Abstract

Mutations that disrupt Na+ channel fast inactivation attenuate lidocaine (lignocaine)-induced use dependence; however, the pharmacological role of slower inactivation processes remains unclear. In Xenopus oocytes, tryptophan substitution in the outer pore of the rat skeletal muscle channel (μ1-W402) alters partitioning among fast- and slow-inactivated states. We therefore examined the effects of W402 mutations on lidocaine block.

Recovery from inactivation exhibited three kinetic components (IF, fast; IM, intermediate; IS, slow). The effects of W402A and W402S on IF and IS differed, but both mutants (with or without β1 subunit coexpression) decreased the amplitude of IM. In wild-type channels, lidocaine imposed a delayed recovery component with intermediate kinetics, and use-dependent block was attenuated in both W402A and W402S.

To examine the pharmacological role of IS relative to IM, drug-exposed β1-coexpressed channels were subjected to 2 min depolarizations. Lidocaine had no effect on sodium current (INa) after a 1 s hyperpolarization interval that allowed recovery from IM but not IS, suggesting that lidocaine affinity for IS is low.

Both W402 mutations reduced occupancy of IM in drug-free conditions, and also induced resistance to use-dependent block. We propose that lidocaine-induced use dependence may involve an allosteric conformational change in the outer pore.

Voltage-gated sodium (Na+) channels are pore-forming integral membrane proteins responsible for both the initiation and propagation of action potentials in excitable tissues. When depolarized, Na+ channels transiently open, and then enter inactivated states from which opening does not occur. Recovery from inactivation requires an intervening period of hyperpolarization. Local anaesthetics such as lidocaine (lignocaine) produce use-dependent block by delaying recovery from inactivation, thereby reducing the number of channels available to open with successive depolarizing stimuli (Courtney, 1975). There is considerable evidence to suggest that a direct interaction between lidocaine and inactivation underlies use-dependent drug action (Hille, 1977; Hondeghem & Katzung, 1977; Cahalan, 1978; Bean et al. 1983; Bennett et al. 1995a; Balser et al. 1996b). However, detailed analyses reveal multiple kinetic components in inactivation gating, suggesting that channels assume several distinct inactivated conformations (Patlak, 1991). Hence, it remains unclear whether lidocaine action is equally sensitive to all components of inactivation, or rather, is preferentially influenced by a particular inactivation process.

Skeletal muscle Na+ channels (μ1), when expressed in Xenopus oocytes, exhibit multiple kinetic components of recovery from inactivation (Krafte et al. 1988; Moorman et al. 1990; Zhou et al. 1991; Chang et al. 1996). Even after very brief (≤ 50 ms) depolarizations, μ1 α subunits enter several distinct inactivated conformations: a fast-inactivated state that recovers rapidly (τ < 5 ms at −100 mV) and at least two additional slow-inactivated states with much longer recovery time constants spanning an order of magnitude (τ = 350–3500 ms) (Nuss et al. 1996). Coexpression of the subsidiary β1 subunit markedly decreases the magnitude of all of the slow recovery components (Zhou et al. 1991; Bennett et al. 1993; Cannon et al. 1993). In addition, β1 coexpression attenuates use-dependent lidocaine blockade, reducing the drug-induced delay in recovery from inactivation (Balser et al. 1996c; Makielski et al. 1996). In μ1 channels the β1-induced reduction in one or more of the slow inactivation gating components may underlie the inhibition of use-dependent lidocaine action (Balser et al. 1996c).

Specific point mutations within the Na+ channel α subunit also modify recovery from inactivation. Both engineered and naturally occurring mutations near the cytoplasmic face of the channel, including the III–IV interdomain linker (West et al. 1992; Bennett et al. 1995b; Wang et al. 1995; Hayward et al. 1996) and the S6 segment of domain IV (McPhee et al. 1994), disrupt fast inactivation (denoted IF). Further, these and other mutations in close proximity attenuate use-dependent local anaesthetic action (Ragsdale et al. 1994, 1996; Bennett et al. 1995a; Balser et al. 1996b) suggesting that residues at these internal locations may concurrently form part of the fast-inactivation gating apparatus and contribute to the local anaesthetic receptor. Conversely, the structural underpinnings of the slower inactivation gating processes are less clear, as are the effects of these gating processes on local anaesthetic action. The classical slow inactivated state, originally described in neuronal preparations (Adelman & Palti, 1969; Chandler & Meves, 1970), is induced by long depolarizations (many seconds) and requires similar periods of hyperpolarization for recovery. Widely scattered mutations in the μ1 channel, including T698M in domain II S5, M1585V in domain IV S6 (both linked to hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis) (Cummins & Sigworth, 1996; Hayward et al. 1997), and N434A in domain I S6 (Wang & Wang, 1997) modify a slow inactivation gating process fitting the classic definition. When α subunits are expressed without β1 in Xenopus oocytes, our studies have shown that a cysteine substitution in the domain I outer P-segment (W402C) attenuates slow recovery components induced by brief depolarizations (Balser et al. 1996a). The extent to which these outer pore mutations alter the classic slow inactivation gating process remains unclear.

We have exploited the unique effects of 402-position substitutions expressed in Xenopus oocytes to examine how mutations that change the partitioning between fast and slow inactivation gating influence use-dependent lidocaine action. These mutations reside in the outer pore, distant from the putative fast inactivation gate (West et al. 1992) and lidocaine binding sites (Ragsdale et al. 1994; Bennett et al. 1995a). Our data indicate that (1) in both the absence and presence of β1, W402 substitutions reduce the occupancy of an inactivated state possessing intermediate recovery kinetics (denoted IM), (2) W402 mutations are sufficient to reduce use-dependent lidocaine block during depolarizations lasting ≤ 1 s, and (3) occupancy of the classic, slowly recovering IS state during prolonged depolarizations relieves lidocaine block. These findings suggest a linkage between allosteric conformational changes involving the outer pore and lidocaine-induced use dependence.

METHODS

Mutagenesis and channel expression

Site-directed mutagenesis of the μ1 Na+ channel α subunit (Trimmer et al. 1989) was performed on a full-length cDNA clone encoding the wild-type μ1 channel. The Xenopus oocyte expression vector pSP64T was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mutagenesis. Both sense and antisense oligonucleotides (30–34mer) containing the desired mutation(s) were used as primers for amplification with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR product was treated with Dpn I to select for the mutant plasmid and then transformed into E. coli for subsequent isolation and purification using standard protocols. All modifications were confirmed by di-deoxy sequencing of the region of the α subunit containing the mutation. After confirmation of the desired plasmid constructs, in vitro mRNA transcription was performed on each using the SP6 promoter region in pSP64T and commercially available reagents (Gibco, Gaithersburg).

Xenopus laevis oocytes were harvested from human chorionic gonadotrophin-primed adult females (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI, USA) after 30 min of submersion anaesthesia in an aqueous solution containing 0.17% 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (methanesulphonate salt; Sigma). All procedures surrounding the care and use of these animals conformed to institutional animal care committee review guidelines. Oocytes were isolated by digestion in a 2 mg ml−1 solution of collagenase (Type IA; Sigma) and stored in a modified Barth's solution containing (mm): 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 15 Tris base, 0.3 Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 0.41 CaCl2·6H2O, 0.82 MgSO4·7H2O, 5 sodium pyruvate, 0.5 theophylline; supplemented with 100 u ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 250 ng ml−1 fungizone and 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin. Oocytes were injected with 50 nl of a 0.1–0.25 μg μl−1 solution of cRNA transcribed from wild-type or mutant cDNA. In some experiments, an equimolar ratio of similarly transcribed rat brain β1 subunit RNA (Isom et al. 1992) was coinjected with the α subunit cRNA. Pairwise injections of both wild-type and mutant cRNAs were made into the same batch of oocytes in order to facilitate direct comparisons. To minimize the risk that changes in gating resulted from stray mutations, mutant phenotypes that differed from wild-type (W402A, W402S) were confirmed by injection of mRNAs derived from at least two independent mutagenic clones.

Electrophysiology and data analysis

Whole-cell currents were recorded using a two-electrode voltage clamp (OC-725B; Warner Instrument Corp., Hamden, CT, USA), 1–3 days after injection of the oocytes. Currents were measured using electrodes of 1–3 MΩ resistance when filled with 3 m KCl. Currents were recorded in frog Ringer (ND-96) solution containing (mm): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2; pH 7.6. Currents were low-pass filtered at 1–2 kHz and sampled at 3–10 kHz using custom-written software. Recovery from inactivation was measured using a paired-pulse voltage clamp protocol (Fig. 1A, top). After depolarization to −20 mV (P1: 50 ms, 1 s or 2 min as indicated in figure legends and text), oocytes were hyperpolarized to −100 mV for varying test intervals. Peak inward Na+ current (INa) was measured during a second pulse to −20 mV (P2) following the test interval. Fractional recovery of INa from inactivation at each test interval was estimated as the P2/P1 ratio.

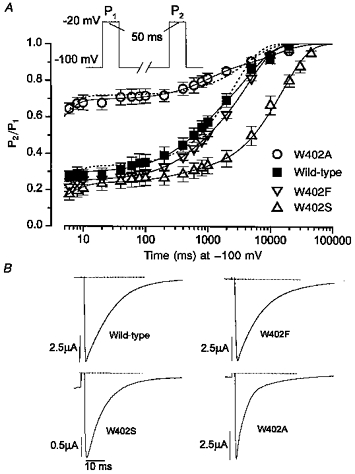

Figure 1. Inactivation of W402 mutant Na+ channel α subunits with β1 omitted.

A, wild-type and W402 mutant Na+ channels were expressed without β1 in Xenopus oocytes as described in Methods. Individual oocytes (wild-type, n = 7; W402F, n = 5; W402A, n = 9; W402S, n = 9) were subjected to the double-pulse voltage clamp protocol shown (top). Cells were held at a resting potential of −100 mV and then depolarized to −20 mV for 50 ms (P1), followed by a variable recovery period (6–30 000 ms) and a second depolarization to −20 mV for 50 ms (P2). Recovery from inactivation was measured as the ratio of the amplitudes of INa (P2/P1) and plotted on a logarithmic scale in order to emphasize the separation between the fast and slower components of recovery. Continuous lines are least-squares fits of a three-exponential expression (y =AF[1 - exp(-t/τF)]+AM[1 - exp(-t/τM)]+AS[1 - exp(-t/τS)]) to the mean data. Grouped parameters (means ± s.e.m.) determined from the three-exponential fits to the recovery data from individual oocytes are provided in Table 1. The dashed lines show inferior least-squares fits of a two-exponential expression that includes only a single slow recovery component (y =AF[1 - exp(-t/τF)]+A2[1 - exp(-t/τ2)]) to the wild-type and W402A mean data. B, the rate of macroscopic current decay was examined for the wild-type channel and each of the W402 mutants. Whole-cell Na+ currents were measured during 50 ms depolarizations to −20 mV from representative oocytes expressing the indicated Na+ channel genotype. Cells were held at a resting potential of −100 mV (holding current shown). The dotted lines indicate the zero current level. Peak amplitudes have been normalized for comparison, with absolute current magnitudes indicated by the scale bars.

In all cases, lidocaine HCl (2% preservative free; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA) was added to the ND-96 bathing solution at a concentration of 200 μm. With lidocaine present, a recovery period at −100 mV of at least 20 s (45 s for W402S without β1 coexpression) was allowed prior to each successive P1 measurement in order to prevent cumulative inactivation. Fractional recovery data (P2/P1) were fitted to multi-exponential functions of the general form y = ΣAi(1—exp(-t/τi)) using non-linear least-squares methods (Microcal Origin version 4.10, Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, USA) to determine the amplitudes and time constants associated with recovery from fast- and slow-inactivated states. Due to clamp speed limitations associated with the two-electrode voltage clamp in Xenopus oocytes (the peak INa is delayed by ≤ 3 ms, Fig. 1B), the time constant of development and/or recovery from fast inactivation (typically < 5 ms) cannot be measured accurately and is not reported. Pooled data are expressed as means ± s.e.m., and statistical comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA (Origin) with P ≤ 0.05 indicating significance. All electrophysiological recordings were made at room temperature (20–22°C).

RESULTS

The W402 mutations have diverse effects on inactivation gating in the absence of the β1 subunit

Figure 1A shows the fractional recovery of peak whole-cell INa (P2/P1) as a function of time at −100 mV after the inactivating (P1) pulse. When expressed alone in Xenopus oocytes and subjected to brief depolarizations (50 ms), μ1 α subunits exhibit a small-amplitude component of fast recovery from inactivation (IF) that is complete within 10 ms. For wild-type channels (▪), recovery is dominated by two additional slower components of intermediate (IM) and long (IS) duration. The continuous lines show least-squares fits of an exponential equation that includes all three kinetic components to the mean data (see legend for equation, Table 1 for fitted parameters to individual data sets). Efforts to fit the data using a two-exponential expression that contains only one slow component produced large systematic errors (superimposed dotted lines). Figure 1A also shows the range of effects of three different amino acid substitutions at the 402 position on recovery from inactivation. Similar to the effect of the cysteine mutant (W402C) (Balser et al. 1996a), alanine substitution (W402A) markedly increased the amplitude of the fast component (AF) from 0.30 ± 0.04 (wild-type) to 0.70 ± 0.04 (W402A; P < 10−5, see also Fig. 4). In contrast, serine substitution did not increase the relative degree of fast inactivation (AF: 0.24 ± 0.04, P = 0.32versus wild-type); rather, the mutation markedly increased the amplitude of the slowest recovery component (AS) from 0.43 ± 0.05 (wild-type) to 0.71 ± 0.04 (W402S). Consequently, in both W402S and W402A the amplitude of the intermediate component (AM) was reduced (Fig. 2C, open bars): wild-type, 0.27 ± 0.04; W402A, 0.11 ± 0.03 (P ≤ 0.01versus wild-type) and W402S, 0.04 ± 0.03 (P ≤ 10−4versus wild-type). The conservative substitution of an aromatic residue (phenylalanine: W402F) did not significantly change partitioning among the three inactivated states (Fig. 1A).

Table 1.

Drug-free time-dependent recovery of availability (−β1)

| n | AF | AM | τM (ms) | AS | τS (ms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 7 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 1011 ± 175 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 9361 ± 3593 |

| W402A | 9 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 593 ± 122 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 11913 ± 2383 |

| W402S | 9 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 362 ± 74 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 15265 ± 1951 |

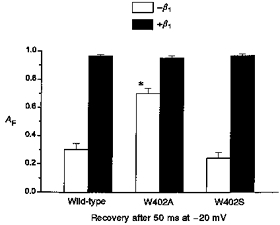

Figure 4. Slow gating components of W402 mutants are attenuated by β1 subunit coexpression.

Bar graph showing the effect of β1 coexpression on the relative magnitude of the fast recovery component AF. Data are the means ± s.e.m. from the parameters determined by fitting three- (-β1) or two- (+β1) exponential functions to the individual data sets (Figs 1A and 3B respectively). * Significant difference from wild-type (P < 10−5) for the -β1 W402A data. With β1 coexpression, the mutant and wild-type AF were markedly increased and did not differ significantly.

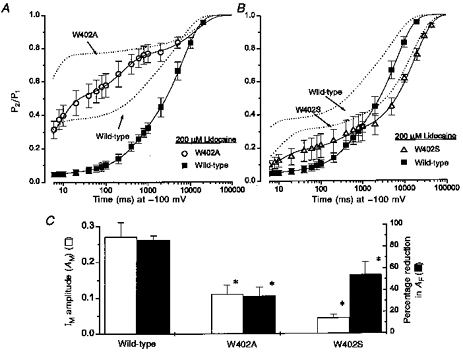

Figure 2. W402 mutant channels with β1 omitted and the effects of lidocaine.

A and B, the symbols (wild-type, n = 4; W402A, n = 4; W402S, n = 4) are data obtained during lidocaine exposure (200 μm) using the same voltage-clamp protocol as in Fig. 1A. The continuous lines are fits of a three-exponential function (legend, Fig. 1A) to the mean data. Time constants for the IF component are not reported due to clamp speed limitations (see Methods). Wild-type: AF = 0.05, AM = 0.21, τM = 516 ms, AS = 0.74, τS = 6586 ms. W402A: AF = 0.49, AM = 0.27, τM = 241 ms, AS = 0.25, τS = 13904 ms. W402S: AF = 0.18, AM = 0.11, τM = 297 ms, AS = 0.72, τS = 17992 ms. The dotted lines are three-exponential fits to mean data obtained from the same oocytes during the preceding drug-free control period. Wild-type: AF = 0.37, AM = 0.20, τM = 597 ms, AS = 0.43, τS = 5484 ms. W402A: AF = 0.76, AM = 0.03, τM = 292 ms, AS = 0.20, τS = 14663 ms. W402S: AF = 0.31, AM = 0.06, τM = 475 ms, AS = 0.63, τS = 15551 ms. C, the open bars show the amplitude of IM (AM) in the absence of drug (from Table 1). Filled bars show the percentage reduction in AF due to the lidocaine-imposed delay in recovery. Observations are from paired oocytes (n = 4) in each group. * Significant difference from wild-type (see text).

Previous studies have shown that at least two kinetic components underlie the macroscopic current decay during Na+ channel depolarization (Moorman et al. 1990; Zhou et al. 1991; Chang et al. 1996). The slow terminal decay phase was linked to a mode switch (mode 1 to mode 2), characterized by prolonged bursting during depolarization, and delayed recovery from inactivation. Coexpression with the β1 subunit eliminated the slow component of macroscopic current decay and accelerated recovery from inactivation (Zhou et al. 1991; Isom et al. 1992; Bennett et al. 1993; Cannon et al. 1993). Similarly, substitutions at the 402 position that produce faster recovery from inactivation also promoted more rapid decay during depolarization (Fig. 1B). Like W402C (Tomaselli et al. 1995; Balser et al. 1996a), the time from peak INa to 90% decay for W402A was reduced (16.3 ± 0.6 ms, n = 7) compared with wild-type (22.6 ± 0.9 ms, n = 7, P < 0.0001). Conversely, the decay rates of W402S and W402F were not hastened compared with wild-type (W402S: 23.8 ± 1.3 ms, n = 7; W402F: 27.2 ± 1.0, n = 5), and neither of these mutations increased the amplitude of the fast recovery component (AF; Fig. 1A).

W402 mutations attenuate use-dependent lidocaine block

Figure 2A and B shows measurements of recovery from inactivation following 50 ms depolarizations for W402A and W402S in the presence of lidocaine (200 μm). The dotted lines show the mean data for each group prior to drug exposure. The symbols show the data obtained in the presence of lidocaine, with continuous lines showing the non-linear least-squares fits to the mean data. In each case lidocaine delayed recovery, reducing the amplitude of IF (AF) in the wild-type by 83.5 ± 6% (Fig. 2C, filled bars). Despite the opposite effects of W402A and W402S on IF and IS in drug-free conditions (Fig. 1A, Table 1), both mutants reduced the magnitude of the slow recovery component imposed by lidocaine (Fig. 2C, percentage reduction in AF: W402A, 35 ± 8%, P ≤ 0.003versus wild-type; W402S, 52 ± 10%, P ≤ 0.03versus wild-type). Notably, under drug-free conditions W402A reduced IM by increasing IF and W402S reduced IM by increasing IS (Fig. 2C, open bars). These results suggest a linkage between the occupancy of IM and the ability of lidocaine to induce delayed recovery of channel availability.

β1 subunit coexpression reduces slow gating of W402 mutants

The prominence of slow (mode 2) gating in wild-type channels in the absence of β1, and the hastening of the decay of macroscopic current by W402A (Fig. 1B), raise the possibility that the mutations reduce lidocaine action by decreasing mode 2 gating. However, the similar effects of W402A and W402S on lidocaine action (Fig. 2C) suggest otherwise. To examine this issue, we first examined the effects of β1 coexpression on W402A and W402S in drug-free conditions (Fig. 3). Coexpression with β1 hastened the rate of macroscopic current decay for not only wild-type (Moorman et al. 1990; Zhou et al. 1991; Chang et al. 1996), but also W402A and W402S channels (Fig. 3A). Clamp speed limitations did not allow sufficient resolution to determine whether the fast inactivation gating characteristics of the β1-coexpressed mutants differed from wild-type; however, the slowly decaying components (e.g. Fig. 1B) were clearly attenuated by β1 coexpression. Similarly, following 50 ms depolarizations (as in Fig. 1A), occupancy of IF for the wild-type channel and both mutants was markedly increased by β1 coexpression (Fig. 3B). Figure 4 compares the amplitude of the fast recovery component following 50 ms depolarizations with and without β1 coexpressed. With β1 omitted, the amplitude of the fast recovery component was heavily influenced by the mutations (e.g. W402A). Conversely, with β1 coexpressed the size of the slow recovery component was minimized (AF > 95%) such that differences in recovery between the mutant and wild-type channels were less apparent. These results suggest that β1 subunit coexpression stabilizes mode 1 (rapid) gating of both W402A and W402S, similar to its effect on the wild-type channel (Zhou et al. 1991).

Figure 3. Gating effects of the W402 mutations during brief depolarizations are reduced by β1 subunit coexpression.

A, whole-cell currents were recorded during a 50 ms depolarization to −20 mV. Holding currents during the preceding interval at −100 mV are shown. Currents were normalized to the peak INa for purposes of comparison, and the scale bars indicate absolute current magnitudes. B, using the same double-pulse voltage-clamp protocol (top, Fig. 1), currents from oocytes expressing either wild-type +β1 (n = 7), W402A +β1 (n = 11) or W402S +β1 (n = 4) were measured. Coexpression with β1 reduced the amplitude of the slow recovery components. The continuous lines show fits of a two-exponential function (legend, Fig. 1A) to the mean data. Due to clamp-speed limitations, only the amplitude (AF) for the IF component is reported. Wild-type: AF = 0.94, A2 = 0.06, τ2 = 440 ms. W402A: AF = 0.96, A2 = 0.04, τ2 = 1042 ms. W402S: AF = 0.95, A2 = 0.05, τ2 = 1051 ms.

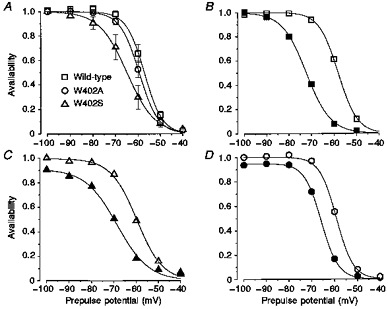

Effects of the W402 mutations on drug-free and drug-exposed voltage-dependent availability

If lidocaine delays recovery from inactivation by producing a mode shift, or by interacting preferentially with mode 2 channels, then β1 coexpression should minimize any difference in lidocaine sensitivity between wild-type and W402 channels. Figure 5A shows INa availability data over a range of membrane potentials under drug-free conditions with β1 coexpressed. Availability of INa was assessed after a 5 s period at each membrane potential. A Boltzmann function (see legend) was fitted to the mean data (continuous lines, Fig. 5A) and to each of the individual data sets. The wild-type and W402A availability curves did not differ significantly (V1/2: −57.1 ± 1.3 and −59.4 ± 1.2 mV, respectively). However, V1/2 for W402S was shifted negatively (−65.2 ± 3.0 mV, P < 0.05) and the slope factor (δ) was also changed from −3.8 ± 0.1 mV to −5.4 ± 0.6 mV (P < 0.01). A negative V1/2 shift was previously shown for W402C (Tomaselli et al. 1995).

Figure 5. Steady-state availability of wild-type and mutant Na+ channels coexpressed with β1.

From a holding potential of −100 mV, oocytes were clamped for 5 s to prepulse potentials ranging from −100 to −40 mV, followed by a 50 ms test pulse to −20 mV where INa peak current was assessed. Peak INa values for wild-type (n = 7), W402A (n = 5), or W402S (n = 5) in the absence (open symbols) and presence (filled symbols) of 100 μm lidocaine were normalized to the pre-drug value measured for the −100 mV prepulse. A, availability data from oocytes expressing channels prior to drug exposure. The symbols represent group means. Non-linear least-squares fits of a Boltzmann function (1 + exp[(V -V1/2)/δ]−1) to the individual data sets were used to estimate V1/2 and δ (mV, means ± s.e.m.). Wild-type: V1/2 =−57.1 ± 1.3, δ = 3.8 ± 0.1. W402A: V1/2 =−59.4 ± 1.2, δ = 4.1 ± 0.3. W402S: V1/2 =−65.2 ± 2.7, δ = 5.4 ± 0.6. The continuous lines are Boltzmann fits to the mean data for illustrative purposes. B, C and D, paired observations before and during lidocaine exposure are shown for individual oocytes expressing wild-type (B), W402S (C) and W402A (D) channels. The V1/2 and δ parameters obtained from fitting availability data (from oocytes in A) during lidocaine exposure were as follows (mV). Wild-type: V1/2 =−70.7 ± 1.4, δ = 4.9 ± 0.2. W402A: V1/2 =−67.6 ± 1.2, δ = 4.2 ± 0.4. W402S: V1/2 =−75.0 ± 2.4, δ = 5.5 ± 0.6.

Figure 5B–D shows paired availability data recorded from individual oocytes expressing wild-type, W402A and W402S before (open symbols) and during 200 μm lidocaine exposure (filled symbols). Lidocaine shifted the availability curve in all oocytes expressing wild-type channels by 13.6 ± 0.9 mV (n = 7), consistent with earlier reports. The drug-induced hyperpolarizing shift was reduced by both W402A (−8.2 ± 0.9 mV, n = 5, P ≤ 0.005 compared with wild-type shift) and W402S (−9.8 ± 1.3 mV, n = 5, P ≤ 0.05 compared with wild-type shift). These findings suggest that mutations at the W402 position, although distant from the putative inactivation gate or lidocaine receptor, somehow attenuate the effect of lidocaine on inactivated channels. Although β1 coexpression minimized the gating differences between wild-type and W402 mutant channels during brief 50 ms depolarizations (Figs 3 and 4), longer depolarizations (here 5 s) revealed clear-cut gating changes in W402S (Fig. 5A). Additional experiments were aimed at determining whether gating effects of the mutations underlie their lidocaine resistance.

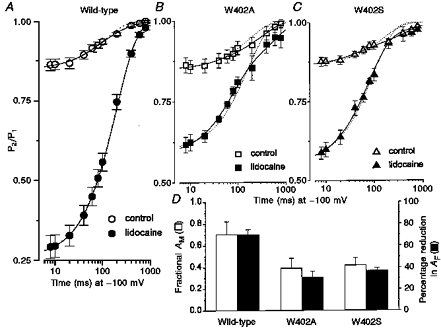

Effects of W402 mutations on the lidocaine-induced delay in recovery from inactivation

If the observed effects of the W402 mutants on lidocaine action are independent of modal gating, then the mutant effects on IM occupancy and lidocaine block should be apparent during longer depolarizing pulses with the β1 subunit coexpressed. To this end, we utilized longer (P1 = 1 s) depolarizations to recruit a measurable fraction of slowly recovering current under drug-free conditions. Figure 6A–C shows the fractional recovery (P2/P1) of INa in oocytes expressing wild-type, W402A and W402S channels (all +β1) before and after exposure to 200 μm lidocaine. Recovery intervals at −100 mV from 8 to 1000 ms allowed us to resolve the amplitude of IF (AF, the y-intercept) and the amplitudes and time constants of the slower recovery components. The dotted and continuous lines are least-squares fits of exponential functions that include one or two slow components, respectively, to the mean data (see legend). In drug-free conditions, AF was the same for wild-type (0.84 ± 0.02) and both mutants (W402A, 0.85 ± 0.02; W402S, 0.86 ± 0.02). Like recovery from inactivation without β1 coexpressed (Fig. 1A), slow recovery of β1-coexpressed channels after prolonged depolarization included at least two kinetic components (Table 2). Under drug-free conditions (Fig. 6A–C, open symbols), slow recovery of wild-type channels was dominated by an intermedate (IM) component (AM, 0.11 ± 0.03; τM, 74 ± 20 ms), but recovery also exhibited a low-amplitude IS component (AS, 0.05 ± 0.02; τS, 271 ± 30 ms). Notably, the time constants of both components were considerably shortened by β1 coexpression (compare with Table 1, Fig. 1A). For both W402A and W402S, the slow component was increased in magnitude at the expense of the intermediate component compared with the wild-type channel. The contribution of IM to the total drug-free slow recovery profile (AM/(AM + AS)) is plotted for the wild-type and both mutant channels in Fig. 6D (open bars). Although the amplitudes of the slow components are small due to β1 coexpression, both W402A and W402S reduced the amplitude of IM, similar to the effect seen with β1 omitted (Fig. 2C).

Figure 6. W402 mutant channels coexpressed with β1 and the effects of lidocaine.

A, B and C, oocytes expressing wild-type, W402A or W402S current were subjected to a voltage-clamp protocol similar to that of Fig. 1A, with the P1 pulse extended to 1 s. Fractional recovery from inactivation (P2/P1) was assessed at recovery intervals (−100 mV) ranging from 8 ms to 1 s to capture the amplitude of IF and the amplitude and time constants for IM and IS. The plotted symbols represent means ± s.e.m. fractional recovery from paired observations before and during exposure to lidocaine (200 μm) in oocytes expressing either wild-type (n = 5), W402A (n = 5) or W402S (n = 5) channels. The continuous lines are non-linear least-squares fits of the mean data to the exponential function y =AF+AM[1 - exp(-t/τM)]+AS[1 - exp(-t/τS)]. Parameters determined from fitting this function to the individual data sets (means ± s.e.m.) are provided in Table 2. The superimposed dotted lines show fits of a function that includes only a single slow component to the mean data: y =AF+A2[1 - exp(-t/τ2)]. These fits were visibly inferior in all cases except for the lidocaine-exposed wild-type data. D, the open bars show the fraction of slow recovery attributable to occupancy of IM (AM/(AM+AS)) in drug-free conditions. Fractional AM was as follows: wild-type, 0.70 ± 0.12 (n = 6); W402A, 0.39 ± 0.9 (n = 10, P = 0.05vs. wild-type); W402S, 0.42 ± 0.07 (n = 5, P = 0.08vs. wild-type). Filled symbols show the percentage reduction in AF due to the lidocaine-imposed delay in recovery. The W402 mutations attenuated both drug-free IM amplitude and lidocaine block (see text).

Table 2.

Time-dependent recovery of availability: paired observations with 200 μm lidocaine (+β1)

| n | AF | AM | τM (ms) | AS | τS (ms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||||

| Wild-type | 5 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 74 ± 20 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 271 ± 30 |

| W402A | 5 | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 73 ± 17 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 399 ± 89 |

| W402S | 5 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 53 ± 9 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 503 ± 58 |

| Lidocaine | ||||||

| Wild-type | 5 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 198 ± 11 | — | — |

| W402A | 5 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 75 ± 16 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 775 ± 370 |

| W402S | 5 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 74 ± 10 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 827 ± 306 |

Lidocaine exposure (filled symbols, Fig. 6A–C) imposed a slow recovery component, thereby reducing AF in the wild-type channel by 70 ± 4% (Fig. 6D, filled bars). Both W402A and W402S attenuated this drug effect (W402A, 31 ± 5%, P ≤ 0.001versus wild-type; W402S, 37 ± 2%, P ≤ 0.001versus wild-type). The slow recovery of both W402S and W402A was best fitted by a biexponential in lidocaine (continuous lines, Fig. 6A–C). The amplitude of the intermediate recovery component was increased by lidocaine (AM: W402A, 0.25 ± 0.02; W402S, 0.39 ± 0.05; P < 0.001versus drug free, Table 2). Similar to the results seen in the absence of β1 (Fig. 2A and B), block by lidocaine was reduced during the terminal (IS) recovery phase in both mutants. This was especially true for W402S, where the drug-free and drug-exposed recovery profiles superimposed during the IS phase. In contrast to the mutant channels, slow recovery of the lidocaine-exposed wild-type channel was well-characterized by a single exponential (see superimposed dotted and continuous lines). The time constant of the wild-type slow recovery component induced by lidocaine was 198 ± 11 ms, somewhat slower than the IM component in drug-free conditions (74 ± 20 ms).

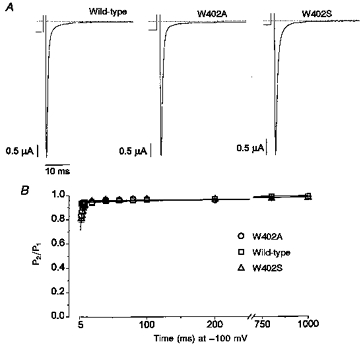

Occupancy of IS relieves μ1 channels from lidocaine block

Our findings suggest that an interaction between lidocaine and the slower (non-IF) inactivation gating processes may be selective for IM over IS. In order to clarify the role of IS in lidocaine action, oocytes expressing wild-type channels (+β1) were subjected to a paired-pulse protocol with a P1 pulse duration prolonged to 2 min (Fig. 7A, top). Recovery of INa was measured after either 100 ms or 1 s at −100 mV. We reasoned that prolonging the P1 pulse to 2 min would maximize occupancy of IS. Recovery after 100 ms would reflect channels occupying either IM or IS, while recovery after 1 s would allow full recovery of IM (τM = 74 ms) and provide a lower-limit measure of the fraction of channels remaining in IS. Figure 7A shows INa recordings from an oocyte subjected to this protocol before and during lidocaine exposure. Fractional recovery in drug-free conditions after 100 ms was 0.64, and only increased to 0.66 after 1 s at −100 mV, suggesting that in this oocyte after a 2 min P1 pulse most of the slowly recovering channels occupied IS rather than IM. In four oocytes (Fig. 7B), fractional recovery was 54 ± 4% after 100 ms and 68 ± 3% after 1 s. In experiments using W402A + β1 (not shown), fractional recovery after 1 s was reduced to 49 ± 6% (P ≤ 0.05vs. wild-type) consistent with the increase in IS amplitude already noted for W402A (Fig. 6B, Table 2).

Figure 7. Occupancy of IS and block by lidocaine.

Oocytes expressing wild-type channels were subjected to the voltage-clamp protocol shown (top). Oocytes were allowed to recover for a minimum of 30 s prior to each 2 min depolarization. Shown are pairs of whole-cell currents recorded from a representative oocyte in control solutions and during exposure to lidocaine. Currents were recorded at the beginning of the 2 min P1 pulse, and following recovery intervals of either 100 ms or 1 s. The pre- and post-lidocaine currents are offset for clarity. B, INa amplitude plotted as a function of the drug-free P1 current for 4 oocytes (paired comparisons) expressing wild-type channels. Following a 2 min depolarization, INa is reduced by lidocaine (200 μm) after a 100 ms recovery period at −100 mV, but not after a 1 s recovery period.

With lidocaine exposure (Fig. 7A, following a 30 s rest at −100 mV), wild-type INa measured during the first (P1) pulse was reduced to 80% of the control value due to tonic block (i.e. block developing at rest and/or during depolarization but prior to peak INa). After a 100 ms recovery interval, INa was further reduced to 43% of the control P1 value, due to the combined effects of tonic and use-dependent block. However, after a longer 1 s recovery interval, the drug-exposed current was identical to that recorded in the absence of drug (66% of the control P1 value). Similar results from four oocytes expressing μ1 channels are summarized in Fig. 7B. In all cases, lidocaine induced block that persisted at 100 ms, but had disappeared by 1 s even though many channels had not yet recovered from IS. These findings suggest that lidocaine has a low affinity for channels occupying the IS state.

DISCUSSION

The role of inactivation gating processes in lidocaine-induced use dependence

The internal position of the local anaesthetic binding site is supported by a number of independent experimental observations. First, membrane-impermeant lidocaine derivatives induce use-dependent block of neuronal Na+ channels only when exposed to the internal side of the membrane (Frazier et al. 1970; Strichartz, 1973). Second, protease digestion of the cytoplasmic face of the channel (Cahalan, 1978) eliminates both fast inactivation and use-dependent local anaesthetic block. Third, internally positioned residues in the III–IV linker (West et al. 1992) and in the domain IV S6 segment (McPhee et al. 1994) are critically involved in fast-inactivation gating, and mutation of these and other nearby residues reduces lidocaine affinity and attenuates use-dependent block (Ragsdale et al. 1994; Bennett et al. 1995a; Fan et al. 1996; Ragsdale et al. 1996). These findings support the concept of a high-affinity binding site for local anaesthetics in close proximity to the fast-inactivation gating structures (Hille, 1977).

Although residues in domain IV S6 and the III–IV linker are essential to high-affinity lidocaine binding, the mechanism by which bound lidocaine profoundly slows recovery from inactivation remains uncertain. Although slow dissociation of drug from the fast-inactivated state may explain slow recovery from inactivation (Hille, 1977), it is plausible that the local anaesthetic induces a conformational change and thereby produces slow recovery (Khodorov et al. 1976). Although the effects of the W402 mutations on drug-free channel gating were complex, we exploited this diversity to establish a linkage between outer pore conformational changes and lidocaine action. Previous studies (Nuss et al. 1996) have identified an inactivated state with recovery kinetics of intermediate duration in wild-type channels expressed without β1 in Xenopus oocytes. In the absence of β1 coexpression, the gating effects of W402S and W402A were disparate (Fig. 1A, Table 1). W402A increased IF amplitude at the expense of fractional occupancy of both IS and IM. Conversely, W402S increased IS occupancy at the expense of IM. Thus, both mutants reduced the amplitude of IM in drug-free conditions, implicating the outer pore as the part of the structural framework for this inactivated conformational state. When exposed to lidocaine, both mutants reduced the amplitude of the drug-induced slow recovery component (Fig. 2).

With β1 coexpressed, the amplitudes of the IM and IS components were reduced (Fig. 3) and more difficult to resolve. Nonetheless, experiments with long depolarizations clarified that the IM component persists with β1 coexpression (Figs 6 and 7); furthermore, the gating effects of W402A and W402S on IM were consistent with those obtained in the absence of β1 (Fig. 6A–C). Both mutants reduced the fractional occupancy of IM under drug-free conditions, and both reduced the amplitude of the drug-induced slow recovery component (Fig. 6D). Intriguingly, lidocaine enhanced occupancy of a non-conducting state with intermediate recovery kinetics similar (but not identical) to IM (Table 2). These findings suggest the possibility that occupancy of IM under drug-free conditions is mechanistically linked to the recovery delay induced by lidocaine binding.

Our data suggest that the classic slow recovery state (IS) has low affinity for lidocaine. First, the effects of W402A on the magnitude of IS in the absence and presence of β1 are opposite (AS was increased with β1 present and was reduced with β1 absent, Tables 1 and 2) yet in both conditions W402A reduced lidocaine action. Second, both in the absence (Fig. 2A and B) and presence (Fig. 6A–C) of β1 recovery from lidocaine block preceded full recovery from inactivation. This was most apparent for W402S (Figs 2B and 6C), where the drug-free and drug-exposed recovery curves nearly superimposed during the terminal (IS) recovery phase. Third, after prolonged 2 min depolarizations, lidocaine induced a slowly recovering component in wild-type channels that was present after 100 ms of recovery, but absent after 1 s of recovery at −100 mV (Fig. 7). We expected the magnitude of INa after 1 s of recovery to be smaller than the comparable current recorded in control solutions due to the combination of both unrecovered IS channels (∼30%) and tonic block (∼20%). However, after a 1 s recovery interval, INa was consistently identical to that recorded in the absence of drug (Fig. 7B). This is a startling result that can be rationalized if lidocaine induces channels to occupy the IM state in preference to the IS state, thus ‘stealing’ channels from the IS state and, in essence, hastening their recovery. Consistent with this view, after 1 s P1 pulses (Fig. 6A), lidocaine exposure eliminated the IS component in oocytes expressing wild-type channels. Notably, the IS component persisted with lidocaine exposure after 1 s P1 pulses for W402S and W402A (Fig. 6B and C). However, fewer W402S and W402A channels are blocked by lidocaine (Fig. 6B and C), and recovery from the lidocaine-induced IM state is hastened in the mutants (Table 2). Therefore, after a 1 s prepulse, a greater fraction of mutant channels remain available to enter IS with lidocaine present.

Evidence linking slow gating processes to drug-induced use dependence

Prior studies provide evidence supporting the notion that use-dependent local anaesthetic action may require an induced conformational change in the outer pore. Elevating the external [Ca2+] reduced a component of slow recovery in cardiac Na+ channels under drug-free conditions, and also reduced the lidocaine-induced delay in recovery from inactivation (Zilberter et al. 1991). Similarly, quaternary ammonium compounds bind only briefly (and internally) to the Shaker potassium channel, but nonetheless produce use-dependent block by reducing K+ permeation, allowing a conformational change in the outer pore (so-called ‘C-type’ inactivation) from which recovery is slow (Baukrowitz & Yellen, 1996). Although disruption of fast-inactivation Na+ channel gating structures (III–IV linker mutations) eliminates use-dependent block by low concentrations of lidocaine (≤ 400 μm), raising the lidocaine concentration to 1 mm restores lidocaine-induced use-dependent block to the F1304Q mutant (Balser et al. 1996b) and the IFM→QQQ triple mutant (Gingrich & Wagner, 1997). Therefore, lidocaine maintains the ability to induce a slow component of recovery in channels with defective fast inactivation, albeit at higher drug concentrations. While disruption of fast inactivation may lower the affinity of lidocaine for the channel, the ability of lidocaine to induce a component of slow recovery remains intact.

Single-channel studies indicate that β1 coexpression reduces the probability of mode 2 gating, thus accelerating macroscopic current decay during depolarization (Moorman et al. 1990; Zhou et al. 1991; Chang et al. 1996). It is possible that the effect of W402A in drug-free conditions to attenuate slow recovery in the absence of β1 (Fig. 1A) is related to a shift away from mode 2 gating. However, it is difficult to explain the effects of both mutants on IM and IS using this mechanism; IS is increased by W402S, while IM is reduced by both W402A and W402S. For the following reasons, it is also unlikely that a shift between gating modes 1 and 2 underlies the observed effects of W402A and W402S on lidocaine action. First, in Fig. 3A we show that with β1 coexpression the slow component of macroscopic current decay (linked to mode 2 gating) is eliminated from not only the wild-type channel, but also both W402A and W402S. Second, although the drug-free gating effects of the W402 mutations are greater with β1 omitted, the effects of the mutations to blunt lidocaine-induced slow recovery are equally robust with or without β1 coexpressed (compare Figs 2C and 6D). Nonetheless, on the basis of these experiments, we cannot exclude the possibility that previously undescribed mode shifts induced by the W402 mutants could underlie these results.

The possibility of an external local anaesthetic binding site has been suggested by the use-dependent block of the cardiac isoform of the Na+ channel by the membrane-impermeant lidocaine derivative QX-314 (Alpert et al. 1989). However, external QX-314 has no effect on neuronal or skeletal muscle channels, and recent mutagenesis studies indicate that QX-314 appears to bind to a single site in the expressed cardiac isoform, whether applied internally or externally (Ragsdale et al. 1994; Qu et al. 1995). Nonetheless, in the absence of definitive structural data, it remains possible that the effects of P-loop (W402) mutations on lidocaine-induced use dependence partly involves a through-protein conformational change that influences lidocaine receptor affinity.

Site-directed mutagenesis data suggest that W402 and the putative lidocaine receptor (IV S6) are not physically continuous. Cysteine-substitution experiments have revealed that the μ1 402 residue is accessible to externally applied (Pérez-García et al. 1996), but not internally applied (authors' unpublished observations) Cd2+ or thiol-specific covalent modifiers. Conversely the domain IV S6 local anaesthetic binding site (μ1 F1579) in both rat brain IIA (Qu et al. 1995) and μ1 channels (authors' unpublished observations) is blocked only by internal QX-314. Both W402A and W402S inhibit occupancy of an intermediate inactivated state (IM) with recovery kinetics that are similar to the lidocaine-induced recovery delay, suggesting that the effects of the W402 substitutions on lidocaine-induced use dependence may result from mutational effects that influence the conformation of the outer pore. Precedence for this mechanism of action is suggested by the linkage between internal quaternary ammonium use-dependent block of Shaker potassium channels and induction of C-type inactivation (Baukrowitz & Yellen, 1996), a constriction of the outer mouth of the pore (Liu et al. 1996). As a hypothesis for further examination, we propose that once bound to the Na+ channel, local anaesthetics may produce use-dependent block by inducing an allosteric conformational change involving amino acid residues in the outer pore.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid (Maryland Affiliate; J. R. B.) and National Institutes of Health grants R01 GM56307 (J. R. B), R01 HL50411 (G. F. T) and R01 HL52768 (E. M.). Salary support was provided by NIH K08 HL03781 (N. G. K) and the Clinician Scientist Award of the American Heart Association (J. R. B).

References

- Adelman WJ, Palti Y. The effects of external potassium and long duration voltage conditioning on the amplitude of sodium currents in the giant axon of the squid, Loligo pealei. Journal of General Physiology. 1969;54:589–606. doi: 10.1085/jgp.54.5.589. 10.1085/jgp.54.5.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert LA, Fozzard HA, Hanck DA, Makielski JC. Is there a second external lidocaine binding site on mammalian cardiac cells? American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:H79–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Nuss HB, Chiamvimonvat N, Pérez-García MT, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. External pore residue mediates slow inactivation in μ1 rat skeletal muscle sodium channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1996a;494:431–442. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Nuss HB, Orias DW, Johns DC, Marban E, Tomaselli GF, Lawrence JH. Local anesthetics as effectors of allosteric gating: lidocaine effects on inactivation-deficient rat skeletal muscle Na+ channels. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996b;98:2874–2886. doi: 10.1172/JCI119116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Nuss HB, Romashko DN, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Functional consequences of lidocaine binding to slow-inactivated sodium channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1996c;107:643–658. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. Use-dependent blockers and exit rate of the last ion from the multi-ion pore of a K channel. Science. 1996;271:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP, Cohen CJ, Tsien RW. Lidocaine block of cardiac sodium channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1983;81:613–642. doi: 10.1085/jgp.81.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PB, Makita N, George AL. A molecular basis for gating mode transitions in human skeletal muscle sodium channels. FEBS Letters. 1993;326:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81752-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PB, Valenzuela C, Li-Qiong C, Kallen RG. On the molecular nature of the lidocaine receptor of cardiac Na+ channels. Circulation Research. 1995a;77:584–592. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PB, Yazawa K, Naomasa M, George AL. Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995b;376:683–685. doi: 10.1038/376683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan MD. Local anesthetic block of sodium channels in normal and pronase treated squid axons. Biophysical Journal. 1978;23:285–311. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85449-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC, Mcclatchey AI, Gusella JF. Modification of the Na+ current conducted by the rat skeletal muscle α subunit by coexpression with a human brain β subunit. Pflügers Archiv. 1993;423:155–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00374974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler WK, Meves H. Slow changes in membrane permeability and long lasting action potentials in axons perfused with fluoride solutions. The Journal of Physiology. 1970;211:707–728. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SY, Satin J, Fozzard HA. Modal behavior of the μ1 Na+ channel and effects of coexpression of the β1 subunit. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2581–2592. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79829-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KR. Mechanism of frequency-dependent inhibition of sodium currents in the frog myelinated nerve by the lidocaine derivative gea 968. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1975;195:225–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Sigworth FJ. Impaired slow inactivation in mutant sodium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, George AL, Kyle JW, Makielski JC. Two human paramyotonia congenita mutations have opposite effects on lidocaine block of Na+ channels expressed in a mammalian cell line. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:275–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier DT, Narahashi T, Yamada M. The site of action and active form of local anesthetics. II. Experiments with quaternary compounds. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1970;171:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich KJ, Wagner L. Lidocaine induces phasic block of a mutant skeletal muscle Na+ channel lacking fast inactivation. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:A4 (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Cannon SC. Inactivation defects caused by myotonia-associated mutations in the sodium channel III-IV linker. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;107:559–576. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Cannon SC. Slow inactivation differs among mutant Na+ channels associated with myotonia and periodic paralysis. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:1204–1219. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78768-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Local anesthetics: hydrophilic and hydrophobic pathways for the drug-receptor reaction. Journal of General Physiology. 1977;69:497–515. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem LM, Katzung BG. Time- and voltage-dependent interactions of the antiarrhythmic drugs with cardiac sodium channels. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1977;472:373–398. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(77)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom LL, Dejongh KS, Patton DE, Reber BFX, Offord J, Charbonneau H, Walsh K, Goldin AL, Catterall WA. Primary structure and functional expression of the beta-1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel. Science. 1992;256:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1375395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodorov B, Shishkova L, Peganov E, Revenko S. Inhibition of sodium currents in frog Ranvier node treated with local anesthetics: role of slow sodium inactivation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1976;433:409–435. [Google Scholar]

- Krafte DS, Snutch TP, Leonard JP, Davidson N, Lester HA. Evidence for the involvement of more than one mRNA species in controlling the inactivation process of rat and rabbit brain Na+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:2859–2868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02859.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Dynamic rearrangement of the outer mouth of a K channel during gating. Neuron. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcphee JC, Ragsdale DS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A mutation in segment IVS6 disrupts fast inactivation of sodium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:12346–12350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makielski JC, Limberis JT, Chang SY, Fan Z, Kyle JW. Coexpression of β1 with cardiac sodium channel α subunits in oocytes decreases lidocaine block. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;49:30–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman JR, Kirsch GE, Vandongen AMJ, Joho RH, Brown AM. Fast and slow gating of sodium channels encoded by a single mRNA. Neuron. 1990;4:243–252. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss HB, Balser JR, Orias DW, Lawrence JH, Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Coupling between fast and slow inactivation revealed by analysis of a point mutation (F1304Q) in μ1 rat skeletal muscle sodium channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:411–429. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlak J. Molecular kinetics of voltage-dependent Na+ channels. Physiological Reviews. 1991;71:1047–1080. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.4.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García MT, Chiamvimonvat N, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Structure of the sodium channel pore revealed by serial cysteine mutagenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Rogers J, Tanada T, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of drug access to the receptor site for antiarrhythmic drugs in the cardiac Na+ channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:11839–11843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, Mcphee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science. 1994;265:1724–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.8085162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, Mcphee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Common molecular determinants of local anesthetic, antiarrhythmic, and anticonvulsant block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:9270–9275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strichartz GR. The inhibition of sodium currents in myelinated nerve by quarternary derivatives of lidocaine. Journal of General Physiology. 1973;62:37–57. doi: 10.1085/jgp.62.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Chiamvimonvat N, Nuss HB, Balser JR, Perez-Garcia MT, Xu RH, Orias DW, Backx PH, Marban E. A mutation in the pore of the sodium channel alters gating. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:1814–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmer JS, Cooperman SS, Tomiko SA, Zhou J, Crean SM, Boyle MB, Kallen RG, Sheng Z, Barchi RL, Sigworth FJ, Goodman RH, Agnew WS, Mandel G. Primary structure and functional expression of a mammalian skeletal muscle sodium channel. Neuron. 1989;3:33–49. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Shen J, Splawski I, Atkinson D, Li Z, Robinson JL, Moss AJ, Towbin JA, Keating MT. SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:805–811. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang GK. A mutation in segment I-S6 alters slow inactivation of sodium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:1633–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78809-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J, Patton D, Scheuer T, Wang Y, Goldin AL, Catterall WA. A cluster of hydrophobic amino acid residues required for fast Na+-channel inactivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:10910–10914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Potts JF, Trimmer JS, Agnew WS, Sigworth FJ. Multiple gating modes and the effect of modulating factors on the μ1 sodium channel. Neuron. 1991;7:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90280-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberter Y, Motin L, Sokolova S, Papin A, Khodorov B. Ca-sensitive slow inactivation and lidocaine-induced block of sodium channels in rat cardiac cells. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1991;23:61–72. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90025-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]