Abstract

Recordings were made from a total of sixty-four vagal preganglionic neurones in the dorsal vagal motor nucleus (DVMN) of pentobarbitone sodium anaesthetized rats. The effects of ionophoretic administration of Mg2+ and Cd2+, inhibitors of neurotransmitter release, and the selective NMDA and non-NMDA receptor antagonists (±)-2-amino-5-phosphono-pentanoic acid (AP5) and 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX) on the excitatory actions of the 5-HT3 receptor agonist 1-phenylbiguanide (PBG) were studied.

In extracellular recording experiments, PBG (0-40 nA) increased the firing rate of thirty-five of the thirty-nine neurones tested. The PBG-evoked excitation was attenuated by application of Mg2+ (1-10 nA) in sixteen of seventeen neurones or Cd2+ (2-10 nA) in seven of eight neurones tested. At these low ejection currents neither Mg2+ nor Cd2+ altered baseline firing rates and Mg2+ had no effect on the excitations evoked by DL-homocysteic acid (n = 4), NMDA (n = 4) or (AMPA; n = 2).

Ionophoresis of AP5 (2-10 nA), at currents which selectively inhibited NMDA-evoked excitations, attenuated PBG-evoked excitations in all eight neurones tested. DNQX (5-20 nA), at currents which selectively inhibited AMPA-evoked excitations, also attenuated PBG-evoked excitations (n = 3).

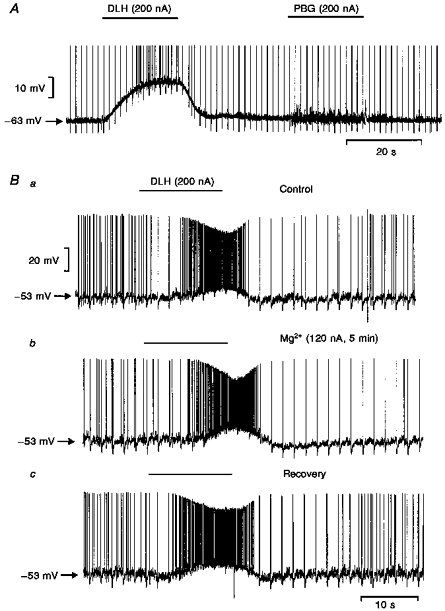

Intracellular activity was recorded in nine DVMN neurones. In six neurones ionophoretic application of PBG (10-200 nA) depolarized the membrane and increased firing rate whilst in the other three neurones, PBG had no effect on membrane potential though it increased synaptic noise (n = 3) and firing rate (n = 2). In all six neurones tested, ionophoresis of Mg2+ (10-120 nA) attenuated the PBG-evoked increases in synaptic noise and firing rate.

In conclusion, the data are consistent with the hypothesis that 5-HT3 receptor agonists activate DVMN neurones partly by acting on receptors located at sites presynaptic to the neurones. Activation of these receptors appears to facilitate release of glutamate, which, in turn, acts on postsynaptic NMDA and non-NMDA receptors to activate the neurones.

Vagal preganglionic neurones have been localized in both the dorsal vagal motor nucleus (DVMN) and nucleus ambiguus of rats (Izzo, Deuchars & Spyer, 1993). Immunochemical studies have demonstrated that both regions are densely innervated by 5-HT immunoreactive terminals (Steinbusch, 1981; Sykes, Spyer & Izzo, 1994) and 5-HT-containing terminal boutons have been shown to make synaptic contact with vagal preganglionic neurones (Izzo et al. 1993). This serotonergic innervation of the dorsal medulla arises in part from neurones in the mid-line raphe nuclei (Schaffar, Kessler, Bosler & Jean, 1988) and from vagal sensory afferents (Nosjean et al. 1990; Sykes et al. 1994).

5-HT can have different effects on neuronal activity due to actions on multiple 5-HT receptor subtypes (see Hoyer et al. 1994). In the DVMN region, binding sites for 5-HT1A (Pazos & Palacios, 1985), 5-HT2 (Pazos, Cortes & Palacios, 1985) and 5-HT3 (Pratt & Bowery, 1989; Leslie, Reynolds & Newberry, 1994) receptor ligands have been visualized by autoradiographic techniques. In an in vivo study in rats ionophoretic application of 5-HT or a selective 5-HT3 receptor agonist, 1-phenylbiguanide (PBG), increased activity of dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones (DVPNs) and these effects could be attenuated by application of selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (Wang, Jones, Ramage & Jordan, 1995; Wang, Ramage & Jordan, 1996). Similarly, in a recent in vitro study, it was demonstrated that 5-HT excites DVPNs by activation of postsynaptic 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors (Brooks & Albert, 1995; Albert, Spyer & Brooks, 1996). However, in addition, these authors also noted an increase in spontaneous EPSPs and IPSPs following application of 5-HT3 receptor ligands, suggesting an additional action on presynaptic receptors.

Binding sites for 5-HT3 receptor ligands in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS)-DVMN region are substantially reduced in number when vagal afferents are denervated, consistent with a location on presynaptic terminals (Pratt & Bowery, 1989; Kidd et al. 1993; Leslie et al. 1994). The present study tested the hypothesis that the excitatory effect of 5-HT3 receptor agonists on DVPNs can be mediated by receptors located at sites presynaptic to the recorded neurones. Consequently, a selective 5-HT3 receptor agonist, PBG, was applied by ionophoresis to antidromically identified DVPNs with or without co-ionophoresis of the competitive blockers of neurotransmitter release, magnesium (Mg2+) and cadmium (Cd2+). A preliminary report of these data has been published (Wang, Ramage & Jordan, 1997).

METHODS

Experiments were performed on thirty-six male Sprague-Dawley rats (280-360 g body weight) anaesthetized with pentobarbitone sodium (60 mg kg−1i.p.). Anaesthesia was supplemented when necessary (6 mg kg−1i.v.). When surgical anaesthesia was attained, a tracheotomy was performed low in the neck and catheters were inserted into the femoral artery, for measurement of blood pressure, and vein, for administration of supplemental anaesthetics and drugs. Arterial blood and tracheal pressures were measured with pressure transducers (model P23Db, Statham, Hato Rey, PR, USA). A lead II ECG was recorded, amplified and filtered (NL 100, 104A, 125 modules; NeuroLog System, Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, UK) by leads attached to the limbs of the rats. Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37°C with a Harvard homeothermic blanket system (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA, USA). Animals were ventilated with O2-enriched room air and positive end expiratory pressure (1 cmH2O) using a positive pressure ventilator (Harvard rodent ventilator, model 683). End-tidal CO2 was continuously measured using a fast response CO2 meter (model FM1, The Analytical Development Company Ltd, Hoddesdon, Herts, UK) and maintained close to 4 %. Arterial blood samples were regularly taken and blood gases and pH monitored with a pH-blood gas analyser (model 238, Ciba Corning Diagnostics Ltd, Halstead, UK). Blood gas variables were maintained in the following ranges: PO2, 90-130 mmHg; PCO2, 40-50 mmHg; pH 7.3-7.4 by slow i.v. infusions of sodium bicarbonate (1.0 M) or adjustments of the respiratory pump.

Animals were fixed in a stereotaxic frame and the right vagus nerve was dissected free from the sympathetic trunk and placed on bipolar silver electrodes for electrical stimulation (1 Hz, 2-12 V, 1.0 ms) with a digital programmer (Master 8, AMPI, Intracell Ltd, Royston, Herts, UK) and isolated stimulator (Digitimer DS2). To expose the caudal brainstem in the region of the DVMN the nuchal muscles were removed from the back of the neck, the occipital bone opened and the dura overlying the brainstem cut and reflected laterally. To access the DVMN, in some experiments it was necessary to retract the cerebellum rostrally. During the intracellular recordings, the animals were neuromuscularly blocked using gallamine triethiodide (Flaxedil, May & Baker Ltd, Eastbourne, UK; initially 6 mg, supplemented with 2 mg when necessary). During neuromuscular blockade, the depth of anaesthesia was assessed by monitoring the stability of the arterial blood pressure and heart rate and the cardiovascular responses to pinching the paws. In addition, the animals were allowed to recover periodically from the effects of the neuromuscular block. At the end of each experiment the animals were killed by overdose of the anaesthetic agent.

Protocol

Extracellular recordings

These were made from brainstem neurones using five- or seven-barrelled microelectrodes (tip diameter, 3-5 μm) made from borosilicate glass (GC 150F-10, Clarke Electromedical, Reading, UK). The recording barrel contained 4 M sodium chloride, and the other barrels contained Pontamine Sky Blue dye and a selection of the drugs used in this study. Between the drug ejection periods, a retaining current of 8-20 nA was applied to each drug barrel. Neuronal recordings were amplified × 5000 (Dagan 2400, Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, MN, USA) and filtered (0.1-3 kHz). Vagal preganglionic neurones in the DVMN were identified using standard criteria of antidromic activation, including constant latency of the responses to electrical stimulation of the cervical vagus nerve and collision of the antidromically evoked response with appropriately timed on-going activity (see Fig. 1 in Wang et al. 1995). The characteristics of the on-going activity of these neurones, their synaptic inputs and location have been described previously (Wang et al. 1995; Jones, Wang & Jordan, 1998). Drugs were applied in the vicinity of identified neurones by ionophoresis (NeuroPhore, Medical Systems, Digitimer Ltd). Neurones with no on-going activity were induced to fire by application of low currents (0-20 nA) of an excitant amino acid (DL-homocysteic acid (DLH), NMDA or (±)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA)). When the neuronal firing rate was steady, the effects of the agonist and/or antagonist drugs given alone and/or together were then tested. In all experiments possible current artefacts were overcome using the automatic current balancing available on the NeuroPhore System.

Intracellular recordings

These were obtained from DVPNs using a combined electrode made from single-barrelled intracellular recording electrode glued to a five-barrelled ionophoresis electrode as described by Lalley, Bischoff & Richter (1994). The recording electrodes, filled with 2 M potassium acetate, had in vitro resistances between 50 and 70 MΩ. The multibarrelled electrodes had tip diameters of 5-7 μm and were positioned 40-80 μm behind the tip of the recording electrode. Following successful penetration, cells were identified as dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones by the constant latency of the evoked action potential to cervical vagal stimulation and collision testing. Membrane potentials were recorded using an Axoclamp-2B amplifier (Axon Instruments). When the membrane potential had stabilized, the effects of ionophoretic application of PBG, DLH, NMDA and Mg2+ on the membrane potential and the neuronal firing were assessed.

Analysis of data

Arterial blood pressure, tracheal pressure, ECG and neuronal activity were recorded on videotape via a digital interface (Instrutech, VR-100A, Digitimer Ltd). Off-line analysis of the recorded data was made using commercially available software (Spike 2 and Signal Averager, Cambridge Electronic Design (CED), Cambridge, UK) on a PC (Viglen 486 DX2 66) accessed via an A-D interface (CED 1401plus). Single unit activity was discriminated on a window discriminator (Digitimer D130) and displayed as a rate histogram. Baseline neuronal firing rate and the peak firing rate during drug application were counted as the mean rate over 10-20 s periods (given as means ± s.e.m.), since DVMN neurones fired at a regular rate (Jones et al. 1998). Agonist drugs were classed as evoking excitation if activity was increased by at least 20 % of baseline. Ligands were classed as attenuating the responses if they reduced the evoked response by at least 20 %. The mean neuronal firing rate was compared before (control) and during drug application using Student's paired t test except for the effect of high Mg2+ application on baseline firing rate which was tested with Student's unpaired t test.

Drugs and solutions

The drugs were freshly made up in the following quantities and their pH was adjusted by addition of drops of either 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH: PBG (10 mM in 1 mM NaCl, pH 10.6) from Aldrich Chemical; AMPA (20 mM in 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.5) from Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK; (±)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5, 20 mM in 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.5) from Tocris Cookson; 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX, 2.5 mM in 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.5) from Research Biochemicals International; MgCl2 (1 M in distilled water, pH 4.5); CdCl2 (100 mM in distilled water, pH 4.5); N- methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA, 20 mM in 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.5) from Sigma; DLH (100 mM in distilled water, pH 8.5) from Sigma; granisetron (10 mM in 1 mM NaCl, pH 4), a gift from SmithKline Beecham, Harlow, UK; Pontamine Sky Blue dye (20 mg ml−1, dissolved in 0.5 M sodium acetate) from BDH.

RESULTS

Extracellular recordings

Extracellular activity was recorded from a total of fifty-five DVPNs. Their ongoing and evoked activities, and the calculated conduction velocities of their axons were the same as those described in previous publications from this laboratory (Wang et al. 1995, 1996; Jones et al. 1998).

Effects of Mg2+ and Cd2+ on PBG-evoked excitation in DVPNs

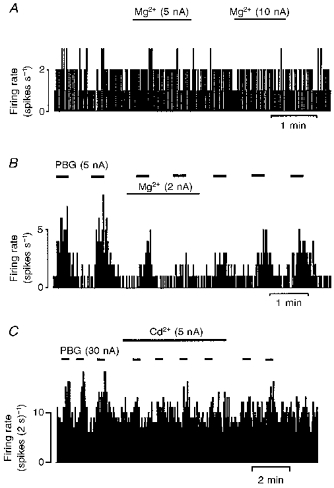

Ionophoretic application of PBG (0-40 nA) increased the firing rate of thirty-five of the thirty-nine (89 %) DVPNs tested (Figs 1B, 1C, 3A and 5), which was similar to that described previously (Wang et al. 1996). The effect of Mg2+ on PBG-evoked responses was tested in seventeen of the DVPNs activated by PBG. Ionophoretic application of low currents of Mg2+ (1-10 nA, 2-5 min) selectively attenuated PBG-evoked excitation in sixteen (94 %) of these DVPNs (Figs 1B and 3A). The excitation evoked by PBG in the other neurone was unaffected by Mg2+ (5 nA, 3 min). As a group, Mg2+ reduced the PBG-evoked excitation from 4.59 ± 0.68 to 2.32 ± 0.35 Hz (P < 0.001, n = 17, Student's paired t test) whereas the baseline firing rate was unaltered (1.73 ± 0.3 vs. 1.70 ± 0.29 Hz) (Table 1A).

Figure 1. Effects of Mg2+ and Cd2+ on baseline firing rate and PBG-evoked excitations.

Continuous ratemeter records of the activity of three vagal preganglionic neurones during application of the selective 5-HT3 receptor agonist phenylbiguanide (PBG), Mg2+ and Cd2+ with the stated ionophoretic currents for the times indicated by the bars. Mg2+ has no effect on a stable DL-homocysteic acid (DLH)-evoked firing rate of the neurone (A). Excitations evoked by PBG are attenuated by Mg2+ (B) and Cd2+ (C).

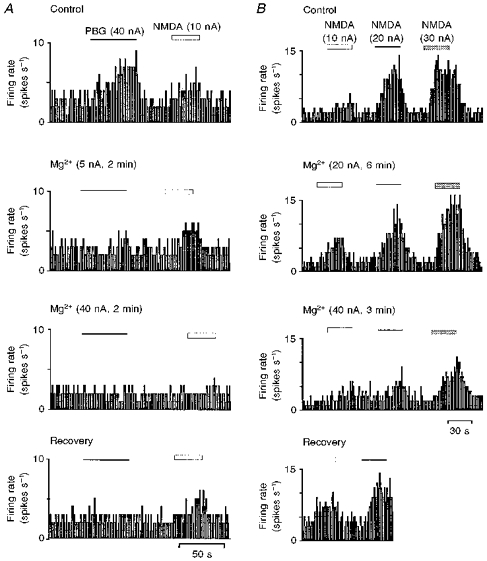

Figure 3. Effects of low and high current application of Mg2+ on the PBG- and NMDA-evoked excitations.

Ratemeter records of the activity of a dorsal vagal preganglionic neurone during application of PBG or NMDA with Mg2+ at the stated ionophoretic currents for the times indicated by the bars. A, application of low currents of Mg2+ (5 nA) differentially attenuated PBG-evoked excitation compared with the NMDA response, but at higher currents of Mg2+ (40 nA) both PBG- and NMDA-evoked excitation were blocked. B, different levels of excitation evoked by NMDA (10, 20 and 30 nA) were all attenuated by application of Mg2+ at 40 nA but were not affected by lower currents of Mg2+ (20 nA).

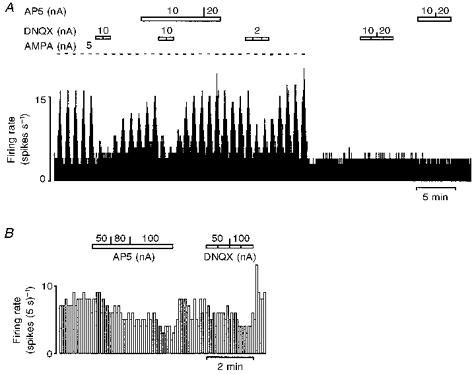

Figure 5. Effect of selective glutamate receptor antagonists on responses evoked by PBG.

Continuous ratemeter records of activity of two different vagal preganglionic neurones during application of PBG and selective excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists with the stated ionophoretic currents for the times indicated by the bars. A, excitatory responses evoked by application of PBG before, during and after application of low currents of the selective NMDA receptor antagonist AP5. B, excitatory responses evoked by application of PBG before, during and after application of low currents of the selective non-NMDA receptor antagonist DNQX.

Table 1.

Effects of ionophoretic application of low currents of Mg2+, Cd2+, AP5 and DNQX on the baseline firing rate and the excitation evoked by PBG, NMDA, and DLH (A) and high currents of Mg2+ on the baseline firing rate (B) in DVMN neurones

| A. Effects of low Mg2+, Cd2+, AP5 and DNQX currents | B. Effects of high Mg2+ currents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firing rate | ||||||

| Treatment | Baseline (Hz) | PBG (Hz) | NMDA (Hz) | DLH (Hz) | Treatment | Baseline firing rate (Hz) |

| Control | 1.73 ± 0.30 | 4.59 ± 0.68 | 6.80 ± 1.27 | 6.25 ± 2.77 | Control | 2.72 ± 0.13 |

| Mg2+ (1-10 nA) | 1.70 ± 0.29 | 2.32 ± 0.35* | 6.66 ± 1.26 | 7.85 ± 3.69 | n | 4 |

| n | 17 | 17 | 4 | 4 | Mg2+ (5 nA) | 2.86 ± 0.19 |

| Control | 2.69 ± 0.83 | 6.79 ± 1.72 | – | – | n | 4 |

| Cd2+ (2-10 nA) | 2.55 ± 0.85 | 3.91 ± 0.95* | – | – | Mg2+ (10 nA) | 2.40 ± 0.13 |

| n | 8 | 8 | n | 4 | ||

| Control | 1.50 ± 0.44 | 2.57 ± 0.58 | – | – | Mg2+ (20 nA) | 2.23 ± 0.03* |

| AP5 (2-10 nA) | 1.67 ± 0.49 | 1.62 ± 0.60* | – | – | n | 3 |

| n | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Control | 2.37 ± 0.90 | 5.05 ± 0.45 | – | – | ||

| DNQX (5-20 nA) | 2.50 ± 1.17 | 2.78 ± 0.72* | – | – | ||

| n | 3 | 3 | ||||

P < 0.05 (Student's paired or unpaired t test) between control and ligand. n, number of neurones.

Effects of Mg2+ on excitatory amino acid-evoked excitation in DVPNs

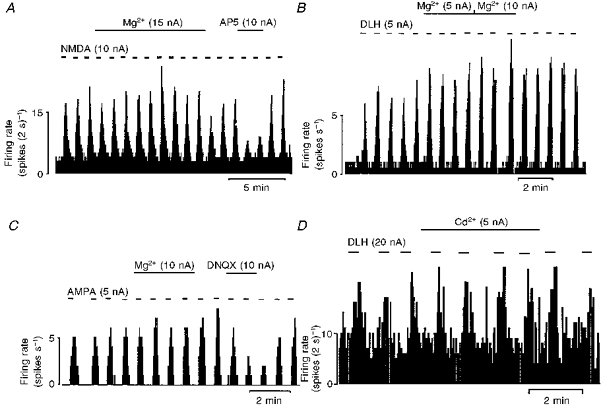

In addition to an inhibitory effect on neurotransmitter release, Mg2+ is also known to produce a voltage-dependent block of NMDA receptors (Mayer et al. 1984). As low doses of DLH, NMDA or AMPA were used to evoke baseline firing in most of the DVPNs recorded extracellularly, it is possible that the apparent attenuation of the PBG-evoked excitation produced by Mg2+ was due to an action at postsynaptic NMDA receptors. Although the data from Cd2+ applications make this an unlikely explanation for the observed results, the interaction between Mg2+ (low and high currents) and glutamate receptor agonists was studied directly. Ionophoretic application of short pulses of NMDA (2-10 nA), DLH (4-20 nA) or AMPA (5-10 nA) evoked bursts of firing with a fast onset and fast recovery in all the neurones tested (Figs 2 and 3). In ten of sixteen neurones in which the PBG-evoked excitation was attenuated by low currents of Mg2+ (1-10 nA), ionophoretic application of Mg2+ at similar ejection currents and duration was also tested on either NMDA (n = 4)-, DLH (n = 4)- or AMPA (n = 2)-evoked excitations. Ionophoretic application of Mg2+ had no effect on the NMDA-evoked excitation (6.80 ± 1.27 vs. 6.66 ± 1.26 Hz) (Figs 2A and 3; Table 1A) while in the same four neurones, the PBG-evoked excitations were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced from 5.98 ± 1.30 to 3.41 ± 0.71 Hz. Similarly, in another four neurones Mg2+ had no effect on DLH-evoked excitations (6.25 ± 2.77 vs. 7.85 ± 3.69 Hz) (Fig. 2B; Table 1A) but significantly inhibited the PBG-evoked excitations from 3.09 ± 0.78 to 1.43 ± 0.55 Hz (P < 0.05). Finally, in two DVPNs, ionophoretic application of Mg2+ had no effect on the AMPA-evoked excitations (4.8 vs. 4.5 and 11.8 vs. 11.0 Hz) (Fig. 2C) but reduced the PBG-evoked excitations (2.85 vs. 1.0 and 12.2 vs. 4.4 Hz).

Figure 2. Effects of Mg2+ and Cd2+ on the glutamate receptor ligand-evoked responses.

Continuous ratemeter records of the activity of vagal preganglionic neurones during application of Mg2+, Cd2+ and glutamate receptor agonists and antagonists with the stated ionophoretic currents for the times indicated by the bars. Excitatory responses evoked by NMDA were unaffected by Mg2+ but attenuated by application of the selective NMDA receptor antagonist (±)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5, A) whereas the responses evoked by the non-NMDA receptor agonist (±)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) were unaffected by Mg2+ but attenuated by application of the selective non-NMDA receptor antagonist 6,7-dinitro-quinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX, C). Excitations evoked by DLH were unaffected by Mg2+ (B) or Cd2+ (D).

In two DVPNs in which Mg2+ at low ejection currents (1-10 nA) attenuated the PBG-evoked excitation but not the NMDA-evoked excitation, the effect of higher ejection currents of Mg2+ (20-40 nA) on the NMDA-evoked excitation was studied. Increasing the ejection current of Mg2+ to 20 or 40 nA, further attenuated the PBG-evoked excitation and, at the same time, the NMDA-evoked excitation was also attenuated (Fig. 3).

Effects of Mg2+ and Cd2+ on the excitability of DVPNs

The effects of ionophoretic application of low currents of Mg2+ (0-10 nA, 30-60 s) on the baseline firing rate was studied in thirty-four DVPNs. In twenty-three neurones ionophoretic application of Mg2+ at low current (0-10 nA) had no effect on the baseline firing rate (1.80 ± 0.27 vs. 1.78 ± 0.28 Hz) (Figs 1A, 1B and 3A). Four of these DVPNs were further tested with applications of higher currents of Mg2+ (10-40 nA). Although there was no effect on baseline firing rate at the low current range (5-10 nA) (Fig. 3A), Mg2+ did cause a small but significant (P < 0.05, Student's unpaired t test) decrease in the firing rate when ejection currents were increased to 20 nA in three of the neurones tested (Table 1B).In one neurone, the ejection current was increased to 40 nA which further reduced the neuronal firing (Fig. 3A). Similarly, ionophoretic application of Cd2+ at low current (1-10 nA) had no effect on the baseline firing rate (2.69 ± 0.83 vs. 2.55 ± 0.85 Hz, n = 8) (Table 1A).

In another eleven neurones firing rate markedly increased during application of Mg2+. In this group of eleven DVPNs, seven of eight neurones tested were excited by ionophoretic application of PBG, the other neurone being unaffected. Since Mg2+ altered baseline activity, these eleven neurones were excluded from the data described in the present manuscript.

Effects of AP5 and DNQX on PBG-evoked excitation in DVPNs

In an initial group of five DVPNs, the effects of ionophoretic applications of the NMDA and non-NMDA receptor antagonists AP5 and DNQX, respectively, on the excitations evoked by NMDA and AMPA, respectively, were studied to obtain the threshold ejection currents and the selective ejection current ranges for these antagonists. At currents as low as 0-10 nA, and even at 20 nA, AP5 and DNQX selectively attenuated NMDA- or AMPA-evoked burst firing (Figs 2A, 2C and 4A). Over this low current range, neither AP5 nor DNQX affected the baseline firing rate of the DVPNs (Fig. 4A) though at higher ejection currents, both AP5 (50-100 nA) and DNQX (50-100 nA) reduced the ongoing firing rate in the two DVPNs tested (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Effects of AP5 and DNQX on baseline firing rate and AMPA-evoked responses.

Continuous ratemeter records of the activity of two different vagal preganglionic neurones during application of selective excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists with the stated ionophoretic currents for the times indicated by the bars. Excitatory responses evoked by application of AMPA are attenuated by application of the selective non-NMDA receptor antagonist DNQX but not by the selective NMDA receptor antagonist AP5. At low ejection currents neither antagonist had any effect on baseline firing rate (A). At much higher ejection currents both AP5 and DNQX depressed baseline firing rate (B).

In another group of eight DVPNs, application of AP5 (2-10 nA) effectively reduced (n = 6) or blocked (n = 2) the excitation evoked by PBG (Fig. 5A). As a group, the PBG-evoked excitation was reduced from 2.57 ± 0.58 to 1.62 ± 0.60 Hz (P < 0.001, n = 8) whilst the baseline firing rate was unaltered (1.50 ± 0.44 vs. 1.67 ± 0.49 Hz, n = 8) (Table 1A). This group of eight neurones included three DVPNs in which the PBG-evoked excitation was attenuated by application of Mg2+ (data included in previous section). Similarly, ionophoretic application of DNQX (5-20 nA) attenuated the PBG-evoked excitation in all three neurones studied (from 5.05 ± 0.45 to 2.78 ± 0.72 Hz, P < 0.05, n = 3) (Fig. 5B; Table 1A) without changing baseline firing rate (2.37 ± 0.90 vs. 2.50 ± 1.17 Hz, n = 3). One of these three neurones was tested with Mg2+, DNQX and AP5. All three agents attenuated the PBG response.

Intracellular recordings

In nine neurones, intracellular recordings of membrane potential were combined with ionophoretic application of ligands. The mean resting membrane potential for these nine DVPNs was -58.0 ± 1.9 mV and six of them had on-going discharge at the resting membrane potential. In six DVPNs, ionophoresis of PBG depolarized the membrane potential by 7.0 ± 3.5 mV (range, 0.9-24.0 mV) and increased the firing rate. In all four neurones tested, Mg2+ (10-120 nA), at currents which did not affect NMDA- or DLH-induced depolarization or firing (Fig. 6B), markedly reduced the PBG-induced firing (Fig. 7) and in three of these the PBG-evoked depolarization was also attenuated.

Figure 6. Intracellular records of DVPN activity during application of PBG, DLH and Mg2+.

Records of changes in membrane potential of two DVPNs during application of the selective 5-HT3 receptor agonist PBG, Mg2+ and DLH with the stated ionophoretic currents for the times indicated by the bars. A, ionophoretic application of DLH markedly depolarized the neurone and increased the firing rate whilst in this particular cell PBG evoked an increase in synaptic noise without changing the membrane potential. B, three traces of membrane potential recorded from a DVPN: a, ionophoretic application of DLH depolarized the neurone and increased its firing rate; b,5 min following the start of Mg2+ application - membrane potential and the response to DLH are unaffected by Mg2+; c, membrane potential response to DLH following Mg2+ application. Note: vagal stimulation was applied at 0.5 Hz throughout these recordings and the evoked antidromic spike has been truncated in A.

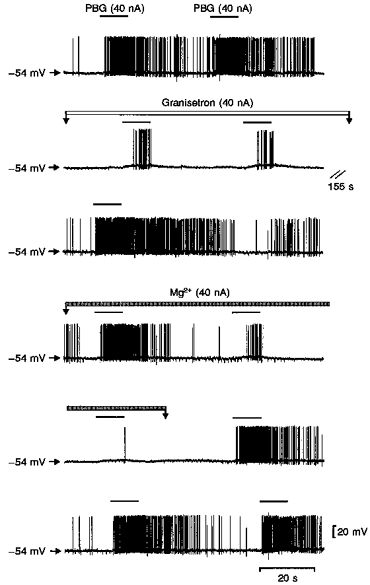

Figure 7. Intracellular records of DVPN activity during application of PBG, granisetron and Mg2+.

Records of changes in membrane potential of a DVPN during application of Mg2+ and the selective 5-HT3 receptor agonist and antagonist PBG and granisetron, respectively, with the stated ionophoretic currents for the times indicated by the bars. Continuous traces (except for the 155 s break) of membrane potential recorded from a DVPN. Ionophoretic application of PBG markedly increased the firing rate of this neurone associated with a small membrane depolarization (trace 1). This PBG-evoked firing was reversibly attenuated by granisetron (traces 2 and 3). Application of Mg2+ reversibly attenuated the PBG-evoked excitation (traces 4, 5 and 6).

In the other three DVPNs, application of PBG (10-200 nA) to the vicinity of the neurones had no effect on the membrane potential but increased the synaptic noise whereas ionophoretic application of DLH to the same neurones depolarized the membrane potential and induced neuronal firing (Fig. 6A). In both of the two DVPNs tested, subsequent application of Mg2+ (40-100 nA) reduced the increase in synaptic noise induced by PBG. At the currents which attenuated PBG-evoked responses, Mg2+ had no effect on the resting membrane potential in five neurones but hyperpolarized one neurone (Figs 6B and 7).

In one of the DVPNs in which the PBG-evoked response was attenuated by Mg2+, the excitation was also attenuated by application of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, granisetron (40 nA, Fig. 7), confirming that the PBG-evoked response was via activation of 5-HT3 receptors as reported previously (Wang et al. 1996).

DISCUSSION

The present data demonstrate that part of the excitation of DVPNs produced by activation of 5-HT3 receptors in vivo is indirect, by inducing release of glutamate from presynaptic terminals. This is based on the following observations in anaesthetized rats: (1) the excitation of DVPNs evoked by the selective 5-HT3 receptor agonist PBG was attenuated by ionophoretic application of Mg2+ and Cd2+ in the vicinity of the recorded neurones; (2) neither Mg2+ nor Cd2+, at currents which attenuated PBG-evoked excitation, altered baseline firing rate; (3) Mg2+, at currents which inhibited PBG-evoked excitation, had no effect on excitations evoked by ionophoretic application of the NMDA receptor agonists NMDA and DLH nor the non-NMDA receptor agonist AMPA; (4) both AP5, a selective NMDA receptor antagonist (Lodge et al. 1988), and DNQX, a selective non-NMDA receptor antagonist (Honoréet al. 1988), could attenuate the PBG-evoked excitations; and (5) direct evidence from intracellular recordings shows that ionophoretic application of PBG to DVPNs evoked increases of synaptic noise, with or without a membrane potential depolarization. These data would accord with anatomical studies which have demonstrated that the majority of 5-HT3 receptors in the dorsal vagal complex are located presynaptically on the terminals of vagal afferent fibres (Pratt & Bowery, 1989; Kidd et al. 1993; Leslie et al. 1994).

These conclusions are based partly on the observations that raising extracellular [Mg2+] or [Cd2+] by ionophoresis and application of glutamate receptor antagonists both attenuated the responses to PBG. A raised extracellular [Mg2+] has been used widely during in vitro studies to inhibit release of neurotransmitters. This is believed to be due to a block of presynaptic voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels (Richards & Sercombe, 1970). In a few other in vivo studies, ionophoretic application of Mg2+ has been similarly used to inhibit neurotransmitter release. It attenuated an excitatory effect of opiates on hippocampal pyramidal neurones (Zieglgansberger, French, Siggins & Bloom, 1979) and an inhibitory input to medial prefrontal cortical neurones (Ashby, Minabe, Edwards & Wang, 1991). However, raised extracellular levels of Mg2+ may also interfere with the postsynaptic 5-HT3 receptor channel (Peters, Hales & Lambert, 1988). Whilst this cannot be entirely ruled out, it is unlikely to account for the current observations since (1) the membrane depolarization evoked by PBG was relatively unaffected by the increase in [Mg2+] at a time when the increase in firing rate and synaptic events were attenuated, and (2) in some neurones, ionophoretic application of PBG increased the rate of firing without a membrane potential depolarization. Even if this mechanism did account for part of the blockade produced by Mg2+, it would not explain why glutamate receptor antagonists also attenuated the response to PBG.

It is well known that Mg2+ is a voltage-dependent blocker of NMDA receptors in the central nervous system (Mayer et al. 1984) and increases in extracellular [Mg2+] could also decrease membrane excitability by a surface charge effect (Frankenhaeuser & Hodgkin, 1957). Since, in vivo, many neurones will be receiving glutamatergic inputs, this could present a problem in interpreting the results of raising extracellular [Mg2+]. However, in the present study, application of Mg2+ with small ionophoretic currents (which were effective in attenuating the response to PBG), did not alter either the baseline firing rate of DVPNs, nor the excitatory effects evoked by the NMDA receptor agonists NMDA or DLH. One explanation for this selectivity may be that at low ejection currents of Mg2+ only a small area around the tip of the electrode is affected, which may not be sufficient for Mg2+ concentrations to build up to affect the majority of the NMDA receptors whose location relative to the electrode tip is unknown. This possibility receives some support from the observation that neither AP5 nor DNQX altered the basal firing rate when applied to DVPNs with low ionophoretic currents, although higher ejection currents of both antagonists did inhibit spontaneous firing of DVMN neurones. In addition, in a few neurones, an attempt was made to increase the Mg2+ ejection current above that needed to attenuate the PBG response. At these higher currents both the baseline firing rate and NMDA-evoked excitation were attenuated. Finally, Cd2+, which does not appear to interact with the NMDA receptor (Mayer et al. 1984), attenuated the PBG-evoked excitation in a manner similar to that of Mg2+.

In the current study, the PBG-evoked excitation of the DVPNs was believed to be due to activation of 5-HT3 receptors since (1) PBG is a relatively selective 5-HT3 receptor ligand (see Hoyer et al. 1994), (2) in one of the intracellular recording experiments ionophoretic application of granisetron, a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (Sanger & Nelson, 1989), attenuated the PBG-evoked firing increase; (3) in a previous study using the same experimental protocol, we demonstrated that ionophoretic application of PBG activated over 80 % of DVPNs tested and this could be selectively attenuated by ionophoretic or i.v. application of the selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists granisetron or tropisetron (Wang et al. 1996).

Whilst this is the first in vivo study to demonstrate a presynaptic action of 5-HT3 receptors in the dorsal vagal complex, there is previous in vitro electrophysiological evidence for such an action. Bath application of 5-HT or 5-HT3 receptor agonists increased both the amplitude and frequency of spontaneous postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) in NTS cells (Glaum, Brooks, Spyer & Miller, 1992). These effects were resistant to TTX yet blocked by the presence of 1 mM Co2+. In addition, application of the non-selective 5-HT3 receptor agonist 2-methyl-5-HT increased spontaneous PSPs in DVMN neurones in vitro (Brooks & Albert, 1995; Albert et al. 1996).

There are numerous functional studies suggesting that glutamatergic transmission within the NTS and DVMN is important in transmission of cardiorespiratory reflex information (see Lawrence & Jarrott, 1996). The effects of arterial baroreceptor (Leone & Gordon, 1989), chemoreceptor (Zhang & Mifflin, 1993) and pulmonary C-fibre afferent stimulation (Wilson, Zhang & Bonham, 1996) are all attenuated by application of glutamate receptor antagonists into the NTS-DVMN complex. This is hardly surprising since glutamate immunoreactive terminals have been identified in both the NTS and DVMN (Saha, Batten & McWilliam, 1995a). Indeed, Saha et al. (1995a) demonstrated that at least 40 % of terminals in the NTS were likely to contain glutamate. Whilst many of these probably arise from intrinsic, glutamate-containing neurones, some terminals have been identified as vagal primary afferent fibres (Saha, Batten & McWilliam, 1995b). In this respect, the location of the putative presynaptic 5-HT3 receptors identified in the present study is unknown. Whilst they may be located on terminals of synaptic inputs to the DVPNs, some of which may be vagal afferent terminals (Pratt & Bowery, 1989; Kidd et al. 1993; Leslie et al. 1994), we cannot rule out the possibility that they are somatic receptors located on intrinsic glutamate-containing neurones antecedent to the DVPNs.

In agreement with our previous studies, the majority of DVPNs tested in this study were activated by PBG (Wang et al. 1996). This implies that preganglionic neurones with differing functions have been included in this analysis. This will include those neurones involved in cardiorespiratory reflexes described above, but will also include those innervating the airways and the gastrointestinal tract. In respect of this latter group, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have been shown to have powerful anti-emetic activity (Smith, Alphin, Jackson & Sancilio, 1989) and the dorsal vagal complex is suggested to be a major site for such activity (see Reynolds, 1995).

The present observations provide evidence that activation of 5-HT3 receptors in the vicinity of DVPNs facilitates glutamatergic inputs to the neurones. Previously, activation of 5-HT3 receptors has been demonstrated to modulate neurotransmitter release in other parts of the central nervous system, presumably by an action on presynaptic terminals. Administration of 5-HT3 receptor agonists enhanced evoked release of glutamate in the NTS (Ashworth-Preece, Jarrott & Lawrence, 1995) and release of dopamine in the striatum (Blandina, Goldfarb, Craddock-Royal & Green, 1989). In contrast, these agonists inhibited release of acetylcholine from cerebral cortex (Barnes, Barnes, Costall, Naylor & Tyers, 1989) and noradrenaline from rat hypothalamic slices (Blandina, Goldfarb, Walcott & Green, 1991).

In conclusion, we have previously reported that an important part of the excitatory action of 5-HT on DVPNs is mediated by activation of 5-HT3 receptors whose location was unknown (Wang et al. 1996). The present data demonstrate that this action is probably by an action on presynaptically located 5-HT3 receptors which facilitate glutamatergic inputs to the neurones.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation and The Wellcome Trust.

References

- Albert AP, Spyer KM, Brooks PA. The effect of 5-HT and selective 5-HT receptor agonists and antagonists on rat dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in vitro. Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;119:519–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby CR, Jr, Minabe Y, Edwards E, Wang RY. 5-HT3-like receptors in the rat medial prefrontal cortex: an electrophysiological study. Brain Research. 1991;550:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91316-s. 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91316-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth-Preece MA, Jarrott B, Lawrence AJ. 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor modulation of excitatory amino acid release in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;191:75–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11564-5. 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JM, Barnes NM, Costall B, Naylor RJ, Tyers MB. 5-HT3 receptors mediate inhibition of acetylcholine release in cortical tissue. Nature. 1989;338:762–763. doi: 10.1038/338762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandina P, Goldfarb J, Craddock-Royal B, Green JP. Release of endogenous dopamine by stimulation of 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptors in rat striatum. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1989;251:803–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandina P, Goldfarb J, Walcott J, Green JP. Serotonergic modulation of the release of endogenous norepinephrine from rat hypothalamic slices. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1991;256:341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PA, Albert A. 5-HT3 receptors in the dorsal vagal complex. In: Reynolds DJM, Andrews PLR, Davis CJ, editors. Serotonin and the Scientific Basis of Anti-emetic Therapy. Oxford: Oxford Clinical Communications; 1995. pp. 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhaeuser B, Hodgkin AL. The action of calcium on the electrical properties of squid axons. The Journal of Physiology. 1957;137:218–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum SR, Brooks PA, Spyer KM, Miller RJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-3 receptors modulate synaptic activity in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius in vitro. Research. 1992;589:62–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honoré T, Davies SN, Drejer J, Fletcher EJ, Jacobsen P, Lodge D, Nielsen FE. Quinoxalinediones: Potent competitive non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonists. Science. 1988;241:701–703. doi: 10.1126/science.2899909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D, Clarke DE, Fozard JR, Hartig PR, Martin GR, Mylecharane EJ, Saxena PR, Humphrey PPA. H0II International Union of Pharmacology Classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) Pharmacological Reviews. 1994;46:157–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo PN, Deuchars J, Spyer KM. Localization of cardiac vagal preganglionic motoneurones in the rat: Immunocytochemical evidence of synaptic inputs containing 5-hydroxytryptamine. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;327:572–583. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JFX, Wang Y, Jordan D. Activity of C fibre cardiac vagal efferents in anaesthetized cats and rats. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:869–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.869bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd EJ, Laporte AM, Langlois X, Fattaccini C-M, Doyen C, Lombard MC, Gozlan H, Hamon M. 5-HT3 receptors in the rat central nervous system are mainly located on nerve fibres and terminals. Brain Research. 1993;612:289–298. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91674-h. 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91674-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalley PM, Bishoff AM, Richter DW. 5-HT1A receptor-mediated modulation of medullary expiratory neurones in the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;476:117–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ, Jarrott B. Neurochemical modulation of cardiovascular control in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Progress in Neurobiology. 1996;48:21–53. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00034-8. 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone C, Gordon FJ. Is L-glutamate a neurotransmitter of baroreceptor information in the nucleus tractus solitarius? Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1989;250:953–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie RA, Reynolds DJM, Newberry NR. Localization of 5-HT3 receptors. In: King FD, Jones BJ, Sanger GJ, editors. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-3 Receptor Antagonists. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: CRC Press Inc; 1994. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge D, Davies SN, Jones MG, Millar J, Manallack DT, Ornstein PL, Verberne AJM, Young N, Beart PM. A comparison between the in vivo and in vitro activity of five potent and competitive NMDA antagonists. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;95:957–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL, Guthrie PB. Voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ of NMDA responses in spinal cord neurones. Nature. 1984;309:261–263. doi: 10.1038/309261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosjean A, Compoint C, Buisseret-Delmas C, Orer HS, Merahi N, Puizillout J-J, Laguzzi R. Serotonergic projections from the nodose ganglia to the nucleus tractus solitarius: an immunohistochemical and double labelling study in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;114:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90422-6. 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazos A, Cortes R, Palacios JM. Quantitative autoradiographic mapping of serotonin receptors in the rat brain. II. Serotonin-2 receptors. Brain Research. 1985;346:231–249. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90857-1. 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90857-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazos A, Palacios JM. Quantitative autoradiographic mapping of serotonin receptors in the rat brain. I. Serotonin-1 receptors. Brain Research. 1985;346:205–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90856-x. 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90856-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JA, Hales TG, Lambert JJ. Divalent cations modulate 5-HT3 receptor-induced currents in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;151:491–495. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90550-x. 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90550-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt GD, Bowery NG. The 5-HT3 receptor ligand [3H]BRL 43694, binds to presynaptic sites in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:1367–1376. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90012-9. 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DJM. Where do 5-HT3 receptor antagonists act as anti-emetics? In: Reynolds DJM, Andrews PLR, Davis CJ, editors. Serotonin and the Scientific Basis of Anti-emetic Therapy. Oxford: Oxford Clinical Communications; 1995. pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Richards CD, Sercombe R. Calcium, magnesium and the electrical activity of guinea-pig olfactory cortex in vitro. Of Physiology. 1970;211:571–584. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Batten TFC, McWilliam PN. Glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid and tachykinin-immunoreactive synapses in the cat nucleus tractus solitarii. Journal of Neurocytology. 1995a;24:55–74. doi: 10.1007/BF01370160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Batten TFC, McWilliam PN. Glutamate-immunoreactivity in identified vagal afferent terminals of the cat: A study combining horseradish peroxidase tracing and electron microscopic immunogold staining. Experimental Physiology. 1995b;80:193–202. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger GJ, Nelson DR. Selective and functional 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor antagonism by BRL 43694 (granisetron) European Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;159:113–124. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90695-x. 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90695-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffar N, Kessler JP, Bosler O, Jean A. Central serotonergic projections to the nucleus tractus solitarii: Evidence from a double labelling study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1988;26:951–958. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90111-x. 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WL, Alphin RS, Jackson CB, Sancilio LF. The antiemetic profile of zacopride. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1989;41:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1989.tb06402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbusch HWM. Distribution of serotonin-immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the rat – cell bodies and terminals. Neuroscience. 1981;6:557–618. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90146-9. 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes RM, Spyer KM, Izzo PN. Central distribution of substance P, calcitonin gene related peptide and 5-hydroxytryptamine in vagal sensory afferents in the rat dorsal medulla. Neuroscience. 1994;59:195–210. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90110-4. 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jones JFX, Ramage AG, Jordan D. Effects of 5-HT and 5-HT1A receptor agonists and antagonists on dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in anaesthetized rats: an ionophoretic study. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;116:2291–2297. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ramage AG, Jordan D. Mediation by 5-HT3 receptors of an excitatory effect of 5-HT on dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in anaesthetized rats: an ionophoretic study. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;118:1697–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ramage AG, Jordan D. Presynaptic 5-HT3 receptors mediate an excitatory action of 5-HT on dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones: an in vivo ionophoretic study in rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;120:38P. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CG, Zhang Z, Bonham AC. Non-NMDA receptors transmit cardio-pulmonary C fibre input in nucleus tractus solitarii in rats. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:773–785. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Miflin SW. Excitatory amino acid receptors within the NTS mediate arterial chemoreceptor reflexes in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;256:H770–773. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.2.H770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieglgansberger W, French ED, Siggins GR, Bloom FE. Opioid peptides may excite hippocampal pyramidal neurons by inhibiting adjacent inhibitory interneurons. Science. 1979;205:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.451610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]