Abstract

The intestinal transport of L-methionine has been investigated in brush-border membrane vesicles isolated from the jejunum of 6-week-old chickens. L-Methionine influx is mediated by passive diffusion and by Na+-dependent and Na+-independent carrier-mediated mechanisms.

In the absence of Na+, cis-inhibition experiments with neutral and cationic amino acids indicate that two transport components are involved in L-methionine influx: one sensitive to L-lysine and the other sensitive to 2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH). The L-lysine-sensitive flux is strongly inhibited by L-phenylalanine and can be broken down into two pathways, one sensitive to N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and the other to L-glutamine and L-cystine.

The kinetics of L-methionine influx in Na+-free conditions is described by a model involving three transport systems, here called a,b and c: systems a and b are able to interact with cationic amino acids but differ in their kinetic characteristics (system a: Km= 2.2 ± 0.3 μM and Vmax= 0.13 ± 0.005 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1; system b: Km= 3.0 ± 0.3 mM and Vmax= 465 ± 4.3 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1); system c is specific for neutral amino acids, has a Km of 1.29 ± 0.08 mM and a Vmax of 229 ± 5.0 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1 and is sensitive to BCH inhibition.

The Na+-dependent component can be inhibited by BCH and L-phenylalanine but cannot interact either with cationic amino acids or with α-(methylamino)isobutyrate (MeAIB).

The kinetic analysis of L-methionine influx under a Na+ gradient confirms the activity of the above described transport systems a and b. System a is not affected by the presence of Na+ while system b shows a 3-fold decrease in the Michaelis constant and a 1.4-fold increase in Vmax. In the presence of Na+, the BCH-sensitive component can be subdivided into two pathways: one corresponds to system c and the other is Na+ dependent and has a Km of 0.64 ± 0.013 mM and a Vmax of 391 ± 2.3 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1.

It is concluded that L-methionine is transported in the chicken jejunum by four transport systems, one with functional characteristics similar to those of system bo, + (system a); a second (system b) similar to system y+, which we suggest naming y+m to account for its high Vmax for L-methionine transport in the absence of Na+; a third (system c) which is Na+ independent and has similar properties to system L; and a fourth showing Na+ dependence and tentatively identified with system B.

The absorption of dipolar amino acids by the intestine of vertebrates is mediated by multiple pathways. According to Mailliard, Stevens & Mann (1995), these include diffusion and several Na+-dependent mechanisms (e.g. systems A, ASC, B and Bo, +) and Na+-independent mechanisms (e.g. systems L, bo, + and y+). Such a number of possible transport systems makes distinction between them a rather complicated task. Strategies to functionally isolate dipolar amino acid carriers include the study of their different sensitivities to Na+, their capacity to interact with certain amino acids and with amino acid analogues (such as 2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH) or α-(methylamino)isobutyrate (MeAIB)), the effects of membrane potential on substrate influx, their sensitivity to reagents such as N-ethylmaleimide and the analysis of their transport kinetic constants.

L-Methionine is a dipolar amino acid of nutritional significance. It is an essential amino acid for mammals and it has been shown to be limiting in poultry nutrition (D'Mello, 1994). For this reason it is commonly added to the diet of poultry, usually in the form of either DL-methionine or the hydroxy analogue DL-2-hydroxy-4-methylthiobutanoic acid (Baker, 1986). There is little information about how the chicken intestine absorbs L-methionine and reports dealing with the intestinal mechanisms involved are few. Lerner, Sattelmeyer & Rush (1975) reported that L-methionine is transported by a single Na+-dependent mechanism and this was later confirmed by Knight & Dibner (1984) in everted segments and by Brachet & Puigserver (1989) in brush-border membrane vesicles.

Recently, Maenz & Engele-Schaan (1996) have identified the uptake mechanism as a system B-type carrier, able to transport neutral amino acids both under a Na+ gradient and in Na+-free conditions. This indicates that a single transport system should explain the current results of intestinal uptake of L-methionine by the chicken intestine. However, studies carried out in our laboratory on the mechanism of L-lysine absorption by the chicken intestine (Torras-Llort, Ferrer, Soriano-García & Moretó, 1996; Torras-Llort, Soriano-García, Ferrer & Moretó, 1998) indicate that the uptake of L-lysine is strongly inhibited by L-methionine across the bo, + -like system (Ki in the micromolar range) as well as across the y+-like system (Ki in the millimolar range). The aim of the present work was to characterize L-methionine transport across these systems as well as other pathways not shared with cationic amino acids. The results obtained support the view that L-methionine can be taken up by the apical membrane of enterocytes by four separate transport systems.

Part of this work was presented to the 14th meeting of the European Intestinal Transport group and has been published in abstract form (Soriano-García, Torras-Llort, Planas, Ferrer & Moretó, 1996).

METHODS

Isolation of brush-border membrane vesicles (BBMVs)

Membranes were isolated from the jejunum of 6-week-old male Label chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus L.) fed a balanced diet containing 20 % protein and 0.5 % methionine (of which 0.12 % was added DL-methionine), prepared by IRTA-Mas Bové (Reus, Spain). Animals were killed in the morning without previous starvation, by cervical dislocation. The jejunum (from the end of the duodenal loop to Meckel's diverticulum) was removed, immediately flushed with ice-cold saline, opened lengthwise, frozen in liquid N2 and then stored at -80°C. Manipulation and experimental procedures are in accordance with the Spanish regulations for the use and handling of experimental animals.

BBMVs were prepared by using the Mg2+-precipitation method of Kessler, Acuto, Storelli, Murer, Müller & Semenza (1978) as previously described (Torras-Llort et al. 1996). The composition of the intravesicular medium was: 300 mM mannitol, 0.1 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 0.02 % LiN3 and 20 mM Hepes-Tris (pH 7.4). Vesicles were diluted to a final protein concentration of 20-30 mg ml−1, frozen and stored in liquid N2 in 150 μl aliquots for no more than 5 months. Each isolation batch corresponds to the jejunum of one chicken and in Results n indicates the number of chickens or membrane preparations. The orientation of the vesicles (94 % right-side oriented), purity (11-fold enrichment for sucrase and 0.3-fold for Na+-K+-ATPase) and functional properties of the membrane preparations were routinely assayed as previously described (Torras-Llort et al. 1996). Protein was determined using the BioRad protein assay, with bovine serum albumin as standard.

Uptake assays

Transport experiments were carried out at 37°C for incubation periods ranging from 1 s to 60 min (equilibrium) using a rapid filtration technique. Short incubation times (1-5 s) were manually sampled with the experimenter following the rhythm of a 1 Hz flashing lamp and counting the appropriate number of cycles (Torras-Llort et al. 1996). The vesicles were incubated at 37°C to avoid the changes in cationic and neutral amino acid transport activity described for lower incubation temperatures (Furesz, Moe & Smith, 1995; Maenz & Engele-Schaan, 1996). The composition of the incubation medium in standard experiments was: 100 mM mannitol, 0.2 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 0.02 % LiN3, 20 mM Hepes-Tris (pH 7.4), the appropriate labelled and unlabelled L-methionine concentration, and 100 mM NaSCN, NaCl, sodium gluconate (NaGlu), KSCN, KCl or choline chloride (ChoCl). Intra- and extravesicular media were isotonic (320 mosmol l−1, routinely assayed with an Osmomat 30 cryoscopic osmometer, Berlin, Germany). The effect of increasing osmolarity on substrate uptake was determined as described before (Torras-Llort et al. 1996). When the incubation medium contained L-cystine it was supplemented with 10 mM diamide to prevent the reduction of disulphide bonds (Magagnin et al. 1992). In these conditions, diamide did not affect L-methionine influx. Incubation was stopped by the addition of 2 ml ice-cold stop solution (150 mM KSCN, 0.02 % LiN3 and 20 mM Hepes-Tris, pH 7.4). Samples were rapidly filtered under negative pressure through pre-wetted and chilled 0.22 μm cellulose acetate-nitrate filters (Millipore GSWP02500, Bedford, MA, USA). The filters were rinsed four times with 2 ml ice-cold stop solution and dissolved in Biogreen-6 cocktail from Sharlau (Barcelona, Spain). Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting (Packard Tri-Carb, model 1500). Non-specific tracer fixation to the filters was obtained by adding ice-cold stop solution to reaction tubes immediately before addition of the vesicles. The effect of 0.5 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) on L-methionine transport was assayed as previously described (Torras-Llort et al. 1996). Experiments were performed with at least three different membrane preparations, each in triplicate.

Kinetic analysis

The kinetic parameters of L-methionine influx were calculated from inhibition curves using 0.5 μM L-[3H]methionine or 50 μM L-[14C]methionine as substrate and varying concentrations of unlabelled amino acids on the cis side. The non-saturable component was calculated from L-methionine influx in the presence of 30 mM (when substrate concentration was 50 μM) or 100 μM (when substrate concentraton was 0.5 μM) unlabelled L-methionine and the flux was subtracted from total L-methionine influx. The calculated KD was 82 nl (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1.

Transport linearity was maintained in all the conditions tested for at least the first 3 s incubation (under Na+ or K+ gradient, for both 50 or 0.5 μM L-methionine and in the presence of high unlabelled substrate concentrations; data not shown). Instantaneous tracer binding to the membrane was quantified from the y-intercept of the regression line calculated for the 1-3 s L-methionine influx results. At low L-methionine concentrations (0.5-50 μM) the amount of substrate bound to the membrane after a 2 s incubation accounted for less than 6 % of the total mediated influx.

The rates of mediated transport were fitted by non-linear regression analysis, from plots generated by the Biosoft Enzfitter statistical package (Cambridge, UK). The residual sum of squares of the fits has been used to compare the contribution of each model (L-methionine transport mediated by one, two or three transport systems) to explain the experimental data. The best fit was assigned, according to the criteria of Motulsky & Ransnas (1987), to the fit showing the lowest as well as statistically different residual sums of squares (P < 0.05).

Transport equations

The influx rate equations for the transport of a substrate (S) through one or two transport systems (a and b) in the presence of a competitive inhibitor (I) were given by eqns (1) and (2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Km and Ki are the inhibition and half-saturation constants for the substrate (S) and the competitive inhibitor (I), respectively, and Vmax the maximum rate of transport.

To reduce the number of unknown factors in eqns (1) and (2) the approach of Devés, Chávez & Boyd (1992) was followed. Thus, the relative transport rates v/vo of L-methionine transport with and without unlabelled inhibitor can be written, when the substrate concentration is low, as follows:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where Fa/b is the ‘permeability’ ratio, indicative of the relative contributions of systems a and b to the total substrate influx:

| (5) |

The same approach was then used to develop an equation for the relative transport rates of L-methionine uptake when three transport systems (a,b and c) are considered. The resulting equation is given by:

| (6) |

where a= 1+ ([I]/Ki,a), b= 1+ ([I]/Ki,b) and c= 1+ ([I]/Ki,c). Here, Fc/b indicates the contribution of system c relative to system b:

| (7) |

The experimental strategy for the kinetic analysis consisted of the following.

(1) Calculation of the ‘permeability’ ratios (F), for fits involving two or more transport systems, and Michaelis constants (Km) from L-methionine self-inhibition relative transport rates (v/vo) in the presence of one or two selective inhibitors (10 mM L-lysine or 10 mM BCH ± 0.5 mM NEM). In these conditions, the number of functional pathways involved in L-methionine uptake was reduced, thus simplifying the kinetic analysis.

(2) Calculation of Vmax values from L-methionine self-inhibition transport rates (v) in the presence of the selective inhibitors, taking the Km values calculated in step (1) as fixed.

(3) Determination of the adequacy of the experimental L-methionine v/vo values with the curve drawn by inserting in eqn (6) the kinetic parameters calculated in step (1).

(4) Calculation of the inhibition constants (Ki) from L-methionine relative transport rates in the presence of increasing concentrations of the selective inhibitors.

Data analysis

The data were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) except for the comparison of kinetic parameters where Student's t test was used. In both cases a P < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

Chemicals

All unlabelled reagents were obtained from Sigma. L-[U-14C]methionine and L-[methyl-3H]methionine were obtained from New England Nuclear Research Products (Dreieich, Germany).

RESULTS

Effect of osmolarity

L-Methionine uptake (100 μM L-methionine) in equilibrium conditions (60 min incubation) in the presence of NaSCN (initial [NaSCN]o= 100 mM, [NaSCN]i= 0 mM) shows a linear relationship in the osmolarity range 220-720 mosmol l−1 (data not shown). The results also indicate that under standard incubation conditions (320 mosmol l−1, isotonic conditions), 88 % of L-methionine is taken up by the vesicles and 12 % remains bound to the membrane (significantly different from 0, P < 0.05). Vesicular volume, calculated according to Berteloot (1984), was 0.47 ± 0.02 μl (mg protein)−1.

Time course of uptake

L-Methionine uptake (100 μM) was determined under inwardly directed NaSCN or KSCN gradients (100 mM). In the presence of Na+, there was a transient overshoot that peaked at 2 s of incubation (Fig. 1). At this point L-methionine was accumulated in the vesicles to 2.2 times the equilibrium value (concentration at equilibrium was 110 μM). When NaSCN was replaced by KSCN, no overshoot was observed and equilibrium values did not differ from those obtained in the presence of Na+ (P≥ 0.05). Incubation in the presence of K+ plus 50 mM unlabelled L-methionine reduced the initial uptake of labelled L-methionine, indicating a self-inhibiting effect and suggesting the presence of a Na+-independent mediated component. Equilibrium values were identical to those obtained in the absence of the unlabelled substrate (P≥ 0.05).

Figure 1. Time course for uptake of 100 μM L-methionine under zero-trans 100 mM NaSCN (○), KSCN (•) or a KSCN gradient and 50 mM L-methionine (□).

Membranes were prepared in 300 mM mannitol, 0.1 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 0.02 % LiN3 and 20 mM Hepes-Tris, pH 7.4 and incubated (37 °C) in 100 mM NaSCN or KSCN, 100 mM mannitol, 0.2 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 0.02 % LiN3, 20 mM Hepes-Tris, pH 7.4 and 100 μM L-methionine (50 μM L-[14C]methionine). Osmolarity was maintained by reducing mannitol concentration. Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 4-5 membrane preparations. Only s.e.m. that exceed the size of the symbol are shown.

Na+ dependence

L-Methionine influx (2 s, 100 μM) was determined under zero-trans NaSCN gradients ranging from 1 to 100 mM (mannitol was used to compensate for extravesicular osmolarity). The results (Fig. 2) indicate that increasing external Na+ concentration from 1 to 100 mM induces a 4.5-fold increase in the initial uptake of L-methionine. Such an increase demonstrates the presence of a Na+-dependent component that has maximal activity already at 25 mM external Na+ (comparison of uptake in the presence of 25 and 100 mM Na+ shows no statistical differences; P≥ 0.05).

Figure 2. Effect of an increasing zero-trans Na+ gradient on 100 μM L-methionine uptake (50 μM L-[14C]methionine).

Vesicles were prepared as described in legend of Fig. 1 and incubated in the presence of increasing NaSCN concentrations (1-100 mM). Osmolarity was maintained with mannitol. Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 3 membrane preparations.

Membrane potential effect

Initial L-methionine transport (2 s, 100 μM) was quantified in the presence of varying zero-trans Na+ and K+ salts (100 mM) in order to induce different membrane potentials (Kimmich, Randles, Restrepo & Montrose, 1985). The results (Table 1) indicate that with Na+ present, L-methionine influx is the same in the presence of either SCN− or Cl− and both are higher than in the presence of non-diffusible gluconate. In the presence of K+ salts, influx was significantly reduced as expected for a Na+-dependent mechanism. The lower values obtained in the presence of choline chloride support the observations of Campione, Haghighat, Gorman & Van Winkle (1987) in mouse blastocysts and Herzberg & Lerner (1973) in the chicken intestine, and can be attributed to an interaction of choline with the mechanisms involved in amino acid transport.

Table 1.

Effect of different salts (A) and effect of a valinomycin-induced K+ diffusion potential (B) on 100 μm l-methionine influx

| Salt | l-Methionine influx (pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| A. | NaSCN | 115 ± 9.8a |

| NaCl | 105 ± 7.5a | |

| NaGlu | 83 ± 2.1b | |

| KSCN | 35 ± 3.1c | |

| KCl | 38 ± 5.5c | |

| ChoCl | 24 ± 1.7d | |

| B. | Control | 157 ± 27.1 |

| Valinomycin | 297 ± 30.4 |

A. Vesicles were incubated for 2 s in the presence of 100 mm zero-trans of the corresponding salt. [Salt]o= 100 mm, [salt]i= 0. Means with different superscript show statistical differences (P < 0.05). B. Vesicles were preloaded (1 h, 21 °C) with 100 mm KCl and incubated in the presence of 90 mm NaCl, 10 mm KCl and 15 μm valinomycin or the corresponding volume of ethanol. [NaCl]o= 90 mm, [KCl]o= 10 mm, [KCl]i= 100 mm. l-Methionine uptake was enhanced 1.9-fold by valinomycin (P < 0.05). Each value represents the mean ± s.e.m. of 3 membrane preparations.

The effect of membrane potential on L-methionine transport was further investigated using a valinomycin-induced K+ diffusion potential. L-Methionine influx (100 μM) was examined in vesicles preloaded with KCl and incubated under an inwardly directed Na+ gradient in the presence or absence of valinomycin (Table 1). The valinomycin-induced K+ efflux will promote an inside negative potential that will further increase the electrochemical gradient for Na+ across the membrane. In these experimental conditions L-methionine influx was significantly enhanced (1.9-fold), supporting the view that L-methionine transport is electrogenic.

Cis-inhibition in Na+-free conditions

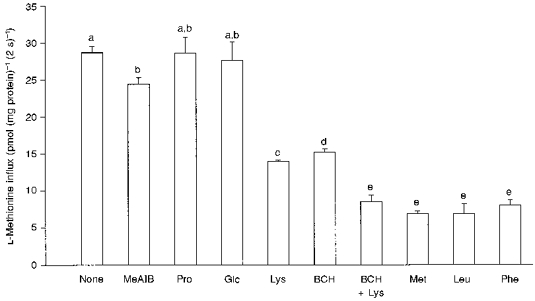

Substrate specificity of L-methionine transport was studied in cis-inhibition experiments. The effects of relatively high concentrations of various amino acids on the initial influx of L-methionine (2 s, 50 μM) were studied under a KSCN gradient (Fig. 3). The results indicate no interaction with L-proline and D-glucose, a partial inhibition in the presence of L-lysine, BCH and MeAIB, and a maximal reduction of L-methionine influx with L-leucine, L-phenylalanine and L-methionine itself present in the medium. The inhibitory effect observed with L-lysine suggests the presence of a transport component shared by neutral and cationic amino acids. However, since the observed inhibition was not complete, the participation of another component insensitive to cationic amino acids was also considered. The additive inhibitory effect observed with L-lysine plus BCH (both at 10 mM) would support the hypothesis that L-methionine uptake takes place across two pathways showing different sensitivity to L-lysine and BCH.

Figure 3. Cis-inhibition of L-[14C]methionine influx (50 μM) by L-amino acids, BCH, MeAIB and D-glucose (all at 10 mM) under a 100 mM zero-trans KSCN gradient.

Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 3-5 membrane preparations. The bars labelled with different letters show statistical differences (P < 0.05).

These results are further sustained by cis-inhibition experiments (Table 2) which show that L-methionine is transported by an NEM-sensitive pathway and that the NEM-insensitive influx can be reduced by L-lysine and the remaining flux further inhibited by BCH. These results point to the existence of at least three separate uptake transport systems. L-Glutamine and the dipeptide L-cystine partially inhibit the BCH-insensitive L-methionine uptake, both in the presence and in the absence of NEM while L-phenylalanine abolishes the transport of the BCH-insensitive component. The significance of these results in transport system discrimination will be discussed later.

Table 2.

Cis-inhibition of 50 μm l-[14C]methionine by neutral and cationic l-amino acids and BCH in the absence and presence of NEM (0.5 mm)

| Cis-inhibitor | − NEM | + NEM |

|---|---|---|

| None | 24.5 ± 0.6a | 15.2 ± 0.2b |

| l-Lysine | 13.9 ± 0.2c | 12.7 ± 0.7c,e |

| BCH | 15.8 ± 0.8b | 8.8 ± 0.2d |

| BCH + l-cystine | 11.5 ± 0.6e | 6.5 ± 0.3f |

| BCH + l-glutamine | 12.2 ± 2.0c,e | 5.2 ± 0.2g |

| BCH + l-phenylalanine | 4.6 ± 1.2g | 4.3 ± 1.0g |

| BCH + l-methionine | 5.4 ± 0.14g | — |

Vesicles were incubated for 2 s under a 100 mm zero-trans KSCN zero-trans gradient in the presence of 10 mm unlabelled inhibitor, except l-glutamine and l-cystine which were 1 and 0.2 mm, respectively. Incubation media containing l-cystine were supplemented with 10 mm diamide to prevent the reduction of disulphide bonds. Diamide did not affect l-methionine influx. Each value represents the mean ± s.e.m. of 3-8 membrane preparations. Means with different superscript show statistical differences (P < 0.05).

Hetero-exchange

The effect of high extravesicular unlabelled amino acid concentration on the efflux of L-methionine in pre-loaded vesicles was studied under a zero-trans KSCN gradient. The vesicles were preloaded with 50 μM L-[14C]methionine and incubated in the presence of 10 mM neutral or cationic amino acids. The results were expressed as L-methionine efflux from the vesicles after 2 and 20 s incubation. Results (Table 3) show that all amino acids assayed, especially cationic amino acids, significantly trans-stimulate L-methionine efflux.

Table 3.

Hetero-exchange of l-methionine transport by neutral and cationic amino acids

| Trans-amino acid | l-Methionine efflux (pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) | l-Methionine efflux (pmol (mg protein)−1 (20 s)−1) |

|---|---|---|

| None (control) | 5.3 ± 0.25 | 15.2 ± 1.30 |

| l-Methionine | 11.8 ± 0.29 * | 19.3 ± 0.48 * |

| l-Leucine | 11.1 ± 0.80 * | 20.5 ± 1.30 * |

| l-Phenylalanine | 10.4 ± 0.59 * | 20.2 ± 0.50 * |

| l-Arginine | 14.2 ± 1.30 * | 24.6 ± 2.00 * |

| l-Lysine | 14.7 ± 0.93 * | 25.7 ± 1.70 * |

Vesicles were preloaded (30 min, 21°C) with 50 μm l-[14C]methionine and incubated under zero-trans 100 mm KSCN gradient in the absence or presence of 10 mm unlabelled amino acids. The results were expressed as pmol l-methionine (mg protein)−1 leaving the vesicles after 2 or 20 s incubation. Each value represents the mean ± s.e.m. of 3-4 membrane preparations.

P < 0.05 versus control.

Substrate specificity for the Na+-dependent component

The results of cis-inhibition experiments under an NaSCN gradient are shown in Fig. 4. The Na+-dependent component (dashed bars) was calculated by subtracting KSCN from NaSCN values, since the passive diffusion of L-methionine was the same (P≥ 0.05) in the presence of Na+ or K+. The results show that Na+-dependent L-methionine influx is not affected by MeAIB or by L-lysine. They also show that BCH exerts a small but significant effect and that substrate influx is virtually abolished by L-methionine and L-phenylalanine.

Figure 4. Cis-inhibition of L-[14C]methionine influx (50 μM) by L-amino acids, BCH and MeAIB (all at 10 mM) under a 100 mM zero-trans NaSCN gradient.

The Na+-dependent component (dashed bars) was obtained by subtracting KSCN results (Fig. 3) from NaSCN values (open bars). The passive diffusion of L-methionine in the presence of Na+ or K+ was the same (P≥ 0.05). Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 3-5 membrane preparations. The bars labelled with different letters show statistical differences (P < 0.05).

Kinetic analysis of the Na+-independent component

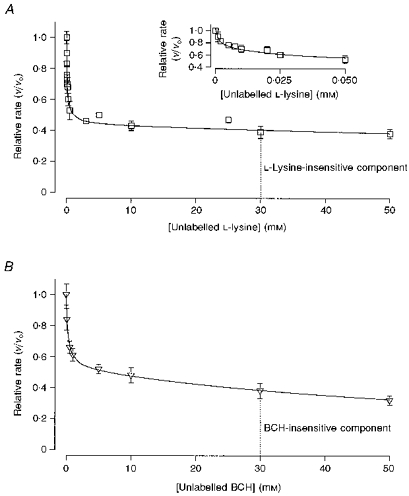

To simplify the kinetic analysis, L-methionine self-inhibition experiments (50 μM labelled substrate) were done in the presence of specific inhibitors such as BCH or L-lysine. The results (Fig. 5A and Table 4A) indicate that the best fit for the BCH-insensitive component was obtained by considering a model including two transport systems, one, system a, with low Michaelis constant (Km,a= 16 ± 0.4 μM) and low capacity (Vmax,a= 1.7 ± 0.2 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) and the other, system b, with high Km (Km,b= 3.0 ± 0.3 mM) and high Vmax (Vmax,b= 465 ± 4.3 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1). In the presence of L-lysine, the best fit shows the occurrence of a single transport mechanism (Km,c= 1.29 ± 0.08 mM and Vmax,c= 229 ± 5.0 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1). Fa/b and Fc/b values indicate that system b contributes more than system a, and that system c contributes more than system b to L-methionine uptake.

Figure 5. Relative transport rates of L-[14C]methionine (50 μM) influx under a 100 mM zero-trans KSCN gradient in the presence of varying concentrations of unlabelled L-methionine incubated with (A) or without (B) 10 mM L-lysine (□) or BCH (▿).

The lines of A represent the best fit obtained in the presence of L-lysine (one transport system) or BCH (two transport systems). B shows the curve drawn by inserting the kinetic parameters of Table 4 in eqn (6) (r= 0.998). Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 3-5 membrane preparations. Only s.e.m. that exceed the size of the symbol are shown.

Table 4.

Kinetic constants of l-methionine transport

| KSCN | NaSCN | NaSCN - KSCN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + l-Lysine | + BCH | + l-Lysine | + BCH | + l-Lysine | ||

| A. | Km,a (μm) | — | 16 ± 0.4 | — | 15 ± 4 | — |

| Vmax,a (pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) | — | 1.7 ± 0.2 | — | 2.4 ± 0.3 | — | |

| Km,b (mm) | — | 3.0 ± 0.3 | — | 1.0 ± 0.1 * | — | |

| Vmax,b (pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) | — | 465 ± 4.3 | — | 639 ± 4.9 * | — | |

| Km,c (mm) | 1.29 ± 0.08 | — | 0.75 ± 0.012 * | — | — | |

| Vmax,c (pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) | 229 ± 5.0 | — | 590 ± 1.8 * | — | — | |

| Km,d (mm) | — | — | — | — | 0.64 ± 0.013 | |

| Vmax,d (pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) | — | — | — | — | 391 ± 2.3 | |

| Fa/b | — | 0.65 ± 0.01 | — | 0.25 ± 0.03 * | — | |

| Fc/b | 1.14 ± 0.14 | — | 1.23 ± 0.12 | — | — | |

| B. | Km,a (μm) | — | 2.2 ± 0.3 | — | 2.0 ± 0.3 | — |

| Vmax,a (pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1) | — | 0.13 ± 0.005 | — | 0.10 ± 0.006 | — | |

| Fa/b | — | 0.42 ± 0.08 | — | 0.078 ± 0.015 * | — | |

Kinetic constants were determined under a 100 mm KSCN or NaSCN zero-trans gradient in the presence of varying concentrations of unlabelled l-methionine and with 10 mm l-lysine or BCH. Km (half-saturation constant) were calculated by non-linear regression analysis from the values of relative rates (v/vo). Estimation of the kinetic parameters was performed for 50 μm l-[14C]methionine in the presence of 10 mm l-lysine or BCH (A) and for 0.5 μm l-[3H]methionine in the presence of 10 mm BCH and 0.5 mm NEM (B). Fc/b values were calculated from eqn (7) of Methods using the kinetic constants of the present table. Estimation of Vmax was made by non-linear regression analysis using total influx values (v) and their respective Km values. The asterisks denote statistical differences (P < 0.05) between Na+ and K+ conditions. Each value represents the mean ± s.e.m. of 3-5 membrane preparations.

The Km calculated for system a is lower than the concentration of labelled L-methionine used as substrate, which could lead to miscalculation of its kinetic constants. For this reason, the kinetic analysis of system a was repeated using a 0.5 μM L-[3H]methionine (i.e. lower than the expected Km) and isolating this pathway by the appropriate use of transport inhibitors. System a is able to interact with L-lysine and appears as a high-affinity low-capacity transport mechanism with a low relative contribution to total L-methionine influx. Thus, the high inhibition exerted by NEM (Table 2) suggests the identification of system a with the NEM-insensitive pathway. For this reason, self-inhibition experiments were performed in the presence of 10 mM BCH and 0.5 mM NEM. The results indicate that the influx data fit best to a transport model describing a single transport system with kinetic parameters in the micromolar range (Km,a= 2.2 ± 0.3 μM and Vmax,a= 0.13 ± 0.005 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1; Table 4B), similar to those previously calculated for system a using a 50 μM substrate concentration. Fitting the L-methionine influx in the absence of inhibitors to the curve defined by the previously calculated kinetic constants gave a value for r of 0.998 (Fig. 5B). This confirms the adequacy of the model proposed for L-methionine uptake, consisting of three transport systems.

The inhibition constants for BCH and L-lysine were calculated from 50 μM L-methionine influx in the presence of increasing concentrations of these substrates (Fig. 6A and B and Table 5). The best fit for the L-lysine-sensitive flux was obtained by considering two transport systems (a and b) and the best fit for the BCH-sensitive pathway by considering a single pathway (c).

Figure 6. Relative transport rates of L-[14C]methionine (50 μM) influx in the presence of varying concentrations of unlabelled L-lysine (A) and BCH (B), under a 100 mM zero-trans KSCN gradient.

The lines represent the best fit of the L-lysine-sensitive transport component (two transport systems) and of the BCH-sensitive component (one transport system). Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 3-5 membrane preparations. Only s.e.m. that exceed the size of the symbol are shown.

Table 5.

Inhibition of 50 μm of l-[14C]methionine transport by increasing concentrations of l-lysine and BCH

| K1,a | K1,b | K1,c | Fa/b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Lysine | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.23 ± 0.14 | — | 0.66 ± 0.49 |

| BCH | — | — | 0.26 ± 0.024 | — |

Inhibition constants for l-lysine and BCH were determined under a KSCN zero-trans gradient. Ki (inhibition constant, mm) and the ‘permeability’ ratio Fa/b (eqn (5)) were calculated by non-linear regression analysis from the values of relative rates (v/vo) of the l-lysine- and BCH-sensitive components. Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 3-5 membrane preparations.

Kinetic analysis under a Na+ gradient

The kinetic parameters for L-methionine influx under a NaSCN gradient were calculated from self-inhibition experiments in the presence of 10 mM BCH or L-lysine (Fig. 7A and Table 4A). With BCH present in the incubation medium, the best fit was for two transport systems, one with low Km and low capacity (Km,a= 15 ± 4 μM and Vmax,a= 2.4 ± 0.3 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1), with similar kinetic values when compared with K+ results, and the other with high Km and high capacity (Km,b= 1 ± 0.1 mM and Vmax,b= 639 ± 4.9 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1). In the presence of L-lysine, the best fit was obtained for a single transport mechanism showing a Km that is slightly smaller than that obtained in KSCN conditions and having a 2.5-fold higher Vmax (Km,c= 0.75 ± 0.012 mM and Vmax,c= 590 ± 1.8 pmol (mg protein)−1 2 s)−1). For a more accurate estimate of kinetic constants of the high-affinity pathway, the analysis was repeated using a lower substrate concentration (0.5 μM), and Table 4B shows that the same qualitative results were obtained.

Figure 7. Relative influx of L-methionine under a 100 mM zero-trans NaSCN gradient.

A, relative transport rates of L-[14C]methionine (50 μM) influx in the presence of varying concentrations of unlabelled L-methionine and 10 mM L-lysine (□) or BCH (▿). The lines represent the best fit obtained in the presence of L-lysine (one transport system) or BCH (two transport systems). B, relative transport rates of Na+-dependent, BCH-sensitive influx calculated by subtracting the values obtained in the absence of Na+ (Fig. 5A) from those obtained under a Na+ gradient (Fig. 7A). The best fit obtained was for a single transport system. Each value represents the mean ±s.e.m. of 3-5 membrane preparations. Only s.e.m. that exceed the size of the symbol are shown.

The existence of a Na+-dependent transport system sensitive to BCH (suggested by cis-inhibition experiments) was also studied. To isolate this transport component from other pathways, the L-lysine-insensitive L-methionine influx obtained in Na+-free conditions was subtracted from the flux obtained under a Na+ gradient. The results (Fig. 7B and Table 4A) indicate the presence of a Na+-dependent transport activity mediated by a single transport system (best fit: Km,d= 0.64 ± 0.013 mM, Vmax,d= 391 ± 2.3 pmol (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1).

DISCUSSION

The uptake of L-methionine across the luminal membrane of the jejunum is a complex process involving multiple pathways. Passive diffusion is low compared with mediated mechanisms, with a KD value of 82 nl (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1, similar to the values obtained by Brachet & Puigserver (1989) in BBMVs of the chicken jejunum and significantly lower than the data reported by Wilson & Webb (1990) in bovine jejunal BBMVs.

When Na+ is present, L-methionine uptake shows an overshoot which is quantitatively similar to those obtained by Brachet & Puigserver (1989) in the chicken jejunum and ileum. Their peak values occurred, however, some time later than in the present study, probably because their experiments were carried out at a lower incubation temperature. The properties and relevance of Na+/L-methionine uptake will be discussed later.

The kinetic analysis indicates that two of the transport pathways used by L-methionine have transport properties similar to those previously described for L-lysine transport; thus, the Km values calculated for L-methionine (2.2 μM for system a and 3.0 mM for system b) are in the range of the inhibition constants calculated for L-methionine in L-lysine transport experiments across pathways identified as systems bo, + and y+ (Torras-Llort et al. 1996, whose Ki values were 55 μM for the bo, + -like system and 3.4 mM for the y+-like system). Also, the Ki values obtained here for L-lysine (13 μM for system a and230 μM for system b) are similar to the Km previously calculated for L-lysine transport (3 μM for the bo, + -like system and 164 μM for the y+-like system). Finally, Vmax values for L-methionine indicate that system a is a low-capacity transport system, whereas system b is a high-capacity transport mechanism (Vmax,a, 0.13 and Vmax,b, 465 pmol L-methionine (mg protein)−1 (2 s)−1, respectively).

Cis-inhibition experiments performed under a K+ gradient facilitate the distinction of two components, one sensitive to BCH and the other sensitive to L-lysine. Furthermore, the L-lysine-sensitive component can be subdivided into two pathways, one sensitive to NEM and the other sensitive to L-glutamine. The main candidate for the NEM-sensitive transport activity is system y+ (Devés, Angelo & Chávez, 1993), although some reactivity of system asc to NEM has also been described by Vadgama & Christensen (1985). However, system asc shows weak affinity for bulky amino acids (Fincham, Mason & Young, 1985; Devés et al. 1992) and L-methionine transport was completely inhibited by L-phenylalanine, both in the absence and in the presence of BCH (Fig. 3 and Table 2), which rules out an asc-like pathway. The NEM-insensitive, L-glutamine-sensitive transport activity may be mediated by system bo, + or by system y+L. Both mechanisms are able to interact with L-glutamine and show high affinity for cationic and neutral amino acids (Bertran et al. 1992; Devés et al. 1993). However, the inhibition exerted by L-cystine suggests the identification of this pathway with a bo, + -like system rather than a y+L activity. The coincidences observed between L-methionine and L-lysine transport in our membrane preparations, together with the results obtained in cis-inhibition experiments all point to identification of systems a and b with a bo, + - and y+-like activity, respectively (Bertran et al. 1992; Devés et al. 1993). This conclusion also agrees with the observations of Thwaites, Markovich, Murer & Simmons (1996), who found that L-lysine transport in the apical membrane of Caco-2 cells is mediated by systems bo, + and y+.

The third mechanism of L-methionine uptake (system c) is Na+ independent and has a Km for L-methionine and a Ki for BCH similar to those reported in the small intestine for system L (Stevens, Ross & Wright, 1982; Sanchís, Alemany & Remesar, 1994). The presence of an activity compatible with system L was suspected, together with systems bo, + and y+, in the brush-border membrane of epithelial OK cells (Mora et al. 1996). The identity of system c is discussed below.

Results of L-methionine influx under an increasing Na+ gradient suggest that this amino acid is also transported by Na+-dependent mechanisms. In the presence of Na+, substrate influx shows no interaction with MeAIB and is strongly inhibited by L-phenylalanine, thus excluding the participation of systems A and ASC (Barker & Ellory, 1990; McGivan & Pastor-Anglada, 1994). Cis-inhibition experiments also show that BCH can interact with the Na+-dependent flux, a property which is shared by systems Bo, + and B (Stevens et al. 1982; Van Winkle, Christensen & Campione, 1985). However, two properties weaken the participation of system Bo, + in L-methionine uptake: first, L-lysine transport in this epithelium is not Na+ dependent (Torras-Llort et al. 1996) and, second, the Na+-dependent L-methionine transport is insensitive to L-lysine (Fig. 4). These results differ from those of Chen, Zhu & Hu (1994) in Caco-2 cells since they describe apical Na+-dependent methionine transport as a property of systems ASC and B0, +.

The kinetic results obtained under a Na+ gradient further confirm the existence of at least three different transport systems. Two of them can be identified with the previously described systems labelled a and b. System a, identified with system bo, +, is not affected by the presence of Na+, an effect that further excludes system y+L because one of its properties is a marked (e.g. 30-fold) increase in the affinity for neutral amino acids when K+ is replaced by Na+, as shown by Devés et al. (1992). System b, a y+-like low-affinity high-capacity transport system, shows lower Km and higher Vmax in the presence of Na+. For L-lysine, the effect on Vmax has been attributed to a membrane potential effect due to the different permeability of the membrane to these cations (Torras-Llort et al. 1998). The results obtained for neutral amino acids, such as L-methionine, suggest that this effect may be attributed to the charge associated with the y+ protein carrier as proposed by Eleno, Devés & Boyd (1994).

Since the chicken intestine y+ system differs from the y+ activity described in other tissue preparations in its high capacity to transport L-methionine in the absence of Na+ (White, 1985; Magagnin et al. 1992; Thwaites et al. 1996), we are led to propose a more specific name for this transport activity. We suggest the name y+m in order to reflect this significant ability to transport L-methionine.

As stated before, the kinetic analysis carried out under a Na+ gradient supports the participation of a third mechanism, named system c, specific for neutral amino acids. This system can transport L-methionine both in the presence and in the absence of Na+ albeit with different kinetic constants. Maenz & Patience (1992) and Maenz & Engele-Schaan (1996) have reported the existence in the chicken intestine of such a transport system, which was identified as system B. These authors observed that Na+ has an activating role exerting a ‘velocity effect’ (i.e. a significant increase on Vmax without affecting Km). Our results for system c, showing a slight decrease in Km (1.5-fold) and a 2.5-fold increase in Vmax, would support the results described by these authors.

Another explanation for the kinetic results obtained under a Na+ gradient is that the activity attributed to a third transport system may correspond to two overlapping transport systems, with half-saturation constants too similar to be distinguished only by kinetic means. Taking into account this hypothesis, the best candidates would be systems L and B. The coincidence of both transport systems in the apical membrane of the intestine, both able to transport neutral amino acids, has already been described by Stevens et al. (1982), Malo (1991) and Sanchís et al. (1994). Systems L and B show similar substrate specificity and sensitivity to BCH (Stevens, Kaunitz & Wright, 1984), and the Michaelis constants reported for both systems are in the millimolar range (Stevens et al. 1982; Bulus, Abumrad & Ghishan, 1989; Sanchís et al. 1994). Our kinetic analysis indicates that the Na+-dependent BCH-sensitive component of L-methionine uptake can be best fitted to a single mediated transport system, with a Km in the range of the value obtained for system c in the presence of Na+. A different approach would be needed to distinguish two transport systems with coinciding kinetic properties.

The simultaneous existence of systems L and B would also agree with the kinetic results obtained under a Na+ gradient, because the activity of system L in the absence of Na+ and the incorporation of system B under the Na+ gradient would induce a significant increase in Vmax,c without affecting the Km value. Moreover, the Na+ dependence (Fig. 2) and the effect of the membrane potential (Table 1) are properties characteristic of a transport mechanism such as system B. Therefore, although the above-described results are not conclusive in distinguishing between one or two transport systems accounting for the BCH-sensitive component under a Na+ gradient, the most plausible explanation seems to be the simultaneous presence of systems bo, +, y+m and L-like accounting for the Na+-independent component, and the additional participation of a B-like system, when a Na+ gradient is imposed.

When a model consisting of two or more transport systems is considered, it is interesting to establish their relative contribution to total substrate influx. The contribution of the different transport systems to L-methionine transport, across the apical membrane of the chicken jejunum, could be assessed from the ‘permeability’ ratios at low substrate concentrations and from the relative maximum rates at high substrate concentrations (Devés et al. 1992). At low substrate concentrations and in the presence of Na+, system y+m contributes 44 % to total L-methionine uptake, which is similar to that calculated for the B-like system (42 %) but higher than for system bo, + and the L-like system (2 % and 12 %, respectively). At high substrate concentrations system y+m contributes 53 % to L-methionine uptake. The L-like system contributes 17 % and the B-like system 30 %. In these conditions, the contribution of system bo, + is extremely low (around 0.01 %).

The contribution of all these transport systems to L-methionine absorption by the intestine can be modified by the presence of cationic amino acids that may bind to systems bo, + and y+m. In these conditions, the activity of the remaining pathway(s) would be of considerable importance to assure L-methionine uptake. Moreover, the intracellular concentration of neutral amino acids may induce hetero-exchange activity across system bo, +. This system has been described in injected oocytes as an obligatory hetero-exchanger that is well endowed for cationic amino acid uptake and neutral amino acid efflux (Chillarón et al. 1996). Preliminary experiments performed in our laboratory indicate that the chicken jejunal bo, + system shows hetero-exchange activity for neutral and cationic amino acids. These functional characteristics could magnify the physiological role of a bo, + activity in the brush-border membrane of the chicken intestine. Further studies are under way to determine the regulation of the different transport systems by dietary L-methionine.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank IRTA-Mas Bové (Generalitat de Catalunya) for their support in the design and preparation of the diet. This work was supported by grant ALI96-910 from the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica, Spain. J.F.S.-G. was a holder of a Formació d'Investigadors Grant from Generalitat de Catalunya. M.T.-L. is a research fellow of the Recerca i Docència program, Universitat de Barcelona.

References

- Baker DH. Utilization of isomers and analogs of amino acids and other sulfur-containing compounds. Progress in Food and Nutrition Science. 1986;10:133–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GA, Ellory JC. The identification of neutral amino acid transport systems. Experimental Physiology. 1990;75:3–26. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1990.sp003382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berteloot A. Characteristics of glutamic acid transport by rabbit intestinal brush border membrane vesicles. Effect of Na+-, K+- and H+-gradients. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1984;775:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran J, Werner A, Moore ML, Stange G, Markovich D, Biber J, Testar X, Zorzano A, Palacín M, Murer H. Expression cloning of a cDNA from rabbit kidney cortex that induces a single transport system for cystine and dibasic and neutral amino acids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:5601–5605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachet P, Puigserver A. Na+-independent and nonstereospecific transport of 2-hydroxy-4-methylthiobutanoic acid by brush border membrane vesicles from chick small intestine. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1989;94B:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(89)90027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulus NM, Abumrad NN, Ghishan FK. Characteristics of glutamine transport in dog jejunal brush-border membrane vesicles. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:G80–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.257.1.G80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campione AL, Haghighat N, Gorman J, Van Winkle LJ. Choline inhibition of amino acid transport in preimplantation mouse blastocysts. Federation Proceedings. 1987;46:2031. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhu Y, Hu M. Mechanisms and kinetics of uptake and efflux of L-methionine in an intestinal epithelial model (Caco-2) Journal of Nutrition. 1994;124:1907–1916. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.10.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chillarón J, Estévez R, Mora C, Wagner CA, Suessbrich H, Lang F, Gelpí JL, Testar X, Busch AE, Zorzano A, Palacín M. Obligatory amino acid exchange via systems bo, +-like and y+L-like. A tertiary active transport mechanism for renal reabsorption of cystine and dibasic amino acids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:17761–17770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17761. 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devés R, Angelo S, Chávez P. N-Ethylmaleimide discriminates between two lysine transport systems in human erythrocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;468:753–766. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devés R, Chávez P, Boyd CAR. Identification of a new transport system (y+L) in human erythrocytes that recognizes lysine and leucine with high affinity. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;454:491–501. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Mello JPF. Amino Acids in Farm Animal Nutrition. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eleno N, Devés R, Boyd CAR. Membrane potential dependence of the kinetics of cationic amino acid transport systems in human placenta. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;479:291–300. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham DA, Mason DK, Young JD. Characterization of a novel Na+-independent amino acid transporter in horse erythrocytes. Biochemical Journal. 1985;227:13–20. doi: 10.1042/bj2270013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furesz TC, Moe AJ, Smith CH. Lysine uptake by human placental microvillous membrane, comparison of system y+ with basal membrane. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C755–761. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.3.C755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg GR, Lerner J. The effect of preloaded amino acids on lysine and homoarginine transport in chicken small intestine. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1973;44A:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(73)90364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler M, Acuto O, Storelli C, Murer H, Müller M, Semenza G. A modified procedure for the rapid preparation of efficiently transporting vesicles from small intestinal brush border membranes. Their use in investigating some properties of D-glucose and choline transport systems. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1978;506:136–154. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmich GA, Randles J, Restrepo D, Montrose M. A new method for the determination of relative permeabilities in isolated cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1985;248:C399–405. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1985.248.5.C399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight C, Dibner J. Comparative absorption of 2-hydroxy-4-(methylthio)-butanoic acid and L-methionine in the broiler chick. Journal of Nutrition. 1984;114:1716–1723. doi: 10.1093/jn/114.11.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner J, Sattelmeyer P, Rush R. Kinetics of methionine influx into various regions of chicken intestine. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1975;50A:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0010-406x(75)80211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivan JD, Pastor-Anglada M. Regulatory and molecular aspects of mammalian amino acid transport. Biochemical Journal. 1994;299:321–334. doi: 10.1042/bj2990321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenz DD, Engele-Schaan CM. Methionine and 2-hydroxy-4-methylthiobutanoic acid are transported by distinct Na+-dependent and H+-dependent systems in the brush border membrane of the chick intestinal epithelium. Journal of Nutrition. 1996;126:529–536. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.2.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenz DD, Patience JF. L-Threonine transport in pig jejunal brush border membrane vesicles. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:22079–22086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magagnin S, Bertran J, Werner A, Markovich D, Biber J, Palacín M, Murer H. Poly(A)+ from rabbit intestinal mucosa induces bo, + and y+ amino acid transport activities in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:15384–15390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailliard ME, Stevens BR, Mann GE. Amino acid transport by small intestinal, hepatic, and pancreatic epithelia. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:889–910. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90466-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malo C. Multiple pathways for amino acid transport in brush border membrane vesicles isolated from the human fetal small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1644–1652. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora C, Chillarón J, Calonge MJ, Forgo J, Testar X, Nunes V, Murer H, Zorzano A, Palacín M. The rBAT gene is responsible for L-cystine uptake via the bo, +-like amino acid transport system in a ‘renal proximal tubular’ cell line (OK cells) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:10569–10576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10569. 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky GJ, Ransnas LA. Fitting curves to data using nonlinear regression, a practical and nonmathematical review. FASEB Journal. 1987;1:365–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchís D, Alemany M, Remesar X. L-Alanine transport in small intestine brush-border membrane vesicles of obese rats. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1192:159–166. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano-García JF, Torras-Llort M, Planas JM, Ferrer R, Moretó M. Na+-independent transport of L-methionine in brush-border membrane vesicles of chicken jejunum. Physiological Research. 1996;45:12. P. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens BR, Kaunitz JD, Wright EM. Intestinal transport of amino acids and sugars: advances using membrane vesicles. Annual Review of Physiology. 1984;46:417–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.46.030184.002221. 10.1146/annurev.ph.46.030184.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens BR, Ross HJ, Wright EM. Multiple transport pathways for neutral amino acids in rabbit jejunal brush border vesicles. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1982;66:213–225. doi: 10.1007/BF01868496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thwaites DT, Markovich D, Murer H, Simmons NL. Na+-independent lysine transport in human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1996;151:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s002329900072. 10.1007/s002329900072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torras-Llort M, Ferrer R, Soriano-García JF, Moretó M. L-Lysine transport in chicken jejunal brush border membrane vesicles. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1996;152:183–193. doi: 10.1007/s002329900096. 10.1007/s002329900096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torras-Llort M, Soriano-García JF, Ferrer R, Moretó M. Effect of a lysine-enriched diet on L-lysine transport by the brush border membrane of the chicken jejunum. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:R69–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.1.R69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadgama JV, Christensen HN. Discrimination of Na+- independent transport systems L, T and asc in erythrocytes. Na+ independence of the latter a consequence of cell maturation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:2912–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkle LJ, Christensen HN, Campione AL. Na+-dependent transport of basic, zwitterionic and bicyclic amino acid by a broad-scope system in mouse blastocysts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:12118–12123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MF. The transport of cationic amino acids across the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1985;822:356–374. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(85)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JW, Webb KE. Lysine and methionine transport by bovine jejunal and ileal brush border membrane vesicles. Journal of Animal Science. 1990;68:504–514. doi: 10.2527/1990.682504x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]