Abstract

Using a chimeric protein comprising the green fluorescent protein (GFP) linked to the C-terminus of the K+ channel protein mouse Kir6.2 (Kir6.2-C–GFP), the interactions between the sulphonylurea receptor SUR1 and Kir6.2 were investigated in transfected human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293) by combined imaging and patch clamp techniques.

HEK 293 cells transfected with mouse Kir6.2-C–GFP and wild-type Kir6.2 exhibited functional K+ channels independently of SUR1. These channels were inhibited by ATP (IC50 = 150 μM), but were not responsive to stimulation by ADP or inhibition by sulphonylureas. Typically, 15 ± 7 active channels were found in an excised patch.

The distribution of Kir6.2-C–GFP protein was investigated by imaging of GFP fluorescence. There was a lamellar pattern of fluorescence labelling inside the cytoplasm (presumably associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus) and intense punctate labelling near the cell membrane, but little fluorescence was associated with the plasma membrane.

In contrast, cells co-transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP and SUR1 exhibited intense uniform plasma membrane labelling, and the lamellar and punctate labelling seen without SUR1 was no longer prominent.

In cells co-transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP and SUR1, strong membrane labelling was associated with very high channel activity, with 484 ± 311 active channels per excised patch. These K+ channels were sensitive to inhibition by ATP (IC50 = 17 μM), stimulated by ADP and inhibited by sulphonylureas.

We conclude that co-expression of SUR1 and Kir6.2 generates channels with the properties of native KATP channels. In addition, SUR1 promotes uniform insertion of Kir6.2-C–GFP into the plasma membrane and a 35-fold increase in channel activity, suggesting that SUR1 facilitates protein trafficking of Kir6.2 into the plasma membrane.

ATP-dependent K+ (KATP) channels play important physiological roles. In pancreatic β-cells they control the cellular response to insulin secretagogues; in heart they regulate action potential duration and excitability under various physiological and pathological conditions (Fosset, De Weille, Green, Schmid-Antomarchi & Lazdunski, 1988; Ventakesh, Lamp & Weiss, 1991; Wang & Lipsius, 1995); in kidney they promote K+ efflux in response to Na+ reabsorption (Hurst, Beck, Laprade & Lapointe, 1993); in the central nervous system they may regulate transmitter release (Mourre, Ben Ari, Bernardi, Fosset & Lazdunski, 1989); in vascular and non-vascular smooth muscles they mediate hypoxic vasodilatation (Daut, Maier-Rudolph, Beckerath, Mehrke & Gunther, 1990) and muscle tone in response to hormones and neurotransmitters (Zhang, Bonev, Mawe & Nelson, 1994).

Inhibition by adenine nucleotides and sulphonylureas are two fundamental properties of KATP channels. Inhibition by adenine nucleotides (ATP or ADP) occurs in the absence of Mg2+ and, therefore, probably involves a regulatory binding site rather than protein phosphorylation. In contrast, in the presence of Mg2+, ADP stimulates channel activity by counteracting the inhibition by ATP. Based on these observations it has been argued that the nucleotide inhibitory and stimulatory regulatory sites are distinct (Findlay, 1987; Lederer & Nichols, 1989; Terzic, Findlay, Hosoya & Kurachi, 1994).

Molecular cloning has led to the identification of two KATP channel genes denoted Kir6.1 (or μKATP) and Kir6.2 (or mBIR), which are part of the inward rectifier K+ channel family (Inagaki et al. 1995a, b). The genes for the sulphonylurea receptors SUR1 and SUR2, members of the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) protein family, have also been cloned recently (Aguilar-Bryan et al. 1995). It has been proposed that SUR1 interacts with Kir6.2 to form functional KATP channels, since expression of Kir6.2, in the absence of SUR1, did not generate K+ currents (Inagaki et al. 1995a). However, it has been recently shown that deletion of the last twenty-six to thirty-six amino acids of the Kir6.2 C-terminus yielded functional Kir6.2 channels, which were inhibited by ATP, but not stimulated by ADP. Stimulation by ADP occurred when these Kir6.2 channel mutants were co-expressed with SUR1 (Tucker, Gribble, Zhao, Trapp & Ashcroft, 1997).

The goal of this study was to investigate whether wild-type Kir6.2 alone forms functional channels sensitive to adenine nucleotides, and to elucidate further the role of SUR1 in KATP channel formation. To address these issues we generated fusion proteins consisting of Kir6.2 and the enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP), which allowed study of the cellular trafficking of Kir6.2 in the presence and absence of SUR1. Using this approach we show, for the first time, that wild-type Kir6.2 alone forms functional ATP-dependent K+ channels in HEK 293 cells. We also find, like Tucker et al. (1997), that SUR1 confers ADP-dependent stimulation as well as sulphonylurea-dependent inhibition on wild-type Kir6.2 channel, and increases the channel's sensitivity to ATP. In addition, our results demonstrate that SUR1 promotes the incorporation of Kir6.2 into the plasma membrane, as is shown by both the distribution of fluorescence and by the increased number of channels in excised patches.

METHODS

Molecular biology and gene expression in HEK 293 cells

The cDNA for mouse Kir6.2 was provided by Dr Seino (Chiba University School of Medicine, Chiba, Japan), for hamster SUR1, by Dr Bryan (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA) and for the β-subunit of the Na+-K+-ATPase by Dr Lingrel (University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, USA). The cDNA for modified green fluorescent protein (pEGFP) was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, USA). For HEK 293 cell transfection, all wild-type cDNAs were subcloned into the vector pCDNA3amp (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNAs used to make the GFP chimeras were subcloned into the pEGFP vector. Both vectors used the CMV promoter.

Oligonucleotides corresponding to the last five amino acids of Kir6.2 (or the β-subunit of the Na+-K+-ATPase) with additional bases encoding a Bam restriction site were synthesized. Additional oligonucleotide primers were synthesized which enabled complete amplification of the coding regions of Kir6.2 and β-subunit. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out using wild-type sequences as templates. The final PCR product was subcloned into pEGFP vectors so that Kir6.2 or β-subunit was in-frame with GFP and had a five amino acid linker region between the end of Kir6.2 or β-subunits and the coding region of GFP.

HEK 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with high glucose supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 u ml−1), streptomycin (100 u ml−1) and 2 mM glutamine and divided once a week by treatment with trypsin (Ribalet, Ciani & Eddlestone, 1989). For HEK 293 cell transfection the cDNA concentration was as follows (μg per 35 mm dish containing 1.5 ml of medium): 0.6 Kir6.2-C–GFP, 0.61SUR1, 0.75β-C-GFP and 0.2Kir6.2. The transfections were carried out using the calcium phosphate precipitation method as described by Graham & van der Eb (1973). Expression of proteins linked to GFP was detected as early as 12 h after transfection. However, fluorescence images were typically acquired after 36 h. Patch clamp experiments were also started approximately 36 h after transfection and were carried out until the cells became confluent (3–4 days after transfection).

Optical imaging of GFP-transfected cells

The distribution of the Kir6.2-C–GFP chimeric protein was investigated by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope (Olympus America Inc, New York). The fluorescence filter set consisted of a 485 nm excitation filter (Filter 485DF22, Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT, USA), a 505 nm long pass dichroic mirror (Filter 505DRLPO2) and a 530 nm long pass emission filter (Filter OG530). Images were obtained using an Olympus plan apo ×60, 1.4 N.A. oil immersion objective and digitized at 12-bits using a cooled CCD camera (Model PXL-KAF1400, Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) and custom software.

Solutions for patch clamp recordings

Single channel currents were recorded in HEK 293 cells using the cell-attached or inside-out patch clamp configuration, with the pipette solution containing (mM): 140 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1.1 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. For the cell-attached patch experiments the bath solution contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 Hepes and 1.2 MgSO4, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. The bath solution for inside-out patch clamp experiments consisted of (mM): 140 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1.1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 5 EGTA and 0.5 CaCl2, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. Prior to patch excision 15 μM ATP was added to the bath solution to minimize channel run-down. ATP was added directly to the bath as MgATP.

Patch clamp data analysis

The data, filtered at 2 kHz with an 8-pole Bessel filter, were recorded with a List EPC 7 patch clamp amplifier, digitized with a digital audio processor, and recorded on videotape at a fixed frequency of 44 kHz. For analysis, the data were sampled at a rate of 5.5 kHz, using a two-buffer interface allowing continuous acquisition. When discrete current steps could be resolved, channel activity was expressed as NPo. To estimate NPo a single channel half-amplitude threshold was first deduced from a single channel amplitude histogram. The threshold value was then used to generate an idealized record of the original data from which channel percentage open time, Po, was deduced. For multiple current steps channel activity was measured at each level and summed to obtain total channel activity or NPo. To express channel activity as a function of ATP concentration, NPo was estimated at each ATP concentration from data samples of 15 s duration. Since channel activity varied widely from patch to patch, NPo values were normalized to NPo values measured in the absence of ATP and plotted as a function of ATP concentration.

When single channels could not be resolved, steady state current values were used instead of NPo to assess the dose-dependent effect of ATP on channel activity (Fig. 7) and estimate N. To estimate the number of channels simultaneously active in a patch (Table 1), K+ currents measured at negative holding potentials, in the absence of ATP, were scaled to a membrane potential of −100 mV (which is valid since the single channel slope conductance is constant at negative potentials). The resulting current values were then divided by the single channel current amplitude at −100 mV (7 pA) to obtain N. This approach provides an underestimate of the total number of active channels in the patch, since Po is likely to be below 1 even in the absence of ATP. The effect of ATP on Kir6.2 and Kir6.2 + SUR1 K+ channel activity was studied after the initial phase of fast channel run-down.

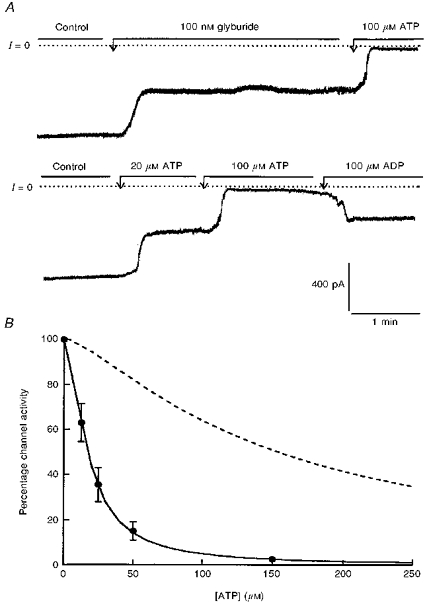

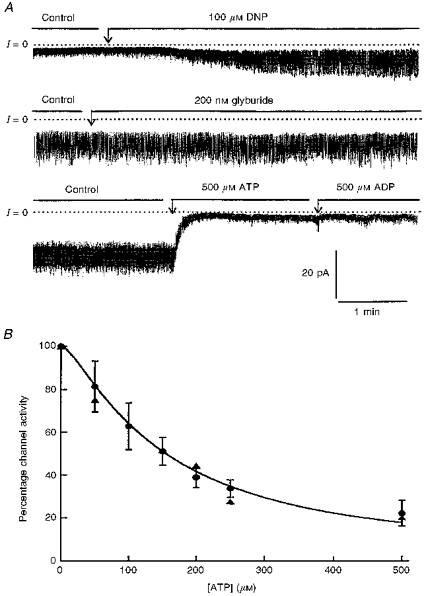

Figure 7. Modulation by adenine nucleotides and sulphonylurea of K+ channels generated by Kir6.2-C–GFP in the presence of SUR1.

A, current recordings obtained in excised inside-out patches (upper and lower traces). Both recordings are from the same patch, but the data in the lower trace were obtained first. The membrane holding potential was −10 mV. The currents are inward currents and channels open downward. The dotted line represents zero current when all channels are closed. The upper trace demonstrates partial channel inhibition by glyburide and almost complete block by 100 μM ATP. The lower trace illustrates the dose-dependent inhibition of Kir6.2 K+ channels by ATP and the reversal of inhibition by ADP. B, ATP-dependent inhibition of Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1 (•). Data points are averages of four measurements obtained from four different patches at various ATP concentrations. Channel activity was normalized to the activity measured in the same patch in the absence of nucleotide. The individual values were then averaged, plotted as a function of ATP, and fitted with the equation given in the legend to Fig. 4. The fit of the data represented by the continuous line yielded K = 17.2 mM and n = 1.56. The dotted line which is shown for comparison represents the sensitivity to ATP of Kir6.2 in the absence of SUR1 (see Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Activity and properties of K+ channels generated by Kir6.2 and Kir6.2 + SUR1

| Channel open time (ms) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| I (pA) | τ1 | τ2 | |

| Kir6.2-C–GFP | 103 ± 51 (n = 14) | 0.72 ± 0.15 (n = 5) | — |

| Kir6.2 +β-C-GFP | 205 ± 87 (n = 4) | 0.98 (n = 2) | — |

| Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1 | 3387 ± 2180 (n = 15) | 0.62 ± 0.32 (n = 3) | 3.56 ± 0.8 (n = 3) |

The data presented in the table were obtained from 11 transfection experiments for Kir6.2-C–GFP, 4 transfections for Kir6.2 +β-C-GFP and 9 transfections for Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1. The first column shows mean current amplitude measured in the excised inside-out patch configuration, following patch excision into ATP-free solution. Currents are normalized to a holding potential of 100 mV. Assuming a single channel conductance of 70 pS, these current amplitudes correspond to simultaneous opening of 15 channels in membrane patches from cells transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP alone, compared with an average of 500 channels in membrane patches from cells transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1. The data shown in columns 2 and 3 are mean time constants deduced from fitting single channel open time histograms obtained with data similar to those presented in Figs 3 and 6. For Kir6.2-C–GFP and Kir6.2 +β-C-GFP the data were well fitted with a single exponential, while fitting the data obtained with Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1 yielded two exponentials. The single channel mean closed time recorded for Kir6.2 +β-C-GFP and Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1 was not significantly different: 11.4 ± 2.2 ms and 11.9 ± 2 ms, respectively. n represents the number of experiments analysed in each case.

Analysis of KATP channel kinetic data was carried out using the approach described in detail by Ribalet et al. (1989), which consists of fitting the open and closed time histograms with a sum of exponentials. The best fit of channel open time histograms yielded two exponentials for Kir6.2 + SUR1, and one exponential for Kir6.2. Since there was more than one channel per patch we did not carry out a detailed analysis of closed times intervals, but provided a value for mean channel closed times.

RESULTS

Co-transfection of HEK 293 cells with GFP and Kir6.2

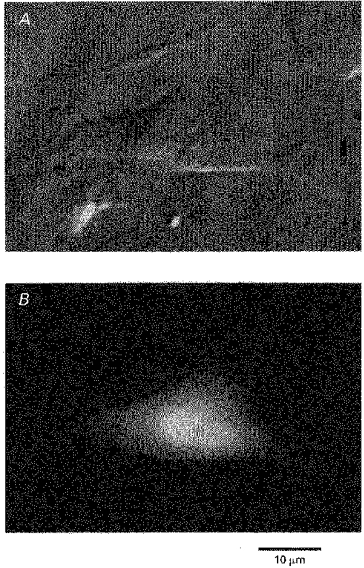

Transfection of HEK 293 cells with plasmids encoding Kir6.2 and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a marker (Chalfie, Tu, Euskirchen, Ward & Prasher, 1994) resulted in a population of cells with fluorescence labelling of the cytoplasm indicative of successful transfection (Fig. 1). The fluorescence was evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm and corresponded to light emitted by the fluorescent GFP, rather than endogenous cellular fluorescence. Figure 1 shows the same field of view under differential interference contrast (DIC) (Fig. 1A) and epi-illumination (Fig. 1B). Many of the cells seen in Fig. 1A are not visible in Fig. 1B and were therefore assumed not to be transfected. Light emitted by GFP was resistant to photobleaching and could be observed as early as 12 h after transfection.

Figure 1. Expression of GFP and Kir6.2 in HEK 293 cells.

Co-transfection with plasmids encoding GFP and the ATP-dependent K+ channel Kir6.2 yielded cells with green fluorescence labelling (B). The fluorescence was evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm. Comparison of the DIC image in A with the fluorescence image in B indicates that only some of the cells were transfected with GFP.

Patch clamp studies were performed using the cell-attached and excised inside-out patches to investigate whether Kir6.2 formed functional channels in the transfected cells. Fluorescent and non-fluorescent cells showed the same low level of channel activity. In most patches one to two inward rectifier K+ channels were found, with a single channel conductance between 20 and 60 pS. None of these channels were blocked by ATP, and in some cases channel activity increased upon addition of the adenine nucleotide. It is unlikely that, at the concentrations used, GFP and Kir6.2 plasmids transfected two totally distinct population of cells, since, in a culture medium containing two plasmids, approximately 50% of transfected cells are likely to receive both plasmids (Cockett, Ochalski, Benwell, Franco & Wardwell-Swanson, 1977; Marshall, Molloy, Moss, Howe & Hughes, 1995). These results suggest, in accordance with Inagaki et al. (1995a), that Kir6.2 alone does not form functional channels. However, we also observed that expression of Kir 2.1 (IRK1), another inward rectifier K+ channel that forms functional homomeric K+ channels when expressed alone or when linked to GFP as a fusion protein (John et al. 1997), no longer formed functional channels when co-expressed with soluble GFP (authors’ unpublished observations). One possibility, therefore, is that under our conditions for cell transfection the GFP plasmid may limit expression of inward rectifier K+ channels or otherwise prevents their formation as functional channels. We do not know the mechanism that underlies this putative inhibitory effect of GFP, and we did not investigate it further since the chimeric proteins allowed us to study successfully the cellular distribution and the properties of Kir6.2 K+ channels (see below).

Cell transfection with GFP linked to the C-terminus of Kir6.2

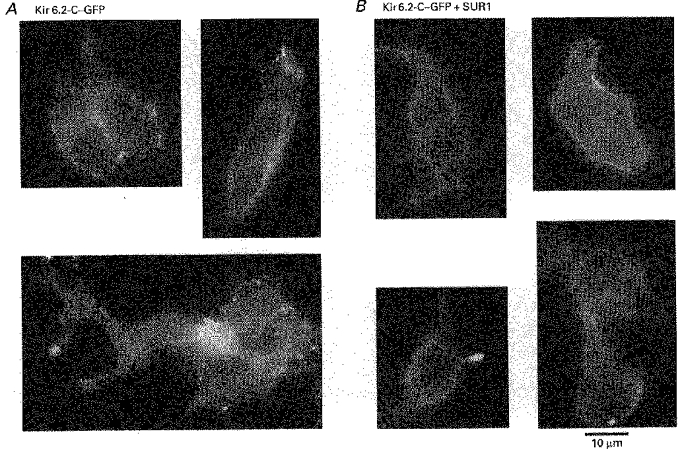

To explain the absence of channel activity in cells co-transfected with Kir6.2 and GFP we hypothesized that interaction of Kir6.2 with a protein such as SUR, which is very likely to be absent in HEK 293 cells, is required to facilitate insertion of the functional channels into the plasma membrane. To test this hypothesis we linked GFP to the C-terminus of Kir6.2 (Kir6.2-C–GFP) and studied the cellular distribution of the construct in the presence and absence of SUR1. Data presented in Fig. 2A are representative of eight different transfection experiments in which cells were transfected with the Kir6.2-C–GFP construct in the absence of SUR1. The transfected cells displayed a rather complex pattern of fluorescence, different from the homogeneous pattern observed when transfection was carried out with GFP and Kir6.2 on separate plasmids (Fig. 1). Specifically the fluorescence obtained with the Kir6.2-C–GFP construct showed a lamellar pattern distributed throughout the cell and around the nucleus (tentatively identified with the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum), an intense punctate pattern at the cell periphery, and light labelling of the plasma membrane. These results indicate that some Kir6.2-C–GFP is targeted to the membrane, or near the membrane, in the absence of SUR1, but most of the tagged proteins remain associated with intracellular membrane structures.

Figure 2. Expression of the chimeric Kir6.2-C–GFP, alone (A) and with SUR1 (B).

A, three images, each obtained from a different transfection experiment representative of the distribution of GFP linked to Kir6.2 in HEK 293 cells. Bright, punctate fluorescent structures, possibly associated with vesicles, were found near the cell membrane. Strong fluorescence in a lamellar pattern was also found and tentatively identified as the endoplasmic reticulum and/or the Golgi apparatus. Dim fluorescence was associated with the plasma membrane. B, four images, which are from four different transfection experiments, representative of cells co-transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP and SUR1, illustrating the effect of SUR1 on Kir6.2-C–GFP localization. Bright, uniform fluorescence is now present over the plasma membrane. In contrast with the images from cells transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP alone, the lamellar and punctate labelling patterns are no longer observed, suggesting that Kir6.2-C–GFP is now uniformly incorporated in the plasma membrane. For further information on cellular distribution of GFP, including 3-D images, see the Web site: http://www.medsch.ucla.edu/som/physio/faculty/br.htm

Effects of co-transfection with Kir6.2 and SUR1

The observation of intracellular lamellar and punctate fluorescence patterns together with faint plasma membrane labelling suggests that trafficking of Kir6.2-C–GFP towards the cell surface is hampered in the absence of SUR. To test the hypothesis that SUR1 facilitates trafficking and incorporation of Kir6.2-C–GFP into the plasma membrane, we co-transfected HEK 293 cells with Kir6.2-C–GFP constructs together with SUR1 on separate plasmids. Representative images of such transfected cells obtained from eight different transfection experiments are shown in Fig. 2B. In this case the fluorescence pattern is dramatically different from that observed with Kir6.2-C–GFP alone. The membrane shows strong, uniform fluorescence labelling. The fluorescence associated with the lamellar structures, as well as the punctation at the cell periphery, is no longer prominent. These observations suggest that a major role of SUR1 is to interact with the pore forming protein, Kir6.2, inside the cell and facilitate its trafficking and incorporation evenly into the plasma membrane (see Discussion for consideration of other explanations). It was noted that, in the presence of SUR1, a small fraction (<15%) of the cells that were fluorescently labelled had a punctate pattern of fluorescence, similar to that observed in cells transfected with the Kir6.2-C–GFP alone. These cells may represent a population that were only transfected with the Kir6.2-C–GFP plasmid.

Do Kir6.2-C–GFP constructs generate functional KATP channels in the absence of SUR1?

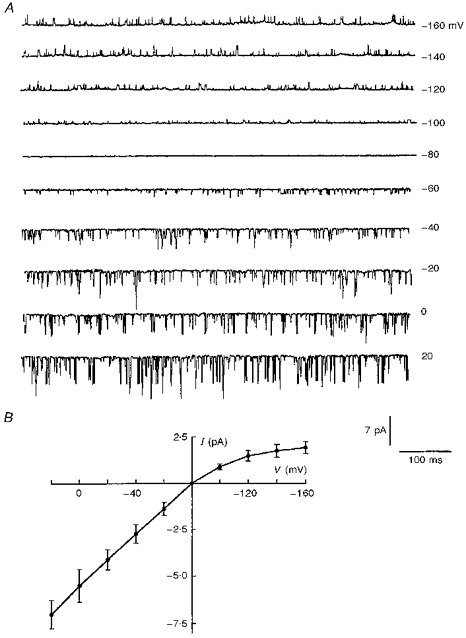

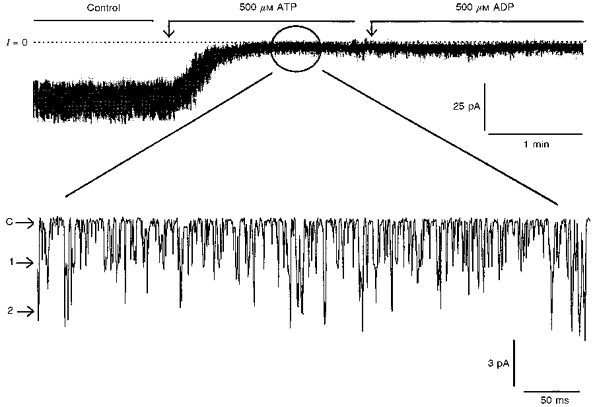

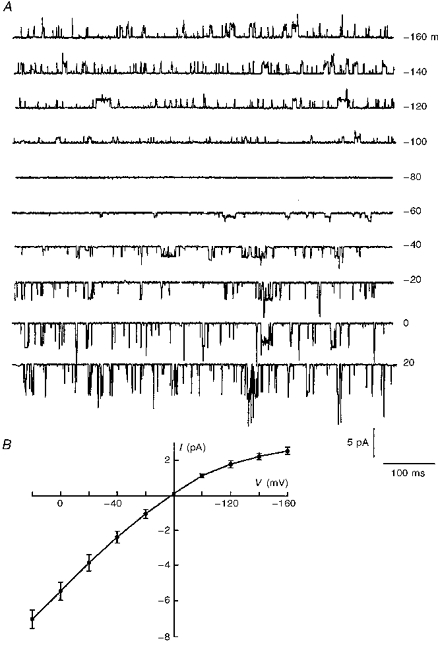

To assess whether the cells transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP constructs displayed functional KATP channels, we performed cell-attached and excised inside-out patch clamp experiments on transfected cells. In both patch configurations, channel activity was observed with very short open times (Fig. 3A). The open time histogram was well fitted with a single exponential having τ = 0.72 ± 0.15 ms (Table 1). Single channels exhibited a conductance of 69.3 ± 4.3 pS for inward currents, and weak inward rectification (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Effects of membrane potential on single channel currents generated by Kir6.2-C–GFP.

A, current recordings measured at varying holding potentials in the cell-attached patch configuration, with 5 mM K+ in the bath. Downward deflections represent inward currents. B, the I-V relationship obtained from recordings similar to those in A. The values on the horizontal axis and on the right side of A are pipette holding potentials.

In the cell-attached patches, channel density varied significantly from patch to patch, but typically two to six channels opened simultaneously. Bath application of the mitochondrial inhibitor dinitrophenol (to decrease cellular ATP) caused a dramatic 8.1 ± 1.4-fold (n = 3) increase in channel activity within 1–2 min (Fig. 4A, top trace), which was only partially reversible upon removal of dinitrophenol. Upon patch excision into ATP-free solutions, channel activity increased further and remained at a steady state level for over 10 min. Maximum currents corresponding to simultaneous opening of around thirty channels were observed; average currents measured in this patch configuration corresponded to 15 ± 7 (n = 14) simultaneously active channels per patch (Table 1). These numbers probably underestimate the total number of channels in the patch because of their very short open time. Nonetheless, this estimated channel density is much greater than that in untransfected HEK 293 cells where, in excised inside-out patches, the number of endogenous channels, which were not ATP-inhibited, never exceeded two per patch.

Figure 4. Modulation of Kir6.2-C–GFP by adenine nucleotides and sulphonylureas.

A, current recordings obtained in the cell-attached mode (upper trace) and with excised inside-out patches (middle and lower traces). The membrane holding potential was −25 mV for the upper trace and −20 mV for the middle and lower traces. In all cases currents are inward and channels are shown to open downward. The dotted line represents zero current when all channels are closed. The upper trace illustrates the effect of the mitochondrial inhibitor dinitrophenol (DNP). Within 2 min, DNP stimulated channel activity, and the effect reached a maximum after about 3 min. The stimulatory effect of DNP was poorly reversible (not shown). The middle trace illustrates the lack of channel inhibition by the sulphonylurea glyburide. The lower trace represents the inhibitory effect of ATP and the lack of channel stimulation by MgADP. B, ATP-dependent inhibition of Kir6.2-C–GFP (•) and Kir6.2 +β-C-GFP (▴). Data points are averages of six measurements (•) and two measurements (▴) obtained from ten patches, with various ATP concentrations. To allow for comparison between patches, the channel activity was normalized to the activity measured in the same patch in the absence of nucleotide. The individual values were then averaged, plotted as a function of ATP, and fitted with the equation: I/Io = 100/(1 + (C/K)n), where C is the ATP concentration, K is the IC50 constant and n is a Hill coefficient. The fit of the data represented by the continuous line yielded K = 151 mM and n = 1.3.

Inside-out patch clamp experiments were carried out to investigate the channel sensitivity to adenine nucleotides and sulphonylureas. Figure 4 illustrates the inhibitory effect of ATP. Half-maximum inhibition occurred at 151 μM, and 500 μM ATP caused a 78 ± 6% reduction in current amplitude (Fig. 4B). The inhibitory effect of ATP was fully reversible upon removal of the nucleotide. Addition of ADP, in the absence of ATP had similar inhibitory effect, with half-maximum inhibition at 370 μM. Maximum ADP-induced inhibition at concentrations greater than 2 mM was 49.4 ± 4.9%. Addition of 500 μM MgADP did not reverse the inhibitory effect of 500 μM ATP (Fig. 4A, lower trace). With 500 μM MgADP + 500 μM ATP the channel activity was 101 ± 7.3% of that recorded with 500 μM ATP alone. These observations are consistent with the result of Tucker et al. (1997) using Kir6.2 constructs with portions of the C-terminus deleted. These results indicate that the pore forming protein Kir6.2 has a site responsible for ATP/ADP-dependent inhibition, but not for MgADP-dependent channel stimulation. We also found, in agreement with Tucker et al. (1997), that the sulphonylurea glyburide, at concentrations up to 250 nM, had no effect on channel activity (Fig. 4A, middle panel). In the presence of 250 nM glyburide channel activity was 104 ± 9.4% of control.

The short open times of Kir6.2 channels and their low ATP sensitivity contrast with the prolonged open times and high ATP sensitivity of native KATP channels (Ashcroft, 1988; Ribalet et al. 1989). The change in channel kinetic properties may result from linkage of GFP to the Kir6.2 C-terminus. For instance, short channel open times could be explained if GFP interfered with the protein C-terminus comprising the ‘gate’ which is responsible for channel fast opening and closing (Tucker et al. 1997). To test this hypothesis, untagged, wild-type Kir6.2 was studied in HEK 293 cells identified using an independent marker made by linking GFP to the β-subunit of the Na+-K+-ATPase (β-C-GFP). Under these conditions, channel activity was recorded with properties similar to those of the fusion protein Kir6.2-C–GFP. Channel openings were short (Fig. 5, lower trace), and their distribution could be fitted by a single exponential with τ = 0.98 ms (Table 1). The sensitivity to ATP was also low; half-maximum inhibition occurred at 143 μM ATP (see comparison in Fig. 4B between data points obtained with Kir6.2-C–GFP (filled circles) and Kir6.2 +β-C-GFP (filled triangles). ADP did not reverse channel inhibition induced by ATP (Fig. 5, upper trace), and glyburide had no inhibitory effects at concentrations up to 250 nM (not shown). Finally, with β-C-GFP the density of Kir6.2 K+ channels was not significantly different form that observed with Kir6.2-C–GFP (see Table 1). Thus, both the wild-type Kir6.2 and the Kir6.2-C–GFP fusion protein form functional ATP-sensitive K+ channels and as we observe no differences in channel properties, we conclude that linking GFP to the Kir6.2 C-terminus does not alter channel behaviour.

Figure 5. Kinetic behaviour of wild-type Kir6.2 and modulation by adenine nucleotides.

The upper trace is a recording obtained in an excised inside-out patch of a cell transfected with wild-type Kir6.2, and β-C-GFP as a marker. These data illustrate the inhibitory effect of ATP and the lack of channel stimulation by MgADP. The lower trace is a representative segment of the upper one, displayed using an expanded time scale to illustrate the short open times of wild-type Kir6.2. The labels to the left of this lower trace indicate when all the channels are closed (C), when one channel is open (1) and when two channels are open (2). In this experiment the membrane holding potential was −55 mV.

These data are the first to demonstrate that wild-type Kir6.2 forms functional ATP-dependent K+ channels. The channel exhibits very short open times, and possesses the site responsible for adenine nucleotide-mediated inhibition, but not that responsible for ADP-mediated stimulation. In addition, the channel activity is not affected by glyburide at concentrations 10 times greater than those shown to bind to the high affinity sulphonylurea receptor, SUR1.

Modulation of Kir6.2 channel properties by SUR1

Experiments were carried out to characterize the properties of K+ channels generated by co-expression of Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1. SUR1 had no effect on the properties of endogenous K+ channels in HEK 293 cells, but it affected the behaviour of heterologous Kir6.2 channels in three major ways: it increased dramatically the channel density in the plasma membrane, changed the channel sensitivity to adenine nucleotides and sulphonylureas, and altered the single channel kinetics.

Study of single channel properties was performed using the cell-attached patch mode, where inhibition of Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1 by intracellular ATP was greater than 99% (see Discussion), and where opening of only one to two channels was observed in some patches. The data presented in Fig. 6A show short as well as prolonged channel openings that were well fitted by two exponentials having values of τ of 0.62 ± 0.32 ms and 3.56 ± 0.8 ms (Table 1), as observed with native KATP channels (Ribalet et al. 1989). In addition, the single channel conductance of 67.6 ± 3.6 pS and weak inward rectification (Fig. 6B) closely resemble those of native KATP channels.

Figure 6. Effects of membrane potential on single channel currents generated by Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1.

A, current recordings obtained at varying holding potentials in the cell-attached patch configuration, in the presence of 5 mM K+ in the bath. Downward deflections represent inward currents. B, the I-V relationship obtained from recordings similar to those shown in A. The values on the horizontal axis and on the right margin of A are pipette holding potentials.

The most dramatic effect of SUR1 was observed upon patch excision into ATP-free solution. In this case, the patch pipette currents resembled whole-cell macroscopic currents due to a remarkably large number of active channels (see Fig. 7). From the current value presented in Table 1 we estimate that on average 484 ± 311 (n = 15) simultaneously active channels were present in an excised inside-out patch, with Kir6.2-C–GFP + SUR1, as compared with an average of 15 ± 7 (n = 14) channels with Kir6.2-C–GFP alone. Under these conditions the maximum number of channels that we ever estimated was close to 1200, as compared with a maximum of thirty in the absence of SUR1. These data together with the morphological data showing the effects of SUR1 on membrane labelling by Kir6.2-C–GFP (Fig. 2) strongly suggest that SUR1 increases channel density in the plasma membrane by facilitating cellular trafficking and membrane insertion of Kir6.2.

Data presented in Fig. 7 are from eight representative excised inside-out patch experiments carried out to determine, after channel run-down, the channel sensitivity to adenine nucleotides and sulphonylureas. Inhibition of channel activity was almost complete at 100 μM ATP. Half-maximum inhibition occurred at 17.2 μM ATP and at 162 μM ADP. In contrast to the experiments performed with cells transfected with Kir6.2-C–GFP alone, addition of 100 μM MgADP reversed the inhibitory effect of 100 μM ATP. On average, ADP restored channel activity by 35.8 ± 11.2% (n = 4). Both the inhibitory effects of ATP and the stimulatory effect of ADP were fully reversible upon removal of the adenine nucleotide. Addition of 100 nM glyburide induced a 45 ± 13.2% (n = 5) channel inhibition. The half-inhibitory concentration was close to 32 nM.

DISCUSSION

We have shown here for the first time that wild-type Kir6.2 forms functional KATP channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor (SUR1). Compared with native KATP channels, wild-type Kir6.2 channels exhibit rapid gating kinetics, low sensitivity to inhibition by ATP and lack of inhibition by sulphonylureas or stimulation by ADP. Co-expression with SUR1 favours the insertion of functional Kir6.2 channels into the membrane, and confers kinetics and adenine nucleotide-dependent properties comparable to those of native KATP channels.

Evidence that SUR1 facilitates membrane insertion of Kir6.2

We have linked GFP to the C-terminus of Kir6.2 (Kir6.2-C–GFP) in order to study the cellular distribution of the channel protein and characterize its properties. Using this approach, we found faint uniform labelling of the plasma membrane as well as a lamellar pattern of labelling distributed throughout the cell and around the nucleus, and intense punctate fluorescence at the cell periphery (Fig. 2). This suggests that, in the absence of SUR1, Kir6.2 is primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus or vesicles beneath the cell surface, and only a small fraction is inserted in the plasma membrane. In this case, patch clamp experiments indicate the presence of, on average, fifteen active exogenous channels per patch (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Co-transfection of Kir6.2-C–GFP with SUR1 led to dramatic changes in the fluorescence distribution and channel activity. The lamellar and punctate distribution of fluorescence observed with Kir6.2 alone was replaced by strong uniform labelling of the plasma membrane (Fig. 2), an observation consistent with efficient insertion of Kir6.2 into the plasma membrane. In support of this conclusion, patch clamp studies indicate that the intense membrane labelling evoked by SUR1 correlated with a 35-fold increase in channel activity (Table 1). Based on these observations we propose that in the absence of SUR1, insertion of Kir6.2 into the plasma membrane is limited, and that SUR1 interacts with Kir6.2 in the endoplasmic reticulum or in the Golgi apparatus to facilitate cellular translocation of the channel and its insertion evenly into the membrane. However, at the present time we cannot resolve with optical methods whether the punctate fluorescence is localized immediately below or in the plasma membrane. Thus, it could also be assumed, based on these data only, that Kir6.2 alone forms clusters of inactive channels in the membrane that upon interaction with SUR1 diffuse throughout the membrane and become functionally active. However, as this mechanism does not account for the effect of SUR1 in diminishing the labelling of cytoplasmic lamellae, we favour the conclusion that the channel is trapped in submembrane vesicles.

Evidence that wild-type Kir6.2 channels form functional KATP channels

Data presented in Figs 4 and 5 indicate that both wild-type Kir6.2 and Kir6.2-C–GFP constructs formed ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Half-maximum inhibition by ATP occurred at around 150 μM (Fig. 4B). The activity of these K+ channels was not stimulated by MgADP in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of ATP, or blocked by glyburide (Figs 4 and 5). We conclude that the wild-type pore forming protein, Kir6.2, possesses the site responsible for ATP-dependent inhibition, but not that accounting for ADP-dependent stimulation or sulphonylurea-induced inhibition. Similarly, Tucker et al. (1997) showed that truncated Kir6.2 formed functional KATP channels without SUR1, which are inhibited by high ATP concentrations and not stimulated by ADP or inhibited by sulphonylureas. We also found, in agreement with Tucker et al. (1997), that co-expression of Kir6.2 with SUR1 conferred inhibition by sulphonylureas and stimulation by ADP and caused increased ATP sensitivity after channels have run down. Thus, wild-type Kir6.2 K+ channels behave in our hands like the Kir6.2 truncated form used by Tucker et al. (1997).

Comparison of wild-type and GFP-linked Kir6.2 channel properties

We found no evidence for any differences in the properties of the K+ channels formed by the wild-type Kir6.2 (in the presence of β-C-GFP as a marker) and the Kir6.2-C–GFP fusion protein. Both channels exhibited ATP sensitivity at around 150 μM, flickery single channel kinetics and insensitivity to MgADP and sulphonylureas (Figs 4 and 5). Although we could not study cellular distribution of wild-type Kir6.2 (as it is not fluorescent), the similar levels of channel activity in excised patches (Table 1) suggest that both are inserted into the plasma membrane at low efficiency, compared with the level of Kir6.2-C–GFP insertion when co-expressed with SUR1.

Our finding that wild-type Kir6.2 forms functional channels in the absence of SUR1 appears to be at variance with other studies that did not observe functional KATP channels in Kir6.2-transfected cells (Inagaki et al. 1995b; Tucker et al. 1997). To explain this discrepancy it could be assumed that functional channels are formed by Kir6.2-C–GFP due to linkage of GFP to the C-terminus of Kir6.2 interfering with an inhibitory mechanism, which, in native channels, is released by SUR1. However, our data showing similar properties of Kir6.2-C–GFP and untagged Kir6.2 (with β-C-GFP as a marker of transfection) effectively rule out this possibility. In addition, it could be postulated that, in the presence of β-C-GFP, Kir6.2 channel activity is due to β-C-GFP acting like SUR1 to release the intrinsic Kir6.2 inhibitory mechanism. Since the adenine nucleotide sensitivity and kinetic properties of K+ channels formed by homomeric, full-length Kir6.2 in the presence of β-C-GFP are very similar to those of Kir6.2-C–GFP (our data) and of truncated Kir6.2 (Tucker et al. 1997; Proks & Ashcroft, 1997), but are very different from those of K+ channels generated by Kir6.2 + SUR1, this mechanism is unlikely. Therefore, if one or both of the Na+-K+-ATPase subunits interact with Kir6.2 to induce channel activity, it would have to do so without affecting Kir6.2 channel properties as SUR1 does. We cannot discount the possibility that endogenous proteins, like the Na+-K+-ATPase subunits, which are present in HEK 293 cells, interact with Kir6.2 to allow for the low level channel insertion into the membrane that was observed when cells were transfected with Kir6.2 alone. However, if such an interaction occurs, it does not yield channels with properties of native ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Finally, endogenous β-subunits of the Na+-K+-ATPase are normally present in great excess relative to ion channels in most cells, so that it is not clear that β-C-GFP co-expression with Kir6.2 would promote significant additional interactions between these two proteins.

Effects of SUR1 on Kir6.2 K+ channel kinetic properties

K+ channels generated by Kir6.2-C–GFP exhibited fast gating kinetics (Figs 3 and 5, and Table 1). We initially considered whether this behaviour resulted from linking GFP to the protein C-terminus. However, wild-type Kir6.2 (without GFP), co-expressed with the β-C-GFP, generated ATP-dependent K+ channels with properties indistinguishable from those of Kir6.2-C–GFP (see Figs 4 and 5). Like Kir6.2-C–GFP, wild-type Kir6.2 generated K+ channels characterized by short openings (Figs 3 and 5, and Table 1). This rules out the possibility that fast channel gating was due to linking GFP to the C-terminus. Co-expression of Kir6.2-C–GFP with SUR1 yielded KATP channels exhibiting short as well as prolonged open times. In this case, as well as for native KATP channels (Ribalet et al. 1989), the open time histogram was well fitted by two exponentials (Table 1). Comparative studies of truncated Kir6.2 and Kir6.2 + SUR1 K+ channels have shown similar effects of SUR1 on channel kinetic properties (Proks & Ashcroft, 1997). Together these results suggest that the pore forming protein, Kir6.2, exhibits fast kinetics which may be shifted to a more prolonged open state in the presence of SUR1.

The effects of SUR1 on channel kinetics and insertion may explain at least in part why others did not observe functional KATP channels in Kir6.2-transfected cells. For instance, with their experimental protocol, including method of transfection, Inagaki et al. (1995b) typically observed approximately five KATP channels in excised inside-out patch from cells transfected with Kir6.2 + SUR1, whereas we observed on average 500 active channels per patch. Assuming that SUR1 increases the channel density by the same factor (i.e. 35-fold) with both transfection methods, it may be predicted that only one channel would occur in every ten patches using the transfection conditions of Inagaki et al. (1995b). Given the flickery nature of wild-type Kir6.2 K+ channels, it is not surprising that functional KATP channels were not observed in the absence of SUR1 under these conditions.

Physiological implications

The modulation of Kir6.2 channel properties by SUR1 accounts for some of our observations made with native KATP channels in pancreatic β-cells and cardiac cells. For instance, trypsin and metabolic inhibition cause reduction in ATP sensitivity, cause loss of sensitivity to MgADP and sulphonylureas, and prevent run-down in excised patches (Ribalet et al. 1989; Nichols & Lopatin, 1993; Furukawa, Fan, Sawanobori & Hiraoka, 1993; Deutsch & Weiss, 1994). We speculate that such interventions promote dissociation of SUR1 from Kir6.2, which results in channels having properties resembling those of homomeric Kir6.2 channels.

In summary, our results indicate that in addition to endowing native KATP channel properties by conferring ADP and sulphonylurea sensitivity on Kir6.2, SUR1 facilitates cellular trafficking and uniform membrane insertion of functional Kir6.2 K+ channels.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the expert assistance of Dr Yujuan Lu in preparing the various DNA constructs. This work was supported by NIH grants DK46616 and a Research Grant from the American Diabetes Association to B. R, HL36729 and HL52319 to J. N. W. and GM54340 to J. R. M., by a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (Greater Los Angeles Affiliate) to S. A. J., and by the Laubisch Fund and Kawata Endowment to J. N. W.

References

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Nichols CG, Wechsler SW, Clement JP, IV, Boyd AE, III, Gonzalez G, Herrera-Sosa H, Nguy K, Bryan J, Nelson DA. Cloning of the β cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: A regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1988;11:97–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.000525. 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockett MI, Ochalski R, Benwell K, Franco R, Wardell-Swanson J. Simultaneous expression of multi-subunit proteins in mammalian cells using a convenient set of mammalian cell expression vectors. Biotechniques. 1977;23:402–405. doi: 10.2144/97233bm11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J, Maier-Rudolph W, Von Beckerath N, Mehrke G, Gunther K. Hypoxic dilation of coronary arteries is mediated by ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Science. 1990;247:1341–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.2107575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch N, Weiss JN. Effects of trypsin on cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channels. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:H613–622. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.2.H613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay I. The effects of magnesium upon adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels in a rat insulin-secreting cell line. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;391:611–629. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosset M, De Weille JR, Green RD, Schmid-Antomarchi H, Lazdunski M. Antidiabetic sulfonylureas control action potential properties in heart cells via high affinity receptors that are linked to ATP-dependent K+ channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:7933–7936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Fan Z, Sawanobori T, Hiraoka M. Modification of the adenosine 5′-triphosphate-sensitive K+ channel by trypsin in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;466:707–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FL, Van der Eb AJ. Transformation of rat cells by DNA of human adenovirus 5. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90163-3. 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst AM, Beck JS, Laprade R, Lapointe JY. Na+ pump inhibition down-regulates an ATP-sensitive K+ channel in rabbit proximal convoluted tubule. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:F760. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.4.F760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: An inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995a;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Tsuura Y, Namba N, Masuda K, Gonoi T, Horie M, Seino Y, Mizuta M, Seino S. Cloning and functional characterization of a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues, including pancreatic islets, pituitary, skeletal muscle, and heart. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995b;270:5691–5694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5691. 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John SA, Goldhaber JI, Weiss JN, Ribalet B. Ion channels fused to green fluorescent protein are expressed normally and retain physiological properties. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:A253. [Google Scholar]

- Lederer WJ, Nichols CG. Nucleotide modulation of the activity of rat heart ATP-sensitive K+ channels in isolated membrane patches. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;419:193–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J, Molloy R, Moss GWJ, Howe JR, Hughes TE. The jellyfish green fluorescent protein: a new tool for studying ion channel expression and function. Neuron. 1995;14:211–215. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90279-1. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourre C, Ben Ari Y, Bernardi H, Fosset M, Lazdunski M. Antidiabetic sulfonylureas: localization of binding sites in the brain and effects on the hyperpolarization induced by anoxia in hippocampal slices. Brain Research. 1989;486:159–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91288-2. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Lopatin AN. Trypsin and alpha-chymotrypsin treatment abolishes glibenclamide sensitivity of KATP channels in rat ventricular myocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 1993;422:617–619. doi: 10.1007/BF00374011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Phentolamine block of KATP channels is mediated by Kir6.2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:11716–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribalet B, Ciani S, Eddlestone GT. ATP mediates both activation and inhibition of K(ATP) channel activity via cAMP-dependent protein kinase in insulin-secreting cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:693–717. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.4.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzic A, Findlay I, Hosoya Y, Kurachi Y. Dualistic behavior of ATP-sensitive K+ channels toward intracellular nucleoside diphosphates. Neuron. 1994;12:1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulfonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–182. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventakesh N, Lamp ST, Weiss JN. Sulfonylureas, ATP-sensitive K+ channel, and cellular K+ loss during hypoxia, ischemia, and metabolic inhibition in mammalian ventricle. Circulation Research. 1991;69:623–637. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Lipsius SL. Acetylcholine activates a glibenclamide-sensitive K current in cat atrial myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:H1321–1334. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Bonev AD, Mawe GM, Nelson MT. Protein kinase A mediates activation of ATP-sensitive K currents in gallbladder smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:G494–499. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.3.G494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]