Abstract

Screening of rat cortex cDNA resulted in cloning of two complete and one partial orthologue of the Drosophila ether-à-go-go-like K+ channel (elk).

Northern blot and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis revealed predominant expression of rat elk mRNAs in brain. Each rat elk mRNA showed a distinct, but overlapping expression pattern in different rat brain areas.

Transient transfection of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with rat elk1 or rat elk2 cDNA gave rise to voltage-activated K+ channels with novel properties.

RELK1 channels mediated slowly activating sustained potassium currents. The threshold for activation was at −90 mV. Currents were insensitive to tetraethylammonium (TEA) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), but were blocked by micromolar concentrations of Ba2+. RELK1 activation kinetics were not dependent on prepulse potential like REAG-mediated currents.

RELK2 channels produced currents with a fast inactivation component and HERG-like tail currents. RELK2 currents were not sensitive to the HERG channel blocker E4031.

Mutations in the ether-à-go-go gene (eag) in Drosophila melanogaster cause repetitive firing of motoneurons and increased transmitter release (Ganetzky & Wu, 1985). The eag gene codes for subunits of voltage-dependent potassium (Kv) channels (Warmke et al. 1991; Brüggemann et al. 1993). Two additional members of the eag family cloned from Drosophila melanogaster are the eag-like K+ channel (elk) (Warmke & Ganetzky, 1994) and the eag-related gene, which is encoded in the Drosophila seizure locus (Titus et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1997). They are distantly related to the Shaker family of voltage-gated potassium channels, sharing their transmembrane topology of six putative membrane-spanning segments (S1-S6) and a P-domain between S5 and S6. In addition, EAG family members are distantly related to the cyclic nucleotide-gated (Guy et al. 1991) and hyperpolarization-activated channels (Ludwig et al. 1998; Santoro et al. 1998). The eag family homologues express Kv channels with distinct functional properties upon depolarization of the membrane. REAG channels mediate non-inactivating currents, of which the activation kinetics depends on prepulse potential (Ludwig et al. 1994). HERG channels exhibit a very rapid inactivation. During recovery from inactivation, HERG channels produce inwardly rectifying currents (Smith et al. 1996). HERG currents have been correlated with IKR in the heart (Sanguinetti et al. 1995; London et al. 1997). Importantly, mutations in the HERG gene give rise to the LQT2 syndrome (Curran et al. 1995). The functional properties of Drosophila ELK are unknown, and no mammalian homologue of the elk gene has been described so far.

In this study we report the cloning of rat orthologues of the Drosophila elk gene and demonstrate their tissue distribution and biophysical properties.

METHODS

Cloning of rat elk

Based on the published Drosophila (D.) elk cDNA sequence (Acc. No. U04246) the degenerate oligonucleotide primers S1 GC(T/C/G)CC(C/G)CAGAACAC(C/A)TT(C/T)(C/T)T(G/C)GA (nt. 25–47 of D. elk open reading frame (ORF)) and AS1 TACCA(T/G)ATGCAGGC(C/A)A(T/G)CCA(G/A)TG (nt. 1254–1231 of D. elk ORF) were used for a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with rat brain first strand cDNA as template. Three different D. elk homologous rat PCR products were identified: rat elk1 (1182 bp), rat elk2 (1086 bp) and rat elk3 (1072 bp). The PCR products were labelled with [α-32P]dCTP by nick translation and hybridized to a λ-ZAPII rat cortex cDNA library (Stratagene) under standard conditions (Sambrook et al. 1989). The cDNA clone rat elk1A (3027 bp) contained the major part (nt. 1–2929) of the rat elk1 ORF. The missing 3′-end was amplified via PCR from the same library using a rat elk1-specific (nt. 2754–2773) and a vector-specific oligonucleotide primer. Three independent PCR products were used for sequence determination. rat elk1B (930 bp). It was ligated with rat elk1A using a unique Nde I restriction site (nt. 2918 in rat elk1A and nt. 105 in rat elk1B) and cloned into Bluescript SK− to yield prelk1 containing a 3689 bp rat elk1 cDNA. Two phages were isolated containing together the complete rat elk2 ORF. Rat elk2A (3488 bp) and rat elk2B (1634 bp) overlapped for 1527 bp and were combined using a unique Eco RI site at nt. 188 in rat elk2A and at nt. 295 in rat elk2B to give prelk2, a 3595 bp rat elk2 cDNA in Bluescript SK−. A ribosomal binding site (Kozak, 1986) was introduced by PCR upstream of the initial ATG of rat elk2 ORF using primer S2 (AGATCTAGACCACCATGCCGGCCATGCGGGG nt. −5–17 rat elk ORF) and primer AS2 (CTGGAGAAACCCGTGAGGTC nt. 170–151) and prelk2 as template. For electrophysiological studies rat elk1 and rat elk2 cDNA were cloned into the multiple cloning site of the pcDNA 3 vector (Invitrogen) using appropriate restriction enzymes.

Sequence analysis was done using the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) program package version 9.0. Rat elk cDNA sequences were deposited at the EMBL data bank (rat elk1, Acc. No. AJ007628; rat elk2, Acc. No. AJ007627; rat elk3, Acc. No. AJ007632).

Northern blot

For Northern blot analysis rat multiple tissue blots (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) were hybridized with probes derived from the 3′-halfs of rat elk1 cDNA (nt. 3011–3335) and the rat elk2 cDNA (nt. 2446–3218), respectively. Probes were labelled with [α-32P]dCTP by nick translation. Control hybridizations were done with an actin probe supplied by the manufacturer, and were done according to the manufacturer's manual. Exposure time was 72 h at −70°C.

First strand cDNA synthesis and PCR

Adult Sprague-Dawley rats were ether anaesthetized and decapitated. Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissue using the S.N.A.P. Kit (Invitrogen). After DNase digestion 5 μg of total RNA were employed for oligo(dT) primed reverse transcription with Superscript II (Gibco BRL) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Amplification of cDNAs was performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 1 μl of the first strand reaction, 100 pmol each primer, 0.2 mm each dNTP, 50 mm KCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 1.5 mm MgCl2 and 1.25 U Taq DNA polymerase (GibcoBRL). Reaction conditions were: 35 cycles with 45 s at 94°C, 1 min at 58°C (GAPDH, rat elk2, rat elk3) or 1 min at 63°C (rat elk1), 1 min at 72°C. PCR products separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and blotted onto nylon membrane were hybridized with [α-32P]dCTP labelled probes derived from rat elk1, rat elk2 and rat elk3 cDNA. None of the probes contained primer sequences. Primer sequences may be obtained on request.

Electrophysiology

CHO cells were maintained according to standard protocols. Cells were transiently transfected with 0.336 pmol rat elk1 pcDNA3 or 0.332 pmol rat elk2 pcDNA3 and 0.12 pmol EGFP pcDNA3 (Clontech) using DMRIE-C-reagent (Gibco). Within 36–72 h of transfection, currents were recorded under conditions previously described (Sewing et al. 1996). The 50 mm K+ solution contained (mm): 90 NaCl, 50 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, 10 glucose and 10 sucrose; pH 7.4. RELK2 currents were corrected for leak and capacitative currents using the P/4 method. Most time constants (τ) were fitted with a monoexponential function (I(t) =a exp(-t/τ)). The time constants of RELK1 activation were fitted with a biexponential function:

Data were fitted in SIGMAPLOT (Jandel Scientific) with the Boltzmann function:

where gmax is the maximal conductance and s is the slope factor.

Drugs were applied by a gravity-driven perfusion system. All substances were purchased from Sigma, except linopirdine (RBI) and E4031 (gift from J. Schwarz, Physiology Institute, Hamburg). Dose-response curves were fitted in SIGMAPLOT with the Hill function:

where C is the concentration and nH if the Hill coefficient.

Data are given as the mean ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

The available Drosophila elk cDNA sequence information (Warmke & Ganetzky, 1994) was used to design a primer pair with which we could amplify by PCR rat elk cDNA fragments from rat brain first strand cDNA (see Methods). The PCR yielded three different ∼1 kb cDNA fragments with three rat elk open reading frames (ORFs) - rat elk1, elk2 and elk3. This indicated that the rat genome encodes a family of Drosophila elk homologous genes. The rat elk cDNAs were numbered according to their sequence relatedness to the Drosophila elk cDNA. Thus, rat elk1 is more closely related to Drosophila elk than rat elk2 or rat elk3 (see below). We used the rat elk cDNA fragments as probes to screen a rat cortex cDNA library. In each case, we obtained positive clones encoding parts of the three elk ORFs, but only in the case of rat elk2 the combined isolated cDNA clones contained a complete rat elk2 ORF. In the case of rat elk1, the longest isolated cDNA clone contained an insert of 3027 bp. The missing 3′-terminus was isolated from the rat cortex cDNA library by PCR as described in Methods. The rat elk3 cDNA clones were not longer than the original 1072 bp PCR fragment that was used to probe the rat cortex cDNA library. In this case, we failed to isolate a longer cDNA, i.e. a complete rat elk3 ORF.

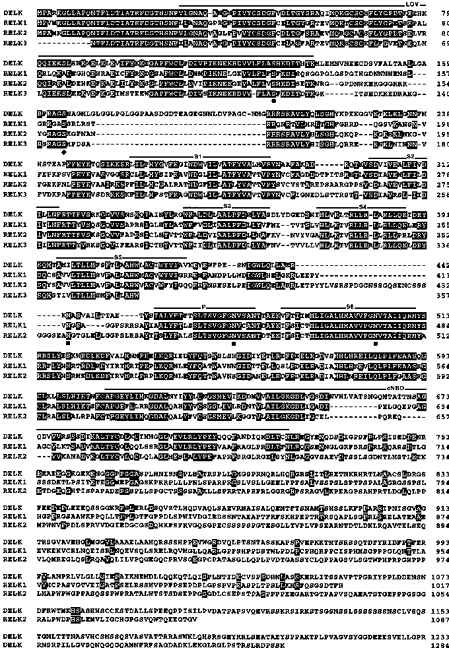

The derived RELK1 and RELK2 protein sequences are 1017 and 1054 amino acids long, respectively (Fig. 1). Thus, they are ∼250 amino acids shorter than the derived Drosophila ELK (DELK) protein sequence. This difference in length is mainly due to an inserted extra sequence in the DELK amino-terminus and to an extended carboxy-terminus. For comparison, the derived incomplete RELK3 sequence, which stops within transmembrane segment 5, has also been included in Fig. 1. The results show that the derived ELK sequences have been highly conserved, in particular the amino-terminus, which contains a LOV-domain (Huala et al. 1997), the membrane spanning core region comprising segments S1-S6 and the P-domain, and the carboxy-terminal putative cyclic nucleotide binding domain (cNBD) (Guy et al. 1991). In contrast, the distal carboxy-terminal sequences appear to be highly divergent. Sequence comparisons of the conserved regions showed that DELK and RELK1 share an identity of 58% with an additional 20% of conservative amino acid residue exchanges, while DELK and RELK2 share an identity of 49% with an additional 23% conserved residues. RELK1 and RELK2 sequences are 65% identical and have 18% conservative replacements. A dendrogram analysis of proteins of the eag superfamily (EAGs, ERGs, ELKs) also indicate that the newly cloned RELK1, RELK2 and RELK3 proteins are more closely related to the DELK protein than to members of the EAG and ERG families (data not shown).

Figure 1. Alignment of DELK, RELK1, RELK2 and RELK3.

Derived DELK, RELK1, RELK2 and RELK3 protein sequences were aligned using the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) program package (Deveraux et al. 1984). The RELK3 sequence is not complete. Numbers at right refer to last amino acid residue in each lane. For optimal alignment gaps were introduced (dashes). Residues identical between DELK and one or more RELK sequence are shaded in black. Hydrophobic segments S1-S6 were determined by hydrophobicity analysis. Segments S1-S6, the P-domain, the LOV domain (Huala et al. 1997), and the putative cyclic nucleotide-binding domain are overlined. Potential N-glycosylation sites are marked by squares. Conserved consensus sequence for protein kinase C and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation is indicated by a dot and a diamond, respectively.

Like other Kv subunits, the RELK polypeptides may be post-translationally modified by phosphorylation, since the derived protein sequences contain consensus sequences for various protein kinases, e.g. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), tyrosine kinase, protein kinases A and C (not shown). Only one of the possible protein kinase C and CaMKII phosphorylation sites has been conserved, both being located in the amino-terminus of DELK, RELK1, RELK2 and RELK3 as indicated in Fig. 1. The sites may subserve an important regulatory function. Unlike most Kvα-subunits of the Shaker family (Chandy & Gutman, 1995), the RELK polypeptides do not contain an NXT/S-sequence for N-glycosylation between hydrophobic segments S1 and S2. Instead, RELK polypeptides contain a consensus sequence for N-glycosylation in the S5/P-linker region (Fig. 1) which most likely is facing the extracellular side. There are two additional potential N-glycosylation sites that appear to have been conserved. Remarkably, one is located in the neighbourhood of the signature sequence motif of K+ channel pores (Heginbotham et al. 1994), the other one in the carboxy-terminal half of hydrophobic segment S6. Thus, a hallmark of ELK polypeptides may be that they are glycosylated near or at the P-domain.

Tissue distribution of rat elk mRNAs

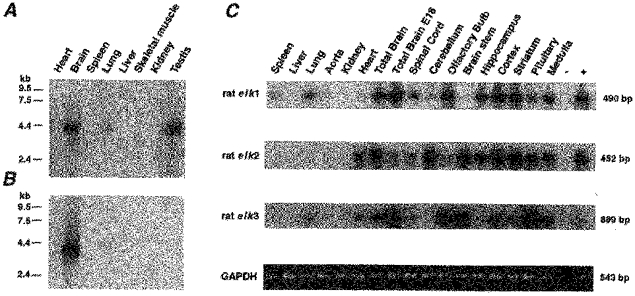

A Northern blot of mRNA preparations from several rat tissues was hybridized with α-32P-labelled rat elk1 and elk2 cDNA probes (Fig. 2A and B). Both probes hybridized to mRNAs of similar size (∼4.2 kb). Prominent rat elk1 mRNA signals were observed in brain and testes. In addition, some rat elk1 mRNA expression was found in lung tissue. No significant signal was detected in heart, spleen, liver, skeletal muscle and kidney. In contrast, rat elk2 mRNA appeared to be prominently expressed in rat brain only.

Figure 2. Expression pattern of rat elk1, rat elk2 and rat elk3 mRNAs in different rat tissues.

A and B, a multiple tissue Northern blot was probed with α-32P-labelled, rat elk1 (A) and rat elk2 (B) cDNA probes. Tissue origin is indicated on top of each lane. The positions of RNA (kb) size markers are indicated at left. C, RT-PCR experiments were performed with RNA isolated from several rat tissues (indicated on top). PCR products were hybridized with the indicated α-32P-labelled rat elk cDNA probe. Expected PCR product sizes are given at right. Amplified GAPDH-PCR products used for control are shown at bottom.

The distribution of rat elk1, elk2 and elk3 mRNAs was then studied in RT-PCR experiments. RNA was isolated from various rat brain areas indicated in Fig. 2C. They were used to amplify specific fragments of the three rat elk mRNAs. The results suggested that rat elk mRNAs are widely expressed in rat brain. The expression patterns revealed a distinct distribution for each rat elk mRNA, e.g. the cerebellum expresses mainly rat elk2 mRNA, the olfactory bulb rat elk1 and elk3 mRNAs, the brainstem rat elk2 and elk3 mRNAs, and the hippocampus rat elk1 and rat elk2 mRNAs. When we compared the expression of rat elk mRNAs in adult (6 months) versus embryonic rat brain (E18) (Fig. 2C), we also observed interesting differences. Rat elk1 mRNA is already prominently expressed in E18 rat brain and seems to be expressed at a comparable level in the adult brain. By contrast, the expression of rat elk2 mRNA appears to be upregulated and that of rat elk3 mRNA downregulated, when the rat brain matures. For comparison, we included RNA of other tissues in the RT-PCR experiments, e.g. spleen, liver, lung, aorta, kidney and heart (Fig. 2C). The results were in good agreement with the ones of the Northern blots shown in Fig. 2A and B. RT-PCR experiments also indicated the presence of rat elk2 (and rat elk3) mRNA in cardiac tissue.

Heterologous expression of rat elk1 and elk2 cDNAs

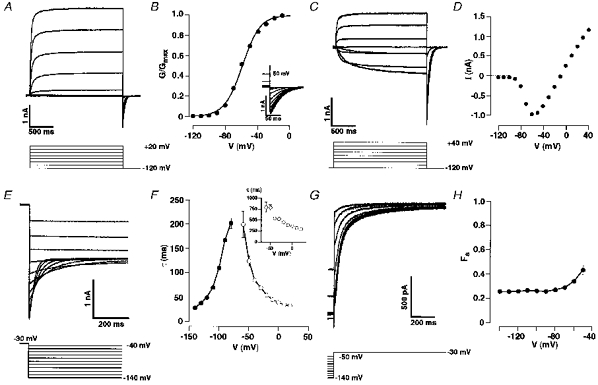

Rat elk1 and elk2 cDNAs were cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3 for heterologous expression of RELK channels in CHO cells. Currents were recorded from the transfected cells in the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration. The membrane potential was stepped from a holding potential of −120 mV to 2 s test potentials in 10 mV increments. In rat elk1-transfected CHO cells, this protocol elicited slowly activating outward currents at test potentials positive to −70 mV (Fig. 3A). During the 2 s test pulses, RELK1-mediated outward currents did not inactivate. This behaviour was reminiscent of REAG-mediated outward currents (Ludwig et al. 1994; Stansfeld et al. 1996). When test potentials were terminated by stepping back to the original holding potential of −120 mV, slowly deactivating tail currents were observed (Fig. 3A and B). The conductance-voltage relationship of the currents was analysed (Fig. 3B). The data were fitted by a Boltzmann function with a half-maximal activation at −59.1 ± 1 mV and a slope of 10.8 ± 0.3 mV (n = 15). The threshold of RELK1 current activation was −90 mV, close to the estimated Nernst equilibrium potential for potassium under the recording conditions. When we changed the extracellular potassium concentration to 50 mm, RELK outward currents were recorded at test potentials positive to −10 mV and RELK1 inward currents negative to −10 mV (Fig. 3C and D) as expected for currents mediated by a potassium selective channel. A plot of RELK1 current amplitude against test potential confirmed the very negative threshold of activation of RELK1 channels. These data indicated that RELK1 channel may operate in an unusually negative membrane potential range, which is typical for hyperpolarized or resting neurons.

Figure 3. Functional properties of RELK1-mediated currents.

A, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from CHO cells transiently transfected with rat elk1 cDNA. Cells were depolarized from a holding potential at −120 mV to the indicated test potentials. B, conductance-voltage relationship derived from tail currents is shown in the inset. Cells were repolarized to −120 mV from the indicated 2 s test potentials. Data were fitted by a Boltzmann equation (see Methods). C, currents were recorded from cells in 50 mm K+ solution (see Methods). Cells were depolarized from a holding potential at −120 mV to the indicated test potentials. D, current-voltage relationship derived from the raw data shown in C. E, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of tail currents following a depolarization to −30 mV. F, time constants of deactivation (•) as a function of the tail potential. Time constants of fast component (τ1) of RELK1 current activation as a function of test potential are indicated by open circles and those of of the slow component (τ2) in the inset. Data points were connected by straight lines and represent mean values (n = 6–14). G, currents were recorded during voltage steps to −30 mV from the indicated holding potentials. H, using the protocol shown in E, the current activated by stepping to −30 mV was described by two time constants: τ1 (fast) and τ2 (slow) (see Results). The fraction of the total current amplitude contributed by the slower component (FS) was plotted against the prepulse potential (n = 6–11). Data points were connected by straight lines.

RELK1 current activation kinetics could be fitted by a two-exponential function. The major time constant, τ1, was 38 ± 3 ms (n = 10), the minor one, τ2, was 360 ± 16 ms (n = 10) at 0 mV. Both time constants are markedly voltage dependent, ranging from τ1 = 199 ± 27 ms (n = 7) and τ2 = 787 ± 108 ms (n = 7) at −60 mV to τ1 = 22 ± 1 ms (n = 9) and τ2 = 204 ± 19 ms (n = 9) at 80 mV. The time course of current deactivation could be fitted by a single exponential function. The time constants of deactivation varied from 201 ± 10 ms (n = 14) at −80 mV to 26 ± 2 ms (n = 6) at −140 mV (Fig. 3E and F). Apparently, RELK1 gating kinetics are slowest around the resting membrane potential. Activation kinetics of REAG currents have also been described by two components with a fast and a slow activation time constant (Stansfeld et al. 1996). Their contribution to the total REAG current amplitude depended on prepulse potential. The ratio F of the amplitude of the slow current component divided by the total current amplitude was voltage dependent with F0.5 at −80 mV. In contrast, F of RELK1 currents remained at ∼0.3 in the voltage range from −140 to −50 mV (Fig. 3G and H).

Transiently transfected CHO cells, expressing RELK2 channels, exhibited slowly activating outward currents at potentials positive to −20 mV (Fig. 4A). At more positive potentials, RELK2 currents showed an inactivation component and completely inactivated at 120 mV within 50 ms. Because of this behaviour, a tail current protocol in a 50 mm potassium-containing bath solution was used to determine steady-state activation of RELK2 currents (Fig. 4B). Half-maximal activation was at 24.4 ± 4.5 mV with a slope of 20.1 ± 2.8 mV (n = 4). Similar to HERG currents (Smith et al. 1996), RELK2 currents rapidly recovered from inactivation at negative potentials (Fig. 4C). Time constants of deactivation and recovery from inactivation were voltage dependent, at potentials between 20 and −120 mV ranging from 50 ± 3 to 172 ± 14 ms (n = 7–18) and 1.5 ± 0.6 to 11.3 ± 2.2 ms (n = 5–17), respectively (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Functional properties of RELK2-mediated currents.

A, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from CHO cells transiently transfected with rat elk2 cDNA. Cells were depolarized from a holding potential of −80 mV to the indicated test potentials. B, conductance-voltage relationships derived from tail currents (inset) measured in 50 mm K+ bath solution (see Methods). Cells were repolarized from the indicated test potentials to a holding potential of −80 mV. Data were fitted by a Boltzmann equation with a V½ = 24.9 ± 4.5 mV (n = 4). C, recordings of tail currents following a depolarization to +80 mV in 50 mm K+ bath solution. D, time constants of deactivation (○) and of recovery from inactivation (•) as a function of the tail potential on a semi-logarithmic scale. Data points were connected by straight lines and represent mean values (n = 5–17).

Previously, we have shown that REAG currents are insensitive to high concentrations of tetraethylammonium (TEA) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) (Ludwig et al. 1994), and sensitive to millimolar concentrations of extracellular Ba2+ (Stansfeld et al. 1997). RELK1 currents had a comparable pharmacology being resistant to 100 mm TEA or 10 mm 4-AP in the bath, but sensitive to external Ba2+ (IC50 = 0.29 mm, n = 3). Interestingly, a RELK1 current increase (1.6-fold at 0 mV, n = 7) was observed after bath application of 10 mm 4-AP. RELK1 and RELK2 currents were not blocked by 10 μm E4031 (n = 5), which blocks HERG channels (Sanguinetti et al. 1995; Trudeau et al. 1995), nor by 10 μm linopirdine (n = 5), which blocks M-channels (Aiken et al. 1995).

DISCUSSION

The eag superfamily comprises the Drosophila genes eag (Warmke et al. 1991), elk (Warmke & Ganetzky, 1994) and erg (Titus et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1997). We have identified three rat homologues of the Drosophila elk gene (Warmke & Ganetzky, 1994) by screening a rat cortex cDNA library. The derived RELK Kv subunits show the hallmarks of EAG type Kvα subunits. They possess six hydrophobic possibly membrane-spanning segments S1-S6, a P-domain and a C-terminal region of homology to cyclic nucleotide-binding domains (Guy et al. 1991). The P-domains of Shaker-related Kvα subunits typically contain a signature sequence with the characterisitic GYGD motif as part of the selectivity filter of the pore (Heginbotham et al. 1994). EAG-related Kvα subunits, including the newly cloned RELK Kv subunits, typically have a GFGN motif in the P-domain, i.e. a variant signature sequence. In addition, eag family members have another conserved domain in the N-terminus, the LOV domain (Huala et al. 1997), which may be a flavin-binding domain that regulates kinase activity in response to blue light-induced redox changes in plant cells. Whether the LOV domain has a regulatory function in eag-related Kv channels remains to be elucidated.

Frequently, Kv channel diversity in the central nervous system is generated by assembly of different subunits to heteromultimers (Shamotienko et al. 1997; Rhodes et al. 1997). The partially overlapping distribution of rat elk1, elk2 and elk3 mRNAs in rat brain is a first indication that diverse RELK channels are possibly expressed by homo- and heteromultimeric assembly of the three RELK subunits. It is interesting to note that the developmental profiles of rat elk1, elk2 and elk3 mRNA expression, and possibly of the corresponding RELK subunits as well, are different. All three mRNAs were detected in RNA of embryonic (E18) rat brain. The expression level of RELK1 is apparently sustained in the adult brain, whereas the one of RELK2 is up- and the one of RELK3 is downregulated. This may indicate that embryonic and adult neurons express RELK channels differently.

Mammalian eag- and erg-related cDNAs have been cloned and been expressed in heterologous expression systems (Ludwig et al. 1994; Sanguinetti et al. 1995; Trudeau et al. 1995; Shi et al. 1997; London et al. 1997). REAG channels give rise to slowly activating, non-inactivating delayed rectifier potassium currents with their activation kinetics strongly depending on prepulse potential (Ludwig et al. 1994). In contrast, HERG channels rapidly inactivate. Recovery from inactivation at negative potentials gives rise to inwardly rectifying HERG currents (Smith et al. 1996). The RERG2 and RERG3 channels display an intermediate gating behaviour resulting in an incomplete inactivation in comparison to HERG channels (Shi et al. 1997). In this report, we show that the expression of RELK1 leads to channels with a remarkably low threshold of activation such as may be active already in quiescent neurons and contribute to the maintenance of the resting membrane potential. However, activation kinetics of RELK1 currents did not depend on prepulse potential

RELK2 channels gave rise to slowly activating K+ currents. At more positive potentials, the evoked currents inactivated rapidly. Recovery from inactivation at negative potentials was reminiscent of that seen for HERG channels (Smith et al. 1996). Serine 631 (S631) near the outer pore entrance of HERG channels is located at an equivalent position to threonine 449, which is an important determinant of C-type inactivation of Shaker channels (Lopez-Barneo et al. 1993). When S631 was mutated to alanine, HERG channels no longer inactivated (Schönherr & Heinemann, 1996). Conversely, when S631 was mutated to cysteine in HERG channels, their rate of inactivation became accelerated (Smith et al. 1996). Interestingly, the RELK1 P-domain contains a cysteine at the equivalent position. Yet RELK1-mediated currents did not inactivate. Also unlike HERG channels (Trudeau et al. 1995; Sanguinetti et al. 1995), RELK channels could not be blocked by the class III antiarrhythmic agent E4031. The data may indicate structural and functional differences between HERG and RELK pores.

Note added in proof

Since this work was submitted for publication the full cDNA sequence has been published in this journal by Shi, Wang, Pan, Wymore, Cohen, McKinnon & Dixon (The Journal of Physiology511, 675–682). Note that the authors used a different nomenclature. Their rat elk 1corresponcds to rat elk 3 in this paper. The sequences of rat elk 2 are identical.

Acknowledgments

O. Pongs thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chem. Industrie for support. A. Neu was supported by a grant from the Graduiertenkolleg Scha 692/1-1. to J. Roeper.

References

- Aiken SP, Lampe BJ, Murphy PA, Brown BS. Reduction in spike frequency adaptation and blockade of M-current in rat CA1 pyramidal neurones by linopirdine (DuP 996), a neurotransmitter release enhancer. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;115:1163–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann A, Pardo LA, Stühmer W, Pongs O. Ether-à-go-go encodes a voltage-gated channel permeable to K+ and Ca2+ and modulated by cAMP. Nature. 1993;365:444–448. doi: 10.1038/365445a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandy KG, Gutman GA. In: Handbook of Receptors and Channels. North PA, editor. FL, USA: CRC, Boca Raton; 1995. pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, Vincent M, Green ED, Keating MT. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programms for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Research. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganetzky B, Wu CF. Genes and membrane excitability in Drosophila. Trends in Neurosciences. 1985;8:322–326. [Google Scholar]

- Guy HR, Durell SR, Warmke J, Drysdale R, Ganetzky B. Similarities in amino acid sequences of Drosophila eag and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Science. 1991;254:730. doi: 10.1126/science.1658932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham L, Lu Z, Abramson T, Mackinnon R. Mutations in the K+ channel signature sequence. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huala E, Oeller PW, Liscum E, Han I-S, Larsen E, Briggs WR. Arabidopsis NPH1: a protein kinase with a putative redox-sensing domain. Science. 1997;278:2120–2123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2120. 10.1126/science.278.5346.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Trudeau MC, Newton KP, Beyer AK, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Satler CA, Robertson GA. Two isoforms of the mouse ether-à-go-go-related gene coassemble to form channels with properties similar to the rapidly activating component of the cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Circulation Research. 1997;81:870–878. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Barneo J, Hoshi T, Heinemann SH, Aldrich RW. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors and Channels. 1993;1:61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, Zong X, Jeglitsch M, Hofmann F, Biel M. A family of hyperpolarization-activated mammalian cation channels. Nature. 1998;393:587–591. doi: 10.1038/31255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J, Terlau H, Wunder F, Brüggemann A, Pardo LA, Marquardt A, Stühmer W, Pongs O. Functional expression of a rat homologue of the voltage gated ether-à-go-go potassium channel reveals differences in selectivity and activation between the Drosophila channel and its mammalian counterpart. EMBO Journal. 1994;13:4451–4458. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KJ, Strassle BW, Monaghan MM, Bekele-Arcuri Z, Matos MF, Trimmer JS. Association and colocalization of the Kvβ1 and Kvβ2 β-subunits with Kv1 α-subunits in mammalian brain K+ channel complexes. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:8246–8258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08246.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual. 2. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Jiang C, Curran ME, Keating MT. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhytmia: HERG encodes the Ikr potassium channel. Cell. 1995;81:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro B, Liu DT, Yao H, Bartsch D, Kandel ER, Siegelbaum A, Tibbs GR. Identification of a gene encoding a hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channel of brain. Cell. 1998;93:717–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr R, Heinemann SH. Molecular determinants for activation and inactivation of HERG, a human inward rectifier potassium channel. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:635–642. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewing S, Roeper J, Pongs O. Kvβ1 subunit binding specific for Shaker-related potassium channel α subunits. Neuron. 1996;16:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80063-x. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamotienko OG, Parcej DN, Dolly JO. Subunit combinations defined for K+ channel Kv1 subtypes in synaptic membranes from bovine brain. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8195–8201. doi: 10.1021/bi970237g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Wymore RS, Wang H-S, Pan Z, Cohen IS, McKinnon D, Dixon JE. Identification of two nervous system-specific members of the erg potassium channel gene family. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:9423–9432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09423.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PL, Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. The inward rectification mechanism of the HERG cardiac potassium channel. Nature. 1996;379:833–836. doi: 10.1038/379833a0. 10.1038/379833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld CE, Ludwig J, Roeper J, Weseloh R, Brown D, Pongs O. A physiological role for ether-à-go-go K+ channels. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:13–14. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)20058-X. 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)20058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld CE, Roeper J, Ludwig J, Weseloh MR, Marsh SJ, Brown DA, Pongs O. Elevation of intracellular calcium by muscarinic receptor activation induces a block of voltage-activated rat ether-à-go-go channels in a stably transfected cell line. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;91:3438–3442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus SA, Warmke JW, Ganetzky B. The Drosophila erg K+ channel polypeptide is encoded by the seizure locus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:875–881. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00875.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau MC, Warmke JW, Ganetzky B, Robertson GA. HERG, a human inward rectifier in the voltage-gated potassium channel family. Science. 1995;269:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.7604285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Reynolds ER, Déak P, Hall LM. The seizure locus encodes the Drosophila homolog of the HERG potassium channel. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:882–890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00882.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmke J, Drysdale R, Ganetzky B. A distinct potassium channel polypeptide encoded by the Drosophila eag locus. Science. 1991;252:1560–1562. doi: 10.1126/science.1840699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmke JW, Ganetzky B. A family of potassium channel genes related to eag in Drosophila and mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:3438–3442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]