Abstract

Oligonucleotide primers based on the human heart monocarboxylate transporter (MCT1) cDNA sequence were used to isolate a 544 bp cDNA product from human colonic RNA by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The sequence of the RT-PCR product was identical to that of human heart MCT1. Northern blot analysis using the RT-PCR product indicated the presence of a single transcript of 3.3 kb in mRNA isolated from both human and pig colonic tissues. Western blot analysis using an antibody to human MCT1 identified a specific protein with an apparent molecular mass of 40 kDa in purified and well-characterized human and pig colonic lumenal membrane vesicles (LMV).

Properties of the colonic lumenal membrane l-lactate transporter were studied by the uptake of L-[U-14C]lactate into human and pig colonic LMV. l-lactate uptake was stimulated in the presence of an outward-directed anion gradient at an extravesicular pH of 5.5. Transport of l-lactate into anion-loaded colonic LMV appeared to be via a proton-activated, anion exchange mechanism.

l-lactate uptake was inhibited by pyruvate, butyrate, propionate and acetate, but not by Cl− and SO42−. The uptake of l-lactate was inhibited by phloretin, mercurials and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (4-CHC), but not by the stilbene anion exchange inhibitors, 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic acid (DIDS) and 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic acid (SITS).

The results indicate the presence of a MCT1 protein on the lumenal membrane of the colon that is involved in the transport of l-lactate as well as butyrate across the colonic lumenal membrane. Western blot analysis showed that the abundance of this protein decreases in lumenal membrane fractions isolated from colonic carcinomas compared with that detected in the normal healthy colonic tissue.

Short-chain fatty acids, SCFA, (acetate, propionate and butyrate) are produced in the lumen of the colon as a result of fermentation of dietary fibre by the colonic microflora (Cummings, 1984). Relatively small amounts of other organic compounds such as methane, lactate, and ethanol are also produced (Bergman, 1990). SCFA play a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis in the colon. Colonic epithelia derive 60–70% of their energy supply from SCFA, particularly butyrate. Butyrate induces cell differentiation, regulates the growth and proliferation of normal colonic mucosa (Treem et al. 1994), and reduces the growth rate of colo-rectal cancer cells in culture (Berry & Paraskeva, 1988).

Although the functional characteristics of l-lactate transport in erythrocytes have been known for many years, it was only recently that the structure of the transporter was identified at the molecular level and was designated monocarboxylate transporter 1, MCT1 (Garcia et al. 1994a). This protein facilitates the transport of the monocarboxylates, pyruvate and l-lactate, across the plasma membrane of chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Subsequently, a second monocarboxylate transporter MCT2, with different tissue distribution and different inhibitor sensitivities, was cloned from a Chinese hamster liver cDNA library (Garcia et al. 1995). Chinese hamster liver MCT2 is 60% identical to CHO MCT1. The presence of a MCT family with several members has now been confirmed by the cloning and sequencing of seven mammalian isoforms (Halestrap et al. 1997; Price et al. 1998). Amongst the monocarboxylate transporter isoforms, MCT1 has the broadest substrate specificity. There are diversities in kinetics, substrate and inhibitor characteristics of monocarboxylate transport into a range of mammalian cells. These differences have led Halestrap and colleagues (Jackson et al. 1997; Price et al. 1998; Wilson et al. 1998) to propose that differences in the properties of MCT isoforms are related to the metabolic requirements of the tissue in which they are expressed.

l-lactate has been shown to be transported across rabbit small intestinal brush border (Tiruppathi et al. 1988) and rat intestinal basolateral membranes (Cheeseman et al. 1994). A cDNA encoding MCT1 has been cloned for the rat small intestine (Takanaga et al. 1995). Until recently, no information was available on the possible presence of any MCT isoforms in the colonic tissue. We have shown in a preliminary report that MCT1 mRNA is expressed in human and pig colonic tissues (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998b). Subsequently, this observation has been confirmed by Price et al. (1998).

In a previous paper, we have shown that butyrate is transported across the pig and human colonic lumenal membrane by an electroneutral anion exchange process stimulated at pH 5.5 (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). Butyrate transport was inhibited by several structural analogues, such as acetate, propionate, pyruvate, l-lactate, α-ketobutyrate, by sulphydryl (SH)-reactive compounds, by phloretin and 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoate (NPPB). In the present paper we report that: (a) l-lactate is transported across the colonic lumenal membrane by an identical mechanism to that described for butyrate transport, (b) the transport is saturable and follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics indicative of a single transport protein, (c) l-lactate transport is inhibited by SCFA and the same pharmacological agents which inhibited colonic butyrate transport, and (d) using oligonucleotide primers derived from the human heart MCT1 cDNA sequence, we isolated a 544 bp cDNA product by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from human or pig colonic RNA that was identical to human heart MCT1. Microinjection of MCT1 cRNA into Xenopus laevis oocytes resulted in the expression of MCT1 protein in the plasma membrane. The expressed protein could transport l-lactate as well as butyrate. Our data clearly show that there is a MCT1 protein expressed on the lumenal membrane of human and pig colon. This transporter is likely to transport l-lactate as well as the SCFA butyrate by an anion exchange mechanism with optimum activity at pH 5.5. In this paper data on the relative abundance of MCT1 protein in the colonic tissue during transition from normality to malignancy is also presented.

The availability of cDNA and antibody probes to the monocarboxylate transporter will facilitate the identification of cellular events by which SCFA interact with the colonic tissue in order to maintain homeostasis.

METHODS

Sodium L-[U-14C]lactate (specific activity 5.6 GBq mmol−1) and [α-32P]dCTP (specific activity 111 TBq mmol−1) were purchased from the Radiochemical Centre, Amersham, Bucks., UK. Sodium [U-14C]butyrate (2.04 GBq mmol−1) was purchased from ARC Inc. St Louis, MO, USA. The antibody to human MCT1, and corresponding peptide antigen to which the antibody was raised, were a kind gift of Dr Robert C. Poole and Prof. Andrew P. Halestrap (University of Bristol, UK). Rat astroglial MCT1 cDNA was kindly donated by Dr S. Bröer (University of Tübingen, Germany). X. laevis oocytes were generously supplied by Dr D. Riccardi (University of Manchester, UK). The membrane filters (Millipore GSWP 02500) were obtained from Millipore Products Division, UK. All chemicals used were of highest analytical grade and purchased from Sigma Dorset, UK unless indicated differently.

Removal and storage of tissue

Pig colonic tissue

Pig colonic tissue was obtained from the abattoir within 10 min of slaughter of the animals. The tissue was treated as described previously (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a).

Normal human colonic tissue

Pieces of histologically normal human proximal or distal colon were obtained from individuals during the course of surgery. Biopsies from various regions of the colon were removed during the course of routine colonoscopy, and their state of health/disease was assessed histologically. Human colonic tissues were also obtained from organ donors, none having a history of intestinal disease. After removal they were designated as proximal, mid and distal regions. All the tissues were immediately rinsed with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl pH 7.0, wrapped in aluminium foil, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. On the day of the experiment, the colonic tissue was thawed out in a hypotonic buffer containing protease inhibitors (100 mm mannitol, 2 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.1, 0.2 mm benzamidine, 0.2 mm phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride) and cut open longitudinally. The mucosa was scraped off and luminal membrane vesicles (LMV) were prepared as described before (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a).

Prior histological examination of the pig and human tissues showed that the colonocytes were intact and attached to the muscularis mucosa. Initial studies indicated that the mechanism and properties of l-lactate transport were identical in proximal, mid and distal regions of either human or pig colon. Therefore, in the studies reported in this paper, mucosal scrapings from all three regions were pooled and used as the starting cellular homogenate. Pig colonic tissue has been used in experiments throughout the paper. Due to a limited supply, human tissue has been used in a selective manner.

Diseased human colonic tissues

Polyps (precancerous tissue) were obtained from patients undergoing colonoscopic polypectomy (adenomas, n = 10). Biopsy size samples and segments of tissues were removed from patients with colon cancer (carcinomas) who had undergone either right-sided or left sided hemicolectomy (n = 8). The diseased tissues were rapidly rinsed with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl (pH 7.0), wrapped in aluminium foil, rapidly frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use.

For the work with the human tissue the approval of the Broadgreen Hospital NHS Trust and South Sheffield Ethical Committees were obtained.

Isolation and characterization of colonic lumenal membrane vesicles (LMV) from normal colonic tissues

Human and pig colonic LMV were isolated as described previously (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). In brief, mucosal scrapings from the entire colon were homogenized and filtered through nylon gauze to remove fat and excess mucus. LMV were isolated using Mg2+ precipitation and differential centrifugation steps. The final pellet was resuspended in a minimal volume (400–800 μl) of a final buffer (given in figure legends). LMV were preloaded with various solutions using a procedure based on that of Rudnick (1977) and Shirazi-Beechey et al. (1988). A 100 μl suspension of LMV (2 mg protein) was diluted with 1 ml of the solution with which the vesicles were to be loaded (loading solution). The suspension was made homogenous by passing through a 27 gauge needle. The suspension was centrifuged at 30 000 g for 30 min. The pellet containing LMV was then resuspended in 400–800 μl of loading solution using the 27 gauge needle. The vesicles were then placed in liquid nitrogen for a minimum of 5 min before removal and use.

Isolation and characterization of plasma membrane fractions isolated from biopsy samples of healthy and diseased human colonic tissues

This technique is based on the procedure described by Shirazi-Beechey et al. (1990) for the isolation of brush-border membrane vesicles from human small intestinal biopsies, with minor modifications. Biopsy samples of human colonic tissue (either healthy or diseased) were thawed in 200 μl of a buffer containing protease inhibitors as described earlier (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). The tissue was homogenized with a Vibromixer (Chemap AG, model E1) using a glass probe (Shirazi-Beechey et al. 1990) for 2 × 1 min at maximum speed. Connective tissue was removed by suction through a micropipette. MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mm and the tubes were mixed gently for 20 min on a rotary mixer at 4°C. The suspension was centrifuged at 1500 g for 12 min. The supernatant was removed and centrifuged at 30 000 g for 45 min. The final pellet was suspended in 300 mm mannitol, 0.1 mm MgSO4 and 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5 by passing several times through a Hamilton syringe. The vesicles were stored in liquid N2 until use.

The relative purity of the plasma membrane fractions were assessed by estimation of the activity of marker enzymes and Western blot analysis of the antigenic proteins, as described previously (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). The activity and abundance of marker enzymes characteristic of organelle and basolateral membranes were negligible in the final membrane fractions. Conversely, the activity and abundance of several colonic lumenal membrane markers were significantly enriched in the LMV isolated from segments of normal human and pig colon (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). In the membrane fractions isolated from the diseased tissues, villin the marker of the lumenal membrane of colonic tissue (Robine et al. 1985) was 4- to 5-fold enriched over the starting cellular homogenate, indicating the lumenal membrane origin of the isolated membrane fractions.

Estimation of protein

Protein was determined by the ability to bind Coomassie Blue according to the BioRad assay technique. Bovine gamma globulin (30–150 μg) was used as a standard (Tarpey et al. 1995).

Uptake of L-[U-14C]lactate into LMV isolated from normal human and pig colon

Transport of l-lactate into colonic LMV was measured using a rapid filtration stop technique as described by Shirazi et al. (1981), with some modifications. Incubation buffer for uptake varied according to the conditions tested. Composition of buffers used is given in the figure legends. Generally, the uptake reaction was started by adding 100 μl of incubation buffer to 5 μl (100 μg) of colonic LMV. Incubation was stopped after 5 s by addition of 1 ml ice-cold stop solution (100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium gluconate, 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5 and 0.1 mm sodium l-lactate). Aliquots of this solution were then filtered rapidly through 0.2 μm Millipore filters, which were then counted for radioactivity. For the kinetic analysis, l-lactate concentration in the incubation medium was varied from 1–40 mm. Osmolarity of the medium was adjusted by changing the concentration of mannitol in the media. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t test and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Pinches et al. 1993). In brief, membrane fractions were solubilized in SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE on a 8% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Trans-blot, BioRad, UK). Non-specific binding sites were first blocked by incubating the nitrocellulose membrane for 1 h in phosphate-buffered saline-Tween (PBS-TM) buffer [1% (w/v) dry-milk powder (Oxoid), 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 in PBS]. The nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with an affinity purified anti-peptide antibody to the C-terminus region of human MCT1, at a dilution of 1 : 1000, for 2 h in PBS-TM. The specificity of the cross-reaction was determined by pre-incubating the antibody in the presence of the peptide antigen (10 μg ml−1) for 1 h at 37°C prior to use. Secondary antibody swine anti-rabbit, (Dako, Cambridge, UK) was used at a dilution of 1 : 2000 for 1 h in PBS-TM. Immunodetection was performed by chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham International, UK). The antibody to the C-terminus region of human MCT1 was raised to a synthetic peptide (CQKDTEGGPKEEESPV). The synthesis of the peptide, production of the antibody, and its purification were carried out by Dr R. C. Poole (University of Bristol, UK), according to the procedure described before (Poole et al. 1996). Western blot analysis for villin was performed as described previously (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Synthesized oligonucleotide primers based on the human heart MCT1 cDNA were used in RT-PCR against total RNA isolated from normal human and pig intestinal tissues. RNA samples were prepared using a commercially available kit (RNeasy, Qiagen, UK). The whole reaction was performed in a single tube using 5 U of AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega, UK) and 2 U of Bio-X-Act DNA polymerase (Bioline, UK). The antisense primer, nt 588–611 (5′-GGCCCGATTGGTCGCATGAGGGCT-3′) was used to prime the first strand synthesis at 48°C for 45 min. The sense primer, nt 67–90 (5′-GGCTGGGCAGTGGTAATTGGAGCT-3′) was then utilized for DNA amplification. The reaction conditions were as follows: 1 × NH4 buffer (16 mm (NH4)2SO4, 67 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20); 200 μm each deoxy nucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 50 pmol primers, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 μg total RNA. PCR amplification was performed at 94°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s; 72°C, 60 s for 30 cycles. A final extension of 10 min at 72°C was included. The RT-PCR product was directly subcloned into pGEM-T (Promega, UK) and custom sequenced.

Northern blot analysis

RNA samples (5 μg each), isolated as described above, were fractionated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel containing 0.66 m formaldehyde. The RNA samples were transferred to a nylon membrane (Duralon-UV, Stratagene, UK) by capillary action and were cross-linked with UV light irradiation. The integrity of RNA samples and the assessment of equal sample loading were determined by staining the nylon membranes with Methylene Blue (Herrin & Schmidt, 1988). The membranes were prehybridized for 4 h at 42°C in a buffer containing 50% (v/v) formamide, 5 × saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer, 3 × Denhardt's reagent, 0.2% (w/v) SDS, 10% (w/v) dextran sulphate, 2.5 mm sodium phosphate and 25 mm Mes, pH 6.5. The 544 bp human colonic RT-PCR product was labelled with [α-32P]dCTP by random priming and added to the hybridization buffer. Following incubation at 42°C for 16 h, the nylon membranes were subjected to 15 min washes at 55°C, once with 5 × SSC, 0.5% (w/v) SDS, 0.25% (w/v) Sarkosyl, and three times with 0.1 × SSC, 0.1% (w/v) SDS. The nylon membranes were apposed to Kodak X-OMAT AR film with intensifying screens (HI-Speed, Hoefer) at −80°C.

Preparation of oocytes and microinjection

Xenopus laevis purchased from Blades Biologicals (Kent, UK) were generously supplied by Dr D. Riccardi (University of Manchester, UK). The animals were anaesthetized by immersion in 0.15% (w/v) solution of Tricaine (Sigma, UK) prior to decapitation and pithing. This procedure is approved by the UK Home Office under schedule 1 of the Animals (scientific procedures) Act, 1986. Pieces of ovary were placed in modified Barth's solution (88 mm NaCl, 1 mm KCl, 0.82 mm MgSO4, 0.41 mm CaCl2, 0.33 mm Ca(NO3)2, 2.4 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm Hepes pH 7.6) and transported to the laboratory in Liverpool. Oocytes were treated with 1.5 mg ml−1 collagenase, Type II, (Sigma, Dorset, UK) for 40–50 min in Ca2+-free ovarian Ringer solution to remove the follicular layer. After collagenase treatment, oocytes were rinsed several times in Ca2+-free ovarian Ringer solution (96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm Hepes pH 7.5) before being transferred to modified Barth's solution. Oocytes were microinjected with either 40 nl sterile water or 40 nl (20 ng) rat MCT1 cRNA cloned into the oocyte expression vector, pGEM-He (Bröer et al. 1997) using a nanoject automatic microinjector (Drummond, UK) under a stereomicroscope. They were incubated for 4 days at 18°C in Barth's solution containing 0.1% (v/v) gentamicin (Sigma, Dorset, UK) with daily changes of the medium.

cRNA synthesis

MCT1 cDNA was linearized with Sal I and transcribed in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase (Promega, UK) and the RNA cap analogue, m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G (Pharmacia, Herts., UK). The cRNA was phenol- chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated. The integrity of the cRNA was verified by denaturing agarose gel-electrophoresis and visualization using ethidium bromide.

Functional assay in oocytes

Measurements for either l-lactate or butyrate uptake into oocytes were carried out at 22°C by incubating 5–8 oocytes in 400 μl Barth's solution pH 7.0 containing either 0.1 mm L-[U-14C]lactate or 1 mm[U-14C]butyrate. In the studies aimed to assess the effect of structural analogues on transport, depending on the experiment, 5 mm of either sodium pyruvate, l-lactate or butyrate were included in the incubation medium. Transport was stopped after 2.5 min by immediately washing the oocytes five times with 1 ml of ice cold Barth's solution pH 7.0, containing either 0.1 mml-lactate or 1 mm butyrate. Single oocytes were placed into scintillation vials and lysed by the addition of 200 μl of formic acid. After lysis, 3 ml scintillation fluid was added and radioactivity was determined in a liquid scintillation counter (Hewlett Packard, UK).

RESULTS

Detection of MCT1 by RT-PCR

Primers derived from the human heart MCT1 cDNA sequence were used for RT-PCR. A product of 544 bp was identified in ileum and colon of both human and pig total RNA. To confirm the identity of the product, the 544 bp cDNA fragment was isolated from healthy human colonic total RNA and subcloned into pGEM-T for sequence analysis. The determined sequence was identical to the human heart MCT1 cDNA sequence (Garcia et al. 1994b).

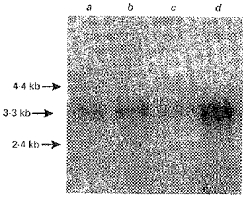

Detection of MCT1 transcript by Northern blot analysis

Total RNA samples were isolated from normal human and pig ileum and colon. RNA samples were separated on a 1% (w/v) denaturing agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane and probed with the 544 bp human colonic RT-PCR product under high stringency conditions by Northern blot analysis. A single transcript of 3.3 kb was observed in all samples (Fig. 1). In both species, the abundance of the transcript appeared to be greater in the colon than in the ileum. The size of this transcript is similar to the reported sizes of MCT1 transcripts in rat skeletal muscle (Jackson et al. 1995), rat small intestine (Takanaga et al. 1995) and human colon (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998b; Price et al. 1998).

Figure 1. Detection of MCT1 transcript in pig and human colon by Northern blot analysis.

Human and pig colonic RNA (5 μg lane−1, each) was fractionated on a 1% (w/v) denaturing agarose gel containing 0.66 m formaldehyde, transferred to nylon membrane and probed with the radiolabelled human colonic RT-PCR product. Lane a, pig ileal RNA; lane b, pig colonic RNA; lane c, human ileal RNA; lane d, human colonic RNA.

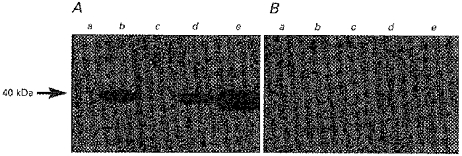

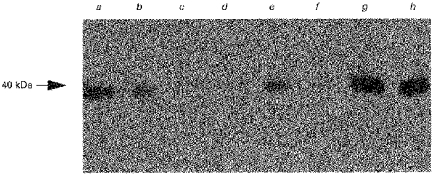

Detection of MCT1 protein by Western blot analysis

The presence of MCT1 protein in purified and well characterized LMV isolated from healthy human and pig colon was investigated. Samples of pig and human colonic homogenate and LMV were separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% (w/v) SDS and electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Rat erythrocyte ghosts were used as a positive control for MCT1 protein detection. Figure 2A shows that the anti-peptide antibody to human MCT1 cross reacted strongly with the rat erythrocyte ghosts (lane e) at an apparent molecular mass of 40 kDa (Carpenter et al. 1996). The antibody also recognized a band at a molecular mass of 40 kDa in human (lane d) and pig (lane b) colonic LMV, which was specifically blocked by pre-absorbing the primary antibody with the immunizing peptide antigen (Fig. 2B). The abundance of the specific immunoreactive band in the LMV (lanes b and d) and corresponding cellular homogenates (lanes a and c) were measured by scanning densitometry (Phoretix). The abundance was 15- to 20-fold enhanced in the LMV compared with the cellular homogenate, indicating its predominant location on the colonic lumenal membrane. Rat erythrocyte ghosts were used as an appropriate control in our studies, as human erythrocytes possess low levels of MCT1 protein and do not produce a visible signal in Western blot analysis (A. P. Halestrap, personal communication; Wilson et al. 1998).

Figure 2. Immunodetection of MCT1 protein in pig and human colonic LMV.

LMV were dissolved in sample buffer containing SDS. Samples (20 μg (lane of protein)−1, each) were separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting was carried out as described in Methods. The specificity of the immunoreaction was determined by comparing blots carried out under standard conditions (A) with those in which the MCT1 antibody had been pre-incubated with the immunizing peptide antigen (B). Lane a, pig colonic homogenate; lane b, pig colonic LMV; lane c, human colonic homogenate; lane d, human colonic LMV; lane e, rat erythrocyte ghosts.

Characteristics of l-lactate transport Effect of extravesicular medium pH on l-lactate transport into pig colonic LMV

l-lactate transport across the plasma membrane of cells such as erythrocytes (Dubinsky & Racker, 1978; Poole & Halestrap, 1991) cardiac myocytes (Wang et al. 1993) and hepatocytes (Edlund & Halestrap, 1988; Jackson & Halestrap, 1996) has been shown to be facilitated by a proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter. In kidney, however, l-lactate is transported by a Na+-coupled monocarboxylate transporter (Poole & Halestrap, 1993; Price et al. 1998). Garcia et al. (1994a), who functionally expressed MCT1 cDNA in a human breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), have shown that either pyruvate or l-lactate uptake into these cells was stimulated by prior loading of the cells with either pyruvate, l-lactate, propionate or butyrate.

We determined the effect of pH and anion gradients on l-lactate transport into pig colonic LMV. LMV were preloaded with a buffer containing either mannitol or 100 mml-lactate, buffered at either pH 7.5 or 5.5. LMV were then incubated in isosmolar solutions containing 0.1 mml-lactate, 100 mm mannitol and 100 mm sodium gluconate at either pH 5.5 or pH 7.5. The initial rate (i.e. uptake measured at 5 s, see inset to Fig. 3) of L-[U-14C]lactate uptake was measured in the absence or presence of a pH and/or anion gradient. The results are shown in Table 1. l-lactate uptake was measured into LMV preloaded with mannitol buffered at either pH 5.5 or 7.5. Under these conditions the uptake was highest in the presence of an inwardly directed transmembrane pH gradient (pHo = 5.5, pHi = 7.5) (see Table 1). The transmembrane pH gradient (pHo < pHi) could facilitate l-lactate uptake into colonic LMV by either proton-lactate symport or lactate-hydroxyl exchange. Alternatively, it could have a direct effect on the l-lactate transport protein. Further experiments were carried out to measure the uptake of l-lactate into LMV, preloaded with 100 mml-lactate either at pH 5.5 or 7.5. The results are presented in Table 1. In all conditions tested, the transport of l-lactate into l-lactate-loaded vesicles was higher than those loaded with mannitol. Furthermore, initial rates of l-lactate uptake were 3.5-fold higher (296 ± 25 vs. 87 ± 4 or 241 ± 5 vs. 67 ± 4 in pmol (mg protein)−1 (5 s)−1) when the extravesicular pH of the media was 5.5 irrespective of the presence or absence of an inwardly directed pH gradient. It appears therefore that the presence of an outwardly directed anion gradient stimulates l-lactate uptake at the extravesicular pH of 5.5.

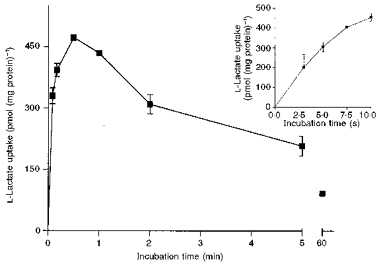

Figure 3. Time course of l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV.

LMV were preloaded with standard loading buffer (100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium l-lactate, 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5 and 0.1 mm MgSO4). LMV (100 μg of protein per assay) were incubated in the standard uptake media containing 100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium gluconate, 20 mm Mes-Tris pH 5.5, 0.1 mm MgSO4, and 0.1 mm L-[U-14C]lactate. Uptake was measured at 37 °C as described. Values are presented as means ±s.e.m. for three experiments. The inset shows the linear phase of l-lactate uptake.

Table 1.

Effect of pH and anion gradients on l-lactate uptake

| l-Lactate uptake (pmol (mg protein)−1 (5s)−1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Mannitol loaded | l-Lactate loaded |

| pHo = pH1 = 7.5 | 38 ± 3 | 87 ± 4* |

| pHo = 5.5; pH1 = 7.5 | 134 = 14 | 296 ± 25* |

| pHo = pH1 = 5.5 | 53 ± 4 | 241 ± 5* |

| pHo = 7.5; pH1 = 5.5 | 24 ± 5 | 67 ±4* |

LMV were isolated as described in Methods. Vesicles were preloaded with either 300 mm mannitol or with 100 mm mannitol and 100 mm sodium l-lactate, 0.1 mm MgSo4, and either 20 mm Mes-Tris pH 5.5 or 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5. Membrane vesicles (100 μg of protein per assay) were incubated in the standard uptake buffer containing 100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium gluconate, 0.1 mm MgSO4, 0.1 mml[U-14C]lactate and either 20 mm Mes-Tris PH 5.5 or 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5. Uptake was measured at 37°C as described in Methods. The reaction was stopped after 5 s by the addition of 1 ml ice-cold stop buffer (100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium gluconate, 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5, 0.1 mm MgSO4 and 0.1 mm sodium l-lactate) and samplews were filtered under vacuum. Values are presented as means ±s.e.m. for three experiments.

Statistically significant (P < 0.05) compared with the matched control (mannitol loaded).

Effect of various intravesicular anions on l-lactate uptake into pig and human colonic LMV

The potential of various anions, when present intravesicularly, to stimulate l-lactate transport into LMV was investigated. The vesicles were preloaded as described in the legend to Table 2 with buffers containing either 100 mm of different anions or 300 mm mannitol. The initial rate of 0.1 mm L-[U-14C]lactate uptake was measured in the presence of isosmolar sodium gluconate containing incubation buffers in the presence of a pH gradient (pHi = 7.5, pHo = 5.5). The results are summarized in Table 2. The initial rate of l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV under the conditions measured was enhanced equally with the intravesicular anions l-lactate, butyrate, propionate, acetate or bicarbonate (P < 0.05). No stimulation of l-lactate uptake was observed if vesicles were preloaded with either gluconate, succinate, or mannitol. In human colonic LMV, l-lactate uptake was also stimulated in the presence of intravesicular l-lactate and butyrate compared with intravesicular mannitol (Table 2). The data indicate that an intravesicular anion and anion gradient (inside > outside) enhance l-lactate transport 2.2- to 2.9-fold compared with mannitol-loaded vesicles.

Table 2.

Effect of intravesicular anions on l-lactate uptake

| Intravesicular anion | l-Lactate uptake (pmol (mg protein)−1 (5 s)−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pig colonic LMV | Human colonic LMV | |

| No anion (mannitol) | 114 ± 5 | 121 ± 5 |

| l-Lactate | 330 ± 19* | 281 ± 17* |

| Butyrate | 282 ± 11* | 245 ± 10* |

| Propionate | 259 ± 9* | n.d. |

| Acetate | 248 ± 7* | n.d. |

| Bicarbonate | 275 ± 10* | 269 ± 12* |

| Chloride | 189 ± 10* | n.d. |

| Sulphate | 154 ± 5* | n.d. |

| Succinate | 123 ± 1 | n.d. |

| Gluconate | 122 ± 3 | n.d. |

LMV were isolated as described in Methods. Vesicles were preloaded with 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5, 0.1 mm MgSO4, and 300 mm mannitol or with 100 mm mannitol and 100 mm of the following sodium salts: gluconate, HCO3−, SO42−, succinate, l-lactate, butyrate, Cl−, acetate, or propionate. Membrane vesicles (100 μg of protein per assay) were incubated in the standard uptake buffer containing 100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium gluconate, 20 mm Mes-Tris pH 5.5, 0.1 mm MgSO4 and 0.1 mml-[U-14C]lactate. Uptake was measured at 37 °C as described in Methods. The reaction was stopped after 5 s by the addition of 1 ml ice-cold stop buffer (100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium gluconate, 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5, 0.1 mm MgSO4 and 0.1 mm sodium l-lactate) and samples were filtered under vacuum. Values are presented as means ±s.e.m.for three experiments. n.d. not determined.

Statistically significant, P < 0.05 from control (mannitol loaded).

The transport of l-lactate into colonic LMV was not cation dependent as the replacement of sodium with potassium or any other cations in the incubation media had no effect on the rate of l-lactate uptake. Trans-stimulation of l-lactate uptake by an intravesicular anion has also been reported in various monocarboxylate transporting tissues such as rabbit small intestinal brush-border membrane vesicles (BBMV; Tiruppathi et al. 1988), human placental BBMV (Balkovetz et al. 1988) and rat small intestinal epithelial cells (Lamers, 1975).

Time course of l-lactate uptake

The time course of l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV is shown in Fig. 3. The vesicles were preloaded with a buffer containing 100 mm sodium l-lactate and incubated in an isosmolar sodium gluconate-containing buffer of pH 5.5. Gluconate was selected since it is known to be a membrane impermeable anion (Shirazi-Beechey et al. 1990). l-lactate uptake reached a maximum (overshoot) at 30 s in l-lactate-loaded vesicles (Fig. 3). The concentration of l-lactate inside the vesicles at the overshoot was estimated to be 6-fold higher compared with the uptake value at 60 min, the equilibrium point. The rate of uptake of l-lactate into the pig and human colonic LMV was linear over the 5 s period (see inset to Fig. 3). Therefore, in all studies the initial rate, 5 s uptake value, has been employed.

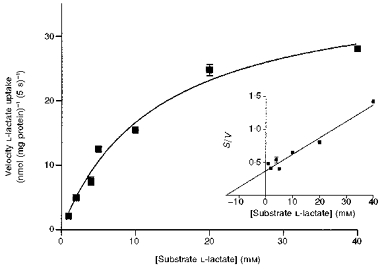

Saturability of l-lactate transport into pig colonic LMV

Figure 4 shows the uptake of l-lactate as a function of increasing substrate concentrations. The initial rate of l-lactate uptake (5 s) was measured with increasing extravesicular l-lactate concentrations (1–40 mm), in the presence of an inwardly directed pH gradient (pHi = 7.5, pHo = 5.5). l-lactate uptake was measured in vesicles preloaded with 100 mm sodium bicarbonate. We used bicarbonate rather than l-lactate as the intravesicular anion as: (1) similar rates of uptake were obtained in either bicarbonate- or l-lactate-loaded vesicles and (2) to eliminate any alterations in l-lactate concentration in the uptake buffer. l-lactate uptake was saturable with an apparent Km of 14.8 ± 1.5 mm and a Vmax of 475 ± 35 nmol (mg protein)−1 min−1 as determined by Wolf-Hanes analysis (inset to Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Saturability of l-lactate transport into pig colonic LMV.

Initial rates of l-lactate transport with increasing lactate concentrations over the range of 1–40 mm were determined. LMV were loaded with 100 mm mannitol, 100 mm NaHCO3, 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5, and 0.1 mm MgSO4. LMV (100 μg protein per assay) were incubated in media containing 100 mm mannitol, 0.1 mm MgSO4, 20 mm Mes-Tris pH 5.5 and varying concentrations of sodium gluconate, sodium l-lactate (to maintain a constant media osmolarity and sodium concentration) and tracer amounts of L-[U-14C]lactate. Uptake was measured at 37 °C for 5 s. The data are presented as a Michaelis-Menten curve and (inset) as Wolf-Hanes plot of substrate concentration (S) against S/V, where V is the velocity, (r2 = 0.96). Values are presented as means ±s.e.m. for three experiments.

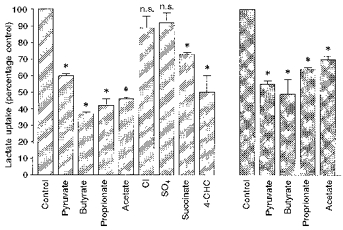

Inhibition of l-lactate transport into pig and human colonic LMV by structural analogues

We tested the effect of various monocarboxylates, including SCFA, on the initial rate of l-lactate transport into pig and human colonic LMV. The initial rate of uptake was determined by incubating the vesicles for 5 s in a buffer containing various anions at a concentration of 20 mm. Incubation conditions are given in the legend to Fig. 5. Pyruvate, butyrate, propionate and acetate reduced l-lactate transport into pig and human colonic LMV by 30–50% (Fig. 5). Inorganic anions Cl− and SO42− had no effect. α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (4-CHC) reduced the rate of l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV by 40%. Kinetic parameters of l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV was determined in the presence of 20 mm butyrate in the incubation medium. The Km for l-lactate transport was increased about 2-fold, from 14.8 ± 1.5 mm to 34.4 ± 4 mm, whereas the change in Vmax was not significant, 475 ± 35 compared with 501 ± 40 nmol (mg protein)−1 min−1. These results indicate that butyrate is inhibiting l-lactate transport in a competitive manner.

Figure 5. Inhibition of l-lactate transport by structural analogues.

LMV isolated from pig ( ) and human (

) and human ( ) colon were preloaded with 100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium l-lactate, 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5 and 0.1 mm MgSO4. LMV (100 μg of protein per assay) were incubated in medium containing 100 mm mannitol, 80 mm sodium gluconate (60 mm sodium gluconate when Na2SO4 and sodium succinate were present in the media and 95 mm sodium gluconate when 4-CHC was present in the media), 20 mm Mes-Tris pH 5.5, 0.1 mm MgSO4, 0.1 mm L-[U-14C]lactate and 20 mm of the following sodium salts: acetate, propionate, butyrate, pyruvate, succinate, Cl−, SO42−. 4-CHC was added at a concentration of 5 mm. Uptake was measured at 37 °C for 5 s. Values are presented as means ±s.e.m. for three experiments. * Statistically significant (P < 0.05) from control.

) colon were preloaded with 100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium l-lactate, 20 mm Hepes-Tris pH 7.5 and 0.1 mm MgSO4. LMV (100 μg of protein per assay) were incubated in medium containing 100 mm mannitol, 80 mm sodium gluconate (60 mm sodium gluconate when Na2SO4 and sodium succinate were present in the media and 95 mm sodium gluconate when 4-CHC was present in the media), 20 mm Mes-Tris pH 5.5, 0.1 mm MgSO4, 0.1 mm L-[U-14C]lactate and 20 mm of the following sodium salts: acetate, propionate, butyrate, pyruvate, succinate, Cl−, SO42−. 4-CHC was added at a concentration of 5 mm. Uptake was measured at 37 °C for 5 s. Values are presented as means ±s.e.m. for three experiments. * Statistically significant (P < 0.05) from control.

Inhibition of l-lactate uptake by various potential inhibitors

In the erythrocyte, l-lactate can be transported by two systems, a H+-l-lactate symporter and the anion exchanger band-3 (Poole & Halestrap, 1993). The stilbene derivatives, 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonate (DIDS) and 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic acid (SITS) are potent inhibitors of band-3 protein (Poole & Halestrap, 1993). These and other distilbene derivatives have been reported to inhibit l-lactate transport in rat erythrocytes (Poole & Halestrap, 1991), rat hepatocytes (Edlund & Halestrap, 1988) and rat myocytes (Wang et al. 1993, 1996). We tested the effect of DIDS and SITS on l-lactate transport into human and pig colonic LMV. The transport was not inhibited by these compounds (see Table 3). These results are supportive of our previous data in which we have shown that an antibody to band-3 protein does not cross react with any protein components of pig and human colonic LMV (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). This indicates that the pig and human colonic lumenal membrane monocarboxylate transporter does not share any structural similarities with band-3 protein.

Table 3.

Effect of various potential inhibitors on l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV

| Inhibitor | l-Lactate uptake | |

|---|---|---|

| (pmol (mg protein)−1 (5 s)−1) | % control | |

| Control | 301 ± 8 | 100 |

| pCMBS | 111 ± 2 | 37* |

| pCMB | 202 ± 13 | 60* |

| HgCl2 | 172 ± 7 | 57* |

| Mersalyl acid | 54 ± 3 | 18* |

| Phloretin | 136 ± 7 | 45* |

| NPPB | 160 ± 6 | 53* |

| DEPC | 202 ± 6 | 67* |

| DIDS | 295 ± 10 | 98 |

| SITS | 280 ± 2 | 93 |

LMV were preloaded with the standard loading buffer (100 mm mannitol, 100 mm sodium l-lactate, 0.1 mm MgSO4, and 20 mm Hepes-Tris, pH 7.5) as described in Methods. Membrane vesicles (100 μg of protein per assay) were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with the indicated compounds. Mercurials (pCMBS, pCMB, HgCl2, mersalyl acid), NPPB, and phloretin were added to a volume of vesicles to give a final concentration of 0.5 mm, whilst the final concentrations of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC), DIDS, SITS amounted to 1 mm. LMV (control) were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. l-Lactate uptake by pretreated and control LMV was measured at 37 °C for 5 s in the standard uptake buffer (see Table 2). Values are presented as means ±s.e.m. for three experiments.

Statistically significant (P < 0.05) from control.

SH-reagents, in particular p-chloromercuribenzenesulphonic acid (pCMBS), are specific inhibitors of l-lactate and pyruvate transport in a variety of tissues (Spencer & Lehninger, 1976; Deuticke et al. 1978; Alonso de la Torre et al. 1992; Poole & Halestrap, 1993). These reagents were also shown to be potent inhibitors of butyrate transport in colonic LMV (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). We tested the effect of several mercurials on l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV (Table 3). Mersalyl acid was most effective, reducing l-lactate uptake by > 80%. pCMBS, p-chloromercuribenzoate (pCMB), HgCl2 and thimerosal also inhibited l-lactate uptake by 40–63%. Phloretin and 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoate (NPPB), well known inhibitors of l-lactate transport in various epithelia (Carpenter & Halestrap, 1994), decreased the rate of l-lactate uptake into pig colonic LMV by > 47–55%. The extent of inhibition of l-lactate uptake into colonic LMV by these compounds is similar to that reported previously for butyrate uptake (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a).

The pattern of inhibition of l-lactate into pig and human colonic LMV by various compounds tested, further supports the evidence that the monocarboxylate transporter (MCT1) is the protein responsible for the transport of l-lactate into pig and human colonic LMV. Furthermore: (a) the similarities in the mechanistic properties of l-lactate transport reported here to that of butyrate transport in the colon (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a), (b) saturation kinetics indicative of a single transport protein and (c) the findings that butyrate inhibits lactate transport in a competitive manner, suggests that the transporter could transport butyrate as well as l-lactate.

Functional studies in oocytes microinjected with MCT1 cRNA

In order to investigate the role of MCT1 further in butyrate transport, we expressed rat MCT1 cRNA in X. laevis oocytes. Rat MCT1 cDNA, cloned in the oocyte expression vector, pGEM-He (Liman et al. 1992) was available and provided by Dr Bröer. This vector has been shown to enhance the level of rat MCT1 cRNA expression in oocytes (Bröer et al. 1997). The microinjection of MCT1 cRNA into X. laevis oocytes resulted in the expression of MCT1 protein in the oocyte plasma membrane. This was shown by an 8-fold enhancement of 0.1 mm L-[U-14C]lactate uptake in oocytes compared with water-injected oocytes (see Table 4). The uptake of 1 mm[U-14C]butyrate was enhanced 2.4-fold in oocytes injected with MCT1 cRNA compared with water-injected control oocytes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Uptake of butyrate and l-lactate in oocytes injected with rat MCT1 cRNA

| Conditions | Uptake (pmol per oocyte (2.5 min)−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | n | Butyrate | l-Lactate | |

| Water-injected (control) | none | 6 | 82 ± 11 | 4 ± 1 |

| MCT1 cRNA injected | none | 6 | 195 ± 31* | 32 ± 11* |

| 5 mm butyrate | 6 | — | 4.6 ± 0.2 | |

| 5 mml-lactate | 6 | 43 ± 8 | — | |

| 5 mm pyruvate | 6 | 40 ± 6 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | |

Oocytes were injected with either 40 nl of sterile water or 40 nl (20 ng) rat MCT1 cRNA (Broöer et al. 1997) and incubated for 4 days. The uptake of 0.1 mml-[U-14C]lactate or 1 mm[U-14C]butyrate was then measured in modified Barth's solution at pH 7.0. Rates of uptake were also determined in the presence or absence of the indicated inhibitor (5 mm). After 2.5 min incubation the reaction was stopped by washing the oocytes 5 times with 1 ml ice cold stop solution (modified Barth's solution pH 7.0 with either 0.1 mml-lactate or 1 mm butyrate). n, number of oocytes

Statistically significant (P < 0.05) from control (water-injected) oocytes.

The effect of butyrate and pyruvate on MCT1-mediated l-lactate uptake and that of l-lactate and pyruvate (5 mm each) on MCT1-mediated butyrate uptake was investigated. These compounds significantly inhibited the uptake of butyrate and l-lactate (see Table 4).

Expression of MCT1 protein in healthy and diseased human colonic tissue determined by Western blot analysis

SCFA are the major anions in the lumen of the colon. It is known that the SCFA butyrate induces cell differentiation and regulates the growth and proliferation of normal colonic mucosa (Treem et al. 1994). Despite the important role of SCFA in the maintenance of colonic health, the detailed molecular mechanism(s) by which SCFA interact with the colonic mucosa is(are) not known. We examined the expression of MCT1 protein in human colonic tissue during transition from normality to malignancy. The abundance of MCT1 protein was determined in lumenal plasma membranes isolated from biopsy samples of healthy and diseased human colonic tissues. Protein components of the membranes were separated by SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies to either human MCT1 or villin. Figure 6, a representative Western blot, shows that the abundance of MCT1 protein declines in precancerous and cancerous colonic tissues compared with healthy colonic tissues. The level of villin, however, remained constant in membranes isolated from healthy, precancerous and cancerous tissue, indicating that the decline in abundance is specific to MCT1 protein.

Figure 6. Immunodetection of MCT1 protein in healthy and diseased human colonic biopsies.

Lumenal plasma membrane fractions were isolated from biopsy-size samples of several healthy, pre-cancerous and cancerous human colonic tissues. Protein fractions were dissolved in sample buffer containing SDS. Samples (20 μg (lane of protein)−1, each) were separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting was carried out as described in Methods. Lane a, colon adenoma; lane b, colon adenoma; lane c, colon adenoma; lane d, rectal carcinoma; lane e, colon adenoma; lane f, colon carcinoma; lane g, healthy colon; lane h, healthy colon.

DISCUSSION

In a previous paper we described the transport of butyrate across isolated human and pig colonic LMV (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). The findings of this study encouraged us to investigate the potential presence of a monocarboxylate transporter isoform in the colonic tissue. Using a RT-PCR strategy, with primers directed to the human heart MCT1 sequence, we isolated a 544 bp product from human colon that was identical to human heart MCT1. In Northern blot analysis using this PCR product as a probe, a single mRNA transcript of 3.3 kb in pig and human colonic RNA was identified. The data support the presence of MCT1 in this tissue. The transcript size of 3.3 kb for MCT1, has also been reported in rat skeletal muscle (Jackson et al. 1995), rat intestine (Tamai et al. 1995; Takanaga et al. 1995). Other isoforms of MCT exhibit different transcript sizes ranging from 2.0 kb (MCT3) to 4.4 kb (MCT7) (Price et al. 1998).

Using an anti-peptide antibody, against the human MCT1 C-terminus amino acid sequence, we demonstrated by immunoblotting the presence of a specific immunoreactive protein in the colonic lumenal membrane. The apparent molecular mass of this protein was 40 kDa, the size reported for the erythrocyte and cardiac myocyte plasma membrane MCT1 (Carpenter et al. 1996). The abundance of this protein was enriched 15- to 20-fold in the human and pig colonic lumenal membranes over the original cellular homogenate, indicating its predominant location on the lumenal membrane.

Transport of l-lactate across rabbit small intestinal BBMV (Tiruppathi et al. 1988) and rat intestinal basolateral membrane vesicle (BLMV; Cheeseman et al. 1994) has been reported. Garcia et al. (1994a) showed using immunocytochemistry that MCT1 protein is localized on the basolateral membrane of hamster caecal epithelial cells. The localization of MCT1 to either the lumenal or the basolateral plasma membrane in various epithelial cells is not surprising. There are many examples of membrane proteins that are basolateral in one cell type and apical in another (Rodriguez-Boulan & Powell, 1992; Scheiffele et al. 1995). For example, the sodium D-glucose cotransporter, which is located on the lumenal membrane of intestinal epithelial cells, resides on the basolateral domain of the parotid acinar cells (Tarpey et al. 1995). It is proposed that the modulation of protein sorting could simply be brought about by inhibition of the cytoplasmic signal by post-translational modifications, which would allow the promiscuous lumenal signal to come into play and redirect the protein to the apical domain (Scheiffele et al. 1995).

Our data on the mechanism of l-lactate transport into colonic LMV shows similarities to previously reported studies in human placental BBMV (Balkovetz et al. 1988) and rabbit small intestinal BBMV (Tiruppathi et al. 1988). These workers reported that l-lactate uptake is enhanced in the presence of an inwardly directed transmembrane pH gradient (pHo < pHi), when measured in the absence of any intravesicular anion. They further demonstrated that in the absence of a pH gradient (pHi = pHo = 7.5) l-lactate uptake was stimulated in membrane vesicles that were preloaded with either l-lactate or pyruvate (Balkovetz et al. 1988). We have also shown that, in the absence of a pH gradient when pHi = pHo = 7.5, l-lactate uptake into pig and human colonic LMV, preloaded with l-lactate, was 2.3-fold higher compared with the mannitol-loaded vesicles (38 ± 3 vs. 87 ± 4 pmol (mg protein)−1 (5 s)−1; see Table 1). In experiments in which the extravesicular pH was reduced to 5.5, initial rates of l-lactate uptake in the absence (pHi = pHo = 5.5) or presence (pHi = 7.5, pHo = 5.5) of an inwardly directed pH gradient were not significantly different (see Table 1; 241 ± 5 and 296 ± 25 pmol (mg protein)−1 (5 s)−1). In the absence of a pH gradient, the presence of an outward-directed anion gradient is the only driving force for the uptake. The rates of uptake were higher in conditions when the extravesicular pH was 5.5 (irrespective of intracellular pH being 5.5 or 7.5) compared with an extravesicular pH of 7.5 indicating that pH 5.5 is a more favourable condition for the activity of the lactate transporter. The data collectively suggest that l-lactate is transported by an anion exchange mechanism with an optimum activity at an extravesicular pH of 5.5. In conditions when the vesicles were preloaded with the buffered mannitol, the rates of uptake were highest in the order of [pHo = 5.5; pHi = 7.5] > [pHo = pHi = 5.5] =[pHo = pHi = 7.5] > [pHo = 7.5; pHi = 5.5]. The highest rate of uptake is in the situation when: (a) the outward gradient of OH− anion is 100-fold higher (pH 5.5 vs. 7.5) and (b) extravesicular pH is 5.5, an optimum condition for the activity of the lactate transporter. The latter results can be interpreted as showing that in buffered mannitol-loaded vesicles the mechanism of transport is either via a lactate- hydroxyl exchanger or by a proton-lactate symporter.

Anions such as acetate, propionate, or bicarbonate, when included intravesicularly, also increased the rates of l-lactate uptake, compared with vesicles loaded with mannitol. It has been shown, by Garcia et al. (1994a), that l-lactate uptake was enhanced 2-fold following preloading of CHO cells with pyruvate, propionate or butyrate. Efflux of l-lactate into media containing l-lactate, butyrate, or bicarbonate was also stimulated in rat small intestinal BLMV (Cheeseman et al. 1994).

l-lactate transport across the plasma membrane of cells such as erythrocytes (Dubinsky & Racker, 1978; Poole & Halestrap, 1991), cardiac myocytes (Wang et al. 1993) and hepatocytes (Edlund & Halestrap, 1988; Jackson & Halestrap, 1996) has been shown to be facilitated by a proton-monocarboxylate symporter. In kidney, however, l-lactate is transported by a Na+-coupled cotransporter (Poole & Halestrap, 1993), and in jejunal basolateral membrane by an anion exchange mechanism (Cheeseman et al. 1994). The data presented in this paper propose that lactate is transported in the colon via a proton-activated, anion exchanger. The functional diversity among monocarboxylate transporters expressed in different tissues suggests varied mechanisms of regulation and interaction with other plasma membrane proteins. The recent identification of a glycoprotein in rat erythrocytes, with close apposition to the substrate binding site of MCT1, proposes the presence of such proteins involved in modification of functional properties of monocarboxylate transporters expressed in various tissues (Poole & Halestrap, 1997). The functional diversity amongst the members of membrane transporter isoforms is not exclusive to monocarboxylate transporters. There are also functional variations amongst anion exchangers (Lee et al. 1991; Humphreys et al. 1994).

Interestingly the mechanism for the transport of l-lactate into pig and human colonic LMV reported in this paper is identical to that identified for the transport of butyrate in the same LMV (Ritzhaupt et al. 1998a). Furthermore, their inhibitory properties are also indistinguishable. Both colonic l-lactate and butyrate transport are inhibited by mercurials and phloretin. The notable observations are that acetate, propionate and butyrate also inhibit l-lactate uptake. Michaelis-Menten kinetic analysis of l-lactate transport showed saturation, and indicated the presence of a single transport protein. The presence of 20 mm butyrate in the extravesicular media increased the apparent Km of l-lactate transport about 2-fold, whereas the Vmax was unchanged. These results support the proposition that butyrate can be transported by the same protein as lactate.

We have also shown that MCT1, when expressed in the oocyte of the African toad Xenopus laevis, can transport butyrate as well as l-lactate. It is well established that cRNA encoding a plasma membrane transport protein when injected into oocytes is efficiently translated. The synthesized protein is then directed to the plasma membrane where its transport activity can be directly measured (Colman & Morser, 1979). Our data indicate that oocytes injected with MCT1 cRNA can transport butyrate as well as l-lactate and that uptake of l-lactate into oocytes is inhibited by butyrate and vice versa. These findings provide strong evidence that MCT1 can transport butyrate.

We have shown that the abundance of the colonic lumenal membrane MCT1 protein declines during transition from normality to malignancy. This decline in abundance is specific as the levels of villin, a colonic lumenal membrane structural protein, remained relatively constant in lumenal membranes. This implies that the expression of MCT1 protein may be impaired in the diseased colon. This in turn would reduce the availability of SCFA required to maintain the intracellular events regulating normal differentiation and proliferation in the colonic mucosa. The availability of molecular probes (cDNA and antibody) to the butyrate transporter will facilitate the identification of molecular and cellular mechanisms by which butyrate regulates the growth and development of the colonic epithelium.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr R. C. Poole and Professor A. P. Halestrap (University of Bristol, UK) for the gift of the human MCT1 antibody and corresponding peptide, Dr S. Bröer (University of Tübingen, Germany) for the gift of the rat MCT1 cDNA, Dr D. Riccardi (University of Manchester, UK) for kindly providing X. laevis and Dr Jane Dyer for her helpful comments on the paper. Our thanks are due to Sister Joan Shaw of Broadgreen Hospital, Liverpool. S. P. Shirazi-Beechey is a Wellcome Trust Senior Lecturer. I. S. Wood is a postdoctoral fellow and A. Ritzhaupt a postgraduate student supported by Tenovus. The financial support of Tenovus is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Alonso de la Torre SRA, Serrano MA, Medina JM. Carrier-mediated β-D-hydroxybutyrate transport in brush-border membrane vesicles from rat placenta. Pediatric Research. 1992;32:317–323. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkovetz DF, Leibach FH, Mahesh VB, Ganapathy V. A proton gradient is the driving force for uphill transport of lactate in human placental brush-border membrane vesicles. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:13823–13830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman EN. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiological Reviews. 1990;70:567–590. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry RD, Paraskeva C. Expression of a carcinoembryonic antigen by the adenoma and carcinoma derived epithelial cell lines: possible marker of tumour progression and modulation of expression by sodium butyrate. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:447–450. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bröer S, Raham B, Pellegri G, Martin J-L, Verleysdonk S, Hamprecht B, Magistetti PJ. Comparison of lactate transport in astroglial cells and monocarboxylate transporter I (MCT1) expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:30096–30102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter L, Halestrap AP. The kinetics, substrate and inhibitor specificity of the lactate transporter of Ehrlich-Lettré tumour cells studied with the intracellular pH indicator BCECF. Biochemical Journal. 1994;304:751–760. doi: 10.1042/bj3040751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter L, Poole RC, Halestrap AP. Cloning and sequencing of the monocarboxylate transporter from mouse Ehrlich Lettré tumour cell confirms its identity as MCT1 and demonstrates that glycosylation is not required for MCT1 function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1279:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman CI, Shariff S, O'Neill D. Evidence for a lactate-anion exchanger in the rat jejunal basolateral membrane. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:559–566. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman A, Morser J. Export of proteins from oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Cell. 1979;17:517–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JH. Colonic absorption: The importance of SCFA in man. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1984;19:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuticke B, Rickert I, Beyer E. Stereoselective, SH-dependent transfer of lactate in mammalian erythrocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1978;507:137–155. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubinsky WP, Racker E. The mechanism of lactate transport in human erythrocytes. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1978;44:25–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01940571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund GL, Halestrap AP. The kinetics of transport of lactate and pyruvate into rat hepatocytes. Biochemical Journal. 1988;249:117–126. doi: 10.1042/bj2490117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CK, Brown MS, Pathak RK, Goldstein JL. cDNA cloning of MCT2, a second monocarboxylate transporter expressed in different cells than MCT1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:1843–1849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CK, Goldstein JL, Pathak RK, Anderson RGW, Brown MS. Molecular characterization of a membrane transporter for lactate, pyruvate, and other monocarboxylates: implications for the cori cycle. Cell. 1994a;76:865–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90361-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CK, Li X, Luna J, Francke U. cDNA cloning of the human monocarboxylate transporter 1 and chromosomal localization of the SLC16A1 locus to 1P13.2-p12. Genomics. 1994b;23:500–503. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1532. 10.1006/geno.1994.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap AP, Jackson VN, Price NT, Wilson M, Heddle C. Identification, cloning and sequencing of several mammalian monocarboxylate (lactate) transporters and their expression in heart. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;504.P:13S. [Google Scholar]

- Herrin DL, Schmidt GW. Rapid, reversible staining of Northern blots prior to hybridisation. Biotechniques. 1988;6:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys BD, Jiang L, Chernova M, Alper SL. Functional characterisation and regulation by pH of murine AE2 anion exchanger expressed in Xenopus oocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:C1295–1307. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson VN, Halestrap AP. The kinetics, substrate, and inhibitor specificity of the monocarboxylate (lactate) transporter of rat liver cells determined using the fluorescent intracellular pH indicator, 2′,7′-bis(carboxyethyl)−5(6)-carboxyfluorescein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:861–868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.861. 10.1074/jbc.271.2.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson VN, Price NT, Carpenter L, Halestrap AP. Cloning of the monocarboxylate transporter isoform MCT2 from rat testis provides evidence that expression in tissues is species-specific and may involve post-transcriptional regulation. Biochemical Journal. 1997;324:447–453. doi: 10.1042/bj3240447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson VN, Price NT, Halestrap AP. cDNA cloning of MCT1, a monocarboxylate transporter from rat skeletal muscle. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1238:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers JMJ. Some characteristics of monocarboxylic acid transfer across the cell membrane of epithelial cells from rat small intestine. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1975;413:265–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BS, Gunn RB, Kopito RR. Functional differences among non-erythroid anion exchangers expressed in a transfected human cell line. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:11448–11454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman ER, Tytgat J, Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinches SA, Gribble SM, Beechey RB, Ellis A, Shaw JM, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Preparation and characterization of basolateral membrane vesicles from pig and human colonocytes: the mechanism of glucose transport. Biochemical Journal. 1993;294:529–534. doi: 10.1042/bj2940529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole RC, Halestrap AP. Reversible and irreversible inhibition, by stilbenedisulphonates, of lactate transport into rat erythrocytes-identification of some new high-affinity inhibitors. Biochemical Journal. 1991;275:307–312. doi: 10.1042/bj2750307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole RC, Halestrap AP. Transport of lactate and other monocarboxylates across the mammalian plasma membranes. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:C761–782. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole RC, Halestrap AP. Interaction of the erythrocyte lactate transporter (Monocarboxylate transporter 1) with an integral 70-kDa membrane glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:14624–14628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14624. 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole RC, Sansom CE, Halestrap AP. Studies of the membrane topology of the rat erythrocyte H+/lactate cotransporter (MCT1) Biochemical Journal. 1996;320:817–824. doi: 10.1042/bj3200817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price NT, Jackson VN, Halestrap AP. Cloning and sequencing of four new mammalian monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) homologues confirms the existence of a transporter family with an ancient past. Biochemical Journal. 1998;329:321–328. doi: 10.1042/bj3290321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzhaupt A, Ellis A, Hosie KB, Shirazi-Beechey SP. The characterisation of butyrate transport across pig and human colonic luminal membrane. The Journal of Physiology. 1998a;507:819–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.819bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzhaupt A, Wood IS, Ellis A, Hosie KB, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Identification of a monocarboxylate transporter isoform type 1 (MCT1) on the lumenal membrane of human and pig colon. Biochemical Society Transactions. 1998b;26:S120. doi: 10.1042/bst026s120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robine S, Huet C, Moll R, Sahuguillo-Merino C, Coudrier E, Zweibaum A, Louvard D. Can villin be used to identify malignant and undifferentiated normal digestive epithelial cells? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1985;82:8488–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Boulan E, Powell SK. Polarity of epithelial and neuronal cells. Annual Review of Cell Biology. 1992;8:395–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.002143. 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick G. Active transport of 5-hydroxytryptamine by plasma membrane vesicles isolated from human platelets. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1977;252:2170–2174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Peranen J, Simons K. N-glycans as apical sorting signals in epithelial cells. Nature. 1995;378:96–98. doi: 10.1038/378096a0. 10.1038/378096a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi SP, Beechey RB, Butterworth PJ. The use of potent inhibitors of alkaline phosphatase to investigate the role of the enzyme in intestinal transport of inorganic phosphate. Biochemical Journal. 1981;4:803–809. doi: 10.1042/bj1940803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi-Beechey SP, Davies AG, Tebbutt K, Dyer J, Ellis A, Taylor CJ, Fairclough P, Beechey RB. Preparation and properties of brush-border membrane vesicles from human small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90288-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi-Beechey SP, Gorvel J-P, Beechey RB. Phosphate transport in intestinal brush-border membrane. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1988;20:273–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00768399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TL, Lehninger AL. L-Lactate transport in Ehrlich ascites-tumour cells. Biochemical Journal. 1976;154:405–414. doi: 10.1042/bj1540405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takanaga H, Tamai I, Inaba S, Sai Y, Higashida H, Yamamoto H, Tsuji A. cDNA cloning and functional characterization of rat intestinal monocarboxylate transporter. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;217:370–377. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2786. 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai I, Takanaga H, Maeda H, Sai Y, Ogihara T, Higashida H, Tsuji A. Participation of a proton-cotransporter, MCT1, in the intestinal transport of monocarboxylic acids. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;214:482–489. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2312. 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpey PS, Wood IS, Shirazi-Beechey SP, Beechey RB. Amino acid sequence and the cellular location of the Na+-dependent D-glucose symporters (SGLT1) in the ovine enterocyte and the parotid acinar cell. Biochemical Journal. 1995;312:293–300. doi: 10.1042/bj3120293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruppathi C, Balkovetz DF, Ganapathy V, Miyamoto Y, Leibach FH. A proton gradient, not a sodium gradient, is the driving force for active transport of lactate in rabbit intestinal brush-border membrane vesicles. Biochemical Journal. 1988;256:219–223. doi: 10.1042/bj2560219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treem WR, Ahsan N, Shoup M, Hyams JS. Fecal short-chain fatty acids in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pedriatic Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 1994;18:159–164. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Levi AJ, Halestrap AP. Substrate and inhibitor specificities of the monocarboxylate transporters of single rat heart cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:H476–484. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.2.H476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Poole RC, Halestrap AP, Levi AJ. Characterization of the inhibition by stilbene disulphonates and phloretin of lactate and pyruvate transport into rat and guinea-pig caradiac myocytes suggests the presence of two kinetically distinct carriers in heart cells. Biochemical Journal. 1993;290:249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2900249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MC, Jackson VN, Heddle C, Price NT, Pilegaard H, Juel C, Bonen A, Montgomery I, Hutter OF, Halestrap AP. Lactic acid efflux from white skeletal muscle is catalyzed by the monocarboxylate transporter isoform MCT3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:15920–15926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.15920. 10.1074/jbc.273.26.15920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]