Abstract

The functional properties of low-voltage-activated (LVA) Ca2+ channels were studied in pyramidal neurones from different rat visual cortical layers in order to investigate changes in their properties during early postnatal development. Ca2+ currents were recorded in brain slices using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique in rats from three age groups: 2, 3 and 12 days old (postnatal day (P) 2, P3 and P12).

It was demonstrated that LVA Ca2+ currents are present in neurones from superficial (I-II) and deep (V-VI) visual cortex layers of P2 and P3 rats. No LVA Ca2+ currents were observed in neurones from the middle (III-IV) layers of these rats. The LVA Ca2+ currents observed in P2 and P3 neurones from both superficial and deep layers could be completely blocked by nifedipine (100 μM) and were insensitive to Ni2+ (25 μM).

The density of LVA Ca2+ currents decreased rapidly during the early stages of postnatal development, while the density of high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents progressively increased up to the twelfth postnatal day. No LVA Ca2+ currents were found in P12 neurones from any of the layers. Only HVA Ca2+ currents with high sensitivity to F− applied through the patch pipette were observed.

The kinetics of LVA Ca2+ currents could be well approximated by the m2h Hodgkin-Huxley equation with an inactivation time constant of 24 ± 6 ms. The steady-state inactivation curve fitted by a Boltzmann function had the following parameters: membrane potential at half-inactivation, -86.9 mV; steepness coefficient,3.4 mV.

It is concluded that, in visual cortical neurones, LVA Ca2+ channels are expressed only in the neurones of deep and superficial layers over a short period during the earliest postnatal stages. These channels are nifedipine sensitive and similar in functional properties to those in the laterodorsal (LD) thalamic nucleus. However, the cortical neurones do not express another (‘slow’) type of LVA Ca2+ channel, which is permanently present in LD thalamic neurones after the second postnatal week, indicating that the developmental time course of cortical and thalamic cellsdifferent.

The functional properties of nerve cells in different parts of the nervous system are determined by the specificity of their morphological structure as well as by the composition of their voltage- and receptor-operated ion channels. The expression of channel proteins is extremely variable in different neurones and highly dependent on the developmental stage of the animal (Thompson & Wong, 1991; Fedulova, Kostyuk & Veselovsky, 1994). Some of these proteins appear only for a short period, being responsible for triggering the differentiation of neuronal precursors and the establishment and maturation of neuronal connections, while others form a constant basis for the activity of neuronal networks. Analysis of the expression and functioning of voltage-operated Ca2+ channels (VOCCs) is especially important for the understanding of these processes, as Ca2+ ions are known to play a critical role in the formation of the nervous system (Al-Mohanna, Cave & Bolsover, 1992; Amato, Al-Mohanna & Bolsover, 1996), and to be the main messengers in synaptic transmission at all neuronal junctions. Of especial interest in this respect is the presence of low-voltage-activated (LVA) Ca2+ channels, which can be activated at voltages close to the membrane resting potential provided that their steady-state inactivation is removed by some preceding hyperpolarizing influences, and which can therefore easily generate the spontaneous Ca2+ transients necessary for morphogenesis. At present, data on the development of expression of such channels in different neurones are extremely variable. Thus, during artificially induced differentiation in neuronal tumour cell lines, only LVA Ca2+ channels appear at the start of differentiation, and then decrease as other types of ion channels are expressed (Veselovsky & Fomina, 1986). In rat and mouse dorsal root ganglion neurones LVA (T-type) Ca2+ channels show a peak of expression just around the time of birth, while later on their density starts to decline until their complete disappearance in most neurones beyond the first few weeks (Fedulova, Kostyuk & Veselovsky, 1986; Fedulova et al. 1994). In cultured Xenopus sensory neurones they are expressed only during the first 20-40 h of culture (Barish, 1991). The same is true for neurones cultured from adult or embryonic rat and guinea-pig hippocampal pyramidal neurones (O'Dell & Alger, 1991; Thompson & Wong, 1991) and rat neostriatum (Bargas, Surmeier & Kitai, 1991). In contrast to this, however, LVA Ca2+ channels are the predominant type of VOCC in certain thalamic and hypothalamic neurones and are a constant feature of the excitability mechanism, playing an important role in the organization of slow rhythmic activity (Akaike, Kostyuk & Osipchuk, 1989; Huguenard & Prince, 1992). The developmental appearance of such channels is quite complicated. Thus, the population of LVA Ca2+ channels in neurones of the rat laterodorsal (LD) thalamic nucleus was found to be homogeneous in kinetic and pharmacological properties only during the first postnatal week. The corresponding Ca2+ currents demonstrated fast inactivation kinetics with a monoexponential time course (∼30 ms) and high sensitivity to nifedipine (Kd= 2.6 μM). However, from the second postnatal week onwards, a more slowly inactivating component appeared in LVA Ca2+ currents from the same neurones, which showed insensitivity to nifedipine but high sensitivity to Ni2+ (Tarasenko, Kostyuk, Eremin & Isaev, 1997). The two types of LVA Ca2+ channel are probably associated with different neuronal functions, as the appearance of the ‘slow’ channels (with an inactivation time constant of ∼60 ms) coincided with development of the dendritic tree in the corresponding cells.

These findings stimulated us to analyse in more detail the kinetic, pharmacological and developmental properties of LVA Ca2+ channels in neocortical neurones closely connected functionally to the neuronal activity of associative thalamic nuclei. The presence of LVA Ca2+ currents has been reported in pyramidal neurones in slices from the rat visual cortex (Franz, Galvan & Constanti, 1986; Sutor & Zieglgansberger, 1987) and in pyramidal neurones acutely isolated from the rat sensorimotor cortex (Sayer, Schwindt & Crill, 1990). However, the properties of these channels have not as yet been fully characterized. The cellular heterogeneity of the cortex and the difficulty of identifying specific cell types has substantially limited the study of characteristics and developmental changes. This complexity is evident from a recent study of pyramidal neurones from guinea-pig medial frontal cortex, which found that only cells located lower than 500 μm from the pial surface (approximately layers V-VI) were able to generate LVA Ca2+ currents and low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (LTS) (De la Pena & Geijo-Barrientos, 1996).

In the present study we attempted to investigate this problem further by using neurones from different layers of the rat visual cortex during the first 12 days of postnatal development.

METHODS

Slice preparation

Brain slices were obtained from Wistar rats of three age groups: 2, 3 and 12 days old (postnatal day (P) 2, P3 and P12, the day of birth being designated as P1). The procedure to obtain brain slices was similar to that previously described by Tarasenko et al. (1997). Animals were anaesthetized with ether and decapitated only after observation of deep sleep. Incubation time in the recovery solution depended on the age of the animal: P2 and P12 slices were incubated for 30 and 60 min, respectively. Slices were 300 μm thick.

Patch-clamp recordings

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed as reported previously (Tarasenko et al. 1997). Patch pipettes were pulled from thick-walled molybdenum glass capillaries, and had 3-6 MΩ resistance for P2 and P3 cortical neurones and 2-4 MΩ resistance for P12 neurones. The inner diameters of the pipettes varied from 1 to 3.5 μm depending on the size of the cell studied.

Taking into account variations in membrane surface properties and cell morphology in the different cortical layers and postnatal developmental stages, we controlled both the membrane capacitance and input resistance of the neurones. The membrane capacitance was calculated by subtracting the pipette electrode capacitance from the whole-cell capacitance, which in turn was estimated from the integral of the corresponding transient current induced from a holding potential of -80 mV by 10 mV hyperpolarizing pulses after rupture of the cell membrane. Generally, these transients had fast monoexponential time decay and could therefore be treated as a single monoexponential unit (Kay & Wong, 1987) and accepted for analysis. In addition, only those cells that completely satisfied all the criteria of voltage-clamp control formulated in our previous work (Tarasenko et al. 1997) were included for further study. We could not compensate the series resistance (Rs) but determined it from the amplitude or time constant of the capacitive current after rupture of the membrane. As the amplitude of Ca2+ currents did not exceed 200 pA and Rs was no more than 15 MΩ, the error in voltage clamp was less than 3 mV.

Input resistance was evaluated by dividing the voltage step by the leakage current. After rupture of the cell membrane the leakage currents were compensated by using an additional electrical circuit throughout the recording session. The compensation procedure was considered as satisfactory if the current trace elicited at the onset of a 10 mV hyperpolarizing command potential from the holding potential coincided with the zero line.

For observation of the upper surface of the slice we used an upright microscope (Ergoval; Carl Zeiss) with a × 3.2 Semiplan objective lens fitted with a calibrated eyepiece. Visual cortex (areas 17 and 18) was identified according to the rat brain stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos & Watson, 1982); a × 20 Leitz Wetzlar objective lens was used to identify the type of cortical cell and the particular cortical layer. The cell surface was thoroughly cleaned before seal formation by saline streamed from a neighbouring pipette. Ca2+ currents were isolated by blocking Na+ and K+ channels and by replacing intracellular K+ with Cs+ (see Solutions and Drugs, below). Currents were recorded at room temperature (19-22°C) using an analogue of the List EPC-5 patch-clamp amplifier at an output cut-off frequency of 1 kHz (-3 dB, 8-pole active Bessel filter). Ca2+ currents were elicited by a series of increasing depolarizing steps every 5-7 s, digitally sampled at 8 μs intervals, stored and analysed with an IBM PC-compatible computer. The current amplitude was measured as the difference between peak inward current and zero current. Other specific protocols are described in the text or figure legends. Graphing and curve fitting was performed by SigmaPlot 5.0 (Jandel Scientific GmbH, Erkath, Germany). Time constants and current kinetics were described by fitting with a Hodgkin-Huxley model, using methods identical to those described earlier (Coulter, Huguenard & Prince, 1989). Results are given as means ±s.e.m. and the number of observations is indicated in parentheses.

Solutions and drugs

The solution for slice cutting and recovery contained (mM): NaCl, 125; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1; NaHCO3, 24; NaH2PO4, 1.25; glucose, 25. To maintain the solution at pH 7.4 it was continuously bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2.

The extracellular recording solution contained (mM): choline chloride, 113; TEA-Cl, 27; Tris-Cl, 20; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 0.5 and tetrodotoxin (TTX), 1 μM; pH adjusted to 7.4 with Tris-OH.

The pipette solution contained (mM): CsCl, 130; EGTA, 10; TrisCl, 10; MgCl2, 5; CaCl2, 1; pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH.

The presence of TEA-Cl in the extracellular solution and CsCl in the pipette solution enabled us to block potassium channels completely during recording. To block sodium channels, TTX was added to the extracellular solution and Na+ was replaced with choline chloride.

To study the pharmacological properties of LVA Ca2+ channels, the following substances were used: nifedipine (Sigma), made as a 50 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulphoxide; and Ni2+, dissolved in extracellular recording solution to the final concentrations indicated in Results. Ni2+ was added to the extracellular solution as NiCl2. All drugs were applied by a fast-application technique through a pressure-ejecting micropipette (tip diameter, 40-50 μm).

RESULTS

Passive properties of visual cortical neurones

The results presented were obtained in neurones located in different layers below the external surface of the cortex. As described in Methods, the membrane capacitance was evaluated as the integral of the capacitive transient obtained in response to hyperpolarizing command pulses of 10 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV. In P2 rat neurones from deep layers the membrane capacitance was 23 ± 4 pF (n= 8). However, in P3 and P12 rats the population of cortical neurones was observed to be heterogeneous. Two groups of cells were identified. The neurones of the first group appeared to be in the process of increasing their dendritic tree, as their cell capacitances were 36 ± 5 pF (n= 10) and 76 ± 12 pF (n= 12) for ages P3 and P12, respectively (Fig. 1). The neurones of the second group did not appear to be undergoing changes in their cellular membrane surfaces as their capacitances were 24 ± 4 pF (n= 9) and 24 ± 6 pF (n= 7) for P3 and P12 cells, respectively; these cells probably corresponded to non-pyramidal neurones and were not included in any further analysis.

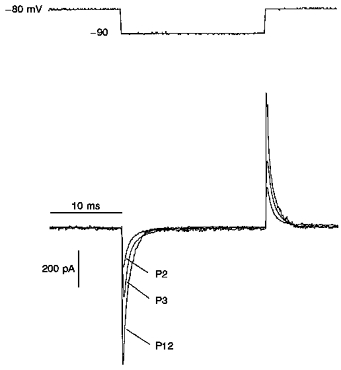

Figure 1. Passive properties of visual cortical pyramidal neurones.

Developmental changes in capacitance of pyramidal neurones from deep layers of the visual cortex. The transient capacitive current was evoked by a 10 mV hyperpolarizing command potential from a holding potential of -80 mV. Constant leakage current for the neurones shown here was 5, 10 and 12 pA for P2, P3 and P12, respectively. The calculated values of membrane capacitance were 29, 46 and 68 pF for P2, P3 and P12, respectively. The decay of the capacitive current was fitted by a single exponential curve with time constants of 0.52, 0.64 and 0.41 ms for P2, P3 and P12 neurones, respectively.

The situation was different for the neurones of layers I-II. We did not find any substantial developmental changes in the membrane capacitance of these neurones. Membrane capacitance was 52 ± 11 pF (n= 15), regardless of postnatal stage.

The decay in the capacitive transients of the cells (measured after rupturing the cell membrane) could be fitted by a single exponential curve. The time constant of decay (τ) varied, depending on the age group, from 140 μs to 1.2 ms. The series resistance determined from the capacitive transients did not exceed 15 MΩ for those neurones tested.

No age-related differences in leakage currents were observed. As a rule, the leakage current was ∼20 pA and no greater than 27 pA. The mean input resistance of tested cells was 500 MΩ.

Developmental changes in Ca2+ conductance in cortical neurones from different layers

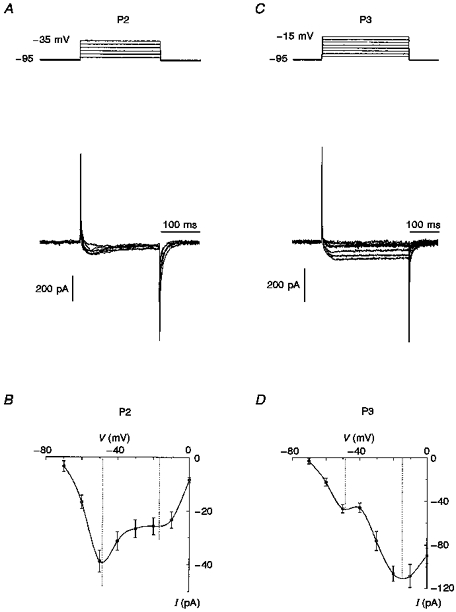

Typical records of Ca2+ currents in P2 and P3 neurones from deep layers are shown in Fig. 2. Generally, in P2 neurones, predominantly transient Ca2+ currents evoked by step depolarization to -55 mV from a holding potential of -95 mV could be observed. A sustained current may also have been revealed at depolarization potentials more positive than -45 mV but its mean value was significantly less than that of the transient current (Fig. 2A). The current-voltage (I-V) relationship had two maxima at about -50 and -15 mV, indicating the presence of both LVA and high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ currents (Fig. 2B). The amplitude of Ca2+ current induced by step depolarization to -50 mV was 38 ± 6 pA (n= 8). In P3 neurones under the same conditions, it was also possible to observe the LVA Ca2+ current (Fig. 2C). The I-V curve again had two characteristic peaks around -50 and -15 mV (Fig. 2D). However, the amplitude of HVA Ca2+ current was 108 ± 12 pA, and it became predominant. There were no LVA Ca2+ currents in P12 neurones over a depolarization range between -75 and -45 mV (Fig. 3A) and the I-V curve had only one peak around -15 mV. The maximum amplitude of HVA Ca2+ current was 738 ± 64 pA (n= 7). To verify that P12 neurones expressed only HVA Ca2+ channels, 5 μM F− was added to the pipette solution to block HVA Ca2+ currents from the inside (Fig. 3B), a method previously used in isolated thalamic neurones (Bertollini, Biella, Wanke, Avanzini & De Curtis, 1994). As LVA Ca2+ current persisted in the presence of intracellular F− (Carbone & Lux, 1987; Fraser & MacVicar, 1991), the I-V relationship could be expected to have two peaks if LVA Ca2+ currents were present. The blocking effect of F− was 90 ± 5 % (n= 12) and in the presence of this anion the I-V curve had only one peak at about -15 mV (Fig. 3C).

Figure 2. Changes in whole-cell Ca2+ current during the earliest stages of postnatal development.

A and C, depolarizing voltage steps from a holding potential of -95 mV for P2 (A) and P3 (C) neurones from layers V-VI evoked the superposition of transient LVA Ca2+ current and slowly inactivating HVA Ca2+ currents, the latter of which was predominant in P3 (C) neurones. The voltage protocol for each panel is shown at the top. B and D, I-V relationships of peak currents for neurones of the two age groups are presented beneath the current traces. The I-V relationships for neurones of both P2 and P3 age groups have 2 peaks, at about -50 and -15 mV, corresponding to LVA and HVA Ca2+ currents, respectively. For construction of the I-V curves data were averaged using 5 cells for P2 and 8 cells for P3 neurones.

Figure 3. Ca2+ currents in P12 neurones.

A, typical records of Ca2+ current in P12 neurones obtained by membrane depolarization from -95 mV in 10 mV steps. There were no transient Ca2+ currents in the region from -70 to -40 mV. The threshold for activation of Ca2+ currents was about -45 mV. The voltage step protocol is shown at the top. B, Ca2+ currents in the presence of 5 μM F− after a short period (5 min) of intracellular perfusion. Fluoride ions were added to verify whether the LVA Ca2+ current is present in P12 neurones and hidden by the larger HVA Ca2+ current. In general, in the presence of F− ions, 90 ± 5 % of the Ca2+ current was blocked and no LVA current was found. C, I-V relationships of peak currents registered in the absence and presence of F− have only one peak at about -15 mV, corresponding to HVA Ca2+ current.

As it turned out, the expression of LVA Ca2+ channels was not a property common to all visual cortical neurones in the earliest stages of postnatal development. There were no LVA Ca2+ currents in neurones from the middle layer (III-IV) on either the second or twelfth postnatal days. However, the developmental changes in neurones from the superficial layer (I-II) had exactly the same time course as those of neurones in the deeper layer (V-VI). LVA Ca2+ currents were present in P2 and P3 neurones, but only HVA Ca2+ currents were recorded in P12 neurones. To clarify the question as to whether the neurones from deep and superficial layers expressed the same LVA Ca2+ channels, a special pharmacological and kinetic study of LVA Ca2+ currents in neurones from different layers was undertaken.

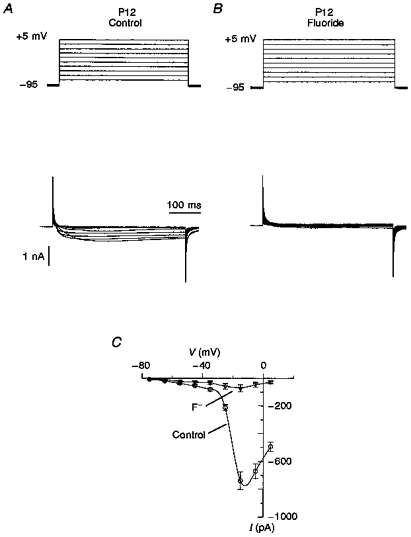

Pharmacological properties of LVA Ca2+ current

As we have shown previously (Tarasenko et al. 1997), LD thalamic neurones can express two types of LVA Ca2+ channels with different sensitivities to nifedipine and Ni2+. In the present study we found that neurones from both deep and superficial layers had LVA Ca2+ currents with high sensitivity to nifedipine (Fig. 4A). The nifedipine-sensitive component was obtained as the difference between the control current and the current obtained after blocking by nifedipine (100 μM). The amplitude of nifedipine-sensitive current in P2 deep neurones (Fig. 4B) was larger (22 ± 4 pA, n= 6) than that in P3 neurones (12 ± 4, n= 8) The same postnatal changes in amplitude of LVA Ca2+ currents were observed in neurones from the superficial layer. To determine whether any other component was present in the LVA Ca2+ current, Ni2+ at 25 μM was applied to the neurones tested. No changes were observed in the control Ca2+ current in either deep (n= 5) or superficial neurones (n= 7).

Figure 4. Blocking effect of nifedipine on LVA Ca2+ current in P2 visual cortical neurones.

A, LVA Ca2+ current recorded in P2 neurones before (Control) and after blocking by 100 μM nifedipine. The current was obtained by 35 mV step depolarization from a holding potential of -95 mV (top). B, the nifedipine-sensitive component was obtained by subtracting LVA Ca2+ current after blocking by 100 μM nifedipine from the control LVA Ca2+ current. It was fitted in terms of the m2h model (continuous line) with the inactivation time constant (τh) indicated.

Steady-state inactivation of the LVA Ca2+ current

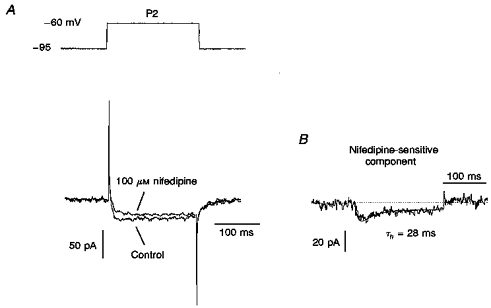

Taking into account the specificity of steady-state inactivation of the slow LVA Ca2+ current component in LD neurones (half-inactivation membrane potential (V0.5), ∼-100 mV; Tarasenko et al. 1997), in the next part of our study a special protocol for recording Ca2+ currents was used. A membrane depolarization to -50 mV followed a hyperpolarization prepulse in the range -90 to -120 mV of 500 ms duration. There was no difference in the amplitude of LVA Ca2+ currents between neurones from the two (superficial and deep) layers, demonstrating the presence of the same type of LVA channel. The recordings of LVA Ca2+ currents made using this protocol are shown in Fig. 5A. The inactivation time constant for LVA Ca2+ current was the same using this protocol as when using the normal protocol (see above), at 23 ± 4 ms (n= 4). This fact led us to conclude that visual cortical neurones do not express slowly inactivating LVA Ca2+ channels after the second postnatal week, although they are permanently present in LD thalamic neurones (Tarasenko et al. 1997). The normalized peak amplitudes of the evoked currents could be fitted by a Boltzmann function (Fig. 5B). The V0.5 of -86.9 mV and slope factor (k) of 3.4 mV were similar to those described in LD thalamic neurones for the ‘fast’ component (IT,f) of the LVA Ca2+ current.

Figure 5. Steady-state inactivation of LVA Ca2+ current in P2 neurones.

A, voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation of the nifedipine-sensitive LVA Ca2+ current. The voltage protocol is shown at the top. The membrane was depolarized to -50 mV from different holding potentials between -105 and -75 mV. The duration of the prepulse impulse was 500 ms. B, the inactivation curve fitted by a Boltzmann equation (I/Imax=[1 + exp(V - V0.5/k)]−1, where I is the current amplitude, Imax is the maximum current amplitude, V is the voltage, V0.5 is the half-inactivation voltage and k is the slope factor) with V0.5= -86.9 mV and k= 3.4 mV (n= 7).

Kinetic properties of the LVA Ca2+ current

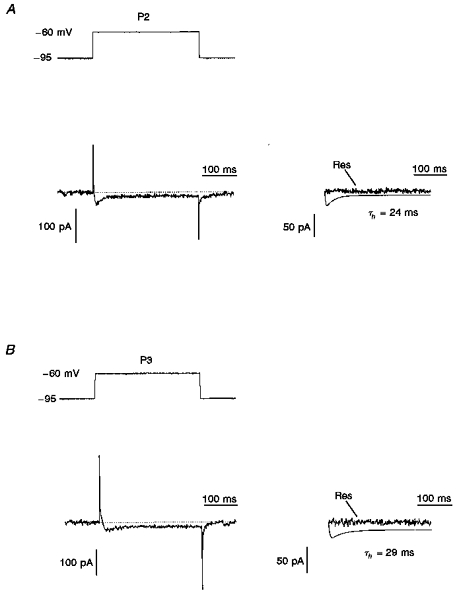

The LVA Ca2+ current induced by membrane depolarization to -60 mV from a prepulse potential of -95 mV showed monoexponential decay and declined completely in about 100 ms in both P2 and P3 neurones. Analysis of the activation and inactivation time courses of this current indicated that it could be well fitted in terms of the m2h Hodgkin-Huxley equation, as has already been shown for the kinetics of other types of Ca2+ currents (Kostyuk, Krishtal, Pidoplichko & Shakhovalov, 1979; Kay & Wong, 1987). The equation used for fitting the LVA Ca2+ current (ICa) was:

| (1) |

where t is time, τm and τh are the activation and inactivation time constants, respectively, I∞ is a sustained Ca2+ current, and A is an amplitude scaling factor. The fitting parameters for the LVA Ca2+ current in P2 neurones (Fig. 6A) were τm= 3.6 ± 0.5 ms and τh= 24 ± 6 ms (n= 15). No differences were observed between the LVA Ca2+ current kinetics of P3 and P2 neurones. For P3 neurones the time constants were τm= 4.2 ± 0.6 ms and τh= 26 ± 5 ms (n= 14) for activation and inactivation, respectively (Fig. 6B). Since the pharmacological sensitivity and kinetics of the LVA current in cells from both age groups did not show significant differences (P > 0.1), we concluded that these neurones express nifedipine-sensitive LVA Ca2+ channels similar to ‘fast’ channels expressed in P12 LD neurones.

Figure 6. Inactivation kinetics of LVA Ca2+ currents in P2 and P3 visual cortical neurones.

A and B (left), a transient LVA Ca2+ current in P2 (A) and P3 (B) deep layer neurones activated by depolarization to -60 mV from a prepulse potential of -95 mV. A and B (right), the current traces were fitted by computer simulation using the m2h equation with the inactivation time constants (τh) indicated. The residue (Res) current was obtained by subtraction of the simulated current from the LVA Ca2+ current (control).

Postnatal changes in densities of Ca2+ current

According to our estimation, the current density for LVA currents in P2 neurones was 1.65 ± 0.17 pA pF−1 (n= 6) and for HVA currents it was 1.08 ± 0.13 pA pF−1 (n= 8); current density did not depend upon whether the neurone was situated in the deep or the superficial layer. However, already by the third postnatal day (P3), the relative proportion of LVA to HVA Ca2+ currents had substantially changed. The density of LVA Ca2+ current (1.34 ± 0.12 pA pF−1, n= 6) in P3 neurones became smaller compared with that of neurones of the first age group, P1 (P < 0.01). On the other hand, the density of slowly inactivating HVA Ca2+ current in P3 neurones became significantly greater than in P2 neurones and reached 3.08 ± 0.31 pA pF−1 (n= 6). By the twelfth postnatal day the density of HVA Ca2+ current had increased considerably compared with P2 and P3 neurones, reaching 9.7 ± 0.7 pA pF−1 (n= 12).

DISCUSSION

Using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique combined with the direct visualization of neurones during recording in brain slice preparations, we studied the early postnatal development of the electrophysiological properties of pyramidal and non-pyramidal neurones of rat visual cortex. Special attention has been paid to LVA Ca2+ currents because of the multiple roles these currents play in the functioning of different neurones (short-lasting currents that trigger neuronal morphogenesis and continuous currents that are responsible for special forms of neuronal activity) as well as the recently established existence of several kinetically and pharmacologically different subtypes of the corresponding LVA Ca2+ channels (Tarasenko et al. 1997).

The present study has demonstrated that LVA Ca2+ channels are expressed in the visual cortex only in pyramidal neurones of deep (V-VI) and superficial (I-II) layers for a very short period during the earliest stages of postnatal development. HVA Ca2+ channels are expressed in these neurones at this developmental time at a much lower density. Obviously, the LVA channels immediately after birth are the main gates for intracellular Ca2+ entry. These channels are, by their kinetic and pharmacological properties, analogous to those previously described by us as ‘fast’ LVA Ca2+ channels in the LD thalamic neurones, indicating that in both cases the function of these channels may be similar, i.e. triggering neuronal differentiation and establishing neuronal connections. However, the time characteristics of the expression of these channels in neocortical and thalamic neurones are substantially different. In cortical neurones, by as early as the third postnatal day the density of LVA currents decreased while that of HVA currents increased. At the twelth day after birth we could not observe any LVA Ca2+ current in neurones from either layers I-II and V-VI; in thalamic neurones at this developmental time the ‘fast’ component was still well expressed (Tarasenko et al. 1997). One may speculate that the development of thalamic projections is a much more time-consuming process and demands the longer-lasting triggering action of intracellular Ca2+ transients provided by the activity of LVA Ca2+ channels. During neocortical development this process may go faster. In this respect it should be mentioned that LVA Ca2+ channels disappeared simultaneously in the superficial and deep cortical layer neurones; during neocortical development the interaction between neurones of layer I-II (Cajal-Retzius cells) and layer V-VI is extremely important for the correct positioning of migrating neurones and their maturation (Ogawa et al. 1995).

In the middle layer (II-III) neurones, only HVA Ca2+ currents were found even on days P2 and P3. One day later, the pyramidal neurones from both the deep and superficial layers also started to express a substantial number of HVA Ca2+ channels. It has been shown previously that in guinea-pig medial frontal cortex only pyramidal neurones are able to generate low-threshold Ca2+ spikes; they were rarely observed in layers II-III and frequently in layers V-VI (De la Pena & Geijo-Barrientos, 1996). This may indicate that neurones in the middle layers differentiate very early on and achieve maturity even before birth, while those in the superficial and deep layers still have immature membrane properties during the postnatal period and continue to develop over the first two postnatal weeks (Zhou & Hablitz, 1996).

In contrast to neocortical neurones, neurones of certain thalamic and hypothalamic structures maintain a high density of LVA Ca2+ channels in the adult state (Akaike et al. 1989; Huguenard & Prince, 1992). Obviously, besides contributing in some way to neuronal differentiation and the establishment of synaptic contacts, these channels are important for generating specific types of neuronal activity in the form of membrane potential oscillations and repetitive firing, enabling thalamic neurones to act as pacemaker elements in thalamocortical circuits (Dossi, Nuñez & Steriade, 1992; Huguenard & Prince, 1992; Kang & Kitai, 1993; Hutcheon, Miura, Yarom & Puil, 1994). The observed differences clearly indicate a leading role for subcortical structures in the generation and maintenance of the corresponding rhythms. The Ca2+ channels responsible for such activity evidently form a special subtype of LVA channel, differing from the transient subtype in inactivation kinetics, location and pharmacology. As has already been stated, in LD thalamic neurones these channels seem to be located mainly on dendrites; in accord with this location, the thalamocortical rhythmic activity in rats starts just after maturation of the dendritic tree of the thalamic neurones (Muller, Misgeld & Swandulla, 1992; Karst, Joels & Wadman, 1993).

The pharmacological specificity of the permanent LVA Ca2+ channels in thalamic neurones merits special attention. A more extensive evaluation of possible specific antagonists to this type of channel may produce drugs that could attenuate paroxysmal thalamocortical activity without affecting the normal course of postnatal development of the corresponding structures.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Government of Ukraine and the US Civilian Research and Development Foundation for the Independent States of the Former Soviet Union (CRDF) by grant no. UBI-318.

References

- Akaike N, Kostyuk PG, Osipchuk YV. Dihydropyridine-sensitive low-threshold calcium channels in isolated rat hypothalamic neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;412:181–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohanna FA, Cave J, Bolsover SR. A narrow window of intracellular calcium concentration is optimal for neurite outgrowth in rat sensory neurones. Developmental Brain Research. 1992;70:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90209-f. 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90209-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato A, Al-Mohanna FA, Bolsover SR. Spatial organization of calcium dynamics in growth cones of sensory neurones. Developmental Brain Research. 1996;92:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00211-1. 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargas J, Surmeier DJ, Kitai ST. High- and low-voltage activated calcium currents are expressed by rat neostriatal neurones. Brain Research. 1991;541:70–74. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91075-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barish ME. Voltage-gated calcium currents in cultured embryonic Xenopus spinal neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;444:523–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertollini L, Biella G, Wanke E, Avanzini G, De Curtis M. Fluoride reversibly blocks HVA calcium current in mammalian thalamic neurones. NeuroReport. 1994;5:553–556. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E, Lux HD. Kinetics and selectivity of a low-voltage-activated calcium current in chick and rat sensory neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;386:547–570. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter DA, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Calcium currents in rat thalamocortical relay neurones: kinetic properties of the transient, low-threshold current. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;414:587–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Pena E, Geijo-Barrientos E. Laminar localization, morphology, and physiological properties of pyramidal neurons that have a low-threshold calcium current in the guinea-pig medial frontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5301–5311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05301.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossi RC, Nuñez A, Steriade M. Electrophysiology of slow (0.5–4 Hz) intrinsic oscillations of cat thalamocortical neurones in vivo. Journal of Physiology. 1992;447:215–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedulova SA, Kostyuk PG, Veselovsky NS. Changes in ion mechanisms of membrane electroexcitation in rat sensory neurones during ontogenesis. Proportion of inward current densities. Neurophysiology. 1986;18:820–827. [Google Scholar]

- Fedulova SA, Kostyuk PG, Veselovsky NS. Comparative analysis of ionic currents in the somatic membrane of embryonic and newborn rat sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 1994;58:341–346. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90040-x. 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90040-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz P, Galvan M, Constanti A. Calcium-dependent action potentials and associated inward currents in guinea-pig neocortical neurons in vivo. Brain Research. 1986;366:262–271. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91303-x. 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91303-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DD, MacVicar BA. Low-threshold transient calcium current in rat hippocampal lacunosum-moleculare interneurons: kinetics and modulation by neurotransmitters. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:2812–2820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02812.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JR, Prince DA. A novel T-type current underlies prolonged Ca2+-dependent burst firing in GABAergic neurons of rat thalamic reticular nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:3804–3817. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03804.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon B, Miura RM, Yarom Y, Puil E. Low-threshold calcium current and resonance in thalamic neurons: a model of frequency preference. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:583–594. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Kitai ST. A whole cell patch-clamp study on the pacemaker potential in dopaminergic neurons of rat substantia nigra compacta. Neuroscience Research. 1993;18:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(93)90056-v. 10.1016/0168-0102(93)90056-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst H, Joels M, Wadman WJ. Low-threshold calcium current in dendrites of the adult rat hippocampus. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;164:154–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90880-t. 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90880-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR, Wong RKS. Calcium current activation kinetics in isolated pyramidal neurones of the CA1 region of the mature guinea-pig hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;392:603–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyuk PG, Krishtal OA, Pidoplichko VI, Shakhovalov YA. Kinetics of calcium inward current activation. Journal of General Physiology. 1979;73:675–677. doi: 10.1085/jgp.73.5.675. 10.1085/jgp.73.5.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller TH, Misgeld U, Swandulla D. Ionic currents in cultured rat hypothalamic neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:341–362. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dell TJ, Alger BE. Single calcium channels in rat and guinea-pig hippocampal neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;436:739–767. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, Yagyu K, Seike M, Ikenaka K, Yamamoto H, Mikoshiba K. The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:899–912. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Australia: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer RJ, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. High- and low-threshold calcium currents in neurons acutely isolated from rat sensorimotor cortex. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;120:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90031-4. 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutor B, Zieglgansberger W. A low-voltage activated, transient calcium current is responsible for the time-dependent depolarizing inward rectification of rat neocortical neurons in vivo. Pflügers Archiv. 1987;410:102–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00581902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasenko AN, Kostyuk PG, Eremin AV, Isaev DS. Two types of low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in neurones of rat laterodorsal thalamic nucleus. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:77–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SM, Wong RK. Development of calcium current subtypes in isolated rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;439:671–689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veselovsky NS, Fomina AF. Investigation of sodium and calcium channels of somatic membrane in neuroblastoma cells during artificial induced differentiation. Neurophysiology. 1986;18:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Hablitz JJ. Postnatal development of membrane properties of layer I in rat neocortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:1131–1139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01131.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]