above, the I-II loop alone does not account for G protein inhibition.

Our findings suggest that the binding of Gβγ to either the I-II loop or the C-terminal alone is insufficient to mediate G protein inhibition. However, the data do not rule out a contribution of either region to a site composed of different elements capable of translating Gβγ binding into a functional effect. Whilst the I-II loop and/or the C-terminal may be the primary target for Gβγ binding, the functional changes which occur upon binding, both in terms of a slowing of current activation kinetics and a reduction in current amplitude, are mediated by important molecular determinants within the α1B1-483 sequence.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for generous gifts of cDNAs: Dr T. Snutch (UBC, Canada) for α1E(rbEII) and β1b; Dr H. Chin (NIH, USA) for α2-δ; Dr Y. Mori (Seiriken, Japan) for α1B; Dr E. Perez-Reyes (Loyola, USA) for β2a; Dr M. Simon (CalTech, USA) for Gβ1 and Gγ2; Professor P. G. Strange (Reading, UK) for D2 receptor; Dr T. Hughes (Yale University, USA) for Mut3-GFP; Genetics Institute (CA, USA) for pMT2. C. C. was a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia of Spain. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from The Wellcome Trust, and thank Ms A Odunlami, Mr I. Tedder, Ms M. Li and Ms J. May for technical assistance. This work benefited from the use of the Seqnet facility (Daresbury, UK).

References

- Bourinet E, Soong TW, Stea A, Snutch TP. Determinants of the G protein-dependent opioid modulation of neuronal calcium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996a;93:1486–1491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Zamponi GW, Stea A, Soong TW, Lewis BA, Jones LP, Yue DT, Snutch TP. The α1E calcium channel exhibits permeation properties similar to low-voltage-activated calcium channels. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996b;16:4983–4993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-04983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell V, Berrow N, Brickley K, Page K, Wade R, Dolphin AC. Voltage-dependent calcium channel β-subunits in combination with alpha1 subunits have a GTPase activating effect to promote hydrolysis of GTP by G alphao in rat frontal cortex. FEBS Letters. 1995;370:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00813-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, DeVivo M, Dingus J, Harry A, Li J, Sui J, Carty DJ, Blank JL, Exton JH, Stoffel RH, Inglese J, Lefkowitz RJ, Logothetis DE, Hildebrandt JD, Iyengar R. A region of adenylyl cyclase 2 critical for regulation by G protein beta gamma subunits. Science. 1995;268:1166–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.7761832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waard M, Liu H, Walker D, Scott VE, Gurnett CA, Campbell KP. Direct binding of G-protein βγ complex to voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature. 1997;385:446–450. doi: 10.1038/385446a0. 10.1038/385446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen RT, Nakai J, Gonzalez A, Imoto K, Beam KG. The S5-S6 linker of repeat I is a critical determinant of L-Type Ca2+ channel conductance. Biophysical Journal. 1997;73:1402–1409. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78172-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. Mechanisms of modulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels by G-proteins. Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.003bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Garcia DE, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Hockerman GH, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of inactivation and G protein modulation in the intracellular loop connecting domains I and II of the calcium channel α1A subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:1512–1516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1512. 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luebke JI, Dunlap K. Sensory neuron N-type calcium currents are inhibited by both voltage-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;428:499–507. doi: 10.1007/BF00374571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcese R, Qin N, Schneider T, Neely A, Wei X, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. The amino terminus of a calcium channel β subunit sets rates of channel inactivation independently of the subunit's effect on activation. Neuron. 1994;13:1433–1438. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page KM, Stephens GJ, Berrow NS, Dolphin AC. The intracellular loop between domains I and II of the B-type calcium channel confers aspects of G protein sensitivity to the E-type calcium channel. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:1330–1338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01330.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N Platano, Olcese R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Direct interaction of Gβγ with a C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit is responsible for channel inhibition by G protein-coupled receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:8866–8871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong TW, Stea A, Hodson CD, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP. Structure and functional expression of a member of the low voltage-activated calcium channel family. Science. 1993;260:1133–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.8388125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens GJ, Brice NL, Berrow NS, Dolphin AC. Facilitation of α1B calcium channels: involvement of endogenous Gβγ subunits. Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:15–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.015bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW, Bourinet E, Nelson D, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Crosstalk between G proteins and protein kinase C is mediated by the calcium channel α1 subunit I-II linker. Nature. 1997;385:442–446. doi: 10.1038/385442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J-F, Ellinor PT, Aldrich RW, Tsien RW. Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent inactivation in calcium channels. Nature. 1994;372:97–100. doi: 10.1038/372097a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J-F, Ellinor PT, Aldrich RW, Tsien RW. Multiple structural elements in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels support their inhibition by G proteins. Neuron. 1996;17:991–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]