Abstract

We have examined the properties of intracellular nucleotide-mediated gating of K+ channel constructs composed of the sulphonylurea receptor 2B and the inwardly rectifying K+ channel subunits Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 (SUR2B/Kir6.1 and SUR2B/Kir6.2 complex K+ channels) heterologously expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells. In the cell-attached form, both types of K+ channel were activated by pinacidil.

In inside-out (IO) patches, the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channels opened spontaneously and were inhibited by intracellular ATP (ATPi). Pinacidil attenuated the ATPi-mediated channel inhibition in a concentration-dependent manner. In contrast, the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels required intracellular nucleoside di- or tri-, but not mono-, phosphates for opening. The potency of adenine, guanine or uracil nucleotides to activate SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels was enhanced by pinacidil.

In the presence of pinacidil, adenine and guanine, but not uracil, nucleotides exhibited bell-shaped concentration-dependent activating effects on SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels. This was due to channel inhibition caused by adenine and guanine nucleotides, which was unaffected by pinacidil.

From power density spectrum analysis of SUR2B/Kir6.1 currents, channel activation could be described by the product of two gates, a nucleotide-independent fast channel gate and a nucleotide-dependent slow gate, which controlled the number of functional channels. Pinacidil specifically increased the potency of nucleotide action on the slow gate.

We conclude that Kir6.0 subunits play a crucial role in the nucleotide-mediated gating of SUR/Kir6.0 complex K+ channels and may determine the molecular mode of pinacidil action.

The ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel is an inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channel that is inhibited by intracellular ATP (ATPi) and activated by intracellular nucleoside diphosphates (NDPi), and thus provides a link between cellular metabolism and excitability (Ashcroft, 1988; Terzic et al. 1995). The channel is associated with diverse cellular functions, such as insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, shortening of cardiac action potential and cellular loss of K+ ions during metabolic inhibition in heart, regulation of skeletal muscle excitability and control of vascular smooth muscle tone (Ashcroft, 1988; Edwards & Weston, 1993; Nelson & Quayle, 1995). It is inhibited by sulphonylurea derivatives, such anti-diabetic agents as tolbutamide and glibenclamide, and activated by K+ channel opening drugs (KCOs) such as pinacidil, nicorandil and diazoxide (Quast, 1992; Edwards & Weston, 1993).

KATP channels are heteromers composed of an inwardly rectifying K+ channel subunit (Kir) and a receptor for sulphonylurea drugs (SUR) (Aguilar-Bryan et al. 1995; Inagaki et al. 1995a; Sakura et al. 1995; Inagaki et al. 1996; Isomoto et al. 1996). Electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of the expressed channels and the tissue distribution of mRNAs of various SURs and Kir subunits have indicated that SUR1/Kir6.2 and SUR2A/Kir6.2 complex channels represent the pancreatic β-cell and cardiac myocyte KATP channels, respectively (Inagaki et al. 1995a; Sakura et al. 1995; Inagaki et al. 1996; Okuyama et al. 1998), and also suggest that SUR2B may be a subunit constituting the smooth muscle KATP channel (Isomoto et al. 1996). However, the KCO-sensitive K+ channel described in vascular smooth muscle cells, which was named the NDP-dependent K+ (KNDP) channel (Beech et al. 1993), exhibits completely different properties from the classical KATP channels (Kajioka et al. 1991; Beech et al. 1993); it does not open spontaneously in the absence of ATPi and requires intracellular nucleotides, such as ATP, GDP and UDP, to open. Its single-channel conductance is much smaller than that of classical KATP channels. Yamada et al. (1997) showed that the K+ channel composed of SUR2B and Kir6.1, another Kir subunit of the Kir6.0 subfamily (Inagaki et al. 1959b), could reconstitute the major physiological and pharmacological properties of the KNDP channel and suggested that the vascular KNDP channel may be a heteromer of SUR2B and Kir6.1. However, the mode of regulation of the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel by intracellular nucleotides and KCOs has not yet been fully clarified.

In this study, the nucleotide-mediated gating behaviour of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel heterologously expressed in HEK293T cells and its modification by a KCO, pinacidil, have been further investigated and compared with the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel. We found that the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel required nucleoside di- and triphosphates to open, an effect which was enhanced by pinacidil. At high concentrations, adenine and guanine nucleotides, but not uracil nucleotides, showed an inhibitory effect on channel activity, which was insensitive to pinacidil. This was in contrast to the observation that the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel opened spontaneously and was inhibited by submillimolar concentrations of ATPi. Pinacidil attenuated the ATPi-mediated inhibitory gating and activated the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel. We conclude that, although SUR subunits contain the critical binding sites for KCOs and intracellular nucleotides, the Kir subunits seem to influence the way in which the entire SUR/Kir functional channel complex reacts to these compounds.

METHODS

Functional co-expression of SUR2B and Kir6.0

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) containing the coding sequence of cloned cDNAs of mouse SUR2B and mouse Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 subunits using LipofectAMINE (Gibco BRL), according to the manufacturer's instructions as previously described (Isomoto et al. 1996).

Solutions and chemicals

The bath was perfused with internal solution containing (mM): 140 KCl, 5 EGTA, 2 MgCl2 and 5 Hepes-KOH (pH 7.3), in which the free Mg2+ concentration was 1.4 mM. The pipette solution contained (mM): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2 and 5 Hepes-KOH (pH 7.4). ATP, GTP, UTP, GDP, AMP, GMP, UMP and glibenclamide were purchased from Sigma; ADP was from Oriental Yeast (Tokyo, Japan); UDP was from Boehringer Mannheim; and pinacidil was from RBI (Natick, MA, USA). When the nucleotides were added to the internal solution, the free Mg2+ concentration was adjusted to 1.4 mM by supplementing MgCl2 with reference to the stability constants of magnesium-nucleotide complexes (Dawson et al. 1986; Sigel, 1987).

Electrophysiological recording and noise analysis of single-channel current fluctuation

The channels expressed in HEK293T cells were analysed by using the cell-attached and inside-out variants of the patch clamp method as previously described (Isomoto et al. 1996; Yamada et al. 1997). The tips of patch electrodes were coated with Sylgard and heat polished. Tip resistance was 5–8 MΩ when filled with the pipette solution. Channel currents were recorded using a patch clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200A, Axon Instruments) and stored on video cassette tapes through a PCM converter system (VR-10B, Instrutech Corp., Great Neck, NY, USA). Channel activity was measured at -60 mV. All experiments were performed at room temperature (∼25°C).

To avoid the ambiguities in analysing open-close kinetics in patches that contained multiple levels of channels, we used the spectral analysis technique. The data were reproduced and low-pass filtered at 5 kHz (-3 dB) and high-pass filtered at 0.5 Hz (-3 dB) with a Butterworth filter (Programmable Filter 3625; NF Electronic Instruments, Yokohama, Japan) and digitized at 10 kHz as previously described (Hosoya et al. 1996). The data were divided into short segments of 65 536 points and multiplied point by point using a Blackman-Harris window function and then Fourier transformed following an algorithm for the fast Fourier transform. Power density spectra were calculated and averaged over ten to twenty segments. The background noise was determined in each patch when the channel was completely closed in nucleotide-free solution. The power spectrum derived from background noise was calculated, averaged in ten segments and subtracted from that during channel opening. The averaged power density spectrum of current fluctuations thus obtained was fitted with the sum of two Lorentzian functions using the least-squares method between 0.5 Hz and 2 kHz:

where S(x) is the power spectral density at the frequency of x, S1 and S2 are the zero-frequency asymptotes of Lorentzian components 1 and 2, respectively, and F1 and F2 are the corner frequencies of the components 1 and 2, respectively. Rate constants were calculated from F1, F2, S1, S2 and τo as previously described (Hosoya et al. 1996). τo is the mean open time.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. The symbols in the figures indicate the means and the vertical bars indicate s.e.m.

RESULTS

Comparison of nucleotide and pinacidil regulation of SUR2B/Kir6.2 and SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels

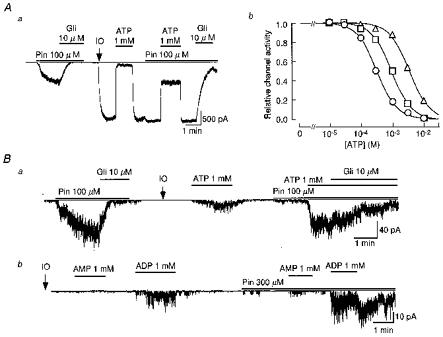

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with SUR2B, a smooth muscle type SUR (Isomoto et al. 1996), and either Kir6.2 or Kir6.1. In cell-attached membrane patches of both types of cell, pinacidil (100 μm) added to the bathing solution induced openings of K+ channels that were inhibited by glibenclamide (10 μm) (Fig. 1Aa3 and Ba). The pinacidil-induced K+ channels had a unitary conductance of ∼80 pS in the cells transfected with SUR2B/Kir6.2 and ∼35 pS in those transfected with SUR2B/Kir6.1 (not shown, see Isomoto et al. 1996; Yamada et al. 1997).

Figure 1. Comparison of nucleotide and pinacidil regulation of SUR2B/Kir6.2 and SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels.

Aa, representative single-channel recording of the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel illustrating the effects of pinacidil (Pin) and glibenclamide (Gli) in the cell-attached and excised (arrow and IO) inside-out membrane patch. Ab, apparent antagonism of ATP-evoked inhibition of SUR2B/Kir6.2 channels induced by pinacidil. Each symbol shows the ATP-induced channel inhibition in the absence (○) or presence of pinacidil (□, at 100 μm; and ▵, 300 μm). The continuous lines were fitted with eqn (1). B, representative single-channel recordings of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels illustrating the effects of ATP (a), AMP (b) and ADP (b) in the absence or presence of pinacidil. At the points indicated by IO, the patches were excised from their cells. In each membrane current recording the zero current level is indicated by a thin horizontal line.

The SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel exhibited the properties of classical ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels (Fig. 1A). Upon formation of the inside-out (IO) patch, the channel opened spontaneously and was almost completely inhibited by application of 1 mM intracellular ATP (ATPi) in the presence of 1.4 mM Mg2+. Upon washout of ATP, channel activity recovered to the maximum level. Although pinacidil (100 μm) did not affect maximum channel activity, it attenuated ATPi-mediated channel inhibition. Glibenclamide (10 μm) inhibited channel activity to ∼10 %. Channel activity in the presence of 1 mM ATPi and 100 μm pinacidil was roughly equivalent to that evoked by pinacidil (100 μm) in the cell-attached patch. Similar results were obtained in five out of five patches.

Figure 1Ab3 depicts the relationships between the concentration of ATPi ([ATP]i) and SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel activity in the presence of two concentrations of pinacidil ([pinacidil]) which were obtained in three IO patches. The relationships could be fitted with the following Hill equation:

| (1) |

where IC50 is the [ATP]i at which 50 % of inhibition occurs, and n is the Hill coefficient. In the control, the IC50 value and n were estimated as 315 μm and 1.38, respectively. The relationship was shifted to the right by pinacidil in a concentration-dependent fashion. As [pinacidil] was increased to 100 and 300 μm, the IC50 values were increased to 955 μm and 3.45 mM, respectively, while the Hill coefficients remained constant (1.40 and 1.41, respectively).

In HEK293T cells co-transfected with SUR2B and Kir6.1, a small amount of channel activity could be observed in a cell-attached patch. The net open probability of channels in the patch (NPo) was 0.95 in Fig. 1B a. Similar basal opening of the channel whose NPo values ranged from 0.55 to 1.45 was detected in 63 out of 203 patches. The remaining 150 patches did not exhibit significant basal channel openings. In Fig. 1B a, pinacidil added to the bath increased the channel NPo to 32.11, which was then decreased by 10 μm glibenclamide to 2.18. The channel did not open spontaneously upon formation of an IO patch (Fig. 1B a). Spontaneous channel opening was not detected even when the IO patch was made in Mg2+-free internal solution. ATP (1 mM) added to the internal side of the IO patch membrane caused a weak activation of the channel (NPo= 6.02). After washout of ATP, the channel openings disappeared quickly. Pinacidil (100 μm) alone induced only a marginal channel opening (NPo= 1.26). In the presence of pinacidil (100 μm), ATP (1 mM) induced a channel activation equivalent to that induced by the drug in the cell-attached form (NPo= 24.30). This channel activity was maintained constant in the presence of ATP for at least ∼5-7 min (n = 5), but inhibited to ∼30 % by 10 μm glibenclamide within 2–3 min. The inhibiting effect of glibenclamide seemed to be weaker in the IO patch than in the cell-attached form. Similar results were obtained in six out of six patches.

In Fig. 1B b, we examined the effects of AMP and ADP on the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel in an IO patch. Under control conditions in the absence of pinacidil, 1 mM AMP did not induce any channel openings, while 1 mM ADP added to the same patch activated the channel (NPo= 2.25). Pinacidil (300 μm) was added to the internal solution and caused a marginal channel opening. In the presence of pinacidil, AMP now induced a slight activation of the channels while the response to ADP was prominently enhanced (NPo= 4.58). Even after washout of ADP, in the continued presence of pinacidil, channel activity remained high for 1–5 min. Similar results were obtained in five out of five patches. Other nucleoside monophosphates such as GMP (1 mM) and UMP (1 mM) did not induce significant channel openings even in the presence of pinacidil (n = 6 for each, data not shown). Thus, the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel seems to possess an activation gating mechanism which is sensitive to ATP and ADP, but not to nucleoside monophosphates.

Nucleoside triphosphate (NTP)-induced SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity and its modification by pinacidil

The effect of pinacidil on nucleoside triphosphate-induced opening of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel is shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2Aa3 depicts an example of such experiments. As reported previously (Yamada et al. 1997), ATP (300 μm, 1 and 3 mM) added to the internal side of an IO patch induced channel opening in a concentration-dependent fashion (NPo= 0, 0.21 and 1.42, respectively, in the patch of Fig. 2Aa3). When the ATP concentration was further increased to 10 mM, channel activity decreased, which resulted in a bell-shaped concentration-response relationship (Fig. 2Ab3, ○). When pinacidil (10 μm) was added to the same IO patch, as little as 10 μm ATP was able to induce some channel opening (NPo= 1.99). On increasing [ATP] to 100 μm and then to 1 mM, the channel NPo was first enhanced to 14.50 and then decreased to 5.95. In the presence of 300 μm pinacidil, channel NPo was 28.32 at 10 μm, 15.81 at 100 μm and 8.46 at 1 mM ATP.

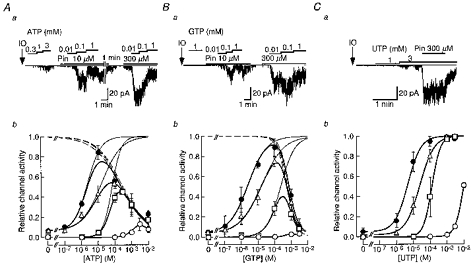

Figure 2. The effects of pinacidil on NTP-induced SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel openings in inside-out patches.

Top panels, representative single-channel current recordings of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity induced by internal ATP (Aa), GTP (Ba) and UTP (Ca) in the absence or presence of pinacidil at the indicated concentrations (10 or 300 μm). In each single-channel current recording, IO indicates the moment when the membrane patch was excised from the cell and the zero current level is indicated by thin horizontal lines. Lower panels, NTP concentration-response relationships for channel activation in the absence (○) or presence of pinacidil (□, at 10 μm; ▵, 100 μm and •, 300 μm). The number of observations for each point are 3–11 for ATP (Ab), 3-8 for GTP (Bb) and 3–8 for UTP (Cb). The thick continuous lines in Ab and Bb were fitted by the multiplication of eqn (2) and eqn (3). Thin continuous lines and dashed lines show the estimated ATP- or GTP-induced activation and inhibition curves, respectively. The continuous lines in Cb were fitted with eqn (2).

In Fig. 2Ab3, the relationships between [ATP]i and channel activity in the presence of different concentrations of pinacidil obtained from three to eleven different membrane patches are depicted. They were all bell shaped. We quantitatively analysed each relation in the presence of various concentrations of pinacidil. Based on the observation obtained from the effects of UTP and UDP on channel activity, which will be described below (Figs 2C and 3B), we assumed that the net activity of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel was the product of ATP-mediated activation gating and ATP-mediated inhibitory gating, and that the ATP-mediated activation of the channel would reach a saturating level if the inhibitory gating was not present. The saturating level was estimated as the magnitude of current induced by 3 mM UDP in the presence of 300 μm pinacidil (see Fig. 3B). The current magnitude induced by 10 μm ATP in the presence of 300 μm pinacidil was 0.84 ± 0.07 (n = 6) of the saturating level. The current amplitude at each [ATP] was expressed with reference to the saturating level. The calculated curves for activation and inhibition of the channel at each [pinacidil] are shown in Fig. 2Ab. For each concentration of pinacidil, the activation curve was fitted with eqn (2), while the inhibition curve was fitted with eqn (3):

| (2) |

| (3) |

where EC50 is the [ATP]i at which 50 % activation occurs, IC50 is the [ATP]i at which 50 % inhibition occurs, and n1 and n2 are the Hill coefficients of activation and inhibition curves, respectively. For the data shown in Fig. 2Ab3, the EC50 values of ATPi were 68.3, 15.7 and 2.27 μm in the presence of 10, 100 and 300 μm pinacidil, respectively, while IC50 values were not affected by pinacidil (251, 237 and 198 μm at 10, 100 and 300 μm pinacidil, respectively). The value of n1 seemed to be variable (1.59, 0.74 and 1.08 in the presence of 10, 100 and 300 μm pinacidil), while n2 was unaffected by pinacidil (0.52, 0.61 and 0.61 at 10, 100 and 300 μm pinacidil). Therefore, we concluded that pinacidil specifically enhanced the potency of ATP to activate the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel but did not affect the ATP-mediated inhibitory effect on gating.

Figure 3. Effects of pinacidil on NDP-induced SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel openings in inside-out patches.

Aa and b, representative single-channel recordings of ADP-induced channel openings in the absence (a), or presence of 300 μm pinacidil (Pin) (b). Ac, concentration-response relationships for ADP-induced activation of the channels in the absence (○) or presence of 300 μm pinacidil (□). The number of observations for each point was 3-5. Ad, concentration-response relationships for GDP-induced activation of the channels in the absence (○) or presence of 300 μm pinacidil (□). The number of observations for each point was 3-7. Ba, representative single-channel recording of UDP-induced channel openings in the absence or presence of 10 μm pinacidil. Bb, concentration-response relationships for UDP-induced activation of the channels in the absence (○) or presence of pinacidil (□, at 10 μm; and ▵, 300 μm). The number of observations for each point was 3-7. In each single-channel recording, IO indicates the moment when the patch was excised from the cell and the zero current level is indicated by a thin horizontal line. The thick continuous lines in Ac and d were fitted by multiplication of eqn (2) and eqn (3). Thin continuous lines and dashed lines show the estimated ADP- or GDP-induced activation and inhibition curves, respectively. The continuous lines in Bb were fitted with eqn (2).

We next examined the effect of pinacidil on GTP induction of channel activity. Although GTP barely activated the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels in the absence of pinacidil, it clearly induced channel opening in the presence of pinacidil (Fig. 2Ba3 and b). The relationships between the concentration of GTP ([GTP]) and channel activity at different [pinacidil] were also bell shaped, due to channel inhibition by high [GTP]. As [pinacidil] was increased, the relation shifted to the left and its peak was enhanced in a concentration-dependent fashion. The current magnitude induced by 100 μm GTP in the presence of 300 μm pinacidil was 0.89 ± 0.09 (n = 5) of the saturating level induced by 3 mM UDP in the presence of 300 μm pinacidil. Each [GTP]-channel activity relation at different [pinacidil] was analysed by fitting the data with eqns (2) and (3). The EC50 values of GTP were 236, 17.5 and 2.58 μm, while the IC50 values were 565, 592 and 730 μm, in the presence of 10, 100 and 300 μm pinacidil, respectively (Fig. 2B b). Thus, similar to the case of ATP, the GTPi-mediated activation gating of the SUR/Kir6.1 channel was enhanced by pinacidil, while the inhibitory effect of GTP was not affected.

UTP induced channel openings at concentrations higher than 3 mM in the absence of pinacidil (Fig. 2Ca3 and b). Pinacidil (10-300 μm) enhanced the UTP-induced channel openings in a concentration-dependent fashion. In contrast to the cases of ATP and GTP, however, UTP even at high concentrations (1-3 mM) did not inhibit channel activity (Fig. 2Ca3 and b). Thus, the relationships between [UTP] and channel activity in the presence of various [pinacidil] were not bell shaped but sigmoidal (Fig. 2C b). As [pinacidil] was increased, the relationship was shifted to the left, but the maximal level of channel activity remained constant. The maximal channel activity induced by UTP in the presence of pinacidil was 0.99 ± 0.01 (n = 5) of that induced by 3 mM UDP in the presence of 300 μm pinacidil. The UTP-channel activity relationships could be fitted with Hill eqn (2). In the control, the EC50 value and n1were estimated as 9.82 mM and 1.72, respectively. Pinacidil at 10, 100 and 300 μm decreased the EC50 values to 128, 24.5 and 4.81 μm with Hill coefficients of 1.72, 1.02 and 1.11, respectively.

Nucleoside diphosphate (NDP)-induced SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity and its modification by pinacidil

We conducted similar experiments and applied the same analysis to the effects of nucleoside diphosphates such as ADP, GDP and UDP, and their modification by pinacidil (Fig. 3). In these experiments, the NDP-induced channel activity was normalized with reference to the saturating channel activity induced by 3 mM UDP and 300 μm pinacidil in each patch.

In the IO patch shown in Fig. 3Aa3, 1 mM ADP induced channel openings to 22 % (NPo= 1.56) of the saturating level (NPo= 6.96). The channel activity with 3 mM ADP was 7 % (NPo= 0.47) of the saturating level (Fig. 3Aa3). In the presence of 300 μm pinacidil, 10 μm ADP induced the equivalent of the saturated channel activity (Fig. 3Ab3). When ADP was increased to 1 and 3 mM, channel activity decreased to 46 and 28 % of the saturating level, respectively. Similar results were obtained when GDP was applied to the internal side of patch membranes (Fig. 3Ad3, ○).

Figure 3Ac3 and d depicts the concentration-response relationships for ADP- and GDP-induced channel activity in the absence and presence of 300 μm pinacidil. The relationships were bell shaped as we have seen for ATP and GTP (Fig. 2). In control conditions in the absence of pinacidil, the maximum channel activity induced by ADP and GDP was ∼20-40 % of the saturating channel activity. For both ADP and GDP, 300 μm pinacidil enhanced the peak channel activity induced by these nucleotides to the saturating level, and the relationship was shifted to the left (Fig. 3Ac3 and d). The concentration-response relationships in the absence and presence of pinacidil were analysed using eqns (2) and (3). The EC50 values for ADP were 1.19 mM and 2.12 μm in the absence and presence of pinacidil, respectively, while those for GDP were 975 μm and 3.18 μm, respectively. The IC50 values for ADP were 1.08 mM and 558 μm, while those for GDP were 2.17 mM and 1.46 mM, in the absence and presence of pinacidil, respectively. Thus, similar to its effect on the responses to ATP and GTP, pinacidil also enhanced the potency of ADP or GDP to induce channel activity, without significantly affecting the inhibitory effects of these nucleotides.

We next examined the effects of UDP on SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity. UDP (0.1-10 mM) was applied to the internal side of an IO patch in the absence and in the presence of 10 μm pinacidil (Fig. 3B a). UDP induced channel opening in a concentration-dependent fashion. In the absence of pinacidil, at least 1 mM UDP was required to stimulate channel openings. In the presence of pinacidil, 100 μm UDP markedly activated the channels. Unlike ADP and GDP, UDP did not inhibit channel activity even at 10 mM. The channel activity induced by 10 mM UDP alone was ∼80 % of the saturating channel activity in the presence of 10 μm pinacidil. Figure 3Bb3 depicts the relationships between the concentration of UDP ([UDP]) and channel activity in the presence of 0, 10 and 300 μm pinacidil. The data were obtained from three to seven different patches. The relationships could be fitted with Hill eqn (2). In the absence of pinacidil, the EC50 value and n1 for UDP were estimated as 3.87 mM and 1.45, respectively. Pinacidil shifted the [UDP]-channel activity relationship to the left in a concentration-dependent fashion. The EC50 values were 102 and 3.61 μm in the presence of 10 and 300 μm pinacidil, respectively. The Hill coefficients were 0.99 and 0.86 at 10 and 300 μm pinacidil, respectively. Therefore, the potency of UDP to induce channel opening was enhanced by pinacidil in a concentration-dependent fashion.

Kinetic analysis of pinacidil modification of UTP and UDP-induced SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel opening

To obtain further insights into the mechanism of nucleotide-mediated activation of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel and its modification by pinacidil, the channel currents recorded in the presence of various concentrations of nucleotides and pinacidil were analysed using spectral analysis techniques (Figs 4 and 5). These experiments utilized UTP and UDP, since we have shown that they do not provoke significant inhibition of channel activity.

Figure 4. Effects of UTP and UDP on the power density spectra of current fluctuations of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel.

A, power density spectra calculated from recordings shown in Fig. 2C a in the presence of 3 mM UTP (a) and 3 mM UTP plus 300 μm pinacidil (b). B, power density spectra calculated from recordings obtained with 10 μm UTP (a) and 100 μm UTP in the presence of 100 μm pinacidil (b). C, power density spectra calculated from the recording shown in Fig. 3B a with 1 mM UDP (a) and 10 mM UDP (b). Each spectrum could be fitted with the sum of two Lorentzian functions. F1 and F2 indicate the corner frequencies of the slow and fast Lorentzian components, respectively. S1/S2 represents the ratio of the power at 0 Hz of the two components.

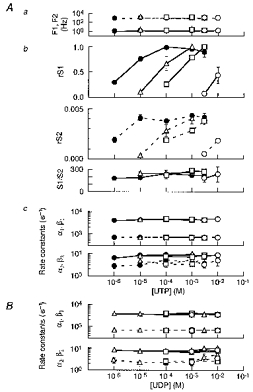

Figure 5. Spectral parameters of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activation induced by UTP and UDP.

A, concentration-dependent activation of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels by UTP in the absence (○) or presence of pinacidil (□, at 10 μm; ▵, 100 μm; and •, 300 μm). a, F1 (continuous line) and F2 (dashed line). b, relative S1 (rS1) and relative S2 (rS2) and S1/S2 ratio. c, the rate constants for the fast gating transitions, α1 (continuous line) and β1 (dashed line) in the upper panel, and α2 (continuous line) and β2 (dashed line) in the lower panel. B, the rate constants for the fast gating transitions, α1 (continuous line) and β1 (dashed line) in the upper panel, and α2 (continuous line) and β2 (dashed line) in the lower panel calculated and plotted against [UDP] in the absence (○) or presence of pinacidil (□, at 10 μm; and ▵, 300 μm).

Figure 4A shows the power density spectra of UTP-induced current fluctuations constructed from the recording shown in Fig. 2C a. The spectra were well fitted with the sum of two Lorentzian curves. In Fig. 4Aa3, the corner frequencies of the slow (F1) and fast (F2) Lorentzian components with 3 mM UTP were 1.57 and 857 Hz, respectively. The values were not altered significantly in the presence of 300 μm pinacidil (1.26 and 836 Hz, respectively). The powers at 0 Hz of the two components (S1 for slow and S2for fast components) were 0.205 and 0.00113 pA2 s, respectively, in the presence of 3 mM UTP. The addition of 300 μm pinacidil increased S1 to 4.23 and S2 to 0.0192 pA2 s. The S1/S2 ratio, however, remained at ∼200 in the absence as well as in the presence of pinacidil. Figure 4B shows the power density spectra obtained at different [UTP] in the presence of 100 μm pinacidil. The corner frequencies and the S1/S2 ratio were similar in both cases, while the S1 and S2values were increased in a concentration-dependent fashion: S1and S2were 0.474 and 0.00223 pA2 s in the presence of 10 μm UTP plus 100 μm pinacidil; and 2.037 and 0.00713 pA2 s in the presence of 100 μm UTP plus 100 μm pinacidil.

UDP and pinacidil showed similar effects on the power spectra of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity (Fig. 4C). Fig. 4Ca3 and b exhibits the power density spectra of UDP-induced current fluctuations constructed from the recording shown in Fig. 3B a. The corner frequencies of the slow (F1) and fast (F2) components at 1 mM UDP were 1.11 and 838 Hz, respectively (Fig. 4C a). They were not changed significantly by increasing UDP to 10 mM (Fig. 4C b). In contrast, the S1and S2 values were increased from 0.34 and 0.00297 pA2 s at 1 mM UDP to 4.13 and 0.0250 pA2 s at 10 mM UDP, respectively. The S1/S2 ratio at 10 mM UDP, however, was similar to that at 1 mM UDP. As shown for UTP (Fig. 4A), the F1, F2 and S1/S2 of the two Lorentzian components of UDP-induced currents were not changed by pinacidil (data not shown).

Figure 5A summarizes the kinetic parameters obtained from spectral analyses of the UTP-induced channel current fluctuations in the presence of various [pinacidil] (n = 3 for each point). Corner frequencies, relative powers at 0 Hz and S1/S2 ratios were plotted against [UTP] (Fig. 5Aa3 and b). The relative powers at 0 Hz of each Lorentzian component (rS1 and rS2) were obtained with reference to the S1 value recorded with 3 mM UTP in the presence of 300 μm pinacidil in each patch. Neither the corner frequencies nor the ratio of the powers of the two Lorentzian components was affected by [UTP], even in the presence of different [pinacidil]. On the other hand, the powers of both components were increased by UTP in a concentration-dependent fashion. Pinacidil (10-300 μm) increased the potency of UTP to increase the powers of both components in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 5Ab3).

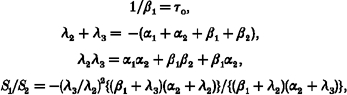

The power density spectra obtained from the current fluctuations induced by different [UTP] and [pinacidil] could be well fitted with the sum of two Lorentzian curves. This indicates that a minimum of three states are apparent in the fast gating of the channel (Colquhoun & Hawkes, 1977). Because analysis of single-channel openings clearly indicated that the channel has a single open state (Yamada et al. 1997), we assumed a simple three-state model to explain the channel kinetics, as follows:

| (4) |

where C1 and C2 are closed states, O is an open state, and α1, α2, β1 and β2 are rate constants.

As previously described (Hosoya et al. 1996), we calculated the rate constants α1, α2, β1 and β2 from parameters obtained from spectral analysis and the overall mean open time (Fig. 5Ac):

|

where λ2= -2πF1; λ3= -2πF2; and τo is the overall mean open time. τo was 1.5 ± 0.1 ms obtained from the single-channel analyses of five patches (data not shown). The estimated rate constants are depicted in Fig. 5Ac. We also calculated the rate constants of α1, α2, β1 and β2 with different [UDP] in the absence and presence of pinacidil (n = 3, Fig. 5B). Neither UDP nor UTP changed any of the rate constants even in the presence of various [pinacidil]. This suggests that the gating of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel, as represented by the two Lorentzian components, is independent of uracil nucleotides and also of pinacidil.

The powers of the two Lorentzian components of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel current were enhanced by increasing [UTP] or [UDP]. Because the single-channel current amplitude was not affected either by nucleotides or pinacidil (not shown), this observation may indicate the presence of a UTP- or UDP-dependent process which brings the channels from a very long closed state to the fast gating mode described by eqn (4). We could not, however, detect the corresponding component(s) in the power spectra. The process may be so slow that we can practically recognize it to be independent of the fast gating mechanism. Therefore, we assumed the existence of two independent reactions in the activation kinetics of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 complex channel; a fast gating process described above (eqn (4)) and a slow process regulating channel availability. Because the Hill coefficients for UTP and UDP induction of channel activity were ∼1.5 in the absence of pinacidil (Figs 2Cb and 3Bb), we have adopted the following kinetic model for the slow process:

| (5) |

where A is the functionally active (available) state and can open when the fast gate takes the O state, while U is the functionally inactive (unavailable) state and cannot open, even if the gate reaches the O state. α3, α4, β3 and β4 are rate constants influenced by UTP, UDP or pinacidil.

In this model, the open probability of the channel can be expressed as follows:

Because α1, α2, β1 and β2 were constant in all conditions, α1α2/(α1α2+β1β2+β1α2) was ∼0.8 and relative NPo could be expressed as the following equation:

Then, α3/β3 and α4/β4 were defined as the equilibrium constants K1 and K2, respectively. K1 and K2 were functions of [nucleotide] and [pinacidil]. The relative NPo of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel at different [UTP] or [UDP] in the presence of different [pinacidil] could be expressed as follows:

| (6) |

The relationships between [UTP] or [UDP] and channel activity in the presence of different [pinacidil] could be well fitted with eqn (6) (Fig. 6). The K1 and K2 values are summarized in Table 1. K1and K2values increased about 3.3 and 40 times per micromolar increase in [pinacidil] in the UTP-mediated gating and about 1.7 and 30 times per micromolar increase in [pinacidil] in the UDP-mediated gating. Thus, the effects of pinacidil on K1 and K2 were similar for both UTP- and UDP-mediated slow gating processes.

Figure 6. Activation of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels by UTP, UDP and pinacidil.

Data are reproduced from Fig. 2C b for UTP (A) and from Fig. 3B b for UDP (B). The dashed lines represent the fits of these data to eqn (6) which represents the increase in channel activity resulting from the recruitment of ion channels (see text for details).

Table 1.

Values of the dissociation constants K1 and K2 (mm−1) for UTP- and UDP-induced channel opening in the presence of various concentrations of pinacidil

| Concentration of pinacidil (μm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm−1 | 0 | 10 | 100 | 300 | |

| UTP | K1 | 0.3 | 10 | 100 | 300 |

| K2 | 0.05 | 20 | 200 | 600 | |

| UDP | K1 | 0.6 | 10 | — | 300 |

| K2 | 0.3 | 100 | — | 3000 | |

DISCUSSION

The major findings in this study are as follows: (1) the SUR2B/Kir6.1 complex channel does not open spontaneously in excised IO membrane patches and requires intracellular nucleoside di- or tri-, but not mono-, phosphates for its opening; (2) pinacidil, a KCO, enhances the opening of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel by increasing the potency of nucleoside di- and triphosphates to induce channel activation; (3) the activation gating kinetics of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel can be described by two practically independent mechanisms: a fast nucleotide-independent channel gate (C2 C1 O) and a slow nucleotide-dependent gate which affects the number of functionally active channels (U2 U1 A). Pinacidil specifically controls the latter mechanism.

Nucleotide regulation of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity

It has not yet been established whether vascular KNDP channels are actually composed of SUR2B and Kir6.1. It is therefore necessary to further clarify the molecular nature of KNDP channels in vascular smooth muscle cells using molecular biological and biochemical techniques, such as the analysis of mRNAs obtained from single smooth muscle cells. Nevertheless, because the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel exhibited properties in single-channel conductance and regulation by intracellular nucleotides very similar to those of the NDP-dependent K+ (KNDP) channel described in smooth muscle cells of rat portal vein (Zhang & Bolton, 1996), the understanding provided by the present study on SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel gating may be largely applicable to the native KNDP channel.

This study showed that the nucleotide-induced activity of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel can be described as the product of nucleotide-mediated activation and inhibition. A low level of channel activity could be recorded in 63 out of 203 cell-attached patches of transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 1B a). This may be because the physiological concentrations of intracellular nucleotides, i.e. in the millimolar range for ATP and a micromolar range in the hundreds for GTP, GDP and ADP, locate the channel at the crossing area between the activation and inhibition curves, as expected from the IO patch experiments of Figs 2 and 3. Therefore, channel activity can be enhanced immediately by shifting either the activation curve to the left or the inhibition curve to the right. Actually, pinacidil, a KCO, shifted the activation curve to the left in a concentration-dependent fashion and induced SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity very effectively (Figs 1, 2 and 3). Because the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel exhibited properties similar to the smooth muscle KNDP channel (Yamada et al. 1997), this result would explain why KCOs activate glibenclamide-sensitive K+ currents more effectively in vascular smooth muscle than in cardiac muscle (Quast, 1992).

This study also showed that UTP and UDP activate the channel much more effectively than ATP. This is likely to reflect the superimposed inhibition of channels by high concentrations of ATP, which was absent in the case of uracil nucleotides. When the activation of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel by adenine or guanine nucleotides in the absence of inhibition was estimated, their efficacy to induce channel activity, i.e. the saturating maximum channel activity, was shown to be the same as that induced by uracil nucleotides. From the analyses of Figs 2 and 3, the order of various nucleotides in their potency to induce SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity in the control could be estimated to be ATP = ADP = GTP = GDP ≥ UDP ≥ UTP. Because pinacidil selectively enhanced the potency of the nucleotides to induce channel activation but did not affect adenine or guanine nucleotide-mediated inhibition, the KCO apparently increased both the potency and efficacy of adenine or guanine nucleotides to stimulate channel activity.

Inhibition of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel by adenine and guanine nucleotides

High concentrations of adenine and guanine nucleotides inhibited the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel, and this inhibition exhibited completely different characteristics from the ATP-mediated inhibition of the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel. The inhibition of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels could be evoked not only by ATP but similar potency by ADP, GTP and GDP. Even in the presence of pinacidil, the inhibitory effects of these nucleotides remained the same. On the other hand, the spontaneous activity of SUR2B/Kir6.2 channels was inhibited quite specifically by ATP. GTP, GDP and ADP at 1 mM were not effective. Furthermore, the ATP-mediated inhibition of SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel was attenuated by pinacidil in a concentration-dependent fashion.

Spectral analysis further indicated the kinetic differences between ATP-mediated inhibition of SUR2B/Kir6.1 and that of SUR2B/Kir6.2 channels (not shown). The power spectra of the uracil nucleotide-induced SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel currents which did not show significant channel inhibition were composed of two Lorentzian components: for example, with 3 mM UTP the corner frequencies (F) of the two components were 1.26 ± 0.16 and 825 ± 17 Hz (n = 3) (see Fig. 4). On the other hand, the power spectra of the currents induced by high concentrations of ATP, which show both activation and inhibition, were composed of three components: in the SUR2B/Kir6.1 currents induced by 1 mM ATP, the corner frequencies (F) of the three components were 1.30 ± 0.17, 33.1 ± 9.3 and 852 ± 11 Hz (n = 3, not shown). The component with an F value of ∼30 Hz appeared in the presence of ATP, but not in the case of uracil nucleotides. Thus, it may be caused by ATP-mediated SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel inhibition. Consistently, when 1 mM ATP was added to the UDP-induced channel activity, the channel bursts became shorter and spiky and the component with an F value of ∼30 Hz appeared in the power spectrum (not shown). This may indicate that ATP incorporates a blocked state to the fast gating process of the UDP-induced channel opening. On the other hand, the power spectrum of SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel current fluctuation was also composed of two Lorentzian components (S1 is the slow, while S2 is the fast component). Upon formation of IO patches, maximum spontaneous channel opening appeared. As the channel activity was decreased by ATPi in a concentration-dependent manner, the power of S1 was first enhanced and then decreased, while the power of S2 was monotonically decreased. The ratio of powers was increased by ATPi, but the corner frequencies of the two components remained the same.

These results can be interpreted as indicating that inhibition of the SUR2B/Kir6.2 channel may be mainly achieved by decreasing the appearance and duration of channel bursts, as indicated in native cardiac KATP channels (Qin et al. 1989).

Therefore, in terms of nucleotide-mediated inhibition, two channels possessing the same SUR subunit (SUR2B) but distinct Kir subunits (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2) exhibited completely different properties in both their sensitivity to intracellular nucleotides and KCOs and also in their kinetics.

Analysis of the effects of nucleotides and pinacidil on activation gating of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel

Pinacidil specifically increased the potency of different nucleotides to activate the channel in a concentration-dependent fashion. Analysis of the activation gate of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel using UTP and UDP indicated that activation gating could be well analysed by assuming it was composed of two independent processes, a fast gate that is independent of nucleotides and a nucleotide-dependent slow gate that controls the number of functionally active channels. Pinacidil hardly affected the fast gating, but specifically affected the slow gate. Therefore, the slow gate is the key mechanism for control of SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity by intracellular nucleotides and KCOs.

The nucleotide-dependent slow gate controlling the number of functionally active channels could be described by the scheme U2 U1 A. For every micromolar increase in [pinacidil] the K1 value increased 2–3 times and the K2 value 30–40 times for both UTP and UDP, which indicated that the effect of pinacidil was the same upon UTP- and UDP-mediated slow gatings of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel. Thus it seems likely that UTP and UDP act on the same slow gate. Nucleotide-induced activation of the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel occurring in the absence of pinacidil disappeared quickly upon washout of nucleotides. In contrast, once activated by nucleotides and pinacidil, the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel activity remained high for between one and several minutes even after washout of exogenous nucleotides. Pinacidil, therefore, might have an effect in stabilizing the nucleotide-induced conformation change of the channel.

Evidence to date obtained in experiments using various SURs and Kir6.2 suggests that SUR confers regulation by nucleotides and pharmacological agents, such as sulphonylureas and KCOs, and the inward rectifier Kir6.2 subunit forms the ion-conducting pore. The regulatory mechanism of the Kir6.2 channel pore by SUR1 has been studied extensively by several groups (Nichols et al. 1996; Gribble et al. 1997; Shyng et al. 1997; Tucker et al. 1997). By using the mutagenesis technique, it was indicated that both the first nucleotide-binding fold (NBF1) and the second nucleotide-binding fold (NBF2) were involved in MgADP stimulation of the SUR1/Kir6.2 channel. Shyng et al. (1997) proposed a model for the gating of the SUR1/Kir6.2 KATP channel in which MgADP and diazoxide stimulated channel activity by stabilizing an open state resulting from the hydrolysis of nucleotides at NBF1 and NBF2. In the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channels, on the other hand, the potencies of various NTPs and NDPs in activating the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel were similar. It has also been shown that the channel is activated by non-hydrolysable ATP analogues (ATPγS and adenylyl imidophosphate (AMP-PNP)) with a similar potency to ATP (Yamada et al. 1997). Therefore, it seems likely that hydrolysis of nucleotides at the NBFs of SURs might not be essential for activation of the Kir6.1 channel by nucleotides and pinacidil.

Further studies on the nucleotide-mediated activation of SUR/Kir6.1 channels using mutated SURs and Kir6.1 subunits are, however, needed to elucidate the molecular mechanism of how nucleotides and pinacidil control the SUR2B/Kir6.1 channel. This study may be critical for understanding the physiological regulation of vascular smooth muscle tone by KNDP channels and to develop a new type of KCO specifically acting on these channels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Ian Findlay (Tours, France) and Lutz Pott (Bochum, Germany) for their critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Ms Kiyomi Okuto for her technical assistance and Ms Keiko Tsuji for her secretarial support. This work has been supported by grants to Y. K. from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, ‘Research for the Future’ Program of The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (96L00302) and the Human Frontier Science Program (RG0158/1997-B).

References

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Nichols CG, Wechsler SW, Clement JP, IV, Boyd AE, III, González G, Herrera-Sosa H, Nguy K, Bryan J, Nelson DA. Cloning of β cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1988;11:97–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.000525. 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Zhang H, Nakao K, Bolton TB. K channel activation by nucleotide diphosphates and its inhibition by glibenclamide in vascular smooth muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;110:573–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Hawkes A. Relaxation and fluctuations of membrane currents that flow through drug-operated channels. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1977;199:231–262. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1977.0137. B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson RMC, Elliott DC, Elliott WH, Jones KM. Data for Biochemical Research. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Weston AH. The pharmacology of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Annual Review of Pharmacological Toxicology. 1993;33:597–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.003121. 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. The essential role of the Walker A motifs of SUR1 in K-ATP channel activation by Mg-ADP and diazoxide. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1145. 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya Y, Yamada M, Ito H, Kurachi Y. A functional model for G protein activation of the muscarinic K+ channel in guinea pig atrial myocytes: Spectral analysis of the effect of GTP on single-channel kinetics. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;208:485–495. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.6.485. 10.1085/jgp.108.6.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulphonylurea receptor. Science. 1995a;270:1164–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Wang C-Z, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Seino S. A family of sulfonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80124-5. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Tsuura Y, Namba N, Masuda K, Gonoi T, Horie M, Seino Y, Mizuta M, Seino S. Cloning and functional characterization of a novel ATP sensitive potassium channel ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues, including pancreatic islets, pituitary, skeletal muscle, and heart. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995b;270:5691–5694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5691. 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomoto S, Kondo C, Yamada M, Matsumoto S, Higashiguchi O, Horio Y, Matsuzawa Y, Kurachi Y. A novel sulfonylurea receptor forms with BIR (Kir6.2) a smooth muscle type ATP-sensitive K+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:24321–24324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24321. 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajioka S, Kitamura K, Kuriyama H. Guanosine diphosphate activates an adenosine 5′-triphosphate-sensitive K+ channel in the rabbit portal vein. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;444:397–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Shyng S-L, Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Clement JP, IV, González G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Permutt MA, Bryan J. Adenosine diphosphate as an intracellular regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1996;272:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama Y, Yamada M, Kondo C, Satoh E, Isomoto S, Shindo S, Horio Y, Kitakaze M, Hori M, Kurachi Y. Properties of SUR2A/Kir6.2 ATP-sensitive K+ channels expressed in a mammalian cell line, HEK 293T cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1998;435:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s004240050559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quast U. Potassium channel openers: pharmacological and clinical aspects. Fundamental and Clinical Pharmacology. 1992;6:279–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1992.tb00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin D, Takano M, Noma A. Kinetics of ATP-sensitive K+ channel revealed with oil-gate concentration jump methods. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:H1624–1633. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura H, Ämmälä C, Smith PA, Gribble FM, Ashcroft FM. Cloning and functional expression of the cDNA encoding a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit expressed in pancreatic β-cells, brain, heart and skeletal muscle. FEBS Letters. 1995;377:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S-L, Ferrigni T, Nichols CG. Regulation of KATP channel activity by diazoxide and MgADP distinct functions of the two nucleotide binding folds of sulfonylurea-receptor. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:643–654. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel H. Isometric equilibria in complexes of adenosine 5′-triphosphate with divalent metal ions: Solution structures of M(ATP)2− complexes. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1987;165:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzic A, Jahangir A, Kurachi Y. Cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channels: regulation by intracellular nucleotides and K+ channel-opening drugs. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:C525–545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.3.C525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Isomoto S, Matsumoto S, Kondo C, Shindo T, Horio Y, Kurachi Y. Sulphonylurea receptor 2B and Kir6.1 form a sulphonylurea-sensitive but ATP-insensitive K+ channel. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:715–720. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]