Abstract

Whole-cell Na+-activated K+ (KNa) channel currents and single KNa channels were studied with the patch-clamp method in small (20-25 μm) dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurones in slices of rat dorsal root ganglia.

The whole-cell KNa channel current was identified as an additional K+-selective leakage current which appeared after cell perfusion with internal solutions containing different [Na+]. The concentration for half-maximal activation of KNa channel current was 39 mm and the Hill coefficient was 3.5. At [Na+]i above 12 mm, KNa channel current dominated the unspecific leakage current. The ratio of maximum KNa channel current to unspecific leakage current was 45.

KNa channel current was not activated by internal Li+. It was suppressed by external 20 mm Cs+ but not by 10 mm tetraethylammonium.

Single KNa channels with a conductance of 142 pS in 155 mm external K+ ()-85 mm internal K+ () solutions were observed at a high density of about 2 channels μm−2.

In two-electrode experiments, a direct correlation was seen between development of whole-cell KNa channel current and activation of single KNa channels during perfusion of the neurone with Na+-containing internal solution.

Under current-clamp conditions, KNa channels did not contribute to the action potential. However, internal perfusion of the neurone with Na+ shifted the resting potential towards the equilibrium potential for K+ (EK). Varying external [K+] indicated that in neurones perfused with Na+-containing internal solution the resting potential followed the EK values predicted by the Nernst equation over a broader voltage range than in neurones perfused with Na+-free solution.

It is concluded that the function of KNa channels has no links to firing behaviour but that the channels could be involved in setting or stabilizing the resting potential in small DRG neurones.

K+ channels activated by internal Na+ (KNa channels) described initially in cardiac myocytes (Kameyama, Kakei, Sato, Shibasaki, Matsuda & Irisawa, 1984) have been found in many types of neuronal membranes (Dryer, 1991; Egan, Dagan, Kupper & Levitan, 1992a, 1992b; Dryer, 1994). They are characterized by a large unitary conductance, frequent appearance of substates and low sensitivity to external tetraethylammonium (TEA). The channels need at least 20 mm internal Na+ to become active. The level of intracellular Na+ in neurones, however, is lower than 20 mm and is unlikely to increase considerably as a result of Na+ influx through voltage-gated Na+ channels (Dryer, 1991). Co-localization of KNa and voltage-activated Na+ channels in the narrow nodal region of myelinated amphibian axon (Koh, Jonas & Vogel, 1994) led to the assumption that KNa channels could be activated due to local Na+ accumulation during long high-frequency trains of action potentials. In the somata of rat motoneurones, KNa channels were found at increased densities in the vicinity of the processes, probably axons, in the region of increased Na+ channel density and most probable Na+ accumulation (Safronov & Vogel, 1996). Their activation during trains of action potentials resulted in a pronounced slow after-hyperpolarization. Therefore, KNa channel distribution and their co-localization with Na+ channels appear to play a crucial role in defining their function in the neuronal membrane.

During our experiments with small (20-25 μm) sensory neurones in thin slices of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) of newborn rat (Safronov, Bischoff & Vogel, 1996), KNa channel activity was observed in membrane patches. In contrast to motoneurones and peripheral axons, small DRG neurones with round somata do not possess an anatomical structure such as the axonal hillock or the node of Ranvier with a high density of Na+ channels and a large ‘surface-to volume’ ratio which could enhance Na+ accumulation. Moreover, small DRG neurones of C-type are not able to generate action potentials at high frequencies (Harper & Lawson, 1985b; authors’ unpublished observations). Therefore, it seems unlikely that activation of KNa channels has a direct link to firing behaviour in these neurones. On the other hand, small DRG neurones in the slice preparation have a very high input resistance of several gigaohms (Safronov et al. 1996) and activation of even a small additional conductance could thus have an influence on membrane resting potential.

Most studies of KNa channels have been performed on cultured or dissociated neurones (Dryer 1991; Egan et al. 1992b; Haimann, Magistretti & Pozzi, 1992) and channel densities and membrane resting conductances could differ from those in intact cells. In addition, previous studies were mainly focused on properties of single KNa channels and only little is known about whole-cell KNa channel currents and maximum KNa channel conductance in the neuronal membrane. The purpose of the present study was to describe the whole-cell KNa channel conductance and single KNa channels as well as to estimate their contribution to action potentials and resting potentials in intact DRG neurones.

METHODS

Preparation

Experiments were carried out using the patch-clamp technique (Hamill, Marty, Neher, Sakmann & Sigworth, 1981) on 150 μm thin slices prepared from dorsal root ganglia of 4- to 9-day-old rats (Safronov et al. 1996). In brief, rats were rapidly decapitated (in accordance with the German guidelines) and two dorsal root ganglia from lower thoracal and lumbar regions were carefully cut out in ice-cold standard external solution. The ganglia were desheathed using fine forceps and embedded in 2% agar according to the procedure described elsewhere (Edwards, Konnerth, Sakmann & Takahashi, 1989; Takahashi, 1990). After solidification of the agar, small blocks containing the ganglia were cut out. The slices were made using a tissue slicer. The slices were further prepared and kept according to the description given by Takahashi (1990). The experiments were performed on small DRG neurones (Harper & Lawson, 1985a, 1985b), with a diameter of 20-25 μm, which could be directly accessed on the surface of the slice (Safronov et al. 1996). Membrane input resistance of the neurones measured using pipettes filled with a high internal K+ () solution was 1.3 ± 0.2 GΩ (19 neurones).

Solutions

The composition of all external and internal solutions used in the present study is given in Table 1. Most external solutions were bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. The slices were prepared and maintained in a standard external solution. During experiments the slices were perfused with Ca2+-free solution. The Ca2+-free external solution used for filling the pipettes in experiments with inside-out patches (Ca2+-freeo solution) was buffered with Hepes-NaOH. Tetrodotoxin (TTX; 100 nm) was included in the high external K+ () solution, in order to block voltage-activated Na+ channels. High-K-TEA solution contained in addition 1 mm TEA for suppression of delayed rectifier and large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. TTX, TEA and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) were directly added to the external solutions. Bovine serum albumin (0.05%) was added to solutions containing dendrotoxin I (DTX-I) and margatoxin (MTX), in order to prevent non-specific binding of the blocker molecules to the surface of the experimental chamber.

Table 1.

Solutions

| A. External solutions | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution | NaCl (mm) | KCl (mm) | LiCl (mm) | CaCl2 (mm) | MgCl2 (mm) | Glucose (mm) | NaH2PO4 (mm) | NaHCO3 (mm) | TTX (nm) | TEA (mm) | Hepes (mm) | LiOH (mm) | pH |

| Standard | 115 | 5.6 | — | 2.2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 25 | — | — | — | — | 7.4 (O2–CO2) |

| Ca2+ free | 115 | 5.6 | — | — | 1 | 11 | 1 | 25 | — | — | — | — | 7.4 (O2–CO2) |

| 4 mm | 116.6 | 4 | — | — | 1 | 11 | 1 | 25 | — | — | — | — | 7.4 (O2–CO2) |

| 8 mm | 112.6 | 8 | — | — | 1 | 11 | 1 | 25 | — | — | — | — | 7.4 (O2–CO2) |

| 12 mm | 108.6 | 12 | — | — | 1 | 11 | 1 | 25 | — | — | — | — | 7.4 (O2–CO2) |

| Ca2+-freeo | 136.4 | 5.6 | — | — | 1 | 11 | — | — | — | — | 10 | — | 7.4 (NaOH total 4.6 mm) |

| High | 5 | 152.5 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 100 | — | 5 | — | 7.4 (KOH total 2.5 mm) |

| High -TEA | 5 | 152.5 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 100 | 1 | 5 | — | 7.4 (KOH total 2.5 mm) |

| 141 mm | — | 5.6 | 138 | — | 1 | 11 | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 7.4 (O2–CO2) |

| B. Internal solutions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution | NaCl (mm) | KCl (mm) | LiCl (mm) | Choline chloride (mm) | MgCl2 (mm) | EGTA (mm) | Hepes (mm) | pH (mm) |

| High | 5 | 144.4 | — | — | 1 | 3 | 10 | 7.3 (KOH total 10.6 mm) |

| x mm | x | 73.6 | — | 70 –x | 1 | 3 | 10 | 7.3 (KOH total 11.4 mm) |

| (x = 0, 10, 20, 30, 50 and 70 mm) | ||||||||

| 70 mm | — | 73.6 | 70 | — | 1 | 3 | 10 | 7.3 (KOH total 11.4 mm) |

Investigation of inside-out patches was performed in an additional small 0.2 ml bath as described previously (Safronov & Vogel, 1995). This procedure allowed us to obtain several inside-out patches from the same slice without its destruction due to perfusion with internal solutions containing high concentrations of K+ ions.

Current and voltage recordings

The patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass tubes (GC 150; Clark Electromedical Instruments, Pangbourne, UK). The pipettes used for single-channel recordings had a resistance of 3-13 MΩ. The resistance of the pipettes for whole-cell recordings ranged between 5 and 10 MΩ. All pipettes were fire polished directly before the experiments. The patch-clamp amplifier used in all voltage- and current-clamp experiments was a List EPC-7 (Darmstadt, Germany). An additional EPC-7 amplifier was employed in two-electrode experiments. The data were either directly filtered at 1 kHz and stored in a computer using commercially available software (pCLAMP; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) or they were filtered at 10 kHz and first stored in a digital tape recorder (DTR-1202; Biologic, Claix, France). For further analysis, these data were replayed from tape, low-pass filtered at 1 kHz and stored on disk. The frequency of digitization was at least twice as high as that of the filter. For calculation of the open probability (Po), a channel was considered as open if its amplitude exceeded 50% of the control level. Events shorter than 1 ms were ignored. Offset potentials were nulled directly before formation of the seal. Liquid junction potentials were not corrected. Traces recorded in current-clamp mode were digitized with an interval of 0.1 ms.

All numerical values are given as means ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The data points were fitted by linear or non-linear least-squares procedures. The errors of the fitting parameters are given as ± standard error (s.e.). All experiments were carried out at a room temperature of 22-25°C.

RESULTS

Whole-cell KNa channel currents

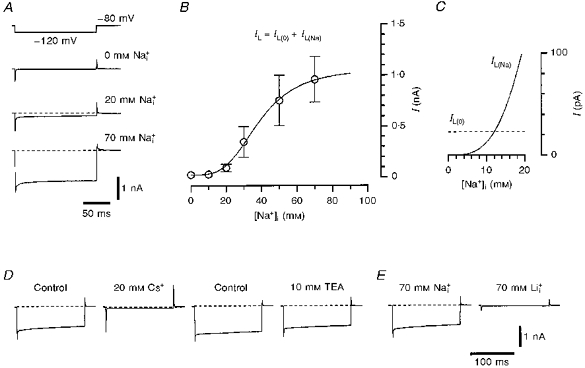

Small DRG neurones in the slice preparation have a high input resistance (Safronov et al. 1996) and, therefore, could be used as a suitable model for the investigation of whole-cell KNa channel currents. We identified whole-cell KNa channel currents as leakage currents which appeared during cell perfusion with Na+-containing internal solution. The leakage currents were visualized in Ca2+-free external solution by 150 ms hyperpolarizing voltage pulses to -120 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV. Recording pipettes were filled with 0, 10, 20, 30, 50 or 70 mm solutions. In these experiments, the unspecific leakage currents were very small (10-70 pA; membrane input resistance, 0.6-4 GΩ) immediately after membrane breakthrough and establishment of the whole-cell recording configuration. In experiments in which the pipettes contained 0 mm solution, the leakage currents remained unchanged during tens of minutes (Fig. 1A, top trace; see also Fig. 2C). When the pipettes were filled with 10-70 mm solutions, the small original leakage currents increased considerably within tens of seconds, as the neurone was perfused with the pipette solution. Recordings of the leakage currents made 4-6 min after their saturation are shown in Fig. 1A for 20 and 70 mm solutions (different neurones). Resting potentials in neurones perfused with 70 mm solution were close to -68 mV which corresponded to the equilibrium potential for K+ (EK) under the experimental conditions used (5.6 mm -85 mm ). Therefore, the component of leakage current which developed after neurone perfusion with internal Na+ was K+ selective. In order to study the concentration dependence of the leakage currents, measurements of their amplitudes were performed in five different neurones for each [Na+]i. The neurones used in these experiments were selected on the basis of similar size (diameter, 20-22 μm). The leakage current was 23.4 ± 5.6 pA in 0 mm (5 neurones) and its amplitude increased with increasing [Na+]i (Fig. 1B). The data points were fitted under the assumption that the total leakage current, IL, consisted of a Na+-independent (or unspecific) component, IL(0), and a Na+-activated component, IL(Na):

IL(0) was set to 23 pA, according to our measurements of leakage current in 0 mm solution, and IL(Na) was described by a standard isotherm:

where IL(Na),max is the maximum Na+-activated current, EC50 is the concentration for half-maximal current activation and nH is the Hill coefficient. The best fit of the data points was achieved with the following parameters: IL(Na),max, 1045 ± 56 pA; EC50, 38.7 ± 1.8 mm; and nH, 3.5. Results of the fit showed that at high Na+ concentrations IL(Na) was larger than the unspecific IL(0) component, by a factor of about 45. In order to compare the contributions of unspecific and Na+-activated conductances to the leakage current at low Na+ concentrations (0-20 mm), we plotted the amplitude of the IL(0) component (dashed line) and the fitted curve for the IL(Na) component (continuous line) on an enlarged scale (Fig. 1C). The functions crossed each other at a Na+ concentration of about 12 mm at which only 2.2% of IL(Na),max (23 of 1045 pA) was activated. Thus, at 12 mm , the contribution of IL(0) and IL(Na) to the total leakage current became equal and at [Na+]i higher than 12 mm IL(Na) dominated IL(0).

Figure 1. Na+-activated leakage currents in small DRG neurones.

A, whole-cell leakage currents activated by 150 ms hyperpolarizing voltage steps to -120 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV. Recordings were made from three different neurones using pipettes filled with 0, 20 and 70 mm solutions (indicated near the traces). B, dependence of the amplitude of the leakage currents on [Na+]i. The leakage currents were measured at the end of the hyperpolarizing pulse. Each point represents the mean leakage current (±s.e.m., where the error bar exceeds the symbol size) measured in five different neurones. It was supposed that the total leakage current, IL, consisted of a Na+-independent (unspecific) component, IL(0), and a Na+-activated component, IL(Na): IL = IL(0)+IL(Na). The fitting procedure is described in the text. C, IL(0) component (dashed line) and fitted curve for the IL(Na) component as a function of [Na+]i. D, leakage currents activated by a 150 ms voltage pulse from -80 to -120 mV in Ca2+-free solution (Control) and after addition of external 20 mm Cs+ and 10 mm TEA. Recordings were obtained from the same neurone perfused with 70 mm solution. E, leakage currents recorded from two neurones using pipettes filled with 70 mm and 70 mm solutions.

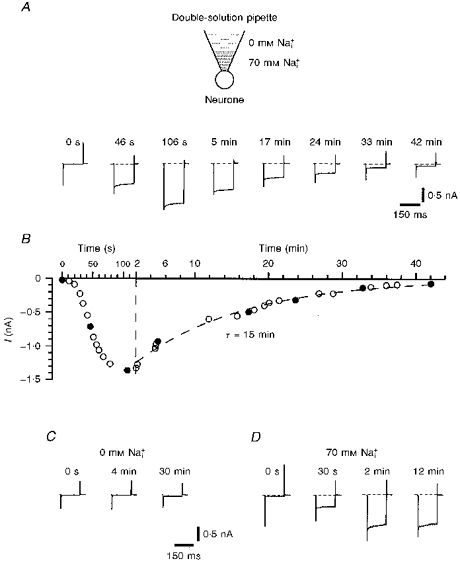

Figure 2.

Experiments with double-solution pipetteA, leakage currents activated by voltage pulses from -80 to -120 mV at different times after membrane breakthrough and establishment of the whole-cell recording mode. The tip of the double-solution pipette was filled with 70 mm solution and the rest of the pipette with 0 mm solution. A schematic drawing is shown at the top. B, amplitude of the leakage current as a function of time elapsed after membrane breakthrough. Data points during the first 2 min are given at a higher time resolution. Filled symbols correspond to original recordings shown in A. Kinetics of ‘recovery’ were fitted by a mono-exponential function with a time constant of 15 min. C, leakage currents recorded with a standard pipette filled with 0 mm solution only. D, development of the leakage current during an experiment with a standard pipette containing 70 mm only.

In amphibian axons, external 10 mm Cs+ almost completely suppressed the single KNa channels, whereas external 10 mm TEA blocked them only partially (Koh et al. 1994). In the present study, external 20 mm Cs+ almost completely blocked the leakage currents which developed in the neurone after perfusion with 70 mm solution (Fig. 1D; 4 neurones). Ten millimolar external TEA had only a small effect on the amplitude of the leakage currents (Fig. 1D; 7 neurones). The Na+-activated leakage currents were not blocked by 1 mm 4-AP, 100 nm DTX-I and 10 nm MTX (each in 3 neurones).

It has been shown that internal Li+ is not able to substitute for Na+ in KNa channel activation (Dryer, Fujii & Martin, 1989; Safronov & Vogel, 1996). In further experiments, we compared the whole-cell leakage currents recorded in small DRG neurones after perfusion with 70 mm and 70 mm solutions (Fig. 1E; 3 cells). It can be clearly seen that the leakage current in 70 mm solution was as small as that recorded in the neurones perfused with 0 mm solution (compare Fig. 1E with A).

Thus, the leakage currents recorded in small DRG neurones after perfusion with solutions demonstrated properties typical of Na+-activated K+ channels. It can be concluded that most of the leakage current was carried through KNa channels.

Experiments with double-solution pipettes

Under our experimental conditions, it was not possible to make more than one whole-cell recording from each neurone. In order to show the reversibility of the activation of the leakage current by internal Na+, a simple method of whole-cell recording with a pipette filled with two solutions (double-solution pipette) was used. A standard patch pipette for whole-cell recording was filled with two different solutions (Fig. 2A). The pipette was filled from the tip with 70 mm solution. The shank of the pipette was filled with 0 mm solution in a standard way by means of a syringe needle. During filling of the biphasic pipette it was important to ensure that the volume of the shank solution was much larger than that of the tip solution. Each double-solution pipette was used immediately after filling, since any time delay increased dilution of the Na+ concentration in the tip by diffusion from the shank solution. Under our experimental conditions a tight seal with the neuronal membrane was made within a minute after filling of the double-solution pipette.

At the moment at which the whole-cell configuration with a double-solution pipette was established, only very small leakage currents were observed (Fig. 2A at 0 s). Within the next 1-2 min, the amplitude of the leakage currents increased dramatically (‘development’), reaching values typical for 70 mm (see Fig. 1) indicating diffusion of the tip solution into the neurone. As diffusion of the 0 mm shank solution into the pipette tip reduced the [Na+]i in the neurone, a slow reduction of the leakage current amplitude (‘recovery’) was observed. The time course of the recovery could be fitted by a mono-exponential with a time constant of 15 min. The leakage current measured 42 min after establishment of the whole-cell configuration was almost as small as the initial current. Similar development and recovery of the leakage currents was seen in all four neurones examined.

The development of the leakage current during 1-2 min was in good agreement with the 15 s exchange time between pipette and cell solution reported for bovine chromaffin cells with a diameter of 12 μm (Fenwick, Marty & Neher, 1982), bearing in mind that the small DRG neurones were twice the size (diameter) and therefore had an 8 times larger internal volume. The time constant of the current development can also be calculated using an equation derived for diffusion of pipette solution into the cell (Marty & Neher, 1995; two-compartment model):

where R is the pipette resistance, V is the cell volume, D is the diffusion coefficient for Na+ and ρ is the resistivity of the pipette solution. Assuming that R is 10 MΩ, D is 10−5 cm2 s−1, ρ is 50 Ω cm, and that the cell is spherical with a diameter of 22 μm, τ will be 110 s.

It should be mentioned that the maximum amplitude of the leakage current and the time course of its recovery depended strongly on pipette geometry and relative volumes of tip and shank solutions. For example, the time course of the current recovery was prolonged if narrower pipettes were used. If the amount of tip solution was too small, then the maximum leak current amplitude recorded with a double-solution pipette was only about one-third of that recorded with a normal pipette containing 70 mm solution, probably because the 0 mm shank solution diffused into the tip before the neurone was completely perfused with the 70 mm tip solution. Therefore, an appropriate combination of pipette geometry and filling proportions played a major role in adjusting the amplitude and the time course of the leakage currents.

For comparison, development of the leakage current recorded using a standard pipette filled with either 0 or 70 mm is shown in Fig. 2C and D, respectively. The currents remained very small during a period of 30 min when the pipette contained 0 mm solution. With 70 mm solution, the leakage current developed within 2 min and then remained constant for tens of minutes.

Single-channel experiments

Single KNa channels were investigated in inside-out membrane patches in a small additional bath (Safronov & Vogel, 1995). The pipettes contained high- or Ca2+-freeo external solutions and the bath was perfused with internal solutions containing different Na+ concentrations.

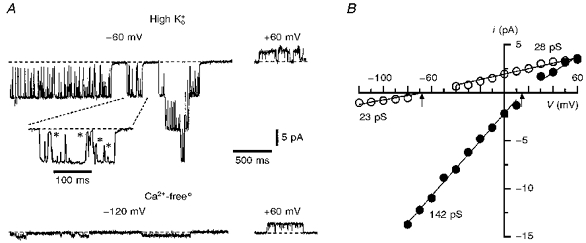

KNa channels were observed in approximately two-thirds of the total of more than seventy inside-out patches obtained with 10-13 MΩ pipettes. Each active patch contained one to eight KNa channels. The single-channel currents had large amplitudes and demonstrated typical substates (Fig. 3A). The current-voltage (i-V)curves for the main open state of the KNa channels are shown in Fig. 3B Least-squares fitting of the data points with a linear regression under the assumption that the EK is +15 mV in high- solution (155 mm -85 mm ) and -68 mV in Ca2+-freeo external solution (5.6 mm -85 mm ) gave conductances of 142.5 ± 1.6 pS (4 patches) for inward currents in high- solution and 28.3 ± 0.5 pS for outward currents in Ca2+-freeo external solution (4 patches). The channel conductance for inward currents in Ca2+-freeo solution measured in the potential range -80 to -120 mV was 23.0 ± 2.8 pS (4 patches).

Figure 3. Single KNa channel currents.

A, single-channel currents recorded from inside-out patches using pipettes filled with high- and Ca2+-freeo solutions in 70 mm bath solution. Holding potentials are indicated near the corresponding traces. Part of the recording is shown at a higher time resolution. Several substates are indicated by asterisks. B, i- V plots in high- (•; 4 patches) and Ca2+-freeo solutions (^; 4 patches). The arrows indicate the theoretical EK for both solutions.

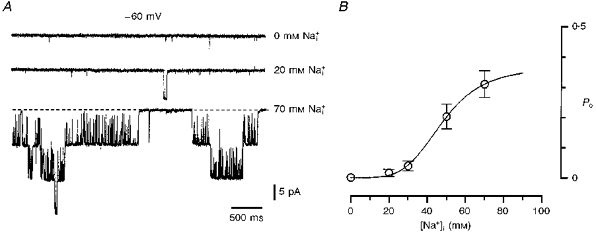

The effect of different [Na+]i on Po of KNa channels is shown in Fig. 4. The first channel activity was observed in the presence of 20 mm and it was much higher in 70 mm solution (Fig. 4A). Channel activation was not complete in 70 mm (Fig. 4B; 5 patches). The data were fitted with a standard isotherm:

where Po(max) is the maximum Po. The best fit of the data points was achieved with the following parameters: Po(max), 0.37 ± 0.03; EC50, 47.9 ± 2.3 mm; and nH, 4.4.

Figure 4. Effect of internal [Na+] on KNa channel activation.

A, recordings of single KNa channels in 0, 20 and 70 mm solutions. Holding potential was -60 mV. Inside-out patch; high- pipette solution. B, open probability (Po) as a function of [. Po was calculated from 1-2 min recordings at a membrane potential of -60 mV. Each point represents the mean (±s.e.m., where the error bar exceeds the symbol size) of measurements from five inside-out patches. The data points were fitted with the equation: Po = Po(max)/(1 + (EC50/[Na+]i)nH), where Po(max) (maximum Po) is 0.37 ± 0.03, EC50 is 47.9 ± 2.3 mm and nH (Hill coefficient) is 4.4.

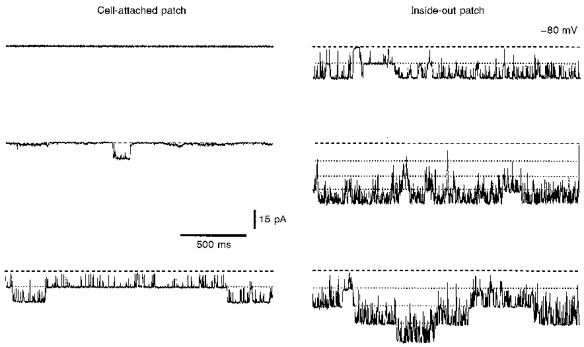

In order to determine the Po value in intact neurones at resting potential, KNa channel activity in cell-attached patches was recorded. The pipettes filled with high--TEA solution had a resistance of 3-9 MΩ and were held at 0 mV with respect to the bath solution. When the cell-attached recordings had been obtained, the patches were excised and transferred into an additional bath filled with 70 mm solution, where the maximum number of active KNa channels was determined. The Na+ dependence of the currents was confirmed by their disappearance in 0 mm solution (3 patches). In twenty-eight experiments the channels were silent in cell-attached patches but became active after patch excision (Fig. 5; top trace). In another fourteen cell-attached patches KNa channels were active with Po values ranging from 0.0003 to 0.43 (Fig. 5; middle and bottom traces). Even in one neurone the Po values varied considerably from patch to patch from 0 to 0.1. The mean P0 of KNa channels in forty-two cell-attached patches was 0.019 ± 0.010.

Figure 5. KNa channel activity in intact neurones.

Cell-attached recordings of channel activity in three different neurones. Recordings from three membrane patches before (cell attached; left) and after their excision (inside out; right). Pipette potential was 0 mV during cell-attached recording and -80 mV in inside-out mode. The pipettes contained high--TEA solution. For recording in the inside-out mode the patches were transferred to a bath containing 70 mm solution.

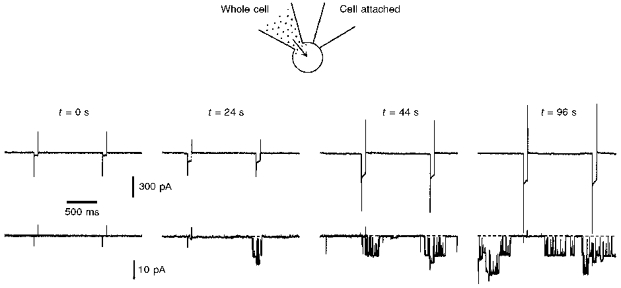

Two-electrode experiments

The purpose of the following experiments was to show a direct correlation between the appearance of Na+-activated leakage current and KNa channel activation. With two electrodes, we simultaneously recorded the changes in leakage currents (whole-cell electrode) and in single KNa channel activity (cell-attached electrode). The electrode for whole-cell recording was filled with 70 mm solution. The neurone was held at -80 mV and the leakage currents activated by 60 ms pulses to -120 mV were monitored each second. The electrode for cell-attached recording contained high--TEA solution and was voltage clamped at 0 mV with respect to the bath solution. Directly after membrane breakthrough (Fig. 6; t = 0 s) the leakage currents were very small and no single KNa channel activity was seen in the cell-attached patch. Approximately 20 s later (t = 24 s), the amplitude of the leakage current had increased and the first activity of KNa channels was recorded. Further increases in the amplitude of the leakage current (t = 44 and 96 s) were accompanied by corresponding increases in single KNa channel activity. The number of active KNa channels seen in this cell-attached patch during neurone perfusion with 70 mm solution was two. The maximum number of KNa channels in this patch was determined at the end of the experiment when the pipette used for the cell-attached recording was pulled away and an inside-out patch was formed in the main chamber containing Ca2+-free solution (141 mm Na+). In the excised patch, activity of the same two KNa channels was observed. A comparison of the channel activity in cell-attached patches during cell perfusion with 70 mm solution with that in inside-out patches allowed us to conclude that KNa channel sensitivity to was not changed after patch excision.

Figure 6. Simultaneous recordings of leakage and single KNa channel currents.

Simultaneous recordings of Na+-activated leakage current (top traces) and single KNa channel current (bottom traces) with two electrodes. The electrode used in whole-cell mode contained 70 mm solution. Holding potential was -80 mV and the leakage currents were activated each second by 60 ms pulses to -120 mV. The time elapsed (t) after membrane breakthrough is indicated above the traces. The resistance of the whole-cell pipette was 6 MΩ. The pipette used for cell-attached recordings was filled with high--TEA solution and had a resistance of 5 MΩ. The potential in the pipette during cell-attached recording was 0 mV with respect to the bath solution.

Similar correlation between leakage currents and KNa channel activity was recorded in a total of seven experiments with two electrodes.

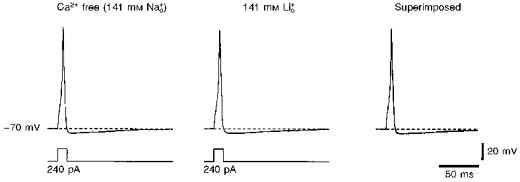

Current-clamp experiments

In current-clamp experiments we first compared the shapes of single action potentials recorded in external Ca2+-free and 141 mm solutions (Fig. 7), since it is known that Li+ ions readily permeate Na+ channels (Hille, 1972) but are not able to activate KNa channels (see Fig. 1E). The membrane potential in both solutions was kept at -70 mV by an injection of steady-state current through the recording pipette. The replacement of external Na+ with Li+ did not change the shape of the action potential (Fig. 7, superimposed traces; 15 neurones) leading to the conclusion that KNa channels do not contribute to the single action potential in small DRG neurones.

Figure 7. Influence of external Li+ on the shape of the action potential.

Action potentials evoked by short (12.5 ms) current pulses of 240 pA in external Ca2+-free and 141 mm solutions. Both action potentials are shown superimposed on the right. The membrane potential was kept at -70 mV in both solutions by injection of inward or outward steady-state currents. The pipette contained high- solution.

It has been shown for rat motoneurones that activation of KNa channels by local Na+ accumulation during trains of action potentials could result in a slow after-hyperpolarization (Safronov & Vogel, 1996). In contrast to motoneurones, the small DRG neurones studied here were not able to generate action potentials at high frequencies. They usually responded to sustained depolarizing current injection with a single spike only and, therefore, accumulation of intracellular Na+ during cell firing seemed to be unlikely.

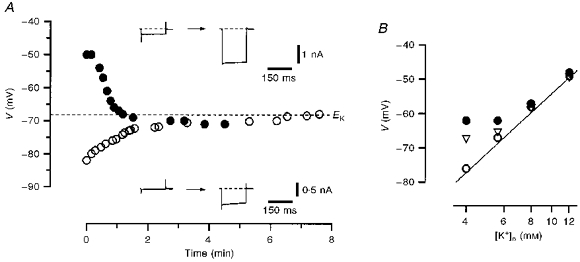

In further experiments the effect of on the membrane resting potential was studied (Fig. 8A). The slice was superfused with Ca2+-free (5.6 mm ) external solution and the pipettes were filled with 70 mm (85 mm ) solution. At the beginning of the experiment, the voltage-clamp mode was established and the original leakage currents in the neurone were recorded. Thereafter, the amplifier was switched to current-clamp mode and resting membrane potentials were measured. In a neurone with a small original unspecific leakage current and resting potential of about -80 mV (Fig. 8A; ^), diffusion of 70 mm pipette solution into the neurone produced an increase in leakage current accompanied by a membrane depolarization. This depolarization saturated at -68 mV which corresponds to the EK under these experimental conditions (5.6 mm -85 mm ). Another neurone with a larger original unspecific leakage current and a relatively low resting potential of -50 mV (Fig. 8A; •) demonstrated an increase in the leakage current and membrane hyperpolarization towards -68 mV as the pipette solution diffused into the cell. In a total of five neurones, regardless of their original resting potential, a shift of the membrane potential in the direction of the new EK during cell perfusion with internal Na+ was observed. These experiments indicated that perfusion of the neurone with can activate an additional K+ conductance and stabilize the resting potential in small DRG neurones, moving it towards EK.

Figure 8. Effect of internal Na+ on resting potential in small DRG neurones.

A, resting potential in two different neurones shown as a function of time elapsed after membrane breakthrough. One neurone had a small original leakage current and a resting potential of -82 mV (^). Another neurone with a large original unspecific leakage current had a depolarized resting potential of -50 mV (•). The bath contained Ca2+-free solution and the pipette solution was 70 mm . The theoretical EK for external Ca2+-free-internal 70 mm solutions (5.6 mm -85 mm ) of -68 mV is indicated by the dashed line. The leakage currents recorded immediately after membrane breakthrough and several minutes after their saturation are shown in the insets. B, resting potential as a function of external K+ concentration measured in neurones perfused with 0 (•), 10 (▿) and 30 mm (^) solutions. The straight line corresponds to the Nernst equation at 25 °C: 25.7 ln([K+]o/[K+]i), where the value given (25.7) is in mV and [K+]i is 85 mm.

The effect of external [K+] on the resting potential in small DRG neurones perfused with 0, 10 and 30 mm pipette solutions is shown in Fig. 8B. The resting potential in neurones perfused with 0 mm (•) deviated from the values predicted from the Nernst equation for K+ ions (continuous line) at potentials negative to -60 mV where most of the delayed rectifier K+ channels are closed. After perfusion of the neurone with 10 (▿) and 30 mm (^) solutions, a good correlation between measured and predicted potentials over a broader voltage range was observed (23 neurones).

DISCUSSION

The small DRG neurones with diameters of 20-25 μm studied in this work could be sensory neurones of types Aδ and C (Harper & Lawson, 1985a, 1985b), which convey information from pain and thermal receptors. According to the shape of their action potentials, these neurones were most probably C-type (Safronov et al. 1996). The high input resistance of small DRG neurones in the slice preparation (up to several gigaohms; Safronov et al. 1996) allowed us to use them as an appropriate model for investigating the macroscopic Na+-activated K+ currents.

Na+-activated K+ conductance in small DRG neurones

Up until now, studies of KNa channels were mainly focused on their single-channel properties (Dryer, 1991; Egan et al. 1992a, 1992b; Dryer, 1994; Koh et al. 1994; Safronov & Vogel, 1996) and little was known about the macroscopic KNa channel conductance in the neuronal membrane. The lack of knowledge about the macroscopic KNa channel conductance resulted from difficulties in recording a ‘pure’ whole-cell KNa channel current. Whole-cell KNa channel current was usually identified as a transient K+ current activated by Na+ influx through voltage-gated Na+ channels during membrane depolarization (Bader, Bernheim & Bertrand, 1985; Hartung, 1985; Dryer et al. 1989). Unfortunately, the currents recorded in such a way could result from insufficient voltage clamp of the neuronal membrane (Dryer, 1991). Furthermore, such currents could represent only a portion, perhaps a small one, of the total KNa channel conductance. Estimation of the total KNa channel conductance in neurones, however, is important for understanding KNa channel contribution to membrane resting conductance and therefore to the resting potential. In the present paper we have used another approach to study the whole-cell KNa channel conductance.

Na+-activated K+ whole-cell leakage currents recorded in the present study appeared only after cell perfusion with Na+-containing internal solutions. The dependence of the amplitude of the leakage currents on [Na+]i (EC50 = 38.7 mm and nH = 3.5) was similar to that observed for Po of single KNa channels (EC50 = 47.9 mm and nH = 4.4). The leakage currents were not activated by 70 mm . They were almost completely blocked by externally applied 20 mm Cs+ but were only slightly suppressed in the presence of 10 mm TEA. Our experiments with double-solution pipettes showed a reversibility of leakage current activation by internal Na+. Furthermore, in two-electrode experiments a direct correlation between the amplitude of the leakage current and the activity of single KNa channels was observed. All these results allowed us to conclude that the predominant part of the leakage current recorded in the present study was carried through Na+-activated K+ channels.

Single KNa channels in small DRG neurones with a conductance of 142 pS in 155 mm -85 mm solutions and with their sensitivity to internal [Na+] (EC50 = 47.9 mm) resemble those described in several other neuronal preparations (Dryer et al. 1989; Egan et al. 1992a, 1992b; Koh et al. 1994; Safronov & Vogel, 1996). As observed for KNa channels in chick brainstem neurones (Dryer, 1993) and rat motoneurones (Safronov & Vogel, 1996), the channels studied here did not show a pronounced ‘run-down’ in excised patches and their activity was not significantly reduced during tens of minutes.

The present experiments allowed us to estimate the total number and the density of KNa channels in intact small DRG neurones. The mean leakage current activated by a hyperpolarizing voltage step of 40 mV in the presence of 70 mm was 0.96 nA (Fig. 1B), giving a mean total KNa conductance of 24 nS. The unitary conductance of KNa channels measured for inward currents in external Ca2+-free-85 mm solutions was 23 pS (Fig. 3B) and the Po value at 70 mm was 0.31 (Fig. 4B). Thus, the total number of KNa channels in a small DRG neurone could be estimated as 3366. Assuming that the soma is a sphere with a diameter of 22 μm, one can calculate a mean channel density of 2.2 μm−2.

In contrast to those in amphibian axons (Koh et al. 1994) and somata of rat motoneurones (Safronov & Vogel, 1996), single KNa channels were found to be evenly distributed at high density in the somatic membrane of small DRG neurones. In thirteen experiments with inside-out patches containing active KNa channels, the maximum number of channels observed was 3.8 ± 0.6 per patch and the mean pipette resistance was 10.7 ± 0.3 MΩ, corresponding to a membrane patch area of 1.4 μm2 (Sakmann & Neher, 1995). Taking into account that active KNa channels were found in approximately two-thirds of all inside-out patches, the estimated channel density is 1.8 μm−2. This value is very similar to that obtained from experiments with macroscopic leakage currents.

Inactivating A and delayed rectifier (DRF, DR1, DR2 and DR3) K+ channels have been described recently in small DRG neurones in a slice preparation (Safronov et al. 1996). It is interesting to note that the KNa channel reported in the present study had the highest frequency of appearance in inside-out patches. To compare the whole-cell conductances of different K+ channels, we re-evaluated our recordings of voltage-gated K+ currents in small DRG neurones (Safronov et al. 1996). Inactivating and non-inactivating components of K+ currents had been separated using a standard voltage protocol with different prepulses. The total delayed rectifier conductance corresponding to DR1-, DR2-, DR3- and, in part, to DRF-channels was 14.2 ± 3.0 nS (8 neurones). The total inactivating conductance representing A- and DRF-channels was 5.4 ± 1.8 nS (8 neurones). Therefore, the maximum KNa conductance of 24 nS measured in 70 mm solution appears to be the largest K+ conductance observed in small DRG neurones studied so far.

A possible function of KNa channels in small DRG neurones

The functions of KNa channels in the neuronal membrane are not well understood at present. Numerical solution of the diffusion equation indicated that Na+ influx through voltage-gated Na+ channels cannot produce an increase in local Na+ concentration sufficient for activation of KNa channels even if the two types of channel are co-localized in the membrane (Dryer, 1991). It was also shown that KNa channels do not contribute to the shape of a single action potential in rat motoneurones (Safronov & Vogel, 1996). Therefore, the functions of KNa channels in the neuronal membrane have recently been considered in terms of local Na+ accumulation in restricted membrane compartments during repetitive firing (Koh et al. 1994; Safronov & Vogel, 1996). These functions can depend on, or can even be completely determined by, the channel distribution as well as the cell morphology and firing ability. In amphibian axons, KNa channels were shown to be co-localized with voltage-activated Na+ channels in the narrow nodal region (Koh et al. 1994). It was assumed that KNa channels could be activated due to cytoplasmic Na+ accumulation during high-frequency trains of action potentials. In the somata of rat motoneurones, KNa channels were found at increased densities in the vicinity of the cell processes, in the regions of most probable Na+ accumulation (Safronov & Vogel, 1996). Firing of action potentials even at a moderate frequency of about 30 Hz could produce a local Na+ accumulation leading to KNa channel activation resulting in a pronounced slow after-hyperpolarization. In contrast, small DRG neurones are known to generate action potentials only at very low frequencies of about 0.5-2 Hz (C-type neurones; Harper & Lawson, 1985b). Furthermore, the somata of DRG neurones do not possess an anatomical structure such as the node of Ranvier or the axon hillock with a high density of Na+ channels and large surface-to-volume ratio which could facilitate Na+ accumulation. Therefore, a local Na+ accumulation during repetitive firing seemed to be unlikely and functions of KNa channels may have no links to firing behaviour in small DRG neurones.

However, in the present study we show that small DRG neurones which are normally characterized by a high input resistance of several gigaohms (Safronov et al. 1996) have a large KNa channel conductance. The ratio of unspecific leakage current to the maximum Na+-activated K+ current was 1 to about 45 (23 pA to 1045 pA). The physiological level of intracellular Na+ measured in different neurones was 4-16 mm (Grafe, Rimpel, Reddy & ten-Bruggencate, 1982; Galvan, Dörge, Beck & Rick, 1984). Our experiments with whole-cell KNa channel currents indicated that, at an [Na+]i of about 10 mm, at which only 2.2% of KNa channel current is activated, the current can essentially contribute to membrane conductance. By normalizing the Po of 0.019 measured in cell-attached patches to the Po(max) of 0.37 obtained by fitting the data from inside-out patches (Fig. 4B), one can estimate that KNa channels in intact neurones show up to 5% of their maximum Po. Furthermore, cell perfusion with internal Na+ can stabilize the resting potential and can shift it in the direction of the EK. Therefore, it could be suggested that KNa channels in small DRG neurones participate in setting the resting potential under physiological conditions as well as contributing to its stabilization under pathophysiological conditions, like hypoxia, leading to a reduction in Na+-K+ pump activity and therefore to an increase in cytoplasmic Na+ concentration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr M. Bräu for critically reading the manuscript, and B. Agari and O. Becker for excellent technical assistance. Support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Vo188/16, 19) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Bader CR, Bernheim L, Bertrand D. Sodium-activated potassium current in cultured avian neurones. Nature. 1985;317:540–542. doi: 10.1038/317540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE. Na+-activated K+ channels and voltage-evoked ionic currents in brain stem and parasympathetic neurones of the chick. Journal of Physiology. 1991;435:513–532. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE. Properties of single Na+-activated K+ channels in cultured central neurons of the chick embryo. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;149:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90754-9. 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE. Na+-activated K+ channels: a new family of large-conductance ion channels. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:155–160. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90093-0. 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer SE, Fujii JT, Martin AR. A Na+-activated K+ current in cultured brain stem neurones from chicks. Journal of Physiology. 1989;410:283–296. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B, Takahashi T. A thin slice preparation for patch clamp recordings from neurones of the mammalian central nervous system. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;414:600–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00580998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan TM, Dagan D, Kupper J, Levitan IB. Na+-activated K+ channels are widely distributed in rat CNS and in Xenopus oocytes. Brain Research. 1992a;584:319–321. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90913-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan TM, Dagan D, Kupper J, Levitan IB. Properties and rundown of sodium-activated potassium channels in rat olfactory bulb neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992b;12:1964–1976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01964.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick EM, Marty A, Neher E. A patch-clamp study of bovine chromaffin cells and of their sensitivity to acetylcholine. Journal of Physiology. 1982;331:577–597. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan M, Dörge A, Beck F, Rick R. Intracellular electrolyte concentrations in rat sympathetic neurones measured with an electron microprobe. Pflügers Archiv. 1984;400:274–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00581559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafe P, Rimpel J, Reddy MM, ten-Bruggencate G. Changes of intracellular sodium and potassium ion concentrations in frog spinal motoneurons induced by repetitive synaptic stimulation. Neuroscience. 1982;7:3213–3220. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimann C, Magistretti J, Pozzi B. Sodium-activated potassium current in sensory neurons: a comparison of cell-attached and cell-free single-channel activities. Pflügers Archiv. 1992;422:287–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00376215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper AA, Lawson SN. Conduction velocity is related to morphological cell type in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1985a;359:31–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper AA, Lawson SN. Electrical properties of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones with different peripheral nerve conduction velocities. Journal of Physiology. 1985b;359:47–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung K. Potentiation of a transient outward current by Na+ influx in crayfish neurones. Pflügers Archiv. 1985;404:41–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00581488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. The permeability of the sodium channel to metal cations in myelinated nerve. Journal of General Physiology. 1972;59:637–658. doi: 10.1085/jgp.59.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama M, Kakei M, Sato R, Shibasaki T, Matsuda H, Irisawa H. Intracellular Na+ activates a K+ channel in mammalian cardiac cells. Nature. 1984;309:354–356. doi: 10.1038/309354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh D-S, Jonas P, Vogel W. Na+-activated K+ channels localized in the nodal region of myelinated axons of Xenopus. Journal of Physiology. 1994;479:183–197. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty A, Neher E. Tight-seal whole-cell recording. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-Channel Recording. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Safronov BV, Bischoff U, Vogel W. Single voltage-gated K+ channels and their functions in small dorsal root ganglion neurones of rat. Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:393–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronov BV, Vogel W. Single voltage-activated Na+ and K+ channels in the somata of rat motoneurones. Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:91–106. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronov BV, Vogel W. Properties and functions of Na+-activated K+ channels in the soma of rat motoneurones. Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:727–734. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B, Neher E. Geometric parameters of pipettes and membrane patches. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-Channel Recording. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 637–650. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. Membrane currents in visually identified motoneurones of neonatal rat spinal cord. Journal of Physiology. 1990;423:27–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]