Abstract

Intracellular voltage recordings were made from the somata of L6 and S1 dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurones at 28.5–31 °C in young guinea-pigs (150–300 g) anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone. Action potentials (APs) evoked by dorsal root stimulation were used to classify conduction velocities (CVs) as C, Aδ or Aα/β. Units with overshooting APs and membrane potentials (Vm) more negative than −40 mV were analysed: 40 C-, 45 Aδ- and 94 Aα/β-fibre units.

Sensory receptive properties were characterized as: (a) low-threshold mechanoreceptive (LTM) units (5 C-, 10 Aδ- and 57 Aα/β-fibre units); (b) nociceptive units, responding to noxious mechanical stimuli, some also to noxious heat (40 C-, 27 Aδ- and 27 Aα/β-fibre units); (c) unresponsive units that failed to respond to a variety of tests; and (d) C-fibre cooling-sensitive units (n = 4). LTM units made up about 8 % of identified C-fibre units, 36 % of identified Aδ-fibre units and > 73 % of identified Aα/β-fibre units. Compared with LTM units, the nociceptive units had APs that were longer on average by 3 times (C-fibre units), 1.7 times (Aδ-fibre units) and 1.4 times (Aα/β-fibre units). They also had significantly longer rise times (RTs) and fall times (FTs) in all CV ranges. Between Aα/β-nociceptors and Aα/β-LTMs there was a proportionately greater difference in RT than in FT. The duration of the afterhyperpolarization measured to 80 % recovery (AHP80) was also significantly longer in nociceptive than LTM neurones in all CV ranges: by 3 times (C-fibre units), 6.3 times (Aδ-fibre units) and 3.6 times (Aα/β-fibre units). The mean values of these variables in unresponsive units were similar to those of nociceptive units in each CV range; in C- and Aδ-fibre groups their mean AHP duration was even longer than in nociceptive units.

A-fibre LTM neurones were divided into Aδ- (D hair units, n = 8), and Aα/β- (G hair/field units, n = 22; T (tylotrich) hair units, n = 6; rapidly adapting (RA) glabrous units, n = 6; slowly adapting (SA) hairy and glabrous units, n = 2; and muscle spindle (MS) units n = 17). MS and SA units had the shortest duration APs, FTs and AHP80s of all these groups. The mean RT in D hair units was significantly longer than in all Aα/β LTM units combined. T hair units had the longest mean FT and AHP of all the A-LTM groups. The mean AHP was about 10 times longer in T hair units than in all other A-LTM units combined (significant), and was similar to that of A-fibre nociceptive neurones.

These differences in somatic AP shape may aid in distinguishing between LTM and nociceptive or unresponsive C- and Aδ-fibre units but probably not between nociceptive and unresponsive units. The differences seen may reflect differences in expression or activation of different types of ion channel.

This paper examines the relationship of action potential (AP) and afterhyperpolarization (AHP) configurations to the sensory receptive properties of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurones in vivo. There have been few studies of this relationship, and although somatic AP and AHP configurations have been shown to differ in low-threshold mechanoreceptive (LTM) and nociceptive A-fibre neuronal somata (see below), no such differences have previously been demonstrated in any species for C-fibre units. In addition, no comparisons of these configurations between different types of LTM neurones have previously been published. In A-fibre units it has been reported that the AP and AHP configurations are more closely related to the nociceptive versus LTM properties than to the conduction velocity (CV) of the fibres. In both cat (Rose et al. 1986; Koerber et al. 1988) and rat (Ritter & Mendell, 1992), high-threshold mechanoreceptive (HTM) cells with A-fibres had spikes with longer AP and AHP durations than low-threshold mechanoreceptive (LTM) A-fibre units. HTM cells with C-fibres had an inflection on the falling phase of their somatic AP (Cameron et al. 1986; Rose et al. 1986). In the only report on LTM C-fibre neurones to date, Traub & Mendell (1988) reported broad somatic spikes in both nociceptive and LTM C-fibre neurones. Thus it appeared that, in the cat, the correlation between the receptor type and somatic spike shape did not hold for cells with C-fibres. Whether this was also the case for other species was unknown.

The aims of the present experiments, therefore, were: (1) to confirm the association of configuration of somatic spikes with nociceptive/LTM peripheral receptor type in the guinea-pig; (2) to examine nociceptive and LTM C-fibre neurones in a species other than cat; (3) to study whether there is a correlation of somatic spike configuration with subdivisions of LTM neurones defined by their sensory receptive properties; (4) to determine the correlation between AP and AHP durations in neurones with different sensory receptive properties. Guinea-pigs were chosen for this study because it is easier to make more consistent intracellular recordings from C-fibre neurones than in, for example, the rat (Lawson et al. 1997). Some of the preliminary data have been published in abstract form (Djouhri et al. 1997).

METHODS

Experiments were carried out on young guinea-pigs (weight 150–300 g) that were deeply anaesthetized initially with sodium pentobarbitone (50 mg kg−1i.p.). Experimental procedures complied throughout with Home Office guidelines. The fur on the left hindlimb was clipped to a few millimeters to allow individual hairs to be moved. The animals were then tracheotomized to allow artificial ventilation and continuous monitoring of end-tidal CO2. The left carotid artery was cannulated to permit i.v. injections of additional doses (10 mg kg−1) of the anaesthetic as necessary to maintain areflexia, tested regularly by pinching of the forepaw. The core temperature was maintained at 36°C. All animals were paralysed just prior to electrophysiological recording with gallamine triethiodide (Flaxedil) (2 mg kg−1i.v.) administered via the arterial cannula accompanied by an additional dose (10 mg kg−1, i.v.) of the anaesthetic. Further Flaxedil (2 mg kg−1) was given at regular intervals, always accompanied by further anaesthetic (10 mg kg−1). The frequency and amount of anaesthetic administered during the paralysis was determined by that required to maintain complete areflexia in the 2 h prior to administering the Flaxedil. The vertebral column was stabilized with rigid support of the ilium and a clamp on the L1 vertebra. A laminectomy was performed from L2 to S2 to expose the L6 and S1 dorsal root ganglia. Dental impression material was used to construct a large paraffin pool to protect the exposed ganglia and spinal tissue. A small silver platform was placed beneath the DRG being studied to stabilize it during recording. The adipose tissue over the DRG was removed with care not to disturb the DRG surface or to damage the surface blood vessels. The dura mater over the spinal cord was opened and the dorsal root of the ganglion was sectioned close to its entry to the spinal cord and placed over a pair of bipolar platinum electrodes. Initially this pair of electrodes was used for recording to establish the receptive region of the dorsal root to natural stimulation and subsequently it was used to stimulate the root during intracellular recordings. The paraffin pool was maintained at 28.5–31°C.

Intracellular recordings

Intracellular recordings from DRG somata were made with glass micropipettes filled with 1 m KCl (60–120 MΩ) or fluorescent dye, either Lucifer Yellow CH in 0.1 m LiCl (200–500 MΩ) or ethidium bromide in 1 m KCl (80–140 MΩ). The electrodes and amplifier were tested with square voltage pulses and had response times of < 0.025 ms. The microelectrode was advanced in 1 μm steps by a microdrive until a membrane potential (Vm) was seen and an AP could be evoked by stimulation of the dorsal root with single rectangular pulses with durations of 0.03 ms (for A-fibre units) or 0.3 ms (for C-fibre units). The stimulus intensity was then adjusted to twice threshold for A-fibre units and suprathreshold for C-fibre units, and APs were recorded on line with a CED (Cambridge Electronic Design) 1401 plus interface and the SIGAV program from CED and were subsequently analysed with the Spike II program (CED). A number of AP parameters were measured for each unit. These are illustrated in Fig. 1. The conduction velocity (CV) was estimated from the latency to the beginning of the rise of the antidromically evoked somatic AP and the conduction distance between the centre of the ganglion and the cathode. This was measured at the end of each experiment and was typically 4–7 mm. Utilization time was not taken into account.

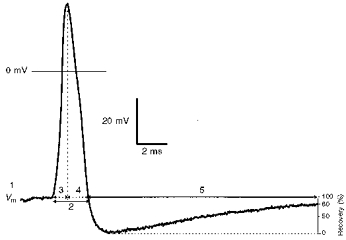

Figure 1. AP waveform to illustrate the variables measured.

An intracellularly recorded somatic AP of an Aα/β-fibre neurone evoked by electrical stimulation of the dorsal root showing the electrophysiological parameters measured. These were membrane potential (Vm) (1), AP duration at base (APdB) (2), AP rise time (RT) (3), AP fall time (FT) (4), and AHP duration to 80 % recovery (AHP80) (5).

Sensory receptive properties

The sensory receptive properties of afferent units identified by antidromic responses to dorsal root stimulation were examined with hand-held stimulators. Receptive fields were on the left hindlimb and flank. Identification of the sensory receptive properties of the recorded units were as described previously (see Lawson et al. 1997). Briefly, when A-fibre somata were penetrated, an attempt to characterize their receptive fields was made by lightly brushing the limb fur. Units that responded were further tested for skin contact and light pressure with blunt objects, light tap, tuning forks vibrating at 100 or 250 Hz and pressure with calibrated von Frey hairs. A-fibre units responding to these stimuli were categorized as low-threshold mechanoreceptive (A-LTM) units. Non-cutaneous units that often showed ongoing discharges, responded to light pressure against muscle tissue, and followed vibration of 100 or 250 Hz applied with a tuning fork were classified as muscle spindle (MS) afferent units. If the A-fibre unit did not respond to low intensity stimulation, then strong mechanical stimuli were applied with fine forceps, a sharp object (e.g. needle) or coarse toothed forceps. A-fibre units responding to these stimuli and having punctate receptive fields (usually) were classified as A-fibre high-threshold mechanoreceptive (A-HTM) units. A-fibre units were classified as A-fibre mechano-heat (A-MH) units when they responded not only to noxious mechanical stimuli but also promptly to a single application of noxious heat (hot water at 60–70°C or heated brass rod). The term ‘A-nociceptive unit’ as used in this paper includes A-HTM and A-MH units.

Similarly C-fibre units were tested with a variety of mechanical and thermal stimuli following the previously described procedures (see Lawson et al. 1997). C-fibre low-threshold mechanoreceptive (C-LTM) units responded to very gentle mechanical stimulation of the skin on initial testing and to cooling with a brief spray of ethyl chloride, a cooled metal rod or ice applied on the mechanically defined receptive field. C-fibre cells (C-cells) with receptive fields in the superficial cutaneous tissue that responded vigorously to both noxious heat and noxious mechanical stimuli were categorized as C-fibre polymodal (C-PM) units, whereas those that responded to these stimuli but had their receptive fields deep in the cutaneous or deep tissues were referred to as C-fibre mechano-heat (C-MH) units. C-fibre units that required strong mechanical stimuli of cutaneous tissue but lacked prompt responses to noxious heat were classified as C-fibre high threshold mechanoreceptive (C-HTM) units. The term ‘C-nociceptive unit’ (or C-nociceptor) is used throughout this paper to include C-HTM, C-MH and C-PM units.

Neurones with A- or C-fibres for which no receptive field was found despite an extensive search with the usual non-noxious and noxious mechanical and thermal stimuli, as well as with pressure on the abdomen, were called unresponsive units (see Discussion).

For all nociceptive units with C- or A-fibres, attempts were made to determine the tissue location (i.e. depth in the tissue) of their receptive fields. Units that responded to needle pressure, pinch with very fine forceps and lifting of the superficial tissue away from the underlying tissue with very fine forceps were classified as ‘superficial cutaneous’ and were thought to have receptive terminals in the epidermis or the very superficial dermis. Units were classified as ‘deep cutaneous’ if they did not respond to stimulation of the superficial layers of the skin and required manipulation of the soft dermal tissue. Units whose responses were evoked by squeezing or pressure to muscles, joints or deeper fascia were defined as ‘subcutaneous’. However, this classification was more difficult in units with receptive fields in the glabrous skin because it was difficult to distinguish between the thick epidermis and the thin dermis.

During some experiments the sample was biased towards nociceptive units by rejection of low-threshold Aα/β-fibre units (see Discussion). The relative incidence of different types of Aα/β-fibre unit does not therefore provide an accurate reflection of the real incidence.

Compound action potentials

In seven animals, monopolar compound action potential recordings were made from the ipsilateral S2 dorsal root with a platinum electrode. The stimulating electrodes (also platinum) were placed under the ipsilateral dorsal root very close to the S2 DRG. For better recordings, the dorsal root was electrically earthed between the stimulating and recording electrodes. The S2 root was used because of its slightly greater length and the necessity of inserting two pairs of electrodes beneath it. These recordings were made under the same conditions as those for intracellular recordings, i.e. at the same temperature range (28.5–31°C) in the paraffin pool and from animals of the same sex and weight range.

At the end of the experiment after injection of a further 20 mg kg−1 pentobarbitone to induce deep surgical anaesthesia the animal was perfused through the heart with normal saline followed by Zamboni's fixative.

Statistics

Cells were included in the analysis only if they met the following criteria. For A-fibre cells the Vm had to be more negative than −40 mV, all cells had to have overshooting APs and negative going AHPs. The rationale for the last criterion was to exclude recordings that may have been from within a fibre rather than in the soma since depolarizing afterpotentials have been associated with intracellular recordings in fibres (Stampfli & Hille, 1976; Harper & Lawson, 1985). For C-fibre cells, the initial criteria were the same as for A-fibre cells (Vm and overshooting APs), although cells without hyperpolarizing AHPs were also included, there being little chance of recordings being made within a C-fibre. However, because of the small number of C-LTM units that fell within these criteria, the analyses were repeated including C-fibre units which displayed AP overshoots but which had Vm values between −30 and −40 mV. The results for both sets of C-fibre data (−40 mV group and −30 mV group) are presented in the tables and figures.

Multiple comparisons of each variable shown in Tables 1 and 2 and Figs 4 and 5 were made within each CV range with the Kruskall-Wallis test, a non-parametric test that compares the medians of three or more unpaired groups. This was chosen instead of the parametric one-way ANOVA test because the values for certain variables were not normally distributed. Where the overall value of P was < 0.05, Dunn's post hoc test (Glantz, 1992) was carried out on each pair of groups. All tests were made using Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). Results of Dunn's post hoc test are shown on Tables 1 and 2 and on Figs 4–7. Mean data are shown in the Tables, whereas medians are indicated on the scatter graphs in Figs 4–7. Occasionally one group was compared against several other groups combined. For this the Mann-Whitney U test was used.

Table 1.

Comparison of properties of nociceptive and non-nociceptive DRG neurones

| CV range | Receptor class | n | Vm(mV) | CV (m s−1) | APdB (ms) | AP RT (ms) | AP FT(ms) | AHP80 (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OverallP | n.s. | n.s. | ** | ** | ** | * | ||

| Noci | 27 | 45 ± 4.6 | 0.41 ± 0.16 | 7.2 ± 3.8 ** | 2.5 ± 0.89 ** | 4.75 ± 3.3 ** | 14.4 ± 9.2 (22) | |

| C (−40 mV group) | LTM | 5 | 49.2 ± 6.4 | 0.63 ± 0.32 | 2.4 ± 0.82 | 1.04 ± 0.34 | 1.42 ± 0.49 | 4.84 ± 1.6 (3) |

| Cool | 4 | 47.8 ± 2.1 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 6.6 ± 0.43 * | 2.39 ± 1.07 | 4.2 ± 0.83 * | 12.1 ± 11.7 (4) | |

| Unresponsive | 4 | 44.7 ± 9 | 0.43 ± 0.24 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 0.37 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 32.1 ± 12.6 ** (4) | |

| Overall P | n.s. | * | *** | ** | *** | ** | ||

| Noci | 40 | 41.9 ± 6 | 0.40 ± 0.16 | 7.13 ± 3.9 *** | 2.53 ± 0.86 *** | 4.61 ± 3.5 *** | 20.3 ± 22.1 ** (32) | |

| C (−30 mV group) | LTM | 7 | 44.5 ± 9.5 | 0.7 ± 0.29 | 2.7 ± 0.87 | 1.14 ± 0.44 | 1.57 ± 0.47 | 4.6 ± 1.6 (5) |

| Cool | 6 | 42.7 ± 8.2 | 0.3 ± 0.04 * | 6.5 ± 0.32 ** | 2.36 ± 0.86 | 4.2 ± 0.74 ** | 12.3 ± 9.2 (6) | |

| Unresponsive | 7 | 41.1 ± 7.8 | 0.54 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 1.98 ± 0.41 | 2.95 ± 1.15 | 35.2 ± 31.9 ** (7) | |

| Overall P | n.s. | n.s. | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Noci | 27 | 50.8 ± 8.6 | 2.48 ± 0.88 | 3.0 ± 0.72 *** | 1.18 ± 0.31 *** | 1.9 ± 0.6 *** | 21.5 ± 16.6 *** | |

| Aδ | LTM | 8 | 52 ± 6.7 | 1.9 ± 0.61 | 1.76 ± 0.28 | 0.69 ± 0.094 | 1.07 ± 0.22 | 3.4 ± 1.4 |

| Unresponsive | 10 | 49.1 ± 5.9 | 2.3 ± 0.87 | 2.88 ± 0.65 * | 1.15 ± 0.18 ** | 1.75 ± 0.54 * | 56.2 ± 37 *** | |

| OverallP | n.s. | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | ||

| Noci | 27 | 51.0 ± 7.9 | 7.1 ± 2.2 *** | 1.94 ± 0.56 *** | 0.81 ± 0.33 *** | 1.13 ± 0.31 * | 20.0 ± 16.0 *** | |

| Aα/β | LTM | 57 | 52.5 ± 6.9 | 11.3 ± 4.5 | 1.35 ± 0.5 | 0.46 ± 0.13 | 0.89 ± 0.41 | 5.6 ± 10.1 |

| Unresponsive | 10 | 53.1 ± 8.5 | 5.5 ± 2.5 *** | 2.14 ± 0.89 ** | 0.82 ± 0.35 ** | 1.34 ± 0.58 * | 17.5 ± 17.0 ** |

Means ± s.d.are given for each variable. Abbreviations: AP, action potential; dB, duration at base; FT, fall time; FT, fall time; RT, rise time; AHP80, afterhyperpolarization duration to 80% recovery. The number of neurones (n) indicates the number of units for all columns except the last (AHP80) for the C-cells; here the numbers are indicated in parentheses. These numbers were lower in some cases because C-cells with no negative-going after-potential were included. The statistical test was the Kruskall-Wallis test (nonparametric), with Dunn's post hoc test between all the groups in one CV range, i.e. four groups were compared for C-fibre cells and three were compared for Aα/β- and Aδ-fibre cells. The overall significance (Overall P) for the Kruskall-Wallis test is shown at the top of each group of numbers. The significance between individual groups (Dunn's post hoc test) is expressed in each case between the group indicated and the LTM group in that CV range. This was possible because no significant differences were found between nociceptors (Noci) and unresponsive neurones, or between C-cooling cells (Cool) and unresponsive neurones. n.s., not significant

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001. The absence of asterisks indicates the absence of any significant difference (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of properties of subgroups of low-threshold mechanoreceptive A-fibre neurones

| CV range | Receptor class | n | Vm (mV) | CV (m s−1) | APdB (ms) | AP RT (ms) | AP FT (ms) | AHP80 (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall P | n.s. | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Aδ | D hair | 8 | 51.6 ± 6.7 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.76 ± 0.28*** | 0.69 ± 0.09*** | 1.1 ± 0.22** | 3.4 ± 1.4 |

| Aα/β | G hair/field | 22 | 51.5 ± 6.7 | 9.2 ± 3.4** | 1.55 ± 0.48*** | 0.53 ± 0.14* | 1.0 ± 0.37*** | 3.3 ± 1.5*]* |

| Aα/β | T hair | 6 | 52.4 ± 6.9 | 11.5 ± 2.4 | 1.75 ± 0.55** | 0.46 ± 0.17 | 1.29 ± 0.48*** | 30 ± 17.9***]* |

| Aα/β | SAI & SAII | 2 | 52.2, 61.1 | 15.4, 13.9 | 1.1, 0.7 | 0.33, 0.3 | 0.74, 0.4 | 1.4, 1.3 |

| Aα/β | RA | 6 | 55.5 ± 7.4 | 11.1 ± 1.7 | 1.54 ± 0.42* | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 1.1 ± 0.36 * | 3.6 ± 1.3 |

| Aα/β | MS | 17 | 52.2 ± 6.3 | 14 ± 5.5 | 0.93 ± 0.2 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.54 ± 0.14 | 1.9 ± 0.7 |

Means ± s.d. for variables are given except for the SA units, for which two individual values are given. For abbreviations see Table 1. Statistical tests for each variable were made between all the groups in the table excluding the SA units due to the small numbers. In addition it was inappropriate to include the D hair group in the CV analysis. The Kruskall-Wallis test (non-parametric) with Dunn's post test was used throughout. Note that four of the Aα/β-LTM units included in Table 1 are not included on this table since their subclassification was incomplete. Aα/β hair follicle afferents and field units were combined and called G hair/field units (see text). Except in one case indicated by the bracket joining the G hair/field and T hair groups, significant differences are between the muscle spindle (MS) and the group indicated by the asterisks

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001. The absence of asterisks indicates the absence of any significant difference.

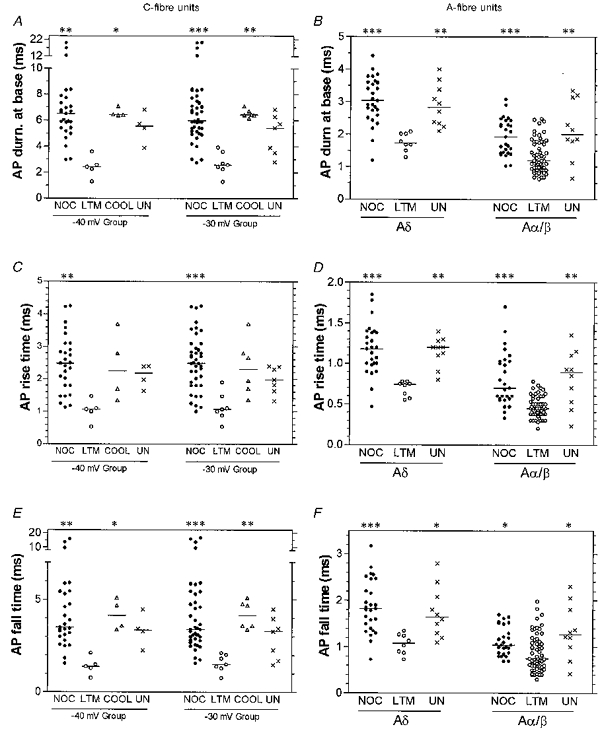

Figure 4. AP variables of C- and A-fibre nociceptive and other types of unit.

Scatterplots to show distributions of the variables with the median (horizontal line) superimposed in each case. For the C-fibre units, the data plotted on the left includes only cells with Vm more negative than −40 mV, and that on the right includes cells with Vm more negative than −30 mV. COOL (C-cells only), units that responded to cooling but had either no response or a weak response to mechanical stimulation; NOC, nociceptive units; UN, unresponsive units. Asterisks above the graph indicate the significant differences which in all cases were between that column and the LTM group, obtained using the Kruskall-Wallis test with Dunn's post hoc test, carried out between the four groups of C-cells, or between the three groups of Aδ- and Aα/β-cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The absence of asterisks indicates the absence of any significant difference.

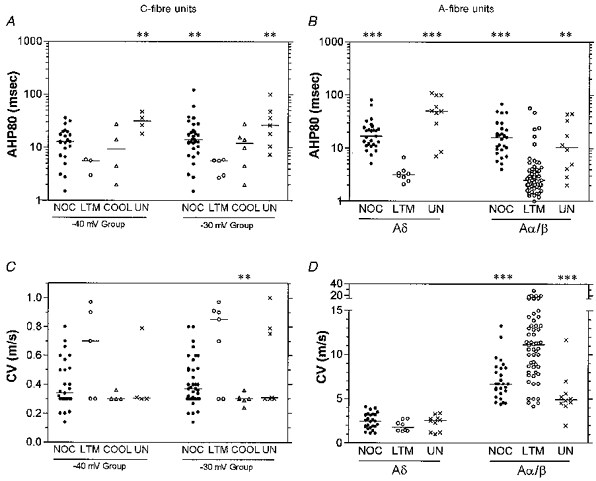

Figure 5. AHP80 and CV of C- and A-fibre nociceptive and other types of unit.

Scatter plots to show distributions of the variables with the median (horizontal line) superimposed in each case. Details as for Fig. 4. Asterisks above the graph indicate the significant differences which in all cases were between that column and the LTM group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The absence of asterisks indicates the absence of any significant difference.

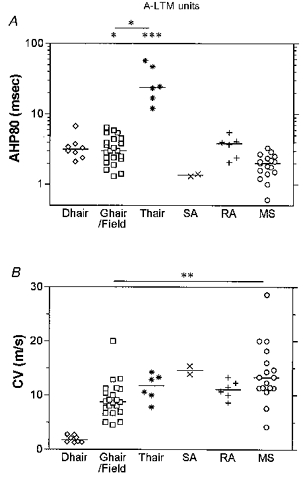

Figure 7. AHP80 and CV of A-LTM units with different sensory properties.

Scatter plots of distributions of variables, with the median (horizontal bar) superimposed in each case, grouped according to the sensory properties of the neurones. The D hair units had Aδ-fibre CVs, and all other groups had Aα/β-fibre CVs. Asterisks above the graph (in A) indicate a significant difference between the data in that column and the muscle spindle group, except (in A and B) where indicated by a line linking groups that are significantly different: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The absence of asterisks indicates the absence of any significant difference, but note that since there were only two SA units, this group was excluded from statistical tests.

RESULTS

A total of 179 DRG neurones met the criteria of overshooting AP and membrane potential (Vm) more negative than −40 mV. Analysis of C-fibre unit data was carried out firstly on units with Vm values of at least −40 mV (−40 mV group), and then on these same units with the addition of data from a further twenty C-fibre units with Vm values of between −30 and −40 mV (−30 mV group). Units were classified from their dorsal root CVs as C-, Aδ- or Aα/β-cells with C-cells conducting at < 1.1 m s−1, Aδ at 1.1–4.2 m s−1, and Aα/β at > 4.2 m s−1. This classification was based on recording compound APs from S2 dorsal roots of seven guinea-pigs with similar weights and equivalent paraffin pool temperatures to those used in the intracellullar recording experiments. The estimated mean CV for the Aδ-wave (using the conduction distance and the latency to the onset of the wave) was 4.2 ± 0.5 m s−1 (mean ±s.d., n = 7) and for the C-wave was 1.1 ± 0.04 m s−1 (n = 7).

The types of A-LTM units found in the present study included several types of afferents activated by hair movement. Hair follicle afferents were classified as Guard (G), Down (D) and Tylotrich (T) hair units. Some hair follicle afferent units were clearly G hair units and most were classified according to their adaptation properties as G1 or G2 (Burgess & Perl, 1967). Some field units were also well characterized. However, there was a group of incompletely classified units, possibly G hair units, that responded to hair movement but that might have been field units. Since there were no detectable electrophysiological differences between well-classified G hair and field units, these two groups and the above partially classified units were grouped together as G hair/field units. In addition hair units responding to movement of a (usually very long) hair at the border of hairy and glabrous skin on the feet or toes were called T hair units, following the classification of the long Tylotrich hairs in the rabbit and cat (see Brown & Iggo, 1967). D hair units conducted in the Aδ range and were extremely sensitive to slow hair movements, skin stretch and cooling. Other mechanosensitive units included slowly adapting type I and type II (SAI and SAII) receptors in both hairy and glabrous skin, rapidly adapting (RA) receptors in glabrous skin, muscle spindle (MS) afferents and cooling-sensitive (cooling) units. For each CV range the number of units within a receptor type (functional class) that fell within the acceptance criteria is given in Tables 1 and 2.

Examples of action potentials recorded from individual different receptor types are shown in Fig. 2. The range of variability of the AP durations and shapes for nociceptive and LTM neurones within the C- and Aδ-fibre ranges is shown in Fig. 3, where the APs are superimposed with their peaks aligned. It can be seen from this figure that neurones with different receptor properties exhibited different AP shapes and durations.

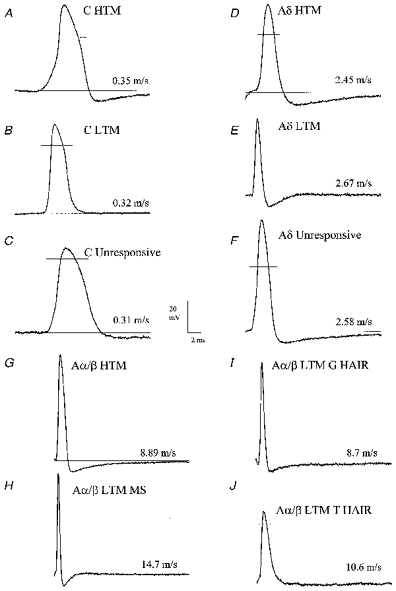

Figure 2. Examples of APs recorded from neurones with different sensory receptive properties.

Examples of somatic APs evoked by dorsal root stimulation and recorded intracellularly from neurones with different receptor properties: C-fibres (A-C), Aδ-fibres (D-F) and Aα/β-fibres (G-J). The CV for each unit is shown. Note that the APs of C- and Aδ-nociceptive (HTM, A and D) and unresponsive (C and F) units are broader than C-LTM and D hair units (B and E), respectively, with a difference in RT between the C-HTM and C-LTM units (A and B). Note also the long AHPs in Aδ-nociceptive (D) and unresponsive (F) neurones compared with the very short AHP in the D hair unit (Aδ-LTM, E). Note the very fast AP and AHP in the Aα/β-LTM MS (muscle spindle) unit (H), the fast AP and AHP in the G hair unit (I), the relatively broad AP and long AHP in the Aα/β-HTM (nociceptive) unit (G) and the very long lasting AHP in the T hair unit (J).

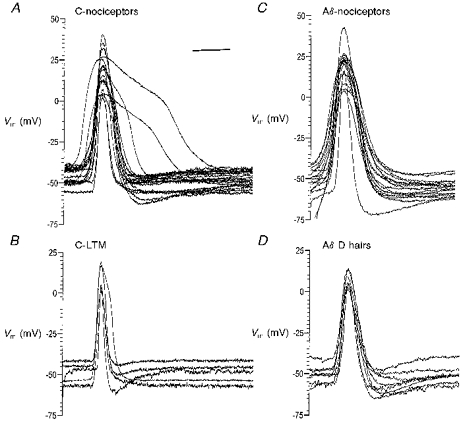

Figure 3. Variability in somatic AP shape of nociceptive and LTM neurones.

Somatic APs evoked intracellularly by dorsal root stimulation in C- and Aδ-nociceptive and LTM groups are superimposed with their peaks aligned to illustrate the range of AP configurations in each group. In the nociceptive groups there were too many units to superimpose, so examples of units spanning the entire range of AP shapes were selected (19 C-fibre units in A and 17 Aδ-fibre units in C). APs from all C-LTM units in the −40 mV group (n = 5) and all Aδ D hair units (n = 8) are shown in B and D, respectively. The scale bar in A applies also to B-D and represents 5 ms for C-fibre units and 2 ms for Aδ-fibre units.

Nociceptive neurones vs. other neuronal types

AP duration at base

Figure 4A and B shows that nociceptive neurones in each CV range tended to have much broader spikes than LTM neurones (for examples see Figs 2 and 3) and that the range in AP duration at base (APdB) was greater in C-fibre nociceptive than in Aδ- and Aα/β-fibre nociceptive neurones.

Whether the −40 mV or the −30 mV group of C-fibre neurones was examined, the APs had highly significantly longer durations in nociceptive than in LTM neurones (Figs 2, 3, 4A and Table 1). Four of the C-LTM units had CVs of about 0.9 m s−1, while the remaining three had CVs of 0.3, 0.3 and 0.7 m s−1. C-Cooling (Cool) units also had broader spikes than C-LTM units (Fig. 4A and Table 1) with remarkably little variation in spike duration, unlike the C-nociceptive units. Of the six C-cooling units, two responded to noxious mechanical stimuli but the best response achieved was with cooling, while for the others no mechanically excitable field was found.

There are not enough data from individual subgroups of C-nociceptive neurones (e.g. C-PM and C-HTM) for statistical comparison of their electrophysiological properties as yet. The three longest duration APs were observed in two C-PM units and a C-HTM unit. There is no evidence so far that either the AP or the AHP duration of C-HTM units is related to the depth of the receptive terminals in the tissue (superficial, dermal or deep, i.e. subcutaneous). Further data are needed to clarify all these points.

Similarly A-nociceptive neurones had APs with longer durations than those of A-LTM units. This difference was highly significant both for Aδ-nociceptive versus D hair units (see Figs 2, 3, 4 and Table 1), and for Aα/β-nociceptive versus -LTM units, although there was considerable overlap between these Aα/β groups (Fig. 4B and Table 1). Unresponsive units also had longer AP durations than LTM units in both the Aδ- and the Aα/β-fibre range (highly significant, see Table 1) with mean values close to those of the A-nociceptive units.

AP rise time and fall time

To examine the contribution of AP rise time (RT) and fall time (FT) to the overall differences in AP duration at base, RT and FT were examined separately. In all three CV ranges, RT was highly significantly shorter in LTM neurones than in nociceptive neurones (Fig. 4C and D, and Table 1; for examples see Figs 2 and 3). Fall time was also shorter; this finding was highly significant for C- and Aδ-fibre neurones and significant for Aα/β-fibre neurones (Fig. 4E, 4F and Table 1). As a percentage of the Aα/β-nociceptor mean values (Table 1), the Aα/β-LTM neurones showed a more greatly reduced RT (reduced by 43 %) than FT (reduced by only 21 %). C-Cooling units had FTs that were significantly longer than those in C-LTM units (Fig. 4E and Table 1). Aδ- and Aα/β-unresponsive units had longer RTs and FTs than LTM units in their respective CV ranges; in both CV ranges this was highly significant for RTs and significant for FTs (Fig. 4D, 4F and Table 1).

Relationship of rise time to fall time

Graphs were plotted (not shown) to examine the dependence of the FT (Y-axis) on the RT (X-axis). There was no clear relationship between these two variables for either Aδ-LTM or Aδ-nociceptive units. However, there was a significant correlation between RT and FT in Aα/β-LTM units (P < 0.0001, r2 = 0.42) and in Aα/β-nociceptive units (P < 0.0062, r2 = 0.26). The slopes for these two regression lines were significantly different (F = 5.5, P < 0.02) with slopes of 0.21 ± 0.03 for the LTM and 0.48 ± 0.16 for the nociceptive neurones. There were also significant correlations between RT and FT in C-LTM units (P= 0.003, r2 = 0.97 and C-nociceptive units (P = 0.03, r2 = 0.17). The slopes for these lines were 1.4 ± 0.15 and 1.5 ± 0.7, respectively, and were not significantly different. Only C-fibre units with Vm values more negative than −40 mV were included.

Afterhyperpolarization duration to 80 % recovery

Nociceptive neurones had longer AHP80s than LTM units in all CV ranges. Only five C-mechanoreceptive (LTM) units in the −30 mV group displayed negative-going AHPs: their mean AHP80 was highly significantly shorter than that for the C-nociceptor units (Fig. 5A and Table 1). The difference between AHP80 in nociceptive and LTM units was also highly significant for Aδ- and Aα/β-fibre units, (Fig. 5B and Table 1). However, the Aα/β-LTM T hair units had AHPs as long as those of the Aα/β-nociceptive units (see later).

Unresponsive units also showed longer mean AHP80 values than LTM units, the difference being highly significant in all three CV ranges (Fig. 5A, 5B and Table 1). In both C- and Aδ-CV ranges the unresponsive units tended to have AHP80s that were even longer than those in nociceptive units although the differences were not significant (Fig. 5 and Table 1).

Conduction velocities of different groups of units

The distributions of CVs for individual units in each class are plotted in Fig. 5C and D (see also Table 1). Points to note are that most C-LTM units had CVs at the upper end of the C-fibre range, although two were slow. The mean CV of C-LTMs was therefore higher than for C-nociceptors (not significant) and C-cooling units (highly significant for the −30 mV group). In the Aα/β-range, the LTM units tended to have CVs considerably faster than most nociceptive or unresponsive units (highly significant in both cases).

Subgroups of A-LTM neurones

Differences in the AP and AHP variables were also found between subgroups of A-LTM neurones, with extremely short mean AP and AHP durations in MS afferents, intermediate mean AP and AHP durations in G hair/field units and very long AHPs in T hair units (Figs 6, 7 and Table 2; for examples see Fig. 2). SA units had very short AP and AHP durations but since there were only two this group was excluded from all statistical analysis.

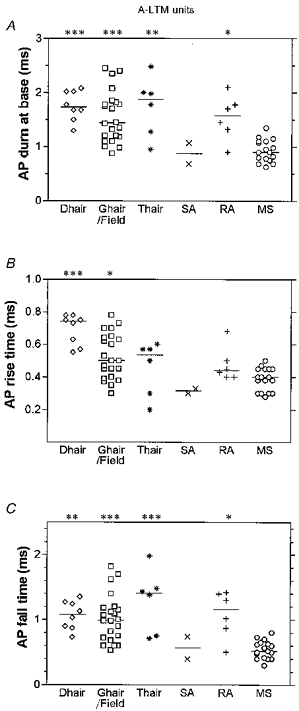

Figure 6. AP variables of A-LTM units with different sensory properties.

Scatter plots of distributions of variables, with the median (horizontal bar) superimposed in each case, grouped according to the sensory properties of the neurones. The D hair units had Aδ-fibre CVs, and all other groups had Aα/β-fibre CVs. G hair and field units were combined (see text). Asterisks above the graph indicate significant differences which in all cases were between the data in that column and the muscle spindle group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The absence of asterisks indicates the absence of any significant difference but note that since there were only two SA units, this group was excluded from statistical tests.

AP duration at base

MS units had brief AP durations significantly shorter than those of D hair, G hair/field, T hair and RA units (Figs 2, 6A and Table 2).

AP rise and fall times

MS, RA and SA units had short mean RTs (Fig. 6B and Table 2). D hair units displayed the longest mean RT (0.7 ± 0.1 ms, n = 8) of the A-fibre LTM groups, this was significantly different from the mean RTs for MS units, and highly significantly different (P= 0.0002, Mann-Whitney U test) from the mean RT for all Aα/β-fibre LTM units combined (0.46 ± 0.13 ms, n = 53, see Table 1). MS units had a significantly shorter RT than D hair and G hair/field units. Differences in FTs were even greater than the differences in RTs between neurones with differing receptive properties. Again MS units had the fastest mean FT, which was highly significant compared with mean FTs for each of the hair groups (D, G and T) and which was also significant compared with the mean FT for RA units (Fig. 6C and Table 2). SA units also had very short fall times.

Afterhyperpolarization duration to 80 % recovery

Apart from the T hair group that had a mean AHP80 of 30 ms, all A-LTM groups had short mean AHP80 values of 1.4–4 ms. SA and MS units had the shortest mean AHP80 values. The difference in AHP80 values for T hair units compared with MS units was highly significant, and for T hair units compared with G hair/field units was significant (see Fig. 7A and Table 2). The AHP80 for the T hair group was also longer than the AHP80 for all other LTM Aα/β-fibre units together (2.77 ± 1.4 ms, n = 47) and longer than that for all LTM A-fibre units grouped together (2.9 ± 1.4 ms, n = 55) (P < 0.0001 in both cases, Mann-Whitney U test). There was, however, no significant difference between the AHP80 values for T hair units and those for either the Aδ- or Aα/β-nociceptive units (P > 0.1 in both cases, Mann-Whitney U test).

Conduction velocity

Figure 7B shows the distributions of CVs for the different groups. CVs for the Aα/β groups were compared statistically, and the mean CVs for G hair/field units found to be slower than those for MS units (highly significant). Most of the very fast units were MS units.

AP duration vs. AHP duration

To determine whether there was a relationship between AHP and AP durations in somata of the different receptor types, these variables were plotted against each other both as untransformed values and as log10 values (log10 was chosen because of the distributions of the data shown in Figs 4A and 5A). The log-log plots showed much stronger linear correlations than the untransformed data, and these log-log correlations are therefore presented here. There was no correlation between the log10 of these variables for nociceptors whether all CV ranges were considered together, A-fibre nociceptive units were grouped together or all CV ranges considered separately (Fig. 8A) or for unresponsive units within any of the CV ranges (not shown). These variables were, however, correlated for all LTM units of all CVs (excluding T hair units) taken together (P < 0.0001 r2 = 0.38, see Fig. 8B) and for all Aα/β-LTM units (again excluding T hair units) (P < 0.0001, r2 = 0.38) but not for D hair units on their own (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, when these Aα/β-LTM units were subdivided, significant correlations were found for both the G hair/field and the MS groups of neurones (Fig. 8C). If nociceptive and LTM units were considered together for each CV range (Fig. 8D), there was a significant linear correlation between these variables for Aδ- and Aα/β-fibre neurones but not for C-fibre neurones.

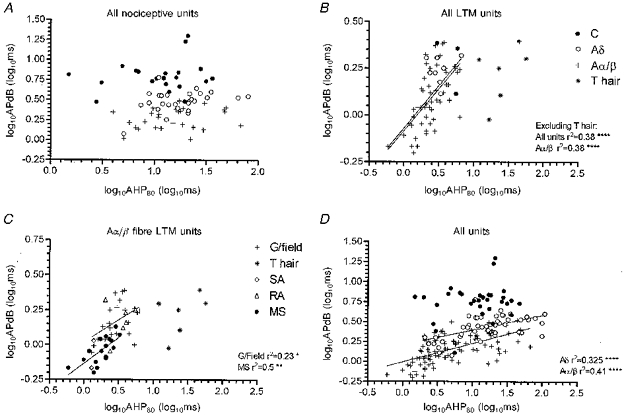

Figure 8. Relationship of AHP duration to AP duration in subgroups of C- and A-fibre units.

Plots of log10AHP80 against log10AP duration (APdB) at base for the following: all nociceptive neurones (A), all LTM neurones (B), and for Aα/β-fibre LTM units (C) and all neurones both nociceptive and other types (D). The −40 mV group of C-cells was used throughout. In A, B and D, data from C-, Aδ- and Aα/β-fibre units are plotted with T hair data plotted separately in B. Symbols shown in B apply also to A and D, those in C relate to that graph only. Linear regression analysis was carried out on each group of cells plotted with separate symbols. Where a significant correlation was found, the linear regression line is plotted and the r2 value is given, with the significance level indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. There was no correlation for the nociceptive groups together or separately (A), but excluding T hair units there was correlation for all LTM units together (B), for Aα/β-LTM units alone (B) and for G hair/field units and MS units (C). There was no correlation for all C-cells but there was correlation for both Aδ- and Aα/β-cells (D).

Relative proportions of nociceptive and other types of unit

Estimating the relative incidence of different types of unit from the data presented so far is complicated by the fact that the proportions of different types of neurones with overshooting APs varied markedly in groups with different CVs and different sensory properties (data not presented here). The selection of data in this paper on the basis of Vm and overshooting AP therefore biases the data in Tables 1 and 2 towards those groups with a greater likelihood of overshooting APs, namely the C-fibre units and, to a lesser extent, the A-fibre nociceptive units. In the earlier experiments of the present series, however, recordings were made from all cells regardless of whether they met these criteria and therefore the proportions of these cells encountered were more likely to reflect the real proportions of different types of unit encountered. Therefore, for the following comparison, only cutaneous units (those with superficial or dermal receptive fields) from these earlier experiments were included. There were 165 identified cutaneous afferent units. Of 37 C-fibre units, 30 were nociceptive, 3 were LTM units and 4 were cooling sensitive. Of 47 identified Aδ cutaneous units 30 were nociceptive and 17 were LTM (D hair). Of 81 cutaneous afferent Aα/β units, 22 were nociceptive and 59 were LTM. Thus of the identified cutaneous afferent units, LTM units made up about 8 % of C-fibre units, 36 % of Aδ-fibre units and > 73 % of Aα/β-fibre units. The last value is an underestimate because even in some of these earlier experiments some Aα/β-LTM units were rejected in order to search for more slowly conducting units. An unknown bias may still remain in the above ratios if LTM and nociceptive units are not evenly distributed within the DRG since the dorsal 2–300 μm of the DRG was the usual site of penetration. In addition, the proportions of Aα/β- versus Aδ- versus C-fibre units are probably somewhat biased by the greater ease of making stable penetrations in large A-fibre than in small C-fibre cells.

DISCUSSION

The boundaries between the CV ranges in this study, established from compound APs, were relatively low, due, as reported previously (Lawson et al. 1997), to a number of factors: (1) the young age of the animals (150–300 g), (2) the low temperature in the paraffin pool, (3) the generally lower CVs in the dorsal root than in peripheral nerve fibres (Waddell et al. 1989), (4) the inclusion of the utilization time within the latency used for estimating CVs.

In this study, recordings were made with a core temperature of 36°C and the temperature near the DRG maintained at 28.5–31°C. Previous studies had been made in rat and cat, respectively, with similar or slightly higher core temperatures but with no indication of temperature at the dorsal root ganglia (Koerber et al. 1988; Ritter & Mendell, 1992). It is therefore not clear whether the actual values are directly comparable with these studies or not, given that AP and AHP durations would probably be increased at lower temperatures.

The present data were obtained from most functional classes (see Results) of primary afferent neurones reported previously in rat (Lynn & Carpenter, 1982), cat (Burgess & Perl, 1967) and guinea-pig (Lawson et al. 1997) including G and D hair units described in the cat and rat (Burgess & Perl, 1967; Lynn & Carpenter, 1982) and T hair units that were described in the cat and rabbit (see Brown & Iggo, 1967). Other sensitive mechanoreceptors included in the analysis were slowly adapting (SA), rapidly adapting (RA) and muscle spindle afferent units. These units were similar to those reported previously in other species (see Lawson et al. 1997).

In addition to the defined units, a number of unresponsive units failed to respond to the full range of mechanical and thermal stimuli. The majority of these were probably inexcitable or very high threshold units. However, a few units with inaccessible receptive fields or units activated only by chemical stimuli could also have been included in this group. Interestingly, the mean values of the AP variables for the unresponsive units tended to be similar to those for the nociceptive units, with mean AHP80 values even longer (not significantly) than those for nociceptive units in the C- and Aδ-fibre groups. Proportions of inexcitable units cannot be usefully derived from the present data since a number of only partially tested units were excluded from this data set. Unresponsive afferent C-fibre units, sometimes called silent units, have been described in varying proportions in cutaneous nerves of, for instance, rat (Lynn & Carpenter, 1982; Pini et al. 1990; Gee et al. 1996), cat (Bessou & Perl, 1969) and monkey (Meyer et al. 1991).

Nociceptive versus LTM neurones

A-fibre units

In guinea-pig dorsal root ganglia, Aδ- and Aα/β-fibre nociceptors proved to have broader somatic APs than LTM units, as previously shown for A-fibre nocieptors in rat and cat dorsal root ganglia (Rose et al. 1986; Koerber et al. 1988; Ritter & Mendell, 1992). The percentage reduction in AP duration for LTM units compared with that for nociceptive neurones was, however, greater in Aδ- (50 %) than in Aα/β-neurones (30 %), with a lower mean duration in Aα/β- than in Aδ-nociceptive neurones. The smaller overlap between values for nociceptive and LTM neurones in Aδ- than in Aα/β-units was due to a greater range in Aα/β-LTM units, and a lower mean duration in Aα/β-nociceptive neurones than in the equivalent Aδ groups. The RT and FT were examined to establish which contributed most to the differences in AP duration between nociceptive and LTM neurones. Both the RTs and FTs were faster in Aδ-LTM than in Aδ-nociceptive neurones by 40 % and 43 %, respectively, thus apparently contributing equally to the overall faster APs in these LTMs. Again in the Aα/β-neurones both RTs and FTs were lower in LTM compared with nociceptive neurones, but the reduction in RT (43 %) was much greater than the reduction in FT (21 %). These longer APs in nociceptors would probably reduce the maximum firing rate of the membrane compared with shorter duration APs. Possible mechanisms underlying these differences will be discussed later.

As well as having longer duration APs, nociceptive A-fibre neurones had longer AHPs compared with LTM neurones, as previously demonstrated in rat and cat dorsal root ganglia (Koerber et al. 1988; Ritter & Mendell, 1992). These long AHPs would provide a long relative refractory period that would probably limit the firing rate of the membrane. Thus both long APs and long AHPs would tend to limit the firing rate of the nociceptive neurones, if the properties of the soma membrane described here are a reflection of membrane properties throughout the neurone. It has previously been shown that rat DRG A-fibre neurones with substance P-like immunoreactivity (SP-LI) have longer AHP durations than those without (McCarthy & Lawson, 1997), and that in the guinea-pig the neurones expressing SP-LI are nociceptive (Lawson et al. 1997). It remains to be seen how closely the expression of SP and of channels giving rise to these long AHPs are linked.

C-fibre units

C-LTM units made up about 8 % of the identified C-fibre afferent neurones in this study. This proportion is similar to that reported in rat by Lynn & Carpenter (1982) who found that 12 % of their 149 afferent C-fibres in saphenous nerve were sensitive C-fibre mechanoreceptors (C-LTM units). However, in cat, the value is much higher since nearly 50 % of C-fibre neurones in dorsal root ganglia and 36 % of C-fibres in peripheral nerves were C-LTM units (Bessou et al. 1971).

The only published comparison of intracellular APs in C-nociceptive and C-LTM DRG neurones was in the cat; six C-HTM and six C-LTM units all had broad APs (Traub & Mendell, 1988). Our findings were very different from this. The C-LTM neurones in guinea-pig dorsal root ganglia had narrower spikes than nociceptive neurones, with all seven C-LTMs having narrow APs. Interestingly, recent extracellular recordings of afferent C-fibres in pig showed that the AP duration at half-amplitude for C-mechanoreceptors was significantly shorter than that for C-nociceptors (Lynn et al. 1995) which appears to (a) support our finding that C-LTM neurones have narrower APs, and (b) indicate that the differences seen in the soma membrane may indeed reflect differences throughout the whole nerve cell. In the present study, the C-LTM units also had faster mean RT, FT and AHP80 values indicating that the differences between C-LTM and C-nociceptive units are as great and as far reaching as those between A-LTM and A-nociceptive units. Although four of the C-LTM neurones had CVs at the top end of the C-fibre range and could be argued to have properties similar to very slowly conducting D hair units, even the three more slowly conducting units (0.3–0.7 m s−1) showed short duration APs, with fast RTs and FTs. There was no previously published information on RT, FT or AHP durations in C-LTM units. Thus C-LTMs have fast duration APs in pig and guinea-pig but apparently not in cat. The wide range of AP durations previously reported in C-fibre DRG cells of pigeon (Görke & Pierau, 1980) and rat (Yoshida & Matsuda, 1979; Harper & Lawson, 1985) may result in part from C-LTM neurones having narrow APs and C-fibre nociceptive neurones having a wide range of AP durations but tending to have broad APs.

The similarity in the pattern of electrophysiological properties of nociceptive neurones in all CV ranges may indicate an important functional advantage of these properties. The elevated threshold in these neurones would limit the activation of these neurones, while the AP and AHP configurations appear likely to limit the rate of firing, thus also reducing the number of APs transmitted by these neurones in response to acute activation of nociceptive endings.

Are the membrane differences limited to the neuronal soma?

The present data taken with those of Lynn et al. (1995) showing shorter AP durations in C-mechanoreceptor fibres than in C-nociceptor fibres indicate that the differences in membrane properties described in this paper between nociceptive and LTM neurones are probably not limited to the soma membrane, at least not for C-fibre neurones.

C-fibre cooling units

C-fibre units responding to cooling had mean AP duration and AHP80 values that fell within the range of C-nociceptors with much less scatter in AP values than in the nociceptive group. We have no information about the thermal thresholds of these units. There is no mention of this sub-population in other studies addressing the correlation between somatic AP and afferent modality.

Differences in A-fibre LTM neurones

To our knowledge there has been no previous attempt to compare the AP and AHP configurations in different types of LTM units. This may be partly because the differences are, in the main, more subtle than those between nociceptive and LTM neurones. Nonetheless some differences between these units became clear. For example, MS units showed the shortest AP durations, and AP fall times. They also showed quite short AHP durations. These fast AP kinetics are consistent with the very rapid and/or continuous firing capabilities of these units. SA units also demonstrated fast AP and AHP kinetics, but with only two units, more data are needed to establish whether this is a pattern. The D hair units showed the slowest AP RTs but were otherwise not easily distinguishable by their AP and AHP configurations from most groups of Aα/β-LTM units. One group that stood out from the rest was the T hair group. These units had by far the longest AHP durations relative to all the other LTM categories, with durations at least as long as those in A-fibre nociceptors. The AP durations and AP FTs of T hair units were also relatively longer than those in the other A-fibre LTM groups, a significant difference when compared with MS or G hair/field units. This points to some clear functionally related differences in membrane properties between T hair and other LTM units. A possible advantage of very long AHPs in T hair units may be to limit the firing of these units to a few APs. These long hairs would be in contact with the ground as long as the foot is in contact with the ground, that is, most of the time. From the teleological standpoint, the most useful information to be gained from these units may be about changes in position of the foot relative to the ground, rather than information about static position.

Ionic mechanisms that may underlie the differences in AP configuration

Both tetrodotoxin sensitive (TTXs) and TTX resistant (TTXr) Na+ currents have been identified in DRG neurones including guinea-pig (see Petersen et al. 1987; Nowycky, 1992). They have different activation and inactivation kinetics, TTXr having much slower kinetics than TTXs currents. The slow TTXr current is expressed in small diameter DRG neurones in rat (Akopian et al. 1996). Since broad, inflected APs of A- and C-fibre DRG neurones in rat are resistant to TTX, while narrow spikes are TTX sensitive irrespective of the CV (Waddell & Lawson, 1990), TTXr currents are thought to contribute to the broader APs. Since Na+ channels are kinetically the fastest type of channel contributing to the AP, the type of Na+ channel (TTXs or TTXr) would have a strong influence on the rising phase of the AP. Thus at least part of the difference in AP duration, especially the difference in the RT, is likely to result from differential expression or activation of TTXs and TTXr Na+ channels, with a likelihood that slow RTs in nociceptors may result from activation of TTXr Na+ channels and the faster RTs in LTM neurones could result from activation of TTXs Na+ channels. Indeed there is differential expression of mRNA for different Na+ channel subunits according to the size of cultured DRG neurones. For example, mRNA for the TTX-sensitive channel subtypes Na1, Na6 and NaG were expressed more in large than small neurones, while that for the TTX resistant subunit SNS was more highly expressed in small neurones (Black et al. 1996). Thus differences in Na+ channel type could perhaps account for the differing relationship (slope) between RT and FT in nociceptive and LTM neurones.

The contribution of Ca2+ inward currents to the broad APs of DRG neurones (with falling phase inflections) is not fully understood. Most investigators attribute falling phase inflections in APs of DRG neurones to Ca2+ influx (for example see Yoshida et al. 1978), although others have suggested that these inflections are Na+ dependent, since they persisted in Ca2+-free solutions (see Oyelese et al. 1997). Ca2+ currents in DRG cells include the L-, T- and N-type currents (Nowycky, 1992), and there is evidence for differential expression of these currents in relation to the size of the DRG neurones (Scroggs & Fox, 1992). It is thus possible that a greater expression or activation of certain types of Ca2+ channels may contribute to the longer duration APs and particularly to the longer FTs seen in nociceptive, unresponsive and C-cooling neurones.

There is little evidence to date on membrane differences in neurones projecting to different types of tissue. One study using patch clamp studies of cultured neurones (Honmou et al. 1994) showed that cutaneous afferent neurones had a combination of fast and slow, or a single relatively slow Na+ current, while the majority of non-cutaneous neurones had a single fast Na+ current. Speculating on the possible cell types recorded from in that study on the basis of the AP durations encountered during this study, it may be that the cutaneous afferent group included a mixture of LTM (possibly with a combination of fast and slow currents) and nociceptive units (possibly with the slow Na+ current), while the non-cutaneous units with very fast kinetics could be muscle spindle afferent neurones, although it might be expected that some nociceptive units with slower kinetics would also have been sampled. However, for these speculations to be verified, information on the receptive properties of neurones with the different types of Na+ current is needed.

Several types of K+ current are found in sensory neurones (Nowycky, 1992), these could contribute to (a) the rapid repolarization in LTM neurones, (b) the long AHPs in nociceptive and T hair neurones and (c) the short AHPs seen in most LTM neurones. Neurones with narrow spikes may have more early outward K+ current leading to a fast repolarization, while neurones with broad spikes may have less early outward K+ current (i.e. during the spike), contributing to a broader AP with greater overshoot and more Ca2+ entry. The entry of more Ca2+ could contribute to the opening of Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channels and thus to the longer AHPs in such cells (Belmonte & Gallego, 1983). A greater expression or activation of KCa channels, (more than one type of which is expressed in guinea-pig DRG neurones, Nowycky, 1992) could contribute to the long AHPs in nociceptive and in T hair neurones. In all other LTM neurones such channels may either be absent or possibly inactive due to lower [Ca2+]i. In addition since short AHPs are primarily due to voltage-gated K+ channels that open during the spike (Nowycky, 1992), activation of these channels may be expected in units with fast AHPs.

At this stage it is unclear whether differences in Ca2+ or K+ currents are more likely to be implicated in the differences in spike duration, or whether both are involved. It is interesting in this context that loss of the inflection on the repolarizing phase of the AP of Xenopus spinal neurones during development was associated more closely with an increase in the K+ rectifier current than with a decrease in the Ca2+ current (O'Dowd et al. 1988).

Since activation of KCa depends on [Ca2+]i and since the amount of Ca2+ entering may depend on the duration of the APs the relationship of the AHP duration to AP duration was examined. Interestingly, although the AHP duration is related to the AP duration in Aα/β-LTM neurones, in the guinea-pig we found no such relationship in nociceptive neurones whether taken together or grouped separately according to CV. This was in contrast to a report that, in cat, AHP duration to 50 % recovery was loosely correlated with AP duration at half-height in A-HTM units (Koerber et al. 1988). The lack of correlation in nociceptive neurones in the present study may indicate that KCa channels are maximally activated, perhaps due to a substantial Ca2+ inward current in all such cells. In contrast the strong correlation between these parameters in LTM Aα/β-neurones with an r2 of 0.38 appears to indicate some dependence of AHP duration on AP duration which could be explained if the amount of Ca2+ entering is related to AP duration in these neurones.

In conclusion, it is clear that there are substantial differences in AP configuration in nociceptive and LTM neurones in guinea-pig DRGs in both A- and C-fibre CV ranges. The nociceptive neurones in all CV ranges showed longer AP durations and longer AHP durations. Unresponsive neurones generally had properties similar to those of nociceptive units in the same CV range. In addition differences were seen between subgroups of A-fibre LTM neurones. The MS units had the fastest AP kinetics, while T hair units stood out by having much longer AHP durations than any other group of LTM unit. Most studies on differences in ion currents in DRG neurones have so far been on isolated DRG neurones. Some have been related to cell size but none have been directly related to sensory function. Studies of the contribution of different types of ion channel to the characteristic membrane properties of different types of sensory neurone need to be made in neurones with known sensory properties. In addition, since ion channel expression can alter in axotomized neurones (Cummins & Waxman, 1997) and during inflammation (Tanaka et al. 1998), it may also prove important to establish the mechanisms by which ion channel expression or activation can be altered, and the effects of such alterations on membrane properties and firing patterns in these different types of neurones.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust, UK. We thank Carol Moore and Barbara Carruthers for technical assistance.

References

- Akopian AN, Sivilotti L, Wood JN. A tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel expressed by sensory neurons. Nature. 1996;379:257–262. doi: 10.1038/379257a0. 10.1038/379257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte C, Gallego R. Membrane properties of cat sensory neurones with chemoreceptor and baroreceptor endings. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;342:603–614. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessou P, Burgess PR, Perl ER, Taylor CB. Dynamic properties of mechanoreceptors with unmyelinated (C) fibers. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1971;34:116–131. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessou P, Perl ER. Response of cutaneous sensory units with unmyelinated fibers to noxious stimuli. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1969;32:1025–1043. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JA, Dib-Hajj S, Mcnabola K, Jeste S, Rizzo MA, Kocsis JD, Waxman SG. Spinal sensory neurons express multiple sodium channel alpha-subunit mRNAs. Molecular Brain Research. 1996;43:117–131. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AG, Iggo A. A quantitative study of cutaneous receptors and afferent fibres in the cat and rabbit. The Journal of Physiology. 1967;193:707–733. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PR, Perl ER. Myelinated afferent fibres responding to noxious stimulation of the skin. The Journal of Physiology. 1967;190:541–562. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AA, Leah JD, Snow PJ. The electrophysiological and morphological characteristics of feline dorsal root ganglion cells. Brain Research. 1986;362:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91391-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Waxman SG. Downregulation of tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium currents and upregulation of a rapidly repriming tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current in small spinal sensory neurons after nerve injury. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:3503–3514. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouhri L, Bleazard L, Swanson G, Lawson SN. Are broad action potentials (APs) and long afterhyperpolarisations (AHPs) exclusive to nociceptive somatic afferent dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1997;23:1527. [Google Scholar]

- Gee MD, Lynn B, Cotsell B. Activity-dependent slowing of conduction velocity provides a method for identifying different functional classes of C-fibre in the rat saphenous nerve. Neuroscience. 1996;73:667–675. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00070-x. 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz SA. Primer of Biostatistics. New York, London: McGraw-Hill Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Görke K, Pierau F. Spike potentials and membrane properties of dorsal root ganglion cells in pigeons. Pflügers Archiv. 1980;386:21–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00584182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper AA, Lawson SN. Electrical properties of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones with different peripheral conduction velocities. The Journal of Physiology. 1985;359:47–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honmou O, Utzschneider DA, Rizzo MA, Bowe CM, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Delayed depolarization and slow sodium currents in cutaneous afferents. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:1627–1637. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.5.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber HR, Druzinsky RE, Mendell LM. Properties of somata of spinal dorsal root ganglion cells differ according to peripheral receptor innervated. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1988;60:1584–1596. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.5.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson SN, Crepps BA, Perl ER. Relationship of substance P to afferent characteristics of dorsal root ganglion neurones in guinea-pig. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:177–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn B, Carpenter SE. Primary afferent units from the hairy skin of the rat hind limb. Brain Research. 1982;238:29–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90768-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn B, Schütterle S, Pierau FK, Faulstroh K, Basile S. The duration of axonal action potentials varies with the afferent type for C-fibres innervating the skin of the anaesthetized pig. Japanese Journal of Physiology. 1995;45:S243. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy PW, Lawson SN. Differing action potential shapes in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones related to their substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;388:541–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA, Davis KD, Cohen RH, Treede RD, Campbell JN. Mechanically insensitive afferents (MIAs) in cutaneous nerves of monkey. Brain Research. 1991;561:252–261. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91601-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowycky MC. Voltage-gated ion channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. In: Scott SA, editor. Sensory Neurons Diversity, Development and Plasticity. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- O'Dowd DK, Ribera AB, Spitzer NC. Development of voltage-dependent calcium, sodium, and potassium currents in Xenopus spinal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:792–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-00792.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyelese AA, Rizzo MA, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Differential effects of NGF and BDNF on axotomy-induced changes in GABA(A)-receptor-mediated conductance and sodium currents in cutaneous afferent neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:31–42. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Pierau F-K, Weyrich M. The influence of capsaicin on membrane currents in dorsal root ganglion neurones of guinea-pig and chicken. Pflügers Archiv. 1987;409:403–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00583794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini A, Baranowski R, Lynn B. Long-term reduction in the number of C-fibre nociceptors following capsaicin treatment of a cutaneous nerve in adult rats. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;2:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1990.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter AM, Mendell LM. Somal membrane properties of physiologically identified sensory neurons in the rat: Effects of nerve growth factor. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:2033–2041. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RD, Koerber HR, Sedivec MJ, Mendell LM. Somal action potential duration differs in identified primary afferents. Neuroscience Letters. 1986;63:259–264. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Calcium current variation between acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons of different size. The Journal of Physiology. 1992a;445:639–658. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Multiple Ca2+ currents elicited by action potential waveforms in acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992b;12:1789–1801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01789.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfli R, Hille B. Electrophysiology of the peripheral myelinated nerve. In: Llinás R, Precht W, editors. Frog Neurobiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1976. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Cummins TR, Ishikawa K, Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Waxman SG. SNS Na+channel expression increases in dorsal root ganglion neurons in the carageenan inflammatory pain model. NeuroReport. 1998;9:967–972. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RJ, Mendell LM. The spinal projection of individual identified Ad- and C-fibers. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1988;59:41–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell PJ, Lawson SN. Electrophysiological properties of subpopulations of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones in vitro. Neuroscience. 1990;36:811–822. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell PJ, Lawson SN, McCarthy PW. Conduction velocity changes along the processes of rat primary sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 1989;30:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Matsuda Y. Studies on sensory neurones of the mouse with intracellular recording and dye injection techniques. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1979;42:1134–1145. doi: 10.1152/jn.1979.42.4.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Matsuda Y, Samejima A. Tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium and calcium components of action potentials in dorsal root ganglion cells of the adult mouse. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1978;41:1096–1106. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.5.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]