Abstract

We investigated the effect of protein kinases and phosphatases on murine cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl− channels, expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, using iodide efflux and the excised inside-out configuration of the patch-clamp technique.

The protein kinase C (PKC) activator, phorbol dibutyrate, enhanced cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux. However, PKC did not augment the single-channel activity of either human or murine CFTR Cl− channels that had previously been activated by protein kinase A.

Fluoride, a non-specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases, stimulated both human and murine CFTR Cl− channels. However, calyculin A, a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A, did not enhance cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux.

The alkaline phosphatase inhibitor, (−)-bromotetramisole augmented cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux and, by itself, stimulated a larger efflux than that evoked by cAMP agonists. However, (+)-bromotetramisole, the inactive enantiomer, had the same effect. For murine CFTR, neither enantiomer enhanced single-channel activity. In contrast, both enantiomers increased the open probability (Po) of human CFTR, suggesting that bromotetramisole may promote the opening of human CFTR.

As murine CFTR had a low Po and was refractory to stimulation by activators of human CFTR, we investigated whether murine CFTR may open to a subconductance state. When single-channel records were filtered at 50 Hz, a very small subconductance state of murine CFTR was observed that had a Po greater than that of human CFTR. The occupancy of this subconductance state may explain the differences in channel regulation observed between human and murine CFTR.

The gating behaviour of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR; Riordan et al. 1989) Cl− channels is precisely regulated by the balance of protein kinase and phosphatase activity within cells and by the intracellular concentration of nucleoside triphosphates (for review see Gadsby & Nairn, 1994; Hanrahan et al. 1994; Welsh et al. 1995). The activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) causes the phosphorylation of multiple serine residues within the R domain (Cheng et al. 1991; Chang et al. 1993). Once the R domain is phosphorylated, channel gating is regulated by cycles of ATP hydrolysis at the nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs): ATP hydrolysis at NBD1 opens the channel, and ATP hydrolysis at NBD2 closes the channel (Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Li et al. 1996). Finally, protein phosphatases dephosphorylate the R domain and inactivate CFTR (Berger et al. 1993).

Although PKA is the most important kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of CFTR, the R domain also contains consensus phosphorylation sites for protein kinase C (PKC; Riordan et al. 1989). Initial studies indicated that PKC phosphorylates CFTR, but only weakly stimulates channel activity (Tabcharani et al. 1991; Picciotto et al. 1992; Berger et al. 1993). They also demonstrated that PKC greatly potentiates the onset and magnitude of channel activation when PKA is subsequently applied (Tabcharani et al. 1991). However, recent data suggest that PKC may play a more important role in channel activation than previously recognized. Studies by Jia et al. (1997) suggest that constitutive phosphorylation of CFTR by PKC is required for PKA-dependent phosphorylation to activate CFTR Cl− channels.

When cAMP agonists are removed, CFTR Cl− channels inactivate, even in the continued presence of cytosolic ATP (Tabcharani et al. 1991; Hwang et al. 1993; Reddy & Quinton, 1996; Travis et al. 1997). This inactivation is caused by dephosphorylation of the channel by protein phosphatases, because, first, it can be reversed by the readdition of cAMP agonists (Reddy & Quinton, 1996; Travis et al. 1997) and, second, it can be either prevented or slowed by protein phosphatase inhibitors (Tabcharani et al. 1991; Hwang et al. 1993; Becq et al. 1994). For example, in guinea-pig cardiac myocytes and human sweat duct epithelia, okadaic acid, a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A), greatly slowed the inactivation of CFTR Cl− currents after washout of cAMP agonists (Hwang et al. 1993; Reddy & Quinton, 1996). These results suggest that PP1 and/or PP2A dephosphorylates CFTR and closes the channel. Consistent with this idea, purified PP2A dephosphorylated CFTR and inactivated the channel in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts expressing human CFTR (Berger et al. 1993). However, recent data indicate that in airway and intestinal epithelia PP2C and not PP2A dephosphorylates CFTR and closes the channel (Travis et al. 1997). Other data demonstrate that phenylimidazothiazole drugs, which inhibit alkaline phosphatases, activate human CFTR Cl− channels heterologously expressed in airway epithelial cells (Becq et al. 1994). These results indicate that multiple protein phosphatases dephosphorylate CFTR and inactivate the channel. They also suggest that regulation of CFTR by protein phosphatases is cell-type specific.

Genes that encode CFTR have been identified in a number of species (Gadsby & Nairn, 1994; Hanrahan et al. 1994). Of those described in mammalian species, the sequence of murine CFTR is the most divergent from that of human CFTR (78 % sequence identity; 89 % sequence similarity). The R domain contains the greatest number of sequence alterations, but there is also significant variation between the NBD sequences of human and murine CFTR. Nevertheless, many of the sequences known to be important for the function of human CFTR are conserved in murine CFTR. These include the Walker motifs in the NBDs and the consensus phosphorylation sites in the R domain, with the exception of S753 which may play a role in the phosphorylation of CFTR (Gadsby & Nairn, 1994; Seibert et al. 1995). Consistent with this sequence conservation, human and murine CFTR both formed regulated Cl− channels with many properties in common (Lansdell et al. 1998).

In contrast to human CFTR, murine CFTR had a reduced open probability (Po), an altered pattern of channel gating, and pyrophosphate failed to prolong the duration of bursts of channel activity (Lansdell et al. 1998). The reduced Po of recombinant murine CFTR also differs from that of native rodent CFTR Cl− channels in epithelial cells isolated from rat pancreas and mouse gall bladder (Gray et al. 1988; French et al. 1996; Lansdell et al. 1998). This difference between recombinant and native murine CFTR Cl− channels may reflect variation in the regulation of murine CFTR by the protein kinases and phosphatases in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and native rodent tissues. To learn why recombinant murine CFTR had a reduced Po, the aim of this study was to examine the regulation of murine CFTR Cl− channels, expressed in CHO cells, by specific protein kinases and phosphatases. To address this aim, we adopted two experimental approaches: first, iodide efflux and second, the excised inside-out configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Using this dual approach, we could investigate the effect of CFTR modulators on both the activity of a large population of murine CFTR Cl− channels in intact cells, and the activity of individual channels in isolated membrane patches.

METHODS

Cells and cell culture

A full-length murine CFTR cDNA was assembled and stably expressed in CHO cells as previously described (Lansdell et al. 1998). CHO cells and mouse mammary epithelial (C127) cells expressing wild-type human CFTR were generous gifts of Drs S. H. Cheng, C. R. O'Riordan and A. E. Smith (Genzyme, Framingham, MA, USA). CHO cells were grown in Ham's F-12 nutrient medium, supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum, and 600 μg ml−1 neomycin (all from Life Technologies Ltd, Paisley, UK) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2. C127 cells were cultured as previously described (Sheppard & Robinson, 1997). For iodide efflux experiments, cells were seeded onto 60 mm plastic culture dishes and used 24–72 h later. For experiments using excised inside-out membrane patches, cells were seeded onto glass coverslips and used within 48 h.

Iodide efflux

Iodide efflux experiments were performed using a modification of the protocol of Chang et al. (1993). Cells (80–90 % confluent) were incubated for 1 h in a loading buffer containing (mm): 136 NaI, 3 KNO3, 2 Ca(NO3)2, 11 glucose, and 20 Hepes, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. To remove extracellular iodide, cells were thoroughly washed with efflux buffer (136 mm NaNO3 replacing 136 mm NaI in the loading buffer) and then equilibrated in 2.5 ml efflux buffer for 1 min. The efflux buffer was changed at 1 min intervals over the duration of the experiment which typically lasted 18 min. Four minutes after anion substitution, cells were exposed to agonists for 4 min. In some experiments, PKC modulators were added to the loading buffer 30 min prior to washing the cells with efflux buffer. The amount of iodide in each 2.5 ml sample of efflux buffer was determined using an iodide-selective electrode (HNU Systems Ltd, Warrington, UK). Cells were loaded and experiments performed at room temperature (∼23°C).

Electrophysiology

CFTR Cl− channels were recorded in excised inside-out membrane patches using an Axopatch 200A patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments Inc.) and pCLAMP data acquisition and analysis software (version 6.03, Axon Instruments Inc.) as previously described (Hamill et al. 1981; Sheppard & Robinson, 1997). The established sign convention was used throughout; currents produced by positive charge moving from intra- to extracellular solutions (anions moving in the opposite direction) are shown as positive currents.

The bath (intracellular) solution contained (mm): 140 N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG), 3 MgCl2, 1 CsEGTA, and 10 Tes, adjusted to pH 7.3 with HCl, ([Cl−], 147 mm; free [Ca2+], < 10−8m). The pipette (extracellular) solution contained (mm): 140 NMDG, 140 aspartic acid, 5 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4, and 10 Tes, adjusted to pH 7.3 with Tris ([Cl−], 10 mm). CFTR Cl−channels were activated by the addition of the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKA; 75 nm) and ATP (1 mm) to the intracellular solution within 5 min of excising membrane patches. To prevent channel rundown, PKA was maintained in the intracellular solution for the duration of the experiment. Membrane patches were clamped at −50 mV; the intracellular solution was maintained at 37°C using a temperature-controlled microscope stage (Brook Industries, Lake Villa, IL, USA).

In this study, we used membrane patches that contained five or less active channels for human CFTR and four or less active channels for murine CFTR. The number of channels in each membrane patch was determined from the maximum number of simultaneous channel openings observed during the course of an experiment, as previously described (Lansdell et al. 1998). An experiment typically lasted 30–90 min and included multiple interventions each of 4 min duration that significantly stimulate Po (e.g. ATP (1 mm) + PKA (75 nm)). To examine the effect of PKC, the intracellular surface of membrane patches was exposed to ATP (1 mm) and PKA (75 nm) within 5 min of excision. After a control period of 5 min, PKC (3 nm) and the lipid activator 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol (C8:0) (DiC8; 5 μm) were added to the intracellular solution and channel activity monitored for a further 10 min. To examine the effect of fluoride, interventions of 4 min duration were compared with the average of pre- and post-intervention control periods each of 4 min duration. The effect of bromotetramisole was examined by comparing interventions of 15 min duration with pre-intervention control periods of 5 min duration. During control periods the intracellular solution contained ATP (0.3 mm).

Single-channel currents were initially recorded on digital audiotape using a digital tape recorder (Biologic Scientific Instruments, model DTR-1204; Intracel Ltd, Royston, UK) at a bandwidth of 10 kHz. On playback, records were filtered with an eight-pole Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, model 902LPF2; SCENSYS Ltd, Aylesbury, UK) at a corner frequency of 500 Hz and acquired using a Digidata 1200 interface (Axon Instruments, Inc.) and pCLAMP at a sampling rate of 5 kHz. To determine whether murine CFTR opened to a subconductance state, records were additionally filtered at 50 Hz using a digital Gaussian filter. Unless otherwise stated, for the purpose of illustration, records were filtered at 500 Hz and digitized at 1 kHz.

Single-channel current amplitudes were determined either from the fit of Gaussian distributions to current amplitude histograms or by cursor measurements of individual well-resolved channel openings (Lansdell et al. 1998). Lists of open and closed times were created using a half-amplitude crossing criterion for event detection; transitions < 1 ms in duration were excluded from the analyses. Po was calculated using the equation:

| (1) |

where N is the number of channels; Ttot is the total time analysed, and T1 is the time that one or more channels are open, T2 is the time two or more channels are open and so on. Burst analysis was performed as described by Carson et al. (1995), using membrane patches that contained only a single active channel and a tc (the time that separates interburst closures from intraburst closures) of 15 ms. Closures longer than 15 ms were considered to define interburst closures, whereas closures shorter than this time were considered gaps within bursts. The mean interburst duration (Tc) was calculated using the equation:

| (2) |

where Tb = (mean burst duration) × (open probability within a burst). Mean burst duration and open probability within a burst were determined directly from experimental data; Po was calculated using eqn (1).

Protein kinase C and serine/threonine phosphatase assays

The activities of PKC and chelerythrine chloride were evaluated using the PepTag® assay for the non-radioactive detection of PKC (Promega Ltd, Southampton, UK). The activity of calyculin A was tested using PP2A and a serine/threonine phosphatase assay system (Promega Ltd). Both assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Reagents

PKC, the catalytic subunit of PKA, and the catalytic subunit of PP2A were obtained from Promega Ltd. ATP (disodium salt), (−)-bromotetramisole (active enantiomer), (+)-bromotetramisole (inactive enantiomer), 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate (CPT-cAMP), DiC8, forskolin, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate, and sodium fluoride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd (Poole, UK). Calyculin A and chelerythrine chloride were purchased from Semat Technical (UK) Ltd (St Albans, UK). All other chemicals were of reagent grade.

For bromotetramisole, calyculin A, and phorbol dibutyrate, the vehicle was DMSO and for chelerythrine chloride, it was methanol. DiC8 was dissolved in chloroform and stored under nitrogen. All stock solutions were stored at −20°C and diluted in intracellular solution immediately before use.

Statistics

Results are expressed as means ± s.e.m. of n observations. To compare sets of data, we used Student's t test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. Tests were performed using SigmaStat (version 1.03, Jandel Scientific GmbH, Erkrath, Germany).

RESULTS

To investigate the regulation of wild-type murine CFTR expressed in CHO cells, we used two strategies. First, we studied the effect of membrane-permeant CFTR modulators on iodide efflux from CHO cells. Using this technique, we could evaluate the effect of these agents on a large number of channels in intact cells. Second, we examined the effect of CFTR modulators on the activity of single murine CFTR Cl− channels in excised inside-out membrane patches. Using this technique, we could evaluate the effect of these agents on the number of active channels (N), single-channel current amplitude (i), and Po. For comparison, we used either untransfected CHO cells or CHO cells expressing wild-type human CFTR in the iodide efflux experiments and C127 cells expressing human CFTR in experiments using excised inside-out membrane patches. We have previously shown that the properties and regulation of wild-type human CFTR Cl− channels do not differ between these two cell types (Lansdell et al. 1998).

Effect of PKC modulators on murine CFTR

Recent studies of human CFTR suggest that the phosphorylation of CFTR by PKC is necessary for the acute activation of CFTR Cl− channels by PKA (Jia et al. 1997). To examine the effect of PKC phosphorylation on murine CFTR expressed in CHO cells, we studied the effect of PKC modulators on cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux (Fig. 1). Under control conditions, cAMP agonists stimulated an efflux of iodide with a peak response of 15.8 ± 0.4 nmol min−1 (n = 5) occurring 2–3 min after agonist addition. An efflux of similar magnitude (17.9 ± 2.6 nmol min−1; n = 5) and time course was observed when CHO cells expressing human CFTR were stimulated by cAMP agonists. However, cAMP agonists were without effect on untransfected cells (n = 5; Fig. 1). In cells pretreated with the PKC activator, phorbol dibutyrate (100 nm), two effects were observed (Fig. 1). First, phorbol dibutyrate, by itself, stimulated a transient increase in iodide efflux immediately following anion substitution. Second, phorbol dibutyrate significantly enhanced the cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux (P < 0.05; n = 5). Pretreatment of cells with the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine chloride (1 μm) was without effect on the magnitude of the cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux (P > 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 1). Similar results were observed using cells expressing human CFTR (n = 5; data not shown).

Figure 1. Phorbol dibutyrate pretreatment stimulates iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing wild-type murine CFTR.

Data show the time course of iodide efflux from CHO cells. Cells loaded with iodide were pretreated with either phorbol dibutyrate (100 nm; □) or chelerythrine chloride (1 μm; ▵) for 30 min prior to the start of the experiment. Control cells (CHO cells expressing murine CFTR, ^; untransfected CHO cells, •) were loaded with iodide, but untreated. Nitrate was substituted for iodide in the bathing medium at t =−3 min and iodide efflux was monitored at 1 min intervals for the duration of the experiment. The bar indicates the presence of cAMP agonists (10 μm forskolin, 100 μm IBMX and 500 μm CPT-cAMP). Symbols and error bars are means ± s.e.m. of n = 5 values at each time point. Where error bars are not evident the symbol has obscured them.

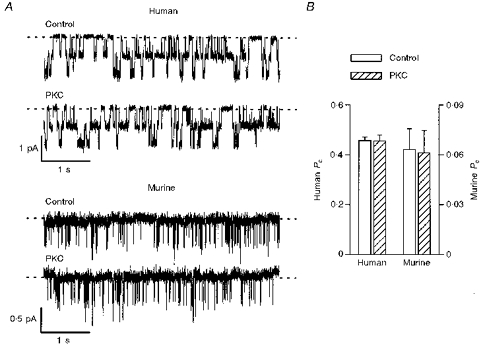

To investigate further the role of PKC phosphorylation, we studied single channels in excised inside-out membrane patches. Figure 2A shows representative single-channel traces of human and murine CFTR Cl− channels under control conditions and following the addition of PKC (3 nm) and DiC8 (5 μm) to the intracellular solution; ATP (1 mm) and PKA (75 nm) were present throughout. PKC and DiC8 were without effect on the Po of both human and murine CFTR Cl− channels (P > 0.05; Fig. 2B) and did not alter either N or i (see Fig. 2 legend). As the Po of human CFTR that we observed under control conditions (Po = 0.46 ± 0.02) was higher than that reported by Jia et al. (1997) under similar conditions (Po ≈ 0.25), we speculated that in our experiments human CFTR may have already been phosphorylated by PKC. To inhibit phosphorylation by PKC, C127 cells were pretreated for 30 min with chelerythrine chloride (1 μm) prior to the start of experiments. When cells were pretreated with chelerythrine chloride, we observed two effects. First, the number of membrane patches in which PKA activated human CFTR Cl− channels was decreased (control, 5/5 patches; chelerythrine chloride, 5/10 patches). Second, PKC and DiC8 stimulated a small increase in the Po of human CFTR (control, Po = 0.45 ± 0.03; PKC and DiC8, Po= 0.49 ± 0.03; P < 0.05; n = 5).

Figure 2. PKC fails to increase the activity of human and murine CFTR Cl− channels.

A, effect of PKC (3 nm) and DiC8 (5 μm) on the activity of two human and two murine CFTR Cl− channels. ATP (1 mm) and PKA (75 nm) were continuously present in the intracellular solution. Voltage was −50 mV, and there was a large Cl− concentration gradient across the membrane patch (external [Cl−], 10 mm; internal [Cl−], 147 mm). Dashed lines indicate the closed channel state and downwards deflections correspond to channel openings. Each trace is 5 s long. B, effect of PKC (3 nm) and DiC8 (5 μm) on the Po of human (left ordinate) and murine (right ordinate) CFTR Cl− channels. Note the change in scale. Columns and error bars indicate means + s.e.m. of n = 6 and n = 5 values for human and murine CFTR, respectively. Other details as in A. For murine CFTR, PKC and DiC8 were without effect upon either N or i (control: n = 2.4± 0.3, i = 0.45± 0.01 pA; PKC and DiC8: n = 2.2± 0.4, i = 0.44± 0.01 pA; n = 5). Similar results were observed with human CFTR (n = 6).

As our results suggested that PKC and chelerythrine chloride had little effect on the activity of both human and murine CFTR, we tested the activities of PKC and chelerythrine chloride using the PepTag® assay. This assay utilizes a brightly coloured fluorescent peptide that is highly specific for PKC. Phosphorylation of the peptide (amino acid sequence PLSRTLSVAAK) by PKC alters the peptide's net charge from +1 to −1, allowing separation of the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms on an agarose gel at neutral pH. The amount of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated peptide was quantified by spectrophotometry. After a 30 min incubation at 30°C, 65 ± 13 % of the peptide was phosphorylated by PKC (0.12 nm; n = 4). Inclusion of chelerythrine chloride (1 μm) in the reaction mixture reduced the PKC-dependent phosphorylation of the substrate to 43 ± 8 % (n = 4).

Regulation of murine CFTR by phosphatase inhibitors

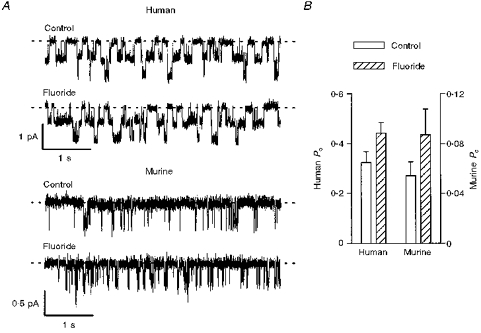

The activity of human CFTR is precisely regulated by the balance of protein kinase and phosphatase activity within cells (Gadsby & Nairn, 1994; Hanrahan et al. 1994; Welsh et al. 1995). To begin to examine the regulation of murine CFTR by protein phosphatases, we used sodium fluoride, a non-specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases. Figure 3A shows representative single-channel traces of human and murine CFTR Cl− channels under control conditions and in the presence of fluoride (10 mm); ATP (0.3 mm) and PKA (75 nm) were present throughout. Fluoride significantly stimulated the Po of both human and murine CFTR (P < 0.05; Fig. 3B). For human CFTR, fluoride increased the mean burst duration, but had little or no effect on the mean interburst duration (see Fig. 3 legend). However, inspection of single-channel records suggested that fluoride did not alter the burst duration of murine CFTR (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Fluoride stimulates human and murine CFTR Cl− channels.

A, effect of fluoride (10 mm) on two human and two murine CFTR Cl− channels. ATP (0.3 mm) and PKA (75 nm) were continuously present in the intracellular solution; voltage was −50 mV. Each trace is 5 s long. B, effect of fluoride (10 mm) on the Po of human (left ordinate) and murine (right ordinate) CFTR Cl− channels. Note the change in scale. Columns and error bars indicate means + s.e.m. of n = 4 and n = 5 values for human and murine CFTR, respectively. Fluoride (10 mm) increased the Po of human and murine CFTR Cl− channels to 141 ± 17 and 156 ± 12 % of the control values, respectively (n = 4–5; P < 0.05). Other details as in A. In two membrane patches that contained only a single human CFTR Cl− channel, fluoride (10 mm) increased the mean burst duration, but was without effect on the mean interburst duration (control: burst = 124.7 ± 11.1 ms, interburst = 190.2 ± 22.5 ms; fluoride: burst = 165.2 ± 11.1 ms, interburst = 172.1 ± 35.5 ms).

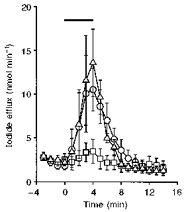

To identify the protein phosphatases that regulate murine CFTR, we used agents that inhibit specific classes of protein phosphatases. Calyculin A (100 nm), a potent inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A, by itself, stimulated a small efflux of iodide from CHO cells expressing murine CFTR (Fig. 4). However, it did not enhance the magnitude of the efflux stimulated by the cAMP agonist forskolin (10 μm; P > 0.05; Fig. 4). Similar results were observed using CHO cells that express human CFTR (n = 3; data not shown). We did not test the effect of calyculin A on CFTR Cl− channels in excised membrane patches, because PP2A is found in the cytoplasm of cells.

Figure 4. Effect of calyculin A on iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing wild-type murine CFTR.

Data show the time course of iodide efflux from CHO cells. Nitrate was substituted for iodide in the bathing medium at t =−3 min and iodide efflux was monitored at 1 min intervals for the duration of the experiment. The bar indicates the presence of the test drugs (forskolin (10 μm), ^; calyculin A (100 nm), □; forskolin (10 μm) and calyculin A (100 nm), ▵). Symbols and error bars are means ± s.e.m. of n = 5 values at each time point.

As calyculin A had little effect on iodide efflux, we used PP2A and a serine/threonine phosphatase assay to evaluate the activity of calyculin A. This assay determines the amount of free phosphate produced in a reaction mixture by measuring the absorbance of a molybdate:malachite green:phosphate complex. When PP2A (1 U) was reacted with a synthetic phosphopeptide (amino acid sequence RRA(pT)VA, where (pT) indicates phosphothreonine) at 30°C, 24.8 ± 0.4 pmol phosphate min−1 was generated (n = 3). Calyculin A (100 nm) reduced the amount of free phosphate produced to 0.63 ± 0.25 pmol phosphate min−1 (n = 3), a value similar to the basal level of free phosphate in the reaction mixture (0.52 ± 0.22 pmol phosphate min−1, n = 3).

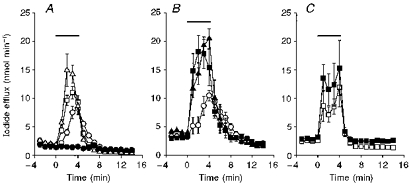

Previous studies using CHO cells expressing human CFTR demonstrated that in the absence of cAMP agonists the alkaline phosphatase inhibitor, (−)-bromotetramisole, activates CFTR Cl− channels in cell-attached membrane patches (Becq et al. 1994). Based on this result, we speculated that (−)-bromotetramisole might stimulate murine CFTR Cl− channels expressed in CHO cells. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of (−)-bromotetramisole (1 mm) on iodide efflux. Figure 5A shows that (−)-bromotetramisole had two effects: first, (−)-bromotetramisole significantly enhanced the forskolin-stimulated iodide efflux (P < 0.01; n = 5). Second, (−)-bromotetramisole, by itself, stimulated a larger efflux of iodide than that generated by forskolin (10 μm; P < 0.01; n = 5). The vehicle, DMSO (0.25 %), was without effect. As a control, we tested the effect of (+)-bromotetramisole on iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing murine CFTR (Fig. 5B); this enantiomer is without effect on alkaline phosphatases (Becq et al. 1996). Interestingly, (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm) had similar effects on iodide efflux to those observed with (−)-bromotetramisole (n = 5; Fig. 5A and B). Similar effects of (−)- and (+)-bromotetramisole were observed using CHO cells expressing human CFTR (n = 4 for both enantiomers; data not shown). As a further control, we tested the effects of (−)- and (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm) on iodide efflux from untransfected CHO cells (Fig. 5C). Both enantiomers stimulated iodide efflux, but cAMP agonists were without effect (Fig. 1).

Figure 5. Effect of bromotetramisole on iodide efflux from CHO cells.

Data show the time course of iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing wild-type murine CFTR treated with (−)-bromotetramisole (A), (+)-bromotetramisole (B), or untransfected CHO cells treated with both enantiomers (C). Nitrate was substituted for iodide in the bathing medium at t =−3 min and iodide efflux was monitored at 1 min intervals, for the duration of the experiment. The bar indicates the presence of the test drugs (forskolin (10 μm), ^; (−)-bromotetramisole (1 mm), □; forskolin (10 μm) and (−)-bromotetramisole (1 mm), ▵; (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm), ▪; forskolin (10 μm) and (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm), ▴; DMSO (0.25 %), •). Symbols and error bars are means ± s.e.m. of n = 5 values at each time point.

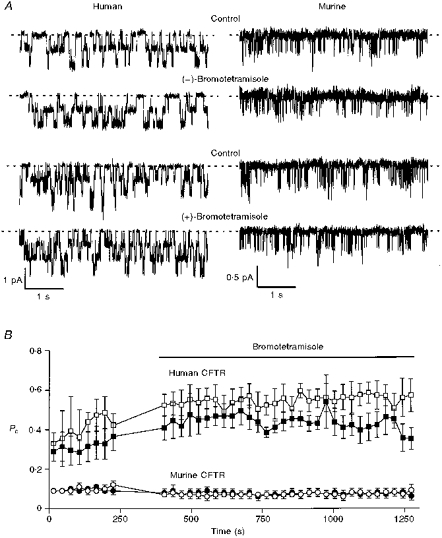

To understand further the effect of bromotetramisole, we studied human and murine CFTR Cl− channels using excised membrane patches. Figure 6A shows representative single-channel traces before and after the addition of either (−)- or (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm) and Fig. 6B shows a time course of the effect of these agents on Po. Both the (−) and (+) enantiomers of bromotetramisole stimulated the Po of human CFTR, but were without effect on both N and i (Fig. 6 and Table 1). In contrast, neither enantiomer of bromotetramisole stimulated the activity of murine CFTR (Fig. 6 and Table 1). In a small number of membrane patches which contained a single human CFTR Cl− channel, the effect of bromotetramisole on channel gating was examined. Both enantiomers of bromotetramsiole decreased the mean interburst duration, but had little or no effect on the mean burst duration (Table 1). These results suggest that bromotetramisole may promote the rate of channel opening of human CFTR.

Figure 6. Bromotetramisole stimulates human CFTR Cl− channels, but not those of murine CFTR.

A, effect of either (−)-bromotetramisole (1 mm) or (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm) on the activity of two and three human CFTR Cl− channels, respectively, and two murine CFTR Cl− channels. ATP (0.3 mm) and PKA (75 nm) were continuously present in the intracellular solution; voltage was −50 mV. Each trace is 5 s long. B, data show the time course of the Po of human CFTR (squares) and murine CFTR (circles). The bar indicates the presence of either (−)- or (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm; open and filled symbols, respectively). Each point is the average Po for a 30 s period and no data were collected during solution perfusion. (−)-Bromotetramisole significantly increased the Po of human CFTR to 135 ± 7 % of control (n = 4; P < 0.01), but decreased the Po of murine CFTR to 69 ± 10 % of control (n = 4; P < 0.05). (+)-Bromotetramisole significantly increased the Po of human CFTR to 157 ± 19 % of control (n = 4; P < 0.05), but decreased the Po of murine CFTR to 78 ± 11 % of control (n = 4; P < 0.05). Other details as in A. The vehicle, DMSO (0.25 %), did not alter the Po of human CFTR (control, Po= 0.36 ± 0.05; DMSO, Po= 0.35 ± 0.04; n = 4; P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Effect of bromotetramisole on human and murine CFTR Cl− channels

| N | i(pA) | Po | Mean burst duration (ms) | Mean interbust duration (ms) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Control | 1.40 ± 0.24 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 152 ± 22 | 206 ± 19 |

| (−)-Brt | 1.40 ± 0.24 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 172 ± 23 | 133 ± 12 | |

| Control | 3.00 ± 0.89 | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 166 ± 30 | 286 ± 65 | |

| (+)-Brt | 3.00 ± 0.89 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 164 ± 43 | 166 ± 33 | |

| Murine | Control | 3.25 ± 0.25 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | n.d. | n.d. |

| (−)-Brt | 3.25 ± 0.25 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Control | 3.00 ± 0.71 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | n.d. | n.d. | |

| (+)-Brt | 3.00 ± 0.71 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | n.d. | n.d. |

N, i and Po were measured under control conditions, and in the presence of either (−) or (+)-bromotetramisole (1 mm; Brt) for human and murine CFTR Cl− channels in excised inside-out membrane patches. ATP (0.3 mm) and PKA (75 nm) were continuously present in the intracellular solution; voltage was −50 mV. The data are means ±s.e.m.(n = 4–5) for human and murine CFTR. In five membrane patches which contained a single human CFTR Cl− channel, the effect of bromotetramisole on mean burst and interburst durations was determined, as described in the Methods (n = 3, (−)-bromotetramisole; n = 2, (+)-bromotetramisole). Both enantiomers of bromotetramisole significantly increased the Po of human CFTR (P < 0.05). n.d., not determined.

Murine CFTR frequently opens to a subconductance state

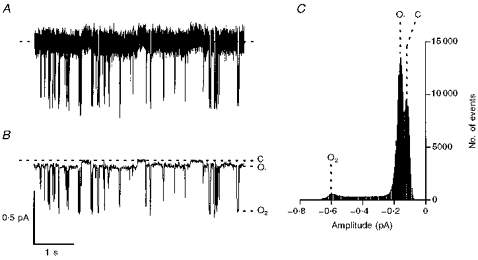

Our previous results (Lansdell et al. 1998) and those presented above demonstrate that murine CFTR Cl− channels in excised membrane patches have a low Po and are refractory to stimulation by modulators that activate human CFTR Cl− channels. In contrast, in intact cells, phorbol dibutyrate and bromotetramisole stimulated iodide efflux, suggesting that murine CFTR is activated by these agents. One possible explanation for these differences observed between intact cells and isolated membrane patches is that murine CFTR Cl− channels may open to a subconductance state that is not readily apparent with the analysis conditions that we routinely use. To test this idea, we filtered single-channel records at 50 Hz using a digital Gaussian filter. Figure 7 demonstrates that after filtering records at 50 Hz, a subconductance state was clearly observed. Following the nomenclature of Gunderson & Kopito (1995), we have termed the three conductance states of murine CFTR as follows: C (closed), O1 (subconductance state), and O2 (full open state). At −50 mV, the single-channel current amplitudes of O1 and O2 were 0.048 ± 0.001 and 0.46 ± 0.02 pA (n = 5), respectively. Using these values, the chord conductances of O1 and O2 at −50 mV were 0.44 ± 0.01 and 4.16 ± 0.14 pS (n = 5), respectively. These values are significantly different (P < 0.001).

Figure 7. Filtering single-channel records at 50 Hz reveals a subconductance state of murine CFTR.

The records show a single murine CFTR Cl− channel before (A) and after (B) filtering the data at 50 Hz using a digital Gaussian filter. Prior to filtering at 50 Hz, the record was filtered at 500 Hz and digitized at 5 kHz, as described in the Methods. In B, the closed channel state (C), the subconductance state (O1), and the full open state (O2) are indicated by dashed lines. ATP (0.3 mm) and PKA (75 nm) were continuously present in the intracellular solution; voltage was −50 mV. Each trace is 5 s long. C, current amplitude histogram for the single channel shown in B. The closed channel amplitude is the peak shown on the right. A linear x-axis with 20 bins decade−1 was used; total time analysed = 1 min. Other details as in B.

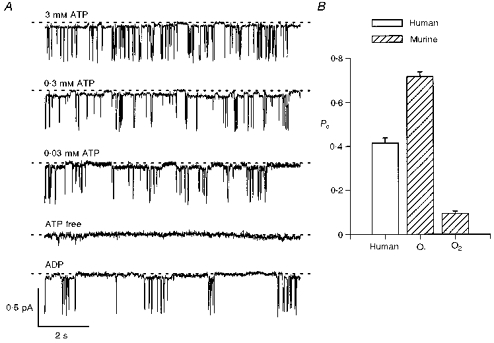

Although O1 was difficult to study due to its small single-channel current amplitude, several lines of evidence suggested that it was a subconductance state of murine CFTR rather than a contaminating channel. First, O1 was not observed in untransfected CHO cells (n = 10). Second, in membrane patches which contained one full conductance state (O2), we observed only one subconductance state (O1; Figs 7 and 8). Furthermore, in membrane patches which contained two full conductance states (O2), we observed two subconductance states (O1), each of similar amplitude. Third, transitions to O2 occurred from O1, but not from C (Figs 7 and 8). Fourth, like human CFTR Cl− channels (Winter et al. 1994), the opening of O1 was ATP dependent, and inhibited by ADP (Fig. 8A). These results suggest that O1 is a subconductance state of murine CFTR, and not a contaminating channel. Interestingly, the Po of O1 was elevated compared to that of both human CFTR and O2 (P < 0.001; n = 5–6; Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Regulation of the subconductance state of murine CFTR.

A, comparison of the effect of different ATP concentrations and of the effect of ADP (0.3 mm) in the presence of ATP (0.3 mm) on the activity of a single murine CFTR Cl− channel. With the exception of the ATP-free record, PKA (75 nm) was present throughout; voltage was −50 mV. Records were filtered at 50 Hz and digitized at 500 Hz. Each trace is 10 s long. Similar results were observed in five other membrane patches. B, Po of human CFTR, the subconductance state (O1) and the full open state (O2) of murine CFTR determined in the presence of ATP (1 mm) and PKA (75 nm). Columns and error bars are means + s.e.m. of n = 5 for O1 and n = 6 for human CFTR and O2. To calculate the Po of O1, transitions < 10 ms in duration were excluded from lists of open and closed times. Data for human CFTR and O2 are from Fig. 2C of Lansdell et al. (1998).

DISCUSSION

To understand why murine CFTR expressed in CHO cells had a low Po, we investigated channel regulation by protein kinases and phosphatases. Neither PKC nor protein phosphatase inhibitors increased the Po of murine CFTR to a level comparable to that of human CFTR. Based on these results and our previous work (Lansdell et al. 1998), we tested for, and observed, a subconductance state of murine CFTR when single-channel records were filtered at 50 Hz. The activity of this subconductance state (O1) was much increased compared with both human CFTR and the full open state of murine CFTR (O2).

The PKC activator, phorbol dibutyrate, enhanced cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing murine CFTR. Similarly, Winpenny et al. (1995) observed that phorbol dibutyrate augmented the magnitude of CFTR Cl− currents in rat pancreatic duct cells. However, PKC did not increase the Po of either human or murine CFTR Cl− channels that had previously been phosphorylated by PKA. PKC also did not enhance PKA-stimulated Cl− currents in excised membrane patches from NIH 3T3 fibroblasts expressing human CFTR (Berger et al. 1993). In contrast, PKC greatly potentiated the onset and magnitude of channel activation when PKA was subsequently applied to excised membrane patches from CHO cells expressing human CFTR (Tabcharani et al. 1991). A possible explanation for these different effects of PKC on CFTR Cl− channels has been proposed by Jia et al. (1997). These authors suggest that differences in basal PKC activity may contribute to the variation in CFTR Cl− channel activity observed in different cell types. Consistent with this idea, pretreatment of C127 cells with chelerythrine chloride increased the number of membrane patches where PKA failed to activate human CFTR Cl− channels. In addition, using these cells PKC stimulated the Po of human CFTR. However, after a 30 min incubation period chelerythrine chloride only partially inhibited PKC phosphorylation of the peptide substrate in the PepTag® assay. It is conceivable that a shorter incubation period may have revealed a stronger inhibition. In addition, chelerythrine chloride sensitivity may vary between C127 and CHO cells depending upon the particular PKC isozymes expressed in each cell type. These possibilities may explain why chelerythrine chloride was without effect on cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux from CHO cells. Interestingly, when recombinant human CFTR, expressed in Sf9 insect cells, was purified and reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers, only PKA was required to activate channels and the Po was 0.38 ± 0.13 (Bear et al. 1992), a value similar to that which we observed using either C127 or CHO cells expressing human CFTR (Lansdell et al. 1998). Thus, the data suggest that it is probably difficult to dephosphorylate CFTR at sites phosphorylated by PKC.

Fluoride stimulates the activity of CFTR Cl− channels in excised inside-out membrane patches (Tabcharani et al. 1991; Berger et al. 1998; this study). Initially this stimulation was interpreted as resulting from the inhibition of membrane-associated phosphatases by fluoride (Tabcharani et al. 1991). However, recent data suggest that the effect of fluoride may be independent of phosphatase inhibition, because fluoride stimulated the human CFTR mutant CFTRΔR-S660A (Berger et al. 1998). This mutant lacks the major phosphorylation sites responsible for the activation of human CFTR by PKA; these sites are conserved in murine CFTR (Gadsby & Nairn, 1994). Instead, fluoride may directly interact with CFTR to prolong the duration of bursts of activity (Berger et al. 1998; this study). This action of fluoride is reminiscent of the effect of inorganic phosphate analogues that lock CFTR Cl− channels open by disrupting cycles of ATP hydrolysis at the NBDs (Baukrowitz et al. 1994). Although fluoride stimulated the activity of both human and murine CFTR Cl− channels, it did not appear to prolong the burst duration of murine CFTR. Consistent with this result, our previous data showed that 5′-adenylylimidodiphosphate and pyrophosphate, two agents that prolong the burst duration of human CFTR, failed to stabilize the open state of murine CFTR (Lansdell et al. 1998).

Calyculin A did not enhance cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing either human or murine CFTR. One possible explanation for this result is that forskolin (10 μm) maximally stimulated iodide efflux. This explanation is unlikely, however, because a cocktail of cAMP agonists (10 μm forskolin, 100 μm IBMX and 500 μm CPT-cAMP) stimulated an iodide efflux that was approximately 50 % larger than that stimulated by forskolin (10 μm; Figs 1, 4 and 5). Consistent with our results, calyculin A and okadaic acid failed to prevent the rundown of CFTR Cl− currents in T84 intestinal epithelia and excised membrane patches from CHO cells expressing human CFTR (Becq et al. 1994; Travis et al. 1997; Luo et al. 1998). These results suggest that PP1 and/or PP2A may not play a major role in the dephosphorylation of CFTR in both T84 epithelia and CHO cells.

In contrast to calyculin A and okadaic acid, the phenylimidazothiazole drugs, (−)-bromotetramisole and levamisole, activated CFTR Cl− channels expressed in CHO cells (Becq et al. 1994, 1996; this study). Both (−)-bromotetramisole and levamisole are selective stereospecific inhibitors of alkaline phosphatases (Becq et al. 1996). Although the (−) enantiomer of bromotetramisole potently inhibits alkaline phosphatases from liver, bone and kidney, the (+) enantiomer is without effect (for review see Becq et al. 1996). In the absence of cAMP agonists, (−)-bromotetramisole and levamisole stimulated wild-type and mutant CFTR Cl− channels in cell-attached membrane patches, they did not elevate the intracellular concentration of either cAMP or Ca2+, and they enhanced the activity of CFTR Cl− channels in excised membrane patches that had been phosphorylated by PKA (Becq et al. 1994, 1996). However, much higher concentrations of (−)-bromotetramisole and levamisole were required to stimulate CFTR than were necessary to inhibit alkaline phosphatases (Becq et al. 1994, 1996). Becq et al. (1994, 1996) interpreted these data to suggest that phenylimidazothiazole drugs stimulate CFTR Cl− channels by inhibiting membrane-associated phosphatases.

Although (−)-bromotetramisole enhanced cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing human CFTR and increased the activity of human CFTR Cl− channels in excised membrane patches, the (+) enantiomer had the same effect. Both enantiomers of bromotetramisole stimulated the activity of human CFTR predominantly by decreasing the mean interburst duration. Two possible explanations for this effect of bromotetramisole are, first, a direct interaction of bromotetramisole with CFTR and, second, the inhibition of a different phosphatase by bromotetramisole. The effect of bromotetramisole is similar to that of phosphate, which probably interacts with the NBDs to increase the rate of opening of CFTR Cl− channels (Carson et al. 1994). However, phosphorylation of CFTR by PKA stimulates the ATPase activity of CFTR and hence, increases the rate of channel opening (Hwang et al. 1994; Li et al. 1996; Winter & Welsh, 1997; Luo et al. 1998; Mathews et al. 1998). Thus a more plausible explanation is that bromotetramisole may inhibit a phosphatase which has a relatively low affinity for the drug and does not distinguish between the two enantiomers. Because PP2C dephosphorylates CFTR and inactivates the channel by prolonging the interburst duration without altering burst duration (Travis et al. 1997; Luo et al. 1998), this phosphatase may be PP2C.

A surprising observation was that bromotetramisole stimulated iodide efflux from untransfected CHO cells. Iodide efflux is dependent on several factors including anion permeability, membrane potential, and the availability of pathways for counter-ions. It is possible that bromotetramisole might inhibit phosphatases that inactivate K+ channels. The resulting activation of K+ channels would hyperpolarize the membrane potential of the cell to create a favourable driving force for iodide efflux through anion channels that are already active. Consistent with the idea that bromotetramisole may modulate the activity of different types of ion channels, Mun et al. (1998) recently demonstrated that bromotetramisole inhibits intestinal Cl− secretion by blocking basolateral membrane K+ channels. These results may explain the failure of (−)-bromotetramisole to stimulate Cl− secretion in airway and intestinal epithelia from wild-type and G551D cystic fibrosis (CF) mice (Smith et al. 1998).

Like the effect of bromotetramisole on human CFTR, both enantiomers of bromotetramisole augmented cAMP-stimulated iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing murine CFTR. However, neither enantiomer stimulated murine CFTR Cl− channels in excised membrane patches. Based on our previous results (Lansdell et al. 1998) and those presented above, we tested for the presence of a subconductance state. When single-channel records were filtered at 50 Hz, we detected a very small subconductance state of murine CFTR.

Previous studies have described subconductance states of human CFTR Cl− channels, especially when CFTR is reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers and channel records are heavily filtered (Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Xie et al. 1995; Tao et al. 1996). Small subconductance states of human CFTR have been described by Tao et al. (1996), who observed three conductance states, termed H, m and L when either recombinant or native wild-type human CFTR were reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers. Transitions between these conductance states were affected by the presence or absence of Mg2+ in the extracellular solution, with millimolar concentrations of Mg2+ stabilizing the H state. In our experiments, the extracellular solution contained Mg2+, suggesting that the full open state of murine CFTR was not stabilized by extracellular Mg2+. Xie et al. (1995, 1996) examined the effect of deleting thirty amino acid residues (exon 5) from the first intracellular loop and nineteen from the second on the biosynthesis and function of human CFTR. These deletion mutants were defectively processed and not delivered to the cell membrane (Xie et al. 1995, 1996). However, when studied in planar lipid bilayers they formed regulated Cl− channels that occupied the m and L subconductance states more frequently than wild-type CFTR. Xie et al. (1995, 1996) interpreted these results to suggest that the first and second intracellular loops play important roles both in the biosynthesis of CFTR and by stabilizing the full open state of the channel.

The single-channel current amplitude of the subconductance state (O1) of murine CFTR was just 10 % that of the full open state (O2), but the Po of O1 was much increased compared with that of O2. However, several lines of evidence suggest that O1 was not a consequence of amino acid deletions like those described by Xie et al. (1995, 1996). First, the sequence of the murine CFTR cDNA that we used in these studies encoded a protein identical to that predicted by Yorifuji et al. (1991) for wild-type murine CFTR. Second, an antibody that recognizes the carboxyl terminus of murine CFTR immunoprecipitated a 180 kDa band from both native murine epithelial tissues and CHO cells expressing murine CFTR, but not from untransfected CHO cells (R. L. Dormer and M. A. McPherson, personal communication). Third, cAMP agonists stimulated similar amounts of iodide efflux from CHO cells expressing either human or murine CFTR. We interpret the data to suggest that recombinant wild-type murine CFTR has two open conductance states. Thus, the pattern of gating of recombinant murine CFTR may be described by transitions between a closed state and two open states: sustained openings to O1 and brief openings to O2 that occur from O1, but not C. The sustained openings of O1 suggest that the activity of murine CFTR Cl− channels expressed in CHO cells is much greater than we previously reported (Lansdell et al. 1998). The elevated activity of O1, in the presence of PKA and ATP, may explain why CFTR modulators failed to dramatically stimulate murine CFTR Cl− channels.

The finding that both enantiomers of bromotetramisole promote the opening of human CFTR Cl− channels has implications for CF. Like the substituted benzimidazolone, NS004 (Gribkoff et al. 1994), the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein (French et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1998), and the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (Arispe et al. 1998), bromotetramisole may be classified as an opener of the CFTR Cl− channel. Thus, as first suggested by Becq et al. (1994), bromotetramisole and related agents may be of value in the development of pharmacological treatments for CF. Levamisole, an orally active drug used to treat respiratory tract infections in children (Van Eygen et al. 1976), may be of particular value.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs R. L. Dormer and M. A. McPherson for permission to cite their unpublished data and Professor M. J. Welsh and Drs H. A. Berger, J. F. Cotten, S. M. Travis and S. J. Tucker for advice and critical comments. We thank Drs S. H. Cheng, C. R. O'Riordan and A. E. Smith (Genzyme, Framingham, MA, USA) for the generous gift of C127 and CHO cells expressing wild-type human CFTR. We also thank B. J. Stevenson for assistance with the PepTag® assay and Dr C. J. Kenyon for the use of his 96 well plate reader. This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Cystic Fibrosis Trust, and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

References

- Arispe N, Ma J, Jacobson KA, Pollard HB. Direct activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channels by 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (CPX) and 1,3-diallyl-8-cyclohexylxanthine (DAX) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:5727–5734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5727. 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Hwang T-C, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Coupling of CFTR Cl− channel gating to an ATP hydrolysis cycle. Neuron. 1994;12:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear CE, Li C, Kartner N, Bridges RJ, Jensen TJ, Ramjeesingh M, Riordan JR. Purification and functional reconstitution of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cell. 1992;68:809–818. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becq F, Jensen TJ, Chang X-B, Savoia A, Rommens JM, Tsui L-C, Buchwald M, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Phosphatase inhibitors activate normal and defective CFTR chloride channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:9160–9164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becq F, Verrier B, Chang X-B, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. cAMP- and Ca2+-independent activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channels by phenylimidazothiazole drugs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:16171–16179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16171. 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger HA, Travis SM, Welsh MJ. Regulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel by specific protein kinases and protein phosphatases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:2037–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger HA, Travis SM, Welsh MJ. Fluoride stimulates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel activity. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:L305–312. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.3.L305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MR, Travis SM, Welsh MJ. The two nucleotide-binding domains of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) have distinct functions in controlling channel activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:1711–1717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1711. 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MR, Travis SM, Winter MC, Sheppard DN, Welsh MJ. Phosphate stimulates CFTR Cl− channels. Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80668-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X-B, Tabcharani JA, Hou Y-X, Jensen TJ, Kartner N, Alon N, Hanrahan JW, Riordan JR. Protein kinase A (PKA) still activates CFTR chloride channel after mutagenesis of all 10 PKA consensus phosphorylation sites. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:11304–11311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SH, Rich DP, Marshall J, Gregory RJ, Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Phosphorylation of the R domain by cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates the CFTR chloride channel. Cell. 1991;66:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French PJ, Bijman J, Bot AG, Boomaars WEM, Scholte BJ, De jonge HR. Genistein activates CFTR Cl− channels via a tyrosine kinase- and protein phosphatase-independent mechanism. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:C747–753. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French PJ, Van doorninck JH, Peters RHPC, Verbeek E, Ameen NA, Marino CR, De jonge HR, Bijman J, Scholte BJ. A ΔF508 mutation in mouse cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator results in a temperature-sensitive processing defect in vivo. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98:1304–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI118917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nairn AC. Regulation of CFTR channel gating. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1994;19:513–518. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90141-4. 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MA, Greenwell JR, Argent BE. Secretin-regulated chloride channel on the apical plasma membrane of pancreatic duct cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1988;105:131–142. doi: 10.1007/BF02009166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff VK, Champigny G, Barbry P, Dworetzky SI, Meanwell NA, Lazdunski M. The substituted benzimidazolone NS004 is an opener of the cystic fibrosis chloride channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:10983–10986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson KL, Kopito RR. Conformational states of CFTR associated with channel gating: the role of ATP binding and hydrolysis. Cell. 1995;82:231–239. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan JW, Tabcharani JA, Chang X-B, Riordan JR. A secretory Cl channel from epithelial cells studied in heterologous expression systems. Advances in Comparative and Environmental Physiology. 1994;19:193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T-C, Horie M, Gadsby DC. Functionally distinct phospho-forms underlie incremental activation of protein kinase-regulated Cl− conductance in mammalian heart. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;101:629–650. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T-C, Nagel G, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Regulation of the gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl channels by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:4698–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Mathews CJ, Hanrahan JW. Phosphorylation by protein kinase C is required for acute activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by protein kinase A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:4978–4984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdell KA, Delaney SJ, Lunn DP, Thomson SA, Sheppard DN, Wainwright BJ. Comparison of the gating behaviour of human and murine cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels expressed in mammalian cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:379–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.379bq.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Wang W, Garami E, Hewryk M, Lee D, Rommens JM, Galley K, Bear CE. ATPase activity of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:28463–28468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Pato MD, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Differential regulation of single CFTR channels by PP2C, PP2A, and other phosphatases. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C1397–1410. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CJ, Tabcharani JA, Chang X-B, Jensen TJ, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Dibasic protein kinase A sites regulate bursting rate and nucleotide sensitivity of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.365bq.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun EC, Mayol JM, Riegler M, O'Brienapos;brien TC, Farokhzad OC, Song JC, Pothoulakis C, Hrnjez BJ, Matthews JB. Levamisole inhibits intestinal Cl− secretion via basolateral K+ channel blockade. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1257–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Cohn JA, Bertuzzi G, Greengard P, Nairn AC. Phosphorylation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:12742–12752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MM, Quinton PM. Deactivation of CFTR-Cl conductance by endogenous phosphatases in the native sweat duct. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:C474–480. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.2.C474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B-S, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou J-L, Drumm ML, Iannuzzi MC, Collins FS, Tsui L-C. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert FS, Tabcharani JA, Chang X-B, Dulhanty AM, Mathews C, Hanrahan JW, Riordan JR. cAMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator residue ser-753 and its role in channel activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:2158–2162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DN, Robinson KA. Mechanism of glibenclamide inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels expressed in a murine cell line. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;503:333–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.333bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SN, Delaney SJ, Dorin JR, Farley R, Geddes DM, Porteous DJ, Wainwright BJ, Alton EWFW. The effect of IBMX and alkaline phosphatase inhibitors on Cl− secretion in G551D cystic fibrosis mutant mice. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C492–499. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabcharani JA, Chang X-B, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Phosphorylation-regulated Cl− channel in CHO cells stably expressing the cystic fibrosis gene. Nature. 1991;352:628–631. doi: 10.1038/352628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao T, Xie J, Drumm ML, Zhao J, Davis PB, Ma J. Slow conversions among subconductance states of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:743–753. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79614-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis SM, Berger HA, Welsh MJ. Protein phosphatase 2C dephosphorylates and inactivates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:11055–11060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.11055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van eygen M, Znamensky PY, Heck E, Raymaekers I. Levamisole in prevention of recurrent upper-respiratory-tract infections in children. Lancet. 1976;1:382–385. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Zeltwanger S, Yang IC-H, Nairn AC, Hwang T-C. Actions of genistein on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel gating: evidence for two binding sites with opposite effects. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:477–490. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MJ, Tsui L-C, Boat TF, Beaudet AL. Cystic fibrosis. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc.; 1995. pp. 3799–3876. [Google Scholar]

- Winpenny JP, Mcalroy HL, Gray MA, Argent BE. Protein kinase C regulates the magnitude and stability of CFTR currents in pancreatic duct cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C823–828. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter MC, Sheppard DN, Carson MR, Welsh MJ. Effect of ATP concentration on CFTR Cl− channels: a kinetic analysis of channel regulation. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:1398–1403. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80930-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter MC, Welsh MJ. Stimulation of CFTR activity by its phosphorylated R domain. Nature. 1997;389:294–296. doi: 10.1038/38514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Drumm ML, Ma J, Davis PB. Intracellular loop between transmembrane segments IV and V of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is involved in regulation of chloride channel conductance state. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:28084–28091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Drumm ML, Zhao J, Ma J, Davis PB. Human epithelial cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator without exon 5 maintains partial chloride channel function in intracellular membranes. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:3148–3156. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorifuji T, Lemna WK, Ballard CF, Rosenbloom CL, Rozmahel R, Plavsic N, Tsui L-C, Beaudet AL. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the murine cDNA for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Genomics. 1991;10:547–550. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90434-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]