Abstract

We have studied the effects of mutations of amino acids in the pore (positions 447 and 449) and the elevation of extracellular [K+] on the closing and opening kinetics of Shaker B K+ channels transiently expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.

Mutant D447E had closing and C-type inactivation kinetics which were faster than the wild-type channel. These processes were slowed by increasing extracellular [K+] and in these conditions the channels exhibited linear instantaneous current-voltage relationships. Thus, the mutation seems to produce uniform decrease of occupancy by K+ in sites along the channel pore where the cation competes with closing and C-type inactivation.

In other mutants also showing K+-dependent fast C-type inactivation, closing was found to be slower than in the wild-type channel and insensitive to variations in external [K+]. These characteristics were particularly apparent in mutant T449K which even in high [K+] has a non-linear instantaneous current-voltage relationship with marked saturation of the inward current recorded at negative membrane potentials. Hence, in this channel type occupation by K+ of the pore appears to be non-uniform with low occupancy of sites near the outer entrance and saturation of the sites accessible from the internal solution.

The results show that channel closing is influenced by changes in the pore structure leading to alterations in the occupation of the channels by permeant cations. The differential effects of pore mutations and high external [K+] on closing and C-type inactivation indicate that the respective gates are associated with separate domains of the molecule.

Point mutations in the pore sequence can also lead to modifications in channel opening. In general, channels with fast C-type inactivation also show a fast rising phase of activation. However, these effects appear not to be due to primary modifications of the activation process but to arise from the coupling of activation and C-type inactivation.

These data, demonstrating that the pore structure influences most of the gating parameters of K+ channels, give further insight into the mechanisms underlying the modulation of K+ channel function by changes in the ionic composition in the extracellular milieu.

The delayed rectifier K+ channels comprise a set of membrane proteins that allow the selective transmembrane flux of K+ ions and participate in action potential repolarization and the regulation of repetitive firing (see Hille, 1992). The basic gating and ion selectivity properties of these K+ channels depend on specific molecular domains of an oligomer formed by four identical α-subunits (see for reviews Pongs, 1992; Jan & Jan, 1994). Positively charged amino acids in the fourth transmembrane segment of each α-subunit act as voltage sensors. The activation gate (which actually controls ion flow by opening or closing at positive or negative membrane potentials, respectively), although not identified yet, appears to be located near the intracellular mouth of the pore (see Armstrong, 1997; Liu, Holmgren, Jurman & Yellen, 1997). There are two major forms of inactivation, denoted N and C type. N-type inactivation is produced by the internal blockade of the pore with an N-terminus ball peptide tethered to the channel (Hoshi, Zagotta & Aldrich, 1990). C-type inactivation appears to depend on residues located in the opposite end of the amino acid sequence (particularly in the S5-S6 loop and the S6 segment) (Busch, Hurst, North, Adelman & Kavanaugh, 1991; Hoshi, Zagotta & Aldrich, 1991; De Biasi, Hartman, Drewe, Taglialatela, Brown & Kirsch, 1993; López-Barneo, Hoshi, Heinemann & Aldrich, 1993). Ion selectivity has been shown to rely mainly on the loop between the S5 and S6 segments, which form part of the aqueous pore (see Jan & Jan, 1994).

Although in the classical studies on voltage-dependent channels it was assumed that the two major functional features of the channels, gating and permeation, were independent, subsequent experiments indicated that these processes influence each other. An effect of permeant cations on K+ channel gating was first noticed by Armstrong and co-workers (Yeh & Armstrong, 1978; Swenson & Armstrong, 1981) in squid axons where they found that high external [K+] slowed the closure of the channels. To explain this result it was proposed that external cations occupying the pore act by a ‘foot in the door’ mechanism thereby preventing the conformational change necessary for channel deactivation (see also Stanfield, Ashcroft & Plant, 1981; Matteson & Swenson, 1986; Neyton & Pelleschi, 1991; Demo & Yellen, 1992). More recently, it has been observed that in Shaker B K+ channels with N-type inactivation removed, C-type inactivation is also slowed by external permeant cations (López-Barneo et al. 1993) or fast channel blockers, such as TEA+ (Grissmer & Cahalan, 1989; Choi, Aldrich & Yellen, 1991; Molina, Castellano & López-Barneo, 1997). In some channel types, external K+ also regulates the number of channels that open on depolarization (Pardo et al. 1992; López-Barneo et al. 1993). These observations have lead to the suggestion that, similar to the closing gate, a site in the pore must be emptied before C-inactivation can occur (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Baukrowitz & Yellen, 1996). Moreover, it has been shown that single amino acid mutation in position 449 or 447 in the pore region of Shaker K+ channels can change the C-type inactivation time course within three orders of magnitude (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Molina et al. 1997). These mutations also alter the permeability properties of the Shaker K+ channels in parallel with the effects on C-type inactivation: those channels with larger conductance tend to inactivate more slowly (López-Barneo et al. 1993). Thus, alterations in the C-inactivation rate resulting from pore mutations appear to be, at least partially, a consequence of the variable ion occupancy of the different channel types.

Here we have studied whether the same pore mutations that alter C-type inactivation and channel conductance can also modify the transitions between open and closed states. The major aim of this work was to test whether, as expected on the basis of the ‘foot in the door’ model of gating, pore mutations leading to alterations in C-type inactivation are paralleled by similar effects on channel closing. In addition, it appeared to us of importance to examine whether channel activation, generally presumed to be independent of ion permeation, is influenced by the type of amino acid present in the pore region. We show that pore mutations in Shaker K+ channels which accelerate C-type inactivation can produce marked changes in the deactivation time course. However, in some mutants the effects on C-type inactivation and deactivation can be segregated. We also show that single residue substitution in the pore of Shaker K+ channels can also lead to alterations in activation time course, although these effects seem to arise from the coupling between activation and C-type inactivation. These results give further insight into the mechanisms underlying the modulation of K+ channel function by permeant cations and the changes in the ionic composition in the extracellular milieu, which can occur in numerous physiological and pathophysiological circumstances.

METHODS

Molecular biology and expression of K+ channels in Chinese hamster ovary cells

For the wild-type construct we used the Shaker B Δ6-46 (Sh Δ) channel which has a deletion in the amino terminus that completely removes N-type inactivation (Hoshi et al. 1990). Point mutations were made on this construct using mismatched oligonucleotides and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). We studied K+ channel mutants with amino acid replacements in positions 447 or 449. These mutants were made as described previously (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Molina et al. 1997). The cDNAs encoding the various mutant channels were subcloned in plasmid p513, a derivative of pSG5 (Stratagene). For all mutations, the entire region of the PCR-amplified fragments was sequenced to check for the mutation and to ensure mistakes had not occurred during the PCR process. For channel expression we used Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transiently transfected with 2-10 μg of the cDNAs by electroporation (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad). For transfection, cells were resuspended in a sucrose-phosphate buffer solution (composition (mM): 1 sucrose, 1 K2HPO4, 1 KH2PO4 and 2 MgCl2) and placed in cuvettes at room temperature (∼22°C). Electroporation parameters (350 V and 125 μF) yielded typical time constant values of 24-26 ms. After electroporation the cells were resuspended in culture medium (McCoy's 5A (Biowhittaker) with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 1 % L-glutamine and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin), plated on slivers of glass coverslips, and maintained in a CO2 incubator at 37°C until use.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recordings were performed on cells 24-72 h after plating. For the experiments a coverslip was transferred to the recording chamber (∼0.2 ml) with continuous flow of solution that could be completely replaced in less than 40 s. K+ currents were recorded using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique as adapted to our laboratory. We used low resistance electrodes (1-3 MΩ), capacity compensation and subtraction of linear leakage and capacitive currents. Series resistance compensation was between 40 and 50 %. The deactivation time course of K+ tail currents and the C-type inactivation rate were estimated by fitting the appropriate current traces with a single exponential function.

The following standard solutions were used. External (mM): 140 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 4 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, adjusted to pH 7.4; pipette and internal (mM): 80 KCl, 30 potassium glutamate, 20 KF, 4 ATP-Mg, 10 Hepes, 10 EGTA, adjusted to pH 7.2). For high K+ external solutions 30, 70 or 140 mM NaCl was replaced by equimolar KCl. When external TEA+ was tested, TEACl equimolarly replaced NaCl. Unless otherwise noted, the holding potential in the electrophysiological experiments was -80 mV. The junction potential of the solutions was not compensated. Switching from the control (2.7 mM K+) external solution to solutions with 30, 70 and 140 mM K+ produced changes of junction potentials of approximately -0.6, -2 and -4.5 mV, respectively.

Experiments were performed at room temperature (∼22°C). Values in the figures and text are given as means ±s.d.

RESULTS

The K+ channel mutants with amino acid replacements in positions 447 or 449 were studied. The residue at position 449 varies among cloned K+ channels (see Stühmer et al. 1989; Drewe, Verma, Frech & Joho, 1992), is involved in TEA+ binding (MacKinnon & Yellen, 1990; Molina et al. 1997), and is known to influence C-type inactivation time course (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Yellen, Sodickson, Chen & Jurman, 1994). Aspartate at position 447, highly conserved among K+ channels, is important for cation selectivity (Heginbotham, Lu & MacKinnon, 1994; Kirsch, Pascual & Shieh, 1995) and also influences TEA+ affinity and C-type inactivation kinetics (Kirsch et al. 1995; Seoh & Papazian, 1995; Molina et al. 1997). In this last position we studied only the mutation that conserves the negative charge (D447E), since neutralization or reversion of the charge of this residue prevents the expression of K+ currents.

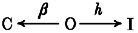

Pore mutants with parallel changes on closing and C-type inactivation time courses

To study the effects of pore mutations on deactivation we first characterized the single mutant D447E whose C-type inactivation rate is about 500-fold faster than the wild-type channel (D447D) and is slowed by external K+ and TEA+ (see Molina et al. 1997 and Fig. 1A). The closing kinetics of the two 447 channel variants (D447D and D447E) are compared in Fig. 1B with superposition of scaled K+ tail currents recorded in 30 mM external K+ upon repolarization to -50, -70 and -90 mV. For example, at -70 mV, the deactivation time constant (τc, see eqn (1)) of the D447E channel (0.48 ± 0.09 ms, n= 6) was about 5 times faster than in the wild-type channel (2.06 ± 0.65 ms, n= 8). Since upon repolarization the open channels (O) can switch to either closed (C) or inactivated (I) states:

Scheme 1.

Figure 1. Single amino acid mutation with parallel changes in closing and C-type inactivation.

A, C-type inactivation time course of wild-type (D447D, left panel) and mutated (D447E, right panel) channels. B, tail currents recorded in D447D (left) and D447E (right) channels with 30 mM external K+ following a depolarizing pulse to +20 mV and repolarization to -90, -70 and -50 mV. C, inverse of the deactivation rate constant (1/β, ordinate) plotted as a function of the membrane potential (Vm, abscissa). The deactivation rate constant was estimated as indicated in the text from measurements on tail currents recorded in 30 mM external K+. Data points are means ±s.d. of eighteen (D447D, ○) and nine (D447E, •) experiments.

τc depends on both the inactivation (h) and deactivation (β) rate constants according to the equation:

| (1) |

Since in both D447D and D447E channels macroscopic inactivation at membrane potentials more positive than 0 mV is voltage independent, we estimated the value of h from the inverse of the inactivation time constant measured at +20 mV. Afterwards, β was calculated from eqn (1). The plot in Fig. 1C shows that the differences in the closing rate constant of the two channel mutants were observed over a broad range of membrane potentials although they became less pronounced at more negative membrane voltages.

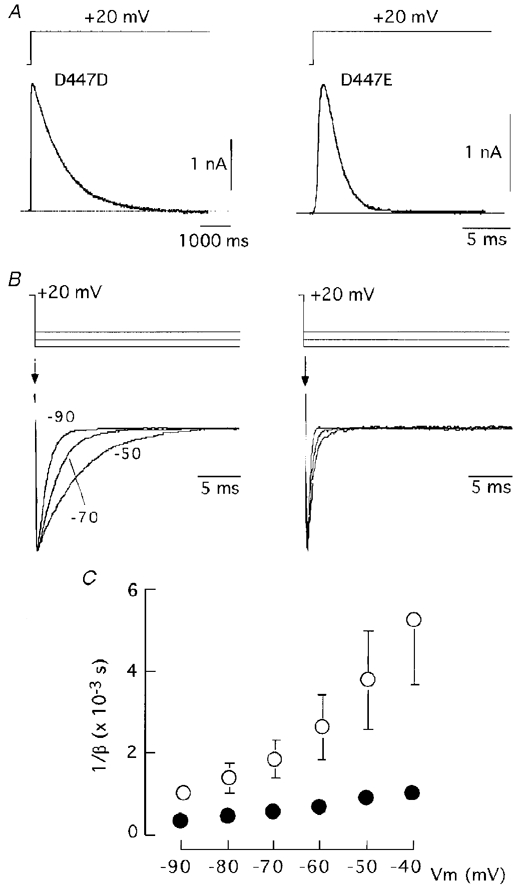

The fact that in the mutant D447E both C-type inactivation and closing are faster than in the wild-type channel may indicate that the mutation produces a uniform decrease in K+ occupancy along the channel pore (see Swenson & Armstrong, 1981; López-Barneo et al. 1993). Ion permeation through the open channels was studied with the pulse protocol described in Fig. 2A. Cells transfected with cDNA of the different channel types were exposed to high external K+ (30, 70 or 140 mM) and depolarized to +20 mV. We constructed instantaneous current-voltage (I-V) curves in the different experimental conditions by measuring the amplitude of tail currents recorded on repolarization to variable membrane potentials. Figure 2B shows that in the two channel types the slope conductance increased and that the instantaneous I-V relationship become more linear as extracellular [K+] was augmented. The dependence of membrane conductance on K+ was more apparent in the mutant D447E, although in the range of membrane potentials studied and with high external K+ the rates of ion flow in the inward and outward directions were similar. The reversal potentials of the K+ currents were not significantly different in the two channel types (-6.2 ± 2.1 mV (n= 4) for D447D and -7.2 ± 2.4 mV, (n= 4) for D447E with 70 mM external K+). In parallel with the effects on C-type inactivation (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Molina et al. 1997), high external K+ also decreased the rate of deactivation in these two channel types (Table 1). Thus, pore mutations such as D447E lead to parallel acceleration of the rates of C-inactivation and closing without affecting the selectivity of K+ over the other cations (mainly Na+) in the recording solutions. In the channel types D447D and D447E, closing and C-type inactivation rates were also affected in parallel by external K+.

Figure 2. Effects of external K+ on permeability and closing kinetics of channel variants at position 447.

A, representative traces of inward and outward tail currents recorded in channels D447D (left) and D447E (right) using the pulse protocol indicated in Fig. 4. The external solution contained 30 mM K+. Currents were obtained by depolarization to +20 mV and repolarization to variable voltages. The traces selected for the figures were obtained during repolarization to -90, -70, -50, -30, -10, 10 and 30 mV. B, instantaneous I-V relationship for 30 (•), 70 (▾) and 140 (○) mM external K+ in D447D (left) and D447E (right) channels. The maximal amplitude of each tail current (Itail, ordinate) is plotted as a function of Vm (abscissa). The intercepts with y= 0 are the estimates of the K+ equilibrium potential at the various K+ concentrations.

Table 1.

Alteration of closing kinetics by high extracellular K+ in various pore mutants

| Channel type | 1/β | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| at 30 mm K+ (ms) | at 70 mm K+ (ms) | at 140 mm K+ (ms) | |

| T449T (D447D) | 2.6 ± 0.8 (8) | 4.1 ± 0.6 (5) | — |

| T449E | 2.7 ± 0.5 (5) | 3.2 ± 0.4 (3) | — |

| T449K | 4.0 ± 0.7 (6) | 4.2 ± 0.6 (4) | 4.3 (1) |

| D447E | 0.7 ± 0.16 (6) | 0.9 ± 0.27 (4) | 1.4 (1) |

β was calculated from eqn (1). Vm= -60 mV. Values are means ±s.d., with number of experiments given in parentheses.

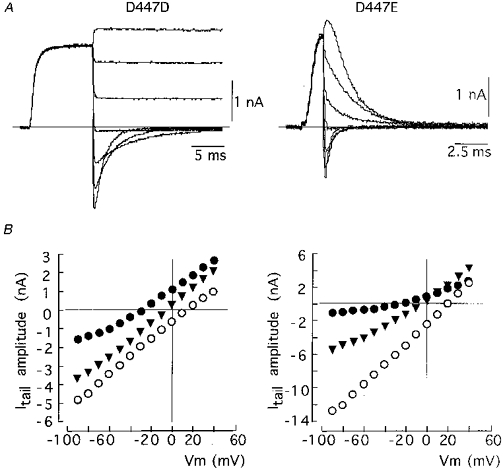

Pore mutations with differential effects on closing and C-type inactivation

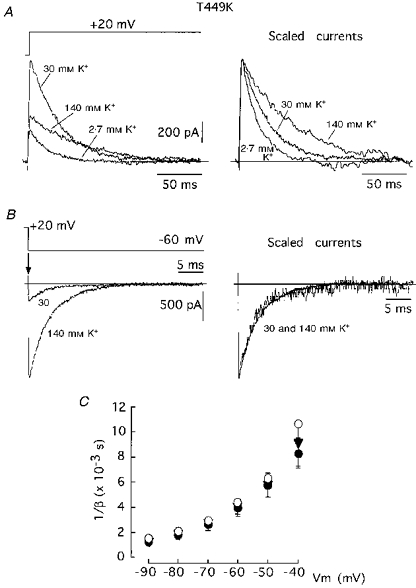

In contrast with the parallel effects of the mutation D447E on closing and C-type inactivation rates of Sh Δ channels, we have found pore mutations which influence differentially these two kinetic processes. For instance, the mutant T449E, which inactivates about 50 times faster than the wild-type channel (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Molina et al. 1997), closes at a rate that is similar to the wild-type construct and is little affected by increases in extracellular K+ (see Table 1). An even more marked separation between the changes of C-type inactivation and closing rates was observed in the mutant T449K which, like the T449E channel, shows fast C-type inactivation (López-Barneo et al. 1993; Molina et al. 1997), but closes at a rate that is slower than the wild-type channel and almost insensitive to extracellular K+ (see Table 1). We have studied in detail the dependence of closing on external K+ in the T449K channel, whose functional properties, like those of the mammalian homologous RCK4 which has a lysine at the position equivalent to 449, are strongly regulated by external [K+] (Pardo et al. 1992; López-Barneo et al. 1993; Ludewig, Lorra, Pongs & Heinemann, 1993). In cells transfected with the T449K cDNA, high external K+ produced an increase of the macroscopic current amplitude and slowing of the inactivation time course (Fig. 3A). These findings, similar to the original observations in Xenopus oocytes (López-Barneo et al. 1993), can be explained assuming that once inside the channel K+ ions can prevent both closed- and open-state inactivation. Hence, external K+ increases the number of channels that traverse the open state and the time that each channel stays open before inactivation occurs. The fast C-type inactivation of the T449K channel contrasts with its slow deactivation kinetics. In addition, although C-type inactivation of this channel is modulated by external K+, the deactivation time course over a full range of membrane potential is insensitive to extracellular K+ (Fig. 3B and C). These findings indicate that whereas in the T449K channel external K+ can accede to the site of the C-inactivation gate and compete with inactivation, the cations cannot alter the activation- deactivation gate. This ‘anomalous’ behaviour of the T449K channel, compared with what is seen in other pore mutants or some native K+ channels, could be the result of a non-uniform occupation of the channels by K+, thus having different effects on the C-inactivation and closing gates located in different sites along the channel pore. Figure 4 shows that the T449K channel retains a high K+ selectivity, with reversal potentials for K+ (-7.1 ± 0.3 mV (n= 4) with 70 mM external K+) similar to the wild-type channel (see above). However, in contrast to the channels described before (see Fig. 2) the instantaneous I-V curves of the T449K channel are markedly non-linear, with saturation at negative membrane potentials even in the presence of 140 mM external K+. The T449K channel can mediate large outward flow of K+, but it has low conductivity in the inward direction. This may indicate a high degree of K+ occupancy of the sites in the pore accessible from the internal solution but a low degree of occupancy of the sites accessible from the external solution. If the internal site of the pore is saturated (fully occupied) with K+ this may explain why deactivation (the gate for which is presumably located at the internal entry to the channel; e.g. Armstrong, 1997) is slower than in the wild-type channel and unaffected by external K+.

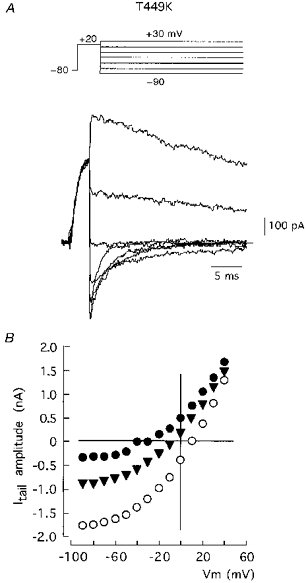

Figure 3. Single amino acid mutation (T449K) with differential effects on closing and C-type inactivation.

A, slowing of C-type inactivation time course in the T449K channels by external K+. Note in the left panel that 30 mM K+ leads to an increase in current amplitude. B, tail currents recorded at -60 mV with external solutions containing 30 and 140 mM K+. C, 1/β (ordinate) plotted as a function of Vm (abscissa). Same protocol as in Fig. 1C but using 30 (•), 70 (▾) and 140 mM (○) external K+. Data points are means ±s.d. of eight (30 mM K+), seven (70 mM K+) and one (140 mM K+) experiments.

Figure 4. Effects of external K+ on permeability and closing kinetics of channel T449K.

A, representative traces of inward and outward tail currents recorded using the pulse protocol indicated above. The external solution contained 70 mM K+. Currents were obtained by depolarization to +20 mV and repolarization to variable voltages (from -90 to +30 mV in steps of 10 mV). The traces selected for the figures were obtained during repolarization to -90, -70, -50, -30, -10, 10 and 30 mV. B, instantaneous I-V relationships at 30 (•), 70 (▾) and 140 mM (○) external K+. Itail (ordinate) is plotted as a function of Vm. The intercepts with y= 0 give estimates of the K+ equilibrium potential at the different K+ concentrations.

Pore mutations and activation time course

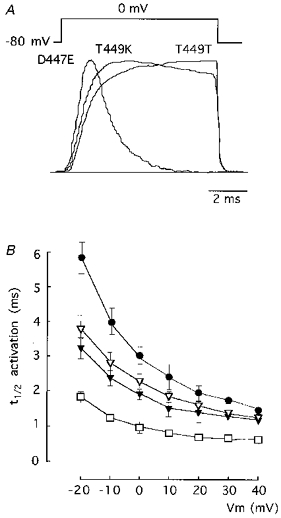

Besides the effects on closing, mutations in the pore also lead to changes in the activation time course of the channels. The shape of the activation rising phases of three representative channel types are compared in Fig. 5A with scaled traces of outward K+ currents generated during depolarizations to 0 mV. Note that the activation rising phase is greatly prolonged in the wild-type channel (T449T) when compared with the progressively faster time course of channels T449K and D447E. The plot in Fig. 5B shows that the differences in activation rise time of the various pore mutants are more apparent for small depolarizations. These changes in activation kinetics are similar to the modifications observed in Na+ currents after removal of inactivation with proteolytic enzymes (Gonoi & Hille, 1987; Cota & Armstrong, 1989). As suggested by these authors, the changes of activation in channels after primary modifications in inactivation rate can be readily explained by the gating model suggested by Bezanilla & Armstrong (1977), in which inactivation follows activation with a relatively high voltage-independent rate constant.

Figure 5. Activation time course in various pore mutants.

A, recordings of scaled macroscopic currents illustrating the activation time course of the channel type indicated in each case. Pulses of 8 ms duration to 0 mV. B, voltage dependence of the activation kinetics in T449T (•), T449K (▿), T449E (▾) and D447E (□) channel types. The time to reach half-peak current (t½) is plotted as a function of Vm during the pulses. Each point represents the mean ±s.d. of six to eight experiments.

Increasing the rate of C-type inactivation in Sh Δ channels has qualitatively the same effect on activation as the presence of the fast inactivation mechanism in Na+ channels. Hence, it seems that in Sh Δ channels activation and C-type inactivation are coupled and, therefore, pore mutations that increase the C-type inactivation rate lead to acceleration of activation. The relationship existing between activation and inactivation time courses in the pore mutants is also stressed in Fig. 6, where the mean t½ of activation (ordinate) is plotted against the inactivation time constant (abscissa) of various channel types measured in several experiments at three membrane potentials. Note that the effects of pore mutations on activation kinetics are more apparent with small depolarizations (open circles), when the values of the activation rate constants are relatively small and therefore activation time course is greatly influenced by the speed of inactivation (see Gonoi & Hille, 1987).

Figure 6. Relationship between activation and C-type inactivation kinetics in the various pore mutants studied.

Activation kinetics, estimated from t½ is represented on the ordinate. Inactivation time constant (τ) is represented on the abscissa. Data were obtained from macroscopic K+ currents recorded during depolarizing pulses to -20 (○), 0 (•) and +20 (▿) mV. Symbols and error bars represent means ±s.d. of six to eight experiments.

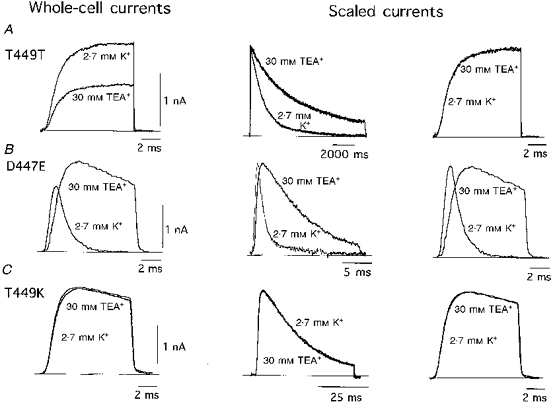

The coupling between activation and C-type inactivation was also tested using external TEA+ to slow down the C-type inactivation time course selectively in some pore mutants (Choi et al. 1990; Molina et al. 1997). Figure 7 illustrates the different effects of TEA+ on the activation and inactivation time courses in the wild-type channel (T449T; Fig. 7A) and in mutants D447E (Fig. 7B) and T449K (Fig. 7C). Addition of 30 mM TEA+ (a concentration near the EC50 for the wild-type channel; MacKinnon & Yellen, 1990; Molina et al. 1997) produced ∼50 % inhibition of current amplitude (Fig. 7A, left panel) and slowing of the inactivation time course (Fig. 7A, centre panel), but the activation time course was unaltered (Fig. 7A, right panel). These results are in accord with a coupled model of inactivation since in the T449T channel C-type inactivation is much slower than activation and, hence, a further decrease of inactivation rate by external TEA+ is not expected to produce any change in the activation time course. By contrast, in the mutant D447E, with a C-type inactivation rate hundreds of times faster than that for the wild-type channel, the slowing of C-type inactivation by TEA+ (Fig. 7B, centre panel) leads to an appreciable deceleration of the rising phase of activation (Fig. 7B, right panel). Note that in this mutant TEA+ produces a paradoxical increase in the macroscopic current amplitude (Fig. 7B, left panel) which can be interpreted as being due to inhibition of closed-state inactivation and the subsequent increase in the number of channels that reach the open state (see López-Barneo et al. 1993; Molina et al. 1997). In agreement with these ideas, TEA+ has no effect on either inactivation or activation time courses in the mutant T449K (Fig. 7C), which is known to be resistant to TEA+ block (MacKinnon & Yellen, 1990; Pardo et al. 1992; Molina et al. 1997). Similar to TEA+, high external K+ does not alter the activation time course in the wild-type channel (see also López-Barneo et al. 1993) or in mutants T449K or T449E; however, it produces a clear deceleration of activation kinetics in mutant D447E. For example, values for t½ of activation at +20 mV in the control (2.7 mM K+) solution were 2.01 ± 0.35 ms (n= 9), 1.60 ± 0.18 ms (n= 8), 1.39 ± 0.14 ms (n= 9) and 0.61 ± 0.15 ms (n= 8) for wild-type and channels T449K, T449E and D447E, respectively. With 70 mM external K+ these values changed to 2.18 ± 0.21 (n= 5); 1.66 ± 0.21 (n= 5); 1.69 ± 0.19 (n= 5) and 1.34 ± 0.21 (n= 6), respectively. Thus, external TEA+ or K+ do not seem to have a primary effect on the activation pathway, but can compete with the inactivation mechanism. In channels where C-type inactivation is very fast (as in mutant D447E), the net result of TEA+ or high external K+ is to slow down inactivation, which secondarily leads to deceleration of activation.

Figure 7. Effect of TEA+ on the activation and C-type inactivation time courses of three channel variants.

Recordings from the wild-type channel (A, T449T) can be compared with recordings from the D447E (B) and T449K (C) mutants. In all cases the external test solution contained 30 mM TEA+. Left panels are recordings obtained during 10 ms pulses to 0 mV. These recordings are shown scaled in the panels to the right. Scaled current traces in the central panels were obtained at +20 mV with pulses of 11 s for T449T, 20 ms for D447E and 50 ms for T449K. Holding potential was -80 mV in all experiments.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here indicate that, besides the changes in C-type inactivation reported previously (Lopez-Barneo et al. 1993; Baukrowitz & Yellen, 1995), single amino acid replacement in the pore region of Sh Δ K+ channels can produce alterations in activation and deactivation kinetics. The effects on activation appear to result from its coupling with C-type inactivation. Thus, pore mutations resulting in acceleration of C-type inactivation also have faster activation rising phase. Likewise, in channel types with fast C-type inactivation, slowing of inactivation with TEA+ leads to deceleration of the activation time course. In some pore mutants, acceleration of C-type inactivation is paralleled by a similar effect on closing and both C-type inactivation and deactivation kinetics are slowed by high external K+. These effects can be readily explained by the ‘foot in the door’ model of gating since the mutations appear to produce a uniform decrease of channel occupancy by K+, which reduces the competition of the cations with both the C-type inactivation and closing gates.

Interestingly, there are pore mutants (particularly the channel T449K) that C-inactivate at fast rates but close with a slower time course than the wild-type channel. In these cases, whereas C-type inactivation is strongly modulated by external K+, the deactivation kinetics appear to be almost insensitive to the cation. Given that the T449K channels can mediate a large outward flow of K+ but have a low conductivity in the inward direction, it appears that the mutation leads to a non-uniform occupation of the channel by K+: saturation of the sites accessible from the internal solution but low degree of occupancy of the sites accessible from the external solution. Saturation of internal sites (where the closing gate is presumably located) by K+ explains the slow closing of the channels and the lack of effect of further elevation of extracellular K+. These observations in the Sh Δ mutant T449K are in excellent accord with the work of Ludewig et al. (1993) on the variable sensitivity to blockade by internal Mg2+ of channels of the RCK family. These authors proposed that in the RCK4 channel (with a lysine in the position equivalent to position 449 of Shaker and insensitive to Mg2+ block) full occupation by K+ of internal sites prevents access by Mg2+ to the blocking site. As discussed before (Molina et al. 1997), the low occupancy by cations of the external entrance to the pore in mutant T449K may be related in part to the hydrophilicity of lysine, with a hydropathy index (-3.6) severalfold larger than threonine (-0.7) (Kyte & Doolittle, 1982). The hydrophilic environment created by the lysines possibly acts as an energy barrier, making difficult the dehydration of K+ ions, which is necessary for them to access deeper regions of the pore. These same phenomena may favour the flow of ions in the outward direction which is a characteristic of the T449K channel. Thus, the lysine in position 449 determines biophysical features that are important for the function of native channels, such as RCK4, with the same residue in an equivalent position. These channels participate in action potential repolarization, and hence it is important to ensure that at positive membrane potentials they can mediate a large outward flow of current and are resistant to blockade by internal divalent cations.

The fact that in some pore mutants extracellular K+ has different effects on inactivation and closing is a clear demonstration that the C-type inactivation and deactivation gates are located in separate regions of the channel. The effects of mutations in the S5-S6 loop and of external K+ or TEA+ on inactivation indicates that the C-inactivation gate is accessible from the extracellular solution (Choi et al. 1991; López-Barneo et al. 1993; Baukrowitz & Yellen, 1996; Molina et al. 1997). In contrast, classical experiments using TEA+ derivatives suggested that the activation-deactivation gate is located near the internal mouth of the K+ channels (Armstrong, 1971; see also Armstrong, 1997). In accord with this idea recent experiments on recombinant K+ channels have identified amino acids directly involved in channel closing located in the S4-S5 intracellular loop and the internal portion of the S6 segment (Armstrong, 1997; Liu et al. 1997).

In conclusion, mutations in the pore produce not only alterations in permeation but also in most of the kinetic parameters of K+ channels, including activation, C-type inactivation and closing. Permeant ions seem to constitute part of the channel molecule and thus are required for their normal function (see Yellen, 1997). It is therefore possible that some of the changes in the amino acid sequence of the pore among the various families of K+ channels determine modifications in their kinetic properties or response to alterations in the ionic composition of the extracellular milieu. For example, the variation in the amino acid at position 449 among the various families of voltage-gated K+ channels (see Drewe et al. 1992) or even among members of a given family (Stühmer et al. 1989), might help to explain differences in the activation-deactivation parameters of channels sharing similar S4 segments. The differential modulation of the gating properties of K+ channels by external monovalent cations, influenced by the pore structure, might contribute to differences in the electrical activity of individual neurons in physiological or pathological conditions, such as epilepsy or ischaemia, with significant elevation of extracellular K+ in neural tissue (e.g. see Hansen & Zeuthen, 1981; Sykova, 1983; Heinemann, Konnerth, Pumain & Wadman, 1986).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported with grants from the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (DGICYT) of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Education and the Andalusian Government. We would like to thank Drs Lucía Tabares and Uwe Ludewig for comments on the manuscript.

References

- Armstrong CM. Interaction of tetraethylammonium ion derivatives with the potassium channel of giant axons. Journal of General Physiology. 1971;58:413–437. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413. 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CM. A closer picture of the K channel gate from ion trapping experiments. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:523–524. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.5.523. 10.1085/jgp.109.5.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz & Yellen G. Modulation of K+ current by frequency and external [K+]: a tale of two inactivating mechanisms. Neuron. 1995;15:951–960. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz & Yellen G. Use-dependent blockers and exit rate of the last ion from the multi-ion pore of a K+ channel. Science. 1996;271:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F, Armstrong CM. Inactivation of the sodium channels. I. Sodium current experiments. Journal of General Physiology. 1977;70:549–566. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.5.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch AE, Hurst RS, North RA, Adelman JP, Kavanaugh MP. Current inactivation involves a histidine residue in the pore of the rat lymphocyte potassium channel RGK5. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1991;179:1384–1390. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91726-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KL, Aldrich RW, Yellen G. Tetraethylammonium blockade distinguishes two inactivating mechanisms in voltage-activated K+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:5092–5095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota G, Armstrong CM. Sodium channel gating in clonal pituitary cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:213–232. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biasi M, Hartman HA, Drewe JA, Taglialatela M, Brown AM, Kirsch GE. Inactivation determined by a single site in K+ pores. Pflügers Archiv. 1993;422:354–363. doi: 10.1007/BF00374291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demo S, Yellen G. Ion effects on gating of the Ca2+-activated K+ channels correlate with occupancy of the pore. Biophysical Journal. 1992;61:639–649. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81869-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewe JA, Verma S, Frech G, Joho RH. Distinct spatial and temporal expression patterns of K+ channel mRNAs from different subfamilies. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:538–548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00538.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonoi T, Hille B. Gating of the Na+ channel. Inactivation modifiers discriminate among models. Journal of General Physiology. 1987;89:253–274. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Cahalan M. TEA prevents inactivation while blocking open K+ channels in human T lymphocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1989;55:203–206. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82793-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AJ, Zeuthen T. Extracellular ion concentration during spreading depression and ischemia in the rat brain cortex. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1981;113:437–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1981.tb06920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham L, Lu Z, MacKinnon R. Mutations in the K+ channels signature sequence. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Konnerth A, Pumain R, Wadman WJ. Extracellular calcium and potassium concentration changes in chronic epileptic brain tissue. Advances in Neurology. 1986;44:641–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Biophysical and molecular mechanisms of Shaker potassium channel inactivation. Science. 1990;250:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.2122519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Two types of inactivation in Shaker K+ channels: effects of alterations in the carboxy-terminal region. Neuron. 1991;7:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan LY, Jan YN. Potassium channels and their evolving gates. Nature. 1994;371:119–122. doi: 10.1038/371119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch GE, Pascual JM, Shieh C-C. Functional role of a conserved aspartate in the external mouth of voltage-gated potassium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:1804–1813. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80357-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J, Doolittle RS. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Holmgren M, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Gated access to the pore of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Neuron. 1997;19:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Barneo J, Hoshi T, Heinemann SH, Aldrich RW. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors and Channels. 1993;1:61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig U, Lorra C, Pongs O, Heinemann SH. A site accessible to extracellular TEA+ and K+ influences intracellular Mg2+ block of cloned potassium channels. European Biophysics Journal. 1993;22:237–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00180258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R, Yellen G. Mutations affecting TEA blockade and ion permeation in voltage-activated K+ channels. Science. 1990;250:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.2218530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteson DR, Swenson RP. External monovalent cations that impede the closing of K+ channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1986;87:795–816. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.5.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina A, Castellano AG, López-Barneo J. Pore mutations in Shaker K+ channels distinguish between the sites of TEA blockade and C-type inactivation. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:361–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyton J, Pelleschi M. Multi-ion occupancy alters gating in high conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:641–665. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.4.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo LA, Heinemann SH, Terlau H, Ludewig U, Lorra C, Pongs O, Stühmer W. Extracellular K+ specifically modulates a rat brain K+ channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongs O. Molecular biology of voltage-dependent potassium channels. Physiological Reviews. 1992;72:S69–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoh S-A, Papazian DM. Mutations at D447 in the P region of Shaker K+ channels accelerate C-type inactivation. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:A35. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield PR, Ashcroft FM, Plant TD. Gating of a muscle K+ channel and its dependence on the permeating ion species. Nature. 1981;289:509–511. doi: 10.1038/289509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stühmer W, Ruppersberg JP, Schröter KH, Sakmann B, Stocker M, Giese KP, Perschke A, Baumann A, Pongs O. Molecular basis of functional diversity of voltage-gated potassium channels in mammalian brain. EMBO Journal. 1989;8:3235–3244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykova E. Extracellular K+ accumulation in the central nervous system. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 1983;42:135–189. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(83)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson RP, Armstrong CM. K+ channels close more slowly in the presence of external K+ and Rb+ Nature. 1981;291:427–429. doi: 10.1038/291427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JZ, Armstrong CM. Immobilisation of gating charge by a substance that simulates inactivation. Nature. 1978;273:387–389. doi: 10.1038/273387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen G. Single channel seeks permeant ion for brief but intimate relationship. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:83–85. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen G, Sodickson D, Chen T-Y, Jurman ME. An engineered cysteine in the external mouth of a K+ channel allows inactivation to be modulated by metal binding. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:1068–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80888-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]