Abstract

Vesicular secretion from single human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) was monitored by changes in membrane capacitance (Cm). Secretion was evoked by dialysis with strongly buffered intracellular free Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i), flash photolysis of Ca2+-loaded DM-nitrophen or caged InsP3, or by thrombin. [Ca2+]i was monitored spectrofluorimetrically with furaptra. The results show that a large, slowly rising component of vesicular secretion requires prolonged exposure to high [Ca2+]i.

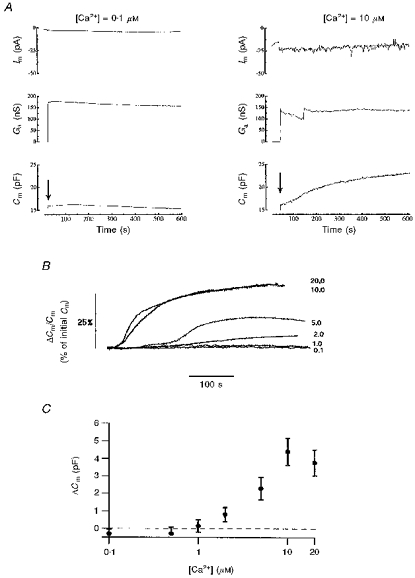

Cm increased during intracellular perfusion with [Ca2+] buffered in the range 1.0–20 μM. Changes in Cm comprised an initial slowly rising small component of 0.1–0.5 pF followed by a faster rising larger component of up to ∼7 pF, seen when [Ca2+]i > 2 μM and which was maximal at 10–20 μM Ca2+.

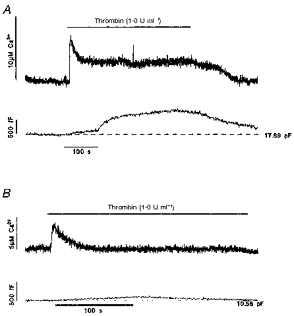

Thrombin evoked rapid initial elevations of [Ca2+]i to a peak of 7.1 ± 1.5 μM (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5) that declined within ∼20–30 s with thrombin present either to resting levels or to a maintained elevated level of 2.0 ± 0.7 μM (mean ± s.e.m., range 1.0–3.6 μM, n = 3). Transient [Ca2+]i rises were associated with small, slowly rising increases in Cm of 0.1–0.2 pF, that recovered to pre-application levels over 2–3 min. Maintained elevations of [Ca2+]i caused larger, faster-rising sustained increases in Cm to 1.14 ± 0.12 pF (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3). Separate specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed that 1.0 U ml−1 thrombin produced secretion of von Willebrand factor in HUVEC cultures.

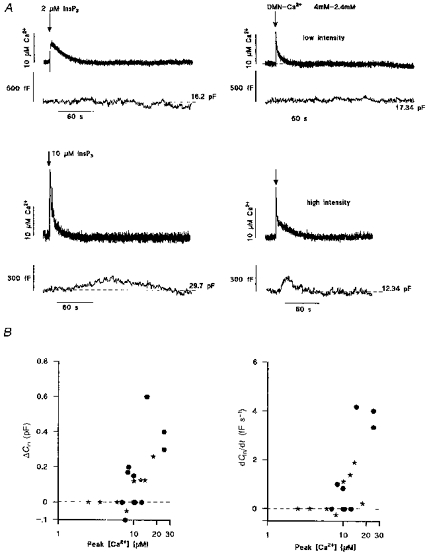

Short-lived [Ca2+]i elevations with a peak of 3–25 μM and a duration of approximately 20 s generated by flash photolysis of caged InsP3 or DM-nitrophen produced either no net change in Cm, or small slow increases of ∼0.1–0.6 pF at up to 5 fF s−1 that recovered to pre-flash levels over 2–3 min.

Maintained elevations of [Ca2+]i in the range 1–28 μM produced by flash photolysis of DM-nitrophen caused large increases in Cm, up to ∼4 pF, corresponding to ∼25–30% of the initial cell Cm. The maximum rate of change of Cm was up to 50 fF s−1 at steady [Ca2+] up to 20 μM; Cm recovered towards pre-flash levels only when [Ca2+] had declined.

Vascular endothelial cells regulate blood flow and haemostasis by releasing several locally acting mediators in response to mechanical, biochemical or neural signals. Some mediators are made and released ‘on demand’ by the endothelium, including prostacyclin, nitric oxide and platelet-activating factor. Others are stored in preformed storage granules and secreted by exocytosis. These are von Willebrand factor (vWf), tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), endothelin-1 (ET) and Protein S. These mediators function to maintain blood as a fluid and control blood flow under normal conditions, but also prevent leaks by promoting the formation of platelet plugs at sites of vascular injury (reviewed by Mann, 1997).

With the exception of ET, a rise in endothelial intracellular free calcium ion concentration ([Ca2+]i) produced by Ca2+-mobilizing hormones is thought to play a central role in the regulated release of each of these mediators (Stern et al. 1986; Hamilton & Simms, 1987; Carter & Pearson, 1992; Birch et al. 1992; Kooistra et al. 1994; Frearson et al. 1995; Lupu et al. 1995; van den Eijnden-Schrauwen et al. 1997; Emeis et al. 1997). Limitations in the sensitivity of detection assays prevent direct simultaneous measurements of secretion and [Ca2+]i at the single cell level. However, morphological and biochemical evidence suggests that regulated secretion of vWf, t-PA, TFPI and Protein S from endothelial cells involves the fusion with and subsequent recycling of secretory vesicles with the surface membrane (Stern et al. 1986; Wagner, 1990; Emeis et al. 1997). It is likely that this would result in changes of cell Cm which could be detected electrophysiologically and provide a means by which regulated secretion from storage granules could be followed in single endothelial cells. vWf, t-PA and TFPI are stored in their own separate storage granules within endothelial cells (Emeis et al. 1997). The best characterized of these storage granules is the Weibel-Palade (WP) body that contains vWf (Wagner, 1990). WP bodies are tubular structures (1–4 μm in length, 0.1–0.2 μm in diameter) that show characteristic longitudinal striations, thought to be condensed polymers of vWf. The WP body membrane also contains the leucocyte adhesion molecule P-selectin, which appears on the cell surface as a result of exocytosis during regulated secretion of vWf (Wagner, 1990). The t-PA storage granules are much smaller, ∼0.1 μm in diameter, and are similar in size to those described for ET and Protein S (Harrison et al. 1995; Stern et al. 1986).

In the experiments reported here changes in human endothelial cell Cm were measured during whole-cell recording as a single cell index of secretion (Neher & Marty, 1982). The [Ca2+] dependence, extent and time course of Cm changes were investigated in response to (1) intracellular dialysis with buffered Ca2+ solutions in the range known to trigger vWf secretion (Scrutton & Pearson, 1989; Birch et al. 1992), (2) responses to the vasoactive hormone thrombin, (3) controlled elevations of [Ca2+]i produced by intracellular flash photolysis of caged InsP3 or caged Ca2+ (DM-nitrophen) to mimic the initial agonist-evoked Ca2+ spike, and (4) photolysis of caged Ca2+ to produce a maintained Ca2+ rise. These results show that during the initial InsP3-evoked release of Ca2+ from internal stores the Cm change is small, suggesting that initially there is little vesicular secretion. In contrast, a large Cm change, indicating extensive vesicular secretion, is seen when [Ca2+]i is elevated for longer, a situation that may arise during strong activation, e.g. by thrombin or by cell damage.

A preliminary account of this work has been published (Smith et al. 1997; Carter et al. 1997).

METHODS

Tissue culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated and grown as previously described (Hallam et al. 1988). Primary isolates of HUVECs in medium M199 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 10% newborn calf serum were seeded onto 35 mm diameter glass or quartz coverslips and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air-5%CO2. Cells were used 24–72 h after isolation. Experiments were carried out in a Hepes-buffered physiological saline solution containing (mM): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 10 Hepes (pH 7.4) at room temperature (25–28°C).

Assay of vWf secretion

HUVEC cultures were grown to confluence in 24-well tissue culture trays. Cells were washed twice with serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; pH 7.4) containing 20 mM Hepes prior to addition of DMEM (control) or DMEM containing thrombin 1.0 U ml−1. The supernatant fraction was removed 10 min later and the release of vWf measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (Wheeler-Jones et al. 1996b). The mouse monoclonal anti-vWf coating antibody (CLBRAg35) was a gift from Dr A. J. Van Mourik (Central Blood Laboratory, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Fluorescence measurements and flash photolysis

Changes in cytosolic free [Ca2+] were measured with furaptra as previously described (Konishi et al. 1991; Ogden et al. 1995). Furaptra free acid (500 μM) was introduced into the cell together with caged compounds (DM-nitrophen or caged InsP3) by diffusion from a patch pipette during whole-cell recording. Diffusional equilibration between pipette solution and cell was determined from the fluorescence record. Microspectrofluorimetry was performed with a Nikon TMD microscope with a × 40, 1.3 NA objective lens. Excitation (400–440 nm) was from a 100 W quartz halogen lamp, and light emitted from a single cell viewed via long-pass filters at > 470 nm. Emitted light was detected by a photomultiplier operated in photon counting mode. Photon counts were converted to an analog signal by an integrating amplifier with correction for missed counts (Cairn Research, Faversham, Kent, UK), stored on FM tape and digitized at 100 Hz (CED1401, Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) and then stored on an AT bus computer. The method for converting the fluorescence change to free [Ca2+] has been described in detail previously (Ogden et al. 1995; see Konishi et al. 1991). Briefly, furaptra fluorescence with 400–440 nm excitation is quenched at high [Ca2+], and therefore the intrinsic fluorescence recorded before whole-cell recording is the fluorescence at saturating free [Ca2+], FCa,max. The free [Ca2+]i in HUVECs has been estimated as ∼0.1 μM (Hallam et al. 1988). The Ca2+ dissociation constant, K, for furaptra was assumed to be the in vitro value of 48 μM (Ogden et al. 1995; see also Konishi et al. 1991); therefore, the fluorescence of furaptra under resting conditions can be taken as an estimate of FCa,min. The free [Ca2+], Caf, was calculated from the fluorescence, F, by means of the relation:

| (1) |

Photolysis of DM-nitrophen or caged InsP3, the P-5 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl ester of InsP3 (kindly provided by Dr D. R. Trentham, NIMR, Mill Hill, London), was by a 1 ms pulse of near-UV light (280–360 nm with a Schott UG11 filter) from a short arc xenon flashlamp (Cairn Research) focused to produce an image of the arc 3–4 mm across at the cell as described previously (Ogden et al. 1990). The output of the lamp was fully adjustable up to 270 J, a range producing 0–30% photolysis of caged InsP3. Photolysis of caged InsP3 in the experimental microsope was calibrated by HPLC analysis of 5 μl droplets of 1 mM caged ATP irradiated at the experimental lamp intensities. Caged ATP and caged InsP3 have similar quantum yields and extinctions in the near-UV and therefore the same conversion (Walker et al. 1989; Ogden et al. 1990). Photolysis of the caged compounds by fluorescence excitation was minimized by shuttering the excitation when not recording.

Electrophysiological recording

The whole-cell patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981) was used for electrical recording and to introduce Ca2+ buffers, or furaptra and caged compounds into the cytosol of single HUVECs. Normal internal solution contained (mM): 153 potassium gluconate, 8 Hepes, 3 MgSO4, 3 Na2ATP (pH 7.2). The cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −50 mV and current was recorded with a patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments Axopatch 200A). Recordings were made with pipettes of resistance 1.5–6 MΩ, and access conductances in whole-cell recording were between 90 and 278 nS.

Cm measurement

The two-phase lock-in amplifier was constructed to the circuit described by Lindau & Neher (1988), and the whole-cell Cm calculated from the output as described by Lindau & Neher (1988). The zero phase angle of the lock-in amplifier was initially adjusted with patch-clamp capacitance compensation switched off and an open circuit headstage until an addition of fast capacitance compensation resulted in changes only in the imaginary output. The setting was then verified as described by Lindau & Neher (1988). Pipette capacitance was cancelled in cell-attached recording prior to membrane rupture. A sinusoidal voltage command of frequency 800 Hz and amplitude 2 mV peak to peak was applied. Membrane current and signals from the lock-in amplifier, corresponding to the real and imaginary components of whole-cell admittance, were low-pass filtered (30 Hz, 3 dB) and digitized at 100 Hz. Real time calculation of the passive cell parameters from equations given by Lindau & Neher (1988) used the programme CAP3 written by Dr John Dempster (University of Strathclyde, UK). The mean membrane potential, −40 mV (see Results), was taken as the reversal potential for membrane current when calculating the conductance. Traces of the cell capacitance (Cm), access conductance (Ga) and the combined leak and membrane conductance (Gm) were calculated on-line.

DiBrBAPTA-buffered Ca2+ solutions and DM-nitrophen solutions

5′,5′-Dibromo-BAPTA (DiBrBAPTA) stock was prepared in internal solution (10.78 mM; determined from absorbance at 263 nm (molar extinction coefficient ε263 for free anion = 2 × 104 M−1 cm−1; data from Molecular Probes). Solutions containing 5 mM DiBrBAPTA and Ca2+ were prepared to yield free [Ca2+] in the range 0.1–20 μM. The required free [Ca2+] was calculated from:

| (2) |

where Cat is total [Ca2+], Bt is total [DiBrBAPTA], Ka is 625000 μM−1 (Tsien, 1980) and Caf is free [Ca2+].

A stock of 147 mM DM-nitrophen (provided by Drs D. R. Trentham & G. Reid, NIMR, Mill Hill, London) was used to make Ca2+-loaded DM-nitrophen solutions. Internal solutions were prepared containing 4 mM DM-nitrophen, 3 mM Mg2+, 3 mM ATP, 500 μM furaptra and either 4 mM or 0 mM Ca2+. The two solutions were mixed to vary the DM-nitrophen:Cat ratio. The equilibrium free [Ca2+] and [Mg2+] for a given DM-nitrophen:Cat ratio were calculated using the Ca2+ and Mg2+ dissociation constants for DM-nitrophen (Ellis-Davies et al. 1996), ATP (Sillén & Martell, 1971) and furaptra (Konishi et al. 1991; Ogden et al. 1995). For 4 mM DM-nitrophen:2.4 mM Ca2+ these were Caf = 0.12 μM and Mgf = 12.2 μM, respectively (equilibrium Mg2+-ATP concentration 1.5 mM). Generally, the first pulse of UV light (at full output, 270 J) produced a transient elevation of free [Ca2+] that rose to a peak within the resolution of the fluorescence detection system (< 1 ms) and decayed with a half-time of ∼10 s back to resting levels. A second pulse generally produced an initial transient followed by a decline to a maintained elevated free [Ca2+]i, the magnitude of which could be varied by varying either the initial DM-nitrophen:Ca2+ ratio or (more usually) the energy of the second light pulse.

Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

Electrical properties of HUVECs; membrane potential, membrane conductance and Cm

Cells selected for recording were not connected by gap junctions to neighbouring cells, based both on a large physical separation and no transfer to neighbours of fluorescent indicator from the perfused cell, thus avoiding the electrical complications arising from cell-cell coupling (Carter & Ogden, 1994; Carter et al. 1996). The resting electrical parameters determined with whole-cell recording were as follows. The mean resting membrane potential was −40 ± 3 mV (range −19 to −65 mV, n = 20). The input conductance including leak in the pipette-membrane seal at the holding potential of −50 mV was 1.16 ± 0.14 nS (n = 50, range 0.04–4.62 nS). To optimize voltage clamp, small cells were visually identified and used for the Cm measurements. The initial Cm recorded had a mean of 23.8 ± 1.6 pF (n = 50, range 7.9–48.1 pF). In the same cells the access conductance was 144 ± 7 nS (n = 50, range 90–278 nS).

Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in HUVECs

Figure 1A shows the membrane currents, access conductances and Cm after establishing whole-cell recording in two HUVECs. With the pipette solution buffered to free [Ca2+] of 0.1 μM (left-hand panel), there was little change in Cm from the initial level of 16.0 pF. Cm increased slightly over 100 s from 16.0 to 16.2 pF and then declined to 15.1 pF over 500 s. In contrast, the cell shown in the right-hand panel, with 10 μM free [Ca2+] in the pipette, showed a continuous, mainly monotonic, increase of Cm over 500 s from the initial level of 16.5 to 23.1 pF. The time courses of Cm changes with buffered free [Ca2+]i in the range 0.1–20 μM applied by pipette perfusion are shown for six cells in Fig. 1B. The Cm change is normalized to the initial value after establishing whole-cell recording. At free [Ca2+]i levels of 0.1 and 1 μM there was little or no change in Cm; at 2 μM [Ca2+]i there was a monotonic increase in Cm, and at 5, 10 and 20 μM [Ca2+]i a more complex time course with initial slow change followed by a faster change for 20–50 s and finally a slower rise to reach a steady level after approximately 200 s. The increase in amplitude of the Cm (in pF) measured at 400–600 s close to or at a steady state, is plotted against free [Ca2+]i for 29 cells in Fig. 1C (n = 3–9 cells at each [Ca2+]i). No increase in Cm is seen at free [Ca2+]i of less than 1–2 μM, and at high free [Ca2+]iCm increases to a maximum averaging 4 pF above the initial level. The maximal increase in Cm at high [Ca2+]i represents an increase of ∼25–35% over the initial membrane area.

Figure 1. Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in HUVECs.

A shows continuous recordings of membrane current, Im (upper traces), access conductance, Ga (middle traces), and membrane capacitance, Cm (lower traces), in two separate HUVECs following establishment of whole-cell recording (arrow). The intracellular solution contained 0.1 μM (left panel) or 10 μM (right panel) free [Ca2+]. B shows the time course of Cm changes in six HUVECs at different free [Ca2+] ranging from 0.1 to 20 μM. The Cm is normalized to the initial Cm following establishment of whole-cell recording. C shows the maximal change in Cm plotted against the free [Ca2+] of the dialysing pipette solution (mean ±s.e.m., n = 3–9 cells at each [Ca2+]).

Changes in [Ca2+]i and Cm evoked by thrombin

Thrombin is a strong stimulant of vWf secretion from endothelium during coagulation. At 1.0 U ml−1, thrombin has been shown to produce strong or maximal secretion of stored mediators (e.g. Hamilton & Simms, 1987) and was used here to evoke capacitance changes associated with vesicular secretion. In cultures of HUVECs thrombin (1.0 U ml−1) stimulated release of vWf as shown by specific ELISA. Basal vWf release was 0.41 ± 0.13 mU ml−1 and in thrombin-stimulated cultures it was 0.93 ± 0.07 mU ml−1 (n = 4 wells). In single HUVECs, this concentration of thrombin has been reported to produce an initial rise in [Ca2+]i followed by a maintained elevated phase (e.g. Birch et al. 1994).

Thrombin was applied to single HUVECs with a puffer pipette placed approximately two cell diameters from the patch-clamped cell. Application of external solution alone produced no change in [Ca2+]i or Cm. Application of thrombin caused a large initial rise in intracellular free [Ca2+] to 7.1 ± 1.5 μM (range 2.4–11.4 μM, n = 5) (Fig. 2). Following the initial rise, [Ca2+]i declined in three of five cells tested to a sustained level of 2.0 ± 0.8 μM (n = 3, range 1.0–3.6 μM) (Fig. 2A). In the remaining two cells, [Ca2+]i returned to pre-stimulus levels despite the continued presence of thrombin (e.g. Fig. 2B). In the two cells with no prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i, the Cm comprised either no change (one cell), or a small slow increase of ∼0.1–0.2 pF following the initial [Ca2+]i rise which then declined back to pre-stimulus levels over 3–4 min (e.g. Fig. 2B). In contrast, the three cells with a sustained elevated [Ca2+]i had large increases in Cm (1.14 ± 0.12 pF, n = 3) with a more complex time course (Fig. 2A). After removal of thrombin, [Ca2+]i declined to resting levels and Cm decreased more slowly to pre-stimulus levels.

Figure 2. Effect of thrombin on [Ca2+]i and Cm in single HUVEC.

A and B, thrombin-evoked changes of [Ca2+]i (upper records) and Cm (lower records) in two HUVECs. The Cm prior to application of thrombin is indicated by the dashed line. Thrombin (1.0 U ml−1) was applied during the period indicated by the bar. The cells were voltage clamped at −50 mV and the external medium contained 1.8 mM Ca2+ in both cases.

Flash photolysis of caged InsP3 or DM-nitrophen

Thrombin-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i comprise two components, identified by their sensitivity to removal of external Ca2+: an initial spike insensitive to external Ca2+ followed by a Ca2+-sensitive maintained elevation of [Ca2+]i (Hamilton & Simms, 1987; Hallam et al. 1988). To determine how the size and duration of the change in Cm evoked by thrombin were related to the amplitude and time course of the [Ca2+]i elevation, Cm was monitored during a [Ca2+]i spike and during maintained intracellular [Ca2+]i. Both were produced by flash photolysis of caged InsP3 or DM-nitrophen and were made to simulate the [Ca2+] increase during the two components of the thrombin-evoked response. Control experiments with no cage present or caged phosphate (150 μM) showed that brief UV irradiation with the flash lamp pulse or release of the photolysis byproducts had no effect on [Ca2+]i or Cm.

Transient elevation of [Ca2+]i evoked by flash photolysis of caged InsP3 or DM-nitrophen

The small, slowly rising increase in Cm seen with transient elevations of [Ca2+]i during the early phase of the response produced by thrombin suggests that vesicular secretion may be small during short-lived high [Ca2+]i but greater when [Ca2+]i is maintained. To test this hypothesis, Cm was monitored during elevation of [Ca2+]i by flash photolysis of either caged InsP3 or DM-nitrophen under conditions when both compounds produce a short-lived spike of [Ca2+]i in the range of peak [Ca2+]i produced by thrombin (or other agonists) in endothelium of large vessels (∼1–30 μM; Carter & Ogden, 1994; Carter et al. 1996). Only the change in Cm resulting from the first flash in each cell is shown here because evidence given below suggests that on second and subsequent flashes the increase in Cm is affected by the initial elevation of [Ca2+]i. Figure 3A shows the change in Cm evoked by transient changes in [Ca2+]i resulting from flash photolysis of caged InsP3 (left-hand records; InsP3 concentrations indicated) or DM-nitrophen (right-hand records; 4 mM DM-nitrophen-2.4 mM Ca2+). The photolytically induced Ca2+ spikes had amplitudes and half-durations (approximately 10–20 s) similar to the initial Ca2+ spike evoked hormonally (cf. Fig. 2; Carter & Ogden, 1994; Carter et al. 1996). Small brief increases in [Ca2+]i (5–10 μM; upper records) produced by low intensity light pulses evoked little change, < 0.1 pF, in Cm. At higher light intensities, larger increases in [Ca2+]i (10–30 μM), whether due to photolysis of caged InsP3 (left-hand records) or Ca2+-loaded DM-nitrophen (right-hand records), produced small, slow increases of Cm, up to 0.6 pF, with rates of up to ∼4 fF s−1, that recovered to pre-flash levels over 2–3 min. The results are summarized in Fig. 3B where the peak increase in Cm and the rate of increase of Cm, measured as the maximum slope, are plotted against peak [Ca2+]i. There was a significant correlation between the amplitude or rate of change of Cm with peak [Ca2+]i (see figure legend). The results show only small slowly increasing Cm at peak [Ca2+] of 10–30 μM, suggesting that the pool of vesicles available for very rapid secretion is small.

Figure 3. Cm changes evoked by transient elevations of [Ca2+]i produced by photolysis of caged InsP3 or DM-nitrophen.

A shows changes in [Ca2+]i (upper records of pairs) and Cm (lower records of pairs) in four separate HUVECs following intracellular photolytic release (at times indicated by arrows) of InsP3 (left) or Ca2+ from DM-nitrophen (DMN; right). Cells were pre-equilibrated with internal solutions containing either 50 μM caged InsP3 or 4 mM DM-nitrophen-2.4 mM Ca2+ and 500 μM furaptra. The extent of photolysis was controlled by varying the light intensity of the UV pulse to give smaller (upper records) or larger (lower records) increases in [Ca2+]i. The Cm prior to photolysis is indicated by the dashed line. B summarizes the extent (left panel) and rate of change (right panel) of Cmversus peak [Ca2+]i produced by photolysis of caged InsP3 (⋆) or DM-nitrophen (•) in individual HUVECs. Regression analysis of the data in B gave correlation coefficients (r) of 0.7 (P < 0.001; left panel) and 0.49 (P < 0.03; right panel).

Cm changes resulting from large prolonged elevations of [Ca2+]i

Large Cm changes were seen during prolonged Ca2+ elevation by thrombin and at high buffered [Ca2+]i (Figs 1A and 2A). This suggests that high [Ca2+]i must be maintained for long periods to evoke large vesicular secretion. High levels of [Ca2+]i in the range seen here during thrombin activation are known to drive vWF secretion in permeabilized endothelial cells (e.g. Scrutton & Pearson, 1989). To test this idea, prolonged elevations of [Ca2+] were established rapidly by high-intensity photolysis of DM-nitrophen. In some experiments a prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i was generated with the first flash, in other experiments by a second high intensity flash ∼5 min after an initial low intensity flash. The data are distinguished as open circles (first flash) and filled circles (second flash) in Fig. 4B. Illustrative traces of [Ca2+]i and Cm are shown in Fig. 4A for three cells with differing steady free [Ca2+] levels produced by photolysis. Data from 16 cells are summarized in Fig. 4B. Comparison of the rate of increase of Cm for similar steady-state [Ca2+]i levels (2–5 μM) produced by a first or a second flash showed a larger change on the second flash. This difference indicates that there may be a priming effect of the first flash. Figure 4B also shows that when [Ca2+]i was maintained at levels greater than ∼3–4 μM the maximum rate of increase of Cm (lower graph) and the steady amplitude (upper graph) both increased to levels much greater than those seen with transient elevations of [Ca2+]i (cf. Fig. 3). This result is similar to that for perfusion of buffered Ca2+ (Fig. 1) but in this case it is clear that the rise in Cm was not slowed by equilibration of [Ca2+]i by perfusion into the cytosol. The changes in Cm seen with prolonged high [Ca2+]i stimulation are very large, up to 4 pF in Fig. 4B, equivalent to ∼30% of the initial Cm, and similar to those changes seen in the cell perfusion experiments of Fig. 1C (of up to 7 pF). Furthermore, the rates of increase in Cm evoked by high sustained [Ca2+] are large compared with those seen in response to transient elevations of [Ca2+]i, (up to 50 fF s−1 in Fig. 4B compared with 4 fF s−1 in Fig. 3B).

Figure 4. Capacitance changes in response to maintained elevations of [Ca2+]i produced by photolysis (arrows) of DM-nitrophen.

A shows the changes in capacitance (lower record of each pair) produced by different steady free [Ca2+] levels (upper traces of each pair) in three different cells. The Cm prior to photolysis is indicated by the dashed line. B summarizes the extent (upper panel) and rate of change (lower panel) of capacitance versus steady free [Ca2+] levels produced by photolysis of DM-nitrophen in individual HUVECs. ○, prolonged Ca2+ elevation produced by a first flash; •, prolonged Ca2+ elevation produced by a second flash. Regression analysis of the data in B gave correlation coefficients (r) of 0.86 (P < 0.001; upper panel) and 0.53 (P < 0.001, lower panel).

DISCUSSION

Vesicular secretion of vasoactive mediators was monitored in single endothelial cells by detecting changes in membrane capacitance and was used to study the mechanisms underlying regulated secretion. In many cell types an increase in [Ca2+]i provides a trigger for secretion (reviewed in Burgoyne & Morgan, 1993). In this study, the [Ca2+]i of single isolated endothelial cells was manipulated by intracellular perfusion with buffered [Ca2+]i, by hormonal stimulation with thrombin, or by flash photolysis of caged InsP3 or Ca2+-loaded DM-nitrophen.

Intracellular perfusion of endothelial cells with buffered [Ca2+]i in the range corresponding to resting [Ca2+]i (100 nM) evoked little or no change of Cm over many minutes of recording, indicating that exocytosis and endocytosis under resting conditions were occurring at approximately equal rates. At high [Ca2+]i, corresponding to the range that triggers vWF secretion (0.5–20 μM [Ca2+]; Scrutton & Pearson, 1989; Birch et al. 1992; Frearson et al. 1995), large net increases in Cm of up to 30% of resting Cm were seen. The time course of the changes in Cm were complex at [Ca2+]i > 2 μM (e.g. Fig. 1B), and difficult to interpret. First, during intracellular perfusion the free [Ca2+]i equilibrates slowly over a period of up to 90 s, during which time secretory granules experience a continually changing [Ca2+]i. Second, endothelial cells contain different secretory granules for t-PA, TFPI, Protein S and vWF, each of which may have different sensitivities to Ca2+. Biochemical studies in cell cultures have shown that the time course of pro-coagulant vWf secretion differs from that of the anti-coagulants TFPI, t-PA and Protein S. Secretion of TFPI, t-PA and Protein S occurs early (peaking in 30–60 s) but declines to low levels within 2–3 min (Stern et al. 1986; Kooistra et al. 1994; Lupu et al. 1995) and might be expected to produce an early transient increase in Cm. Indeed, TFPI storage granules have been identified in clusters at plasma membrane caveolae, suggesting that they may be available for early release (Lupu et al. 1995). On the other hand, the large vWF storage granules are generally sequestered further from the plasma membrane (Weibel & Palade, 1964), which may account in part for their much slower time course of secretion, detected ∼1–3 min after stimulation (Hamilton & Simms, 1987; Hattori et al. 1989; Frearson et al. 1995). Unlike the secretion of anti-coagulants, vWF secretion can be maintained for long periods in the continued presence of a stimulus, and might be expected to produce a delayed, larger and more maintained change in Cm, similar to those described here for free [Ca2+]i buffered to > 2 μM. Similar data have been obtained in neutrophils, which like endothelial cells contain several distinct granule populations that can undergo regulated secretion during specific phases of neutrophil activation (Nuesse et al. 1998). In that study, it was argued that the early smaller component and the delayed larger component of the change in Cm seen at higher [Ca2+]i reflects release of distinct granule populations with different Ca2+ affinities. Further work is needed to determine if the time course of changes in Cm seen here reflects secretion from different pools of granules.

Thrombin is generated at high levels at wound sites during blood coagulation and is a strong secretogogue for vWF, t-PA and TFPI from endothelial cells (Hamilton & Simms 1987; Lupu et al. 1995; van den Eijnden-Schrauwen et al. 1997). The predominant [Ca2+]i response in single intact HUVECs at high thrombin concentrations (1.0 U ml−1) consists of a biphasic elevation, an initial release of Ca2+ from internal stores followed by a maintained elevated component due to Ca2+ influx (Birch et al. 1994). In single patch-clamped cells, thrombin at 1.0 U ml−1 produced a biphasic elevation of [Ca2+]i, and a large maintained Cm increase (Fig. 2A). In two cells there was only a transient increase in [Ca2+]i and in these cells the change in Cm was slow and small (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained when [Ca2+]i was increased in a controlled manner either as a maintained elevation or as a transient spike, by flash photolysis of caged InsP3 or DM-nitrophen. The amplitude of the [Ca2+]i spike produced by photolysis (∼1–30 μM) was in the physiological range since similar large-amplitude Ca2+ transients are evoked by thrombin or other agonists in endothelial cells in culture and in situ (Carter & Ogden, 1994; Carter et al. 1996). The similar rates and extent of changes in Cm following transient elevations of [Ca2+]i evoked by photolysis of caged InsP3 (where Ca2+ release occurs over 50–100 ms) or DM-nitrophen (where Ca2+ is released in less than 1 ms; Kaplan & Ellis-Davies, 1988) suggest that secretion may not be triggered by the rate of rise of [Ca2+]i, as has been suggested for presynaptic transmitter release (Hsu et al. 1996).

Studies based on kinetic analysis of changes in Cm during controlled changes in [Ca2+]i by flash photolysis in chromaffin cells and melanotrophs have led to the idea that secretory granules proceed through a number of stages prior to exocytosis (see Henkel & Almers, 1996). Following a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i, the most advanced (docked) granules are secreted rapidly, while those at preceding stages are secreted more slowly. The small slow (up to 5 fF s−1) increases in Cm seen here following a transient elevation of [Ca2+]i suggest that in endothelial cells the pool of vesicles available for rapid secretion is small. Similar conclusions have been reached for other cells in which little secretion is seen during an initial agonist-evoked Ca2+ spike (Tse et al. 1993, Tse et al. 1997; Kim et al. 1997). The large component of secretion requires a more prolonged exposure to high [Ca2+]i, the slow time course of the changes in Cm indicating a slow recruitment of secretory vesicles into a releasable pool. The results presented in Fig. 4B suggest that exposure to high [Ca2+]i several minutes prior to a second prolonged Ca2+ rise may have a priming effect on secretion which persists during the relatively long interval between first and second flashes (∼5 min). Similar observations have been reported in neurohypophysial nerve terminals and in other systems (see Seward et al. 1995). This priming effect may underlie the delay before the high secretion rate seen during dialysis with solutions buffered to high [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1). In summary, to produce a high level of secretion, such as that seen with thrombin stimulation (Fig. 2A) it may be necessary to have a slow step that can be primed and a prolonged high elevation of [Ca2+]i.

There is considerable evidence that secretion of vWf, t-PA, TFPI and Protein S is triggered by an increase in [Ca2+]i (Stern et al. 1986; Hamilton & Simms, 1987; Scrutton & Pearson, 1989; Birch et al. 1992, 1994; Kooistra et al. 1994; Frearson et al. 1995; Emeis et al. 1997; van den Eijnden-Schrauwen et al. 1997) and that this may be mediated via calmodulin (Birch et al. 1992; van den Eijnden-Schrauwen et al. 1997). In mast cells, the recruitment of secretory vesicles is thought to be due to a slow Ca2+-dependent activation of protein kinase C (PKC), the most important factor being the amplitude rather than the pattern of the Ca2+ rise in this process (Kim et al. 1997). However, there is little evidence that other signalling pathways, including the PKC pathway, play an important role in triggering secretion in endothelial cells (Carew et al. 1992; Kooistra et al. 1994; Wheeler-Jones et al. 1996a,b; van den Eijnden-Schrauwen et al. 1997). Exocytosis in all cells requires several well-defined proteins (Hanson et al. 1997). A number of these proteins, required for vesicle trafficking and fusion in neurons and exocrine cells, are now known to be present in endothelial cells (e.g. VAMP-2, cellubrevin, NSF, SNAP, annexins and trimeric and monomeric GTPases; Schnitzer et al. 1995). Although some have been implicated in membrane retrieval and transcytosis, their role in regulated vesicular secretion has not yet been determined.

The maximum rate of change of Cm, during secretion in HUVECs, of 50 fF s−1 is much less than that seen in pituitary melanotrophs (5 pF s−1; Thomas et al. 1993), adrenal chromaffin cells (0.5–1 pF s−1; Neher & Zucker, 1993) or gonadotrophs (50–300 fF s−1; Tse et al. 1993). However, vWf release is sustained at a high rate for minutes rather than the milliseconds to seconds seen in neuroendocrine cells. Following a large increase in Cm evoked by thrombin the recovery by endocytosis of Cm to the initial level is slower than the recovery of [Ca2+]i and occurs at 1–5 fF s−1 (see Fig. 2A), a rate similar to the compensatory rate of endocytosis seen in chromaffin cells (Smith & Neher, 1997).

Local hormones (e.g. ATP, ADP, kinins or thrombin), generated at high concentrations close to or at a wound site, are likely to produce a prolonged rise in endothelial [Ca2+]i as seen here. A maintained elevated [Ca2+]i under these conditions may be important for strong secretion, particularly of vWF, by endothelial cells at wound sites. Further away agonist concentrations will be lower because of dilution and constitutive metabolic degradation by endothelial cells (see Mann, 1997). At low agonist concentrations endothelial cells generally respond with repetitive Ca2+ spikes (Jacob et al. 1988; Carter et al. 1991; Carter & Ogden 1994), and this might modify the pattern or extent of secretion. Recent studies suggest that Ca2+ spiking plays a central role in controlling cell processes such as mitochondrial metabolism (Pralong et al. 1994; Hajnoczky et al. 1996) and gene expression (Dolmetsch et al. 1998; Li et al. 1998). In some cells vesicular secretion is closely coupled to intracellular Ca2+ spikes or repetitive Ca2+ influx (Tse et al. 1993; Seward et al. 1995) while in others the amplitude rather than the specific pattern of Ca2+ elevation appears to be important (Kim et al. 1997). Indirect evidence suggests that Ca2+ spiking in endothelial cells may provide a mechanism for controlling secretion of the procoagulant molecule vWF. Secretion of vWF can be maintained for longer periods in the presence of an agonist and differs from t-PA and TFPI secretion which is temporally coupled to the early phase of agonist-evoked Ca2+ responses. Low agonist concentrations, which produce Ca2+ spiking in single endothelial cells, produce less vWF secretion than high agonist concentrations, which cause prolonged [Ca2+]i elevations (Birch et al. 1994). It seems likely that the priming effect seen in two-pulse experiments described above may have a role in potentiating vWF secretion during spiking. Current work is aimed at addressing the role of Ca2+ spiking in the control of secretion in single endothelial cells in culture.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation and Medical Research Council. T. D. C. holds a British Heart Foundation Gerry Turner Intermediate Research Fellowship. We thank Drs D. R. Trentham and G. Reid for providing the caged InsP3 and DM-nitrophen used in this study.

References

- Birch KA, Ewenstein BM, Golan DE, Pober JS. Prolonged peak elevations in cytoplasmic free calcium ions, derived from intracellular stores, correlate with the extent of thrombin-stimulated exocytosis in single human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Journal of Cell Physiology. 1994;160:545–554. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041600318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch KA, Pober JS, Zavoico GB, Means AR, Ewenstein BM. Calcium/calmodulin transduces thrombin-stimulated secretion: studies in intact and minimally permeabilised human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1992;118:1501–1510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.6.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Regulated secretion. Biochemical Journal. 1993;293:305–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2930305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carew MA, Paleolog EM, Pearson JD. The roles of protein kinase C and intracellular Ca2+ in the secretion of von Willebrand factor from human vascular endothelial cells. Biochemical Journal. 1992;286:631–635. doi: 10.1042/bj2860631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter TD, Bogle RG, Bjaaland T. Spiking of intracellular calcium ion concentration in single porcine cultured aortic endothelial cells stimulated with ATP or bradykinin. Biochemical Journal. 1991;278:697–704. doi: 10.1042/bj2780697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter TD, Chen XY, Carlile G, Kalapothakis E, Ogden DC, Evans WH. Porcine aortic endothelial gap junctions: characterization and permeation by caged InsP3. Journal of Cell Science. 1996;109:1765–1773. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter TD, Ogden DC. Acetylcholine-stimulated changes of membrane potential and intracellular Ca2+ concentration recorded in endothelial cells in situ in the isolated rat aorta. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;248:476–484. doi: 10.1007/BF00374568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter TD, Pearson JD. Regulation of prostacyclin synthesis in endothelial cells. News in Physiological Sciences. 1992;7:64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Carter TD, Zupancic G, Smith SM, Wheeler-Jones C. Calcium-dependent exocytosis in single patch-clamped human umbilical vein endothelial cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;504:206P. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.845ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature. 1998;392:933–936. doi: 10.1038/31960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Davies GCR, Kaplan JH, Barsotti JR. Laser photolysis of caged calcium: rates of calcium release by nitrophenyl-EGTA and DM-nitrophen. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:1006–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79644-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeis JJ, van der Eijnden-Schrauwen Y, van den Hoogen CM, de Priester W, Westmuckett A, Lupu F. An endothelial storage granule for tissue type plasminogen activator. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;139:245–256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frearson JA, Harrison P, Scrutton MC, Pearson JD. Differential regulation of von Willebrand factor exocytosis and prostacylin synthesis in electro-permeabilised endothelial cell monolayers. Biochemical Journal. 1995;309:473–479. doi: 10.1042/bj3090473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Seitz MB, Thomas AP. Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell. 1996;82:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam TJ, Pearson JD, Needham L. Thrombin-stimulated elevation of endothelial cell cytoplasmic free calcium concentration causes prostacyclin production. Biochemical Journal. 1988;257:243–249. doi: 10.1042/bj2510243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KK, Simms PJ. Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ associated with von Willebrand factor release in human endothelial cells exposed to histamine. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1987;79:600–608. doi: 10.1172/JCI112853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson PI, Heuser JE, Reinhard J. Neurotransmitter release - four years of SNARE complexes. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1997;7:310–315. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison VJ, Barnes K, Turner AJ, Wood E, Corder R, Vane JR. Identification of endothelin-1 and big endothelin-1 in secretory vesicles isolated from bovine aortic endothelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:6344–6348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori R, Hamilton KK, Fugates RD, McEver RP, Sims PJ. Stimulated secretion of endothelial von Willebrand factor is accompanied by rapid redistribution to the cell surface of the intracellular granule membrane protein GMP-140. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:7768–7771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel AW, Almers W. Fast steps in exocytosis and endocytosis studied by capacitance measurements in endocrine cells. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1996;6:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S-F, Augustine GJ, Jackson MB. Adaption of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis in presynaptic terminals. Neuron. 1996;17:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob R, Merritt JE, Hallam TJ, Rink TJ. Repetitive spikes of cytoplasmic Ca2+ evoked by histamine in human endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;335:40–45. doi: 10.1038/335040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JH, Ellis-Davies GCR. Photolabile chelators for rapid photolytic release of divalent cations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1988;85:6571–6575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TD, Eddlestone GT, Mahoud SF, Kutchtey J, Fewtrell C. Correlating Ca2+ responses and secretion in individual RBL-2H3 mucosal mast cells. Journal of Biological Science. 1997;272:31225–31229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M, Hollingworth S, Hawkins AB, Baylor SM. Myoplasmic Ca transients in intact frog skeletal muscle fibres monitored with the fluorescent indicator furaptra. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:271–302. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra T, Schrauwen Y, Arts J, Emeis JJ. Regulation of endothelial cell t-PA synthesis and release. International Journal of Hematology. 1994;59:233–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W-H, Llopis J, Whintney M, Zlokarnik G, Tsien RY. Cell-permeant caged InsP3 ester shows that Ca2+ spike frequency can optimise gene expression. Nature. 1998;392:936–941. doi: 10.1038/31965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau M, Neher E. Patch-clamp techniques for time-resolved capacitance measurements in single cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1988;411:137–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00582306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupu C, Lupu F, Dennehy U, Kakkar VV, Scully MF. Thrombin induces the redistribution of tissue factor pathway inhibitor from specific granules within human endothelial cells in culture. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 1995;15:2055–2062. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.11.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann KG. Thrombosis: theoretical considerations. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1997;65(suppl.):1657S–1664S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.5.1657S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Marty A. Discrete changes of cell membrane capacitance observed under conditions of enhanced secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1982;79:6712–6716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Zucker RS. Multiple calcium-dependent processes releated to secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1993;10:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90238-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuesse O, Serrander L, Lew DP, Krauser K-H. Ca2+-induced exocytosis in individual human neutrophils: high and low-affinity granule populations and submaximal responses. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:1279–1288. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden DC, Capiod T, Walker JW, Trentham DR. Kinetics of the conductance evoked by noradrenaline, inositol trisphosphate or Ca2+ in guinea-pig isolated hepatocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;422:585–602. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden D, Khodakhah K, Carter T, Thomas M, Capiod T. Analogue computation of transient changes of intracellular free calcium concentration with the low affinity Ca2+ indicator furaptra during whole cell patch clamp recording. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;49:587–591. doi: 10.1007/BF00704165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pralong W-F, Spat A, Wollheim CB. Dynamic pacing of cell metabolism by intracellular Ca2+ transients. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:27310–27314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seward SP, Chernevskaya NI, Nowycky MC. Exocytosis in peptidergic nerve terminals exhibits two calcium-sensitive phases during pulsatile calcium entry. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3390–3399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03390.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seward SP, Nowycky MC. Kinetics of stimulus-coupled secretion in dialyzed bovine chromaffin cells in response to trains of depolarizing pulses. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:553–562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer JA, Lui J, Oh P. Endothelial caveolae have the molecular transport machinery for vesicle budding, docking, and fusion including VAMP, NSF, SNAP, annexins, and GTPases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:14399–14404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrutton MC, Pearson JD. Ca2+-driven prostacyclin synthesis and von Willebrand factor secretion in electropermeabilised endothelial cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;97:420P. [Google Scholar]

- Sillén LG, Martell AE. Stability Constants, Special Publication. Supplement 1. Vol. 25. London: The Chemical Society; 1971. pp. 650–654. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Neher E. Multiple forms of endocytosis in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;139:885–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Zupancic G, Wheeler-Jones C, Bilhari D, Ogden D, Carter TD. Exocytosis is calcium dependent in single patch-clamped human umbilical vein endothelial cells. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997;155(suppl.):A783. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D, Brett J, Harris K, Nawroth P. Participation of endothelial cells in the Protein C-Protein S anticoagulant pathway: the synthesis and release of protein S. Journal of Cell Biology. 1986;102:1971–1978. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Wong JG, Lee AK, Almers W. A low affinity Ca2+ receptor controls the final steps in peptide secretion from pituitary melanotrophs. Neuron. 1993;11:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90274-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse A, Tse FW, Almers W, Hille B. Rhythmic exocytosis stimulated by GnRH-induced calcium oscillations in rat gonadotrophes. Science. 1997;260:82–84. doi: 10.1126/science.8385366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse FW, Tse A, Hille B, Horstmann H, Almers W. Local Ca release from internal stores controls exocytosis in pituitary gonadotrophes. Neuron. 1997;18:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY. New calcium indicators and buffers with high selectivity against magnesium and protons: Design, synthesis, and properties of prototype structures. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2396–2404. doi: 10.1021/bi00552a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Eijnden-Schrauwen, Atsma DE, Lupu F, de Vries REM, Kooistra T, Emeis JJ. Involvement of calcium and G proteins in the acute release of tissue-type plasminogen activator and von Willebrand factor from cultured human endothelial cells. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 1997;17:2177–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DD. Cell biology of von Willebrand factor. Annual Review of Cell Biology. 1990;6:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.001245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JW, Feeney J, Trentham DR. Photolabile precursors of inositol phosphates. Preparation and properties of 1(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl esters of myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3272–3280. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER, Palade GE. New cytoplasmic components in arterial endothelia. Journal of Cell Biology. 1964;23:101–112. doi: 10.1083/jcb.23.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler-Jones CPD, May MJ, Houliston RA, Pearson JD. Inhibition of map kinase kinase (MEK) blocks endothelial PGI2 release but has no effect on von Willebrand factor secretion or E-selectin expression. FEBS Letters. 1996a;388:180–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler-Jones CPD, May MJ, Morgan AJ, Pearson JD. Protein tyrosine kinases regulate agonist-stimulated prostacyclin release but not von Willebrand factor secretion from human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochemical Journal. 1996b;315:407–416. doi: 10.1042/bj3150407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]