Abstract

Background

Environmental modulation of gene expression in Yersinia pestis is critical for its life style and pathogenesis. Using cDNA microarray technology, we have analyzed the global gene expression of this deadly pathogen when grown under different stress conditions in vitro.

Results

To provide us with a comprehensive view of environmental modulation of global gene expression in Y. pestis, we have analyzed the gene expression profiles of 25 different stress conditions. Almost all known virulence genes of Y. pestis were differentially regulated under multiple environmental perturbations. Clustering enabled us to functionally classify co-expressed genes, including some uncharacterized genes. Collections of operons were predicted from the microarray data, and some of these were confirmed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Several regulatory DNA motifs, probably recognized by the regulatory protein Fur, PurR, or Fnr, were predicted from the clustered genes, and a Fur binding site in the corresponding promoter regions was verified by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Conclusion

The comparative transcriptomics analysis we present here not only benefits our understanding of the molecular determinants of pathogenesis and cellular regulatory circuits in Y. pestis, it also serves as a basis for integrating increasing volumes of microarray data using existing methods.

Background

Yersinia pestis is the etiological agent of plague, alternatively growing in fleas or warm-blood mammals [1]. Fleas acquire this organism via blood meal from a bacteremic mammal, usually a rodent. To produce a transmissible infection, Y. pestis colonizes the flea midgut and forms a biofilm in the proventricular valve optimally at 20 to 26°C, blocking its normal blood feeding [2]. Human beings are occasionally infected by directly contacting infected animals or by being bitten by the blocked fleas. Thus, Y. pestis must experience a temperature shift during the transmission process between rodents, fleas, and humans. It is considered a facultative intracellular pathogen. After the initial subcutaneous invasion, the bacteria migrate into the regional lymph nodes via the subcutaneous lymph vessel. Most of the organisms that invade the lymph nodes are engulfed and killed by the polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) that are attracted to invasion sites in large numbers. However, a few bacilli are taken up by tissue macrophages, providing a fastidious and unoccupied niche for Y. pestis to synthesize virulence determinants [3]. Residence in this niche also facilitates the bacteria's resistance to phagocytosis [4,5]. The moiety escaped from macrophages can multiply outside of host cells and eventually cause systemic infection. The hypothesized prevailing conditions of phagolysosomal microenvironments include acidic pH, oxidative stress, iron scavenging, nutrition limitation, and killing or inhibiting activities of antibacterial peptides. To survive these stressful environments, Y. pestis likely makes appropriate adaptive responses, primarily reflected by the transcriptional changes of specific sets of genes.

A DNA microarray is able to determine simultaneous changes in all the genes of a cell at the mRNA level [6]. We and others have measured the gene expression profiles of Y. pestis in response to a variety of stimulating conditions (stimulon analysis), including temperature alteration tolerance [7-9], increased osmolarity [10], ion deficiency [11], antibiotic treatment [12,13], oxidative and acidic stresses [14], antibacterial peptide treatment [14] and nutrition limitation. We also identified the regulons controlled by each of the regulatory proteins, Fur [11], PhoP [15], OmpR, and OxyR, by comparing the gene expression patterns of the mutant transcriptional regulator with that of its parental strain. In order to acquire more regulatory information, all available microarray data of Y. pestis including those published signature expression profiles [8-13,15] were collected and subjected to clustering analysis, which infers functionality to the clusters of co-regulated genes.

The transcriptional and genomic information gleaned from coordinately regulated genes was also used to computationally search for potential operons (operon prediction) and cis-acting DNA regulatory motifs (motif discovery). Some important findings were further verified by biochemical experiments, including RT-PCR and gel shift assays. This analysis provides an opportunity to gain a global view of environmental modulation of gene expression patterns in Y. pestis.

Results and Discussion

Comprehensive analysis of large sets of microarray expression data is useful to dissect bacterial adaptation to various environments and to understand bacterial gene transcriptional regulation [16,17]. For example, Kendall and his colleagues have compared the general responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induced by a variety of different in vitro conditions (low pH, low nutrients, nitrogen, oxygen stress, stationary phase, and nutrition starvation) [18]. After the determination of the CsrA, SlyA, and PhoPQ regulons in Samonella typhimurium, the relevant regulon members are monitored to define the synergetic or antagonistic roles between these three regulators in cell infection models [16].

Recently, many signature expression profiles of Y. pestis have been reported [7-13,15,19-21]. All the microarray expression data from our laboratory were analyzed using standardized microarray procedures such that they are suitable for comprehensive analysis. Comparative transcriptomics analysis presented here can be used to mine the regulatory information from these available microarray data, providing an opportunity to gain a global view on environmental modulation of gene expression in Y. pestis. This analysis provides an additional dividend towards the transcriptional regulatory networks of Y. pestis.

Virulence genes in response to multiple environmental stresses

In this work, 25 expression profiles of Y. pestis were collected for further integration. We hypothesize that the stress conditions used in these experiments will be encountered by this bacterium during its infection and life cycle. The data supported the notion that Y. pestis has evolved its ability to coordinately regulate a wide set of genes to survive a wide range of environmental perturbations. Almost all of the known virulence genes were active in the stress responses. Thus, identification of the expression patterns of virulence genes upon a wide set of environmental changes will provide a reference to screen for uncharacterized genes that shown the same differential gene expression under the same stressful conditions.

The transmission and infection of Y. pestis can be roughly divided into stages of maintain in fleas, adhesion to host surface, invasion into epithelial or endothelial cells, intracellular growth, antiphagocytosis, and extracellular proliferation (Figure 1). Y. pestis possesses a set of virulence determinants that promote infection in mammalian hosts and/or transmission by flea vectors, and different virulence genes have been proven or proposed to be involved in different infection stages (reviewed in [1,22]).

Figure 1.

Environmental modulation of expression of virulence genes. Shown in the squares are the putative stages of transmission/infection of Y. pestis. The TreeView charts show the transcriptional changes of the virulence genes, where columns represent different microarray experiments, and rows represent genes. Color intensities denote log2 ratios as follows: green, negative; black, zero; red, positive; gray, missing data.

As described previously, expression profiles of Y. pestis showed that almost all the putative virulence genes of Y. pestis were differentially regulated upon temperature alteration [7-9]. Our data showed that Y. pestis known virulence genes also respond to other environmental stresses besides temperature shift (Figure 1). For example, the hemin storage locus, hmsHFRS [23], was repressed by temperature upshift, high osmolarity, nutrition limitation, and streptomycin treatment. The ymt gene encoding Yersinia murine toxin [24] was also regulated by temperature upshift and streptomycin treatment.

Y. pestis synthesizes several antiphagocytic factors, including F1 capsular antigen [25], pH6 antigen [4] and Yersinia outer proteins (Yops) [26]. Expression of Yops was regulated by temperature alteration, increased osmolarity, and nutrition deficiency under normal Ca2+ condition. These data suggest that the low-calcium response of type III secretion system (T3SS) appears to be triggered at the mRNA level by other environmental cues in addition to temperature upshift and Ca2+ limitation. F1 capsular antigen is expressed much more at 37°C than at 26°C [27]. pH6 antigen (PsaA), encoded by the chromosomal psaA gene, expresses in vitro between pH 5 and 6.7 at 35 to 41°C [28], or when bacteria live within phagocytic phagolysome [29]. The psaEFABC operon encodes a chaperone/usher pathway involved in the secretion and assembly of pH6 antigen as a polymer (fimbriae) on the surface of Y. pestis in macrophages [28,30]. PsaE is thought to be a positive regulator of the psaABC locus and is required for maximal expression of the pH6 antigen [31]. A recent study showed that the psaEFABC locus is regulated by RovA [32]. The microarray data showed that the F1 operon was upregulated upon temperature upshift, low pH medium, oxidative stress, low Mg2+, and nutrition deficiency, while the psaEFABC locus was induced by temperature alteration, acid stress, low Mg2+, nutrition limitation, high salinity and hyperosmotic stress. It is reasonable to assume that synergetic operation of complicated microenvironments within mammalian hosts account for the full expression of these two loci.

Prediction of operons from microarray data

Operon prediction is the first step toward elucidating gene regulation and reconstructing regulatory networks. Most approaches for prokaryotic operon prediction were developed on the basis of genomic and/or phylogenetic information [33]. For these methods, training with experimental information of known operons is required to generate the predictors. However, little experimental data of operon structure is currently available for Y. pestis. To predict the potential operons of Y. pestis, we attempted a method that incorporated the empirical correlation coefficient from microarray expression data with the genomic annotation data, including gene orientation, intergenic distance, functional similarity, and intra-genome conservation.

Stress-responsive operons predicted from microarray expression data

By using the criteria described in Methods, we identified 39 potential operons that consisted of 183 genes in Y. pestis (Table 1). Nineteen of these potential operons have been previously studied in other bacteria. There was good agreement between our results and a recent report in which the adjacent genes of Y. pestis CO92 are predicted to be within an operon based on the greater conservation of operons in multiple species [33].

Table 1.

Stress-responsive operons in Y. pestis predicted from microarray expression data

| Potential operon (r value) | Gene ID | Putative or predicted function | Reference (s) |

| Iron uptake or heme synthesis | |||

| yfeABCD operon* (r > 0.91) | YPO2439-2442 | Transport/binding chelated iron | yfeABCD [54] |

| hmuRSTUV operon (r > 0.90) | YPO0279-0283 | Transport/binding hemin | hmuRSTUV [55] |

| ysuJIHG* (r > 0.95) | YPO1529-1532 | Iron uptake | - |

| sufABCDS* (r > 0.90) | YPO2400-2404 | Iron-regulated Fe-S cluster assembly? | - |

| YPO1854-1856* (r > 0.97) | YPO1854-1856 | Iron uptake or heme synthesis? | - |

| Sulfur metabolism | |||

| tauABCD operon (r > 0.90) | YPO0182-0185 | Transport/binding taurine | tauABCD [56] |

| ssuEADCB operon (r > 0.97) | YPO3623-3627 | Sulphur metabolism | ssu operon [57] |

| cys operon (r > 0.92) | YPO3010-3015 | Cysteine synthesis | - |

| YPO1317-1319 (r > 0.97) | YPO1317-1319 | Sulfur metabolism? | - |

| YPO4109-4111 (r > 0.90) | YPO4109-4111 | Sulfur metabolism? | - |

| Urea uptake and urease activation | |||

| ure operon* (r > 0.96) | YPO2665-2672 | Pathogenicity | ure [58, 59] |

| Stress response and adaptation | |||

| dnaKJ operon (r = 0.97) | YPO0468-0469 | Chaperones, chaperonins, heat shock | dnaKJ [60, 61] |

| hslUV operon (r = 0.97) | YPO0105-0106 | Adaptions and atypical conditions | hslUV [62] |

| katY-cybCB operon* (r > 0.90) | YPO3319-3321 | Detoxification and electron transport | - |

| psp operon (r > 0.90) | YPO2349-2351 | Adaptions and atypical conditions | psp operon [63] |

| Ribosome constituents | |||

| rps-rpm-rpl operon (r > 0.90) | YPO0209-0235 | Ribosomal protein synthesis and modification | rps-rpm-rpl operon [64] |

| Energy metabolism | |||

| sdh-suc operon* (r > 0.92) | YPO1109-1116 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | sdhCDAB [65] |

| cyo operon (r > 0.94) | YPO3164-3168 | Aerobic respiration | cyoABCDE [55] |

| nap operon (r > 0.94) | YPO3036-3040 | Electron transport | nap operon [66] |

| atp operon (r > 0.93) | YPO4120-4128 | ATP-proton motive force | atpIBEFHAGDC [67] |

| ace operon* (r > 0.90) | YPO3724-3726 | Glyoxylate bypass | aceBAK [68] |

| nuo operon* (r > 0.92) | YPO2543-2555 | Aerobic respiration | nuo operon [69] |

| Degradation and transport/binding of amino acids | |||

| pro operon* (r > 0.92) | YPO2645-2647 | Transport/binding amino acids and amines | proVWX [70] |

| ast operon (r > 0.90) | YPO1962-1966 | Degradation of amino acids | astCADBE [71] |

| gln operon* (r > 0.91) | YPO2512-2514 | Transport/binding amino acids and amines | glnHPQ [72] |

| others | |||

| YPO1994-1996* (r > 0.98) | YPO1994-1996 | Unknown | - |

| YPO0881-0884 (r = 0.99) | YPO0881-0884 | Chemotaxis and mobility? | - |

| YPO1087-1088 (r = 0.99) | YPO1087-1088 | Phage-related functions and prophage | - |

| YPO0623-0628* (r > 0.94) | YPO0623-0628 | Unknown | - |

| mur operon (r > 0.95) | YPO0550-0553 | Murein sacculus and peptidoglycan | - |

| idn operon (r = 0.96) | YPO2539-2540 | Degradation of carbon compounds | - |

| fad operon* (r = 0.95) | YPO3766-3767 | Degradation of small molecule | - |

| glg operon (r > 0.90) | YPO3938-3942 | Synthesis and modification of cytoplasmic polysaccharides | glg operon [73] |

| YPO3838-3839 (r = 0.92) | YPO3838-3839 | Unknown | - |

| YPO0408-0409* (r = 0.97) | YPO0408-0409 | Unknown | - |

| YPO1516-1517 (r = 0.90) | YPO1516-1517 | Unknown | - |

| YPCD1.15c-1.17c (r > 0.98) | YPCD1.15c-1.17c | Unknown | - |

| yscGHIJK operon* (>0.90) | YPCD1.55-1.57 | T3SS constituents | - |

| YPPCP1.08c-1.09c (r = 0.97) | YPPCP1.08c-1.09c | Unknown | - |

'r' represents the correlation coefficient of adjacent genes; '*' represent the defined operon has the similar expression pattern in two other published microarray datasets [7, 21]; '?' inferred functions of uncharacterized genes; '-' means the corresponding operons have not been experimentally validated in other bacteria.

Verification of predicted operons by RT-PCR

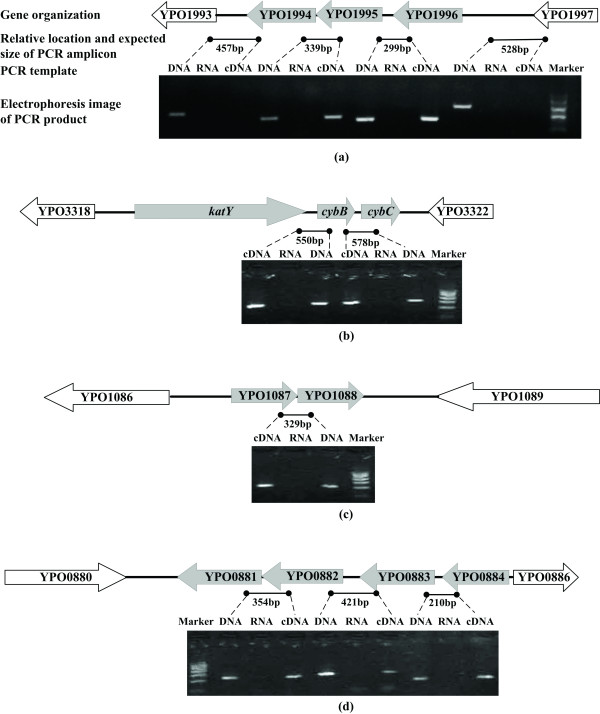

Four predicted operons were chosen for validation by RT-PCR (Figure 2). Given that genes in an operon are expressed to a single mRNA molecule, reverse transcriptase was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA that was subsequently used as template for PCR. Products were analyzed from the beginning, middle, and end of a multi-gene cluster, so as to define where the multi-gene cluster transcript starts and ends. For the operons, YPO1994-1996 (Figure 2a), katY-cybC-cybB (Figure 2b), and YPO1087-1088 (Figure 2c) analyzed, there was perfect consistency with the above in silico prediction. Microarray analysis showed that YPO0881 and YPO0882 were co-expressed, but due to low-quality data it failed to provide the expression data of their downstream genes, YPO0883 and YPO0884. RT-PCR demonstrated that all these four genes were expressed as a single mRNA molecule (Figure 2d), and thus they constituted an operon.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis of potential operons. Shown is the electrophoresis image of an RT-PCR product with the relative location of the expected size. Total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA in the presence or absence of reverse transcriptase, and the resulting cDNA samples subsequently used for RT-PCR templates, are indicated as "cDNA" or "RNA", respectively. Genomic DNA was used as a template, and is indicated as "DNA" for control PCR. "Marker" represents a DNA size marker (900, 700, 500, 300 and 100 bp from top to bottom).

This analysis predicted a total of 39 operons in Y. pestis. The advantage of our strategy is that a high accuracy rate would be achieved by integrating microarray experimental data with genomic information. Although there are many bioinformatics tools available for predicting operons, results presented here demonstrated a new reliable strategy for operon prediction and verification, which will be helpful for functional studies. However, only a small number of operons could be predicted, due to the fact i) that only stress-responsive genes were included for this analysis, and ii) that a lot of contiguous gene pairs passed the criteria, but incomplete array data made it difficult to define the border of their primary mRNA transcripts (for example, the extension of a predicted operon, YPO0881-0882 to YPO0881-0884, was demonstrated by RT-PCR as shown in Figure 2d)

Functional inference of clustering, uncharacterized genes

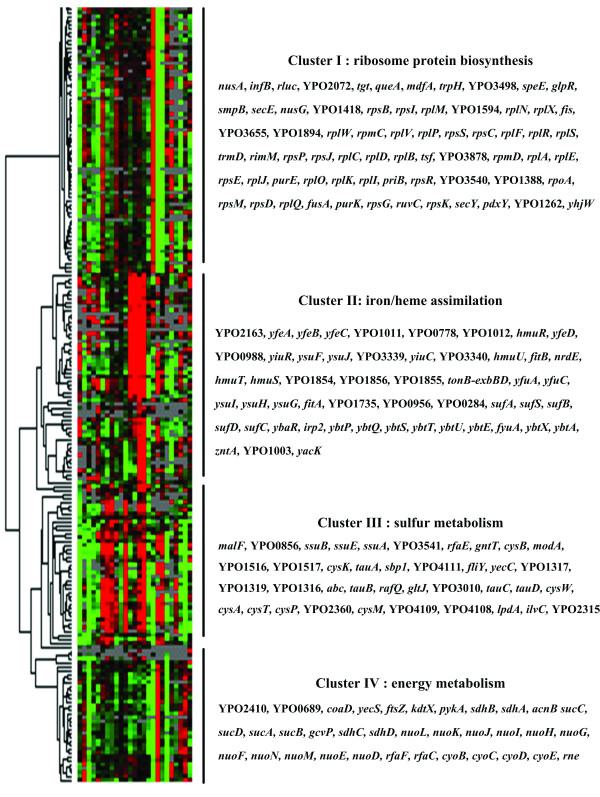

Clustering microarray expression data can be viewed as a data reduction process, in that observations of gene expression in each cluster can be over-represented (Figure 3). This process provides much greater insight into functional classes of co-expressed genes, since genes that are functionally related should be co-regulated and consequently should show similar expression profiles [34,35]. Thus, clustering genes with similar expression patterns can potentially be utilized to predict the functions of gene products with unknown functions, and to identify sets of genes that are co-expressed and may play the same roles in different cell cycles. We analyzed the expression data with unsupervised algorithms and identified four clusters of co-expressed genes that were associated with ribosome biosynthesis, iron/heme assimilation, and sulfur and energy metabolism. The possible roles of uncharacterized genes may be inferred by referencing other members in each cluster.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the clustered microarray data. Columns from left to right represent the different microarray experiments from up to down shown in Table 4, while rows from up to down represent genes and their corresponding gene names were listed in the order (left to right and up to down). The black vertical lines are used to define the range of clusters of co-expressed genes. Red represents up-regulation and green represents down-regulation of the corresponding genes.

Clustering analysis and functional classification of co-expressed gene clusters

Clustering analysis of the whole microarray dataset was analyzed and four distinct clusters of co-expressed genes, cluster I, II, III, and IV, were identified (Figure 3).

Cluster I consisted of more than 70 genes, most of which are functionally related to biosynthesis of ribosomal proteins. The ribosome is the factory of protein synthesis, and it determines the capacity of the cell to synthesize proteins, thus determining the growth rate of the bacteria. Since most of the members in Cluster I were down-regulated in response to a temperature shift from 26 to 37°C, high osmolarity, Mg2+ limitation, nutrition deficiency, and antibiotics treatment, Y. pestis appeared to slow its growth rate under these conditions (see Additional File 1).

Cluster II contains dozens of genes involved in iron/heme assimilation. It is noticeable that almost all of these genes in this cluster were upregulated in response to iron scavenging in wild type (WT) strain, and to iron excess in fur mutant grown at 26°C or 37°C. As shown in Table 2, genes in cluster II could be divided into three categories, A (proven), B (putative), and C (hypothetical). Genes in category A (yfe, hmu, yfu, ybt, and the tonB-exbB-exbD loci) are experimentally proven to be involved in iron/heme assimilation in Y. pestis [36-38]. Category B genes showed high degree of similarity with those known to be responsible for iron/heme assimilation in other bacteria. Those genes in category A and B were also found to be iron-responsive in the previously published expression data [11]. However, category C consisted of the yacK and yhhN-zntA genes that are functionally related to metal metabolism; sufABCDSE that encodes constituents of Fe-S cluster assembly [39]; nrdHIEF which is responsible for glutaredoxin and ribonucleoside-diphosphate reduction [40]; and some genes (YPO0284, YPO0988, YPO1003, YPO2136, YPO1735, YPO1854-1856, YPO3339) without any functional information. Category C genes are likely indirectly or directly related to iron/heme utilization and metabolism.

Table 2.

Classification of the gene members of the cluster II in Figure 3

| Gene locus | Gene ID | Description | reference |

| Category A: Proven | |||

| yfeABCD | YPO2439-2442 | Inorganic iron and manganese binding/transport system | [36] |

| yfuABC | YPO2958-2960 | Inorganic iron transport system | [37] |

| ybt locus | YPO1906-1916 | Siderophore-dependent Yersiniabactin biosynthesis and transport | [74] |

| hmuRSTUV | YPO0279-0283 | Heme transport system | [38] |

| TonB-exbB-exbD | YPO2193, YPO0682-0683 | TonB-ExbB-ExbD complex | [75] |

| yiuABCR | YPO1310-1313 | Putative siderophore ABC-transporter | [76] |

| ysuFJIHG | YPO1528-1532 | Siderophore biosynthetic enzyme system | [76] |

| Category B: Putative | |||

| fitABCD | YPO4022-4025 | Putative iron ABC transporter | |

| Others | YPO0778-0776 | putative siderophore biosysnthesis protein | |

| YPO1011-1012 | putative TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor | ||

| YPO0956 | Putative hydroxamate-type ferri siderophore receptor | ||

| YPO3340 | Putative ferric siderophore receptor (pseudogene) | ||

| Category C: Hypothetical | |||

| sufABCDSE | YPO2399-2404 | Fe-S cluster assembly | |

| nrdHIEF | YPO2648-2651 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase | |

| yacK | YPO3409 | Putative exported protein | |

| yhhN-zntA | YPO3819-3820 | Zinc, lead, cadmium and mercury transporting ATPase | |

| Others | YPO0284 | ||

| YPO0988 | Putative membrane protein | ||

| YPO1003 | Putative exported protein | ||

| YPO1735 | Putative ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) | ||

| YPO1854-1856 | Putative membrane or exported protein | ||

| YPO2163 | Putative nitroreductase | ||

| YPO3339 | Hypothetical protein | ||

Sulfur is one of the nutrients necessary for bacterial life. Genes responsible for sulfur uptake and utilization constitute the cys regulon in Gram-negative bacteria [41]. Cluster III contains members of the cys regulon, including tauABCD, ssuEADCB, cysPUWAM, and sbp1. These genes were regulated by most of the environmental stresses under study, implying that sulfur metabolism might play important roles in the adaptation of Y. pestis to various environmental perturbations. Two genomic loci, YPO1316-1319 and YPO4108-4111, are also included in this sulfur-metabolism-related cluster. Most of the gene products within these two loci were annotated as conserved hypothetical proteins. These two genomic loci might have functions related to sulfur metabolism.

As shown in cluster IV in Figure 3, sdhCDAB and sucABCD involved in tricarboxylic acid cycle had an expressional pattern similar to that of nuoA-N and cyoABCDE involved in aerobic respiration. The microarray data showed that these energy metabolism-related genes were down-regulated upon heat shock, high osmolarity, Mg2+ limitation, and streptomycin treatment, but they were upregulated upon chloramphenicol treatment. These results indicated a general retardation of energy generation in Y. pestis might occur in response to these suboptimal growth conditions.

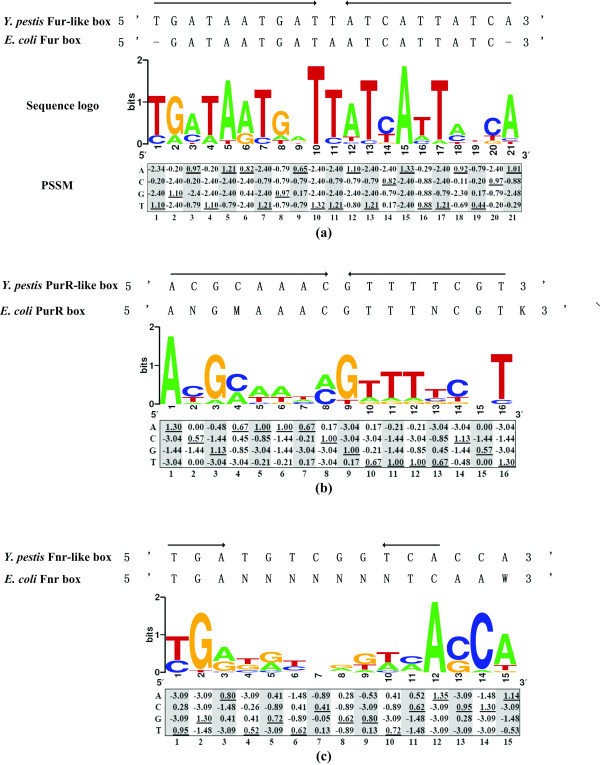

Prediction of regulatory DNA motifs from clustering data

Functionally related members within a cluster of co-expressed genes are likely to be regulated by similar mechanisms; sometimes expression of these genes is even controlled by a single regulatory protein. Promoter DNA sequences containing short (5–20 bp) and relatively conserved regulatory DNA motifs represent the predominant contact sites with the regulatory protein. In this study, the promoter-proximate DNA sequences were collected from each cluster of co-expressed genes. The subsequent motif discovery analysis indicated the presence of DNA motifs that resembled the experimentally proved Fur, PurR, CRP, and Fnr boxes of E. coli and other bacteria [42-46], respectively.

Computational discovery of regulatory DNA motifs

Functionally related members of a cluster of co-expressed genes are likely regulated by similar mechanisms, and even share common cis-regulatory DNA elements within their promoter DNA regions. The presence of a motif-like sequence within the upstream region of a gene suggests that it is likely a direct target of the corresponding regulatory protein.

Here, collections of upstream DNA sequences from each of the above four clusters were searched for potential regulatory motifs (Table 3). DNA boxes were found in the promoter regions of each collection. A 16 basepair (bp) box (5'-ACGCAATCGTTTTCNT-3') was detected in the upstream DNA regions of the cluster I genes. It is very similar to the E. coli PurR box (5'-ANGMAAACGTTTNCGTK-3') [47]. A 21 bp box (5'-TGATAATGATTATCATTATCA-3') was found for the 19 genes in cluster II. It is a 10-1-10 inverted repeat that resembles the E. coli Fur box (5'-GATAATGATAATCATTATC-3') [44]. A 15 bp box (5'-TGANNNNNNTCAA-3') was found within the upstream regions of the cluster III genes. It is a part of the E. coli Fnr box (5'-AAWTTGATNWMNATCAAWWWW-3') [45].

Table 3.

Motif discovery for the clustering genes

| Cluster | Genes or operons for motif discovery | Strict consensus of known TF-like box (See also Figure 4) | Hits of consensus |

| Cluster I | rps-rpm-rpl operon, rpsLG, rpsF-priB-rpsR-rplI, purEK, ruvCAB, rpsB, rplMI, rpsP-rimM-trmD-rplS, nusA-infB and rluC | PurR-like box: 5' ACGCAATCGTTTTCNT 3' | rps-rpm-rpl operon, purEK, ruvCAB, rpsB, rpsP-rimM-trmD-rplS, nusA-infB and rluC |

| Cluster II | hmuRSTUV, YPO0682, YPO0778, YPO0988, YPO1003, YPO1011, ysuFJIHG, YPO1735, YPO1854-YPO1856, irp2-irp1-ybtUTE, ybtPQXS, YPO2163, sufABCDSE, yfeABCD, nrdHIEF, yfuABC, YPO3086, YPO3339, yacK, yhhN-zntA and YPO4022 | Fur-like box: 5' TGATAATGATTATCATTATCA 3' | hmuRSTUV, YPO0682, YPO0988, YPO1011, ysuFJIHG, YPO1735, YPO1854-YPO1856, irp2-irp1-ybtUTE, YPO2163, sufABCDSE, yfeABCD, nrdHIEF, yfuABC, YPO3086, YPO3339, yacK, yhhN-zntA and YPO4022 |

| Cluster III | cysB, ssuEADCB, cysK, YPO3541, YPO1517-YPO1516, YPO1316, YPO1317-YPO1319, fliY, sbp1, tauABCD, YPO0186, YPO2360, YPO3010, cysP, YPO4112, YPO4108, ilvC, YPO2315 and gntT | Fnr-like box: 5' TGAN6TCAA 3' | ssuEADCB, cysK, YPO1517-YPO1516, YPO1317-YPO1319, fliY, sbp1, tauABCD and gntT |

| Cluster IV | sdhCDAB-sucABCD, nuoA-N, cyoABCDE, purB, pta, kbl-tdh, metG, aceE, cysJIH, acnB, murEFXD, YPO1523, gph, trpS, pepD, accBC, mutS, ppc, cydAB, fadBA, fadL, fumA, mdh, oppABCDF, treBC, manX, napFDABC and frdABCD | Fnr/Crp-like box: 5' TGANNNNNNTCA 3' ArcA-like box:5' GTTAATTAATGT 3' | sdhCDAB-sucABCD, pta, kbl-tdh, gph, pepD, mutS, cydAB, fadBA, fumA, oppABCDF, treBC, manX and frdABCD acnB, pepD, mutS, mdh, oppABCDF, manX and frdABCD |

A box sequence (5'-TGAN6TCA-3') was strictly present in the promoter regions of 14 genes in cluster IV. It is a part of the binding boxes of CRP [43] and Fnr [45]. Previous DNA-binding studies showed that CRP bound to exactly the same sequence as that recognized by Fnr [42]. The ArcA regulator can recognize a relatively conservative sequence (5'-GTTAATTAA-3') [46]. An ArcA-box-like sequence (5'-GTTAATTAATGT-3') was found in the upstream sequence of 7 genes in cluster IV (Table 3).

In addition to the DNA boxes mentioned above that described the regulatory motifs with a contiguous oligonucleotide, we constructed their corresponding position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM; related to a table of probabilistic score of observing nucleotides at each position of aligned sites) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of the consensus patterns by motif search. The strict consensus string, sequence logo, and PSSM are included in (a) Fur-like box; (b) PurR-like box; and (c) Fnr-like box. The underlined number is the maximum possible score with PSSM. For the sequence logo, the height of each letter indicates the relative frequency of that base at that position, while the height of each stack of letters corresponds to the sequence conservation at that position.

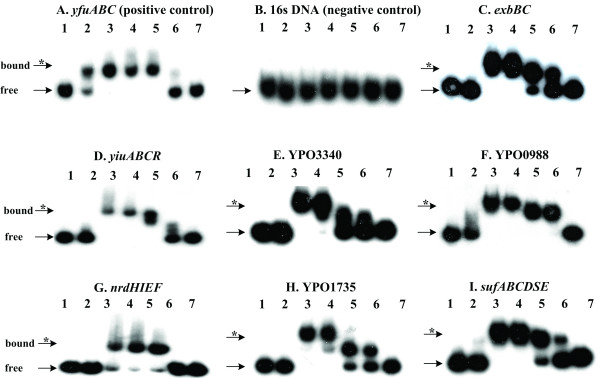

EMSA analysis of Fur binding

The above motif discovery analysis showed that there were Fur-box-like sequences found in the promoter regions of many genes in cluster II (see Table 3). The presence of a sequence with high similarity with Fur box is a predictor of Fur-specific binding. To validate the motif discovery results, eight genes/operons (yfuABC, exbBD, yiuABCR, YPO3340, YPO0988, nrdHIEF, YPO1735, sufABCDSE) were chosen from cluster II, covering all three categories shown in Table 2. EMSA (electrophoretic mobility shift assay) was performed to evaluate the binding of Fur to the upstream promoter DNA. Each promoter region was radioactively labeled, incubated with purified His-Fur protein, and then subjected to native gel electrophoresis. The band of free promoter DNA disappears with the increasing amounts of His-Fur protein, and a DNA band with decreased mobility appears, presumably representing the Fur-DNA complex. Thus, the Fur protein binds to the promoter region of each gene/operon tested in vitro (Figure 5), indicating that the Fur regulator directly controls the expression of these eight genes/operons.

Figure 5.

EMSA analysis of the binding of Fur protein to promoter DNA probes. Lane 1 contains the rabbit anti-F1 IgG of Y. pestis, lane 2 the specific DNA competitor, and lanes 3–7 contain 1.0, 0.7, 0.4, 0.1 and 0 μg of the recombinant Fur protein. In (A) – (I), an arrow and an asterisk indicate the probe (free) and the Fur-probe complex (bound), respectively.

Conclusion

The comprehensive transcriptomics analysis benefits our understanding of the molecular determinants of bacterial pathogenesis and cellular regulatory circuits. Our study gave some hints to the possible function of uncharacterized genes and regulatory elements of Y. pestis such as operons and DNA regulatory motifs. This kind of analysis would provide an opportunity to gain a global view of environmental modulation of gene expression patterns in Y. pestis, which also serve as a basis for integrating increasing volumes of microarray data using existing methods.

Methods

Collection of microarray expression data

Table 4 lists all the expression profiles of Y. pestis in response to various environmental perturbations. Y. pestis strain 201, avirulent to humans, belonging to a newly established biovar, Microtus [48], was grown at 26°C in a chemically defined TMH medium [49] to the middle exponential growth phase (A620 nm approximately 0.8). Cell cultures were diluted 1:20 in fresh TMH medium, and the cells were grown for at least 10 generations at 26°C until reaching A620 nm of approximately 0.8 (26°C cell cultures). If necessary, the cultures were transformed to 37°C for 1 hr (37°C cell cultures). Bacterial cells were then exposed to different in vitro stresses (Table 4), and cells were subsequently harvested for RNA isolation. The genome-wide transcriptional changes upon the environmental perturbations were monitored by the standard dual-fluorescent hybridization method with a Y. pestis whole-genome DNA microarray spotted with PCR-amplified ORFs [8-10]. For the stimulon analysis, the gene expression pattern of WT strain grown under a stimulating condition was compared with that of an unperturbed control. For the regulon analysis, we compared the expression profiles of deletion mutant strains of the target regulator to WT strain. Y. pestis mutants were engineered by replacing the gene targeted for deletion with a Kmr encoding cassette via λ-red phage homologous recombination as described previously [11,15].

Table 4.

Designs for expression profiling of Y. pestis

| Environmental perturbation | Description | Reference (s) |

| Stimulon analysis | ||

| Temperature shift | [8, 9] | |

| Vegetative growth temperatures | Shift from 26°C to 37°C for 3 hr | |

| Heat shock | Shift from 37°C to 45°C for 10 min | |

| Cold shock | Shift from 37°C to 10°C for 1 hr | |

| Osmotic stress | [10] | |

| High osmolarity | Treatment with 0.5 M sorbitol for 20 min | |

| High salinity | Treatment with 0.5 M NaCl for 20 min | |

| Oxidative stress | Treatment with 1 mM H2O2 for 30 min at 26°C | |

| Mild acid stress | Shift from pH7.2 to pH 5.5 for 10 min | |

| Low Mg2+ | Growth under 10 μM Mg2+ | [15] |

| Iron starvation | Treatment with 100 μM of 2, 2'-dipyridyl for 30 min | [11] |

| 26°C | 26°C cell cultures | |

| 37°C | 37°C cell cultures | |

| Minimal versus rich medium | TMH versus BHI medium | |

| Exponential phase | Growth to an A620 nm of approximately 0.8 | |

| Stationary phase | Growth to an A620 nm of approximately 2.0 | |

| Growth phase | Exponential versus stationary phase | |

| Minimum medium | Growth in TMH medium | |

| Rich medium | Growth in BHI medium | |

| Antibiotics treatment | 10× MIC concentration of antibiotics for 30 min | |

| Streptomycin | 37°C cell cultures | [12] |

| chloramphenicol | 37°C cell cultures | |

| Tetracycline | 37°C cell cultures | |

| Antibacterial peptide | 26°C cell cultures | |

| Regulon analysis | ||

| PhoP regulon | phoP mutant versus Wide-type (WT) strain | |

| pH5.5 | Growth at pH5.5 | |

| Low Mg2+ | Growth under 10 μM Mg2+ | [15] |

| Fur regulon | fur mutant versus WT strain | [11] |

| 26°C | 26°C cell cultures with addition of 40 μM of FeCl3 for 30 min | |

| 37°C | 37°C cell cultures with addition of 40 μM of FeCl3 for 30 min | |

| OxyR regulon | oxyR mutant versus WT strain upon exposure to 1 mM H2O2 for 30 min at 26°C | |

| OmpR regulon | ompR mutant versus WT strain | |

| High osmolarity | Upon exposure to 0.5 M sorbitol for 20 min | |

| High salinity | Upon exposure to 0.5 M NaCl for 20 min |

For microarray hybridization, two independent bacterial cultures for each growth condition were prepared as biological replicates for RNA isolation. Three separate labeled probes were made for each RNA preparation as technical replicates. Pairwise comparisons were made using dye swaps to avoid labeling bias.

Whole-genome DNA microarray spotted with 4,005 ORFs was used in our study as described in our previous publications. The data filtering, normalization and significance analysis were done as described previously [9,10]. After filtering the corrupted or suspicious spots during the image analysis phase, expression data of approximately 50%~80% of Y. pestis genes on array are available in each array experiment. All the transcriptome data were collected and displayed as a 4,005 × 25 matrix for all the transcriptional changes of 4,005 genes of Y. pestis in response to 25 environmental perturbations (see Additional File 2). All the microarray data was deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession number GSE9279).

Operon prediction

To measure similarities in gene transcriptional regulation, we calculated the correlation coefficient (r) of neighboring genes between mRNA transcriptional patterns under multiple environmental conditions. We then further focused our analysis to those genes across all arrays that were differentially regulated in at least five experiments. All the analysis was based on the use of log2-ratio of expression values: let xi and yi be the log-ratio of fluorescence intensities for a pair of neighboring genes in experiment i, where n is the number of experiments; n = 25. For each pair of genes, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient, r, between mRNA expression profiles as follows:

Genes were assigned to a potential operon if they met the following criterions: i) the correlation coefficient, r, of neighboring genes was greater than 0.90; ii) they are transcribed in the same direction and are located on the same strand; iii) intergenic distance between two adjacent genes was shorter than 300 bp and iv) they are functionally linked based on the genomic annotation and/or related publications.

Verification of predicted operons by RT-PCR

According to the microarray data, genes tested in operon validation were significantly regulated under the growth temperatures of 26°C, 37°C and 45°C. Therefore, RNA was extracted from cells grown at these three temperatures, as done in microarray experiments. Primer pairs were designed for each adjacent gene studied, such that a PCR amplicon across the intergenic region of the two genes would be produced when genomic DNA was used as template (see Additional File 3). cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription with 5 μg of RNA, 200 U of Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 3 μg of random hexamer primers. A sample of the resulting cDNA (5 μl) was used for PCR amplification. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. To ensure that there was no contamination of genomic DNA, negative controls were performed using RT products with no addition of reverse transcriptase. Reactions containing primer pairs without cDNA template were also included as blank controls.

Clustering analysis

Genes were clustered according to their expression patterns in the twenty-five different experiments using Cluster 3.0 software [50]. Before clustering, genes with expression data in less than three experiments were removed in order to limit the effects of missing values in the clustering analyses. Of the original 4005 probes, the remaining 3339 probes were used for further clustering analysis. For the original and the filtered data, self-organizing map (SOM) program first ran on the whole microarray dataset to cluster the genes based on the similarity of their expression profiles. The output files were then processed by hierarchical clustering by using the average linkage method. Correlation coefficients of more than 0.6 were arbitrarily extracted and visualized with TreeView [50] to graphically display the data by coloring each cell on the basis of the fluorescence ratio. Cells with log ratios of 0 (no change in gene expression) are colored in black; increasing values of positive and negative log ratios are labeled with increasing intensities of red and green, respectively.

Discovery of regulatory DNA motifs

For each cluster of co-expressed genes, neighboring genes were grouped into potential operon structures as described above. Promoter-proximate DNA sequences (400 bp upstream to 50 bp downstream of the start codon of each single-gene transcriptional unit, or the first gene of each operon) were retrieved from the genomic sequence of Y. pestis 91001 with the retrieve-sequence tool [51]. Collections of promoter sequences from co-expressed genes within each cluster were searched for potential regulatory DNA motifs with the multiple expectation maximization for motif elicitation (MEME) program [52].

10–30 bases of a single motif and at least 3 distinct motifs in each run were specified. The first two significant (low E-value) motifs except AT-rich motifs were chosen for further analysis. The symmetrical or dyad elements were preferentially selected. Then, the sequence logos were built by compilation of the conserved sequences detected in the analysis for each motif with the WebLogo program [53]. Finally, PSSM for each DNA motif were built with the consensus and convert-matrix tools [51].

Gel mobility shift analysis of Fur binding

The entire coding region of the fur gene of Y. pestis strain 201 was cloned into pET28a (Novagen, San Diego, CA). Recombinant plasmids encoding a His-Fur fusion protein were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Expression of His-Fur was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). The recombinant protein was purified under native conditions with a QIAexpressionist™ Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The purified, eluted protein was concentrated to approximately 0.3 mg ml-1 with the Amicon Ultra-15 (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The purity of His-Fur protein was verified by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Primers were designed to amplify the 400–500 bp promoter-proximate region extending upstream from the start codon of each first gene of the operons tested (Table S2 for list of oligonucleotide primers used in this study). EMSA was performed using the Gel Shift Assay Systems (Promega, Madison, WI). The DNA was 5'end-labeled using [γ-32P] ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. DNA binding was performed in a 10 μl reaction volume containing: binding buffer [100 μM MnCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 0.05 mg ml-1 poly-(dI-dC)], labeled DNA (1000–2000 c.p.m. μl-1), and increasing amounts of His-Fur protein. We included two control reactions: one contained the specific DNA competitor (unlabeled promoter DNA), while the other was the nonspecific protein competitor [rabbit anti-F1-protein polyclonal antibody (IgG)]. After incubation at room temperature for 30 minutes (min), the products were loaded onto a native 4% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed in 0.5 × Tris-borate (TB) buffer containing 100 μM MnCl2 for 30 min at 220 V. Radioactive species were detected by autoradiography.

Authors' contributions

YH participated in array experiments, data analysis and manuscript drafting. JQ carried out array experiments and the statistical analysis. ZG and HG carried out RT-PCR and EMSA. YS was involved in experiment design and manuscript revision of this paper. DZ and RY conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. Additionally, all authors have already read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Growth curves of Y. pestis strain 201 under different conditions.

Table S1. All the transcriptional changes of 4005 genes of Y. pestis in response to 25 environmental perturbations. Transcriptional changes were presented as the mean log2 ratios of mRNA level for each gene under the paired growth conditions (test/reference). The positive number stands for expression level increased, while minus decreased. Row represents the transcriptional pattern of a specific gene under various environmental perturbations and column stands for the genome-wide expression profile in response to a given condition.

Table S2. List of oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Chen Chen and his co-workers from Chinese Academy of Sciences for their assistance during the course of this work. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (contract no. 30430620). The English writing of the manuscript was polished by International Science Editing, Ireland.

Contributor Information

Yanping Han, Email: yanpinghan@gmail.com.

Jingfu Qiu, Email: jfqiu44@sohu.com.

Zhaobiao Guo, Email: hypiota@sina.com.

He Gao, Email: hezi78@168.net.

Yajun Song, Email: songyajun88@yahoo.com.cn.

Dongsheng Zhou, Email: dongshengzhou1977@gmail.com.

Ruifu Yang, Email: ruifuyang@gmail.com.

References

- Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis--etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:35–66. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch BJ. The evolution of flea-borne transmission in Yersinia pestis. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2005;7:197–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straley SC, Harmon PA. Yersinia pestis grows within phagolysosomes in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1984;45:655–659. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.3.655-659.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XZ, Lindler LE. The pH 6 antigen is an antiphagocytic factor produced by Yersinia pestis independent of Yersinia outer proteins and capsule antigen. Infect Immun. 2004;72:7212–7219. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7212-7219.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol C, Bliska JB. Turning Yersinia pathogenesis outside in: subversion of macrophage function by intracellular yersiniae. Clin Immunol. 2005;114:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius VA, LaRossa RA. Uses and pitfalls of microarrays for studying transcriptional regulation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:114–119. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motin VL, Georgescu AM, Fitch JP, Gu PP, Nelson DO, Mabery SL, Garnham JB, Sokhansanj BA, Ott LL, Coleman MA, Elliott JM, Kegelmeyer LM, Wyrobek AJ, Slezak TR, Brubaker RR, Garcia E. Temporal global changes in gene expression during temperature transition in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6298–6305. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.6298-6305.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Zhou D, Pang X, Song Y, Zhang L, Bao J, Tong Z, Wang J, Guo Z, Zhai J, Du Z, Wang X, Zhang X, Huang P, Yang R. Microarray analysis of temperature-induced transcriptome of Yersinia pestis. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48:791–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Zhou D, Pang X, Zhang L, Song Y, Tong Z, Bao J, Dai E, Wang J, Guo Z, Zhai J, Du Z, Wang X, Huang P, Yang R. DNA microarray analysis of the heat- and cold-shock stimulons in Yersinia pestis. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Zhou D, Pang X, Zhang L, Song Y, Tong Z, Bao J, Dai E, Wang J, Guo Z, Zhai J, Du Z, Wang X, Huang P, Yang R. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Yersinia pestis in response to hyperosmotic and high-salinity stress. Res Microbiol. 2005;156:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Qin L, Han Y, Qiu J, Chen Z, Li B, Song Y, Wang J, Guo Z, Zhai J, Du Z, Wang X, Yang R. Global analysis of iron assimilation and fur regulation in Yersinia pestis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258:9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Zhou D, Han Y, Zhang L, Tong Z, Song Y, Dai E, Li B, Wang J, Guo Z, Zhai J, Du Z, Wang X, Yang R. Global gene expression profile of Yersinia pestis induced by streptomycin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;243:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Zhou D, Qin L, Han Y, Wang X, Du Z, Song Y, Yang R. Microarray expression profiling of Yersinia pestis in response to chloramphenicol. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;263:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Han Y, Qiu J, Qin L, Guo Z, Wang X, Song Y, Tan Y, Du Z, Yang R. Genome-wide transcriptional response of Yersinia pestis to stressful conditions simulating phagolysosomal environments. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:2669–2678. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Han Y, Qin L, Chen Z, Qiu J, Song Y, Li B, Wang J, Guo Z, Du Z, Wang X, Yang R. Transcriptome analysis of the Mg2+-responsive PhoP regulator in Yersinia pestis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;250:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Rowley G, Alston M, Danino V, Hinton JC. Salmonella transcriptomics: relating regulons, stimulons and regulatory networks to the process of infection. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AL, Lory S. Analysis of regulatory networks in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by genomewide transcriptional profiling. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall SL, Rison SC, Movahedzadeh F, Frita R, Stoker NG. What do microarrays really tell us about M. tuberculosis? Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JN, Lyons CR, Johnston SA. Expression profiling of Yersinia pestis during mouse pulmonary infection. DNA Cell Biol. 2006;25:608–616. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.25.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathem WW, Crosby SD, Miller VL, Goldman WE. Progression of primary pneumonic plague: a mouse model of infection, pathology, and bacterial transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17786–17791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506840102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebbane F, Lemaitre N, Sturdevant DE, Rebeil R, Virtaneva K, Porcella SF, Hinnebusch BJ. Adaptive response of Yersinia pestis to extracellular effectors of innate immunity during bubonic plague. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11766–11771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Han Y, Yang R. Molecular and physiological insights into plague transmission, virulence and etiology. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendrak ML, Perry RD. Characterization of a hemin-storage locus of Yersinia pestis. Biol Met. 1991;4:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01135556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindler LE, Plano GV, Burland V, Mayhew GF, Blattner FR. Complete DNA sequence and detailed analysis of the Yersinia pestis KIM5 plasmid encoding murine toxin and capsular antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5731–5742. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5731-5742.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Rosqvist R, Forsberg A. Role of fraction 1 antigen of Yersinia pestis in inhibition of phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1453–1460. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1453-1460.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis GR, Boland A, Boyd AP, Geuijen C, Iriarte M, Neyt C, Sory MP, Stainier I. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1315–1352. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1315-1352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson WJ, Thomas RE, Schwan TG. Recombinant capsular antigen (fraction 1) from Yersinia pestis induces a protective antibody response in BALB/c mice. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:389–396. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zav'yalov VP, Abramov VM, Cherepanov PG, Spirina GV, Chernovskaya TV, Vasiliev AM, Zav'yalova GA. pH6 antigen (PsaA protein) of Yersinia pestis, a novel bacterial Fc-receptor. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;14:53–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoveichuk E, Cherepanov P, Lundberg S, Forsberg A, Olivecrona G. pH6 antigen of Yersinia pestis interacts with plasma lipoproteins and cell membranes. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:320–330. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200182-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D, Tatham D, Williamson ED, Titball RW. The pH 6 antigen of Yersinia pestis binds to beta1-linked galactosyl residues in glycosphingolipids. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4545–4548. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4545-4548.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindler LE, Klempner MS, Straley SC. Yersinia pestis pH 6 antigen: genetic, biochemical, and virulence characterization of a protein involved in the pathogenesis of bubonic plague. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2569–2577. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2569-2577.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathelyn JS, Crosby SD, Lathem WW, Goldman WE, Miller VL. RovA, a global regulator of Yersinia pestis, specifically required for bubonic plague. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13514–13519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603456103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MN, Huang KH, Alm EJ, Arkin AP. A novel method for accurate operon predictions in all sequenced prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:880–892. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius V, Van Dyk TK, Gross C, LaRossa RA. Impact of genomic technologies on studies of bacterial gene expression. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:599–624. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri S, Sutphin PD, Chang JT, Altman RB. Basic microarray analysis: grouping and feature reduction. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19:189–193. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(01)01599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden SW, Perry RD. The Yfe system of Yersinia pestis transports iron and manganese and is required for full virulence of plague. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:403–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Bearden SW, Geoffroy VA, Fetherston JD, Perry RD. Characterization of the Yersinia pestis Yfu ABC inorganic iron transport system. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2829–2837. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.5.2829-2837.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi MS, Fetherston JD, Letoffe S, Carniel E, Perry RD, Ghigo JM. Identification and characterization of the hemophore-dependent heme acquisition system of Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6707–6717. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6707-6717.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumoto U, Kitamura S, Fukuyama K, Takahashi Y. Interchangeability and distinct properties of bacterial Fe-S cluster assembly systems: functional replacement of the isc and suf operons in Escherichia coli with the nifSU-like operon from Helicobacter pylori. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2004;136:199–209. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Pontis E, Aslund F, Hellman U, Gibert I, Reichard P. The ribonucleotide reductase system of Lactococcus lactis. Characterization of an NrdEF enzyme and a new electron transport protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8779–8785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekowska A, Kung HF, Danchin A. Sulfur metabolism in Escherichia coli and related bacteria: facts and fiction. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;2:145–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawers G, Kaiser M, Sirko A, Freundlich M. Transcriptional activation by FNR and CRP: reciprocity of binding-site recognition. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:835–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2811637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyles EA, Chin AJ, Lee JC. Escherichia coli cAMP receptor protein-DNA complexes. 1. Energetic contributions of half-sites and flanking sequences in DNA recognition. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5194–5200. doi: 10.1021/bi972450i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodriguez-Quinones F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro S, Guest JR. FNR and its role in oxygen-regulated gene expression in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;6:399–428. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(05)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghnouj A, Abu-Bakr AA, Baumberg S, Stalon V, Vander Wauven C. Regulation of anaerobic arginine catabolism in Bacillus licheniformis by a protein of the Crp/Fnr family. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;191:227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue L, Thompson W, Carmack C, Ryan MP, Liu JS, Derbyshire V, Lawrence CE. Phylogenetic footprinting of transcription factor binding sites in proteobacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:774–782. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.3.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Tong Z, Song Y, Han Y, Pei D, Pang X, Zhai J, Li M, Cui B, Qi Z, Jin L, Dai R, Du Z, Wang J, Guo Z, Huang P, Yang R. Genetics of metabolic variations between Yersinia pestis biovars and the proposal of a new biovar, microtus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5147–5152. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.5147-5152.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straley SC, Bowmer WS. Virulence genes regulated at the transcriptional level by Ca2+ in Yersinia pestis include structural genes for outer membrane proteins. Infect Immun. 1986;51:445–454. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.445-454.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden J. Regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3593–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Gribskov M. Combining evidence using p-values: application to sequence homology searches. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:48–54. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden SW, Staggs TM, Perry RD. An ABC transporter system of Yersinia pestis allows utilization of chelated iron by Escherichia coli SAB11. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1135–1147. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1135-1147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CP, Albrecht J, Gunsalus RP. Effect of microaerophilic cell growth conditions on expression of the aerobic (cyoABCDE and cydAB) and anaerobic (narGHJI, frdABCD, and dmsABC) respiratory pathway genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1094–1098. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1094-1098.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn E, van der Ploeg JR, Leisinger T. Deletion analysis of the Escherichia coli taurine and alkanesulfonate transport systems. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2687–2695. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.10.2687-2695.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg JR, Cummings NJ, Leisinger T, Connerton IF. Bacillus subtilis genes for the utilization of sulfur from aliphatic sulfonates. Microbiology. 1998;144 ( Pt 9):2555–2561. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akada JK, Shirai M, Takeuchi H, Tsuda M, Nakazawa T. Identification of the urease operon in Helicobacter pylori and its control by mRNA decay in response to pH. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1071–1084. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora D, Maguin E, Masiero M, Parini C, Ricci G, Manachini PL, Daffonchio D. Characterization of urease genes cluster of Streptococcus thermophilus. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:209–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowing DW, Bardwell JC, Craig EA, Woolford C, Hendrix RW, Gross CA. Consensus sequence for Escherichia coli heat shock gene promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:2679–2683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal G, Ron EZ. The dnaKJ operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: transcriptional analysis and evidence for a new heat shock promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5952–5958. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5952-5958.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MS, Chen KP, Wu WF. Regulation of RcsA by the ClpYQ (HslUV) protease in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2004;150:437–446. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S, Lucchini S, Thompson A, Rhen M, Hinton JC. Unravelling the biology of macrophage infection by gene expression profiling of intracellular Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:103–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Trawick JD, Yamamoto R, Zamudio C. Genome-wide operon prediction in Staphylococcus aureus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3689–3702. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maklashina E, Berthold DA, Cecchini G. Anaerobic expression of Escherichia coli succinate dehydrogenase: functional replacement of fumarate reductase in the respiratory chain during anaerobic growth. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5989–5996. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5989-5996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart V, Lu Y, Darwin AJ. Periplasmic nitrate reductase (NapABC enzyme) supports anaerobic respiration by Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1314–1323. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1314-1323.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasimoglu E, Park SJ, Malek J, Tseng CP, Gunsalus RP. Transcriptional regulation of the proton-translocating ATPase (atpIBEFHAGDC) operon of Escherichia coli: control by cell growth rate. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5563–5567. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5563-5567.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro S, Guest JR. Adaptive responses to oxygen limitation in Escherichia coli. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:310–314. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90125-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer CD, Elliott T. Transcriptional control of the nuo operon which encodes the energy-conserving NADH dehydrogenase of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2335–2342. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2335-2342.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucht JM, Bremer E. Adaptation of Escherichia coli to high osmolarity environments: osmoregulation of the high-affinity glycine betaine transport system proU. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:3–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiupakis AK, Reitzer L. ArgR-independent induction and ArgR-dependent superinduction of the astCADBE operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2940–2950. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2940-2950.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer DP, Soupene E, Lee HL, Wendisch VF, Khodursky AB, Peter BJ, Bender RA, Kustu S. Nitrogen regulatory protein C-controlled genes of Escherichia coli: scavenging as a defense against nitrogen limitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14674–14679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugalde JE, Lepek V, Uttaro A, Estrella J, Iglesias A, Ugalde RA. Gene organization and transcription analysis of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens glycogen (glg) operon: two transcripts for the single phosphoglucomutase gene. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6557–6564. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6557-6564.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden SW, Fetherston JD, Perry RD. Genetic organization of the yersiniabactin biosynthetic region and construction of avirulent mutants in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1659–1668. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1659-1668.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postle K. TonB protein and energy transduction between membranes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1993;25:591–601. doi: 10.1007/BF00770246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirillina O, Bobrov AG, Fetherston JD, Perry RD. Hierarchy of iron uptake systems: Yfu and Yiu are functional in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6171–6178. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00874-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Growth curves of Y. pestis strain 201 under different conditions.

Table S1. All the transcriptional changes of 4005 genes of Y. pestis in response to 25 environmental perturbations. Transcriptional changes were presented as the mean log2 ratios of mRNA level for each gene under the paired growth conditions (test/reference). The positive number stands for expression level increased, while minus decreased. Row represents the transcriptional pattern of a specific gene under various environmental perturbations and column stands for the genome-wide expression profile in response to a given condition.

Table S2. List of oligonucleotide primers used in this study.