Abstract

A model for retinal directional selectivity postulates that GABAergic inhibition of responses to motions in the null (anti-preferred) direction underlies this selectivity. An alternative model postulates that besides this inhibition, there exists an asymmetric, nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) input from starburst amacrine cells. It is possible for the latter but not the former model that stimuli could exist such that nicotinic blockade eliminates directional selectivity. Such stimuli would drive the cholinergic but not the GABAergic system well.

So far, attempts to eliminate directional selectivity with nicotinic blockade have failed, but they always used isolated, moving bars as the stimulus. We confirmed this failure for On-Off directionally selective (DS) ganglion cells in our preparation of the rabbit's retina.

However, while recording from these cells, we discovered that nicotinic blockade eliminated directional selectivity to drifting, low spatial frequency sine- and square-wave gratings.

This effect was not just due to the smallness of the responses under nicotinic blockade. NMDA blockade caused even smaller responses, but no loss of directional selectivity.

This result is consistent with a two-asymmetric-pathways model of directional selectivity, but inconsistent with an asymmetric-GABA-only model.

We conclude that asymmetric nicotinic inputs extend the range of stimuli that can elicit directional selectivity to include moving textures, that is, those with multiple peaks in their spatial luminance profile.

As originally described by Barlow & Levick (1965), directionally selective retinal ganglion cells produce robust responses for motions in one direction (the preferred direction), while responding weakly to motions in the opposite direction (the null direction). Despite over 30 years of investigation, the cellular mechanisms underlying this classic example of retinal neural computation remain unclear.

Recently, two models have appeared in the literature to explain the directionally selective responses of rabbit retinal On-Off directionally selective (DS) cells. One proposes a spatially asymmetric GABAergic input (from an unidentified amacrine cell) with symmetric nicotinic cholinergic (from starburst amacrine cells) and glutamatergic inputs (from bipolar cells probably mostly through NMDA receptors) to the DS cells (He & Masland, 1997). The other is identical except for proposing that the nicotinic input is asymmetric as well (Grzywacz et al. 1995; Grzywacz et al. 1997; Grzywacz et al. 1998b; F. R. Amthor, W. W. Belser & N. M. Grzywacz, unpublished observations). Of critical import to this two-asymmetric-pathways model is that the acetylcholine (ACh) release from starburst amacrine cells also depends on GABA (from a second unidentified amacrine cell) (Massey & Neal, 1979; Massey & Redburn, 1982). Without this GABAergic input, electrotonic modelling predicts that the nicotinic input to DS cells will be much less directionally selective (Borg-Graham & Grzywacz, 1991).

It has proven difficult to design an experiment that can distinguish between these two models. To illustrate this, consider first the asymmetric-GABA-only model. It predicts an excitatory nicotinic input to the DS cells for null-direction motions. However, demonstrating this proposed input is problematic because GABAergic null-direction inhibition masks it. For example, when null-side starburst amacrine cells are ablated (He & Masland, 1997), null-direction DS cell responses are not reduced, presumably because GABAergic null-direction inhibition holds them close to zero as in normal conditions. Consider in turn the starburst nicotinic input in the two-asymmetric-pathways model. Again, GABAergic null-direction inhibition prevents a simple demonstration of the spatial nicotinic input asymmetry. One cannot block GABA and then search for asymmetry in the nicotinic input (He & Masland, 1997), because the model-hypothesized ACh release asymmetry depends on GABA. And, of course, blocking the nicotinic input leaves the GABA asymmetry, so both models would predict a maintenance of directional selectivity.

One way to determine which model is more accurate would be to find a method for disabling the GABAergic null-direction inhibition without affecting the GABAergic control of ACh release. In this case, the asymmetric-GABA-only model but not the two-asymmetric-pathways model would predict a loss of directional selectivity.

It is known that the null-direction inhibition in On-Off DS cells is spatially large (Amthor & Grzywacz, 1993) and temporally slow. In two-flash apparent-motion experiments, the decay of null-direction inhibition may be larger than 1 s (Wyatt & Daw, 1975). Thus, null-direction inhibition should not be able to follow stimuli such as sine- or square-wave gratings, which drive it many times in rapid succession. If DS cells are only asymmetric in this GABAergic input, then they should cease to respond in a directionally selective manner when driven by relatively fast gratings (or other textured visual surfaces). Otherwise, the remaining directional selectivity is probably carried by the nicotinic and/or NMDA inputs (Kittila & Massey, 1997; Grzywacz et al. 1998b). These can be blocked pharmacologically to determine which is providing the directionally selective signal. If directional selectivity to the grating remained because the grating stimulus effectively drives the GABAergic null-direction inhibition, then blockade of either excitatory path should not eliminate directional selectivity. Thus, we have used drifting gratings along with nicotinic and NMDA blockades to test for the presence of a second asymmetry in the On-Off DS cell pathway. The results of this test appeared previously in abstract form (Grzywacz et al. 1998a).

METHODS

Electrophysiological recording

The preparation and recording methods have appeared elsewhere (Amthor et al. 1989; Grzywacz et al. 1997). In brief, following anaesthesia (achieved through a combination of urethane (2 g kg−1 delivered intramuscularly) and pentobarbital given via the marginal ear vein in 0.3 ml doses every 10 min until no reflexive movement resulted from a paw pinch) and dark adaptation, an adult Dutch belt-pigmented rabbit's eye was removed, hemisected and mounted in a recording chamber as previously described. Following enucleation, the animal was killed with an overdose of pentobarbital. The eyecup was superfused with a modified Ames solution, saturated with 95 % O2−5 % CO2 (Ames & Nesbett, 1981). Extracellular recordings from just below the eye's visual streak were obtained with carbon fibre in glass microelectrodes. Fifteen cells from nine retinas were recorded with a drifting bar stimulus and thirteen cells from nine retinas were recorded with drifting sine-wave gratings. Three of the sine-wave tested cells from two retinas were also tested with a square-wave grating.

Excitatory blockade

To block nicotinic ACh receptors, we added 60 μmd-tubocurarine (hereinafter referred to as curare) to the superfusion following collection of control data. The concentration for the saturative effect of curare in our set-up was previously determined as 13 ± 11 μm (Grzywacz et al. 1997). To block NMDA glutamate receptors, we used either 250 μm or 500 μmd-2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid (AP7) (for a discussion of AP7 concentration issues, see Grzywacz et al. 1998b).

Visual stimulus

For fifteen cells, a sweeping bar (250 μm in width) was moved along the preferred null axis (at 1000 μm s−1) past a 200 × 200 μm window centred on the cell's receptive field (as described in detail in Grzywacz et al. 1997). For thirteen cells, a 240 μm cycle−1 (∼1.6 deg cycle−1) sine-wave grating was presented through the centred window. To three of these thirteen cells, we also presented a 130 μm cycle−1 (∼0.9 deg cycle−1) sine-wave grating and presented a 240 μm cycle−1 square-wave grating. The gratings drifted at rates ranging from 0.25 to 32 Hz in either the preferred or null direction for 9 s (repeated over 5 trials), 13 s (3 trials), or 17 s (3 trials) each. (Optimal responses were between 0.5 and 1 Hz, corresponding to ∼0.8–1.6 deg s−1. These speeds were lower than the optimal speeds obtained from unmasked cells with drifting slits (∼10 deg s−1; Wyatt & Daw, 1975). However, the optimal speed for square-wave gratings (F. R. Amthor & N. M. Grzywacz, unpublished observations) is slightly lower than that for slits, and no other surround-masked data exist for comparison.) To avoid transient effects, spike counts were begun following the first second of grating stimulation, making sure that each count was over an integer number of cycles. The grating contrast was 99.2 %, with contrast defined as:

where Lmax and Lmin are maximal and minimal luminances, respectively. The mean luminance was 60 lx.

Statistical analysis

Following an earlier study (Sernagor & Grzywacz, 1995), we performed a χ2 test on the preferred (P) and null (N) spike counts of each cell at each temporal frequency with the null hypothesis being that their values were equal. The rationale for using this test (in that study and here) was to consider the population of spikes as if any given spike had a fixed probability of belonging to one of two categories defined by the direction of motion. As such, this population defined a binomial distribution. Under this assumption, we performed a χ2 test to verify whether our sample came from a homogeneous binomial distribution (Hays, 1981). A criterion of P < 0.01was selected for the test's significance. Because our data had only one degree of freedom, we used Yates's correction for continuity of the χ2 test (Yates, 1934). In addition to this test, the directional selectivity index (DSI) was calculated at each temporal frequency (Grzywacz & Koch, 1987; Smith et al. 1996). This index's definition is DSI = (P−N)/(P+N). It is close to 1 when P≫N, 0 when the directional selectivity disappears, and negative if N > P. A Student's one-sided t test was performed to determine whether the mean DSIs at each temporal frequency were significantly different from zero. The degrees of freedom for this test were 4, 9, 10, 7, 6 and 3 for 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 Hz, respectively, and a criterion of P < 0.01 was selected for significance. (Because our question was whether curare eliminates directional selectivity, we only used data at the temporal frequencies for which preferred responses were statistically significantly higher than null responses under control condition.)

RESULTS

Effects of nicotinic blockade on drifting bar responses

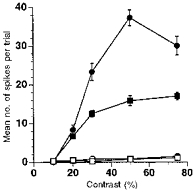

Figure 1 shows the mean responses of a rabbit On-Off DS cell to a drifting bar moving in either the preferred or null direction, during control and curare (a nicotinic ACh receptor blocker) conditions (with recovery not shown to avoid clutter). Results were similar for all fifteen DS cells tested. As in previous reports (Ariel & Daw, 1982b; Cohen & Miller, 1995; Grzywacz et al. 1997; Kittila & Massey, 1997), nicotinic blockade reduces preferred responses to bars, regardless of contrast, without eliminating directional selectivity.

Figure 1. Maintenance of directional selectivity under curare for responses to a drifting bar in an On-Off DS cell.

Mean preferred and null responses over twenty trials are shown for a range of contrasts in control and curare conditions. As previously demonstrated by several authors, preferred responses are reduced, but directional selectivity remains. •, control, preferred response; ^, control, null response; ▪, curare, preferred response; □, curare, null response. Error bars are s.e.m.

Effects of nicotinic blockade on drifting sine-wave grating responses

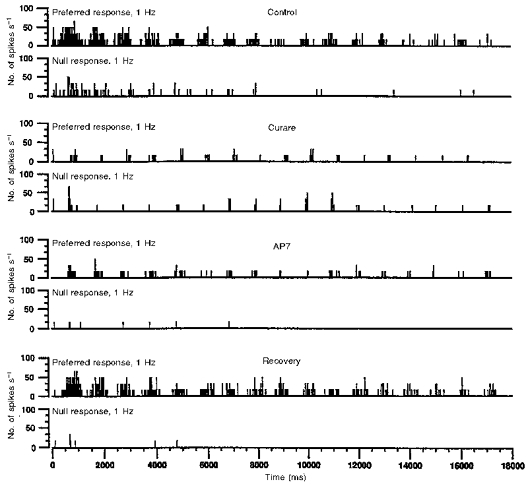

Figure 2 shows the responses of a rabbit On-Off DS cell to a sine-wave grating (240 μm cycle−1) drifting at 1 Hz in either the preferred or null direction during control, curare, AP7 (an NMDA glutamate receptor blocker) and recovery conditions. (Full recovery between the curare and AP7 applications was achieved, but is not shown so that the drug conditions can be more easily compared.) Nicotinic, but not NMDA, blockade eliminated the directional selectivity of this cell. Figure 3A and B illustrates the mean responses for two cells to the sine-wave grating for drift rates ranging from 0.25 to 32 Hz. For both cells, nicotinic blockade eliminated directional selectivity at nearly every temporal frequency tested. Similar results were obtained in twelve of thirteen cells stimulated with the sine-wave grating and tested with curare.

Figure 2. Loss of directional selectivity due to curare for 1 Hz grating motions in an On-Off DS cell.

Poststimulus histograms (20 ms bins) over 17 s (three trials) are shown for preferred (top row of each pair) and null-direction (bottom row of each pair) motions. The first, second, third and fourth pairs from the top correspond to control, curare, AP7 and recovery conditions, respectively. (Full recovery between the curare and AP7 applications was achieved, but is not shown so that the drug conditions can be more easily compared.) Despite causing a similar reduction to curare in preferred responses, AP7 does not eliminate directional selectivity. The adaptation-like effect, that is, the progressive reduction of responses with time, is commonly observed in the control, curare and AP7 conditions (despite being absent under curare in this cell at this temporal frequency), but is irrelevant to the loss of directional selectivity with curare.

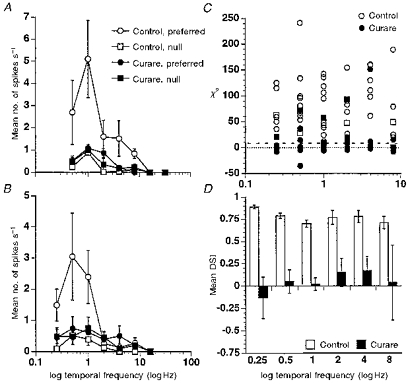

Figure 3. Loss of directional selectivity due to curare as a function of temporal frequency.

A and B, loss of directional selectivity for most temporal frequencies in two On-Off DS cells under curare. Mean responses to motions in the preferred direction (circles) and null direction (squares) are plotted versus temporal frequency. Control responses are shown as open symbols and curare responses as filled symbols; the figure does not show recovery responses to avoid clutter. Error bars are s.e.m. C, loss of statistically significant directional selectivity for most temporal frequencies between 0.25 and 8 Hz in eleven of twelve DS cells. The χ2 statistics are plotted versus temporal frequency with open symbols representing control data and filled symbols representing curare data. The χ2 values below the dashed line are not statistically significantly directionally selective at the P = 0.01 level. Data plotted as negative values represent reversals of preferred and null directions. One cell retained significant directional selectivity at four temporal frequencies and its data are shown as squares. D, insignificance of the directional selectivity index (DSI) under curare for eleven DS cells from C. Mean DSI values along with s.e.m. (excluding the outlier mentioned above) are plotted versus temporal frequency before (open bars) and during (filled bars) the application of curare.

Figure 3C plots χ2 indices of directional selectivity (see Methods) for each temporal frequency examined in twelve of the cells. (One cell was discarded as the nicotinic blockade abnormally increased its preferred and null responses at most temporal frequencies. However, the effect of blockade on directional selectivity in this cell was generally consistent with, albeit somewhat weaker than, the other cells.) Points below the dashed line indicate conditions for cells from which preferred responses were not statistically significantly larger than null responses. Negative values correspond to reversals of preferred and null directions. One cell did not appear to be dependent on nicotinic inputs for directional selectivity and this cell's data are shown as squares. With this exception, every cell was dependent on nicotinic inputs for producing directionally selective responses to the sine-wave grating at nearly every temporal frequency tested.

Although the χ2 statistic is good for detecting statistical losses of directional selectivity, it could be argued that some of the elimination of directional selectivity in Fig. 3C is due to smaller overall responses, reducing the sensitivity of this statistic. As Figs 2 and 3A and B illustrate, it is generally not the case that the cells were losing their directional selectivity because of the smaller responses. Moreover, as we discuss below, NMDA blockade also reduced overall responses, yet directional selectivity was not eliminated. And, when we plotted the more traditional directional selectivity index (Methods), we confirmed that the loss of directional selectivity is not simply due to weaker responses. Figure 3D shows the mean DSI at each temporal frequency for all cells except the outlier mentioned above. The mean DSI under curare is not significantly different from zero at any temporal frequency. (There is a suggestion that the DSI may be more affected at low temporal frequencies than high but this difference is not statistically significant - see Grzywacz et al. (1998b) for a discussion of the temporal frequency characteristics of the nicotinic input.)

Finally, we wished to eliminate the possibility that there was something unique about how DS cells respond to the 240 μm cycle−1 spatial frequency. To this purpose, for three of the thirteen cells above, we also used a drifting 130 μm cycle−1 sine-wave grating with qualitatively similar results.

Effects of nicotinic blockade on drifting square-wave grating responses

Were the differences between the effect of nicotinic blockade on the responses to bars and sine-wave gratings due to the sharp luminance gradients in the former? Or were these differences due to the grating driving null direction inhibition many times in rapid succession as discussed in the Introduction? For three of the thirteen cells, we repeated the experiments with a 240 μm cycle−1 square-wave grating. The results were qualitatively similar in terms of the DSI and χ2 statistics to those collected with the sine-wave gratings. Therefore, the differences between bars and sine-wave gratings were not due to the sharp luminance gradients in the former.

Effects of NMDA blockade on drifting sine-wave grating responses

Ten of the thirteen cells from above were also tested with the 240 μm cycle−1 sine-wave grating during the application of AP7. In Fig. 2, it can be seen that, despite an equivalent reduction in preferred responses as under curare, AP7 did not eliminate directional selectivity for this cell. Under NMDA blockade, five of the ten cells no longer gave significant preferred responses at more than one temporal frequency. For the remaining five, only one showed a loss of directional selectivity at any temporal frequency. Thus, as was previously demonstrated for drifting bar stimuli (Massey & Miller, 1990; Cohen & Miller, 1995; Kittila & Massey, 1997; Grzywacz et al. 1998b), NMDA inputs during drifting grating stimulation do not appear to be necessary for directional selectivity. This is not to say that they do not regulate the responses of directionally selective cells. For instance, Tjepkes & Amthor (1988) showed that reduction of the concentration of extracellular Mg2+ eliminates directional selectivity and that AP7 reverses this effect. The effect of low Mg2+ is probably due to the saturation of the NMDA pathway, as evidenced by the ‘corrective’ effect of AP7. Such an NMDA saturation is similar to that occurring in the cholinergic pathway when one applies physostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor (Grzywacz et al. 1997). In other words, the NMDA inputs appear to contribute to DS cell responsiveness but not to directional selectivity itself.

DISCUSSION

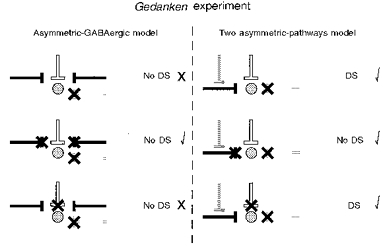

The role of ACh in On-Off DS cell responses has been enigmatic. Cholinergic starburst amacrine cells are appropriately positioned to communicate with DS cells (Famiglietti, 1992), and DS cells are excited by exogenous ACh (Ariel & Daw, 1982a). However, it has been difficult to determine whether the cholinergic input to these cells is spatially symmetric or asymmetric. GABAergic null-direction inhibition may mask putative cholinergic facilitation from null-side starburst cells (He & Masland, 1997), and GABAergic blockade may eliminate a crucial component in the control (Massey & Neal, 1979; Massey & Redburn, 1982) of putatively directionally selective starburst ACh release (Borg-Graham & Grzywacz, 1991). Thus, it can be shown that predictions for both the asymmetric-GABA-only and two-asymmetric-pathways models are identical for GABAergic blockade (He & Masland, 1997), nicotinic blockade (Ariel & Daw, 1982b; Kittila & Massey, 1997; Grzywacz et al. 1997) and starburst amacrine cell ablation experiments (He & Masland, 1997). Aiming to remedy this problem, we performed a Gedanken experiment that would give different predictions for the two models (Fig. 4). This experiment proposed a blockade of the GABAergic null-direction inhibition, while leaving the GABAergic control of the starburst amacrine cell ACh release unchanged. If this could be accomplished, then the asymmetric-GABA-only model would predict that directional selectivity would be lost, and that subsequent blockade of the excitatory nicotinic or NMDA inputs would simply reduce the now symmetric responses. The two-asymmetric-pathways model, on the other hand, would not predict a loss of directional selectivity in the Gedanken experiment, as the asymmetric nicotinic input could still support directional selectivity. If the nicotinic input were blocked in the Gedanken experiment, then the model would predict a loss of directional selectivity and a reduction of responses. In contrast, NMDA blockade would reduce responses, but leave directional selectivity.

Figure 4. Predictions of the Gedanken experiment for two models of directional selectivity.

The left column shows the proposed connectivity and predicted experimental results (directional selectivity, ‘DS’, or lack of it, ‘No DS’) for the asymmetric-GABA-only model. The right column does the same for the two-asymmetric-pathways model. For both models, the stippled disk represents the ganglion cell; and the white, black and grey lines represent the NMDA, ACh and GABA inputs, respectively. In the top row, predictions for blockade (indicated with a thick ×) of GABAergic null-direction inhibition, without disruption of GABAergic control of ACh release, are shown. The middle and bottom rows show predictions for the additional effects of nicotinic cholinergic and NMDA glutamatergic blockades, respectively. Check marks next to the predictions indicate consistency with the data. The predictions of the two-asymmetric-pathways model, but not those of the asymmetric-GABA-only model, match the data for all three experimental conditions.

We sought a method for realizing the Gedanken experiment, since it could provide strong constraints on the role of ACh for directional selectivity. For this purpose, the well-known slow decay time of the GABAergic null-direction inhibition (Wyatt & Daw, 1975) was useful. Because this decay is slow, it seemed reasonable that a stimulus that would drive the retina repetitively in rapid succession would not drive null-direction inhibition well or at all. Consequently, a drifting grating seemed like a good candidate stimulus for disabling the inhibition's ability to provide direction-of-motion information. From Wyatt & Daw's data (1975), the time constant for null-direction inhibition's decay seems to be about τ = 1 s. If inhibition decayed as a first-order linear process, then effectively it could not follow sine wave frequencies above 1/2πτ = 0.16 Hz (the 3 dB point of the process; Horowitz & Hill, 1989). But the critical frequency could be even lower, since null-direction inhibition is spatially wide (Amthor & Grzywacz, 1993) and each sine wave crest would fall on it for an extended period. Therefore, we expected null-direction inhibition to be ineffective at the frequencies tested. Of course, we did not know what the decay time is for the GABAergic inhibition controlling ACh release. However, if this decay were also slow, then it would beg the question of how a DS cell could be directionally selective for a grating stimulus in the first place. And, if the Gedanken experimental condition was not achieved because the grating stimulus still drives the GABAergic null-direction inhibition, then neither nicotinic nor NMDA blockades should eliminate directional selectivity.

As we report above, nicotinic, but not NMDA, blockade eliminates directionally selective responses in experiments using sine- or square-wave grating stimuli. This result is the outcome predicted by the two-asymmetric-pathways model for the Gedanken experiment, but not the outcome predicted by the asymmetric-GABA-only model. We thus conclude that the nicotinic inputs to On-Off DS cells are probably directionally selective. In addition, we postulate that the GABAergic input that controls ACh release from starburst amacrine cells must be separate from the GABAergic null-direction inhibition and must operate on a faster time scale. Finally, the data suggest that the role of the nicotinic input is to extend the range of stimuli for which DS cells can respond in a directional manner to include gratings in particular, and moving textures in general. Although the behavioural role of On-Off DS cells is unclear for the rabbit, the large sizes of their receptive fields and their multiple subunits suggest that these cells do not only deal with moving edges but with textures as well.

Acknowledgments

We thank William W. Belzer III for computer programming, Lorraine DeAngelis for technical assistance, and Darrel Tjepkes for help with the square-wave experiments. This work was supported by National Eye Institute grants EY08921 and EY11170 and the William A. Kettlewell Chair to N. M. G., by the National Eye Institute grant EY05070 to F. R. A., and by National Eye Institute Core grants to the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute and University of Alabama at Birmingham.

References

- Ames AA, III, Nesbett FB. In vitro retina as an experimental model of the central nervous system. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1981;37:867–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb04473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor FR, Grzywacz NM. Inhibition in directionally selective ganglion cells of the rabbit retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:2174–2187. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor FR, Takahashi ES, Oyster CW. Morphologies of rabbit retinal ganglion cells with concentric receptive fields. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;280:72–96. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariel M, Daw NW. Effects of cholinergic drugs on receptive field properties of rabbit retinal ganglion cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1982a;324:135–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariel M, Daw NW. Pharmacological analysis of directionally sensitive rabbit retinal ganglion cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1982b;324:161–185. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow HB, Levick WR. The mechanism of directionally selective units in rabbit's retina. The Journal of Physiology. 1965;178:477–505. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg-Graham LJ, Grzywacz NM. A model of the direction selectivity circuit in retina: Transformations by neurons singly and in concert. In: McKenna T, Davis J, Zornetzer SF, editors. Single Neuron Computation. Orlando: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 347–375. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ED, Miller RF. Quinoxalines block the mechanism of directional selectivity in ganglion cells of the rabbit retina. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:1127–1131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti EV. Dendritic co-stratification of ON and ON-OFF directionally selective ganglion cells with starburst amacrine cells in rabbit retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1992;324:322–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz NM, Amthor FR, Dacheux RF. Are cholinergic synapses to directionally selective ganglion cells spatially asymmetric? Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1995;(suppl. 36):865. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz NM, Amthor FR, Merwine DK. Necessity of acetylcholine for retinal directionally selective responses to drifting gratings. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1998a;(suppl. 39):432. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.575be.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz NM, Koch C. Functional properties of models for direction selectivity in the retina. Synapse. 1987;1:417–434. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz NM, Merwine DK, Amthor FR. Complementary roles of two excitatory pathways in retinal directional selectivity. Visual Neuroscience. 1998b doi: 10.1017/s0952523898156109. (in the Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz NM, Tootle JS, Amthor FR. Is the input to a GABAergic or cholinergic synapse the sole asymmetry in rabbit's retinal directional selectivity? Visual Neuroscience. 1997;14:39–54. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800008749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays WL. Statistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- He S-G, Masland RH. Retinal direction selectivity after targeted laser ablation of starburst amacrine cells. Nature. 1997;389:378–382. doi: 10.1038/38723. 10.1038/38723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz P, Hill W. The Art of Electronics. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kittila CA, Massey SC. Pharmacology of directionally selective ganglion cells in the rabbit retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:675–689. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SC, Miller RF. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors of ganglion cells in rabbit retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;63:16–29. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SC, Neal MJ. The light evoked release of acetylcholine from rabbit retina in vivo and its inhibition by gamma-aminobutyric acid. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1979;32:1327–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb11062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SC, Redburn DA. A tonic gamma-aminobutyric acid mediated inhibition of cholinergic amacrine cells in the rabbit retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1982;2:1643–1663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-11-01633.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sernagor E, Grzywacz NM. Emergence of complex receptive field properties of ganglion cells in the developing turtle retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:1355–1364. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Grzywacz NM, Borg-Graham LJ. Is the input to a GABAergic synapse the sole asymmetry in turtle's retinal directional selectivity? Visual Neuroscience. 1996;13:423–439. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800008105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjepkes DS, Amthor FR. The role of NMDA channel blockade by magnesium ions on the responses of ON-OFF directionally selective rabbit retinal ganglion cells. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1998;(suppl. 39):433. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt HJ, Daw NW. Directionally sensitive ganglion cells in the rabbit retina: Specificity for stimulus direction, size and speed. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1975;38:613–626. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.3.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates F. Contingency tables involving small numbers and the χ2 test. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1934;(suppl. 1):217–235. [Google Scholar]